User login

Gap in care: Female patients with incontinence

LAS VEGAS – A pelvic surgeon brought a bold message to a gathering of gynecologists: There’s a great gap in American care for pelvic floor disorders such as urinary incontinence, and they’re the right physicians to make a difference by treating these common conditions.

“There are never going to be enough specialists to deal with these problems. This is a natural progression for many of you,” said urogynecologist and pelvic surgeon Mickey M. Karram, MD, in a joint presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium. In fact, he said, “there’s so much disease out there to fix that you may become more overwhelmed.”

Dr. Karram, who has offices in Cincinnati, Beverly Hills, and Orange County, Calif., spoke about female urinary incontinence with obstetrician-gynecologist Beri M. Ridgeway, MD, of Cleveland Clinic. They offered these tips:

Test for stress incontinence

Dr. Karram recommends using a “quick and easy” cystometrogram (CMG) test to “corroborate or refute what the patient thinks is going on” in regard to urinary function. “With this simple test, you’ll get a clear understanding of sensation [to urinate] and of what their fullness and capacity numbers are,” he said. And if you have the patient cough or strain during the test, “you should be able to duplicate a sign of stress incontinence 90% of the time.”

If patients don’t leak when they take this test, there may be another problem such as overactive bladder, a condition that can’t be duplicated via the test, he said.

Ask the right questions

When it comes to identifying when they have urinary difficulties, some patients “say yes to every question we ask,” said Dr. Ridgeway, and they may not be able to distinguish between urgency and leakage.

A better approach is to ask women to provide specific examples of when they have continence issues, she said. It’s also useful to ask patients about what bothers them the most if they have multiple symptoms: Is it urgency (“Gotta go; gotta go”)? Leakage during certain situations like coughing and laughing? “That helps me decide how to go about treating them first and foremost,” she said. “It doesn’t mean you won’t treat both [problems], but it really gives you a reference point of where to start.”

Research suggests that women tend to be more bothered by urge incontinence than stress incontinence, she said, because they can regulate their activities or avoid the stress form.

Beware of acute incontinence cases

“If a woman walks in and says ‘Everything was great until a week or two ago, but now I’m living in pads,’ it could be a fecal impaction or a pelvic mass,” Dr. Karram said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Discuss the many treatment options

In some cases of incontinence, Dr. Ridgeway said she’ll mention “the array of treatment options, such as pelvic floor physical therapy, bladder retraining, vaginal estrogen, medications, and Botox.”

She added: “I explain that we’ll work together, and sometimes it will take a couple tries, or we’ll try a couple things at once.”

Dr. Ridgeway disclosed consulting for Coloplast and serving as an independent contractor (legal) for Ethicon. Dr. Karram disclosed speaking for Allergan, Astellas Pharma, Coloplast, and Cynosure/Hologic; consulting for Coloplast and Cynosure/Hologic; and receiving royalties from BihlerMed.

LAS VEGAS – A pelvic surgeon brought a bold message to a gathering of gynecologists: There’s a great gap in American care for pelvic floor disorders such as urinary incontinence, and they’re the right physicians to make a difference by treating these common conditions.

“There are never going to be enough specialists to deal with these problems. This is a natural progression for many of you,” said urogynecologist and pelvic surgeon Mickey M. Karram, MD, in a joint presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium. In fact, he said, “there’s so much disease out there to fix that you may become more overwhelmed.”

Dr. Karram, who has offices in Cincinnati, Beverly Hills, and Orange County, Calif., spoke about female urinary incontinence with obstetrician-gynecologist Beri M. Ridgeway, MD, of Cleveland Clinic. They offered these tips:

Test for stress incontinence

Dr. Karram recommends using a “quick and easy” cystometrogram (CMG) test to “corroborate or refute what the patient thinks is going on” in regard to urinary function. “With this simple test, you’ll get a clear understanding of sensation [to urinate] and of what their fullness and capacity numbers are,” he said. And if you have the patient cough or strain during the test, “you should be able to duplicate a sign of stress incontinence 90% of the time.”

If patients don’t leak when they take this test, there may be another problem such as overactive bladder, a condition that can’t be duplicated via the test, he said.

Ask the right questions

When it comes to identifying when they have urinary difficulties, some patients “say yes to every question we ask,” said Dr. Ridgeway, and they may not be able to distinguish between urgency and leakage.

A better approach is to ask women to provide specific examples of when they have continence issues, she said. It’s also useful to ask patients about what bothers them the most if they have multiple symptoms: Is it urgency (“Gotta go; gotta go”)? Leakage during certain situations like coughing and laughing? “That helps me decide how to go about treating them first and foremost,” she said. “It doesn’t mean you won’t treat both [problems], but it really gives you a reference point of where to start.”

Research suggests that women tend to be more bothered by urge incontinence than stress incontinence, she said, because they can regulate their activities or avoid the stress form.

Beware of acute incontinence cases

“If a woman walks in and says ‘Everything was great until a week or two ago, but now I’m living in pads,’ it could be a fecal impaction or a pelvic mass,” Dr. Karram said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Discuss the many treatment options

In some cases of incontinence, Dr. Ridgeway said she’ll mention “the array of treatment options, such as pelvic floor physical therapy, bladder retraining, vaginal estrogen, medications, and Botox.”

She added: “I explain that we’ll work together, and sometimes it will take a couple tries, or we’ll try a couple things at once.”

Dr. Ridgeway disclosed consulting for Coloplast and serving as an independent contractor (legal) for Ethicon. Dr. Karram disclosed speaking for Allergan, Astellas Pharma, Coloplast, and Cynosure/Hologic; consulting for Coloplast and Cynosure/Hologic; and receiving royalties from BihlerMed.

LAS VEGAS – A pelvic surgeon brought a bold message to a gathering of gynecologists: There’s a great gap in American care for pelvic floor disorders such as urinary incontinence, and they’re the right physicians to make a difference by treating these common conditions.

“There are never going to be enough specialists to deal with these problems. This is a natural progression for many of you,” said urogynecologist and pelvic surgeon Mickey M. Karram, MD, in a joint presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium. In fact, he said, “there’s so much disease out there to fix that you may become more overwhelmed.”

Dr. Karram, who has offices in Cincinnati, Beverly Hills, and Orange County, Calif., spoke about female urinary incontinence with obstetrician-gynecologist Beri M. Ridgeway, MD, of Cleveland Clinic. They offered these tips:

Test for stress incontinence

Dr. Karram recommends using a “quick and easy” cystometrogram (CMG) test to “corroborate or refute what the patient thinks is going on” in regard to urinary function. “With this simple test, you’ll get a clear understanding of sensation [to urinate] and of what their fullness and capacity numbers are,” he said. And if you have the patient cough or strain during the test, “you should be able to duplicate a sign of stress incontinence 90% of the time.”

If patients don’t leak when they take this test, there may be another problem such as overactive bladder, a condition that can’t be duplicated via the test, he said.

Ask the right questions

When it comes to identifying when they have urinary difficulties, some patients “say yes to every question we ask,” said Dr. Ridgeway, and they may not be able to distinguish between urgency and leakage.

A better approach is to ask women to provide specific examples of when they have continence issues, she said. It’s also useful to ask patients about what bothers them the most if they have multiple symptoms: Is it urgency (“Gotta go; gotta go”)? Leakage during certain situations like coughing and laughing? “That helps me decide how to go about treating them first and foremost,” she said. “It doesn’t mean you won’t treat both [problems], but it really gives you a reference point of where to start.”

Research suggests that women tend to be more bothered by urge incontinence than stress incontinence, she said, because they can regulate their activities or avoid the stress form.

Beware of acute incontinence cases

“If a woman walks in and says ‘Everything was great until a week or two ago, but now I’m living in pads,’ it could be a fecal impaction or a pelvic mass,” Dr. Karram said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Discuss the many treatment options

In some cases of incontinence, Dr. Ridgeway said she’ll mention “the array of treatment options, such as pelvic floor physical therapy, bladder retraining, vaginal estrogen, medications, and Botox.”

She added: “I explain that we’ll work together, and sometimes it will take a couple tries, or we’ll try a couple things at once.”

Dr. Ridgeway disclosed consulting for Coloplast and serving as an independent contractor (legal) for Ethicon. Dr. Karram disclosed speaking for Allergan, Astellas Pharma, Coloplast, and Cynosure/Hologic; consulting for Coloplast and Cynosure/Hologic; and receiving royalties from BihlerMed.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAGS

When is it appropriate to remove ovaries in hysterectomy?

LAS VEGAS – The removal of both ovaries during hysterectomy – bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) – has declined sharply in popularity as physicians have become more aware of its risks.

Still, “we’re still seeing a relatively high rate of inappropriate BSO,” Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, said, despite “the many benefits of ovarian conservation. Strong consideration should be made for maintaining normal ovaries in premenopausal women who are not at higher genetic risk of ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Nickles Fader, director of the Kelly gynecologic oncology service and the director of the center for rare gynecologic cancers at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, who spoke at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium, urged gynecologists to understand the data about ovarian conservation in hysterectomy and carefully counsel patients.

“We can counsel patients with 100% certainty that BSO absolutely reduces ovarian and fallopian tube cancer rates. That’s a given,” she said. “Women get very excited about that, but you’ve got to be careful to counsel them about the flip side: The overall benefit may not be there when you consider the other morbidity and mortality that may occur because of this removal.”

As she noted, multiple retrospective, prospective, and observational studies have linked ovary removal to a variety of heightened risks, especially on the cardiac front. She highlighted a 2009 study of nearly 30,000 nurses who’d undergone hysterectomy for benign disease, about which the authors wrote that, “compared with ovarian conservation, bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease is associated with a decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer but an increased risk of all-cause mortality, fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, and lung cancer.” No age group gained a survival benefit from oophorectomy (Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113[5]:1027-37 ).

Meanwhile, over the past decade, the “pendulum has swung” toward ovary conservation, at least in premenopausal women, Dr. Nickles Fader said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

A 2016 analysis of health statistics in five U.S. Eastern and Midwestern states found that, rates of hospital-based, hysterectomy-alone procedures grew by 15% from 2005 to 2013, while rates of oophorectomy alone and hysterectomy/oophorectomy combination procedures declined by 12% and 29%, respectively.

Still, Dr. Nickles Fader said, as many as 60% of hysterectomies are still performed in conjunction with oophorectomy.

Ovary removal, of course, can be appropriate when patients are at risk of ovarian cancer. Hereditary ovarian cancer accounts for up to 25% of epithelial ovarian cancer, she said, and research suggests that risk-reducing surgery is an effective preventative approach when high-penetrance genes are present. However, the value of the surgery is less clear in regard to moderate-penetrance genes.

Dr. Nickles Fader pointed to guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that specify genes and syndromes that should trigger risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, or hysterectomy and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy after childbirth.

Researchers are exploring salpingectomy – fallopian tube removal – as a possible replacement for oophorectomy. Dr. Nickles Fader highlighted a small pilot study published in 2018 that reported “BRCA mutation carriers who underwent bilateral salpingectomy had no intraoperative complications, were satisfied with their procedure choice, and had decreased cancer worry and anxiety after the procedure.”

Moving forward, she said, research will provide more insight into preventative options such as removing fallopian tubes alone instead of ovaries. “We’re starting to learn, and will probably know in the next 10-15 years, whether oophorectomy is necessary for all high-risk and moderate-risk women or if we can get away with removing their tubes and giving them the maximal health benefits of ovarian conservation.”

Dr. Nickles Fader reported consulting for Ethicon Endosurgery.

LAS VEGAS – The removal of both ovaries during hysterectomy – bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) – has declined sharply in popularity as physicians have become more aware of its risks.

Still, “we’re still seeing a relatively high rate of inappropriate BSO,” Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, said, despite “the many benefits of ovarian conservation. Strong consideration should be made for maintaining normal ovaries in premenopausal women who are not at higher genetic risk of ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Nickles Fader, director of the Kelly gynecologic oncology service and the director of the center for rare gynecologic cancers at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, who spoke at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium, urged gynecologists to understand the data about ovarian conservation in hysterectomy and carefully counsel patients.

“We can counsel patients with 100% certainty that BSO absolutely reduces ovarian and fallopian tube cancer rates. That’s a given,” she said. “Women get very excited about that, but you’ve got to be careful to counsel them about the flip side: The overall benefit may not be there when you consider the other morbidity and mortality that may occur because of this removal.”

As she noted, multiple retrospective, prospective, and observational studies have linked ovary removal to a variety of heightened risks, especially on the cardiac front. She highlighted a 2009 study of nearly 30,000 nurses who’d undergone hysterectomy for benign disease, about which the authors wrote that, “compared with ovarian conservation, bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease is associated with a decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer but an increased risk of all-cause mortality, fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, and lung cancer.” No age group gained a survival benefit from oophorectomy (Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113[5]:1027-37 ).

Meanwhile, over the past decade, the “pendulum has swung” toward ovary conservation, at least in premenopausal women, Dr. Nickles Fader said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

A 2016 analysis of health statistics in five U.S. Eastern and Midwestern states found that, rates of hospital-based, hysterectomy-alone procedures grew by 15% from 2005 to 2013, while rates of oophorectomy alone and hysterectomy/oophorectomy combination procedures declined by 12% and 29%, respectively.

Still, Dr. Nickles Fader said, as many as 60% of hysterectomies are still performed in conjunction with oophorectomy.

Ovary removal, of course, can be appropriate when patients are at risk of ovarian cancer. Hereditary ovarian cancer accounts for up to 25% of epithelial ovarian cancer, she said, and research suggests that risk-reducing surgery is an effective preventative approach when high-penetrance genes are present. However, the value of the surgery is less clear in regard to moderate-penetrance genes.

Dr. Nickles Fader pointed to guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that specify genes and syndromes that should trigger risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, or hysterectomy and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy after childbirth.

Researchers are exploring salpingectomy – fallopian tube removal – as a possible replacement for oophorectomy. Dr. Nickles Fader highlighted a small pilot study published in 2018 that reported “BRCA mutation carriers who underwent bilateral salpingectomy had no intraoperative complications, were satisfied with their procedure choice, and had decreased cancer worry and anxiety after the procedure.”

Moving forward, she said, research will provide more insight into preventative options such as removing fallopian tubes alone instead of ovaries. “We’re starting to learn, and will probably know in the next 10-15 years, whether oophorectomy is necessary for all high-risk and moderate-risk women or if we can get away with removing their tubes and giving them the maximal health benefits of ovarian conservation.”

Dr. Nickles Fader reported consulting for Ethicon Endosurgery.

LAS VEGAS – The removal of both ovaries during hysterectomy – bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) – has declined sharply in popularity as physicians have become more aware of its risks.

Still, “we’re still seeing a relatively high rate of inappropriate BSO,” Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, said, despite “the many benefits of ovarian conservation. Strong consideration should be made for maintaining normal ovaries in premenopausal women who are not at higher genetic risk of ovarian cancer.”

Dr. Nickles Fader, director of the Kelly gynecologic oncology service and the director of the center for rare gynecologic cancers at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, who spoke at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium, urged gynecologists to understand the data about ovarian conservation in hysterectomy and carefully counsel patients.

“We can counsel patients with 100% certainty that BSO absolutely reduces ovarian and fallopian tube cancer rates. That’s a given,” she said. “Women get very excited about that, but you’ve got to be careful to counsel them about the flip side: The overall benefit may not be there when you consider the other morbidity and mortality that may occur because of this removal.”

As she noted, multiple retrospective, prospective, and observational studies have linked ovary removal to a variety of heightened risks, especially on the cardiac front. She highlighted a 2009 study of nearly 30,000 nurses who’d undergone hysterectomy for benign disease, about which the authors wrote that, “compared with ovarian conservation, bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease is associated with a decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer but an increased risk of all-cause mortality, fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, and lung cancer.” No age group gained a survival benefit from oophorectomy (Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113[5]:1027-37 ).

Meanwhile, over the past decade, the “pendulum has swung” toward ovary conservation, at least in premenopausal women, Dr. Nickles Fader said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

A 2016 analysis of health statistics in five U.S. Eastern and Midwestern states found that, rates of hospital-based, hysterectomy-alone procedures grew by 15% from 2005 to 2013, while rates of oophorectomy alone and hysterectomy/oophorectomy combination procedures declined by 12% and 29%, respectively.

Still, Dr. Nickles Fader said, as many as 60% of hysterectomies are still performed in conjunction with oophorectomy.

Ovary removal, of course, can be appropriate when patients are at risk of ovarian cancer. Hereditary ovarian cancer accounts for up to 25% of epithelial ovarian cancer, she said, and research suggests that risk-reducing surgery is an effective preventative approach when high-penetrance genes are present. However, the value of the surgery is less clear in regard to moderate-penetrance genes.

Dr. Nickles Fader pointed to guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that specify genes and syndromes that should trigger risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, or hysterectomy and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy after childbirth.

Researchers are exploring salpingectomy – fallopian tube removal – as a possible replacement for oophorectomy. Dr. Nickles Fader highlighted a small pilot study published in 2018 that reported “BRCA mutation carriers who underwent bilateral salpingectomy had no intraoperative complications, were satisfied with their procedure choice, and had decreased cancer worry and anxiety after the procedure.”

Moving forward, she said, research will provide more insight into preventative options such as removing fallopian tubes alone instead of ovaries. “We’re starting to learn, and will probably know in the next 10-15 years, whether oophorectomy is necessary for all high-risk and moderate-risk women or if we can get away with removing their tubes and giving them the maximal health benefits of ovarian conservation.”

Dr. Nickles Fader reported consulting for Ethicon Endosurgery.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAGS

Cervical bupivacaine blocks pain after laparoscopic hysterectomy

LAS VEGAS – according to a small trial at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga.

Twenty-one women were randomized to 0.5% bupivacaine, 5 mL injected into the cervix at the 3 o’clock position, and 5 mL injected into at the 9 o’clock position to a depth of 3 cm, after anesthesia induction but before insertion of the uterine manipulator. A control group of 20 women received 5 mL of 0.9% saline injected into the same positions. Surgeons were blinded to the randomization.

A stopwatch was started at extubation, and the women were asked to rate their pain on a 10-point visual analogue scale exactly at 30 and 60 minutes.

The bupivacaine group had less pain at both 30 minutes (3.2 versus 5.7 points, P = .01) and 60 minutes (2.3 versus 5.9 points, P less than .001); 71% of women in the bupivacaine group had an average score of 4 or less, indicating adequate pain control, versus just 25% in the control arm (P = .003)

“This is something we should be considering” routinely for laparoscopic hysterectomy, an audience member said after hearing the presentation at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Another audience member was concerned about urinary retention, but there was no increase in the treatment arm, said lead investigator Steven Radtke, MD, a former ob.gyn. surgery fellow at the university, but now at Texas Tech University, El Paso.

There have been many prior attempts to reduce pain after laparoscopic hysterectomy, such as infiltrating port sites with local anesthetic, but the results have been marginal at best, and almost all of them have focused on the abdominal wall as the source of pain.

The investigators thought that pain was more related to perimetrium dissection, colpotomy, and other parts of the operation. There also have been good studies showing that agents injected into the cervix infuse throughout the area. The team decided to try bupivacaine because it’s inexpensive and has a good duration of action, about 8 hours.

There were no significant demographic or intraoperative differences between the groups. On average, women were in their mid-40s, with a body mass index of about 31 kg/m2. The operations took about 2 hours, and were for benign indications, such as fibroids. Oophorectomy was the only concomitant procedure allowed.

The investigators are interested in repeating their investigation with liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel), which has a duration of action past 24 hours. It’s much more expensive, but the strong trial results justify the cost, Dr. Radtke said.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Radtke didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Radtke S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 130.

LAS VEGAS – according to a small trial at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga.

Twenty-one women were randomized to 0.5% bupivacaine, 5 mL injected into the cervix at the 3 o’clock position, and 5 mL injected into at the 9 o’clock position to a depth of 3 cm, after anesthesia induction but before insertion of the uterine manipulator. A control group of 20 women received 5 mL of 0.9% saline injected into the same positions. Surgeons were blinded to the randomization.

A stopwatch was started at extubation, and the women were asked to rate their pain on a 10-point visual analogue scale exactly at 30 and 60 minutes.

The bupivacaine group had less pain at both 30 minutes (3.2 versus 5.7 points, P = .01) and 60 minutes (2.3 versus 5.9 points, P less than .001); 71% of women in the bupivacaine group had an average score of 4 or less, indicating adequate pain control, versus just 25% in the control arm (P = .003)

“This is something we should be considering” routinely for laparoscopic hysterectomy, an audience member said after hearing the presentation at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Another audience member was concerned about urinary retention, but there was no increase in the treatment arm, said lead investigator Steven Radtke, MD, a former ob.gyn. surgery fellow at the university, but now at Texas Tech University, El Paso.

There have been many prior attempts to reduce pain after laparoscopic hysterectomy, such as infiltrating port sites with local anesthetic, but the results have been marginal at best, and almost all of them have focused on the abdominal wall as the source of pain.

The investigators thought that pain was more related to perimetrium dissection, colpotomy, and other parts of the operation. There also have been good studies showing that agents injected into the cervix infuse throughout the area. The team decided to try bupivacaine because it’s inexpensive and has a good duration of action, about 8 hours.

There were no significant demographic or intraoperative differences between the groups. On average, women were in their mid-40s, with a body mass index of about 31 kg/m2. The operations took about 2 hours, and were for benign indications, such as fibroids. Oophorectomy was the only concomitant procedure allowed.

The investigators are interested in repeating their investigation with liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel), which has a duration of action past 24 hours. It’s much more expensive, but the strong trial results justify the cost, Dr. Radtke said.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Radtke didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Radtke S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 130.

LAS VEGAS – according to a small trial at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga.

Twenty-one women were randomized to 0.5% bupivacaine, 5 mL injected into the cervix at the 3 o’clock position, and 5 mL injected into at the 9 o’clock position to a depth of 3 cm, after anesthesia induction but before insertion of the uterine manipulator. A control group of 20 women received 5 mL of 0.9% saline injected into the same positions. Surgeons were blinded to the randomization.

A stopwatch was started at extubation, and the women were asked to rate their pain on a 10-point visual analogue scale exactly at 30 and 60 minutes.

The bupivacaine group had less pain at both 30 minutes (3.2 versus 5.7 points, P = .01) and 60 minutes (2.3 versus 5.9 points, P less than .001); 71% of women in the bupivacaine group had an average score of 4 or less, indicating adequate pain control, versus just 25% in the control arm (P = .003)

“This is something we should be considering” routinely for laparoscopic hysterectomy, an audience member said after hearing the presentation at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Another audience member was concerned about urinary retention, but there was no increase in the treatment arm, said lead investigator Steven Radtke, MD, a former ob.gyn. surgery fellow at the university, but now at Texas Tech University, El Paso.

There have been many prior attempts to reduce pain after laparoscopic hysterectomy, such as infiltrating port sites with local anesthetic, but the results have been marginal at best, and almost all of them have focused on the abdominal wall as the source of pain.

The investigators thought that pain was more related to perimetrium dissection, colpotomy, and other parts of the operation. There also have been good studies showing that agents injected into the cervix infuse throughout the area. The team decided to try bupivacaine because it’s inexpensive and has a good duration of action, about 8 hours.

There were no significant demographic or intraoperative differences between the groups. On average, women were in their mid-40s, with a body mass index of about 31 kg/m2. The operations took about 2 hours, and were for benign indications, such as fibroids. Oophorectomy was the only concomitant procedure allowed.

The investigators are interested in repeating their investigation with liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel), which has a duration of action past 24 hours. It’s much more expensive, but the strong trial results justify the cost, Dr. Radtke said.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Radtke didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Radtke S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 130.

REPORTING FROM AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Postoperative pain can be significantly reduced by injecting the cervix with bupivacaine prior to laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Major finding: The bupivacaine group had less pain at both 30 minutes (3.2 versus 5.7 points, P = .01) and 60 minutes (2.3 versus 5.9 points, P less than .001).

Study details: In a randomized study, 21 women received bupivacaine anesthesia and 20 control women were injected with saline.

Disclosures: There was no external funding, and Dr. Radtke didn’t have any disclosures.

Source: Radtke S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 130.

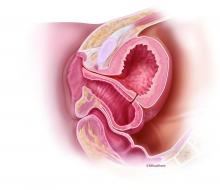

Laparoscopic hysterectomy with obliterated cul-de-sac needs specialist care

LAS VEGAS – When stage IV endometriosis with obliterated posterior cul-de-sac is discovered during laparoscopic hysterectomy, or suspected beforehand, women should be referred to a minimally invasive gynecologic surgery specialist because the procedure will be much more difficult, investigators said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

They reviewed 333 laparoscopic hysterectomies where endometriosis was discovered in the operating room. The disease is known to increase the complexity of hysterectomy; the investigators wanted to quantify the risk by endometriosis severity. Among their subjects, 237 women (71%) had stage I, II, or III endometriosis; 96 (29%) had stage IV disease, including 55 women (57%) with obliterated posterior cul-de-sacs.

Surgery was longer among stage IV cases (137 vs. 116 minutes), and there was greater blood loss; 66% of stage IV women required laparoscopic-modified radical hysterectomy versus about a quarter of women with stage I-III endometriosis.

A total of 93% required modified radical hysterectomies versus 29% of stage IV women with intact cul-de-sacs. Additional procedures were far more likely in this population, including salpingectomy, ureterolysis, enterolysis, cystoscopy, ureteral stenting, proctoscopy, bowel oversew, and anterior resection anastomosis. The differences all were statistically significant.

Among stage IV cases, mean operating time was longer in obliterated cul-de-sac cases (159 vs. 108 minutes), with higher blood loss, 100 mL versus 50 mL.

“Patients with obliterated cul-de-sacs identified intraoperatively should be referred to minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons because of the ... extra training required to safely perform [laparoscopic hysterectomy] with limited morbidity,” said lead investigator Alexandra Melnyk, MD, a University of Pittsburgh ob.gyn resident.

There was no industry funding and the investigators reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Melnyk A et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 81.

LAS VEGAS – When stage IV endometriosis with obliterated posterior cul-de-sac is discovered during laparoscopic hysterectomy, or suspected beforehand, women should be referred to a minimally invasive gynecologic surgery specialist because the procedure will be much more difficult, investigators said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

They reviewed 333 laparoscopic hysterectomies where endometriosis was discovered in the operating room. The disease is known to increase the complexity of hysterectomy; the investigators wanted to quantify the risk by endometriosis severity. Among their subjects, 237 women (71%) had stage I, II, or III endometriosis; 96 (29%) had stage IV disease, including 55 women (57%) with obliterated posterior cul-de-sacs.

Surgery was longer among stage IV cases (137 vs. 116 minutes), and there was greater blood loss; 66% of stage IV women required laparoscopic-modified radical hysterectomy versus about a quarter of women with stage I-III endometriosis.

A total of 93% required modified radical hysterectomies versus 29% of stage IV women with intact cul-de-sacs. Additional procedures were far more likely in this population, including salpingectomy, ureterolysis, enterolysis, cystoscopy, ureteral stenting, proctoscopy, bowel oversew, and anterior resection anastomosis. The differences all were statistically significant.

Among stage IV cases, mean operating time was longer in obliterated cul-de-sac cases (159 vs. 108 minutes), with higher blood loss, 100 mL versus 50 mL.

“Patients with obliterated cul-de-sacs identified intraoperatively should be referred to minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons because of the ... extra training required to safely perform [laparoscopic hysterectomy] with limited morbidity,” said lead investigator Alexandra Melnyk, MD, a University of Pittsburgh ob.gyn resident.

There was no industry funding and the investigators reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Melnyk A et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 81.

LAS VEGAS – When stage IV endometriosis with obliterated posterior cul-de-sac is discovered during laparoscopic hysterectomy, or suspected beforehand, women should be referred to a minimally invasive gynecologic surgery specialist because the procedure will be much more difficult, investigators said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

They reviewed 333 laparoscopic hysterectomies where endometriosis was discovered in the operating room. The disease is known to increase the complexity of hysterectomy; the investigators wanted to quantify the risk by endometriosis severity. Among their subjects, 237 women (71%) had stage I, II, or III endometriosis; 96 (29%) had stage IV disease, including 55 women (57%) with obliterated posterior cul-de-sacs.

Surgery was longer among stage IV cases (137 vs. 116 minutes), and there was greater blood loss; 66% of stage IV women required laparoscopic-modified radical hysterectomy versus about a quarter of women with stage I-III endometriosis.

A total of 93% required modified radical hysterectomies versus 29% of stage IV women with intact cul-de-sacs. Additional procedures were far more likely in this population, including salpingectomy, ureterolysis, enterolysis, cystoscopy, ureteral stenting, proctoscopy, bowel oversew, and anterior resection anastomosis. The differences all were statistically significant.

Among stage IV cases, mean operating time was longer in obliterated cul-de-sac cases (159 vs. 108 minutes), with higher blood loss, 100 mL versus 50 mL.

“Patients with obliterated cul-de-sacs identified intraoperatively should be referred to minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons because of the ... extra training required to safely perform [laparoscopic hysterectomy] with limited morbidity,” said lead investigator Alexandra Melnyk, MD, a University of Pittsburgh ob.gyn resident.

There was no industry funding and the investigators reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Melnyk A et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 81.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Staying up to date on screening may cut risk of death from CRC

according to the results of a large retrospective case-control study.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings signify “potentially modifiable” screening failures in a population known for relatively high uptake of colorectal cancer screening, wrote Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates in Gastroenterology. Strikingly, 76% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were not current on screening versus 55% of cancer-free patients, they said. Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44), even after adjustment for race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and frequency of contact with primary care providers, they added.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal testing are effective and recommended screening techniques that help prevent deaths from colorectal cancer. Therefore, most such deaths are thought to result from “breakdowns in the screening process,” the researchers wrote. However, interval cancers and missed lesions also play a role, and no prior study has examined detailed screening histories and their association with colorectal cancer mortality.

Accordingly, the researchers reviewed medical records and registry data for 1,750 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California systems who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and were part of the health plan for at least 5 years before their cancer diagnosis. They compared these patients with 3,486 cancer-free controls matched by age, sex, study site, and numbers of years enrolled in the health plan. Patients were considered up to date on screening if they were screened at intervals recommended by the 2008 multisociety colorectal cancer screening guidelines – that is, if they had received a colonoscopy within 10 years of colorectal cancer diagnosis or sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years of it. For fecal testing, the investigators used a 2-year interval based on its efficacy in clinical trials.

Among patients who died from colorectal cancer, only 24% were up to date on screening versus 45% of cancer-free-patients, the investigators determined. Furthermore, 68% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were never screened or were not screened at appropriate intervals, compared with 53% of cancer-free patients.

Additionally, while 8% of colorectal cancer deaths occurred in patients who had not followed up on abnormal screening results, only 2% of controls who had received abnormal screening results had failed to follow up.

“In two health systems with high rates of screening, we observed that most patients dying from colorectal cancer had potentially modifiable failures of the screening process,” the researchers concluded. “This study suggests that, even in settings with high screening uptake, access to and timely uptake of screening, regular rescreening, appropriate use of testing given patient characteristics, completion of timely diagnostic testing when screening is positive, and improving the effectiveness of screening tests, particularly for right colon cancer, remain important areas of focus for further decreasing colorectal cancer deaths.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of the journal Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major success story – one of only two cancers (the other being cervical cancer) with an A recommendation for screening from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Multiple randomized trials for two CRC screening modalities, stool-based tests and sigmoidoscopy, have shown significant reductions in CRC incidence and mortality.

Within this context, Doubeni et al. examined the association of CRC screening with death from CRC in a real-world HMO setting. Their study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed a highly protective effect on CRC mortality of being up to date with screening (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44). Second, it examined CRC screening as a process, with various steps of that process related to CRC mortality. Finally, methodologically, the study’s utilization of electronic medical records and cancer registry linkages highlights the importance of integrated data systems in the efficient performance of epidemiologic research.

Of note, screening was primarily stool-based tests (fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test ) and sigmoidoscopy, in contrast to most of the U.S., where colonoscopy is predominant. Randomized trials of these modalities show mortality reductions of 15%-20% (FOBT/FIT) and 25%-30% (sigmoidoscopy), respectively. Therefore, some of the reported effect is likely due to selection bias, with healthier persons more likely to choose screening.

It would be of interest to see similar studies performed in a colonoscopy-predominant screening setting and with the effect on CRC incidence as well as mortality examined.

Paul F. Pinsky, PhD, chief of the Early Detection Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. He has no conflicts of interest.

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major success story – one of only two cancers (the other being cervical cancer) with an A recommendation for screening from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Multiple randomized trials for two CRC screening modalities, stool-based tests and sigmoidoscopy, have shown significant reductions in CRC incidence and mortality.

Within this context, Doubeni et al. examined the association of CRC screening with death from CRC in a real-world HMO setting. Their study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed a highly protective effect on CRC mortality of being up to date with screening (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44). Second, it examined CRC screening as a process, with various steps of that process related to CRC mortality. Finally, methodologically, the study’s utilization of electronic medical records and cancer registry linkages highlights the importance of integrated data systems in the efficient performance of epidemiologic research.

Of note, screening was primarily stool-based tests (fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test ) and sigmoidoscopy, in contrast to most of the U.S., where colonoscopy is predominant. Randomized trials of these modalities show mortality reductions of 15%-20% (FOBT/FIT) and 25%-30% (sigmoidoscopy), respectively. Therefore, some of the reported effect is likely due to selection bias, with healthier persons more likely to choose screening.

It would be of interest to see similar studies performed in a colonoscopy-predominant screening setting and with the effect on CRC incidence as well as mortality examined.

Paul F. Pinsky, PhD, chief of the Early Detection Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. He has no conflicts of interest.

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major success story – one of only two cancers (the other being cervical cancer) with an A recommendation for screening from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Multiple randomized trials for two CRC screening modalities, stool-based tests and sigmoidoscopy, have shown significant reductions in CRC incidence and mortality.

Within this context, Doubeni et al. examined the association of CRC screening with death from CRC in a real-world HMO setting. Their study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed a highly protective effect on CRC mortality of being up to date with screening (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44). Second, it examined CRC screening as a process, with various steps of that process related to CRC mortality. Finally, methodologically, the study’s utilization of electronic medical records and cancer registry linkages highlights the importance of integrated data systems in the efficient performance of epidemiologic research.

Of note, screening was primarily stool-based tests (fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test ) and sigmoidoscopy, in contrast to most of the U.S., where colonoscopy is predominant. Randomized trials of these modalities show mortality reductions of 15%-20% (FOBT/FIT) and 25%-30% (sigmoidoscopy), respectively. Therefore, some of the reported effect is likely due to selection bias, with healthier persons more likely to choose screening.

It would be of interest to see similar studies performed in a colonoscopy-predominant screening setting and with the effect on CRC incidence as well as mortality examined.

Paul F. Pinsky, PhD, chief of the Early Detection Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. He has no conflicts of interest.

according to the results of a large retrospective case-control study.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings signify “potentially modifiable” screening failures in a population known for relatively high uptake of colorectal cancer screening, wrote Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates in Gastroenterology. Strikingly, 76% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were not current on screening versus 55% of cancer-free patients, they said. Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44), even after adjustment for race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and frequency of contact with primary care providers, they added.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal testing are effective and recommended screening techniques that help prevent deaths from colorectal cancer. Therefore, most such deaths are thought to result from “breakdowns in the screening process,” the researchers wrote. However, interval cancers and missed lesions also play a role, and no prior study has examined detailed screening histories and their association with colorectal cancer mortality.

Accordingly, the researchers reviewed medical records and registry data for 1,750 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California systems who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and were part of the health plan for at least 5 years before their cancer diagnosis. They compared these patients with 3,486 cancer-free controls matched by age, sex, study site, and numbers of years enrolled in the health plan. Patients were considered up to date on screening if they were screened at intervals recommended by the 2008 multisociety colorectal cancer screening guidelines – that is, if they had received a colonoscopy within 10 years of colorectal cancer diagnosis or sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years of it. For fecal testing, the investigators used a 2-year interval based on its efficacy in clinical trials.

Among patients who died from colorectal cancer, only 24% were up to date on screening versus 45% of cancer-free-patients, the investigators determined. Furthermore, 68% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were never screened or were not screened at appropriate intervals, compared with 53% of cancer-free patients.

Additionally, while 8% of colorectal cancer deaths occurred in patients who had not followed up on abnormal screening results, only 2% of controls who had received abnormal screening results had failed to follow up.

“In two health systems with high rates of screening, we observed that most patients dying from colorectal cancer had potentially modifiable failures of the screening process,” the researchers concluded. “This study suggests that, even in settings with high screening uptake, access to and timely uptake of screening, regular rescreening, appropriate use of testing given patient characteristics, completion of timely diagnostic testing when screening is positive, and improving the effectiveness of screening tests, particularly for right colon cancer, remain important areas of focus for further decreasing colorectal cancer deaths.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of the journal Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

according to the results of a large retrospective case-control study.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings signify “potentially modifiable” screening failures in a population known for relatively high uptake of colorectal cancer screening, wrote Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates in Gastroenterology. Strikingly, 76% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were not current on screening versus 55% of cancer-free patients, they said. Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44), even after adjustment for race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and frequency of contact with primary care providers, they added.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal testing are effective and recommended screening techniques that help prevent deaths from colorectal cancer. Therefore, most such deaths are thought to result from “breakdowns in the screening process,” the researchers wrote. However, interval cancers and missed lesions also play a role, and no prior study has examined detailed screening histories and their association with colorectal cancer mortality.

Accordingly, the researchers reviewed medical records and registry data for 1,750 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California systems who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and were part of the health plan for at least 5 years before their cancer diagnosis. They compared these patients with 3,486 cancer-free controls matched by age, sex, study site, and numbers of years enrolled in the health plan. Patients were considered up to date on screening if they were screened at intervals recommended by the 2008 multisociety colorectal cancer screening guidelines – that is, if they had received a colonoscopy within 10 years of colorectal cancer diagnosis or sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years of it. For fecal testing, the investigators used a 2-year interval based on its efficacy in clinical trials.

Among patients who died from colorectal cancer, only 24% were up to date on screening versus 45% of cancer-free-patients, the investigators determined. Furthermore, 68% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were never screened or were not screened at appropriate intervals, compared with 53% of cancer-free patients.

Additionally, while 8% of colorectal cancer deaths occurred in patients who had not followed up on abnormal screening results, only 2% of controls who had received abnormal screening results had failed to follow up.

“In two health systems with high rates of screening, we observed that most patients dying from colorectal cancer had potentially modifiable failures of the screening process,” the researchers concluded. “This study suggests that, even in settings with high screening uptake, access to and timely uptake of screening, regular rescreening, appropriate use of testing given patient characteristics, completion of timely diagnostic testing when screening is positive, and improving the effectiveness of screening tests, particularly for right colon cancer, remain important areas of focus for further decreasing colorectal cancer deaths.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of the journal Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Being up to date on screening was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of dying from colon cancer.

Major finding: Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 1,750 patients who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and 3,486 matched controls.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of Gastroenterology.

Source: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

Tegaderm eliminates corneal abrasions in robotic gynecologic surgery

LAS VEGAS – There hasn’t been a single corneal abrasion in 860 cases of gynecologic robotic surgery at the University of Texas, Austin, since surgeons and anesthesiologists there started sealing women’s eyes shut with a thick layer of ointment and Tegaderm, instead of the usual small squeeze of ointment and tape, according to Michael T. Breen, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the university.

“Go back to your hospital, meet with your anesthesiologists, and see what you’re doing to protect your patients’ eyes,” Dr. Breen said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Slathered eyes and Tegaderm are now standard practice at the university. Before the switch was made, there were six corneal abrasions in 231 cases over 6 months. Two of those patients stayed longer in the hospital than they would have otherwise. The changes have eliminated the problem.

The impetus for the switch was a 42-year-old woman who had a robotic hysterectomy. The surgery went fine, but then Dr. Breen had to rush back to the recovery room. The woman was screaming in pain, not from her surgery, but from her left eye.

Corneal abrasions are a well-known risk of surgery because anesthesia decreases tear production and dries the eyes. Robotic gynecologic surgery increases the risk even more, because patients are under longer than with other approaches, and the steep Trendelenburg increases intraocular pressure and eye edema, especially with excess IV fluid.

And “believe it or not, having a pulse oximeter on the dominant hand [also] increases your risk of ocular injury,” Dr. Breen said. Sometimes, patients wake up, go to rub their eyes, and drag the device across their cornea, he said.

The screaming patient – who recovered without permanent damage – prompted Dr. Breen and his colleagues to turn to the literature for solutions. “One was a fully occlusive eye dressing, more than the tape we’ve all been accustomed to, with thick eye ointment application and Tegaderm applying positive pressure to the eye,” he said.

Dr. Breen showed his audience a slide of the setup. “It looks a little unorthodox, but this is how every one of our robotic patients now have their eyes protected. Thick gel which is then covered with a positive pressure Tegaderm,” he said.

, and placing the pulse ox on the nondominant hand. The team already had been decreasing IV fluids as part of their enhanced recovery after surgery protocol, and bringing patients out of steep Trendelenburg as soon as possible.

With the changes, “the rate of corneal abrasions decreased from 2.6% to 0% – and has stayed there,” Dr. Breen said.

There’ve been no allergic reactions to Tegaderm and no eyelid problems. “What we have seen with the simple taping is that, when it comes off, so does some of the eyelid, particularly with geriatric patients. We have not seen that with Tegaderm,” he said.

“Some people use goggles to protect the eyes, and we thought initially that the camera was hitting the face, so we used the Mayo stand to protect it from the camera,” but that didn’t turn out to be the problem, he said. “Goggles actually may make things worse.”

The project had no industry funding, and Dr. Breen had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Breen MT et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 16.

LAS VEGAS – There hasn’t been a single corneal abrasion in 860 cases of gynecologic robotic surgery at the University of Texas, Austin, since surgeons and anesthesiologists there started sealing women’s eyes shut with a thick layer of ointment and Tegaderm, instead of the usual small squeeze of ointment and tape, according to Michael T. Breen, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the university.

“Go back to your hospital, meet with your anesthesiologists, and see what you’re doing to protect your patients’ eyes,” Dr. Breen said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Slathered eyes and Tegaderm are now standard practice at the university. Before the switch was made, there were six corneal abrasions in 231 cases over 6 months. Two of those patients stayed longer in the hospital than they would have otherwise. The changes have eliminated the problem.

The impetus for the switch was a 42-year-old woman who had a robotic hysterectomy. The surgery went fine, but then Dr. Breen had to rush back to the recovery room. The woman was screaming in pain, not from her surgery, but from her left eye.

Corneal abrasions are a well-known risk of surgery because anesthesia decreases tear production and dries the eyes. Robotic gynecologic surgery increases the risk even more, because patients are under longer than with other approaches, and the steep Trendelenburg increases intraocular pressure and eye edema, especially with excess IV fluid.

And “believe it or not, having a pulse oximeter on the dominant hand [also] increases your risk of ocular injury,” Dr. Breen said. Sometimes, patients wake up, go to rub their eyes, and drag the device across their cornea, he said.

The screaming patient – who recovered without permanent damage – prompted Dr. Breen and his colleagues to turn to the literature for solutions. “One was a fully occlusive eye dressing, more than the tape we’ve all been accustomed to, with thick eye ointment application and Tegaderm applying positive pressure to the eye,” he said.

Dr. Breen showed his audience a slide of the setup. “It looks a little unorthodox, but this is how every one of our robotic patients now have their eyes protected. Thick gel which is then covered with a positive pressure Tegaderm,” he said.

, and placing the pulse ox on the nondominant hand. The team already had been decreasing IV fluids as part of their enhanced recovery after surgery protocol, and bringing patients out of steep Trendelenburg as soon as possible.

With the changes, “the rate of corneal abrasions decreased from 2.6% to 0% – and has stayed there,” Dr. Breen said.

There’ve been no allergic reactions to Tegaderm and no eyelid problems. “What we have seen with the simple taping is that, when it comes off, so does some of the eyelid, particularly with geriatric patients. We have not seen that with Tegaderm,” he said.

“Some people use goggles to protect the eyes, and we thought initially that the camera was hitting the face, so we used the Mayo stand to protect it from the camera,” but that didn’t turn out to be the problem, he said. “Goggles actually may make things worse.”

The project had no industry funding, and Dr. Breen had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Breen MT et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 16.

LAS VEGAS – There hasn’t been a single corneal abrasion in 860 cases of gynecologic robotic surgery at the University of Texas, Austin, since surgeons and anesthesiologists there started sealing women’s eyes shut with a thick layer of ointment and Tegaderm, instead of the usual small squeeze of ointment and tape, according to Michael T. Breen, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the university.

“Go back to your hospital, meet with your anesthesiologists, and see what you’re doing to protect your patients’ eyes,” Dr. Breen said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Slathered eyes and Tegaderm are now standard practice at the university. Before the switch was made, there were six corneal abrasions in 231 cases over 6 months. Two of those patients stayed longer in the hospital than they would have otherwise. The changes have eliminated the problem.

The impetus for the switch was a 42-year-old woman who had a robotic hysterectomy. The surgery went fine, but then Dr. Breen had to rush back to the recovery room. The woman was screaming in pain, not from her surgery, but from her left eye.

Corneal abrasions are a well-known risk of surgery because anesthesia decreases tear production and dries the eyes. Robotic gynecologic surgery increases the risk even more, because patients are under longer than with other approaches, and the steep Trendelenburg increases intraocular pressure and eye edema, especially with excess IV fluid.

And “believe it or not, having a pulse oximeter on the dominant hand [also] increases your risk of ocular injury,” Dr. Breen said. Sometimes, patients wake up, go to rub their eyes, and drag the device across their cornea, he said.

The screaming patient – who recovered without permanent damage – prompted Dr. Breen and his colleagues to turn to the literature for solutions. “One was a fully occlusive eye dressing, more than the tape we’ve all been accustomed to, with thick eye ointment application and Tegaderm applying positive pressure to the eye,” he said.

Dr. Breen showed his audience a slide of the setup. “It looks a little unorthodox, but this is how every one of our robotic patients now have their eyes protected. Thick gel which is then covered with a positive pressure Tegaderm,” he said.

, and placing the pulse ox on the nondominant hand. The team already had been decreasing IV fluids as part of their enhanced recovery after surgery protocol, and bringing patients out of steep Trendelenburg as soon as possible.

With the changes, “the rate of corneal abrasions decreased from 2.6% to 0% – and has stayed there,” Dr. Breen said.

There’ve been no allergic reactions to Tegaderm and no eyelid problems. “What we have seen with the simple taping is that, when it comes off, so does some of the eyelid, particularly with geriatric patients. We have not seen that with Tegaderm,” he said.

“Some people use goggles to protect the eyes, and we thought initially that the camera was hitting the face, so we used the Mayo stand to protect it from the camera,” but that didn’t turn out to be the problem, he said. “Goggles actually may make things worse.”

The project had no industry funding, and Dr. Breen had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Breen MT et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 16.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: “The rate of corneal abrasions decreased from 2.6% to 0% – and has stayed there.”

Major finding: Of the 860 cases of gynecologic robotic surgery at the University of Texas, Austin, there has not been a single case of corneal abrasion since the switch.

Study details: Quality improvement project at the university.

Disclosures: The project had no industry funding, and Dr. Breen had no relevant disclosures.

Source: Breen MT et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 16.

Try to normalize albumin before laparoscopic hysterectomy

LAS VEGAS – Serum albumin is an everyday health marker commonly used for risk assessment in open abdominal procedures, but it’s often not checked before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Low levels mean something is off, be it malnutrition, inflammation, chronic disease, or other problems. If it can be normalized before surgery, it should be; women probably will do better, according to investigators from the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

“In minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, we haven’t come to adopt this marker just quite yet. It could be included in the routine battery of tests” at minimal cost. “I think it’s something we should consider,” said ob.gyn. resident Suzanne Lababidi, MD.

The team was curious why serum albumin generally is not a part of routine testing for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The first step was to see if it made a difference, so they reviewed 43,289 cases in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The women were “par for the course;” 51 years old, on average; and had a mean body mass index of 31.9 kg/m2. More than one-third were hypertensive. Mean albumin was in the normal range at 4.1 g/dL, Dr. Lababidi said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Her team did not come up with a cut-point to delay surgery – that’s the goal of further research – but they noticed on linear regression that women with lower preop albumin had higher rates of surgical site infections and intraoperative transfusions, plus higher rates of postop pneumonia; renal failure; urinary tract infection; sepsis; and deep vein thrombosis, among other issues – and even after controlling for hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities. The findings met statistical significance.

It’s true that patients with low albumin might have gone into the operating room sicker, but no matter; Dr. Lababidi’s point was that preop serum albumin is something to pay attention to and correct whenever possible before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Preop levels are something to consider for “counseling and optimizing patients to improve surgical outcomes,” she said.

The next step toward an albumin cut-point is to weed out confounders by further stratifying patients based on albumin levels, she said.

The work received no industry funding. Dr. Lababidi had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lababidi S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 199.

LAS VEGAS – Serum albumin is an everyday health marker commonly used for risk assessment in open abdominal procedures, but it’s often not checked before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Low levels mean something is off, be it malnutrition, inflammation, chronic disease, or other problems. If it can be normalized before surgery, it should be; women probably will do better, according to investigators from the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

“In minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, we haven’t come to adopt this marker just quite yet. It could be included in the routine battery of tests” at minimal cost. “I think it’s something we should consider,” said ob.gyn. resident Suzanne Lababidi, MD.

The team was curious why serum albumin generally is not a part of routine testing for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The first step was to see if it made a difference, so they reviewed 43,289 cases in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The women were “par for the course;” 51 years old, on average; and had a mean body mass index of 31.9 kg/m2. More than one-third were hypertensive. Mean albumin was in the normal range at 4.1 g/dL, Dr. Lababidi said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Her team did not come up with a cut-point to delay surgery – that’s the goal of further research – but they noticed on linear regression that women with lower preop albumin had higher rates of surgical site infections and intraoperative transfusions, plus higher rates of postop pneumonia; renal failure; urinary tract infection; sepsis; and deep vein thrombosis, among other issues – and even after controlling for hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities. The findings met statistical significance.

It’s true that patients with low albumin might have gone into the operating room sicker, but no matter; Dr. Lababidi’s point was that preop serum albumin is something to pay attention to and correct whenever possible before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Preop levels are something to consider for “counseling and optimizing patients to improve surgical outcomes,” she said.

The next step toward an albumin cut-point is to weed out confounders by further stratifying patients based on albumin levels, she said.

The work received no industry funding. Dr. Lababidi had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lababidi S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 199.

LAS VEGAS – Serum albumin is an everyday health marker commonly used for risk assessment in open abdominal procedures, but it’s often not checked before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Low levels mean something is off, be it malnutrition, inflammation, chronic disease, or other problems. If it can be normalized before surgery, it should be; women probably will do better, according to investigators from the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

“In minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, we haven’t come to adopt this marker just quite yet. It could be included in the routine battery of tests” at minimal cost. “I think it’s something we should consider,” said ob.gyn. resident Suzanne Lababidi, MD.

The team was curious why serum albumin generally is not a part of routine testing for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The first step was to see if it made a difference, so they reviewed 43,289 cases in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The women were “par for the course;” 51 years old, on average; and had a mean body mass index of 31.9 kg/m2. More than one-third were hypertensive. Mean albumin was in the normal range at 4.1 g/dL, Dr. Lababidi said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Her team did not come up with a cut-point to delay surgery – that’s the goal of further research – but they noticed on linear regression that women with lower preop albumin had higher rates of surgical site infections and intraoperative transfusions, plus higher rates of postop pneumonia; renal failure; urinary tract infection; sepsis; and deep vein thrombosis, among other issues – and even after controlling for hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities. The findings met statistical significance.

It’s true that patients with low albumin might have gone into the operating room sicker, but no matter; Dr. Lababidi’s point was that preop serum albumin is something to pay attention to and correct whenever possible before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Preop levels are something to consider for “counseling and optimizing patients to improve surgical outcomes,” she said.

The next step toward an albumin cut-point is to weed out confounders by further stratifying patients based on albumin levels, she said.

The work received no industry funding. Dr. Lababidi had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lababidi S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 199.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Antibiotics backed as standard of care for myomectomies

LAS VEGAS – The surgical site infection rate was 2.9% among women who received perioperative antibiotics for fibroid surgery, but 7.8% among those who did not, in a review of 1,433 cases at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

That is despite the fact that antibiotic cases were longer – 155 minutes vs. 89 minutes – and had more blood loss, 200 ml vs. 117 ml. Antibiotic cases also had larger specimen weights – 346 g vs. 176 g – and were more likely to have the uterine cavity entered, 30.2% vs. 14.4%.

“Surgical site infections were more common in the no-antibiotics group despite these being less complex cases.” There was “nearly a fivefold increased odds of surgical site infection or any infectious complication when no antibiotics were given,” after controlling for infection risk factors, including smoking and diabetes, said investigator Nisse V. Clark, MD, a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital.

There are no perioperative antibiotic guidelines for myomectomies; maybe there should be. Almost 94% of the women in the review did receive antibiotics at the Harvard-affiliated hospitals, but the nationwide average has been pegged at about two-thirds, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

The antibiotic cases usually received a cephalosporin before surgery, and were about evenly about evenly split between abdominal, robotic, and laparoscopic approaches.

About one-third of the 90 women (6.3%) who did not get antibiotics had hysteroscopic procedures in which antibiotics usually are not given because the peritoneal cavity is not breeched. Most of the rest, however, were laparoscopic cases. It’s unknown why they weren’t given antibiotics. In her own practice, Dr. Clark said preop antibiotics are the rule for laparoscopic myomectomies.

The surgical site infection difference was driven largely by higher incidences of pelvic abscesses and other organ space infections in the no-antibiotic group.

The only significant demographic difference between the two groups was that women who received antibiotics were slightly younger (mean 38 versus 39.7 years).

In addition to diabetes and smoking, the team adjusted for age, surgery route, body mass index, uterine entry, intraoperative complications, and myoma weight in their multivariate analysis. Still, women in the no-antibiotic group were 4.59 times more likely to have a surgical site infection, 4.76 more likely to have any infectious complication, and almost 8 times more likely to have a major infectious complication. All of the findings were statistically significant.

The study had no industry funding, and Dr. Clark had no disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – The surgical site infection rate was 2.9% among women who received perioperative antibiotics for fibroid surgery, but 7.8% among those who did not, in a review of 1,433 cases at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

That is despite the fact that antibiotic cases were longer – 155 minutes vs. 89 minutes – and had more blood loss, 200 ml vs. 117 ml. Antibiotic cases also had larger specimen weights – 346 g vs. 176 g – and were more likely to have the uterine cavity entered, 30.2% vs. 14.4%.

“Surgical site infections were more common in the no-antibiotics group despite these being less complex cases.” There was “nearly a fivefold increased odds of surgical site infection or any infectious complication when no antibiotics were given,” after controlling for infection risk factors, including smoking and diabetes, said investigator Nisse V. Clark, MD, a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital.

There are no perioperative antibiotic guidelines for myomectomies; maybe there should be. Almost 94% of the women in the review did receive antibiotics at the Harvard-affiliated hospitals, but the nationwide average has been pegged at about two-thirds, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

The antibiotic cases usually received a cephalosporin before surgery, and were about evenly about evenly split between abdominal, robotic, and laparoscopic approaches.

About one-third of the 90 women (6.3%) who did not get antibiotics had hysteroscopic procedures in which antibiotics usually are not given because the peritoneal cavity is not breeched. Most of the rest, however, were laparoscopic cases. It’s unknown why they weren’t given antibiotics. In her own practice, Dr. Clark said preop antibiotics are the rule for laparoscopic myomectomies.

The surgical site infection difference was driven largely by higher incidences of pelvic abscesses and other organ space infections in the no-antibiotic group.

The only significant demographic difference between the two groups was that women who received antibiotics were slightly younger (mean 38 versus 39.7 years).

In addition to diabetes and smoking, the team adjusted for age, surgery route, body mass index, uterine entry, intraoperative complications, and myoma weight in their multivariate analysis. Still, women in the no-antibiotic group were 4.59 times more likely to have a surgical site infection, 4.76 more likely to have any infectious complication, and almost 8 times more likely to have a major infectious complication. All of the findings were statistically significant.

The study had no industry funding, and Dr. Clark had no disclosures.