User login

NIH director updates study enrolling one million participants

NEW ORLEANS – It is not too late to enroll your patients or yourself into the largest longitudinal cohort study ever initiated, according to Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, who is director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Since May 2018, when it was initiated, the NIH-funded All of Us Research Program has already enrolled 200,000 of the planned goal of one million participants in the United States. Of these, approximately half have already provided baseline demographics and health information as well as their consent to use the slew of health data that is being collected.

“The only way to do this kind of thing is to have data – a lot of it,” said Dr. Collins, explaining the premise of the All of Us Research Program in an interview conducted at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The data are not limited to medical records: Blood samples, whole genome sequencing, wearable activity monitors, and subject-completed questionnaires are among a long list of sources of information to be collected from participants, who are expected to be followed indefinitely.

According to Dr. Collins, who delivered a plenary address at the meeting, these data will become more valuable over time, one of the most important goals of this study is to prepare the way for precision medicine. As opposed to the traditional one-size-fits-all approach to treating disease, he believes that this large dataset will allow researchers to understand differences in common diseases at the individual level.

In relation to endocrinology, Dr. Collins said that a cohort of one million participants would be expected to have close to 100,000 individuals with diabetes mellitus.

“This is going to be transformative,” said Dr. Collins, who emphasized that the enrollment is specifically designed to capture participants from diverse ethnic and racial groups.

All of the data collected will be made broadly available to research initiatives of all kinds, many of which have not yet even been envisioned.

Information on enrollment is available on line: joinallofus.org.

NEW ORLEANS – It is not too late to enroll your patients or yourself into the largest longitudinal cohort study ever initiated, according to Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, who is director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Since May 2018, when it was initiated, the NIH-funded All of Us Research Program has already enrolled 200,000 of the planned goal of one million participants in the United States. Of these, approximately half have already provided baseline demographics and health information as well as their consent to use the slew of health data that is being collected.

“The only way to do this kind of thing is to have data – a lot of it,” said Dr. Collins, explaining the premise of the All of Us Research Program in an interview conducted at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The data are not limited to medical records: Blood samples, whole genome sequencing, wearable activity monitors, and subject-completed questionnaires are among a long list of sources of information to be collected from participants, who are expected to be followed indefinitely.

According to Dr. Collins, who delivered a plenary address at the meeting, these data will become more valuable over time, one of the most important goals of this study is to prepare the way for precision medicine. As opposed to the traditional one-size-fits-all approach to treating disease, he believes that this large dataset will allow researchers to understand differences in common diseases at the individual level.

In relation to endocrinology, Dr. Collins said that a cohort of one million participants would be expected to have close to 100,000 individuals with diabetes mellitus.

“This is going to be transformative,” said Dr. Collins, who emphasized that the enrollment is specifically designed to capture participants from diverse ethnic and racial groups.

All of the data collected will be made broadly available to research initiatives of all kinds, many of which have not yet even been envisioned.

Information on enrollment is available on line: joinallofus.org.

NEW ORLEANS – It is not too late to enroll your patients or yourself into the largest longitudinal cohort study ever initiated, according to Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, who is director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Since May 2018, when it was initiated, the NIH-funded All of Us Research Program has already enrolled 200,000 of the planned goal of one million participants in the United States. Of these, approximately half have already provided baseline demographics and health information as well as their consent to use the slew of health data that is being collected.

“The only way to do this kind of thing is to have data – a lot of it,” said Dr. Collins, explaining the premise of the All of Us Research Program in an interview conducted at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The data are not limited to medical records: Blood samples, whole genome sequencing, wearable activity monitors, and subject-completed questionnaires are among a long list of sources of information to be collected from participants, who are expected to be followed indefinitely.

According to Dr. Collins, who delivered a plenary address at the meeting, these data will become more valuable over time, one of the most important goals of this study is to prepare the way for precision medicine. As opposed to the traditional one-size-fits-all approach to treating disease, he believes that this large dataset will allow researchers to understand differences in common diseases at the individual level.

In relation to endocrinology, Dr. Collins said that a cohort of one million participants would be expected to have close to 100,000 individuals with diabetes mellitus.

“This is going to be transformative,” said Dr. Collins, who emphasized that the enrollment is specifically designed to capture participants from diverse ethnic and racial groups.

All of the data collected will be made broadly available to research initiatives of all kinds, many of which have not yet even been envisioned.

Information on enrollment is available on line: joinallofus.org.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

Treatment with levothyroxine does not improve the live birth rate in women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies before conception, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Until now, the evidence for the use of levothyroxine in pregnant women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies but normal thyroid function has been inconclusive, Rima K. Dhillon-Smith, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England), and her coauthors said in a paper published simultaneously with the meeting presentation March 23 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous studies have shown that women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies but normal thyroid function have a nearly fourfold higher risk of miscarriage and twofold higher risk of preterm birth, compared with women who don’t have the antibodies.

In the new double-blind study, 952 women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies, normal thyroid function, and a history of miscarriage or infertility were randomized either to daily 50 mcg levothyroxine or placebo, taken from conception to the end of pregnancy.

The rate of pregnancy was similar in the levothyroxine and placebo groups (56.6% vs. 58.3%, respectively), as was the live birth rate (37.4% vs. 37.9%), despite the observation that the levothyroxine group had consistently lower serum thyrotropin and higher free T4 concentrations than did the placebo group.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in secondary outcomes of miscarriage, preterm birth, or neonatal outcomes such as birth weight.

Researchers also saw no statistically significant differences in the rate of serious adverse events or in the number of women who showed abnormal results on thyroid function tests.

The authors noted that the dosage of levothyroxine used in the study was fixed, leaving the possibility that “the dose may need to be adjusted depending on the participant’s body weight, thyroid peroxidase antibody level, or thyrotropin concentration.”

Existing guidelines from the American Thyroid Association acknowledge the lack of evidence in favor of levothyroxine decreasing the risk of pregnancy loss. However, the guidelines also state that it can be considered in antibody-positive, euthyroid women with a history of loss, “given its potential benefits in comparison with its minimal risk.”

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Dhillon-Smith R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 March 23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812537

Treatment with levothyroxine does not improve the live birth rate in women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies before conception, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Until now, the evidence for the use of levothyroxine in pregnant women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies but normal thyroid function has been inconclusive, Rima K. Dhillon-Smith, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England), and her coauthors said in a paper published simultaneously with the meeting presentation March 23 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous studies have shown that women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies but normal thyroid function have a nearly fourfold higher risk of miscarriage and twofold higher risk of preterm birth, compared with women who don’t have the antibodies.

In the new double-blind study, 952 women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies, normal thyroid function, and a history of miscarriage or infertility were randomized either to daily 50 mcg levothyroxine or placebo, taken from conception to the end of pregnancy.

The rate of pregnancy was similar in the levothyroxine and placebo groups (56.6% vs. 58.3%, respectively), as was the live birth rate (37.4% vs. 37.9%), despite the observation that the levothyroxine group had consistently lower serum thyrotropin and higher free T4 concentrations than did the placebo group.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in secondary outcomes of miscarriage, preterm birth, or neonatal outcomes such as birth weight.

Researchers also saw no statistically significant differences in the rate of serious adverse events or in the number of women who showed abnormal results on thyroid function tests.

The authors noted that the dosage of levothyroxine used in the study was fixed, leaving the possibility that “the dose may need to be adjusted depending on the participant’s body weight, thyroid peroxidase antibody level, or thyrotropin concentration.”

Existing guidelines from the American Thyroid Association acknowledge the lack of evidence in favor of levothyroxine decreasing the risk of pregnancy loss. However, the guidelines also state that it can be considered in antibody-positive, euthyroid women with a history of loss, “given its potential benefits in comparison with its minimal risk.”

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Dhillon-Smith R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 March 23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812537

Treatment with levothyroxine does not improve the live birth rate in women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies before conception, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Until now, the evidence for the use of levothyroxine in pregnant women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies but normal thyroid function has been inconclusive, Rima K. Dhillon-Smith, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England), and her coauthors said in a paper published simultaneously with the meeting presentation March 23 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous studies have shown that women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies but normal thyroid function have a nearly fourfold higher risk of miscarriage and twofold higher risk of preterm birth, compared with women who don’t have the antibodies.

In the new double-blind study, 952 women with thyroid peroxidase antibodies, normal thyroid function, and a history of miscarriage or infertility were randomized either to daily 50 mcg levothyroxine or placebo, taken from conception to the end of pregnancy.

The rate of pregnancy was similar in the levothyroxine and placebo groups (56.6% vs. 58.3%, respectively), as was the live birth rate (37.4% vs. 37.9%), despite the observation that the levothyroxine group had consistently lower serum thyrotropin and higher free T4 concentrations than did the placebo group.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in secondary outcomes of miscarriage, preterm birth, or neonatal outcomes such as birth weight.

Researchers also saw no statistically significant differences in the rate of serious adverse events or in the number of women who showed abnormal results on thyroid function tests.

The authors noted that the dosage of levothyroxine used in the study was fixed, leaving the possibility that “the dose may need to be adjusted depending on the participant’s body weight, thyroid peroxidase antibody level, or thyrotropin concentration.”

Existing guidelines from the American Thyroid Association acknowledge the lack of evidence in favor of levothyroxine decreasing the risk of pregnancy loss. However, the guidelines also state that it can be considered in antibody-positive, euthyroid women with a history of loss, “given its potential benefits in comparison with its minimal risk.”

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Dhillon-Smith R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 March 23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812537

FROM ENDO 2019

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Pregnancy rates and outcomes were similar in women treated with levothyroxine and those treated with placebo.

Study details: Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 952 women.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Dhillon-Smith R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 March 23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812537

Newer antihyperglycemic drugs have distinctive CV, kidney benefits

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

FROM CIRCULATION

A paraneoplastic potassium and acid-base disturbance

NOTE: The scenario presented here is partly based on cases reported elsewhere by Martínez-Valles et al1 and Fernández-Rodríguez et al.2

A 55-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with generalized malaise, paresthesias, and severe hypertension. He says he had experienced agitation along with weakness on exertion 24 hours before presentation to the emergency department, with subsequent onset of paresthesias in his lower extremities and perioral area.

He is already known to have mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with a ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)to forced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 70% and an FEV1 85% of predicted. In addition, he was recently diagnosed with diabetes, resistant hypertension requiring maximum doses of 3 agents (a calcium channel blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and a loop diuretic), and hyperlipidemia.

He is a current smoker with a 30-pack-year smoking history. He does not use alcohol. His family history is noncontributory.

ASSESSING ACID-BASE DISORDERS

1. What type of acid-base disorder does this patient have?

- Metabolic acidosis

- Respiratory acidosis

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Respiratory alkalosis

The patient has metabolic alkalosis.

A 5-step approach

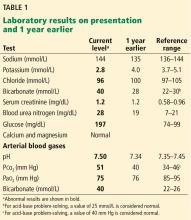

1. Acidosis or alkalosis? The patient’s arterial pH is 7.5, which is alkalemic because it is higher than 7.44.

2. Metabolic or respiratory? The primary process in our patient is overwhelmingly metabolic, as his partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2) is slightly elevated, a direction that would cause acidosis, not alkalosis.

3. The anion gap (the serum sodium concentration minus the sum of the chloride and bicarbonate concentrations) is normal at 8 mmol/L (DRG:HYBRiD-XL Immunoassay and Clinical Chemistry Analyzer, reference range 8–16).

4. Is the disturbance compensated? We have determined that this patient has a metabolic alkalemia; the question now is whether there is any compensation for the primary disturbance.

In metabolic alkalosis, the Pco2 may increase by approximately 0.6 mm Hg (range 0.5–0.8) above the nominal normal level of 40 mm Hg for each 1-mmol/L increase in bicarbonate above the nominal normal level of 25 mmol/L.4 If the patient requires oxygen, the calculation may be unreliable, however, as hypoxemia may have an overriding influence on respiratory drive.

Patients with chronically high Pco2 levels such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can become accustomed to high carbon dioxide levels and lose their hyper-

capnic respiratory drive. Giving oxygen supplementation is thought to decrease respiratory drive in these patients, so that they will breathe slower and retain more carbon dioxide. There is some degree of respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis that occurs by breathing less, though it is limited overall—even in very alkalotic patients, breathing less results in CO2 retention, which, by displacing O2 molecules in the alveoli, will in turn result in hypoxia. The brain then senses the hypoxia and makes one breathe faster, thereby limiting this compensation.

This patient’s serum bicarbonate level is 40 mmol/L, or 15 mmol/L higher than the nominal normal level. If he is compensating, his Pco2 should be 40 + (15 × 0.6) = 49 mm Hg, and in fact it is 51 mm Hg, which is within the normal range of expected compensation (47.5–52 mm Hg). Therefore, yes, he is compensating for the primary disturbance.

5. In metabolic acidosis, is there a delta gap? As our patient has metabolic alkalosis, not acidosis, this question does not apply in this case.

WHICH TEST TO FIND THE CAUSE?

2. Which is the best test to order next to determine the cause of this patient’s hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis?

- Serum magnesium level

- Spot urine chloride

- Renal ultrasonography

- 24-hour urine collection for sodium, potassium, and chloride

The patient’s loop diuretic is withheld for 12 hours and a spot urine chloride is obtained, which is reported as 44 mmol/L. This high value suggests that a volume-independent hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis is present with potassium depletion.

As for the other answer choices:

Serum magnesium. Though hypomagnesemia can cause hypokalemia due to lack of inhibition of renal outer medullary potassium channels and subsequent increased excretion of potassium in the apical tubular membrane, it is not independently associated with acid-base disturbances.5

Renal ultrasonography gives information about structural kidney disease but is of limited utility in identifying the cause of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis.

A 24-hour urine collection is unnecessary in this setting and would ultimately result in delay in diagnosis, as spot urine chloride is a more efficient means of rapidly distinguishing volume-responsive vs volume-independent causes of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis.6

IS HIS HYPERTENSION SECONDARY? IF SO, WHAT IS THE CAUSE?

Several features of this case suggest that the patient’s hypertension is secondary rather than primary. It is of recent onset. The patient’s family history is noncontributory, and his hypertension is resistant to the use of maximum doses of 3 antihypertensive agents.

3. Which of the following causes of secondary hypertension is not commonly associated with hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis?

- Hyperaldosteronism

- Liddle syndrome

- Cushing syndrome

- Renal parenchymal disease

- Chronic licorice ingestion

Renal parenchymal disease is a cause of resistant hypertension, but it is not characterized by metabolic alkalosis, hypokalemia, and elevated urine chloride,7 while the others listed here—hyperaldosteronism, Liddle syndrome, Cushing syndrome, and chronic licorice ingestion—are. Other common causes of resistant hypertension without these metabolic abnormalities include obstructive sleep apnea, alcohol abuse, and nonadherence to treatment.

While treatment of hypertension with loop diuretics can result in hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis due to the effect of these drugs on potassium reabsorption in the loop of Henle, the patient’s hypokalemia persisted after this agent was withdrawn.8

Causes of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with and without hypertension are further delineated in Figure 1.

Additional diagnostic testing: Plasma renin and plasma aldosterone

At this juncture, the differential diagnosis for this patient’s potassium depletion, metabolic alkalosis, high urine chloride, and hypertension has been narrowed to primary or secondary hyperaldosteronism, surreptitious mineralocorticoid ingestion, Cushing syndrome, licorice ingestion, Liddle syndrome, or one of the 3 hydroxylase deficiencies (11-, 17-, and 21-) (Figure 1).

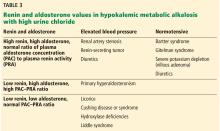

Although clues in the history, physical examination, and imaging may suggest a specific cause of his abnormal laboratory values, the next step in the diagnostic workup is to measure the plasma renin and aldosterone levels (Table 3).

HYPERALDOSTERONISM

4. Hyperaldosteronism is associated with which of the following patterns of renin and aldosterone values?

- High renin, high aldosterone, normal ratio of plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) to plasma renin activity (PRA)

- Low renin, low aldosterone, normal PAC–PRA ratio

- Low renin, high aldosterone, high PAC–PRA ratio

- High renin, low aldosterone, low PAC–PRA ratio

The pattern of low renin, high aldosterone, and high PAC–PRA ratio is associated with hyperaldosteronism.

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Primary hyperaldosteronism is one of the most common causes of resistant hypertension and is underappreciated, being diagnosed in up to 20% of patients referred to hypertension specialty clinics.7 Potassium levels may be normal, likely contributing to its lack of recognition in this target population.

Primary hyperaldosteronism should be suspected in patients who have a plasma aldosterone PAC–PRA ratio greater than 20 with elevated plasma aldosterone concentrations

(> 15 ng/dL).

Persistently elevated aldosterone levels in the setting of elevated plasma volume is proof that aldosterone secretion is independent of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, and therefore is autonomous (secondary to adrenal tumor or hyperplasia). Further testing in the form of oral salt loading, saline infusion, or fludrocortisone (a sodium-retaining steroid) administration is thus required to confirm inappropriate, autonomous aldosterone secretion.9

After establishing the diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism, one should determine the subtype (ie, due to an adrenal carcinoma, unilateral hypersecreting adenoma, or unilateral or bilateral hyperplasia). Further testing includes adrenal computed tomography (CT) to rule out adrenal carcinomas, which are suspected with adenomas larger than 4 cm. Though part of the diagnostic workup, CT as a means of confirmational testing alone does not preclude the possibility of bilateral adrenal hyperplasia in some patients, even in the presence of an adrenal adenoma. For this reason, adrenal venous sampling is required to definitively determine whether the condition is due to a hypersecreting adrenal adenoma or unilateral or bilateral hyperplasia.9,10

Treatment of primary hyperaldosteronism depends on the subtype of the disease and involves salt restriction in addition to an aldosterone antagonist (spironolactone or eplerenone in the case of bilateral disease) or surgery (unilateral disease).9,11,12

Secondary hyperaldosteronism

Secondary hyperaldosteronism should be suspected when plasma renin and aldosterone levels are both elevated with a PAC–PRA ratio less than 10.

This pattern is most commonly seen with diuretic use but can also be a consequence of renal artery stenosis or, rarely, a renin-secreting tumor.13 Renal artery stenosis is a common finding in patients with hypertension undergoing cardiac catheterization, which is not surprising as more than 90% of such stenoses are atherosclerotic.7 Renin-secreting tumors are exceedingly rare, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature, and are more common in younger individuals.13

Our patient has low-normal aldosterone and plasma renin

On further testing, this patient’s plasma aldosterone level is 2.55 ng/dL (normal < 15 ng/dL), his plasma renin activity is 0.53 ng/mL/hour (normal 0.2–2.8 ng/mL/hour), and his PAC–PRA ratio is therefore 4.81.

The categories discussed thus far have included primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism, which typically do not present with low to normal levels of both renin and aldosterone. Surreptitious mineralocorticoid use could present in this manner, but is unlikely in this patient, whose medications do not include fludrocortisone.

The low-normal values thus lead to consideration of a third category: apparent mineralocorticoid excess. Diseases in this category such as Cushing disease or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) excess are characterized by increases in corticosteroids so that the potassium depletion, metabolic alkalosis, and hypertension are not a consequence of renin and aldosterone but rather the excess corticosteroids.14

Causes of apparent mineralocorticoid excess

There are several possible causes of mineralocorticoid excess associated with hypertension and hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis not due to renin and aldosterone.

Chronic licorice ingestion in high volumes is one such cause and is thought to result in inhibition of 11B-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase or possibly cortisol oxidase by licorice’s active component, glycyrrhetinic acid. This inhibition results in an inability to convert cortisol to cortisone. The cortisol excess binds to mineralocorticoid receptors, and acting like aldosterone, results in hypertension and hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis as well as feedback inhibition of renin and aldosterone levels.15

Partial hydroxylase deficiencies, though rare, should also be considered as a cause of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hypertension, and, potentially, hirsutism and clitoromegaly in women. They can be diagnosed with elevated levels of 17-ketosteroids and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, both of which, in excess, may act on aldosterone receptors in a manner similar to cortisol.16

Liddle syndrome, a rare autosomal dominant condition, may also present with suppressed levels of both renin and aldosterone. In contrast to the disorders of nonaldosterone mineralocorticoid excess, however, the sodium channel defect in Liddle syndrome is characterized by a primary increase in sodium reabsorption in the collecting tubule and potassium wasting. The resultant volume expansion leads to suppressed renin and aldosterone levels and hypertension with low potassium and elevated bicarbonate concentrations.17

Liddle syndrome is commonly diagnosed in childhood but may go unrecognized due to occasional absence of hypokalemia at presentation. Potassium-sparing diuretics such as amiloride or triamterene are the mainstays of treatment.18

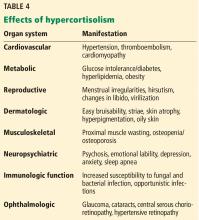

Rates of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality are increased in patients with long-term hypercortisolism, even after plasma concentrations of cortisol are normalized.21

Figure 2 shows the cascade of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

TESTING FOR HYPERCORTISOLISM IN OUR PATIENT

Given the patient’s clinical presentation and laboratory and imaging findings with normal plasma renin and aldosterone levels, a workup for suspected hypercortisolism is initiated.

Initial diagnostic testing for hypercortisolism depends on the degree of clinical suspicion. In those with low probability of the disease, testing should consist of 1 of the following, as a single negative test may be sufficient to rule out the disease:

- 24-hour urinary cortisol levels

- Overnight dexamethasone suppression testing

- Late-night salivary cortisol measurements.

In those with a high index of suspicion, 2 of the aforementioned tests should be performed, as 1 normal result may not be sufficient to exclude the diagnosis.22,23

A 24-hour urinary cortisol collection and overnight dexamethasone suppression test are obtained. His 24-hour urinary free cortisol level is elevated at 6,600 µg (normal 4–100), and suppression testing with 8 mg of dexamethasone (a form of “high-dose” testing)demonstrates only an 8% decline in serum cortisol levels. Cortisol should generally drop more than 90%.

Morning serum cortisol concentration is less than 5 µg/dL (140 nmol/L) in most patients with Cushing disease (ie, a pituitary tumor), and is usually undetectable in normal subjects. Only about 50% of neuroendocrine ACTH-secreting tumors will suppress with this test.

The patient’s clinical presentation, in conjunction with his diagnostic testing, are thus consistent with Cushing syndrome.

CUSHING SYNDROME

Cushing syndrome is most often exogenous or iatrogenic, ie, a result of supraphysiologic doses of glucocorticoids used to treat a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and neoplastic conditions.

Endogenous Cushing syndrome, on the other hand, is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 0.7 to 2.4 cases per million per year. ACTH-dependent causes account for 80% of endogenous Cushing syndrome cases, with ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas (Cushing disease) accounting for 75% to 80% and ectopic ACTH secretion accounting for 15% to 20%. Less than 1% of cases are due to tumors that produce corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome is diagnosed in 20% of endogenous cases and is most commonly caused by a unilateral adrenal tumor. Rare causes of ACTH-independent disease include adrenal carcinoma, McCune-Albright syndrome, and adrenal hyperplasia.24

The patient’s ACTH is high

To determine whether this is an ACTH-dependent or independent process, the next step is to order an ACTH level. His ACTH level is high at 107 pg/mL (normal < 46 pg/mL), confirming the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome.

To find out if this ACTH-dependent process is due to a pituitary adenoma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary is obtained but is normal.

Large masses (> 6 mm) strongly suggest Cushing disease, but these tumors are often small and may be missed even with more advanced imaging techniques. Corticotropin-secreting adenomas arising from normal cells in the pituitary retain some sensitivity to glucocorticoid negative feedback and CRH stimulation, and thus high-dose dexamethasone suppression testing in conjunction with CRH stimulation testing can be used to differentiate Cushing disease from ectopic ACTH secretion.24,25 Both of these tests have poor diagnostic accuracy, however, and thus inferior petrosal sampling remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of Cushing disease.

ACTH-SECRETING TUMORS

5. Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion is most commonly attributed to which of the following tumors?

- Small-cell lung carcinoma

- Pancreatic carcinoma

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma

- Gastrinoma

Severe cases of Cushing syndrome are often attributable to ectopic ACTH secretion due to an underlying malignancy, most commonly small-cell lung carcinoma or neuroendocrine tumors of pulmonary origin. Other causes include pancreatic and thymic neuroendocrine tumors, gastrinomas, and medullary thyroid carcinoma.25,26

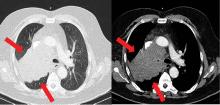

Because most ACTH-producing tumors are intrathoracic, initial imaging in cases of suspected ectopic ACTH secretion should focus on the chest, with CT the usual first choice. Octreotide scintigraphy can also be useful in localizing disease, as many neuroendocrine tumors express somatostatin receptors. Specialized positron-emission tomography scans may also be helpful in tumor identification.24

TREATMENT OF CUSHING SYNDROME DUE TO ECTOPIC ACTH SECRETION

6. Which of the following is most appropriate medical therapy for suppression of cortisol secretion in Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion?

- Spironolactone

- Dexamethasone

- Somatostatin

- Estrogen

- Ketoconazole

Hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, hypertension, psychiatric disturbances, venous thromboembolism, and systemic infections appear to be common in ectopic ACTH syndrome and often correlate with the degree of hypercortisolemia. Severe Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion is an emergency requiring prompt control of cortisol secretion.

First-line treatments include steroidogenesis inhibitors (ketoconazole, metyrapone, etomidate, mitotane) and glucocorticoid receptor antagonists (mifepristone). High-dose spironolactone and eplerenone can also be used to treat the hypertension and hypokalemia associated with mineralocorticoid receptor stimulation. Definitive treatment involves surgical resection, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy when applicable.24,25

After confirmation of the diagnosis, the patient is prescribed ketoconazole and spironolactone, with substantial improvement. He subsequently is started on combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy for his small-cell lung carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

The differential diagnosis for hypokalemia is broad and relies on information obtained during the history and physical examination, followed by interpretation of selected laboratory results. Myriad pathologies in diverse organ systems, eg, diarrhea, renal tubular acidosis, and adrenal disease, may be responsible for a low serum potassium. Further categorizing potassium depletion on the basis of an associated acid-base disturbance, such as metabolic alkalosis, allows one to use an algorithmic approach that can identify specific etiologies responsible for both the potassium and the acid-base disturbances.

Using the spot urine chloride in the setting of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with or without hypertension can narrow the differential diagnosis and allow additional clinical findings to guide clinical problem-solving and decision-making, even for conditions not commonly encountered in routine medical practice.

Obtaining renin and aldosterone measurements in patients with potassium depletion, metabolic alkalosis, high urine chloride excretion, and hypertension permits further categorization into 3 clinical groups: elevated aldosterone and renin (secondary hyperaldosteronism), elevated aldosterone and low renin (primary hyperaldosteronism), or apparent mineralocorticoid excess wherein neither renin nor aldosterone are responsible for the syndrome.

The patient in our case had apparent mineralocorticoid excess as a consequence of an ACTH-producing small-cell carcinoma.

- Martínez-Valles MA, Palafox-Cazarez A, Paredes-Avina JA. Severe hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis and hypertension in a 54 year old male with ectopic ACTH syndrome: a case report. Cases J 2009; 2:6174. doi:10.4076/1757-1626-2-6174

- Fernández-Rodríguez E, Villar-Taibo R, Pinal-Osorio I, et al. Severe hypertension and hypokalemia as first clinical manifestations in ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2008; 52(6):1066–1070. pmid:18820819

- Mani S, Rutecki GW. A patient with altered mental status and an acid-base disturbance. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84(1):27–34. doi:10.3949/ccjm.84a.16042

- Adrogué HJ, Madias NE. Secondary responses to altered acid-base status: the rules of engagement. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21(6):920–923. doi:10.1681/ASN.2009121211

- Huang CL, Kuo E. Mechanism of hypokalemia in magnesium deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18(10):2649–2652. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007070792

- Rose BD. Metabolic alkalosis. In: Clinical Physiology of Acid-Base and Electrolyte Disorders. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division; 1994:515.

- Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, et al; American Heart Association Professional Education Committee. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2008; 117(25):e510–e526. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141

- Koeppen BM, Stanton BA. Physiology of diuretic action. In: Renal Physiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc; 2013:167–178.

- Blumenfeld JD, Sealey JE, Schlussel Y, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary hyperaldosteronism. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121(11):877–885. pmid:7978702

- Kempers MJ, Lenders JW, van Outheusden L, et al. Systematic review: diagnostic procedures to differentiate unilateral from bilateral adrenal abnormality in primary aldosteronism. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151(5):329–337. pmid:19721021

- Karagiannis A, Tziomalos K, Papageorgiou A, et al. Spironolactone versus eplerenone for the treatment of idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008; 9(4):509–515. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.4.509

- Sawka AM, Young WF, Thompson GB, et al. Primary aldosteronism: factors associated with normalization of blood pressure after surgery. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135(4):258–261. pmid:11511140

- Haab F, Duclos JM, Guyenne T, Plouin PF, Corvol P. Renin secreting tumors: diagnosis, conservative surgical approach and long-term results. J Urol 1995; 153(6):1781–1784. pmid:7752315

- Sabbadin C, Armanini D. Syndromes that mimic an excess of mineralocorticoids. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2016; 23(3):231–235. doi:10.1007/s40292-016-0160-5

- Apostolakos JM, Caines LC. Apparent mineralocorticoid excess syndrome: a case of resistant hypertension from licorice tea consumption. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016; 18(10):991–993. doi:10.1111/jch.12841

- Glatt K, Garzon DL, Popovic J. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2005; 10(3):104–114. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6155.2005.00022.x

- Findling JW, Raff H, Hansson JH, Lifton RP. Liddle’s syndrome: prospective genetic screening and suppressed aldosterone secretion in an extended kindred. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82(4):1071–1074. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.4.3862

- Wang C, Chan TK, Yeung RT, Coghlan JP, Scoggins BA, Stockigt JR. The effect of triamterene and sodium intake on renin, aldosterone, and erythrocyte sodium transport in Liddle’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1981; 52(5):1027–1032. doi:10.1210/jcem-52-5-1027

- Torpy DJ, Mullen N, Ilias I, Nieman LK. Association of hypertension and hypokalemia with Cushing’s syndrome caused by ectopic ACTH secretion: a series of 58 cases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002; 970:134–144. pmid:12381548

- Saruta T, Suzuki H, Handa M, Igarashi Y, Kondo K, Senba S. Multiple factors contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension in Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986; 62(2):275–279. doi:10.1210/jcem-62-2-275

- Clayton RN, Jones PW, Reulen RC, et al. Mortality in patients with Cushing’s disease more than 10 years after remission: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4(7):569–576. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30005-5

- Baid SK, Rubino D, Sinaii N, Ramsey S, Frank A, Nieman LK. Specificity of screening tests for Cushing’s syndrome in an overweight and obese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94(10):3857–3864. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-2766

- Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(5):1526–1540. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-0125

- Sharma ST, Nieman LK, Feelders RA. Cushing’s syndrome: epidemiology and developments in disease management. Clin Epidemiol 2015; 7:281–293. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S44336

- Tavares Bello C, van der Poest Clement E, Feelders R. Severe Cushing’s syndrome and bilateral pulmonary nodules: beyond ectopic ACTH. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2017; pii:17–0100. doi:10.1530/EDM-17-0100

- Sathyakumar S, Paul TV, Asha HS, et al. Ectopic Cushing syndrome: a 10-year experience from a tertiary care center in southern India. Endocr Pract 2017; 23(8):907–914. doi:10.4158/EP161677.OR

NOTE: The scenario presented here is partly based on cases reported elsewhere by Martínez-Valles et al1 and Fernández-Rodríguez et al.2

A 55-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with generalized malaise, paresthesias, and severe hypertension. He says he had experienced agitation along with weakness on exertion 24 hours before presentation to the emergency department, with subsequent onset of paresthesias in his lower extremities and perioral area.

He is already known to have mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with a ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)to forced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 70% and an FEV1 85% of predicted. In addition, he was recently diagnosed with diabetes, resistant hypertension requiring maximum doses of 3 agents (a calcium channel blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and a loop diuretic), and hyperlipidemia.

He is a current smoker with a 30-pack-year smoking history. He does not use alcohol. His family history is noncontributory.

ASSESSING ACID-BASE DISORDERS

1. What type of acid-base disorder does this patient have?

- Metabolic acidosis

- Respiratory acidosis

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Respiratory alkalosis

The patient has metabolic alkalosis.

A 5-step approach

1. Acidosis or alkalosis? The patient’s arterial pH is 7.5, which is alkalemic because it is higher than 7.44.

2. Metabolic or respiratory? The primary process in our patient is overwhelmingly metabolic, as his partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2) is slightly elevated, a direction that would cause acidosis, not alkalosis.

3. The anion gap (the serum sodium concentration minus the sum of the chloride and bicarbonate concentrations) is normal at 8 mmol/L (DRG:HYBRiD-XL Immunoassay and Clinical Chemistry Analyzer, reference range 8–16).

4. Is the disturbance compensated? We have determined that this patient has a metabolic alkalemia; the question now is whether there is any compensation for the primary disturbance.

In metabolic alkalosis, the Pco2 may increase by approximately 0.6 mm Hg (range 0.5–0.8) above the nominal normal level of 40 mm Hg for each 1-mmol/L increase in bicarbonate above the nominal normal level of 25 mmol/L.4 If the patient requires oxygen, the calculation may be unreliable, however, as hypoxemia may have an overriding influence on respiratory drive.

Patients with chronically high Pco2 levels such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can become accustomed to high carbon dioxide levels and lose their hyper-

capnic respiratory drive. Giving oxygen supplementation is thought to decrease respiratory drive in these patients, so that they will breathe slower and retain more carbon dioxide. There is some degree of respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis that occurs by breathing less, though it is limited overall—even in very alkalotic patients, breathing less results in CO2 retention, which, by displacing O2 molecules in the alveoli, will in turn result in hypoxia. The brain then senses the hypoxia and makes one breathe faster, thereby limiting this compensation.

This patient’s serum bicarbonate level is 40 mmol/L, or 15 mmol/L higher than the nominal normal level. If he is compensating, his Pco2 should be 40 + (15 × 0.6) = 49 mm Hg, and in fact it is 51 mm Hg, which is within the normal range of expected compensation (47.5–52 mm Hg). Therefore, yes, he is compensating for the primary disturbance.

5. In metabolic acidosis, is there a delta gap? As our patient has metabolic alkalosis, not acidosis, this question does not apply in this case.

WHICH TEST TO FIND THE CAUSE?

2. Which is the best test to order next to determine the cause of this patient’s hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis?

- Serum magnesium level

- Spot urine chloride

- Renal ultrasonography

- 24-hour urine collection for sodium, potassium, and chloride

The patient’s loop diuretic is withheld for 12 hours and a spot urine chloride is obtained, which is reported as 44 mmol/L. This high value suggests that a volume-independent hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis is present with potassium depletion.

As for the other answer choices:

Serum magnesium. Though hypomagnesemia can cause hypokalemia due to lack of inhibition of renal outer medullary potassium channels and subsequent increased excretion of potassium in the apical tubular membrane, it is not independently associated with acid-base disturbances.5

Renal ultrasonography gives information about structural kidney disease but is of limited utility in identifying the cause of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis.

A 24-hour urine collection is unnecessary in this setting and would ultimately result in delay in diagnosis, as spot urine chloride is a more efficient means of rapidly distinguishing volume-responsive vs volume-independent causes of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis.6

IS HIS HYPERTENSION SECONDARY? IF SO, WHAT IS THE CAUSE?

Several features of this case suggest that the patient’s hypertension is secondary rather than primary. It is of recent onset. The patient’s family history is noncontributory, and his hypertension is resistant to the use of maximum doses of 3 antihypertensive agents.

3. Which of the following causes of secondary hypertension is not commonly associated with hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis?

- Hyperaldosteronism

- Liddle syndrome

- Cushing syndrome

- Renal parenchymal disease

- Chronic licorice ingestion

Renal parenchymal disease is a cause of resistant hypertension, but it is not characterized by metabolic alkalosis, hypokalemia, and elevated urine chloride,7 while the others listed here—hyperaldosteronism, Liddle syndrome, Cushing syndrome, and chronic licorice ingestion—are. Other common causes of resistant hypertension without these metabolic abnormalities include obstructive sleep apnea, alcohol abuse, and nonadherence to treatment.

While treatment of hypertension with loop diuretics can result in hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis due to the effect of these drugs on potassium reabsorption in the loop of Henle, the patient’s hypokalemia persisted after this agent was withdrawn.8

Causes of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with and without hypertension are further delineated in Figure 1.

Additional diagnostic testing: Plasma renin and plasma aldosterone

At this juncture, the differential diagnosis for this patient’s potassium depletion, metabolic alkalosis, high urine chloride, and hypertension has been narrowed to primary or secondary hyperaldosteronism, surreptitious mineralocorticoid ingestion, Cushing syndrome, licorice ingestion, Liddle syndrome, or one of the 3 hydroxylase deficiencies (11-, 17-, and 21-) (Figure 1).

Although clues in the history, physical examination, and imaging may suggest a specific cause of his abnormal laboratory values, the next step in the diagnostic workup is to measure the plasma renin and aldosterone levels (Table 3).

HYPERALDOSTERONISM

4. Hyperaldosteronism is associated with which of the following patterns of renin and aldosterone values?

- High renin, high aldosterone, normal ratio of plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) to plasma renin activity (PRA)

- Low renin, low aldosterone, normal PAC–PRA ratio

- Low renin, high aldosterone, high PAC–PRA ratio

- High renin, low aldosterone, low PAC–PRA ratio

The pattern of low renin, high aldosterone, and high PAC–PRA ratio is associated with hyperaldosteronism.

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Primary hyperaldosteronism is one of the most common causes of resistant hypertension and is underappreciated, being diagnosed in up to 20% of patients referred to hypertension specialty clinics.7 Potassium levels may be normal, likely contributing to its lack of recognition in this target population.

Primary hyperaldosteronism should be suspected in patients who have a plasma aldosterone PAC–PRA ratio greater than 20 with elevated plasma aldosterone concentrations

(> 15 ng/dL).

Persistently elevated aldosterone levels in the setting of elevated plasma volume is proof that aldosterone secretion is independent of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, and therefore is autonomous (secondary to adrenal tumor or hyperplasia). Further testing in the form of oral salt loading, saline infusion, or fludrocortisone (a sodium-retaining steroid) administration is thus required to confirm inappropriate, autonomous aldosterone secretion.9

After establishing the diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism, one should determine the subtype (ie, due to an adrenal carcinoma, unilateral hypersecreting adenoma, or unilateral or bilateral hyperplasia). Further testing includes adrenal computed tomography (CT) to rule out adrenal carcinomas, which are suspected with adenomas larger than 4 cm. Though part of the diagnostic workup, CT as a means of confirmational testing alone does not preclude the possibility of bilateral adrenal hyperplasia in some patients, even in the presence of an adrenal adenoma. For this reason, adrenal venous sampling is required to definitively determine whether the condition is due to a hypersecreting adrenal adenoma or unilateral or bilateral hyperplasia.9,10

Treatment of primary hyperaldosteronism depends on the subtype of the disease and involves salt restriction in addition to an aldosterone antagonist (spironolactone or eplerenone in the case of bilateral disease) or surgery (unilateral disease).9,11,12

Secondary hyperaldosteronism

Secondary hyperaldosteronism should be suspected when plasma renin and aldosterone levels are both elevated with a PAC–PRA ratio less than 10.

This pattern is most commonly seen with diuretic use but can also be a consequence of renal artery stenosis or, rarely, a renin-secreting tumor.13 Renal artery stenosis is a common finding in patients with hypertension undergoing cardiac catheterization, which is not surprising as more than 90% of such stenoses are atherosclerotic.7 Renin-secreting tumors are exceedingly rare, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature, and are more common in younger individuals.13

Our patient has low-normal aldosterone and plasma renin

On further testing, this patient’s plasma aldosterone level is 2.55 ng/dL (normal < 15 ng/dL), his plasma renin activity is 0.53 ng/mL/hour (normal 0.2–2.8 ng/mL/hour), and his PAC–PRA ratio is therefore 4.81.

The categories discussed thus far have included primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism, which typically do not present with low to normal levels of both renin and aldosterone. Surreptitious mineralocorticoid use could present in this manner, but is unlikely in this patient, whose medications do not include fludrocortisone.

The low-normal values thus lead to consideration of a third category: apparent mineralocorticoid excess. Diseases in this category such as Cushing disease or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) excess are characterized by increases in corticosteroids so that the potassium depletion, metabolic alkalosis, and hypertension are not a consequence of renin and aldosterone but rather the excess corticosteroids.14

Causes of apparent mineralocorticoid excess

There are several possible causes of mineralocorticoid excess associated with hypertension and hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis not due to renin and aldosterone.

Chronic licorice ingestion in high volumes is one such cause and is thought to result in inhibition of 11B-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase or possibly cortisol oxidase by licorice’s active component, glycyrrhetinic acid. This inhibition results in an inability to convert cortisol to cortisone. The cortisol excess binds to mineralocorticoid receptors, and acting like aldosterone, results in hypertension and hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis as well as feedback inhibition of renin and aldosterone levels.15

Partial hydroxylase deficiencies, though rare, should also be considered as a cause of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hypertension, and, potentially, hirsutism and clitoromegaly in women. They can be diagnosed with elevated levels of 17-ketosteroids and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, both of which, in excess, may act on aldosterone receptors in a manner similar to cortisol.16

Liddle syndrome, a rare autosomal dominant condition, may also present with suppressed levels of both renin and aldosterone. In contrast to the disorders of nonaldosterone mineralocorticoid excess, however, the sodium channel defect in Liddle syndrome is characterized by a primary increase in sodium reabsorption in the collecting tubule and potassium wasting. The resultant volume expansion leads to suppressed renin and aldosterone levels and hypertension with low potassium and elevated bicarbonate concentrations.17

Liddle syndrome is commonly diagnosed in childhood but may go unrecognized due to occasional absence of hypokalemia at presentation. Potassium-sparing diuretics such as amiloride or triamterene are the mainstays of treatment.18

Rates of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality are increased in patients with long-term hypercortisolism, even after plasma concentrations of cortisol are normalized.21

Figure 2 shows the cascade of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

TESTING FOR HYPERCORTISOLISM IN OUR PATIENT

Given the patient’s clinical presentation and laboratory and imaging findings with normal plasma renin and aldosterone levels, a workup for suspected hypercortisolism is initiated.

Initial diagnostic testing for hypercortisolism depends on the degree of clinical suspicion. In those with low probability of the disease, testing should consist of 1 of the following, as a single negative test may be sufficient to rule out the disease:

- 24-hour urinary cortisol levels

- Overnight dexamethasone suppression testing

- Late-night salivary cortisol measurements.

In those with a high index of suspicion, 2 of the aforementioned tests should be performed, as 1 normal result may not be sufficient to exclude the diagnosis.22,23

A 24-hour urinary cortisol collection and overnight dexamethasone suppression test are obtained. His 24-hour urinary free cortisol level is elevated at 6,600 µg (normal 4–100), and suppression testing with 8 mg of dexamethasone (a form of “high-dose” testing)demonstrates only an 8% decline in serum cortisol levels. Cortisol should generally drop more than 90%.

Morning serum cortisol concentration is less than 5 µg/dL (140 nmol/L) in most patients with Cushing disease (ie, a pituitary tumor), and is usually undetectable in normal subjects. Only about 50% of neuroendocrine ACTH-secreting tumors will suppress with this test.

The patient’s clinical presentation, in conjunction with his diagnostic testing, are thus consistent with Cushing syndrome.

CUSHING SYNDROME

Cushing syndrome is most often exogenous or iatrogenic, ie, a result of supraphysiologic doses of glucocorticoids used to treat a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and neoplastic conditions.

Endogenous Cushing syndrome, on the other hand, is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 0.7 to 2.4 cases per million per year. ACTH-dependent causes account for 80% of endogenous Cushing syndrome cases, with ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas (Cushing disease) accounting for 75% to 80% and ectopic ACTH secretion accounting for 15% to 20%. Less than 1% of cases are due to tumors that produce corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome is diagnosed in 20% of endogenous cases and is most commonly caused by a unilateral adrenal tumor. Rare causes of ACTH-independent disease include adrenal carcinoma, McCune-Albright syndrome, and adrenal hyperplasia.24

The patient’s ACTH is high

To determine whether this is an ACTH-dependent or independent process, the next step is to order an ACTH level. His ACTH level is high at 107 pg/mL (normal < 46 pg/mL), confirming the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome.

To find out if this ACTH-dependent process is due to a pituitary adenoma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary is obtained but is normal.

Large masses (> 6 mm) strongly suggest Cushing disease, but these tumors are often small and may be missed even with more advanced imaging techniques. Corticotropin-secreting adenomas arising from normal cells in the pituitary retain some sensitivity to glucocorticoid negative feedback and CRH stimulation, and thus high-dose dexamethasone suppression testing in conjunction with CRH stimulation testing can be used to differentiate Cushing disease from ectopic ACTH secretion.24,25 Both of these tests have poor diagnostic accuracy, however, and thus inferior petrosal sampling remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of Cushing disease.

ACTH-SECRETING TUMORS

5. Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion is most commonly attributed to which of the following tumors?

- Small-cell lung carcinoma

- Pancreatic carcinoma

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma

- Gastrinoma

Severe cases of Cushing syndrome are often attributable to ectopic ACTH secretion due to an underlying malignancy, most commonly small-cell lung carcinoma or neuroendocrine tumors of pulmonary origin. Other causes include pancreatic and thymic neuroendocrine tumors, gastrinomas, and medullary thyroid carcinoma.25,26

Because most ACTH-producing tumors are intrathoracic, initial imaging in cases of suspected ectopic ACTH secretion should focus on the chest, with CT the usual first choice. Octreotide scintigraphy can also be useful in localizing disease, as many neuroendocrine tumors express somatostatin receptors. Specialized positron-emission tomography scans may also be helpful in tumor identification.24

TREATMENT OF CUSHING SYNDROME DUE TO ECTOPIC ACTH SECRETION

6. Which of the following is most appropriate medical therapy for suppression of cortisol secretion in Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion?

- Spironolactone

- Dexamethasone

- Somatostatin

- Estrogen

- Ketoconazole

Hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, hypertension, psychiatric disturbances, venous thromboembolism, and systemic infections appear to be common in ectopic ACTH syndrome and often correlate with the degree of hypercortisolemia. Severe Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion is an emergency requiring prompt control of cortisol secretion.

First-line treatments include steroidogenesis inhibitors (ketoconazole, metyrapone, etomidate, mitotane) and glucocorticoid receptor antagonists (mifepristone). High-dose spironolactone and eplerenone can also be used to treat the hypertension and hypokalemia associated with mineralocorticoid receptor stimulation. Definitive treatment involves surgical resection, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy when applicable.24,25

After confirmation of the diagnosis, the patient is prescribed ketoconazole and spironolactone, with substantial improvement. He subsequently is started on combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy for his small-cell lung carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

The differential diagnosis for hypokalemia is broad and relies on information obtained during the history and physical examination, followed by interpretation of selected laboratory results. Myriad pathologies in diverse organ systems, eg, diarrhea, renal tubular acidosis, and adrenal disease, may be responsible for a low serum potassium. Further categorizing potassium depletion on the basis of an associated acid-base disturbance, such as metabolic alkalosis, allows one to use an algorithmic approach that can identify specific etiologies responsible for both the potassium and the acid-base disturbances.

Using the spot urine chloride in the setting of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with or without hypertension can narrow the differential diagnosis and allow additional clinical findings to guide clinical problem-solving and decision-making, even for conditions not commonly encountered in routine medical practice.

Obtaining renin and aldosterone measurements in patients with potassium depletion, metabolic alkalosis, high urine chloride excretion, and hypertension permits further categorization into 3 clinical groups: elevated aldosterone and renin (secondary hyperaldosteronism), elevated aldosterone and low renin (primary hyperaldosteronism), or apparent mineralocorticoid excess wherein neither renin nor aldosterone are responsible for the syndrome.

The patient in our case had apparent mineralocorticoid excess as a consequence of an ACTH-producing small-cell carcinoma.

NOTE: The scenario presented here is partly based on cases reported elsewhere by Martínez-Valles et al1 and Fernández-Rodríguez et al.2

A 55-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with generalized malaise, paresthesias, and severe hypertension. He says he had experienced agitation along with weakness on exertion 24 hours before presentation to the emergency department, with subsequent onset of paresthesias in his lower extremities and perioral area.

He is already known to have mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with a ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)to forced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 70% and an FEV1 85% of predicted. In addition, he was recently diagnosed with diabetes, resistant hypertension requiring maximum doses of 3 agents (a calcium channel blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and a loop diuretic), and hyperlipidemia.

He is a current smoker with a 30-pack-year smoking history. He does not use alcohol. His family history is noncontributory.

ASSESSING ACID-BASE DISORDERS

1. What type of acid-base disorder does this patient have?

- Metabolic acidosis

- Respiratory acidosis

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Respiratory alkalosis

The patient has metabolic alkalosis.

A 5-step approach

1. Acidosis or alkalosis? The patient’s arterial pH is 7.5, which is alkalemic because it is higher than 7.44.

2. Metabolic or respiratory? The primary process in our patient is overwhelmingly metabolic, as his partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2) is slightly elevated, a direction that would cause acidosis, not alkalosis.

3. The anion gap (the serum sodium concentration minus the sum of the chloride and bicarbonate concentrations) is normal at 8 mmol/L (DRG:HYBRiD-XL Immunoassay and Clinical Chemistry Analyzer, reference range 8–16).

4. Is the disturbance compensated? We have determined that this patient has a metabolic alkalemia; the question now is whether there is any compensation for the primary disturbance.

In metabolic alkalosis, the Pco2 may increase by approximately 0.6 mm Hg (range 0.5–0.8) above the nominal normal level of 40 mm Hg for each 1-mmol/L increase in bicarbonate above the nominal normal level of 25 mmol/L.4 If the patient requires oxygen, the calculation may be unreliable, however, as hypoxemia may have an overriding influence on respiratory drive.

Patients with chronically high Pco2 levels such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can become accustomed to high carbon dioxide levels and lose their hyper-

capnic respiratory drive. Giving oxygen supplementation is thought to decrease respiratory drive in these patients, so that they will breathe slower and retain more carbon dioxide. There is some degree of respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis that occurs by breathing less, though it is limited overall—even in very alkalotic patients, breathing less results in CO2 retention, which, by displacing O2 molecules in the alveoli, will in turn result in hypoxia. The brain then senses the hypoxia and makes one breathe faster, thereby limiting this compensation.

This patient’s serum bicarbonate level is 40 mmol/L, or 15 mmol/L higher than the nominal normal level. If he is compensating, his Pco2 should be 40 + (15 × 0.6) = 49 mm Hg, and in fact it is 51 mm Hg, which is within the normal range of expected compensation (47.5–52 mm Hg). Therefore, yes, he is compensating for the primary disturbance.

5. In metabolic acidosis, is there a delta gap? As our patient has metabolic alkalosis, not acidosis, this question does not apply in this case.

WHICH TEST TO FIND THE CAUSE?

2. Which is the best test to order next to determine the cause of this patient’s hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis?

- Serum magnesium level

- Spot urine chloride

- Renal ultrasonography

- 24-hour urine collection for sodium, potassium, and chloride

The patient’s loop diuretic is withheld for 12 hours and a spot urine chloride is obtained, which is reported as 44 mmol/L. This high value suggests that a volume-independent hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis is present with potassium depletion.

As for the other answer choices:

Serum magnesium. Though hypomagnesemia can cause hypokalemia due to lack of inhibition of renal outer medullary potassium channels and subsequent increased excretion of potassium in the apical tubular membrane, it is not independently associated with acid-base disturbances.5

Renal ultrasonography gives information about structural kidney disease but is of limited utility in identifying the cause of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis.

A 24-hour urine collection is unnecessary in this setting and would ultimately result in delay in diagnosis, as spot urine chloride is a more efficient means of rapidly distinguishing volume-responsive vs volume-independent causes of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis.6

IS HIS HYPERTENSION SECONDARY? IF SO, WHAT IS THE CAUSE?

Several features of this case suggest that the patient’s hypertension is secondary rather than primary. It is of recent onset. The patient’s family history is noncontributory, and his hypertension is resistant to the use of maximum doses of 3 antihypertensive agents.

3. Which of the following causes of secondary hypertension is not commonly associated with hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis?

- Hyperaldosteronism

- Liddle syndrome

- Cushing syndrome

- Renal parenchymal disease

- Chronic licorice ingestion

Renal parenchymal disease is a cause of resistant hypertension, but it is not characterized by metabolic alkalosis, hypokalemia, and elevated urine chloride,7 while the others listed here—hyperaldosteronism, Liddle syndrome, Cushing syndrome, and chronic licorice ingestion—are. Other common causes of resistant hypertension without these metabolic abnormalities include obstructive sleep apnea, alcohol abuse, and nonadherence to treatment.