User login

Telephone triage system can help predict dengue outbreaks

Data collected by a telephone-based hotline system can be used to effectively predict outbreaks of dengue in developing countries weeks ahead of time, according to researchers in Pakistan.

After an outbreak of dengue in Lahore, Pakistan, in 2011, a phone-based helpline system was set up by the province of Punjab to combat the epidemic and to improve surveillance and rapid response capabilities. The system received more than 300,000 calls from September 2011 through the end of 2013, and during the three peaks of dengue cases during that time, calls to the help center strongly correlated to an increase in suspected dengue cases.

While calls correlated to outbreaks, the call system alone left some gaps. During the first peak in 2013, when campaign awareness activity was low, comparatively fewer calls were received. The model used in Punjab also factored in weather, and successfully predicted increases in dengue cases at a subcity level 2-3 weeks in advance. As a result, total case incidence in Punjab decreased from 21,000 in 2011 to 257 in 2012 and to 1,600 in 2013.

“Our system has helped public health officials to take early actions to contain the spread of the disease and provide hospitals an early warning of dengue cases in their vicinity. We believe that this system can also be used for a broad array of diseases beyond dengue and can easily be replicated in other developing countries at low costs,” the investigators concluded.

Read the full study in Science Advances (doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501215).

Data collected by a telephone-based hotline system can be used to effectively predict outbreaks of dengue in developing countries weeks ahead of time, according to researchers in Pakistan.

After an outbreak of dengue in Lahore, Pakistan, in 2011, a phone-based helpline system was set up by the province of Punjab to combat the epidemic and to improve surveillance and rapid response capabilities. The system received more than 300,000 calls from September 2011 through the end of 2013, and during the three peaks of dengue cases during that time, calls to the help center strongly correlated to an increase in suspected dengue cases.

While calls correlated to outbreaks, the call system alone left some gaps. During the first peak in 2013, when campaign awareness activity was low, comparatively fewer calls were received. The model used in Punjab also factored in weather, and successfully predicted increases in dengue cases at a subcity level 2-3 weeks in advance. As a result, total case incidence in Punjab decreased from 21,000 in 2011 to 257 in 2012 and to 1,600 in 2013.

“Our system has helped public health officials to take early actions to contain the spread of the disease and provide hospitals an early warning of dengue cases in their vicinity. We believe that this system can also be used for a broad array of diseases beyond dengue and can easily be replicated in other developing countries at low costs,” the investigators concluded.

Read the full study in Science Advances (doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501215).

Data collected by a telephone-based hotline system can be used to effectively predict outbreaks of dengue in developing countries weeks ahead of time, according to researchers in Pakistan.

After an outbreak of dengue in Lahore, Pakistan, in 2011, a phone-based helpline system was set up by the province of Punjab to combat the epidemic and to improve surveillance and rapid response capabilities. The system received more than 300,000 calls from September 2011 through the end of 2013, and during the three peaks of dengue cases during that time, calls to the help center strongly correlated to an increase in suspected dengue cases.

While calls correlated to outbreaks, the call system alone left some gaps. During the first peak in 2013, when campaign awareness activity was low, comparatively fewer calls were received. The model used in Punjab also factored in weather, and successfully predicted increases in dengue cases at a subcity level 2-3 weeks in advance. As a result, total case incidence in Punjab decreased from 21,000 in 2011 to 257 in 2012 and to 1,600 in 2013.

“Our system has helped public health officials to take early actions to contain the spread of the disease and provide hospitals an early warning of dengue cases in their vicinity. We believe that this system can also be used for a broad array of diseases beyond dengue and can easily be replicated in other developing countries at low costs,” the investigators concluded.

Read the full study in Science Advances (doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501215).

FROM SCIENCE ADVANCES

Number of U.S. Zika cases in pregnant women nears 600

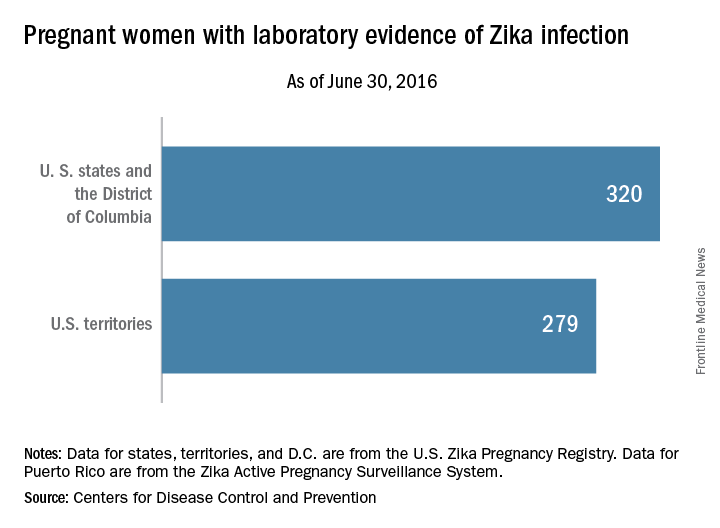

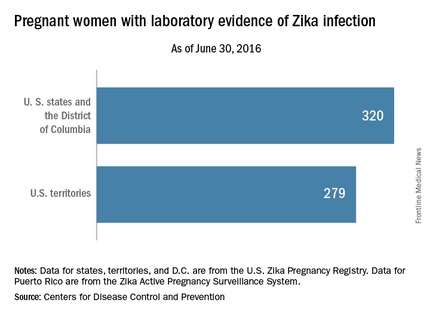

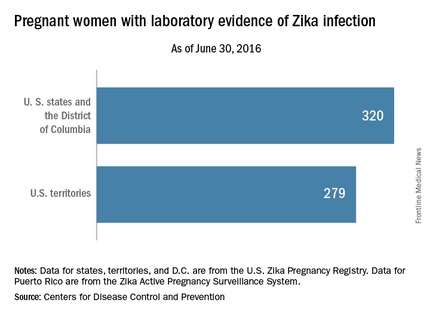

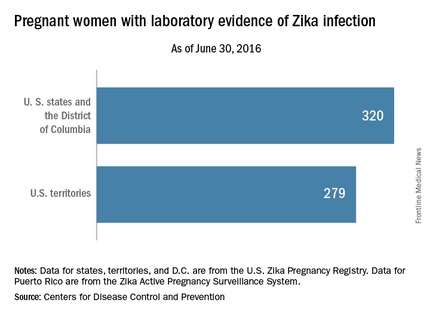

There was one Zika-related pregnancy loss in the United States during the week ending June 30, 2016, bringing the total to six pregnancy losses and seven infants born with birth defects that may be related to maternal Zika virus infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The one pregnancy loss for the week occurred in 1 of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Of the 13 adverse events so far, 12 occurred in the 50 states or D.C., and 1 occurred in a U.S. territory, the CDC reported on July 7. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

For the week ending June 30, there were 33 new reports of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection in the 50 states and D.C., for a total of 320 for the year. Among U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, there were 29 new reports, bringing the total to 279 for the territories and 599 for the entire country, the CDC said.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

These are not real time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

There was one Zika-related pregnancy loss in the United States during the week ending June 30, 2016, bringing the total to six pregnancy losses and seven infants born with birth defects that may be related to maternal Zika virus infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The one pregnancy loss for the week occurred in 1 of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Of the 13 adverse events so far, 12 occurred in the 50 states or D.C., and 1 occurred in a U.S. territory, the CDC reported on July 7. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

For the week ending June 30, there were 33 new reports of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection in the 50 states and D.C., for a total of 320 for the year. Among U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, there were 29 new reports, bringing the total to 279 for the territories and 599 for the entire country, the CDC said.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

These are not real time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

There was one Zika-related pregnancy loss in the United States during the week ending June 30, 2016, bringing the total to six pregnancy losses and seven infants born with birth defects that may be related to maternal Zika virus infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The one pregnancy loss for the week occurred in 1 of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Of the 13 adverse events so far, 12 occurred in the 50 states or D.C., and 1 occurred in a U.S. territory, the CDC reported on July 7. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

For the week ending June 30, there were 33 new reports of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection in the 50 states and D.C., for a total of 320 for the year. Among U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, there were 29 new reports, bringing the total to 279 for the territories and 599 for the entire country, the CDC said.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

These are not real time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika study to focus on U.S. Olympic athletes

Zika virus exposure will be monitored by researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health during the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio De Janeiro.

The study, funded by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and led by Carrie L. Byington, MD, from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, aims to provide answers on the incidence of Zika virus infections, identify risk factors for infections, and detect where the virus persists in the body. The researchers will study the reproductive outcomes of Zika-infected individuals for up to 1 year.

The study is expected to enroll at least 1,000 men and women – a subset of athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) staff members traveling to Brazil for the games.

“Zika virus infection poses many unknown risks, especially to those of reproductive age,” Catherine Y. Spong, MD, acting director of NICHD, said in a statement. “Monitoring the health and reproductive outcomes of members of the U.S. Olympic team offers a unique opportunity to answer important questions and help address an ongoing public health emergency.”

The University of Utah and the USOC conducted a 1-month pilot study during March-April 2016. Among the 150 participants, one-third of the pilot group indicated that they or their partner planned to become pregnant within 12 months of the Olympic Games. Before traveling to Brazil, the entire USOC staff will be briefed on a number of items, including the Zika outbreak. Zika virus testing kits and training on how to use the tests will be provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read more about the study here

Zika virus exposure will be monitored by researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health during the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio De Janeiro.

The study, funded by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and led by Carrie L. Byington, MD, from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, aims to provide answers on the incidence of Zika virus infections, identify risk factors for infections, and detect where the virus persists in the body. The researchers will study the reproductive outcomes of Zika-infected individuals for up to 1 year.

The study is expected to enroll at least 1,000 men and women – a subset of athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) staff members traveling to Brazil for the games.

“Zika virus infection poses many unknown risks, especially to those of reproductive age,” Catherine Y. Spong, MD, acting director of NICHD, said in a statement. “Monitoring the health and reproductive outcomes of members of the U.S. Olympic team offers a unique opportunity to answer important questions and help address an ongoing public health emergency.”

The University of Utah and the USOC conducted a 1-month pilot study during March-April 2016. Among the 150 participants, one-third of the pilot group indicated that they or their partner planned to become pregnant within 12 months of the Olympic Games. Before traveling to Brazil, the entire USOC staff will be briefed on a number of items, including the Zika outbreak. Zika virus testing kits and training on how to use the tests will be provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read more about the study here

Zika virus exposure will be monitored by researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health during the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio De Janeiro.

The study, funded by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and led by Carrie L. Byington, MD, from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, aims to provide answers on the incidence of Zika virus infections, identify risk factors for infections, and detect where the virus persists in the body. The researchers will study the reproductive outcomes of Zika-infected individuals for up to 1 year.

The study is expected to enroll at least 1,000 men and women – a subset of athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) staff members traveling to Brazil for the games.

“Zika virus infection poses many unknown risks, especially to those of reproductive age,” Catherine Y. Spong, MD, acting director of NICHD, said in a statement. “Monitoring the health and reproductive outcomes of members of the U.S. Olympic team offers a unique opportunity to answer important questions and help address an ongoing public health emergency.”

The University of Utah and the USOC conducted a 1-month pilot study during March-April 2016. Among the 150 participants, one-third of the pilot group indicated that they or their partner planned to become pregnant within 12 months of the Olympic Games. Before traveling to Brazil, the entire USOC staff will be briefed on a number of items, including the Zika outbreak. Zika virus testing kits and training on how to use the tests will be provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read more about the study here

Number of U.S. Zika cases in pregnant women up to 537

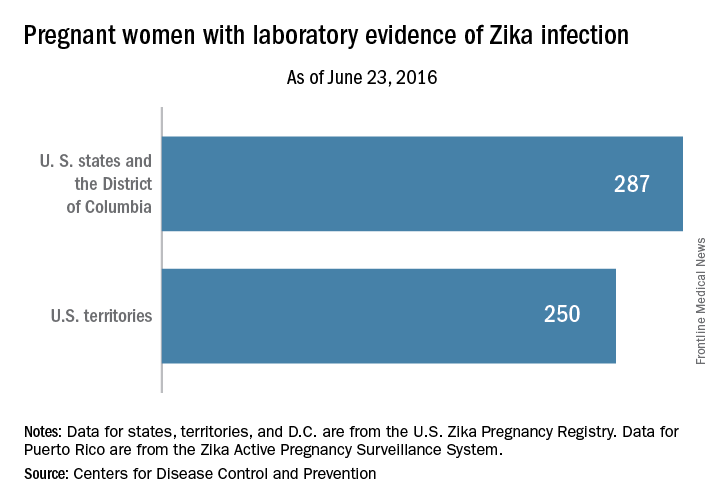

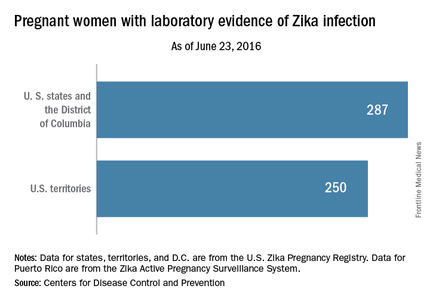

During the week ending June 23, 2016, there were three infants born with birth defects and one pregnancy loss among U.S. women who had been infected with Zika virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The pregnancy-outcomes data, which were posted June 30, show that a total of seven infants have been born in the United States with Zika-related birth defects and that there have been five pregnancy losses with probable Zika-related birth defects, the CDC reported.

For that same week, there were reports of an additional 22 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, bringing the total to 287. Among U.S. territories – American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands – 34 more pregnant women were reported, bringing the territorial number up to 250 and giving the country a total of 537 cases, the CDC said. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System. These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

During the week ending June 23, 2016, there were three infants born with birth defects and one pregnancy loss among U.S. women who had been infected with Zika virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The pregnancy-outcomes data, which were posted June 30, show that a total of seven infants have been born in the United States with Zika-related birth defects and that there have been five pregnancy losses with probable Zika-related birth defects, the CDC reported.

For that same week, there were reports of an additional 22 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, bringing the total to 287. Among U.S. territories – American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands – 34 more pregnant women were reported, bringing the territorial number up to 250 and giving the country a total of 537 cases, the CDC said. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System. These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

During the week ending June 23, 2016, there were three infants born with birth defects and one pregnancy loss among U.S. women who had been infected with Zika virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The pregnancy-outcomes data, which were posted June 30, show that a total of seven infants have been born in the United States with Zika-related birth defects and that there have been five pregnancy losses with probable Zika-related birth defects, the CDC reported.

For that same week, there were reports of an additional 22 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, bringing the total to 287. Among U.S. territories – American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands – 34 more pregnant women were reported, bringing the territorial number up to 250 and giving the country a total of 537 cases, the CDC said. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System. These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Rash, microcephaly not always present with congenital Zika syndrome

The largest study so far of congenital Zika virus syndrome suggests that microcephaly and maternal rash are not sufficient to detect affected babies.

Writing in the June 29 online edition of The Lancet, researchers report on a case series of 1,501 liveborn infants with suspected congenital Zika virus syndrome reported in Brazil. The study found that one in five definite or probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome had a head circumference within the range of normal, and in one third of definite or probable cases, the mother had no history of a rash during pregnancy.

Of the total series, 899 were discarded because they showed no obvious clinical or neuropsychomotor abnormalities such as craniofacial disproportion or neurological symptoms (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[16]30902-3).

Of the remaining 602 cases, 76 were described as definite cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome because of laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Fifty-four babies were considered highly probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome because imaging reports showed features such as brain calcifications and ventricular enlargement suggestive of Zika virus infection and which could not be attributed to other pathogens such as syphilis, cytomegalovirus, or toxoplasmosis.

A further 181 were “moderately probable” – they had similar imaging results to the highly probable group but without test results for other infections – while the 291 somewhat probable cases had imaging results that suggested Zika virus was likely involved.

Among the 391 definitely or probable cases where full information was available, half had both microcephaly and a history of maternal rash, while 87% had at least one of these symptoms.

“There were only two significant differences between the four categories: diagnostic certainty was positively associated with reported rashes and with smaller head circumferences before taking gestational age into account,” wrote Giovanny V. A. França, PhD, of the Secretariat of Health Surveillance, Ministry of Health, Brazil, and coauthors.

Researchers also noted that the discarded cases had larger head circumferences, lower first week mortality, and the mothers were less likely to have a history of rash during pregnancy (20.7% vs 61.4%, 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.42).

Meanwhile, a second case series in the same edition of The Lancet reported on the pathology of five cases of congenital Zika syndrome, providing further evidence of the link between the virus and congenital abnormalities.

Tissue samples from three fatal cases of the syndrome and two spontaneous abortions found antigens to the Zika virus in the cytoplasm of degenerating and necrotic neurons and glial cells, but no immunohistochemical staining for Zika virus was found outside the central nervous system (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[16]30883-2).

The five cases all showed signs of brain abnormalities including microcephaly, lissencephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, and ventriculomegaly, while histopathological studies in the three fatal cases revealed microcalcifications, scattered microglial nodules, cell degeneration, and necrosis.

“The absence of a substantial inflammatory response in the brain and a specific cytopathic viral effect distinguishes Zika virus infection from other important viral infections that are also associated with microcephaly and microcalcifications, such as cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus,” wrote Roosecelis Brasil Martines, MD, of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC, and coauthors.

There was also a range of other congenital malformations evident in the three fatal cases, including multiple congenital contractures, craniofacial malformations, craniosynostosis, pulmonary hypoplasia, and a wide range of brain abnormalities.

“The mechanism for these deformities in Zika virus infection are not entirely clear, but most probably result from neurotropism of the virus with subsequent damage of the brain and interference in neuromuscular signaling leading to fetal akinesia,” the authors said.

No conflicts of interest were declared for either study.

This study is an important contribution for improving the surveillance system for congenital Zika virus infection but caution should be taken in interpreting results of this case series based on routinely collected data with missing information for many cases and an unknown degree of under-reporting.

For incorporating new information besides microcephaly and rash during pregnancy to detect all affected cases, neurological signs and symptoms could be eligible, but might be difficult to obtain in most settings because of insufficient specialized personnel. The development of an accurate serological test that could be incorporated into routine prenatal care will be essential, and its validation a research priority.

While the current outbreak is a paradigmatic example of how quickly evolving systematic scientific evidence can (and should) change the view on a disease within months, it can be expected that public health authorities, and also the scientific community, will struggle for many years with Zika epidemics and its consequences in Brazil and elsewhere.

Jörg Heukelbach, MD, is from the School of Medicine at the Federal University of Ceará in Brazil, and Guilherme Loureiro Werneck, MD, is from the Social Medicine Institute at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. The comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30931-X). No conflicts of interest were declared.

This study is an important contribution for improving the surveillance system for congenital Zika virus infection but caution should be taken in interpreting results of this case series based on routinely collected data with missing information for many cases and an unknown degree of under-reporting.

For incorporating new information besides microcephaly and rash during pregnancy to detect all affected cases, neurological signs and symptoms could be eligible, but might be difficult to obtain in most settings because of insufficient specialized personnel. The development of an accurate serological test that could be incorporated into routine prenatal care will be essential, and its validation a research priority.

While the current outbreak is a paradigmatic example of how quickly evolving systematic scientific evidence can (and should) change the view on a disease within months, it can be expected that public health authorities, and also the scientific community, will struggle for many years with Zika epidemics and its consequences in Brazil and elsewhere.

Jörg Heukelbach, MD, is from the School of Medicine at the Federal University of Ceará in Brazil, and Guilherme Loureiro Werneck, MD, is from the Social Medicine Institute at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. The comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30931-X). No conflicts of interest were declared.

This study is an important contribution for improving the surveillance system for congenital Zika virus infection but caution should be taken in interpreting results of this case series based on routinely collected data with missing information for many cases and an unknown degree of under-reporting.

For incorporating new information besides microcephaly and rash during pregnancy to detect all affected cases, neurological signs and symptoms could be eligible, but might be difficult to obtain in most settings because of insufficient specialized personnel. The development of an accurate serological test that could be incorporated into routine prenatal care will be essential, and its validation a research priority.

While the current outbreak is a paradigmatic example of how quickly evolving systematic scientific evidence can (and should) change the view on a disease within months, it can be expected that public health authorities, and also the scientific community, will struggle for many years with Zika epidemics and its consequences in Brazil and elsewhere.

Jörg Heukelbach, MD, is from the School of Medicine at the Federal University of Ceará in Brazil, and Guilherme Loureiro Werneck, MD, is from the Social Medicine Institute at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. The comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30931-X). No conflicts of interest were declared.

The largest study so far of congenital Zika virus syndrome suggests that microcephaly and maternal rash are not sufficient to detect affected babies.

Writing in the June 29 online edition of The Lancet, researchers report on a case series of 1,501 liveborn infants with suspected congenital Zika virus syndrome reported in Brazil. The study found that one in five definite or probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome had a head circumference within the range of normal, and in one third of definite or probable cases, the mother had no history of a rash during pregnancy.

Of the total series, 899 were discarded because they showed no obvious clinical or neuropsychomotor abnormalities such as craniofacial disproportion or neurological symptoms (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[16]30902-3).

Of the remaining 602 cases, 76 were described as definite cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome because of laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Fifty-four babies were considered highly probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome because imaging reports showed features such as brain calcifications and ventricular enlargement suggestive of Zika virus infection and which could not be attributed to other pathogens such as syphilis, cytomegalovirus, or toxoplasmosis.

A further 181 were “moderately probable” – they had similar imaging results to the highly probable group but without test results for other infections – while the 291 somewhat probable cases had imaging results that suggested Zika virus was likely involved.

Among the 391 definitely or probable cases where full information was available, half had both microcephaly and a history of maternal rash, while 87% had at least one of these symptoms.

“There were only two significant differences between the four categories: diagnostic certainty was positively associated with reported rashes and with smaller head circumferences before taking gestational age into account,” wrote Giovanny V. A. França, PhD, of the Secretariat of Health Surveillance, Ministry of Health, Brazil, and coauthors.

Researchers also noted that the discarded cases had larger head circumferences, lower first week mortality, and the mothers were less likely to have a history of rash during pregnancy (20.7% vs 61.4%, 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.42).

Meanwhile, a second case series in the same edition of The Lancet reported on the pathology of five cases of congenital Zika syndrome, providing further evidence of the link between the virus and congenital abnormalities.

Tissue samples from three fatal cases of the syndrome and two spontaneous abortions found antigens to the Zika virus in the cytoplasm of degenerating and necrotic neurons and glial cells, but no immunohistochemical staining for Zika virus was found outside the central nervous system (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[16]30883-2).

The five cases all showed signs of brain abnormalities including microcephaly, lissencephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, and ventriculomegaly, while histopathological studies in the three fatal cases revealed microcalcifications, scattered microglial nodules, cell degeneration, and necrosis.

“The absence of a substantial inflammatory response in the brain and a specific cytopathic viral effect distinguishes Zika virus infection from other important viral infections that are also associated with microcephaly and microcalcifications, such as cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus,” wrote Roosecelis Brasil Martines, MD, of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC, and coauthors.

There was also a range of other congenital malformations evident in the three fatal cases, including multiple congenital contractures, craniofacial malformations, craniosynostosis, pulmonary hypoplasia, and a wide range of brain abnormalities.

“The mechanism for these deformities in Zika virus infection are not entirely clear, but most probably result from neurotropism of the virus with subsequent damage of the brain and interference in neuromuscular signaling leading to fetal akinesia,” the authors said.

No conflicts of interest were declared for either study.

The largest study so far of congenital Zika virus syndrome suggests that microcephaly and maternal rash are not sufficient to detect affected babies.

Writing in the June 29 online edition of The Lancet, researchers report on a case series of 1,501 liveborn infants with suspected congenital Zika virus syndrome reported in Brazil. The study found that one in five definite or probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome had a head circumference within the range of normal, and in one third of definite or probable cases, the mother had no history of a rash during pregnancy.

Of the total series, 899 were discarded because they showed no obvious clinical or neuropsychomotor abnormalities such as craniofacial disproportion or neurological symptoms (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[16]30902-3).

Of the remaining 602 cases, 76 were described as definite cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome because of laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Fifty-four babies were considered highly probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome because imaging reports showed features such as brain calcifications and ventricular enlargement suggestive of Zika virus infection and which could not be attributed to other pathogens such as syphilis, cytomegalovirus, or toxoplasmosis.

A further 181 were “moderately probable” – they had similar imaging results to the highly probable group but without test results for other infections – while the 291 somewhat probable cases had imaging results that suggested Zika virus was likely involved.

Among the 391 definitely or probable cases where full information was available, half had both microcephaly and a history of maternal rash, while 87% had at least one of these symptoms.

“There were only two significant differences between the four categories: diagnostic certainty was positively associated with reported rashes and with smaller head circumferences before taking gestational age into account,” wrote Giovanny V. A. França, PhD, of the Secretariat of Health Surveillance, Ministry of Health, Brazil, and coauthors.

Researchers also noted that the discarded cases had larger head circumferences, lower first week mortality, and the mothers were less likely to have a history of rash during pregnancy (20.7% vs 61.4%, 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.42).

Meanwhile, a second case series in the same edition of The Lancet reported on the pathology of five cases of congenital Zika syndrome, providing further evidence of the link between the virus and congenital abnormalities.

Tissue samples from three fatal cases of the syndrome and two spontaneous abortions found antigens to the Zika virus in the cytoplasm of degenerating and necrotic neurons and glial cells, but no immunohistochemical staining for Zika virus was found outside the central nervous system (Lancet. 2016 Jun 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[16]30883-2).

The five cases all showed signs of brain abnormalities including microcephaly, lissencephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, and ventriculomegaly, while histopathological studies in the three fatal cases revealed microcalcifications, scattered microglial nodules, cell degeneration, and necrosis.

“The absence of a substantial inflammatory response in the brain and a specific cytopathic viral effect distinguishes Zika virus infection from other important viral infections that are also associated with microcephaly and microcalcifications, such as cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus,” wrote Roosecelis Brasil Martines, MD, of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC, and coauthors.

There was also a range of other congenital malformations evident in the three fatal cases, including multiple congenital contractures, craniofacial malformations, craniosynostosis, pulmonary hypoplasia, and a wide range of brain abnormalities.

“The mechanism for these deformities in Zika virus infection are not entirely clear, but most probably result from neurotropism of the virus with subsequent damage of the brain and interference in neuromuscular signaling leading to fetal akinesia,” the authors said.

No conflicts of interest were declared for either study.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Microcephaly and maternal rash alone are not sufficient to detect babies affected by congenital Zika virus syndrome.

Major finding: One in five definite or probable cases of congenital Zika virus syndrome had a head circumference within the range of normal, and in one third of definite or probable cases, the mother had no history of a rash during pregnancy.

Data source: Case series of 1,501 liveborn infants with suspected congenital Zika virus syndrome.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Zika vaccine development to get underway

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) has announced that they will provide up to $21.9 million to help develop a vaccine for the Zika virus.

Emergent BioSolutions’ Center for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing will conduct the early stages of vaccine development and will submit any candidate vaccines for an investigational drug request to the Food and Drug Administration to begin clinical studies.

At any stage in development, the technology could be transferred to other vaccine manufacturers to produce and market any vaccine developed.

“The threat posed by Zika presents an urgent need for vaccines and diagnostics,” Richard J. Hatchett, MD, acting director of ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, said in a statement. “To meet that need as quickly as possible, we need to leverage the infrastructure, experience, and expertise available within BARDA, other federal agencies, industry, and academia.”

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) has announced that they will provide up to $21.9 million to help develop a vaccine for the Zika virus.

Emergent BioSolutions’ Center for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing will conduct the early stages of vaccine development and will submit any candidate vaccines for an investigational drug request to the Food and Drug Administration to begin clinical studies.

At any stage in development, the technology could be transferred to other vaccine manufacturers to produce and market any vaccine developed.

“The threat posed by Zika presents an urgent need for vaccines and diagnostics,” Richard J. Hatchett, MD, acting director of ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, said in a statement. “To meet that need as quickly as possible, we need to leverage the infrastructure, experience, and expertise available within BARDA, other federal agencies, industry, and academia.”

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) has announced that they will provide up to $21.9 million to help develop a vaccine for the Zika virus.

Emergent BioSolutions’ Center for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing will conduct the early stages of vaccine development and will submit any candidate vaccines for an investigational drug request to the Food and Drug Administration to begin clinical studies.

At any stage in development, the technology could be transferred to other vaccine manufacturers to produce and market any vaccine developed.

“The threat posed by Zika presents an urgent need for vaccines and diagnostics,” Richard J. Hatchett, MD, acting director of ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, said in a statement. “To meet that need as quickly as possible, we need to leverage the infrastructure, experience, and expertise available within BARDA, other federal agencies, industry, and academia.”

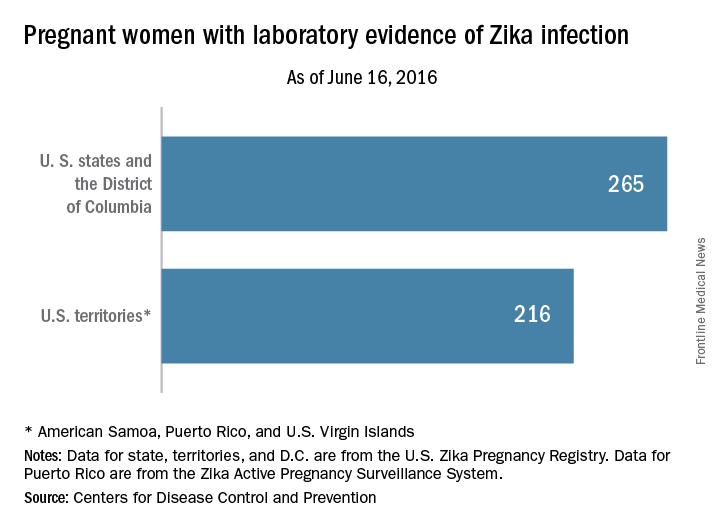

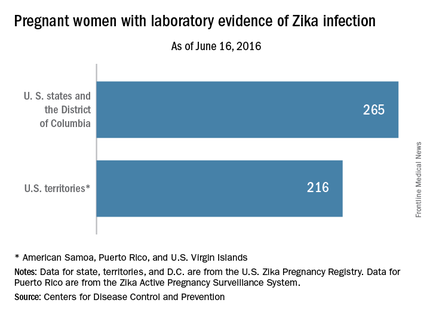

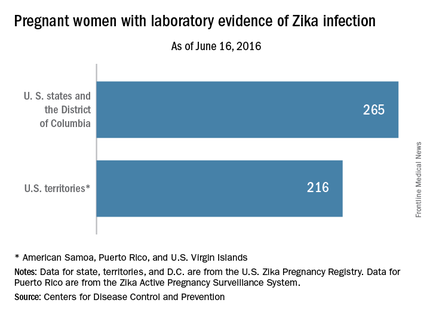

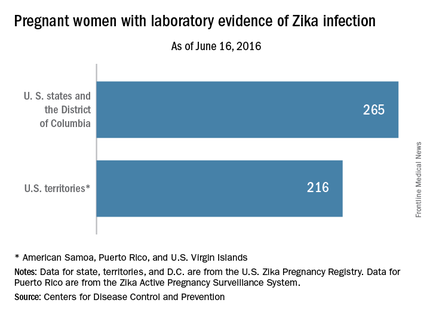

Cases of Zika among pregnant women in U.S. states rise to 265

There was one infant born with birth defects and two pregnancy losses as a result of likely maternal Zika virus infection among U.S. women during the week ending June 16, 2016, according to figures released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That brings the Zika-related totals to four infants born with birth defects and five pregnancy losses in the United States, with one of the most recent pregnancy losses occurring in a U.S. territory or Puerto Rico, the CDC reported. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The CDC also said that it has received reports of 265 pregnant women in U.S. states and the District of Columbia and 216 pregnant women in U.S. territories and Puerto Rico who had any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection. This includes women “in whom viral particles have been detected and those with evidence of an immune reaction to a recent virus that is likely to be Zika,” the CDC noted.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System. These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. The numbers also do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

CDC officials plan to update the pregnancy outcome data every Thursday at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html.

There was one infant born with birth defects and two pregnancy losses as a result of likely maternal Zika virus infection among U.S. women during the week ending June 16, 2016, according to figures released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That brings the Zika-related totals to four infants born with birth defects and five pregnancy losses in the United States, with one of the most recent pregnancy losses occurring in a U.S. territory or Puerto Rico, the CDC reported. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The CDC also said that it has received reports of 265 pregnant women in U.S. states and the District of Columbia and 216 pregnant women in U.S. territories and Puerto Rico who had any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection. This includes women “in whom viral particles have been detected and those with evidence of an immune reaction to a recent virus that is likely to be Zika,” the CDC noted.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System. These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. The numbers also do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

CDC officials plan to update the pregnancy outcome data every Thursday at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html.

There was one infant born with birth defects and two pregnancy losses as a result of likely maternal Zika virus infection among U.S. women during the week ending June 16, 2016, according to figures released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That brings the Zika-related totals to four infants born with birth defects and five pregnancy losses in the United States, with one of the most recent pregnancy losses occurring in a U.S. territory or Puerto Rico, the CDC reported. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The CDC also said that it has received reports of 265 pregnant women in U.S. states and the District of Columbia and 216 pregnant women in U.S. territories and Puerto Rico who had any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection. This includes women “in whom viral particles have been detected and those with evidence of an immune reaction to a recent virus that is likely to be Zika,” the CDC noted.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System. These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. The numbers also do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

CDC officials plan to update the pregnancy outcome data every Thursday at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html.

Abortion requests surged in Latin American countries after Zika warnings

Requests for medication abortions have risen significantly in nine Latin American countries since the Pan American Health Organization issued an epidemiologic warning about Zika virus in November 2015.

All of the countries have legal restrictions that make abortions impossible or very difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, women are seeking them in increasing numbers using Women on Web, a nonprofit, international group that supplies information on abortions and facilitates contact with physicians who provide abortifacient medications.

Dr. Abigail Aiken of the University of Texas, Austin, and her colleagues reported the findings June 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1605389).

Most of the increased requests occurred in countries that issued a national advisory to pregnant women, the researchers noted. But increases also occurred in two countries with local Zika transmission but no national advisory.

“We cannot definitively attribute the rapid acceleration in requests … to concern about Zika virus exposure,” the researchers wrote in a letter to the editor. However, “In Latin American countries that issued warnings to pregnant women about complications associated with Zika virus infection, requests for abortion through [Women on Web] increased significantly. Our approach may underestimate the effect of the advisories on demand for abortion, since many women may have used an unsafe method, accessed misoprostol from local pharmacies or the black market, or visited local underground providers.”

The authors worked with Women on Web to assess requests for medical abortion consultations from women in 19 Latin American countries between Jan. 1, 2010, and March 2, 2016. They compared these numbers before and after the November 2015 Zika announcement from the Pan American Health Organization.

They divided the data into three groups: countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and a national advisory to pregnant women; countries with no Zika transmission and legally restricted abortion; and countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and no national advisory to pregnant women. The study also included three control countries with no Zika transmission anticipated (Chile, Poland, and Uruguay).

All of the eight countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and a national advisory to pregnant women showed significant increases in Women on Web requests, except Jamaica. The increases were highest in Brazil and Ecuador (108%) and lowest in El Salvador and Costa Rica (36%). The increases reported reflect the relative change between actual and expected requests for abortion medications.

Two of the four countries with no Zika transmission and legally restricted abortion also showed increases: Peru (20.5%) and Argentina (21.8%).

There were no significant increases in requests in any of the seven countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and no national advisory to pregnant women.

The findings suggest a difficult future for many women who desire pregnancy or who conceive in areas of Zika activity, the researchers wrote. “Models that were developed by the World Health Organization predict that 3 million to 4 million persons across the Americas will contract Zika virus infection through 2017, and the virus will inevitably spread to other countries where access to safe abortion is restricted. Official information and advice about potential exposure to the Zika virus should be accompanied by efforts to ensure that all reproductive choices are safe, legal, and accessible.”

Dr. Thomas Gellhaus, president of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), said the study “presents alarming insight on how the Zika virus is affecting the lives of pregnant women.”

“ACOG has long recognized that access to reproductive services, including abortion care, is essential for all women,” he said. “All women, must have the legal right to abortion, unconstrained by harassment, unavailability of care, procedure bans, or other legislative or regulatory barriers. The Zika crisis makes it impossible to ignore that women around the world do not have access to this basic health care need.”

ACOG updated its Zika clinical guidelines on June 13.

Two of the researchers are affiliated with Women on Web.

Requests for medication abortions have risen significantly in nine Latin American countries since the Pan American Health Organization issued an epidemiologic warning about Zika virus in November 2015.

All of the countries have legal restrictions that make abortions impossible or very difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, women are seeking them in increasing numbers using Women on Web, a nonprofit, international group that supplies information on abortions and facilitates contact with physicians who provide abortifacient medications.

Dr. Abigail Aiken of the University of Texas, Austin, and her colleagues reported the findings June 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1605389).

Most of the increased requests occurred in countries that issued a national advisory to pregnant women, the researchers noted. But increases also occurred in two countries with local Zika transmission but no national advisory.

“We cannot definitively attribute the rapid acceleration in requests … to concern about Zika virus exposure,” the researchers wrote in a letter to the editor. However, “In Latin American countries that issued warnings to pregnant women about complications associated with Zika virus infection, requests for abortion through [Women on Web] increased significantly. Our approach may underestimate the effect of the advisories on demand for abortion, since many women may have used an unsafe method, accessed misoprostol from local pharmacies or the black market, or visited local underground providers.”

The authors worked with Women on Web to assess requests for medical abortion consultations from women in 19 Latin American countries between Jan. 1, 2010, and March 2, 2016. They compared these numbers before and after the November 2015 Zika announcement from the Pan American Health Organization.

They divided the data into three groups: countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and a national advisory to pregnant women; countries with no Zika transmission and legally restricted abortion; and countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and no national advisory to pregnant women. The study also included three control countries with no Zika transmission anticipated (Chile, Poland, and Uruguay).

All of the eight countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and a national advisory to pregnant women showed significant increases in Women on Web requests, except Jamaica. The increases were highest in Brazil and Ecuador (108%) and lowest in El Salvador and Costa Rica (36%). The increases reported reflect the relative change between actual and expected requests for abortion medications.

Two of the four countries with no Zika transmission and legally restricted abortion also showed increases: Peru (20.5%) and Argentina (21.8%).

There were no significant increases in requests in any of the seven countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and no national advisory to pregnant women.

The findings suggest a difficult future for many women who desire pregnancy or who conceive in areas of Zika activity, the researchers wrote. “Models that were developed by the World Health Organization predict that 3 million to 4 million persons across the Americas will contract Zika virus infection through 2017, and the virus will inevitably spread to other countries where access to safe abortion is restricted. Official information and advice about potential exposure to the Zika virus should be accompanied by efforts to ensure that all reproductive choices are safe, legal, and accessible.”

Dr. Thomas Gellhaus, president of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), said the study “presents alarming insight on how the Zika virus is affecting the lives of pregnant women.”

“ACOG has long recognized that access to reproductive services, including abortion care, is essential for all women,” he said. “All women, must have the legal right to abortion, unconstrained by harassment, unavailability of care, procedure bans, or other legislative or regulatory barriers. The Zika crisis makes it impossible to ignore that women around the world do not have access to this basic health care need.”

ACOG updated its Zika clinical guidelines on June 13.

Two of the researchers are affiliated with Women on Web.

Requests for medication abortions have risen significantly in nine Latin American countries since the Pan American Health Organization issued an epidemiologic warning about Zika virus in November 2015.

All of the countries have legal restrictions that make abortions impossible or very difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, women are seeking them in increasing numbers using Women on Web, a nonprofit, international group that supplies information on abortions and facilitates contact with physicians who provide abortifacient medications.

Dr. Abigail Aiken of the University of Texas, Austin, and her colleagues reported the findings June 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1605389).

Most of the increased requests occurred in countries that issued a national advisory to pregnant women, the researchers noted. But increases also occurred in two countries with local Zika transmission but no national advisory.

“We cannot definitively attribute the rapid acceleration in requests … to concern about Zika virus exposure,” the researchers wrote in a letter to the editor. However, “In Latin American countries that issued warnings to pregnant women about complications associated with Zika virus infection, requests for abortion through [Women on Web] increased significantly. Our approach may underestimate the effect of the advisories on demand for abortion, since many women may have used an unsafe method, accessed misoprostol from local pharmacies or the black market, or visited local underground providers.”

The authors worked with Women on Web to assess requests for medical abortion consultations from women in 19 Latin American countries between Jan. 1, 2010, and March 2, 2016. They compared these numbers before and after the November 2015 Zika announcement from the Pan American Health Organization.

They divided the data into three groups: countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and a national advisory to pregnant women; countries with no Zika transmission and legally restricted abortion; and countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and no national advisory to pregnant women. The study also included three control countries with no Zika transmission anticipated (Chile, Poland, and Uruguay).

All of the eight countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and a national advisory to pregnant women showed significant increases in Women on Web requests, except Jamaica. The increases were highest in Brazil and Ecuador (108%) and lowest in El Salvador and Costa Rica (36%). The increases reported reflect the relative change between actual and expected requests for abortion medications.

Two of the four countries with no Zika transmission and legally restricted abortion also showed increases: Peru (20.5%) and Argentina (21.8%).

There were no significant increases in requests in any of the seven countries with local Zika transmission, legally restricted abortion, and no national advisory to pregnant women.

The findings suggest a difficult future for many women who desire pregnancy or who conceive in areas of Zika activity, the researchers wrote. “Models that were developed by the World Health Organization predict that 3 million to 4 million persons across the Americas will contract Zika virus infection through 2017, and the virus will inevitably spread to other countries where access to safe abortion is restricted. Official information and advice about potential exposure to the Zika virus should be accompanied by efforts to ensure that all reproductive choices are safe, legal, and accessible.”

Dr. Thomas Gellhaus, president of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), said the study “presents alarming insight on how the Zika virus is affecting the lives of pregnant women.”

“ACOG has long recognized that access to reproductive services, including abortion care, is essential for all women,” he said. “All women, must have the legal right to abortion, unconstrained by harassment, unavailability of care, procedure bans, or other legislative or regulatory barriers. The Zika crisis makes it impossible to ignore that women around the world do not have access to this basic health care need.”

ACOG updated its Zika clinical guidelines on June 13.

Two of the researchers are affiliated with Women on Web.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Requests for medication abortions have risen in nine Latin American countries since the first Zika warning last November.

Major finding: Requests for abortifacient medications in Brazil and Ecuador rose by about 108%, compared with expected requests.

Data source: The study compared data between Jan. 1, 2010, and March 2, 2016.

Disclosures: Two of the researchers are affiliated with Women on Web, a nonprofit, international group that supplies information on abortions and facilitates contact with physicians who provide abortifacient medications.

NYC launches surveillance system to detect local Zika virus transmission

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) will implement a sentinel surveillance system to detect cases of local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus for the upcoming peak mosquito-biting season.

With the large number of people who travel frequently from New York City to active Zika virus transmission areas, DOHMH has chosen 21 primary care clinics and emergency departments as the sentinel sites across all five New York City boroughs. Once any suspected cases are reported to DOHMH, urine will be obtained for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing.

During Jan. 1.–June 17, 2016, DOHMH coordinated diagnostic laboratory testing of 3,605 patients with travel-associated exposure, including 182 (5.0%) who had the Zika virus infection. Out of the 182 patients, 20 (11.0%) were pregnant at the time of diagnosis and two cases of Zika virus–associated Guillain-Barré syndrome were diagnosed.

“Because of the known potential for Aedes mosquitoes to transmit Zika virus among humans, the anticipated large number of imported human cases into NYC, and the temporal lag between viremia and disease diagnosis in an infected patient, DOHMH is augmenting its mosquito control program, specifically source control, as well as larviciding and adult mosquito control,” Dr. Christopher T. Lee and his associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Additionally, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is partnering with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (known as Fiocruz) to begin a multi-country study to investigate the magnitude of health risks that the Zika virus poses to pregnant women and their developing fetuses and infants. The study will begin in Puerto Rico and expand to other locations in Brazil, Colombia, and other areas impacted by active local transmission of the virus.

“This study, in partnership with NIH, is essential to elucidating the scientific complexity of the Zika virus,” Fiocruz President Paulo Gadelha said in a statement. “It will be fundamental to developing prevention and treatment strategies against the disease.”

Read the full report on the New York City Zika experience in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6524e3).

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) will implement a sentinel surveillance system to detect cases of local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus for the upcoming peak mosquito-biting season.

With the large number of people who travel frequently from New York City to active Zika virus transmission areas, DOHMH has chosen 21 primary care clinics and emergency departments as the sentinel sites across all five New York City boroughs. Once any suspected cases are reported to DOHMH, urine will be obtained for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing.

During Jan. 1.–June 17, 2016, DOHMH coordinated diagnostic laboratory testing of 3,605 patients with travel-associated exposure, including 182 (5.0%) who had the Zika virus infection. Out of the 182 patients, 20 (11.0%) were pregnant at the time of diagnosis and two cases of Zika virus–associated Guillain-Barré syndrome were diagnosed.

“Because of the known potential for Aedes mosquitoes to transmit Zika virus among humans, the anticipated large number of imported human cases into NYC, and the temporal lag between viremia and disease diagnosis in an infected patient, DOHMH is augmenting its mosquito control program, specifically source control, as well as larviciding and adult mosquito control,” Dr. Christopher T. Lee and his associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Additionally, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is partnering with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (known as Fiocruz) to begin a multi-country study to investigate the magnitude of health risks that the Zika virus poses to pregnant women and their developing fetuses and infants. The study will begin in Puerto Rico and expand to other locations in Brazil, Colombia, and other areas impacted by active local transmission of the virus.

“This study, in partnership with NIH, is essential to elucidating the scientific complexity of the Zika virus,” Fiocruz President Paulo Gadelha said in a statement. “It will be fundamental to developing prevention and treatment strategies against the disease.”

Read the full report on the New York City Zika experience in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6524e3).

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) will implement a sentinel surveillance system to detect cases of local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus for the upcoming peak mosquito-biting season.

With the large number of people who travel frequently from New York City to active Zika virus transmission areas, DOHMH has chosen 21 primary care clinics and emergency departments as the sentinel sites across all five New York City boroughs. Once any suspected cases are reported to DOHMH, urine will be obtained for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing.

During Jan. 1.–June 17, 2016, DOHMH coordinated diagnostic laboratory testing of 3,605 patients with travel-associated exposure, including 182 (5.0%) who had the Zika virus infection. Out of the 182 patients, 20 (11.0%) were pregnant at the time of diagnosis and two cases of Zika virus–associated Guillain-Barré syndrome were diagnosed.

“Because of the known potential for Aedes mosquitoes to transmit Zika virus among humans, the anticipated large number of imported human cases into NYC, and the temporal lag between viremia and disease diagnosis in an infected patient, DOHMH is augmenting its mosquito control program, specifically source control, as well as larviciding and adult mosquito control,” Dr. Christopher T. Lee and his associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Additionally, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is partnering with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (known as Fiocruz) to begin a multi-country study to investigate the magnitude of health risks that the Zika virus poses to pregnant women and their developing fetuses and infants. The study will begin in Puerto Rico and expand to other locations in Brazil, Colombia, and other areas impacted by active local transmission of the virus.

“This study, in partnership with NIH, is essential to elucidating the scientific complexity of the Zika virus,” Fiocruz President Paulo Gadelha said in a statement. “It will be fundamental to developing prevention and treatment strategies against the disease.”

Read the full report on the New York City Zika experience in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6524e3).

FROM MMWR

Zika virus: The path to fetal infection

The question of how viruses can enter the intrauterine compartment and infect the fetus has long been a focus of research. It is of particular urgency today as the Zika virus spreads and causes perinatal infection that threatens the developing fetus with serious adverse outcomes such microcephaly and other brain anomalies, placental insufficiency, and fetal growth restriction.

We know that viruses can take a variety of routes to the fetal compartment, but we have also learned that the placenta has a robust level of inherent resistance to viruses. This resistance likely explains why we don’t see more viral infections in pregnancy.

Recent studies performed at our institution suggest that placental trophoblasts – the placenta’s primary line of defense – have inherent resistance to viruses such as Zika. It appears, therefore, that the Zika virus invades the intrauterine cavity by crossing the trophoblasts, perhaps earlier in pregnancy and prior to the development of full trophoblast resistance, by entering through breaks in this outer layer, or by utilizing alternative pathways to access the fetal compartment.

Further study of the placenta and its various cell types and mechanisms of viral defense will be critical for designing therapeutic strategies for preventing perinatal infections.

Various routes and affinities

Viruses have long been known to affect mothers and their unborn children. The rubella virus, for instance, posed a significant threat to the fetus until a vaccine program was introduced almost 50 years ago. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), on the other hand, continues be passed from mothers to their unborn children. While not as threatening as rubella once was, it can in some cases cause severe defects.

One might expect viruses to infect the placenta and then secondarily infect the fetus. While this may indeed occur, direct placental infection is not the only route by which viruses may enter the intrauterine compartment. Some viruses may be carried by macrophages or other immune cells through the placenta and into the fetal compartment, while others colonize the uterine cavity prior to conception, ready to proliferate during pregnancy.

In still other cases, viruses may be inadvertently introduced during medical procedures such as amniocentesis or transmitted through transvaginal ascending infection, most likely after rupture of the membranes. Viruses may also be transported through infected sperm (this appears to be one of the Zika virus’s modes of transportation), and as is the case with HIV and herpes simplex viruses, transmission sometimes occurs during delivery.

When we investigate whether or not the fetus is protected against particular viruses, we must therefore think about the multifaceted mechanisms by which viruses may be transmitted. With respect to the placenta specifically, we seek to understand how viruses enter the placenta, and how the placenta resists the propagation of some viruses while allowing other viruses to gain entry to the intrauterine compartment.

An additional consideration – one that is of utmost importance in the case of Zika – is whether viruses have any special affinity for particular fetal tissues. Some viruses, like CMV, infect multiple types of fetal tissue. The Zika virus, on the other hand, appears to target neuronal tissue in the fetus. In May, investigators of two studies reported that a strain of the Zika virus efficiently infected human cortical neural progenitor cells (Cell Stem Cell. 2016 May 5;18[5]:587-90), and that Zika infection of mice early in pregnancy resulted in infection of the placenta and of the fetal brain (Cell. 2016 May 19;165[5]:1081-91).

Interestingly, other flaviviruses such as the dengue and chikungunya viruses have not been associated with microcephaly or other congenital disorders. This suggests that the Zika virus employs unique mechanisms to infect or bypass the placental barrier and, in turn, to cause neuronal-focused damage.

Placental passage

The villous trophoblasts, cells that are bathed in maternal blood, form the placenta’s first line of defense. Viruses, including the Zika virus, must cross or somehow bypass this initial barrier before crossing the placental basement membrane and endothelial cells, if they are to potentially invade the intrauterine cavity and infect the fetal brain and other tissues.

Research has demonstrated that cells of various types of tissue may express certain proteins, such as AXL, MER and TYRO3. While not yet proven, these proteins may mediate the entry of viruses such as Zika, enabling them to cross the placental trophoblast layer. These proteins are indeed expressed in trophoblasts, especially in early pregnancy, but we do not yet know if the proteins actually aid Zika’s passage through the placenta.

Another mechanism that has been postulated in the case of Zika infection is antibody-dependent enhancement, a process by which a current infection is enhanced by prior infection with another virus from the same family. Some experts believe that pre-existing immunity to the dengue virus – another member of the flavivirus family that has been endemic in Brazil – may be enhancing the spread of Zika infection as antibodies against dengue cross-react with the Zika virus.

While antibody-dependent enhancement has been shown to occur and to advance infection in various body systems, it has not been proven to affect the placenta. Until we learn more, we must simply appreciate that the presence of antibodies from another member of a family of viruses does not necessarily confer resistance. Instead, it may enable new infections to advance.

One might view pregnancy as a time of immune compromise, but we have shown in our laboratories that trophoblasts in fact have inherent resistance to a number of viruses. In a recent study, we found that trophoblasts are refractory to direct infection with the Zika virus. We isolated trophoblast cells from healthy full-term human placentas, cultured these cells for several days, and infected them with the Zika virus. We then measured viral replication and compared the infectivity of these cells with the infectivity of human brain microvascular endothelial cells – nontrophoblast cells that served as a control.

Our findings were extremely interesting to us: The trophoblast cells appeared to be significantly more resistant to the Zika virus than the nontrophoblast cells.

We learned, moreover, that this resistance was mediated by a particular interferon released by the trophoblast cells – type III interferon IFN1 – and that this type III interferon appeared to protect not only the trophoblasts but the nontrophoblast cells as well. It acted in both an autocrine and a paracrine manner to protect cells from the Zika virus. When we blocked the antiviral signaling of this interferon, resistance to the virus was attenuated.

These findings suggest that while Zika appears able to cross through the placenta and infect the fetus, the mechanism does not involve direct infection of the trophoblasts, at least in the later stages of pregnancy. The virus must either evade the type III interferon antiviral signals generated by the trophoblasts or somehow bypass these cells to cross the placenta (Cell Host Microbe. 2016 May 11;19[5]:705-12).

Interestingly, the Cell study mentioned above, in which Zika infection of mice early in pregnancy infected placental cells and the brain, also showed reduced Zika presence in the mouse mononuclear trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, in areas of the placenta analogous to the human villi.

Some experts have suggested, based the study of other viruses, that the Zika virus is better able to infect the placenta when the infection occurs early in the first trimester or the second trimester. It is indeed possible – and makes intuitive sense – that first-trimester trophoblasts confer less resistance and a lower level of protection than the mature trophoblasts we studied. At this point, however, we cannot say with certainty whether or not the placenta is more or less permissive to Zika infection at different points in pregnancy.

Interestingly, investigators who prospectively followed a small cohort of pregnant women in Brazil with suspected Zika infection identified abnormalities in fetuses of women who were infected at various points of their pregnancies, even in the third trimester. Fetuses infected in the first trimester had findings suggestive of pathologic change during embryogenesis, but central nervous system abnormalities were seen in fetuses infected as late as 27 weeks of gestation, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412).

The interferon-conferred resistance demonstrated in our recent study is one of two mechanisms we’ve identified by which placental trophoblasts orchestrate resistance to viral infection. In earlier research, we found that resistance can be conferred to nontrophoblast cells by the delivery of micro-RNAs. These micro-RNAs (C19MC miRNAs) are uniquely expressed in the placenta and packaged within trophoblast-derived nanovesicles called exosomes. The nanovesicles can latch onto other cells in the vicinity of the trophoblasts, attenuating viral replication in these recipient cells.

This earlier in-vitro study involved a panel of diverse and unrelated viruses, including coxsackievirus B3, poliovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and human cytomegalovirus (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jul 16;110[29]:12048-53). It did not include the Zika virus, but our ongoing preliminary research suggests that the same mechanisms might be active against Zika.