User login

Transporting stroke patients directly to thrombectomy boosts outcomes

LOS ANGELES – Evidence continues to mount that in the new era of thrombectomy treatment for selected acute ischemic stroke patients outcomes are better when patients go directly to the closest comprehensive stroke center that offers intravascular procedures rather than first being taken to a closer hospital and then needing transfer.

Nils H. Mueller-Kronast, MD, presented a modeled analysis of data collected in a registry on 236 real-world U.S. patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy for an acute, large-vessel occlusion stroke following transfer from a hospital that could perform thrombolysis but couldn’t offer thrombectomy. The analysis showed that if the patients had instead gone directly to the closest thrombectomy center the result would have been a 16-percentage-point increase in patients with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-1 after 90 days, and a 9-percentage-point increase in mRS 0-2 outcomes, Dr. Mueller-Kronast said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The analysis he presented used data from the Systematic Evaluation of Patients Treated With Stroke Devices for Acute Ischemic Stroke (STRATIS) registry, which included 984 acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy at any one of 55 participating U.S. sites (Stroke. 2017 Oct;48[10]:2760-8). A previously-reported analysis of the STRATIS data showed that the 55% of patients taken directly to a center that performed thrombectomy had a 60% rate of mRS score 0-2 after 90 days, compared with 52% of patients taken first to a hospital unable to perform thrombectomy and then transferred (Circulation. 2017 Dec 12;136[24]:2311-21).

The current analysis focused on 236 of the transferred patients with complete information on their location at the time of their stroke and subsequent time intervals during their transport and treatment, including 117 patients with ground transfer from their first hospital to the thrombectomy site, 114 with air transfer, and 5 with an unreported means of transport.

Dr. Mueller-Kronast and his associates calculated the time it would have taken each of the 117 ground transported patients to have gone directly to the closest thrombectomy center (adjusted by traffic conditions at the time of the stroke), and modeled the likely outcomes of these patients based on the data collected in the registry. This projected a 47% rate of mRS scores 0-1 (good outcomes) after 90 days, and a 60% rate of mRS 0-2 scores with a direct-to-thrombectomy strategy, compared with actual rates of 31% and 51%, respectively, among the patients who were transferred from their initial hospital.

“Bypass to an endovascular-capable center may be an option to improve rapid access to mechanical thrombectomy,” he concluded.

The STRATIS registry is sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Mueller-Kronast has been a consultant to Medtronic.

SOURCE: Mueller-Kronast N et al. Abstract LB12.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence continues to mount that in the new era of thrombectomy treatment for selected acute ischemic stroke patients outcomes are better when patients go directly to the closest comprehensive stroke center that offers intravascular procedures rather than first being taken to a closer hospital and then needing transfer.

Nils H. Mueller-Kronast, MD, presented a modeled analysis of data collected in a registry on 236 real-world U.S. patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy for an acute, large-vessel occlusion stroke following transfer from a hospital that could perform thrombolysis but couldn’t offer thrombectomy. The analysis showed that if the patients had instead gone directly to the closest thrombectomy center the result would have been a 16-percentage-point increase in patients with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-1 after 90 days, and a 9-percentage-point increase in mRS 0-2 outcomes, Dr. Mueller-Kronast said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The analysis he presented used data from the Systematic Evaluation of Patients Treated With Stroke Devices for Acute Ischemic Stroke (STRATIS) registry, which included 984 acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy at any one of 55 participating U.S. sites (Stroke. 2017 Oct;48[10]:2760-8). A previously-reported analysis of the STRATIS data showed that the 55% of patients taken directly to a center that performed thrombectomy had a 60% rate of mRS score 0-2 after 90 days, compared with 52% of patients taken first to a hospital unable to perform thrombectomy and then transferred (Circulation. 2017 Dec 12;136[24]:2311-21).

The current analysis focused on 236 of the transferred patients with complete information on their location at the time of their stroke and subsequent time intervals during their transport and treatment, including 117 patients with ground transfer from their first hospital to the thrombectomy site, 114 with air transfer, and 5 with an unreported means of transport.

Dr. Mueller-Kronast and his associates calculated the time it would have taken each of the 117 ground transported patients to have gone directly to the closest thrombectomy center (adjusted by traffic conditions at the time of the stroke), and modeled the likely outcomes of these patients based on the data collected in the registry. This projected a 47% rate of mRS scores 0-1 (good outcomes) after 90 days, and a 60% rate of mRS 0-2 scores with a direct-to-thrombectomy strategy, compared with actual rates of 31% and 51%, respectively, among the patients who were transferred from their initial hospital.

“Bypass to an endovascular-capable center may be an option to improve rapid access to mechanical thrombectomy,” he concluded.

The STRATIS registry is sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Mueller-Kronast has been a consultant to Medtronic.

SOURCE: Mueller-Kronast N et al. Abstract LB12.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence continues to mount that in the new era of thrombectomy treatment for selected acute ischemic stroke patients outcomes are better when patients go directly to the closest comprehensive stroke center that offers intravascular procedures rather than first being taken to a closer hospital and then needing transfer.

Nils H. Mueller-Kronast, MD, presented a modeled analysis of data collected in a registry on 236 real-world U.S. patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy for an acute, large-vessel occlusion stroke following transfer from a hospital that could perform thrombolysis but couldn’t offer thrombectomy. The analysis showed that if the patients had instead gone directly to the closest thrombectomy center the result would have been a 16-percentage-point increase in patients with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-1 after 90 days, and a 9-percentage-point increase in mRS 0-2 outcomes, Dr. Mueller-Kronast said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The analysis he presented used data from the Systematic Evaluation of Patients Treated With Stroke Devices for Acute Ischemic Stroke (STRATIS) registry, which included 984 acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy at any one of 55 participating U.S. sites (Stroke. 2017 Oct;48[10]:2760-8). A previously-reported analysis of the STRATIS data showed that the 55% of patients taken directly to a center that performed thrombectomy had a 60% rate of mRS score 0-2 after 90 days, compared with 52% of patients taken first to a hospital unable to perform thrombectomy and then transferred (Circulation. 2017 Dec 12;136[24]:2311-21).

The current analysis focused on 236 of the transferred patients with complete information on their location at the time of their stroke and subsequent time intervals during their transport and treatment, including 117 patients with ground transfer from their first hospital to the thrombectomy site, 114 with air transfer, and 5 with an unreported means of transport.

Dr. Mueller-Kronast and his associates calculated the time it would have taken each of the 117 ground transported patients to have gone directly to the closest thrombectomy center (adjusted by traffic conditions at the time of the stroke), and modeled the likely outcomes of these patients based on the data collected in the registry. This projected a 47% rate of mRS scores 0-1 (good outcomes) after 90 days, and a 60% rate of mRS 0-2 scores with a direct-to-thrombectomy strategy, compared with actual rates of 31% and 51%, respectively, among the patients who were transferred from their initial hospital.

“Bypass to an endovascular-capable center may be an option to improve rapid access to mechanical thrombectomy,” he concluded.

The STRATIS registry is sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Mueller-Kronast has been a consultant to Medtronic.

SOURCE: Mueller-Kronast N et al. Abstract LB12.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2018

Key clinical point: A direct-to-thrombectomy strategy maximizes good stroke outcomes.

Major finding: Modeling showed a 47% rate of good 90-day outcomes by taking patients to the closest thrombectomy center, compared with an actual 31% rate with transfers.

Study details: A simulation-model analysis of data collected by the STRATIS registry of acute stroke thrombectomies.

Disclosures: The STRATIS registry is sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Mueller-Kronast has been a consultant to Medtronic.

Source: Mueller-Kronast N et al. Abstract LB12.

Thrombectomy’s success treating strokes prompts rethinking of selection criteria

LOS ANGELES – CT or magnetic resonance brain imaging of acute ischemic stroke patients was the key triage tool in two groundbreaking thrombectomy trials, DAWN and DEFUSE; results from both showed that patients found by imaging to have limited infarcted cores could safely benefit from endovascular thrombectomy, even when they are more than 6 hours out from their stroke onset, breaking the 6-hour barrier created 3 years ago by the first wave of thrombectomy trials.

But some stroke neurologists studying thrombectomy are now convinced that imaging is not needed and may actually harm acute ischemic stroke patients early on by introducing an unnecessary time delay when they present within the first 6 hours after stroke onset.

This new thinking on how to best use brain imaging in acute ischemic stroke patients is part of the rapid evolution of acute stroke management as experts process new data and refine their approach both within 6 hours of stroke onset and during the new treatment window of 6-24 hours post onset. The dramatic success achieved with thrombectomy in highly selected late-window patients prompted researchers to promote pushing the boundaries further to find less-selected late patients who could also potentially benefit from thrombectomy.

The downside of early imaging

“Early on, we have a mix of fast and slow progressors. Slow progressors are about a third to half the patients, so there is a lot of potential for [late] treatment, but the majority of patients during the first 6 hours after onset are fast progressors,” patients who won’t benefit from thrombectomy delivery beyond 6 hours, said Dr. Jovin, an interventional neurologist and director of the Stroke Institute of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

“Time is very precious in the 0- to 6-hour window. When we’re dealing with a lot of fast progressors, we pay a price [in added time to treatment] for any imaging we do. We need to understand that this is a real price we pay, even when CT takes perhaps 24 minutes, and MRI adds about 12 minutes. It’s not the case in all patients that doing CT angiography just adds 5 minutes. It can take 15, 20 minutes,” especially at centers that don’t treat these types of stroke patients day in and day out. “There is no question that imaging slows us down,” Dr. Jovin said.

He highlighted that “the main role of imaging is to exclude patients from treatment, a treatment that has unbelievable effects.” Imaging can rule out patients who have a hemorrhage, lack an occlusion, have a large infarcted core, or have none of the brain at risk or just a small amount, he noted. “Excluding hemorrhage is reasonable, but we can do that in the angiography suite, when the patient is on the table. The main benefit from advanced imaging is to more precisely define the core,” but for most patients the size of their core is not important because the vast majority of acute ischemic stroke patients seen within 6 hours of onset have cores smaller than 70 mL.

“Is this much ado about nothing – especially because we punish all the other patients [with smaller cores] who need to be treated [quickly] when we do additional imaging?” asked Dr. Jovin, who was one of the two lead investigators for the Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention With Trevo (DAWN) trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 4;378[1]:11-21). Another factor undercutting the value of imaging and determining core size is registry results that show patients who undergo thrombectomy with a large infarcted core are not harmed by treatment.

Current practice often uses imaging “to exclude the 20% of patients who may not have a large vessel occlusion or may not get benefit but whom we are unlikely to harm. But we harm the other 80% by delaying treatment by 30 minutes because of imaging. That’s why we need to rethink imaging and minimize its use.”

Dr. Jovin noted that at his center in Pittsburgh, the stroke institute staff began in 2013 to take patients transported from other stroke facilities and already diagnosed with a large vessel occlusion directly to the angiography suite, bypassing further brain imaging. By doing this, they cut their average door-to-groin puncture time down to 22 minutes from what had been an average of 81 minutes with imaging (Stroke. 2017 July;48[7]:1884-9). Right now the door-to-groin time is even lower, he added.

“Don’t waste time imaging,” said Dr. Nogueira, a stroke neurologist who is director of the neuroendovascular division of the Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center and professor of neurology, neurosurgery, and radiology at Emory University, both in Atlanta, as well as the second lead investigator for DAWN. “Time is crucial and trumps patient selection. Most selection criteria are informative rather than truly selective. It is important to understand that in every time window, we do not yet know who doesn’t benefit from treatment. Select faster, select less, and treat more” during the 0- to 6-hour window, he told his colleagues.

Expanding thrombectomy 6-24 hours after stroke onset

While Dr. Jovin and Dr. Nogueira called for more aggressive and less selective use of thrombectomy in patients who present within 6 hours of their stroke onset, they acknowledged that for patients who present during the 6- to 24-hour window, selection for thrombectomy should follow the rules applied in DAWN and in the more inclusive Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke (DEFUSE 3) trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 22;378:708-18). That means using imaging to confirm that the patient’s infarcted core is within the enrollment ceiling, but both neurologists also downplayed the need for the more sophisticated imaging approaches that were often used in both trials as well as in current routine practice at comprehensive stroke centers. They agreed that noncontrast CT, a widely available method, seems adequate for patient selection, based on the admittedly limited data available right now.

Dr. Nogueira cited data from the Trevo stent retriever registry, collected from nearly 1,000 U.S. acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent thrombectomy with this device. (Researchers at the conference reported updated registry data with nearly 2,000 patients with findings similar to what Dr. Nogueira referenced.) Although these patients underwent treatment before results of DAWN and DEFUSE 3 came out and before release of the new U.S. acute stroke management guidelines (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24; doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158) that endorsed targeted thrombectomy for patients 6-24 hours out from their stroke onset, 278 (28%) of the registry patients underwent thrombectomy treatment during the 6- to 24-hour time window. In this subgroup, 34 patients underwent noncontrast CT to assess their infarcted core prior to thrombectomy, while the other patients underwent perfusion CT, MRI, or both. The noncontrast CT patients had recanalization rates, adverse event rates, and 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores comparable with those of patients assessed with more advanced imaging.

Based on this, “just looking at CT only seems reasonable. Noncontrast CT is a pretty valid way to select patients,” Dr. Nogueira said.

“This is the direction we should follow to simplify the paradigm for treating beyond 6 hours,” agreed Dr. Jovin, who also called for further advances in patient selection to expand the pool of patients who qualify for thrombectomy during the 6- to 24-hour postonset period.

“We want the DAWN results to be generalizable, to be simpler. We are exploring some more easily generalizable inclusion criteria that would allow us to treat more patients in more parts of the world,” Dr. Jovin added.

Both clinicians cited the remarkably low number needed to treat found in both DAWN and DEFUSE 3 of roughly three patients to produce one additional patient with a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in their 90-day mRS score, compared with controls, as an unmistakable sign that the treatment in both trials was too targeted.

“When we planned the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials we didn’t expect how powerful the treatment effect would be. There are probably other patients who could also benefit, so how low can we go? How liberal can we be in our inclusion criteria and still get benefit?” Dr. Jovin asked.

“When intravenous TPA [tissue plasminogen activator] first came out, we went by the book [for patient selection], but as we got to know the treatment and became more comfortable with it, we began to bend the rules. Now we’re at the point of getting comfortable with endovascular treatment, and we need to figure out where to bend the rules by building the database. There is no doubt that the rules need bending because of the treatment effect that we’ve seen. We need to get our patients to endovascular treatment,” she said in her presentation at the conference.

But these physicians realize that for the time being, standard of care will follow the imaging and data processing primarily used in DAWN and DEFUSE 3, which not only involved perfusion CT or MRI but also a proprietary, automated image processing software, RAPID, that takes imaging data and calculates the amount and ratio of infarcted core and hypoperfused, ischemic brain tissue.

“I asked our imaging experts [at the University of Cincinnati] what should my threshold be [for mismatch between the infarcted core and ischemic tissue], and they said, ‘Use the automated software,’ ” Dr. Khatri said. If centers managing acute ischemic stroke patients don’t already have this software, “they need it. I think there is no way around that. It’s the only way we’ll be able to do this,” she commented. Most U.S. community hospitals that admit stroke patients currently lack this software, largely because of its high cost, she added.

“We’re struggling because it is very difficult to get some community hospitals – primary stroke centers – to invest in the software, but that’s really the only way we’ll be able to do this. There are issues of cost, and of getting technicians trained,” she noted.

That’s because DEFUSE 3 enrolled patients with a baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of at least 6, while patients in DAWN required a score of at least 10, a loosening that allowed inclusion of 31 patients with scores of 6-9 in DEFUSE 3. Another, less restrictive criterion was the patient’s prestroke mRS score, which could have been 0-2 in DEFUSE 3 but could be only 0-1 in DAWN. Thirteen of the DEFUSE 3 patients had prestroke mRS scores of 2. DEFUSE 3 also had somewhat more liberal criteria for the size of a patient’s infarcted core at enrollment, with 41 patients who would have been excluded from DAWN because of an overly large infarcted core, Dr. Albers said in his presentation at the conference.

Currently, for patients presenting more than 16 hours following their stroke onset but within 24 hours, the DAWN enrollment criteria exclusively determine which patients should get thrombectomy.

One area where these rules could be bent is by a more thoughtful approach to the prestroke mRS score rule out, such as patients with orthopedic or rheumatic complications that limit mobility and give them an mRS score of 3. “We don’t have data for patients with back pain who can’t walk. I currently take these patients to endovascular therapy, and I’m sure many others do, too,” Dr. Khatri said.

Another potential way to grow the inclusion criteria is to investigate thrombectomy in patients with larger infarcted cores than were enrolled in DAWN and DEFUSE 3, but assessing this will require a new prospective study, Dr. Albers said.

Running the 6- to 24-hour numbers

Adoption of the 6- to 24-hour time window for endovascular intervention in selected patients means that suddenly the U.S. acute stroke infrastructure needs to accommodate a significantly increased number of patients. Just how many added patients this means is uncertain for the time being, and will vary from region to region and center to center. Dr. Albers roughly guessed that the new late time window might double the number of stroke patients undergoing thrombectomy at his center in Stanford. Dr. Khatri put together a more data-driven but still very speculative estimate that at the University of Cincinnati, it will mean about 40% more stroke patients going to thrombectomy. She shared the numbers behind this estimate in a report she gave at the conference.

To calculate the incremental change produced by the late time window, she used data collected on 2,297 acute ischemic stroke patients from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region who were seen at the University of Cincinnati during 2010. Prior analysis by Dr. Khatri and her associates showed that 159 of these patients presented quickly enough and with an appropriate stroke to qualify for thrombolytic therapy, and that 29 patients would have qualified for thrombectomy performed during the 0- to 6-hour time window.

In the new analysis Dr. Khatri calculated that 791 patients presented at 5-23 hours, and of these 34 had other features that would have made them eligible for enrollment in DAWN. Because no imaging data existed for these 2010 patients, she applied an estimate that 22% of these patients would qualify by the size of their infarcted core and ischemic penumbra, resulting in seven additional thrombectomy-eligible patients. Accounting for patients who would qualify by the more liberal DEFUSE 3 criteria added another 5 patients for a total increment of 12 patients during 2010 who would have been eligible for thrombectomy, about 40% of the number from the 0- to 6-hour window.

She noted that “this is likely an underestimate,” and “too small a sample to project to national estimates,” but concluded that “resources must be adapted to account for this increased volume in endovascular treatment.”

Dr. Khatri acknowledged that the new 6- to 24-hour window for endovascular therapy, and concerns about imaging delays in 0- to 6-hour patients, raise challenging issues regarding the message to give U.S. clinicians about treating acute ischemic stroke patients.

“We have a mandate to figure it out in every region. There is no doubt that stroke patients need access to this care. We need to become a lot more aggressive with endovascular treatment. It’s so gratifying to see the outcomes that we’re seeing,” Dr. Khatri said. “A lot of work is needed to accommodate endovascular therapy–eligible patients in an extended time window. We need more refined prehospital triage tools, we need to adequately implement imaging software, and we need increased capacity to perform endovascular treatment with additional procedure suites, operators, and ICU beds.”

Dr. Jovin has been a consultant to Anaconda Biomed, Blockade Medical, Cerenovus, FreeOx Biotech, and Silk Road Medical. Dr. Nogueira has received travel expense reimbursement from Stryker. Dr. Khatri has been a consultant to Biogen, Medpace/Novartis, and St. Jude; has received travel support from Neuravi and EmstoPA; and has received research support from Genentech, Lumosa, and Neurospring. Dr. Albers has an ownership interest in iSchemaView, the company that markets the RAPID imaging software, and is a consultant to iSchemaView and Medtronic.

LOS ANGELES – CT or magnetic resonance brain imaging of acute ischemic stroke patients was the key triage tool in two groundbreaking thrombectomy trials, DAWN and DEFUSE; results from both showed that patients found by imaging to have limited infarcted cores could safely benefit from endovascular thrombectomy, even when they are more than 6 hours out from their stroke onset, breaking the 6-hour barrier created 3 years ago by the first wave of thrombectomy trials.

But some stroke neurologists studying thrombectomy are now convinced that imaging is not needed and may actually harm acute ischemic stroke patients early on by introducing an unnecessary time delay when they present within the first 6 hours after stroke onset.

This new thinking on how to best use brain imaging in acute ischemic stroke patients is part of the rapid evolution of acute stroke management as experts process new data and refine their approach both within 6 hours of stroke onset and during the new treatment window of 6-24 hours post onset. The dramatic success achieved with thrombectomy in highly selected late-window patients prompted researchers to promote pushing the boundaries further to find less-selected late patients who could also potentially benefit from thrombectomy.

The downside of early imaging

“Early on, we have a mix of fast and slow progressors. Slow progressors are about a third to half the patients, so there is a lot of potential for [late] treatment, but the majority of patients during the first 6 hours after onset are fast progressors,” patients who won’t benefit from thrombectomy delivery beyond 6 hours, said Dr. Jovin, an interventional neurologist and director of the Stroke Institute of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

“Time is very precious in the 0- to 6-hour window. When we’re dealing with a lot of fast progressors, we pay a price [in added time to treatment] for any imaging we do. We need to understand that this is a real price we pay, even when CT takes perhaps 24 minutes, and MRI adds about 12 minutes. It’s not the case in all patients that doing CT angiography just adds 5 minutes. It can take 15, 20 minutes,” especially at centers that don’t treat these types of stroke patients day in and day out. “There is no question that imaging slows us down,” Dr. Jovin said.

He highlighted that “the main role of imaging is to exclude patients from treatment, a treatment that has unbelievable effects.” Imaging can rule out patients who have a hemorrhage, lack an occlusion, have a large infarcted core, or have none of the brain at risk or just a small amount, he noted. “Excluding hemorrhage is reasonable, but we can do that in the angiography suite, when the patient is on the table. The main benefit from advanced imaging is to more precisely define the core,” but for most patients the size of their core is not important because the vast majority of acute ischemic stroke patients seen within 6 hours of onset have cores smaller than 70 mL.

“Is this much ado about nothing – especially because we punish all the other patients [with smaller cores] who need to be treated [quickly] when we do additional imaging?” asked Dr. Jovin, who was one of the two lead investigators for the Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention With Trevo (DAWN) trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 4;378[1]:11-21). Another factor undercutting the value of imaging and determining core size is registry results that show patients who undergo thrombectomy with a large infarcted core are not harmed by treatment.

Current practice often uses imaging “to exclude the 20% of patients who may not have a large vessel occlusion or may not get benefit but whom we are unlikely to harm. But we harm the other 80% by delaying treatment by 30 minutes because of imaging. That’s why we need to rethink imaging and minimize its use.”

Dr. Jovin noted that at his center in Pittsburgh, the stroke institute staff began in 2013 to take patients transported from other stroke facilities and already diagnosed with a large vessel occlusion directly to the angiography suite, bypassing further brain imaging. By doing this, they cut their average door-to-groin puncture time down to 22 minutes from what had been an average of 81 minutes with imaging (Stroke. 2017 July;48[7]:1884-9). Right now the door-to-groin time is even lower, he added.

“Don’t waste time imaging,” said Dr. Nogueira, a stroke neurologist who is director of the neuroendovascular division of the Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center and professor of neurology, neurosurgery, and radiology at Emory University, both in Atlanta, as well as the second lead investigator for DAWN. “Time is crucial and trumps patient selection. Most selection criteria are informative rather than truly selective. It is important to understand that in every time window, we do not yet know who doesn’t benefit from treatment. Select faster, select less, and treat more” during the 0- to 6-hour window, he told his colleagues.

Expanding thrombectomy 6-24 hours after stroke onset

While Dr. Jovin and Dr. Nogueira called for more aggressive and less selective use of thrombectomy in patients who present within 6 hours of their stroke onset, they acknowledged that for patients who present during the 6- to 24-hour window, selection for thrombectomy should follow the rules applied in DAWN and in the more inclusive Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke (DEFUSE 3) trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 22;378:708-18). That means using imaging to confirm that the patient’s infarcted core is within the enrollment ceiling, but both neurologists also downplayed the need for the more sophisticated imaging approaches that were often used in both trials as well as in current routine practice at comprehensive stroke centers. They agreed that noncontrast CT, a widely available method, seems adequate for patient selection, based on the admittedly limited data available right now.

Dr. Nogueira cited data from the Trevo stent retriever registry, collected from nearly 1,000 U.S. acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent thrombectomy with this device. (Researchers at the conference reported updated registry data with nearly 2,000 patients with findings similar to what Dr. Nogueira referenced.) Although these patients underwent treatment before results of DAWN and DEFUSE 3 came out and before release of the new U.S. acute stroke management guidelines (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24; doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158) that endorsed targeted thrombectomy for patients 6-24 hours out from their stroke onset, 278 (28%) of the registry patients underwent thrombectomy treatment during the 6- to 24-hour time window. In this subgroup, 34 patients underwent noncontrast CT to assess their infarcted core prior to thrombectomy, while the other patients underwent perfusion CT, MRI, or both. The noncontrast CT patients had recanalization rates, adverse event rates, and 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores comparable with those of patients assessed with more advanced imaging.

Based on this, “just looking at CT only seems reasonable. Noncontrast CT is a pretty valid way to select patients,” Dr. Nogueira said.

“This is the direction we should follow to simplify the paradigm for treating beyond 6 hours,” agreed Dr. Jovin, who also called for further advances in patient selection to expand the pool of patients who qualify for thrombectomy during the 6- to 24-hour postonset period.

“We want the DAWN results to be generalizable, to be simpler. We are exploring some more easily generalizable inclusion criteria that would allow us to treat more patients in more parts of the world,” Dr. Jovin added.

Both clinicians cited the remarkably low number needed to treat found in both DAWN and DEFUSE 3 of roughly three patients to produce one additional patient with a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in their 90-day mRS score, compared with controls, as an unmistakable sign that the treatment in both trials was too targeted.

“When we planned the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials we didn’t expect how powerful the treatment effect would be. There are probably other patients who could also benefit, so how low can we go? How liberal can we be in our inclusion criteria and still get benefit?” Dr. Jovin asked.

“When intravenous TPA [tissue plasminogen activator] first came out, we went by the book [for patient selection], but as we got to know the treatment and became more comfortable with it, we began to bend the rules. Now we’re at the point of getting comfortable with endovascular treatment, and we need to figure out where to bend the rules by building the database. There is no doubt that the rules need bending because of the treatment effect that we’ve seen. We need to get our patients to endovascular treatment,” she said in her presentation at the conference.

But these physicians realize that for the time being, standard of care will follow the imaging and data processing primarily used in DAWN and DEFUSE 3, which not only involved perfusion CT or MRI but also a proprietary, automated image processing software, RAPID, that takes imaging data and calculates the amount and ratio of infarcted core and hypoperfused, ischemic brain tissue.

“I asked our imaging experts [at the University of Cincinnati] what should my threshold be [for mismatch between the infarcted core and ischemic tissue], and they said, ‘Use the automated software,’ ” Dr. Khatri said. If centers managing acute ischemic stroke patients don’t already have this software, “they need it. I think there is no way around that. It’s the only way we’ll be able to do this,” she commented. Most U.S. community hospitals that admit stroke patients currently lack this software, largely because of its high cost, she added.

“We’re struggling because it is very difficult to get some community hospitals – primary stroke centers – to invest in the software, but that’s really the only way we’ll be able to do this. There are issues of cost, and of getting technicians trained,” she noted.

That’s because DEFUSE 3 enrolled patients with a baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of at least 6, while patients in DAWN required a score of at least 10, a loosening that allowed inclusion of 31 patients with scores of 6-9 in DEFUSE 3. Another, less restrictive criterion was the patient’s prestroke mRS score, which could have been 0-2 in DEFUSE 3 but could be only 0-1 in DAWN. Thirteen of the DEFUSE 3 patients had prestroke mRS scores of 2. DEFUSE 3 also had somewhat more liberal criteria for the size of a patient’s infarcted core at enrollment, with 41 patients who would have been excluded from DAWN because of an overly large infarcted core, Dr. Albers said in his presentation at the conference.

Currently, for patients presenting more than 16 hours following their stroke onset but within 24 hours, the DAWN enrollment criteria exclusively determine which patients should get thrombectomy.

One area where these rules could be bent is by a more thoughtful approach to the prestroke mRS score rule out, such as patients with orthopedic or rheumatic complications that limit mobility and give them an mRS score of 3. “We don’t have data for patients with back pain who can’t walk. I currently take these patients to endovascular therapy, and I’m sure many others do, too,” Dr. Khatri said.

Another potential way to grow the inclusion criteria is to investigate thrombectomy in patients with larger infarcted cores than were enrolled in DAWN and DEFUSE 3, but assessing this will require a new prospective study, Dr. Albers said.

Running the 6- to 24-hour numbers

Adoption of the 6- to 24-hour time window for endovascular intervention in selected patients means that suddenly the U.S. acute stroke infrastructure needs to accommodate a significantly increased number of patients. Just how many added patients this means is uncertain for the time being, and will vary from region to region and center to center. Dr. Albers roughly guessed that the new late time window might double the number of stroke patients undergoing thrombectomy at his center in Stanford. Dr. Khatri put together a more data-driven but still very speculative estimate that at the University of Cincinnati, it will mean about 40% more stroke patients going to thrombectomy. She shared the numbers behind this estimate in a report she gave at the conference.

To calculate the incremental change produced by the late time window, she used data collected on 2,297 acute ischemic stroke patients from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region who were seen at the University of Cincinnati during 2010. Prior analysis by Dr. Khatri and her associates showed that 159 of these patients presented quickly enough and with an appropriate stroke to qualify for thrombolytic therapy, and that 29 patients would have qualified for thrombectomy performed during the 0- to 6-hour time window.

In the new analysis Dr. Khatri calculated that 791 patients presented at 5-23 hours, and of these 34 had other features that would have made them eligible for enrollment in DAWN. Because no imaging data existed for these 2010 patients, she applied an estimate that 22% of these patients would qualify by the size of their infarcted core and ischemic penumbra, resulting in seven additional thrombectomy-eligible patients. Accounting for patients who would qualify by the more liberal DEFUSE 3 criteria added another 5 patients for a total increment of 12 patients during 2010 who would have been eligible for thrombectomy, about 40% of the number from the 0- to 6-hour window.

She noted that “this is likely an underestimate,” and “too small a sample to project to national estimates,” but concluded that “resources must be adapted to account for this increased volume in endovascular treatment.”

Dr. Khatri acknowledged that the new 6- to 24-hour window for endovascular therapy, and concerns about imaging delays in 0- to 6-hour patients, raise challenging issues regarding the message to give U.S. clinicians about treating acute ischemic stroke patients.

“We have a mandate to figure it out in every region. There is no doubt that stroke patients need access to this care. We need to become a lot more aggressive with endovascular treatment. It’s so gratifying to see the outcomes that we’re seeing,” Dr. Khatri said. “A lot of work is needed to accommodate endovascular therapy–eligible patients in an extended time window. We need more refined prehospital triage tools, we need to adequately implement imaging software, and we need increased capacity to perform endovascular treatment with additional procedure suites, operators, and ICU beds.”

Dr. Jovin has been a consultant to Anaconda Biomed, Blockade Medical, Cerenovus, FreeOx Biotech, and Silk Road Medical. Dr. Nogueira has received travel expense reimbursement from Stryker. Dr. Khatri has been a consultant to Biogen, Medpace/Novartis, and St. Jude; has received travel support from Neuravi and EmstoPA; and has received research support from Genentech, Lumosa, and Neurospring. Dr. Albers has an ownership interest in iSchemaView, the company that markets the RAPID imaging software, and is a consultant to iSchemaView and Medtronic.

LOS ANGELES – CT or magnetic resonance brain imaging of acute ischemic stroke patients was the key triage tool in two groundbreaking thrombectomy trials, DAWN and DEFUSE; results from both showed that patients found by imaging to have limited infarcted cores could safely benefit from endovascular thrombectomy, even when they are more than 6 hours out from their stroke onset, breaking the 6-hour barrier created 3 years ago by the first wave of thrombectomy trials.

But some stroke neurologists studying thrombectomy are now convinced that imaging is not needed and may actually harm acute ischemic stroke patients early on by introducing an unnecessary time delay when they present within the first 6 hours after stroke onset.

This new thinking on how to best use brain imaging in acute ischemic stroke patients is part of the rapid evolution of acute stroke management as experts process new data and refine their approach both within 6 hours of stroke onset and during the new treatment window of 6-24 hours post onset. The dramatic success achieved with thrombectomy in highly selected late-window patients prompted researchers to promote pushing the boundaries further to find less-selected late patients who could also potentially benefit from thrombectomy.

The downside of early imaging

“Early on, we have a mix of fast and slow progressors. Slow progressors are about a third to half the patients, so there is a lot of potential for [late] treatment, but the majority of patients during the first 6 hours after onset are fast progressors,” patients who won’t benefit from thrombectomy delivery beyond 6 hours, said Dr. Jovin, an interventional neurologist and director of the Stroke Institute of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

“Time is very precious in the 0- to 6-hour window. When we’re dealing with a lot of fast progressors, we pay a price [in added time to treatment] for any imaging we do. We need to understand that this is a real price we pay, even when CT takes perhaps 24 minutes, and MRI adds about 12 minutes. It’s not the case in all patients that doing CT angiography just adds 5 minutes. It can take 15, 20 minutes,” especially at centers that don’t treat these types of stroke patients day in and day out. “There is no question that imaging slows us down,” Dr. Jovin said.

He highlighted that “the main role of imaging is to exclude patients from treatment, a treatment that has unbelievable effects.” Imaging can rule out patients who have a hemorrhage, lack an occlusion, have a large infarcted core, or have none of the brain at risk or just a small amount, he noted. “Excluding hemorrhage is reasonable, but we can do that in the angiography suite, when the patient is on the table. The main benefit from advanced imaging is to more precisely define the core,” but for most patients the size of their core is not important because the vast majority of acute ischemic stroke patients seen within 6 hours of onset have cores smaller than 70 mL.

“Is this much ado about nothing – especially because we punish all the other patients [with smaller cores] who need to be treated [quickly] when we do additional imaging?” asked Dr. Jovin, who was one of the two lead investigators for the Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention With Trevo (DAWN) trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 4;378[1]:11-21). Another factor undercutting the value of imaging and determining core size is registry results that show patients who undergo thrombectomy with a large infarcted core are not harmed by treatment.

Current practice often uses imaging “to exclude the 20% of patients who may not have a large vessel occlusion or may not get benefit but whom we are unlikely to harm. But we harm the other 80% by delaying treatment by 30 minutes because of imaging. That’s why we need to rethink imaging and minimize its use.”

Dr. Jovin noted that at his center in Pittsburgh, the stroke institute staff began in 2013 to take patients transported from other stroke facilities and already diagnosed with a large vessel occlusion directly to the angiography suite, bypassing further brain imaging. By doing this, they cut their average door-to-groin puncture time down to 22 minutes from what had been an average of 81 minutes with imaging (Stroke. 2017 July;48[7]:1884-9). Right now the door-to-groin time is even lower, he added.

“Don’t waste time imaging,” said Dr. Nogueira, a stroke neurologist who is director of the neuroendovascular division of the Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center and professor of neurology, neurosurgery, and radiology at Emory University, both in Atlanta, as well as the second lead investigator for DAWN. “Time is crucial and trumps patient selection. Most selection criteria are informative rather than truly selective. It is important to understand that in every time window, we do not yet know who doesn’t benefit from treatment. Select faster, select less, and treat more” during the 0- to 6-hour window, he told his colleagues.

Expanding thrombectomy 6-24 hours after stroke onset

While Dr. Jovin and Dr. Nogueira called for more aggressive and less selective use of thrombectomy in patients who present within 6 hours of their stroke onset, they acknowledged that for patients who present during the 6- to 24-hour window, selection for thrombectomy should follow the rules applied in DAWN and in the more inclusive Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke (DEFUSE 3) trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 22;378:708-18). That means using imaging to confirm that the patient’s infarcted core is within the enrollment ceiling, but both neurologists also downplayed the need for the more sophisticated imaging approaches that were often used in both trials as well as in current routine practice at comprehensive stroke centers. They agreed that noncontrast CT, a widely available method, seems adequate for patient selection, based on the admittedly limited data available right now.

Dr. Nogueira cited data from the Trevo stent retriever registry, collected from nearly 1,000 U.S. acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent thrombectomy with this device. (Researchers at the conference reported updated registry data with nearly 2,000 patients with findings similar to what Dr. Nogueira referenced.) Although these patients underwent treatment before results of DAWN and DEFUSE 3 came out and before release of the new U.S. acute stroke management guidelines (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24; doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158) that endorsed targeted thrombectomy for patients 6-24 hours out from their stroke onset, 278 (28%) of the registry patients underwent thrombectomy treatment during the 6- to 24-hour time window. In this subgroup, 34 patients underwent noncontrast CT to assess their infarcted core prior to thrombectomy, while the other patients underwent perfusion CT, MRI, or both. The noncontrast CT patients had recanalization rates, adverse event rates, and 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores comparable with those of patients assessed with more advanced imaging.

Based on this, “just looking at CT only seems reasonable. Noncontrast CT is a pretty valid way to select patients,” Dr. Nogueira said.

“This is the direction we should follow to simplify the paradigm for treating beyond 6 hours,” agreed Dr. Jovin, who also called for further advances in patient selection to expand the pool of patients who qualify for thrombectomy during the 6- to 24-hour postonset period.

“We want the DAWN results to be generalizable, to be simpler. We are exploring some more easily generalizable inclusion criteria that would allow us to treat more patients in more parts of the world,” Dr. Jovin added.

Both clinicians cited the remarkably low number needed to treat found in both DAWN and DEFUSE 3 of roughly three patients to produce one additional patient with a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in their 90-day mRS score, compared with controls, as an unmistakable sign that the treatment in both trials was too targeted.

“When we planned the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials we didn’t expect how powerful the treatment effect would be. There are probably other patients who could also benefit, so how low can we go? How liberal can we be in our inclusion criteria and still get benefit?” Dr. Jovin asked.

“When intravenous TPA [tissue plasminogen activator] first came out, we went by the book [for patient selection], but as we got to know the treatment and became more comfortable with it, we began to bend the rules. Now we’re at the point of getting comfortable with endovascular treatment, and we need to figure out where to bend the rules by building the database. There is no doubt that the rules need bending because of the treatment effect that we’ve seen. We need to get our patients to endovascular treatment,” she said in her presentation at the conference.

But these physicians realize that for the time being, standard of care will follow the imaging and data processing primarily used in DAWN and DEFUSE 3, which not only involved perfusion CT or MRI but also a proprietary, automated image processing software, RAPID, that takes imaging data and calculates the amount and ratio of infarcted core and hypoperfused, ischemic brain tissue.

“I asked our imaging experts [at the University of Cincinnati] what should my threshold be [for mismatch between the infarcted core and ischemic tissue], and they said, ‘Use the automated software,’ ” Dr. Khatri said. If centers managing acute ischemic stroke patients don’t already have this software, “they need it. I think there is no way around that. It’s the only way we’ll be able to do this,” she commented. Most U.S. community hospitals that admit stroke patients currently lack this software, largely because of its high cost, she added.

“We’re struggling because it is very difficult to get some community hospitals – primary stroke centers – to invest in the software, but that’s really the only way we’ll be able to do this. There are issues of cost, and of getting technicians trained,” she noted.

That’s because DEFUSE 3 enrolled patients with a baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of at least 6, while patients in DAWN required a score of at least 10, a loosening that allowed inclusion of 31 patients with scores of 6-9 in DEFUSE 3. Another, less restrictive criterion was the patient’s prestroke mRS score, which could have been 0-2 in DEFUSE 3 but could be only 0-1 in DAWN. Thirteen of the DEFUSE 3 patients had prestroke mRS scores of 2. DEFUSE 3 also had somewhat more liberal criteria for the size of a patient’s infarcted core at enrollment, with 41 patients who would have been excluded from DAWN because of an overly large infarcted core, Dr. Albers said in his presentation at the conference.

Currently, for patients presenting more than 16 hours following their stroke onset but within 24 hours, the DAWN enrollment criteria exclusively determine which patients should get thrombectomy.

One area where these rules could be bent is by a more thoughtful approach to the prestroke mRS score rule out, such as patients with orthopedic or rheumatic complications that limit mobility and give them an mRS score of 3. “We don’t have data for patients with back pain who can’t walk. I currently take these patients to endovascular therapy, and I’m sure many others do, too,” Dr. Khatri said.

Another potential way to grow the inclusion criteria is to investigate thrombectomy in patients with larger infarcted cores than were enrolled in DAWN and DEFUSE 3, but assessing this will require a new prospective study, Dr. Albers said.

Running the 6- to 24-hour numbers

Adoption of the 6- to 24-hour time window for endovascular intervention in selected patients means that suddenly the U.S. acute stroke infrastructure needs to accommodate a significantly increased number of patients. Just how many added patients this means is uncertain for the time being, and will vary from region to region and center to center. Dr. Albers roughly guessed that the new late time window might double the number of stroke patients undergoing thrombectomy at his center in Stanford. Dr. Khatri put together a more data-driven but still very speculative estimate that at the University of Cincinnati, it will mean about 40% more stroke patients going to thrombectomy. She shared the numbers behind this estimate in a report she gave at the conference.

To calculate the incremental change produced by the late time window, she used data collected on 2,297 acute ischemic stroke patients from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region who were seen at the University of Cincinnati during 2010. Prior analysis by Dr. Khatri and her associates showed that 159 of these patients presented quickly enough and with an appropriate stroke to qualify for thrombolytic therapy, and that 29 patients would have qualified for thrombectomy performed during the 0- to 6-hour time window.

In the new analysis Dr. Khatri calculated that 791 patients presented at 5-23 hours, and of these 34 had other features that would have made them eligible for enrollment in DAWN. Because no imaging data existed for these 2010 patients, she applied an estimate that 22% of these patients would qualify by the size of their infarcted core and ischemic penumbra, resulting in seven additional thrombectomy-eligible patients. Accounting for patients who would qualify by the more liberal DEFUSE 3 criteria added another 5 patients for a total increment of 12 patients during 2010 who would have been eligible for thrombectomy, about 40% of the number from the 0- to 6-hour window.

She noted that “this is likely an underestimate,” and “too small a sample to project to national estimates,” but concluded that “resources must be adapted to account for this increased volume in endovascular treatment.”

Dr. Khatri acknowledged that the new 6- to 24-hour window for endovascular therapy, and concerns about imaging delays in 0- to 6-hour patients, raise challenging issues regarding the message to give U.S. clinicians about treating acute ischemic stroke patients.

“We have a mandate to figure it out in every region. There is no doubt that stroke patients need access to this care. We need to become a lot more aggressive with endovascular treatment. It’s so gratifying to see the outcomes that we’re seeing,” Dr. Khatri said. “A lot of work is needed to accommodate endovascular therapy–eligible patients in an extended time window. We need more refined prehospital triage tools, we need to adequately implement imaging software, and we need increased capacity to perform endovascular treatment with additional procedure suites, operators, and ICU beds.”

Dr. Jovin has been a consultant to Anaconda Biomed, Blockade Medical, Cerenovus, FreeOx Biotech, and Silk Road Medical. Dr. Nogueira has received travel expense reimbursement from Stryker. Dr. Khatri has been a consultant to Biogen, Medpace/Novartis, and St. Jude; has received travel support from Neuravi and EmstoPA; and has received research support from Genentech, Lumosa, and Neurospring. Dr. Albers has an ownership interest in iSchemaView, the company that markets the RAPID imaging software, and is a consultant to iSchemaView and Medtronic.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ISC 2018

VIDEO: Stroke benefits from stem cells maintained for 2 years

LOS ANGELES – , Gary K. Steinberg, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Seeing sustained benefit out to 2 years was “quite surprising. We thought we’d lose the benefit,” Dr. Steinberg said in a video interview.

The findings “change our notion of what happens after a stroke. The damaged circuits can be resurrected,” said Dr. Steinberg, professor and chair of neurosurgery at Stanford (Calif.) University.

He reported long-term follow-up data for 18 chronic stroke patients who had received transplantation of allogeneic bone marrow–derived stem cells. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint, at 6 months after treatment, showed clinically meaningful improvements in several measures of stroke disability and function in 13 of the 18 patients (72%), including a rise of at least 10 points in the Fugl-Meyer total motor function score.

His new report on 2-year follow-up showed that these 6-month improvements continued. The average increase in Fugl-Meyer score over baseline was about 18 points at 6, 12, and 24 months of follow-up.

Based on the promise shown in this pilot study, Dr. Steinberg and his associates are running a randomized study with 156 patients. Enrollment recently completed, and the results should be available during the second half of 2019, Dr. Steinberg said.

SanBio funded the study. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant or advisor to Qool Therapeutics, Peter Lazic US, and NeuroSave.

SOURCE: Steinberg K et al. International Stroke Conference 2018, Abstract LB14.

LOS ANGELES – , Gary K. Steinberg, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Seeing sustained benefit out to 2 years was “quite surprising. We thought we’d lose the benefit,” Dr. Steinberg said in a video interview.

The findings “change our notion of what happens after a stroke. The damaged circuits can be resurrected,” said Dr. Steinberg, professor and chair of neurosurgery at Stanford (Calif.) University.

He reported long-term follow-up data for 18 chronic stroke patients who had received transplantation of allogeneic bone marrow–derived stem cells. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint, at 6 months after treatment, showed clinically meaningful improvements in several measures of stroke disability and function in 13 of the 18 patients (72%), including a rise of at least 10 points in the Fugl-Meyer total motor function score.

His new report on 2-year follow-up showed that these 6-month improvements continued. The average increase in Fugl-Meyer score over baseline was about 18 points at 6, 12, and 24 months of follow-up.

Based on the promise shown in this pilot study, Dr. Steinberg and his associates are running a randomized study with 156 patients. Enrollment recently completed, and the results should be available during the second half of 2019, Dr. Steinberg said.

SanBio funded the study. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant or advisor to Qool Therapeutics, Peter Lazic US, and NeuroSave.

SOURCE: Steinberg K et al. International Stroke Conference 2018, Abstract LB14.

LOS ANGELES – , Gary K. Steinberg, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Seeing sustained benefit out to 2 years was “quite surprising. We thought we’d lose the benefit,” Dr. Steinberg said in a video interview.

The findings “change our notion of what happens after a stroke. The damaged circuits can be resurrected,” said Dr. Steinberg, professor and chair of neurosurgery at Stanford (Calif.) University.

He reported long-term follow-up data for 18 chronic stroke patients who had received transplantation of allogeneic bone marrow–derived stem cells. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint, at 6 months after treatment, showed clinically meaningful improvements in several measures of stroke disability and function in 13 of the 18 patients (72%), including a rise of at least 10 points in the Fugl-Meyer total motor function score.

His new report on 2-year follow-up showed that these 6-month improvements continued. The average increase in Fugl-Meyer score over baseline was about 18 points at 6, 12, and 24 months of follow-up.

Based on the promise shown in this pilot study, Dr. Steinberg and his associates are running a randomized study with 156 patients. Enrollment recently completed, and the results should be available during the second half of 2019, Dr. Steinberg said.

SanBio funded the study. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant or advisor to Qool Therapeutics, Peter Lazic US, and NeuroSave.

SOURCE: Steinberg K et al. International Stroke Conference 2018, Abstract LB14.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2018

Key clinical point: The stroke benefits from cell transplantation continued during 2-year follow-up.

Major finding: Among 18 treated patients, 13 (72%) had a sustained, clinically meaningful rise in their total motor function score.

Study details: Review of 18 patients who received intracranial cell transplantations at two U.S. sites.

Disclosures: SanBio funded the study. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant or adviser to Qool Therapeutics, Peter Lazic US, and NeuroSave.

Source: Steinberg K et al. International Stroke Conference 2018, Abstract LB14.

EMS stroke field triage improves outcomes

LOS ANGELES – An emergency medical services protocol to identify large vessel occlusions and deliver patients to a comprehensive stroke center if it is within 30 minutes of travel time reduced the time to recanalization when compared against a separate protocol that optimized transfer of such patients from primary to comprehensive stroke centers.

The findings, which come from a sequential study conducted in an urban Rhode Island region, offer evidence to resolve the controversy over whether field triage in emergency medical services (EMS) units will improve outcomes, because field stroke severity scores won’t always be accurate, and longer travel to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) could delay treatment to a patient who doesn’t need thrombectomy.

The region where the study was carried out has one CSC and eight primary stroke centers (PSCs). The large vessel occlusions transfer protocol instructed PSCs to contact the CSC when a patient scored 4 or 5 on the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS), followed by CT and CT angiography. They then shared the resulting images with the CSC, which could make a decision whether to transfer the patient.

The field-based protocol relied on a LAMS score assessment by EMS personnel. Patients scoring 4 or 5 would then be delivered to the CSC if it was within 30 minutes from their current location. Patients scoring less than 4 would be brought to the nearest facility. In cases when the field LAMS score was 4 or greater and the nearest CSC was more than 30 miles away, EMS personnel were instructed to travel to the closest PSC, but immediately send word of an inbound patient that might need a transfer to a CSC. In those cases, the PSC’s goal was to get images to the CSC for review within 45 minutes. The protocol was executed out to 24 hours after the patient was last known well.

Even in patients who were closer to a PSC than a CSC, process outcomes were better with the field triage protocol. “Despite 8 additional minutes of transport time, IV TPA was given 17 minutes earlier, and recanalization occurred almost an hour earlier,” said Dr. McTaggart. “That would indicate that perhaps even a 30-minute window is too conservative of a protocol, because the number needed to treat for mechanical thrombectomy is 2 or 3, so you have this tremendously powerful treatment effect for these patients. If you can get it to them an hour earlier, it’s a no-brainer to me that they need to go to the right place the first time,” he said.

Instituting the changes was no picnic. Dr. McTaggart spent thousands of hours working with EMS personnel and emergency department physicians at PSCs. “It’s a lot of work, but the downstream gains are huge, not only from a disability standpoint for patients but for the economics of the health care system. We’re potentially saving patients from disability health care costs,” he said.

The study population included consecutive stroke patients in the region whose first contact was with EMS personnel during three time periods: before either change was made: (pre PSC-CSC transfer optimization, pre field triage, July 2015 to January 2016), after PSC optimization but only voluntary field triage (January 2016 to January 2017), and when both PSC optimization and field triage were mandatory (January 2017 to January 2018).

The patients had an anterior large vessel occlusion and mild to moderate early ischemic change. Outcomes included time from hospital arrival (PSC or CSC) to alteplase treatment, arterial puncture, and recanalization. Clinical measures included favorable outcomes (modified Rankin scale score 0-2) at 90 days, or discharge with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 4 or less, in cases where 90-day follow-up did not occur.

A total of 38 patients were seen before any change, 100 after PSC optimization, and 94 after both PSC optimization and field triage were implemented. A Google Maps analysis showed that the median additional time required to travel to a CSC instead of a PSC was 8 minutes (interquartile range 4-12).

The time to first use of IV alteplase dropped from 54 minutes before any change to 49 minutes after PSC optimization, and 36 minutes after both PSC optimization and field triage. Similar drops were seen in time to arterial puncture (105 minutes, 101 minutes, 88 minutes) and time to recanalization (156 minutes, 132 minutes, 116 minutes). These differences did not reach statistical significance.

The clinical outcomes also became more favorable: 58% had a favorable outcome at 90 days with both protocols in place, compared with 51% with only PSC optimization and 31% before any changes (P = .049 for 31% to 58% comparison).

The researchers conducted a subanalysis of 150 patients for whom the PSC was closest. Of these, 94 went to a CSC and 56 went to a PSC. The elapsed time between EMS leaving the scene with the patient aboard and IV TPA treatment was an average of 51 minutes in patients taken to the CSC, compared with 68 minutes in patients taken to PSCs (P = .012). The time to arterial puncture was also shorter (98 minutes versus 155 minutes; P less than .001), as was time to recanalization (131 minutes versus 174 minutes; P less than .001).

CSC patients were more likely to have a favorable outcome (65% versus 42%; P = .01).

The study received no external funding. Dr. McTaggart reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jayaraman M et al. ISC 2018 Abstract 95 (Stroke. 2018 Jan;49[Suppl 1]:A95)

LOS ANGELES – An emergency medical services protocol to identify large vessel occlusions and deliver patients to a comprehensive stroke center if it is within 30 minutes of travel time reduced the time to recanalization when compared against a separate protocol that optimized transfer of such patients from primary to comprehensive stroke centers.

The findings, which come from a sequential study conducted in an urban Rhode Island region, offer evidence to resolve the controversy over whether field triage in emergency medical services (EMS) units will improve outcomes, because field stroke severity scores won’t always be accurate, and longer travel to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) could delay treatment to a patient who doesn’t need thrombectomy.

The region where the study was carried out has one CSC and eight primary stroke centers (PSCs). The large vessel occlusions transfer protocol instructed PSCs to contact the CSC when a patient scored 4 or 5 on the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS), followed by CT and CT angiography. They then shared the resulting images with the CSC, which could make a decision whether to transfer the patient.

The field-based protocol relied on a LAMS score assessment by EMS personnel. Patients scoring 4 or 5 would then be delivered to the CSC if it was within 30 minutes from their current location. Patients scoring less than 4 would be brought to the nearest facility. In cases when the field LAMS score was 4 or greater and the nearest CSC was more than 30 miles away, EMS personnel were instructed to travel to the closest PSC, but immediately send word of an inbound patient that might need a transfer to a CSC. In those cases, the PSC’s goal was to get images to the CSC for review within 45 minutes. The protocol was executed out to 24 hours after the patient was last known well.

Even in patients who were closer to a PSC than a CSC, process outcomes were better with the field triage protocol. “Despite 8 additional minutes of transport time, IV TPA was given 17 minutes earlier, and recanalization occurred almost an hour earlier,” said Dr. McTaggart. “That would indicate that perhaps even a 30-minute window is too conservative of a protocol, because the number needed to treat for mechanical thrombectomy is 2 or 3, so you have this tremendously powerful treatment effect for these patients. If you can get it to them an hour earlier, it’s a no-brainer to me that they need to go to the right place the first time,” he said.

Instituting the changes was no picnic. Dr. McTaggart spent thousands of hours working with EMS personnel and emergency department physicians at PSCs. “It’s a lot of work, but the downstream gains are huge, not only from a disability standpoint for patients but for the economics of the health care system. We’re potentially saving patients from disability health care costs,” he said.

The study population included consecutive stroke patients in the region whose first contact was with EMS personnel during three time periods: before either change was made: (pre PSC-CSC transfer optimization, pre field triage, July 2015 to January 2016), after PSC optimization but only voluntary field triage (January 2016 to January 2017), and when both PSC optimization and field triage were mandatory (January 2017 to January 2018).

The patients had an anterior large vessel occlusion and mild to moderate early ischemic change. Outcomes included time from hospital arrival (PSC or CSC) to alteplase treatment, arterial puncture, and recanalization. Clinical measures included favorable outcomes (modified Rankin scale score 0-2) at 90 days, or discharge with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 4 or less, in cases where 90-day follow-up did not occur.

A total of 38 patients were seen before any change, 100 after PSC optimization, and 94 after both PSC optimization and field triage were implemented. A Google Maps analysis showed that the median additional time required to travel to a CSC instead of a PSC was 8 minutes (interquartile range 4-12).

The time to first use of IV alteplase dropped from 54 minutes before any change to 49 minutes after PSC optimization, and 36 minutes after both PSC optimization and field triage. Similar drops were seen in time to arterial puncture (105 minutes, 101 minutes, 88 minutes) and time to recanalization (156 minutes, 132 minutes, 116 minutes). These differences did not reach statistical significance.

The clinical outcomes also became more favorable: 58% had a favorable outcome at 90 days with both protocols in place, compared with 51% with only PSC optimization and 31% before any changes (P = .049 for 31% to 58% comparison).

The researchers conducted a subanalysis of 150 patients for whom the PSC was closest. Of these, 94 went to a CSC and 56 went to a PSC. The elapsed time between EMS leaving the scene with the patient aboard and IV TPA treatment was an average of 51 minutes in patients taken to the CSC, compared with 68 minutes in patients taken to PSCs (P = .012). The time to arterial puncture was also shorter (98 minutes versus 155 minutes; P less than .001), as was time to recanalization (131 minutes versus 174 minutes; P less than .001).

CSC patients were more likely to have a favorable outcome (65% versus 42%; P = .01).

The study received no external funding. Dr. McTaggart reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jayaraman M et al. ISC 2018 Abstract 95 (Stroke. 2018 Jan;49[Suppl 1]:A95)

LOS ANGELES – An emergency medical services protocol to identify large vessel occlusions and deliver patients to a comprehensive stroke center if it is within 30 minutes of travel time reduced the time to recanalization when compared against a separate protocol that optimized transfer of such patients from primary to comprehensive stroke centers.

The findings, which come from a sequential study conducted in an urban Rhode Island region, offer evidence to resolve the controversy over whether field triage in emergency medical services (EMS) units will improve outcomes, because field stroke severity scores won’t always be accurate, and longer travel to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) could delay treatment to a patient who doesn’t need thrombectomy.

The region where the study was carried out has one CSC and eight primary stroke centers (PSCs). The large vessel occlusions transfer protocol instructed PSCs to contact the CSC when a patient scored 4 or 5 on the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS), followed by CT and CT angiography. They then shared the resulting images with the CSC, which could make a decision whether to transfer the patient.

The field-based protocol relied on a LAMS score assessment by EMS personnel. Patients scoring 4 or 5 would then be delivered to the CSC if it was within 30 minutes from their current location. Patients scoring less than 4 would be brought to the nearest facility. In cases when the field LAMS score was 4 or greater and the nearest CSC was more than 30 miles away, EMS personnel were instructed to travel to the closest PSC, but immediately send word of an inbound patient that might need a transfer to a CSC. In those cases, the PSC’s goal was to get images to the CSC for review within 45 minutes. The protocol was executed out to 24 hours after the patient was last known well.

Even in patients who were closer to a PSC than a CSC, process outcomes were better with the field triage protocol. “Despite 8 additional minutes of transport time, IV TPA was given 17 minutes earlier, and recanalization occurred almost an hour earlier,” said Dr. McTaggart. “That would indicate that perhaps even a 30-minute window is too conservative of a protocol, because the number needed to treat for mechanical thrombectomy is 2 or 3, so you have this tremendously powerful treatment effect for these patients. If you can get it to them an hour earlier, it’s a no-brainer to me that they need to go to the right place the first time,” he said.

Instituting the changes was no picnic. Dr. McTaggart spent thousands of hours working with EMS personnel and emergency department physicians at PSCs. “It’s a lot of work, but the downstream gains are huge, not only from a disability standpoint for patients but for the economics of the health care system. We’re potentially saving patients from disability health care costs,” he said.

The study population included consecutive stroke patients in the region whose first contact was with EMS personnel during three time periods: before either change was made: (pre PSC-CSC transfer optimization, pre field triage, July 2015 to January 2016), after PSC optimization but only voluntary field triage (January 2016 to January 2017), and when both PSC optimization and field triage were mandatory (January 2017 to January 2018).

The patients had an anterior large vessel occlusion and mild to moderate early ischemic change. Outcomes included time from hospital arrival (PSC or CSC) to alteplase treatment, arterial puncture, and recanalization. Clinical measures included favorable outcomes (modified Rankin scale score 0-2) at 90 days, or discharge with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 4 or less, in cases where 90-day follow-up did not occur.

A total of 38 patients were seen before any change, 100 after PSC optimization, and 94 after both PSC optimization and field triage were implemented. A Google Maps analysis showed that the median additional time required to travel to a CSC instead of a PSC was 8 minutes (interquartile range 4-12).

The time to first use of IV alteplase dropped from 54 minutes before any change to 49 minutes after PSC optimization, and 36 minutes after both PSC optimization and field triage. Similar drops were seen in time to arterial puncture (105 minutes, 101 minutes, 88 minutes) and time to recanalization (156 minutes, 132 minutes, 116 minutes). These differences did not reach statistical significance.

The clinical outcomes also became more favorable: 58% had a favorable outcome at 90 days with both protocols in place, compared with 51% with only PSC optimization and 31% before any changes (P = .049 for 31% to 58% comparison).

The researchers conducted a subanalysis of 150 patients for whom the PSC was closest. Of these, 94 went to a CSC and 56 went to a PSC. The elapsed time between EMS leaving the scene with the patient aboard and IV TPA treatment was an average of 51 minutes in patients taken to the CSC, compared with 68 minutes in patients taken to PSCs (P = .012). The time to arterial puncture was also shorter (98 minutes versus 155 minutes; P less than .001), as was time to recanalization (131 minutes versus 174 minutes; P less than .001).

CSC patients were more likely to have a favorable outcome (65% versus 42%; P = .01).

The study received no external funding. Dr. McTaggart reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jayaraman M et al. ISC 2018 Abstract 95 (Stroke. 2018 Jan;49[Suppl 1]:A95)

REPORTING FROM ISC 2018

Key clinical point: EMS field triage may improve stroke patient management.

Major finding: Even when a primary stroke center was closer, the time to recanalization was shortened by 43 minutes when patients were taken to a comprehensive stroke center instead.

Data source: Prospective study of 232 consecutive stroke patients.

Disclosures: The study received no external funding. Dr. McTaggart reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Jayaraman M et al. ISC 2018 Abstract 95 (Stroke. 2018 Jan;49[Suppl 1]:A95)

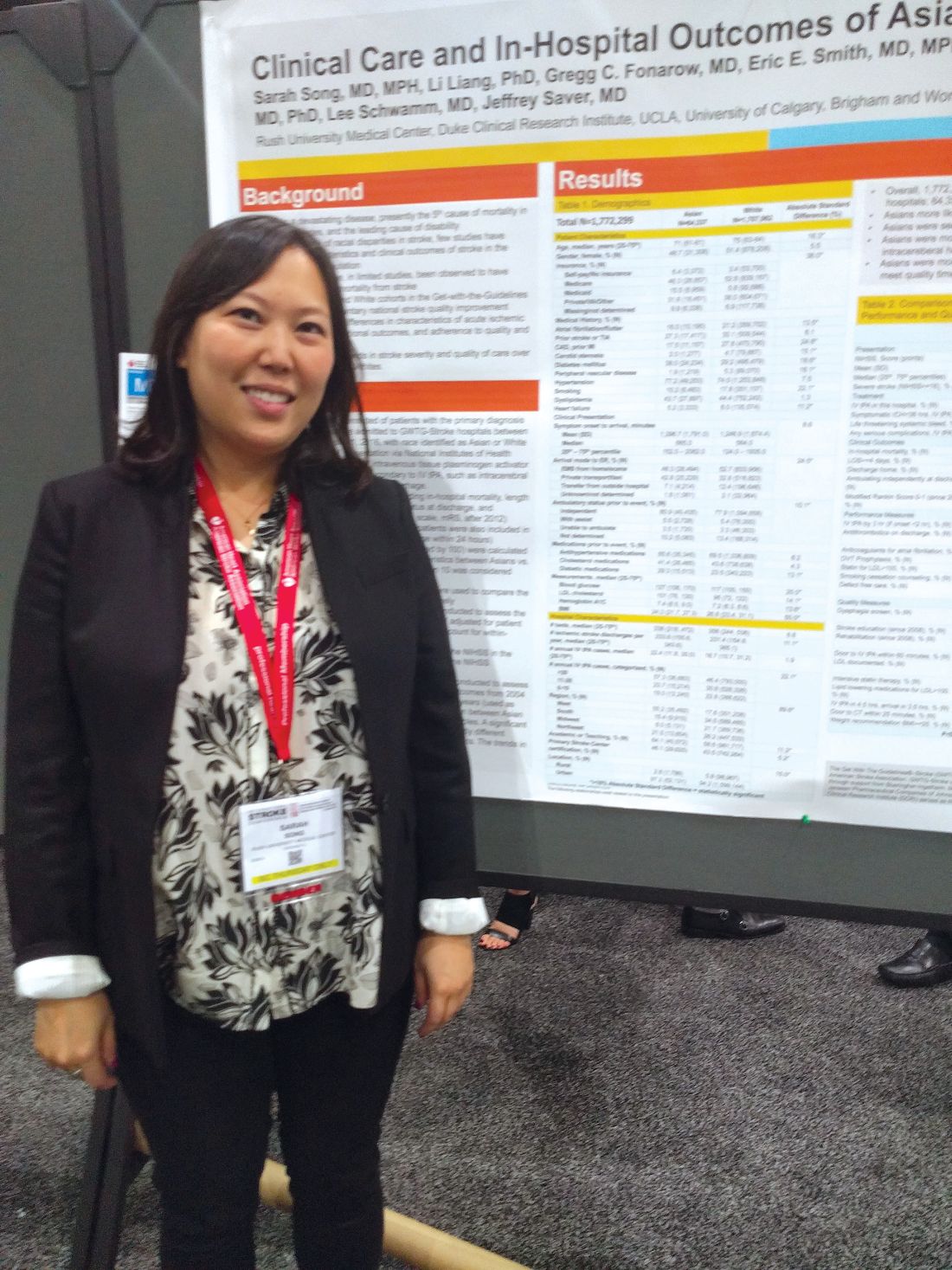

Survey highlights challenges in Asian American stroke patients

LOS ANGELES – A large survey of Asian Americans suggests that the group experiences more severe ischemic strokes and is less likely to receive intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) than do white patients, among other discrepancies. The research found that whites had declining stroke severity between 2004 and 2016, but there was no change in Asian Americans.

The research encompasses all self-identified Asian Americans in the Get-with-the-Guidelines stroke database, which is a voluntary stroke quality improvement program begun by the American Heart Association in 2003. The analysis included 64,337 Asian Americans and 1,707,962 white Americans at 2,171 hospitals nationwide that participated in the program during 2004-2016.