User login

Mixed CRC screening messaging. Confusing? Some docs think so

Recently updated colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidance from the American College of Physicians is raising concerns among some specialists.

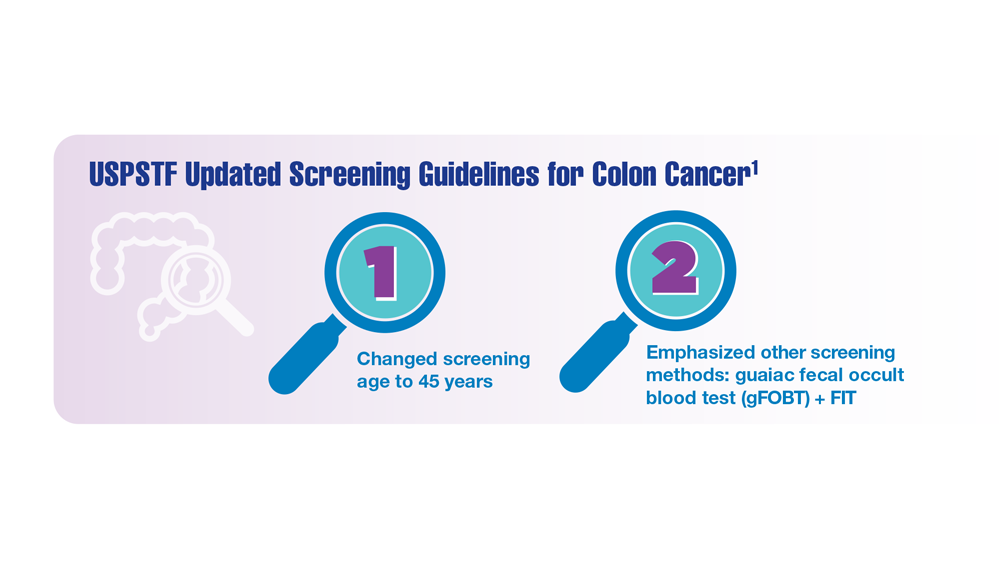

The ACP’s clinical guidance, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, called for CRC screenings to start at age 50 in average-risk individuals who are asymptomatic. This recommendation, however, conflicts with guidelines from the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which, in 2021, officially lowered the recommended initial age of screening to 45.

Following the ACP’s announcement, several professional organizations, such as the American College of Radiology, criticized the new guidelines, calling them “a step backward” and warning they may hinder recent gains against CRC.

Some physicians believe the discordance will confuse patients and lead to varying referral practices among primary care physicians. And while insurers will likely continue to pay for screening procedures based on the USPSTF guidelines, which dictate insurance coverage, some physicians worry that insurers could create additional roadblocks for CRC screening coverage, such as requiring prior authorization.

“We’re in a conflicted space on this issue as a country,” said John L. Marshall, MD, a GI oncologist and director of The Ruesch Center for the Cure of GI Cancers at Georgetown University, Washington.

Ultimately, the physician community wants an inexpensive screening test that’s effective at preventing cancer and deaths, but the evidence thus far doesn’t necessarily support colonoscopy as that test, said Dr. Marshall, also chief medical officer for Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Although colonoscopy can prevent CRC by removing precancerous polyps and can reduce deaths from cancer, it has not been shown to lower all-cause mortality, Dr. Marshall explained. A recent meta-analysis, for example, found that, aside from sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, no other cancer screening modalities meaningfully changed life expectancy.

“That’s why we’re struggling,” Dr. Marshall said. “We’re emotionally invested in having screening available to younger people because we’re seeing colon cancer in younger people. So, we want it to move earlier, but it’s expensive and it’s invasive.”

Docs debate differing guidance

The new ACP guidance, based on a critical review of existing guidelines, evidence, and modeling studies, argues that the potential harms of screening average-risk individuals under age 50 may outweigh the potential benefits.

The benefits of screening, of course, include identifying and removing precancerous lesions or localized cancer, while the potential harms include false positives that may lead to unnecessary additional tests, treatments, and costs. More invasive screening procedures, such as colonoscopy, can also come with their own risks, including serious bleeding and perforation.

For colonoscopy, for instance, the ACP team determined that starting screening at age 45 vs. 50 could prevent three additional CRC cases per 1,000 individuals screened (58 vs. 61) and one CRC death (27 vs. 28) over the recommended screening time frame. On the flip side, screening starting at age 45 could increase the incidence of gastrointestinal or cardiovascular events (14 vs. 16).

“Even if we assumed the modeling study had no limitations and accepted the results at face value, we would conclude that the small estimated benefits and harms roughly balance each other out, resulting in an inadequate net benefit to warrant CRC screening in average-risk adults aged 45 to 49 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, and ACP coauthors write.

Family physician Kenny Lin, MD, MPH, believes the updated ACP guidelines are reasonable, and points out the ACP is not the first group to disagree with the USPSTF’s recommendations.

“I think the [ACP] guidelines make a lot of sense,” said Dr. Lin, who practices in Lancaster, Pa. The American Academy of Family Physicians “also did not endorse the recommendations to start screenings at 45.” In its 2021 updated guidance, the AAFP recommended screening for CRC starting at age 50, concluding there was “insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening” in the 45 to 49 population.

However, Jason R. Woloski, MD, a family physician based in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., expressed concern that the differing guidelines will confuse patients as well as present challenges for primary care physicians.

“I feel like we took the last couple of years convincing people that earlier is better,” said Dr. Woloski, an associate professor of family medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Scranton, Pa. “It can send a mixed message to a patient after we’ve been stressing the importance of earlier [screening], and then saying, ‘Maybe we got it wrong; maybe we were okay the first time.’ ”

Mark A. Lewis, MD, a GI oncologist, had a similar initial reaction upon hearing about the updated guidelines: “The lack of synchronization across groups is going to create confusion among patients.”

Although he could not say definitively whether the recommendations will affect GI oncologists, because he only sees patients with advanced CRC, he does see the demands in primary care and gastroenterology shifting.

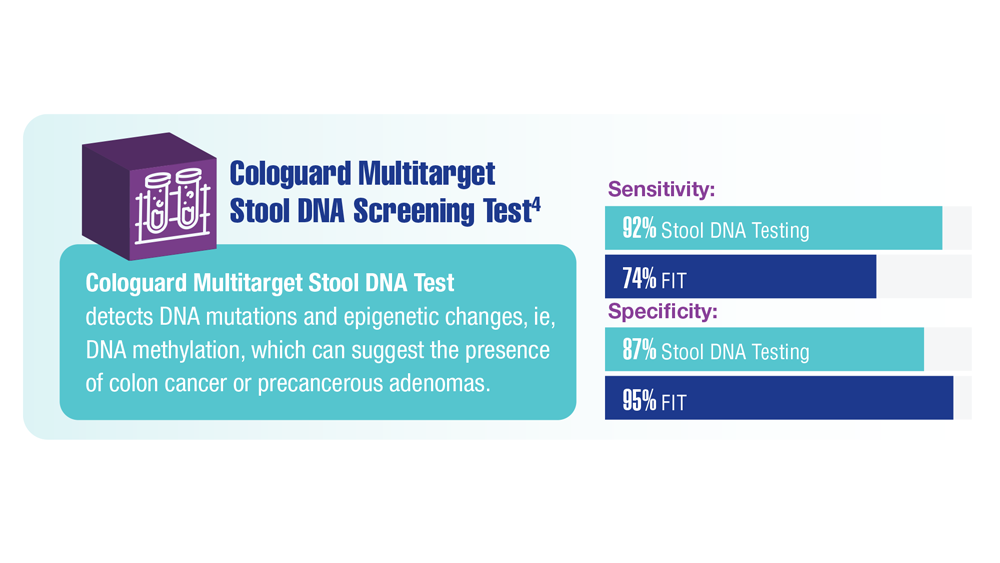

“I think the much bigger impact will be on primary care physicians and gastroenterologists,” said Dr. Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Healthcare in Murray, Utah. “My best guess is that the procedural burden on the latter will be mitigated by more stool testing ordered by primary care physicians. Patients may understandably prefer the convenience and lack of invasiveness of home-based fecal testing, but a positive FIT [fecal immunochemical test] without a follow-up scope is an incomplete screening.”

Dr. Marshall, however, had a different take. He does not envision the updated guidelines having much of a practical impact on physician practice. Most of the country is already not receiving proper colon cancer screenings, he said. Research shows more than 40% of Americans skip standard CRC screenings. Even anecdotally, he noted, friends in their 60s come to him and admit they haven’t had a colonoscopy yet.

Potential impact on patient outcomes, costs

Beyond mixed messaging, some experts worry that pushing CRC screening later could mean cancers are caught later, when they’re more advanced.

Finding cancers earlier, when they are easier and less expensive to treat, make earlier CRC screenings worthwhile, Dr. Woloski explained.

Dr. Lewis sees earlier screening as a way to stop a tumor from progressing before it can really pick up steam.

“To me the biggest advantage of colonoscopy is the interruption of the adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence, whereby a polyp that is completely removed cannot become an invasive adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Lewis said. “We’ve also had evidence for well over a decade that flexible sigmoidoscopy, which doesn’t come close to visualizing the entire colon, can confer a survival benefit.”

Another concern is the potential effect on insurance coverage.

Medicare and other insurers use USPSTF guidelines to make coverage decisions. However, because of this mixed message, Dr. Woloski questioned whether there would be more challenges regarding insurance coverage. “Does it mean primary care doctors are going to have to preauthorize a lot of these screenings even if you have shared decision-making with the patient?” he asked.

When it comes to screening referrals, Douglas A. Corley, MD, PhD, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente in northern California, said it’s critical for primary care physicians to educate patients about the differing views on screening benefits and harms as well as the different screening options.

“Given the different opinions, it is important to let people in this age group know that screening is an option recommended by some groups,” Dr. Corley said. “Colorectal cancer screening is very effective for decreasing the risk for death from colorectal cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Making sure all eligible people know this is an option provides the best way for patients to have an informed choice.”

Dr. Lin has already begun talking with patients about the differing recommendations. He said it’s helpful to simplify the issue and focus the conversation on what patients value most. For more assertive patients whose priority is finding every possible cancer early, starting screenings at age 45 may be reasonable, he said, whereas other patients may not find the process or possible side effects worth it.

“And then you have the middle group that decides, ‘Yes, I want to start at 45, but I want the fecal test. I don’t want to just jump into colonoscopy.’ ” Dr. Lin said. “That would be kind of a compromise where you’d be starting screening earlier, but not subjecting yourself to something that has more potential for harms.”

Dr. Woloski said he plans to continue making referrals based on the USPSTF recommendations.

“With every screening, it is about informed decision-making with the patient, but I think for now, since USPSTF still supports the earlier screening, I will probably stick with offering it earlier,” he said.

But when deciding on the appropriate timing for evaluating CRC, the most important distinction is between screening and diagnosis, Dr. Lewis added.

“The former is only appropriate in patients who are truly asymptomatic and who are truly average-risk,” he said. “The latter is critical in any patient with symptoms. I cannot count the number of times I have seen blood in the stool discounted as hemorrhoids without even an exam, digital rectal, or scope, to demonstrate that hemorrhoids are present and the culprit for blood loss.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recently updated colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidance from the American College of Physicians is raising concerns among some specialists.

The ACP’s clinical guidance, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, called for CRC screenings to start at age 50 in average-risk individuals who are asymptomatic. This recommendation, however, conflicts with guidelines from the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which, in 2021, officially lowered the recommended initial age of screening to 45.

Following the ACP’s announcement, several professional organizations, such as the American College of Radiology, criticized the new guidelines, calling them “a step backward” and warning they may hinder recent gains against CRC.

Some physicians believe the discordance will confuse patients and lead to varying referral practices among primary care physicians. And while insurers will likely continue to pay for screening procedures based on the USPSTF guidelines, which dictate insurance coverage, some physicians worry that insurers could create additional roadblocks for CRC screening coverage, such as requiring prior authorization.

“We’re in a conflicted space on this issue as a country,” said John L. Marshall, MD, a GI oncologist and director of The Ruesch Center for the Cure of GI Cancers at Georgetown University, Washington.

Ultimately, the physician community wants an inexpensive screening test that’s effective at preventing cancer and deaths, but the evidence thus far doesn’t necessarily support colonoscopy as that test, said Dr. Marshall, also chief medical officer for Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Although colonoscopy can prevent CRC by removing precancerous polyps and can reduce deaths from cancer, it has not been shown to lower all-cause mortality, Dr. Marshall explained. A recent meta-analysis, for example, found that, aside from sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, no other cancer screening modalities meaningfully changed life expectancy.

“That’s why we’re struggling,” Dr. Marshall said. “We’re emotionally invested in having screening available to younger people because we’re seeing colon cancer in younger people. So, we want it to move earlier, but it’s expensive and it’s invasive.”

Docs debate differing guidance

The new ACP guidance, based on a critical review of existing guidelines, evidence, and modeling studies, argues that the potential harms of screening average-risk individuals under age 50 may outweigh the potential benefits.

The benefits of screening, of course, include identifying and removing precancerous lesions or localized cancer, while the potential harms include false positives that may lead to unnecessary additional tests, treatments, and costs. More invasive screening procedures, such as colonoscopy, can also come with their own risks, including serious bleeding and perforation.

For colonoscopy, for instance, the ACP team determined that starting screening at age 45 vs. 50 could prevent three additional CRC cases per 1,000 individuals screened (58 vs. 61) and one CRC death (27 vs. 28) over the recommended screening time frame. On the flip side, screening starting at age 45 could increase the incidence of gastrointestinal or cardiovascular events (14 vs. 16).

“Even if we assumed the modeling study had no limitations and accepted the results at face value, we would conclude that the small estimated benefits and harms roughly balance each other out, resulting in an inadequate net benefit to warrant CRC screening in average-risk adults aged 45 to 49 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, and ACP coauthors write.

Family physician Kenny Lin, MD, MPH, believes the updated ACP guidelines are reasonable, and points out the ACP is not the first group to disagree with the USPSTF’s recommendations.

“I think the [ACP] guidelines make a lot of sense,” said Dr. Lin, who practices in Lancaster, Pa. The American Academy of Family Physicians “also did not endorse the recommendations to start screenings at 45.” In its 2021 updated guidance, the AAFP recommended screening for CRC starting at age 50, concluding there was “insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening” in the 45 to 49 population.

However, Jason R. Woloski, MD, a family physician based in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., expressed concern that the differing guidelines will confuse patients as well as present challenges for primary care physicians.

“I feel like we took the last couple of years convincing people that earlier is better,” said Dr. Woloski, an associate professor of family medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Scranton, Pa. “It can send a mixed message to a patient after we’ve been stressing the importance of earlier [screening], and then saying, ‘Maybe we got it wrong; maybe we were okay the first time.’ ”

Mark A. Lewis, MD, a GI oncologist, had a similar initial reaction upon hearing about the updated guidelines: “The lack of synchronization across groups is going to create confusion among patients.”

Although he could not say definitively whether the recommendations will affect GI oncologists, because he only sees patients with advanced CRC, he does see the demands in primary care and gastroenterology shifting.

“I think the much bigger impact will be on primary care physicians and gastroenterologists,” said Dr. Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Healthcare in Murray, Utah. “My best guess is that the procedural burden on the latter will be mitigated by more stool testing ordered by primary care physicians. Patients may understandably prefer the convenience and lack of invasiveness of home-based fecal testing, but a positive FIT [fecal immunochemical test] without a follow-up scope is an incomplete screening.”

Dr. Marshall, however, had a different take. He does not envision the updated guidelines having much of a practical impact on physician practice. Most of the country is already not receiving proper colon cancer screenings, he said. Research shows more than 40% of Americans skip standard CRC screenings. Even anecdotally, he noted, friends in their 60s come to him and admit they haven’t had a colonoscopy yet.

Potential impact on patient outcomes, costs

Beyond mixed messaging, some experts worry that pushing CRC screening later could mean cancers are caught later, when they’re more advanced.

Finding cancers earlier, when they are easier and less expensive to treat, make earlier CRC screenings worthwhile, Dr. Woloski explained.

Dr. Lewis sees earlier screening as a way to stop a tumor from progressing before it can really pick up steam.

“To me the biggest advantage of colonoscopy is the interruption of the adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence, whereby a polyp that is completely removed cannot become an invasive adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Lewis said. “We’ve also had evidence for well over a decade that flexible sigmoidoscopy, which doesn’t come close to visualizing the entire colon, can confer a survival benefit.”

Another concern is the potential effect on insurance coverage.

Medicare and other insurers use USPSTF guidelines to make coverage decisions. However, because of this mixed message, Dr. Woloski questioned whether there would be more challenges regarding insurance coverage. “Does it mean primary care doctors are going to have to preauthorize a lot of these screenings even if you have shared decision-making with the patient?” he asked.

When it comes to screening referrals, Douglas A. Corley, MD, PhD, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente in northern California, said it’s critical for primary care physicians to educate patients about the differing views on screening benefits and harms as well as the different screening options.

“Given the different opinions, it is important to let people in this age group know that screening is an option recommended by some groups,” Dr. Corley said. “Colorectal cancer screening is very effective for decreasing the risk for death from colorectal cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Making sure all eligible people know this is an option provides the best way for patients to have an informed choice.”

Dr. Lin has already begun talking with patients about the differing recommendations. He said it’s helpful to simplify the issue and focus the conversation on what patients value most. For more assertive patients whose priority is finding every possible cancer early, starting screenings at age 45 may be reasonable, he said, whereas other patients may not find the process or possible side effects worth it.

“And then you have the middle group that decides, ‘Yes, I want to start at 45, but I want the fecal test. I don’t want to just jump into colonoscopy.’ ” Dr. Lin said. “That would be kind of a compromise where you’d be starting screening earlier, but not subjecting yourself to something that has more potential for harms.”

Dr. Woloski said he plans to continue making referrals based on the USPSTF recommendations.

“With every screening, it is about informed decision-making with the patient, but I think for now, since USPSTF still supports the earlier screening, I will probably stick with offering it earlier,” he said.

But when deciding on the appropriate timing for evaluating CRC, the most important distinction is between screening and diagnosis, Dr. Lewis added.

“The former is only appropriate in patients who are truly asymptomatic and who are truly average-risk,” he said. “The latter is critical in any patient with symptoms. I cannot count the number of times I have seen blood in the stool discounted as hemorrhoids without even an exam, digital rectal, or scope, to demonstrate that hemorrhoids are present and the culprit for blood loss.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recently updated colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidance from the American College of Physicians is raising concerns among some specialists.

The ACP’s clinical guidance, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, called for CRC screenings to start at age 50 in average-risk individuals who are asymptomatic. This recommendation, however, conflicts with guidelines from the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which, in 2021, officially lowered the recommended initial age of screening to 45.

Following the ACP’s announcement, several professional organizations, such as the American College of Radiology, criticized the new guidelines, calling them “a step backward” and warning they may hinder recent gains against CRC.

Some physicians believe the discordance will confuse patients and lead to varying referral practices among primary care physicians. And while insurers will likely continue to pay for screening procedures based on the USPSTF guidelines, which dictate insurance coverage, some physicians worry that insurers could create additional roadblocks for CRC screening coverage, such as requiring prior authorization.

“We’re in a conflicted space on this issue as a country,” said John L. Marshall, MD, a GI oncologist and director of The Ruesch Center for the Cure of GI Cancers at Georgetown University, Washington.

Ultimately, the physician community wants an inexpensive screening test that’s effective at preventing cancer and deaths, but the evidence thus far doesn’t necessarily support colonoscopy as that test, said Dr. Marshall, also chief medical officer for Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Although colonoscopy can prevent CRC by removing precancerous polyps and can reduce deaths from cancer, it has not been shown to lower all-cause mortality, Dr. Marshall explained. A recent meta-analysis, for example, found that, aside from sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, no other cancer screening modalities meaningfully changed life expectancy.

“That’s why we’re struggling,” Dr. Marshall said. “We’re emotionally invested in having screening available to younger people because we’re seeing colon cancer in younger people. So, we want it to move earlier, but it’s expensive and it’s invasive.”

Docs debate differing guidance

The new ACP guidance, based on a critical review of existing guidelines, evidence, and modeling studies, argues that the potential harms of screening average-risk individuals under age 50 may outweigh the potential benefits.

The benefits of screening, of course, include identifying and removing precancerous lesions or localized cancer, while the potential harms include false positives that may lead to unnecessary additional tests, treatments, and costs. More invasive screening procedures, such as colonoscopy, can also come with their own risks, including serious bleeding and perforation.

For colonoscopy, for instance, the ACP team determined that starting screening at age 45 vs. 50 could prevent three additional CRC cases per 1,000 individuals screened (58 vs. 61) and one CRC death (27 vs. 28) over the recommended screening time frame. On the flip side, screening starting at age 45 could increase the incidence of gastrointestinal or cardiovascular events (14 vs. 16).

“Even if we assumed the modeling study had no limitations and accepted the results at face value, we would conclude that the small estimated benefits and harms roughly balance each other out, resulting in an inadequate net benefit to warrant CRC screening in average-risk adults aged 45 to 49 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, and ACP coauthors write.

Family physician Kenny Lin, MD, MPH, believes the updated ACP guidelines are reasonable, and points out the ACP is not the first group to disagree with the USPSTF’s recommendations.

“I think the [ACP] guidelines make a lot of sense,” said Dr. Lin, who practices in Lancaster, Pa. The American Academy of Family Physicians “also did not endorse the recommendations to start screenings at 45.” In its 2021 updated guidance, the AAFP recommended screening for CRC starting at age 50, concluding there was “insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening” in the 45 to 49 population.

However, Jason R. Woloski, MD, a family physician based in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., expressed concern that the differing guidelines will confuse patients as well as present challenges for primary care physicians.

“I feel like we took the last couple of years convincing people that earlier is better,” said Dr. Woloski, an associate professor of family medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Scranton, Pa. “It can send a mixed message to a patient after we’ve been stressing the importance of earlier [screening], and then saying, ‘Maybe we got it wrong; maybe we were okay the first time.’ ”

Mark A. Lewis, MD, a GI oncologist, had a similar initial reaction upon hearing about the updated guidelines: “The lack of synchronization across groups is going to create confusion among patients.”

Although he could not say definitively whether the recommendations will affect GI oncologists, because he only sees patients with advanced CRC, he does see the demands in primary care and gastroenterology shifting.

“I think the much bigger impact will be on primary care physicians and gastroenterologists,” said Dr. Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Healthcare in Murray, Utah. “My best guess is that the procedural burden on the latter will be mitigated by more stool testing ordered by primary care physicians. Patients may understandably prefer the convenience and lack of invasiveness of home-based fecal testing, but a positive FIT [fecal immunochemical test] without a follow-up scope is an incomplete screening.”

Dr. Marshall, however, had a different take. He does not envision the updated guidelines having much of a practical impact on physician practice. Most of the country is already not receiving proper colon cancer screenings, he said. Research shows more than 40% of Americans skip standard CRC screenings. Even anecdotally, he noted, friends in their 60s come to him and admit they haven’t had a colonoscopy yet.

Potential impact on patient outcomes, costs

Beyond mixed messaging, some experts worry that pushing CRC screening later could mean cancers are caught later, when they’re more advanced.

Finding cancers earlier, when they are easier and less expensive to treat, make earlier CRC screenings worthwhile, Dr. Woloski explained.

Dr. Lewis sees earlier screening as a way to stop a tumor from progressing before it can really pick up steam.

“To me the biggest advantage of colonoscopy is the interruption of the adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence, whereby a polyp that is completely removed cannot become an invasive adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Lewis said. “We’ve also had evidence for well over a decade that flexible sigmoidoscopy, which doesn’t come close to visualizing the entire colon, can confer a survival benefit.”

Another concern is the potential effect on insurance coverage.

Medicare and other insurers use USPSTF guidelines to make coverage decisions. However, because of this mixed message, Dr. Woloski questioned whether there would be more challenges regarding insurance coverage. “Does it mean primary care doctors are going to have to preauthorize a lot of these screenings even if you have shared decision-making with the patient?” he asked.

When it comes to screening referrals, Douglas A. Corley, MD, PhD, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente in northern California, said it’s critical for primary care physicians to educate patients about the differing views on screening benefits and harms as well as the different screening options.

“Given the different opinions, it is important to let people in this age group know that screening is an option recommended by some groups,” Dr. Corley said. “Colorectal cancer screening is very effective for decreasing the risk for death from colorectal cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Making sure all eligible people know this is an option provides the best way for patients to have an informed choice.”

Dr. Lin has already begun talking with patients about the differing recommendations. He said it’s helpful to simplify the issue and focus the conversation on what patients value most. For more assertive patients whose priority is finding every possible cancer early, starting screenings at age 45 may be reasonable, he said, whereas other patients may not find the process or possible side effects worth it.

“And then you have the middle group that decides, ‘Yes, I want to start at 45, but I want the fecal test. I don’t want to just jump into colonoscopy.’ ” Dr. Lin said. “That would be kind of a compromise where you’d be starting screening earlier, but not subjecting yourself to something that has more potential for harms.”

Dr. Woloski said he plans to continue making referrals based on the USPSTF recommendations.

“With every screening, it is about informed decision-making with the patient, but I think for now, since USPSTF still supports the earlier screening, I will probably stick with offering it earlier,” he said.

But when deciding on the appropriate timing for evaluating CRC, the most important distinction is between screening and diagnosis, Dr. Lewis added.

“The former is only appropriate in patients who are truly asymptomatic and who are truly average-risk,” he said. “The latter is critical in any patient with symptoms. I cannot count the number of times I have seen blood in the stool discounted as hemorrhoids without even an exam, digital rectal, or scope, to demonstrate that hemorrhoids are present and the culprit for blood loss.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jury out on how tea drinking influences colorectal cancer risk

TOPLINE:

A meta-analysis finds that tea drinking may reduce the risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) by 24%, but the estimate is “uncertain,” and the actual effect on CRC risk can range from a reduction of 51% to an increase of 18%, researchers say.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies (11 cohort, three case-control, and one randomized controlled trial) with nearly 2.7 million participants.

- The studies were conducted in Asia, North America, Europe, and Oceania between 1986 and 2015 and included black and green tea.

- Tea consumption was dichotomized as < 1 cup vs. ≥ 1 cups daily. A random effects model was used for data analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- No statistically significant association was found between tea consumption and CRC risk (relative risk, 0.76).

- By geographic region, results of an American subgroup analysis suggested tea drinking might be protective against CRC (RR, 0.33), while data from the United Kingdom (RR, 1.45) and Italian (RR, 1.15) subgroups had opposite results.

- In subgroups by tea type, green tea was associated with a lower CRC risk (RR, 0.05).

- Sensitivity analysis revealed that the effect on CRC risk can range from a reduction of 51% (RR, 0.49) to an increase of 18% (RR, 1.18).

IN PRACTICE:

“Taken together, this meta-analysis suggests that tea consumption may not be linked to the development of CRC. These relationships still need to be confirmed by additional well-designed large prospective studies and randomized clinical trials,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with co–first authors Yu Huang and Qiang Chen, with the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China, was published online in BMC Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

There was a high level of heterogeneity in the original studies, as well as variations in the quantity and types of tea consumed and in the design and quality of the studies. Some studies did not account for potentially important variables, such as alcohol use and diet.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Hebei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and the Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A meta-analysis finds that tea drinking may reduce the risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) by 24%, but the estimate is “uncertain,” and the actual effect on CRC risk can range from a reduction of 51% to an increase of 18%, researchers say.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies (11 cohort, three case-control, and one randomized controlled trial) with nearly 2.7 million participants.

- The studies were conducted in Asia, North America, Europe, and Oceania between 1986 and 2015 and included black and green tea.

- Tea consumption was dichotomized as < 1 cup vs. ≥ 1 cups daily. A random effects model was used for data analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- No statistically significant association was found between tea consumption and CRC risk (relative risk, 0.76).

- By geographic region, results of an American subgroup analysis suggested tea drinking might be protective against CRC (RR, 0.33), while data from the United Kingdom (RR, 1.45) and Italian (RR, 1.15) subgroups had opposite results.

- In subgroups by tea type, green tea was associated with a lower CRC risk (RR, 0.05).

- Sensitivity analysis revealed that the effect on CRC risk can range from a reduction of 51% (RR, 0.49) to an increase of 18% (RR, 1.18).

IN PRACTICE:

“Taken together, this meta-analysis suggests that tea consumption may not be linked to the development of CRC. These relationships still need to be confirmed by additional well-designed large prospective studies and randomized clinical trials,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with co–first authors Yu Huang and Qiang Chen, with the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China, was published online in BMC Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

There was a high level of heterogeneity in the original studies, as well as variations in the quantity and types of tea consumed and in the design and quality of the studies. Some studies did not account for potentially important variables, such as alcohol use and diet.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Hebei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and the Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A meta-analysis finds that tea drinking may reduce the risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) by 24%, but the estimate is “uncertain,” and the actual effect on CRC risk can range from a reduction of 51% to an increase of 18%, researchers say.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies (11 cohort, three case-control, and one randomized controlled trial) with nearly 2.7 million participants.

- The studies were conducted in Asia, North America, Europe, and Oceania between 1986 and 2015 and included black and green tea.

- Tea consumption was dichotomized as < 1 cup vs. ≥ 1 cups daily. A random effects model was used for data analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- No statistically significant association was found between tea consumption and CRC risk (relative risk, 0.76).

- By geographic region, results of an American subgroup analysis suggested tea drinking might be protective against CRC (RR, 0.33), while data from the United Kingdom (RR, 1.45) and Italian (RR, 1.15) subgroups had opposite results.

- In subgroups by tea type, green tea was associated with a lower CRC risk (RR, 0.05).

- Sensitivity analysis revealed that the effect on CRC risk can range from a reduction of 51% (RR, 0.49) to an increase of 18% (RR, 1.18).

IN PRACTICE:

“Taken together, this meta-analysis suggests that tea consumption may not be linked to the development of CRC. These relationships still need to be confirmed by additional well-designed large prospective studies and randomized clinical trials,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with co–first authors Yu Huang and Qiang Chen, with the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China, was published online in BMC Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

There was a high level of heterogeneity in the original studies, as well as variations in the quantity and types of tea consumed and in the design and quality of the studies. Some studies did not account for potentially important variables, such as alcohol use and diet.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Hebei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and the Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vegetarian diets tied to lower risk for some GI cancers

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers did a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven original studies (six cohorts and one case-control) involving 686,691 people.

- Pooled relative risk for gastric, colorectal, and upper gastrointestinal cancers were assessed with confidence intervals in multivariate analysis accounting for potential confounders.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with nonvegetarian diets, vegetarian diets were inversely associated with the risk for GI tumor development (relative risk, 0.77).

- In a subgroup analysis, vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for gastric cancer (RR, 0.41) and colorectal cancer (RR, 0.85) but not with upper GI cancer (excluding stomach; RR, 0.93).

- Vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for GI cancer in men (RR, 0.57) but not women (RR, 0.89).

- Vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for GI cancer in North American (RR, 0.76) and Asian populations (RR, 0.43) but not in European populations (RR, 0.83).

IN PRACTICE:

“The results of this systematic review indicate that adherence to vegetarian diets can reduce the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, compared with non-vegetarian diets. This study provides a reference for primary prevention strategies for gastrointestinal cancers,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Tongtong Bai, of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, was published online on in the European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The effects of vegetarian diets on GI tumorigenesis may be influenced by gender and geographical region. The heterogeneity of effects of vegetarian diets on different GI cancers could be due to the small number of studies included and could represent chance variation. The results need to be confirmed by studies of populations in other regions. There was evidence of publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers did a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven original studies (six cohorts and one case-control) involving 686,691 people.

- Pooled relative risk for gastric, colorectal, and upper gastrointestinal cancers were assessed with confidence intervals in multivariate analysis accounting for potential confounders.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with nonvegetarian diets, vegetarian diets were inversely associated with the risk for GI tumor development (relative risk, 0.77).

- In a subgroup analysis, vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for gastric cancer (RR, 0.41) and colorectal cancer (RR, 0.85) but not with upper GI cancer (excluding stomach; RR, 0.93).

- Vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for GI cancer in men (RR, 0.57) but not women (RR, 0.89).

- Vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for GI cancer in North American (RR, 0.76) and Asian populations (RR, 0.43) but not in European populations (RR, 0.83).

IN PRACTICE:

“The results of this systematic review indicate that adherence to vegetarian diets can reduce the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, compared with non-vegetarian diets. This study provides a reference for primary prevention strategies for gastrointestinal cancers,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Tongtong Bai, of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, was published online on in the European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The effects of vegetarian diets on GI tumorigenesis may be influenced by gender and geographical region. The heterogeneity of effects of vegetarian diets on different GI cancers could be due to the small number of studies included and could represent chance variation. The results need to be confirmed by studies of populations in other regions. There was evidence of publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers did a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven original studies (six cohorts and one case-control) involving 686,691 people.

- Pooled relative risk for gastric, colorectal, and upper gastrointestinal cancers were assessed with confidence intervals in multivariate analysis accounting for potential confounders.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with nonvegetarian diets, vegetarian diets were inversely associated with the risk for GI tumor development (relative risk, 0.77).

- In a subgroup analysis, vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for gastric cancer (RR, 0.41) and colorectal cancer (RR, 0.85) but not with upper GI cancer (excluding stomach; RR, 0.93).

- Vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for GI cancer in men (RR, 0.57) but not women (RR, 0.89).

- Vegetarian diets were negatively correlated with the risk for GI cancer in North American (RR, 0.76) and Asian populations (RR, 0.43) but not in European populations (RR, 0.83).

IN PRACTICE:

“The results of this systematic review indicate that adherence to vegetarian diets can reduce the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, compared with non-vegetarian diets. This study provides a reference for primary prevention strategies for gastrointestinal cancers,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Tongtong Bai, of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, was published online on in the European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The effects of vegetarian diets on GI tumorigenesis may be influenced by gender and geographical region. The heterogeneity of effects of vegetarian diets on different GI cancers could be due to the small number of studies included and could represent chance variation. The results need to be confirmed by studies of populations in other regions. There was evidence of publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Testing for Associations Between an Environmental Risk Score and Most Significant Colonoscopy Findings Among US Veterans in CSP #380

PURPOSE

To construct a composite score representing modifiable lifestyle and environmental risk (e-score) and test for associations with colonoscopy findings among US Veteran participants of CSP #380.

BACKGROUND

Understanding environmental and genetic risks beyond self-reported family history is a way to develop personalized colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO) study examined CRC risk stratified by sex and included an e-score along with genetic risk scores, where higher scores indicated higher risk. Both e-scores and genetic risk scores were significantly associated with CRC risk and models that included these were more robust than models that only included family history.

METHODS

CSP #380 is a prospective study of outcomes during colonoscopy screening (1994-97) and follow- up (1994-2009) for 3,121 asymptomatic Veterans aged 50-75. The dichotomous outcome of interest was most significant colonoscopy findings (MSCF) of i) advanced neoplasia (AN: ≥10mm adenomas or advanced histology, or invasive CRC) vs. ii) non-advanced adenomas (<10mm with tubular histology) or no neoplasia. The independent variable, e-score, was weighted according to the GECCO male sample and comprised BMI, height, diabetes, NSAID use, education, alcohol intake, smoking, exercise, and diet.

DATA ANALYSIS

Logistic regression was used to test associations between MSCF and e-scores, controlling for age, family history and number of colonoscopies.

RESULTS

Among 2,846 participants with complete data, 33.3% were aged 50-59 at baseline, 97% were male, and 83.8% were White. Those with AN (n=405, 14.2%) compared to those without AN (n=2,441, 85.8%) had higher median e-scores (29.5, range:0-99.8 vs. 29.0, range:5.2-100), suggesting a difference. The logistic regression models showed older participants (aOR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.03-1.06) and those with more colonoscopies (aOR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.06-1.33) had higher odds for AN. However, e-scores and family history were not significantly associated with MCSF.

IMPLICATIONS

E-scores were not significantly associated with MSCF in this preliminary study. Developing escores among a larger, diverse sample (N~381,695) of US veterans in the Million Veterans Program study will allow for stratified models in investigations of environmental and genetic risk for CRC. Outcomes from those analyses will support advances in screening guidelines with tailored programs for long-term CRC prevention.

PURPOSE

To construct a composite score representing modifiable lifestyle and environmental risk (e-score) and test for associations with colonoscopy findings among US Veteran participants of CSP #380.

BACKGROUND

Understanding environmental and genetic risks beyond self-reported family history is a way to develop personalized colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO) study examined CRC risk stratified by sex and included an e-score along with genetic risk scores, where higher scores indicated higher risk. Both e-scores and genetic risk scores were significantly associated with CRC risk and models that included these were more robust than models that only included family history.

METHODS

CSP #380 is a prospective study of outcomes during colonoscopy screening (1994-97) and follow- up (1994-2009) for 3,121 asymptomatic Veterans aged 50-75. The dichotomous outcome of interest was most significant colonoscopy findings (MSCF) of i) advanced neoplasia (AN: ≥10mm adenomas or advanced histology, or invasive CRC) vs. ii) non-advanced adenomas (<10mm with tubular histology) or no neoplasia. The independent variable, e-score, was weighted according to the GECCO male sample and comprised BMI, height, diabetes, NSAID use, education, alcohol intake, smoking, exercise, and diet.

DATA ANALYSIS

Logistic regression was used to test associations between MSCF and e-scores, controlling for age, family history and number of colonoscopies.

RESULTS

Among 2,846 participants with complete data, 33.3% were aged 50-59 at baseline, 97% were male, and 83.8% were White. Those with AN (n=405, 14.2%) compared to those without AN (n=2,441, 85.8%) had higher median e-scores (29.5, range:0-99.8 vs. 29.0, range:5.2-100), suggesting a difference. The logistic regression models showed older participants (aOR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.03-1.06) and those with more colonoscopies (aOR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.06-1.33) had higher odds for AN. However, e-scores and family history were not significantly associated with MCSF.

IMPLICATIONS

E-scores were not significantly associated with MSCF in this preliminary study. Developing escores among a larger, diverse sample (N~381,695) of US veterans in the Million Veterans Program study will allow for stratified models in investigations of environmental and genetic risk for CRC. Outcomes from those analyses will support advances in screening guidelines with tailored programs for long-term CRC prevention.

PURPOSE

To construct a composite score representing modifiable lifestyle and environmental risk (e-score) and test for associations with colonoscopy findings among US Veteran participants of CSP #380.

BACKGROUND

Understanding environmental and genetic risks beyond self-reported family history is a way to develop personalized colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO) study examined CRC risk stratified by sex and included an e-score along with genetic risk scores, where higher scores indicated higher risk. Both e-scores and genetic risk scores were significantly associated with CRC risk and models that included these were more robust than models that only included family history.

METHODS

CSP #380 is a prospective study of outcomes during colonoscopy screening (1994-97) and follow- up (1994-2009) for 3,121 asymptomatic Veterans aged 50-75. The dichotomous outcome of interest was most significant colonoscopy findings (MSCF) of i) advanced neoplasia (AN: ≥10mm adenomas or advanced histology, or invasive CRC) vs. ii) non-advanced adenomas (<10mm with tubular histology) or no neoplasia. The independent variable, e-score, was weighted according to the GECCO male sample and comprised BMI, height, diabetes, NSAID use, education, alcohol intake, smoking, exercise, and diet.

DATA ANALYSIS

Logistic regression was used to test associations between MSCF and e-scores, controlling for age, family history and number of colonoscopies.

RESULTS

Among 2,846 participants with complete data, 33.3% were aged 50-59 at baseline, 97% were male, and 83.8% were White. Those with AN (n=405, 14.2%) compared to those without AN (n=2,441, 85.8%) had higher median e-scores (29.5, range:0-99.8 vs. 29.0, range:5.2-100), suggesting a difference. The logistic regression models showed older participants (aOR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.03-1.06) and those with more colonoscopies (aOR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.06-1.33) had higher odds for AN. However, e-scores and family history were not significantly associated with MCSF.

IMPLICATIONS

E-scores were not significantly associated with MSCF in this preliminary study. Developing escores among a larger, diverse sample (N~381,695) of US veterans in the Million Veterans Program study will allow for stratified models in investigations of environmental and genetic risk for CRC. Outcomes from those analyses will support advances in screening guidelines with tailored programs for long-term CRC prevention.

Associations Between Colorectal Cancer Progression and Dietary Patterns of US Veterans in CSP #380

PURPOSE

To analyze associations between colorectal cancer progression and diet scores calculated using published scoring approaches for three dietary patterns: Healthy Eating Index (HEI), Mediterranean Diet (Mediterranean), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet (DASH).

BACKGROUND

Little is known about whether longterm risk for progression to colorectal cancer is associated with recommended healthy dietary patterns among US veterans. Previous studies of veterans have shown higher intake of fiber and vitamin D reduced risk, and red meat increased risk for finding colorectal cancer precursors during colonoscopy. However, studying dietary patterns in aggregate may be more clinically relevant for longitudinal studies of colorectal cancer prevention.

METHODS

3,121 asymptomatic US veterans aged 50-75 received colonoscopy between 1994-97 and were followed through 2009. Most significant colonoscopy findings (MSCF) across the study period were: (i) no neoplasia (NN), (ii) non-advanced adenomas (NAAs) or (iii) advanced neoplasia (AN). Baseline dietary questionnaire data were used to calculate three dietary pattern (HEI, Mediterranean, and DASH) scores.

DATA ANALYSIS

Multinomial logistic regression models were used in a cross-sectional analysis to test for associations represented by adjusted odds ratios (aOR) between MSCF and dietary pattern scores, controlling for demographics and clinical risk factors.

RESULTS

Among 3,023 participants with complete data, 97% were male, and 83.8% were White. Increasing scores, representing healthier diets, for each dietary pattern had similar or lower odds for NAAs and AN, respectively, versus NN. They were HEI: aOR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.99-1.01 and aOR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.99-1.01; Mediterranean: aOR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95-1.02 and aOR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90-0.999; DASH: aOR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.99- 1.00 and aOR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98-0.999. Across each dietary pattern, higher whole grain and fiber category scores generally had lower odds for NAAs and AN.

CONCLUSIONS

Study results revealed that overall higher dietary quality and specific dietary components of whole grain or fiber intake, based on three different dietary patterns suggest lower odds for CRC precursors. Findings indicate potential differences in dietary intake patterns and more research is needed to determine the benefit of developing tailored CRC screening and surveillance clinical guidelines.

PURPOSE

To analyze associations between colorectal cancer progression and diet scores calculated using published scoring approaches for three dietary patterns: Healthy Eating Index (HEI), Mediterranean Diet (Mediterranean), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet (DASH).

BACKGROUND

Little is known about whether longterm risk for progression to colorectal cancer is associated with recommended healthy dietary patterns among US veterans. Previous studies of veterans have shown higher intake of fiber and vitamin D reduced risk, and red meat increased risk for finding colorectal cancer precursors during colonoscopy. However, studying dietary patterns in aggregate may be more clinically relevant for longitudinal studies of colorectal cancer prevention.

METHODS

3,121 asymptomatic US veterans aged 50-75 received colonoscopy between 1994-97 and were followed through 2009. Most significant colonoscopy findings (MSCF) across the study period were: (i) no neoplasia (NN), (ii) non-advanced adenomas (NAAs) or (iii) advanced neoplasia (AN). Baseline dietary questionnaire data were used to calculate three dietary pattern (HEI, Mediterranean, and DASH) scores.

DATA ANALYSIS

Multinomial logistic regression models were used in a cross-sectional analysis to test for associations represented by adjusted odds ratios (aOR) between MSCF and dietary pattern scores, controlling for demographics and clinical risk factors.

RESULTS

Among 3,023 participants with complete data, 97% were male, and 83.8% were White. Increasing scores, representing healthier diets, for each dietary pattern had similar or lower odds for NAAs and AN, respectively, versus NN. They were HEI: aOR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.99-1.01 and aOR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.99-1.01; Mediterranean: aOR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95-1.02 and aOR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90-0.999; DASH: aOR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.99- 1.00 and aOR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98-0.999. Across each dietary pattern, higher whole grain and fiber category scores generally had lower odds for NAAs and AN.

CONCLUSIONS

Study results revealed that overall higher dietary quality and specific dietary components of whole grain or fiber intake, based on three different dietary patterns suggest lower odds for CRC precursors. Findings indicate potential differences in dietary intake patterns and more research is needed to determine the benefit of developing tailored CRC screening and surveillance clinical guidelines.

PURPOSE

To analyze associations between colorectal cancer progression and diet scores calculated using published scoring approaches for three dietary patterns: Healthy Eating Index (HEI), Mediterranean Diet (Mediterranean), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet (DASH).

BACKGROUND

Little is known about whether longterm risk for progression to colorectal cancer is associated with recommended healthy dietary patterns among US veterans. Previous studies of veterans have shown higher intake of fiber and vitamin D reduced risk, and red meat increased risk for finding colorectal cancer precursors during colonoscopy. However, studying dietary patterns in aggregate may be more clinically relevant for longitudinal studies of colorectal cancer prevention.

METHODS

3,121 asymptomatic US veterans aged 50-75 received colonoscopy between 1994-97 and were followed through 2009. Most significant colonoscopy findings (MSCF) across the study period were: (i) no neoplasia (NN), (ii) non-advanced adenomas (NAAs) or (iii) advanced neoplasia (AN). Baseline dietary questionnaire data were used to calculate three dietary pattern (HEI, Mediterranean, and DASH) scores.

DATA ANALYSIS

Multinomial logistic regression models were used in a cross-sectional analysis to test for associations represented by adjusted odds ratios (aOR) between MSCF and dietary pattern scores, controlling for demographics and clinical risk factors.

RESULTS

Among 3,023 participants with complete data, 97% were male, and 83.8% were White. Increasing scores, representing healthier diets, for each dietary pattern had similar or lower odds for NAAs and AN, respectively, versus NN. They were HEI: aOR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.99-1.01 and aOR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.99-1.01; Mediterranean: aOR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95-1.02 and aOR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90-0.999; DASH: aOR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.99- 1.00 and aOR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98-0.999. Across each dietary pattern, higher whole grain and fiber category scores generally had lower odds for NAAs and AN.

CONCLUSIONS

Study results revealed that overall higher dietary quality and specific dietary components of whole grain or fiber intake, based on three different dietary patterns suggest lower odds for CRC precursors. Findings indicate potential differences in dietary intake patterns and more research is needed to determine the benefit of developing tailored CRC screening and surveillance clinical guidelines.

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma of the Rectum: Clinical Outcomes and Characteristics of 14,044 Patients From the National Cancer Database

PURPOSE

Study clinical characteristics of Rectal Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (RMA).

BACKGROUND

RMA is a rare histological subtype with an impaired response to chemoradiotherapy and an overall poor prognosis. High-grade tumors are associated with older age. Previous studies have shown conflicting results on prognosis.

METHODS

Retrospective analysis of National Cancer Database was conducted from 2004-2020 for subjects with histology code 8480 in primary sites C19 and C20 (rectosigmoid-junction and rectum, n = 14,044), using multivariate analysis with Cox regression.

RESULTS

Median age of diagnosis was 65 years with 69.5% were in the 45-75 years age range. 59.2% were male while 40.8% were female. 84.7% were White, 9.7% were Black, 0.4% were American Indian and 3.4% were Asian. 6.9% were Hispanic. 33.9% were in the upper-income quartile. 40.6% were seen at community cancer programs while 33% went to academic programs. 36.5% had stage III RMA. Out of the 14,044 patients with RMA, 10,546 received surgery, 5,179 received chemotherapy, 233 received immunotherapy and 55 received hormone therapy. Patients >75 years had significantly lower overall survival (OS) compared to those <45 years (HR 0.67). Female patients had significantly higher OS than male (HR - 0.07). Black patients had significantly lower OS than White (HR 0.08). Hispanic patients had significantly higher OS than non- Hispanic (HR - 0.14). Patients with private and government insurance had significantly higher OS than noninsured patients (HR - 0.35 and - 0.26 respectively). Patients with median higher-income quartiles had significantly higher OS than lower quartiles (HR - 0.13). Academic facilities had significantly higher OS than community programs (HR - 0.13). Patients who received surgery had significantly higher OS than those that did not (HR - 0.67); median survival for patients who received surgery was 71 months vs 28 months for non-surgical candidates.

CONCLUSIONS

Surgery is the most important treatment modality in RMA. Uninsured, older Black male patients from lower-income quartiles had significantly lower OS. Access to academic centers also contributed to differences in OS outcomes which throws light on healthcare disparities.

IMPLICATIONS

Additional studies need to be conducted for viable solutions to assist with social determinants of healthcare in RMA.

PURPOSE

Study clinical characteristics of Rectal Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (RMA).

BACKGROUND

RMA is a rare histological subtype with an impaired response to chemoradiotherapy and an overall poor prognosis. High-grade tumors are associated with older age. Previous studies have shown conflicting results on prognosis.

METHODS

Retrospective analysis of National Cancer Database was conducted from 2004-2020 for subjects with histology code 8480 in primary sites C19 and C20 (rectosigmoid-junction and rectum, n = 14,044), using multivariate analysis with Cox regression.

RESULTS

Median age of diagnosis was 65 years with 69.5% were in the 45-75 years age range. 59.2% were male while 40.8% were female. 84.7% were White, 9.7% were Black, 0.4% were American Indian and 3.4% were Asian. 6.9% were Hispanic. 33.9% were in the upper-income quartile. 40.6% were seen at community cancer programs while 33% went to academic programs. 36.5% had stage III RMA. Out of the 14,044 patients with RMA, 10,546 received surgery, 5,179 received chemotherapy, 233 received immunotherapy and 55 received hormone therapy. Patients >75 years had significantly lower overall survival (OS) compared to those <45 years (HR 0.67). Female patients had significantly higher OS than male (HR - 0.07). Black patients had significantly lower OS than White (HR 0.08). Hispanic patients had significantly higher OS than non- Hispanic (HR - 0.14). Patients with private and government insurance had significantly higher OS than noninsured patients (HR - 0.35 and - 0.26 respectively). Patients with median higher-income quartiles had significantly higher OS than lower quartiles (HR - 0.13). Academic facilities had significantly higher OS than community programs (HR - 0.13). Patients who received surgery had significantly higher OS than those that did not (HR - 0.67); median survival for patients who received surgery was 71 months vs 28 months for non-surgical candidates.

CONCLUSIONS

Surgery is the most important treatment modality in RMA. Uninsured, older Black male patients from lower-income quartiles had significantly lower OS. Access to academic centers also contributed to differences in OS outcomes which throws light on healthcare disparities.

IMPLICATIONS

Additional studies need to be conducted for viable solutions to assist with social determinants of healthcare in RMA.

PURPOSE

Study clinical characteristics of Rectal Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (RMA).

BACKGROUND

RMA is a rare histological subtype with an impaired response to chemoradiotherapy and an overall poor prognosis. High-grade tumors are associated with older age. Previous studies have shown conflicting results on prognosis.

METHODS

Retrospective analysis of National Cancer Database was conducted from 2004-2020 for subjects with histology code 8480 in primary sites C19 and C20 (rectosigmoid-junction and rectum, n = 14,044), using multivariate analysis with Cox regression.

RESULTS

Median age of diagnosis was 65 years with 69.5% were in the 45-75 years age range. 59.2% were male while 40.8% were female. 84.7% were White, 9.7% were Black, 0.4% were American Indian and 3.4% were Asian. 6.9% were Hispanic. 33.9% were in the upper-income quartile. 40.6% were seen at community cancer programs while 33% went to academic programs. 36.5% had stage III RMA. Out of the 14,044 patients with RMA, 10,546 received surgery, 5,179 received chemotherapy, 233 received immunotherapy and 55 received hormone therapy. Patients >75 years had significantly lower overall survival (OS) compared to those <45 years (HR 0.67). Female patients had significantly higher OS than male (HR - 0.07). Black patients had significantly lower OS than White (HR 0.08). Hispanic patients had significantly higher OS than non- Hispanic (HR - 0.14). Patients with private and government insurance had significantly higher OS than noninsured patients (HR - 0.35 and - 0.26 respectively). Patients with median higher-income quartiles had significantly higher OS than lower quartiles (HR - 0.13). Academic facilities had significantly higher OS than community programs (HR - 0.13). Patients who received surgery had significantly higher OS than those that did not (HR - 0.67); median survival for patients who received surgery was 71 months vs 28 months for non-surgical candidates.

CONCLUSIONS

Surgery is the most important treatment modality in RMA. Uninsured, older Black male patients from lower-income quartiles had significantly lower OS. Access to academic centers also contributed to differences in OS outcomes which throws light on healthcare disparities.

IMPLICATIONS

Additional studies need to be conducted for viable solutions to assist with social determinants of healthcare in RMA.

High-intensity interval training before major surgery may boost postoperative outcomes

TOPLINE:

It cuts the risk of postoperative complications and may shorten hospital length of stay and improve postoperative quality of life.

METHODOLOGY:

Evidence suggests CRF – which improves physical and cognitive function and is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular risk – can be enhanced before major surgeries, but reported postoperative outcomes in previous reviews have been inconsistent.

In the study, HIIT involved repeated aerobic high-intensity exercise intervals at about 80% of maximum heart rate, followed by active recovery.

The meta-analysis included 12 studies with 832 patients (mean age, 67) that compared preoperative HIIT – supervised at hospitals, gyms, or community or physical therapy centers, or unsupervised at home – with standard care for patients slated for major surgery, including liver, lung, colorectal, urologic, and mixed major abdominal operations.

The primary outcome was change in CRF by peak VO2 or 6-minute walk test; other endpoints included change in endurance time and postoperative outcomes.

TAKEAWAY:

Preoperative HIIT (median total, 160 minutes; range, 80-240 minutes; intense exercise during 6-40 sessions) was associated with an increase in peak oxygen consumption (VO2 peak) by 2.59 mL/kg/min (95% confidence interval, 1.52-3.65 mL/kg/min; P < .001), compared with standard care, which represents about a 10% increase in CRF.

In eight studies that involved 770 patients, there was moderate evidence that preoperative HIIT cut the odds ratio for postoperative complications by more than half (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.32-0.60; P < .001); there was a similar apparent benefit in an analysis that was limited to patients who were slated for abdominal surgery (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.29-0.68; P < .001).

An analysis that was limited to studies that reported hospital length of stay showed a clinically relevant but nonsignificant 3-day reduction among patients in the HIIT groups.

Most quality of life assessments did not show post-HIIT improvements; some showed a significant benefit 6 weeks after surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

The results suggest preoperative HIIT may improve postoperative outcomes. By extension, it could be cost-effective and “should be included in prehabilitation programs,” the report states.

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Kari Clifford, PhD, Otago Medical School, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, and colleagues. It was published online June 30, 2023, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Included studies were heterogeneous in methodology; for example, HIIT definitions and protocols varied across almost every study. Data reporting was incomplete, the samples sizes in the studies were limited, and patients could not be blinded to their intervention. The patients could not be stratified on the basis of frailty. There were limited HIIT data from patients who underwent orthopedic surgeries.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding from the University of Otago. The authors reported no conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

It cuts the risk of postoperative complications and may shorten hospital length of stay and improve postoperative quality of life.

METHODOLOGY:

Evidence suggests CRF – which improves physical and cognitive function and is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular risk – can be enhanced before major surgeries, but reported postoperative outcomes in previous reviews have been inconsistent.

In the study, HIIT involved repeated aerobic high-intensity exercise intervals at about 80% of maximum heart rate, followed by active recovery.

The meta-analysis included 12 studies with 832 patients (mean age, 67) that compared preoperative HIIT – supervised at hospitals, gyms, or community or physical therapy centers, or unsupervised at home – with standard care for patients slated for major surgery, including liver, lung, colorectal, urologic, and mixed major abdominal operations.

The primary outcome was change in CRF by peak VO2 or 6-minute walk test; other endpoints included change in endurance time and postoperative outcomes.

TAKEAWAY:

Preoperative HIIT (median total, 160 minutes; range, 80-240 minutes; intense exercise during 6-40 sessions) was associated with an increase in peak oxygen consumption (VO2 peak) by 2.59 mL/kg/min (95% confidence interval, 1.52-3.65 mL/kg/min; P < .001), compared with standard care, which represents about a 10% increase in CRF.

In eight studies that involved 770 patients, there was moderate evidence that preoperative HIIT cut the odds ratio for postoperative complications by more than half (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.32-0.60; P < .001); there was a similar apparent benefit in an analysis that was limited to patients who were slated for abdominal surgery (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.29-0.68; P < .001).

An analysis that was limited to studies that reported hospital length of stay showed a clinically relevant but nonsignificant 3-day reduction among patients in the HIIT groups.

Most quality of life assessments did not show post-HIIT improvements; some showed a significant benefit 6 weeks after surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

The results suggest preoperative HIIT may improve postoperative outcomes. By extension, it could be cost-effective and “should be included in prehabilitation programs,” the report states.

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Kari Clifford, PhD, Otago Medical School, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, and colleagues. It was published online June 30, 2023, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Included studies were heterogeneous in methodology; for example, HIIT definitions and protocols varied across almost every study. Data reporting was incomplete, the samples sizes in the studies were limited, and patients could not be blinded to their intervention. The patients could not be stratified on the basis of frailty. There were limited HIIT data from patients who underwent orthopedic surgeries.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding from the University of Otago. The authors reported no conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

It cuts the risk of postoperative complications and may shorten hospital length of stay and improve postoperative quality of life.

METHODOLOGY:

Evidence suggests CRF – which improves physical and cognitive function and is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular risk – can be enhanced before major surgeries, but reported postoperative outcomes in previous reviews have been inconsistent.

In the study, HIIT involved repeated aerobic high-intensity exercise intervals at about 80% of maximum heart rate, followed by active recovery.

The meta-analysis included 12 studies with 832 patients (mean age, 67) that compared preoperative HIIT – supervised at hospitals, gyms, or community or physical therapy centers, or unsupervised at home – with standard care for patients slated for major surgery, including liver, lung, colorectal, urologic, and mixed major abdominal operations.

The primary outcome was change in CRF by peak VO2 or 6-minute walk test; other endpoints included change in endurance time and postoperative outcomes.

TAKEAWAY:

Preoperative HIIT (median total, 160 minutes; range, 80-240 minutes; intense exercise during 6-40 sessions) was associated with an increase in peak oxygen consumption (VO2 peak) by 2.59 mL/kg/min (95% confidence interval, 1.52-3.65 mL/kg/min; P < .001), compared with standard care, which represents about a 10% increase in CRF.

In eight studies that involved 770 patients, there was moderate evidence that preoperative HIIT cut the odds ratio for postoperative complications by more than half (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.32-0.60; P < .001); there was a similar apparent benefit in an analysis that was limited to patients who were slated for abdominal surgery (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.29-0.68; P < .001).

An analysis that was limited to studies that reported hospital length of stay showed a clinically relevant but nonsignificant 3-day reduction among patients in the HIIT groups.

Most quality of life assessments did not show post-HIIT improvements; some showed a significant benefit 6 weeks after surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

The results suggest preoperative HIIT may improve postoperative outcomes. By extension, it could be cost-effective and “should be included in prehabilitation programs,” the report states.

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Kari Clifford, PhD, Otago Medical School, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, and colleagues. It was published online June 30, 2023, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Included studies were heterogeneous in methodology; for example, HIIT definitions and protocols varied across almost every study. Data reporting was incomplete, the samples sizes in the studies were limited, and patients could not be blinded to their intervention. The patients could not be stratified on the basis of frailty. There were limited HIIT data from patients who underwent orthopedic surgeries.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding from the University of Otago. The authors reported no conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Does timing of surgery affect rectal cancer outcomes?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A total of 1,506 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by total mesorectal excision were divided into three groups based on the time interval between therapy and surgery: short (8 weeks), intermediate (> 8 to 12 weeks), and long (> 12 weeks).

- The primary outcome was pathologic complete response, and secondary outcomes included other histopathologic results, perioperative events, and survival outcomes.

- Median follow-up was 33 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, a pathologic complete response was observed in 255 patients (17.2%).

- Compared with the intermediate interval (reference) group, investigators found no association between time interval and pathologic complete response in the short-interval (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-1.01) or long-interval groups (OR, 1.07; P = .70).

- A long interval was significantly associated with a lower risk of a bad response as measured by tumor regression grade 2-3, compared with the reference category (OR, 0.47), but a higher risk of minor postoperative complications (OR, 1.43), conversion to open surgery (OR, 3.14), and longer operative time.

- The long-interval group was associated with a significantly reduced risk of systemic recurrence, compared with the reference group (hazard ratio, 0.59; P = .04), but not improved overall survival (HR, 1.38; P = .11) or locoregional recurrence (HR, 0.53; P = .18); no significant findings occurred for the short versus intermediate group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Findings suggest that delaying surgery may improve tumor regression and decrease risk of distant metastasis but increase surgical complexity,” the authors conclude. “Nonetheless, the reported improvements in tumor regression and systemic recurrence in the long-interval group were unexpectedly not followed by improved [overall survival].”

SOURCE:

F. Borja de Lacy, MD, PhD, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, University of Barcelona, led the study, published online in JAMA Surgery, with an accompanying editorial.

LIMITATIONS:

- The study’s main limitation was its retrospective design, which could have resulted in missing or inconsistent data, as well as the short follow-up time.

- Decisions about time interval were based more on professional preference rather than specific tumor characteristics.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. de Lacy has reported no relevant financial relationships. No outside funding source was disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A total of 1,506 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by total mesorectal excision were divided into three groups based on the time interval between therapy and surgery: short (8 weeks), intermediate (> 8 to 12 weeks), and long (> 12 weeks).

- The primary outcome was pathologic complete response, and secondary outcomes included other histopathologic results, perioperative events, and survival outcomes.

- Median follow-up was 33 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, a pathologic complete response was observed in 255 patients (17.2%).

- Compared with the intermediate interval (reference) group, investigators found no association between time interval and pathologic complete response in the short-interval (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-1.01) or long-interval groups (OR, 1.07; P = .70).