User login

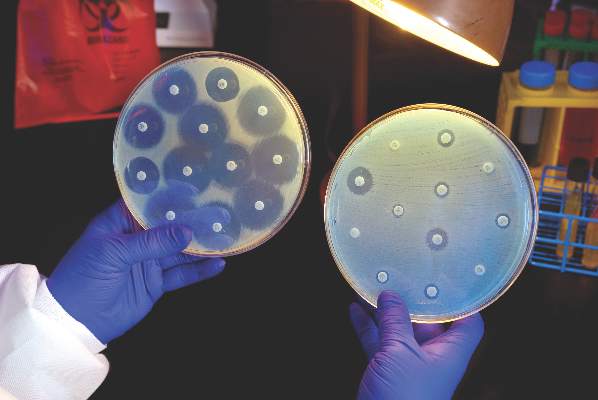

Antibiotic stewardship lacking at many hospital nurseries

Nearly one-third of hospital newborn nurseries and neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program, according to a survey of 146 hospital nursery centers across all 50 states.

Researchers randomly selected a level III NICU in each state using the 2014 American Hospital Association annual survey, then selected a level I and level II nursery in the same city. They collected data on the hospital, nursery, and antibiotic stewardship program characteristics and interviewed staff pharmacists and infectious diseases physicians (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jul 15. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw040).

A total of 104 (71%) of responding hospitals had an antibiotic stewardship program in place for their nurseries. Hospitals with a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship programs tended to be larger, have more full-time equivalent staff dedicated to the antibiotic stewardship program, have higher level nurses, and be affiliated with a university, according to Joseph B. Cantey, MD, and his colleagues from the Texas A&M Health Science Center in Temple.

Geographic region and core stewardship strategies did not influence the likelihood of a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship program in place.

From the interviews, the researchers identified several barriers to implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs, and themes such as unwanted coverage, unnecessary coverage, and need for communication.

“Many [antibiotic stewardship program] and nursery representatives stated that nursery [antibiotic stewardship program] coverage was not important, either because antibiotic consumption was perceived as low (theme 1), narrow-spectrum (theme 2), or both,” the authors wrote.

Some nursery providers also argued that participating in stewardship programs was time consuming and not valuable, which the authors said was often related to a lack of pediatric expertise in the program providers. Some of those interviewed also spoke of issues relating to jurisdiction and responsibility for the programs, and there was also a common perception that antibiotic stewardship programs were more concerned with cost savings than patient care.

“Barriers to effective nursery stewardship are exacerbated by lack of communication between stewardship providers and their nursery counterparts,” the authors reported.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nearly one-third of hospital newborn nurseries and neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program, according to a survey of 146 hospital nursery centers across all 50 states.

Researchers randomly selected a level III NICU in each state using the 2014 American Hospital Association annual survey, then selected a level I and level II nursery in the same city. They collected data on the hospital, nursery, and antibiotic stewardship program characteristics and interviewed staff pharmacists and infectious diseases physicians (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jul 15. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw040).

A total of 104 (71%) of responding hospitals had an antibiotic stewardship program in place for their nurseries. Hospitals with a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship programs tended to be larger, have more full-time equivalent staff dedicated to the antibiotic stewardship program, have higher level nurses, and be affiliated with a university, according to Joseph B. Cantey, MD, and his colleagues from the Texas A&M Health Science Center in Temple.

Geographic region and core stewardship strategies did not influence the likelihood of a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship program in place.

From the interviews, the researchers identified several barriers to implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs, and themes such as unwanted coverage, unnecessary coverage, and need for communication.

“Many [antibiotic stewardship program] and nursery representatives stated that nursery [antibiotic stewardship program] coverage was not important, either because antibiotic consumption was perceived as low (theme 1), narrow-spectrum (theme 2), or both,” the authors wrote.

Some nursery providers also argued that participating in stewardship programs was time consuming and not valuable, which the authors said was often related to a lack of pediatric expertise in the program providers. Some of those interviewed also spoke of issues relating to jurisdiction and responsibility for the programs, and there was also a common perception that antibiotic stewardship programs were more concerned with cost savings than patient care.

“Barriers to effective nursery stewardship are exacerbated by lack of communication between stewardship providers and their nursery counterparts,” the authors reported.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nearly one-third of hospital newborn nurseries and neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program, according to a survey of 146 hospital nursery centers across all 50 states.

Researchers randomly selected a level III NICU in each state using the 2014 American Hospital Association annual survey, then selected a level I and level II nursery in the same city. They collected data on the hospital, nursery, and antibiotic stewardship program characteristics and interviewed staff pharmacists and infectious diseases physicians (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jul 15. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw040).

A total of 104 (71%) of responding hospitals had an antibiotic stewardship program in place for their nurseries. Hospitals with a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship programs tended to be larger, have more full-time equivalent staff dedicated to the antibiotic stewardship program, have higher level nurses, and be affiliated with a university, according to Joseph B. Cantey, MD, and his colleagues from the Texas A&M Health Science Center in Temple.

Geographic region and core stewardship strategies did not influence the likelihood of a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship program in place.

From the interviews, the researchers identified several barriers to implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs, and themes such as unwanted coverage, unnecessary coverage, and need for communication.

“Many [antibiotic stewardship program] and nursery representatives stated that nursery [antibiotic stewardship program] coverage was not important, either because antibiotic consumption was perceived as low (theme 1), narrow-spectrum (theme 2), or both,” the authors wrote.

Some nursery providers also argued that participating in stewardship programs was time consuming and not valuable, which the authors said was often related to a lack of pediatric expertise in the program providers. Some of those interviewed also spoke of issues relating to jurisdiction and responsibility for the programs, and there was also a common perception that antibiotic stewardship programs were more concerned with cost savings than patient care.

“Barriers to effective nursery stewardship are exacerbated by lack of communication between stewardship providers and their nursery counterparts,” the authors reported.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Key clinical point: Many hospital newborn nurseries or neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program in place.

Major finding: 29% of hospital nurseries surveyed did not have an antibiotic stewardship program.

Data source: Survey of 146 hospital nursery centers in 50 states.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

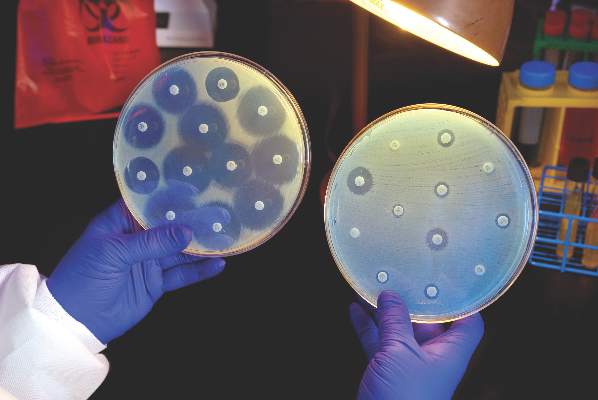

Hospitals increase CRE risk when they share patients

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with CRE, especially if long-term acute care hospitals are in the mix.

Major finding: Sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases (P = 0.11).

Data source: 185 Illinois hospitals.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

Antibiotics overprescribed during asthma-related hospitalizations

Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations, even though guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics during exacerbations of asthma in the absence of concurrent infection, reported Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, of Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and his colleagues.

They examined the hospitalization records of 51,951 individuals admitted to 577 hospitals in the United States between 2013 and 2014 with a principal diagnosis of either asthma or acute respiratory failure combined with asthma as a secondary diagnosis. Each patient type and the timing of antibiotic therapy was noted.

A total of 30,226 of the 51,951 patients (58.2%) were prescribed antibiotics at some point during their hospitalization, while 21,248 (40.9%) were prescribed antibiotics on the first day of hospitalization, without “documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.”

Macrolides were most commonly prescribed, given to 9,633 (18.5%) of patients, followed by quinolones (8,632, 16.1%), third-generation cephalosporins (4,420, 8.5%), and tetracyclines (1,858, 3.6%). After adjustment for risk variables, chronic obstructive asthma hospitalizations were found to be those most highly associated with receiving antibiotics (odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.5-1.7).

“Possible explanations for this high rate of potentially inappropriate treatment include the challenge of differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial infections, distinguishing asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the acute care setting, and gaps in knowledge about the benefits of antibiotic therapy,” the authors posited, adding that these findings “suggest a significant opportunity to improve patient safety, reduce the spread of resistance, and lower spending through greater adherence to guideline recommendations.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Lindenauer and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations, even though guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics during exacerbations of asthma in the absence of concurrent infection, reported Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, of Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and his colleagues.

They examined the hospitalization records of 51,951 individuals admitted to 577 hospitals in the United States between 2013 and 2014 with a principal diagnosis of either asthma or acute respiratory failure combined with asthma as a secondary diagnosis. Each patient type and the timing of antibiotic therapy was noted.

A total of 30,226 of the 51,951 patients (58.2%) were prescribed antibiotics at some point during their hospitalization, while 21,248 (40.9%) were prescribed antibiotics on the first day of hospitalization, without “documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.”

Macrolides were most commonly prescribed, given to 9,633 (18.5%) of patients, followed by quinolones (8,632, 16.1%), third-generation cephalosporins (4,420, 8.5%), and tetracyclines (1,858, 3.6%). After adjustment for risk variables, chronic obstructive asthma hospitalizations were found to be those most highly associated with receiving antibiotics (odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.5-1.7).

“Possible explanations for this high rate of potentially inappropriate treatment include the challenge of differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial infections, distinguishing asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the acute care setting, and gaps in knowledge about the benefits of antibiotic therapy,” the authors posited, adding that these findings “suggest a significant opportunity to improve patient safety, reduce the spread of resistance, and lower spending through greater adherence to guideline recommendations.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Lindenauer and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations, even though guidelines recommend against prescribing antibiotics during exacerbations of asthma in the absence of concurrent infection, reported Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, MSc, of Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and his colleagues.

They examined the hospitalization records of 51,951 individuals admitted to 577 hospitals in the United States between 2013 and 2014 with a principal diagnosis of either asthma or acute respiratory failure combined with asthma as a secondary diagnosis. Each patient type and the timing of antibiotic therapy was noted.

A total of 30,226 of the 51,951 patients (58.2%) were prescribed antibiotics at some point during their hospitalization, while 21,248 (40.9%) were prescribed antibiotics on the first day of hospitalization, without “documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.”

Macrolides were most commonly prescribed, given to 9,633 (18.5%) of patients, followed by quinolones (8,632, 16.1%), third-generation cephalosporins (4,420, 8.5%), and tetracyclines (1,858, 3.6%). After adjustment for risk variables, chronic obstructive asthma hospitalizations were found to be those most highly associated with receiving antibiotics (odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.5-1.7).

“Possible explanations for this high rate of potentially inappropriate treatment include the challenge of differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial infections, distinguishing asthma from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the acute care setting, and gaps in knowledge about the benefits of antibiotic therapy,” the authors posited, adding that these findings “suggest a significant opportunity to improve patient safety, reduce the spread of resistance, and lower spending through greater adherence to guideline recommendations.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Lindenauer and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Antibiotics are overprescribed in asthma-related hospitalizations.

Major finding: Among patients hospitalized for asthma, 58.2% had received antibiotics without any documentation or indication for such therapy.

Data source: Retrospective study of 51,951 patients in 577 U.S. hospitals from 2013 to 2014.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development funded the study. The researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Healthy donor stool safe, effective for recurrent CDI

For patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), based on a small trial reported online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In all, 20 of 22 patients (91%) achieved cure with donor FMT, compared with 63% of patients who received their own markedly dysbiotic stool (P = .04), reported Colleen Kelly, MD, of The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I., together with her associates. “Differences in efficacy between sites suggest that some patients with lower risk for CDI recurrence may not benefit from FMT. Further research may help determine the best candidates,” the researchers wrote.

FMT corrects the dysbiosis associated with CDI and is recommended in the event of failed antibiotic therapy leading to a third episode of infection. But this advice is based mainly on case series and open-label trials, the researchers noted. Their dual-center, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study included 46 patients with at least three recurrences of CDI who had completed a course of vancomycin during their most recent episode of infection. Patients older than age 75 years or who were immunocompromised were excluded (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271).

The overall clinical cure rates reflected the literature, the researchers reported, and all nine patients who developed CDI after autologous FMT were subsequently cured by donor FMT. Indeed, donor FMT “restored normal microbial community structure, with reductions in Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and increases in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. In contrast, microbial diversity did not improve after autologous FMT.”

Notably, however, 90% of autologous FMT patients at the center in New York achieved clinical cure, compared with 43% of patients at the center in Rhode Island. Further analyses revealed differences between patients and fecal microbiota at the two sites, the investigators said. Patients in New York typically had CDI for longer, with more recurrences and up to 148 weeks of vancomycin and other antibiotics. Thus, they might have been cured before enrollment. But “autologous FMT patients at the New York site [also] had greater abundances of Clostridia, raising the possibility of emergence of microbial community assemblages inhibitory to C. difficile via competitive niche exclusion, or possibly by emergence of nontoxigenic organisms,” the researchers wrote.

There were no serious adverse effects associated with either type of FMT, they noted.

Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

Kelly and her colleagues demonstrate that rigorous controlled trials are valuable even when we think we know the answer. Their results prompt us to ask again whether microbial manipulation has any as-yet unappreciated health benefits or risks and whether there are preferred microbiomes for specific human populations or locales.

Careful review of reported adverse events in the current trial is instructive. One participant reported a 9.1-kg weight gain (donor details were not provided), a problem previously described in a separate case report. There is great interest in understanding whether the microbiome can be manipulated to modify weight in humans, as has been clearly shown in mice. In addition, patients receiving donor stool more frequently reported chills. In my own practice, I have rarely observed transient fever after healthy donor FMT delivered orally in encapsulated form, and I hypothesize that this may be due to an immune reaction to a new microbial ecosystem. Patients considering FMT should be informed of both of these possible adverse events.

Elizabeth L. Hohmann, MD, is at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She reported grant support and personal fees from Seres Therapeutics outside the submitted work. These comments are from an editorial accompanying the article (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-1784).

AGA Resource

The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education was created to serve as a virtual ‘home’ for AGA activities related to the gut microbiome with a mission to advance research and education on the gut microbiome with the goal of improving human health. Learn more at www.gastro.org/microbiome.

Kelly and her colleagues demonstrate that rigorous controlled trials are valuable even when we think we know the answer. Their results prompt us to ask again whether microbial manipulation has any as-yet unappreciated health benefits or risks and whether there are preferred microbiomes for specific human populations or locales.

Careful review of reported adverse events in the current trial is instructive. One participant reported a 9.1-kg weight gain (donor details were not provided), a problem previously described in a separate case report. There is great interest in understanding whether the microbiome can be manipulated to modify weight in humans, as has been clearly shown in mice. In addition, patients receiving donor stool more frequently reported chills. In my own practice, I have rarely observed transient fever after healthy donor FMT delivered orally in encapsulated form, and I hypothesize that this may be due to an immune reaction to a new microbial ecosystem. Patients considering FMT should be informed of both of these possible adverse events.

Elizabeth L. Hohmann, MD, is at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She reported grant support and personal fees from Seres Therapeutics outside the submitted work. These comments are from an editorial accompanying the article (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-1784).

AGA Resource

The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education was created to serve as a virtual ‘home’ for AGA activities related to the gut microbiome with a mission to advance research and education on the gut microbiome with the goal of improving human health. Learn more at www.gastro.org/microbiome.

Kelly and her colleagues demonstrate that rigorous controlled trials are valuable even when we think we know the answer. Their results prompt us to ask again whether microbial manipulation has any as-yet unappreciated health benefits or risks and whether there are preferred microbiomes for specific human populations or locales.

Careful review of reported adverse events in the current trial is instructive. One participant reported a 9.1-kg weight gain (donor details were not provided), a problem previously described in a separate case report. There is great interest in understanding whether the microbiome can be manipulated to modify weight in humans, as has been clearly shown in mice. In addition, patients receiving donor stool more frequently reported chills. In my own practice, I have rarely observed transient fever after healthy donor FMT delivered orally in encapsulated form, and I hypothesize that this may be due to an immune reaction to a new microbial ecosystem. Patients considering FMT should be informed of both of these possible adverse events.

Elizabeth L. Hohmann, MD, is at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She reported grant support and personal fees from Seres Therapeutics outside the submitted work. These comments are from an editorial accompanying the article (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-1784).

AGA Resource

The AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education was created to serve as a virtual ‘home’ for AGA activities related to the gut microbiome with a mission to advance research and education on the gut microbiome with the goal of improving human health. Learn more at www.gastro.org/microbiome.

For patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), based on a small trial reported online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In all, 20 of 22 patients (91%) achieved cure with donor FMT, compared with 63% of patients who received their own markedly dysbiotic stool (P = .04), reported Colleen Kelly, MD, of The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I., together with her associates. “Differences in efficacy between sites suggest that some patients with lower risk for CDI recurrence may not benefit from FMT. Further research may help determine the best candidates,” the researchers wrote.

FMT corrects the dysbiosis associated with CDI and is recommended in the event of failed antibiotic therapy leading to a third episode of infection. But this advice is based mainly on case series and open-label trials, the researchers noted. Their dual-center, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study included 46 patients with at least three recurrences of CDI who had completed a course of vancomycin during their most recent episode of infection. Patients older than age 75 years or who were immunocompromised were excluded (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271).

The overall clinical cure rates reflected the literature, the researchers reported, and all nine patients who developed CDI after autologous FMT were subsequently cured by donor FMT. Indeed, donor FMT “restored normal microbial community structure, with reductions in Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and increases in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. In contrast, microbial diversity did not improve after autologous FMT.”

Notably, however, 90% of autologous FMT patients at the center in New York achieved clinical cure, compared with 43% of patients at the center in Rhode Island. Further analyses revealed differences between patients and fecal microbiota at the two sites, the investigators said. Patients in New York typically had CDI for longer, with more recurrences and up to 148 weeks of vancomycin and other antibiotics. Thus, they might have been cured before enrollment. But “autologous FMT patients at the New York site [also] had greater abundances of Clostridia, raising the possibility of emergence of microbial community assemblages inhibitory to C. difficile via competitive niche exclusion, or possibly by emergence of nontoxigenic organisms,” the researchers wrote.

There were no serious adverse effects associated with either type of FMT, they noted.

Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

For patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), based on a small trial reported online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In all, 20 of 22 patients (91%) achieved cure with donor FMT, compared with 63% of patients who received their own markedly dysbiotic stool (P = .04), reported Colleen Kelly, MD, of The Miriam Hospital, Providence, R.I., together with her associates. “Differences in efficacy between sites suggest that some patients with lower risk for CDI recurrence may not benefit from FMT. Further research may help determine the best candidates,” the researchers wrote.

FMT corrects the dysbiosis associated with CDI and is recommended in the event of failed antibiotic therapy leading to a third episode of infection. But this advice is based mainly on case series and open-label trials, the researchers noted. Their dual-center, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study included 46 patients with at least three recurrences of CDI who had completed a course of vancomycin during their most recent episode of infection. Patients older than age 75 years or who were immunocompromised were excluded (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 22. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271).

The overall clinical cure rates reflected the literature, the researchers reported, and all nine patients who developed CDI after autologous FMT were subsequently cured by donor FMT. Indeed, donor FMT “restored normal microbial community structure, with reductions in Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and increases in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. In contrast, microbial diversity did not improve after autologous FMT.”

Notably, however, 90% of autologous FMT patients at the center in New York achieved clinical cure, compared with 43% of patients at the center in Rhode Island. Further analyses revealed differences between patients and fecal microbiota at the two sites, the investigators said. Patients in New York typically had CDI for longer, with more recurrences and up to 148 weeks of vancomycin and other antibiotics. Thus, they might have been cured before enrollment. But “autologous FMT patients at the New York site [also] had greater abundances of Clostridia, raising the possibility of emergence of microbial community assemblages inhibitory to C. difficile via competitive niche exclusion, or possibly by emergence of nontoxigenic organisms,” the researchers wrote.

There were no serious adverse effects associated with either type of FMT, they noted.

Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Donor stool administered via colonoscopy seemed safe and achieved clinical cure significantly more often than autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).

Major finding: In all, 91% of donor FMT patients and 63% of autologous FMT patients achieved clinical cure stool (P = .04).

Data source: A prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of 46 patients with at least three episodes of CDI, who had completed a full course of vancomycin during the most recent episode.

Disclosures: Dr. Kelly disclosed ties to Seres Health outside the submitted work. Two coauthors had patents or patents pending for “compositions and methods for transplantation of colon microbiota.” A third coauthor disclosed ties to OpenBiome and personal fees from CIPAC/Crestovo outside the submitted work. The remaining coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

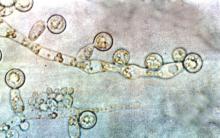

Candida auris in Venezuela outbreak is triazole-resistant, opportunistic

BOSTON – An investigation into 18 nosocomial Candida auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela showed that isolates of the emerging fungal pathogen obtained during the outbreak were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. However, the isolates were intermediately susceptible to amphotericin B and susceptible to 5-fluorocitosine, and demonstrated high susceptibility to the candin antifungal anidulafungin.

Dr. Belinda Calvo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and her collaborators reported these findings, related to a 2012-2013 C. auris outbreak at the hospital. Dr. Calvo and her coinvestigators noted that other invasive C. auris outbreaks have been reported in India, Korea, and South Africa, but that “the real prevalence of this organism may be underestimated,” since common rapid microbial identification techniques may misidentify the species.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology, Dr. Calvo and her collaborators reported that the 18 patients involved in the Venezuelan outbreak were critically ill, of whom 11 were pediatric, and all had central venous catheter placement. All but two of the pediatric patients were neonates, and all had serious underlying morbidities; several had significant congenital anomalies. The median patient age was 26 days (range, 2 days to 72 years), reflecting the high number of neonates affected. One of the adult patients had esophageal carcinoma. Overall, 10/18 patients (56%) had undergone surgical procedures, and all had received antibiotics.

As has been reported in other C. auris outbreaks, isolates from blood cultures of affected individuals were initially reported as C. haemulonii by the Vitek 2 C automated microbial identification system. Molecular identification was completed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA gene, with analysis aided by the National Institutes of Health’s GenBank and the Netherland’s CBS Fungal Diversity Centre , in order to confirm the identity of the fungal isolates as C. auris. Dr. Calvo and her associates were able to generate a dendrogram of the 18 isolates, showing high clonality, a trait shared with other nosocomial C. auris outbreaks.

Susceptibility testing of the C. auris cultured from blood samples of the affected patients showed that fluconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit the growth of 50% of the organisms (MIC50) of greater than 64 mcg/mL. For fluconazole, the MIC90, range, and geometric mean were all also above 64 mcg/mL, indicating a high level of resistance. For voriconazole, the MICs, range, and mean were all 4 mcg/mL. For amphotericin B, the MIC50 was 1 mcg/mL, the MIC90 was 2 mcg/mL, the range was 1-2, and the geometric mean was 1.414 mcg/mL.

The high number of pediatric patients affected, as well as early pathogen identification with speedy and appropriate antifungal therapy and prompt removal of central venous catheters, likely contributed to the relatively low 30-day crude mortality rate of 28%, said Dr. Calvo and her coauthors.

“C. auris should be considered an emergent multiresistant species,” wrote Dr. Calbo and her collaborators, noting that the opportunistic pathogen has a “high potential for nosocomial horizontal transmission.”

In June 2016, the Centers for Disease Control issued a clinical alert to U.S. healthcare facilities regarding the global emergence of invasive infections caused by C. auris.

The study authors reported no external sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – An investigation into 18 nosocomial Candida auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela showed that isolates of the emerging fungal pathogen obtained during the outbreak were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. However, the isolates were intermediately susceptible to amphotericin B and susceptible to 5-fluorocitosine, and demonstrated high susceptibility to the candin antifungal anidulafungin.

Dr. Belinda Calvo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and her collaborators reported these findings, related to a 2012-2013 C. auris outbreak at the hospital. Dr. Calvo and her coinvestigators noted that other invasive C. auris outbreaks have been reported in India, Korea, and South Africa, but that “the real prevalence of this organism may be underestimated,” since common rapid microbial identification techniques may misidentify the species.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology, Dr. Calvo and her collaborators reported that the 18 patients involved in the Venezuelan outbreak were critically ill, of whom 11 were pediatric, and all had central venous catheter placement. All but two of the pediatric patients were neonates, and all had serious underlying morbidities; several had significant congenital anomalies. The median patient age was 26 days (range, 2 days to 72 years), reflecting the high number of neonates affected. One of the adult patients had esophageal carcinoma. Overall, 10/18 patients (56%) had undergone surgical procedures, and all had received antibiotics.

As has been reported in other C. auris outbreaks, isolates from blood cultures of affected individuals were initially reported as C. haemulonii by the Vitek 2 C automated microbial identification system. Molecular identification was completed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA gene, with analysis aided by the National Institutes of Health’s GenBank and the Netherland’s CBS Fungal Diversity Centre , in order to confirm the identity of the fungal isolates as C. auris. Dr. Calvo and her associates were able to generate a dendrogram of the 18 isolates, showing high clonality, a trait shared with other nosocomial C. auris outbreaks.

Susceptibility testing of the C. auris cultured from blood samples of the affected patients showed that fluconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit the growth of 50% of the organisms (MIC50) of greater than 64 mcg/mL. For fluconazole, the MIC90, range, and geometric mean were all also above 64 mcg/mL, indicating a high level of resistance. For voriconazole, the MICs, range, and mean were all 4 mcg/mL. For amphotericin B, the MIC50 was 1 mcg/mL, the MIC90 was 2 mcg/mL, the range was 1-2, and the geometric mean was 1.414 mcg/mL.

The high number of pediatric patients affected, as well as early pathogen identification with speedy and appropriate antifungal therapy and prompt removal of central venous catheters, likely contributed to the relatively low 30-day crude mortality rate of 28%, said Dr. Calvo and her coauthors.

“C. auris should be considered an emergent multiresistant species,” wrote Dr. Calbo and her collaborators, noting that the opportunistic pathogen has a “high potential for nosocomial horizontal transmission.”

In June 2016, the Centers for Disease Control issued a clinical alert to U.S. healthcare facilities regarding the global emergence of invasive infections caused by C. auris.

The study authors reported no external sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – An investigation into 18 nosocomial Candida auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela showed that isolates of the emerging fungal pathogen obtained during the outbreak were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. However, the isolates were intermediately susceptible to amphotericin B and susceptible to 5-fluorocitosine, and demonstrated high susceptibility to the candin antifungal anidulafungin.

Dr. Belinda Calvo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Maracaibo, Venezuela, and her collaborators reported these findings, related to a 2012-2013 C. auris outbreak at the hospital. Dr. Calvo and her coinvestigators noted that other invasive C. auris outbreaks have been reported in India, Korea, and South Africa, but that “the real prevalence of this organism may be underestimated,” since common rapid microbial identification techniques may misidentify the species.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Microbiology, Dr. Calvo and her collaborators reported that the 18 patients involved in the Venezuelan outbreak were critically ill, of whom 11 were pediatric, and all had central venous catheter placement. All but two of the pediatric patients were neonates, and all had serious underlying morbidities; several had significant congenital anomalies. The median patient age was 26 days (range, 2 days to 72 years), reflecting the high number of neonates affected. One of the adult patients had esophageal carcinoma. Overall, 10/18 patients (56%) had undergone surgical procedures, and all had received antibiotics.

As has been reported in other C. auris outbreaks, isolates from blood cultures of affected individuals were initially reported as C. haemulonii by the Vitek 2 C automated microbial identification system. Molecular identification was completed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA gene, with analysis aided by the National Institutes of Health’s GenBank and the Netherland’s CBS Fungal Diversity Centre , in order to confirm the identity of the fungal isolates as C. auris. Dr. Calvo and her associates were able to generate a dendrogram of the 18 isolates, showing high clonality, a trait shared with other nosocomial C. auris outbreaks.

Susceptibility testing of the C. auris cultured from blood samples of the affected patients showed that fluconazole had a minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit the growth of 50% of the organisms (MIC50) of greater than 64 mcg/mL. For fluconazole, the MIC90, range, and geometric mean were all also above 64 mcg/mL, indicating a high level of resistance. For voriconazole, the MICs, range, and mean were all 4 mcg/mL. For amphotericin B, the MIC50 was 1 mcg/mL, the MIC90 was 2 mcg/mL, the range was 1-2, and the geometric mean was 1.414 mcg/mL.

The high number of pediatric patients affected, as well as early pathogen identification with speedy and appropriate antifungal therapy and prompt removal of central venous catheters, likely contributed to the relatively low 30-day crude mortality rate of 28%, said Dr. Calvo and her coauthors.

“C. auris should be considered an emergent multiresistant species,” wrote Dr. Calbo and her collaborators, noting that the opportunistic pathogen has a “high potential for nosocomial horizontal transmission.”

In June 2016, the Centers for Disease Control issued a clinical alert to U.S. healthcare facilities regarding the global emergence of invasive infections caused by C. auris.

The study authors reported no external sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM 2016

Key clinical point: Isolates in an outbreak of nosocomially acquired Candida auris were fluconazole-resistant.

Major finding: All C. auris isolates were resistant to fluconazole, with geometric mean minimum inhibitory concentrations greater than 64 mcg/mL.

Data source: Retrospective, single-center study of 18 pediatric and adult patients with C. auris infections at a tertiary care center in Venezuela.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no outside sources of funding and no disclosures.

Viruses on mobile phones

Mobile phones became commonplace in just a few years and are now used everywhere, included remote areas of the world. These communication tools are used for personal and professional purposes, frequently by health care workers (HCWs) during care.

We and others believe that mobile phones improve the quality, rapidity, and efficiency of communication in health care settings and, therefore, improve the management of patients. In fact, professional mobile phones allow communication between HCWs anywhere in the hospital. In addition, personal mobile phones, frequently smartphones, allow the use of medical apps for evidence-based management of patients.

Mobile phones, both professional and personal, are used in close proximity to patients, as reported in behavioral studies. In a recent study we performed in a hospital setting (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 May;22[5]:456.e1-e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.008), more than 60% of HCWs who participated declared using phones during care, and also declared that they had halted care to patients while answering a call.

Several studies have shown that mobile phones used at hospitals are contaminated by bacteria, including highly pathogenic ones, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter species, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Pseudomonas species, and coliforms. Research suggests that these devices may serve as a reservoir of bacteria known to cause nosocomial infections and may play a role in transmission of them to patients through the hands of HCWs.

For the first time, we demonstrated the presence of RNA of epidemic viruses such as rotavirus, influenza virus, syncytial respiratory virus, and metapneumovirus on mobile phones (professional and personal) held by HCWs. In our study, 38.5% of sampled mobile phones were contaminated with RNA from viruses. RNA of rotavirus was the most frequently-detected virus, mainly on phones sampled in the pediatric emergency ward. Interestingly, we found that HCWs in pediatric wards admitted disinfecting their mobile phones less frequently than did other HCWs we interviewed.

Epidemic viruses have already been discovered on other electronic device surfaces, such as keyboards, computers, and telephone handsets. However, in contrast to these other devices, mobile phones are mobile and could be shared and transported anywhere, including in close proximity to patients. Rotaviruses are frequently found on hospital surfaces several months after an epidemic period, after surfaces were cleaned. The high prevalence of rotavirus in pediatric ward patients during our study, and its capacity to persist in the environment, are probably the main factors that explain the high frequency of rotavirus RNA detection on mobile phones in our study.

This finding highlights the possible role of mobile phones in cross-transmission of epidemic viruses, with the transfer from nonporous fomites to fingers, and from fingers to fomites – including mobile phones. Due to the difficulty and fastidiousness of viral culture, the viruses were detected only by molecular biology; the viability of the viruses could not be demonstrated. However, we believe that cross-transmission of viruses may occur, notably in health care settings. The recently reported case of a 40-year-old Ugandan man who stole a phone from a patient with Ebola and contracted the disease, also supports this hypothesis.

We also demonstrated in our study that hand hygiene after the use of mobile phones does not seem to be systematic, even for HCWs continuing care that was in process before picking up their phones. Around 30% of HCWs declared that they never perform hand hygiene before or after handling mobile phones. In addition, more than 30% of HCWs admitted that they never disinfect their phones, even their professional ones; this lack of hygiene could contribute to the persistence of RNA of epidemic viruses.

Our study does not support banning the use of mobile phones in hospitals. We just want to make HCWs aware that mobile phones, which are part of our daily practice, can be contaminated by pathogens, notably viruses. The use of disinfection wipes to clean phones, together with adherence to hand hygiene, is crucial to prevent cross-transmission.

Frequent disinfection of personal and professional mobile phones needs to be promoted to reduce contamination of phones by viruses, especially during epidemics.

In practice, each clinician needs to remember that hand hygiene should be the last thing done before patient contact, as recommended by the World Health Organization. Touching a mobile phone could transfer bacteria or viruses onto hands, and we hypothesize that it could be a factor in cross-transmission of pathogens.

Elisabeth Botelho-Nevers, MD, PhD, is an infectious diseases specialist at the University Hospital of Saint-Étienne (France) and Sylvie Pillet, PharmD, PhD, is a virologist in the Laboratory of Infectious Agents and Hygiene, University Hospital of Saint-Étienne.

Mobile phones became commonplace in just a few years and are now used everywhere, included remote areas of the world. These communication tools are used for personal and professional purposes, frequently by health care workers (HCWs) during care.

We and others believe that mobile phones improve the quality, rapidity, and efficiency of communication in health care settings and, therefore, improve the management of patients. In fact, professional mobile phones allow communication between HCWs anywhere in the hospital. In addition, personal mobile phones, frequently smartphones, allow the use of medical apps for evidence-based management of patients.

Mobile phones, both professional and personal, are used in close proximity to patients, as reported in behavioral studies. In a recent study we performed in a hospital setting (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 May;22[5]:456.e1-e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.008), more than 60% of HCWs who participated declared using phones during care, and also declared that they had halted care to patients while answering a call.

Several studies have shown that mobile phones used at hospitals are contaminated by bacteria, including highly pathogenic ones, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter species, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Pseudomonas species, and coliforms. Research suggests that these devices may serve as a reservoir of bacteria known to cause nosocomial infections and may play a role in transmission of them to patients through the hands of HCWs.

For the first time, we demonstrated the presence of RNA of epidemic viruses such as rotavirus, influenza virus, syncytial respiratory virus, and metapneumovirus on mobile phones (professional and personal) held by HCWs. In our study, 38.5% of sampled mobile phones were contaminated with RNA from viruses. RNA of rotavirus was the most frequently-detected virus, mainly on phones sampled in the pediatric emergency ward. Interestingly, we found that HCWs in pediatric wards admitted disinfecting their mobile phones less frequently than did other HCWs we interviewed.

Epidemic viruses have already been discovered on other electronic device surfaces, such as keyboards, computers, and telephone handsets. However, in contrast to these other devices, mobile phones are mobile and could be shared and transported anywhere, including in close proximity to patients. Rotaviruses are frequently found on hospital surfaces several months after an epidemic period, after surfaces were cleaned. The high prevalence of rotavirus in pediatric ward patients during our study, and its capacity to persist in the environment, are probably the main factors that explain the high frequency of rotavirus RNA detection on mobile phones in our study.

This finding highlights the possible role of mobile phones in cross-transmission of epidemic viruses, with the transfer from nonporous fomites to fingers, and from fingers to fomites – including mobile phones. Due to the difficulty and fastidiousness of viral culture, the viruses were detected only by molecular biology; the viability of the viruses could not be demonstrated. However, we believe that cross-transmission of viruses may occur, notably in health care settings. The recently reported case of a 40-year-old Ugandan man who stole a phone from a patient with Ebola and contracted the disease, also supports this hypothesis.

We also demonstrated in our study that hand hygiene after the use of mobile phones does not seem to be systematic, even for HCWs continuing care that was in process before picking up their phones. Around 30% of HCWs declared that they never perform hand hygiene before or after handling mobile phones. In addition, more than 30% of HCWs admitted that they never disinfect their phones, even their professional ones; this lack of hygiene could contribute to the persistence of RNA of epidemic viruses.

Our study does not support banning the use of mobile phones in hospitals. We just want to make HCWs aware that mobile phones, which are part of our daily practice, can be contaminated by pathogens, notably viruses. The use of disinfection wipes to clean phones, together with adherence to hand hygiene, is crucial to prevent cross-transmission.

Frequent disinfection of personal and professional mobile phones needs to be promoted to reduce contamination of phones by viruses, especially during epidemics.

In practice, each clinician needs to remember that hand hygiene should be the last thing done before patient contact, as recommended by the World Health Organization. Touching a mobile phone could transfer bacteria or viruses onto hands, and we hypothesize that it could be a factor in cross-transmission of pathogens.

Elisabeth Botelho-Nevers, MD, PhD, is an infectious diseases specialist at the University Hospital of Saint-Étienne (France) and Sylvie Pillet, PharmD, PhD, is a virologist in the Laboratory of Infectious Agents and Hygiene, University Hospital of Saint-Étienne.

Mobile phones became commonplace in just a few years and are now used everywhere, included remote areas of the world. These communication tools are used for personal and professional purposes, frequently by health care workers (HCWs) during care.

We and others believe that mobile phones improve the quality, rapidity, and efficiency of communication in health care settings and, therefore, improve the management of patients. In fact, professional mobile phones allow communication between HCWs anywhere in the hospital. In addition, personal mobile phones, frequently smartphones, allow the use of medical apps for evidence-based management of patients.

Mobile phones, both professional and personal, are used in close proximity to patients, as reported in behavioral studies. In a recent study we performed in a hospital setting (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 May;22[5]:456.e1-e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.008), more than 60% of HCWs who participated declared using phones during care, and also declared that they had halted care to patients while answering a call.

Several studies have shown that mobile phones used at hospitals are contaminated by bacteria, including highly pathogenic ones, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter species, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Pseudomonas species, and coliforms. Research suggests that these devices may serve as a reservoir of bacteria known to cause nosocomial infections and may play a role in transmission of them to patients through the hands of HCWs.

For the first time, we demonstrated the presence of RNA of epidemic viruses such as rotavirus, influenza virus, syncytial respiratory virus, and metapneumovirus on mobile phones (professional and personal) held by HCWs. In our study, 38.5% of sampled mobile phones were contaminated with RNA from viruses. RNA of rotavirus was the most frequently-detected virus, mainly on phones sampled in the pediatric emergency ward. Interestingly, we found that HCWs in pediatric wards admitted disinfecting their mobile phones less frequently than did other HCWs we interviewed.

Epidemic viruses have already been discovered on other electronic device surfaces, such as keyboards, computers, and telephone handsets. However, in contrast to these other devices, mobile phones are mobile and could be shared and transported anywhere, including in close proximity to patients. Rotaviruses are frequently found on hospital surfaces several months after an epidemic period, after surfaces were cleaned. The high prevalence of rotavirus in pediatric ward patients during our study, and its capacity to persist in the environment, are probably the main factors that explain the high frequency of rotavirus RNA detection on mobile phones in our study.

This finding highlights the possible role of mobile phones in cross-transmission of epidemic viruses, with the transfer from nonporous fomites to fingers, and from fingers to fomites – including mobile phones. Due to the difficulty and fastidiousness of viral culture, the viruses were detected only by molecular biology; the viability of the viruses could not be demonstrated. However, we believe that cross-transmission of viruses may occur, notably in health care settings. The recently reported case of a 40-year-old Ugandan man who stole a phone from a patient with Ebola and contracted the disease, also supports this hypothesis.

We also demonstrated in our study that hand hygiene after the use of mobile phones does not seem to be systematic, even for HCWs continuing care that was in process before picking up their phones. Around 30% of HCWs declared that they never perform hand hygiene before or after handling mobile phones. In addition, more than 30% of HCWs admitted that they never disinfect their phones, even their professional ones; this lack of hygiene could contribute to the persistence of RNA of epidemic viruses.

Our study does not support banning the use of mobile phones in hospitals. We just want to make HCWs aware that mobile phones, which are part of our daily practice, can be contaminated by pathogens, notably viruses. The use of disinfection wipes to clean phones, together with adherence to hand hygiene, is crucial to prevent cross-transmission.

Frequent disinfection of personal and professional mobile phones needs to be promoted to reduce contamination of phones by viruses, especially during epidemics.

In practice, each clinician needs to remember that hand hygiene should be the last thing done before patient contact, as recommended by the World Health Organization. Touching a mobile phone could transfer bacteria or viruses onto hands, and we hypothesize that it could be a factor in cross-transmission of pathogens.

Elisabeth Botelho-Nevers, MD, PhD, is an infectious diseases specialist at the University Hospital of Saint-Étienne (France) and Sylvie Pillet, PharmD, PhD, is a virologist in the Laboratory of Infectious Agents and Hygiene, University Hospital of Saint-Étienne.

U.S. to jump-start antibiotic resistance research

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

In septic shock, vasopressin not better than norepinephrine

Vasopressin was no better than norepinephrine in preventing kidney failure when used as a first-line treatment for septic shock, according to a report published online Aug. 2 in JAMA.

In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial comparing the two approaches in 408 ICU patients with septic shock, the early use of vasopressin didn’t reduce the number of days free of kidney failure, compared with standard norepinephrine.

However, “the 95% confidence intervals of the difference between [study] groups has an upper limit of 5 days in favor of vasopressin, which could be clinically important,” said Anthony C. Gordon, MD, of Charing Cross Hospital and Imperial College London, and his associates. “Therefore, these results are still consistent with a potentially clinically important benefit for vasopressin; but a larger trial would be needed to confirm or refute this.”

Norepinephrine is the recommended first-line vasopressor for septic shock, but “there has been a growing interest in the use of vasopressin” ever since researchers described a relative deficiency of vasopressin in the disorder, Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

“Preclinical and small clinical studies have suggested that vasopressin may be better able to maintain glomerular filtration rate and improve creatinine clearance, compared with norepinephrine,” the investigators said, and other studies have suggested that combining vasopressin with corticosteroids may prevent deterioration in organ function and reduce the duration of shock, thereby improving survival.

To examine those possibilities, they performed the VANISH (Vasopressin vs. Norepinephrine as Initial Therapy in Septic Shock) trial, assessing patients age 16 years and older at 18 general adult ICUs in the United Kingdom during a 2-year period. The study participants were randomly assigned to receive vasopressin plus hydrocortisone (100 patients), vasopressin plus matching placebo (104 patients), norepinephrine plus hydrocortisone (101 patients), or norepinephrine plus matching placebo (103 patients).

The primary outcome measure was the number of days alive and free of kidney failure during the 28 days following randomization. There was no significant difference among the four study groups in the number or the distribution of kidney-failure–free days, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016 Aug 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10485).

In addition, the percentage of survivors who never developed kidney failure was not significantly different between the two groups who received vasopressin (57.0%) and the two who received norepinephrine (59.2%). And the median number of days free of kidney failure in the subgroup of patients who died or developed kidney failure was not significantly different between those receiving vasopressin (9 days) and those receiving norepinephrine (13 days).

The quantities of IV fluids administered, the total fluid balance, serum lactate levels, and heart rate were all similar across the four study groups. There also was no significant difference in 28-day mortality between patients who received vasopressin (30.9%) and those who received norepinephrine (27.5%). Adverse event profiles also were comparable.

However, the rate of renal replacement therapy was 25.4% with vasopressin, significantly lower than the 35.3% rate in the norepinephrine group. The use of such therapy was not controlled in the trial and was initiated according to the treating physicians’ preference. “It is therefore not possible to know why renal replacement therapy was or was not started,” Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.