User login

Even mild preop sepsis boosts postop thrombosis risk

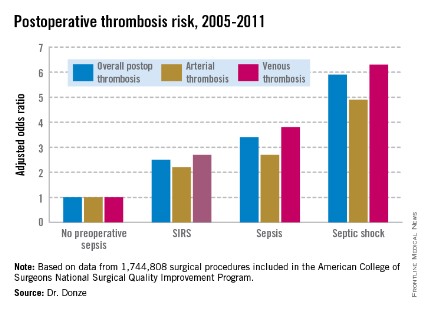

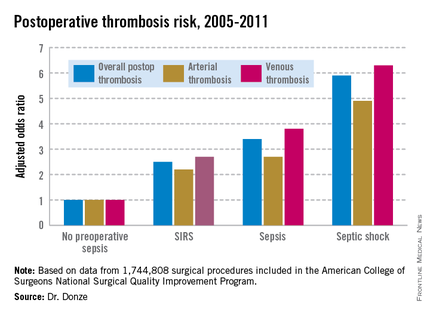

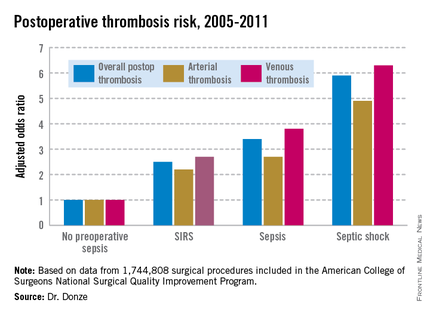

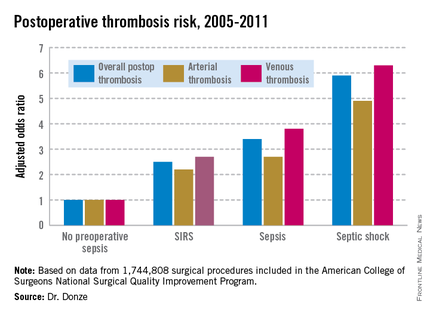

WASHINGTON – Preoperative sepsis proved to be an important independent risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis during or after surgery in an analysis of nearly 1.75 million U.S. surgical procedures.

The take-home message here is that the risk-benefit assessment of surgical procedures should take into account the presence of sepsis. And if the surgery can’t be delayed, prophylaxis against arterial as well as venous thrombosis should be employed, Dr. Jacques Donze said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Another key finding in this study was that the risk of postoperative thrombosis varied according to the severity of preoperative sepsis. Even the early form of sepsis known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk.

"Include even early signs of sepsis as a risk factor," urged Dr. Donze of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Also, preoperative sepsis was a risk factor for postoperative thrombosis in connection with outpatient elective surgery as well as inpatient operations, he added.

Dr. Donze presented an analysis of 1,744,808 surgical procedures performed during 2005-2011 at 314 U.S. hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. This large, prospective, observational registry is known for its high-quality data.

Within 48 hours prior to surgery, 7.8% of patients – totaling more than 136,000 – had SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock. Their postoperative thrombosis rate was 4.2%, compared with a 1.2% rate in patients without sepsis. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors, the postoperative thrombosis risk climbed with increasing severity of preoperative sepsis.

SIRS was defined on the basis of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count, and/or the presence of anion gap acidosis. "Sepsis" was defined as SIRS plus infection. And septic shock required the presence of sepsis plus documented organ dysfunction, such as hypotension.

The importance of recognizing this newly spotlighted sepsis/postoperative thrombosis connection is that most of the other known risk factors for thrombosis in surgical patients, including age, cancer, renal failure, and immobilization, are nonmodifiable, Dr. Donze observed.

Among the factors known to contribute to thrombosis are a hypercoagulable state, a proinflammatory state, hypoxemia, hypotension, and endothelial dysfunction. "All of these factors can be triggered by sepsis," Dr. Donze noted.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

WASHINGTON – Preoperative sepsis proved to be an important independent risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis during or after surgery in an analysis of nearly 1.75 million U.S. surgical procedures.

The take-home message here is that the risk-benefit assessment of surgical procedures should take into account the presence of sepsis. And if the surgery can’t be delayed, prophylaxis against arterial as well as venous thrombosis should be employed, Dr. Jacques Donze said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Another key finding in this study was that the risk of postoperative thrombosis varied according to the severity of preoperative sepsis. Even the early form of sepsis known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk.

"Include even early signs of sepsis as a risk factor," urged Dr. Donze of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Also, preoperative sepsis was a risk factor for postoperative thrombosis in connection with outpatient elective surgery as well as inpatient operations, he added.

Dr. Donze presented an analysis of 1,744,808 surgical procedures performed during 2005-2011 at 314 U.S. hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. This large, prospective, observational registry is known for its high-quality data.

Within 48 hours prior to surgery, 7.8% of patients – totaling more than 136,000 – had SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock. Their postoperative thrombosis rate was 4.2%, compared with a 1.2% rate in patients without sepsis. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors, the postoperative thrombosis risk climbed with increasing severity of preoperative sepsis.

SIRS was defined on the basis of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count, and/or the presence of anion gap acidosis. "Sepsis" was defined as SIRS plus infection. And septic shock required the presence of sepsis plus documented organ dysfunction, such as hypotension.

The importance of recognizing this newly spotlighted sepsis/postoperative thrombosis connection is that most of the other known risk factors for thrombosis in surgical patients, including age, cancer, renal failure, and immobilization, are nonmodifiable, Dr. Donze observed.

Among the factors known to contribute to thrombosis are a hypercoagulable state, a proinflammatory state, hypoxemia, hypotension, and endothelial dysfunction. "All of these factors can be triggered by sepsis," Dr. Donze noted.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

WASHINGTON – Preoperative sepsis proved to be an important independent risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis during or after surgery in an analysis of nearly 1.75 million U.S. surgical procedures.

The take-home message here is that the risk-benefit assessment of surgical procedures should take into account the presence of sepsis. And if the surgery can’t be delayed, prophylaxis against arterial as well as venous thrombosis should be employed, Dr. Jacques Donze said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Another key finding in this study was that the risk of postoperative thrombosis varied according to the severity of preoperative sepsis. Even the early form of sepsis known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk.

"Include even early signs of sepsis as a risk factor," urged Dr. Donze of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Also, preoperative sepsis was a risk factor for postoperative thrombosis in connection with outpatient elective surgery as well as inpatient operations, he added.

Dr. Donze presented an analysis of 1,744,808 surgical procedures performed during 2005-2011 at 314 U.S. hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. This large, prospective, observational registry is known for its high-quality data.

Within 48 hours prior to surgery, 7.8% of patients – totaling more than 136,000 – had SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock. Their postoperative thrombosis rate was 4.2%, compared with a 1.2% rate in patients without sepsis. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors, the postoperative thrombosis risk climbed with increasing severity of preoperative sepsis.

SIRS was defined on the basis of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count, and/or the presence of anion gap acidosis. "Sepsis" was defined as SIRS plus infection. And septic shock required the presence of sepsis plus documented organ dysfunction, such as hypotension.

The importance of recognizing this newly spotlighted sepsis/postoperative thrombosis connection is that most of the other known risk factors for thrombosis in surgical patients, including age, cancer, renal failure, and immobilization, are nonmodifiable, Dr. Donze observed.

Among the factors known to contribute to thrombosis are a hypercoagulable state, a proinflammatory state, hypoxemia, hypotension, and endothelial dysfunction. "All of these factors can be triggered by sepsis," Dr. Donze noted.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

AT ACC 14

Major finding: Preoperative sepsis is a strong independent risk factor for postoperative arterial and venous thrombosis; the more severe the sepsis, the greater the thrombosis risk.

Data source: This was an analysis of nearly 1.75 million surgical procedures at 314 U.S. hospitals detailed in the American College of Surgeons National Quality Improvement Program registry.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE prophylaxis mantra

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Hold the ACE inhibitors during surgery?

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – When it comes to holding or continuing with ACE inhibitors before surgery, all bets are off, a perioperative medicine consultant suggested.

Patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) have about a 50% risk of developing hypotension during surgery, and a significant proportion of those episodes could be severe, said Dr. Paul Grant, of the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

"I recommend having some sort of standard approach [to perioperative ACE inhibitor use] at your institution if that’s at all possible, either for a certain surgery type or across the board," he said at a meeting on perioperative medicine sponsored by the University of Miami.

Evidence from a small number of randomized trials and observational studies suggests that continuing ACE inhibitors during cardiac surgery may result in less cardiac enzyme release, less kidney injury, and a lower incidence of atrial fibrillation. In vascular surgery, evidence suggests that patients on ACE inhibitors who are undergoing surgery have less of a drop in cardiac output and may have improved creatinine clearance.

On the other hand, patients who remain on ACE inhibitors during surgery can experience a "profound" drop in blood pressure requiring immediate intervention, he said.

Data to support the continue vs. hold debate are sparse, but include a trial of 51 patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitors on the day of surgery or to have the drugs held for 12-24 hours before surgery. In all, 33 of the patients were on captopril (Capoten), and 18 were on enalapril (Vasotec).

The investigators found that among patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitor therapy, 7 of 7 on captopril and 9 of 14 on enalapril developed hypotension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) less than 90 mm Hg. In contrast, among patients assigned to the ACE-inhibitor hold protocol, only 2 of 11 on captopril and 4 of 19 on enalapril developed hypotension during surgery.

In a second randomized trial, investigators looked at 37 patients on an ARB who were randomly assigned to either discontinue ARB on the day before surgery (18 patients), or to receive their ARB 1 hour before anesthesia induction (19 patients).

The authors defined hypotension for their study as an SBP less than 80 mm Hg for more than 1 minute. They found that all 19 patients who continued on ARB had hypotension during surgery, compared with 12 of 18 who discontinued their ARB the day before. Patients who received their ARB on the day of surgery used significantly more vasoactive drugs. Despite the discontinuation of the ARB, there were no differences in hypertension between the groups in the recovery period. Postoperative cardiac complications occurred in 1 patient in each group.

In the final randomized study that Dr. Grant cited, 40 patients on an ACE inhibitor with good left-ventricular function were scheduled to undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). They were randomly assigned to hold or continue on ACE inhibitors on the day of surgery.

Patients in whom the ACE inhibitors were held before CABG had higher mean blood pressures than patients who continued on the drugs, and they used less vasopressor during the surgery. In contrast, patients who continued on ACE inhibitors needed more vasodilators after CABG and in the recovery period. The authors of this trial did not study other clinical endpoints, Dr. Grant noted.

Evidence from two observational studies was more equivocal, however.

In a retrospective observational study, investigators studied the relationship between the timing of discontinuing ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor subtype 1 antagonists (ARA) and the onset of hypotension in 267 patients scheduled for general surgery.

They found that patients exposed to an ACE inhibitor or ARA within 10 hours of anesthesia had an adjusted odds ratio of 1.74 for moderate hypotension (SBP 85 mm Hg or less; P = .04), but there was no difference in severe hypotension between these patients and those who discontinued the drugs more than 10 hours before surgery. There were no differences in either vasopressor use or postoperative complications, including unplanned intensive care unit stay, myocardial infarction, stroke, renal impairment, or death.

A second, smaller study compared 12 vascular surgery patients on ARB the day of surgery with matched cohorts of patients taking beta-blockers and/or calcium channel blockers the day of surgery, or ACE inhibitors held on the day of surgery.

Hypotension (SBP less than 90 mm Hg in this study) occurred in all of the patients on ARB but in only 60% (27 of 45) patients on the beta-blocker/calcium channel blockers, and in 67% (18 of 27) in the ACE-inhibitor hold cohort. The ARB patients were also less responsive to ephedrine and phenylephrine than other patients, and in some cases responded only to a vasopressin system agonist, Dr. Grant noted.

Finally, the authors of a random-effects meta-analysis of five studies with a total of 434 patients reported that patients receiving an immediate preoperative ACE inhibitor or ARA dose had a relative risk of 1.50 for developing hypotension requiring vasopressors at or shortly after induction of anesthesia, compared with patients who did not receive the drugs.

Dr. Grant noted that the American College of Physicians’ Smart Medicine guidelines on perioperative management of hypertensive patients recommend continuing ACE inhibitors "with caution," and they advise clinicians to avoid hypovolemia in patients maintained on ACE inhibitors during surgery. He said that in certain cases, it may be appropriate to continue surgical patients on ACE inhibitors or ARB, as in patients with hypertension that is difficult to control with multiple medications, or in those with severe heart disease who have adequate blood pressure.

Dr. Grant reported having no financial disclosures.

|

|

The findings of the studies presented by Dr. Grant have important implications for understanding the significant issue of hypotension that the postoperative patient may face. However, the studies are relatively small, and in some cases the results are conflicting. A larger randomized, controlled trial would help shed light on how we can better identify the patients who can benefit from these therapeutic choices.

Dr. Vera A. DePalo is associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I. She is the deputy medical editor of CHEST Physician.

|

|

The findings of the studies presented by Dr. Grant have important implications for understanding the significant issue of hypotension that the postoperative patient may face. However, the studies are relatively small, and in some cases the results are conflicting. A larger randomized, controlled trial would help shed light on how we can better identify the patients who can benefit from these therapeutic choices.

Dr. Vera A. DePalo is associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I. She is the deputy medical editor of CHEST Physician.

|

|

The findings of the studies presented by Dr. Grant have important implications for understanding the significant issue of hypotension that the postoperative patient may face. However, the studies are relatively small, and in some cases the results are conflicting. A larger randomized, controlled trial would help shed light on how we can better identify the patients who can benefit from these therapeutic choices.

Dr. Vera A. DePalo is associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I. She is the deputy medical editor of CHEST Physician.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – When it comes to holding or continuing with ACE inhibitors before surgery, all bets are off, a perioperative medicine consultant suggested.

Patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) have about a 50% risk of developing hypotension during surgery, and a significant proportion of those episodes could be severe, said Dr. Paul Grant, of the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

"I recommend having some sort of standard approach [to perioperative ACE inhibitor use] at your institution if that’s at all possible, either for a certain surgery type or across the board," he said at a meeting on perioperative medicine sponsored by the University of Miami.

Evidence from a small number of randomized trials and observational studies suggests that continuing ACE inhibitors during cardiac surgery may result in less cardiac enzyme release, less kidney injury, and a lower incidence of atrial fibrillation. In vascular surgery, evidence suggests that patients on ACE inhibitors who are undergoing surgery have less of a drop in cardiac output and may have improved creatinine clearance.

On the other hand, patients who remain on ACE inhibitors during surgery can experience a "profound" drop in blood pressure requiring immediate intervention, he said.

Data to support the continue vs. hold debate are sparse, but include a trial of 51 patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitors on the day of surgery or to have the drugs held for 12-24 hours before surgery. In all, 33 of the patients were on captopril (Capoten), and 18 were on enalapril (Vasotec).

The investigators found that among patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitor therapy, 7 of 7 on captopril and 9 of 14 on enalapril developed hypotension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) less than 90 mm Hg. In contrast, among patients assigned to the ACE-inhibitor hold protocol, only 2 of 11 on captopril and 4 of 19 on enalapril developed hypotension during surgery.

In a second randomized trial, investigators looked at 37 patients on an ARB who were randomly assigned to either discontinue ARB on the day before surgery (18 patients), or to receive their ARB 1 hour before anesthesia induction (19 patients).

The authors defined hypotension for their study as an SBP less than 80 mm Hg for more than 1 minute. They found that all 19 patients who continued on ARB had hypotension during surgery, compared with 12 of 18 who discontinued their ARB the day before. Patients who received their ARB on the day of surgery used significantly more vasoactive drugs. Despite the discontinuation of the ARB, there were no differences in hypertension between the groups in the recovery period. Postoperative cardiac complications occurred in 1 patient in each group.

In the final randomized study that Dr. Grant cited, 40 patients on an ACE inhibitor with good left-ventricular function were scheduled to undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). They were randomly assigned to hold or continue on ACE inhibitors on the day of surgery.

Patients in whom the ACE inhibitors were held before CABG had higher mean blood pressures than patients who continued on the drugs, and they used less vasopressor during the surgery. In contrast, patients who continued on ACE inhibitors needed more vasodilators after CABG and in the recovery period. The authors of this trial did not study other clinical endpoints, Dr. Grant noted.

Evidence from two observational studies was more equivocal, however.

In a retrospective observational study, investigators studied the relationship between the timing of discontinuing ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor subtype 1 antagonists (ARA) and the onset of hypotension in 267 patients scheduled for general surgery.

They found that patients exposed to an ACE inhibitor or ARA within 10 hours of anesthesia had an adjusted odds ratio of 1.74 for moderate hypotension (SBP 85 mm Hg or less; P = .04), but there was no difference in severe hypotension between these patients and those who discontinued the drugs more than 10 hours before surgery. There were no differences in either vasopressor use or postoperative complications, including unplanned intensive care unit stay, myocardial infarction, stroke, renal impairment, or death.

A second, smaller study compared 12 vascular surgery patients on ARB the day of surgery with matched cohorts of patients taking beta-blockers and/or calcium channel blockers the day of surgery, or ACE inhibitors held on the day of surgery.

Hypotension (SBP less than 90 mm Hg in this study) occurred in all of the patients on ARB but in only 60% (27 of 45) patients on the beta-blocker/calcium channel blockers, and in 67% (18 of 27) in the ACE-inhibitor hold cohort. The ARB patients were also less responsive to ephedrine and phenylephrine than other patients, and in some cases responded only to a vasopressin system agonist, Dr. Grant noted.

Finally, the authors of a random-effects meta-analysis of five studies with a total of 434 patients reported that patients receiving an immediate preoperative ACE inhibitor or ARA dose had a relative risk of 1.50 for developing hypotension requiring vasopressors at or shortly after induction of anesthesia, compared with patients who did not receive the drugs.

Dr. Grant noted that the American College of Physicians’ Smart Medicine guidelines on perioperative management of hypertensive patients recommend continuing ACE inhibitors "with caution," and they advise clinicians to avoid hypovolemia in patients maintained on ACE inhibitors during surgery. He said that in certain cases, it may be appropriate to continue surgical patients on ACE inhibitors or ARB, as in patients with hypertension that is difficult to control with multiple medications, or in those with severe heart disease who have adequate blood pressure.

Dr. Grant reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – When it comes to holding or continuing with ACE inhibitors before surgery, all bets are off, a perioperative medicine consultant suggested.

Patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) have about a 50% risk of developing hypotension during surgery, and a significant proportion of those episodes could be severe, said Dr. Paul Grant, of the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

"I recommend having some sort of standard approach [to perioperative ACE inhibitor use] at your institution if that’s at all possible, either for a certain surgery type or across the board," he said at a meeting on perioperative medicine sponsored by the University of Miami.

Evidence from a small number of randomized trials and observational studies suggests that continuing ACE inhibitors during cardiac surgery may result in less cardiac enzyme release, less kidney injury, and a lower incidence of atrial fibrillation. In vascular surgery, evidence suggests that patients on ACE inhibitors who are undergoing surgery have less of a drop in cardiac output and may have improved creatinine clearance.

On the other hand, patients who remain on ACE inhibitors during surgery can experience a "profound" drop in blood pressure requiring immediate intervention, he said.

Data to support the continue vs. hold debate are sparse, but include a trial of 51 patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitors on the day of surgery or to have the drugs held for 12-24 hours before surgery. In all, 33 of the patients were on captopril (Capoten), and 18 were on enalapril (Vasotec).

The investigators found that among patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitor therapy, 7 of 7 on captopril and 9 of 14 on enalapril developed hypotension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) less than 90 mm Hg. In contrast, among patients assigned to the ACE-inhibitor hold protocol, only 2 of 11 on captopril and 4 of 19 on enalapril developed hypotension during surgery.

In a second randomized trial, investigators looked at 37 patients on an ARB who were randomly assigned to either discontinue ARB on the day before surgery (18 patients), or to receive their ARB 1 hour before anesthesia induction (19 patients).

The authors defined hypotension for their study as an SBP less than 80 mm Hg for more than 1 minute. They found that all 19 patients who continued on ARB had hypotension during surgery, compared with 12 of 18 who discontinued their ARB the day before. Patients who received their ARB on the day of surgery used significantly more vasoactive drugs. Despite the discontinuation of the ARB, there were no differences in hypertension between the groups in the recovery period. Postoperative cardiac complications occurred in 1 patient in each group.

In the final randomized study that Dr. Grant cited, 40 patients on an ACE inhibitor with good left-ventricular function were scheduled to undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). They were randomly assigned to hold or continue on ACE inhibitors on the day of surgery.

Patients in whom the ACE inhibitors were held before CABG had higher mean blood pressures than patients who continued on the drugs, and they used less vasopressor during the surgery. In contrast, patients who continued on ACE inhibitors needed more vasodilators after CABG and in the recovery period. The authors of this trial did not study other clinical endpoints, Dr. Grant noted.

Evidence from two observational studies was more equivocal, however.

In a retrospective observational study, investigators studied the relationship between the timing of discontinuing ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor subtype 1 antagonists (ARA) and the onset of hypotension in 267 patients scheduled for general surgery.

They found that patients exposed to an ACE inhibitor or ARA within 10 hours of anesthesia had an adjusted odds ratio of 1.74 for moderate hypotension (SBP 85 mm Hg or less; P = .04), but there was no difference in severe hypotension between these patients and those who discontinued the drugs more than 10 hours before surgery. There were no differences in either vasopressor use or postoperative complications, including unplanned intensive care unit stay, myocardial infarction, stroke, renal impairment, or death.

A second, smaller study compared 12 vascular surgery patients on ARB the day of surgery with matched cohorts of patients taking beta-blockers and/or calcium channel blockers the day of surgery, or ACE inhibitors held on the day of surgery.

Hypotension (SBP less than 90 mm Hg in this study) occurred in all of the patients on ARB but in only 60% (27 of 45) patients on the beta-blocker/calcium channel blockers, and in 67% (18 of 27) in the ACE-inhibitor hold cohort. The ARB patients were also less responsive to ephedrine and phenylephrine than other patients, and in some cases responded only to a vasopressin system agonist, Dr. Grant noted.

Finally, the authors of a random-effects meta-analysis of five studies with a total of 434 patients reported that patients receiving an immediate preoperative ACE inhibitor or ARA dose had a relative risk of 1.50 for developing hypotension requiring vasopressors at or shortly after induction of anesthesia, compared with patients who did not receive the drugs.

Dr. Grant noted that the American College of Physicians’ Smart Medicine guidelines on perioperative management of hypertensive patients recommend continuing ACE inhibitors "with caution," and they advise clinicians to avoid hypovolemia in patients maintained on ACE inhibitors during surgery. He said that in certain cases, it may be appropriate to continue surgical patients on ACE inhibitors or ARB, as in patients with hypertension that is difficult to control with multiple medications, or in those with severe heart disease who have adequate blood pressure.

Dr. Grant reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE PERIOPERATIVE MEDICINE SUMMIT

Major finding: Among patients randomized to continue ACE inhibitor therapy during surgery, 16 of 21 patients developed hypotension, compared with only 6 of 30 patients who discontinued their ACE inhibitors the day before.

Data source: Review of evidence on the perioperative management of patients with hypertension treated with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers.

Disclosures: Dr. Grant reported having no financial disclosures.

TAVR: More procedural success with balloon-expandable valves

Patients with high-risk aortic stenosis undergoing transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement saw better results with balloon-expandable valve prostheses, compared with self-expanding valve prostheses, according to results from the first multicenter, randomized trial comparing the two types of devices directly.

For their research, presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Mohamed Abdel-Wahab of the Segeberger Kliniken in Bad Segeberg, Germany, and his associates randomized 241 patients with severe aortic stenosis to either a balloon-expandable valve (n = 121; 43% men) or a self-expanding valve (n = 120; 28.3% men). Patients were recruited from five centers in Germany between March 2012 and December 2013, and followed up for 30 days post procedure.

The trial’s main endpoint was device success – a 4-point composite, incorporating correct device positioning, performance of the valve without more than mild regurgitation, successful vascular access and deployment of the device and retrieval of the delivery system, and only one valve implanted.

Secondary endpoints included cardiovascular mortality, need for new pacemaker placement post procedure, major stroke and other vascular events, and a combined safety endpoint of all-cause mortality, major stroke, bleeding, kidney injury, myocardial infarction, major vascular complications, and repeat procedure for valve-related dysfunction, they said in a report on their research that was simultaneously published in JAMA (2014 March 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3316]).

Device success was seen as markedly higher among patients receiving the balloon-expandable valves (95.9% of patients, compared with 77.5%; relative risk 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.37; P less than .001), thanks mainly to less incidence of moderate to severe aortic regurgitation after valve placement (4.1% vs. 18.3%; RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09-0.58; P less than .001).

Observational studies have found widely differing outcomes in aortic regurgitation associated with the different devices, due in part to "challenges in identification and quantification of aortic regurgitation after TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], but also to the observational and nonrandomized nature of all reported comparisons," Dr. Abdel-Wahab and his colleagues wrote. This study used angiographic, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic assessments of aortic regurgitation following TAVR.

At 30 days post procedure, new pacemakers had been placed half as frequently in the balloon-expandable valve group (17.3% vs. 37.6%, P = .001). Altogether five patients were rehospitalized for heart failure in the self-expanding valve group, compared with none in the balloon-expandable group.

Neither 30-day cardiovascular mortality nor vascular nor bleeding complications were significantly different between the two groups. In the balloon-expandable group, 30-day mortality was 4.1%, compared with 4.3% for the self-expanding group. The combined safety end point occurred in 18.2% of those in the balloon-expandable valve group and 23.1% of the self-expanding group (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.48-1.30; P = .42).

However, patients in the balloon-expandable arm saw higher numerical incidence of stroke. Stroke was seen in seven patients (three major and four minor strokes), compared with three (all major strokes) in the self-expanding valve group.

The investigators described the use of core laboratory–adjudicated angiography and the lack of an echocardiographic core laboratory as potential limitations of their study. Long-term follow-up was needed, they said, to "determine whether differences in device success will translate into a clinically relevant overall benefit for the balloon-expandable valve."

The study was sponsored by Dr. Abdel-Wahab’s institution. Dr. Abdel-Wahab disclosed support from Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Boston Scientific. Four of his 11 coauthors disclosed support from Abbott Vascular, Terumo Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo, Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and/or Boston Scientific.

The lack of a head-to-head comparison in a multicenter, randomized clinical trial has made it difficult to choose the appropriate device for a given patient. The report by Abdel-Wahab et al. on the CHOICE trial, a randomized clinical trial comparing balloon-expandable and self-expanding valves, fills this void, albeit partially. The authors conducted a robust randomized trial involving 241 patients at five centers and experienced investigators capable of implanting either valve with expertise.

The balloon-expandable valve implantation resulted in a higher device success than did the self-expanding valve, with device success of 95.9% (116 of 121 patients) in the balloon-expandable valve group and 77.5% (93 of 120 patients) in the self-expanding valve group. This result is important but should not be interpreted as a surrogate for long-term outcomes, such as death, stroke, and quality of life. In this relatively small study, there was no difference in 30-day cardiovascular mortality (4.3% in the self-expanding valve group and 4.1% in the balloon-expandable valve group), Dr. Murat Tuzcu and Dr. Kapadia wrote in an accompanying editorial in JAMA (2014 March 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3317]).

Although the two study groups were, for the most part well balanced, more women were in the self-expanding group than in the balloon-expandable group. In the PARTNER trial, women had greater benefit from TAVR with balloon-expandable valve, compared with men. In the CHOICE trial, sex imbalance may have introduced some bias that could not be addressed because of the small size of the study. In addition, paravalvular regurgitation and the need for a second valve were significantly less for balloon-expandable valve, whereas stroke and coronary occlusion were numerically, although not statistically, higher for the balloon-expandable valve. These and other points have been discussed extensively in the literature, as they are critical in deciding which valve to use in a given patient.

Dr. E. Murat Tuzcu and Dr. Samir R. Kapadia are both at the Heart and Vascular Institute, department of cardiology, Cleveland Clinic.

The lack of a head-to-head comparison in a multicenter, randomized clinical trial has made it difficult to choose the appropriate device for a given patient. The report by Abdel-Wahab et al. on the CHOICE trial, a randomized clinical trial comparing balloon-expandable and self-expanding valves, fills this void, albeit partially. The authors conducted a robust randomized trial involving 241 patients at five centers and experienced investigators capable of implanting either valve with expertise.

The balloon-expandable valve implantation resulted in a higher device success than did the self-expanding valve, with device success of 95.9% (116 of 121 patients) in the balloon-expandable valve group and 77.5% (93 of 120 patients) in the self-expanding valve group. This result is important but should not be interpreted as a surrogate for long-term outcomes, such as death, stroke, and quality of life. In this relatively small study, there was no difference in 30-day cardiovascular mortality (4.3% in the self-expanding valve group and 4.1% in the balloon-expandable valve group), Dr. Murat Tuzcu and Dr. Kapadia wrote in an accompanying editorial in JAMA (2014 March 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3317]).

Although the two study groups were, for the most part well balanced, more women were in the self-expanding group than in the balloon-expandable group. In the PARTNER trial, women had greater benefit from TAVR with balloon-expandable valve, compared with men. In the CHOICE trial, sex imbalance may have introduced some bias that could not be addressed because of the small size of the study. In addition, paravalvular regurgitation and the need for a second valve were significantly less for balloon-expandable valve, whereas stroke and coronary occlusion were numerically, although not statistically, higher for the balloon-expandable valve. These and other points have been discussed extensively in the literature, as they are critical in deciding which valve to use in a given patient.

Dr. E. Murat Tuzcu and Dr. Samir R. Kapadia are both at the Heart and Vascular Institute, department of cardiology, Cleveland Clinic.

The lack of a head-to-head comparison in a multicenter, randomized clinical trial has made it difficult to choose the appropriate device for a given patient. The report by Abdel-Wahab et al. on the CHOICE trial, a randomized clinical trial comparing balloon-expandable and self-expanding valves, fills this void, albeit partially. The authors conducted a robust randomized trial involving 241 patients at five centers and experienced investigators capable of implanting either valve with expertise.

The balloon-expandable valve implantation resulted in a higher device success than did the self-expanding valve, with device success of 95.9% (116 of 121 patients) in the balloon-expandable valve group and 77.5% (93 of 120 patients) in the self-expanding valve group. This result is important but should not be interpreted as a surrogate for long-term outcomes, such as death, stroke, and quality of life. In this relatively small study, there was no difference in 30-day cardiovascular mortality (4.3% in the self-expanding valve group and 4.1% in the balloon-expandable valve group), Dr. Murat Tuzcu and Dr. Kapadia wrote in an accompanying editorial in JAMA (2014 March 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3317]).

Although the two study groups were, for the most part well balanced, more women were in the self-expanding group than in the balloon-expandable group. In the PARTNER trial, women had greater benefit from TAVR with balloon-expandable valve, compared with men. In the CHOICE trial, sex imbalance may have introduced some bias that could not be addressed because of the small size of the study. In addition, paravalvular regurgitation and the need for a second valve were significantly less for balloon-expandable valve, whereas stroke and coronary occlusion were numerically, although not statistically, higher for the balloon-expandable valve. These and other points have been discussed extensively in the literature, as they are critical in deciding which valve to use in a given patient.

Dr. E. Murat Tuzcu and Dr. Samir R. Kapadia are both at the Heart and Vascular Institute, department of cardiology, Cleveland Clinic.

Patients with high-risk aortic stenosis undergoing transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement saw better results with balloon-expandable valve prostheses, compared with self-expanding valve prostheses, according to results from the first multicenter, randomized trial comparing the two types of devices directly.

For their research, presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Mohamed Abdel-Wahab of the Segeberger Kliniken in Bad Segeberg, Germany, and his associates randomized 241 patients with severe aortic stenosis to either a balloon-expandable valve (n = 121; 43% men) or a self-expanding valve (n = 120; 28.3% men). Patients were recruited from five centers in Germany between March 2012 and December 2013, and followed up for 30 days post procedure.

The trial’s main endpoint was device success – a 4-point composite, incorporating correct device positioning, performance of the valve without more than mild regurgitation, successful vascular access and deployment of the device and retrieval of the delivery system, and only one valve implanted.

Secondary endpoints included cardiovascular mortality, need for new pacemaker placement post procedure, major stroke and other vascular events, and a combined safety endpoint of all-cause mortality, major stroke, bleeding, kidney injury, myocardial infarction, major vascular complications, and repeat procedure for valve-related dysfunction, they said in a report on their research that was simultaneously published in JAMA (2014 March 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3316]).

Device success was seen as markedly higher among patients receiving the balloon-expandable valves (95.9% of patients, compared with 77.5%; relative risk 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.37; P less than .001), thanks mainly to less incidence of moderate to severe aortic regurgitation after valve placement (4.1% vs. 18.3%; RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09-0.58; P less than .001).

Observational studies have found widely differing outcomes in aortic regurgitation associated with the different devices, due in part to "challenges in identification and quantification of aortic regurgitation after TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], but also to the observational and nonrandomized nature of all reported comparisons," Dr. Abdel-Wahab and his colleagues wrote. This study used angiographic, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic assessments of aortic regurgitation following TAVR.

At 30 days post procedure, new pacemakers had been placed half as frequently in the balloon-expandable valve group (17.3% vs. 37.6%, P = .001). Altogether five patients were rehospitalized for heart failure in the self-expanding valve group, compared with none in the balloon-expandable group.

Neither 30-day cardiovascular mortality nor vascular nor bleeding complications were significantly different between the two groups. In the balloon-expandable group, 30-day mortality was 4.1%, compared with 4.3% for the self-expanding group. The combined safety end point occurred in 18.2% of those in the balloon-expandable valve group and 23.1% of the self-expanding group (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.48-1.30; P = .42).

However, patients in the balloon-expandable arm saw higher numerical incidence of stroke. Stroke was seen in seven patients (three major and four minor strokes), compared with three (all major strokes) in the self-expanding valve group.

The investigators described the use of core laboratory–adjudicated angiography and the lack of an echocardiographic core laboratory as potential limitations of their study. Long-term follow-up was needed, they said, to "determine whether differences in device success will translate into a clinically relevant overall benefit for the balloon-expandable valve."

The study was sponsored by Dr. Abdel-Wahab’s institution. Dr. Abdel-Wahab disclosed support from Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Boston Scientific. Four of his 11 coauthors disclosed support from Abbott Vascular, Terumo Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo, Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and/or Boston Scientific.

Patients with high-risk aortic stenosis undergoing transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement saw better results with balloon-expandable valve prostheses, compared with self-expanding valve prostheses, according to results from the first multicenter, randomized trial comparing the two types of devices directly.

For their research, presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Mohamed Abdel-Wahab of the Segeberger Kliniken in Bad Segeberg, Germany, and his associates randomized 241 patients with severe aortic stenosis to either a balloon-expandable valve (n = 121; 43% men) or a self-expanding valve (n = 120; 28.3% men). Patients were recruited from five centers in Germany between March 2012 and December 2013, and followed up for 30 days post procedure.

The trial’s main endpoint was device success – a 4-point composite, incorporating correct device positioning, performance of the valve without more than mild regurgitation, successful vascular access and deployment of the device and retrieval of the delivery system, and only one valve implanted.

Secondary endpoints included cardiovascular mortality, need for new pacemaker placement post procedure, major stroke and other vascular events, and a combined safety endpoint of all-cause mortality, major stroke, bleeding, kidney injury, myocardial infarction, major vascular complications, and repeat procedure for valve-related dysfunction, they said in a report on their research that was simultaneously published in JAMA (2014 March 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3316]).

Device success was seen as markedly higher among patients receiving the balloon-expandable valves (95.9% of patients, compared with 77.5%; relative risk 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.37; P less than .001), thanks mainly to less incidence of moderate to severe aortic regurgitation after valve placement (4.1% vs. 18.3%; RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09-0.58; P less than .001).

Observational studies have found widely differing outcomes in aortic regurgitation associated with the different devices, due in part to "challenges in identification and quantification of aortic regurgitation after TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], but also to the observational and nonrandomized nature of all reported comparisons," Dr. Abdel-Wahab and his colleagues wrote. This study used angiographic, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic assessments of aortic regurgitation following TAVR.

At 30 days post procedure, new pacemakers had been placed half as frequently in the balloon-expandable valve group (17.3% vs. 37.6%, P = .001). Altogether five patients were rehospitalized for heart failure in the self-expanding valve group, compared with none in the balloon-expandable group.

Neither 30-day cardiovascular mortality nor vascular nor bleeding complications were significantly different between the two groups. In the balloon-expandable group, 30-day mortality was 4.1%, compared with 4.3% for the self-expanding group. The combined safety end point occurred in 18.2% of those in the balloon-expandable valve group and 23.1% of the self-expanding group (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.48-1.30; P = .42).

However, patients in the balloon-expandable arm saw higher numerical incidence of stroke. Stroke was seen in seven patients (three major and four minor strokes), compared with three (all major strokes) in the self-expanding valve group.

The investigators described the use of core laboratory–adjudicated angiography and the lack of an echocardiographic core laboratory as potential limitations of their study. Long-term follow-up was needed, they said, to "determine whether differences in device success will translate into a clinically relevant overall benefit for the balloon-expandable valve."

The study was sponsored by Dr. Abdel-Wahab’s institution. Dr. Abdel-Wahab disclosed support from Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Boston Scientific. Four of his 11 coauthors disclosed support from Abbott Vascular, Terumo Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo, Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and/or Boston Scientific.

FROM ACC 14

Major finding: Balloon-expandable valve systems were more often successfully deployed and were associated with less aortic regurgitation in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), compared with self-expandable device systems, while 30-day safety and mortality between the devices was comparable.

Data source: A randomized, controlled trial enrolling 241 patients from five study sites in Germany.

Disclosures: Lead author and several coauthors disclosed financial relationships with several device manufacturers.

Wait! Put elective surgery on hold after stent placement

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The presence of a coronary artery stent is not a barrier to noncardiac surgery, but it may change the timing of surgery and perioperative management of the patient, a hospitalist cautions.

Patients who receive bare-metal stents should delay having elective surgery for at least 6 weeks after stent placement, and those who receive a drug-eluting stent should put off elective procedures for at least a year, said Dr. Amir K. Jaffer, professor of medicine and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The type of stent, its placement, and the time since placement are just some of the key pieces of information that clinicians need to manage patients, Dr. Jaffer said at a meeting on perioperative medicine sponsored by the University of Miami.

"You want to try to get that [information] card if you can from the patient, about where the stents were placed, and if they don’t have the card handy, you really need to go to the procedure note, because the patient may or may not know if it was a drug-eluting stent," he said.

Other vital pieces of the perioperative puzzle are which coronary vessel the stent was implanted in; when the stent was implanted; what drug, if any (sirolimus or paclitaxel) is eluted by the stent; whether there were surgical or postoperative complications; prior history of stent thrombosis; the patient’s comorbidities; duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy; and how the patient has fared on therapy.

Prior to an elective noncardiac procedure, clinicians must consider patient risk factors, including indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk factors for thrombosis or thromboembolism, and type of antithrombotic agent; and surgical risk factors, including type of procedure, bleeding risk, thromboembolism risk, and time off antithrombotic therapy.

When to stop antithrombotic agents

Dr. Jaffer noted that because aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of platelet cyclooxygenase and the circulating platelet pool is replaced every 7 to 10 days, patients on aspirin as part of their dual-antiplatelet therapy should stop taking the drug from 7 to 10 days before scheduled surgery.

Thienopyridines/P2Y12 receptor antagonists such as clopidogrel (Plavix) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) work by inhibiting adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor-mediated platelet activation and aggregation. Dr. Jaffer said that although guidelines recommend stopping these agents 7 days before surgery, there is evidence to suggest that 5 days may be a sufficient window of safety.

It is also important to take into consideration the pharmacokinetic profiles of the specific antiplatelet agents. For example, ticagrelor has a more rapid onset and greater degree of platelet-aggregation inhibition than clopidogrel, although the time from stopping each agent until the return to near-baseline platelet aggregation is similar, on the order of about 120 hours (5 days) or longer, he said.

Risk varies by surgery type

The type of surgery is also important, as certain procedures – such as neurocranial surgery, spinal canal surgery, and procedures performed in the posterior chamber of the eye – carry a high risk for hemorrhage and are likely to require blood transfusions.

Dr. Jaffer noted that in 2007, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association issued a joint advisory on antiplatelet therapy and noncardiac surgery, which warned health care providers about the potentially catastrophic risks of stopping thienopyridines prematurely, which could result in acute stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death. The guidelines recommend waiting a minimum of 6 weeks for noncardiac surgery following implantation of a bare-metal stent, and 1 year after a drug-eluting stent.

He pointed to two studies from the Mayo Clinic published in 2008. The first study showed that the risk of major cardiac adverse events among patients with a bare-metal stent undergoing noncardiac surgery within 30 days of stent placement was approximately 10%, but diminished to 2.7% at 91 days after placement (Anesthesiology 2008;109:588-95). The second study showed that the risk of major cardiac adverse events was 6.1% within 90 days after implantation of a drug-eluting stent, with the risk dwindling to 3.1% after 1 year (Anesthesiology 2008;109:596-604).

If urgent surgery such as a hemicolectomy for colon cancer is required within 6 months of drug-eluting stent implantation, the patient should continue on dual-antiplatelet therapy, Dr. Jaffer said. If the surgery is from 6 months to 1 year after implantation in these patients, the patient should be continued on at least 81 mg aspirin, but if the patient is taking clopidogrel, he or she should have the thienopyridine discontinued 5 days before surgery and the drug resumed as soon as possible after surgery with a 300-mg loading dose, followed by 75 mg daily. If the patient is not yet able to eat, the dual-antiplatelet therapy should be delivered via nasogastric tube, he said.

Dr. Jaffer reported serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and other companies. Dr. Jaffer also serves on the editorial advisory board of Hospitalist News.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The presence of a coronary artery stent is not a barrier to noncardiac surgery, but it may change the timing of surgery and perioperative management of the patient, a hospitalist cautions.

Patients who receive bare-metal stents should delay having elective surgery for at least 6 weeks after stent placement, and those who receive a drug-eluting stent should put off elective procedures for at least a year, said Dr. Amir K. Jaffer, professor of medicine and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The type of stent, its placement, and the time since placement are just some of the key pieces of information that clinicians need to manage patients, Dr. Jaffer said at a meeting on perioperative medicine sponsored by the University of Miami.

"You want to try to get that [information] card if you can from the patient, about where the stents were placed, and if they don’t have the card handy, you really need to go to the procedure note, because the patient may or may not know if it was a drug-eluting stent," he said.

Other vital pieces of the perioperative puzzle are which coronary vessel the stent was implanted in; when the stent was implanted; what drug, if any (sirolimus or paclitaxel) is eluted by the stent; whether there were surgical or postoperative complications; prior history of stent thrombosis; the patient’s comorbidities; duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy; and how the patient has fared on therapy.

Prior to an elective noncardiac procedure, clinicians must consider patient risk factors, including indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk factors for thrombosis or thromboembolism, and type of antithrombotic agent; and surgical risk factors, including type of procedure, bleeding risk, thromboembolism risk, and time off antithrombotic therapy.

When to stop antithrombotic agents

Dr. Jaffer noted that because aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of platelet cyclooxygenase and the circulating platelet pool is replaced every 7 to 10 days, patients on aspirin as part of their dual-antiplatelet therapy should stop taking the drug from 7 to 10 days before scheduled surgery.

Thienopyridines/P2Y12 receptor antagonists such as clopidogrel (Plavix) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) work by inhibiting adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor-mediated platelet activation and aggregation. Dr. Jaffer said that although guidelines recommend stopping these agents 7 days before surgery, there is evidence to suggest that 5 days may be a sufficient window of safety.

It is also important to take into consideration the pharmacokinetic profiles of the specific antiplatelet agents. For example, ticagrelor has a more rapid onset and greater degree of platelet-aggregation inhibition than clopidogrel, although the time from stopping each agent until the return to near-baseline platelet aggregation is similar, on the order of about 120 hours (5 days) or longer, he said.

Risk varies by surgery type

The type of surgery is also important, as certain procedures – such as neurocranial surgery, spinal canal surgery, and procedures performed in the posterior chamber of the eye – carry a high risk for hemorrhage and are likely to require blood transfusions.

Dr. Jaffer noted that in 2007, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association issued a joint advisory on antiplatelet therapy and noncardiac surgery, which warned health care providers about the potentially catastrophic risks of stopping thienopyridines prematurely, which could result in acute stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death. The guidelines recommend waiting a minimum of 6 weeks for noncardiac surgery following implantation of a bare-metal stent, and 1 year after a drug-eluting stent.

He pointed to two studies from the Mayo Clinic published in 2008. The first study showed that the risk of major cardiac adverse events among patients with a bare-metal stent undergoing noncardiac surgery within 30 days of stent placement was approximately 10%, but diminished to 2.7% at 91 days after placement (Anesthesiology 2008;109:588-95). The second study showed that the risk of major cardiac adverse events was 6.1% within 90 days after implantation of a drug-eluting stent, with the risk dwindling to 3.1% after 1 year (Anesthesiology 2008;109:596-604).

If urgent surgery such as a hemicolectomy for colon cancer is required within 6 months of drug-eluting stent implantation, the patient should continue on dual-antiplatelet therapy, Dr. Jaffer said. If the surgery is from 6 months to 1 year after implantation in these patients, the patient should be continued on at least 81 mg aspirin, but if the patient is taking clopidogrel, he or she should have the thienopyridine discontinued 5 days before surgery and the drug resumed as soon as possible after surgery with a 300-mg loading dose, followed by 75 mg daily. If the patient is not yet able to eat, the dual-antiplatelet therapy should be delivered via nasogastric tube, he said.

Dr. Jaffer reported serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and other companies. Dr. Jaffer also serves on the editorial advisory board of Hospitalist News.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The presence of a coronary artery stent is not a barrier to noncardiac surgery, but it may change the timing of surgery and perioperative management of the patient, a hospitalist cautions.

Patients who receive bare-metal stents should delay having elective surgery for at least 6 weeks after stent placement, and those who receive a drug-eluting stent should put off elective procedures for at least a year, said Dr. Amir K. Jaffer, professor of medicine and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The type of stent, its placement, and the time since placement are just some of the key pieces of information that clinicians need to manage patients, Dr. Jaffer said at a meeting on perioperative medicine sponsored by the University of Miami.

"You want to try to get that [information] card if you can from the patient, about where the stents were placed, and if they don’t have the card handy, you really need to go to the procedure note, because the patient may or may not know if it was a drug-eluting stent," he said.

Other vital pieces of the perioperative puzzle are which coronary vessel the stent was implanted in; when the stent was implanted; what drug, if any (sirolimus or paclitaxel) is eluted by the stent; whether there were surgical or postoperative complications; prior history of stent thrombosis; the patient’s comorbidities; duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy; and how the patient has fared on therapy.

Prior to an elective noncardiac procedure, clinicians must consider patient risk factors, including indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk factors for thrombosis or thromboembolism, and type of antithrombotic agent; and surgical risk factors, including type of procedure, bleeding risk, thromboembolism risk, and time off antithrombotic therapy.

When to stop antithrombotic agents

Dr. Jaffer noted that because aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of platelet cyclooxygenase and the circulating platelet pool is replaced every 7 to 10 days, patients on aspirin as part of their dual-antiplatelet therapy should stop taking the drug from 7 to 10 days before scheduled surgery.

Thienopyridines/P2Y12 receptor antagonists such as clopidogrel (Plavix) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) work by inhibiting adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor-mediated platelet activation and aggregation. Dr. Jaffer said that although guidelines recommend stopping these agents 7 days before surgery, there is evidence to suggest that 5 days may be a sufficient window of safety.

It is also important to take into consideration the pharmacokinetic profiles of the specific antiplatelet agents. For example, ticagrelor has a more rapid onset and greater degree of platelet-aggregation inhibition than clopidogrel, although the time from stopping each agent until the return to near-baseline platelet aggregation is similar, on the order of about 120 hours (5 days) or longer, he said.

Risk varies by surgery type

The type of surgery is also important, as certain procedures – such as neurocranial surgery, spinal canal surgery, and procedures performed in the posterior chamber of the eye – carry a high risk for hemorrhage and are likely to require blood transfusions.

Dr. Jaffer noted that in 2007, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association issued a joint advisory on antiplatelet therapy and noncardiac surgery, which warned health care providers about the potentially catastrophic risks of stopping thienopyridines prematurely, which could result in acute stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death. The guidelines recommend waiting a minimum of 6 weeks for noncardiac surgery following implantation of a bare-metal stent, and 1 year after a drug-eluting stent.

He pointed to two studies from the Mayo Clinic published in 2008. The first study showed that the risk of major cardiac adverse events among patients with a bare-metal stent undergoing noncardiac surgery within 30 days of stent placement was approximately 10%, but diminished to 2.7% at 91 days after placement (Anesthesiology 2008;109:588-95). The second study showed that the risk of major cardiac adverse events was 6.1% within 90 days after implantation of a drug-eluting stent, with the risk dwindling to 3.1% after 1 year (Anesthesiology 2008;109:596-604).

If urgent surgery such as a hemicolectomy for colon cancer is required within 6 months of drug-eluting stent implantation, the patient should continue on dual-antiplatelet therapy, Dr. Jaffer said. If the surgery is from 6 months to 1 year after implantation in these patients, the patient should be continued on at least 81 mg aspirin, but if the patient is taking clopidogrel, he or she should have the thienopyridine discontinued 5 days before surgery and the drug resumed as soon as possible after surgery with a 300-mg loading dose, followed by 75 mg daily. If the patient is not yet able to eat, the dual-antiplatelet therapy should be delivered via nasogastric tube, he said.

Dr. Jaffer reported serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and other companies. Dr. Jaffer also serves on the editorial advisory board of Hospitalist News.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PERIOPERATIVE MEDICINE SUMMIT

Major finding: Elective noncardiac surgery should be delayed for at least 6 weeks following implantation of a bare-metal stent, and 1 year after implantation of a drug-eluting stent.

Data source: Evidence-based review of data on the risk of adverse events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary artery stents.

Disclosures: Dr. Jaffer reported serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and other companies. Dr. Jaffer also serves on the editorial advisory board of Hospitalist News.

Medicare to cover cardiac rehab for some HF patients

Medicare will begin covering cardiac rehabilitation for patients with stable, chronic heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the new policy on Feb. 18.

About 5 million Americans have heart failure, but only half have an ejection fraction of less than 35%, Dr. Joseph A. Hill, chief of cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. Dr. Hill is chairman of the Heart Failure Society of America’s advocacy committee.

The HFSA, along with the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the American Heart Association (AHA), submitted a formal request to the CMS to add heart failure to the list of approved indications for coverage for cardiac rehabilitation. The agency began its analysis process in June 2013.

At that time, cardiac rehab was covered only for acute myocardial infarction within the preceding 12 months, coronary artery bypass surgery, current stable angina pectoris, heart valve repair or replacement, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or coronary stenting, and a heart or heart-lung transplant. Cardiac rehab includes physician prescribed exercise; risk factor modification, including education, counseling, and behavioral intervention; psychosocial assessment; and outcomes assessment.

Physician supervision is required for coverage.

The CMS said it had reconsidered coverage for some heart failure patients as a result of the HF-Action study, published in 2009 (JAMA 2009;301:1439-50). That study "provided the best evidence of benefit" in the HF patient group, but in particular for patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II-IV symptoms.

Specifically, the coverage is extended to "beneficiaries with stable, chronic heart failure defined as patients with left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and [NYHA] class II to IV symptoms despite being on optimal heart failure therapy for at least six weeks." The decision defines stable patients as those who have not had recent (within the past 6 weeks) or planned (within the past 6 months) major cardiovascular hospitalizations or procedures.

"We conclude that the evidence that supports the clinical benefits of the individual components of CR programs is sufficient to determine that participation in these programs improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HF," the CMS noted in its analysis.

"We’re very pleased," with the CMS decision, said Dr. Hill.

The ACC said it was still evaluating the decision. But Dr. M. Eugene Sherman, chairman of the ACC’s Advocacy Steering Committee, added that "we are pleased to see Medicare expand coverage of cardiac rehabilitation services, as the ACC requested, to a new patient population where medical and scientific literature demonstrates a medical benefit."

Dr. Hill said that the HFSA and others were hopeful that the CMS would eventually expand coverage of rehab to the remainder of HF patients.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Medicare will begin covering cardiac rehabilitation for patients with stable, chronic heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the new policy on Feb. 18.

About 5 million Americans have heart failure, but only half have an ejection fraction of less than 35%, Dr. Joseph A. Hill, chief of cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. Dr. Hill is chairman of the Heart Failure Society of America’s advocacy committee.

The HFSA, along with the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the American Heart Association (AHA), submitted a formal request to the CMS to add heart failure to the list of approved indications for coverage for cardiac rehabilitation. The agency began its analysis process in June 2013.

At that time, cardiac rehab was covered only for acute myocardial infarction within the preceding 12 months, coronary artery bypass surgery, current stable angina pectoris, heart valve repair or replacement, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or coronary stenting, and a heart or heart-lung transplant. Cardiac rehab includes physician prescribed exercise; risk factor modification, including education, counseling, and behavioral intervention; psychosocial assessment; and outcomes assessment.

Physician supervision is required for coverage.

The CMS said it had reconsidered coverage for some heart failure patients as a result of the HF-Action study, published in 2009 (JAMA 2009;301:1439-50). That study "provided the best evidence of benefit" in the HF patient group, but in particular for patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II-IV symptoms.

Specifically, the coverage is extended to "beneficiaries with stable, chronic heart failure defined as patients with left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and [NYHA] class II to IV symptoms despite being on optimal heart failure therapy for at least six weeks." The decision defines stable patients as those who have not had recent (within the past 6 weeks) or planned (within the past 6 months) major cardiovascular hospitalizations or procedures.

"We conclude that the evidence that supports the clinical benefits of the individual components of CR programs is sufficient to determine that participation in these programs improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HF," the CMS noted in its analysis.

"We’re very pleased," with the CMS decision, said Dr. Hill.

The ACC said it was still evaluating the decision. But Dr. M. Eugene Sherman, chairman of the ACC’s Advocacy Steering Committee, added that "we are pleased to see Medicare expand coverage of cardiac rehabilitation services, as the ACC requested, to a new patient population where medical and scientific literature demonstrates a medical benefit."

Dr. Hill said that the HFSA and others were hopeful that the CMS would eventually expand coverage of rehab to the remainder of HF patients.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Medicare will begin covering cardiac rehabilitation for patients with stable, chronic heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the new policy on Feb. 18.

About 5 million Americans have heart failure, but only half have an ejection fraction of less than 35%, Dr. Joseph A. Hill, chief of cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. Dr. Hill is chairman of the Heart Failure Society of America’s advocacy committee.

The HFSA, along with the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the American Heart Association (AHA), submitted a formal request to the CMS to add heart failure to the list of approved indications for coverage for cardiac rehabilitation. The agency began its analysis process in June 2013.

At that time, cardiac rehab was covered only for acute myocardial infarction within the preceding 12 months, coronary artery bypass surgery, current stable angina pectoris, heart valve repair or replacement, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or coronary stenting, and a heart or heart-lung transplant. Cardiac rehab includes physician prescribed exercise; risk factor modification, including education, counseling, and behavioral intervention; psychosocial assessment; and outcomes assessment.

Physician supervision is required for coverage.

The CMS said it had reconsidered coverage for some heart failure patients as a result of the HF-Action study, published in 2009 (JAMA 2009;301:1439-50). That study "provided the best evidence of benefit" in the HF patient group, but in particular for patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II-IV symptoms.

Specifically, the coverage is extended to "beneficiaries with stable, chronic heart failure defined as patients with left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and [NYHA] class II to IV symptoms despite being on optimal heart failure therapy for at least six weeks." The decision defines stable patients as those who have not had recent (within the past 6 weeks) or planned (within the past 6 months) major cardiovascular hospitalizations or procedures.

"We conclude that the evidence that supports the clinical benefits of the individual components of CR programs is sufficient to determine that participation in these programs improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HF," the CMS noted in its analysis.

"We’re very pleased," with the CMS decision, said Dr. Hill.

The ACC said it was still evaluating the decision. But Dr. M. Eugene Sherman, chairman of the ACC’s Advocacy Steering Committee, added that "we are pleased to see Medicare expand coverage of cardiac rehabilitation services, as the ACC requested, to a new patient population where medical and scientific literature demonstrates a medical benefit."

Dr. Hill said that the HFSA and others were hopeful that the CMS would eventually expand coverage of rehab to the remainder of HF patients.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Registry data reveal risk factors for lung retransplantation

ORLANDO – Age and increased lung allocation score are among factors associated with risk of lung retransplantation, according to an analysis of data from the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Of 24,194 consecutive patients who underwent lung transplantation between 1987 and 2012 and who were included in the nationwide registry, 941 (3.9%) underwent retransplantation. Age over 40 years, increased lung allocation score, increased percentage decline in forced ventilatory capacity (FVC), and readmission to the intensive care unit each were associated with retransplantation (odds ratios, 2.26, 0.98, 0.99, and 2.27, respectively), Dr. J. Awori Hayanga reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The current findings could allow for better prediction of graft failure and the need for retransplantation, and could help guide immunosuppression protocols and donor selection, he said. This is important, because although the overall volume of retransplantation remains less than 5%, the number of such procedures is steadily increasing, with up to 100 now performed each year.

"Following the introduction of the lung allocation score, the waiting time decreased, and the volume, perhaps predictably, increased by almost 60% with this increased emphasis on clinical acuity. The relative paucity of donors nevertheless engenders a considerable amount of scrutiny," Dr. Hayanga said. "Contention exists between the utilitarian view, where allocation prioritizes recipients in most need, versus the egalitarian view that seeks to provide equal opportunity to all those in need," he explained.

While this ethical argument is "tempered somewhat by steadily improving outcomes," retransplantations still remain inferior to primary transplantations, carrying a 30% overall increased risk of death. Prior to this study, the risk factors for retransplantation were poorly characterized in the literature.

The study also showed that donor factors associated with retransplantation included smoking history and body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2 (OR, 1.47 and 1.68, respectively). One transplant-related factor – increased graft ischemic time – was also associated with retransplantation (OR, 0.91), said Dr. Hayanga of the University of Pittsburgh.

Lung transplantation is a well-established therapeutic option for end-stage lung disease, but long-term outcomes are largely determined by chronic allograft failure – a diagnosis which constitutes "the most justifiable, evidence-driven indication for retransplantation," he said. Survival among patients who undergo retransplantation for this indication have nearly equivalent survival to those with a first transplant, he noted.

Conversely, "there are multiple observations in the literature of the dismal outcomes observed following retransplantation for primary graft failure and airway complications," he noted.