User login

Fighting in a passive manner active against Clostridium difficile

Infections resulting from Clostridium difficile are a major clinical challenge. In hematology and oncology, the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential for patients with profound neutropenia and infectious complications, which are a high-risk factor for C. difficile enteritis.

C. difficile enteritis occurs in 5%-20% of cancer patients.1 With standard of care antibiotics, oral metronidazole or oral vancomycin, high C. difficile cure rates are possible, but up to 25% of these infections recur. Recently, oral fidaxomicin was approved for treatment of C. difficile enteritis and was associated with high cure rates and, more importantly, with significantly lower recurrence rates.2

Bezlotoxumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against C. difficile toxin B, has been shown by x-ray crystallography to neutralize toxin B by blocking its ability to bind to host cells.7 Most recently, this new therapeutic approach was investigated in humans.8

Wilcox et al. used pooled data of 2655 adults treated in two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trials (MODIFY I and MODIFY II) for primary or recurrent C. difficile enteritis. This industry-sponsored trial was conducted at 322 sites in 30 countries.

In one treatment group, patients received a single infusion of bezlotoxumab (781 patients) or placebo (773 patients) and one of the three oral standard-of-care C. difficile antibiotics. Importantly, the primary end point of this trial was recurrent infection within 12 weeks. About 28% of the patients in both the bezlotoxumab group and the placebo group previously had at least one episode of C. difficile enteritis. About 20% of the patients in both groups were immunocompromised.

Pooled data showed that recurrent infection was significantly lower (P less than 0.001) in the bezlotoxumab group (17%), compared with the placebo group (27%). The difference in recurrence rate (25% vs. 41%) was even more pronounced in patients with one or more episodes of recurrent C. difficile enteritis in the past 6 months. Furthermore, a benefit for bezlotoxumab was seen in immunocompromised patients, whose recurrence rates were 15% with bezlotoxumab, vs. 28% with placebo. After the 12 weeks of follow-up, the absolute difference in the Kaplan-Meier rates of recurrent infection was 13% (absolute rate, 21% in bezlotoxumab group vs. 34% in placebo group; P less than 0.001).

The results indicate that bezlotoxumab, which was approved in 2016 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, might improve the outcome of patients with C. difficile enteritis. However, bezlotoxumab is not a “magic bullet.” The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of C. difficile enteritis is 10.

It is conceivable that bezlotoxumab may find its role in high-risk patients – those older than 65 years or patients with recurrent C. difficile enteritis – since the number needed to treat is only 6 in these subgroups.8

This new agent could be an important treatment option for our high-risk patients in hematology. However, more studies concerning costs and real-life efficacy are needed.

The new approach of passive immunization for prevention of recurrent C. difficile enteritis shows the importance and the role of toxin B – not only the bacterium per se – in pathogenesis and virulence of C. difficile. This could mean that we have to renew our view on the role of antibiotics against C. difficile. However, in contrast, bezlotoxumab does not affect the efficacy of standard of care antibiotics since the initial cure rates were 80% for both the antibody and the placebo groups.8 Toxin B levels are not detectable in stool samples between days 4 and 10 of standard of care antibiotic treatment. Afterward, however, they increase again.9 Most of the patients had received bezlotoxumab 3 or more days after they began standard-of-care antibiotic treatment – in the time period when toxin B is undetectable in stool – which underlines the importance of toxin B in the pathogenesis of recurrent C. difficile enteritis.8

In summary, the introduction of bezlotoxumab in clinical care gives new and important insights and solutions not only for treatment options but also for our understanding of C. difficile pathogenesis.

Dr. Schalk is consultant of internal medicine at the department of hematology and oncology, Magdeburg University Hospital, Germany, with clinical and research focus on infectious diseases in hematology and oncology.

Dr. Fischer is professor of internal medicine, hematology and oncology, at the Otto-von-Guericke University Hospital Magdeburg, Germany. He is head of the department of hematology and oncology and a clinical/molecular researcher in myeloid neoplasms. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Hematology News.

Contact Dr. Schalk at [email protected].

References

1. Vehreschild, MJ et al. Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal complications in adult cancer patients: Wvidence-based guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1189-202

2. Cornely, OA. Current and emerging management options for Clostridium difficile infection: What is the role of fidaxomicin? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 6):28-35.

3. Bartlett, JG et al. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin-producing clostridia. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(10):531-4.

4. Lyras, D et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176-9.

5. Reineke, J et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 2007;446:415-9.

6. Leav, BA et al. Serum anti-toxin B antibody correlates with protection from recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Vaccine. 2010;28:965-9.

7. Orth, P et al. Mechanism of action and epitopes of Clostridium difficile toxin B-neutralizing antibody bezlotoxumab revealed by X-ray crystallography. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:18008-21.

8. Wilcox, MH et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:305-17.

9. Louie, TJ et al. Fidaxomicin preserves the intestinal microbiome during and after treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and reduces both toxin reexpression and recurrence of CDI. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;5(Suppl 2):S132-42.

Infections resulting from Clostridium difficile are a major clinical challenge. In hematology and oncology, the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential for patients with profound neutropenia and infectious complications, which are a high-risk factor for C. difficile enteritis.

C. difficile enteritis occurs in 5%-20% of cancer patients.1 With standard of care antibiotics, oral metronidazole or oral vancomycin, high C. difficile cure rates are possible, but up to 25% of these infections recur. Recently, oral fidaxomicin was approved for treatment of C. difficile enteritis and was associated with high cure rates and, more importantly, with significantly lower recurrence rates.2

Bezlotoxumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against C. difficile toxin B, has been shown by x-ray crystallography to neutralize toxin B by blocking its ability to bind to host cells.7 Most recently, this new therapeutic approach was investigated in humans.8

Wilcox et al. used pooled data of 2655 adults treated in two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trials (MODIFY I and MODIFY II) for primary or recurrent C. difficile enteritis. This industry-sponsored trial was conducted at 322 sites in 30 countries.

In one treatment group, patients received a single infusion of bezlotoxumab (781 patients) or placebo (773 patients) and one of the three oral standard-of-care C. difficile antibiotics. Importantly, the primary end point of this trial was recurrent infection within 12 weeks. About 28% of the patients in both the bezlotoxumab group and the placebo group previously had at least one episode of C. difficile enteritis. About 20% of the patients in both groups were immunocompromised.

Pooled data showed that recurrent infection was significantly lower (P less than 0.001) in the bezlotoxumab group (17%), compared with the placebo group (27%). The difference in recurrence rate (25% vs. 41%) was even more pronounced in patients with one or more episodes of recurrent C. difficile enteritis in the past 6 months. Furthermore, a benefit for bezlotoxumab was seen in immunocompromised patients, whose recurrence rates were 15% with bezlotoxumab, vs. 28% with placebo. After the 12 weeks of follow-up, the absolute difference in the Kaplan-Meier rates of recurrent infection was 13% (absolute rate, 21% in bezlotoxumab group vs. 34% in placebo group; P less than 0.001).

The results indicate that bezlotoxumab, which was approved in 2016 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, might improve the outcome of patients with C. difficile enteritis. However, bezlotoxumab is not a “magic bullet.” The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of C. difficile enteritis is 10.

It is conceivable that bezlotoxumab may find its role in high-risk patients – those older than 65 years or patients with recurrent C. difficile enteritis – since the number needed to treat is only 6 in these subgroups.8

This new agent could be an important treatment option for our high-risk patients in hematology. However, more studies concerning costs and real-life efficacy are needed.

The new approach of passive immunization for prevention of recurrent C. difficile enteritis shows the importance and the role of toxin B – not only the bacterium per se – in pathogenesis and virulence of C. difficile. This could mean that we have to renew our view on the role of antibiotics against C. difficile. However, in contrast, bezlotoxumab does not affect the efficacy of standard of care antibiotics since the initial cure rates were 80% for both the antibody and the placebo groups.8 Toxin B levels are not detectable in stool samples between days 4 and 10 of standard of care antibiotic treatment. Afterward, however, they increase again.9 Most of the patients had received bezlotoxumab 3 or more days after they began standard-of-care antibiotic treatment – in the time period when toxin B is undetectable in stool – which underlines the importance of toxin B in the pathogenesis of recurrent C. difficile enteritis.8

In summary, the introduction of bezlotoxumab in clinical care gives new and important insights and solutions not only for treatment options but also for our understanding of C. difficile pathogenesis.

Dr. Schalk is consultant of internal medicine at the department of hematology and oncology, Magdeburg University Hospital, Germany, with clinical and research focus on infectious diseases in hematology and oncology.

Dr. Fischer is professor of internal medicine, hematology and oncology, at the Otto-von-Guericke University Hospital Magdeburg, Germany. He is head of the department of hematology and oncology and a clinical/molecular researcher in myeloid neoplasms. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Hematology News.

Contact Dr. Schalk at [email protected].

References

1. Vehreschild, MJ et al. Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal complications in adult cancer patients: Wvidence-based guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1189-202

2. Cornely, OA. Current and emerging management options for Clostridium difficile infection: What is the role of fidaxomicin? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 6):28-35.

3. Bartlett, JG et al. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin-producing clostridia. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(10):531-4.

4. Lyras, D et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176-9.

5. Reineke, J et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 2007;446:415-9.

6. Leav, BA et al. Serum anti-toxin B antibody correlates with protection from recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Vaccine. 2010;28:965-9.

7. Orth, P et al. Mechanism of action and epitopes of Clostridium difficile toxin B-neutralizing antibody bezlotoxumab revealed by X-ray crystallography. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:18008-21.

8. Wilcox, MH et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:305-17.

9. Louie, TJ et al. Fidaxomicin preserves the intestinal microbiome during and after treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and reduces both toxin reexpression and recurrence of CDI. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;5(Suppl 2):S132-42.

Infections resulting from Clostridium difficile are a major clinical challenge. In hematology and oncology, the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential for patients with profound neutropenia and infectious complications, which are a high-risk factor for C. difficile enteritis.

C. difficile enteritis occurs in 5%-20% of cancer patients.1 With standard of care antibiotics, oral metronidazole or oral vancomycin, high C. difficile cure rates are possible, but up to 25% of these infections recur. Recently, oral fidaxomicin was approved for treatment of C. difficile enteritis and was associated with high cure rates and, more importantly, with significantly lower recurrence rates.2

Bezlotoxumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against C. difficile toxin B, has been shown by x-ray crystallography to neutralize toxin B by blocking its ability to bind to host cells.7 Most recently, this new therapeutic approach was investigated in humans.8

Wilcox et al. used pooled data of 2655 adults treated in two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trials (MODIFY I and MODIFY II) for primary or recurrent C. difficile enteritis. This industry-sponsored trial was conducted at 322 sites in 30 countries.

In one treatment group, patients received a single infusion of bezlotoxumab (781 patients) or placebo (773 patients) and one of the three oral standard-of-care C. difficile antibiotics. Importantly, the primary end point of this trial was recurrent infection within 12 weeks. About 28% of the patients in both the bezlotoxumab group and the placebo group previously had at least one episode of C. difficile enteritis. About 20% of the patients in both groups were immunocompromised.

Pooled data showed that recurrent infection was significantly lower (P less than 0.001) in the bezlotoxumab group (17%), compared with the placebo group (27%). The difference in recurrence rate (25% vs. 41%) was even more pronounced in patients with one or more episodes of recurrent C. difficile enteritis in the past 6 months. Furthermore, a benefit for bezlotoxumab was seen in immunocompromised patients, whose recurrence rates were 15% with bezlotoxumab, vs. 28% with placebo. After the 12 weeks of follow-up, the absolute difference in the Kaplan-Meier rates of recurrent infection was 13% (absolute rate, 21% in bezlotoxumab group vs. 34% in placebo group; P less than 0.001).

The results indicate that bezlotoxumab, which was approved in 2016 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, might improve the outcome of patients with C. difficile enteritis. However, bezlotoxumab is not a “magic bullet.” The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of C. difficile enteritis is 10.

It is conceivable that bezlotoxumab may find its role in high-risk patients – those older than 65 years or patients with recurrent C. difficile enteritis – since the number needed to treat is only 6 in these subgroups.8

This new agent could be an important treatment option for our high-risk patients in hematology. However, more studies concerning costs and real-life efficacy are needed.

The new approach of passive immunization for prevention of recurrent C. difficile enteritis shows the importance and the role of toxin B – not only the bacterium per se – in pathogenesis and virulence of C. difficile. This could mean that we have to renew our view on the role of antibiotics against C. difficile. However, in contrast, bezlotoxumab does not affect the efficacy of standard of care antibiotics since the initial cure rates were 80% for both the antibody and the placebo groups.8 Toxin B levels are not detectable in stool samples between days 4 and 10 of standard of care antibiotic treatment. Afterward, however, they increase again.9 Most of the patients had received bezlotoxumab 3 or more days after they began standard-of-care antibiotic treatment – in the time period when toxin B is undetectable in stool – which underlines the importance of toxin B in the pathogenesis of recurrent C. difficile enteritis.8

In summary, the introduction of bezlotoxumab in clinical care gives new and important insights and solutions not only for treatment options but also for our understanding of C. difficile pathogenesis.

Dr. Schalk is consultant of internal medicine at the department of hematology and oncology, Magdeburg University Hospital, Germany, with clinical and research focus on infectious diseases in hematology and oncology.

Dr. Fischer is professor of internal medicine, hematology and oncology, at the Otto-von-Guericke University Hospital Magdeburg, Germany. He is head of the department of hematology and oncology and a clinical/molecular researcher in myeloid neoplasms. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Hematology News.

Contact Dr. Schalk at [email protected].

References

1. Vehreschild, MJ et al. Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal complications in adult cancer patients: Wvidence-based guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1189-202

2. Cornely, OA. Current and emerging management options for Clostridium difficile infection: What is the role of fidaxomicin? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 6):28-35.

3. Bartlett, JG et al. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin-producing clostridia. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(10):531-4.

4. Lyras, D et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176-9.

5. Reineke, J et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 2007;446:415-9.

6. Leav, BA et al. Serum anti-toxin B antibody correlates with protection from recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Vaccine. 2010;28:965-9.

7. Orth, P et al. Mechanism of action and epitopes of Clostridium difficile toxin B-neutralizing antibody bezlotoxumab revealed by X-ray crystallography. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:18008-21.

8. Wilcox, MH et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:305-17.

9. Louie, TJ et al. Fidaxomicin preserves the intestinal microbiome during and after treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and reduces both toxin reexpression and recurrence of CDI. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;5(Suppl 2):S132-42.

For vertebral osteomyelitis, early switch to oral antibiotics is feasible

VIENNA – A 6-week course of antibiotics, with an early switch from intravenous to oral, appears to be a safe and appropriate option for some patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis.

A single-center retrospective study of 82 such patients found two treatment failures and two deaths over 1 year (4.8% failure rate). The patients who died were very elderly with serious comorbidities. The two treatment failures occurred in patients with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections of a central catheter.

“Only two of the failures were due to inadequate antibiotic treatment,” Adrien Lemaignen, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. “Both patients experienced a relapse of bacteremia with the same bacteria a few days after antibiotic cessation in a context of conservative treatment of a catheter-related infection.”

Guidelines recently adopted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America inspired the study, said Dr. Lemaignen of University Hospital of Tours, France. The 2015 document calls for 6-8 weeks of antibiotics, depending upon the infective organism and whether infective endocarditis complicates management. All suggested antibiotic regimens call for initial IV therapy followed by oral, but there are no cut-and-dried recommendations about when to switch. The guideline notes one study in which patients switched to oral after about 2.7 weeks, with a 97% success rate.

Dr. Lemaignen and his colleagues set out to determine cure rates of early oral relay in 82 patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis (PVO). All patients were treated at a single center from 2011 to 2016. The team defined treatment failure as death, or persistence or relapse of infection in the first year after treatment.

All patients had culture-proven PVO that also was visible on imaging. Patients were excluded if they had any brucellar, fungal, or mycobacterial coinfections, or if they had infected spinal implants.

The mean age of the patients in the cohort was 66 years; 39% had some neuropathology. The mean C-reactive protein level was 115 mg/L. More than half of the cases (56%) involved the lumbar-sacral spine; 30% were thoracic, and the remainder, cervical. About one-fifth had multiple level involvement. There was epidural inflammation in 68%, epidural abscess in 13%, and extradural abscess in 26%.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (34%); two infections were methicillin resistant. Other infective organisms were streptococci (27%), Gram-negative bacilli (15%), and coagulase-negative staph (12%). A few patients had enterococci (5%) or polymicrobial infections (7%).

Infective endocarditis was present in 16 patients; this was associated with enterococcal and streptococcal infections.

Treatment varied by pathogen. Patients with S. aureus received penicillin or cefazolin with an oral relay to fluoroquinolone/rifampicin or clindamycin. Those with streptococci received amoxicillin with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by oral amoxicillin or clindamycin. Those with coagulase-negative streptococci received a glycopeptide with or without blasticidin, followed by fluoroquinolone/rifampicin. Patients with enterococcal infections got a third generation cephalosporin followed by an oral third generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

All but six patients received 6 weeks of treatment.

The mean oral relay occurred on day 12, but 30 patients (36%) were able to switch before 7 days elapsed. Thirteen patients had to stay on the IV route for their entire treatment; 25% of this group had infective endocarditis. Six patients, all of whom had motor symptoms, also needed surgery.

The median follow-up was 358 days. During this time, there were two deaths and two treatment failures.

One death was a 93-year-old who had a controlled sepsis, but died at day 79 of a massive hematemesis. The other was an 80-year-old with an amoxicillin-resistant staph infection and decompensated cirrhosis who died at day 49.

There were also two treatment failures. Both of these patients had methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staph infections of indwelling central catheters. One had a relapse 70 days after the end of IV therapy; the other relapsed on day 26 of treatment, after a 2-week course of oral antibiotics.

Not all patients were able to succeed with 6 weeks of therapy. Three needed prolonged treatment: One of these had an infected vascular prosthesis and two were immunocompromised patients who had cervical osteomyelitis with multiple abscesses.

In light of these results, Dr. Lemaignen said, “We can say confirm the safety of short IV treatment with an early oral relay in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under real-life conditions, with 95% success rate and good functional outcomes at 6 months.”

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – A 6-week course of antibiotics, with an early switch from intravenous to oral, appears to be a safe and appropriate option for some patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis.

A single-center retrospective study of 82 such patients found two treatment failures and two deaths over 1 year (4.8% failure rate). The patients who died were very elderly with serious comorbidities. The two treatment failures occurred in patients with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections of a central catheter.

“Only two of the failures were due to inadequate antibiotic treatment,” Adrien Lemaignen, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. “Both patients experienced a relapse of bacteremia with the same bacteria a few days after antibiotic cessation in a context of conservative treatment of a catheter-related infection.”

Guidelines recently adopted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America inspired the study, said Dr. Lemaignen of University Hospital of Tours, France. The 2015 document calls for 6-8 weeks of antibiotics, depending upon the infective organism and whether infective endocarditis complicates management. All suggested antibiotic regimens call for initial IV therapy followed by oral, but there are no cut-and-dried recommendations about when to switch. The guideline notes one study in which patients switched to oral after about 2.7 weeks, with a 97% success rate.

Dr. Lemaignen and his colleagues set out to determine cure rates of early oral relay in 82 patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis (PVO). All patients were treated at a single center from 2011 to 2016. The team defined treatment failure as death, or persistence or relapse of infection in the first year after treatment.

All patients had culture-proven PVO that also was visible on imaging. Patients were excluded if they had any brucellar, fungal, or mycobacterial coinfections, or if they had infected spinal implants.

The mean age of the patients in the cohort was 66 years; 39% had some neuropathology. The mean C-reactive protein level was 115 mg/L. More than half of the cases (56%) involved the lumbar-sacral spine; 30% were thoracic, and the remainder, cervical. About one-fifth had multiple level involvement. There was epidural inflammation in 68%, epidural abscess in 13%, and extradural abscess in 26%.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (34%); two infections were methicillin resistant. Other infective organisms were streptococci (27%), Gram-negative bacilli (15%), and coagulase-negative staph (12%). A few patients had enterococci (5%) or polymicrobial infections (7%).

Infective endocarditis was present in 16 patients; this was associated with enterococcal and streptococcal infections.

Treatment varied by pathogen. Patients with S. aureus received penicillin or cefazolin with an oral relay to fluoroquinolone/rifampicin or clindamycin. Those with streptococci received amoxicillin with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by oral amoxicillin or clindamycin. Those with coagulase-negative streptococci received a glycopeptide with or without blasticidin, followed by fluoroquinolone/rifampicin. Patients with enterococcal infections got a third generation cephalosporin followed by an oral third generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

All but six patients received 6 weeks of treatment.

The mean oral relay occurred on day 12, but 30 patients (36%) were able to switch before 7 days elapsed. Thirteen patients had to stay on the IV route for their entire treatment; 25% of this group had infective endocarditis. Six patients, all of whom had motor symptoms, also needed surgery.

The median follow-up was 358 days. During this time, there were two deaths and two treatment failures.

One death was a 93-year-old who had a controlled sepsis, but died at day 79 of a massive hematemesis. The other was an 80-year-old with an amoxicillin-resistant staph infection and decompensated cirrhosis who died at day 49.

There were also two treatment failures. Both of these patients had methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staph infections of indwelling central catheters. One had a relapse 70 days after the end of IV therapy; the other relapsed on day 26 of treatment, after a 2-week course of oral antibiotics.

Not all patients were able to succeed with 6 weeks of therapy. Three needed prolonged treatment: One of these had an infected vascular prosthesis and two were immunocompromised patients who had cervical osteomyelitis with multiple abscesses.

In light of these results, Dr. Lemaignen said, “We can say confirm the safety of short IV treatment with an early oral relay in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under real-life conditions, with 95% success rate and good functional outcomes at 6 months.”

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – A 6-week course of antibiotics, with an early switch from intravenous to oral, appears to be a safe and appropriate option for some patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis.

A single-center retrospective study of 82 such patients found two treatment failures and two deaths over 1 year (4.8% failure rate). The patients who died were very elderly with serious comorbidities. The two treatment failures occurred in patients with methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections of a central catheter.

“Only two of the failures were due to inadequate antibiotic treatment,” Adrien Lemaignen, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. “Both patients experienced a relapse of bacteremia with the same bacteria a few days after antibiotic cessation in a context of conservative treatment of a catheter-related infection.”

Guidelines recently adopted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America inspired the study, said Dr. Lemaignen of University Hospital of Tours, France. The 2015 document calls for 6-8 weeks of antibiotics, depending upon the infective organism and whether infective endocarditis complicates management. All suggested antibiotic regimens call for initial IV therapy followed by oral, but there are no cut-and-dried recommendations about when to switch. The guideline notes one study in which patients switched to oral after about 2.7 weeks, with a 97% success rate.

Dr. Lemaignen and his colleagues set out to determine cure rates of early oral relay in 82 patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis (PVO). All patients were treated at a single center from 2011 to 2016. The team defined treatment failure as death, or persistence or relapse of infection in the first year after treatment.

All patients had culture-proven PVO that also was visible on imaging. Patients were excluded if they had any brucellar, fungal, or mycobacterial coinfections, or if they had infected spinal implants.

The mean age of the patients in the cohort was 66 years; 39% had some neuropathology. The mean C-reactive protein level was 115 mg/L. More than half of the cases (56%) involved the lumbar-sacral spine; 30% were thoracic, and the remainder, cervical. About one-fifth had multiple level involvement. There was epidural inflammation in 68%, epidural abscess in 13%, and extradural abscess in 26%.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (34%); two infections were methicillin resistant. Other infective organisms were streptococci (27%), Gram-negative bacilli (15%), and coagulase-negative staph (12%). A few patients had enterococci (5%) or polymicrobial infections (7%).

Infective endocarditis was present in 16 patients; this was associated with enterococcal and streptococcal infections.

Treatment varied by pathogen. Patients with S. aureus received penicillin or cefazolin with an oral relay to fluoroquinolone/rifampicin or clindamycin. Those with streptococci received amoxicillin with or without an aminoglycoside, followed by oral amoxicillin or clindamycin. Those with coagulase-negative streptococci received a glycopeptide with or without blasticidin, followed by fluoroquinolone/rifampicin. Patients with enterococcal infections got a third generation cephalosporin followed by an oral third generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

All but six patients received 6 weeks of treatment.

The mean oral relay occurred on day 12, but 30 patients (36%) were able to switch before 7 days elapsed. Thirteen patients had to stay on the IV route for their entire treatment; 25% of this group had infective endocarditis. Six patients, all of whom had motor symptoms, also needed surgery.

The median follow-up was 358 days. During this time, there were two deaths and two treatment failures.

One death was a 93-year-old who had a controlled sepsis, but died at day 79 of a massive hematemesis. The other was an 80-year-old with an amoxicillin-resistant staph infection and decompensated cirrhosis who died at day 49.

There were also two treatment failures. Both of these patients had methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staph infections of indwelling central catheters. One had a relapse 70 days after the end of IV therapy; the other relapsed on day 26 of treatment, after a 2-week course of oral antibiotics.

Not all patients were able to succeed with 6 weeks of therapy. Three needed prolonged treatment: One of these had an infected vascular prosthesis and two were immunocompromised patients who had cervical osteomyelitis with multiple abscesses.

In light of these results, Dr. Lemaignen said, “We can say confirm the safety of short IV treatment with an early oral relay in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under real-life conditions, with 95% success rate and good functional outcomes at 6 months.”

He had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT ECCMID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There were two treatment failures attributable to the antibiotic regimen, and two deaths that were not, for a total treatment success rate of 95%.

Data source: A retrospective cohort comprising 82 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Lemaignen had no financial disclosures.

Ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections by protecting microbiome

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT ECCMID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Ribaxamase reduced C. difficile infections by 71%, relative to a placebo.

Data source: The study randomized 412 patients to either placebo or ribaxamase in addition to their therapeutic antibiotics.

Disclosures: Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

VIDEO: Registry study will follow 4,000 fecal transplant patients for 10 years

CHICAGO – A 10-year registry study aims to gather clinical and patient-reported outcomes on 4,000 adult and pediatric patients who undergo fecal microbiota transplant in the United States, officials of the American Gastroenterological Association announced during Digestive Disease Week®.

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry will be the first study to assess both short- and long-term patient outcomes associated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in both adults and children, Colleen Kelly, MD, said in an video interview. Most subjects will have received FMT for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infections – the only indication for which Food and Drug Administration currently allows independent clinician action. But the investigational uses of FMT are expanding rapidly, and patients who undergo the procedure during any registered study will be eligible for enrollment, said Dr. Kelly, co-chair of the study’s steering committee.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study’s primary objectives are short- and long-term safety outcomes, said Dr. Kelly of Brown University, Providence, R.I. While generally considered quite safe, short-term adverse events have been reported with FMT, and some of them have been serious – including one death from aspiration pneumonia in a patient who received donor stool via nasogastric tube (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;61[1]:136-7). Other adverse events are usually self-limited but can include low-grade fever, abdominal pain, distention, bloating, and diarrhea.

Researchers seek to illuminate many of the unknowns associated with this relatively new procedure. Scientists are only now beginning to unravel the myriad ways the human microbiome promotes both health and disease. Specific alterations, for example, have been associated with obesity and other conditions; there is concern that transplanting a new microbial population could induce a disease phenotype in a recipient who might not have otherwise been at risk.

With the planned cohort size and follow-up period, the study should be able to detect any unanticipated adverse events that occur in more than 1% of the population, Dr. Kelly said. It will include a comparator group of patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection from a large insurance claims database to allow comparison between patients treated with FMT and those treated with antibiotics only.

The registry study also aims to discover which method or methods of transplant material delivery are best, she said. Right now, there are a number of methods (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, enema, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube, and capsules), and no consensus on which is the best. As indications for FMT expand, there may be no single best method. The approach will probably be matched to the disorder being treated, and the study may help illuminate this as well.

For the first 2 years after a transplant, clinicians will follow patients and enter data into the registry. After that, an electronic patient-reported outcomes system will automatically contact the patient annually for follow-up information by email or text message. When patients enter their data, they can access educational material that will help keep them up-to-date on potential adverse events.

The study will also include a biobank of stool samples obtained during the procedures, hosted by the American Gut Project and the Microbiome Initiative at the University of California, San Diego. This arm of the project will analyze the microbiome of 3,000 stool samples from recipients, both before and after their transplant, as well as the corresponding donors whose material was used in the fecal transplant.

The registry study, a project of the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education, is funded by a $3.3 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It will be conducted in partnership with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Infectious Diseases Society, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

The registry study currently is accepting applications. Physicians who perform FMT for C. difficile infections, and centers that conduct FMT research for other potential indications, can fill out a short survey to indicate their interest.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

This article was updated June 8, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

CHICAGO – A 10-year registry study aims to gather clinical and patient-reported outcomes on 4,000 adult and pediatric patients who undergo fecal microbiota transplant in the United States, officials of the American Gastroenterological Association announced during Digestive Disease Week®.

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry will be the first study to assess both short- and long-term patient outcomes associated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in both adults and children, Colleen Kelly, MD, said in an video interview. Most subjects will have received FMT for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infections – the only indication for which Food and Drug Administration currently allows independent clinician action. But the investigational uses of FMT are expanding rapidly, and patients who undergo the procedure during any registered study will be eligible for enrollment, said Dr. Kelly, co-chair of the study’s steering committee.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study’s primary objectives are short- and long-term safety outcomes, said Dr. Kelly of Brown University, Providence, R.I. While generally considered quite safe, short-term adverse events have been reported with FMT, and some of them have been serious – including one death from aspiration pneumonia in a patient who received donor stool via nasogastric tube (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;61[1]:136-7). Other adverse events are usually self-limited but can include low-grade fever, abdominal pain, distention, bloating, and diarrhea.

Researchers seek to illuminate many of the unknowns associated with this relatively new procedure. Scientists are only now beginning to unravel the myriad ways the human microbiome promotes both health and disease. Specific alterations, for example, have been associated with obesity and other conditions; there is concern that transplanting a new microbial population could induce a disease phenotype in a recipient who might not have otherwise been at risk.

With the planned cohort size and follow-up period, the study should be able to detect any unanticipated adverse events that occur in more than 1% of the population, Dr. Kelly said. It will include a comparator group of patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection from a large insurance claims database to allow comparison between patients treated with FMT and those treated with antibiotics only.

The registry study also aims to discover which method or methods of transplant material delivery are best, she said. Right now, there are a number of methods (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, enema, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube, and capsules), and no consensus on which is the best. As indications for FMT expand, there may be no single best method. The approach will probably be matched to the disorder being treated, and the study may help illuminate this as well.

For the first 2 years after a transplant, clinicians will follow patients and enter data into the registry. After that, an electronic patient-reported outcomes system will automatically contact the patient annually for follow-up information by email or text message. When patients enter their data, they can access educational material that will help keep them up-to-date on potential adverse events.

The study will also include a biobank of stool samples obtained during the procedures, hosted by the American Gut Project and the Microbiome Initiative at the University of California, San Diego. This arm of the project will analyze the microbiome of 3,000 stool samples from recipients, both before and after their transplant, as well as the corresponding donors whose material was used in the fecal transplant.

The registry study, a project of the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education, is funded by a $3.3 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It will be conducted in partnership with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Infectious Diseases Society, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

The registry study currently is accepting applications. Physicians who perform FMT for C. difficile infections, and centers that conduct FMT research for other potential indications, can fill out a short survey to indicate their interest.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

This article was updated June 8, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

CHICAGO – A 10-year registry study aims to gather clinical and patient-reported outcomes on 4,000 adult and pediatric patients who undergo fecal microbiota transplant in the United States, officials of the American Gastroenterological Association announced during Digestive Disease Week®.

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry will be the first study to assess both short- and long-term patient outcomes associated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in both adults and children, Colleen Kelly, MD, said in an video interview. Most subjects will have received FMT for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infections – the only indication for which Food and Drug Administration currently allows independent clinician action. But the investigational uses of FMT are expanding rapidly, and patients who undergo the procedure during any registered study will be eligible for enrollment, said Dr. Kelly, co-chair of the study’s steering committee.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study’s primary objectives are short- and long-term safety outcomes, said Dr. Kelly of Brown University, Providence, R.I. While generally considered quite safe, short-term adverse events have been reported with FMT, and some of them have been serious – including one death from aspiration pneumonia in a patient who received donor stool via nasogastric tube (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;61[1]:136-7). Other adverse events are usually self-limited but can include low-grade fever, abdominal pain, distention, bloating, and diarrhea.

Researchers seek to illuminate many of the unknowns associated with this relatively new procedure. Scientists are only now beginning to unravel the myriad ways the human microbiome promotes both health and disease. Specific alterations, for example, have been associated with obesity and other conditions; there is concern that transplanting a new microbial population could induce a disease phenotype in a recipient who might not have otherwise been at risk.

With the planned cohort size and follow-up period, the study should be able to detect any unanticipated adverse events that occur in more than 1% of the population, Dr. Kelly said. It will include a comparator group of patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection from a large insurance claims database to allow comparison between patients treated with FMT and those treated with antibiotics only.

The registry study also aims to discover which method or methods of transplant material delivery are best, she said. Right now, there are a number of methods (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, enema, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube, and capsules), and no consensus on which is the best. As indications for FMT expand, there may be no single best method. The approach will probably be matched to the disorder being treated, and the study may help illuminate this as well.

For the first 2 years after a transplant, clinicians will follow patients and enter data into the registry. After that, an electronic patient-reported outcomes system will automatically contact the patient annually for follow-up information by email or text message. When patients enter their data, they can access educational material that will help keep them up-to-date on potential adverse events.

The study will also include a biobank of stool samples obtained during the procedures, hosted by the American Gut Project and the Microbiome Initiative at the University of California, San Diego. This arm of the project will analyze the microbiome of 3,000 stool samples from recipients, both before and after their transplant, as well as the corresponding donors whose material was used in the fecal transplant.

The registry study, a project of the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education, is funded by a $3.3 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It will be conducted in partnership with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Infectious Diseases Society, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

The registry study currently is accepting applications. Physicians who perform FMT for C. difficile infections, and centers that conduct FMT research for other potential indications, can fill out a short survey to indicate their interest.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

This article was updated June 8, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT DDW

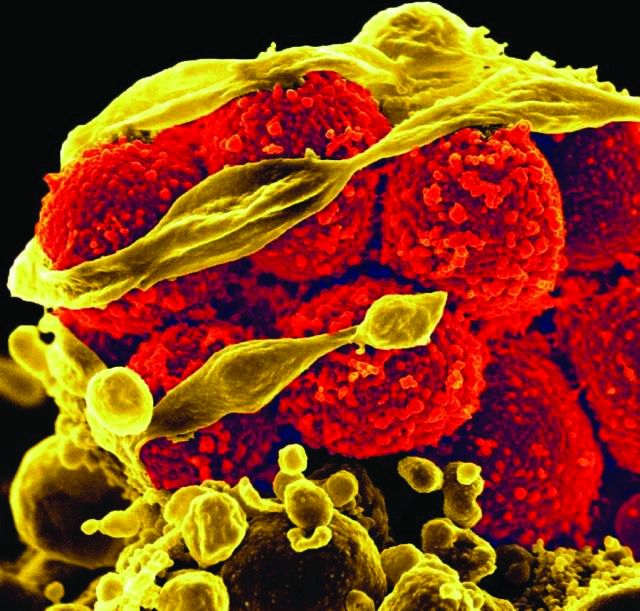

Each added day of pediatric MRSA bacteremia upped complication risk 50%

Every additional day of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia in hospitalized children was associated with a 50% increased risk of developing a complication, reported Rana F. Hamdy, MD, of Children’s National Health System, Washington, and her associates.

That was one of the findings of a study performed to determine the epidemiology, clinical outcomes, and risk factors for treatment failure in pediatric MRSA bacteremia. It took place in three hospitals, one each in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Salt Lake City.

“This finding is in contrast to the epidemiology of MRSA bacteremia in adults, in whom bacteremia is more frequently attributed to catheter-related infections (31%-36%), endovascular infections (13%-15%), or an unknown source (15%-20%), and the durations of MRSA bacteremia are typically more prolonged (median duration of bacteremia is 8-9 days),” Dr. Hamdy and her associates wrote.

“Differences in the epidemiology of MRSA bacteremia between children and adults emphasize the need for dedicated pediatric studies to better understand the clinical characteristics and outcomes specific to children,” the researchers noted.

Musculoskeletal infections and endovascular infections were linked with treatment failure, possibly reflecting “the relatively higher burden of bacteria and/or decreased drug penetration into bone and endovascular infection sites,” the investigators said. Catheter-related infections were tied to reduced odds of treatment failure, “these episodes being localized to the catheter and therefore potentially less-invasive S. aureus infections.”

Mortality among these children with MRSA bacteremia was low, at 2%, but “nearly one-quarter of all patients experienced complications,” the study authors said (Pediatrics. 2017 May 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0183).

There was progression of infection in 7% of cases, and hematogenous complications or sequelae occurred in 23%. Twenty percent of children developed septic emboli or another metastatic focus of infection.

“This association between the duration of bacteremia and the development of complications has been previously reported among adults with S. aureus bacteremia,” Dr. Hamdy noted, “and provides important epidemiologic data that could inform decisions relating to the timing of additional imaging, such as echocardiograms, to identify metastatic foci.”

The children were treated with vancomycin, and some received additional anti-MRSA antibiotics. “Vancomycin trough concentrations or [minimum inhibitory concentrations] were not associated with treatment failure,” the investigators said. “Future studies to determine the appropriate vancomycin dose, duration, and approach to therapeutic drug monitoring are warranted to optimize patient outcomes.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Hamdy and her associates disclosed they have no relevant financial relationships.

Every additional day of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia in hospitalized children was associated with a 50% increased risk of developing a complication, reported Rana F. Hamdy, MD, of Children’s National Health System, Washington, and her associates.

That was one of the findings of a study performed to determine the epidemiology, clinical outcomes, and risk factors for treatment failure in pediatric MRSA bacteremia. It took place in three hospitals, one each in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Salt Lake City.

“This finding is in contrast to the epidemiology of MRSA bacteremia in adults, in whom bacteremia is more frequently attributed to catheter-related infections (31%-36%), endovascular infections (13%-15%), or an unknown source (15%-20%), and the durations of MRSA bacteremia are typically more prolonged (median duration of bacteremia is 8-9 days),” Dr. Hamdy and her associates wrote.

“Differences in the epidemiology of MRSA bacteremia between children and adults emphasize the need for dedicated pediatric studies to better understand the clinical characteristics and outcomes specific to children,” the researchers noted.

Musculoskeletal infections and endovascular infections were linked with treatment failure, possibly reflecting “the relatively higher burden of bacteria and/or decreased drug penetration into bone and endovascular infection sites,” the investigators said. Catheter-related infections were tied to reduced odds of treatment failure, “these episodes being localized to the catheter and therefore potentially less-invasive S. aureus infections.”

Mortality among these children with MRSA bacteremia was low, at 2%, but “nearly one-quarter of all patients experienced complications,” the study authors said (Pediatrics. 2017 May 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0183).

There was progression of infection in 7% of cases, and hematogenous complications or sequelae occurred in 23%. Twenty percent of children developed septic emboli or another metastatic focus of infection.

“This association between the duration of bacteremia and the development of complications has been previously reported among adults with S. aureus bacteremia,” Dr. Hamdy noted, “and provides important epidemiologic data that could inform decisions relating to the timing of additional imaging, such as echocardiograms, to identify metastatic foci.”

The children were treated with vancomycin, and some received additional anti-MRSA antibiotics. “Vancomycin trough concentrations or [minimum inhibitory concentrations] were not associated with treatment failure,” the investigators said. “Future studies to determine the appropriate vancomycin dose, duration, and approach to therapeutic drug monitoring are warranted to optimize patient outcomes.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Hamdy and her associates disclosed they have no relevant financial relationships.

Every additional day of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia in hospitalized children was associated with a 50% increased risk of developing a complication, reported Rana F. Hamdy, MD, of Children’s National Health System, Washington, and her associates.

That was one of the findings of a study performed to determine the epidemiology, clinical outcomes, and risk factors for treatment failure in pediatric MRSA bacteremia. It took place in three hospitals, one each in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Salt Lake City.

“This finding is in contrast to the epidemiology of MRSA bacteremia in adults, in whom bacteremia is more frequently attributed to catheter-related infections (31%-36%), endovascular infections (13%-15%), or an unknown source (15%-20%), and the durations of MRSA bacteremia are typically more prolonged (median duration of bacteremia is 8-9 days),” Dr. Hamdy and her associates wrote.

“Differences in the epidemiology of MRSA bacteremia between children and adults emphasize the need for dedicated pediatric studies to better understand the clinical characteristics and outcomes specific to children,” the researchers noted.

Musculoskeletal infections and endovascular infections were linked with treatment failure, possibly reflecting “the relatively higher burden of bacteria and/or decreased drug penetration into bone and endovascular infection sites,” the investigators said. Catheter-related infections were tied to reduced odds of treatment failure, “these episodes being localized to the catheter and therefore potentially less-invasive S. aureus infections.”

Mortality among these children with MRSA bacteremia was low, at 2%, but “nearly one-quarter of all patients experienced complications,” the study authors said (Pediatrics. 2017 May 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0183).

There was progression of infection in 7% of cases, and hematogenous complications or sequelae occurred in 23%. Twenty percent of children developed septic emboli or another metastatic focus of infection.

“This association between the duration of bacteremia and the development of complications has been previously reported among adults with S. aureus bacteremia,” Dr. Hamdy noted, “and provides important epidemiologic data that could inform decisions relating to the timing of additional imaging, such as echocardiograms, to identify metastatic foci.”

The children were treated with vancomycin, and some received additional anti-MRSA antibiotics. “Vancomycin trough concentrations or [minimum inhibitory concentrations] were not associated with treatment failure,” the investigators said. “Future studies to determine the appropriate vancomycin dose, duration, and approach to therapeutic drug monitoring are warranted to optimize patient outcomes.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Hamdy and her associates disclosed they have no relevant financial relationships.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The primary sources of infection were osteomyelitis (31%), catheter-related bloodstream infections (22%), and skin and soft tissue infections (16%); endocarditis occurred in only 2% – a different epidemiology than in adults.

Data source: A study of 174 hospitalized children (younger than 19 years) with MRSA bacteremia at three hospitals in different states.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Hamdy and her associates disclosed they have no relevant financial relationships.

Hospital infections top WHO’s list of priority pathogens

The World Health Organization is urging governments to focus antibiotic research efforts on a list of urgent bacterial threats, topped by several increasingly powerful superbugs that cause hospital-based infections and other potentially deadly conditions.

The WHO listed the top 20 bacteria that it believes are most harmful to human health, other than mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis. The germ was not included in the list because it’s generally accepted to be the most urgent priority for new antibiotic research and development, Marie-Paule Kieny, PhD, a WHO assistant director, said at a press conference.

The priority list is needed because the antibiotic pipeline is “practically dry,” thanks to scientific research challenges and a lack of financial incentives, according to Dr. Kieny. “Antibiotics are generally used for the short term, unlike therapies for chronic diseases, which bring in much higher returns on investment,” she said. The list “is intended to signal to the scientific community and the pharmaceutical industry the areas they should focus on to address urgent public health threats.”

The WHO list begins with Priority 1/“Critical” pathogens that it believes most urgently need to be targeted through antibiotic research and development: Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant; and Enterobacteriaceae (including Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Proteus spp., Providencia spp., and Morganella spp.), carbapenem-resistant, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing.

“These bacteria are responsible for severe infections and high mortality rates, mostly in hospitalized patients, transplant recipients, those receiving chemotherapy, or patients in intensive care units,” Dr. Kieny said. “While these bacteria are not widespread and do not generally affect healthy individuals, the burden for patients and society is now alarming – and new, effective therapies are imperative.”

Priority 2/”High” pathogens are Enterococcus faecium, vancomycin-resistant; Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin intermediate and resistant; Helicobacter pylori, clarithromycin-resistant; Campylobacter, fluoroquinolone-resistant; Salmonella spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant; Neisseria gonorrhoeae, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant and fluoroquinolone-resistant.

Pathogens in this category can infect healthy individuals, Dr. Kieny noted. “These infections, although not associated with significant mortality, have a dramatic health and economic impact on communities and, in particular, in low-income countries.”

Priority 3/”Medium” pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin–non-susceptible; Haemophilus influenzae, ampicillin-resistant; and Shigella spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant.

These pathogens “represent a threat because of increasing resistance but still have some effective antibiotic options available,” Dr. Kieny said.

According to a statement provided by the WHO, the priority list doesn’t include streptococcus A and B or chlamydia, because resistance hasn’t reached the level of a public health threat.

One goal of the list is to focus attention on the development of small-market, gram-negative drugs that combat hospital-based infections, explained Nicola Magrini, MD, a WHO scientist who also spoke at the press conference.

Over the last decade, he said, the pipeline has instead focused more on gram-positive agents – mostly linked to beta-lactamase – that have wider market potential and generate less resistance.

“From a clinical point of view, these multidrug-resistant gram-negative clinical trials are very difficult and expensive to do, more than for gram-positive,” noted Evelina Tacconelli, MD, PhD, a contributor to the WHO report. “Because when we talk about gram-negative, we need to cover multiple pathogens and not just one or two, as in the case of gram-positive.”

Dr. Magrini said he couldn’t provide estimates about how many people worldwide are affected by the listed pathogens. However, he said a full report with numbers will be released by June.

It does appear that patients with severe infection from antibiotic-resistant germs face a mortality rate of up to 60%, while extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–positive E. coli accounts for up to 70% of urinary tract infections in many countries, explained Dr. Tacconelli, head of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Tübingen, Germany.

“Even if we don’t know exactly how many,” she said, “we are talking about millions of people affected.”

The World Health Organization is urging governments to focus antibiotic research efforts on a list of urgent bacterial threats, topped by several increasingly powerful superbugs that cause hospital-based infections and other potentially deadly conditions.

The WHO listed the top 20 bacteria that it believes are most harmful to human health, other than mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis. The germ was not included in the list because it’s generally accepted to be the most urgent priority for new antibiotic research and development, Marie-Paule Kieny, PhD, a WHO assistant director, said at a press conference.

The priority list is needed because the antibiotic pipeline is “practically dry,” thanks to scientific research challenges and a lack of financial incentives, according to Dr. Kieny. “Antibiotics are generally used for the short term, unlike therapies for chronic diseases, which bring in much higher returns on investment,” she said. The list “is intended to signal to the scientific community and the pharmaceutical industry the areas they should focus on to address urgent public health threats.”

The WHO list begins with Priority 1/“Critical” pathogens that it believes most urgently need to be targeted through antibiotic research and development: Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant; and Enterobacteriaceae (including Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Proteus spp., Providencia spp., and Morganella spp.), carbapenem-resistant, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing.

“These bacteria are responsible for severe infections and high mortality rates, mostly in hospitalized patients, transplant recipients, those receiving chemotherapy, or patients in intensive care units,” Dr. Kieny said. “While these bacteria are not widespread and do not generally affect healthy individuals, the burden for patients and society is now alarming – and new, effective therapies are imperative.”

Priority 2/”High” pathogens are Enterococcus faecium, vancomycin-resistant; Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin intermediate and resistant; Helicobacter pylori, clarithromycin-resistant; Campylobacter, fluoroquinolone-resistant; Salmonella spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant; Neisseria gonorrhoeae, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant and fluoroquinolone-resistant.

Pathogens in this category can infect healthy individuals, Dr. Kieny noted. “These infections, although not associated with significant mortality, have a dramatic health and economic impact on communities and, in particular, in low-income countries.”

Priority 3/”Medium” pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin–non-susceptible; Haemophilus influenzae, ampicillin-resistant; and Shigella spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant.

These pathogens “represent a threat because of increasing resistance but still have some effective antibiotic options available,” Dr. Kieny said.

According to a statement provided by the WHO, the priority list doesn’t include streptococcus A and B or chlamydia, because resistance hasn’t reached the level of a public health threat.

One goal of the list is to focus attention on the development of small-market, gram-negative drugs that combat hospital-based infections, explained Nicola Magrini, MD, a WHO scientist who also spoke at the press conference.

Over the last decade, he said, the pipeline has instead focused more on gram-positive agents – mostly linked to beta-lactamase – that have wider market potential and generate less resistance.

“From a clinical point of view, these multidrug-resistant gram-negative clinical trials are very difficult and expensive to do, more than for gram-positive,” noted Evelina Tacconelli, MD, PhD, a contributor to the WHO report. “Because when we talk about gram-negative, we need to cover multiple pathogens and not just one or two, as in the case of gram-positive.”

Dr. Magrini said he couldn’t provide estimates about how many people worldwide are affected by the listed pathogens. However, he said a full report with numbers will be released by June.

It does appear that patients with severe infection from antibiotic-resistant germs face a mortality rate of up to 60%, while extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–positive E. coli accounts for up to 70% of urinary tract infections in many countries, explained Dr. Tacconelli, head of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Tübingen, Germany.

“Even if we don’t know exactly how many,” she said, “we are talking about millions of people affected.”

The World Health Organization is urging governments to focus antibiotic research efforts on a list of urgent bacterial threats, topped by several increasingly powerful superbugs that cause hospital-based infections and other potentially deadly conditions.

The WHO listed the top 20 bacteria that it believes are most harmful to human health, other than mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis. The germ was not included in the list because it’s generally accepted to be the most urgent priority for new antibiotic research and development, Marie-Paule Kieny, PhD, a WHO assistant director, said at a press conference.