User login

New tool predicts antimicrobial resistance in sepsis

Use of a clinical decision tree predicted antibiotic resistance in sepsis patients infected with gram-negative bacteria, based on data from 1,618 patients.

Increasing rates of bacterial resistance have “contributed to the unwarranted empiric administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, further promoting resistance emergence across microbial species,” said M. Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and her colleagues (Clin Infect Dis. cix612. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix612).

The researchers identified adults with sepsis or septic shock caused by bloodstream infections who were treated at a single center between 2008 and 2015. They developed clinical decision trees using the CHAID algorithm (Chi squared Automatic Interaction Detection) to analyze risk factors for resistance associated with three antibiotics: piperacillin-tazobactam (PT), cefepime (CE), and meropenem (ME).

Overall, resistance rates to PT, CE, and ME were 29%, 22%, and 9%, respectively, and 6.6% of the isolates were resistant to all three antibiotics.

Factors associated with increased resistance risk included residence in a nursing home, transfer from an outside hospital, and prior antibiotics use. Resistance to ME was associated with infection with Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter spp, the researchers noted, and resistance to PT was associated with central nervous system and central venous catheter infections.

Clinical decision trees were able to separate patients at low risk for resistance to PT and CE, as well as those with a risk greater than 30% of resistance to PT, CE, or ME. “We also found good overall agreement between the accuracies of the [multivariable logistic regression] models and the decision tree analyses for predicting antibiotic resistance,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of data from a single center and incomplete reporting of previous antibiotic exposure, the researchers noted. However, the results “provide a framework for how empiric antibiotics can be tailored according to decision tree patient clusters,” they said.

Combining user-friendly clinical decision trees and multivariable logistic regression models may offer the best opportunities for hospitals to derive local models to help with antimicrobial prescription.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Use of a clinical decision tree predicted antibiotic resistance in sepsis patients infected with gram-negative bacteria, based on data from 1,618 patients.

Increasing rates of bacterial resistance have “contributed to the unwarranted empiric administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, further promoting resistance emergence across microbial species,” said M. Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and her colleagues (Clin Infect Dis. cix612. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix612).

The researchers identified adults with sepsis or septic shock caused by bloodstream infections who were treated at a single center between 2008 and 2015. They developed clinical decision trees using the CHAID algorithm (Chi squared Automatic Interaction Detection) to analyze risk factors for resistance associated with three antibiotics: piperacillin-tazobactam (PT), cefepime (CE), and meropenem (ME).

Overall, resistance rates to PT, CE, and ME were 29%, 22%, and 9%, respectively, and 6.6% of the isolates were resistant to all three antibiotics.

Factors associated with increased resistance risk included residence in a nursing home, transfer from an outside hospital, and prior antibiotics use. Resistance to ME was associated with infection with Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter spp, the researchers noted, and resistance to PT was associated with central nervous system and central venous catheter infections.

Clinical decision trees were able to separate patients at low risk for resistance to PT and CE, as well as those with a risk greater than 30% of resistance to PT, CE, or ME. “We also found good overall agreement between the accuracies of the [multivariable logistic regression] models and the decision tree analyses for predicting antibiotic resistance,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of data from a single center and incomplete reporting of previous antibiotic exposure, the researchers noted. However, the results “provide a framework for how empiric antibiotics can be tailored according to decision tree patient clusters,” they said.

Combining user-friendly clinical decision trees and multivariable logistic regression models may offer the best opportunities for hospitals to derive local models to help with antimicrobial prescription.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Use of a clinical decision tree predicted antibiotic resistance in sepsis patients infected with gram-negative bacteria, based on data from 1,618 patients.

Increasing rates of bacterial resistance have “contributed to the unwarranted empiric administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, further promoting resistance emergence across microbial species,” said M. Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and her colleagues (Clin Infect Dis. cix612. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix612).

The researchers identified adults with sepsis or septic shock caused by bloodstream infections who were treated at a single center between 2008 and 2015. They developed clinical decision trees using the CHAID algorithm (Chi squared Automatic Interaction Detection) to analyze risk factors for resistance associated with three antibiotics: piperacillin-tazobactam (PT), cefepime (CE), and meropenem (ME).

Overall, resistance rates to PT, CE, and ME were 29%, 22%, and 9%, respectively, and 6.6% of the isolates were resistant to all three antibiotics.

Factors associated with increased resistance risk included residence in a nursing home, transfer from an outside hospital, and prior antibiotics use. Resistance to ME was associated with infection with Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter spp, the researchers noted, and resistance to PT was associated with central nervous system and central venous catheter infections.

Clinical decision trees were able to separate patients at low risk for resistance to PT and CE, as well as those with a risk greater than 30% of resistance to PT, CE, or ME. “We also found good overall agreement between the accuracies of the [multivariable logistic regression] models and the decision tree analyses for predicting antibiotic resistance,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of data from a single center and incomplete reporting of previous antibiotic exposure, the researchers noted. However, the results “provide a framework for how empiric antibiotics can be tailored according to decision tree patient clusters,” they said.

Combining user-friendly clinical decision trees and multivariable logistic regression models may offer the best opportunities for hospitals to derive local models to help with antimicrobial prescription.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The model found prevalence rates for resistance to piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, and meropenem of 28.6%, 21.8%, and 8.5%, respectively.

Data source: A review of 1,618 adults with sepsis.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

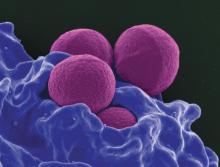

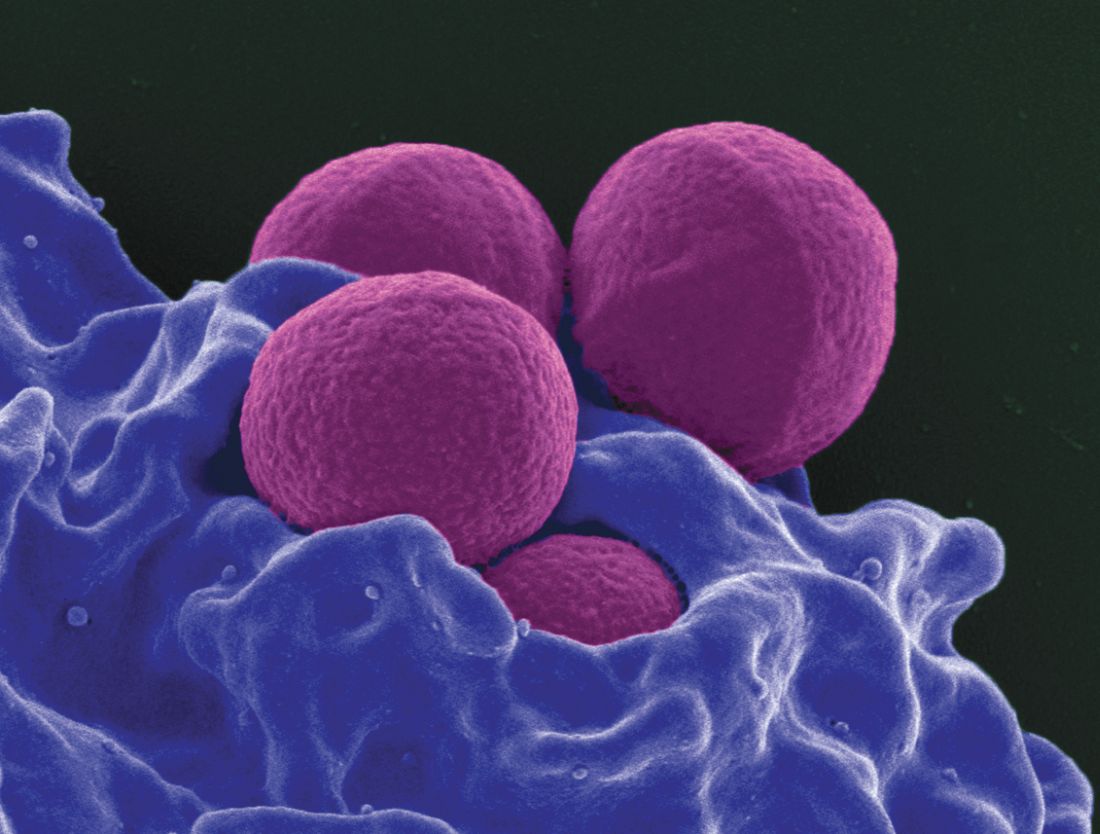

Adding cefepime to vancomycin improved MRSA bacteremia outcomes

NEW ORLEANS – Compared with vancomycin monotherapy, vancomycin combined with cefepime improved some outcomes for patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections, a retrospective study of 109 patients revealed.

A lower likelihood of microbiological failure and fewer bloodstream infections persisting 7 days or more were the notable differences between treatment groups.

All patients had at least 72 hours of vancomycin therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia confirmed by blood culture. During 2008-2015, 38 adults received vancomycin monotherapy and 71 received vancomycin plus 24 hours or more of cefepime.

Compared with monotherapy, the combination treatment was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in the primary composite treatment failure outcome of 30-day all-cause mortality, in bacteremia duration of 7 days or more, and in 60-day bloodstream-infection recurrence: 55% for monotherapy versus 42% for combination therapy (P = .195). The difference was primarily associated with decreased duration of sepsis and fewer MRSA bloodstream infections persisting 7 days or more in the combination cohort.

Rates of bacteremia duration of 7 days or more were 42% in monotherapy patients and 20% in combination patients (P = .013). Differences in 60-day bloodstream-infection recurrence were nonsignificant, 8% versus 4%, respectively (P = .42).

Thirty-day mortality, however, was lower among monotherapy patients than combination patients – 13% vs. 25% – although the difference was nonsignificant (P = .21).

“From what I see here … it seems like they will have a lower duration of bacteremia, which is always great,” Ms. Atwan said. “You want to decrease length of stay in the hospital,” which will cut down on costs and on patients’ risks of getting more infections.

Although the primary outcome was a composite endpoint, “when we looked at them separately, we found the patients in the combination group had more mortality,” Ms. Atwan said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. “That surprised me initially. But those patients are sicker and more likely to get dual coverage.”

The investigators confirmed the association between the severity of MRSA bacteremia and combination therapy by looking at Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) scores. The median APACHE score was 23 in the combination group, compared with 13.5 in the monotherapy group (P = 0003). Higher APACHE scores were associated with greater odds of meeting the composite failure endpoint (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08) and of developing endocarditis (aOR, 3.6) in multivariate analyses.

More patients in the combination group had pneumonia as the primary source of infection than did patients in the monotherapy group: 54% vs. 29% (P = .016). Further, more of them had skin or soft tissue infections as the primary infection source: 29% vs. 13% (P = .036).

Although the exact mechanism remains unknown, synergy between the two agents could be caused by an increase in penicillin-binding proteins, Ms. Atwan said.

The study is still ongoing; Ms. Atwan hopes additional patients and data will lead to statistically significant differences between the outcomes of combination therapy and vancomycin monotherapy.

“I want to say that combination therapy is something you will always want to go to when you have a sicker patient, but I can’t really tell you that combination therapy is going to cause better outcomes for your patient,” she cautioned. “Hopefully, I can by the end of the study.”

In the meantime, “it looks like vancomycin and beta-lactams could be beneficial for MRSA bacteremia,” she added.

The researchers noted that although vancomycin monotherapy is a mainstay of treatment for MRSA bloodstream infections, emergence of reduced susceptibility and treatment failures warrants other therapeutic strategies.

Ms. Atwan had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Compared with vancomycin monotherapy, vancomycin combined with cefepime improved some outcomes for patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections, a retrospective study of 109 patients revealed.

A lower likelihood of microbiological failure and fewer bloodstream infections persisting 7 days or more were the notable differences between treatment groups.

All patients had at least 72 hours of vancomycin therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia confirmed by blood culture. During 2008-2015, 38 adults received vancomycin monotherapy and 71 received vancomycin plus 24 hours or more of cefepime.

Compared with monotherapy, the combination treatment was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in the primary composite treatment failure outcome of 30-day all-cause mortality, in bacteremia duration of 7 days or more, and in 60-day bloodstream-infection recurrence: 55% for monotherapy versus 42% for combination therapy (P = .195). The difference was primarily associated with decreased duration of sepsis and fewer MRSA bloodstream infections persisting 7 days or more in the combination cohort.

Rates of bacteremia duration of 7 days or more were 42% in monotherapy patients and 20% in combination patients (P = .013). Differences in 60-day bloodstream-infection recurrence were nonsignificant, 8% versus 4%, respectively (P = .42).

Thirty-day mortality, however, was lower among monotherapy patients than combination patients – 13% vs. 25% – although the difference was nonsignificant (P = .21).

“From what I see here … it seems like they will have a lower duration of bacteremia, which is always great,” Ms. Atwan said. “You want to decrease length of stay in the hospital,” which will cut down on costs and on patients’ risks of getting more infections.

Although the primary outcome was a composite endpoint, “when we looked at them separately, we found the patients in the combination group had more mortality,” Ms. Atwan said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. “That surprised me initially. But those patients are sicker and more likely to get dual coverage.”

The investigators confirmed the association between the severity of MRSA bacteremia and combination therapy by looking at Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) scores. The median APACHE score was 23 in the combination group, compared with 13.5 in the monotherapy group (P = 0003). Higher APACHE scores were associated with greater odds of meeting the composite failure endpoint (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08) and of developing endocarditis (aOR, 3.6) in multivariate analyses.

More patients in the combination group had pneumonia as the primary source of infection than did patients in the monotherapy group: 54% vs. 29% (P = .016). Further, more of them had skin or soft tissue infections as the primary infection source: 29% vs. 13% (P = .036).

Although the exact mechanism remains unknown, synergy between the two agents could be caused by an increase in penicillin-binding proteins, Ms. Atwan said.

The study is still ongoing; Ms. Atwan hopes additional patients and data will lead to statistically significant differences between the outcomes of combination therapy and vancomycin monotherapy.

“I want to say that combination therapy is something you will always want to go to when you have a sicker patient, but I can’t really tell you that combination therapy is going to cause better outcomes for your patient,” she cautioned. “Hopefully, I can by the end of the study.”

In the meantime, “it looks like vancomycin and beta-lactams could be beneficial for MRSA bacteremia,” she added.

The researchers noted that although vancomycin monotherapy is a mainstay of treatment for MRSA bloodstream infections, emergence of reduced susceptibility and treatment failures warrants other therapeutic strategies.

Ms. Atwan had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Compared with vancomycin monotherapy, vancomycin combined with cefepime improved some outcomes for patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections, a retrospective study of 109 patients revealed.

A lower likelihood of microbiological failure and fewer bloodstream infections persisting 7 days or more were the notable differences between treatment groups.

All patients had at least 72 hours of vancomycin therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia confirmed by blood culture. During 2008-2015, 38 adults received vancomycin monotherapy and 71 received vancomycin plus 24 hours or more of cefepime.

Compared with monotherapy, the combination treatment was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in the primary composite treatment failure outcome of 30-day all-cause mortality, in bacteremia duration of 7 days or more, and in 60-day bloodstream-infection recurrence: 55% for monotherapy versus 42% for combination therapy (P = .195). The difference was primarily associated with decreased duration of sepsis and fewer MRSA bloodstream infections persisting 7 days or more in the combination cohort.

Rates of bacteremia duration of 7 days or more were 42% in monotherapy patients and 20% in combination patients (P = .013). Differences in 60-day bloodstream-infection recurrence were nonsignificant, 8% versus 4%, respectively (P = .42).

Thirty-day mortality, however, was lower among monotherapy patients than combination patients – 13% vs. 25% – although the difference was nonsignificant (P = .21).

“From what I see here … it seems like they will have a lower duration of bacteremia, which is always great,” Ms. Atwan said. “You want to decrease length of stay in the hospital,” which will cut down on costs and on patients’ risks of getting more infections.

Although the primary outcome was a composite endpoint, “when we looked at them separately, we found the patients in the combination group had more mortality,” Ms. Atwan said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. “That surprised me initially. But those patients are sicker and more likely to get dual coverage.”

The investigators confirmed the association between the severity of MRSA bacteremia and combination therapy by looking at Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) scores. The median APACHE score was 23 in the combination group, compared with 13.5 in the monotherapy group (P = 0003). Higher APACHE scores were associated with greater odds of meeting the composite failure endpoint (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08) and of developing endocarditis (aOR, 3.6) in multivariate analyses.

More patients in the combination group had pneumonia as the primary source of infection than did patients in the monotherapy group: 54% vs. 29% (P = .016). Further, more of them had skin or soft tissue infections as the primary infection source: 29% vs. 13% (P = .036).

Although the exact mechanism remains unknown, synergy between the two agents could be caused by an increase in penicillin-binding proteins, Ms. Atwan said.

The study is still ongoing; Ms. Atwan hopes additional patients and data will lead to statistically significant differences between the outcomes of combination therapy and vancomycin monotherapy.

“I want to say that combination therapy is something you will always want to go to when you have a sicker patient, but I can’t really tell you that combination therapy is going to cause better outcomes for your patient,” she cautioned. “Hopefully, I can by the end of the study.”

In the meantime, “it looks like vancomycin and beta-lactams could be beneficial for MRSA bacteremia,” she added.

The researchers noted that although vancomycin monotherapy is a mainstay of treatment for MRSA bloodstream infections, emergence of reduced susceptibility and treatment failures warrants other therapeutic strategies.

Ms. Atwan had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median duration of MRSA bacteremia was 4 days with combination therapy, versus 6 days with vancomycin alone.

Data source: A retrospective, single-center comparison of 109 patients treated with either vancomycin plus cefepime or vancomycin alone.

Disclosures: Safana M. Atwan had no relevant financial disclosures.

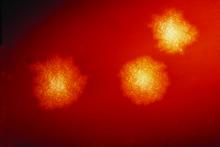

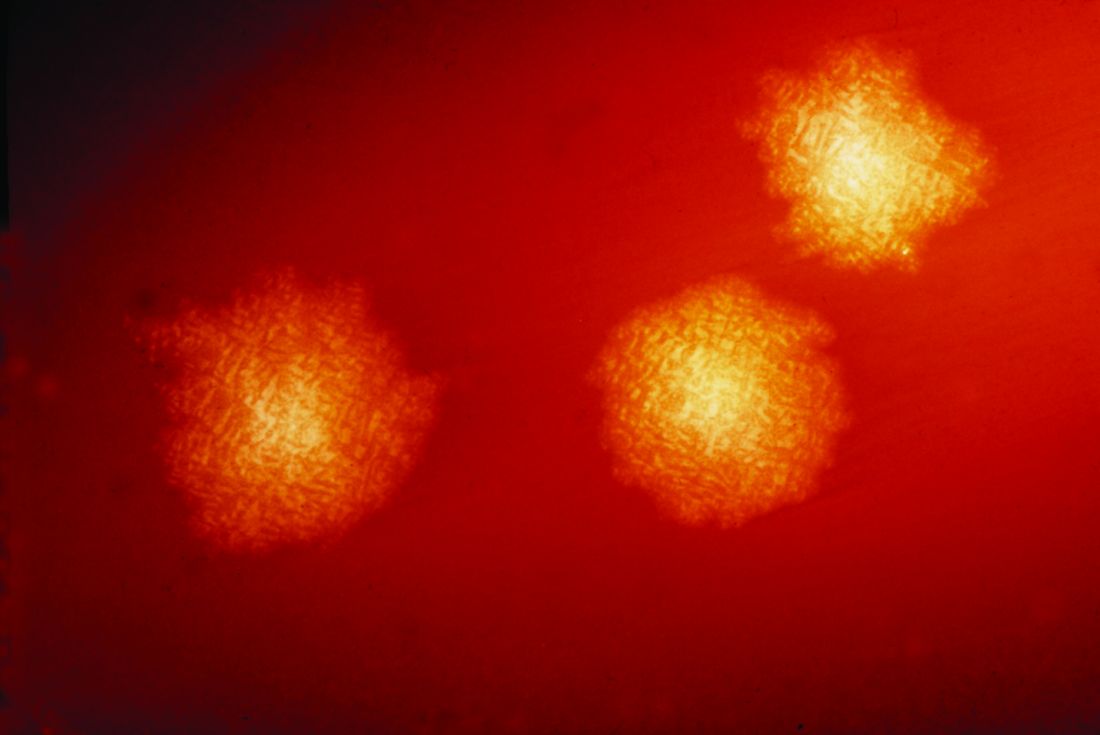

New C. difficile drug shows promise

Ridinilazole, a new antibiotic for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) proved noninferior to vancomycin, showing promise especially in lower recurrence risk, according to a study funded in part by ridinilazole manufacturer Summit Therapeutics.

In a phase 2, 1:1 randomized, double-blind trial of 69 CDI patients, 24 of 36 (66.7%) ridinilazole patients reported a sustained clinical response, compared with 14 of 33 vancomycin patients (42.4%), indicating statistical noninferiority – and even superiority at the upper confidence level – of ridinilazole (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[17]30235-9).

Over the course of 10 days, investigators gave the ridinilazole group 200 mg orally twice per day, as well as two placebo doses. Those in the vancomycin group took 125 mg orally four times per day.

Investigators assessed both groups on days 4-6, 10-11, 12-14, and routine weekly follow-ups until 30 days after treatment.

Most of the patients were white females, with an average age of 58 years for the ridinilazole group, and 56 years for the vancomycin group.

Ridinilazole correlated with more sustained clinical responses across almost all subgroups as well, including with treatment differences (respectively) of 42.7%, 15.9%, 19.9%, and 8.9% for those over 75 years, with a more severe diagnosis, more than one previous CDI episode, and those taking other antibiotics before study participation, according to the investigators. Both groups saw similar rates of adverse events related to treatment.

The outcome of this trial could be significant in reducing recurrence risk in CDI patients, which occurs in up to 30% of patients after first treatment, and can increase up to 65% after multiple reinfections, according to Richard Vickers, PhD, chief scientific officer on antimicrobials at Summit Therapeutics PLC, and his fellow investigators.

CDI patients also are subject to significantly higher inpatient mortality, spend longer periods in intensive care, and have higher rates of all-cause readmission over 3 months than do matched controls, the investigators noted.

Unlike the three common CDI drugs on the market, metronidazole, vancomycin, and fidaxomicin, ridinilazole is restricted to the gastrointestinal tract and, according to the investigators, has shown encouraging results in previous studies.

“In vitro studies have shown its high inhibitory activity against C. difficile and minimal activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic intestinal microorganisms,” they wrote. “In a phase 1 study, ridinilazole was safe and well tolerated in healthy human volunteers, with little systemic absorption and little effect on normal gut microbiota.”

They asserted it was this lack of effect that caused the drug to show success in phase 2, noting ridinilazole’s superiority was “likely to be due to the highly selective activity of ridinilazole against CDI and the absence of collateral damage to the microbiota during therapy.”

The study was limited by its sample, which was younger and had a milder form of CDI than is usually represented. The study also formed its power calculations based on the original sample size of 100, and not the adjusted, intended-to-treat population of 69 which became its primary analysis.

Finally, the investigators advised further trials be conducted with a follow-up schedule longer than 30 days.

Dr. Vickers, Dr. Bina Tejura, and Dr. David Roblin reported working for Summit Therapeutics, the drug manufacturer, and hold share options with the company. Other authors reported holding close relationships with other, similar drug manufacturing companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

With a 30-day mortality margin of 9%-38% and recurrence risk baseline of 15%-25%, Clostridium difficile infection continues to be a significant global problem. Yet, for decades there had only been a minimal number of drugs available to treat this disease, namely metronidazole and vancomycin.

As new resistant strains of this disease phased out metronidazole, even in mild cases, fidaxomicin emerged as an adequate replacement, although it was soon clear that because of its high price, fidaxomicin would remain as an initial treatment, disadvantaging those with multiple episodes.

This lack of reliable, effective antimicrobials puts into sharp relief the need for new drug development, and ridinilazole may be a step in the right direction.

While the study conducted by Richard Vickers and colleagues was limited by a slightly younger sample with a milder form of the disease than a true representative sample, the superior recurrence reduction related to ridinilazole is an advantage.

It is important that we build upon this study, and push further to expand the array of tools we have to fight C. difficile to optimize treatment for patients at all stages of this disease.

Simon D. Goldenberg, MBBS, MSc, FRCPath, MD, DipHIC, is a consultant microbiologist at the Centre for Clinical Infection and Diagnostics Research, King’s College London. He has received grants and personal fees from Astellas, BD, Luminex, Abbott, Orion Diagnostics, Qiagen, MSD, and DNA electronics.

With a 30-day mortality margin of 9%-38% and recurrence risk baseline of 15%-25%, Clostridium difficile infection continues to be a significant global problem. Yet, for decades there had only been a minimal number of drugs available to treat this disease, namely metronidazole and vancomycin.

As new resistant strains of this disease phased out metronidazole, even in mild cases, fidaxomicin emerged as an adequate replacement, although it was soon clear that because of its high price, fidaxomicin would remain as an initial treatment, disadvantaging those with multiple episodes.

This lack of reliable, effective antimicrobials puts into sharp relief the need for new drug development, and ridinilazole may be a step in the right direction.

While the study conducted by Richard Vickers and colleagues was limited by a slightly younger sample with a milder form of the disease than a true representative sample, the superior recurrence reduction related to ridinilazole is an advantage.

It is important that we build upon this study, and push further to expand the array of tools we have to fight C. difficile to optimize treatment for patients at all stages of this disease.

Simon D. Goldenberg, MBBS, MSc, FRCPath, MD, DipHIC, is a consultant microbiologist at the Centre for Clinical Infection and Diagnostics Research, King’s College London. He has received grants and personal fees from Astellas, BD, Luminex, Abbott, Orion Diagnostics, Qiagen, MSD, and DNA electronics.

With a 30-day mortality margin of 9%-38% and recurrence risk baseline of 15%-25%, Clostridium difficile infection continues to be a significant global problem. Yet, for decades there had only been a minimal number of drugs available to treat this disease, namely metronidazole and vancomycin.

As new resistant strains of this disease phased out metronidazole, even in mild cases, fidaxomicin emerged as an adequate replacement, although it was soon clear that because of its high price, fidaxomicin would remain as an initial treatment, disadvantaging those with multiple episodes.

This lack of reliable, effective antimicrobials puts into sharp relief the need for new drug development, and ridinilazole may be a step in the right direction.

While the study conducted by Richard Vickers and colleagues was limited by a slightly younger sample with a milder form of the disease than a true representative sample, the superior recurrence reduction related to ridinilazole is an advantage.

It is important that we build upon this study, and push further to expand the array of tools we have to fight C. difficile to optimize treatment for patients at all stages of this disease.

Simon D. Goldenberg, MBBS, MSc, FRCPath, MD, DipHIC, is a consultant microbiologist at the Centre for Clinical Infection and Diagnostics Research, King’s College London. He has received grants and personal fees from Astellas, BD, Luminex, Abbott, Orion Diagnostics, Qiagen, MSD, and DNA electronics.

Ridinilazole, a new antibiotic for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) proved noninferior to vancomycin, showing promise especially in lower recurrence risk, according to a study funded in part by ridinilazole manufacturer Summit Therapeutics.

In a phase 2, 1:1 randomized, double-blind trial of 69 CDI patients, 24 of 36 (66.7%) ridinilazole patients reported a sustained clinical response, compared with 14 of 33 vancomycin patients (42.4%), indicating statistical noninferiority – and even superiority at the upper confidence level – of ridinilazole (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[17]30235-9).

Over the course of 10 days, investigators gave the ridinilazole group 200 mg orally twice per day, as well as two placebo doses. Those in the vancomycin group took 125 mg orally four times per day.

Investigators assessed both groups on days 4-6, 10-11, 12-14, and routine weekly follow-ups until 30 days after treatment.

Most of the patients were white females, with an average age of 58 years for the ridinilazole group, and 56 years for the vancomycin group.

Ridinilazole correlated with more sustained clinical responses across almost all subgroups as well, including with treatment differences (respectively) of 42.7%, 15.9%, 19.9%, and 8.9% for those over 75 years, with a more severe diagnosis, more than one previous CDI episode, and those taking other antibiotics before study participation, according to the investigators. Both groups saw similar rates of adverse events related to treatment.

The outcome of this trial could be significant in reducing recurrence risk in CDI patients, which occurs in up to 30% of patients after first treatment, and can increase up to 65% after multiple reinfections, according to Richard Vickers, PhD, chief scientific officer on antimicrobials at Summit Therapeutics PLC, and his fellow investigators.

CDI patients also are subject to significantly higher inpatient mortality, spend longer periods in intensive care, and have higher rates of all-cause readmission over 3 months than do matched controls, the investigators noted.

Unlike the three common CDI drugs on the market, metronidazole, vancomycin, and fidaxomicin, ridinilazole is restricted to the gastrointestinal tract and, according to the investigators, has shown encouraging results in previous studies.

“In vitro studies have shown its high inhibitory activity against C. difficile and minimal activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic intestinal microorganisms,” they wrote. “In a phase 1 study, ridinilazole was safe and well tolerated in healthy human volunteers, with little systemic absorption and little effect on normal gut microbiota.”

They asserted it was this lack of effect that caused the drug to show success in phase 2, noting ridinilazole’s superiority was “likely to be due to the highly selective activity of ridinilazole against CDI and the absence of collateral damage to the microbiota during therapy.”

The study was limited by its sample, which was younger and had a milder form of CDI than is usually represented. The study also formed its power calculations based on the original sample size of 100, and not the adjusted, intended-to-treat population of 69 which became its primary analysis.

Finally, the investigators advised further trials be conducted with a follow-up schedule longer than 30 days.

Dr. Vickers, Dr. Bina Tejura, and Dr. David Roblin reported working for Summit Therapeutics, the drug manufacturer, and hold share options with the company. Other authors reported holding close relationships with other, similar drug manufacturing companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Ridinilazole, a new antibiotic for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) proved noninferior to vancomycin, showing promise especially in lower recurrence risk, according to a study funded in part by ridinilazole manufacturer Summit Therapeutics.

In a phase 2, 1:1 randomized, double-blind trial of 69 CDI patients, 24 of 36 (66.7%) ridinilazole patients reported a sustained clinical response, compared with 14 of 33 vancomycin patients (42.4%), indicating statistical noninferiority – and even superiority at the upper confidence level – of ridinilazole (Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[17]30235-9).

Over the course of 10 days, investigators gave the ridinilazole group 200 mg orally twice per day, as well as two placebo doses. Those in the vancomycin group took 125 mg orally four times per day.

Investigators assessed both groups on days 4-6, 10-11, 12-14, and routine weekly follow-ups until 30 days after treatment.

Most of the patients were white females, with an average age of 58 years for the ridinilazole group, and 56 years for the vancomycin group.

Ridinilazole correlated with more sustained clinical responses across almost all subgroups as well, including with treatment differences (respectively) of 42.7%, 15.9%, 19.9%, and 8.9% for those over 75 years, with a more severe diagnosis, more than one previous CDI episode, and those taking other antibiotics before study participation, according to the investigators. Both groups saw similar rates of adverse events related to treatment.

The outcome of this trial could be significant in reducing recurrence risk in CDI patients, which occurs in up to 30% of patients after first treatment, and can increase up to 65% after multiple reinfections, according to Richard Vickers, PhD, chief scientific officer on antimicrobials at Summit Therapeutics PLC, and his fellow investigators.

CDI patients also are subject to significantly higher inpatient mortality, spend longer periods in intensive care, and have higher rates of all-cause readmission over 3 months than do matched controls, the investigators noted.

Unlike the three common CDI drugs on the market, metronidazole, vancomycin, and fidaxomicin, ridinilazole is restricted to the gastrointestinal tract and, according to the investigators, has shown encouraging results in previous studies.

“In vitro studies have shown its high inhibitory activity against C. difficile and minimal activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic intestinal microorganisms,” they wrote. “In a phase 1 study, ridinilazole was safe and well tolerated in healthy human volunteers, with little systemic absorption and little effect on normal gut microbiota.”

They asserted it was this lack of effect that caused the drug to show success in phase 2, noting ridinilazole’s superiority was “likely to be due to the highly selective activity of ridinilazole against CDI and the absence of collateral damage to the microbiota during therapy.”

The study was limited by its sample, which was younger and had a milder form of CDI than is usually represented. The study also formed its power calculations based on the original sample size of 100, and not the adjusted, intended-to-treat population of 69 which became its primary analysis.

Finally, the investigators advised further trials be conducted with a follow-up schedule longer than 30 days.

Dr. Vickers, Dr. Bina Tejura, and Dr. David Roblin reported working for Summit Therapeutics, the drug manufacturer, and hold share options with the company. Other authors reported holding close relationships with other, similar drug manufacturing companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 24 of 36 (66.7%) of the ridinilazole patients showed sustained clinical response, compared with 14 of 33 (42.4%) of vancomycin patients, proving ridinilazole noninferior (treatment difference: 21.1%, CI, 90% [3.1-39.1] P = .0004).

Data source: A phase 2, double-blind, randomized noninferiority study of 69 patients gathered from 21 North American sites between June 16, 2014, and Aug. 31, 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Richard Vickers, Dr. Bina Tejura, and Dr. David Roblin reported working for Summit Therapeutics, the drug manufacturer, and hold share options with the company. Other authors reported holding close relationships with other, similar drug manufacturing companies.

The burden of health care–associated C. difficile infection in a nonmetropolitan setting

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) remains a major cause of health care–associated diarrhea in industrialized countries and is a common target of antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs).

While the burden of CDI has been well described in tertiary metropolitan hospitals, there is a lack of published evidence from regional and rural hospitals. Our recent study published in the Journal of Hospital Infection explores the effect of an ASP on health care–associated CDI rates and the impact of CDI on length of stay and hospital costs.

The ASP functioned alongside infection control practices, including isolation of patients with antimicrobial-resistant organisms (including C. difficile), hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, and terminal cleaning. Timely feedback emails to medical officers contained information on patient-specific risk factors for CDI, current and prior antimicrobials, and suggestions for CDI treatment. The effect of health care–associated CDI on length of stay and hospital costs was investigated using a group of matched controls, identified retrospectively using hospital performance data. Prior antimicrobial and proton pump inhibitor use were also measured and compared with background use.

The results of our study demonstrated a stable health care–associated CDI rate of around four cases per 10,000 occupied bed days over a 5-year period, similar to the average Australian rate. The length of time over which CDI rates could be effectively examined prior to the intervention was limited by changes to C. difficile stool testing methods. Median length of stay was 11 days greater, and median hospital costs were AU$11,361 higher for patients with health care–associated CDI (n = 91) than for their matched controls (n = 172). It is likely that the increase in costs was associated with additional length of stay but also with increased investigation and treatment costs. Among the group of patients with severe disease (n = 8), only four received oral vancomycin according to Australian guidelines, possibly because of under-recognition of severity criteria. The response rate to emails was low at 19%, showing that other methods are additionally necessary to communicate CDI case feedback.

Third generation cephalosporins and beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations were over-represented in the health care–associated CDI group, where narrower spectrum antimicrobials such as beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins were under represented. Rates of prior antimicrobial use and proton pump inhibitor use were broadly in agreement with the literature.

Our study demonstrated that, in the Australian nonmetropolitan setting, there was a high burden of health care–associated CDI in terms of hospital costs and length of stay, even though our health district experienced CDI rates that were similar to the Australian average. Challenges associated with the study included maintenance of consistent data collection across multiple hospital sites without comprehensive electronic medical records, provision of timely email feedback, and dissemination of study results.

Analysis of prior antimicrobial use has allowed us to identify targets for ongoing antimicrobial stewardship activities, and we also intend to provide further education on recognition of severity criteria. These activities can be supported through daily antimicrobial stewardship ward rounds. Future research could involve application of appropriateness criteria to prior and current antimicrobial use in CDI patients in order to identify avoidable cases and use of more advanced statistical techniques such as multistate modeling to determine differences in outcomes between cases and controls.

Stuart Bond, BPharm, DipPharmPrac, is an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist based at Wollongong Hospital in New South Wales, Australia.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) remains a major cause of health care–associated diarrhea in industrialized countries and is a common target of antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs).

While the burden of CDI has been well described in tertiary metropolitan hospitals, there is a lack of published evidence from regional and rural hospitals. Our recent study published in the Journal of Hospital Infection explores the effect of an ASP on health care–associated CDI rates and the impact of CDI on length of stay and hospital costs.

The ASP functioned alongside infection control practices, including isolation of patients with antimicrobial-resistant organisms (including C. difficile), hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, and terminal cleaning. Timely feedback emails to medical officers contained information on patient-specific risk factors for CDI, current and prior antimicrobials, and suggestions for CDI treatment. The effect of health care–associated CDI on length of stay and hospital costs was investigated using a group of matched controls, identified retrospectively using hospital performance data. Prior antimicrobial and proton pump inhibitor use were also measured and compared with background use.

The results of our study demonstrated a stable health care–associated CDI rate of around four cases per 10,000 occupied bed days over a 5-year period, similar to the average Australian rate. The length of time over which CDI rates could be effectively examined prior to the intervention was limited by changes to C. difficile stool testing methods. Median length of stay was 11 days greater, and median hospital costs were AU$11,361 higher for patients with health care–associated CDI (n = 91) than for their matched controls (n = 172). It is likely that the increase in costs was associated with additional length of stay but also with increased investigation and treatment costs. Among the group of patients with severe disease (n = 8), only four received oral vancomycin according to Australian guidelines, possibly because of under-recognition of severity criteria. The response rate to emails was low at 19%, showing that other methods are additionally necessary to communicate CDI case feedback.

Third generation cephalosporins and beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations were over-represented in the health care–associated CDI group, where narrower spectrum antimicrobials such as beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins were under represented. Rates of prior antimicrobial use and proton pump inhibitor use were broadly in agreement with the literature.

Our study demonstrated that, in the Australian nonmetropolitan setting, there was a high burden of health care–associated CDI in terms of hospital costs and length of stay, even though our health district experienced CDI rates that were similar to the Australian average. Challenges associated with the study included maintenance of consistent data collection across multiple hospital sites without comprehensive electronic medical records, provision of timely email feedback, and dissemination of study results.

Analysis of prior antimicrobial use has allowed us to identify targets for ongoing antimicrobial stewardship activities, and we also intend to provide further education on recognition of severity criteria. These activities can be supported through daily antimicrobial stewardship ward rounds. Future research could involve application of appropriateness criteria to prior and current antimicrobial use in CDI patients in order to identify avoidable cases and use of more advanced statistical techniques such as multistate modeling to determine differences in outcomes between cases and controls.

Stuart Bond, BPharm, DipPharmPrac, is an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist based at Wollongong Hospital in New South Wales, Australia.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) remains a major cause of health care–associated diarrhea in industrialized countries and is a common target of antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs).

While the burden of CDI has been well described in tertiary metropolitan hospitals, there is a lack of published evidence from regional and rural hospitals. Our recent study published in the Journal of Hospital Infection explores the effect of an ASP on health care–associated CDI rates and the impact of CDI on length of stay and hospital costs.

The ASP functioned alongside infection control practices, including isolation of patients with antimicrobial-resistant organisms (including C. difficile), hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, and terminal cleaning. Timely feedback emails to medical officers contained information on patient-specific risk factors for CDI, current and prior antimicrobials, and suggestions for CDI treatment. The effect of health care–associated CDI on length of stay and hospital costs was investigated using a group of matched controls, identified retrospectively using hospital performance data. Prior antimicrobial and proton pump inhibitor use were also measured and compared with background use.

The results of our study demonstrated a stable health care–associated CDI rate of around four cases per 10,000 occupied bed days over a 5-year period, similar to the average Australian rate. The length of time over which CDI rates could be effectively examined prior to the intervention was limited by changes to C. difficile stool testing methods. Median length of stay was 11 days greater, and median hospital costs were AU$11,361 higher for patients with health care–associated CDI (n = 91) than for their matched controls (n = 172). It is likely that the increase in costs was associated with additional length of stay but also with increased investigation and treatment costs. Among the group of patients with severe disease (n = 8), only four received oral vancomycin according to Australian guidelines, possibly because of under-recognition of severity criteria. The response rate to emails was low at 19%, showing that other methods are additionally necessary to communicate CDI case feedback.

Third generation cephalosporins and beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations were over-represented in the health care–associated CDI group, where narrower spectrum antimicrobials such as beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins were under represented. Rates of prior antimicrobial use and proton pump inhibitor use were broadly in agreement with the literature.

Our study demonstrated that, in the Australian nonmetropolitan setting, there was a high burden of health care–associated CDI in terms of hospital costs and length of stay, even though our health district experienced CDI rates that were similar to the Australian average. Challenges associated with the study included maintenance of consistent data collection across multiple hospital sites without comprehensive electronic medical records, provision of timely email feedback, and dissemination of study results.

Analysis of prior antimicrobial use has allowed us to identify targets for ongoing antimicrobial stewardship activities, and we also intend to provide further education on recognition of severity criteria. These activities can be supported through daily antimicrobial stewardship ward rounds. Future research could involve application of appropriateness criteria to prior and current antimicrobial use in CDI patients in order to identify avoidable cases and use of more advanced statistical techniques such as multistate modeling to determine differences in outcomes between cases and controls.

Stuart Bond, BPharm, DipPharmPrac, is an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist based at Wollongong Hospital in New South Wales, Australia.

Hospital isolates C. difficile carriers and rates drop

NEW ORLEANS – A Montreal hospital grappling with high Clostridium difficile infections rates launched an intervention in October 2013 to screen patients at admission and detect asymptomatic carriers, and investigators found 4.8% of 7,599 people admitted through the ED over 15 months were carriers of C. difficile.

To protect Jewish General Hospital physicians, staff and other patients from potential transmission, these patients were placed in isolation. However, because they were fairly numerous – 1 in 20 admissions – and because infectious disease (ID) experts feared a substantial backlash, these patients were put in less restrictive isolation. They were permitted to share rooms as long as the dividing curtains remained drawn, for example. In addition, clinicians could skip wearing traditional isolation hats and gowns.

The ID team at the hospital considered the intervention a success. “It is estimated we prevented 64 cases over 15 months,” Dr. Longtin said during a packed session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

The hospital’s C. difficile rate dropped from 6.9 per 10,000 patient-days before the screening and isolation protocol to 3.0 per 10,000 during the intervention. The difference was statically significant (P less than .001).

“Compared to other hospitals in the province, we used to be in the middle of the pack [for C. difficile infection rates], and now we are the lowest,” Dr. Longtin said.

Asymptomatic carriers were detected using rectal sampling with sterile swab and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Testing was performed 7 days a week and analyzed once daily, with results generated within 24 hours and documented in the patient chart. Only patients admitted through the ED were screened, which prompted some questions from colleagues, Dr. Longtin said. However, he defends this approach because the 30% or so of patients admitted from the ED tend to spend more days on the ward. The risk of becoming colonized increases steadily with duration of hospitalization. This occurs despite isolating patients with C. difficile infection. Initial results of the study were published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016 Jun 1;176[6]:796-804).

Risk to health care workers

C. difficile carriers are contagious, but not as much as people with C. difficile infection, Dr. Longtin said. In one study, the microorganism was present on the skin of 61% of symptomatic carriers versus 78% of those infected (Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 15;45[8]:992-8). In addition, C. difficile present on patient skin can be transferred to health care worker hands, even up to 6 weeks after resolution of associated diarrhea (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;37[4]:475-7).

Prior to the intervention, C. difficile prevention at Jewish General involved guidelines that “have not really changed in the last 20 years,” Dr. Longtin said. Contact precautions around infected patients, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship were the main strategies.

“Despite all these measures, we were not completely blocking dissemination of C difficile in our hospital,” Dr. Longtin said. He added that soap and water are better than alcohol for C. difficile, “but honestly not very good. Even the best hand hygiene technique is poorly effective to remove C. difficile. On the other hand – get it? – gloves are very effective. We felt we had to combine hand washing with gloves.”

Hand hygiene compliance increased from 37% to 50% during the intervention, and Dr. Longtin expected further improvements over time.

Risk to other patients

“Transmission of C. difficile cannot only be explained by infected patients in a hospital, so likely carriers also play a role,” Dr. Longtin said.

Another set of investigators found that hospital patients exposed to a carrier of C. difficile had nearly twice the risk of acquiring the infection (odds ratio, 1.79) (Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152[5]:1031-41.e2).

“For every patient with C. difficile infection, it’s estimated there are 5-7 C. difficile carriers, so they are numerous as well,” he said.

The bigger picture

During the study period, the C. difficile infection trends did not significantly change on the city level, further supporting the effectiveness of the carrier screen-and-isolate strategy.

There was slight increase in antibiotic use during the intervention period, Dr. Longtin said. “The only type of antibiotics that really decreased were vancomycin and metronidazole... which suggests in turn there were fewer cases of C. difficile infection.”

Long-term follow-up is ongoing, Dr. Longtin said. “We have more than 3 years of intervention. In the past year, our rate was 2.2 per 10,000 patient-days.”

Unanswered questions include the generalizability of the results “because we’re a very pro–infection control hospital,” he said. In addition, a formal cost-benefit analysis of this strategy would be worthwhile in the future.

Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

NEW ORLEANS – A Montreal hospital grappling with high Clostridium difficile infections rates launched an intervention in October 2013 to screen patients at admission and detect asymptomatic carriers, and investigators found 4.8% of 7,599 people admitted through the ED over 15 months were carriers of C. difficile.

To protect Jewish General Hospital physicians, staff and other patients from potential transmission, these patients were placed in isolation. However, because they were fairly numerous – 1 in 20 admissions – and because infectious disease (ID) experts feared a substantial backlash, these patients were put in less restrictive isolation. They were permitted to share rooms as long as the dividing curtains remained drawn, for example. In addition, clinicians could skip wearing traditional isolation hats and gowns.

The ID team at the hospital considered the intervention a success. “It is estimated we prevented 64 cases over 15 months,” Dr. Longtin said during a packed session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

The hospital’s C. difficile rate dropped from 6.9 per 10,000 patient-days before the screening and isolation protocol to 3.0 per 10,000 during the intervention. The difference was statically significant (P less than .001).

“Compared to other hospitals in the province, we used to be in the middle of the pack [for C. difficile infection rates], and now we are the lowest,” Dr. Longtin said.

Asymptomatic carriers were detected using rectal sampling with sterile swab and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Testing was performed 7 days a week and analyzed once daily, with results generated within 24 hours and documented in the patient chart. Only patients admitted through the ED were screened, which prompted some questions from colleagues, Dr. Longtin said. However, he defends this approach because the 30% or so of patients admitted from the ED tend to spend more days on the ward. The risk of becoming colonized increases steadily with duration of hospitalization. This occurs despite isolating patients with C. difficile infection. Initial results of the study were published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016 Jun 1;176[6]:796-804).

Risk to health care workers

C. difficile carriers are contagious, but not as much as people with C. difficile infection, Dr. Longtin said. In one study, the microorganism was present on the skin of 61% of symptomatic carriers versus 78% of those infected (Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 15;45[8]:992-8). In addition, C. difficile present on patient skin can be transferred to health care worker hands, even up to 6 weeks after resolution of associated diarrhea (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;37[4]:475-7).

Prior to the intervention, C. difficile prevention at Jewish General involved guidelines that “have not really changed in the last 20 years,” Dr. Longtin said. Contact precautions around infected patients, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship were the main strategies.

“Despite all these measures, we were not completely blocking dissemination of C difficile in our hospital,” Dr. Longtin said. He added that soap and water are better than alcohol for C. difficile, “but honestly not very good. Even the best hand hygiene technique is poorly effective to remove C. difficile. On the other hand – get it? – gloves are very effective. We felt we had to combine hand washing with gloves.”

Hand hygiene compliance increased from 37% to 50% during the intervention, and Dr. Longtin expected further improvements over time.

Risk to other patients

“Transmission of C. difficile cannot only be explained by infected patients in a hospital, so likely carriers also play a role,” Dr. Longtin said.

Another set of investigators found that hospital patients exposed to a carrier of C. difficile had nearly twice the risk of acquiring the infection (odds ratio, 1.79) (Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152[5]:1031-41.e2).

“For every patient with C. difficile infection, it’s estimated there are 5-7 C. difficile carriers, so they are numerous as well,” he said.

The bigger picture

During the study period, the C. difficile infection trends did not significantly change on the city level, further supporting the effectiveness of the carrier screen-and-isolate strategy.

There was slight increase in antibiotic use during the intervention period, Dr. Longtin said. “The only type of antibiotics that really decreased were vancomycin and metronidazole... which suggests in turn there were fewer cases of C. difficile infection.”

Long-term follow-up is ongoing, Dr. Longtin said. “We have more than 3 years of intervention. In the past year, our rate was 2.2 per 10,000 patient-days.”

Unanswered questions include the generalizability of the results “because we’re a very pro–infection control hospital,” he said. In addition, a formal cost-benefit analysis of this strategy would be worthwhile in the future.

Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

NEW ORLEANS – A Montreal hospital grappling with high Clostridium difficile infections rates launched an intervention in October 2013 to screen patients at admission and detect asymptomatic carriers, and investigators found 4.8% of 7,599 people admitted through the ED over 15 months were carriers of C. difficile.

To protect Jewish General Hospital physicians, staff and other patients from potential transmission, these patients were placed in isolation. However, because they were fairly numerous – 1 in 20 admissions – and because infectious disease (ID) experts feared a substantial backlash, these patients were put in less restrictive isolation. They were permitted to share rooms as long as the dividing curtains remained drawn, for example. In addition, clinicians could skip wearing traditional isolation hats and gowns.

The ID team at the hospital considered the intervention a success. “It is estimated we prevented 64 cases over 15 months,” Dr. Longtin said during a packed session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

The hospital’s C. difficile rate dropped from 6.9 per 10,000 patient-days before the screening and isolation protocol to 3.0 per 10,000 during the intervention. The difference was statically significant (P less than .001).

“Compared to other hospitals in the province, we used to be in the middle of the pack [for C. difficile infection rates], and now we are the lowest,” Dr. Longtin said.

Asymptomatic carriers were detected using rectal sampling with sterile swab and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Testing was performed 7 days a week and analyzed once daily, with results generated within 24 hours and documented in the patient chart. Only patients admitted through the ED were screened, which prompted some questions from colleagues, Dr. Longtin said. However, he defends this approach because the 30% or so of patients admitted from the ED tend to spend more days on the ward. The risk of becoming colonized increases steadily with duration of hospitalization. This occurs despite isolating patients with C. difficile infection. Initial results of the study were published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016 Jun 1;176[6]:796-804).

Risk to health care workers

C. difficile carriers are contagious, but not as much as people with C. difficile infection, Dr. Longtin said. In one study, the microorganism was present on the skin of 61% of symptomatic carriers versus 78% of those infected (Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 15;45[8]:992-8). In addition, C. difficile present on patient skin can be transferred to health care worker hands, even up to 6 weeks after resolution of associated diarrhea (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;37[4]:475-7).

Prior to the intervention, C. difficile prevention at Jewish General involved guidelines that “have not really changed in the last 20 years,” Dr. Longtin said. Contact precautions around infected patients, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship were the main strategies.

“Despite all these measures, we were not completely blocking dissemination of C difficile in our hospital,” Dr. Longtin said. He added that soap and water are better than alcohol for C. difficile, “but honestly not very good. Even the best hand hygiene technique is poorly effective to remove C. difficile. On the other hand – get it? – gloves are very effective. We felt we had to combine hand washing with gloves.”

Hand hygiene compliance increased from 37% to 50% during the intervention, and Dr. Longtin expected further improvements over time.

Risk to other patients

“Transmission of C. difficile cannot only be explained by infected patients in a hospital, so likely carriers also play a role,” Dr. Longtin said.

Another set of investigators found that hospital patients exposed to a carrier of C. difficile had nearly twice the risk of acquiring the infection (odds ratio, 1.79) (Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152[5]:1031-41.e2).

“For every patient with C. difficile infection, it’s estimated there are 5-7 C. difficile carriers, so they are numerous as well,” he said.

The bigger picture

During the study period, the C. difficile infection trends did not significantly change on the city level, further supporting the effectiveness of the carrier screen-and-isolate strategy.

There was slight increase in antibiotic use during the intervention period, Dr. Longtin said. “The only type of antibiotics that really decreased were vancomycin and metronidazole... which suggests in turn there were fewer cases of C. difficile infection.”

Long-term follow-up is ongoing, Dr. Longtin said. “We have more than 3 years of intervention. In the past year, our rate was 2.2 per 10,000 patient-days.”

Unanswered questions include the generalizability of the results “because we’re a very pro–infection control hospital,” he said. In addition, a formal cost-benefit analysis of this strategy would be worthwhile in the future.

Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point: Identification and isolation of asymptomatic carriers of Clostridium difficile decreased a hospital’s infection rates over time.

Major finding: (P less than .001).

Data source: A study of 7,599 people screened at admission through the ED at an acute care hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

C. difficile travels on the soles of our shoes

NEW ORLEANS – For an explanation to the spread of Clostridium difficile, one needs to look to our soles.

Based on ribosomal analysis, C. difficile often is transmitted from the hospital into the community and back into the hospital on the soles of shoes, researchers have concluded, based on findings from thousands of samples from patients, hospital environments, and shoes.

Dr. Alam of the University of Houston College of Pharmacy and his colleagues collected thousands of samples from the state of Texas to see how C. difficile strains in the community are related to clinical strains in the hospital.

The researchers collected 3,109 stool samples from people hospitalized with C. difficile, another 1,697 swabs taken from environmental surfaces in hospitals across the state, plus another 400 samples taken from the soles of shoes of clinicians and non–health care workers.

C. difficile was found in 44% of clinical stool samples, 13% of high-touch hospital environment surfaces, and 26% of community shoe sole samples. Among these positive C. difficile samples, toxigenic strains were detected in 93% of patient samples, 66% of hospital environment swabs and 64% of shoe samples. Importantly, the most predominant toxigenic strains appeared in all three sample types.

“When we collected some hospital environmental samples, we saw the isolate ribotypes perfectly matched the patient samples,” Dr. Alam said.

Further, “we saw the exact same ribotypes on our shoe bottoms, from these community, nonclinical sources,” Dr. Alam said. “Apparently, it seems, these dangerous pathogens are everywhere.”

In fact, “we may have brought many different strains from all over the world here to this meeting,” he added. “When we are taking antibiotics, we are susceptible to these different strains.”

Hospitals are cleaned daily, “but how many of us care about the shoes” on those who walk through the hospital, he asked. “We are loading the hospital with Clostridium difficile, and the hospital environment is also loaded with Clostridium difficile so we are bringing it into the community. We are spreading it everywhere.”

“Maybe we are blaming the doctors, nurses, and other staff, but [we are] not thinking about our shoes,” Dr. Alam added.

NEW ORLEANS – For an explanation to the spread of Clostridium difficile, one needs to look to our soles.

Based on ribosomal analysis, C. difficile often is transmitted from the hospital into the community and back into the hospital on the soles of shoes, researchers have concluded, based on findings from thousands of samples from patients, hospital environments, and shoes.

Dr. Alam of the University of Houston College of Pharmacy and his colleagues collected thousands of samples from the state of Texas to see how C. difficile strains in the community are related to clinical strains in the hospital.

The researchers collected 3,109 stool samples from people hospitalized with C. difficile, another 1,697 swabs taken from environmental surfaces in hospitals across the state, plus another 400 samples taken from the soles of shoes of clinicians and non–health care workers.

C. difficile was found in 44% of clinical stool samples, 13% of high-touch hospital environment surfaces, and 26% of community shoe sole samples. Among these positive C. difficile samples, toxigenic strains were detected in 93% of patient samples, 66% of hospital environment swabs and 64% of shoe samples. Importantly, the most predominant toxigenic strains appeared in all three sample types.

“When we collected some hospital environmental samples, we saw the isolate ribotypes perfectly matched the patient samples,” Dr. Alam said.

Further, “we saw the exact same ribotypes on our shoe bottoms, from these community, nonclinical sources,” Dr. Alam said. “Apparently, it seems, these dangerous pathogens are everywhere.”

In fact, “we may have brought many different strains from all over the world here to this meeting,” he added. “When we are taking antibiotics, we are susceptible to these different strains.”

Hospitals are cleaned daily, “but how many of us care about the shoes” on those who walk through the hospital, he asked. “We are loading the hospital with Clostridium difficile, and the hospital environment is also loaded with Clostridium difficile so we are bringing it into the community. We are spreading it everywhere.”

“Maybe we are blaming the doctors, nurses, and other staff, but [we are] not thinking about our shoes,” Dr. Alam added.

NEW ORLEANS – For an explanation to the spread of Clostridium difficile, one needs to look to our soles.

Based on ribosomal analysis, C. difficile often is transmitted from the hospital into the community and back into the hospital on the soles of shoes, researchers have concluded, based on findings from thousands of samples from patients, hospital environments, and shoes.

Dr. Alam of the University of Houston College of Pharmacy and his colleagues collected thousands of samples from the state of Texas to see how C. difficile strains in the community are related to clinical strains in the hospital.

The researchers collected 3,109 stool samples from people hospitalized with C. difficile, another 1,697 swabs taken from environmental surfaces in hospitals across the state, plus another 400 samples taken from the soles of shoes of clinicians and non–health care workers.

C. difficile was found in 44% of clinical stool samples, 13% of high-touch hospital environment surfaces, and 26% of community shoe sole samples. Among these positive C. difficile samples, toxigenic strains were detected in 93% of patient samples, 66% of hospital environment swabs and 64% of shoe samples. Importantly, the most predominant toxigenic strains appeared in all three sample types.

“When we collected some hospital environmental samples, we saw the isolate ribotypes perfectly matched the patient samples,” Dr. Alam said.

Further, “we saw the exact same ribotypes on our shoe bottoms, from these community, nonclinical sources,” Dr. Alam said. “Apparently, it seems, these dangerous pathogens are everywhere.”

In fact, “we may have brought many different strains from all over the world here to this meeting,” he added. “When we are taking antibiotics, we are susceptible to these different strains.”

Hospitals are cleaned daily, “but how many of us care about the shoes” on those who walk through the hospital, he asked. “We are loading the hospital with Clostridium difficile, and the hospital environment is also loaded with Clostridium difficile so we are bringing it into the community. We are spreading it everywhere.”

“Maybe we are blaming the doctors, nurses, and other staff, but [we are] not thinking about our shoes,” Dr. Alam added.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point: Clostridium difficile transfer between the hospital and community and back could be driven in part by contaminated shoes.

Major finding: Toxigenic strains of C. difficile were found in 93% of patient samples, 66% of hospital environment swabs, and 64% of shoe samples.

Data source: Study of 3,109 stool samples from infected hospitalized patients, 1,697 hospital environmental surface swabs, and 400 samples from the soles of shoes.

Disclosures: Dr. Alam reported having no financial disclosures.

Burkholderia cepacia causes blood infection in older, sicker patients

Non–cystic fibrosis–related Burkholderia cepacia complex infections occurred almost exclusively in older hospitalized patients with serious comorbidities – and the majority were acquired in a health care setting, a large U.S. Veterans Health Administration database study has determined.

Despite the bacteria’s tendency to be multidrug-resistant, both fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were equally effective, as long as they were promptly initiated, Nadim G. El Chakhtoura, MD, and colleagues reported (Clin Infect Dis, 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix559).

“We consider that the approach to improve survival in B. cepacia complex (Bcc) bloodstream infections … should include controlling the source of infection and prompt initiation of effective antibiotic therapy,” wrote Dr. El Chakhtoura of Cleveland Hospitals University Medical Center, and associates.

They found 248 cases of Bcc blood infections among such patients. Most (98%) were older men (mean age 68 years) with serious chronic and acute illnesses. Diabetes was common (44%), as was hemodialysis (23%). Many (41%) had been on mechanical ventilation. The etiology of the infections reflected these clinical factors: Most (62%) were nosocomial, with 41% associated with a central venous line and 20% with pneumonia. Just 9% were community acquired, mostly associated with pneumonia and intravenous drug use.

About 85% of isolates underwent antibiotic susceptibility testing. Most (94%) were sensitive to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and 88% to levofloxacin. The next best choices were ceftazidime (72%) and meropenem (69%), although the authors pointed out that only 32 isolates were tested for that drug. Of the 60 tested for ticarcillin-clavulanate, 6% were sensitive.

The authors pointed out that the approximate 30% resistance rate to ceftazidime was concerning and unexpected.

Empiric therapy was considered inappropriate in 35%, and definitive therapy inappropriate in 11%. Having an infectious disease specialist involved with the case increased the chance that it would be treated appropriately (75% vs. 57%). Mortality was 16% at 14 days, 25% at 30 days, and 36% at 90 days. Older age, higher Charlson comorbidity index, higher Pitt bacteremia scores, and prior antibiotic treatment were independently associated with an increased risk of death, the researchers said.

Although the VA database comprises mostly of males, the review spanned so many years and comprised such a large cohort that the findings can probably be accurately extrapolated to a general population of patients, Dr. El Chakhtoura and associates added.

Dr. El Chakhtoura had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Non–cystic fibrosis–related Burkholderia cepacia complex infections occurred almost exclusively in older hospitalized patients with serious comorbidities – and the majority were acquired in a health care setting, a large U.S. Veterans Health Administration database study has determined.

Despite the bacteria’s tendency to be multidrug-resistant, both fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were equally effective, as long as they were promptly initiated, Nadim G. El Chakhtoura, MD, and colleagues reported (Clin Infect Dis, 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix559).

“We consider that the approach to improve survival in B. cepacia complex (Bcc) bloodstream infections … should include controlling the source of infection and prompt initiation of effective antibiotic therapy,” wrote Dr. El Chakhtoura of Cleveland Hospitals University Medical Center, and associates.

They found 248 cases of Bcc blood infections among such patients. Most (98%) were older men (mean age 68 years) with serious chronic and acute illnesses. Diabetes was common (44%), as was hemodialysis (23%). Many (41%) had been on mechanical ventilation. The etiology of the infections reflected these clinical factors: Most (62%) were nosocomial, with 41% associated with a central venous line and 20% with pneumonia. Just 9% were community acquired, mostly associated with pneumonia and intravenous drug use.

About 85% of isolates underwent antibiotic susceptibility testing. Most (94%) were sensitive to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and 88% to levofloxacin. The next best choices were ceftazidime (72%) and meropenem (69%), although the authors pointed out that only 32 isolates were tested for that drug. Of the 60 tested for ticarcillin-clavulanate, 6% were sensitive.

The authors pointed out that the approximate 30% resistance rate to ceftazidime was concerning and unexpected.

Empiric therapy was considered inappropriate in 35%, and definitive therapy inappropriate in 11%. Having an infectious disease specialist involved with the case increased the chance that it would be treated appropriately (75% vs. 57%). Mortality was 16% at 14 days, 25% at 30 days, and 36% at 90 days. Older age, higher Charlson comorbidity index, higher Pitt bacteremia scores, and prior antibiotic treatment were independently associated with an increased risk of death, the researchers said.

Although the VA database comprises mostly of males, the review spanned so many years and comprised such a large cohort that the findings can probably be accurately extrapolated to a general population of patients, Dr. El Chakhtoura and associates added.

Dr. El Chakhtoura had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Non–cystic fibrosis–related Burkholderia cepacia complex infections occurred almost exclusively in older hospitalized patients with serious comorbidities – and the majority were acquired in a health care setting, a large U.S. Veterans Health Administration database study has determined.

Despite the bacteria’s tendency to be multidrug-resistant, both fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were equally effective, as long as they were promptly initiated, Nadim G. El Chakhtoura, MD, and colleagues reported (Clin Infect Dis, 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix559).

“We consider that the approach to improve survival in B. cepacia complex (Bcc) bloodstream infections … should include controlling the source of infection and prompt initiation of effective antibiotic therapy,” wrote Dr. El Chakhtoura of Cleveland Hospitals University Medical Center, and associates.

They found 248 cases of Bcc blood infections among such patients. Most (98%) were older men (mean age 68 years) with serious chronic and acute illnesses. Diabetes was common (44%), as was hemodialysis (23%). Many (41%) had been on mechanical ventilation. The etiology of the infections reflected these clinical factors: Most (62%) were nosocomial, with 41% associated with a central venous line and 20% with pneumonia. Just 9% were community acquired, mostly associated with pneumonia and intravenous drug use.

About 85% of isolates underwent antibiotic susceptibility testing. Most (94%) were sensitive to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and 88% to levofloxacin. The next best choices were ceftazidime (72%) and meropenem (69%), although the authors pointed out that only 32 isolates were tested for that drug. Of the 60 tested for ticarcillin-clavulanate, 6% were sensitive.

The authors pointed out that the approximate 30% resistance rate to ceftazidime was concerning and unexpected.