User login

By the numbers: Asthma-COPD overlap deaths

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.”

For females with asthma-COPD overlap, the age-adjusted death rate among adults aged 25 years and older dropped from 7.71 per million in 1999 to 4.01 in 2016, with corresponding rates of 6.70 and 3.01 per million for males, they reported.

In 1999-2016, a total of 18,766 U.S. decedents aged ≥25 years had both asthma and COPD assigned as the underlying or contributing cause of death (12,028 women and 6,738 men), for an overall death rate of 5.03 per million persons (women, 5.59; men, 4.30), data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

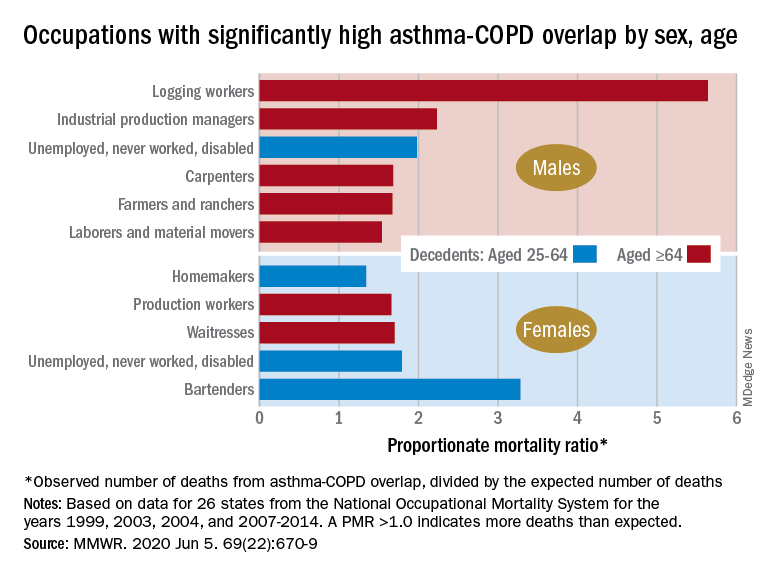

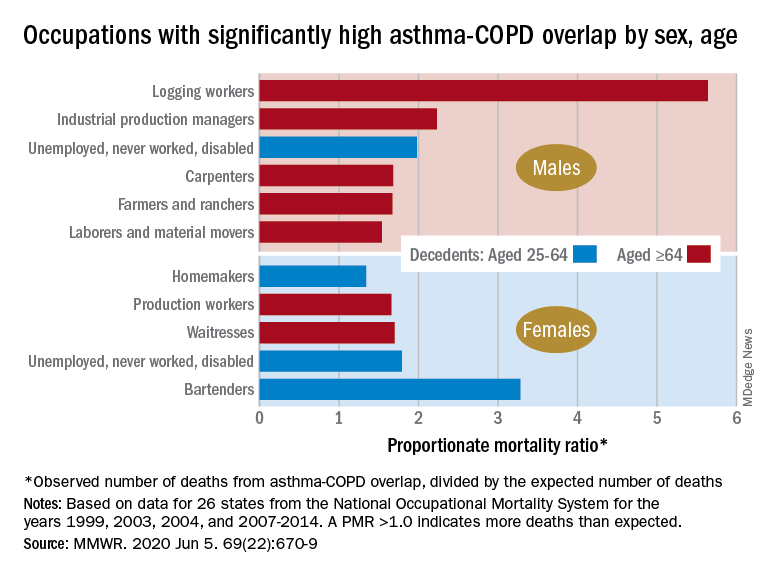

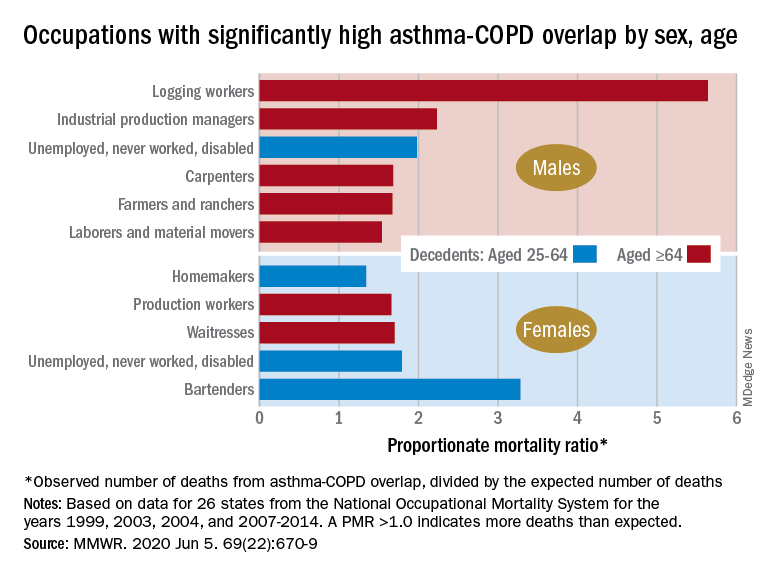

Additional analysis, based on the calculation of proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs), also showed that mortality varied by occupational status and age for both males and females, the investigators said, noting that workplace exposures, such as dusts and secondhand smoke, are known to cause both asthma and COPD.

The PMR represents the observed number of deaths from asthma-COPD overlap in a specified industry or occupation, divided by the expected number of deaths, so a value over 1.0 indicates that there were more deaths associated with the condition than expected, Ms. Dodd and her associates explained.

Among female decedents, the occupation with the highest PMR that was statistically significant was bartending at 3.28. For men, the highest significant PMR, 5.64, occurred in logging workers. Those rates, however, only applied to one of the two age groups: 25-64 years in women and ≥65 in men, based on data from the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance, which included information from 26 states for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2007-2014.

Occupationally speaking, the one area of common ground between males and females was lack of occupation. PMRs for those aged 25-64 years “were significantly elevated among men (1.98) and women (1.79) who were unemployed, never worked, or were disabled workers,” they said. PMRs were elevated for nonworking older males and females but were not significant.

The elevated PMRs suggest “that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity resulting in loss of employment [because] retired and unemployed persons might have left the workforce because of severe asthma or COPD,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Dodd KE et al. MMWR. 2020 Jun 5. 69(22):670-9.

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.”

For females with asthma-COPD overlap, the age-adjusted death rate among adults aged 25 years and older dropped from 7.71 per million in 1999 to 4.01 in 2016, with corresponding rates of 6.70 and 3.01 per million for males, they reported.

In 1999-2016, a total of 18,766 U.S. decedents aged ≥25 years had both asthma and COPD assigned as the underlying or contributing cause of death (12,028 women and 6,738 men), for an overall death rate of 5.03 per million persons (women, 5.59; men, 4.30), data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

Additional analysis, based on the calculation of proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs), also showed that mortality varied by occupational status and age for both males and females, the investigators said, noting that workplace exposures, such as dusts and secondhand smoke, are known to cause both asthma and COPD.

The PMR represents the observed number of deaths from asthma-COPD overlap in a specified industry or occupation, divided by the expected number of deaths, so a value over 1.0 indicates that there were more deaths associated with the condition than expected, Ms. Dodd and her associates explained.

Among female decedents, the occupation with the highest PMR that was statistically significant was bartending at 3.28. For men, the highest significant PMR, 5.64, occurred in logging workers. Those rates, however, only applied to one of the two age groups: 25-64 years in women and ≥65 in men, based on data from the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance, which included information from 26 states for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2007-2014.

Occupationally speaking, the one area of common ground between males and females was lack of occupation. PMRs for those aged 25-64 years “were significantly elevated among men (1.98) and women (1.79) who were unemployed, never worked, or were disabled workers,” they said. PMRs were elevated for nonworking older males and females but were not significant.

The elevated PMRs suggest “that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity resulting in loss of employment [because] retired and unemployed persons might have left the workforce because of severe asthma or COPD,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Dodd KE et al. MMWR. 2020 Jun 5. 69(22):670-9.

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.”

For females with asthma-COPD overlap, the age-adjusted death rate among adults aged 25 years and older dropped from 7.71 per million in 1999 to 4.01 in 2016, with corresponding rates of 6.70 and 3.01 per million for males, they reported.

In 1999-2016, a total of 18,766 U.S. decedents aged ≥25 years had both asthma and COPD assigned as the underlying or contributing cause of death (12,028 women and 6,738 men), for an overall death rate of 5.03 per million persons (women, 5.59; men, 4.30), data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

Additional analysis, based on the calculation of proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs), also showed that mortality varied by occupational status and age for both males and females, the investigators said, noting that workplace exposures, such as dusts and secondhand smoke, are known to cause both asthma and COPD.

The PMR represents the observed number of deaths from asthma-COPD overlap in a specified industry or occupation, divided by the expected number of deaths, so a value over 1.0 indicates that there were more deaths associated with the condition than expected, Ms. Dodd and her associates explained.

Among female decedents, the occupation with the highest PMR that was statistically significant was bartending at 3.28. For men, the highest significant PMR, 5.64, occurred in logging workers. Those rates, however, only applied to one of the two age groups: 25-64 years in women and ≥65 in men, based on data from the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance, which included information from 26 states for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2007-2014.

Occupationally speaking, the one area of common ground between males and females was lack of occupation. PMRs for those aged 25-64 years “were significantly elevated among men (1.98) and women (1.79) who were unemployed, never worked, or were disabled workers,” they said. PMRs were elevated for nonworking older males and females but were not significant.

The elevated PMRs suggest “that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity resulting in loss of employment [because] retired and unemployed persons might have left the workforce because of severe asthma or COPD,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Dodd KE et al. MMWR. 2020 Jun 5. 69(22):670-9.

FROM MMWR

FLU/SAL inhalers for COPD carry greater pneumonia risk

For well over a decade the elevated risk of pneumonia from inhaled corticosteroids for moderate to very severe COPD has been well documented, although the pneumonia risks from different types of ICSs have not been well understood.

Researchers from Taiwan have taken a step in to investigate this question with a nationwide cohort study that reported inhalers with budesonide and beclomethasone may have a lower pneumonia risk than that of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol inhalers (CHEST. 2020;157:117-29).

The study is the first to include beclomethasone-containing inhalers in a comparison of ICS/long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) fixed combinations to evaluate pneumonia risk, along with dose and drug properties, wrote Ting-Yu Chang, MS, of the Graduate Institute of Clinical Pharmacology at the College of Medicine, National Taiwan University in Taipei, and colleagues.

The study evaluated 42,393 people with COPD in the National Health Insurance Research Database who got at least two continuous prescriptions for three different types of inhalers:

- Budesonide/formoterol (BUD/FOR).

- Beclomethasone/formoterol (BEC/FOR).

- Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FLU/SAL).

The study included patients aged 40 years and older who used a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) or dry-powder inhaler (DPI) between January 2011 and June 2015.

Patient experience with adverse events (AEs) was a factor in risk stratification, Mr. Chang and colleagues noted. “For the comparison between the BEC/FOR MDI and FLU/SAL MDI, the lower risk associated with the BEC/FOR MDI was more prominent in patients without severe AE in the past year,” they wrote.

The study found that BUD/FOR DPI users had a 17% lower risk of severe pneumonia and a 12% lower risk of severe AEs than that of FLU/SAL DPI users. The risk difference in pneumonia remained significant after adjustment for the ICS-equivalent daily dose, but the spread for AEs didn’t.

BEC/FOR MDI users were 31% less likely to get severe pneumonia and 18% less likely to have severe AEs than were FLU/SAL MDI users, but that difference declined and became nonsignificant after adjustment for the ICS-equivalent daily dose.

The study also found that a high average daily dose (> 500 mcg/d) of FLU/SAL MDI carried a 66% greater risk of severe pneumonia, compared with that of low-dose users. Also, medium-dose BEC/FOR MDI users (FLU equivalent 299-499 mcg/d) had a 38% greater risk of severe pneumonia than low-dose (< 200 mcg/d) users.

The variable pneumonia risks may be linked to each ICS’s pharmacokinetics, specifically their distinct lipophilic properties, Mr. Chang and colleagues wrote. Fluticasone propionate is known to be more lipophilic than budesonide, and while beclomethasone is more lipophilic than both, as a prodrug it rapidly converts to lower lipophilicity upon contact with bronchial secretions. “In general, a lipophilic ICS has a longer retention time within the airway or lung tissue to exert local immunosuppression and reduce inflammation,” Mr. Chang and colleagues stated.

The Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology provided partial support for the study. Mr. Chang and colleagues have no relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Chang TY et al. CHEST. 2020;157:117-29.

For well over a decade the elevated risk of pneumonia from inhaled corticosteroids for moderate to very severe COPD has been well documented, although the pneumonia risks from different types of ICSs have not been well understood.

Researchers from Taiwan have taken a step in to investigate this question with a nationwide cohort study that reported inhalers with budesonide and beclomethasone may have a lower pneumonia risk than that of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol inhalers (CHEST. 2020;157:117-29).

The study is the first to include beclomethasone-containing inhalers in a comparison of ICS/long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) fixed combinations to evaluate pneumonia risk, along with dose and drug properties, wrote Ting-Yu Chang, MS, of the Graduate Institute of Clinical Pharmacology at the College of Medicine, National Taiwan University in Taipei, and colleagues.

The study evaluated 42,393 people with COPD in the National Health Insurance Research Database who got at least two continuous prescriptions for three different types of inhalers:

- Budesonide/formoterol (BUD/FOR).

- Beclomethasone/formoterol (BEC/FOR).

- Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FLU/SAL).

The study included patients aged 40 years and older who used a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) or dry-powder inhaler (DPI) between January 2011 and June 2015.

Patient experience with adverse events (AEs) was a factor in risk stratification, Mr. Chang and colleagues noted. “For the comparison between the BEC/FOR MDI and FLU/SAL MDI, the lower risk associated with the BEC/FOR MDI was more prominent in patients without severe AE in the past year,” they wrote.

The study found that BUD/FOR DPI users had a 17% lower risk of severe pneumonia and a 12% lower risk of severe AEs than that of FLU/SAL DPI users. The risk difference in pneumonia remained significant after adjustment for the ICS-equivalent daily dose, but the spread for AEs didn’t.

BEC/FOR MDI users were 31% less likely to get severe pneumonia and 18% less likely to have severe AEs than were FLU/SAL MDI users, but that difference declined and became nonsignificant after adjustment for the ICS-equivalent daily dose.

The study also found that a high average daily dose (> 500 mcg/d) of FLU/SAL MDI carried a 66% greater risk of severe pneumonia, compared with that of low-dose users. Also, medium-dose BEC/FOR MDI users (FLU equivalent 299-499 mcg/d) had a 38% greater risk of severe pneumonia than low-dose (< 200 mcg/d) users.

The variable pneumonia risks may be linked to each ICS’s pharmacokinetics, specifically their distinct lipophilic properties, Mr. Chang and colleagues wrote. Fluticasone propionate is known to be more lipophilic than budesonide, and while beclomethasone is more lipophilic than both, as a prodrug it rapidly converts to lower lipophilicity upon contact with bronchial secretions. “In general, a lipophilic ICS has a longer retention time within the airway or lung tissue to exert local immunosuppression and reduce inflammation,” Mr. Chang and colleagues stated.

The Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology provided partial support for the study. Mr. Chang and colleagues have no relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Chang TY et al. CHEST. 2020;157:117-29.

For well over a decade the elevated risk of pneumonia from inhaled corticosteroids for moderate to very severe COPD has been well documented, although the pneumonia risks from different types of ICSs have not been well understood.

Researchers from Taiwan have taken a step in to investigate this question with a nationwide cohort study that reported inhalers with budesonide and beclomethasone may have a lower pneumonia risk than that of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol inhalers (CHEST. 2020;157:117-29).

The study is the first to include beclomethasone-containing inhalers in a comparison of ICS/long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) fixed combinations to evaluate pneumonia risk, along with dose and drug properties, wrote Ting-Yu Chang, MS, of the Graduate Institute of Clinical Pharmacology at the College of Medicine, National Taiwan University in Taipei, and colleagues.

The study evaluated 42,393 people with COPD in the National Health Insurance Research Database who got at least two continuous prescriptions for three different types of inhalers:

- Budesonide/formoterol (BUD/FOR).

- Beclomethasone/formoterol (BEC/FOR).

- Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FLU/SAL).

The study included patients aged 40 years and older who used a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) or dry-powder inhaler (DPI) between January 2011 and June 2015.

Patient experience with adverse events (AEs) was a factor in risk stratification, Mr. Chang and colleagues noted. “For the comparison between the BEC/FOR MDI and FLU/SAL MDI, the lower risk associated with the BEC/FOR MDI was more prominent in patients without severe AE in the past year,” they wrote.

The study found that BUD/FOR DPI users had a 17% lower risk of severe pneumonia and a 12% lower risk of severe AEs than that of FLU/SAL DPI users. The risk difference in pneumonia remained significant after adjustment for the ICS-equivalent daily dose, but the spread for AEs didn’t.

BEC/FOR MDI users were 31% less likely to get severe pneumonia and 18% less likely to have severe AEs than were FLU/SAL MDI users, but that difference declined and became nonsignificant after adjustment for the ICS-equivalent daily dose.

The study also found that a high average daily dose (> 500 mcg/d) of FLU/SAL MDI carried a 66% greater risk of severe pneumonia, compared with that of low-dose users. Also, medium-dose BEC/FOR MDI users (FLU equivalent 299-499 mcg/d) had a 38% greater risk of severe pneumonia than low-dose (< 200 mcg/d) users.

The variable pneumonia risks may be linked to each ICS’s pharmacokinetics, specifically their distinct lipophilic properties, Mr. Chang and colleagues wrote. Fluticasone propionate is known to be more lipophilic than budesonide, and while beclomethasone is more lipophilic than both, as a prodrug it rapidly converts to lower lipophilicity upon contact with bronchial secretions. “In general, a lipophilic ICS has a longer retention time within the airway or lung tissue to exert local immunosuppression and reduce inflammation,” Mr. Chang and colleagues stated.

The Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology provided partial support for the study. Mr. Chang and colleagues have no relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Chang TY et al. CHEST. 2020;157:117-29.

FROM CHEST

Low IgG levels in COPD patients linked to increased risk of hospitalization

Among patients with COPD, the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia confers a nearly 30% increased risk of hospitalization, results from a pooled analysis of four studies showed.

“Mechanistic studies are still warranted to better elucidate how IgG and other immunoglobulins, in particular IgA, may contribute to the local airway host defense,” researchers led by Fernando Sergio Leitao Filho, MD, PhD, wrote in a study published in Chest (2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.058). “Nevertheless, our results raise the possibility that, in select COPD patients, IgG replacement therapy may be effective in reducing the risk of COPD hospitalizations. Given the growing rate of COPD hospitalization in the U.S. and elsewhere, there is a pressing need for a large well-designed trial to test this hypothesis.”

In an effort to evaluate the effect of IgG levels on the cumulative incidence of COPD hospitalizations, Dr. Leitao Filho, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues drew from 2,259 patients who participated in four different trials: Azithromycin for Prevention of Exacerbations of COPD (MACRO), Simvastatin for the Prevention of Exacerbations in Moderate and Severe COPD (STATCOPE), the Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT), and COPD Activity: Serotonin Transporter, Cytokines and Depression (CASCADE). The mean baseline age of study participants was 66 years, and 641 (28.4%) had hypogammaglobulinemia, which was defined as having a serum IgG levels of less than 7.0 g/L, while the remainder had normal IgG levels.

The pooled meta-analysis, which is believed to be the largest of its kind, revealed that the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia was associated with an incidence of COPD hospitalizations that was 1.29-fold higher than that observed among participants who had normal IgG levels (P = .01). The incidence was even higher among patients with prior COPD admissions (pooled subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.58; P < .01), yet the risk of COPD admissions was similar between IgG groups in patients with no prior hospitalizations (pooled SHR, 1.15; P = .34). Patients with hypogammaglobulinemia also showed significantly higher rates of COPD hospitalizations per person-year, compared with their counterparts who had normal IgG levels (0.48 vs. 0.29, respectively; P < .001.)

The authors acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that they measured serum IgG levels only at baseline “when participants were clinically stable; thus, the variability of IgG levels in a given individual over time and during the course of an AECOPD [severe acute exacerbation of COPD] is uncertain. Secondly, clinical data on corticosteroid use (formulations, dose, and length of use) were not readily available. However, systemic steroid use (one or more courses due to AECOPD prior to study entry) was accounted for in our analyses.”

The MACRO, STATCOPE, LOTT trials, and the CASCADE cohort were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and Department of Health & Human Services. The current study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and BC Lung Association. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Leitao Filho SF et al. Chest. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.058.

Among patients with COPD, the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia confers a nearly 30% increased risk of hospitalization, results from a pooled analysis of four studies showed.

“Mechanistic studies are still warranted to better elucidate how IgG and other immunoglobulins, in particular IgA, may contribute to the local airway host defense,” researchers led by Fernando Sergio Leitao Filho, MD, PhD, wrote in a study published in Chest (2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.058). “Nevertheless, our results raise the possibility that, in select COPD patients, IgG replacement therapy may be effective in reducing the risk of COPD hospitalizations. Given the growing rate of COPD hospitalization in the U.S. and elsewhere, there is a pressing need for a large well-designed trial to test this hypothesis.”

In an effort to evaluate the effect of IgG levels on the cumulative incidence of COPD hospitalizations, Dr. Leitao Filho, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues drew from 2,259 patients who participated in four different trials: Azithromycin for Prevention of Exacerbations of COPD (MACRO), Simvastatin for the Prevention of Exacerbations in Moderate and Severe COPD (STATCOPE), the Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT), and COPD Activity: Serotonin Transporter, Cytokines and Depression (CASCADE). The mean baseline age of study participants was 66 years, and 641 (28.4%) had hypogammaglobulinemia, which was defined as having a serum IgG levels of less than 7.0 g/L, while the remainder had normal IgG levels.

The pooled meta-analysis, which is believed to be the largest of its kind, revealed that the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia was associated with an incidence of COPD hospitalizations that was 1.29-fold higher than that observed among participants who had normal IgG levels (P = .01). The incidence was even higher among patients with prior COPD admissions (pooled subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.58; P < .01), yet the risk of COPD admissions was similar between IgG groups in patients with no prior hospitalizations (pooled SHR, 1.15; P = .34). Patients with hypogammaglobulinemia also showed significantly higher rates of COPD hospitalizations per person-year, compared with their counterparts who had normal IgG levels (0.48 vs. 0.29, respectively; P < .001.)

The authors acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that they measured serum IgG levels only at baseline “when participants were clinically stable; thus, the variability of IgG levels in a given individual over time and during the course of an AECOPD [severe acute exacerbation of COPD] is uncertain. Secondly, clinical data on corticosteroid use (formulations, dose, and length of use) were not readily available. However, systemic steroid use (one or more courses due to AECOPD prior to study entry) was accounted for in our analyses.”

The MACRO, STATCOPE, LOTT trials, and the CASCADE cohort were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and Department of Health & Human Services. The current study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and BC Lung Association. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Leitao Filho SF et al. Chest. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.058.

Among patients with COPD, the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia confers a nearly 30% increased risk of hospitalization, results from a pooled analysis of four studies showed.

“Mechanistic studies are still warranted to better elucidate how IgG and other immunoglobulins, in particular IgA, may contribute to the local airway host defense,” researchers led by Fernando Sergio Leitao Filho, MD, PhD, wrote in a study published in Chest (2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.058). “Nevertheless, our results raise the possibility that, in select COPD patients, IgG replacement therapy may be effective in reducing the risk of COPD hospitalizations. Given the growing rate of COPD hospitalization in the U.S. and elsewhere, there is a pressing need for a large well-designed trial to test this hypothesis.”

In an effort to evaluate the effect of IgG levels on the cumulative incidence of COPD hospitalizations, Dr. Leitao Filho, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues drew from 2,259 patients who participated in four different trials: Azithromycin for Prevention of Exacerbations of COPD (MACRO), Simvastatin for the Prevention of Exacerbations in Moderate and Severe COPD (STATCOPE), the Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT), and COPD Activity: Serotonin Transporter, Cytokines and Depression (CASCADE). The mean baseline age of study participants was 66 years, and 641 (28.4%) had hypogammaglobulinemia, which was defined as having a serum IgG levels of less than 7.0 g/L, while the remainder had normal IgG levels.

The pooled meta-analysis, which is believed to be the largest of its kind, revealed that the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia was associated with an incidence of COPD hospitalizations that was 1.29-fold higher than that observed among participants who had normal IgG levels (P = .01). The incidence was even higher among patients with prior COPD admissions (pooled subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.58; P < .01), yet the risk of COPD admissions was similar between IgG groups in patients with no prior hospitalizations (pooled SHR, 1.15; P = .34). Patients with hypogammaglobulinemia also showed significantly higher rates of COPD hospitalizations per person-year, compared with their counterparts who had normal IgG levels (0.48 vs. 0.29, respectively; P < .001.)

The authors acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that they measured serum IgG levels only at baseline “when participants were clinically stable; thus, the variability of IgG levels in a given individual over time and during the course of an AECOPD [severe acute exacerbation of COPD] is uncertain. Secondly, clinical data on corticosteroid use (formulations, dose, and length of use) were not readily available. However, systemic steroid use (one or more courses due to AECOPD prior to study entry) was accounted for in our analyses.”

The MACRO, STATCOPE, LOTT trials, and the CASCADE cohort were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and Department of Health & Human Services. The current study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and BC Lung Association. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Leitao Filho SF et al. Chest. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.058.

FROM CHEST

Masks, fear, and loss of connection in the era of COVID-19

Over the din of the negative pressure machine, I shouted goodbye to my patient and zipped my way out of one of the little plastic enclosures in our ED and carefully shed my gloves, gown, and face shield, leaving on my precious mask. I discarded the rest with disgust and a bit of fear. I thought, “This is a whole new world, and I hate it.”

I feel as if I am constantly battling the fear of dying from COVID-19 but am doing the best I can, given the circumstances at hand. I have the proper equipment and use it well. My work still brings meaning: I serve those in need without hesitation. The problem is that deep feeling of connection with patients, which is such an important part of this work, feels like fraying threads moving further apart because of the havoc this virus has wrought. A few weeks ago, the intricate fabric of what it is to be human connected me to patients through the basics: touch, facial expressions, a physical proximity, and openhearted, honest dialogue. Much of that’s gone, and while I can carry on, I will surely burn out if I can’t figure out how to get at least some of that connection back.

Overwhelmed by the amount of information I need to process daily, I had not been thinking about the interpersonal side of the pandemic for the first weeks. I felt it leaving the ED that morning and later that day, and I felt it again with Ms. Z, who was not even suspected of having COVID. She is a 62-year-old I interviewed with the help of a translator phone. At the end of our encounter, she said “But doctor, will you make my tumor go away?” From across the room, I said, “I will try.” I saw her eyes dampen as I made a hasty exit, following protocol to limit time in the room of all patients.

Typically, leaving a patient’s room, I would feel a fullness associated with a sense of meaning. How did I feel after that? In that moment, mostly ashamed at my lack of compassion during my time with Ms. Z. Then, with further reflection, tense from all things COVID-19! Having an amped-up sympathetic nervous system is understandable, but it’s not where we want to be for our compassion to flow.

We connect best when our parasympathetic nervous system is predominant. So much of the stimuli we need to activate that part of the nervous system is gone. There is a virtuous cycle, much of it unconscious, where something positive leads to more positivity, which is crucial to meaningful patient encounters. We read each other’s facial expressions, hear the tone of voice, and as we pick up subtle cues from our patient, our nervous system is further engaged and our hearts opened.

The specter of COVID-19 has us battling a negative spiral of stress and fear. For the most part, I try to keep that from consuming me, but it clearly saps my energy during encounters. In the same way we need to marshal our resources to battle both the stress and the disease itself, we need to actively engage pro-social elements of providing care to maintain our compassion. Clearly, I needed a more concerted effort to kick start this virtuous cycle of compassion.

My next patient was Ms. J., a 55-year-old with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who came in the night before with shortness of breath. Her slight frame shook from coughing as I entered the room. I did not think she had COVID-19, but we were ruling it out.

We reviewed how she felt since admission, and I performed a hasty exam and stepped back across the room. She coughed again and said, “I feel so weak, and the world feels so crazy; tell it to me straight.” Then looking in my eyes, “I am going to make it, doc?”

I took my cue from her; I walked back to the bedside, placed a gloved hand on her shoulder and with the other, I took her hand. I bent forward just a little. Making eye contact and attempting a comforting tone of voice, I said, “Everyone is a little scared, including me. We need each other more than ever these days. We will do our best for you. That means thoughtful medical care and a whole lot of love! And, truly, I don’t think you are dying; this is just one of your COPD flares.”

“God bless you!” she said, squeezing my hand as a tear rolled down her cheek.

“Bless you, too. We all need blessing with this madness going on,” I replied. Despite the mask, I am sure she saw the smile in my eyes. “Thanks for being the beautiful person you are and opening up to me. That’s the way we will make it through this. I will see you tomorrow.” Backing away, hands together in prayer, I gave a little bow and left the room.

With Ms. J.’s help, I began to figure it out. To tackle the stress of COVID, we need to be very direct – almost to the point of exaggeration – to make sure our words and actions convey what we need to express. William James, the father of psychology, believed that if you force a smile, your emotions would follow. The neural pathways could work backward in that way. He said, “If you want a quality, act as if you have it.” The modern translation would be, “Fake it ’til you make it.’ ” You may be feeling stressed, but with a deep breath and a moment’s reflection on the suffering of that patient you are about to see, you can turn the tide on anxiety and give those under your care what they need.

These are unprecedented times; anxiety abounds. While we can aspire to positivity, there are times when we simply can’t muster showing it. Alternatively, as I experienced with Ms. J., honesty and vulnerability can open the door to meaningful connection. This can be quite powerful when we, as physicians, open up to our patients.

People are yearning for deep connection, and we should attempt to deliver it with:

- Touch (as we can) to convey connection.

- Body language that adds emphasis to our message and our emotions that may go above and beyond what we are used to.

- Tone of voice that enhances our words.

- Talk that emphasizes the big stuff, such as love, fear, connection and community

With gloves, masks, distance, and fear between and us and our patients, we need to actively engage our pro-social tools to turn the negative spiral of fear into the virtuous cycle of positive emotions that promotes healing of our patients and emotional engagement for those providing their care.

Dr. Hass was trained in family medicine at University of California, San Francisco, after receiving his medical degree from the McGill University faculty of medicine, Montreal. He works as a hospitalist with Sutter Health in Oakland, Calif. He is an adviser on health and health care for the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley and clinical faculty at UCSF School of Medicine. This article appeared initially at The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Over the din of the negative pressure machine, I shouted goodbye to my patient and zipped my way out of one of the little plastic enclosures in our ED and carefully shed my gloves, gown, and face shield, leaving on my precious mask. I discarded the rest with disgust and a bit of fear. I thought, “This is a whole new world, and I hate it.”

I feel as if I am constantly battling the fear of dying from COVID-19 but am doing the best I can, given the circumstances at hand. I have the proper equipment and use it well. My work still brings meaning: I serve those in need without hesitation. The problem is that deep feeling of connection with patients, which is such an important part of this work, feels like fraying threads moving further apart because of the havoc this virus has wrought. A few weeks ago, the intricate fabric of what it is to be human connected me to patients through the basics: touch, facial expressions, a physical proximity, and openhearted, honest dialogue. Much of that’s gone, and while I can carry on, I will surely burn out if I can’t figure out how to get at least some of that connection back.

Overwhelmed by the amount of information I need to process daily, I had not been thinking about the interpersonal side of the pandemic for the first weeks. I felt it leaving the ED that morning and later that day, and I felt it again with Ms. Z, who was not even suspected of having COVID. She is a 62-year-old I interviewed with the help of a translator phone. At the end of our encounter, she said “But doctor, will you make my tumor go away?” From across the room, I said, “I will try.” I saw her eyes dampen as I made a hasty exit, following protocol to limit time in the room of all patients.

Typically, leaving a patient’s room, I would feel a fullness associated with a sense of meaning. How did I feel after that? In that moment, mostly ashamed at my lack of compassion during my time with Ms. Z. Then, with further reflection, tense from all things COVID-19! Having an amped-up sympathetic nervous system is understandable, but it’s not where we want to be for our compassion to flow.

We connect best when our parasympathetic nervous system is predominant. So much of the stimuli we need to activate that part of the nervous system is gone. There is a virtuous cycle, much of it unconscious, where something positive leads to more positivity, which is crucial to meaningful patient encounters. We read each other’s facial expressions, hear the tone of voice, and as we pick up subtle cues from our patient, our nervous system is further engaged and our hearts opened.

The specter of COVID-19 has us battling a negative spiral of stress and fear. For the most part, I try to keep that from consuming me, but it clearly saps my energy during encounters. In the same way we need to marshal our resources to battle both the stress and the disease itself, we need to actively engage pro-social elements of providing care to maintain our compassion. Clearly, I needed a more concerted effort to kick start this virtuous cycle of compassion.

My next patient was Ms. J., a 55-year-old with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who came in the night before with shortness of breath. Her slight frame shook from coughing as I entered the room. I did not think she had COVID-19, but we were ruling it out.

We reviewed how she felt since admission, and I performed a hasty exam and stepped back across the room. She coughed again and said, “I feel so weak, and the world feels so crazy; tell it to me straight.” Then looking in my eyes, “I am going to make it, doc?”

I took my cue from her; I walked back to the bedside, placed a gloved hand on her shoulder and with the other, I took her hand. I bent forward just a little. Making eye contact and attempting a comforting tone of voice, I said, “Everyone is a little scared, including me. We need each other more than ever these days. We will do our best for you. That means thoughtful medical care and a whole lot of love! And, truly, I don’t think you are dying; this is just one of your COPD flares.”

“God bless you!” she said, squeezing my hand as a tear rolled down her cheek.

“Bless you, too. We all need blessing with this madness going on,” I replied. Despite the mask, I am sure she saw the smile in my eyes. “Thanks for being the beautiful person you are and opening up to me. That’s the way we will make it through this. I will see you tomorrow.” Backing away, hands together in prayer, I gave a little bow and left the room.

With Ms. J.’s help, I began to figure it out. To tackle the stress of COVID, we need to be very direct – almost to the point of exaggeration – to make sure our words and actions convey what we need to express. William James, the father of psychology, believed that if you force a smile, your emotions would follow. The neural pathways could work backward in that way. He said, “If you want a quality, act as if you have it.” The modern translation would be, “Fake it ’til you make it.’ ” You may be feeling stressed, but with a deep breath and a moment’s reflection on the suffering of that patient you are about to see, you can turn the tide on anxiety and give those under your care what they need.

These are unprecedented times; anxiety abounds. While we can aspire to positivity, there are times when we simply can’t muster showing it. Alternatively, as I experienced with Ms. J., honesty and vulnerability can open the door to meaningful connection. This can be quite powerful when we, as physicians, open up to our patients.

People are yearning for deep connection, and we should attempt to deliver it with:

- Touch (as we can) to convey connection.

- Body language that adds emphasis to our message and our emotions that may go above and beyond what we are used to.

- Tone of voice that enhances our words.

- Talk that emphasizes the big stuff, such as love, fear, connection and community

With gloves, masks, distance, and fear between and us and our patients, we need to actively engage our pro-social tools to turn the negative spiral of fear into the virtuous cycle of positive emotions that promotes healing of our patients and emotional engagement for those providing their care.

Dr. Hass was trained in family medicine at University of California, San Francisco, after receiving his medical degree from the McGill University faculty of medicine, Montreal. He works as a hospitalist with Sutter Health in Oakland, Calif. He is an adviser on health and health care for the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley and clinical faculty at UCSF School of Medicine. This article appeared initially at The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Over the din of the negative pressure machine, I shouted goodbye to my patient and zipped my way out of one of the little plastic enclosures in our ED and carefully shed my gloves, gown, and face shield, leaving on my precious mask. I discarded the rest with disgust and a bit of fear. I thought, “This is a whole new world, and I hate it.”

I feel as if I am constantly battling the fear of dying from COVID-19 but am doing the best I can, given the circumstances at hand. I have the proper equipment and use it well. My work still brings meaning: I serve those in need without hesitation. The problem is that deep feeling of connection with patients, which is such an important part of this work, feels like fraying threads moving further apart because of the havoc this virus has wrought. A few weeks ago, the intricate fabric of what it is to be human connected me to patients through the basics: touch, facial expressions, a physical proximity, and openhearted, honest dialogue. Much of that’s gone, and while I can carry on, I will surely burn out if I can’t figure out how to get at least some of that connection back.

Overwhelmed by the amount of information I need to process daily, I had not been thinking about the interpersonal side of the pandemic for the first weeks. I felt it leaving the ED that morning and later that day, and I felt it again with Ms. Z, who was not even suspected of having COVID. She is a 62-year-old I interviewed with the help of a translator phone. At the end of our encounter, she said “But doctor, will you make my tumor go away?” From across the room, I said, “I will try.” I saw her eyes dampen as I made a hasty exit, following protocol to limit time in the room of all patients.

Typically, leaving a patient’s room, I would feel a fullness associated with a sense of meaning. How did I feel after that? In that moment, mostly ashamed at my lack of compassion during my time with Ms. Z. Then, with further reflection, tense from all things COVID-19! Having an amped-up sympathetic nervous system is understandable, but it’s not where we want to be for our compassion to flow.

We connect best when our parasympathetic nervous system is predominant. So much of the stimuli we need to activate that part of the nervous system is gone. There is a virtuous cycle, much of it unconscious, where something positive leads to more positivity, which is crucial to meaningful patient encounters. We read each other’s facial expressions, hear the tone of voice, and as we pick up subtle cues from our patient, our nervous system is further engaged and our hearts opened.

The specter of COVID-19 has us battling a negative spiral of stress and fear. For the most part, I try to keep that from consuming me, but it clearly saps my energy during encounters. In the same way we need to marshal our resources to battle both the stress and the disease itself, we need to actively engage pro-social elements of providing care to maintain our compassion. Clearly, I needed a more concerted effort to kick start this virtuous cycle of compassion.

My next patient was Ms. J., a 55-year-old with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who came in the night before with shortness of breath. Her slight frame shook from coughing as I entered the room. I did not think she had COVID-19, but we were ruling it out.

We reviewed how she felt since admission, and I performed a hasty exam and stepped back across the room. She coughed again and said, “I feel so weak, and the world feels so crazy; tell it to me straight.” Then looking in my eyes, “I am going to make it, doc?”

I took my cue from her; I walked back to the bedside, placed a gloved hand on her shoulder and with the other, I took her hand. I bent forward just a little. Making eye contact and attempting a comforting tone of voice, I said, “Everyone is a little scared, including me. We need each other more than ever these days. We will do our best for you. That means thoughtful medical care and a whole lot of love! And, truly, I don’t think you are dying; this is just one of your COPD flares.”

“God bless you!” she said, squeezing my hand as a tear rolled down her cheek.

“Bless you, too. We all need blessing with this madness going on,” I replied. Despite the mask, I am sure she saw the smile in my eyes. “Thanks for being the beautiful person you are and opening up to me. That’s the way we will make it through this. I will see you tomorrow.” Backing away, hands together in prayer, I gave a little bow and left the room.

With Ms. J.’s help, I began to figure it out. To tackle the stress of COVID, we need to be very direct – almost to the point of exaggeration – to make sure our words and actions convey what we need to express. William James, the father of psychology, believed that if you force a smile, your emotions would follow. The neural pathways could work backward in that way. He said, “If you want a quality, act as if you have it.” The modern translation would be, “Fake it ’til you make it.’ ” You may be feeling stressed, but with a deep breath and a moment’s reflection on the suffering of that patient you are about to see, you can turn the tide on anxiety and give those under your care what they need.

These are unprecedented times; anxiety abounds. While we can aspire to positivity, there are times when we simply can’t muster showing it. Alternatively, as I experienced with Ms. J., honesty and vulnerability can open the door to meaningful connection. This can be quite powerful when we, as physicians, open up to our patients.

People are yearning for deep connection, and we should attempt to deliver it with:

- Touch (as we can) to convey connection.

- Body language that adds emphasis to our message and our emotions that may go above and beyond what we are used to.

- Tone of voice that enhances our words.

- Talk that emphasizes the big stuff, such as love, fear, connection and community

With gloves, masks, distance, and fear between and us and our patients, we need to actively engage our pro-social tools to turn the negative spiral of fear into the virtuous cycle of positive emotions that promotes healing of our patients and emotional engagement for those providing their care.

Dr. Hass was trained in family medicine at University of California, San Francisco, after receiving his medical degree from the McGill University faculty of medicine, Montreal. He works as a hospitalist with Sutter Health in Oakland, Calif. He is an adviser on health and health care for the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley and clinical faculty at UCSF School of Medicine. This article appeared initially at The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

The third surge: Are we prepared for the non-COVID crisis?

Over the last several weeks, hospitals and health systems have focused on the COVID-19 epidemic, preparing and expanding bed capacities for the surge of admissions both in intensive care and medical units. An indirect impact of this has been the reduction in outpatient staffing and resources, with the shifting of staff for inpatient care. Many areas seem to have passed the peak in the number of cases and are now seeing a plateau or downward trend in the admissions to acute care facilities.

During this period, there has been a noticeable downtrend in patients being evaluated in the ED, or admitted for decompensation of chronic conditions like heart failure, COPD and diabetes mellitus, or such acute conditions as stroke and MI. Studies from Italy and Spain, and closer to home from Atlanta and Boston, point to a significant decrease in numbers of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admissions.1 Duke Health saw a decrease in stroke admissions in their hospitals by 34%.2

One could argue that these patients are in fact presenting with COVID-19 or similar symptoms as is evidenced by the studies linking the severity of SARS-Co-V2 infection to chronic conditions like diabetes mellitus and obesity.2 On the other hand, the message of social isolation and avoidance of nonurgent visits could lead to delays in care resulting in patients presenting sicker and in advanced stages.3 Also, this has not been limited to the adult population. For example, reports indicate that visits to WakeMed’s pediatric emergency rooms in Wake County, N.C., were down by 60%.2

We could well be seeing a calm before the storm. While it is anticipated that there may be a second surge of COVID-19 cases, health systems would do well to be prepared for the “third surge,” consisting of patients coming in with chronic medical conditions for which they have been, so far, avoiding follow-up and managing at home, and acute medical conditions with delayed diagnoses. The impact could likely be more in the subset of patients with limited access to health care, including medications and follow-up, resulting in a disproportionate burden on safety-net hospitals.

Compounding this issue would be the economic impact of the current crisis on health systems, their staffing, and resources. Several major organizations have already proposed budget cuts and reduction of the workforce, raising significant concerns about the future of health care workers who put their lives at risk during this pandemic.4 There is no guarantee that the federal funding provided by the stimulus packages will save jobs in the health care industry. This problem needs new leadership thinking, and every organization that puts employees over profits margins will have a long-term impact on communities.

Another area of concern is a shift in resources and workflow from ambulatory to inpatient settings for the COVID-19 pandemic, and the need for revamping the ambulatory services with reshifting the workforce. As COVID-19 cases plateau, the resurgence of non-COVID–related admissions will require additional help in inpatient settings. Prioritizing the ambulatory services based on financial benefits versus patient outcomes is also a major challenge to leadership.5

Lastly, the current health care crisis has led to significant stress, both emotional and physical, among frontline caregivers, increasing the risk of burnout.6 How leadership helps health care workers to cope with these stressors, and the resources they provide, is going to play a key role in long term retention of their talent, and will reflect on the organizational culture. Though it might seem trivial, posttraumatic stress disorder related to this is already obvious, and health care leadership needs to put every effort in providing the resources to help prevent burnout, in partnership with national organizations like the Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians.

The expansion of telemedicine has provided a unique opportunity to address several of these issues while maintaining the nonpharmacologic interventions to fight the epidemic, and keeping the cost curve as low as possible.7 Extension of these services to all ambulatory service lines, including home health and therapy, is the next big step in the new health care era. Virtual check-ins by physicians, advance practice clinicians, and home care nurses could help alleviate the concerns regarding delays in care of patients with chronic conditions, and help identify those at risk. This would also be of help with staffing shortages, and possibly provide much needed support to frontline providers.

Dr. Prasad is currently medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He was previously quality and utilization officer and chief of the medical staff at Aurora Sinai Medical Center. Dr. Prasad is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS Committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin Chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist in the UMMC School of Medicine.

References

1. Wood S. TCTMD. 2020 Apr 2. “The mystery of the missing STEMIs during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

2. Stradling R. The News & Observer. 2020 Apr 21. “Fewer people are going to Triangle [N.C.] emergency rooms, and that could be a bad thing.”

3. Kasanagottu K. USA Today. 2020 Apr 15. “Don’t delay care for chronic illness over coronavirus. It’s bad for you and for hospitals.”

4. Snowbeck C. The Star Tribune. 2020 Apr 11. “Mayo Clinic cutting pay for more than 20,000 workers.”

5. LaPointe J. RevCycle Intelligence. 2020 Mar 31. “How much will the COVID-19 pandemic cost hospitals?”

6. Gavidia M. AJMC. 2020 Mar 31. “Sleep, physician burnout linked amid COVID-19 pandemic.”

7. Hollander JE and Carr BG. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1679-81. “Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19.”

Over the last several weeks, hospitals and health systems have focused on the COVID-19 epidemic, preparing and expanding bed capacities for the surge of admissions both in intensive care and medical units. An indirect impact of this has been the reduction in outpatient staffing and resources, with the shifting of staff for inpatient care. Many areas seem to have passed the peak in the number of cases and are now seeing a plateau or downward trend in the admissions to acute care facilities.

During this period, there has been a noticeable downtrend in patients being evaluated in the ED, or admitted for decompensation of chronic conditions like heart failure, COPD and diabetes mellitus, or such acute conditions as stroke and MI. Studies from Italy and Spain, and closer to home from Atlanta and Boston, point to a significant decrease in numbers of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admissions.1 Duke Health saw a decrease in stroke admissions in their hospitals by 34%.2

One could argue that these patients are in fact presenting with COVID-19 or similar symptoms as is evidenced by the studies linking the severity of SARS-Co-V2 infection to chronic conditions like diabetes mellitus and obesity.2 On the other hand, the message of social isolation and avoidance of nonurgent visits could lead to delays in care resulting in patients presenting sicker and in advanced stages.3 Also, this has not been limited to the adult population. For example, reports indicate that visits to WakeMed’s pediatric emergency rooms in Wake County, N.C., were down by 60%.2

We could well be seeing a calm before the storm. While it is anticipated that there may be a second surge of COVID-19 cases, health systems would do well to be prepared for the “third surge,” consisting of patients coming in with chronic medical conditions for which they have been, so far, avoiding follow-up and managing at home, and acute medical conditions with delayed diagnoses. The impact could likely be more in the subset of patients with limited access to health care, including medications and follow-up, resulting in a disproportionate burden on safety-net hospitals.

Compounding this issue would be the economic impact of the current crisis on health systems, their staffing, and resources. Several major organizations have already proposed budget cuts and reduction of the workforce, raising significant concerns about the future of health care workers who put their lives at risk during this pandemic.4 There is no guarantee that the federal funding provided by the stimulus packages will save jobs in the health care industry. This problem needs new leadership thinking, and every organization that puts employees over profits margins will have a long-term impact on communities.

Another area of concern is a shift in resources and workflow from ambulatory to inpatient settings for the COVID-19 pandemic, and the need for revamping the ambulatory services with reshifting the workforce. As COVID-19 cases plateau, the resurgence of non-COVID–related admissions will require additional help in inpatient settings. Prioritizing the ambulatory services based on financial benefits versus patient outcomes is also a major challenge to leadership.5

Lastly, the current health care crisis has led to significant stress, both emotional and physical, among frontline caregivers, increasing the risk of burnout.6 How leadership helps health care workers to cope with these stressors, and the resources they provide, is going to play a key role in long term retention of their talent, and will reflect on the organizational culture. Though it might seem trivial, posttraumatic stress disorder related to this is already obvious, and health care leadership needs to put every effort in providing the resources to help prevent burnout, in partnership with national organizations like the Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians.

The expansion of telemedicine has provided a unique opportunity to address several of these issues while maintaining the nonpharmacologic interventions to fight the epidemic, and keeping the cost curve as low as possible.7 Extension of these services to all ambulatory service lines, including home health and therapy, is the next big step in the new health care era. Virtual check-ins by physicians, advance practice clinicians, and home care nurses could help alleviate the concerns regarding delays in care of patients with chronic conditions, and help identify those at risk. This would also be of help with staffing shortages, and possibly provide much needed support to frontline providers.

Dr. Prasad is currently medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He was previously quality and utilization officer and chief of the medical staff at Aurora Sinai Medical Center. Dr. Prasad is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS Committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin Chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist in the UMMC School of Medicine.

References

1. Wood S. TCTMD. 2020 Apr 2. “The mystery of the missing STEMIs during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

2. Stradling R. The News & Observer. 2020 Apr 21. “Fewer people are going to Triangle [N.C.] emergency rooms, and that could be a bad thing.”

3. Kasanagottu K. USA Today. 2020 Apr 15. “Don’t delay care for chronic illness over coronavirus. It’s bad for you and for hospitals.”

4. Snowbeck C. The Star Tribune. 2020 Apr 11. “Mayo Clinic cutting pay for more than 20,000 workers.”

5. LaPointe J. RevCycle Intelligence. 2020 Mar 31. “How much will the COVID-19 pandemic cost hospitals?”

6. Gavidia M. AJMC. 2020 Mar 31. “Sleep, physician burnout linked amid COVID-19 pandemic.”

7. Hollander JE and Carr BG. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1679-81. “Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19.”

Over the last several weeks, hospitals and health systems have focused on the COVID-19 epidemic, preparing and expanding bed capacities for the surge of admissions both in intensive care and medical units. An indirect impact of this has been the reduction in outpatient staffing and resources, with the shifting of staff for inpatient care. Many areas seem to have passed the peak in the number of cases and are now seeing a plateau or downward trend in the admissions to acute care facilities.

During this period, there has been a noticeable downtrend in patients being evaluated in the ED, or admitted for decompensation of chronic conditions like heart failure, COPD and diabetes mellitus, or such acute conditions as stroke and MI. Studies from Italy and Spain, and closer to home from Atlanta and Boston, point to a significant decrease in numbers of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admissions.1 Duke Health saw a decrease in stroke admissions in their hospitals by 34%.2

One could argue that these patients are in fact presenting with COVID-19 or similar symptoms as is evidenced by the studies linking the severity of SARS-Co-V2 infection to chronic conditions like diabetes mellitus and obesity.2 On the other hand, the message of social isolation and avoidance of nonurgent visits could lead to delays in care resulting in patients presenting sicker and in advanced stages.3 Also, this has not been limited to the adult population. For example, reports indicate that visits to WakeMed’s pediatric emergency rooms in Wake County, N.C., were down by 60%.2

We could well be seeing a calm before the storm. While it is anticipated that there may be a second surge of COVID-19 cases, health systems would do well to be prepared for the “third surge,” consisting of patients coming in with chronic medical conditions for which they have been, so far, avoiding follow-up and managing at home, and acute medical conditions with delayed diagnoses. The impact could likely be more in the subset of patients with limited access to health care, including medications and follow-up, resulting in a disproportionate burden on safety-net hospitals.

Compounding this issue would be the economic impact of the current crisis on health systems, their staffing, and resources. Several major organizations have already proposed budget cuts and reduction of the workforce, raising significant concerns about the future of health care workers who put their lives at risk during this pandemic.4 There is no guarantee that the federal funding provided by the stimulus packages will save jobs in the health care industry. This problem needs new leadership thinking, and every organization that puts employees over profits margins will have a long-term impact on communities.

Another area of concern is a shift in resources and workflow from ambulatory to inpatient settings for the COVID-19 pandemic, and the need for revamping the ambulatory services with reshifting the workforce. As COVID-19 cases plateau, the resurgence of non-COVID–related admissions will require additional help in inpatient settings. Prioritizing the ambulatory services based on financial benefits versus patient outcomes is also a major challenge to leadership.5

Lastly, the current health care crisis has led to significant stress, both emotional and physical, among frontline caregivers, increasing the risk of burnout.6 How leadership helps health care workers to cope with these stressors, and the resources they provide, is going to play a key role in long term retention of their talent, and will reflect on the organizational culture. Though it might seem trivial, posttraumatic stress disorder related to this is already obvious, and health care leadership needs to put every effort in providing the resources to help prevent burnout, in partnership with national organizations like the Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians.

The expansion of telemedicine has provided a unique opportunity to address several of these issues while maintaining the nonpharmacologic interventions to fight the epidemic, and keeping the cost curve as low as possible.7 Extension of these services to all ambulatory service lines, including home health and therapy, is the next big step in the new health care era. Virtual check-ins by physicians, advance practice clinicians, and home care nurses could help alleviate the concerns regarding delays in care of patients with chronic conditions, and help identify those at risk. This would also be of help with staffing shortages, and possibly provide much needed support to frontline providers.

Dr. Prasad is currently medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He was previously quality and utilization officer and chief of the medical staff at Aurora Sinai Medical Center. Dr. Prasad is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS Committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin Chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist in the UMMC School of Medicine.

References

1. Wood S. TCTMD. 2020 Apr 2. “The mystery of the missing STEMIs during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

2. Stradling R. The News & Observer. 2020 Apr 21. “Fewer people are going to Triangle [N.C.] emergency rooms, and that could be a bad thing.”

3. Kasanagottu K. USA Today. 2020 Apr 15. “Don’t delay care for chronic illness over coronavirus. It’s bad for you and for hospitals.”

4. Snowbeck C. The Star Tribune. 2020 Apr 11. “Mayo Clinic cutting pay for more than 20,000 workers.”

5. LaPointe J. RevCycle Intelligence. 2020 Mar 31. “How much will the COVID-19 pandemic cost hospitals?”

6. Gavidia M. AJMC. 2020 Mar 31. “Sleep, physician burnout linked amid COVID-19 pandemic.”

7. Hollander JE and Carr BG. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1679-81. “Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19.”

States vary in vulnerability to COVID-19 impact

West Virginia’s large elderly population and high rates of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and COPD make it the most vulnerable state to the coronavirus, according to a new analysis.

Vulnerability to the virus “isn’t just health related, though, as many people are harmed by the economic effects of the pandemic,” personal finance website WalletHub said May 12.

“It’s important for the U.S. to dedicate a large portion of its resources to providing medical support during the coronavirus pandemic, but we should also support people who don’t have adequate housing or enough money to survive the pandemic,” said WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez.

WalletHub graded each state on 28 measures – including share of obese adults, share of homes lacking access to basic hygienic facilities, and biggest increases in unemployment because of COVID-19 – grouped into three dimensions of vulnerability: medical (60% of the total score), housing (15%), and financial (25%).

Using those measures, Louisiana is the most vulnerable state after West Virginia, followed by Mississippi, Arkansas, and Alabama. All 5 states finished in the top 6 for medical vulnerability, and 4 were in the top 10 for financial vulnerability, but only 1 (Arkansas) was in the top 10 for housing vulnerability, WalletHub said.

Among the three vulnerability dimensions, West Virginia was first in medical, Hawaii (33rd overall) was first in housing, and Louisiana was first in financial. Utah is the least vulnerable state, overall, and the least vulnerable states in each dimension are, respectively, Colorado (50th overall), the District of Columbia (29th overall), and Iowa (45th overall), the report showed.

A look at the individual metrics WalletHub used shows some serious disparities:

- New Jersey’s unemployment recipiency rate of 57.2%, the highest in the country, is 6.1 times higher than North Carolina’s 9.3%.

- The highest uninsured rate, 17.4% in Texas, is 6.2 times higher than in Massachusetts, which is the lowest at 2.8%.

- In California, the share of the homeless population that is unsheltered (71.7%) is more than 33 times higher than in North Dakota (2.2%).

“The financial damage caused by COVID-19 is leaving many Americans without the means to pay their bills and purchase necessities. … The U.S. must continue to support its financially vulnerable populations even after the virus has subsided,” Ms. Gonzalez said.

West Virginia’s large elderly population and high rates of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and COPD make it the most vulnerable state to the coronavirus, according to a new analysis.

Vulnerability to the virus “isn’t just health related, though, as many people are harmed by the economic effects of the pandemic,” personal finance website WalletHub said May 12.

“It’s important for the U.S. to dedicate a large portion of its resources to providing medical support during the coronavirus pandemic, but we should also support people who don’t have adequate housing or enough money to survive the pandemic,” said WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez.

WalletHub graded each state on 28 measures – including share of obese adults, share of homes lacking access to basic hygienic facilities, and biggest increases in unemployment because of COVID-19 – grouped into three dimensions of vulnerability: medical (60% of the total score), housing (15%), and financial (25%).

Using those measures, Louisiana is the most vulnerable state after West Virginia, followed by Mississippi, Arkansas, and Alabama. All 5 states finished in the top 6 for medical vulnerability, and 4 were in the top 10 for financial vulnerability, but only 1 (Arkansas) was in the top 10 for housing vulnerability, WalletHub said.

Among the three vulnerability dimensions, West Virginia was first in medical, Hawaii (33rd overall) was first in housing, and Louisiana was first in financial. Utah is the least vulnerable state, overall, and the least vulnerable states in each dimension are, respectively, Colorado (50th overall), the District of Columbia (29th overall), and Iowa (45th overall), the report showed.

A look at the individual metrics WalletHub used shows some serious disparities:

- New Jersey’s unemployment recipiency rate of 57.2%, the highest in the country, is 6.1 times higher than North Carolina’s 9.3%.

- The highest uninsured rate, 17.4% in Texas, is 6.2 times higher than in Massachusetts, which is the lowest at 2.8%.

- In California, the share of the homeless population that is unsheltered (71.7%) is more than 33 times higher than in North Dakota (2.2%).

“The financial damage caused by COVID-19 is leaving many Americans without the means to pay their bills and purchase necessities. … The U.S. must continue to support its financially vulnerable populations even after the virus has subsided,” Ms. Gonzalez said.

West Virginia’s large elderly population and high rates of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and COPD make it the most vulnerable state to the coronavirus, according to a new analysis.

Vulnerability to the virus “isn’t just health related, though, as many people are harmed by the economic effects of the pandemic,” personal finance website WalletHub said May 12.

“It’s important for the U.S. to dedicate a large portion of its resources to providing medical support during the coronavirus pandemic, but we should also support people who don’t have adequate housing or enough money to survive the pandemic,” said WalletHub analyst Jill Gonzalez.

WalletHub graded each state on 28 measures – including share of obese adults, share of homes lacking access to basic hygienic facilities, and biggest increases in unemployment because of COVID-19 – grouped into three dimensions of vulnerability: medical (60% of the total score), housing (15%), and financial (25%).

Using those measures, Louisiana is the most vulnerable state after West Virginia, followed by Mississippi, Arkansas, and Alabama. All 5 states finished in the top 6 for medical vulnerability, and 4 were in the top 10 for financial vulnerability, but only 1 (Arkansas) was in the top 10 for housing vulnerability, WalletHub said.

Among the three vulnerability dimensions, West Virginia was first in medical, Hawaii (33rd overall) was first in housing, and Louisiana was first in financial. Utah is the least vulnerable state, overall, and the least vulnerable states in each dimension are, respectively, Colorado (50th overall), the District of Columbia (29th overall), and Iowa (45th overall), the report showed.

A look at the individual metrics WalletHub used shows some serious disparities:

- New Jersey’s unemployment recipiency rate of 57.2%, the highest in the country, is 6.1 times higher than North Carolina’s 9.3%.

- The highest uninsured rate, 17.4% in Texas, is 6.2 times higher than in Massachusetts, which is the lowest at 2.8%.

- In California, the share of the homeless population that is unsheltered (71.7%) is more than 33 times higher than in North Dakota (2.2%).

“The financial damage caused by COVID-19 is leaving many Americans without the means to pay their bills and purchase necessities. … The U.S. must continue to support its financially vulnerable populations even after the virus has subsided,” Ms. Gonzalez said.

Sleep quality may affect COPD risk in African American smokers

African American smokers who logged more total sleep time and greater sleep efficacy performed better on a functional walk test than did those with poorer sleep, based on data from 209 adults.

African American smokers tend to develop COPD sooner and also report more sleep problems, compared with white smokers, wrote Andrew J. Gangemi, MD, of Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

In addition, African Americans tend to develop COPD at a younger age and with lower levels of smoking than do non-Hispanic whites, they said. “Sleep health may be a contributing factor to the lung and cardiovascular health disparity experienced by AA smokers,” in part because data suggest that insufficient sleep may be associated with increased risk of COPD exacerbation in smokers in general, they said.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 209 African American adults aged 40-65 years who had smoked at least one cigarette in the past month. The average age of the participants was 55 years, 59% were women, and the average smoking habit was nine cigarettes per day.

The researchers measured functional exercise capacity of the participants using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Total sleep time (TST) and sleep efficacy (SE) were measured by way of a finger-based device.

Smokers of at least 10 cigarettes per day gained an additional 0.05-0.58 meters in distance covered on the 6MWT for every added minute of total sleep time in a multivariable regression analysis. Similarly, smokers of at least 10 cigarettes per day gained an additional 0.84-6.17–meter increase in distance covered on the 6MWT for every added percentage of sleep efficacy.

The reasons for the impact of SE and TST on functional exercise capacity in smokers remain unclear, the researchers said. “Heavier smokers have higher levels of autonomic imbalance, including higher resting heart rate and heart rate variability, impaired 24-hour cardiovascular sympathetic tone, and blunted cerebrovascular autonomic regulation and baroreflex response to hypercapnia,” they said.

Also unclear is the reason for the large magnitude of the association between SE and smoking vs. the lesser association between TST and smoking on 6MWT results, the researchers wrote. “Poor sleep efficiency, outside of traditional OSA scoring, is predictive of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular-related mortality risk. Moreover, deficits in sleep efficiency have been consistently demonstrated in smokers versus nonsmokers,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including inability to extrapolate data to other demographic groups and the cross-sectional design, the researchers noted. In addition, they did not address how TST and SE may relate to lung function.

However, the results “extend current knowledge about the potential role of improved sleep health to functional exercise capacity in AA smokers,” and set the stage for future studies of how changes in sleep health may affect lung and functional exercise capacity in smokers over time, as well as effects on inflammation and autonomic imbalance, the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, both part of the National Institutes Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Gangemi A et al. Chest 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.070.

African American smokers who logged more total sleep time and greater sleep efficacy performed better on a functional walk test than did those with poorer sleep, based on data from 209 adults.

African American smokers tend to develop COPD sooner and also report more sleep problems, compared with white smokers, wrote Andrew J. Gangemi, MD, of Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, and colleagues.