User login

What’s in a drug name?

My use of drug names is a mixed bag of terms.

In medical school we learn drugs by their generic names, but it doesn’t take long before we realize that each has both a generic name and one (or more) brand names. I suppose there’s also the chemical names, but no one outside the lab uses those. They’re waaaaay too long.

There is, for better or worse, a lot of variability in this. The purists (almost always academics, or cardiologists, or academic cardiologists) insist on generic names only. In their notes, conversations, presentations, whatever. If you’re a medical student or resident under them, you learn fast not to use the brand name.

After 30 years of doing this ... I don’t care. My notes are a mishmash of both.

Let’s face it, brand names are generally shorter and easier to type, spell, and pronounce than the generic names. I still need to know both, but when I’m writing up a note Keppra is far easier than levetiracetam. And most patients find the brand names a lot easier to say and remember.

An even weirder point, which is my own, is that one of my teaching attendings insisted that we capitalize both generic and brand names while on his rotation. Why? He never explained that, but he was pretty insistent. Now, for whatever reason, the habit has stuck with me. I’m sure the cardiologist down the hall would love to send my notes back, heavily marked up with red ink.

There’s even a weird subdivisions in this: Aspirin is a brand name by Bayer. Shouldn’t it be capitalized in our notes? But it isn’t, and to make things more confusing that varies by country. Why? (if you’re curious, it’s a strange combination of 100-year-old patent claims, generic trademark rulings, and also what country you’re in, whether it was involved in World War I, and, if so, which side. Really).

So the medical lists in my notes are certainly understandable, though aren’t going to score me any points for academic correctness. Not that I care. As a medical Shakespeare might have written, Imitrex, Onzetra, Zembrace, Tosymra, Sumavel, Alsuma, Imigran, Migraitan, and Zecuity ... are still sumatriptan by any other name.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My use of drug names is a mixed bag of terms.

In medical school we learn drugs by their generic names, but it doesn’t take long before we realize that each has both a generic name and one (or more) brand names. I suppose there’s also the chemical names, but no one outside the lab uses those. They’re waaaaay too long.

There is, for better or worse, a lot of variability in this. The purists (almost always academics, or cardiologists, or academic cardiologists) insist on generic names only. In their notes, conversations, presentations, whatever. If you’re a medical student or resident under them, you learn fast not to use the brand name.

After 30 years of doing this ... I don’t care. My notes are a mishmash of both.

Let’s face it, brand names are generally shorter and easier to type, spell, and pronounce than the generic names. I still need to know both, but when I’m writing up a note Keppra is far easier than levetiracetam. And most patients find the brand names a lot easier to say and remember.

An even weirder point, which is my own, is that one of my teaching attendings insisted that we capitalize both generic and brand names while on his rotation. Why? He never explained that, but he was pretty insistent. Now, for whatever reason, the habit has stuck with me. I’m sure the cardiologist down the hall would love to send my notes back, heavily marked up with red ink.

There’s even a weird subdivisions in this: Aspirin is a brand name by Bayer. Shouldn’t it be capitalized in our notes? But it isn’t, and to make things more confusing that varies by country. Why? (if you’re curious, it’s a strange combination of 100-year-old patent claims, generic trademark rulings, and also what country you’re in, whether it was involved in World War I, and, if so, which side. Really).

So the medical lists in my notes are certainly understandable, though aren’t going to score me any points for academic correctness. Not that I care. As a medical Shakespeare might have written, Imitrex, Onzetra, Zembrace, Tosymra, Sumavel, Alsuma, Imigran, Migraitan, and Zecuity ... are still sumatriptan by any other name.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My use of drug names is a mixed bag of terms.

In medical school we learn drugs by their generic names, but it doesn’t take long before we realize that each has both a generic name and one (or more) brand names. I suppose there’s also the chemical names, but no one outside the lab uses those. They’re waaaaay too long.

There is, for better or worse, a lot of variability in this. The purists (almost always academics, or cardiologists, or academic cardiologists) insist on generic names only. In their notes, conversations, presentations, whatever. If you’re a medical student or resident under them, you learn fast not to use the brand name.

After 30 years of doing this ... I don’t care. My notes are a mishmash of both.

Let’s face it, brand names are generally shorter and easier to type, spell, and pronounce than the generic names. I still need to know both, but when I’m writing up a note Keppra is far easier than levetiracetam. And most patients find the brand names a lot easier to say and remember.

An even weirder point, which is my own, is that one of my teaching attendings insisted that we capitalize both generic and brand names while on his rotation. Why? He never explained that, but he was pretty insistent. Now, for whatever reason, the habit has stuck with me. I’m sure the cardiologist down the hall would love to send my notes back, heavily marked up with red ink.

There’s even a weird subdivisions in this: Aspirin is a brand name by Bayer. Shouldn’t it be capitalized in our notes? But it isn’t, and to make things more confusing that varies by country. Why? (if you’re curious, it’s a strange combination of 100-year-old patent claims, generic trademark rulings, and also what country you’re in, whether it was involved in World War I, and, if so, which side. Really).

So the medical lists in my notes are certainly understandable, though aren’t going to score me any points for academic correctness. Not that I care. As a medical Shakespeare might have written, Imitrex, Onzetra, Zembrace, Tosymra, Sumavel, Alsuma, Imigran, Migraitan, and Zecuity ... are still sumatriptan by any other name.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Medicaid expansion closing racial gap in GI cancer deaths

Across the United States, minority patients with cancer often have worse outcomes than White patients, with Black patients more likely to die sooner.

But new data suggest that these racial disparities are lessening. They come from a cross-sectional cohort study of patients with gastrointestinal cancers and show that the gap in mortality rates was reduced in Medicaid expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states.

The results were particularly notable for Black patients, for whom there was a consistent increase in receiving therapy (chemotherapy or surgery) and a decrease in mortality from stomach, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer, the investigators commented.

The study was highlighted at a press briefing held in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“The findings of this study provide a solid step for closing the gap, showing that the Medicaid expansion opportunity offered by the Affordable Care Act, which allows participating states to improve health care access for disadvantaged populations, results in better cancer outcomes and mitigation of racial disparities in cancer survival,” commented Julie Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO.

The study included 86,052 patients from the National Cancer Database who, from 2009 to 2019, were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, or stomach cancer. Just over 22,000 patients (25.7%) were Black; the remainder 63,943 (74.3%) were White.

In Medicaid expansion states, there was a greater absolute reduction in 2-year mortality among Black patients with pancreatic cancer of –11.8%, compared with nonexpansion states, at –2.4%, a difference-in-difference (DID) of –9.4%. Additionally, there was an increase in treatment with chemotherapy for patients with stage III-IV pancreatic cancer (4.5% for Black patients and 3.2% for White), compared with patients in nonexpansion states (0.8% for Black patients and 0.4% for White; DID, 3.7% for Black patients and DID, 2.7% for White).

“We found similar results in colorectal cancer, but this effect is primarily observed among the stage IV patients,” commented lead author Naveen Manisundaram, MD, a research fellow at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Black patients with advanced stage disease experienced a 12.6% reduction in mortality in expansion states.”

Among Black patients with stage IV colorectal cancer, there was an increase in rates of surgery in expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states (DID, 5.7%). However, there was no increase in treatment with chemotherapy (DID, 1%; P = .66).

Mortality rates for Black patients with stomach cancer also decreased. In expansion states, there was a –13% absolute decrease in mortality, compared with a –5.2% decrease in nonexpansion states.

The investigators noted that Medicaid coverage was a key component in access to care through the Affordable Care Act. About two-thirds (66.7%) of Black patients had Medicaid; 33.3% were uninsured. Coverage was similar among White patients; 64.1% had Medicaid and 35.9% were uninsured.

“Our study provides compelling data that show Medicaid expansion was associated with improvement in survival for both Black and White patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Additionally, it suggests that Medicaid expansion is one potential avenue to mitigate existing racial survival disparities among these patients,” Dr. Manisundaram concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported an advisory role with Medicaroid. Dr. Gralow has had a consulting or advisory role with Genentech and Roche.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Across the United States, minority patients with cancer often have worse outcomes than White patients, with Black patients more likely to die sooner.

But new data suggest that these racial disparities are lessening. They come from a cross-sectional cohort study of patients with gastrointestinal cancers and show that the gap in mortality rates was reduced in Medicaid expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states.

The results were particularly notable for Black patients, for whom there was a consistent increase in receiving therapy (chemotherapy or surgery) and a decrease in mortality from stomach, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer, the investigators commented.

The study was highlighted at a press briefing held in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“The findings of this study provide a solid step for closing the gap, showing that the Medicaid expansion opportunity offered by the Affordable Care Act, which allows participating states to improve health care access for disadvantaged populations, results in better cancer outcomes and mitigation of racial disparities in cancer survival,” commented Julie Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO.

The study included 86,052 patients from the National Cancer Database who, from 2009 to 2019, were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, or stomach cancer. Just over 22,000 patients (25.7%) were Black; the remainder 63,943 (74.3%) were White.

In Medicaid expansion states, there was a greater absolute reduction in 2-year mortality among Black patients with pancreatic cancer of –11.8%, compared with nonexpansion states, at –2.4%, a difference-in-difference (DID) of –9.4%. Additionally, there was an increase in treatment with chemotherapy for patients with stage III-IV pancreatic cancer (4.5% for Black patients and 3.2% for White), compared with patients in nonexpansion states (0.8% for Black patients and 0.4% for White; DID, 3.7% for Black patients and DID, 2.7% for White).

“We found similar results in colorectal cancer, but this effect is primarily observed among the stage IV patients,” commented lead author Naveen Manisundaram, MD, a research fellow at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Black patients with advanced stage disease experienced a 12.6% reduction in mortality in expansion states.”

Among Black patients with stage IV colorectal cancer, there was an increase in rates of surgery in expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states (DID, 5.7%). However, there was no increase in treatment with chemotherapy (DID, 1%; P = .66).

Mortality rates for Black patients with stomach cancer also decreased. In expansion states, there was a –13% absolute decrease in mortality, compared with a –5.2% decrease in nonexpansion states.

The investigators noted that Medicaid coverage was a key component in access to care through the Affordable Care Act. About two-thirds (66.7%) of Black patients had Medicaid; 33.3% were uninsured. Coverage was similar among White patients; 64.1% had Medicaid and 35.9% were uninsured.

“Our study provides compelling data that show Medicaid expansion was associated with improvement in survival for both Black and White patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Additionally, it suggests that Medicaid expansion is one potential avenue to mitigate existing racial survival disparities among these patients,” Dr. Manisundaram concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported an advisory role with Medicaroid. Dr. Gralow has had a consulting or advisory role with Genentech and Roche.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Across the United States, minority patients with cancer often have worse outcomes than White patients, with Black patients more likely to die sooner.

But new data suggest that these racial disparities are lessening. They come from a cross-sectional cohort study of patients with gastrointestinal cancers and show that the gap in mortality rates was reduced in Medicaid expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states.

The results were particularly notable for Black patients, for whom there was a consistent increase in receiving therapy (chemotherapy or surgery) and a decrease in mortality from stomach, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer, the investigators commented.

The study was highlighted at a press briefing held in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“The findings of this study provide a solid step for closing the gap, showing that the Medicaid expansion opportunity offered by the Affordable Care Act, which allows participating states to improve health care access for disadvantaged populations, results in better cancer outcomes and mitigation of racial disparities in cancer survival,” commented Julie Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO.

The study included 86,052 patients from the National Cancer Database who, from 2009 to 2019, were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, or stomach cancer. Just over 22,000 patients (25.7%) were Black; the remainder 63,943 (74.3%) were White.

In Medicaid expansion states, there was a greater absolute reduction in 2-year mortality among Black patients with pancreatic cancer of –11.8%, compared with nonexpansion states, at –2.4%, a difference-in-difference (DID) of –9.4%. Additionally, there was an increase in treatment with chemotherapy for patients with stage III-IV pancreatic cancer (4.5% for Black patients and 3.2% for White), compared with patients in nonexpansion states (0.8% for Black patients and 0.4% for White; DID, 3.7% for Black patients and DID, 2.7% for White).

“We found similar results in colorectal cancer, but this effect is primarily observed among the stage IV patients,” commented lead author Naveen Manisundaram, MD, a research fellow at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Black patients with advanced stage disease experienced a 12.6% reduction in mortality in expansion states.”

Among Black patients with stage IV colorectal cancer, there was an increase in rates of surgery in expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states (DID, 5.7%). However, there was no increase in treatment with chemotherapy (DID, 1%; P = .66).

Mortality rates for Black patients with stomach cancer also decreased. In expansion states, there was a –13% absolute decrease in mortality, compared with a –5.2% decrease in nonexpansion states.

The investigators noted that Medicaid coverage was a key component in access to care through the Affordable Care Act. About two-thirds (66.7%) of Black patients had Medicaid; 33.3% were uninsured. Coverage was similar among White patients; 64.1% had Medicaid and 35.9% were uninsured.

“Our study provides compelling data that show Medicaid expansion was associated with improvement in survival for both Black and White patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Additionally, it suggests that Medicaid expansion is one potential avenue to mitigate existing racial survival disparities among these patients,” Dr. Manisundaram concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported an advisory role with Medicaroid. Dr. Gralow has had a consulting or advisory role with Genentech and Roche.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2023

Why doctors are disenchanted with Medicare

While physicians are getting less of a Medicare pay cut than they thought this year (Congress voted to cut Medicare payments by 2%, which was less than the expected 8.5%), Medicare still pays physicians only 80% of what many third-party insurers pay.

Moreover, those reimbursements are often slow to arrive, and the paperwork is burdensome. In fact, about 65% of doctors won’t accept new Medicare patients, down from 71% just 5 years ago, according to the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Worse, inflation makes continuous cuts feel even steeper and trickles down to physicians and their patients as more and more doctors become disenchanted and consider dropping Medicare.

Medicare at a glance

Medicare pays physicians about 80% of the “reasonable charge” for covered services. At the same time, private insurers pay nearly double Medicare rates for hospital services.

The Medicare fee schedule is released each year. Physicians who accept Medicare can choose to be a “participating provider” by agreeing to the fee schedule and to not charging more than this amount. “Nonparticipating” providers can charge up to 15% more. Physicians can also opt out of Medicare entirely.

The earliest that physicians receive their payment is 14 days after electronic filing to 28 days after paper filing, but it often can take months.

Physicians lose an estimated 7.3% of Medicare claims to billing problems. With private insurers, an estimated 4.8% is lost.

In 2000, there were 50 million Medicare enrollees; it is projected that by 2050, there will be 87 million enrollees.

Why are doctors disenchanted?

“When Medicare started, the concept of the program was good,” said Rahul Gupta, MD, a geriatrician in Westport, Conn., and chief of internal medicine at St. Vincent’s Medical Center, Bridgeport, Conn. “However, over the years, with new developments in medicine and the explosion of the Medicare-eligible population, the program hasn’t kept up with coverages.” In addition, Medicare’s behemoth power as a government-run agency has ramifications that trickle down irrespective of a patient’s insurance carrier.

“Medicare sets the tone on price and reimbursement, and everyone follows suit,” Dr. Gupta said. “It’s a race to the bottom.”

“The program is great for patients when people need hospitalizations, skilled nursing, and physical therapy,” Dr. Gupta said. “But it’s not great about keeping people healthier and maintaining function via preventive treatments.” Many private insurers must become more adept at that too.

For instance, Dr. Gupta laments the lack of coverage for hearing aids, something his patients could greatly benefit from. Thanks to the Build Back Better bill, coverage of hearing aids will begin in 2024. But, again, most private insurers don’t cover hearing aids either. Some Medicare Advantage plans do.

Medicare doesn’t cover eye health (except for eye exams for diabetes patients), which is an issue for Daniel Laroche, MD, a glaucoma specialist and clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

“I get paid less for Medicare patients by about 20% because of ‘lesser-of’ payments,” said Dr. Laroche. For example, as per Medicare, after patients meet their Part B deductible, they pay 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for glaucoma testing. “It would be nice to get the full amount for Medicare patients.”

“In addition, getting approvals for testing takes time and exhaustive amounts of paperwork, says Adeeti Gupta, MD, a gynecologist and founder of Walk In GYN Care in New York.

“Medicare only covers gynecologist visits every 2 years after the age of 65,” she said. “Any additional testing requires authorization, and Medicare doesn’t cover hormone replacement at all, which really makes me crazy. They will cover Viagra for men, but they won’t cover HRT, which prolongs life, reduces dementia, and prevents bone loss.”

While these three doctors find Medicare lacking in its coverage of their specialty, and their reimbursements are too low, many physicians also find fault regarding Medicare billing, which can put their patients at risk.

The problem with Medicare billing

Because claims are processed by Medicare administrative contractors, it can take about a month for the approval or denial process and for doctors to receive reimbursement.

Prior authorizations, especially with Medicare Advantage plans, are also problematic. For example, one 2022 study found that 18% of payment denials were for services that met coverage and billing rules.

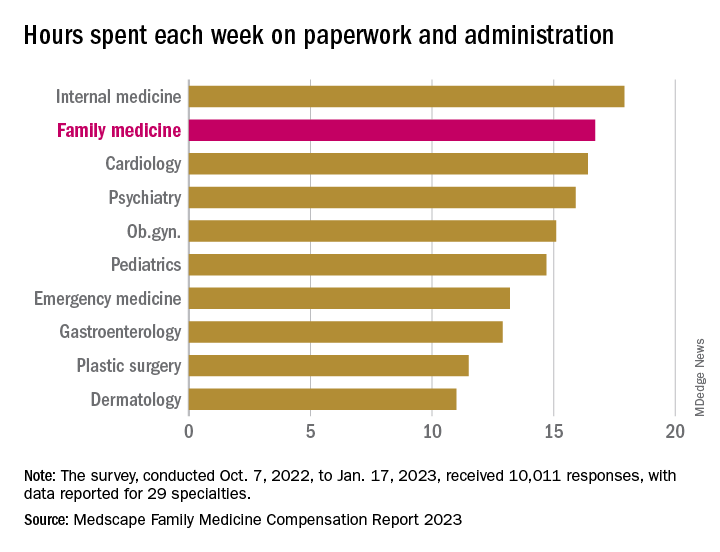

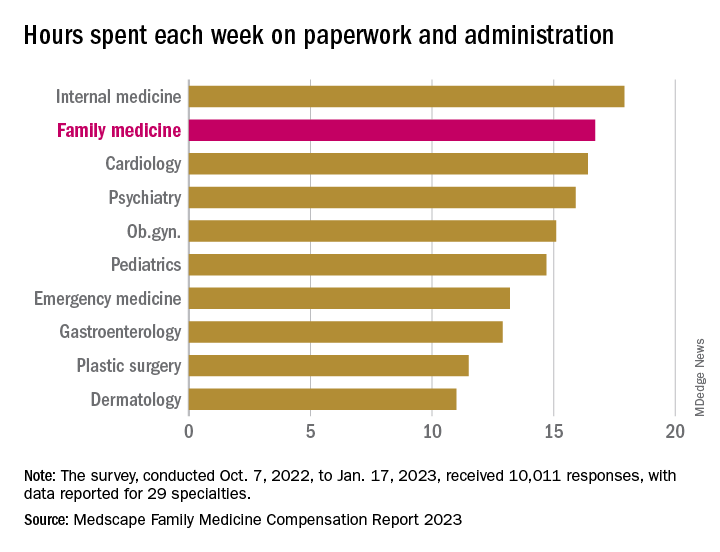

Worse, all of this jockeying for coverage takes time. The average health care provider spends 16.4 hours a week on paperwork and on securing prior authorizations to cover services, according to the American Medical Association.

“A good 40% of my time is exclusively Medicare red tape paperwork,” Rahul Gupta says. “There’s a reason I spend 2-3 hours a night catching up on that stuff.”

Not only does this lead to burnout, but it also means that most physicians must hire an administrator to help with the paperwork.

In comparison, industry averages put the denial rate for all Medicare and private insurance claims at 20%.

“Excessive authorization controls required by health insurers are persistently responsible for serious harm to physician practices and patients when necessary medical care is delayed, denied, or disrupted in an attempt to increase profits,” Dr. Laroche said.

“Our office spends nearly 2 days per week on prior authorizations, creating costly administrative burdens.”

For Adeeti Gupta, the frustrations with Medicare have continued to mount. “We’re just at a dead end,” she said. “Authorizations keep getting denied, and the back-end paperwork is only increasing for us.”

Will more doctors opt out of Medicare?

When doctors don’t accept Medicare, it hurts the patients using it, especially patients who have selected either a Medicare Advantage plan or who become eligible for Medicare at age 65 only to find that fewer doctors take the government-sponsored insurance than in the past.

As of 2020, only 1% of nonpediatric physicians had formally opted out, per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Psychiatrists account for the largest share of opt-outs (7.2%).

“Unfortunately, most doctors outside of hospital-based practices will reach a point when they can’t deal with Medicare paperwork, so they’ll stop taking it,” Rahul Gupta says.

A coalition of 120 physicians’ groups, including the American Medical Association, disputes that Medicare is paying a fair reimbursement rate to physicians and calls for an overhaul in how they adjust physician pay.

“Nothing much changes no matter how much the AMA shouts,” Rahul Gupta said in an interview.

What can doctors do

Prescription prices are another example of the challenges posed by Medicare. When prescriptions are denied because of Medicare’s medigap (or donut hole) program, which puts a cap on medication coverage, which was $4,660 in 2023, Dr. Gupta says she turns to alternative ways to fill them.

“I’ve been telling patients to pay out of pocket and use GoodRx, or we get medications compounded,” she said. “That’s cheaper. For example, for HRT, GoodRx can bring down the cost 40% to 50%.”

The American Medical Association as well as 150 other medical advocacy groups continue to urge Congress to work with the physician community to address the systematic problems within Medicare, especially reimbursement.

Despite the daily challenges, Rahul Gupta says he remains committed to caring for his patients.

“I want to care for the elderly, especially because they already have very few physicians to take care of them, and fortunately, I have a good practice with other coverages,” he said. “I can’t give up.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While physicians are getting less of a Medicare pay cut than they thought this year (Congress voted to cut Medicare payments by 2%, which was less than the expected 8.5%), Medicare still pays physicians only 80% of what many third-party insurers pay.

Moreover, those reimbursements are often slow to arrive, and the paperwork is burdensome. In fact, about 65% of doctors won’t accept new Medicare patients, down from 71% just 5 years ago, according to the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Worse, inflation makes continuous cuts feel even steeper and trickles down to physicians and their patients as more and more doctors become disenchanted and consider dropping Medicare.

Medicare at a glance

Medicare pays physicians about 80% of the “reasonable charge” for covered services. At the same time, private insurers pay nearly double Medicare rates for hospital services.

The Medicare fee schedule is released each year. Physicians who accept Medicare can choose to be a “participating provider” by agreeing to the fee schedule and to not charging more than this amount. “Nonparticipating” providers can charge up to 15% more. Physicians can also opt out of Medicare entirely.

The earliest that physicians receive their payment is 14 days after electronic filing to 28 days after paper filing, but it often can take months.

Physicians lose an estimated 7.3% of Medicare claims to billing problems. With private insurers, an estimated 4.8% is lost.

In 2000, there were 50 million Medicare enrollees; it is projected that by 2050, there will be 87 million enrollees.

Why are doctors disenchanted?

“When Medicare started, the concept of the program was good,” said Rahul Gupta, MD, a geriatrician in Westport, Conn., and chief of internal medicine at St. Vincent’s Medical Center, Bridgeport, Conn. “However, over the years, with new developments in medicine and the explosion of the Medicare-eligible population, the program hasn’t kept up with coverages.” In addition, Medicare’s behemoth power as a government-run agency has ramifications that trickle down irrespective of a patient’s insurance carrier.

“Medicare sets the tone on price and reimbursement, and everyone follows suit,” Dr. Gupta said. “It’s a race to the bottom.”

“The program is great for patients when people need hospitalizations, skilled nursing, and physical therapy,” Dr. Gupta said. “But it’s not great about keeping people healthier and maintaining function via preventive treatments.” Many private insurers must become more adept at that too.

For instance, Dr. Gupta laments the lack of coverage for hearing aids, something his patients could greatly benefit from. Thanks to the Build Back Better bill, coverage of hearing aids will begin in 2024. But, again, most private insurers don’t cover hearing aids either. Some Medicare Advantage plans do.

Medicare doesn’t cover eye health (except for eye exams for diabetes patients), which is an issue for Daniel Laroche, MD, a glaucoma specialist and clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

“I get paid less for Medicare patients by about 20% because of ‘lesser-of’ payments,” said Dr. Laroche. For example, as per Medicare, after patients meet their Part B deductible, they pay 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for glaucoma testing. “It would be nice to get the full amount for Medicare patients.”

“In addition, getting approvals for testing takes time and exhaustive amounts of paperwork, says Adeeti Gupta, MD, a gynecologist and founder of Walk In GYN Care in New York.

“Medicare only covers gynecologist visits every 2 years after the age of 65,” she said. “Any additional testing requires authorization, and Medicare doesn’t cover hormone replacement at all, which really makes me crazy. They will cover Viagra for men, but they won’t cover HRT, which prolongs life, reduces dementia, and prevents bone loss.”

While these three doctors find Medicare lacking in its coverage of their specialty, and their reimbursements are too low, many physicians also find fault regarding Medicare billing, which can put their patients at risk.

The problem with Medicare billing

Because claims are processed by Medicare administrative contractors, it can take about a month for the approval or denial process and for doctors to receive reimbursement.

Prior authorizations, especially with Medicare Advantage plans, are also problematic. For example, one 2022 study found that 18% of payment denials were for services that met coverage and billing rules.

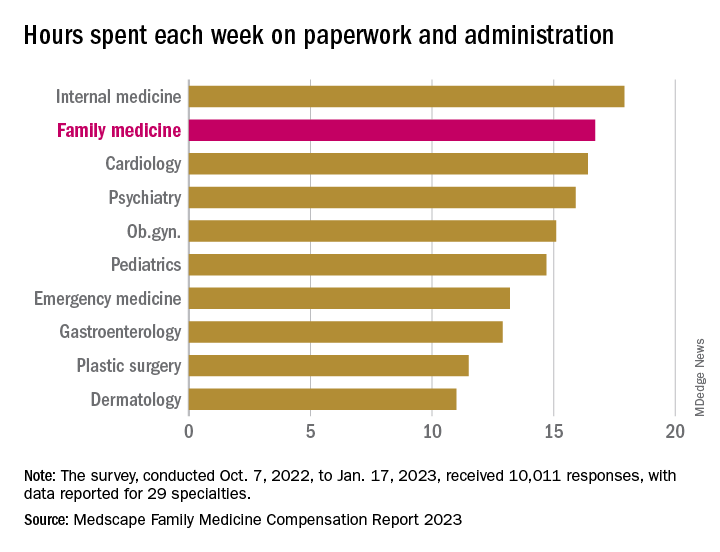

Worse, all of this jockeying for coverage takes time. The average health care provider spends 16.4 hours a week on paperwork and on securing prior authorizations to cover services, according to the American Medical Association.

“A good 40% of my time is exclusively Medicare red tape paperwork,” Rahul Gupta says. “There’s a reason I spend 2-3 hours a night catching up on that stuff.”

Not only does this lead to burnout, but it also means that most physicians must hire an administrator to help with the paperwork.

In comparison, industry averages put the denial rate for all Medicare and private insurance claims at 20%.

“Excessive authorization controls required by health insurers are persistently responsible for serious harm to physician practices and patients when necessary medical care is delayed, denied, or disrupted in an attempt to increase profits,” Dr. Laroche said.

“Our office spends nearly 2 days per week on prior authorizations, creating costly administrative burdens.”

For Adeeti Gupta, the frustrations with Medicare have continued to mount. “We’re just at a dead end,” she said. “Authorizations keep getting denied, and the back-end paperwork is only increasing for us.”

Will more doctors opt out of Medicare?

When doctors don’t accept Medicare, it hurts the patients using it, especially patients who have selected either a Medicare Advantage plan or who become eligible for Medicare at age 65 only to find that fewer doctors take the government-sponsored insurance than in the past.

As of 2020, only 1% of nonpediatric physicians had formally opted out, per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Psychiatrists account for the largest share of opt-outs (7.2%).

“Unfortunately, most doctors outside of hospital-based practices will reach a point when they can’t deal with Medicare paperwork, so they’ll stop taking it,” Rahul Gupta says.

A coalition of 120 physicians’ groups, including the American Medical Association, disputes that Medicare is paying a fair reimbursement rate to physicians and calls for an overhaul in how they adjust physician pay.

“Nothing much changes no matter how much the AMA shouts,” Rahul Gupta said in an interview.

What can doctors do

Prescription prices are another example of the challenges posed by Medicare. When prescriptions are denied because of Medicare’s medigap (or donut hole) program, which puts a cap on medication coverage, which was $4,660 in 2023, Dr. Gupta says she turns to alternative ways to fill them.

“I’ve been telling patients to pay out of pocket and use GoodRx, or we get medications compounded,” she said. “That’s cheaper. For example, for HRT, GoodRx can bring down the cost 40% to 50%.”

The American Medical Association as well as 150 other medical advocacy groups continue to urge Congress to work with the physician community to address the systematic problems within Medicare, especially reimbursement.

Despite the daily challenges, Rahul Gupta says he remains committed to caring for his patients.

“I want to care for the elderly, especially because they already have very few physicians to take care of them, and fortunately, I have a good practice with other coverages,” he said. “I can’t give up.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While physicians are getting less of a Medicare pay cut than they thought this year (Congress voted to cut Medicare payments by 2%, which was less than the expected 8.5%), Medicare still pays physicians only 80% of what many third-party insurers pay.

Moreover, those reimbursements are often slow to arrive, and the paperwork is burdensome. In fact, about 65% of doctors won’t accept new Medicare patients, down from 71% just 5 years ago, according to the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Worse, inflation makes continuous cuts feel even steeper and trickles down to physicians and their patients as more and more doctors become disenchanted and consider dropping Medicare.

Medicare at a glance

Medicare pays physicians about 80% of the “reasonable charge” for covered services. At the same time, private insurers pay nearly double Medicare rates for hospital services.

The Medicare fee schedule is released each year. Physicians who accept Medicare can choose to be a “participating provider” by agreeing to the fee schedule and to not charging more than this amount. “Nonparticipating” providers can charge up to 15% more. Physicians can also opt out of Medicare entirely.

The earliest that physicians receive their payment is 14 days after electronic filing to 28 days after paper filing, but it often can take months.

Physicians lose an estimated 7.3% of Medicare claims to billing problems. With private insurers, an estimated 4.8% is lost.

In 2000, there were 50 million Medicare enrollees; it is projected that by 2050, there will be 87 million enrollees.

Why are doctors disenchanted?

“When Medicare started, the concept of the program was good,” said Rahul Gupta, MD, a geriatrician in Westport, Conn., and chief of internal medicine at St. Vincent’s Medical Center, Bridgeport, Conn. “However, over the years, with new developments in medicine and the explosion of the Medicare-eligible population, the program hasn’t kept up with coverages.” In addition, Medicare’s behemoth power as a government-run agency has ramifications that trickle down irrespective of a patient’s insurance carrier.

“Medicare sets the tone on price and reimbursement, and everyone follows suit,” Dr. Gupta said. “It’s a race to the bottom.”

“The program is great for patients when people need hospitalizations, skilled nursing, and physical therapy,” Dr. Gupta said. “But it’s not great about keeping people healthier and maintaining function via preventive treatments.” Many private insurers must become more adept at that too.

For instance, Dr. Gupta laments the lack of coverage for hearing aids, something his patients could greatly benefit from. Thanks to the Build Back Better bill, coverage of hearing aids will begin in 2024. But, again, most private insurers don’t cover hearing aids either. Some Medicare Advantage plans do.

Medicare doesn’t cover eye health (except for eye exams for diabetes patients), which is an issue for Daniel Laroche, MD, a glaucoma specialist and clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

“I get paid less for Medicare patients by about 20% because of ‘lesser-of’ payments,” said Dr. Laroche. For example, as per Medicare, after patients meet their Part B deductible, they pay 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for glaucoma testing. “It would be nice to get the full amount for Medicare patients.”

“In addition, getting approvals for testing takes time and exhaustive amounts of paperwork, says Adeeti Gupta, MD, a gynecologist and founder of Walk In GYN Care in New York.

“Medicare only covers gynecologist visits every 2 years after the age of 65,” she said. “Any additional testing requires authorization, and Medicare doesn’t cover hormone replacement at all, which really makes me crazy. They will cover Viagra for men, but they won’t cover HRT, which prolongs life, reduces dementia, and prevents bone loss.”

While these three doctors find Medicare lacking in its coverage of their specialty, and their reimbursements are too low, many physicians also find fault regarding Medicare billing, which can put their patients at risk.

The problem with Medicare billing

Because claims are processed by Medicare administrative contractors, it can take about a month for the approval or denial process and for doctors to receive reimbursement.

Prior authorizations, especially with Medicare Advantage plans, are also problematic. For example, one 2022 study found that 18% of payment denials were for services that met coverage and billing rules.

Worse, all of this jockeying for coverage takes time. The average health care provider spends 16.4 hours a week on paperwork and on securing prior authorizations to cover services, according to the American Medical Association.

“A good 40% of my time is exclusively Medicare red tape paperwork,” Rahul Gupta says. “There’s a reason I spend 2-3 hours a night catching up on that stuff.”

Not only does this lead to burnout, but it also means that most physicians must hire an administrator to help with the paperwork.

In comparison, industry averages put the denial rate for all Medicare and private insurance claims at 20%.

“Excessive authorization controls required by health insurers are persistently responsible for serious harm to physician practices and patients when necessary medical care is delayed, denied, or disrupted in an attempt to increase profits,” Dr. Laroche said.

“Our office spends nearly 2 days per week on prior authorizations, creating costly administrative burdens.”

For Adeeti Gupta, the frustrations with Medicare have continued to mount. “We’re just at a dead end,” she said. “Authorizations keep getting denied, and the back-end paperwork is only increasing for us.”

Will more doctors opt out of Medicare?

When doctors don’t accept Medicare, it hurts the patients using it, especially patients who have selected either a Medicare Advantage plan or who become eligible for Medicare at age 65 only to find that fewer doctors take the government-sponsored insurance than in the past.

As of 2020, only 1% of nonpediatric physicians had formally opted out, per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Psychiatrists account for the largest share of opt-outs (7.2%).

“Unfortunately, most doctors outside of hospital-based practices will reach a point when they can’t deal with Medicare paperwork, so they’ll stop taking it,” Rahul Gupta says.

A coalition of 120 physicians’ groups, including the American Medical Association, disputes that Medicare is paying a fair reimbursement rate to physicians and calls for an overhaul in how they adjust physician pay.

“Nothing much changes no matter how much the AMA shouts,” Rahul Gupta said in an interview.

What can doctors do

Prescription prices are another example of the challenges posed by Medicare. When prescriptions are denied because of Medicare’s medigap (or donut hole) program, which puts a cap on medication coverage, which was $4,660 in 2023, Dr. Gupta says she turns to alternative ways to fill them.

“I’ve been telling patients to pay out of pocket and use GoodRx, or we get medications compounded,” she said. “That’s cheaper. For example, for HRT, GoodRx can bring down the cost 40% to 50%.”

The American Medical Association as well as 150 other medical advocacy groups continue to urge Congress to work with the physician community to address the systematic problems within Medicare, especially reimbursement.

Despite the daily challenges, Rahul Gupta says he remains committed to caring for his patients.

“I want to care for the elderly, especially because they already have very few physicians to take care of them, and fortunately, I have a good practice with other coverages,” he said. “I can’t give up.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care’s per-person costs for addressing social needs not covered by federal funding

The costs of providing evidence-based interventions in primary care to address social needs far exceed current federal funding streams, say the authors of a new analysis.

A microsimulation analysis by Sanjay Basu, MD, PhD, with Clinical Product Development, Waymark Care, San Francisco, and colleagues found that, as primary care practices are being asked to screen for social needs, the cost of providing evidence-based interventions for these needs averaged $60 per member/person per month (PMPM) (95% confidence interval, $55-$65).

However, less than half ($27) of the $60 cost had existing federal financing in place to pay for it. Of the $60, $5 was for screening and referral.

The study results were published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The researchers looked at key social needs areas and found major gaps between what interventions cost and what’s covered by federal payers. They demonstrate the gaps in four key areas. Many people in the analysis have more than one need:

- Food insecurity: Cost was $23 PMPM and the proportion borne by existing federal payers was 61.6%.

- Housing insecurity: Cost was $3 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers was 45.6%.

- Transportation insecurity: Cost was $0.1 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers was 27.8%.

- Community-based care coordination: Cost was $0.6 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers is 6.4%.

Gaps varied by type of center

Primary care practices were grouped into federally qualified health centers; non-FQHC urban practices in high-poverty areas; non-FQHC rural practices in high-poverty areas; and practices in lower-poverty areas. Gaps varied among the groups.

While disproportionate funding was available to populations seen at FQHCs, populations seen at non-FQHC practices in high-poverty areas had larger funding gaps.

The study population consisted of 19,225 patients seen in primary care practices; data on social needs were pulled from the National Center for Health Statistics from 2015 to 2018.

Dr. Basu said in an interview with the journal’s deputy editor, Mitchell Katz, MD, that new sustainable revenue streams need to be identified to close the gap. Primary care physicians should not be charged with tasks such as researching the best housing programs and food benefits.

“I can’t imagine fitting this into my primary care appointments,” he said.

Is primary care the best setting for addressing these needs?

In an accompanying comment, Jenifer Clapp, MPA, with the Office of Ambulatory Care and Population Health, NYC Health + Hospitals, New York, and colleagues wrote that the study raises the question of whether the health care setting is the right place for addressing social needs. Some aspects have to be addressed in health care, such as asking about the home environment for a patient with environmentally triggered asthma.

“But how involved should health care professionals be in identifying needs unrelated to illness and solving those needs?” Ms. Clapp and colleagues asked.

They wrote that the health care sector in the United States must address these needs because in the United States, unlike in many European countries, “there is an insufficient social service sector to address the basic human needs of children and working-age adults.”

Eligible but not enrolled

Importantly, both the study authors and editorialists pointed out, in many cases, intervening doesn’t mean paying for the social services, but helping patients enroll in the services for which they already qualify.

The study authors wrote that among people who had food and housing needs, most met the criteria for federally funded programs, but had low enrollment for reasons including inadequate program capacity.

For example, 78% of people with housing needs were eligible for federal programs but only 24% were enrolled, and 95.6% of people with food needs were eligible for programs but only 70.2% were enrolled in programs like the Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program and Women, Infants and Children.

Commentary coauthor Nichola Davis, MD, also with NYC Health + Hospitals, said one thing they’ve done at NYC Health + Hospitals is partner with community-based organizations that provide food navigators so when patients screen positive for food insecurity they can then be seen by a food navigator to pinpoint appropriate programs.

The referral for those who indicate food insecurity is automatically generated by the electronic health system and appears on the after-visit summary.

“At the bare minimum, the patient would leave with a list of resources,” Dr. Davis said.

One place primary care providers can make a difference

Dr. Katz said that the $60 cost per person is much lower than that for a service such as an MRI.

“We should be able to achieve that,” he said.

Will Bleser, PhD, MSPH, assistant research director of health care transformation for social needs and health equity at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, Washington, said it’s exciting to see the per-person cost for social needs quantified.

He pointed to existing revenue options that have been underutilized.

Through Medicare, he noted, if you are part of a Medicare Advantage plan, there is a program implemented in 2020 called Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill. “That authorizes Medicare Advantage plans to offer non–primarily health-related services through Medicare Advantage to individuals who meet certain chronic illness conditions.”

Non–primarily health-related services may include meals, transportation, and pest control, for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services notes.

Also, within the shared-savings program of traditional Medicare, if an accountable care organization is providing quality care under the cost target and is reaping the savings, “you could use those bonuses to do things that you couldn’t do under the normal Medicare fee schedule like address social needs,” Dr. Bleser said.

Medicaid, he said, offers the most opportunities to address social needs through the health system. One policy mechanism within Medicaid is the Section 1115 Waiver, where states can propose to provide new services as long as they comply with the core rules of Medicaid and meet certain qualifications.

Avoiding checking boxes with no benefit to patients

Ms. Clapp and colleagues noted that whether health care professionals agree that social needs can or should be addressed in primary care, CMS will mandate social needs screening and reporting for all hospitalized adults starting in 2024. Additionally, the Joint Commission will require health care systems to gauge social needs and report on resources.

“We need to ensure that these mandates do not become administrative checkboxes that frustrate clinical staff and ratchet up health care costs with no benefit to patients,” they wrote.

Dr. Basu reported receiving personal fees from the University of California, Healthright360, Waymark and Collective Health outside the submitted work; he has a patent issued for a multimodel member outreach system; and a patent pending for operationalizing predicted changes in risk based on interventions. A coauthor reported grants from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina, and personal fees from several nonprofit organizations outside the submitted work. Another coauthor reported personal fees from ZealCare outside the submitted work.

The costs of providing evidence-based interventions in primary care to address social needs far exceed current federal funding streams, say the authors of a new analysis.

A microsimulation analysis by Sanjay Basu, MD, PhD, with Clinical Product Development, Waymark Care, San Francisco, and colleagues found that, as primary care practices are being asked to screen for social needs, the cost of providing evidence-based interventions for these needs averaged $60 per member/person per month (PMPM) (95% confidence interval, $55-$65).

However, less than half ($27) of the $60 cost had existing federal financing in place to pay for it. Of the $60, $5 was for screening and referral.

The study results were published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The researchers looked at key social needs areas and found major gaps between what interventions cost and what’s covered by federal payers. They demonstrate the gaps in four key areas. Many people in the analysis have more than one need:

- Food insecurity: Cost was $23 PMPM and the proportion borne by existing federal payers was 61.6%.

- Housing insecurity: Cost was $3 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers was 45.6%.

- Transportation insecurity: Cost was $0.1 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers was 27.8%.

- Community-based care coordination: Cost was $0.6 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers is 6.4%.

Gaps varied by type of center

Primary care practices were grouped into federally qualified health centers; non-FQHC urban practices in high-poverty areas; non-FQHC rural practices in high-poverty areas; and practices in lower-poverty areas. Gaps varied among the groups.

While disproportionate funding was available to populations seen at FQHCs, populations seen at non-FQHC practices in high-poverty areas had larger funding gaps.

The study population consisted of 19,225 patients seen in primary care practices; data on social needs were pulled from the National Center for Health Statistics from 2015 to 2018.

Dr. Basu said in an interview with the journal’s deputy editor, Mitchell Katz, MD, that new sustainable revenue streams need to be identified to close the gap. Primary care physicians should not be charged with tasks such as researching the best housing programs and food benefits.

“I can’t imagine fitting this into my primary care appointments,” he said.

Is primary care the best setting for addressing these needs?

In an accompanying comment, Jenifer Clapp, MPA, with the Office of Ambulatory Care and Population Health, NYC Health + Hospitals, New York, and colleagues wrote that the study raises the question of whether the health care setting is the right place for addressing social needs. Some aspects have to be addressed in health care, such as asking about the home environment for a patient with environmentally triggered asthma.

“But how involved should health care professionals be in identifying needs unrelated to illness and solving those needs?” Ms. Clapp and colleagues asked.

They wrote that the health care sector in the United States must address these needs because in the United States, unlike in many European countries, “there is an insufficient social service sector to address the basic human needs of children and working-age adults.”

Eligible but not enrolled

Importantly, both the study authors and editorialists pointed out, in many cases, intervening doesn’t mean paying for the social services, but helping patients enroll in the services for which they already qualify.

The study authors wrote that among people who had food and housing needs, most met the criteria for federally funded programs, but had low enrollment for reasons including inadequate program capacity.

For example, 78% of people with housing needs were eligible for federal programs but only 24% were enrolled, and 95.6% of people with food needs were eligible for programs but only 70.2% were enrolled in programs like the Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program and Women, Infants and Children.

Commentary coauthor Nichola Davis, MD, also with NYC Health + Hospitals, said one thing they’ve done at NYC Health + Hospitals is partner with community-based organizations that provide food navigators so when patients screen positive for food insecurity they can then be seen by a food navigator to pinpoint appropriate programs.

The referral for those who indicate food insecurity is automatically generated by the electronic health system and appears on the after-visit summary.

“At the bare minimum, the patient would leave with a list of resources,” Dr. Davis said.

One place primary care providers can make a difference

Dr. Katz said that the $60 cost per person is much lower than that for a service such as an MRI.

“We should be able to achieve that,” he said.

Will Bleser, PhD, MSPH, assistant research director of health care transformation for social needs and health equity at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, Washington, said it’s exciting to see the per-person cost for social needs quantified.

He pointed to existing revenue options that have been underutilized.

Through Medicare, he noted, if you are part of a Medicare Advantage plan, there is a program implemented in 2020 called Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill. “That authorizes Medicare Advantage plans to offer non–primarily health-related services through Medicare Advantage to individuals who meet certain chronic illness conditions.”

Non–primarily health-related services may include meals, transportation, and pest control, for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services notes.

Also, within the shared-savings program of traditional Medicare, if an accountable care organization is providing quality care under the cost target and is reaping the savings, “you could use those bonuses to do things that you couldn’t do under the normal Medicare fee schedule like address social needs,” Dr. Bleser said.

Medicaid, he said, offers the most opportunities to address social needs through the health system. One policy mechanism within Medicaid is the Section 1115 Waiver, where states can propose to provide new services as long as they comply with the core rules of Medicaid and meet certain qualifications.

Avoiding checking boxes with no benefit to patients

Ms. Clapp and colleagues noted that whether health care professionals agree that social needs can or should be addressed in primary care, CMS will mandate social needs screening and reporting for all hospitalized adults starting in 2024. Additionally, the Joint Commission will require health care systems to gauge social needs and report on resources.

“We need to ensure that these mandates do not become administrative checkboxes that frustrate clinical staff and ratchet up health care costs with no benefit to patients,” they wrote.

Dr. Basu reported receiving personal fees from the University of California, Healthright360, Waymark and Collective Health outside the submitted work; he has a patent issued for a multimodel member outreach system; and a patent pending for operationalizing predicted changes in risk based on interventions. A coauthor reported grants from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina, and personal fees from several nonprofit organizations outside the submitted work. Another coauthor reported personal fees from ZealCare outside the submitted work.

The costs of providing evidence-based interventions in primary care to address social needs far exceed current federal funding streams, say the authors of a new analysis.

A microsimulation analysis by Sanjay Basu, MD, PhD, with Clinical Product Development, Waymark Care, San Francisco, and colleagues found that, as primary care practices are being asked to screen for social needs, the cost of providing evidence-based interventions for these needs averaged $60 per member/person per month (PMPM) (95% confidence interval, $55-$65).

However, less than half ($27) of the $60 cost had existing federal financing in place to pay for it. Of the $60, $5 was for screening and referral.

The study results were published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The researchers looked at key social needs areas and found major gaps between what interventions cost and what’s covered by federal payers. They demonstrate the gaps in four key areas. Many people in the analysis have more than one need:

- Food insecurity: Cost was $23 PMPM and the proportion borne by existing federal payers was 61.6%.

- Housing insecurity: Cost was $3 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers was 45.6%.

- Transportation insecurity: Cost was $0.1 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers was 27.8%.

- Community-based care coordination: Cost was $0.6 PMPM; proportion borne by federal payers is 6.4%.

Gaps varied by type of center

Primary care practices were grouped into federally qualified health centers; non-FQHC urban practices in high-poverty areas; non-FQHC rural practices in high-poverty areas; and practices in lower-poverty areas. Gaps varied among the groups.

While disproportionate funding was available to populations seen at FQHCs, populations seen at non-FQHC practices in high-poverty areas had larger funding gaps.

The study population consisted of 19,225 patients seen in primary care practices; data on social needs were pulled from the National Center for Health Statistics from 2015 to 2018.

Dr. Basu said in an interview with the journal’s deputy editor, Mitchell Katz, MD, that new sustainable revenue streams need to be identified to close the gap. Primary care physicians should not be charged with tasks such as researching the best housing programs and food benefits.

“I can’t imagine fitting this into my primary care appointments,” he said.

Is primary care the best setting for addressing these needs?

In an accompanying comment, Jenifer Clapp, MPA, with the Office of Ambulatory Care and Population Health, NYC Health + Hospitals, New York, and colleagues wrote that the study raises the question of whether the health care setting is the right place for addressing social needs. Some aspects have to be addressed in health care, such as asking about the home environment for a patient with environmentally triggered asthma.

“But how involved should health care professionals be in identifying needs unrelated to illness and solving those needs?” Ms. Clapp and colleagues asked.

They wrote that the health care sector in the United States must address these needs because in the United States, unlike in many European countries, “there is an insufficient social service sector to address the basic human needs of children and working-age adults.”

Eligible but not enrolled

Importantly, both the study authors and editorialists pointed out, in many cases, intervening doesn’t mean paying for the social services, but helping patients enroll in the services for which they already qualify.

The study authors wrote that among people who had food and housing needs, most met the criteria for federally funded programs, but had low enrollment for reasons including inadequate program capacity.

For example, 78% of people with housing needs were eligible for federal programs but only 24% were enrolled, and 95.6% of people with food needs were eligible for programs but only 70.2% were enrolled in programs like the Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program and Women, Infants and Children.

Commentary coauthor Nichola Davis, MD, also with NYC Health + Hospitals, said one thing they’ve done at NYC Health + Hospitals is partner with community-based organizations that provide food navigators so when patients screen positive for food insecurity they can then be seen by a food navigator to pinpoint appropriate programs.

The referral for those who indicate food insecurity is automatically generated by the electronic health system and appears on the after-visit summary.

“At the bare minimum, the patient would leave with a list of resources,” Dr. Davis said.

One place primary care providers can make a difference

Dr. Katz said that the $60 cost per person is much lower than that for a service such as an MRI.

“We should be able to achieve that,” he said.

Will Bleser, PhD, MSPH, assistant research director of health care transformation for social needs and health equity at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, Washington, said it’s exciting to see the per-person cost for social needs quantified.

He pointed to existing revenue options that have been underutilized.

Through Medicare, he noted, if you are part of a Medicare Advantage plan, there is a program implemented in 2020 called Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill. “That authorizes Medicare Advantage plans to offer non–primarily health-related services through Medicare Advantage to individuals who meet certain chronic illness conditions.”

Non–primarily health-related services may include meals, transportation, and pest control, for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services notes.

Also, within the shared-savings program of traditional Medicare, if an accountable care organization is providing quality care under the cost target and is reaping the savings, “you could use those bonuses to do things that you couldn’t do under the normal Medicare fee schedule like address social needs,” Dr. Bleser said.

Medicaid, he said, offers the most opportunities to address social needs through the health system. One policy mechanism within Medicaid is the Section 1115 Waiver, where states can propose to provide new services as long as they comply with the core rules of Medicaid and meet certain qualifications.

Avoiding checking boxes with no benefit to patients

Ms. Clapp and colleagues noted that whether health care professionals agree that social needs can or should be addressed in primary care, CMS will mandate social needs screening and reporting for all hospitalized adults starting in 2024. Additionally, the Joint Commission will require health care systems to gauge social needs and report on resources.

“We need to ensure that these mandates do not become administrative checkboxes that frustrate clinical staff and ratchet up health care costs with no benefit to patients,” they wrote.

Dr. Basu reported receiving personal fees from the University of California, Healthright360, Waymark and Collective Health outside the submitted work; he has a patent issued for a multimodel member outreach system; and a patent pending for operationalizing predicted changes in risk based on interventions. A coauthor reported grants from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina, and personal fees from several nonprofit organizations outside the submitted work. Another coauthor reported personal fees from ZealCare outside the submitted work.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

As Medicaid purge begins, ‘staggering numbers’ of Americans lose coverage

More than 600,000 Americans have lost Medicaid coverage since pandemic protections ended on April 1. And a KFF Health News analysis of state data shows the vast majority were removed from state rolls for not completing paperwork.

Under normal circumstances, states review their Medicaid enrollment lists regularly to ensure every recipient qualifies for coverage. But because of a nationwide pause in those reviews during the pandemic, the health insurance program for low-income and disabled Americans kept people covered even if they no longer qualified.

Now, in what’s known as the Medicaid unwinding, states are combing through rolls and deciding who stays and who goes. People who are no longer eligible or don’t complete paperwork in time will be dropped.

The overwhelming majority of people who have lost coverage in most states were dropped because of technicalities, not because state officials determined they no longer meet Medicaid income limits. Four out of every five people dropped so far either never returned the paperwork or omitted required documents, according to a KFF Health News analysis of data from 11 states that provided details on recent cancellations. Now, lawmakers and advocates are expressing alarm over the volume of people losing coverage and, in some states, calling to pause the process.

KFF Health News sought data from the 19 states that started cancellations by May 1. Based on records from 14 states that provided detailed numbers, either in response to a public records request or by posting online, 36% of people whose eligibility was reviewed have been disenrolled.

In Indiana, 53,000 residents lost coverage in the first month of the unwinding, 89% for procedural reasons like not returning renewal forms. State Rep. Ed Clere, a Republican, expressed dismay at those “staggering numbers” in a May 24 Medicaid advisory group meeting, repeatedly questioning state officials about forms mailed to out-of-date addresses and urging them to give people more than 2 weeks’ notice before canceling their coverage.

Rep. Clere warned that the cancellations set in motion an avoidable revolving door. Some people dropped from Medicaid will have to forgo filling prescriptions and cancel doctor visits because they can’t afford care. Months down the line, after untreated chronic illnesses spiral out of control, they’ll end up in the emergency room where social workers will need to again help them join the program, he said.

Before the unwinding, more than one in four Americans – 93 million – were covered by Medicaid or CHIP, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, according to KFF Health News’ analysis of the latest enrollment data. Half of all kids are covered by the programs.

About 15 million people will be dropped over the next year as states review participants’ eligibility in monthly tranches.

Most people will find health coverage through new jobs or qualify for subsidized plans through the Affordable Care Act. But millions of others, including many children, will become uninsured and unable to afford basic prescriptions or preventive care. The uninsured rate among those under 65 is projected to rise from a historical low of 8.3% today to 9.3% next year, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Because each state is handling the unwinding differently, the share of enrollees dropped in the first weeks varies widely.

Several states are first reviewing people officials believe are no longer eligible or who haven’t recently used their insurance. High cancellation rates in those states should level out as the agencies move on to people who likely still qualify.

In Utah, nearly 56% of people included in early reviews were dropped. In New Hampshire, 44% received cancellation letters within the first 2 months – almost all for procedural reasons, like not returning paperwork.

But New Hampshire officials found that thousands of people who didn’t fill out the forms indeed earn too much to qualify, according to Henry Lipman, the state’s Medicaid director. They would have been denied anyway. Even so, more people than he expected are not returning renewal forms. “That tells us that we need to change up our strategy,” said Mr. Lipman.

In other states, like Virginia and Nebraska, which aren’t prioritizing renewals by likely eligibility, about 90% have been renewed.

Because of the 3-year pause in renewals, many people on Medicaid have never been through the process or aren’t aware they may need to fill out long verification forms, as a recent KFF poll found. Some people moved and didn’t update their contact information.

And while agencies are required to assist enrollees who don’t speak English well, many are sending the forms in only a few common languages.

Tens of thousands of children are losing coverage, as researchers have warned, even though some may still qualify for Medicaid or CHIP. In its first month of reviews, South Dakota ended coverage for 10% of all Medicaid and CHIP enrollees in the state. More than half of them were children. In Arkansas, about 40% were kids.

Many parents don’t know that limits on household income are significantly higher for children than adults. Parents should fill out renewal forms even if they don’t qualify themselves, said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, Washington.

New Hampshire has moved most families with children to the end of the review process. Mr. Lipman said his biggest worry is that a child will end up uninsured. Florida also planned to push kids with serious health conditions and other vulnerable groups to the end of the review line.

But according to Miriam Harmatz, advocacy director and founder of the Florida Health Justice Project, state officials sent cancellation letters to several clients with disabled children who probably still qualify. She’s helping those families appeal.

Nearly 250,000 Floridians reviewed in the first month of the unwinding lost coverage, 82% of them for reasons like incomplete paperwork, the state reported to federal authorities. House Democrats from the state petitioned Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis to pause the unwinding.

Advocacy coalitions in both Florida and Arkansas also have called for investigations into the review process and a pause on cancellations.

The state is contacting enrollees by phone, email, and text, and continues to process late applications, said Tori Cuddy, a spokesperson for the Florida Department of Children and Families. Ms. Cuddy did not respond to questions about issues raised in the petitions.

Federal officials are investigating those complaints and any other problems that emerge, said Dan Tsai, director of the Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services. “If we find that the rules are not being followed, we will take action.”

His agency has directed states to automatically reenroll residents using data from other government programs like unemployment and food assistance when possible. Anyone who can’t be approved through that process must act quickly.

“For the past 3 years, people have been told to ignore the mail around this, that the renewal was not going to lead to a termination.” Suddenly that mail matters, he said.

Federal law requires states to tell people why they’re losing Medicaid coverage and how to appeal the decision.

Ms. Harmatz said some cancellation notices in Florida are vague and could violate due process rules. Letters that she’s seen say “your Medicaid for this period is ending” rather than providing a specific reason for disenrollment, like having too high an income or incomplete paperwork.

If a person requests a hearing before their cancellation takes effect, they can stay covered during the appeals process. Even after being disenrolled, many still have a 90-day window to restore coverage.

In New Hampshire, 13% of people deemed ineligible in the first month have asked for extra time to provide the necessary records. “If you’re eligible for Medicaid, we don’t want you to lose it,” said Mr. Lipman.

Rep. Clere pushed Indiana’s Medicaid officials during the May meeting to immediately make changes to avoid people unnecessarily becoming uninsured. One official responded that they’ll learn and improve over time.

“I’m just concerned that we’re going to be ‘learning’ as a result of people losing coverage,” Rep. Clere replied. “So I don’t want to learn at their expense.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

More than 600,000 Americans have lost Medicaid coverage since pandemic protections ended on April 1. And a KFF Health News analysis of state data shows the vast majority were removed from state rolls for not completing paperwork.

Under normal circumstances, states review their Medicaid enrollment lists regularly to ensure every recipient qualifies for coverage. But because of a nationwide pause in those reviews during the pandemic, the health insurance program for low-income and disabled Americans kept people covered even if they no longer qualified.

Now, in what’s known as the Medicaid unwinding, states are combing through rolls and deciding who stays and who goes. People who are no longer eligible or don’t complete paperwork in time will be dropped.

The overwhelming majority of people who have lost coverage in most states were dropped because of technicalities, not because state officials determined they no longer meet Medicaid income limits. Four out of every five people dropped so far either never returned the paperwork or omitted required documents, according to a KFF Health News analysis of data from 11 states that provided details on recent cancellations. Now, lawmakers and advocates are expressing alarm over the volume of people losing coverage and, in some states, calling to pause the process.

KFF Health News sought data from the 19 states that started cancellations by May 1. Based on records from 14 states that provided detailed numbers, either in response to a public records request or by posting online, 36% of people whose eligibility was reviewed have been disenrolled.

In Indiana, 53,000 residents lost coverage in the first month of the unwinding, 89% for procedural reasons like not returning renewal forms. State Rep. Ed Clere, a Republican, expressed dismay at those “staggering numbers” in a May 24 Medicaid advisory group meeting, repeatedly questioning state officials about forms mailed to out-of-date addresses and urging them to give people more than 2 weeks’ notice before canceling their coverage.

Rep. Clere warned that the cancellations set in motion an avoidable revolving door. Some people dropped from Medicaid will have to forgo filling prescriptions and cancel doctor visits because they can’t afford care. Months down the line, after untreated chronic illnesses spiral out of control, they’ll end up in the emergency room where social workers will need to again help them join the program, he said.

Before the unwinding, more than one in four Americans – 93 million – were covered by Medicaid or CHIP, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, according to KFF Health News’ analysis of the latest enrollment data. Half of all kids are covered by the programs.

About 15 million people will be dropped over the next year as states review participants’ eligibility in monthly tranches.

Most people will find health coverage through new jobs or qualify for subsidized plans through the Affordable Care Act. But millions of others, including many children, will become uninsured and unable to afford basic prescriptions or preventive care. The uninsured rate among those under 65 is projected to rise from a historical low of 8.3% today to 9.3% next year, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Because each state is handling the unwinding differently, the share of enrollees dropped in the first weeks varies widely.

Several states are first reviewing people officials believe are no longer eligible or who haven’t recently used their insurance. High cancellation rates in those states should level out as the agencies move on to people who likely still qualify.

In Utah, nearly 56% of people included in early reviews were dropped. In New Hampshire, 44% received cancellation letters within the first 2 months – almost all for procedural reasons, like not returning paperwork.

But New Hampshire officials found that thousands of people who didn’t fill out the forms indeed earn too much to qualify, according to Henry Lipman, the state’s Medicaid director. They would have been denied anyway. Even so, more people than he expected are not returning renewal forms. “That tells us that we need to change up our strategy,” said Mr. Lipman.

In other states, like Virginia and Nebraska, which aren’t prioritizing renewals by likely eligibility, about 90% have been renewed.

Because of the 3-year pause in renewals, many people on Medicaid have never been through the process or aren’t aware they may need to fill out long verification forms, as a recent KFF poll found. Some people moved and didn’t update their contact information.

And while agencies are required to assist enrollees who don’t speak English well, many are sending the forms in only a few common languages.

Tens of thousands of children are losing coverage, as researchers have warned, even though some may still qualify for Medicaid or CHIP. In its first month of reviews, South Dakota ended coverage for 10% of all Medicaid and CHIP enrollees in the state. More than half of them were children. In Arkansas, about 40% were kids.

Many parents don’t know that limits on household income are significantly higher for children than adults. Parents should fill out renewal forms even if they don’t qualify themselves, said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, Washington.