User login

Circadian curiosities

Summer is here. Well, technically not for 3 weeks, but in Phoenix summer as a weather condition generally runs from March to November.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (yes, the one you learned in neuroanatomy) is pretty tiny, but still remarkable. Nothing brings that into focus like the changing of the seasons.

No matter where you live on Earth, you still have to deal with day and night, even if each is 6 months long. We all have to live with shifting schedules and lengths of night and day and weekdays and weekends.

But what fascinates me is how the internal clock reprograms itself, and then doesn’t change.

Case in point: Except for when I’ve had to catch a flight, I haven’t set an alarm in almost 10 years. Somewhere early in my career (back when I did a lot of hospital work) I began getting up between 4-5 a.m. to start rounds before going to the office.

Today the habit continues. It’s been 14 years since I last did weekday hospital call but I still automatically wake up, ready to go, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Monday through Friday. Without me having to do anything this shuts off on vacations, holidays, and weekends, but is up and running as soon as I have to go back to the office.

It’s fascinating (at least to me) in that the suprachiasmatic nucleus didn’t evolve many millions of years ago so I could get to work without an alarm clock. Early animals needed to respond to changing conditions of night, day, and shifting seasons. Light and dark are universal for almost everything that walks, flies, and swims, so given enough time a way of internally keeping track of them developed. Bears use it to hibernate. Birds to migrate with the seasons.

Of course, it’s not all good. In some people it’s likely behind the bizarre predictability of their cluster headaches.

In the modern era we’ve also found ways to confuse it, with the invention of time zones and air travel. Anyone who’s made the leap across several time zones has had to adjust. It’s certainly not a major issue, but does take some getting used to.

But still, it’s pretty fascinating stuff. A reminder that,

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Summer is here. Well, technically not for 3 weeks, but in Phoenix summer as a weather condition generally runs from March to November.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (yes, the one you learned in neuroanatomy) is pretty tiny, but still remarkable. Nothing brings that into focus like the changing of the seasons.

No matter where you live on Earth, you still have to deal with day and night, even if each is 6 months long. We all have to live with shifting schedules and lengths of night and day and weekdays and weekends.

But what fascinates me is how the internal clock reprograms itself, and then doesn’t change.

Case in point: Except for when I’ve had to catch a flight, I haven’t set an alarm in almost 10 years. Somewhere early in my career (back when I did a lot of hospital work) I began getting up between 4-5 a.m. to start rounds before going to the office.

Today the habit continues. It’s been 14 years since I last did weekday hospital call but I still automatically wake up, ready to go, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Monday through Friday. Without me having to do anything this shuts off on vacations, holidays, and weekends, but is up and running as soon as I have to go back to the office.

It’s fascinating (at least to me) in that the suprachiasmatic nucleus didn’t evolve many millions of years ago so I could get to work without an alarm clock. Early animals needed to respond to changing conditions of night, day, and shifting seasons. Light and dark are universal for almost everything that walks, flies, and swims, so given enough time a way of internally keeping track of them developed. Bears use it to hibernate. Birds to migrate with the seasons.

Of course, it’s not all good. In some people it’s likely behind the bizarre predictability of their cluster headaches.

In the modern era we’ve also found ways to confuse it, with the invention of time zones and air travel. Anyone who’s made the leap across several time zones has had to adjust. It’s certainly not a major issue, but does take some getting used to.

But still, it’s pretty fascinating stuff. A reminder that,

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Summer is here. Well, technically not for 3 weeks, but in Phoenix summer as a weather condition generally runs from March to November.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (yes, the one you learned in neuroanatomy) is pretty tiny, but still remarkable. Nothing brings that into focus like the changing of the seasons.

No matter where you live on Earth, you still have to deal with day and night, even if each is 6 months long. We all have to live with shifting schedules and lengths of night and day and weekdays and weekends.

But what fascinates me is how the internal clock reprograms itself, and then doesn’t change.

Case in point: Except for when I’ve had to catch a flight, I haven’t set an alarm in almost 10 years. Somewhere early in my career (back when I did a lot of hospital work) I began getting up between 4-5 a.m. to start rounds before going to the office.

Today the habit continues. It’s been 14 years since I last did weekday hospital call but I still automatically wake up, ready to go, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Monday through Friday. Without me having to do anything this shuts off on vacations, holidays, and weekends, but is up and running as soon as I have to go back to the office.

It’s fascinating (at least to me) in that the suprachiasmatic nucleus didn’t evolve many millions of years ago so I could get to work without an alarm clock. Early animals needed to respond to changing conditions of night, day, and shifting seasons. Light and dark are universal for almost everything that walks, flies, and swims, so given enough time a way of internally keeping track of them developed. Bears use it to hibernate. Birds to migrate with the seasons.

Of course, it’s not all good. In some people it’s likely behind the bizarre predictability of their cluster headaches.

In the modern era we’ve also found ways to confuse it, with the invention of time zones and air travel. Anyone who’s made the leap across several time zones has had to adjust. It’s certainly not a major issue, but does take some getting used to.

But still, it’s pretty fascinating stuff. A reminder that,

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Internists in 2022: Increased earnings can’t stop rising dissatisfaction

Internists experienced many of the usual ups and downs regarding nonclinical matters in 2022: Compensation was up, but satisfaction with compensation was down; the percentage of internists who would choose another specialty was up and time spent on paperwork and administration was down only slightly.

A year that began with the COVID-19 Omicron surge ended with many of the same old issues regaining the attention of physicians, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual compensation survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

“Decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” one physician wrote, and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

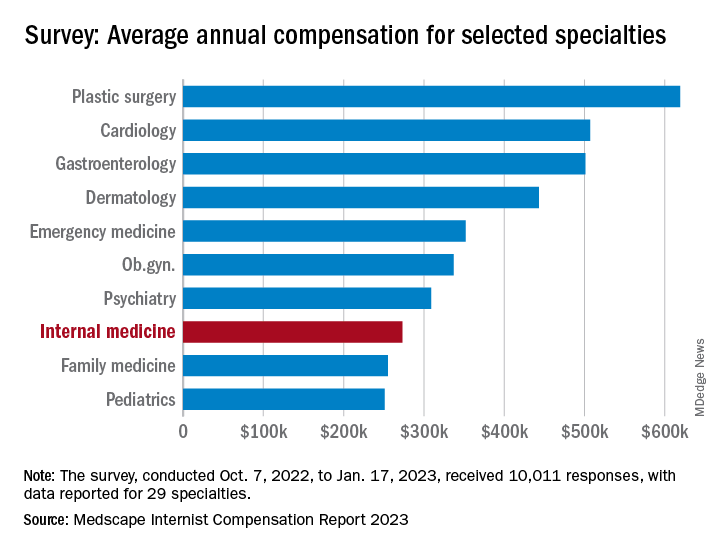

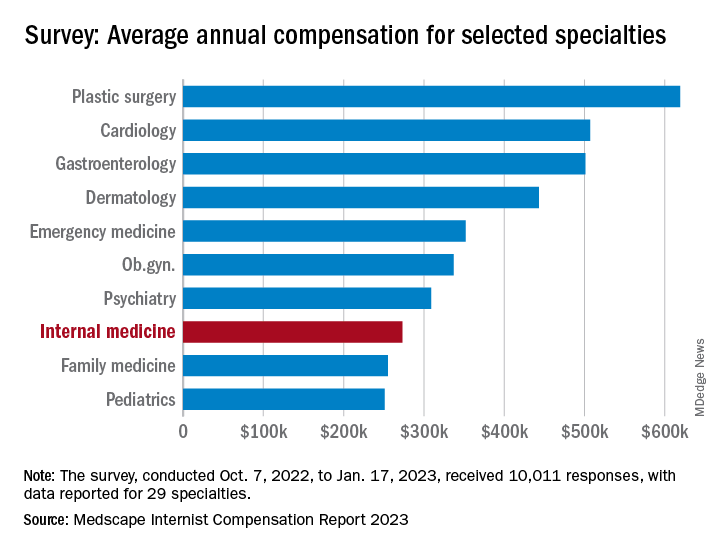

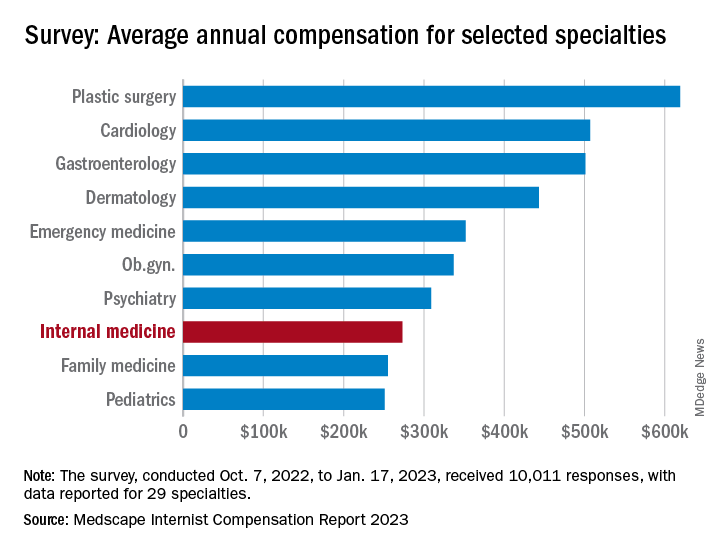

For internists at least, some of the survey results were positive. For the 13% of the 10,011 respondents who practice internal medicine, average compensation went from $264,000 in 2021 to $273,000 in 2022, an increase of almost 4% that matched the average for all physicians. Among the other primary care specialists, pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, but ob.gyns. and family physicians only managed to keep their 2022 earnings at 2021 levels.

Overall physician compensation for 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The latest increase in earnings among internists also included a decline: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 24% in 2021 to 16% in 2022. The gap was slightly larger for all physicians in 2022, with men earning about 19% more than women, and larger again among specialists at 27%, but both of those figures are lower than in recent years, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, however, was not high for internists: Only 43% feel that they are fairly paid, coming in above only ophthalmology (42%) and infectious diseases (35%) and well below psychiatry (68%) at the top of the list, the Medscape data show. In the 2022 report, 49% of internists said that they had been fairly paid.

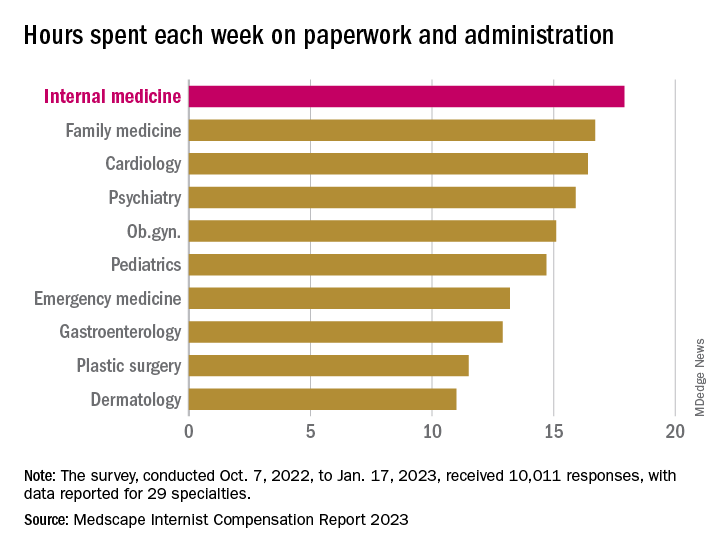

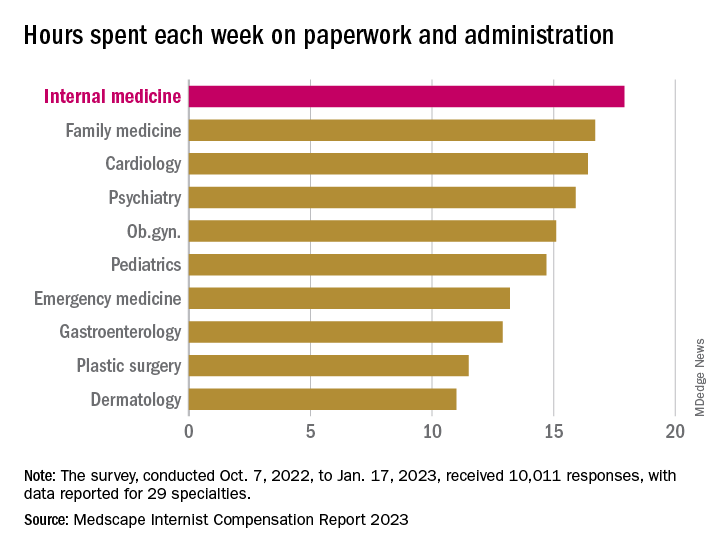

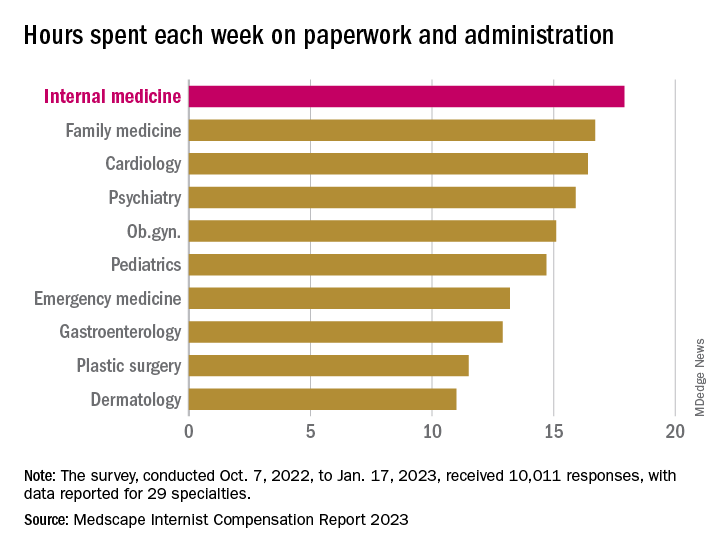

In another source of potential dissatisfaction, internist respondents reported spending an average of 17.9 hours each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) and well above anesthesiology, which was the lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said. A small bright spot comes in the form of a decline from the internists’ time of 18.7 hours per week in 2021.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of internist respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed internists to be the least likely of the 29 included specialties to follow the same path, with 61% (down from 63% in 2022) approving their initial selection, versus 97% for plastic surgeons, Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

Internists experienced many of the usual ups and downs regarding nonclinical matters in 2022: Compensation was up, but satisfaction with compensation was down; the percentage of internists who would choose another specialty was up and time spent on paperwork and administration was down only slightly.

A year that began with the COVID-19 Omicron surge ended with many of the same old issues regaining the attention of physicians, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual compensation survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

“Decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” one physician wrote, and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

For internists at least, some of the survey results were positive. For the 13% of the 10,011 respondents who practice internal medicine, average compensation went from $264,000 in 2021 to $273,000 in 2022, an increase of almost 4% that matched the average for all physicians. Among the other primary care specialists, pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, but ob.gyns. and family physicians only managed to keep their 2022 earnings at 2021 levels.

Overall physician compensation for 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The latest increase in earnings among internists also included a decline: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 24% in 2021 to 16% in 2022. The gap was slightly larger for all physicians in 2022, with men earning about 19% more than women, and larger again among specialists at 27%, but both of those figures are lower than in recent years, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, however, was not high for internists: Only 43% feel that they are fairly paid, coming in above only ophthalmology (42%) and infectious diseases (35%) and well below psychiatry (68%) at the top of the list, the Medscape data show. In the 2022 report, 49% of internists said that they had been fairly paid.

In another source of potential dissatisfaction, internist respondents reported spending an average of 17.9 hours each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) and well above anesthesiology, which was the lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said. A small bright spot comes in the form of a decline from the internists’ time of 18.7 hours per week in 2021.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of internist respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed internists to be the least likely of the 29 included specialties to follow the same path, with 61% (down from 63% in 2022) approving their initial selection, versus 97% for plastic surgeons, Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

Internists experienced many of the usual ups and downs regarding nonclinical matters in 2022: Compensation was up, but satisfaction with compensation was down; the percentage of internists who would choose another specialty was up and time spent on paperwork and administration was down only slightly.

A year that began with the COVID-19 Omicron surge ended with many of the same old issues regaining the attention of physicians, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual compensation survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

“Decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” one physician wrote, and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

For internists at least, some of the survey results were positive. For the 13% of the 10,011 respondents who practice internal medicine, average compensation went from $264,000 in 2021 to $273,000 in 2022, an increase of almost 4% that matched the average for all physicians. Among the other primary care specialists, pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, but ob.gyns. and family physicians only managed to keep their 2022 earnings at 2021 levels.

Overall physician compensation for 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The latest increase in earnings among internists also included a decline: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 24% in 2021 to 16% in 2022. The gap was slightly larger for all physicians in 2022, with men earning about 19% more than women, and larger again among specialists at 27%, but both of those figures are lower than in recent years, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, however, was not high for internists: Only 43% feel that they are fairly paid, coming in above only ophthalmology (42%) and infectious diseases (35%) and well below psychiatry (68%) at the top of the list, the Medscape data show. In the 2022 report, 49% of internists said that they had been fairly paid.

In another source of potential dissatisfaction, internist respondents reported spending an average of 17.9 hours each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) and well above anesthesiology, which was the lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said. A small bright spot comes in the form of a decline from the internists’ time of 18.7 hours per week in 2021.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of internist respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed internists to be the least likely of the 29 included specialties to follow the same path, with 61% (down from 63% in 2022) approving their initial selection, versus 97% for plastic surgeons, Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

States move to curb insurers’ prior authorization requirements as federal reforms lag

Amid growing criticism of health insurers’ onerous prior authorization practices, lawmakers in 30 states have introduced bills this year that aim to rein in insurer gatekeeping and improve patient care.

“This is something that goes on in every doctor’s office every day; the frustrations, the delays, and the use of office staff time are just unbelievable,” said Steven Orland, MD, a board-certified urologist and president of the Medical Society of New Jersey.

The bills, which cover private health plans and insurers that states regulate, may provide some relief for physicians as federal efforts to streamline prior authorization for some Medicare patients have lagged.

Last year, Congress failed to pass the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021, despite 326 co-sponsors. The bill would have compelled insurers covering Medicare Advantage enrollees to speed up prior authorizations, make the process more transparent, and remove obstacles such as requiring fax machine submissions.

Last month, however, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a final rule that will improve some aspects of prior authorizations in Medicare Advantage insurance plans and ensure that enrollees have the same access to necessary care as traditional Medicare enrollees.

The insurance industry has long defended prior authorization requirements and opposed legislation that would limit them.

America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association said in a 2019 letter to a congressional committee when the federal legislation was first introduced, “Prior authorizations enforce best practices and guidelines for care management and help physicians identify and avoid care techniques that would harm patient outcomes, such as designating prescriptions that could feed into an opioid addiction.” AHIP didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.

But some major insurers now appear willing to compromise and voluntarily reduce the volume of prior authorizations they require. Days before the federal final rule was released, three major insurers – United HealthCare, Cigna, and Aetna CVS Health – announced they plan to drop some prior authorization requirements and automate processes.

United HealthCare said it will eliminate almost 20% of its prior authorizations for some nonurgent surgeries and procedures starting this summer. It also will create a national Gold Card program in 2024 for physicians who meet its eligibility requirements, which would eliminate prior authorization requirements for most procedures. Both initiatives will apply to commercial, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid businesses, said the insurer in a statement.

However, United HealthCare also announced that in June it will start requiring prior authorization for diagnostic (not screening) gastrointestinal endoscopies for its nearly 27 million privately insured patients, citing data it says shows potentially harmful overuse of scopes. Physician groups have publicly criticized the move, saying it could delay lifesaving treatment, and have asked the insurer to reconsider.

Cigna and Aetna also have moved to pare back prior authorization processes. Scott Josephs, national medical officer for Cigna, told Healthcare Dive that Cigna has removed prior authorization reviews from nearly 500 services since 2020.

An Aetna spokesperson told Healthcare Dive that the CVS-owned payer has implemented a gold card program and rolled back prior authorization requirements on cataract surgeries, video EEGs, and home infusion for some drugs, according to Healthcare Dive.

Cigna has faced increased scrutiny from some state regulators since a ProPublica/The Capitol Forum article revealed in March that its doctors were denying claims without opening patients’ files, contrary to what insurance laws and regulations require in many states.

Over a period of 2 months last year, Cigna doctors denied over 300,000 requests for payments using this method, spending an average of 1.2 seconds on each case, the investigation found. In a written response, Cigna said the reporting by ProPublica and The Capitol Forum was “biased and incomplete.”

States aim to reduce prior authorization volume

The American Medical Association said it has been tracking nearly 90 prior authorization reform bills in 30 states. More than a dozen bills are still being considered in this legislative session, including in Arkansas, California, New Jersey, North Carolina, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

“The groundswell of activity in the states reflects how big a problem this is,” said an AMA legislative expert. “The issue used to be ‘how can we automate and streamline processes’; now the issue is focused on reducing the volume of prior authorizations and the harm that can cause patients.”

The state bills use different strategies to reduce excessive prior authorization requirements. Maryland’s proposed bill, for example, would require just one prior authorization to stay on a prescription drug, if the insurer has previously approved the drug and the patient continues to successfully be treated by the drug.

Washington, D.C. and New Jersey have introduced comprehensive reform bills that include a “grace period” of 60 days, to ensure continuity of care when a patient switches health plans. They also would eliminate repeat authorizations for chronic and long-term conditions, set explicit timelines for insurers to respond to prior authorization requests and appeals, and require that practicing physicians review denials that are appealed.

Many state bills also would require insurers to be more transparent by posting information on their websites about which services and drugs require prior authorization and what their approval rates are for them, said AMA’s legislative expert.

“There’s a black hole of information that insurers have access to. We would really like to know how many prior authorization requests are denied, the time it takes to deny them, and the reasons for denial,” said Josh Bengal, JD, the director of government relations for the Medical Society of New Jersey.

The legislation in New Jersey and other states faces stiff opposition from the insurance lobby, especially state associations of health plans affiliated with AHIP. The California Association of Health Plans, for example, opposes a “gold card” bill (SB 598), introduced in February, that would allow a select group of high-performing doctors to skip prior authorizations for 1 year.

The CAHP states, “Californians deserve safe, high quality, high-value health care. Yet SB 598 will derail the progress we have made in our health care system by lowering the value and safety that Californians should expect from their health care providers,” according to a fact sheet.

The fact-sheet defines “low-value care” as medical services for which there is little to no benefit and poses potential physical or financial harm to patients, such as unnecessary CT scans or MRIs for uncomplicated conditions.

California is one of about a dozen states that have introduced gold card legislation this year. If enacted, they would join five states with gold card laws: West Virginia, Texas, Vermont, Michigan, and Louisiana.

How do gold cards work?

Physicians who achieve a high approval rate of prior authorizations from insurers for 1 year are eligible to be exempted from obtaining prior authorizations the following year.

The approval rate is at least 90% for a certain number of eligible health services, but the number of prior authorizations required to qualify can range from 5 to 30, depending on the state law.

Gold card legislation typically also gives the treating physician the right to have an appeal of a prior authorization denial by a physician peer of the same or similar specialty.

California’s bill would also apply to all covered health services, which is broader than what United HealthCare has proposed for its gold card exemption. The bill would also require a plan or insurer to annually monitor rates of prior authorization approval, modification, appeal, and denial, and to discontinue services, items, and supplies that are approved 95% of the time.

“These are important reforms that will help ensure that patients can receive the care they need, when they need it,” said CMA president Donaldo Hernandez, MD.

However, it’s not clear how many physicians will meet “gold card” status based on Texas’ recent experience with its own “gold card” law.

The Texas Department of Insurance estimated that only 3.3% of licensed physicians in the state have met “gold card” status since the bill became law in 2021, said Zeke Silva, MD, an interventional radiologist who serves on the Council of Legislation for the Texas Medical Association.

He noted that the legislation has had a limited effect for several reasons. Commercial health plans only make up only about 20% of all health plans in Texas. Also, the final regulations didn’t go into effect until last May and physicians are evaluated by health plans for “gold card” status every 6 months, said Dr. Silva.

In addition, physicians must have at least five prior authorizations approved for the same health service, which the law left up to the health plans to define, said Dr. Silva.

Now, the Texas Medical Association is lobbying for legislative improvements. “We want to reduce the number of eligible services that health plans require for prior authorizations and have more oversight of prior authorization denials by the Texas Department of Insurance and the Texas Medical Board,” said Dr. Silva.

He’s optimistic that if the bill becomes law, the number of physicians eligible for gold cards may increase.

Meanwhile, the AMA’s legislative expert, who declined to be identified because of organization policy, acknowledged the possibility that some prior authorization bills will die in state legislatures this year.

“We remain hopeful, but it’s an uphill battle. The state medical associations face a lot of opposition from health plans who don’t want to see these reforms become law.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Amid growing criticism of health insurers’ onerous prior authorization practices, lawmakers in 30 states have introduced bills this year that aim to rein in insurer gatekeeping and improve patient care.

“This is something that goes on in every doctor’s office every day; the frustrations, the delays, and the use of office staff time are just unbelievable,” said Steven Orland, MD, a board-certified urologist and president of the Medical Society of New Jersey.

The bills, which cover private health plans and insurers that states regulate, may provide some relief for physicians as federal efforts to streamline prior authorization for some Medicare patients have lagged.

Last year, Congress failed to pass the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021, despite 326 co-sponsors. The bill would have compelled insurers covering Medicare Advantage enrollees to speed up prior authorizations, make the process more transparent, and remove obstacles such as requiring fax machine submissions.

Last month, however, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a final rule that will improve some aspects of prior authorizations in Medicare Advantage insurance plans and ensure that enrollees have the same access to necessary care as traditional Medicare enrollees.

The insurance industry has long defended prior authorization requirements and opposed legislation that would limit them.

America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association said in a 2019 letter to a congressional committee when the federal legislation was first introduced, “Prior authorizations enforce best practices and guidelines for care management and help physicians identify and avoid care techniques that would harm patient outcomes, such as designating prescriptions that could feed into an opioid addiction.” AHIP didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.

But some major insurers now appear willing to compromise and voluntarily reduce the volume of prior authorizations they require. Days before the federal final rule was released, three major insurers – United HealthCare, Cigna, and Aetna CVS Health – announced they plan to drop some prior authorization requirements and automate processes.

United HealthCare said it will eliminate almost 20% of its prior authorizations for some nonurgent surgeries and procedures starting this summer. It also will create a national Gold Card program in 2024 for physicians who meet its eligibility requirements, which would eliminate prior authorization requirements for most procedures. Both initiatives will apply to commercial, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid businesses, said the insurer in a statement.

However, United HealthCare also announced that in June it will start requiring prior authorization for diagnostic (not screening) gastrointestinal endoscopies for its nearly 27 million privately insured patients, citing data it says shows potentially harmful overuse of scopes. Physician groups have publicly criticized the move, saying it could delay lifesaving treatment, and have asked the insurer to reconsider.

Cigna and Aetna also have moved to pare back prior authorization processes. Scott Josephs, national medical officer for Cigna, told Healthcare Dive that Cigna has removed prior authorization reviews from nearly 500 services since 2020.

An Aetna spokesperson told Healthcare Dive that the CVS-owned payer has implemented a gold card program and rolled back prior authorization requirements on cataract surgeries, video EEGs, and home infusion for some drugs, according to Healthcare Dive.

Cigna has faced increased scrutiny from some state regulators since a ProPublica/The Capitol Forum article revealed in March that its doctors were denying claims without opening patients’ files, contrary to what insurance laws and regulations require in many states.

Over a period of 2 months last year, Cigna doctors denied over 300,000 requests for payments using this method, spending an average of 1.2 seconds on each case, the investigation found. In a written response, Cigna said the reporting by ProPublica and The Capitol Forum was “biased and incomplete.”

States aim to reduce prior authorization volume

The American Medical Association said it has been tracking nearly 90 prior authorization reform bills in 30 states. More than a dozen bills are still being considered in this legislative session, including in Arkansas, California, New Jersey, North Carolina, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

“The groundswell of activity in the states reflects how big a problem this is,” said an AMA legislative expert. “The issue used to be ‘how can we automate and streamline processes’; now the issue is focused on reducing the volume of prior authorizations and the harm that can cause patients.”

The state bills use different strategies to reduce excessive prior authorization requirements. Maryland’s proposed bill, for example, would require just one prior authorization to stay on a prescription drug, if the insurer has previously approved the drug and the patient continues to successfully be treated by the drug.

Washington, D.C. and New Jersey have introduced comprehensive reform bills that include a “grace period” of 60 days, to ensure continuity of care when a patient switches health plans. They also would eliminate repeat authorizations for chronic and long-term conditions, set explicit timelines for insurers to respond to prior authorization requests and appeals, and require that practicing physicians review denials that are appealed.

Many state bills also would require insurers to be more transparent by posting information on their websites about which services and drugs require prior authorization and what their approval rates are for them, said AMA’s legislative expert.

“There’s a black hole of information that insurers have access to. We would really like to know how many prior authorization requests are denied, the time it takes to deny them, and the reasons for denial,” said Josh Bengal, JD, the director of government relations for the Medical Society of New Jersey.

The legislation in New Jersey and other states faces stiff opposition from the insurance lobby, especially state associations of health plans affiliated with AHIP. The California Association of Health Plans, for example, opposes a “gold card” bill (SB 598), introduced in February, that would allow a select group of high-performing doctors to skip prior authorizations for 1 year.

The CAHP states, “Californians deserve safe, high quality, high-value health care. Yet SB 598 will derail the progress we have made in our health care system by lowering the value and safety that Californians should expect from their health care providers,” according to a fact sheet.

The fact-sheet defines “low-value care” as medical services for which there is little to no benefit and poses potential physical or financial harm to patients, such as unnecessary CT scans or MRIs for uncomplicated conditions.

California is one of about a dozen states that have introduced gold card legislation this year. If enacted, they would join five states with gold card laws: West Virginia, Texas, Vermont, Michigan, and Louisiana.

How do gold cards work?

Physicians who achieve a high approval rate of prior authorizations from insurers for 1 year are eligible to be exempted from obtaining prior authorizations the following year.

The approval rate is at least 90% for a certain number of eligible health services, but the number of prior authorizations required to qualify can range from 5 to 30, depending on the state law.

Gold card legislation typically also gives the treating physician the right to have an appeal of a prior authorization denial by a physician peer of the same or similar specialty.

California’s bill would also apply to all covered health services, which is broader than what United HealthCare has proposed for its gold card exemption. The bill would also require a plan or insurer to annually monitor rates of prior authorization approval, modification, appeal, and denial, and to discontinue services, items, and supplies that are approved 95% of the time.

“These are important reforms that will help ensure that patients can receive the care they need, when they need it,” said CMA president Donaldo Hernandez, MD.

However, it’s not clear how many physicians will meet “gold card” status based on Texas’ recent experience with its own “gold card” law.

The Texas Department of Insurance estimated that only 3.3% of licensed physicians in the state have met “gold card” status since the bill became law in 2021, said Zeke Silva, MD, an interventional radiologist who serves on the Council of Legislation for the Texas Medical Association.

He noted that the legislation has had a limited effect for several reasons. Commercial health plans only make up only about 20% of all health plans in Texas. Also, the final regulations didn’t go into effect until last May and physicians are evaluated by health plans for “gold card” status every 6 months, said Dr. Silva.

In addition, physicians must have at least five prior authorizations approved for the same health service, which the law left up to the health plans to define, said Dr. Silva.

Now, the Texas Medical Association is lobbying for legislative improvements. “We want to reduce the number of eligible services that health plans require for prior authorizations and have more oversight of prior authorization denials by the Texas Department of Insurance and the Texas Medical Board,” said Dr. Silva.

He’s optimistic that if the bill becomes law, the number of physicians eligible for gold cards may increase.

Meanwhile, the AMA’s legislative expert, who declined to be identified because of organization policy, acknowledged the possibility that some prior authorization bills will die in state legislatures this year.

“We remain hopeful, but it’s an uphill battle. The state medical associations face a lot of opposition from health plans who don’t want to see these reforms become law.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Amid growing criticism of health insurers’ onerous prior authorization practices, lawmakers in 30 states have introduced bills this year that aim to rein in insurer gatekeeping and improve patient care.

“This is something that goes on in every doctor’s office every day; the frustrations, the delays, and the use of office staff time are just unbelievable,” said Steven Orland, MD, a board-certified urologist and president of the Medical Society of New Jersey.

The bills, which cover private health plans and insurers that states regulate, may provide some relief for physicians as federal efforts to streamline prior authorization for some Medicare patients have lagged.

Last year, Congress failed to pass the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021, despite 326 co-sponsors. The bill would have compelled insurers covering Medicare Advantage enrollees to speed up prior authorizations, make the process more transparent, and remove obstacles such as requiring fax machine submissions.

Last month, however, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a final rule that will improve some aspects of prior authorizations in Medicare Advantage insurance plans and ensure that enrollees have the same access to necessary care as traditional Medicare enrollees.

The insurance industry has long defended prior authorization requirements and opposed legislation that would limit them.

America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association said in a 2019 letter to a congressional committee when the federal legislation was first introduced, “Prior authorizations enforce best practices and guidelines for care management and help physicians identify and avoid care techniques that would harm patient outcomes, such as designating prescriptions that could feed into an opioid addiction.” AHIP didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.

But some major insurers now appear willing to compromise and voluntarily reduce the volume of prior authorizations they require. Days before the federal final rule was released, three major insurers – United HealthCare, Cigna, and Aetna CVS Health – announced they plan to drop some prior authorization requirements and automate processes.

United HealthCare said it will eliminate almost 20% of its prior authorizations for some nonurgent surgeries and procedures starting this summer. It also will create a national Gold Card program in 2024 for physicians who meet its eligibility requirements, which would eliminate prior authorization requirements for most procedures. Both initiatives will apply to commercial, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid businesses, said the insurer in a statement.

However, United HealthCare also announced that in June it will start requiring prior authorization for diagnostic (not screening) gastrointestinal endoscopies for its nearly 27 million privately insured patients, citing data it says shows potentially harmful overuse of scopes. Physician groups have publicly criticized the move, saying it could delay lifesaving treatment, and have asked the insurer to reconsider.

Cigna and Aetna also have moved to pare back prior authorization processes. Scott Josephs, national medical officer for Cigna, told Healthcare Dive that Cigna has removed prior authorization reviews from nearly 500 services since 2020.

An Aetna spokesperson told Healthcare Dive that the CVS-owned payer has implemented a gold card program and rolled back prior authorization requirements on cataract surgeries, video EEGs, and home infusion for some drugs, according to Healthcare Dive.

Cigna has faced increased scrutiny from some state regulators since a ProPublica/The Capitol Forum article revealed in March that its doctors were denying claims without opening patients’ files, contrary to what insurance laws and regulations require in many states.

Over a period of 2 months last year, Cigna doctors denied over 300,000 requests for payments using this method, spending an average of 1.2 seconds on each case, the investigation found. In a written response, Cigna said the reporting by ProPublica and The Capitol Forum was “biased and incomplete.”

States aim to reduce prior authorization volume

The American Medical Association said it has been tracking nearly 90 prior authorization reform bills in 30 states. More than a dozen bills are still being considered in this legislative session, including in Arkansas, California, New Jersey, North Carolina, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

“The groundswell of activity in the states reflects how big a problem this is,” said an AMA legislative expert. “The issue used to be ‘how can we automate and streamline processes’; now the issue is focused on reducing the volume of prior authorizations and the harm that can cause patients.”

The state bills use different strategies to reduce excessive prior authorization requirements. Maryland’s proposed bill, for example, would require just one prior authorization to stay on a prescription drug, if the insurer has previously approved the drug and the patient continues to successfully be treated by the drug.

Washington, D.C. and New Jersey have introduced comprehensive reform bills that include a “grace period” of 60 days, to ensure continuity of care when a patient switches health plans. They also would eliminate repeat authorizations for chronic and long-term conditions, set explicit timelines for insurers to respond to prior authorization requests and appeals, and require that practicing physicians review denials that are appealed.

Many state bills also would require insurers to be more transparent by posting information on their websites about which services and drugs require prior authorization and what their approval rates are for them, said AMA’s legislative expert.

“There’s a black hole of information that insurers have access to. We would really like to know how many prior authorization requests are denied, the time it takes to deny them, and the reasons for denial,” said Josh Bengal, JD, the director of government relations for the Medical Society of New Jersey.

The legislation in New Jersey and other states faces stiff opposition from the insurance lobby, especially state associations of health plans affiliated with AHIP. The California Association of Health Plans, for example, opposes a “gold card” bill (SB 598), introduced in February, that would allow a select group of high-performing doctors to skip prior authorizations for 1 year.

The CAHP states, “Californians deserve safe, high quality, high-value health care. Yet SB 598 will derail the progress we have made in our health care system by lowering the value and safety that Californians should expect from their health care providers,” according to a fact sheet.

The fact-sheet defines “low-value care” as medical services for which there is little to no benefit and poses potential physical or financial harm to patients, such as unnecessary CT scans or MRIs for uncomplicated conditions.

California is one of about a dozen states that have introduced gold card legislation this year. If enacted, they would join five states with gold card laws: West Virginia, Texas, Vermont, Michigan, and Louisiana.

How do gold cards work?

Physicians who achieve a high approval rate of prior authorizations from insurers for 1 year are eligible to be exempted from obtaining prior authorizations the following year.

The approval rate is at least 90% for a certain number of eligible health services, but the number of prior authorizations required to qualify can range from 5 to 30, depending on the state law.

Gold card legislation typically also gives the treating physician the right to have an appeal of a prior authorization denial by a physician peer of the same or similar specialty.

California’s bill would also apply to all covered health services, which is broader than what United HealthCare has proposed for its gold card exemption. The bill would also require a plan or insurer to annually monitor rates of prior authorization approval, modification, appeal, and denial, and to discontinue services, items, and supplies that are approved 95% of the time.

“These are important reforms that will help ensure that patients can receive the care they need, when they need it,” said CMA president Donaldo Hernandez, MD.

However, it’s not clear how many physicians will meet “gold card” status based on Texas’ recent experience with its own “gold card” law.

The Texas Department of Insurance estimated that only 3.3% of licensed physicians in the state have met “gold card” status since the bill became law in 2021, said Zeke Silva, MD, an interventional radiologist who serves on the Council of Legislation for the Texas Medical Association.

He noted that the legislation has had a limited effect for several reasons. Commercial health plans only make up only about 20% of all health plans in Texas. Also, the final regulations didn’t go into effect until last May and physicians are evaluated by health plans for “gold card” status every 6 months, said Dr. Silva.

In addition, physicians must have at least five prior authorizations approved for the same health service, which the law left up to the health plans to define, said Dr. Silva.

Now, the Texas Medical Association is lobbying for legislative improvements. “We want to reduce the number of eligible services that health plans require for prior authorizations and have more oversight of prior authorization denials by the Texas Department of Insurance and the Texas Medical Board,” said Dr. Silva.

He’s optimistic that if the bill becomes law, the number of physicians eligible for gold cards may increase.

Meanwhile, the AMA’s legislative expert, who declined to be identified because of organization policy, acknowledged the possibility that some prior authorization bills will die in state legislatures this year.

“We remain hopeful, but it’s an uphill battle. The state medical associations face a lot of opposition from health plans who don’t want to see these reforms become law.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ChatGPT bot flunks gastroenterology exam

Versions 3 and 4 of the chatbot scored only 65% and 62%, respectively, on the American College of Gastroenterology Self-Assessment Test. The minimum passing grade is 70%.

“You might expect a physician to score 99%, or at least 95%,” lead author Arvind J. Trindade, MD, regional director of endoscopy at Northwell Health (Central Region) in New Hyde Park, New York, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Dr. Trindade and colleagues undertook the study amid growing reports of students using the tool across many academic areas, including law and medicine, and growing interest in the chatbot’s potential in medical education.

“I saw gastroenterology students typing questions into it. I wanted to know how accurate it was in gastroenterology – if it was going to be used in medical education and patient care,” said Dr. Trindade, who is also an associate professor at Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York. “Based on our research, ChatGPT should not be used for medical education in gastroenterology at this time, and it has a way to go before it should be implemented into the health care field.”

Poor showing

The researchers tested the two versions of ChatGPT on both the 2021 and 2022 online ACG Self-Assessment Test, a multiple-choice exam designed to gauge how well a trainee would do on the American Board of Internal Medicine Gastroenterology board examination.

Questions that involved image selection were excluded from the study. For those that remained, the questions and answer choices were copied and pasted directly into ChatGPT, which returned answers and explanations. The corresponding answer was selected on the ACG website based on the chatbot’s response.

Of the 455 questions posed, ChatGPT-3 correctly answered 296, and ChatGPT-4 got 284 right. There was no discernible pattern in the type of question that the chatbot answered incorrectly, but questions on surveillance timing for various disease states, diagnosis, and pharmaceutical regimens were all answered incorrectly.

The reasons for the tool’s poor performance could lie with the large language model underpinning ChatGPT, the researchers write. The model was trained on freely available information – not specifically on medical literature and not on materials that require paid journal subscriptions – to be a general-purpose interactive program.

Additionally, the chatbot may use information from a variety of sources, including non- or quasi-medical sources, or out-of-date sources, which can lead to errors, they note. ChatGPT-3 was last updated in June 2021 and ChatGPT-4 in September 2021.

“ChatGPT does not have an intrinsic understanding of an issue,” Dr. Trindade said. “Its basic function is to predict the next word in a string of text to produce an expected response, regardless of whether such a response is factually correct or not.”

Previous research

In a previous study, ChatGPT was able to pass parts of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination.

The chatbot may have performed better on the USMLE because the information tested on the exam may have been more widely available for ChatGPT’s language training, Dr. Trindade said. “In addition, the threshold for passing [the USMLE] is lower with regard to the percentage of questions correctly answered,” he said.

ChatGPT seems to fare better at helping to inform patients than it does on medical exams. The chatbot provided generally satisfactory answers to common patient queries about colonoscopy in one study and about hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in another study.

For ChatGPT to be valuable in medical education, “future versions would need to be updated with medical resources such as journal articles, society guidelines, and medical databases, such as UpToDate,” Dr. Trindade said. “With directed medical training in gastroenterology, it may be a future tool for education or patient use in this field, but not currently as it is now. Before it can be used in gastroenterology, it should be validated.”

That said, he noted, medical education has evolved from being based on textbooks and print journals to include Internet-based journal data and practice guidelines on specialty websites. If properly primed, resources such as ChatGPT may be the next logical step.

This study received no funding. Dr. Trindade is a consultant for Pentax Medical, Boston Scientific, Lucid Diagnostic, and Exact Science and receives research support from Lucid Diagnostics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Versions 3 and 4 of the chatbot scored only 65% and 62%, respectively, on the American College of Gastroenterology Self-Assessment Test. The minimum passing grade is 70%.

“You might expect a physician to score 99%, or at least 95%,” lead author Arvind J. Trindade, MD, regional director of endoscopy at Northwell Health (Central Region) in New Hyde Park, New York, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Dr. Trindade and colleagues undertook the study amid growing reports of students using the tool across many academic areas, including law and medicine, and growing interest in the chatbot’s potential in medical education.

“I saw gastroenterology students typing questions into it. I wanted to know how accurate it was in gastroenterology – if it was going to be used in medical education and patient care,” said Dr. Trindade, who is also an associate professor at Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York. “Based on our research, ChatGPT should not be used for medical education in gastroenterology at this time, and it has a way to go before it should be implemented into the health care field.”

Poor showing

The researchers tested the two versions of ChatGPT on both the 2021 and 2022 online ACG Self-Assessment Test, a multiple-choice exam designed to gauge how well a trainee would do on the American Board of Internal Medicine Gastroenterology board examination.

Questions that involved image selection were excluded from the study. For those that remained, the questions and answer choices were copied and pasted directly into ChatGPT, which returned answers and explanations. The corresponding answer was selected on the ACG website based on the chatbot’s response.

Of the 455 questions posed, ChatGPT-3 correctly answered 296, and ChatGPT-4 got 284 right. There was no discernible pattern in the type of question that the chatbot answered incorrectly, but questions on surveillance timing for various disease states, diagnosis, and pharmaceutical regimens were all answered incorrectly.

The reasons for the tool’s poor performance could lie with the large language model underpinning ChatGPT, the researchers write. The model was trained on freely available information – not specifically on medical literature and not on materials that require paid journal subscriptions – to be a general-purpose interactive program.

Additionally, the chatbot may use information from a variety of sources, including non- or quasi-medical sources, or out-of-date sources, which can lead to errors, they note. ChatGPT-3 was last updated in June 2021 and ChatGPT-4 in September 2021.

“ChatGPT does not have an intrinsic understanding of an issue,” Dr. Trindade said. “Its basic function is to predict the next word in a string of text to produce an expected response, regardless of whether such a response is factually correct or not.”

Previous research

In a previous study, ChatGPT was able to pass parts of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination.

The chatbot may have performed better on the USMLE because the information tested on the exam may have been more widely available for ChatGPT’s language training, Dr. Trindade said. “In addition, the threshold for passing [the USMLE] is lower with regard to the percentage of questions correctly answered,” he said.

ChatGPT seems to fare better at helping to inform patients than it does on medical exams. The chatbot provided generally satisfactory answers to common patient queries about colonoscopy in one study and about hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in another study.

For ChatGPT to be valuable in medical education, “future versions would need to be updated with medical resources such as journal articles, society guidelines, and medical databases, such as UpToDate,” Dr. Trindade said. “With directed medical training in gastroenterology, it may be a future tool for education or patient use in this field, but not currently as it is now. Before it can be used in gastroenterology, it should be validated.”

That said, he noted, medical education has evolved from being based on textbooks and print journals to include Internet-based journal data and practice guidelines on specialty websites. If properly primed, resources such as ChatGPT may be the next logical step.

This study received no funding. Dr. Trindade is a consultant for Pentax Medical, Boston Scientific, Lucid Diagnostic, and Exact Science and receives research support from Lucid Diagnostics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Versions 3 and 4 of the chatbot scored only 65% and 62%, respectively, on the American College of Gastroenterology Self-Assessment Test. The minimum passing grade is 70%.

“You might expect a physician to score 99%, or at least 95%,” lead author Arvind J. Trindade, MD, regional director of endoscopy at Northwell Health (Central Region) in New Hyde Park, New York, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Dr. Trindade and colleagues undertook the study amid growing reports of students using the tool across many academic areas, including law and medicine, and growing interest in the chatbot’s potential in medical education.

“I saw gastroenterology students typing questions into it. I wanted to know how accurate it was in gastroenterology – if it was going to be used in medical education and patient care,” said Dr. Trindade, who is also an associate professor at Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York. “Based on our research, ChatGPT should not be used for medical education in gastroenterology at this time, and it has a way to go before it should be implemented into the health care field.”

Poor showing

The researchers tested the two versions of ChatGPT on both the 2021 and 2022 online ACG Self-Assessment Test, a multiple-choice exam designed to gauge how well a trainee would do on the American Board of Internal Medicine Gastroenterology board examination.

Questions that involved image selection were excluded from the study. For those that remained, the questions and answer choices were copied and pasted directly into ChatGPT, which returned answers and explanations. The corresponding answer was selected on the ACG website based on the chatbot’s response.

Of the 455 questions posed, ChatGPT-3 correctly answered 296, and ChatGPT-4 got 284 right. There was no discernible pattern in the type of question that the chatbot answered incorrectly, but questions on surveillance timing for various disease states, diagnosis, and pharmaceutical regimens were all answered incorrectly.

The reasons for the tool’s poor performance could lie with the large language model underpinning ChatGPT, the researchers write. The model was trained on freely available information – not specifically on medical literature and not on materials that require paid journal subscriptions – to be a general-purpose interactive program.

Additionally, the chatbot may use information from a variety of sources, including non- or quasi-medical sources, or out-of-date sources, which can lead to errors, they note. ChatGPT-3 was last updated in June 2021 and ChatGPT-4 in September 2021.

“ChatGPT does not have an intrinsic understanding of an issue,” Dr. Trindade said. “Its basic function is to predict the next word in a string of text to produce an expected response, regardless of whether such a response is factually correct or not.”

Previous research

In a previous study, ChatGPT was able to pass parts of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination.

The chatbot may have performed better on the USMLE because the information tested on the exam may have been more widely available for ChatGPT’s language training, Dr. Trindade said. “In addition, the threshold for passing [the USMLE] is lower with regard to the percentage of questions correctly answered,” he said.

ChatGPT seems to fare better at helping to inform patients than it does on medical exams. The chatbot provided generally satisfactory answers to common patient queries about colonoscopy in one study and about hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in another study.

For ChatGPT to be valuable in medical education, “future versions would need to be updated with medical resources such as journal articles, society guidelines, and medical databases, such as UpToDate,” Dr. Trindade said. “With directed medical training in gastroenterology, it may be a future tool for education or patient use in this field, but not currently as it is now. Before it can be used in gastroenterology, it should be validated.”

That said, he noted, medical education has evolved from being based on textbooks and print journals to include Internet-based journal data and practice guidelines on specialty websites. If properly primed, resources such as ChatGPT may be the next logical step.

This study received no funding. Dr. Trindade is a consultant for Pentax Medical, Boston Scientific, Lucid Diagnostic, and Exact Science and receives research support from Lucid Diagnostics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Maternal health clinic teams with legal services to aid patients

BALTIMORE – A novel partnership between a legal services program and a maternal health clinic is helping pregnant patients with issues such as housing or employment discrimination.

The Perinatal Legal Assistance and Well-being (P-LAW) program at Georgetown University, Washington, launched 2 years ago as a collaboration between GU’s Health Justice Alliance clinic and the Women’s and Infants Services division of nearby MedStar Washington Hospital Center, integrating attorneys into the health care team to offer no-cost legal aid for its diverse, urban population during the perinatal period. Since then, the effort has assisted more than 120 women.

“Our goal was to see how integrating a lawyer can help address some of those issues that, unfortunately, providers are not able to assist with because they go beyond the hospital or clinic walls,” said Roxana Richardson, JD, the project director and managing attorney for P-LAW, during a poster presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Our initial findings showed that there are issues that patients were facing that needed an intervention from an attorney. We trained the providers and social workers to identify these issues so that we could intervene.”

Improving health by tackling legal barriers

, Ms. Richardson said.

The program is one of few medical-legal partnerships specifically focused on the perinatal population. P-LAW is one component of a larger initiative at MedStar Health called DC Safe Babies Safe Moms. The initiative includes integrated mental health programming, treatment of health conditions that complicate pregnancy, assessments of social determinants of health, expanded support for lactation and nutrition, access to home visiting referrals, and extended postpartum follow-up. The work is supported through the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation.

Patients are evaluated for health-harming legal needs as part of a comprehensive social and behavioral health screening at their initial prenatal visit, 28-week appointment, and postpartum visit. Those who screen positive are contacted by a referral specialist on the health care team who confirms the patient has an active legal need and would like to be connected to the P-LAW team. The team then reaches out to conduct a legal intake and determine the appropriate course of action.

From March 2021 through February of this year, Ms. Richardson and others with the program have provided legal representation to 123 patients on 186 legal issues in areas such as public benefits, employment, and housing and family concerns. Services range from advising patients on steps they can take on their own (like reporting a housing condition issue to the Department of Buildings), to sending letters on patients’ behalf, to appearing in court. Most patients served were in their second and third trimesters of pregnancy. The majority were Black or African American, aged 20-34 years, and had incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level.

The most common legal issues were in the areas of public benefits (SNAP/food stamps, cash assistance), employment (parental leave, discrimination), housing (conditions, eviction), and family law (child support, domestic violence). Among the 186 issues, work has been completed on 106 concerns and 33 still have a case open; for 47, the client withdrew or ceased contact, Ms. Richardson reported.

Most times when obstetricians hear concerns like these, they wonder what to do, said Tamika Auguste, MD, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at MedStar Health. Having the P-LAW program as a resource is a huge help, she said. If patients express concerns, or if obstetricians uncover concerns during office visits, doctors can enter a referral directly in the electronic medical record.

Patients are “so relieved,” Dr. Auguste said in an interview, because they often wonder if their doctor can help. “Your doctor is only going to be able to help to a certain point. But to know they’re pregnant and they have this resource, and they’re going to get legal help, has been game-changing for so many patients.”

COVID ... or morning sickness?

In one rewarding case, Ms. Richardson said, a single mother of one child who was pregnant and experiencing hyperemesis explained that her employer would forbid her from working if she had any symptoms similar to COVID-19. The employer mistook her vomiting, nausea, and exhaustion as COVID symptoms and docked her pay. That started a cascade in which earning less meant she was facing eviction and car repossession – and, eventually, overdraft fees and withdrawals from her bank. She was so despondent she was thinking about self-harm, Ms. Richardson said.

With the aid of the P-LAW program, the woman had short-term disability approved within 72 hours, was referred to the hospital for inpatient mental health treatment, and received the care she needed. She ultimately delivered a healthy baby girl and found a new job.

Tiffany Moore Simas, MD, MPH, MEd, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Massachusetts and UMass Memorial Health in Worcester, said she encounters similar concerns among her patients, with the vast majority having one or more issues with social determinants of health.

“I think it’s incredible, as we’re trying to address equity in perinatal health and maternal mortality and morbidity, to have a more holistic view of what health means, and all of the social determinants of health, and actually helping our patients address that in real time at their visits and connecting them,” said Dr. Simas, who also is professor of ob/gyn, pediatrics, psychiatry, and population and quantitative health sciences at UMass. “It has really opened my mind to the possibilities of things we need to explore and do differently.”

Ms. Richardson, Dr. Auguste, and Dr. Simas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

BALTIMORE – A novel partnership between a legal services program and a maternal health clinic is helping pregnant patients with issues such as housing or employment discrimination.

The Perinatal Legal Assistance and Well-being (P-LAW) program at Georgetown University, Washington, launched 2 years ago as a collaboration between GU’s Health Justice Alliance clinic and the Women’s and Infants Services division of nearby MedStar Washington Hospital Center, integrating attorneys into the health care team to offer no-cost legal aid for its diverse, urban population during the perinatal period. Since then, the effort has assisted more than 120 women.

“Our goal was to see how integrating a lawyer can help address some of those issues that, unfortunately, providers are not able to assist with because they go beyond the hospital or clinic walls,” said Roxana Richardson, JD, the project director and managing attorney for P-LAW, during a poster presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Our initial findings showed that there are issues that patients were facing that needed an intervention from an attorney. We trained the providers and social workers to identify these issues so that we could intervene.”

Improving health by tackling legal barriers

, Ms. Richardson said.

The program is one of few medical-legal partnerships specifically focused on the perinatal population. P-LAW is one component of a larger initiative at MedStar Health called DC Safe Babies Safe Moms. The initiative includes integrated mental health programming, treatment of health conditions that complicate pregnancy, assessments of social determinants of health, expanded support for lactation and nutrition, access to home visiting referrals, and extended postpartum follow-up. The work is supported through the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation.

Patients are evaluated for health-harming legal needs as part of a comprehensive social and behavioral health screening at their initial prenatal visit, 28-week appointment, and postpartum visit. Those who screen positive are contacted by a referral specialist on the health care team who confirms the patient has an active legal need and would like to be connected to the P-LAW team. The team then reaches out to conduct a legal intake and determine the appropriate course of action.

From March 2021 through February of this year, Ms. Richardson and others with the program have provided legal representation to 123 patients on 186 legal issues in areas such as public benefits, employment, and housing and family concerns. Services range from advising patients on steps they can take on their own (like reporting a housing condition issue to the Department of Buildings), to sending letters on patients’ behalf, to appearing in court. Most patients served were in their second and third trimesters of pregnancy. The majority were Black or African American, aged 20-34 years, and had incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level.

The most common legal issues were in the areas of public benefits (SNAP/food stamps, cash assistance), employment (parental leave, discrimination), housing (conditions, eviction), and family law (child support, domestic violence). Among the 186 issues, work has been completed on 106 concerns and 33 still have a case open; for 47, the client withdrew or ceased contact, Ms. Richardson reported.

Most times when obstetricians hear concerns like these, they wonder what to do, said Tamika Auguste, MD, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at MedStar Health. Having the P-LAW program as a resource is a huge help, she said. If patients express concerns, or if obstetricians uncover concerns during office visits, doctors can enter a referral directly in the electronic medical record.

Patients are “so relieved,” Dr. Auguste said in an interview, because they often wonder if their doctor can help. “Your doctor is only going to be able to help to a certain point. But to know they’re pregnant and they have this resource, and they’re going to get legal help, has been game-changing for so many patients.”

COVID ... or morning sickness?

In one rewarding case, Ms. Richardson said, a single mother of one child who was pregnant and experiencing hyperemesis explained that her employer would forbid her from working if she had any symptoms similar to COVID-19. The employer mistook her vomiting, nausea, and exhaustion as COVID symptoms and docked her pay. That started a cascade in which earning less meant she was facing eviction and car repossession – and, eventually, overdraft fees and withdrawals from her bank. She was so despondent she was thinking about self-harm, Ms. Richardson said.

With the aid of the P-LAW program, the woman had short-term disability approved within 72 hours, was referred to the hospital for inpatient mental health treatment, and received the care she needed. She ultimately delivered a healthy baby girl and found a new job.

Tiffany Moore Simas, MD, MPH, MEd, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Massachusetts and UMass Memorial Health in Worcester, said she encounters similar concerns among her patients, with the vast majority having one or more issues with social determinants of health.

“I think it’s incredible, as we’re trying to address equity in perinatal health and maternal mortality and morbidity, to have a more holistic view of what health means, and all of the social determinants of health, and actually helping our patients address that in real time at their visits and connecting them,” said Dr. Simas, who also is professor of ob/gyn, pediatrics, psychiatry, and population and quantitative health sciences at UMass. “It has really opened my mind to the possibilities of things we need to explore and do differently.”

Ms. Richardson, Dr. Auguste, and Dr. Simas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

BALTIMORE – A novel partnership between a legal services program and a maternal health clinic is helping pregnant patients with issues such as housing or employment discrimination.

The Perinatal Legal Assistance and Well-being (P-LAW) program at Georgetown University, Washington, launched 2 years ago as a collaboration between GU’s Health Justice Alliance clinic and the Women’s and Infants Services division of nearby MedStar Washington Hospital Center, integrating attorneys into the health care team to offer no-cost legal aid for its diverse, urban population during the perinatal period. Since then, the effort has assisted more than 120 women.

“Our goal was to see how integrating a lawyer can help address some of those issues that, unfortunately, providers are not able to assist with because they go beyond the hospital or clinic walls,” said Roxana Richardson, JD, the project director and managing attorney for P-LAW, during a poster presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Our initial findings showed that there are issues that patients were facing that needed an intervention from an attorney. We trained the providers and social workers to identify these issues so that we could intervene.”

Improving health by tackling legal barriers

, Ms. Richardson said.

The program is one of few medical-legal partnerships specifically focused on the perinatal population. P-LAW is one component of a larger initiative at MedStar Health called DC Safe Babies Safe Moms. The initiative includes integrated mental health programming, treatment of health conditions that complicate pregnancy, assessments of social determinants of health, expanded support for lactation and nutrition, access to home visiting referrals, and extended postpartum follow-up. The work is supported through the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation.

Patients are evaluated for health-harming legal needs as part of a comprehensive social and behavioral health screening at their initial prenatal visit, 28-week appointment, and postpartum visit. Those who screen positive are contacted by a referral specialist on the health care team who confirms the patient has an active legal need and would like to be connected to the P-LAW team. The team then reaches out to conduct a legal intake and determine the appropriate course of action.

From March 2021 through February of this year, Ms. Richardson and others with the program have provided legal representation to 123 patients on 186 legal issues in areas such as public benefits, employment, and housing and family concerns. Services range from advising patients on steps they can take on their own (like reporting a housing condition issue to the Department of Buildings), to sending letters on patients’ behalf, to appearing in court. Most patients served were in their second and third trimesters of pregnancy. The majority were Black or African American, aged 20-34 years, and had incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level.

The most common legal issues were in the areas of public benefits (SNAP/food stamps, cash assistance), employment (parental leave, discrimination), housing (conditions, eviction), and family law (child support, domestic violence). Among the 186 issues, work has been completed on 106 concerns and 33 still have a case open; for 47, the client withdrew or ceased contact, Ms. Richardson reported.