User login

Pharmacogenomic testing may curb drug interactions in severe depression

Pharmacogenetic testing, which is used to classify how patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) metabolize medications, reduces adverse drug-gene interactions, new research shows.

In addition, among the intervention group, the rate of remission over 24 weeks was significantly greater.

“These tests can be helpful in rethinking choices of antidepressants, but clinicians should not expect them to be helpful for every patient,” study investigator David W. Oslin, MD, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and professor of psychiatry at Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA.

Less trial and error

Pharmacogenomic testing can provide information to inform drug selection or dosing for patients with a genetic variation that alters pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. Such testing may be particularly useful for patients with MDD, as fewer than 40% of these patients achieve clinical remission after an initial treatment with an antidepressant, the investigators note.

“To get to a treatment that works for an individual, it’s not unusual to have to try two or three or four antidepressants,” said Dr. Oslin. “If we could reduce that variance a little bit with a test like this, that would be huge from a public health perspective.”

The study included 676 physicians and 1,944 adults with MDD (mean age, 48 years; 24% women) who were receiving care at 22 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Eligible patients were set to start a new antidepressant monotherapy, and all underwent a pharmacogenomic test using a cheek swab.

Investigators randomly assigned patients to receive test results when available (pharmacogenomic-guided group) or 24 weeks later (usual-care group). For the former group, clinicians were asked to initiate treatment when test results were available, typically within 2-3 days. For the latter group, they were asked to initiate treatment on a day of randomization.

Assessments included the 9-item Patient Health questionnaire (PHQ-9), scores for which range from 0-27 points, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

Of the total patient population, 79% completed the 24-week assessment.

Researchers characterized antidepressant medications on the basis of drug-gene interaction categories: no known interactions, moderate interactions, and substantial interactions.

The co-primary outcomes were treatment initiation within 30 days, determined on the basis of drug-gene interaction categories, and remission from depression symptoms, defined as a PHQ-9 score of less than or equal to 5.

Raters who were blinded to clinical care and study randomization assessed outcomes at 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 weeks.

Significant impact?

Results showed that the pharmacogenomic-guided group was more likely to receive an antidepressant that had no potential drug-gene interaction, as opposed to one with a moderate/substantial interaction (odds ratio, 4.32; 95% confidence interval, 3.47-5.39; P < .001).

The usual-care group was more likely to receive a drug with mild potential drug-gene interaction (no/moderate interaction vs. substantial interaction: OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.52-2.84; P = .005).

For the intervention group, the estimated rates of receiving an antidepressant with no, moderate, and substantial drug-gene interactions were 59.3%, 30.0%, and 10.7%, respectively. For the usual-care group, the estimates were 25.7%, 54.6%, and 19.7%.

The finding that 1 in 5 patients who received usual care were initially given a medication for which there were significant drug-gene interactions means it is “not a rare event,” said Dr. Oslin. “If we can make an impact on 20% of the people we prescribe to, that’s actually pretty big.”

Rates of remission were greater in the pharmacogenomic-guided group over 24 weeks (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.05-1.57; P = .02; absolute risk difference, 2.8%; 95% CI, 0.6%-5.1%).

The secondary outcomes of response to treatment, defined as at least a 50% decrease in PHQ-9 score, also favored the pharmacogenomic-guided group. This was also the case for the secondary outcome of reduction in symptom severity on the PHQ-9 score.

Some physicians have expressed skepticism about pharmacogenomic testing, but the study provides additional evidence of its usefulness, Dr. Oslin noted.

“While I don’t think testing should be standard of practice, I also don’t think we should put barriers into the testing until we can better understand how to target the testing” to those who will benefit the most, he added.

The tests are available at a commercial cost of about $1,000 – which may not be that expensive if testing has a significant impact on a patient’s life, said Dr. Oslin.

Important research, but with several limitations

In an accompanying editorial, Dan V. Iosifescu, MD, associate professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine and director of clinical research at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, called the study an important addition to the literature on pharmacogenomic testing for patients with MDD.

The study was significantly larger and had broader inclusion criteria and longer follow-up than previous clinical trials and is one of the few investigations not funded by a manufacturer of pharmacogenomic tests, writes Dr. Iosifescu, who was not involved with the research.

However, he notes that an antidepressant was not initiated for 30 days after randomization in 25% of the intervention group and in 31% of the usual-care group, which was “puzzling.” “Because these rates were comparable in the 2 groups, it cannot be explained primarily by the delay of the pharmacogenomic test results in the intervention group,” he writes.

In addition, in the co-primary outcome of symptom remission rate, the difference in clinical improvement in favor of the pharmacogenomic-guided treatment was only “modest” – the gain was of less than 2% in the proportion of patients achieving remission, Dr. Iosifescu adds.

He adds this is “likely not very meaningful clinically despite this difference achieving statistical significance in this large study sample.”

Other potential study limitations he cites include the lack of patient blinding to treatment assignment and the absence of clarity about why rates of MDD response and remission over time were relatively low in both treatment groups.

A possible approach to optimize antidepressant choices could involve integration of pharmacogenomic data into larger predictive models that include clinical and demographic variables, Dr. Iosifescu notes.

“The development of such complex models is challenging, but it is now possible given the recent substantial advances in the proficiency of computational tools,” he writes.

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Health Services Research and Development Service, and the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center. Dr. Oslin reports having received grants from the VA Office of Research and Development and Janssen Pharmaceuticals and nonfinancial support from Myriad Genetics during the conduct of the study. Dr. Iosifescu report having received personal fees from Alkermes, Allergan, Axsome, Biogen, the Centers for Psychiatric Excellence, Jazz, Lundbeck, Precision Neuroscience, Sage, and Sunovion and grants from Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Brainsway, Litecure, Neosync, Otsuka, Roche, and Shire.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pharmacogenetic testing, which is used to classify how patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) metabolize medications, reduces adverse drug-gene interactions, new research shows.

In addition, among the intervention group, the rate of remission over 24 weeks was significantly greater.

“These tests can be helpful in rethinking choices of antidepressants, but clinicians should not expect them to be helpful for every patient,” study investigator David W. Oslin, MD, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and professor of psychiatry at Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA.

Less trial and error

Pharmacogenomic testing can provide information to inform drug selection or dosing for patients with a genetic variation that alters pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. Such testing may be particularly useful for patients with MDD, as fewer than 40% of these patients achieve clinical remission after an initial treatment with an antidepressant, the investigators note.

“To get to a treatment that works for an individual, it’s not unusual to have to try two or three or four antidepressants,” said Dr. Oslin. “If we could reduce that variance a little bit with a test like this, that would be huge from a public health perspective.”

The study included 676 physicians and 1,944 adults with MDD (mean age, 48 years; 24% women) who were receiving care at 22 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Eligible patients were set to start a new antidepressant monotherapy, and all underwent a pharmacogenomic test using a cheek swab.

Investigators randomly assigned patients to receive test results when available (pharmacogenomic-guided group) or 24 weeks later (usual-care group). For the former group, clinicians were asked to initiate treatment when test results were available, typically within 2-3 days. For the latter group, they were asked to initiate treatment on a day of randomization.

Assessments included the 9-item Patient Health questionnaire (PHQ-9), scores for which range from 0-27 points, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

Of the total patient population, 79% completed the 24-week assessment.

Researchers characterized antidepressant medications on the basis of drug-gene interaction categories: no known interactions, moderate interactions, and substantial interactions.

The co-primary outcomes were treatment initiation within 30 days, determined on the basis of drug-gene interaction categories, and remission from depression symptoms, defined as a PHQ-9 score of less than or equal to 5.

Raters who were blinded to clinical care and study randomization assessed outcomes at 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 weeks.

Significant impact?

Results showed that the pharmacogenomic-guided group was more likely to receive an antidepressant that had no potential drug-gene interaction, as opposed to one with a moderate/substantial interaction (odds ratio, 4.32; 95% confidence interval, 3.47-5.39; P < .001).

The usual-care group was more likely to receive a drug with mild potential drug-gene interaction (no/moderate interaction vs. substantial interaction: OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.52-2.84; P = .005).

For the intervention group, the estimated rates of receiving an antidepressant with no, moderate, and substantial drug-gene interactions were 59.3%, 30.0%, and 10.7%, respectively. For the usual-care group, the estimates were 25.7%, 54.6%, and 19.7%.

The finding that 1 in 5 patients who received usual care were initially given a medication for which there were significant drug-gene interactions means it is “not a rare event,” said Dr. Oslin. “If we can make an impact on 20% of the people we prescribe to, that’s actually pretty big.”

Rates of remission were greater in the pharmacogenomic-guided group over 24 weeks (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.05-1.57; P = .02; absolute risk difference, 2.8%; 95% CI, 0.6%-5.1%).

The secondary outcomes of response to treatment, defined as at least a 50% decrease in PHQ-9 score, also favored the pharmacogenomic-guided group. This was also the case for the secondary outcome of reduction in symptom severity on the PHQ-9 score.

Some physicians have expressed skepticism about pharmacogenomic testing, but the study provides additional evidence of its usefulness, Dr. Oslin noted.

“While I don’t think testing should be standard of practice, I also don’t think we should put barriers into the testing until we can better understand how to target the testing” to those who will benefit the most, he added.

The tests are available at a commercial cost of about $1,000 – which may not be that expensive if testing has a significant impact on a patient’s life, said Dr. Oslin.

Important research, but with several limitations

In an accompanying editorial, Dan V. Iosifescu, MD, associate professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine and director of clinical research at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, called the study an important addition to the literature on pharmacogenomic testing for patients with MDD.

The study was significantly larger and had broader inclusion criteria and longer follow-up than previous clinical trials and is one of the few investigations not funded by a manufacturer of pharmacogenomic tests, writes Dr. Iosifescu, who was not involved with the research.

However, he notes that an antidepressant was not initiated for 30 days after randomization in 25% of the intervention group and in 31% of the usual-care group, which was “puzzling.” “Because these rates were comparable in the 2 groups, it cannot be explained primarily by the delay of the pharmacogenomic test results in the intervention group,” he writes.

In addition, in the co-primary outcome of symptom remission rate, the difference in clinical improvement in favor of the pharmacogenomic-guided treatment was only “modest” – the gain was of less than 2% in the proportion of patients achieving remission, Dr. Iosifescu adds.

He adds this is “likely not very meaningful clinically despite this difference achieving statistical significance in this large study sample.”

Other potential study limitations he cites include the lack of patient blinding to treatment assignment and the absence of clarity about why rates of MDD response and remission over time were relatively low in both treatment groups.

A possible approach to optimize antidepressant choices could involve integration of pharmacogenomic data into larger predictive models that include clinical and demographic variables, Dr. Iosifescu notes.

“The development of such complex models is challenging, but it is now possible given the recent substantial advances in the proficiency of computational tools,” he writes.

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Health Services Research and Development Service, and the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center. Dr. Oslin reports having received grants from the VA Office of Research and Development and Janssen Pharmaceuticals and nonfinancial support from Myriad Genetics during the conduct of the study. Dr. Iosifescu report having received personal fees from Alkermes, Allergan, Axsome, Biogen, the Centers for Psychiatric Excellence, Jazz, Lundbeck, Precision Neuroscience, Sage, and Sunovion and grants from Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Brainsway, Litecure, Neosync, Otsuka, Roche, and Shire.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pharmacogenetic testing, which is used to classify how patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) metabolize medications, reduces adverse drug-gene interactions, new research shows.

In addition, among the intervention group, the rate of remission over 24 weeks was significantly greater.

“These tests can be helpful in rethinking choices of antidepressants, but clinicians should not expect them to be helpful for every patient,” study investigator David W. Oslin, MD, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and professor of psychiatry at Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA.

Less trial and error

Pharmacogenomic testing can provide information to inform drug selection or dosing for patients with a genetic variation that alters pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. Such testing may be particularly useful for patients with MDD, as fewer than 40% of these patients achieve clinical remission after an initial treatment with an antidepressant, the investigators note.

“To get to a treatment that works for an individual, it’s not unusual to have to try two or three or four antidepressants,” said Dr. Oslin. “If we could reduce that variance a little bit with a test like this, that would be huge from a public health perspective.”

The study included 676 physicians and 1,944 adults with MDD (mean age, 48 years; 24% women) who were receiving care at 22 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Eligible patients were set to start a new antidepressant monotherapy, and all underwent a pharmacogenomic test using a cheek swab.

Investigators randomly assigned patients to receive test results when available (pharmacogenomic-guided group) or 24 weeks later (usual-care group). For the former group, clinicians were asked to initiate treatment when test results were available, typically within 2-3 days. For the latter group, they were asked to initiate treatment on a day of randomization.

Assessments included the 9-item Patient Health questionnaire (PHQ-9), scores for which range from 0-27 points, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

Of the total patient population, 79% completed the 24-week assessment.

Researchers characterized antidepressant medications on the basis of drug-gene interaction categories: no known interactions, moderate interactions, and substantial interactions.

The co-primary outcomes were treatment initiation within 30 days, determined on the basis of drug-gene interaction categories, and remission from depression symptoms, defined as a PHQ-9 score of less than or equal to 5.

Raters who were blinded to clinical care and study randomization assessed outcomes at 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 weeks.

Significant impact?

Results showed that the pharmacogenomic-guided group was more likely to receive an antidepressant that had no potential drug-gene interaction, as opposed to one with a moderate/substantial interaction (odds ratio, 4.32; 95% confidence interval, 3.47-5.39; P < .001).

The usual-care group was more likely to receive a drug with mild potential drug-gene interaction (no/moderate interaction vs. substantial interaction: OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.52-2.84; P = .005).

For the intervention group, the estimated rates of receiving an antidepressant with no, moderate, and substantial drug-gene interactions were 59.3%, 30.0%, and 10.7%, respectively. For the usual-care group, the estimates were 25.7%, 54.6%, and 19.7%.

The finding that 1 in 5 patients who received usual care were initially given a medication for which there were significant drug-gene interactions means it is “not a rare event,” said Dr. Oslin. “If we can make an impact on 20% of the people we prescribe to, that’s actually pretty big.”

Rates of remission were greater in the pharmacogenomic-guided group over 24 weeks (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.05-1.57; P = .02; absolute risk difference, 2.8%; 95% CI, 0.6%-5.1%).

The secondary outcomes of response to treatment, defined as at least a 50% decrease in PHQ-9 score, also favored the pharmacogenomic-guided group. This was also the case for the secondary outcome of reduction in symptom severity on the PHQ-9 score.

Some physicians have expressed skepticism about pharmacogenomic testing, but the study provides additional evidence of its usefulness, Dr. Oslin noted.

“While I don’t think testing should be standard of practice, I also don’t think we should put barriers into the testing until we can better understand how to target the testing” to those who will benefit the most, he added.

The tests are available at a commercial cost of about $1,000 – which may not be that expensive if testing has a significant impact on a patient’s life, said Dr. Oslin.

Important research, but with several limitations

In an accompanying editorial, Dan V. Iosifescu, MD, associate professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine and director of clinical research at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, called the study an important addition to the literature on pharmacogenomic testing for patients with MDD.

The study was significantly larger and had broader inclusion criteria and longer follow-up than previous clinical trials and is one of the few investigations not funded by a manufacturer of pharmacogenomic tests, writes Dr. Iosifescu, who was not involved with the research.

However, he notes that an antidepressant was not initiated for 30 days after randomization in 25% of the intervention group and in 31% of the usual-care group, which was “puzzling.” “Because these rates were comparable in the 2 groups, it cannot be explained primarily by the delay of the pharmacogenomic test results in the intervention group,” he writes.

In addition, in the co-primary outcome of symptom remission rate, the difference in clinical improvement in favor of the pharmacogenomic-guided treatment was only “modest” – the gain was of less than 2% in the proportion of patients achieving remission, Dr. Iosifescu adds.

He adds this is “likely not very meaningful clinically despite this difference achieving statistical significance in this large study sample.”

Other potential study limitations he cites include the lack of patient blinding to treatment assignment and the absence of clarity about why rates of MDD response and remission over time were relatively low in both treatment groups.

A possible approach to optimize antidepressant choices could involve integration of pharmacogenomic data into larger predictive models that include clinical and demographic variables, Dr. Iosifescu notes.

“The development of such complex models is challenging, but it is now possible given the recent substantial advances in the proficiency of computational tools,” he writes.

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Health Services Research and Development Service, and the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center. Dr. Oslin reports having received grants from the VA Office of Research and Development and Janssen Pharmaceuticals and nonfinancial support from Myriad Genetics during the conduct of the study. Dr. Iosifescu report having received personal fees from Alkermes, Allergan, Axsome, Biogen, the Centers for Psychiatric Excellence, Jazz, Lundbeck, Precision Neuroscience, Sage, and Sunovion and grants from Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Brainsway, Litecure, Neosync, Otsuka, Roche, and Shire.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

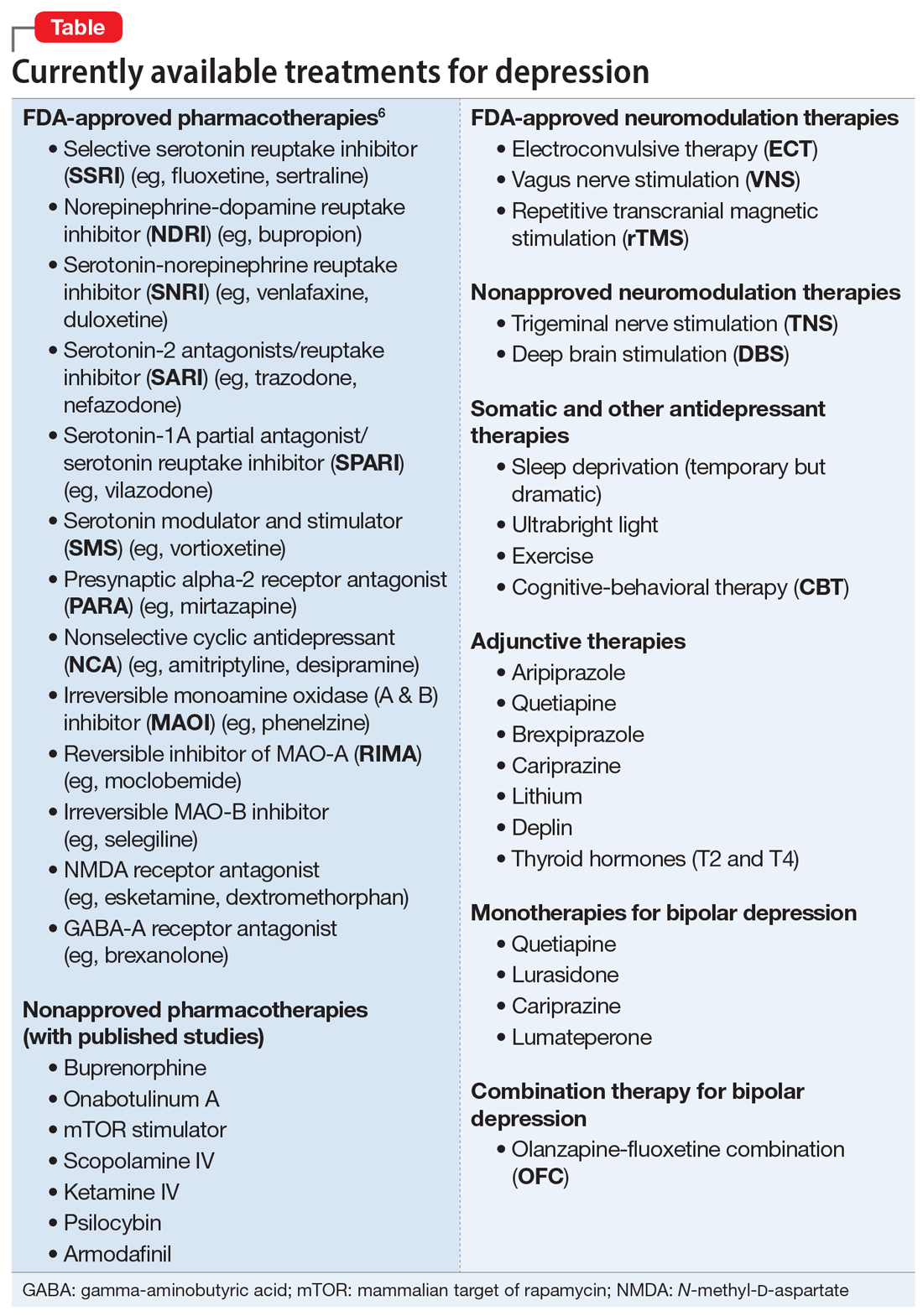

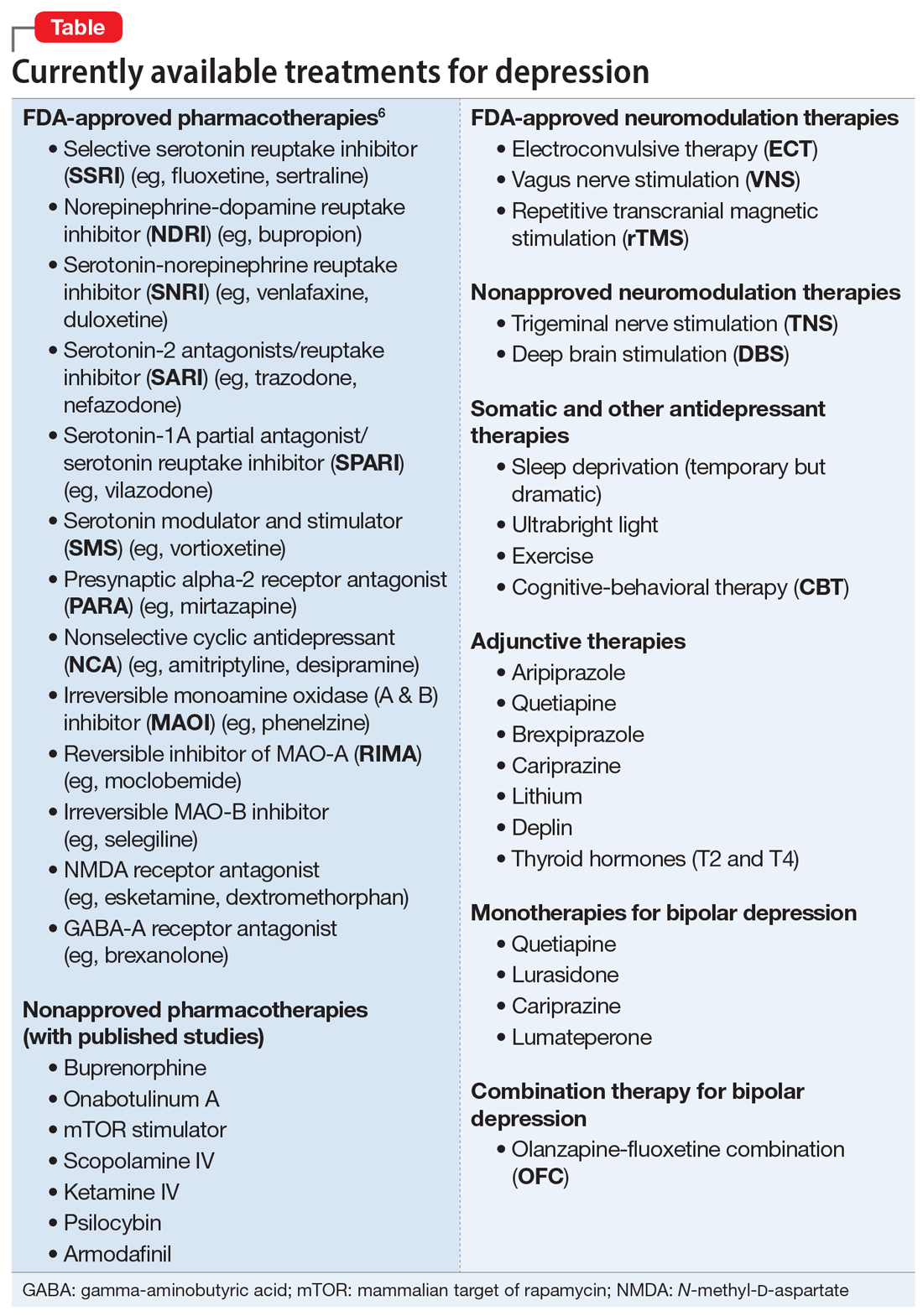

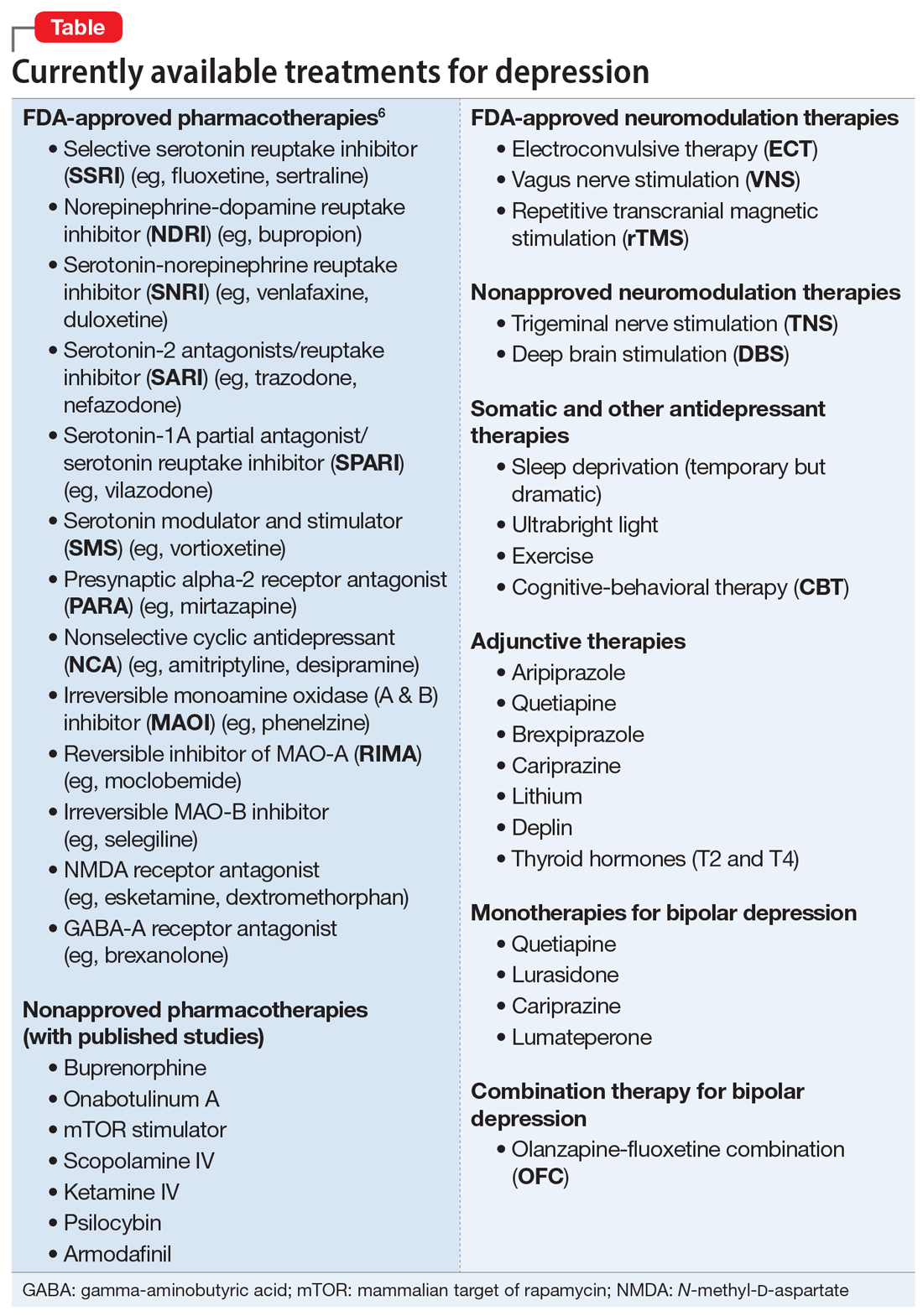

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

High rate of mental health problems in transgender children

Transgender children, even those as young as 9 or 10 years old, already show increased susceptibility to mental health problems compared with their cisgender peers, new research suggests.

Investigators assessed a sample of more than 7000 children aged 9-10 years in the general population and found those who reported being transgender scored considerably higher on all six subscales of the DSM-5-oriented Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Transgender children had almost sixfold higher odds of suicidality and over twice the odds of depressive and anxiety problems, compared with cisgender children. Moreover, transgender children displayed higher levels of mental health problems compared with previous studies of transgender children recruited from specialist gender clinics.

“Our findings emphasize the vulnerability of transgender children, including those who may not yet have accessed specialist support,” senior author Kenneth C. Pang, MBBS, BMedSc, PhD, associate professor, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, University of Melbourne, Royal Children’s Hospital, Australia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians providing general health care to transgender children should keep this vulnerability in mind and proactively address any mental health problems that exist,” he said.

The findings were published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

Higher levels of support?

“We felt this study was important to conduct because previous studies regarding the mental health of transgender children have been drawn from children receiving specialist gender-related care,” Dr. Pang said.

“Transgender children receiving such care are likely to enjoy higher levels of support than those unable to access such services, and this might create differences in mental health,” he added.

To investigate this issue, the researchers turned to participants (n = 7,169; mean age, 10.3 years) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study.

“The ABCD study is a longitudinal study of over 11,000 children who were recruited to reflect the sociodemographic variation of the U.S. population,” lead author Douglas H. Russell, MSc, a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, told this news organization.

To be included in the current study, children had to understand and respond to the question “Are you transgender?”

The researchers compared mental health outcomes between transgender and cisgender children (n = 58 and n = 7,111, respectively) using the CBCL, which study participants had completed at baseline.

Key protective factor

The transgender children recorded higher mean T scores for all six subscales of the CBCL, although all children scored in the references range; and the standardized mean difference was “small.”

Suicidality was measured by summing the two suicide-related items in the parent-report CBCL assessing suicidal ideation and attempts.

“For the CBCL, T scores are calculated for measures that are scored on a continuous scale,” Dr. Pang noted. “Responses to the suicidality questions on the CBCL were assessed in a categorical manner (at risk of suicide vs. not), as previously described by others. So T scores were therefore not able to be calculated.”

When the investigators determined the proportion of cisgender and transgender children who scored in the “borderline” or “clinical” range (T score, 65), they found increased odds of transgender children scoring in that range in all six subscales, as well as suicidality.

The researchers note the results for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant problems were not statistically significant.

Previous studies that used clinical samples of young transgender children (aged 5 -11 years) reported lower rates of depression and anxiety than what was found in the current study.

“Transgender children in the general population displayed higher levels of mental health problems compared to previous studies of transgender children recruited from specialist gender clinics,” Mr. Russell said.

One reason for that may be children in specialist clinics “are likely to have support from their families (a key protective factor for the mental health of transgender young people); in comparison, many transgender children in the general population lack parental support for their gender,” the investigators wrote.

“Our findings suggest that by 9 to 10 years of age transgender children already show increased susceptibility to mental health problems compared with their cisgender peers, which has important public health implications,” they added.

The researchers noted that whether this susceptibility “is due to stigma, minority stress, discrimination, or gender dysphoria is unclear, but providing appropriate mental health supports to this vulnerable group is paramount.”

“Pathologizing and damaging”

Commenting for this news organiztion, Jack L. Turban, MD, incoming assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, said that “sadly” the findings are “largely in line with past studies that have shown dramatic mental health disparities” for transgender and gender diverse youth.

“The dramatically elevated odds of suicidality warrants particular public health concern,” said Dr. Turban, who was not involved with the study.

He noted these results “come at a time when transgender youth are under legislative attack in many states throughout the country, and the national rhetoric around them has been pathologizing and damaging.”

Dr. Turban said that he worries “if our national discourse around trans youth doesn’t change soon, that these disparities will worsen.”

Funding was provided to individual investigators by the Hugh Williamson Foundation, the Royal Children’s Hospital foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Mr. Russell and Dr. Pang reported being members of the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health. Dr. Pang is a member of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and a member of the editorial board of the journal Transgender Health. Dr. Turban reported textbook royalties from Springer Nature, being on the scientific advisory board of Panorama Global (UpSwing Fund), and payments as an expert witness for the American Civil Liberties Union, Lambda Legal, and Cooley LLP. He has received a pilot research award from AACAP and pharmaceutical partners (Arbor and Pfizer), a research fellowship from the Sorensen Foundation, and freelance payments from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender children, even those as young as 9 or 10 years old, already show increased susceptibility to mental health problems compared with their cisgender peers, new research suggests.

Investigators assessed a sample of more than 7000 children aged 9-10 years in the general population and found those who reported being transgender scored considerably higher on all six subscales of the DSM-5-oriented Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Transgender children had almost sixfold higher odds of suicidality and over twice the odds of depressive and anxiety problems, compared with cisgender children. Moreover, transgender children displayed higher levels of mental health problems compared with previous studies of transgender children recruited from specialist gender clinics.

“Our findings emphasize the vulnerability of transgender children, including those who may not yet have accessed specialist support,” senior author Kenneth C. Pang, MBBS, BMedSc, PhD, associate professor, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, University of Melbourne, Royal Children’s Hospital, Australia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians providing general health care to transgender children should keep this vulnerability in mind and proactively address any mental health problems that exist,” he said.

The findings were published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

Higher levels of support?

“We felt this study was important to conduct because previous studies regarding the mental health of transgender children have been drawn from children receiving specialist gender-related care,” Dr. Pang said.

“Transgender children receiving such care are likely to enjoy higher levels of support than those unable to access such services, and this might create differences in mental health,” he added.

To investigate this issue, the researchers turned to participants (n = 7,169; mean age, 10.3 years) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study.

“The ABCD study is a longitudinal study of over 11,000 children who were recruited to reflect the sociodemographic variation of the U.S. population,” lead author Douglas H. Russell, MSc, a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, told this news organization.

To be included in the current study, children had to understand and respond to the question “Are you transgender?”

The researchers compared mental health outcomes between transgender and cisgender children (n = 58 and n = 7,111, respectively) using the CBCL, which study participants had completed at baseline.

Key protective factor

The transgender children recorded higher mean T scores for all six subscales of the CBCL, although all children scored in the references range; and the standardized mean difference was “small.”

Suicidality was measured by summing the two suicide-related items in the parent-report CBCL assessing suicidal ideation and attempts.

“For the CBCL, T scores are calculated for measures that are scored on a continuous scale,” Dr. Pang noted. “Responses to the suicidality questions on the CBCL were assessed in a categorical manner (at risk of suicide vs. not), as previously described by others. So T scores were therefore not able to be calculated.”

When the investigators determined the proportion of cisgender and transgender children who scored in the “borderline” or “clinical” range (T score, 65), they found increased odds of transgender children scoring in that range in all six subscales, as well as suicidality.

The researchers note the results for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant problems were not statistically significant.

Previous studies that used clinical samples of young transgender children (aged 5 -11 years) reported lower rates of depression and anxiety than what was found in the current study.

“Transgender children in the general population displayed higher levels of mental health problems compared to previous studies of transgender children recruited from specialist gender clinics,” Mr. Russell said.

One reason for that may be children in specialist clinics “are likely to have support from their families (a key protective factor for the mental health of transgender young people); in comparison, many transgender children in the general population lack parental support for their gender,” the investigators wrote.

“Our findings suggest that by 9 to 10 years of age transgender children already show increased susceptibility to mental health problems compared with their cisgender peers, which has important public health implications,” they added.

The researchers noted that whether this susceptibility “is due to stigma, minority stress, discrimination, or gender dysphoria is unclear, but providing appropriate mental health supports to this vulnerable group is paramount.”

“Pathologizing and damaging”

Commenting for this news organiztion, Jack L. Turban, MD, incoming assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, said that “sadly” the findings are “largely in line with past studies that have shown dramatic mental health disparities” for transgender and gender diverse youth.

“The dramatically elevated odds of suicidality warrants particular public health concern,” said Dr. Turban, who was not involved with the study.

He noted these results “come at a time when transgender youth are under legislative attack in many states throughout the country, and the national rhetoric around them has been pathologizing and damaging.”

Dr. Turban said that he worries “if our national discourse around trans youth doesn’t change soon, that these disparities will worsen.”

Funding was provided to individual investigators by the Hugh Williamson Foundation, the Royal Children’s Hospital foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Mr. Russell and Dr. Pang reported being members of the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health. Dr. Pang is a member of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and a member of the editorial board of the journal Transgender Health. Dr. Turban reported textbook royalties from Springer Nature, being on the scientific advisory board of Panorama Global (UpSwing Fund), and payments as an expert witness for the American Civil Liberties Union, Lambda Legal, and Cooley LLP. He has received a pilot research award from AACAP and pharmaceutical partners (Arbor and Pfizer), a research fellowship from the Sorensen Foundation, and freelance payments from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender children, even those as young as 9 or 10 years old, already show increased susceptibility to mental health problems compared with their cisgender peers, new research suggests.

Investigators assessed a sample of more than 7000 children aged 9-10 years in the general population and found those who reported being transgender scored considerably higher on all six subscales of the DSM-5-oriented Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Transgender children had almost sixfold higher odds of suicidality and over twice the odds of depressive and anxiety problems, compared with cisgender children. Moreover, transgender children displayed higher levels of mental health problems compared with previous studies of transgender children recruited from specialist gender clinics.

“Our findings emphasize the vulnerability of transgender children, including those who may not yet have accessed specialist support,” senior author Kenneth C. Pang, MBBS, BMedSc, PhD, associate professor, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, University of Melbourne, Royal Children’s Hospital, Australia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians providing general health care to transgender children should keep this vulnerability in mind and proactively address any mental health problems that exist,” he said.

The findings were published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

Higher levels of support?

“We felt this study was important to conduct because previous studies regarding the mental health of transgender children have been drawn from children receiving specialist gender-related care,” Dr. Pang said.

“Transgender children receiving such care are likely to enjoy higher levels of support than those unable to access such services, and this might create differences in mental health,” he added.

To investigate this issue, the researchers turned to participants (n = 7,169; mean age, 10.3 years) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study.

“The ABCD study is a longitudinal study of over 11,000 children who were recruited to reflect the sociodemographic variation of the U.S. population,” lead author Douglas H. Russell, MSc, a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, told this news organization.

To be included in the current study, children had to understand and respond to the question “Are you transgender?”

The researchers compared mental health outcomes between transgender and cisgender children (n = 58 and n = 7,111, respectively) using the CBCL, which study participants had completed at baseline.

Key protective factor

The transgender children recorded higher mean T scores for all six subscales of the CBCL, although all children scored in the references range; and the standardized mean difference was “small.”

Suicidality was measured by summing the two suicide-related items in the parent-report CBCL assessing suicidal ideation and attempts.

“For the CBCL, T scores are calculated for measures that are scored on a continuous scale,” Dr. Pang noted. “Responses to the suicidality questions on the CBCL were assessed in a categorical manner (at risk of suicide vs. not), as previously described by others. So T scores were therefore not able to be calculated.”

When the investigators determined the proportion of cisgender and transgender children who scored in the “borderline” or “clinical” range (T score, 65), they found increased odds of transgender children scoring in that range in all six subscales, as well as suicidality.

The researchers note the results for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant problems were not statistically significant.

Previous studies that used clinical samples of young transgender children (aged 5 -11 years) reported lower rates of depression and anxiety than what was found in the current study.

“Transgender children in the general population displayed higher levels of mental health problems compared to previous studies of transgender children recruited from specialist gender clinics,” Mr. Russell said.

One reason for that may be children in specialist clinics “are likely to have support from their families (a key protective factor for the mental health of transgender young people); in comparison, many transgender children in the general population lack parental support for their gender,” the investigators wrote.

“Our findings suggest that by 9 to 10 years of age transgender children already show increased susceptibility to mental health problems compared with their cisgender peers, which has important public health implications,” they added.

The researchers noted that whether this susceptibility “is due to stigma, minority stress, discrimination, or gender dysphoria is unclear, but providing appropriate mental health supports to this vulnerable group is paramount.”

“Pathologizing and damaging”

Commenting for this news organiztion, Jack L. Turban, MD, incoming assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, said that “sadly” the findings are “largely in line with past studies that have shown dramatic mental health disparities” for transgender and gender diverse youth.

“The dramatically elevated odds of suicidality warrants particular public health concern,” said Dr. Turban, who was not involved with the study.

He noted these results “come at a time when transgender youth are under legislative attack in many states throughout the country, and the national rhetoric around them has been pathologizing and damaging.”

Dr. Turban said that he worries “if our national discourse around trans youth doesn’t change soon, that these disparities will worsen.”

Funding was provided to individual investigators by the Hugh Williamson Foundation, the Royal Children’s Hospital foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Mr. Russell and Dr. Pang reported being members of the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health. Dr. Pang is a member of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and a member of the editorial board of the journal Transgender Health. Dr. Turban reported textbook royalties from Springer Nature, being on the scientific advisory board of Panorama Global (UpSwing Fund), and payments as an expert witness for the American Civil Liberties Union, Lambda Legal, and Cooley LLP. He has received a pilot research award from AACAP and pharmaceutical partners (Arbor and Pfizer), a research fellowship from the Sorensen Foundation, and freelance payments from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Guideline advises against depression screening in pregnancy

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommends against the routine screening of all pregnant and postpartum women for depression using a standard questionnaire, according to its new guideline.

The basis for its position is the lack of evidence that such screening “adds value beyond discussions about overall wellbeing, depression, anxiety, and mood that are currently a part of established perinatal clinical care.

“We should not be using a one-size-fits all approach,” lead author Eddy Lang, MD, professor and head of emergency medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary (Alta.), told this news organization.

Instead, the task force emphasizes regular clinical care, including asking patients about their wellbeing and support systems. The task force categorizes the recommendation as conditional and as having very low-certainty evidence.

The recommendation was published in CMAJ.

One randomized study

The task force is an independent panel of clinicians and scientists that makes recommendations on primary and secondary prevention in primary care. A working group of five members of the task force developed this recommendation with scientific support from Public Health Agency of Canada staff.

In its research, the task force found only one study that showed a benefit of routine depression screening in this population. This study was a randomized controlled trial conducted in Hong Kong. Researchers evaluated 462 postpartum women who were randomly assigned to receive screening with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or no screening 2 months post partum.

“We found the effect of screening in this study to be very uncertain for the important outcomes of interest,” said Dr. Lang.

“These included parent-child stress, marital stress, and the number of infant hospital admissions. The effects of screening on all of these outcomes were very uncertain, mainly because it was such a small trial,” he said.

The task force also assessed how pregnant and postpartum women feel about being screened. What these women most wanted was a good relationship with a trusted primary care provider who would initiate discussions about their mental health in a caring atmosphere.

“Although they told us they liked the idea of universal screening, they admitted to their family doctors that they actually preferred to be asked about their wellbeing, [to be asked] how things were going at home, and [to have] a discussion about their mental health and wellbeing, rather than a formal screening process. They felt a discussion about depression with a primary health care provider during the pregnancy and postpartum period is critical,” said Dr. Lang.

Thus, the task force recommends “against instrument-based depression screening using a questionnaire with cutoff score to distinguish ‘screen positive’ and ‘screen negative’ administered to all individuals during pregnancy and the postpartum period (up to 1 year after childbirth).”

Screening remains common

“There’s a lot of uncertainty in the scientific community about whether it’s a good idea to administer a screening test to all pregnant and postpartum women to determine in a systematic way if they might be suffering from depression,” said Dr. Lang.

The task force recommended against screening for depression among perinatal or postpartum women in 2013, but screening is still performed in many provinces, said Dr. Lang.

Dr. Lang emphasized that the recommendation does not apply to usual care, in which the provider asks questions about and discusses a patient’s mental health and proceeds on the basis of their clinical judgment; nor does it apply to diagnostic pathways in which the clinician suspects that the individual may have depression and tests her accordingly.

“What we are saying in our recommendation is that all clinicians should ask about a patient’s wellbeing, about their mood, their anxiety, and these questions are an important part of the clinical assessment of pregnant and postpartum women. But we’re also saying the usefulness of doing so with a questionnaire and using a cutoff score on the questionnaire to decide who needs further assessment or possibly treatment is unproven by the research,” Dr. Lang said.

A growing problem

For Diane Francoeur, MD, CEO of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada, this is all well and good, but the reality is that such screening is better than nothing.

Quebec is the only Canadian province that conducts universal screening for all pregnant and postpartum women, Dr. Francoeur said in an interview. She was not part of the task force.

“I agree that it should be more than one approach, but the problem is that there is such a shortage of resources. There are many issues that can arise when you follow a woman during her pregnancy,” she said.

Dr. Francoeur said that COVID-19 has been particularly tough on women, including pregnant and postpartum women, who are the most vulnerable.

“Especially during the COVID era, it was astonishing how women were not doing well. Their stress level was so high. We need to have a specific approach dedicated to prenatal mental health, because it’s a problem that is bigger than it used to be,” she said.

Violence against women has increased considerably since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Francoeur. “Many more women have been killed by their partners. We have never seen anything like this before, and I hope we will never see this again,” she said.

“Help was more available a few years ago, but now, it’s really hard if and when you need to have a quick consultation with a specialist and the woman is really depressed. It can take forever. So, it’s okay to screen, but then, what’s next? Who is going to be there to take these women and help them? And we don’t have the answer,” Dr. Francoeur said.

Pregnant and postpartum women who suffer from depression need more than pills, she added. “We reassure them and treat their depression pharmacologically, but it’s also a time to give appropriate support and help them through the pregnancy and get well prepared to receive their newborn, because, as we now know, that first year of life is really important for the child, and the mom needs to be supported.”

Funding for the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada. Dr. Lang and Dr. Francoeur reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommends against the routine screening of all pregnant and postpartum women for depression using a standard questionnaire, according to its new guideline.

The basis for its position is the lack of evidence that such screening “adds value beyond discussions about overall wellbeing, depression, anxiety, and mood that are currently a part of established perinatal clinical care.

“We should not be using a one-size-fits all approach,” lead author Eddy Lang, MD, professor and head of emergency medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary (Alta.), told this news organization.

Instead, the task force emphasizes regular clinical care, including asking patients about their wellbeing and support systems. The task force categorizes the recommendation as conditional and as having very low-certainty evidence.

The recommendation was published in CMAJ.

One randomized study

The task force is an independent panel of clinicians and scientists that makes recommendations on primary and secondary prevention in primary care. A working group of five members of the task force developed this recommendation with scientific support from Public Health Agency of Canada staff.

In its research, the task force found only one study that showed a benefit of routine depression screening in this population. This study was a randomized controlled trial conducted in Hong Kong. Researchers evaluated 462 postpartum women who were randomly assigned to receive screening with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or no screening 2 months post partum.

“We found the effect of screening in this study to be very uncertain for the important outcomes of interest,” said Dr. Lang.

“These included parent-child stress, marital stress, and the number of infant hospital admissions. The effects of screening on all of these outcomes were very uncertain, mainly because it was such a small trial,” he said.

The task force also assessed how pregnant and postpartum women feel about being screened. What these women most wanted was a good relationship with a trusted primary care provider who would initiate discussions about their mental health in a caring atmosphere.

“Although they told us they liked the idea of universal screening, they admitted to their family doctors that they actually preferred to be asked about their wellbeing, [to be asked] how things were going at home, and [to have] a discussion about their mental health and wellbeing, rather than a formal screening process. They felt a discussion about depression with a primary health care provider during the pregnancy and postpartum period is critical,” said Dr. Lang.

Thus, the task force recommends “against instrument-based depression screening using a questionnaire with cutoff score to distinguish ‘screen positive’ and ‘screen negative’ administered to all individuals during pregnancy and the postpartum period (up to 1 year after childbirth).”

Screening remains common

“There’s a lot of uncertainty in the scientific community about whether it’s a good idea to administer a screening test to all pregnant and postpartum women to determine in a systematic way if they might be suffering from depression,” said Dr. Lang.

The task force recommended against screening for depression among perinatal or postpartum women in 2013, but screening is still performed in many provinces, said Dr. Lang.

Dr. Lang emphasized that the recommendation does not apply to usual care, in which the provider asks questions about and discusses a patient’s mental health and proceeds on the basis of their clinical judgment; nor does it apply to diagnostic pathways in which the clinician suspects that the individual may have depression and tests her accordingly.

“What we are saying in our recommendation is that all clinicians should ask about a patient’s wellbeing, about their mood, their anxiety, and these questions are an important part of the clinical assessment of pregnant and postpartum women. But we’re also saying the usefulness of doing so with a questionnaire and using a cutoff score on the questionnaire to decide who needs further assessment or possibly treatment is unproven by the research,” Dr. Lang said.

A growing problem

For Diane Francoeur, MD, CEO of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada, this is all well and good, but the reality is that such screening is better than nothing.

Quebec is the only Canadian province that conducts universal screening for all pregnant and postpartum women, Dr. Francoeur said in an interview. She was not part of the task force.

“I agree that it should be more than one approach, but the problem is that there is such a shortage of resources. There are many issues that can arise when you follow a woman during her pregnancy,” she said.

Dr. Francoeur said that COVID-19 has been particularly tough on women, including pregnant and postpartum women, who are the most vulnerable.

“Especially during the COVID era, it was astonishing how women were not doing well. Their stress level was so high. We need to have a specific approach dedicated to prenatal mental health, because it’s a problem that is bigger than it used to be,” she said.

Violence against women has increased considerably since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Francoeur. “Many more women have been killed by their partners. We have never seen anything like this before, and I hope we will never see this again,” she said.

“Help was more available a few years ago, but now, it’s really hard if and when you need to have a quick consultation with a specialist and the woman is really depressed. It can take forever. So, it’s okay to screen, but then, what’s next? Who is going to be there to take these women and help them? And we don’t have the answer,” Dr. Francoeur said.

Pregnant and postpartum women who suffer from depression need more than pills, she added. “We reassure them and treat their depression pharmacologically, but it’s also a time to give appropriate support and help them through the pregnancy and get well prepared to receive their newborn, because, as we now know, that first year of life is really important for the child, and the mom needs to be supported.”

Funding for the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada. Dr. Lang and Dr. Francoeur reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommends against the routine screening of all pregnant and postpartum women for depression using a standard questionnaire, according to its new guideline.

The basis for its position is the lack of evidence that such screening “adds value beyond discussions about overall wellbeing, depression, anxiety, and mood that are currently a part of established perinatal clinical care.

“We should not be using a one-size-fits all approach,” lead author Eddy Lang, MD, professor and head of emergency medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary (Alta.), told this news organization.

Instead, the task force emphasizes regular clinical care, including asking patients about their wellbeing and support systems. The task force categorizes the recommendation as conditional and as having very low-certainty evidence.

The recommendation was published in CMAJ.

One randomized study

The task force is an independent panel of clinicians and scientists that makes recommendations on primary and secondary prevention in primary care. A working group of five members of the task force developed this recommendation with scientific support from Public Health Agency of Canada staff.

In its research, the task force found only one study that showed a benefit of routine depression screening in this population. This study was a randomized controlled trial conducted in Hong Kong. Researchers evaluated 462 postpartum women who were randomly assigned to receive screening with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or no screening 2 months post partum.

“We found the effect of screening in this study to be very uncertain for the important outcomes of interest,” said Dr. Lang.

“These included parent-child stress, marital stress, and the number of infant hospital admissions. The effects of screening on all of these outcomes were very uncertain, mainly because it was such a small trial,” he said.

The task force also assessed how pregnant and postpartum women feel about being screened. What these women most wanted was a good relationship with a trusted primary care provider who would initiate discussions about their mental health in a caring atmosphere.

“Although they told us they liked the idea of universal screening, they admitted to their family doctors that they actually preferred to be asked about their wellbeing, [to be asked] how things were going at home, and [to have] a discussion about their mental health and wellbeing, rather than a formal screening process. They felt a discussion about depression with a primary health care provider during the pregnancy and postpartum period is critical,” said Dr. Lang.

Thus, the task force recommends “against instrument-based depression screening using a questionnaire with cutoff score to distinguish ‘screen positive’ and ‘screen negative’ administered to all individuals during pregnancy and the postpartum period (up to 1 year after childbirth).”