User login

VIDEO: Rivaroxaban plus aspirin halves ischemic strokes

LOS ANGELES – Combined treatment with a low dosage of the anticoagulant rivaroxaban plus aspirin cut the incidence of ischemic strokes nearly in half, compared with aspirin alone, in a multicenter, randomized trial of more than 27,000 patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

This dramatic reduction in ischemic strokes as well as in all-cause strokes by adding low-dose rivaroxaban(Xarelto) occurred without any significant increase in hemorrhagic strokes but with a small increase in total major bleeding events, such as gastrointestinal bleeds, Mike Sharma, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“There was a consistent effect across all strata of stroke risk. For patients who had a prior stroke, it’s pretty clear to use rivaroxaban plus aspirin because it had a big benefit” with no increase in intracranial hemorrhages, Dr. Sharma said in a video interview.

“We think these results will fundamentally change how we approach stroke prevention,” added Dr. Sharma, a stroke neurologist in the Population Health Research Institute of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The results he reported came from a secondary analysis of data collected in the COMPASS (Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Major Cardiovascular Events in Coronary or Peripheral Artery Disease) trial, which enrolled 27,395 patients with stable coronary or peripheral artery disease at 602 centers in 33 countries.

The primary outcome of the trial, reported in 2017, was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke during an average 23 months of follow-up, which occurred in 4.1% of patients treated with 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily plus 100 mg aspirin once daily, 4.9% of patients who received 5.0 mg rivaroxaban twice daily, and 5.4% in patients who received 100 mg aspirin daily, a statistically significant 24% relative risk reduction in the combined treatment group, compared with aspirin only. The rivaroxaban only–treated patients did not significantly differ from the control patients who received only aspirin (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30). The main results showed a 1.2% increase in the rate of major bleeds in patients treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin, compared with aspirin only, but the rate of nonfatal symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages was identical in the two treatment groups.

The new results Dr. Sharma reported at the conference focused on various measures of stroke. The rate of all strokes was 42% lower among the patients treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin, compared with the aspirin alone patients, and ischemic strokes were 49% lower with the dual therapy, compared with aspirin only. Both differences were statistically significant. In contrast, the rivaroxaban alone regimen did not significantly reduce all-cause strokes. It did significantly reduce ischemic strokes, compared with aspirin only, but it also significantly increased hemorrhagic strokes, compared with aspirin only, an adverse effect not caused by the combination of low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin.

Rivaroxaban plus aspirin surpassed aspirin alone for preventing both mild and severe strokes and for preventing strokes both in patients with a history of a prior stroke and in those who never had a prior stroke. The stroke reduction produced by rivaroxaban plus aspirin was greatest in the highest risk patients – those with a prior stroke. On the combined regimen, these patients had an average stroke incidence of 0.7% per year, compared with an annual 3.4% rate among the patients on aspirin only, a 2.7% absolute reduction by using rivaroxaban plus aspirin that translated into a number needed to treat of 37 patients with a history of stroke to prevent one new stroke per year.

The 2017 report of the main COMPASS results included a net clinical benefit analysis that factored together the primary endpoint events and major bleeding events. The net rate of all these events was 4.7% with rivaroxaban plus aspirin and 5.9% with aspirin only, a statistically significant 20% relative risk reduction for all adverse outcomes with dual therapy. This net clinical benefit suggests that adding rivaroxaban has a cost-effective benefit. Assessment of rivaroxaban’s cost benefit in COMPASS is in process, Dr. Sharma said.

Rivaroxaban received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in 2011 for preventing deep vein thrombosis and preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation at dosages higher than what was used in COMPASS. The approved rivaroxaban dosage for preventing deep vein thrombosis is 10 mg/day, and 20 mg/day for preventing stroke in atrial fibrillation patients. The 2.5-mg formulation of rivaroxaban that was given twice daily had the best safety and efficacy in COMPASS, but it is not available now on the U.S. market, although it is available in Europe. Johnson & Johnson, which markets rivaroxaban globally with Bayer, submitted an application to the FDA in December for marketing approval of the 2.5-mg formulation in twice-daily dosing for use as in the COMPASS trial.

COMPASS was sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets rivaroxaban in collaboration with Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Sharma has been a consultant or adviser to Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. ISC 2018, Abstract LB7.

LOS ANGELES – Combined treatment with a low dosage of the anticoagulant rivaroxaban plus aspirin cut the incidence of ischemic strokes nearly in half, compared with aspirin alone, in a multicenter, randomized trial of more than 27,000 patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

This dramatic reduction in ischemic strokes as well as in all-cause strokes by adding low-dose rivaroxaban(Xarelto) occurred without any significant increase in hemorrhagic strokes but with a small increase in total major bleeding events, such as gastrointestinal bleeds, Mike Sharma, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“There was a consistent effect across all strata of stroke risk. For patients who had a prior stroke, it’s pretty clear to use rivaroxaban plus aspirin because it had a big benefit” with no increase in intracranial hemorrhages, Dr. Sharma said in a video interview.

“We think these results will fundamentally change how we approach stroke prevention,” added Dr. Sharma, a stroke neurologist in the Population Health Research Institute of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The results he reported came from a secondary analysis of data collected in the COMPASS (Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Major Cardiovascular Events in Coronary or Peripheral Artery Disease) trial, which enrolled 27,395 patients with stable coronary or peripheral artery disease at 602 centers in 33 countries.

The primary outcome of the trial, reported in 2017, was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke during an average 23 months of follow-up, which occurred in 4.1% of patients treated with 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily plus 100 mg aspirin once daily, 4.9% of patients who received 5.0 mg rivaroxaban twice daily, and 5.4% in patients who received 100 mg aspirin daily, a statistically significant 24% relative risk reduction in the combined treatment group, compared with aspirin only. The rivaroxaban only–treated patients did not significantly differ from the control patients who received only aspirin (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30). The main results showed a 1.2% increase in the rate of major bleeds in patients treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin, compared with aspirin only, but the rate of nonfatal symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages was identical in the two treatment groups.

The new results Dr. Sharma reported at the conference focused on various measures of stroke. The rate of all strokes was 42% lower among the patients treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin, compared with the aspirin alone patients, and ischemic strokes were 49% lower with the dual therapy, compared with aspirin only. Both differences were statistically significant. In contrast, the rivaroxaban alone regimen did not significantly reduce all-cause strokes. It did significantly reduce ischemic strokes, compared with aspirin only, but it also significantly increased hemorrhagic strokes, compared with aspirin only, an adverse effect not caused by the combination of low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin.

Rivaroxaban plus aspirin surpassed aspirin alone for preventing both mild and severe strokes and for preventing strokes both in patients with a history of a prior stroke and in those who never had a prior stroke. The stroke reduction produced by rivaroxaban plus aspirin was greatest in the highest risk patients – those with a prior stroke. On the combined regimen, these patients had an average stroke incidence of 0.7% per year, compared with an annual 3.4% rate among the patients on aspirin only, a 2.7% absolute reduction by using rivaroxaban plus aspirin that translated into a number needed to treat of 37 patients with a history of stroke to prevent one new stroke per year.

The 2017 report of the main COMPASS results included a net clinical benefit analysis that factored together the primary endpoint events and major bleeding events. The net rate of all these events was 4.7% with rivaroxaban plus aspirin and 5.9% with aspirin only, a statistically significant 20% relative risk reduction for all adverse outcomes with dual therapy. This net clinical benefit suggests that adding rivaroxaban has a cost-effective benefit. Assessment of rivaroxaban’s cost benefit in COMPASS is in process, Dr. Sharma said.

Rivaroxaban received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in 2011 for preventing deep vein thrombosis and preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation at dosages higher than what was used in COMPASS. The approved rivaroxaban dosage for preventing deep vein thrombosis is 10 mg/day, and 20 mg/day for preventing stroke in atrial fibrillation patients. The 2.5-mg formulation of rivaroxaban that was given twice daily had the best safety and efficacy in COMPASS, but it is not available now on the U.S. market, although it is available in Europe. Johnson & Johnson, which markets rivaroxaban globally with Bayer, submitted an application to the FDA in December for marketing approval of the 2.5-mg formulation in twice-daily dosing for use as in the COMPASS trial.

COMPASS was sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets rivaroxaban in collaboration with Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Sharma has been a consultant or adviser to Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. ISC 2018, Abstract LB7.

LOS ANGELES – Combined treatment with a low dosage of the anticoagulant rivaroxaban plus aspirin cut the incidence of ischemic strokes nearly in half, compared with aspirin alone, in a multicenter, randomized trial of more than 27,000 patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

This dramatic reduction in ischemic strokes as well as in all-cause strokes by adding low-dose rivaroxaban(Xarelto) occurred without any significant increase in hemorrhagic strokes but with a small increase in total major bleeding events, such as gastrointestinal bleeds, Mike Sharma, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“There was a consistent effect across all strata of stroke risk. For patients who had a prior stroke, it’s pretty clear to use rivaroxaban plus aspirin because it had a big benefit” with no increase in intracranial hemorrhages, Dr. Sharma said in a video interview.

“We think these results will fundamentally change how we approach stroke prevention,” added Dr. Sharma, a stroke neurologist in the Population Health Research Institute of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The results he reported came from a secondary analysis of data collected in the COMPASS (Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Major Cardiovascular Events in Coronary or Peripheral Artery Disease) trial, which enrolled 27,395 patients with stable coronary or peripheral artery disease at 602 centers in 33 countries.

The primary outcome of the trial, reported in 2017, was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke during an average 23 months of follow-up, which occurred in 4.1% of patients treated with 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily plus 100 mg aspirin once daily, 4.9% of patients who received 5.0 mg rivaroxaban twice daily, and 5.4% in patients who received 100 mg aspirin daily, a statistically significant 24% relative risk reduction in the combined treatment group, compared with aspirin only. The rivaroxaban only–treated patients did not significantly differ from the control patients who received only aspirin (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30). The main results showed a 1.2% increase in the rate of major bleeds in patients treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin, compared with aspirin only, but the rate of nonfatal symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages was identical in the two treatment groups.

The new results Dr. Sharma reported at the conference focused on various measures of stroke. The rate of all strokes was 42% lower among the patients treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin, compared with the aspirin alone patients, and ischemic strokes were 49% lower with the dual therapy, compared with aspirin only. Both differences were statistically significant. In contrast, the rivaroxaban alone regimen did not significantly reduce all-cause strokes. It did significantly reduce ischemic strokes, compared with aspirin only, but it also significantly increased hemorrhagic strokes, compared with aspirin only, an adverse effect not caused by the combination of low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin.

Rivaroxaban plus aspirin surpassed aspirin alone for preventing both mild and severe strokes and for preventing strokes both in patients with a history of a prior stroke and in those who never had a prior stroke. The stroke reduction produced by rivaroxaban plus aspirin was greatest in the highest risk patients – those with a prior stroke. On the combined regimen, these patients had an average stroke incidence of 0.7% per year, compared with an annual 3.4% rate among the patients on aspirin only, a 2.7% absolute reduction by using rivaroxaban plus aspirin that translated into a number needed to treat of 37 patients with a history of stroke to prevent one new stroke per year.

The 2017 report of the main COMPASS results included a net clinical benefit analysis that factored together the primary endpoint events and major bleeding events. The net rate of all these events was 4.7% with rivaroxaban plus aspirin and 5.9% with aspirin only, a statistically significant 20% relative risk reduction for all adverse outcomes with dual therapy. This net clinical benefit suggests that adding rivaroxaban has a cost-effective benefit. Assessment of rivaroxaban’s cost benefit in COMPASS is in process, Dr. Sharma said.

Rivaroxaban received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in 2011 for preventing deep vein thrombosis and preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation at dosages higher than what was used in COMPASS. The approved rivaroxaban dosage for preventing deep vein thrombosis is 10 mg/day, and 20 mg/day for preventing stroke in atrial fibrillation patients. The 2.5-mg formulation of rivaroxaban that was given twice daily had the best safety and efficacy in COMPASS, but it is not available now on the U.S. market, although it is available in Europe. Johnson & Johnson, which markets rivaroxaban globally with Bayer, submitted an application to the FDA in December for marketing approval of the 2.5-mg formulation in twice-daily dosing for use as in the COMPASS trial.

COMPASS was sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets rivaroxaban in collaboration with Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Sharma has been a consultant or adviser to Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. ISC 2018, Abstract LB7.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2018

Key clinical point: Rivaroxaban plus aspirin cuts strokes in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Major finding: Rivaroxaban plus aspirin cut the rate of ischemic strokes by 49%, compared with aspirin only.

Study details: Secondary analysis from the COMPASS trial, a multicenter, randomized trial with 27,395 patients.

Disclosures: COMPASS was sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets rivaroxaban in collaboration with Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Sharma has been a consultant or adviser to Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

Source: Sharma M et al. ISC 2018, Abstract LB7.

Asymptomatic carotid in-stent restenosis? Think medical management

CHICAGO – with a carotid in-stent restenosis in excess of 70%, Jayer Chung, MD, asserted at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

That, in his view, makes medical management the clear preferred strategy.

A growing body of evidence, mainly from nested cohorts within randomized controlled trials, indicates that the late ipsilateral stroke rate associated with post–carotid endarterectomy restenosis (CEA) is much higher than that for carotid in-stent restenosis (C-ISR). In a recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials, the difference in risk was more than 10-fold, with a 9.2% stroke rate at a mean of 37 months of follow-up in patients with post-CEA restenosis, compared with a 0.8% rate with 50 months of follow-up in patients with C-ISR (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017 Jun;53[6]:766-75).

“These pathologies behave very, very differently,” Dr. Chung observed. “The C-ISR lesions tend to be less embologenic.”

C-ISR is an uncommon event. Extrapolating from the landmark CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial) and other randomized trials, about 6% of patients who undergo percutaneous carotid stenting will be develop C-ISR within 2 years. But since the proportion of all carotid revascularizations that are done by carotid stent angioplasty has steadily increased over the past 15 years as the frequency of CEA has dropped, C-ISR is a problem that vascular specialists will continue to encounter on a regular basis.

Symptomatic C-ISR warrants reintervention; broad agreement exists on that. But there is a paucity of data to guide treatment decisions regarding asymptomatic yet angiographically severe C-ISR. Indeed, Dr. Chung was lead author of the only retrospective study of the natural history of untreated C-ISR, as opposed to carefully selected cohorts from randomized trials involving highly experienced operators. This study was a retrospective review of 59 patients with 75 C-ISRs of at least 50% seen at a single Veterans Affairs medical center over a 13-year period. Three-quarters of the ISRs were asymptomatic.

Forty of the 79 C-ISRs underwent percutaneous intervention at the physician’s discretion. Those patients did not differ from the observation-only group in age, comorbid conditions, type of original stent, or clopidogrel use. Reintervention was safe: There was one stent thrombosis resulting in stroke and death within 30 days in the reintervention group and no 30-day strokes in the observation-only group. During a mean 2.6 years of follow-up, the composite rate of death, stroke, or MI was low and not statistically significantly different between the two groups. Indeed, during up to 13 years of follow-up only one patient with untreated C-ISR experienced an ipsilateral stroke, as did two patients in the percutaneous intervention group (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Nov;64[5]:1286-94).

Dr. Chung does the math

According to data from the National Inpatient Sample, vascular surgeons do an average of 15 carotid angioplasty and stenting procedures per year. If 6% of those stents develop in-stent restenosis, and with a number needed to treat with revascularization of 25 to prevent 1 stroke, Dr. Chung estimated that hypothetically it would take the typical vascular surgeon 27 years to prevent one stroke due to C-ISR.

“That’s a very long time to prevent one stroke, in my opinion,” he said.

How his study has affected his own practice

Dr. Chung now intervenes only for symptomatic C-ISRs, and only after an affected patient is on optimal medical therapy, including a statin and dual-antiplatelet therapy.

“I try to do an open procedure if possible, especially if the restenosis is above C-2. The ones I tend to do percutaneously are the post-irradiation stenoses or those with excessive scarring, and I use a cerebral protection device,” the surgeon explained.

He emphasized, however, that the final word on the appropriate management of C-ISRs isn’t in yet. A standardized definition of C-ISR is needed, as are multicenter prospective registries of medically managed patients as well as those undergoing various forms of reintervention. And a pathologic study is warranted to confirm the hypothesis that the histopathology of post-CEA and post-stent restenosis – and hence the natural history – is markedly different.

Dr. Chung reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

CHICAGO – with a carotid in-stent restenosis in excess of 70%, Jayer Chung, MD, asserted at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

That, in his view, makes medical management the clear preferred strategy.

A growing body of evidence, mainly from nested cohorts within randomized controlled trials, indicates that the late ipsilateral stroke rate associated with post–carotid endarterectomy restenosis (CEA) is much higher than that for carotid in-stent restenosis (C-ISR). In a recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials, the difference in risk was more than 10-fold, with a 9.2% stroke rate at a mean of 37 months of follow-up in patients with post-CEA restenosis, compared with a 0.8% rate with 50 months of follow-up in patients with C-ISR (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017 Jun;53[6]:766-75).

“These pathologies behave very, very differently,” Dr. Chung observed. “The C-ISR lesions tend to be less embologenic.”

C-ISR is an uncommon event. Extrapolating from the landmark CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial) and other randomized trials, about 6% of patients who undergo percutaneous carotid stenting will be develop C-ISR within 2 years. But since the proportion of all carotid revascularizations that are done by carotid stent angioplasty has steadily increased over the past 15 years as the frequency of CEA has dropped, C-ISR is a problem that vascular specialists will continue to encounter on a regular basis.

Symptomatic C-ISR warrants reintervention; broad agreement exists on that. But there is a paucity of data to guide treatment decisions regarding asymptomatic yet angiographically severe C-ISR. Indeed, Dr. Chung was lead author of the only retrospective study of the natural history of untreated C-ISR, as opposed to carefully selected cohorts from randomized trials involving highly experienced operators. This study was a retrospective review of 59 patients with 75 C-ISRs of at least 50% seen at a single Veterans Affairs medical center over a 13-year period. Three-quarters of the ISRs were asymptomatic.

Forty of the 79 C-ISRs underwent percutaneous intervention at the physician’s discretion. Those patients did not differ from the observation-only group in age, comorbid conditions, type of original stent, or clopidogrel use. Reintervention was safe: There was one stent thrombosis resulting in stroke and death within 30 days in the reintervention group and no 30-day strokes in the observation-only group. During a mean 2.6 years of follow-up, the composite rate of death, stroke, or MI was low and not statistically significantly different between the two groups. Indeed, during up to 13 years of follow-up only one patient with untreated C-ISR experienced an ipsilateral stroke, as did two patients in the percutaneous intervention group (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Nov;64[5]:1286-94).

Dr. Chung does the math

According to data from the National Inpatient Sample, vascular surgeons do an average of 15 carotid angioplasty and stenting procedures per year. If 6% of those stents develop in-stent restenosis, and with a number needed to treat with revascularization of 25 to prevent 1 stroke, Dr. Chung estimated that hypothetically it would take the typical vascular surgeon 27 years to prevent one stroke due to C-ISR.

“That’s a very long time to prevent one stroke, in my opinion,” he said.

How his study has affected his own practice

Dr. Chung now intervenes only for symptomatic C-ISRs, and only after an affected patient is on optimal medical therapy, including a statin and dual-antiplatelet therapy.

“I try to do an open procedure if possible, especially if the restenosis is above C-2. The ones I tend to do percutaneously are the post-irradiation stenoses or those with excessive scarring, and I use a cerebral protection device,” the surgeon explained.

He emphasized, however, that the final word on the appropriate management of C-ISRs isn’t in yet. A standardized definition of C-ISR is needed, as are multicenter prospective registries of medically managed patients as well as those undergoing various forms of reintervention. And a pathologic study is warranted to confirm the hypothesis that the histopathology of post-CEA and post-stent restenosis – and hence the natural history – is markedly different.

Dr. Chung reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

CHICAGO – with a carotid in-stent restenosis in excess of 70%, Jayer Chung, MD, asserted at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

That, in his view, makes medical management the clear preferred strategy.

A growing body of evidence, mainly from nested cohorts within randomized controlled trials, indicates that the late ipsilateral stroke rate associated with post–carotid endarterectomy restenosis (CEA) is much higher than that for carotid in-stent restenosis (C-ISR). In a recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials, the difference in risk was more than 10-fold, with a 9.2% stroke rate at a mean of 37 months of follow-up in patients with post-CEA restenosis, compared with a 0.8% rate with 50 months of follow-up in patients with C-ISR (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017 Jun;53[6]:766-75).

“These pathologies behave very, very differently,” Dr. Chung observed. “The C-ISR lesions tend to be less embologenic.”

C-ISR is an uncommon event. Extrapolating from the landmark CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial) and other randomized trials, about 6% of patients who undergo percutaneous carotid stenting will be develop C-ISR within 2 years. But since the proportion of all carotid revascularizations that are done by carotid stent angioplasty has steadily increased over the past 15 years as the frequency of CEA has dropped, C-ISR is a problem that vascular specialists will continue to encounter on a regular basis.

Symptomatic C-ISR warrants reintervention; broad agreement exists on that. But there is a paucity of data to guide treatment decisions regarding asymptomatic yet angiographically severe C-ISR. Indeed, Dr. Chung was lead author of the only retrospective study of the natural history of untreated C-ISR, as opposed to carefully selected cohorts from randomized trials involving highly experienced operators. This study was a retrospective review of 59 patients with 75 C-ISRs of at least 50% seen at a single Veterans Affairs medical center over a 13-year period. Three-quarters of the ISRs were asymptomatic.

Forty of the 79 C-ISRs underwent percutaneous intervention at the physician’s discretion. Those patients did not differ from the observation-only group in age, comorbid conditions, type of original stent, or clopidogrel use. Reintervention was safe: There was one stent thrombosis resulting in stroke and death within 30 days in the reintervention group and no 30-day strokes in the observation-only group. During a mean 2.6 years of follow-up, the composite rate of death, stroke, or MI was low and not statistically significantly different between the two groups. Indeed, during up to 13 years of follow-up only one patient with untreated C-ISR experienced an ipsilateral stroke, as did two patients in the percutaneous intervention group (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Nov;64[5]:1286-94).

Dr. Chung does the math

According to data from the National Inpatient Sample, vascular surgeons do an average of 15 carotid angioplasty and stenting procedures per year. If 6% of those stents develop in-stent restenosis, and with a number needed to treat with revascularization of 25 to prevent 1 stroke, Dr. Chung estimated that hypothetically it would take the typical vascular surgeon 27 years to prevent one stroke due to C-ISR.

“That’s a very long time to prevent one stroke, in my opinion,” he said.

How his study has affected his own practice

Dr. Chung now intervenes only for symptomatic C-ISRs, and only after an affected patient is on optimal medical therapy, including a statin and dual-antiplatelet therapy.

“I try to do an open procedure if possible, especially if the restenosis is above C-2. The ones I tend to do percutaneously are the post-irradiation stenoses or those with excessive scarring, and I use a cerebral protection device,” the surgeon explained.

He emphasized, however, that the final word on the appropriate management of C-ISRs isn’t in yet. A standardized definition of C-ISR is needed, as are multicenter prospective registries of medically managed patients as well as those undergoing various forms of reintervention. And a pathologic study is warranted to confirm the hypothesis that the histopathology of post-CEA and post-stent restenosis – and hence the natural history – is markedly different.

Dr. Chung reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Carotid stenting isn’t safer than endarterectomy with contralateral carotid occlusion

CHICAGO – Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) isn’t associated with a lower 30-day stroke risk than carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for revascularization of the internal carotid artery in patients with contralateral carotid occlusion, Leila Mureebe, MD, said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University, Chicago.

The reported prevalence of contralateral carotid occlusion (CCO) in patients undergoing revascularization for carotid artery disease is 3%-15%. Of late Dr. Mureebe has been particularly interested in two questions regarding CCO in patients undergoing revascularization of their other carotid artery: Is CCO truly a risk factor for perioperative stroke? And if so, can this risk be mitigated by the choice of procedure?

To answer the first question, Dr. Mureebe and her coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of eight representative studies published between 1994 and 2012; they determined that CCO in patients undergoing CEA was indeed associated with a near doubling of perioperative stroke risk, compared with that of patients without CCO.

In order to learn whether CAS mitigates this risk, she and her coworkers analyzed the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for the period between 2011 and 2015, in which they identified 15,619 fully documented CEA and 496 CAS.

“This NSQIP data is not just academic medical centers or big centers. I think it’s a pretty good look at what’s actually being done in the real world today,” according to Dr. Mureebe.

The analysis showed that CCO has already had an effect on practice. A higher proportion of patients with CCO now undergo stenting as opposed to endarterectomy. Only 4.6% of all CEAs were done in patients with CCO, compared with 11.5% of CAS procedures. Moreover, the majority of revascularizations in the setting of CCO were performed in patients with asymptomatic disease: 57% of all CEA and 53% of the CAS. The CAS finding was surprising given that reimbursement for CAS is at present limited to symptomatic patients at high surgical risk who have a significant internal carotid artery stenosis, Dr. Mureebe observed.

The 30-day stroke rate in patients with CCO was 3.22% after CEA and 1.75% after CAS, a difference that wasn’t statistically significant. In patients without CCO, the stroke rate was 2.03% after CEA and 2.96% after CAS.

Next, the investigators analyzed differences in stroke rates according to symptom status. Among patients with CCO and preprocedural transient ischemic attack, stroke, or transient monocular blindness who underwent CEA, the 30-day stroke risk associated with CEA was 5.2%, a significantly higher rate than the 2.1% rate seen in patients without symptoms. The number of patients with CCO undergoing CAS was too small to draw conclusions regarding possible differences in stroke risk based upon symptom status.

In the NSQIP database, patients with CCO had higher prevalences of heart failure, hypertension, and smoking. For this reason, Dr. Mureebe said she suspects CCO is a surrogate for greater atherosclerotic disease burden and not an independent risk factor for periprocedural stroke. If future studies of the minimally invasive transcarotid artery revascularization procedure also show a higher rate of bad outcomes in patients with CCO, that would further support the hypothesis that CCO is a marker of higher atherosclerotic disease burden, Dr. Mureebe said.

A limitation of the NSQIP database is that it captures only those CAS cases done in operating rooms. “Maybe patients undergoing CAS in the OR are different from those undergoing CAS in a radiologic suite or cath lab,” she noted.

Dr. Mureebe reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SOURCE: Mureebe L. 42nd Annual Northwestern Vascular Symposium.

CHICAGO – Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) isn’t associated with a lower 30-day stroke risk than carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for revascularization of the internal carotid artery in patients with contralateral carotid occlusion, Leila Mureebe, MD, said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University, Chicago.

The reported prevalence of contralateral carotid occlusion (CCO) in patients undergoing revascularization for carotid artery disease is 3%-15%. Of late Dr. Mureebe has been particularly interested in two questions regarding CCO in patients undergoing revascularization of their other carotid artery: Is CCO truly a risk factor for perioperative stroke? And if so, can this risk be mitigated by the choice of procedure?

To answer the first question, Dr. Mureebe and her coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of eight representative studies published between 1994 and 2012; they determined that CCO in patients undergoing CEA was indeed associated with a near doubling of perioperative stroke risk, compared with that of patients without CCO.

In order to learn whether CAS mitigates this risk, she and her coworkers analyzed the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for the period between 2011 and 2015, in which they identified 15,619 fully documented CEA and 496 CAS.

“This NSQIP data is not just academic medical centers or big centers. I think it’s a pretty good look at what’s actually being done in the real world today,” according to Dr. Mureebe.

The analysis showed that CCO has already had an effect on practice. A higher proportion of patients with CCO now undergo stenting as opposed to endarterectomy. Only 4.6% of all CEAs were done in patients with CCO, compared with 11.5% of CAS procedures. Moreover, the majority of revascularizations in the setting of CCO were performed in patients with asymptomatic disease: 57% of all CEA and 53% of the CAS. The CAS finding was surprising given that reimbursement for CAS is at present limited to symptomatic patients at high surgical risk who have a significant internal carotid artery stenosis, Dr. Mureebe observed.

The 30-day stroke rate in patients with CCO was 3.22% after CEA and 1.75% after CAS, a difference that wasn’t statistically significant. In patients without CCO, the stroke rate was 2.03% after CEA and 2.96% after CAS.

Next, the investigators analyzed differences in stroke rates according to symptom status. Among patients with CCO and preprocedural transient ischemic attack, stroke, or transient monocular blindness who underwent CEA, the 30-day stroke risk associated with CEA was 5.2%, a significantly higher rate than the 2.1% rate seen in patients without symptoms. The number of patients with CCO undergoing CAS was too small to draw conclusions regarding possible differences in stroke risk based upon symptom status.

In the NSQIP database, patients with CCO had higher prevalences of heart failure, hypertension, and smoking. For this reason, Dr. Mureebe said she suspects CCO is a surrogate for greater atherosclerotic disease burden and not an independent risk factor for periprocedural stroke. If future studies of the minimally invasive transcarotid artery revascularization procedure also show a higher rate of bad outcomes in patients with CCO, that would further support the hypothesis that CCO is a marker of higher atherosclerotic disease burden, Dr. Mureebe said.

A limitation of the NSQIP database is that it captures only those CAS cases done in operating rooms. “Maybe patients undergoing CAS in the OR are different from those undergoing CAS in a radiologic suite or cath lab,” she noted.

Dr. Mureebe reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SOURCE: Mureebe L. 42nd Annual Northwestern Vascular Symposium.

CHICAGO – Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) isn’t associated with a lower 30-day stroke risk than carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for revascularization of the internal carotid artery in patients with contralateral carotid occlusion, Leila Mureebe, MD, said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University, Chicago.

The reported prevalence of contralateral carotid occlusion (CCO) in patients undergoing revascularization for carotid artery disease is 3%-15%. Of late Dr. Mureebe has been particularly interested in two questions regarding CCO in patients undergoing revascularization of their other carotid artery: Is CCO truly a risk factor for perioperative stroke? And if so, can this risk be mitigated by the choice of procedure?

To answer the first question, Dr. Mureebe and her coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of eight representative studies published between 1994 and 2012; they determined that CCO in patients undergoing CEA was indeed associated with a near doubling of perioperative stroke risk, compared with that of patients without CCO.

In order to learn whether CAS mitigates this risk, she and her coworkers analyzed the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for the period between 2011 and 2015, in which they identified 15,619 fully documented CEA and 496 CAS.

“This NSQIP data is not just academic medical centers or big centers. I think it’s a pretty good look at what’s actually being done in the real world today,” according to Dr. Mureebe.

The analysis showed that CCO has already had an effect on practice. A higher proportion of patients with CCO now undergo stenting as opposed to endarterectomy. Only 4.6% of all CEAs were done in patients with CCO, compared with 11.5% of CAS procedures. Moreover, the majority of revascularizations in the setting of CCO were performed in patients with asymptomatic disease: 57% of all CEA and 53% of the CAS. The CAS finding was surprising given that reimbursement for CAS is at present limited to symptomatic patients at high surgical risk who have a significant internal carotid artery stenosis, Dr. Mureebe observed.

The 30-day stroke rate in patients with CCO was 3.22% after CEA and 1.75% after CAS, a difference that wasn’t statistically significant. In patients without CCO, the stroke rate was 2.03% after CEA and 2.96% after CAS.

Next, the investigators analyzed differences in stroke rates according to symptom status. Among patients with CCO and preprocedural transient ischemic attack, stroke, or transient monocular blindness who underwent CEA, the 30-day stroke risk associated with CEA was 5.2%, a significantly higher rate than the 2.1% rate seen in patients without symptoms. The number of patients with CCO undergoing CAS was too small to draw conclusions regarding possible differences in stroke risk based upon symptom status.

In the NSQIP database, patients with CCO had higher prevalences of heart failure, hypertension, and smoking. For this reason, Dr. Mureebe said she suspects CCO is a surrogate for greater atherosclerotic disease burden and not an independent risk factor for periprocedural stroke. If future studies of the minimally invasive transcarotid artery revascularization procedure also show a higher rate of bad outcomes in patients with CCO, that would further support the hypothesis that CCO is a marker of higher atherosclerotic disease burden, Dr. Mureebe said.

A limitation of the NSQIP database is that it captures only those CAS cases done in operating rooms. “Maybe patients undergoing CAS in the OR are different from those undergoing CAS in a radiologic suite or cath lab,” she noted.

Dr. Mureebe reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SOURCE: Mureebe L. 42nd Annual Northwestern Vascular Symposium.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Watchman device PREVAILs for stroke prevention

DENVER – Left atrial appendage closure using the Watchman device is as effective as warfarin in preventing strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation, but the strokes in Watchman recipients are 55% less likely to be disabling, according to a meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes in the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF randomized trials.

The device therapy showed additional advantages over warfarin: significantly reduced risks of mortality, non–procedure-related major bleeding, and hemorrhagic stroke, Saibal Kar, MD, reported in presenting the results of the meta-analysis at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual educational meeting.

“We have prevailed,” he declared, referring to device safety concerns that arose early on and have since been laid to rest.

The patient-level meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes included 1,114 patients with atrial fibrillation who were randomized 2:1 to the Watchman device or warfarin, with 4,343 patient-years of follow-up. This was a fairly high–stroke risk population, with CHA2DS2-VASc scores in the 3.6-3.9 range, and 40% of patients aged 75 years or more. At baseline, 23% of subjects had a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.

At 5 years’ follow-up, the composite endpoint of all stroke or systemic embolism was the same in the two study arms. However, the rate of hemorrhagic stroke was 80% lower in the Watchman group, the risk of disabling or fatal stroke was reduced by 55%, the rate of cardiovascular or unexplained death was 41% lower, all-cause mortality was reduced by 27%, and postprocedure major bleeding was 52% less frequent in the device therapy group. All of these differences achieved statistical significance, the cardiologist reported at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

On the downside, the rate of ischemic stroke trended higher in the Watchman group, although the 71% increase in relative risk didn’t achieve statistical significance (P = .08). Dr. Kar asserted that this unhappy trend was a statistical fluke resulting from a low number of events and an implausibly low ischemic stroke rate of 0.73% per year in the warfarin group.

“This is the lowest rate of ischemic stroke in any study of warfarin. In fact, if this was the ischemic stroke rate in any of the NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant] studies, none of those drugs would actually have been approved. Why did we get such an implausibly low ischemic stroke rate? It’s a function of lower numbers and larger confidence intervals,” he said.

Gregg W. Stone, MD, who moderated the discussion panel at the late-breaking clinical trial session, advised Dr. Kar to be less defensive about the ischemic stroke findings.

“I think we have to be a little less apologetic for the great outcomes in the warfarin arm in PREVAIL. We do these randomized trials, and we get what we get,” said Dr. Stone, professor of medicine at Columbia University in New York.

Stephen G. Ellis, MD, said he was particularly impressed with the reduced rate of disabling stroke in the Watchman group.

“Severity of stroke is important. I hadn’t seen that data before,” commented Dr. Ellis, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic. “The overall message, I think, is that for the patients who would have been candidates to be enrolled in these trials, the device seems to be quite worthwhile. I take note of the overall benefit in terms of cardiovascular death and all-cause death.”

Robert J. Sommer, MD, said that in patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc scores and previous bleeding on oral anticoagulants, the new data show that the Watchman “is a no-brainer. The patients all want it, the physicians all want it. It’s a very easy decision to make.”

“But you get into other groups who may potentially be interested in the device – particularly the younger patients who are very active and don’t want to be on anticoagulation – I think the ischemic stroke rate in the device arm trending to be higher is a problem for them. And it’s certainly going to be a problem for their physicians. But as we go on, I think with further studies we’ll see expanded indications. Patients with CAD who potentially would need triple therapy – that’s a nice population to study in this area. We’ll also be seeing data on other devices that may have different ischemic stroke rates,” said Dr. Sommer, director of invasive adult congenital heart disease at Columbia University Medical Center.

“I find this data extraordinarily helpful as I think about my conversations with patients about stroke prevention,” said Brian K. Whisenant, MD, medical director of structural heart disease at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City.

“I tell them we think of oral anticoagulants as first-line therapy based on a stroke rate of 1% per year or less in most datasets. The data for the Watchman device has been very consistent in that we have a stroke rate that’s a little bit higher, at 1.3%-1.8% per year. And we have extensive data for predicting the stroke rate in the absence of oral anticoagulation: In most of our patients, that rate is in excess of 5% per year. So while the Watchman device may not provide the absolute reduction in ischemic stroke rate that oral anticoagulants do, a stroke rate of less than 2% is a whole lot better than no therapy for many of these patients,” the cardiologist said.

Martin B. Leon, MD, opined that the ischemic stroke data cannot be explained away. But he added that the totality of the meta-analysis data gives him confidence that this is the appropriate treatment in these patients.

“It does leave open the question of whether we can do better with ischemic strokes. Some people are suggesting that maybe adjunctive pharmacotherapy – perhaps a low-dose NOAC – may be a reasonable option in some patients to get even better results. That’s something I believe is open for discussion,” said Dr. Leon, professor of medicine at Columbia University and director of the Center for Interventional Vascular Therapy at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Dr. Stone summed up: “There’s uniformity among the panel that there may be a slightly lower ischemic stroke rate with oral anticoagulation, and the NOACs probably provide some additional benefit, with an additional 50% reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, compared to warfarin. But that being said, I believe that left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman is the viable and now clearly safe approach for patients with any sort of contraindication or strong desire to avoid oral anticoagulation.”

The PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials and meta-analysis were sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kar reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Abbott Vascular.

Simultaneously with Dr. Kar’s presentation at TCT 2017, the findings were published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

SOURCE: Reddy VY et al. TCT 2017; J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 4. pii:S0735-1097(17)41187-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.021.

DENVER – Left atrial appendage closure using the Watchman device is as effective as warfarin in preventing strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation, but the strokes in Watchman recipients are 55% less likely to be disabling, according to a meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes in the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF randomized trials.

The device therapy showed additional advantages over warfarin: significantly reduced risks of mortality, non–procedure-related major bleeding, and hemorrhagic stroke, Saibal Kar, MD, reported in presenting the results of the meta-analysis at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual educational meeting.

“We have prevailed,” he declared, referring to device safety concerns that arose early on and have since been laid to rest.

The patient-level meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes included 1,114 patients with atrial fibrillation who were randomized 2:1 to the Watchman device or warfarin, with 4,343 patient-years of follow-up. This was a fairly high–stroke risk population, with CHA2DS2-VASc scores in the 3.6-3.9 range, and 40% of patients aged 75 years or more. At baseline, 23% of subjects had a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.

At 5 years’ follow-up, the composite endpoint of all stroke or systemic embolism was the same in the two study arms. However, the rate of hemorrhagic stroke was 80% lower in the Watchman group, the risk of disabling or fatal stroke was reduced by 55%, the rate of cardiovascular or unexplained death was 41% lower, all-cause mortality was reduced by 27%, and postprocedure major bleeding was 52% less frequent in the device therapy group. All of these differences achieved statistical significance, the cardiologist reported at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

On the downside, the rate of ischemic stroke trended higher in the Watchman group, although the 71% increase in relative risk didn’t achieve statistical significance (P = .08). Dr. Kar asserted that this unhappy trend was a statistical fluke resulting from a low number of events and an implausibly low ischemic stroke rate of 0.73% per year in the warfarin group.

“This is the lowest rate of ischemic stroke in any study of warfarin. In fact, if this was the ischemic stroke rate in any of the NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant] studies, none of those drugs would actually have been approved. Why did we get such an implausibly low ischemic stroke rate? It’s a function of lower numbers and larger confidence intervals,” he said.

Gregg W. Stone, MD, who moderated the discussion panel at the late-breaking clinical trial session, advised Dr. Kar to be less defensive about the ischemic stroke findings.

“I think we have to be a little less apologetic for the great outcomes in the warfarin arm in PREVAIL. We do these randomized trials, and we get what we get,” said Dr. Stone, professor of medicine at Columbia University in New York.

Stephen G. Ellis, MD, said he was particularly impressed with the reduced rate of disabling stroke in the Watchman group.

“Severity of stroke is important. I hadn’t seen that data before,” commented Dr. Ellis, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic. “The overall message, I think, is that for the patients who would have been candidates to be enrolled in these trials, the device seems to be quite worthwhile. I take note of the overall benefit in terms of cardiovascular death and all-cause death.”

Robert J. Sommer, MD, said that in patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc scores and previous bleeding on oral anticoagulants, the new data show that the Watchman “is a no-brainer. The patients all want it, the physicians all want it. It’s a very easy decision to make.”

“But you get into other groups who may potentially be interested in the device – particularly the younger patients who are very active and don’t want to be on anticoagulation – I think the ischemic stroke rate in the device arm trending to be higher is a problem for them. And it’s certainly going to be a problem for their physicians. But as we go on, I think with further studies we’ll see expanded indications. Patients with CAD who potentially would need triple therapy – that’s a nice population to study in this area. We’ll also be seeing data on other devices that may have different ischemic stroke rates,” said Dr. Sommer, director of invasive adult congenital heart disease at Columbia University Medical Center.

“I find this data extraordinarily helpful as I think about my conversations with patients about stroke prevention,” said Brian K. Whisenant, MD, medical director of structural heart disease at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City.

“I tell them we think of oral anticoagulants as first-line therapy based on a stroke rate of 1% per year or less in most datasets. The data for the Watchman device has been very consistent in that we have a stroke rate that’s a little bit higher, at 1.3%-1.8% per year. And we have extensive data for predicting the stroke rate in the absence of oral anticoagulation: In most of our patients, that rate is in excess of 5% per year. So while the Watchman device may not provide the absolute reduction in ischemic stroke rate that oral anticoagulants do, a stroke rate of less than 2% is a whole lot better than no therapy for many of these patients,” the cardiologist said.

Martin B. Leon, MD, opined that the ischemic stroke data cannot be explained away. But he added that the totality of the meta-analysis data gives him confidence that this is the appropriate treatment in these patients.

“It does leave open the question of whether we can do better with ischemic strokes. Some people are suggesting that maybe adjunctive pharmacotherapy – perhaps a low-dose NOAC – may be a reasonable option in some patients to get even better results. That’s something I believe is open for discussion,” said Dr. Leon, professor of medicine at Columbia University and director of the Center for Interventional Vascular Therapy at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Dr. Stone summed up: “There’s uniformity among the panel that there may be a slightly lower ischemic stroke rate with oral anticoagulation, and the NOACs probably provide some additional benefit, with an additional 50% reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, compared to warfarin. But that being said, I believe that left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman is the viable and now clearly safe approach for patients with any sort of contraindication or strong desire to avoid oral anticoagulation.”

The PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials and meta-analysis were sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kar reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Abbott Vascular.

Simultaneously with Dr. Kar’s presentation at TCT 2017, the findings were published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

SOURCE: Reddy VY et al. TCT 2017; J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 4. pii:S0735-1097(17)41187-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.021.

DENVER – Left atrial appendage closure using the Watchman device is as effective as warfarin in preventing strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation, but the strokes in Watchman recipients are 55% less likely to be disabling, according to a meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes in the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF randomized trials.

The device therapy showed additional advantages over warfarin: significantly reduced risks of mortality, non–procedure-related major bleeding, and hemorrhagic stroke, Saibal Kar, MD, reported in presenting the results of the meta-analysis at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual educational meeting.

“We have prevailed,” he declared, referring to device safety concerns that arose early on and have since been laid to rest.

The patient-level meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes included 1,114 patients with atrial fibrillation who were randomized 2:1 to the Watchman device or warfarin, with 4,343 patient-years of follow-up. This was a fairly high–stroke risk population, with CHA2DS2-VASc scores in the 3.6-3.9 range, and 40% of patients aged 75 years or more. At baseline, 23% of subjects had a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.

At 5 years’ follow-up, the composite endpoint of all stroke or systemic embolism was the same in the two study arms. However, the rate of hemorrhagic stroke was 80% lower in the Watchman group, the risk of disabling or fatal stroke was reduced by 55%, the rate of cardiovascular or unexplained death was 41% lower, all-cause mortality was reduced by 27%, and postprocedure major bleeding was 52% less frequent in the device therapy group. All of these differences achieved statistical significance, the cardiologist reported at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

On the downside, the rate of ischemic stroke trended higher in the Watchman group, although the 71% increase in relative risk didn’t achieve statistical significance (P = .08). Dr. Kar asserted that this unhappy trend was a statistical fluke resulting from a low number of events and an implausibly low ischemic stroke rate of 0.73% per year in the warfarin group.

“This is the lowest rate of ischemic stroke in any study of warfarin. In fact, if this was the ischemic stroke rate in any of the NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant] studies, none of those drugs would actually have been approved. Why did we get such an implausibly low ischemic stroke rate? It’s a function of lower numbers and larger confidence intervals,” he said.

Gregg W. Stone, MD, who moderated the discussion panel at the late-breaking clinical trial session, advised Dr. Kar to be less defensive about the ischemic stroke findings.

“I think we have to be a little less apologetic for the great outcomes in the warfarin arm in PREVAIL. We do these randomized trials, and we get what we get,” said Dr. Stone, professor of medicine at Columbia University in New York.

Stephen G. Ellis, MD, said he was particularly impressed with the reduced rate of disabling stroke in the Watchman group.

“Severity of stroke is important. I hadn’t seen that data before,” commented Dr. Ellis, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic. “The overall message, I think, is that for the patients who would have been candidates to be enrolled in these trials, the device seems to be quite worthwhile. I take note of the overall benefit in terms of cardiovascular death and all-cause death.”

Robert J. Sommer, MD, said that in patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc scores and previous bleeding on oral anticoagulants, the new data show that the Watchman “is a no-brainer. The patients all want it, the physicians all want it. It’s a very easy decision to make.”

“But you get into other groups who may potentially be interested in the device – particularly the younger patients who are very active and don’t want to be on anticoagulation – I think the ischemic stroke rate in the device arm trending to be higher is a problem for them. And it’s certainly going to be a problem for their physicians. But as we go on, I think with further studies we’ll see expanded indications. Patients with CAD who potentially would need triple therapy – that’s a nice population to study in this area. We’ll also be seeing data on other devices that may have different ischemic stroke rates,” said Dr. Sommer, director of invasive adult congenital heart disease at Columbia University Medical Center.

“I find this data extraordinarily helpful as I think about my conversations with patients about stroke prevention,” said Brian K. Whisenant, MD, medical director of structural heart disease at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City.

“I tell them we think of oral anticoagulants as first-line therapy based on a stroke rate of 1% per year or less in most datasets. The data for the Watchman device has been very consistent in that we have a stroke rate that’s a little bit higher, at 1.3%-1.8% per year. And we have extensive data for predicting the stroke rate in the absence of oral anticoagulation: In most of our patients, that rate is in excess of 5% per year. So while the Watchman device may not provide the absolute reduction in ischemic stroke rate that oral anticoagulants do, a stroke rate of less than 2% is a whole lot better than no therapy for many of these patients,” the cardiologist said.

Martin B. Leon, MD, opined that the ischemic stroke data cannot be explained away. But he added that the totality of the meta-analysis data gives him confidence that this is the appropriate treatment in these patients.

“It does leave open the question of whether we can do better with ischemic strokes. Some people are suggesting that maybe adjunctive pharmacotherapy – perhaps a low-dose NOAC – may be a reasonable option in some patients to get even better results. That’s something I believe is open for discussion,” said Dr. Leon, professor of medicine at Columbia University and director of the Center for Interventional Vascular Therapy at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Dr. Stone summed up: “There’s uniformity among the panel that there may be a slightly lower ischemic stroke rate with oral anticoagulation, and the NOACs probably provide some additional benefit, with an additional 50% reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, compared to warfarin. But that being said, I believe that left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman is the viable and now clearly safe approach for patients with any sort of contraindication or strong desire to avoid oral anticoagulation.”

The PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials and meta-analysis were sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kar reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Abbott Vascular.

Simultaneously with Dr. Kar’s presentation at TCT 2017, the findings were published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

SOURCE: Reddy VY et al. TCT 2017; J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 4. pii:S0735-1097(17)41187-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.021.

REPORTING FROM TCT 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: All-cause mortality was reduced by 27% in patients randomized to left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman device, compared with those assigned to warfarin.

Study details: This patient-level meta-analysis included 5-year follow-up data on 1,114 patients with atrial fibrillation at increased stroke risk who were randomized 2:1 to the Watchman device or warfarin.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to study sponsor Boston Scientific.

CMS clinical trials raise cardiac mortality

Nearly 2 years ago I speculated in this column that health planners or health economists would attempt to manipulate the patterns of patient care to influence the cost and/or quality of clinical care. At that time I suggested that, in that event, the intervention should be managed as we have with drug or device trials to ensure the authenticity and accuracy and most of all assuring the safety of the patient. Furthermore, the design should be incorporated in the intervention, that equipoise be present in the arms of the trial and that a safety monitoring board be in place to alert investigators when and if patient safety is threatened. Patient consent should also be obtained.

Beginning in 2012, CMS, using claims data from 2008 to 2012, penalized hospitals if they did not achieve acceptable readmission rates. At the same time, the agency established the Hospital Admission Reduction Program to monitor 30-day mortality and standardize readmission data. The recent data indicate that the incentives did achieve some decrease in rehospitalization but this was associated with a 16.5% relative increase in 30-day mortality. It was of particular concern that in the previous decade there had been a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (Circulation 2014;130:966-75). The increase in 30-day mortality observed in the 4-year observational period appears to have interrupted the progressive decrease in 30-day mortality, which would have decreased to 30% if not impacted by the plan.

My previous concerns with this type of social experimentation and manipulation of health care was carried out, and as far as I can tell, continues without any oversight and little insight into the possible risks of this process. A better designed study would have provided better understanding of these results and might have mitigated the adverse effects and mortality events. It is suggested that some hospitals actually gamed the system to their economic advantage. In addition, no oversight board was or is in place as we have with drug trials to allow monitors to become aware of adverse events before there any further loss of life occurs.

I would agree that a randomized trial in this environment would be difficult to achieve. Obtaining consent from thousands of patients would also be difficult. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Nearly 2 years ago I speculated in this column that health planners or health economists would attempt to manipulate the patterns of patient care to influence the cost and/or quality of clinical care. At that time I suggested that, in that event, the intervention should be managed as we have with drug or device trials to ensure the authenticity and accuracy and most of all assuring the safety of the patient. Furthermore, the design should be incorporated in the intervention, that equipoise be present in the arms of the trial and that a safety monitoring board be in place to alert investigators when and if patient safety is threatened. Patient consent should also be obtained.

Beginning in 2012, CMS, using claims data from 2008 to 2012, penalized hospitals if they did not achieve acceptable readmission rates. At the same time, the agency established the Hospital Admission Reduction Program to monitor 30-day mortality and standardize readmission data. The recent data indicate that the incentives did achieve some decrease in rehospitalization but this was associated with a 16.5% relative increase in 30-day mortality. It was of particular concern that in the previous decade there had been a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (Circulation 2014;130:966-75). The increase in 30-day mortality observed in the 4-year observational period appears to have interrupted the progressive decrease in 30-day mortality, which would have decreased to 30% if not impacted by the plan.

My previous concerns with this type of social experimentation and manipulation of health care was carried out, and as far as I can tell, continues without any oversight and little insight into the possible risks of this process. A better designed study would have provided better understanding of these results and might have mitigated the adverse effects and mortality events. It is suggested that some hospitals actually gamed the system to their economic advantage. In addition, no oversight board was or is in place as we have with drug trials to allow monitors to become aware of adverse events before there any further loss of life occurs.

I would agree that a randomized trial in this environment would be difficult to achieve. Obtaining consent from thousands of patients would also be difficult. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Nearly 2 years ago I speculated in this column that health planners or health economists would attempt to manipulate the patterns of patient care to influence the cost and/or quality of clinical care. At that time I suggested that, in that event, the intervention should be managed as we have with drug or device trials to ensure the authenticity and accuracy and most of all assuring the safety of the patient. Furthermore, the design should be incorporated in the intervention, that equipoise be present in the arms of the trial and that a safety monitoring board be in place to alert investigators when and if patient safety is threatened. Patient consent should also be obtained.

Beginning in 2012, CMS, using claims data from 2008 to 2012, penalized hospitals if they did not achieve acceptable readmission rates. At the same time, the agency established the Hospital Admission Reduction Program to monitor 30-day mortality and standardize readmission data. The recent data indicate that the incentives did achieve some decrease in rehospitalization but this was associated with a 16.5% relative increase in 30-day mortality. It was of particular concern that in the previous decade there had been a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (Circulation 2014;130:966-75). The increase in 30-day mortality observed in the 4-year observational period appears to have interrupted the progressive decrease in 30-day mortality, which would have decreased to 30% if not impacted by the plan.

My previous concerns with this type of social experimentation and manipulation of health care was carried out, and as far as I can tell, continues without any oversight and little insight into the possible risks of this process. A better designed study would have provided better understanding of these results and might have mitigated the adverse effects and mortality events. It is suggested that some hospitals actually gamed the system to their economic advantage. In addition, no oversight board was or is in place as we have with drug trials to allow monitors to become aware of adverse events before there any further loss of life occurs.

I would agree that a randomized trial in this environment would be difficult to achieve. Obtaining consent from thousands of patients would also be difficult. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Carotid-axillary bypass for revascularization of the left subclavian artery in zone-2 TEVAR

Stent-graft coverage of the left subclavian artery (LSA) is often performed during TEVAR treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies and, consequently, debranching of the LSA is frequently performed in such settings. The carotid-subclavian bypass (CSB) is undoubtedly the cervical bypass option preferred by most surgeons for this purpose.1,2 The technique was first described by Lyons and Galbraith in 1957,3 and popularized by Diethrich et al. who reported their large experience in a well-known article published 10 years later.4 In the ensuing decades, CSB became the overwhelming favorite of surgeons everywhere performing LSA revascularization for management of arterial occlusive disease and, more recently, in the context of zone-2 TEVAR. Well- documented good results would seem to justify such preference,5 but some level of concern has been voiced consistently over the years about some technical complexities and potential complications such as phrenic nerve and thoracic duct injuries.6 My own personal experience substantiated these reservations early on, prompting adoption of an alternative operative solution with use of the carotid-axillary bypass (CAB),7 an operation first reported by Shumacker in 1973.8 In my hands, it has produced equivalent results to the carotid-subclavian technique in terms of efficacy and durability, and with the additional appeal of distinct practical advantages – mainly because the axillary artery tends to be an easier vessel to expose and handle, and through the avoidance of complications resulting from damage to anatomical structures that are often in harm’s way when exposing the LSA.

Technical aspects

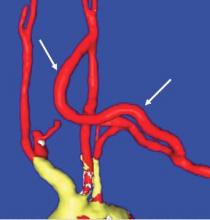

End-to-side anastomoses proximally and distally are constructed in routine manner (Fig. 2). We do not use carotid shunting for this procedure.

Occasionally one may want to combine a carotid endarterectomy with the cervical bypass, in which case the proximal vascular graft anastomosis is constructed at the endarterectomy site (Fig. 3). Close attention must be paid to careful length-tailoring the conduit to achieve the desirable gently curving course without undue tension or redundancy.

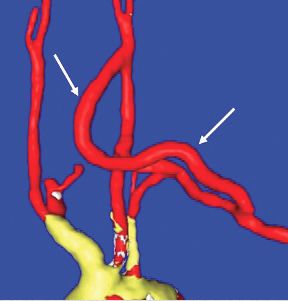

Proximal ligation of the LSA, often performed during the CSB, cannot be a component of the carotid-axillary operation because of inaccessibility. Some experts look upon this as a disadvantage, but I tend to view such limitation as advantageous because it eliminates the potential for a misplaced ligation distal to the left vertebral artery origin which present-day CTA studies show it to be the case more frequently than previously suspected. If interruption of the LSA is deemed necessary, it is arguably best to use an endovascular (retrograde trans-brachial) approach with precise deployment of a vascular plug device under angiographic guidance (Fig. 4). ■

Dr. Criado is at MedStar Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore.

References

1. J Endovasc Ther 2002;9(suppl 2):1132-1138.

2. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:247-260.

3. Ann Surg 1957;146:487-494.

4. Am J Surg 1967;114:800-808.

5. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:555-560.

6. Ann Vasc Surg 2008;22:70-78.

7. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:717-723.

8. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1973;136:447-8.

9. J Vasc Surg 1999;30:1106-1112.

Stent-graft coverage of the left subclavian artery (LSA) is often performed during TEVAR treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies and, consequently, debranching of the LSA is frequently performed in such settings. The carotid-subclavian bypass (CSB) is undoubtedly the cervical bypass option preferred by most surgeons for this purpose.1,2 The technique was first described by Lyons and Galbraith in 1957,3 and popularized by Diethrich et al. who reported their large experience in a well-known article published 10 years later.4 In the ensuing decades, CSB became the overwhelming favorite of surgeons everywhere performing LSA revascularization for management of arterial occlusive disease and, more recently, in the context of zone-2 TEVAR. Well- documented good results would seem to justify such preference,5 but some level of concern has been voiced consistently over the years about some technical complexities and potential complications such as phrenic nerve and thoracic duct injuries.6 My own personal experience substantiated these reservations early on, prompting adoption of an alternative operative solution with use of the carotid-axillary bypass (CAB),7 an operation first reported by Shumacker in 1973.8 In my hands, it has produced equivalent results to the carotid-subclavian technique in terms of efficacy and durability, and with the additional appeal of distinct practical advantages – mainly because the axillary artery tends to be an easier vessel to expose and handle, and through the avoidance of complications resulting from damage to anatomical structures that are often in harm’s way when exposing the LSA.

Technical aspects

End-to-side anastomoses proximally and distally are constructed in routine manner (Fig. 2). We do not use carotid shunting for this procedure.

Occasionally one may want to combine a carotid endarterectomy with the cervical bypass, in which case the proximal vascular graft anastomosis is constructed at the endarterectomy site (Fig. 3). Close attention must be paid to careful length-tailoring the conduit to achieve the desirable gently curving course without undue tension or redundancy.

Proximal ligation of the LSA, often performed during the CSB, cannot be a component of the carotid-axillary operation because of inaccessibility. Some experts look upon this as a disadvantage, but I tend to view such limitation as advantageous because it eliminates the potential for a misplaced ligation distal to the left vertebral artery origin which present-day CTA studies show it to be the case more frequently than previously suspected. If interruption of the LSA is deemed necessary, it is arguably best to use an endovascular (retrograde trans-brachial) approach with precise deployment of a vascular plug device under angiographic guidance (Fig. 4). ■

Dr. Criado is at MedStar Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore.

References

1. J Endovasc Ther 2002;9(suppl 2):1132-1138.

2. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:247-260.

3. Ann Surg 1957;146:487-494.

4. Am J Surg 1967;114:800-808.

5. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:555-560.

6. Ann Vasc Surg 2008;22:70-78.

7. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:717-723.

8. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1973;136:447-8.

9. J Vasc Surg 1999;30:1106-1112.