User login

Nocturnal hypoglycemia halved with insulin degludec vs. glargine

Patients with type 1 diabetes who used insulin degludec as their basal insulin had fewer than half the number of nocturnal hypoglycemia events, compared with patients who used insulin glargine U100, in a head-to-head crossover study with 51 patients who had a history of nighttime hypoglycemia episodes.

Patients with type 1 diabetes who are “struggling with nocturnal hypoglycemia would benefit from insulin degludec treatment,” said Julie M. Brøsen, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Accumulating evidence for less hypoglycemia with insulin degludec

Results from several studies comparing insulin degludec (Tresiba), a second-generation, longer-acting insulin with more stable steady-state performance, with the first-generation basal insulin analogue glargine (Lantus), have built the case that degludec produces fewer hypoglycemia events.

The landmark SWITCH 1 crossover study published in 2017 showed in about 500 patients with type 1 diabetes and a risk factor for hypoglycemia that treatment with insulin degludec led to significantly few total hypoglycemia episodes and significantly fewer nocturnal episodes, compared with insulin glargine.

Next came similar findings from ReFLeCT, a multicenter observational study that followed 556 unselected patients with type 1 diabetes in routine practice settings who switched to insulin degludec following treatment with a different basal insulin. The results again showed a significant drop-off in total, nonsevere, severe, and nocturnal hypoglycemia events.

Homing in on higher-risk patients

The current study, HypoDeg (Insulin Degludec and Symptomatic Nocturnal Hypoglycaemia), ran at 10 Danish centers and enrolled 149 adults with type 1 diabetes who had at least one episode of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia within the prior 2 years, focusing on patients most at risk for future nocturnal hypoglycemia events. In an unusual study design, researchers identified nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes with hourly venous blood samples drawn from a subcutaneous line.

They randomized the patients to basal insulin treatment with either insulin degludec or to insulin glargine U100, allowed their treatment to stabilize for 3 months, and then tallied nocturnal hypoglycemia events for 9 months. They then crossed patients to the alternative basal insulin and repeated the process.

Results from the full study have not yet appeared in published form but were in a pair of reports at the 2020 scientific sessions of the ADA.

One report included findings based on 136 episodes of severe hypoglycemia identified clinically and showed these events occurred 35% less often during treatment with insulin degludec, a significant difference. The overall finding was primarily driven by 48% fewer episodes of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia, but this difference was not significant.

The second report identified hypoglycemia events with continuous glucose monitoring in 74 of the study participants, which identified 193 episodes of nonsevere nocturnal hypoglycemia and found that treatment with insulin degludec cut the rate by 47%, primarily by reducing asymptomatic episodes.

Hourly blood draws track overnight hypoglycemia

The current study included 51 of the 149 HypoDeg patients who agreed to undergo overnight blood sampling and had this done at least once while treated with each of the two study insulins. (The study design called for two blood sampling nights for each willing patient during each of the two treatment periods.) The 51 patients had type 1 diabetes for an average of 28 years and an average age of 58 years. Two-thirds were men, their baseline A1c was 7.8%, and on average had 2.6 episodes of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia during the prior 2 years.

The researchers drew hourly blood specimens on a total of 196 nights from the 51 participating patients and identified 57 nights when blood glucose levels reached hypoglycemia thresholds in 33 patients. One-third of the events occurred when patients were on insulin degludec treatment, and two-thirds when they were on insulin glargine, reported Dr. Brøsen.

She presented three separate analyses of the data. One analysis focused on level 1 hypoglycemia events, when blood glucose dips to 70 mg/dL or less, which occurred 54% less often when patients were on insulin degludec. A second analysis looked at level 2 events, when blood glucose falls below 54 mg/dL, and treatment with insulin degludec cut this by 64% compared with insulin glargine. The third analysis focused on symptomatic events when blood glucose was 70 mg/dL or less, and treatment with insulin degludec linked with a 62% cut in this metric. All three between-group differences were significant.

Evidence supports already-changed practice

This new evidence “supports recommending” insulin degludec over insulin glargine, commented Bastiaan E. de Galan, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist and professor at Maastrict (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. The new results “extend those from previous trials in populations with type 1 diabetes that were unselected for the risk of hypoglycemia. In clinical practice, insulin degludec is already considered for patients who reported nocturnal hypoglycemia while on insulin glargine U100, but it’s great this study provides the scientific evidence,” said Dr. de Galan in an interview.

“The lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycemia with degludec, compared with glargine U100 is well established. Inpatient assessment of hypoglycemia with measurement of hourly plasma glucose allowed HypoDeg to provide stronger evidence than prior studies. The benefit of delgudec versus glargine U100 was significant and clinically meaningful, in hypo-prone patients who would benefit the most” by using insulin degludec, commented Gian Paolo Fadini, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Padova (Italy), and a lead investigator on the ReFLeCT study.

But insulin degludec is not a completely silver bullet. Its prolonged duration of action and stability that may in part explain why it limits hypoglycemia events can also be a drawback: “It probably offers fewer options for flexibility. Any change in dose takes at least a day or 2 to settle, which may be unfavorable in certain circumstances,” noted Dr. de Galan.

“I wouldn’t recommend insulin degludec for all patients with type 1 diabetes. It’s an individual evaluation in each patient,” said Dr. Brøsen. “We will be looking into whether some patients are better off on insulin glargine.”

Cost makes a difference

Another, potentially more consequential flaw is insulin degludec’s relative expense.

“To date, use of degludec in routine practice has been limited by its cost, compared with older basal insulins,” observed Dr. Fadini in an interview. “In several countries, including the United States, degludec is substantially more expensive than glargine.”

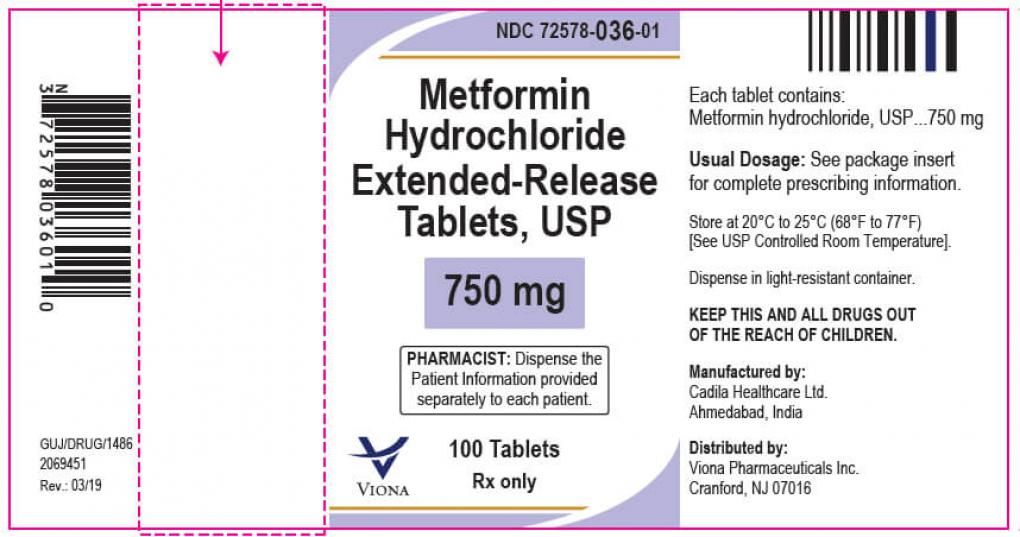

The ADA’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2021 includes table 9.3 that lists the costs of various insulins and shows the median average wholesale price of insulin glargine U100 follow-on products as $190/vial, compared with a $407 price for a similar vial of insulin degludec.

Insulin degludec “is clearly superior from a hypoglycemia standpoint. Patients with type 1 diabetes like the reduction because hypoglycemia is scary, and dangerous. The main issue is cost, and the extent to which it may be covered by insurance,” commented Lisa Chow, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “We generally won’t prescribe degludec unless it is at a price affordable to the patient. We try to use patient assistance programs sponsored by the company [that markets insulin degludec: Novo Nordisk] to try to make it more affordable.”

Dr. Chow also highlighted that a new wrinkle has been introduction of a more concentrated formulation of insulin glargine, U300, which appears to cause less hypoglycemia than insulin glargine U100. Recent study results indicated that no significant difference exists in the incidence of hypoglycemia among patients treated with insulin glargine U300 and those treated with insulin degludec, such as findings from the BRIGHT trial, which included just over 900 patients, and in the CONCLUDE trial, which randomized more than 1,600 patients.

The HypoDeg study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets insulin degludec. Dr. Brøsen had no personal disclosures, but several of her coauthors were either Novo Nordisk employees or had financial relationships with the company. Dr. de Galan has received research funding from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Fadini has received lecture fees and research funding from Novo Nordisk, from Sanofi, the company that markets insulin glargine, and from several other companies. Dr. Chow has received research funding from Dexcom.

Patients with type 1 diabetes who used insulin degludec as their basal insulin had fewer than half the number of nocturnal hypoglycemia events, compared with patients who used insulin glargine U100, in a head-to-head crossover study with 51 patients who had a history of nighttime hypoglycemia episodes.

Patients with type 1 diabetes who are “struggling with nocturnal hypoglycemia would benefit from insulin degludec treatment,” said Julie M. Brøsen, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Accumulating evidence for less hypoglycemia with insulin degludec

Results from several studies comparing insulin degludec (Tresiba), a second-generation, longer-acting insulin with more stable steady-state performance, with the first-generation basal insulin analogue glargine (Lantus), have built the case that degludec produces fewer hypoglycemia events.

The landmark SWITCH 1 crossover study published in 2017 showed in about 500 patients with type 1 diabetes and a risk factor for hypoglycemia that treatment with insulin degludec led to significantly few total hypoglycemia episodes and significantly fewer nocturnal episodes, compared with insulin glargine.

Next came similar findings from ReFLeCT, a multicenter observational study that followed 556 unselected patients with type 1 diabetes in routine practice settings who switched to insulin degludec following treatment with a different basal insulin. The results again showed a significant drop-off in total, nonsevere, severe, and nocturnal hypoglycemia events.

Homing in on higher-risk patients

The current study, HypoDeg (Insulin Degludec and Symptomatic Nocturnal Hypoglycaemia), ran at 10 Danish centers and enrolled 149 adults with type 1 diabetes who had at least one episode of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia within the prior 2 years, focusing on patients most at risk for future nocturnal hypoglycemia events. In an unusual study design, researchers identified nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes with hourly venous blood samples drawn from a subcutaneous line.

They randomized the patients to basal insulin treatment with either insulin degludec or to insulin glargine U100, allowed their treatment to stabilize for 3 months, and then tallied nocturnal hypoglycemia events for 9 months. They then crossed patients to the alternative basal insulin and repeated the process.

Results from the full study have not yet appeared in published form but were in a pair of reports at the 2020 scientific sessions of the ADA.

One report included findings based on 136 episodes of severe hypoglycemia identified clinically and showed these events occurred 35% less often during treatment with insulin degludec, a significant difference. The overall finding was primarily driven by 48% fewer episodes of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia, but this difference was not significant.

The second report identified hypoglycemia events with continuous glucose monitoring in 74 of the study participants, which identified 193 episodes of nonsevere nocturnal hypoglycemia and found that treatment with insulin degludec cut the rate by 47%, primarily by reducing asymptomatic episodes.

Hourly blood draws track overnight hypoglycemia

The current study included 51 of the 149 HypoDeg patients who agreed to undergo overnight blood sampling and had this done at least once while treated with each of the two study insulins. (The study design called for two blood sampling nights for each willing patient during each of the two treatment periods.) The 51 patients had type 1 diabetes for an average of 28 years and an average age of 58 years. Two-thirds were men, their baseline A1c was 7.8%, and on average had 2.6 episodes of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia during the prior 2 years.

The researchers drew hourly blood specimens on a total of 196 nights from the 51 participating patients and identified 57 nights when blood glucose levels reached hypoglycemia thresholds in 33 patients. One-third of the events occurred when patients were on insulin degludec treatment, and two-thirds when they were on insulin glargine, reported Dr. Brøsen.

She presented three separate analyses of the data. One analysis focused on level 1 hypoglycemia events, when blood glucose dips to 70 mg/dL or less, which occurred 54% less often when patients were on insulin degludec. A second analysis looked at level 2 events, when blood glucose falls below 54 mg/dL, and treatment with insulin degludec cut this by 64% compared with insulin glargine. The third analysis focused on symptomatic events when blood glucose was 70 mg/dL or less, and treatment with insulin degludec linked with a 62% cut in this metric. All three between-group differences were significant.

Evidence supports already-changed practice

This new evidence “supports recommending” insulin degludec over insulin glargine, commented Bastiaan E. de Galan, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist and professor at Maastrict (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. The new results “extend those from previous trials in populations with type 1 diabetes that were unselected for the risk of hypoglycemia. In clinical practice, insulin degludec is already considered for patients who reported nocturnal hypoglycemia while on insulin glargine U100, but it’s great this study provides the scientific evidence,” said Dr. de Galan in an interview.

“The lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycemia with degludec, compared with glargine U100 is well established. Inpatient assessment of hypoglycemia with measurement of hourly plasma glucose allowed HypoDeg to provide stronger evidence than prior studies. The benefit of delgudec versus glargine U100 was significant and clinically meaningful, in hypo-prone patients who would benefit the most” by using insulin degludec, commented Gian Paolo Fadini, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Padova (Italy), and a lead investigator on the ReFLeCT study.

But insulin degludec is not a completely silver bullet. Its prolonged duration of action and stability that may in part explain why it limits hypoglycemia events can also be a drawback: “It probably offers fewer options for flexibility. Any change in dose takes at least a day or 2 to settle, which may be unfavorable in certain circumstances,” noted Dr. de Galan.

“I wouldn’t recommend insulin degludec for all patients with type 1 diabetes. It’s an individual evaluation in each patient,” said Dr. Brøsen. “We will be looking into whether some patients are better off on insulin glargine.”

Cost makes a difference

Another, potentially more consequential flaw is insulin degludec’s relative expense.

“To date, use of degludec in routine practice has been limited by its cost, compared with older basal insulins,” observed Dr. Fadini in an interview. “In several countries, including the United States, degludec is substantially more expensive than glargine.”

The ADA’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2021 includes table 9.3 that lists the costs of various insulins and shows the median average wholesale price of insulin glargine U100 follow-on products as $190/vial, compared with a $407 price for a similar vial of insulin degludec.

Insulin degludec “is clearly superior from a hypoglycemia standpoint. Patients with type 1 diabetes like the reduction because hypoglycemia is scary, and dangerous. The main issue is cost, and the extent to which it may be covered by insurance,” commented Lisa Chow, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “We generally won’t prescribe degludec unless it is at a price affordable to the patient. We try to use patient assistance programs sponsored by the company [that markets insulin degludec: Novo Nordisk] to try to make it more affordable.”

Dr. Chow also highlighted that a new wrinkle has been introduction of a more concentrated formulation of insulin glargine, U300, which appears to cause less hypoglycemia than insulin glargine U100. Recent study results indicated that no significant difference exists in the incidence of hypoglycemia among patients treated with insulin glargine U300 and those treated with insulin degludec, such as findings from the BRIGHT trial, which included just over 900 patients, and in the CONCLUDE trial, which randomized more than 1,600 patients.

The HypoDeg study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets insulin degludec. Dr. Brøsen had no personal disclosures, but several of her coauthors were either Novo Nordisk employees or had financial relationships with the company. Dr. de Galan has received research funding from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Fadini has received lecture fees and research funding from Novo Nordisk, from Sanofi, the company that markets insulin glargine, and from several other companies. Dr. Chow has received research funding from Dexcom.

Patients with type 1 diabetes who used insulin degludec as their basal insulin had fewer than half the number of nocturnal hypoglycemia events, compared with patients who used insulin glargine U100, in a head-to-head crossover study with 51 patients who had a history of nighttime hypoglycemia episodes.

Patients with type 1 diabetes who are “struggling with nocturnal hypoglycemia would benefit from insulin degludec treatment,” said Julie M. Brøsen, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Accumulating evidence for less hypoglycemia with insulin degludec

Results from several studies comparing insulin degludec (Tresiba), a second-generation, longer-acting insulin with more stable steady-state performance, with the first-generation basal insulin analogue glargine (Lantus), have built the case that degludec produces fewer hypoglycemia events.

The landmark SWITCH 1 crossover study published in 2017 showed in about 500 patients with type 1 diabetes and a risk factor for hypoglycemia that treatment with insulin degludec led to significantly few total hypoglycemia episodes and significantly fewer nocturnal episodes, compared with insulin glargine.

Next came similar findings from ReFLeCT, a multicenter observational study that followed 556 unselected patients with type 1 diabetes in routine practice settings who switched to insulin degludec following treatment with a different basal insulin. The results again showed a significant drop-off in total, nonsevere, severe, and nocturnal hypoglycemia events.

Homing in on higher-risk patients

The current study, HypoDeg (Insulin Degludec and Symptomatic Nocturnal Hypoglycaemia), ran at 10 Danish centers and enrolled 149 adults with type 1 diabetes who had at least one episode of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia within the prior 2 years, focusing on patients most at risk for future nocturnal hypoglycemia events. In an unusual study design, researchers identified nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes with hourly venous blood samples drawn from a subcutaneous line.

They randomized the patients to basal insulin treatment with either insulin degludec or to insulin glargine U100, allowed their treatment to stabilize for 3 months, and then tallied nocturnal hypoglycemia events for 9 months. They then crossed patients to the alternative basal insulin and repeated the process.

Results from the full study have not yet appeared in published form but were in a pair of reports at the 2020 scientific sessions of the ADA.

One report included findings based on 136 episodes of severe hypoglycemia identified clinically and showed these events occurred 35% less often during treatment with insulin degludec, a significant difference. The overall finding was primarily driven by 48% fewer episodes of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia, but this difference was not significant.

The second report identified hypoglycemia events with continuous glucose monitoring in 74 of the study participants, which identified 193 episodes of nonsevere nocturnal hypoglycemia and found that treatment with insulin degludec cut the rate by 47%, primarily by reducing asymptomatic episodes.

Hourly blood draws track overnight hypoglycemia

The current study included 51 of the 149 HypoDeg patients who agreed to undergo overnight blood sampling and had this done at least once while treated with each of the two study insulins. (The study design called for two blood sampling nights for each willing patient during each of the two treatment periods.) The 51 patients had type 1 diabetes for an average of 28 years and an average age of 58 years. Two-thirds were men, their baseline A1c was 7.8%, and on average had 2.6 episodes of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia during the prior 2 years.

The researchers drew hourly blood specimens on a total of 196 nights from the 51 participating patients and identified 57 nights when blood glucose levels reached hypoglycemia thresholds in 33 patients. One-third of the events occurred when patients were on insulin degludec treatment, and two-thirds when they were on insulin glargine, reported Dr. Brøsen.

She presented three separate analyses of the data. One analysis focused on level 1 hypoglycemia events, when blood glucose dips to 70 mg/dL or less, which occurred 54% less often when patients were on insulin degludec. A second analysis looked at level 2 events, when blood glucose falls below 54 mg/dL, and treatment with insulin degludec cut this by 64% compared with insulin glargine. The third analysis focused on symptomatic events when blood glucose was 70 mg/dL or less, and treatment with insulin degludec linked with a 62% cut in this metric. All three between-group differences were significant.

Evidence supports already-changed practice

This new evidence “supports recommending” insulin degludec over insulin glargine, commented Bastiaan E. de Galan, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist and professor at Maastrict (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. The new results “extend those from previous trials in populations with type 1 diabetes that were unselected for the risk of hypoglycemia. In clinical practice, insulin degludec is already considered for patients who reported nocturnal hypoglycemia while on insulin glargine U100, but it’s great this study provides the scientific evidence,” said Dr. de Galan in an interview.

“The lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycemia with degludec, compared with glargine U100 is well established. Inpatient assessment of hypoglycemia with measurement of hourly plasma glucose allowed HypoDeg to provide stronger evidence than prior studies. The benefit of delgudec versus glargine U100 was significant and clinically meaningful, in hypo-prone patients who would benefit the most” by using insulin degludec, commented Gian Paolo Fadini, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Padova (Italy), and a lead investigator on the ReFLeCT study.

But insulin degludec is not a completely silver bullet. Its prolonged duration of action and stability that may in part explain why it limits hypoglycemia events can also be a drawback: “It probably offers fewer options for flexibility. Any change in dose takes at least a day or 2 to settle, which may be unfavorable in certain circumstances,” noted Dr. de Galan.

“I wouldn’t recommend insulin degludec for all patients with type 1 diabetes. It’s an individual evaluation in each patient,” said Dr. Brøsen. “We will be looking into whether some patients are better off on insulin glargine.”

Cost makes a difference

Another, potentially more consequential flaw is insulin degludec’s relative expense.

“To date, use of degludec in routine practice has been limited by its cost, compared with older basal insulins,” observed Dr. Fadini in an interview. “In several countries, including the United States, degludec is substantially more expensive than glargine.”

The ADA’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2021 includes table 9.3 that lists the costs of various insulins and shows the median average wholesale price of insulin glargine U100 follow-on products as $190/vial, compared with a $407 price for a similar vial of insulin degludec.

Insulin degludec “is clearly superior from a hypoglycemia standpoint. Patients with type 1 diabetes like the reduction because hypoglycemia is scary, and dangerous. The main issue is cost, and the extent to which it may be covered by insurance,” commented Lisa Chow, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “We generally won’t prescribe degludec unless it is at a price affordable to the patient. We try to use patient assistance programs sponsored by the company [that markets insulin degludec: Novo Nordisk] to try to make it more affordable.”

Dr. Chow also highlighted that a new wrinkle has been introduction of a more concentrated formulation of insulin glargine, U300, which appears to cause less hypoglycemia than insulin glargine U100. Recent study results indicated that no significant difference exists in the incidence of hypoglycemia among patients treated with insulin glargine U300 and those treated with insulin degludec, such as findings from the BRIGHT trial, which included just over 900 patients, and in the CONCLUDE trial, which randomized more than 1,600 patients.

The HypoDeg study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets insulin degludec. Dr. Brøsen had no personal disclosures, but several of her coauthors were either Novo Nordisk employees or had financial relationships with the company. Dr. de Galan has received research funding from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Fadini has received lecture fees and research funding from Novo Nordisk, from Sanofi, the company that markets insulin glargine, and from several other companies. Dr. Chow has received research funding from Dexcom.

FROM ADA 2021

SUSTAIN FORTE: Higher-dose semaglutide safely boosts glycemic control, weight loss

Accumulating evidence shows that

Just weeks after the Food and Drug Administration approved an increased, 2.4-mg/week dose of semaglutide (Wegovy) for the indication of weight loss, results from a new randomized study with 961 patients that directly compared the standard 1.0-mg weekly dose for glycemic control with a 2.0-mg weekly dose showed that, over 40 weeks, the higher dose produced modest incremental improvements in both A1c reduction and weight loss while maintaining safety.

“Once weekly 2.0-mg subcutaneous semaglutide [Ozempic] was superior to 1.0 mg in reducing A1c, with greater weight loss and a similar safety profile,” Juan P. Frias, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association while presenting results of the SUSTAIN FORTE trial.

Average impact of the increased efficacy was measured. In the study’s “treatment policy estimand” analysis (considered equivalent to an intention-to-treat analysis), the primary endpoint of the cut in average A1c fell by a further 0.18% among patients on the higher dose, compared with the lower-dose arm, a significant difference in patients who entered the study with an average A1c of 8.9%. The average incremental boost for weight loss on the higher dose was about 0.8 kg, a difference that just missed significance (P = .0535).

In the study’s “trial product estimand” analysis (which censors data when patients stop the study drug or add on rescue medications), the effects were slightly more robust. The 2-mg dose produced an average 0.23% incremental decrease in A1c, compared with 1 mg, and an average incremental 0.93-kg weight reduction, both significant, reported Dr. Frias, an endocrinologist and medical director of the National Research Institute in Los Angeles.

Dr. Frias highlighted that these modest average differences had a clinical impact for some patients. In the treatment product estimand analysis, the percentage of patients achieving an A1c level of less than 7.0% increased from 58% of those who received 1 mg semaglutide to 68% of those treated with 2 mg, and achievement of an A1c of less than 6.5% occurred in 39% of patients on 1 mg and in 52% of those on 2 mg.

A similar pattern existed for weight loss in the treatment product estimand. Weight loss of at least 5% happened in 51% of patients on the 1-mg dose and in 59% of those on the higher dose.

Gradual up-titration aids tolerance

“The GLP-1 receptor agonists have so many benefits, but we were concerned in the past about pushing the dose. We’ve learned more about how to do that so that patients can better tolerate it,” commented Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medicine officer of the ADA in Arlington, Va. “The challenge with the medications from this class has been tolerability.”

A key to minimizing adverse effects, especially gastrointestinal effects, from treatment with semaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists has been more gradual up-titration to the target dose, Dr. Gabbay noted in an interview, and SUSTAIN FORTE took this approach. All patients started on a 0.25-mg injection of semaglutide once weekly for the first 4 weeks, followed by a 0.5-mg dose once weekly for 4 weeks, and then a 1.0 mg weekly dose. Patients in the arm randomized to receive 2.0 mg had one further dose escalation after receiving the 1.0-mg dose for 4 weeks.

The result was that gastrointestinal adverse effects occurred in 31% of patients maintained for 32 weeks on the 1-mg dose (with 40 total weeks of semaglutide treatment), and in 34% of patients who received the 2-mg dose for 28 weeks (and 40 total weeks of semaglutide treatment). Serious adverse events of all types occurred in 5% of patients in the 1-mg arm and in 4% of those on 2 mg. Total adverse events resulting in treatment discontinuation occurred in about 4.5% of patients in both arms, and discontinuations because of gastrointestinal effects occurred in about 3% of patients in both arms.

Severe hypoglycemia episodes occurred in 1 patient maintained on 1 mg weekly and in 2 patients in the 2-mg arm, while clinically significant episodes of hypoglycemia occurred in 18 patients on the 1-mg dose (4%) and in 12 of the patients on 2 mg (3%).

“It’s reassuring that the higher dose is tolerated,” commented Dr. Gabbay.

Several doses to choose from

SUSTAIN FORTE ran during 2019-2020 at about 125 centers in 10 countries, with roughly half the sites in the United States. It randomized adults with type 2 diabetes and an A1c of 8.0%-10.0% despite ongoing metformin treatment in all patients. Just over half the patients were also maintained on a sulfonylurea agent at entry. The enrolled patients had been diagnosed with diabetes for an average of about 10 years. They averaged 58 years of age, their body mass index averaged nearly 35 kg/m2, and about 58% were men.

The new evidence in support of a 2.0-mg weekly dose of semaglutide for patients with type 2 diabetes introduces a new wrinkle in a growing menu of dose options for this drug. On June 4, 2021, the FDA approved a weekly 2.4-mg dose of semaglutide for the indication of weight loss regardless of diabetes status in patients with a body mass index of 30 or higher (or in people at 27 or more with at least one weight-related comorbidity).

Dr. Gabbay suggested that, in practice, clinicians may focus more on treatment goals for individual patients rather than drug dose, especially with an agent that’s safer with slow dose titration.

In general, “clinicians establish a goal for each patient’s A1c; you use the drug dose that gets you there,” he observed.

SUSTAIN FORTE was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets semaglutide. Dr. Frias has been a consultant to Novo Nordisk and numerous other companies, he has been a speaker on behalf of Lilly, Merck, and Sanofi, and he has received research funding from Novo Nordisk and numerous other companies. Dr. Gabbay had no relevant disclosures.

Accumulating evidence shows that

Just weeks after the Food and Drug Administration approved an increased, 2.4-mg/week dose of semaglutide (Wegovy) for the indication of weight loss, results from a new randomized study with 961 patients that directly compared the standard 1.0-mg weekly dose for glycemic control with a 2.0-mg weekly dose showed that, over 40 weeks, the higher dose produced modest incremental improvements in both A1c reduction and weight loss while maintaining safety.

“Once weekly 2.0-mg subcutaneous semaglutide [Ozempic] was superior to 1.0 mg in reducing A1c, with greater weight loss and a similar safety profile,” Juan P. Frias, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association while presenting results of the SUSTAIN FORTE trial.

Average impact of the increased efficacy was measured. In the study’s “treatment policy estimand” analysis (considered equivalent to an intention-to-treat analysis), the primary endpoint of the cut in average A1c fell by a further 0.18% among patients on the higher dose, compared with the lower-dose arm, a significant difference in patients who entered the study with an average A1c of 8.9%. The average incremental boost for weight loss on the higher dose was about 0.8 kg, a difference that just missed significance (P = .0535).

In the study’s “trial product estimand” analysis (which censors data when patients stop the study drug or add on rescue medications), the effects were slightly more robust. The 2-mg dose produced an average 0.23% incremental decrease in A1c, compared with 1 mg, and an average incremental 0.93-kg weight reduction, both significant, reported Dr. Frias, an endocrinologist and medical director of the National Research Institute in Los Angeles.

Dr. Frias highlighted that these modest average differences had a clinical impact for some patients. In the treatment product estimand analysis, the percentage of patients achieving an A1c level of less than 7.0% increased from 58% of those who received 1 mg semaglutide to 68% of those treated with 2 mg, and achievement of an A1c of less than 6.5% occurred in 39% of patients on 1 mg and in 52% of those on 2 mg.

A similar pattern existed for weight loss in the treatment product estimand. Weight loss of at least 5% happened in 51% of patients on the 1-mg dose and in 59% of those on the higher dose.

Gradual up-titration aids tolerance

“The GLP-1 receptor agonists have so many benefits, but we were concerned in the past about pushing the dose. We’ve learned more about how to do that so that patients can better tolerate it,” commented Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medicine officer of the ADA in Arlington, Va. “The challenge with the medications from this class has been tolerability.”

A key to minimizing adverse effects, especially gastrointestinal effects, from treatment with semaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists has been more gradual up-titration to the target dose, Dr. Gabbay noted in an interview, and SUSTAIN FORTE took this approach. All patients started on a 0.25-mg injection of semaglutide once weekly for the first 4 weeks, followed by a 0.5-mg dose once weekly for 4 weeks, and then a 1.0 mg weekly dose. Patients in the arm randomized to receive 2.0 mg had one further dose escalation after receiving the 1.0-mg dose for 4 weeks.

The result was that gastrointestinal adverse effects occurred in 31% of patients maintained for 32 weeks on the 1-mg dose (with 40 total weeks of semaglutide treatment), and in 34% of patients who received the 2-mg dose for 28 weeks (and 40 total weeks of semaglutide treatment). Serious adverse events of all types occurred in 5% of patients in the 1-mg arm and in 4% of those on 2 mg. Total adverse events resulting in treatment discontinuation occurred in about 4.5% of patients in both arms, and discontinuations because of gastrointestinal effects occurred in about 3% of patients in both arms.

Severe hypoglycemia episodes occurred in 1 patient maintained on 1 mg weekly and in 2 patients in the 2-mg arm, while clinically significant episodes of hypoglycemia occurred in 18 patients on the 1-mg dose (4%) and in 12 of the patients on 2 mg (3%).

“It’s reassuring that the higher dose is tolerated,” commented Dr. Gabbay.

Several doses to choose from

SUSTAIN FORTE ran during 2019-2020 at about 125 centers in 10 countries, with roughly half the sites in the United States. It randomized adults with type 2 diabetes and an A1c of 8.0%-10.0% despite ongoing metformin treatment in all patients. Just over half the patients were also maintained on a sulfonylurea agent at entry. The enrolled patients had been diagnosed with diabetes for an average of about 10 years. They averaged 58 years of age, their body mass index averaged nearly 35 kg/m2, and about 58% were men.

The new evidence in support of a 2.0-mg weekly dose of semaglutide for patients with type 2 diabetes introduces a new wrinkle in a growing menu of dose options for this drug. On June 4, 2021, the FDA approved a weekly 2.4-mg dose of semaglutide for the indication of weight loss regardless of diabetes status in patients with a body mass index of 30 or higher (or in people at 27 or more with at least one weight-related comorbidity).

Dr. Gabbay suggested that, in practice, clinicians may focus more on treatment goals for individual patients rather than drug dose, especially with an agent that’s safer with slow dose titration.

In general, “clinicians establish a goal for each patient’s A1c; you use the drug dose that gets you there,” he observed.

SUSTAIN FORTE was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets semaglutide. Dr. Frias has been a consultant to Novo Nordisk and numerous other companies, he has been a speaker on behalf of Lilly, Merck, and Sanofi, and he has received research funding from Novo Nordisk and numerous other companies. Dr. Gabbay had no relevant disclosures.

Accumulating evidence shows that

Just weeks after the Food and Drug Administration approved an increased, 2.4-mg/week dose of semaglutide (Wegovy) for the indication of weight loss, results from a new randomized study with 961 patients that directly compared the standard 1.0-mg weekly dose for glycemic control with a 2.0-mg weekly dose showed that, over 40 weeks, the higher dose produced modest incremental improvements in both A1c reduction and weight loss while maintaining safety.

“Once weekly 2.0-mg subcutaneous semaglutide [Ozempic] was superior to 1.0 mg in reducing A1c, with greater weight loss and a similar safety profile,” Juan P. Frias, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association while presenting results of the SUSTAIN FORTE trial.

Average impact of the increased efficacy was measured. In the study’s “treatment policy estimand” analysis (considered equivalent to an intention-to-treat analysis), the primary endpoint of the cut in average A1c fell by a further 0.18% among patients on the higher dose, compared with the lower-dose arm, a significant difference in patients who entered the study with an average A1c of 8.9%. The average incremental boost for weight loss on the higher dose was about 0.8 kg, a difference that just missed significance (P = .0535).

In the study’s “trial product estimand” analysis (which censors data when patients stop the study drug or add on rescue medications), the effects were slightly more robust. The 2-mg dose produced an average 0.23% incremental decrease in A1c, compared with 1 mg, and an average incremental 0.93-kg weight reduction, both significant, reported Dr. Frias, an endocrinologist and medical director of the National Research Institute in Los Angeles.

Dr. Frias highlighted that these modest average differences had a clinical impact for some patients. In the treatment product estimand analysis, the percentage of patients achieving an A1c level of less than 7.0% increased from 58% of those who received 1 mg semaglutide to 68% of those treated with 2 mg, and achievement of an A1c of less than 6.5% occurred in 39% of patients on 1 mg and in 52% of those on 2 mg.

A similar pattern existed for weight loss in the treatment product estimand. Weight loss of at least 5% happened in 51% of patients on the 1-mg dose and in 59% of those on the higher dose.

Gradual up-titration aids tolerance

“The GLP-1 receptor agonists have so many benefits, but we were concerned in the past about pushing the dose. We’ve learned more about how to do that so that patients can better tolerate it,” commented Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medicine officer of the ADA in Arlington, Va. “The challenge with the medications from this class has been tolerability.”

A key to minimizing adverse effects, especially gastrointestinal effects, from treatment with semaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists has been more gradual up-titration to the target dose, Dr. Gabbay noted in an interview, and SUSTAIN FORTE took this approach. All patients started on a 0.25-mg injection of semaglutide once weekly for the first 4 weeks, followed by a 0.5-mg dose once weekly for 4 weeks, and then a 1.0 mg weekly dose. Patients in the arm randomized to receive 2.0 mg had one further dose escalation after receiving the 1.0-mg dose for 4 weeks.

The result was that gastrointestinal adverse effects occurred in 31% of patients maintained for 32 weeks on the 1-mg dose (with 40 total weeks of semaglutide treatment), and in 34% of patients who received the 2-mg dose for 28 weeks (and 40 total weeks of semaglutide treatment). Serious adverse events of all types occurred in 5% of patients in the 1-mg arm and in 4% of those on 2 mg. Total adverse events resulting in treatment discontinuation occurred in about 4.5% of patients in both arms, and discontinuations because of gastrointestinal effects occurred in about 3% of patients in both arms.

Severe hypoglycemia episodes occurred in 1 patient maintained on 1 mg weekly and in 2 patients in the 2-mg arm, while clinically significant episodes of hypoglycemia occurred in 18 patients on the 1-mg dose (4%) and in 12 of the patients on 2 mg (3%).

“It’s reassuring that the higher dose is tolerated,” commented Dr. Gabbay.

Several doses to choose from

SUSTAIN FORTE ran during 2019-2020 at about 125 centers in 10 countries, with roughly half the sites in the United States. It randomized adults with type 2 diabetes and an A1c of 8.0%-10.0% despite ongoing metformin treatment in all patients. Just over half the patients were also maintained on a sulfonylurea agent at entry. The enrolled patients had been diagnosed with diabetes for an average of about 10 years. They averaged 58 years of age, their body mass index averaged nearly 35 kg/m2, and about 58% were men.

The new evidence in support of a 2.0-mg weekly dose of semaglutide for patients with type 2 diabetes introduces a new wrinkle in a growing menu of dose options for this drug. On June 4, 2021, the FDA approved a weekly 2.4-mg dose of semaglutide for the indication of weight loss regardless of diabetes status in patients with a body mass index of 30 or higher (or in people at 27 or more with at least one weight-related comorbidity).

Dr. Gabbay suggested that, in practice, clinicians may focus more on treatment goals for individual patients rather than drug dose, especially with an agent that’s safer with slow dose titration.

In general, “clinicians establish a goal for each patient’s A1c; you use the drug dose that gets you there,” he observed.

SUSTAIN FORTE was sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets semaglutide. Dr. Frias has been a consultant to Novo Nordisk and numerous other companies, he has been a speaker on behalf of Lilly, Merck, and Sanofi, and he has received research funding from Novo Nordisk and numerous other companies. Dr. Gabbay had no relevant disclosures.

FROM ADA 2021

Unmanaged diabetes, high blood glucose tied to COVID-19 severity

Unmanaged diabetes and high blood glucose levels are linked to more severe COVID-19 and worse rates of recovery, according to results of a retrospective study.

Patients not managing their diabetes with medication had more severe COVID-19 and length of hospitalization, compared with those who were taking medication, investigator Sudip Bajpeyi, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In addition, patients with higher blood glucose levels had more severe COVID-19 and longer hospital stays.

Those findings underscore the need to assess, monitor, and control blood glucose, especially in vulnerable populations, said Dr. Bajpeyi, director of the Metabolic, Nutrition, and Exercise Research Laboratory in the University of Texas, El Paso, who added that nearly 90% of the study subjects were Hispanic.

“As public health decisions are made, we think fasting blood glucose should be considered in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” he said in a press conference.

Links between diabetes and COVID-19

There are now many reports in medical literature that link diabetes to increased risk of COVID-19 severity, according to Ali Mossayebi, a master’s student who worked on the study. However, there are fewer studies that have looked specifically at the implications of poor diabetes management or acute glycemic control, the investigators said.

It’s known that poorly controlled diabetes can have severe health consequences, including higher risks for life-threatening comorbidities, they added.

Their retrospective study focused on medical records from 364 patients with COVID-19 admitted to a medical center in El Paso. Their mean age was 60 years, and their mean body mass index was 30.3 kg/m2; 87% were Hispanic.

Acute glycemic control was assessed by fasting blood glucose at the time of hospitalization, while chronic glycemic control was assessed by hemoglobin A1c, the investigators said. Severity of COVID-19 was measured with the Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA), which is based on the patient’s respiratory rate, blood pressure, and mental status.

Impact of unmanaged diabetes and high blood glucose

Severity of COVID-19 severity and length of hospital stay were significantly greater in patients with unmanaged diabetes, as compared with those who reported that they managed their diabetes with medication, Dr. Bajpeyi and coinvestigators found.

Among patients with unmanaged diabetes, the mean qSOFA score was 0.22, as compared with 0.44 for patients with managed diabetes. The mean length of hospital stay was 10.8 days for patients with unmanaged diabetes and 8.2 days for those with medication-managed diabetes, according to the abstract.

COVID-19 severity and hospital stay length were highest among patients with acute glycemia, the investigators further reported in an electronic poster that was part of the ADA meeting proceedings.

The mean qSOFA score was about 0.6 for patients with blood glucose levels of at least 126 mg/dL and A1c below 6.5%, and roughly 0.2 for those with normal blood glucose and normal A1c. Similarly, duration of hospital stay was significantly higher for patients with high blood glucose and A1c as compared with those with normal blood glucose and A1c.

Aggressive treatment needed

Findings of this study are in line with previous research showing that in-hospital hyperglycemia is a common and important marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality, with or without diabetes, according to Rodolfo J. Galindo, MD, FACE, medical chair of the hospital diabetes task force at Emory Healthcare System, Atlanta.

“These patients need aggressive treatment of hyperglycemia, regardless of the diagnosis of diabetes or A1c value,” said Dr. Galindo, who was not involved in the study. “They also need outpatient follow-up after discharge, because they may develop diabetes soon after.”

Follow-up within is important because roughly 30% of patients with stress hyperglycemia (increases in blood glucose during an acute illness) will develop diabetes within a year, according to Dr. Galindo.

“We do not know in COVID-10 patients if it is only 30%,” he said, “Our thinking in our group is that it’s probably higher.”

Dr. Bajpeyi and coauthors reported no disclosures. Dr. Galindo reported disclosures related to Abbott Diabetes, Boehringer Ingelheim International, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi US, Valeritas, and Dexcom.

Unmanaged diabetes and high blood glucose levels are linked to more severe COVID-19 and worse rates of recovery, according to results of a retrospective study.

Patients not managing their diabetes with medication had more severe COVID-19 and length of hospitalization, compared with those who were taking medication, investigator Sudip Bajpeyi, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In addition, patients with higher blood glucose levels had more severe COVID-19 and longer hospital stays.

Those findings underscore the need to assess, monitor, and control blood glucose, especially in vulnerable populations, said Dr. Bajpeyi, director of the Metabolic, Nutrition, and Exercise Research Laboratory in the University of Texas, El Paso, who added that nearly 90% of the study subjects were Hispanic.

“As public health decisions are made, we think fasting blood glucose should be considered in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” he said in a press conference.

Links between diabetes and COVID-19

There are now many reports in medical literature that link diabetes to increased risk of COVID-19 severity, according to Ali Mossayebi, a master’s student who worked on the study. However, there are fewer studies that have looked specifically at the implications of poor diabetes management or acute glycemic control, the investigators said.

It’s known that poorly controlled diabetes can have severe health consequences, including higher risks for life-threatening comorbidities, they added.

Their retrospective study focused on medical records from 364 patients with COVID-19 admitted to a medical center in El Paso. Their mean age was 60 years, and their mean body mass index was 30.3 kg/m2; 87% were Hispanic.

Acute glycemic control was assessed by fasting blood glucose at the time of hospitalization, while chronic glycemic control was assessed by hemoglobin A1c, the investigators said. Severity of COVID-19 was measured with the Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA), which is based on the patient’s respiratory rate, blood pressure, and mental status.

Impact of unmanaged diabetes and high blood glucose

Severity of COVID-19 severity and length of hospital stay were significantly greater in patients with unmanaged diabetes, as compared with those who reported that they managed their diabetes with medication, Dr. Bajpeyi and coinvestigators found.

Among patients with unmanaged diabetes, the mean qSOFA score was 0.22, as compared with 0.44 for patients with managed diabetes. The mean length of hospital stay was 10.8 days for patients with unmanaged diabetes and 8.2 days for those with medication-managed diabetes, according to the abstract.

COVID-19 severity and hospital stay length were highest among patients with acute glycemia, the investigators further reported in an electronic poster that was part of the ADA meeting proceedings.

The mean qSOFA score was about 0.6 for patients with blood glucose levels of at least 126 mg/dL and A1c below 6.5%, and roughly 0.2 for those with normal blood glucose and normal A1c. Similarly, duration of hospital stay was significantly higher for patients with high blood glucose and A1c as compared with those with normal blood glucose and A1c.

Aggressive treatment needed

Findings of this study are in line with previous research showing that in-hospital hyperglycemia is a common and important marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality, with or without diabetes, according to Rodolfo J. Galindo, MD, FACE, medical chair of the hospital diabetes task force at Emory Healthcare System, Atlanta.

“These patients need aggressive treatment of hyperglycemia, regardless of the diagnosis of diabetes or A1c value,” said Dr. Galindo, who was not involved in the study. “They also need outpatient follow-up after discharge, because they may develop diabetes soon after.”

Follow-up within is important because roughly 30% of patients with stress hyperglycemia (increases in blood glucose during an acute illness) will develop diabetes within a year, according to Dr. Galindo.

“We do not know in COVID-10 patients if it is only 30%,” he said, “Our thinking in our group is that it’s probably higher.”

Dr. Bajpeyi and coauthors reported no disclosures. Dr. Galindo reported disclosures related to Abbott Diabetes, Boehringer Ingelheim International, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi US, Valeritas, and Dexcom.

Unmanaged diabetes and high blood glucose levels are linked to more severe COVID-19 and worse rates of recovery, according to results of a retrospective study.

Patients not managing their diabetes with medication had more severe COVID-19 and length of hospitalization, compared with those who were taking medication, investigator Sudip Bajpeyi, PhD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In addition, patients with higher blood glucose levels had more severe COVID-19 and longer hospital stays.

Those findings underscore the need to assess, monitor, and control blood glucose, especially in vulnerable populations, said Dr. Bajpeyi, director of the Metabolic, Nutrition, and Exercise Research Laboratory in the University of Texas, El Paso, who added that nearly 90% of the study subjects were Hispanic.

“As public health decisions are made, we think fasting blood glucose should be considered in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” he said in a press conference.

Links between diabetes and COVID-19

There are now many reports in medical literature that link diabetes to increased risk of COVID-19 severity, according to Ali Mossayebi, a master’s student who worked on the study. However, there are fewer studies that have looked specifically at the implications of poor diabetes management or acute glycemic control, the investigators said.

It’s known that poorly controlled diabetes can have severe health consequences, including higher risks for life-threatening comorbidities, they added.

Their retrospective study focused on medical records from 364 patients with COVID-19 admitted to a medical center in El Paso. Their mean age was 60 years, and their mean body mass index was 30.3 kg/m2; 87% were Hispanic.

Acute glycemic control was assessed by fasting blood glucose at the time of hospitalization, while chronic glycemic control was assessed by hemoglobin A1c, the investigators said. Severity of COVID-19 was measured with the Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA), which is based on the patient’s respiratory rate, blood pressure, and mental status.

Impact of unmanaged diabetes and high blood glucose

Severity of COVID-19 severity and length of hospital stay were significantly greater in patients with unmanaged diabetes, as compared with those who reported that they managed their diabetes with medication, Dr. Bajpeyi and coinvestigators found.

Among patients with unmanaged diabetes, the mean qSOFA score was 0.22, as compared with 0.44 for patients with managed diabetes. The mean length of hospital stay was 10.8 days for patients with unmanaged diabetes and 8.2 days for those with medication-managed diabetes, according to the abstract.

COVID-19 severity and hospital stay length were highest among patients with acute glycemia, the investigators further reported in an electronic poster that was part of the ADA meeting proceedings.

The mean qSOFA score was about 0.6 for patients with blood glucose levels of at least 126 mg/dL and A1c below 6.5%, and roughly 0.2 for those with normal blood glucose and normal A1c. Similarly, duration of hospital stay was significantly higher for patients with high blood glucose and A1c as compared with those with normal blood glucose and A1c.

Aggressive treatment needed

Findings of this study are in line with previous research showing that in-hospital hyperglycemia is a common and important marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality, with or without diabetes, according to Rodolfo J. Galindo, MD, FACE, medical chair of the hospital diabetes task force at Emory Healthcare System, Atlanta.

“These patients need aggressive treatment of hyperglycemia, regardless of the diagnosis of diabetes or A1c value,” said Dr. Galindo, who was not involved in the study. “They also need outpatient follow-up after discharge, because they may develop diabetes soon after.”

Follow-up within is important because roughly 30% of patients with stress hyperglycemia (increases in blood glucose during an acute illness) will develop diabetes within a year, according to Dr. Galindo.

“We do not know in COVID-10 patients if it is only 30%,” he said, “Our thinking in our group is that it’s probably higher.”

Dr. Bajpeyi and coauthors reported no disclosures. Dr. Galindo reported disclosures related to Abbott Diabetes, Boehringer Ingelheim International, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi US, Valeritas, and Dexcom.

FROM ADA 2020

Sotagliflozin use in T2D patients linked with posthospitalization benefits in analysis

The outcome measure –days alive and out of the hospital – may be a meaningful, patient-centered way of capturing disease burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The question was: Can we keep patients alive and out of the hospital for any reason, accounting for the duration of each hospitalization?” author Michael Szarek, PhD, a visiting professor in the division of cardiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

“For every 100 days of follow-up, patients in the sotagliflozin group were alive and out of the hospital 3% more days in relative terms or 2.9 days in absolute terms than those in the placebo group (91.8 vs. 88.9 days),” the researchers reported in their analysis of data from the SOLOIST-WHF trial.

“If you translate that to over the course of a year, that’s more than 10 days,” said Dr. Szarek, who is also a faculty member of CPC Clinical Research, an academic research organization affiliated with the University of Colorado.

Most patients in both groups survived to the end of the study without hospitalization, according to the paper.

Sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and SGLT2 inhibitor, is not approved in the United States. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration rejected sotagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes after members of an advisory committee expressed concerns about an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis with the drug.

Methods and results

To examine whether sotagliflozin increased days alive and out of the hospital in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, Dr. Szarek and colleagues analyzed data from this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The trial’s primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2021. Researchers conducted SOLOIST-WHF at more than 300 sites in 32 countries. The trial included 1,222 patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced or preserved ejection fraction who were recently hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

In the new analysis the researchers looked at hospitalizations for any reason and the duration of hospital admissions after randomization. They analyzed days alive and out of the hospital using prespecified models.

Similar proportions of patients who received sotagliflozin and placebo were hospitalized at least once (38.5% vs. 41.4%) during a median follow-up of 9 months. Fewer patients who received sotagliflozin were hospitalized more than once (16.3% vs. 22.1%). In all, 64 patients in the sotagliflozin group and 76 patients in the placebo group died.

The reason for each hospitalization was unspecified, except for cases of heart failure, the authors noted. About 62% of hospitalizations during the trial were for reasons other than heart failure.

Outside expert cites similarities to initial trial

The results for days alive and out of the hospital are “not particularly surprising given the previous publication” of the trial’s primary results, but the new analysis provides a “different view of outcomes that might be clinically meaningful for patients,” commented Frank Brosius, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The SOLOIST-WHF trial indicated that doctors may be able to effectively treat patients with relatively new heart failure with sotagliflozin as long as patients are relatively stable, said Dr. Brosius, who coauthored an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the initial results from the SOLOIST-WHF trial. It appears that previously reported benefits with regard to heart failure outcomes “showed up in these other indicators” in the secondary analysis.

Still, the effect sizes in the new analysis were relatively small and “probably more studies will be necessary” to examine these end points, he added.

SOLOIST-WHF was funded by Sanofi at initiation and by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals at completion. Dr. Szarek disclosed grants from Lexicon and grants and personal fees from Sanofi, as well as personal fees from other companies. His coauthors included employees of Lexicon and other researchers with financial ties to Lexicon and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Brosius disclosed personal fees from the American Diabetes Association and is a member of the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative task force for the American Society of Nephrology that is broadly advocating the use of SGLT2 inhibitors by patients with diabetic kidney diseases. He also has participated in an advisory group for treatment of diabetic kidney disease for Gilead.

The outcome measure –days alive and out of the hospital – may be a meaningful, patient-centered way of capturing disease burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The question was: Can we keep patients alive and out of the hospital for any reason, accounting for the duration of each hospitalization?” author Michael Szarek, PhD, a visiting professor in the division of cardiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

“For every 100 days of follow-up, patients in the sotagliflozin group were alive and out of the hospital 3% more days in relative terms or 2.9 days in absolute terms than those in the placebo group (91.8 vs. 88.9 days),” the researchers reported in their analysis of data from the SOLOIST-WHF trial.

“If you translate that to over the course of a year, that’s more than 10 days,” said Dr. Szarek, who is also a faculty member of CPC Clinical Research, an academic research organization affiliated with the University of Colorado.

Most patients in both groups survived to the end of the study without hospitalization, according to the paper.

Sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and SGLT2 inhibitor, is not approved in the United States. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration rejected sotagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes after members of an advisory committee expressed concerns about an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis with the drug.

Methods and results

To examine whether sotagliflozin increased days alive and out of the hospital in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, Dr. Szarek and colleagues analyzed data from this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The trial’s primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2021. Researchers conducted SOLOIST-WHF at more than 300 sites in 32 countries. The trial included 1,222 patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced or preserved ejection fraction who were recently hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

In the new analysis the researchers looked at hospitalizations for any reason and the duration of hospital admissions after randomization. They analyzed days alive and out of the hospital using prespecified models.

Similar proportions of patients who received sotagliflozin and placebo were hospitalized at least once (38.5% vs. 41.4%) during a median follow-up of 9 months. Fewer patients who received sotagliflozin were hospitalized more than once (16.3% vs. 22.1%). In all, 64 patients in the sotagliflozin group and 76 patients in the placebo group died.

The reason for each hospitalization was unspecified, except for cases of heart failure, the authors noted. About 62% of hospitalizations during the trial were for reasons other than heart failure.

Outside expert cites similarities to initial trial

The results for days alive and out of the hospital are “not particularly surprising given the previous publication” of the trial’s primary results, but the new analysis provides a “different view of outcomes that might be clinically meaningful for patients,” commented Frank Brosius, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The SOLOIST-WHF trial indicated that doctors may be able to effectively treat patients with relatively new heart failure with sotagliflozin as long as patients are relatively stable, said Dr. Brosius, who coauthored an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the initial results from the SOLOIST-WHF trial. It appears that previously reported benefits with regard to heart failure outcomes “showed up in these other indicators” in the secondary analysis.

Still, the effect sizes in the new analysis were relatively small and “probably more studies will be necessary” to examine these end points, he added.

SOLOIST-WHF was funded by Sanofi at initiation and by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals at completion. Dr. Szarek disclosed grants from Lexicon and grants and personal fees from Sanofi, as well as personal fees from other companies. His coauthors included employees of Lexicon and other researchers with financial ties to Lexicon and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Brosius disclosed personal fees from the American Diabetes Association and is a member of the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative task force for the American Society of Nephrology that is broadly advocating the use of SGLT2 inhibitors by patients with diabetic kidney diseases. He also has participated in an advisory group for treatment of diabetic kidney disease for Gilead.

The outcome measure –days alive and out of the hospital – may be a meaningful, patient-centered way of capturing disease burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The question was: Can we keep patients alive and out of the hospital for any reason, accounting for the duration of each hospitalization?” author Michael Szarek, PhD, a visiting professor in the division of cardiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

“For every 100 days of follow-up, patients in the sotagliflozin group were alive and out of the hospital 3% more days in relative terms or 2.9 days in absolute terms than those in the placebo group (91.8 vs. 88.9 days),” the researchers reported in their analysis of data from the SOLOIST-WHF trial.

“If you translate that to over the course of a year, that’s more than 10 days,” said Dr. Szarek, who is also a faculty member of CPC Clinical Research, an academic research organization affiliated with the University of Colorado.

Most patients in both groups survived to the end of the study without hospitalization, according to the paper.

Sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and SGLT2 inhibitor, is not approved in the United States. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration rejected sotagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes after members of an advisory committee expressed concerns about an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis with the drug.

Methods and results

To examine whether sotagliflozin increased days alive and out of the hospital in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, Dr. Szarek and colleagues analyzed data from this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The trial’s primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2021. Researchers conducted SOLOIST-WHF at more than 300 sites in 32 countries. The trial included 1,222 patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced or preserved ejection fraction who were recently hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

In the new analysis the researchers looked at hospitalizations for any reason and the duration of hospital admissions after randomization. They analyzed days alive and out of the hospital using prespecified models.

Similar proportions of patients who received sotagliflozin and placebo were hospitalized at least once (38.5% vs. 41.4%) during a median follow-up of 9 months. Fewer patients who received sotagliflozin were hospitalized more than once (16.3% vs. 22.1%). In all, 64 patients in the sotagliflozin group and 76 patients in the placebo group died.

The reason for each hospitalization was unspecified, except for cases of heart failure, the authors noted. About 62% of hospitalizations during the trial were for reasons other than heart failure.

Outside expert cites similarities to initial trial

The results for days alive and out of the hospital are “not particularly surprising given the previous publication” of the trial’s primary results, but the new analysis provides a “different view of outcomes that might be clinically meaningful for patients,” commented Frank Brosius, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The SOLOIST-WHF trial indicated that doctors may be able to effectively treat patients with relatively new heart failure with sotagliflozin as long as patients are relatively stable, said Dr. Brosius, who coauthored an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the initial results from the SOLOIST-WHF trial. It appears that previously reported benefits with regard to heart failure outcomes “showed up in these other indicators” in the secondary analysis.

Still, the effect sizes in the new analysis were relatively small and “probably more studies will be necessary” to examine these end points, he added.

SOLOIST-WHF was funded by Sanofi at initiation and by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals at completion. Dr. Szarek disclosed grants from Lexicon and grants and personal fees from Sanofi, as well as personal fees from other companies. His coauthors included employees of Lexicon and other researchers with financial ties to Lexicon and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Brosius disclosed personal fees from the American Diabetes Association and is a member of the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative task force for the American Society of Nephrology that is broadly advocating the use of SGLT2 inhibitors by patients with diabetic kidney diseases. He also has participated in an advisory group for treatment of diabetic kidney disease for Gilead.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

What’s behind brain fog in treated hypothyroidism?

The phenomenon of brain fog, as described by some patients with hypothyroidism despite treatment, is often associated with fatigue and cognitive symptoms and may be relieved by a variety of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches, new research suggests.

The findings come from a survey of more than 700 patients with hypothyroidism due to thyroid surgery and/or radioactive iodine therapy (RAI) or Hashimoto’s who reported having brain fog.

The survey results were presented May 29 at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Virtual Annual Meeting 2021 by investigators Matthew D. Ettleson, MD, and Ava Raine, of the University of Chicago, Illinois.

Many patients with hypothyroidism continue to experience symptoms despite taking thyroid hormone replacement therapy and having normal thyroid function test results.

These symptoms can include quantifiable cognitive, quality of life, and metabolic abnormalities. However, “some patients also experience vague and difficult to quantify symptoms, which they describe as brain fog,” Ms. Raine said.

The brain fog phenomenon has been described with somewhat varying features in several different chronic conditions, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, post-menopausal syndrome, and recently, among people with “long haul” COVID-19 symptoms.

However, brain fog associated with treated hypothyroidism has not been explored in-depth, despite the fact that patients often report it, Ms. Raine noted.

Results will help clinicians assist patients with brain fog

Fatigue was the most prominent brain fog symptom reported in the survey, followed by forgetfulness and difficulty focusing. On the other hand, rest and relaxation were the most reported factors that alleviated symptoms, followed by thyroid hormone adjustment.

“Hopefully these findings will help clinicians to recognize and treat the symptoms of brain fog and shed light on a condition which up until now has not been very well understood,” Dr. Ettleson said.

Asked to comment, session moderator Jad G. Sfeir, MD, of the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., told this news organization: “We do see patients complain a lot about this brain fog. The question is how can I help, and what has worked for them in the past?”

“When you have symptoms that are vague, like brain fog, you don’t have a lot of objective tools to [measure], so you can’t really develop a study to see how a certain medication affects the symptoms. Relying on subjective information from patients saying what worked for them and what did not, you can draw a lot of implications to clinical practice.”

The survey results, Dr. Sfeir said, “will help direct clinicians to know what type of questions to ask patients based on the survey responses and how to make some recommendations that may help.”

Fatigue, memory problems, difficulty focusing characterize brain fog

The online survey was distributed to hypothyroidism support groups and through the American Thyroid Association. Of the 5,282 respondents with hypothyroidism and symptoms of brain fog, 46% (2,453) reported having experienced brain fog symptoms prior to their diagnosis of hypothyroidism.

The population analyzed for the study was the 17% (731) who reported experiencing brain fog weeks to months following a diagnosis of hypothyroidism. Of those, 33% had Hashimoto’s, 21% thyroid surgery, 11% RAI therapy, and 15.6% had both thyroid surgery and RAI.

Brain fog symptoms were reported as occurring “frequently” by 44.5% and “all the time” by 37.0%. The composite symptom score was 22.9 out of 30.

Fatigue, or lack of energy, was the most commonly named symptom, reported by over 90% of both the thyroid surgery/RAI and Hashimoto’s groups, and as occurring “all the time” by about half in each group. Others reported by at least half of both groups included memory problems, difficulty focusing, sleep problems, and difficulties with decision-making. Other symptoms frequently cited included confusion, mood disturbance, and anxiety.

“Each ... domain was reported with some frequency by at least 85% of respondents, regardless of etiology of hypothyroidism, so it really was a high symptom burden that we were seeing, even in those whose symptoms were the least frequent,” Ms. Raine noted.

Symptom scores generally correlated with patient satisfaction scores, particularly with those of cognitive signs and difficulty focusing.

Lifting the fog: What do patients say helps them?

The survey asked patients what factors improved or worsened their brain fog symptoms. By far, the most frequent answer was rest/relaxation, endorsed by 58.5%. Another 10.5% listed exercise/outdoor time, but 1.5% said exercise worsened their symptoms.

Unspecified adjustments of thyroid medications were said to improve symptoms for 13.9%. Specific thyroid hormones reported to improve symptoms were liothyronine in 8.8%, desiccated thyroid extract in 3.1%, and levothyroxine in 2.7%. However, another 4.2% said thyroxine worsened their symptoms.

Healthy/nutritious diets were reported to improve symptoms by 6.3%, while consuming gluten, a high-sugar diet, and consuming alcohol were reported to worsen symptoms for 1.3%, 3.2%, and 1.3%, respectively. Caffeine was said to help for 3.1% and to harm by 0.6%.

Small numbers of patients reported improvements in symptoms with vitamins B12 and D, Adderall, or other stimulant medications, antidepressants, naltrexone, sun exposure, and blood glucose stability.

Other factors reported to worsen symptoms included menstruation, infection or other acute illness, pain, and “loud noise.”

Dr. Ettleson pointed out, “For many of these patients [the brain fog] may have nothing to do with their thyroid. We saw a large proportion of patients who said they had symptoms well before they were ever diagnosed with hypothyroidism, and yet many patients have linked these brain fog symptoms to their thyroid.”

Nonetheless, he said, “I think it’s imperative for the clinician to at least engage in these conversations and not just stop when the thyroid function tests are normal. We have many lifestyle suggestions that have emerged from this study that I think physicians can put forward to patients who are dealing with this ... early in the process in addition to thyroid hormone adjustment, which may help some patients.”

Dr. Ettleson, Ms. Raine, and Dr. Sfeir have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.