User login

VIDEO: Meet Frankie and Sophie, the thyroid cancer–sniffing dogs

SAN DIEGO – Researchers at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock are teaching dogs to detect thyroid cancer from urine samples.

The dogs become alert on samples if they detect cancer, but remain passive if they don’t. The first graduate of the program, a German shepherd mix named Frankie, got it right in 30 of 34 cases, matching final surgical pathology results with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 89.5%.

With results like those, it might not be too long before Frankie and his colleagues are providing inexpensive adjunct diagnostic services when test results are uncertain, and helping underserved areas with limited diagnostic capacity, the researchers noted.

At the Endocrine Society meeting, investigator Dr. Andrew Hinson shared clips of Frankie and another recent graduate, a border collie mix named Sophie, and explained the project’s next steps.

Frankie was rescued by principal investigator Dr. Arny Ferrando. Sophie and other dogs in the program were also rescued from local animal shelters.

More information is available at www.thefrankiefoundation.org.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Researchers at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock are teaching dogs to detect thyroid cancer from urine samples.

The dogs become alert on samples if they detect cancer, but remain passive if they don’t. The first graduate of the program, a German shepherd mix named Frankie, got it right in 30 of 34 cases, matching final surgical pathology results with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 89.5%.

With results like those, it might not be too long before Frankie and his colleagues are providing inexpensive adjunct diagnostic services when test results are uncertain, and helping underserved areas with limited diagnostic capacity, the researchers noted.

At the Endocrine Society meeting, investigator Dr. Andrew Hinson shared clips of Frankie and another recent graduate, a border collie mix named Sophie, and explained the project’s next steps.

Frankie was rescued by principal investigator Dr. Arny Ferrando. Sophie and other dogs in the program were also rescued from local animal shelters.

More information is available at www.thefrankiefoundation.org.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Researchers at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock are teaching dogs to detect thyroid cancer from urine samples.

The dogs become alert on samples if they detect cancer, but remain passive if they don’t. The first graduate of the program, a German shepherd mix named Frankie, got it right in 30 of 34 cases, matching final surgical pathology results with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 89.5%.

With results like those, it might not be too long before Frankie and his colleagues are providing inexpensive adjunct diagnostic services when test results are uncertain, and helping underserved areas with limited diagnostic capacity, the researchers noted.

At the Endocrine Society meeting, investigator Dr. Andrew Hinson shared clips of Frankie and another recent graduate, a border collie mix named Sophie, and explained the project’s next steps.

Frankie was rescued by principal investigator Dr. Arny Ferrando. Sophie and other dogs in the program were also rescued from local animal shelters.

More information is available at www.thefrankiefoundation.org.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ENDO 2015

Most thyroid nodules have favorable prognosis

During 5 years of follow-up, cancer arose in only 0.3% of thyroid nodules that were cytologically and sonographically benign at baseline, according to a large prospective study published online March 3 in JAMA.

Furthermore, only two of the five nodules that became cancerous had grown beforehand, reported Dr. Cosimo Durante of the Sapienza University of Rome and his associates. “These data suggest that the American Thyroid Association’s recommendation for indication for repeat cytology should be revised. Clinical and sonographic findings should probably play larger roles in the decision-making process,” the researchers said (JAMA 2015;313:926-35).

Advances in diagnostic imaging have increased the detection of thyroid nodules, the great majority of which are found to be benign. For such nodules, the ATA recommends repeating thyroid ultrasonography at 6-18 months and then every 3-5 years thereafter, as long as nodules do not significantly grow (defined as at least a 20% increase in two nodule diameters, with a minimum increase of at least 2 mm [Thyroid 2009;19:1167-214]). But little is known about rate, extent, or predictors of nodule growth, the researchers noted. Therefore, they performed annual thyroid ultrasound examinations on 992 patients who had one to four asymptomatic subcentimeter thyroid modules that were cytologically or sonographically benign at baseline.

After 5 years of follow-up, just 15.4% of patients had experienced significant nodule growth according to the ATA definition, the researchers reported. Average growth was 4.9 mm, and 9.3% of patients developed new nodules, of which one was found to be cancerous. Growth was least likely when a patient’s largest nodule measured 7.5 mm or less and was significantly more likely when patients had multiple nodules instead of one; had baseline nodule volume greater than 0.2 mL; were up to 45 years old, compared with at least 60 years of age; and were male, the investigators said.

Among older patients, having a body mass index of 28.6 kg/m2 more than doubled the odds of nodule growth, in keeping with recent reports linking obesity and insulin resistance with nodular thyroid disease, they added.

The findings suggest that repeat thyroid ultrasonography could be safely extended to 12 months for initial follow-up and to every 5 years thereafter for most patients, as long as nodule size remained stable, Dr. Durante and his associates said. “This approach should be suitable for about 85% of patients, whose risk of disease progression is low. Closer surveillance may be appropriate for nodules occurring in younger patients or older overweight individuals with multiple nodules, large nodules (greater than 7.5 mm), or both,” they added.

The Umberto Di Mario Foundation, Banca d’Italia, and the Italian Thyroid Cancer Observatory Foundation funded the study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Thyroid nodules are pervasive, whereas thyroid cancer is not. The findings from Durante et al represent an important step in improving the efficiency and mitigating the expense of follow-up for the vast majority of thyroid nodules that are either cytologically or sonographically benign.

These prospective data provide reassurance about the validity of a benign cytology result obtained by ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and confirm a very low false-negative rate, at 1.1%. The practice of routine sonographic surveillance with repeat fine-needle aspiration for growth, as recommended by published guidelines, is not the most efficient strategy to detect the very small number of missed cancers among previously sampled cytologically benign nodules. The one-size-fits-all approach simply does not work. Instead, surveillance strategies should be individualized based on a nodule’s sonographic appearance.

Many nodules detected on ultrasound are small (less than 1 cm) and not sonographically suspicious. In the study by Durante et al, only one cancer was diagnosed during follow-up among the 852 sonographically benign nodules that were smaller than 1 cm. Of note, the trigger for fine-needle aspiration for this nodule was development of hypoechogenicity and irregular margins, not growth.

Although 69% of nodules [in the study] remained stable in size, size increase was not a harbinger of malignancy, especially if the nodule had no sonographically suspicious features.

Anne R. Cappola, M.D., Sc.M., and Susan J. Mandel, M.D., M.P.H., are with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Cappola is also an associate editor of JAMA. These comments are based on their accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015 March 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0836]).

Thyroid nodules are pervasive, whereas thyroid cancer is not. The findings from Durante et al represent an important step in improving the efficiency and mitigating the expense of follow-up for the vast majority of thyroid nodules that are either cytologically or sonographically benign.

These prospective data provide reassurance about the validity of a benign cytology result obtained by ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and confirm a very low false-negative rate, at 1.1%. The practice of routine sonographic surveillance with repeat fine-needle aspiration for growth, as recommended by published guidelines, is not the most efficient strategy to detect the very small number of missed cancers among previously sampled cytologically benign nodules. The one-size-fits-all approach simply does not work. Instead, surveillance strategies should be individualized based on a nodule’s sonographic appearance.

Many nodules detected on ultrasound are small (less than 1 cm) and not sonographically suspicious. In the study by Durante et al, only one cancer was diagnosed during follow-up among the 852 sonographically benign nodules that were smaller than 1 cm. Of note, the trigger for fine-needle aspiration for this nodule was development of hypoechogenicity and irregular margins, not growth.

Although 69% of nodules [in the study] remained stable in size, size increase was not a harbinger of malignancy, especially if the nodule had no sonographically suspicious features.

Anne R. Cappola, M.D., Sc.M., and Susan J. Mandel, M.D., M.P.H., are with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Cappola is also an associate editor of JAMA. These comments are based on their accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015 March 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0836]).

Thyroid nodules are pervasive, whereas thyroid cancer is not. The findings from Durante et al represent an important step in improving the efficiency and mitigating the expense of follow-up for the vast majority of thyroid nodules that are either cytologically or sonographically benign.

These prospective data provide reassurance about the validity of a benign cytology result obtained by ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and confirm a very low false-negative rate, at 1.1%. The practice of routine sonographic surveillance with repeat fine-needle aspiration for growth, as recommended by published guidelines, is not the most efficient strategy to detect the very small number of missed cancers among previously sampled cytologically benign nodules. The one-size-fits-all approach simply does not work. Instead, surveillance strategies should be individualized based on a nodule’s sonographic appearance.

Many nodules detected on ultrasound are small (less than 1 cm) and not sonographically suspicious. In the study by Durante et al, only one cancer was diagnosed during follow-up among the 852 sonographically benign nodules that were smaller than 1 cm. Of note, the trigger for fine-needle aspiration for this nodule was development of hypoechogenicity and irregular margins, not growth.

Although 69% of nodules [in the study] remained stable in size, size increase was not a harbinger of malignancy, especially if the nodule had no sonographically suspicious features.

Anne R. Cappola, M.D., Sc.M., and Susan J. Mandel, M.D., M.P.H., are with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Cappola is also an associate editor of JAMA. These comments are based on their accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015 March 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0836]).

During 5 years of follow-up, cancer arose in only 0.3% of thyroid nodules that were cytologically and sonographically benign at baseline, according to a large prospective study published online March 3 in JAMA.

Furthermore, only two of the five nodules that became cancerous had grown beforehand, reported Dr. Cosimo Durante of the Sapienza University of Rome and his associates. “These data suggest that the American Thyroid Association’s recommendation for indication for repeat cytology should be revised. Clinical and sonographic findings should probably play larger roles in the decision-making process,” the researchers said (JAMA 2015;313:926-35).

Advances in diagnostic imaging have increased the detection of thyroid nodules, the great majority of which are found to be benign. For such nodules, the ATA recommends repeating thyroid ultrasonography at 6-18 months and then every 3-5 years thereafter, as long as nodules do not significantly grow (defined as at least a 20% increase in two nodule diameters, with a minimum increase of at least 2 mm [Thyroid 2009;19:1167-214]). But little is known about rate, extent, or predictors of nodule growth, the researchers noted. Therefore, they performed annual thyroid ultrasound examinations on 992 patients who had one to four asymptomatic subcentimeter thyroid modules that were cytologically or sonographically benign at baseline.

After 5 years of follow-up, just 15.4% of patients had experienced significant nodule growth according to the ATA definition, the researchers reported. Average growth was 4.9 mm, and 9.3% of patients developed new nodules, of which one was found to be cancerous. Growth was least likely when a patient’s largest nodule measured 7.5 mm or less and was significantly more likely when patients had multiple nodules instead of one; had baseline nodule volume greater than 0.2 mL; were up to 45 years old, compared with at least 60 years of age; and were male, the investigators said.

Among older patients, having a body mass index of 28.6 kg/m2 more than doubled the odds of nodule growth, in keeping with recent reports linking obesity and insulin resistance with nodular thyroid disease, they added.

The findings suggest that repeat thyroid ultrasonography could be safely extended to 12 months for initial follow-up and to every 5 years thereafter for most patients, as long as nodule size remained stable, Dr. Durante and his associates said. “This approach should be suitable for about 85% of patients, whose risk of disease progression is low. Closer surveillance may be appropriate for nodules occurring in younger patients or older overweight individuals with multiple nodules, large nodules (greater than 7.5 mm), or both,” they added.

The Umberto Di Mario Foundation, Banca d’Italia, and the Italian Thyroid Cancer Observatory Foundation funded the study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

During 5 years of follow-up, cancer arose in only 0.3% of thyroid nodules that were cytologically and sonographically benign at baseline, according to a large prospective study published online March 3 in JAMA.

Furthermore, only two of the five nodules that became cancerous had grown beforehand, reported Dr. Cosimo Durante of the Sapienza University of Rome and his associates. “These data suggest that the American Thyroid Association’s recommendation for indication for repeat cytology should be revised. Clinical and sonographic findings should probably play larger roles in the decision-making process,” the researchers said (JAMA 2015;313:926-35).

Advances in diagnostic imaging have increased the detection of thyroid nodules, the great majority of which are found to be benign. For such nodules, the ATA recommends repeating thyroid ultrasonography at 6-18 months and then every 3-5 years thereafter, as long as nodules do not significantly grow (defined as at least a 20% increase in two nodule diameters, with a minimum increase of at least 2 mm [Thyroid 2009;19:1167-214]). But little is known about rate, extent, or predictors of nodule growth, the researchers noted. Therefore, they performed annual thyroid ultrasound examinations on 992 patients who had one to four asymptomatic subcentimeter thyroid modules that were cytologically or sonographically benign at baseline.

After 5 years of follow-up, just 15.4% of patients had experienced significant nodule growth according to the ATA definition, the researchers reported. Average growth was 4.9 mm, and 9.3% of patients developed new nodules, of which one was found to be cancerous. Growth was least likely when a patient’s largest nodule measured 7.5 mm or less and was significantly more likely when patients had multiple nodules instead of one; had baseline nodule volume greater than 0.2 mL; were up to 45 years old, compared with at least 60 years of age; and were male, the investigators said.

Among older patients, having a body mass index of 28.6 kg/m2 more than doubled the odds of nodule growth, in keeping with recent reports linking obesity and insulin resistance with nodular thyroid disease, they added.

The findings suggest that repeat thyroid ultrasonography could be safely extended to 12 months for initial follow-up and to every 5 years thereafter for most patients, as long as nodule size remained stable, Dr. Durante and his associates said. “This approach should be suitable for about 85% of patients, whose risk of disease progression is low. Closer surveillance may be appropriate for nodules occurring in younger patients or older overweight individuals with multiple nodules, large nodules (greater than 7.5 mm), or both,” they added.

The Umberto Di Mario Foundation, Banca d’Italia, and the Italian Thyroid Cancer Observatory Foundation funded the study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: The vast majority of thyroid nodules found to be benign at baseline remained so 5 years later.

Major finding: Cancer arose in only 0.3% of nodules in 5 years of follow-up.

Data source: Prospective, multicenter, observational study of 992 patients with 1,567 asymptomatic thyroid nodules.

Disclosures: The Umberto Di Mario Foundation, Banca d’Italia, and the Italian Thyroid Cancer Observatory Foundation funded the study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Teamwork key to head and neck cancer management

PARIS – Successful head and neck cancer management can be achieved only if a multidisciplinary approach is taken, experts emphasized at a recent international conference on anticancer treatment.

Because of its very location and complex anatomy, squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) is a difficult tumor to treat, Dr. Jean-Pierre Lefebvre of Centre Oscar Lambret in Lille, France, explained. Two-thirds of tumors are diagnosed at a late stage and often require a combination of therapeutic approaches and thus “combined toxicities.” Patients also frequently have comorbid illnesses that can affect their compliance and tolerance to treatments.

“There is only one solution: a multidisciplinary approach at any time of the management,” Dr. Lefebvre said.

The multidisciplinary approach requires a tight-knit team of imaging specialists; biologists and pathologists; anesthesiologists and surgeons; medical and radiation oncologists; nurses, general practitioners, and other support professions, such as dentists, dietitians, psychologists, speech and physical therapy specialists; and of course, the patients themselves.

Dr. Lefebvre noted that it was vital to provide patients with good information about their disease and its treatment, from the time of diagnosis to explain the various management decisions made by the multidisciplinary team and likely outcomes of the recommended interventions.

The primary goals of treatment are to control disease above the clavicles and to ensure survival, Dr. Lefebvre observed. Other treatment goals include preserving organ function, controlling symptoms, and creating a minimal impact on a patient’s quality of life by providing treatments that offer minimal long-term toxicity, good tolerability, and perhaps most important, good patient satisfaction.

Selecting treatment can be challenging and cannot be done without a multidisciplinary decision. The two main pathways are a surgery-based or radiotherapy-based treatment, but within each there are multiple options and combinations that need careful consideration on a case-by-case basis.

“It’s not a cookbook decision,” agreed Dr. Jan B. Vermorken, emeritus professor of oncology at Antwerp University Hospital, Belgium, who discussed the systemic treatment of head and neck cancer in a separate lecture. He agreed that head and neck cancer treatment is a multidisciplinary challenge that needs to balance the efficacy and tolerability of treatment on an individual basis, and always while considering the patient’s preferences.

“Patients can be very well informed,” Dr. Vermorken noted and suggested that clinicians need to be prepared to help patients understand the information that they find themselves in order to be able to counter any misinformation they might have found.

“There is no treatment without side effects,” Dr. Vermorken stressed. “When there are no side effects, [the treatment] doesn’t work. So you have to warn patients there are always side effects of the treatment they will be given.”

In addition to the importance of the multidisciplinary team in the management of head and neck cancer, understanding the biology of the disease and using systemic treatment are important for treatment, he said. Recent advances in this area include the recognition of the human papillomavirus as a risk factor for and strong predictor of survival in oropharyngeal cancer, and the role of epidermal growth factor receptor to enable targeting with anti-EGFR drugs, such as cetuximab (Erbitux). Systemic treatment for locally advanced disease includes concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), bioradiotherapy (BRT) with cetuximab and sequential chemotherapy (induction chemotherapy followed by CCRT or BRT).

In most cases of locally advanced SCCHN, the recommended chemotherapy of choice is high-dose cisplatin, given every 3 weeks. Although alternatives to this have been proposed – such as lowering the dose of cisplatin or using carboplatin or cetuximab instead – they have been insufficiently studied and many questions remain unanswered at the moment.

As for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic SCCHN, if it is resectable, then this would be followed by radiotherapy or CCRT. In patients deemed fit enough to handle the regimen, a combination of a platinum agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cetuximab) is a new standard first-line regimen, although the role of maintenance cetuximab is unclear.

Better chemotherapy partners for cetuximab or alternatives for anti-EGFR–targeting agents are under investigation. This includes using docetaxel (Taxotere) instead of 5-FU with cetuximab or using lapatinib (Tykerb), afatinib (Gilotrif) or dacomitinib to block multiple human epidermal growth factor receptors or a variety of monoclonal antibodies to try to overcome resistance to anti-EGFR drugs.

Reactivation of immune surveillance by blocking the PD-1 pathway with drugs such as nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) seems to be a promising approach for treating head and neck cancer and is under investigation in other tumors, including non–small cell lung cancer, triple-negative breast cancer, and melanoma, Dr. Vermorken said.Dr. Lefebvre has acted as a consultant to Merck Serono and Sanofi. Dr. Vermorken has participated in advisory boards of AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Debiopharm; Genentech; Merck Serono; Merck, Sharp & Dohme; Oncolytics Biotech; Pierre Fabre; and Vaccinogen; and received lecturer fees from Merck Serono.

PARIS – Successful head and neck cancer management can be achieved only if a multidisciplinary approach is taken, experts emphasized at a recent international conference on anticancer treatment.

Because of its very location and complex anatomy, squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) is a difficult tumor to treat, Dr. Jean-Pierre Lefebvre of Centre Oscar Lambret in Lille, France, explained. Two-thirds of tumors are diagnosed at a late stage and often require a combination of therapeutic approaches and thus “combined toxicities.” Patients also frequently have comorbid illnesses that can affect their compliance and tolerance to treatments.

“There is only one solution: a multidisciplinary approach at any time of the management,” Dr. Lefebvre said.

The multidisciplinary approach requires a tight-knit team of imaging specialists; biologists and pathologists; anesthesiologists and surgeons; medical and radiation oncologists; nurses, general practitioners, and other support professions, such as dentists, dietitians, psychologists, speech and physical therapy specialists; and of course, the patients themselves.

Dr. Lefebvre noted that it was vital to provide patients with good information about their disease and its treatment, from the time of diagnosis to explain the various management decisions made by the multidisciplinary team and likely outcomes of the recommended interventions.

The primary goals of treatment are to control disease above the clavicles and to ensure survival, Dr. Lefebvre observed. Other treatment goals include preserving organ function, controlling symptoms, and creating a minimal impact on a patient’s quality of life by providing treatments that offer minimal long-term toxicity, good tolerability, and perhaps most important, good patient satisfaction.

Selecting treatment can be challenging and cannot be done without a multidisciplinary decision. The two main pathways are a surgery-based or radiotherapy-based treatment, but within each there are multiple options and combinations that need careful consideration on a case-by-case basis.

“It’s not a cookbook decision,” agreed Dr. Jan B. Vermorken, emeritus professor of oncology at Antwerp University Hospital, Belgium, who discussed the systemic treatment of head and neck cancer in a separate lecture. He agreed that head and neck cancer treatment is a multidisciplinary challenge that needs to balance the efficacy and tolerability of treatment on an individual basis, and always while considering the patient’s preferences.

“Patients can be very well informed,” Dr. Vermorken noted and suggested that clinicians need to be prepared to help patients understand the information that they find themselves in order to be able to counter any misinformation they might have found.

“There is no treatment without side effects,” Dr. Vermorken stressed. “When there are no side effects, [the treatment] doesn’t work. So you have to warn patients there are always side effects of the treatment they will be given.”

In addition to the importance of the multidisciplinary team in the management of head and neck cancer, understanding the biology of the disease and using systemic treatment are important for treatment, he said. Recent advances in this area include the recognition of the human papillomavirus as a risk factor for and strong predictor of survival in oropharyngeal cancer, and the role of epidermal growth factor receptor to enable targeting with anti-EGFR drugs, such as cetuximab (Erbitux). Systemic treatment for locally advanced disease includes concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), bioradiotherapy (BRT) with cetuximab and sequential chemotherapy (induction chemotherapy followed by CCRT or BRT).

In most cases of locally advanced SCCHN, the recommended chemotherapy of choice is high-dose cisplatin, given every 3 weeks. Although alternatives to this have been proposed – such as lowering the dose of cisplatin or using carboplatin or cetuximab instead – they have been insufficiently studied and many questions remain unanswered at the moment.

As for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic SCCHN, if it is resectable, then this would be followed by radiotherapy or CCRT. In patients deemed fit enough to handle the regimen, a combination of a platinum agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cetuximab) is a new standard first-line regimen, although the role of maintenance cetuximab is unclear.

Better chemotherapy partners for cetuximab or alternatives for anti-EGFR–targeting agents are under investigation. This includes using docetaxel (Taxotere) instead of 5-FU with cetuximab or using lapatinib (Tykerb), afatinib (Gilotrif) or dacomitinib to block multiple human epidermal growth factor receptors or a variety of monoclonal antibodies to try to overcome resistance to anti-EGFR drugs.

Reactivation of immune surveillance by blocking the PD-1 pathway with drugs such as nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) seems to be a promising approach for treating head and neck cancer and is under investigation in other tumors, including non–small cell lung cancer, triple-negative breast cancer, and melanoma, Dr. Vermorken said.Dr. Lefebvre has acted as a consultant to Merck Serono and Sanofi. Dr. Vermorken has participated in advisory boards of AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Debiopharm; Genentech; Merck Serono; Merck, Sharp & Dohme; Oncolytics Biotech; Pierre Fabre; and Vaccinogen; and received lecturer fees from Merck Serono.

PARIS – Successful head and neck cancer management can be achieved only if a multidisciplinary approach is taken, experts emphasized at a recent international conference on anticancer treatment.

Because of its very location and complex anatomy, squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) is a difficult tumor to treat, Dr. Jean-Pierre Lefebvre of Centre Oscar Lambret in Lille, France, explained. Two-thirds of tumors are diagnosed at a late stage and often require a combination of therapeutic approaches and thus “combined toxicities.” Patients also frequently have comorbid illnesses that can affect their compliance and tolerance to treatments.

“There is only one solution: a multidisciplinary approach at any time of the management,” Dr. Lefebvre said.

The multidisciplinary approach requires a tight-knit team of imaging specialists; biologists and pathologists; anesthesiologists and surgeons; medical and radiation oncologists; nurses, general practitioners, and other support professions, such as dentists, dietitians, psychologists, speech and physical therapy specialists; and of course, the patients themselves.

Dr. Lefebvre noted that it was vital to provide patients with good information about their disease and its treatment, from the time of diagnosis to explain the various management decisions made by the multidisciplinary team and likely outcomes of the recommended interventions.

The primary goals of treatment are to control disease above the clavicles and to ensure survival, Dr. Lefebvre observed. Other treatment goals include preserving organ function, controlling symptoms, and creating a minimal impact on a patient’s quality of life by providing treatments that offer minimal long-term toxicity, good tolerability, and perhaps most important, good patient satisfaction.

Selecting treatment can be challenging and cannot be done without a multidisciplinary decision. The two main pathways are a surgery-based or radiotherapy-based treatment, but within each there are multiple options and combinations that need careful consideration on a case-by-case basis.

“It’s not a cookbook decision,” agreed Dr. Jan B. Vermorken, emeritus professor of oncology at Antwerp University Hospital, Belgium, who discussed the systemic treatment of head and neck cancer in a separate lecture. He agreed that head and neck cancer treatment is a multidisciplinary challenge that needs to balance the efficacy and tolerability of treatment on an individual basis, and always while considering the patient’s preferences.

“Patients can be very well informed,” Dr. Vermorken noted and suggested that clinicians need to be prepared to help patients understand the information that they find themselves in order to be able to counter any misinformation they might have found.

“There is no treatment without side effects,” Dr. Vermorken stressed. “When there are no side effects, [the treatment] doesn’t work. So you have to warn patients there are always side effects of the treatment they will be given.”

In addition to the importance of the multidisciplinary team in the management of head and neck cancer, understanding the biology of the disease and using systemic treatment are important for treatment, he said. Recent advances in this area include the recognition of the human papillomavirus as a risk factor for and strong predictor of survival in oropharyngeal cancer, and the role of epidermal growth factor receptor to enable targeting with anti-EGFR drugs, such as cetuximab (Erbitux). Systemic treatment for locally advanced disease includes concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), bioradiotherapy (BRT) with cetuximab and sequential chemotherapy (induction chemotherapy followed by CCRT or BRT).

In most cases of locally advanced SCCHN, the recommended chemotherapy of choice is high-dose cisplatin, given every 3 weeks. Although alternatives to this have been proposed – such as lowering the dose of cisplatin or using carboplatin or cetuximab instead – they have been insufficiently studied and many questions remain unanswered at the moment.

As for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic SCCHN, if it is resectable, then this would be followed by radiotherapy or CCRT. In patients deemed fit enough to handle the regimen, a combination of a platinum agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cetuximab) is a new standard first-line regimen, although the role of maintenance cetuximab is unclear.

Better chemotherapy partners for cetuximab or alternatives for anti-EGFR–targeting agents are under investigation. This includes using docetaxel (Taxotere) instead of 5-FU with cetuximab or using lapatinib (Tykerb), afatinib (Gilotrif) or dacomitinib to block multiple human epidermal growth factor receptors or a variety of monoclonal antibodies to try to overcome resistance to anti-EGFR drugs.

Reactivation of immune surveillance by blocking the PD-1 pathway with drugs such as nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) seems to be a promising approach for treating head and neck cancer and is under investigation in other tumors, including non–small cell lung cancer, triple-negative breast cancer, and melanoma, Dr. Vermorken said.Dr. Lefebvre has acted as a consultant to Merck Serono and Sanofi. Dr. Vermorken has participated in advisory boards of AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Debiopharm; Genentech; Merck Serono; Merck, Sharp & Dohme; Oncolytics Biotech; Pierre Fabre; and Vaccinogen; and received lecturer fees from Merck Serono.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ICACT 2015

Rising to the therapeutic challenge of head and neck cancer

As a significant cause of cancer-related mortality, head and neck cancer presents an important therapeutic challenge that has proven relatively resistant to attempts to improve patient outcomes over the past several decades. In recent years, molecular profiling of head and neck cancers has provided greater insight into their significant genetic heterogeneity, creating potential opportunities for novel therapies. Here, we discuss the most promising advances.

Limited progress in HNSCC treatment

Cancers of the nasal cavity, sinuses, mouth, lips, salivary glands, throat, and larynx, collectively called head and neck cancers, are the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The majority of head and neck cancer arises in the epithelial cells that line the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck and is known as squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). If caught in the early stages, HNSCC has a high cure rate with single-modality treatment with either surgery or radiation therapy (RT).1 However, a substantial proportion of patients present with advanced disease that requires multimodality therapy and has significantly poorer outcomes. Locally advanced HNSCC is typically treated with various combinations of surgery, RT, and chemotherapy and survival rates for all patients at 5 years are 40%- 60%, compared with 70%-90% for patients with early-stage disease.1,3 Up to half of locally advanced tumors relapse within the first 2 years after treatment. For patients with recurrent/metastatic disease, various chemotherapeutic regimens are available but median survival is typically less than a year.3-5

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

As a significant cause of cancer-related mortality, head and neck cancer presents an important therapeutic challenge that has proven relatively resistant to attempts to improve patient outcomes over the past several decades. In recent years, molecular profiling of head and neck cancers has provided greater insight into their significant genetic heterogeneity, creating potential opportunities for novel therapies. Here, we discuss the most promising advances.

Limited progress in HNSCC treatment

Cancers of the nasal cavity, sinuses, mouth, lips, salivary glands, throat, and larynx, collectively called head and neck cancers, are the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The majority of head and neck cancer arises in the epithelial cells that line the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck and is known as squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). If caught in the early stages, HNSCC has a high cure rate with single-modality treatment with either surgery or radiation therapy (RT).1 However, a substantial proportion of patients present with advanced disease that requires multimodality therapy and has significantly poorer outcomes. Locally advanced HNSCC is typically treated with various combinations of surgery, RT, and chemotherapy and survival rates for all patients at 5 years are 40%- 60%, compared with 70%-90% for patients with early-stage disease.1,3 Up to half of locally advanced tumors relapse within the first 2 years after treatment. For patients with recurrent/metastatic disease, various chemotherapeutic regimens are available but median survival is typically less than a year.3-5

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

As a significant cause of cancer-related mortality, head and neck cancer presents an important therapeutic challenge that has proven relatively resistant to attempts to improve patient outcomes over the past several decades. In recent years, molecular profiling of head and neck cancers has provided greater insight into their significant genetic heterogeneity, creating potential opportunities for novel therapies. Here, we discuss the most promising advances.

Limited progress in HNSCC treatment

Cancers of the nasal cavity, sinuses, mouth, lips, salivary glands, throat, and larynx, collectively called head and neck cancers, are the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The majority of head and neck cancer arises in the epithelial cells that line the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck and is known as squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). If caught in the early stages, HNSCC has a high cure rate with single-modality treatment with either surgery or radiation therapy (RT).1 However, a substantial proportion of patients present with advanced disease that requires multimodality therapy and has significantly poorer outcomes. Locally advanced HNSCC is typically treated with various combinations of surgery, RT, and chemotherapy and survival rates for all patients at 5 years are 40%- 60%, compared with 70%-90% for patients with early-stage disease.1,3 Up to half of locally advanced tumors relapse within the first 2 years after treatment. For patients with recurrent/metastatic disease, various chemotherapeutic regimens are available but median survival is typically less than a year.3-5

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Lenvatinib extends PFS significantly in iodine-refractory relapsed thyroid cancer

Lenvatinib was associated with significant improvements in progression-free survival among patients with radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer when compared with placebo, according to research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the randomized, multicenter study, 261 patients received lenvatinib (at a daily dose of 24 mg per day in 28-day cycles) and 131 patients received a placebo. The median progression-free survival was 18.3 months in the lenvatinib group and 3.6 months in the placebo group, the investigators wrote, although adverse effects occurred in more than 40% of patients in the lenvatinib group.

Lenvatinib is an oral inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 through 4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, RET, and KIT.

Read more at N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 (doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1406470).

Lenvatinib was associated with significant improvements in progression-free survival among patients with radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer when compared with placebo, according to research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the randomized, multicenter study, 261 patients received lenvatinib (at a daily dose of 24 mg per day in 28-day cycles) and 131 patients received a placebo. The median progression-free survival was 18.3 months in the lenvatinib group and 3.6 months in the placebo group, the investigators wrote, although adverse effects occurred in more than 40% of patients in the lenvatinib group.

Lenvatinib is an oral inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 through 4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, RET, and KIT.

Read more at N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 (doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1406470).

Lenvatinib was associated with significant improvements in progression-free survival among patients with radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer when compared with placebo, according to research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the randomized, multicenter study, 261 patients received lenvatinib (at a daily dose of 24 mg per day in 28-day cycles) and 131 patients received a placebo. The median progression-free survival was 18.3 months in the lenvatinib group and 3.6 months in the placebo group, the investigators wrote, although adverse effects occurred in more than 40% of patients in the lenvatinib group.

Lenvatinib is an oral inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 through 4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, RET, and KIT.

Read more at N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 (doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1406470).

Lenvima gets the FDA’s nod for differentiated thyroid cancer

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the kinase inhibitor lenvatinib (Lenvima) for the treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer, the agency announced Feb. 13. The drug is approved for use in patients in whom disease progressed despite receiving radioactive iodine therapy.

A trial of 392 patients with progressive, radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) found a median progression-free survival time of 18.3 months in participants treated with Lenvima, compared with a median of 3.6 months in those who received a placebo, the FDA said in a statement. In addition, 65% of lenvatinib-treated patients saw a reduction in tumor size, compared with just 2% of patients who received placebo.

DTC is the most common type of thyroid cancer. The National Cancer Institute has estimated that nearly 63,000 Americans were diagnosed with thyroid cancer, and nearly 1,900 died from the disease in 2014, the FDA said.

Lenvatinib was approved early upon expedited review under the FDA’s priority review program, which allows for the accelerated evaluation of promising drugs that would significantly benefit patients with serious illness.

Common side effects from the drug included hypertension, fatigue, diarrhea, joint and muscle pain, decreased appetite, weight loss, and nausea, among others.

Lenvatinib is marketed by Eisai, based in Woodcliff Lake, N.J.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the kinase inhibitor lenvatinib (Lenvima) for the treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer, the agency announced Feb. 13. The drug is approved for use in patients in whom disease progressed despite receiving radioactive iodine therapy.

A trial of 392 patients with progressive, radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) found a median progression-free survival time of 18.3 months in participants treated with Lenvima, compared with a median of 3.6 months in those who received a placebo, the FDA said in a statement. In addition, 65% of lenvatinib-treated patients saw a reduction in tumor size, compared with just 2% of patients who received placebo.

DTC is the most common type of thyroid cancer. The National Cancer Institute has estimated that nearly 63,000 Americans were diagnosed with thyroid cancer, and nearly 1,900 died from the disease in 2014, the FDA said.

Lenvatinib was approved early upon expedited review under the FDA’s priority review program, which allows for the accelerated evaluation of promising drugs that would significantly benefit patients with serious illness.

Common side effects from the drug included hypertension, fatigue, diarrhea, joint and muscle pain, decreased appetite, weight loss, and nausea, among others.

Lenvatinib is marketed by Eisai, based in Woodcliff Lake, N.J.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the kinase inhibitor lenvatinib (Lenvima) for the treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer, the agency announced Feb. 13. The drug is approved for use in patients in whom disease progressed despite receiving radioactive iodine therapy.

A trial of 392 patients with progressive, radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) found a median progression-free survival time of 18.3 months in participants treated with Lenvima, compared with a median of 3.6 months in those who received a placebo, the FDA said in a statement. In addition, 65% of lenvatinib-treated patients saw a reduction in tumor size, compared with just 2% of patients who received placebo.

DTC is the most common type of thyroid cancer. The National Cancer Institute has estimated that nearly 63,000 Americans were diagnosed with thyroid cancer, and nearly 1,900 died from the disease in 2014, the FDA said.

Lenvatinib was approved early upon expedited review under the FDA’s priority review program, which allows for the accelerated evaluation of promising drugs that would significantly benefit patients with serious illness.

Common side effects from the drug included hypertension, fatigue, diarrhea, joint and muscle pain, decreased appetite, weight loss, and nausea, among others.

Lenvatinib is marketed by Eisai, based in Woodcliff Lake, N.J.

David Henry's JCSO podcast, January 2015

In his monthly podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, Dr David Henry looks at Original Reports on the comparison of atropine-diphenoxylate and hyoscyamine in lowering the rates of irinotecan-related cholinergic syndrome; the effects of age and comorbidities in the management of rectal cancer in elderly patients at an institution in Portugal; the impact of a telehealth intervention on quality of life and symptom distress in patients with head and neck cancer; and the beneficial effects of animal-assisted visits on quality of life during multimodal radiation-chemotherapy regimens. He also discusses a Research Report in which the authors attempt, possibly for the first time, to quantify radiation exposure from diagnostic procedures in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, as well as two feature articles – a round-up of some of the presentations at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and a Journal Club presentation of therapies for lymphoproliferative disorders.

In his monthly podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, Dr David Henry looks at Original Reports on the comparison of atropine-diphenoxylate and hyoscyamine in lowering the rates of irinotecan-related cholinergic syndrome; the effects of age and comorbidities in the management of rectal cancer in elderly patients at an institution in Portugal; the impact of a telehealth intervention on quality of life and symptom distress in patients with head and neck cancer; and the beneficial effects of animal-assisted visits on quality of life during multimodal radiation-chemotherapy regimens. He also discusses a Research Report in which the authors attempt, possibly for the first time, to quantify radiation exposure from diagnostic procedures in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, as well as two feature articles – a round-up of some of the presentations at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and a Journal Club presentation of therapies for lymphoproliferative disorders.

In his monthly podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, Dr David Henry looks at Original Reports on the comparison of atropine-diphenoxylate and hyoscyamine in lowering the rates of irinotecan-related cholinergic syndrome; the effects of age and comorbidities in the management of rectal cancer in elderly patients at an institution in Portugal; the impact of a telehealth intervention on quality of life and symptom distress in patients with head and neck cancer; and the beneficial effects of animal-assisted visits on quality of life during multimodal radiation-chemotherapy regimens. He also discusses a Research Report in which the authors attempt, possibly for the first time, to quantify radiation exposure from diagnostic procedures in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, as well as two feature articles – a round-up of some of the presentations at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and a Journal Club presentation of therapies for lymphoproliferative disorders.

Impact of a telehealth intervention on quality of life and symptom distress in patients with head and neck cancer

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Beneficial effects of animal-assisted visits on quality of life during multimodal radiation-chemotherapy regimens

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Complete Heart Block in a Patient With Metastatic Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

A 74-year-old woman presented with a 2-day history of exertional dyspnea and palpitations. Her past medical history was significant for metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine ablation with levothyroxine for chronic suppressive therapy.

On examination, the patient was afebrile with an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air, heart rate of 92 beats/min, and blood pressure of 100/54 mm Hg. There was trace bilateral lower extremity edema, and her cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. The laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 24,300/µL (3,400-9,800); platelets 86,000/µL (142,000-362,000); thyroid stimulating hormone 0.009 mlU/L (0.4-4.1); free T4 2.07 ng/dL (0.8-2.0); thyroglobulin antibody titer < 1:10 (< 1:160); thyroid microsomal antibody titer < 1:100 (< 1:1600); and thyroglobulin 17.9 ng/mL (2.0-35.0). Her initial troponin T was undetectable.

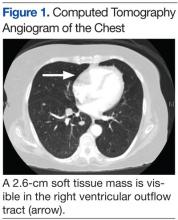

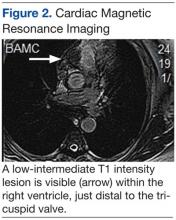

An electrocardiogram showed a first-degree atrioventricular block and subsequently a new intermittent third-degree atrioventricular block. A computed tomography angiogram (Figure 1) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed a 2.6-cm soft tissue mass in the right ventricular outflow tract along with multiple pulmonary emboli and previously diagnosed pulmonary metastases. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan (not shown) revealed a 3.5-cm PET-avid lesion within the right ventricular outflow tract.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Treatment

Diagnosis and Discussion

This patient experienced complete heart block due to a cardiac tumor from papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis. Complete heart block is not an unprecedented symptom of metastatic disease, but to our knowledge this is the first reported case of heart block secondary to metastatic papillary thyroid cancer.1 In general, metastatic cardiac tumors, usually associated with cancers of the breast and lung, melanoma, and lymphoma, are more common than are primary cardiac tumors and are often asymptomatic and discovered mostly postmortem.2,3 The frequency of thyroid metastasis to the heart has been reported to be as low as 0% to 2%, and a review of the literature demonstrated only 13 total cases in the past 30 years.

Theoretical mechanisms for invasion into the heart include lymphatic spread, hematogenous dissemination, or direct right ventricular invasion from the thoracic duct. It has been suggested that the lower blood flow to the myocardium (240 mL/min) relative to bone (600 mL/min) or the brain (750 mL/min) is the reason for a lower likelihood of cardiac involvement in metastatic disease.3 Given the findings in this case, evidence of cardiac conduction abnormalities in the setting of papillary thyroid cancer should raise suspicion for cardiac metastatic disease.

Case Outcome

In this patient, a permanent pacemaker was implanted for high-grade atrioventricular block, with resolution of the palpitations. The pulmonary emboli were concomitantly treated with enoxaparin, and the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Her prognosis was extremely poor given that survival with cardiac metastasis from any type of cancer is limited to a few weeks to months.3 She was to be reevaluated for experimental chemotherapy after reconditioning. However, not long after discharge she was readmitted in respiratory failure and died.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kevin Steel, Lt Col, USAF, MC, imaging cardiologist at the Brooke Army Medical Center for his time and effort in accessing and preparing the CT and MRI images for this article.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or any other of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Conley M, Hawkins K, Ririe D. Complete heart block and cardiac tamponade secondary to Merkel cell carcinoma cardiac metastases. South Med J. 2006;99(1):74-78.

2. Pascale P, Prior JO, Carron PN, Pruvot E, Muller O. Haemoptysis and complete atrioventricular block. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(11):1396.

3. Giuffrida D, Gharib H. Cardiac metastasis from primary anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Report of three cases and a review of the literature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8(1):71-73.

A 74-year-old woman presented with a 2-day history of exertional dyspnea and palpitations. Her past medical history was significant for metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine ablation with levothyroxine for chronic suppressive therapy.

On examination, the patient was afebrile with an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air, heart rate of 92 beats/min, and blood pressure of 100/54 mm Hg. There was trace bilateral lower extremity edema, and her cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. The laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 24,300/µL (3,400-9,800); platelets 86,000/µL (142,000-362,000); thyroid stimulating hormone 0.009 mlU/L (0.4-4.1); free T4 2.07 ng/dL (0.8-2.0); thyroglobulin antibody titer < 1:10 (< 1:160); thyroid microsomal antibody titer < 1:100 (< 1:1600); and thyroglobulin 17.9 ng/mL (2.0-35.0). Her initial troponin T was undetectable.

An electrocardiogram showed a first-degree atrioventricular block and subsequently a new intermittent third-degree atrioventricular block. A computed tomography angiogram (Figure 1) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed a 2.6-cm soft tissue mass in the right ventricular outflow tract along with multiple pulmonary emboli and previously diagnosed pulmonary metastases. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan (not shown) revealed a 3.5-cm PET-avid lesion within the right ventricular outflow tract.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Treatment

Diagnosis and Discussion

This patient experienced complete heart block due to a cardiac tumor from papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis. Complete heart block is not an unprecedented symptom of metastatic disease, but to our knowledge this is the first reported case of heart block secondary to metastatic papillary thyroid cancer.1 In general, metastatic cardiac tumors, usually associated with cancers of the breast and lung, melanoma, and lymphoma, are more common than are primary cardiac tumors and are often asymptomatic and discovered mostly postmortem.2,3 The frequency of thyroid metastasis to the heart has been reported to be as low as 0% to 2%, and a review of the literature demonstrated only 13 total cases in the past 30 years.

Theoretical mechanisms for invasion into the heart include lymphatic spread, hematogenous dissemination, or direct right ventricular invasion from the thoracic duct. It has been suggested that the lower blood flow to the myocardium (240 mL/min) relative to bone (600 mL/min) or the brain (750 mL/min) is the reason for a lower likelihood of cardiac involvement in metastatic disease.3 Given the findings in this case, evidence of cardiac conduction abnormalities in the setting of papillary thyroid cancer should raise suspicion for cardiac metastatic disease.

Case Outcome

In this patient, a permanent pacemaker was implanted for high-grade atrioventricular block, with resolution of the palpitations. The pulmonary emboli were concomitantly treated with enoxaparin, and the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Her prognosis was extremely poor given that survival with cardiac metastasis from any type of cancer is limited to a few weeks to months.3 She was to be reevaluated for experimental chemotherapy after reconditioning. However, not long after discharge she was readmitted in respiratory failure and died.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kevin Steel, Lt Col, USAF, MC, imaging cardiologist at the Brooke Army Medical Center for his time and effort in accessing and preparing the CT and MRI images for this article.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or any other of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

A 74-year-old woman presented with a 2-day history of exertional dyspnea and palpitations. Her past medical history was significant for metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine ablation with levothyroxine for chronic suppressive therapy.

On examination, the patient was afebrile with an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air, heart rate of 92 beats/min, and blood pressure of 100/54 mm Hg. There was trace bilateral lower extremity edema, and her cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. The laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 24,300/µL (3,400-9,800); platelets 86,000/µL (142,000-362,000); thyroid stimulating hormone 0.009 mlU/L (0.4-4.1); free T4 2.07 ng/dL (0.8-2.0); thyroglobulin antibody titer < 1:10 (< 1:160); thyroid microsomal antibody titer < 1:100 (< 1:1600); and thyroglobulin 17.9 ng/mL (2.0-35.0). Her initial troponin T was undetectable.

An electrocardiogram showed a first-degree atrioventricular block and subsequently a new intermittent third-degree atrioventricular block. A computed tomography angiogram (Figure 1) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed a 2.6-cm soft tissue mass in the right ventricular outflow tract along with multiple pulmonary emboli and previously diagnosed pulmonary metastases. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan (not shown) revealed a 3.5-cm PET-avid lesion within the right ventricular outflow tract.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Treatment

Diagnosis and Discussion

This patient experienced complete heart block due to a cardiac tumor from papillary thyroid carcinoma metastasis. Complete heart block is not an unprecedented symptom of metastatic disease, but to our knowledge this is the first reported case of heart block secondary to metastatic papillary thyroid cancer.1 In general, metastatic cardiac tumors, usually associated with cancers of the breast and lung, melanoma, and lymphoma, are more common than are primary cardiac tumors and are often asymptomatic and discovered mostly postmortem.2,3 The frequency of thyroid metastasis to the heart has been reported to be as low as 0% to 2%, and a review of the literature demonstrated only 13 total cases in the past 30 years.

Theoretical mechanisms for invasion into the heart include lymphatic spread, hematogenous dissemination, or direct right ventricular invasion from the thoracic duct. It has been suggested that the lower blood flow to the myocardium (240 mL/min) relative to bone (600 mL/min) or the brain (750 mL/min) is the reason for a lower likelihood of cardiac involvement in metastatic disease.3 Given the findings in this case, evidence of cardiac conduction abnormalities in the setting of papillary thyroid cancer should raise suspicion for cardiac metastatic disease.

Case Outcome

In this patient, a permanent pacemaker was implanted for high-grade atrioventricular block, with resolution of the palpitations. The pulmonary emboli were concomitantly treated with enoxaparin, and the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Her prognosis was extremely poor given that survival with cardiac metastasis from any type of cancer is limited to a few weeks to months.3 She was to be reevaluated for experimental chemotherapy after reconditioning. However, not long after discharge she was readmitted in respiratory failure and died.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kevin Steel, Lt Col, USAF, MC, imaging cardiologist at the Brooke Army Medical Center for his time and effort in accessing and preparing the CT and MRI images for this article.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or any other of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Conley M, Hawkins K, Ririe D. Complete heart block and cardiac tamponade secondary to Merkel cell carcinoma cardiac metastases. South Med J. 2006;99(1):74-78.

2. Pascale P, Prior JO, Carron PN, Pruvot E, Muller O. Haemoptysis and complete atrioventricular block. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(11):1396.

3. Giuffrida D, Gharib H. Cardiac metastasis from primary anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Report of three cases and a review of the literature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8(1):71-73.

1. Conley M, Hawkins K, Ririe D. Complete heart block and cardiac tamponade secondary to Merkel cell carcinoma cardiac metastases. South Med J. 2006;99(1):74-78.

2. Pascale P, Prior JO, Carron PN, Pruvot E, Muller O. Haemoptysis and complete atrioventricular block. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(11):1396.

3. Giuffrida D, Gharib H. Cardiac metastasis from primary anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Report of three cases and a review of the literature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8(1):71-73.