User login

Zoledronate promotes postdenosumab bone retention

Women with osteoporosis who received a single infusion of zoledronate after discontinuing denosumab (Prolia) maintained bone mineral density at both the lumbar spine and the total hip, based on data from 120 individuals.

Although denosumab is often prescribed for postmenopausal osteoporosis, its effects disappear when treatment ends, wrote Judith Everts-Graber, MD, of OsteoRheuma Bern (Switzerland), and colleagues. In addition, recent reports of increased fractures in osteoporotic women after denosumab discontinuation highlight the need for subsequent therapy, but no protocol has been established.

In a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the investigators reviewed data from women aged older than 48 years with postmenopausal osteoporosis who were treated with denosumab between Aug. 1, 2010, and March 31, 2019. The women received four or more injections of 60 mg denosumab administered at 6-month intervals, followed by a single infusion of 5 mg zoledronate 6 months after the final denosumab injection. Patients were evaluated using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and vertebral fracture assessment every 2 years after starting denosumab; the average duration of treatment was 3 years.

At an average of 2.5 years after discontinuing denosumab, women who received zoledronate retained 66% of bone mineral density (BMD) gains at the lumbar spine, 49% at the total hip, and 57% at the femoral neck. In addition, three patients developed symptomatic single vertebral fractures and four patients developed peripheral fractures between 1 and 3 years after their last denosumab injections, but none of these patients sustained multiple fractures.

All bone loss occurred within 18 months of denosumab discontinuation, and no significant differences appeared between patients with gains in BMD greater than or less than 9%.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and the lack of a control group, the researchers noted. However, they collected data from 11 of 28 patients who did not follow the treatment recommendations and did not receive zoledronate after discontinuing denosumab. “As expected, BMD of the lumbar spine and total hip decreased to baseline,” they wrote. In addition, 2 of the 11 patients experienced multiple vertebral fractures.

A single 5-mg infusion of zoledronate “may be a promising step in identifying sequential long-term treatment strategies for osteoporosis,” the researchers concluded. “Nevertheless, each patient requires an individualized surveillance and treatment plan after denosumab discontinuation, including BMD assessment, evaluation of bone turnover markers and consideration of individual clinical risk factors, in particular prevalent fragility fractures.”

The study was funded by OsteoRheuma Bern. The researchers reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Everts-Graber J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Jan 28. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3962.

Women with osteoporosis who received a single infusion of zoledronate after discontinuing denosumab (Prolia) maintained bone mineral density at both the lumbar spine and the total hip, based on data from 120 individuals.

Although denosumab is often prescribed for postmenopausal osteoporosis, its effects disappear when treatment ends, wrote Judith Everts-Graber, MD, of OsteoRheuma Bern (Switzerland), and colleagues. In addition, recent reports of increased fractures in osteoporotic women after denosumab discontinuation highlight the need for subsequent therapy, but no protocol has been established.

In a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the investigators reviewed data from women aged older than 48 years with postmenopausal osteoporosis who were treated with denosumab between Aug. 1, 2010, and March 31, 2019. The women received four or more injections of 60 mg denosumab administered at 6-month intervals, followed by a single infusion of 5 mg zoledronate 6 months after the final denosumab injection. Patients were evaluated using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and vertebral fracture assessment every 2 years after starting denosumab; the average duration of treatment was 3 years.

At an average of 2.5 years after discontinuing denosumab, women who received zoledronate retained 66% of bone mineral density (BMD) gains at the lumbar spine, 49% at the total hip, and 57% at the femoral neck. In addition, three patients developed symptomatic single vertebral fractures and four patients developed peripheral fractures between 1 and 3 years after their last denosumab injections, but none of these patients sustained multiple fractures.

All bone loss occurred within 18 months of denosumab discontinuation, and no significant differences appeared between patients with gains in BMD greater than or less than 9%.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and the lack of a control group, the researchers noted. However, they collected data from 11 of 28 patients who did not follow the treatment recommendations and did not receive zoledronate after discontinuing denosumab. “As expected, BMD of the lumbar spine and total hip decreased to baseline,” they wrote. In addition, 2 of the 11 patients experienced multiple vertebral fractures.

A single 5-mg infusion of zoledronate “may be a promising step in identifying sequential long-term treatment strategies for osteoporosis,” the researchers concluded. “Nevertheless, each patient requires an individualized surveillance and treatment plan after denosumab discontinuation, including BMD assessment, evaluation of bone turnover markers and consideration of individual clinical risk factors, in particular prevalent fragility fractures.”

The study was funded by OsteoRheuma Bern. The researchers reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Everts-Graber J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Jan 28. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3962.

Women with osteoporosis who received a single infusion of zoledronate after discontinuing denosumab (Prolia) maintained bone mineral density at both the lumbar spine and the total hip, based on data from 120 individuals.

Although denosumab is often prescribed for postmenopausal osteoporosis, its effects disappear when treatment ends, wrote Judith Everts-Graber, MD, of OsteoRheuma Bern (Switzerland), and colleagues. In addition, recent reports of increased fractures in osteoporotic women after denosumab discontinuation highlight the need for subsequent therapy, but no protocol has been established.

In a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the investigators reviewed data from women aged older than 48 years with postmenopausal osteoporosis who were treated with denosumab between Aug. 1, 2010, and March 31, 2019. The women received four or more injections of 60 mg denosumab administered at 6-month intervals, followed by a single infusion of 5 mg zoledronate 6 months after the final denosumab injection. Patients were evaluated using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and vertebral fracture assessment every 2 years after starting denosumab; the average duration of treatment was 3 years.

At an average of 2.5 years after discontinuing denosumab, women who received zoledronate retained 66% of bone mineral density (BMD) gains at the lumbar spine, 49% at the total hip, and 57% at the femoral neck. In addition, three patients developed symptomatic single vertebral fractures and four patients developed peripheral fractures between 1 and 3 years after their last denosumab injections, but none of these patients sustained multiple fractures.

All bone loss occurred within 18 months of denosumab discontinuation, and no significant differences appeared between patients with gains in BMD greater than or less than 9%.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and the lack of a control group, the researchers noted. However, they collected data from 11 of 28 patients who did not follow the treatment recommendations and did not receive zoledronate after discontinuing denosumab. “As expected, BMD of the lumbar spine and total hip decreased to baseline,” they wrote. In addition, 2 of the 11 patients experienced multiple vertebral fractures.

A single 5-mg infusion of zoledronate “may be a promising step in identifying sequential long-term treatment strategies for osteoporosis,” the researchers concluded. “Nevertheless, each patient requires an individualized surveillance and treatment plan after denosumab discontinuation, including BMD assessment, evaluation of bone turnover markers and consideration of individual clinical risk factors, in particular prevalent fragility fractures.”

The study was funded by OsteoRheuma Bern. The researchers reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Everts-Graber J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Jan 28. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3962.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

Right hip and pelvic pain

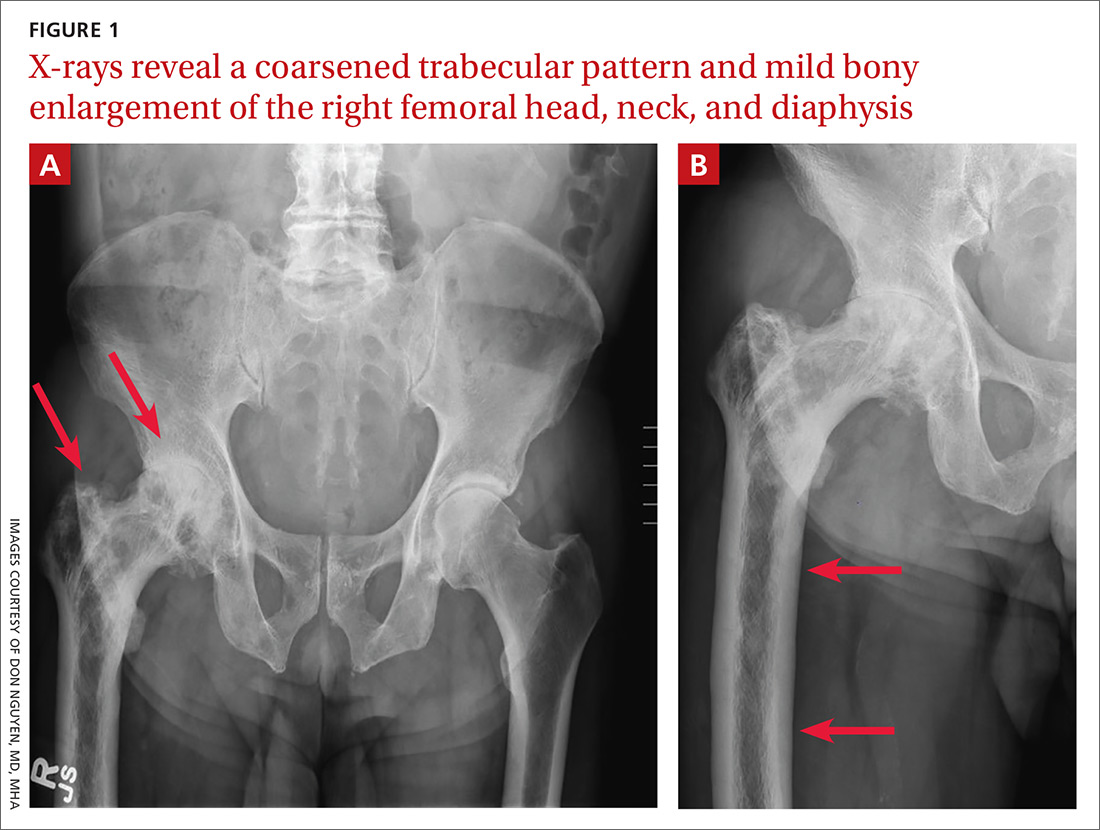

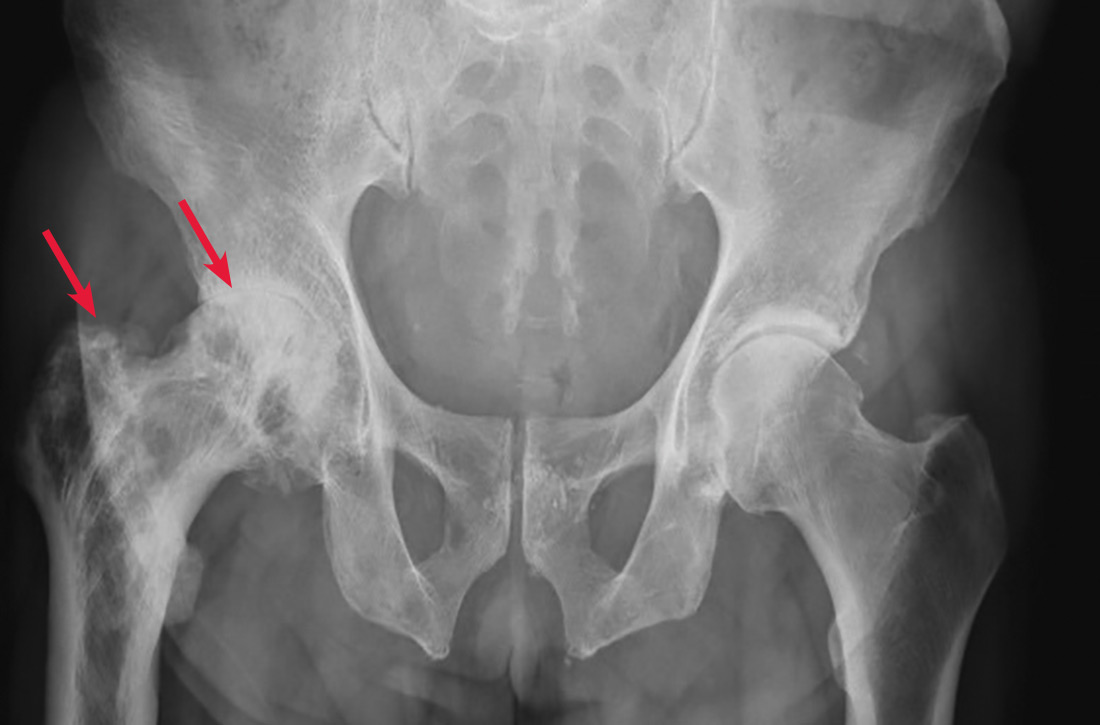

A 65-year-old man with a history of remote colon cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and bilateral knee replacements presented with right groin and hip pain of more than a year’s duration. The patient described his hip pain as aching and said that it had worsened over the previous 6 months, interfering with his sleep. He said the pain worsened following activity, and it briefly felt better following an intra-articular corticosteroid injection into his right hip. The patient denied recent trauma or fracture and said he had no scalp pain, hearing loss, or spinal tenderness. Physical examination showed limited range of motion of the right hip and mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory values were within normal limits. X-rays of the pelvis (Figure 1A) and right hip (Figure 1B) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Paget disease of bone

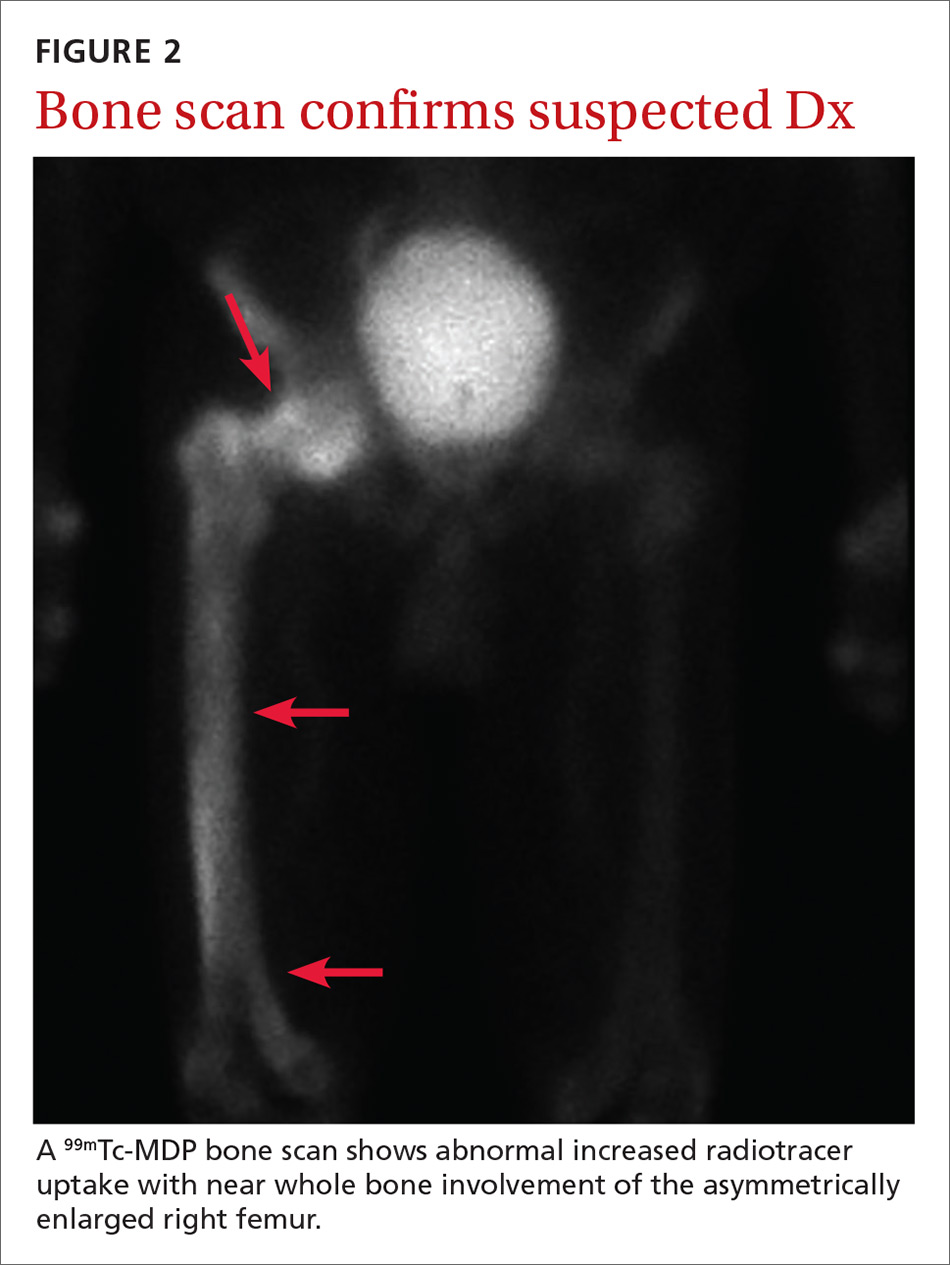

Based on the patient’s clinical history and initial imaging studies, which showed characteristic trabecular thickening with bony enlargement of the right femur, we suspected that he had Paget disease of bone. This was confirmed on subsequent whole-body 99mTc-MDP bone scan (Figure 2), which revealed corresponding diffuse increased radiotracer uptake of the right femur. There was no scintigraphic evidence of osseous involvement of the skull, spine, or pelvis.

Epidemiology/incidence. Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is fairly common in the aging population, with a prevalence ranging from 2% to almost 10%.1,2 Although onset before age 40 is rare, the diagnosis should be considered in younger patients, given the high prevalence. There is a slight male predominance, and the disease is more common in the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as in countries settled by European immigrants.3

Both genetic and environmental causes are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of Paget disease. Mutations in the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) can be seen in the autosomal dominant familial type (25%-50% of these cases), as well as in sporadic cases.4 Environmental influence has also been postulated as a possible cause, with a viral etiology (eg, chronic measles infection) being the most cited.5

Most patients will be asymptomatic

Paget disease can affect any bone in the body, although the skull, spine, pelvis, and long bones of the lower extremity are the most commonly affected sites.2 Most patients with Paget disease are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they either result from direct involvement of the bone or are secondary to bone overgrowth and deformity.

Direct involvement manifests as deep, constant bone pain that is worse at night. Symptoms related to bone overgrowth and deformity include spinal stenosis and related neurologic abnormalities, increased skull size, hearing loss (impingement of cranial nerve VIII), pathologic fracture (most commonly of the femur), and deformity such as protrusio acetabuli or femoral or tibial bowing.6 High-output heart failure and abnormalities in calcium and phosphate balance are uncommon but do occur.

Continue to: Degeneration into osteosarcoma...

Degeneration into osteosarcoma is a rare but almost invariably fatal complication of Paget disease, with an incidence of 0.2% to 1%.7 It clinically manifests as increased bone pain that is poorly responsive to medical therapy, local swelling, and pathologic fracture.8

Radiography is key to the work-up

The diagnosis of Paget disease is primarily radiographic. Early in the disease process, lytic lesions with thinning of the cortex will be noted. Later in the disease, there will be a mixed lytic/sclerotic phase, in which enlargement of the bone, a thickened cortex, and coarsened trabeculae are observed.

Characteristic radiographic findings. Focal lytic lesions in the skull are known as osteoporosis circumscripta. In the sclerotic phase, there is a thickening of the calvaria (termed “cotton wool”). Lesions involving the long bones will begin at the proximal or distal subchondral region and progress toward the diaphysis, with a sharp oblique delineation between involved bone and normal bone; this is described as “blade of grass” or “flame-shaped.”9

Within the pelvis, there will be cortical thickening and sclerosis with enlargement of the iliac wing. Within the spine, there will be enlarged vertebrae with a thickened sclerotic border, resulting in a “picture frame” appearance. Later in the disease, the sclerosis will involve the entire vertebrae (termed “ivory vertebra”).10

Additional testing options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy, laboratory testing, and biopsy.

Continue to: MRI is recommended...

MRI is recommended when degeneration into osteosarcoma is present—indicated by permeative lesions with cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass. MRI is helpful to further characterize the lesion. Absence of the normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images would be concerning for tumor involvement.

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the extent of disease. It will show increased uptake when the lesions are active.

Laboratory testing. Serum alkaline phosphatase (sAP) is frequently elevated in patients with Paget disease (normal range, 20-140 IU/L) and reflects the extent and activity of disease. However, this correlation is not always reliable; it depends on monostotic vs polyostotic involvement, as well as which bones are involved. For example, sAP levels may be markedly elevated when the skull is involved but normal when other bones are involved.11 In patients with elevated sAP, serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements should be obtained in anticipation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Biopsy. If the radiographic findings are typical for Paget disease, bone biopsy is not indicated. However, the main competing diagnosis to consider is malignancy; in atypical cases when imaging is unable to elucidate an underlying tumor, biopsy would be warranted.

Differentiating Paget disease from sclerotic metastasis is important. In metastasis, there will be no trabecular coarsening or enlargement of the bone.

Continue to: Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Indications for treatment include symptomatic or asymptomatic disease with any of the following: elevated sAP with pagetic changes at sites where complications could occur; sAP more than 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal; normal sAP with abnormal bone scintigraphy at a site where complications could occur; planned surgery at an active pagetic site; and hypercalcemia in association with immobilization in patients with polyostotic disease.

Newer generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are the mainstay of treatment; they ease pain, slow bone turnover, and promote deposition of normal lamellar bone, which over time will normalize sAP levels.12 The most frequently used and studied bisphosphonates include oral alendronate, oral risedronate, and intravenous zoledronic acid.13

Prior to treatment initiation, the patient should have documented normal serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and these levels should be monitored throughout the first year of treatment. All patients should receive supplemental vitamin D and calcium to avoid hypocalcemia. sAP should be measured at 3 to 6 months to assess the initial response to therapy. Once the levels equilibrate, sAP can be measured once or twice a year to asses bone activity.14

Our patient was referred to Endocrinology for management of Paget disease of his right hip and femur. Lab values, including sAP and liver function test results, were normal. The patient was prescribed a zoledronic acid infusion (Reclast). At 4-week follow-up, the patient reported moderate relief of bone pain and improved sleep.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don Nguyen, MD, MHA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Radiology, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; [email protected]

1. Altman RD, Bloch DA, Hochberg MC, et al. Prevalence of pelvic Paget’s disease of bone in the United States. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:461-465.

2. Singer F. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Merashli M, Jawad A. Paget’s disease of bone among various ethnic groups. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:E22-E26.

4. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2735-2739.

5. Reddy SV, Kurihara N, Menaa C, et al. Osteoclasts formed by measles virus-infected osteoclast precursors from hCD46 transgenic mice express characteristics of pagetic osteoclasts. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2898-2905.

6. Moore TE, King AR, Kathol MH, et al. Sarcoma in Paget disease of bone: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features in 22 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1199-1203.

7. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471.

8. Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P58-P63.

9. Wittenberg K. The blade of grass sign. Radiology. 2001;221:199-200.

10. Dennis JM. The solitary dense vertebral body. Radiology. 1961;77:618-621.

11. Seton M. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, eds. Rheumatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby (Elsevier); 2008:2003.

12. Reid IR, Nicholson GC, Weinstein RS, et al. Biochemical and radiologic improvement in Paget’s disease of bone treated with alendronate: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1996;101:341-348.

13. Siris ES, Lyles KW, Singer FR, et al. Medical management of Paget’s disease of bone: indications for treatment and review of current therapies. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P94-P98.

14. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guañabens N, et al. Long-term biochemical response after bisphosphonate therapy in Paget’s disease of bone: proposed intervals for monitoring treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:869-874.

A 65-year-old man with a history of remote colon cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and bilateral knee replacements presented with right groin and hip pain of more than a year’s duration. The patient described his hip pain as aching and said that it had worsened over the previous 6 months, interfering with his sleep. He said the pain worsened following activity, and it briefly felt better following an intra-articular corticosteroid injection into his right hip. The patient denied recent trauma or fracture and said he had no scalp pain, hearing loss, or spinal tenderness. Physical examination showed limited range of motion of the right hip and mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory values were within normal limits. X-rays of the pelvis (Figure 1A) and right hip (Figure 1B) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Paget disease of bone

Based on the patient’s clinical history and initial imaging studies, which showed characteristic trabecular thickening with bony enlargement of the right femur, we suspected that he had Paget disease of bone. This was confirmed on subsequent whole-body 99mTc-MDP bone scan (Figure 2), which revealed corresponding diffuse increased radiotracer uptake of the right femur. There was no scintigraphic evidence of osseous involvement of the skull, spine, or pelvis.

Epidemiology/incidence. Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is fairly common in the aging population, with a prevalence ranging from 2% to almost 10%.1,2 Although onset before age 40 is rare, the diagnosis should be considered in younger patients, given the high prevalence. There is a slight male predominance, and the disease is more common in the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as in countries settled by European immigrants.3

Both genetic and environmental causes are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of Paget disease. Mutations in the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) can be seen in the autosomal dominant familial type (25%-50% of these cases), as well as in sporadic cases.4 Environmental influence has also been postulated as a possible cause, with a viral etiology (eg, chronic measles infection) being the most cited.5

Most patients will be asymptomatic

Paget disease can affect any bone in the body, although the skull, spine, pelvis, and long bones of the lower extremity are the most commonly affected sites.2 Most patients with Paget disease are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they either result from direct involvement of the bone or are secondary to bone overgrowth and deformity.

Direct involvement manifests as deep, constant bone pain that is worse at night. Symptoms related to bone overgrowth and deformity include spinal stenosis and related neurologic abnormalities, increased skull size, hearing loss (impingement of cranial nerve VIII), pathologic fracture (most commonly of the femur), and deformity such as protrusio acetabuli or femoral or tibial bowing.6 High-output heart failure and abnormalities in calcium and phosphate balance are uncommon but do occur.

Continue to: Degeneration into osteosarcoma...

Degeneration into osteosarcoma is a rare but almost invariably fatal complication of Paget disease, with an incidence of 0.2% to 1%.7 It clinically manifests as increased bone pain that is poorly responsive to medical therapy, local swelling, and pathologic fracture.8

Radiography is key to the work-up

The diagnosis of Paget disease is primarily radiographic. Early in the disease process, lytic lesions with thinning of the cortex will be noted. Later in the disease, there will be a mixed lytic/sclerotic phase, in which enlargement of the bone, a thickened cortex, and coarsened trabeculae are observed.

Characteristic radiographic findings. Focal lytic lesions in the skull are known as osteoporosis circumscripta. In the sclerotic phase, there is a thickening of the calvaria (termed “cotton wool”). Lesions involving the long bones will begin at the proximal or distal subchondral region and progress toward the diaphysis, with a sharp oblique delineation between involved bone and normal bone; this is described as “blade of grass” or “flame-shaped.”9

Within the pelvis, there will be cortical thickening and sclerosis with enlargement of the iliac wing. Within the spine, there will be enlarged vertebrae with a thickened sclerotic border, resulting in a “picture frame” appearance. Later in the disease, the sclerosis will involve the entire vertebrae (termed “ivory vertebra”).10

Additional testing options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy, laboratory testing, and biopsy.

Continue to: MRI is recommended...

MRI is recommended when degeneration into osteosarcoma is present—indicated by permeative lesions with cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass. MRI is helpful to further characterize the lesion. Absence of the normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images would be concerning for tumor involvement.

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the extent of disease. It will show increased uptake when the lesions are active.

Laboratory testing. Serum alkaline phosphatase (sAP) is frequently elevated in patients with Paget disease (normal range, 20-140 IU/L) and reflects the extent and activity of disease. However, this correlation is not always reliable; it depends on monostotic vs polyostotic involvement, as well as which bones are involved. For example, sAP levels may be markedly elevated when the skull is involved but normal when other bones are involved.11 In patients with elevated sAP, serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements should be obtained in anticipation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Biopsy. If the radiographic findings are typical for Paget disease, bone biopsy is not indicated. However, the main competing diagnosis to consider is malignancy; in atypical cases when imaging is unable to elucidate an underlying tumor, biopsy would be warranted.

Differentiating Paget disease from sclerotic metastasis is important. In metastasis, there will be no trabecular coarsening or enlargement of the bone.

Continue to: Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Indications for treatment include symptomatic or asymptomatic disease with any of the following: elevated sAP with pagetic changes at sites where complications could occur; sAP more than 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal; normal sAP with abnormal bone scintigraphy at a site where complications could occur; planned surgery at an active pagetic site; and hypercalcemia in association with immobilization in patients with polyostotic disease.

Newer generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are the mainstay of treatment; they ease pain, slow bone turnover, and promote deposition of normal lamellar bone, which over time will normalize sAP levels.12 The most frequently used and studied bisphosphonates include oral alendronate, oral risedronate, and intravenous zoledronic acid.13

Prior to treatment initiation, the patient should have documented normal serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and these levels should be monitored throughout the first year of treatment. All patients should receive supplemental vitamin D and calcium to avoid hypocalcemia. sAP should be measured at 3 to 6 months to assess the initial response to therapy. Once the levels equilibrate, sAP can be measured once or twice a year to asses bone activity.14

Our patient was referred to Endocrinology for management of Paget disease of his right hip and femur. Lab values, including sAP and liver function test results, were normal. The patient was prescribed a zoledronic acid infusion (Reclast). At 4-week follow-up, the patient reported moderate relief of bone pain and improved sleep.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don Nguyen, MD, MHA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Radiology, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; [email protected]

A 65-year-old man with a history of remote colon cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and bilateral knee replacements presented with right groin and hip pain of more than a year’s duration. The patient described his hip pain as aching and said that it had worsened over the previous 6 months, interfering with his sleep. He said the pain worsened following activity, and it briefly felt better following an intra-articular corticosteroid injection into his right hip. The patient denied recent trauma or fracture and said he had no scalp pain, hearing loss, or spinal tenderness. Physical examination showed limited range of motion of the right hip and mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory values were within normal limits. X-rays of the pelvis (Figure 1A) and right hip (Figure 1B) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Paget disease of bone

Based on the patient’s clinical history and initial imaging studies, which showed characteristic trabecular thickening with bony enlargement of the right femur, we suspected that he had Paget disease of bone. This was confirmed on subsequent whole-body 99mTc-MDP bone scan (Figure 2), which revealed corresponding diffuse increased radiotracer uptake of the right femur. There was no scintigraphic evidence of osseous involvement of the skull, spine, or pelvis.

Epidemiology/incidence. Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is fairly common in the aging population, with a prevalence ranging from 2% to almost 10%.1,2 Although onset before age 40 is rare, the diagnosis should be considered in younger patients, given the high prevalence. There is a slight male predominance, and the disease is more common in the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as in countries settled by European immigrants.3

Both genetic and environmental causes are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of Paget disease. Mutations in the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) can be seen in the autosomal dominant familial type (25%-50% of these cases), as well as in sporadic cases.4 Environmental influence has also been postulated as a possible cause, with a viral etiology (eg, chronic measles infection) being the most cited.5

Most patients will be asymptomatic

Paget disease can affect any bone in the body, although the skull, spine, pelvis, and long bones of the lower extremity are the most commonly affected sites.2 Most patients with Paget disease are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they either result from direct involvement of the bone or are secondary to bone overgrowth and deformity.

Direct involvement manifests as deep, constant bone pain that is worse at night. Symptoms related to bone overgrowth and deformity include spinal stenosis and related neurologic abnormalities, increased skull size, hearing loss (impingement of cranial nerve VIII), pathologic fracture (most commonly of the femur), and deformity such as protrusio acetabuli or femoral or tibial bowing.6 High-output heart failure and abnormalities in calcium and phosphate balance are uncommon but do occur.

Continue to: Degeneration into osteosarcoma...

Degeneration into osteosarcoma is a rare but almost invariably fatal complication of Paget disease, with an incidence of 0.2% to 1%.7 It clinically manifests as increased bone pain that is poorly responsive to medical therapy, local swelling, and pathologic fracture.8

Radiography is key to the work-up

The diagnosis of Paget disease is primarily radiographic. Early in the disease process, lytic lesions with thinning of the cortex will be noted. Later in the disease, there will be a mixed lytic/sclerotic phase, in which enlargement of the bone, a thickened cortex, and coarsened trabeculae are observed.

Characteristic radiographic findings. Focal lytic lesions in the skull are known as osteoporosis circumscripta. In the sclerotic phase, there is a thickening of the calvaria (termed “cotton wool”). Lesions involving the long bones will begin at the proximal or distal subchondral region and progress toward the diaphysis, with a sharp oblique delineation between involved bone and normal bone; this is described as “blade of grass” or “flame-shaped.”9

Within the pelvis, there will be cortical thickening and sclerosis with enlargement of the iliac wing. Within the spine, there will be enlarged vertebrae with a thickened sclerotic border, resulting in a “picture frame” appearance. Later in the disease, the sclerosis will involve the entire vertebrae (termed “ivory vertebra”).10

Additional testing options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy, laboratory testing, and biopsy.

Continue to: MRI is recommended...

MRI is recommended when degeneration into osteosarcoma is present—indicated by permeative lesions with cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass. MRI is helpful to further characterize the lesion. Absence of the normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images would be concerning for tumor involvement.

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the extent of disease. It will show increased uptake when the lesions are active.

Laboratory testing. Serum alkaline phosphatase (sAP) is frequently elevated in patients with Paget disease (normal range, 20-140 IU/L) and reflects the extent and activity of disease. However, this correlation is not always reliable; it depends on monostotic vs polyostotic involvement, as well as which bones are involved. For example, sAP levels may be markedly elevated when the skull is involved but normal when other bones are involved.11 In patients with elevated sAP, serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements should be obtained in anticipation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Biopsy. If the radiographic findings are typical for Paget disease, bone biopsy is not indicated. However, the main competing diagnosis to consider is malignancy; in atypical cases when imaging is unable to elucidate an underlying tumor, biopsy would be warranted.

Differentiating Paget disease from sclerotic metastasis is important. In metastasis, there will be no trabecular coarsening or enlargement of the bone.

Continue to: Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Indications for treatment include symptomatic or asymptomatic disease with any of the following: elevated sAP with pagetic changes at sites where complications could occur; sAP more than 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal; normal sAP with abnormal bone scintigraphy at a site where complications could occur; planned surgery at an active pagetic site; and hypercalcemia in association with immobilization in patients with polyostotic disease.

Newer generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are the mainstay of treatment; they ease pain, slow bone turnover, and promote deposition of normal lamellar bone, which over time will normalize sAP levels.12 The most frequently used and studied bisphosphonates include oral alendronate, oral risedronate, and intravenous zoledronic acid.13

Prior to treatment initiation, the patient should have documented normal serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and these levels should be monitored throughout the first year of treatment. All patients should receive supplemental vitamin D and calcium to avoid hypocalcemia. sAP should be measured at 3 to 6 months to assess the initial response to therapy. Once the levels equilibrate, sAP can be measured once or twice a year to asses bone activity.14

Our patient was referred to Endocrinology for management of Paget disease of his right hip and femur. Lab values, including sAP and liver function test results, were normal. The patient was prescribed a zoledronic acid infusion (Reclast). At 4-week follow-up, the patient reported moderate relief of bone pain and improved sleep.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don Nguyen, MD, MHA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Radiology, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; [email protected]

1. Altman RD, Bloch DA, Hochberg MC, et al. Prevalence of pelvic Paget’s disease of bone in the United States. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:461-465.

2. Singer F. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Merashli M, Jawad A. Paget’s disease of bone among various ethnic groups. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:E22-E26.

4. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2735-2739.

5. Reddy SV, Kurihara N, Menaa C, et al. Osteoclasts formed by measles virus-infected osteoclast precursors from hCD46 transgenic mice express characteristics of pagetic osteoclasts. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2898-2905.

6. Moore TE, King AR, Kathol MH, et al. Sarcoma in Paget disease of bone: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features in 22 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1199-1203.

7. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471.

8. Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P58-P63.

9. Wittenberg K. The blade of grass sign. Radiology. 2001;221:199-200.

10. Dennis JM. The solitary dense vertebral body. Radiology. 1961;77:618-621.

11. Seton M. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, eds. Rheumatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby (Elsevier); 2008:2003.

12. Reid IR, Nicholson GC, Weinstein RS, et al. Biochemical and radiologic improvement in Paget’s disease of bone treated with alendronate: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1996;101:341-348.

13. Siris ES, Lyles KW, Singer FR, et al. Medical management of Paget’s disease of bone: indications for treatment and review of current therapies. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P94-P98.

14. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guañabens N, et al. Long-term biochemical response after bisphosphonate therapy in Paget’s disease of bone: proposed intervals for monitoring treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:869-874.

1. Altman RD, Bloch DA, Hochberg MC, et al. Prevalence of pelvic Paget’s disease of bone in the United States. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:461-465.

2. Singer F. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Merashli M, Jawad A. Paget’s disease of bone among various ethnic groups. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:E22-E26.

4. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2735-2739.

5. Reddy SV, Kurihara N, Menaa C, et al. Osteoclasts formed by measles virus-infected osteoclast precursors from hCD46 transgenic mice express characteristics of pagetic osteoclasts. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2898-2905.

6. Moore TE, King AR, Kathol MH, et al. Sarcoma in Paget disease of bone: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features in 22 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1199-1203.

7. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471.

8. Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P58-P63.

9. Wittenberg K. The blade of grass sign. Radiology. 2001;221:199-200.

10. Dennis JM. The solitary dense vertebral body. Radiology. 1961;77:618-621.

11. Seton M. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, eds. Rheumatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby (Elsevier); 2008:2003.

12. Reid IR, Nicholson GC, Weinstein RS, et al. Biochemical and radiologic improvement in Paget’s disease of bone treated with alendronate: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1996;101:341-348.

13. Siris ES, Lyles KW, Singer FR, et al. Medical management of Paget’s disease of bone: indications for treatment and review of current therapies. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P94-P98.

14. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guañabens N, et al. Long-term biochemical response after bisphosphonate therapy in Paget’s disease of bone: proposed intervals for monitoring treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:869-874.

33-year-old man • flaccid paralysis in limbs • 30-lb weight loss • thyromegaly without nodules • Dx?

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; [email protected].

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; [email protected].

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

Teprotumumab gets FDA go-ahead for thyroid eye disease

according to a press release.

Thyroid eye disease is a rare, progressive, autoimmune condition that causes the eyes to bulge (proptosis) and can lead to blindness. Until now, treatment has focused on managing its symptoms – which can include eye pain, double vision, or sensitivity to light – with steroids, and in some cases, multiple invasive surgeries.

The human monoclonal antibody and a targeted inhibitor of the insulinlike growth factor-1 receptor is administered to patients once every 3 weeks, for a total of eight infusions, according to a statement from Horizon Therapeutics, which manufactures the drug.

The approval was based on the findings from two similarly designed, parallel-group studies (Studies 1 and 2) involving 170 patients with thyroid eye disease who were randomized to receive either teprotumumab or placebo. Of those receiving the study drug, 71% in Study 1 and 83% in Study 2 had a reduction of more than 2 mm in eye protrusion, compared with 20% and 10%, respectively, among the placebo participants.

The most common adverse reactions in patients receiving teprotumumab were muscle spasm, nausea, alopecia, diarrhea, fatigue, and hyperglycemia. The treatment is contraindicated for pregnancy.

according to a press release.

Thyroid eye disease is a rare, progressive, autoimmune condition that causes the eyes to bulge (proptosis) and can lead to blindness. Until now, treatment has focused on managing its symptoms – which can include eye pain, double vision, or sensitivity to light – with steroids, and in some cases, multiple invasive surgeries.

The human monoclonal antibody and a targeted inhibitor of the insulinlike growth factor-1 receptor is administered to patients once every 3 weeks, for a total of eight infusions, according to a statement from Horizon Therapeutics, which manufactures the drug.

The approval was based on the findings from two similarly designed, parallel-group studies (Studies 1 and 2) involving 170 patients with thyroid eye disease who were randomized to receive either teprotumumab or placebo. Of those receiving the study drug, 71% in Study 1 and 83% in Study 2 had a reduction of more than 2 mm in eye protrusion, compared with 20% and 10%, respectively, among the placebo participants.

The most common adverse reactions in patients receiving teprotumumab were muscle spasm, nausea, alopecia, diarrhea, fatigue, and hyperglycemia. The treatment is contraindicated for pregnancy.

according to a press release.

Thyroid eye disease is a rare, progressive, autoimmune condition that causes the eyes to bulge (proptosis) and can lead to blindness. Until now, treatment has focused on managing its symptoms – which can include eye pain, double vision, or sensitivity to light – with steroids, and in some cases, multiple invasive surgeries.

The human monoclonal antibody and a targeted inhibitor of the insulinlike growth factor-1 receptor is administered to patients once every 3 weeks, for a total of eight infusions, according to a statement from Horizon Therapeutics, which manufactures the drug.

The approval was based on the findings from two similarly designed, parallel-group studies (Studies 1 and 2) involving 170 patients with thyroid eye disease who were randomized to receive either teprotumumab or placebo. Of those receiving the study drug, 71% in Study 1 and 83% in Study 2 had a reduction of more than 2 mm in eye protrusion, compared with 20% and 10%, respectively, among the placebo participants.

The most common adverse reactions in patients receiving teprotumumab were muscle spasm, nausea, alopecia, diarrhea, fatigue, and hyperglycemia. The treatment is contraindicated for pregnancy.

FROM THE FDA

Testosterone gel increases LV mass in older men

PHILADELPHIA – Testosterone gel for treatment of hypogonadism in older men boosted their left ventricular mass by 3.5% in a single year in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial, although the clinical implications of this impressive increase remain unclear, Elizabeth Hutchins, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“I do think these results should be considered as part of the safety profile for testosterone gel and also represent an interesting and understudied area for future research,” said Dr. Hutchins, a hospitalist affiliated with the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

The Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial was one of seven coordinated placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of the impact of raising serum testosterone levels in older men with low testosterone. Some results of what are known as the TTrials have previously been reported (Endocr Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39[3]:369-86).

Dr. Hutchins presented new findings on the effect of treatment with 1% topical testosterone gel on body surface area–indexed left ventricular mass. The trial utilized a widely prescribed, commercially available product known as AndroGel. The study included 123 men over age 65 with low serum testosterone and coronary CT angiography images obtained at baseline and again after 1 year of double-blind testosterone gel or placebo. More than 80% of the men were above age 75, half were obese, more than two-thirds had hypertension, and 30% had diabetes.

The men initially applied 5 g of the testosterone gel daily, providing 15 mg/day of testosterone, with subsequent dosing adjustments as needed based on serum testosterone levels measured at a central laboratory. Participants were evaluated in office visits with serum testosterone measurements every 3 months. Testosterone levels in the men assigned to active treatment quickly rose to normal range and stayed there for the full 12 months, while the placebo-treated controls continued to have below-normal testosterone throughout the trial.

The key study finding was that LV mass indexed to body surface area rose significantly in the testosterone gel group, from an average of 71.5 g/m2 at baseline to 74.8 g/m2 at 1 year. That’s a statistically significant 3.5% increase. In contrast, LV mass remained flat across the year in controls: 73.8 g/m2 at baseline and 73.3 g/m2 at 12 months.

There was, however, no change over time in left or right atrial or ventricular chamber volumes in the testosterone gel recipients, nor in the controls.

Session comoderator Eric D. Peterson, MD, professor of medicine and a cardiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said that “this is a very important topic,” then posed a provocative question to Dr. Hutchins: “If the intervention had been running instead of testosterone gel, would the results have looked similar, and would you be concluding that there should be a warning around the use of running?”

Dr. Hutchins replied that she’s given that question much thought.

“Of course, exercise leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that to be good muscle, and high blood pressure leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that bad muscle. So which one is it in this case? From what I can find in the literature, it seems that incremental increases in LV mass in the absence of being an athlete are deleterious. But I think we would need outcomes-based research to really answer that question,” she said.

Dr. Hutchins noted that this was the first-ever randomized controlled trial to measure the effect of testosterone therapy on LV mass in humans. The documented increase achieved with 1 year of testosterone gel doesn’t come close to reaching the threshold of LV hypertrophy, which is about 125 g/m2 for men. But evidence from animal and observational human studies suggests that even in the absence of LV hypertrophy, increases in LV mass are associated with increased mortality, she added.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Hutchins E. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.04.

PHILADELPHIA – Testosterone gel for treatment of hypogonadism in older men boosted their left ventricular mass by 3.5% in a single year in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial, although the clinical implications of this impressive increase remain unclear, Elizabeth Hutchins, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“I do think these results should be considered as part of the safety profile for testosterone gel and also represent an interesting and understudied area for future research,” said Dr. Hutchins, a hospitalist affiliated with the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

The Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial was one of seven coordinated placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of the impact of raising serum testosterone levels in older men with low testosterone. Some results of what are known as the TTrials have previously been reported (Endocr Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39[3]:369-86).

Dr. Hutchins presented new findings on the effect of treatment with 1% topical testosterone gel on body surface area–indexed left ventricular mass. The trial utilized a widely prescribed, commercially available product known as AndroGel. The study included 123 men over age 65 with low serum testosterone and coronary CT angiography images obtained at baseline and again after 1 year of double-blind testosterone gel or placebo. More than 80% of the men were above age 75, half were obese, more than two-thirds had hypertension, and 30% had diabetes.

The men initially applied 5 g of the testosterone gel daily, providing 15 mg/day of testosterone, with subsequent dosing adjustments as needed based on serum testosterone levels measured at a central laboratory. Participants were evaluated in office visits with serum testosterone measurements every 3 months. Testosterone levels in the men assigned to active treatment quickly rose to normal range and stayed there for the full 12 months, while the placebo-treated controls continued to have below-normal testosterone throughout the trial.

The key study finding was that LV mass indexed to body surface area rose significantly in the testosterone gel group, from an average of 71.5 g/m2 at baseline to 74.8 g/m2 at 1 year. That’s a statistically significant 3.5% increase. In contrast, LV mass remained flat across the year in controls: 73.8 g/m2 at baseline and 73.3 g/m2 at 12 months.

There was, however, no change over time in left or right atrial or ventricular chamber volumes in the testosterone gel recipients, nor in the controls.

Session comoderator Eric D. Peterson, MD, professor of medicine and a cardiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said that “this is a very important topic,” then posed a provocative question to Dr. Hutchins: “If the intervention had been running instead of testosterone gel, would the results have looked similar, and would you be concluding that there should be a warning around the use of running?”

Dr. Hutchins replied that she’s given that question much thought.

“Of course, exercise leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that to be good muscle, and high blood pressure leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that bad muscle. So which one is it in this case? From what I can find in the literature, it seems that incremental increases in LV mass in the absence of being an athlete are deleterious. But I think we would need outcomes-based research to really answer that question,” she said.

Dr. Hutchins noted that this was the first-ever randomized controlled trial to measure the effect of testosterone therapy on LV mass in humans. The documented increase achieved with 1 year of testosterone gel doesn’t come close to reaching the threshold of LV hypertrophy, which is about 125 g/m2 for men. But evidence from animal and observational human studies suggests that even in the absence of LV hypertrophy, increases in LV mass are associated with increased mortality, she added.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Hutchins E. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.04.

PHILADELPHIA – Testosterone gel for treatment of hypogonadism in older men boosted their left ventricular mass by 3.5% in a single year in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial, although the clinical implications of this impressive increase remain unclear, Elizabeth Hutchins, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“I do think these results should be considered as part of the safety profile for testosterone gel and also represent an interesting and understudied area for future research,” said Dr. Hutchins, a hospitalist affiliated with the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

The Testosterone Cardiovascular Trial was one of seven coordinated placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials of the impact of raising serum testosterone levels in older men with low testosterone. Some results of what are known as the TTrials have previously been reported (Endocr Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39[3]:369-86).

Dr. Hutchins presented new findings on the effect of treatment with 1% topical testosterone gel on body surface area–indexed left ventricular mass. The trial utilized a widely prescribed, commercially available product known as AndroGel. The study included 123 men over age 65 with low serum testosterone and coronary CT angiography images obtained at baseline and again after 1 year of double-blind testosterone gel or placebo. More than 80% of the men were above age 75, half were obese, more than two-thirds had hypertension, and 30% had diabetes.

The men initially applied 5 g of the testosterone gel daily, providing 15 mg/day of testosterone, with subsequent dosing adjustments as needed based on serum testosterone levels measured at a central laboratory. Participants were evaluated in office visits with serum testosterone measurements every 3 months. Testosterone levels in the men assigned to active treatment quickly rose to normal range and stayed there for the full 12 months, while the placebo-treated controls continued to have below-normal testosterone throughout the trial.

The key study finding was that LV mass indexed to body surface area rose significantly in the testosterone gel group, from an average of 71.5 g/m2 at baseline to 74.8 g/m2 at 1 year. That’s a statistically significant 3.5% increase. In contrast, LV mass remained flat across the year in controls: 73.8 g/m2 at baseline and 73.3 g/m2 at 12 months.

There was, however, no change over time in left or right atrial or ventricular chamber volumes in the testosterone gel recipients, nor in the controls.

Session comoderator Eric D. Peterson, MD, professor of medicine and a cardiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said that “this is a very important topic,” then posed a provocative question to Dr. Hutchins: “If the intervention had been running instead of testosterone gel, would the results have looked similar, and would you be concluding that there should be a warning around the use of running?”

Dr. Hutchins replied that she’s given that question much thought.

“Of course, exercise leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that to be good muscle, and high blood pressure leads to LV hypertrophy and we consider that bad muscle. So which one is it in this case? From what I can find in the literature, it seems that incremental increases in LV mass in the absence of being an athlete are deleterious. But I think we would need outcomes-based research to really answer that question,” she said.

Dr. Hutchins noted that this was the first-ever randomized controlled trial to measure the effect of testosterone therapy on LV mass in humans. The documented increase achieved with 1 year of testosterone gel doesn’t come close to reaching the threshold of LV hypertrophy, which is about 125 g/m2 for men. But evidence from animal and observational human studies suggests that even in the absence of LV hypertrophy, increases in LV mass are associated with increased mortality, she added.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Hutchins E. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.04.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

Treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is a work in progress

LOS ANGELES – When it comes to the optimal treatment of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diabetes, cardiologists like Mark T. Kearney, MB ChB, MD, remain stumped.

“Over the years, the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction has been notoriously difficult [to treat], controversial, and ultimately involves aggressive catheterization of the heart to assess diastolic dysfunction, complex echocardiography, and invasive tests,” Dr. Kearney said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. “These patients have an ejection fraction of over 50% and classic signs and symptoms of heart failure. Studies of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers have been unsuccessful in this group of patients. We’re at the beginning of a journey in understanding this disorder, and it’s important, because more and more patients present to us with signs and symptoms of heart failure with an ejection fraction greater than 50%.”