User login

Hepatitis C incidence rising in hemodialysis patients

Incidence of newly acquired hepatitis C virus has increased recently in patients undergoing hemodialysis, according to a health advisory from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2014 and 2015, 36 cases of HCV infection were reported to the CDC from 19 clinics in eight states. While investigation is ongoing, HCV transmission between patients has been confirmed in at least nine facilities, and in several facilities, lapses in infection control were also identified. Better screening and awareness of HCV infection potential may also play a role in the increased disease incidence.

The CDC recommends that dialysis facilities assess current infection control practices, environmental cleaning, and disinfection practices to evaluate adherence to standards, address any gaps, screen patients for HCV, and to report all HCV infections to the CDC promptly.

“Dialysis facilities should actively assess and continuously improve their infection control, environmental cleaning and disinfection, and HCV screening practices, whether or not they are aware of infections in their clinic. Any case of new HCV infection in a patient undergoing hemodialysis is likely to be a health care–associated infection and should be reported to public health authorities in a timely manner,” the CDC said

Find the full health advisory on the CDC website.

Incidence of newly acquired hepatitis C virus has increased recently in patients undergoing hemodialysis, according to a health advisory from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2014 and 2015, 36 cases of HCV infection were reported to the CDC from 19 clinics in eight states. While investigation is ongoing, HCV transmission between patients has been confirmed in at least nine facilities, and in several facilities, lapses in infection control were also identified. Better screening and awareness of HCV infection potential may also play a role in the increased disease incidence.

The CDC recommends that dialysis facilities assess current infection control practices, environmental cleaning, and disinfection practices to evaluate adherence to standards, address any gaps, screen patients for HCV, and to report all HCV infections to the CDC promptly.

“Dialysis facilities should actively assess and continuously improve their infection control, environmental cleaning and disinfection, and HCV screening practices, whether or not they are aware of infections in their clinic. Any case of new HCV infection in a patient undergoing hemodialysis is likely to be a health care–associated infection and should be reported to public health authorities in a timely manner,” the CDC said

Find the full health advisory on the CDC website.

Incidence of newly acquired hepatitis C virus has increased recently in patients undergoing hemodialysis, according to a health advisory from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2014 and 2015, 36 cases of HCV infection were reported to the CDC from 19 clinics in eight states. While investigation is ongoing, HCV transmission between patients has been confirmed in at least nine facilities, and in several facilities, lapses in infection control were also identified. Better screening and awareness of HCV infection potential may also play a role in the increased disease incidence.

The CDC recommends that dialysis facilities assess current infection control practices, environmental cleaning, and disinfection practices to evaluate adherence to standards, address any gaps, screen patients for HCV, and to report all HCV infections to the CDC promptly.

“Dialysis facilities should actively assess and continuously improve their infection control, environmental cleaning and disinfection, and HCV screening practices, whether or not they are aware of infections in their clinic. Any case of new HCV infection in a patient undergoing hemodialysis is likely to be a health care–associated infection and should be reported to public health authorities in a timely manner,” the CDC said

Find the full health advisory on the CDC website.

VIDEO: One in five hospital patients get health care–acquired infection

PHOENIX – If you happen to believe that the impact of health care–acquired infections is insignificant, think again. According to Dr. Kevin W. Lobdell, health care–acquired infections (HAIs) cause more deaths each year in the United States than breast cancer, lung cancer, and AIDS combined.

“If you look at hospitalized patients, one in five will acquire a health care–acquired infection,” Dr. Lobdell of the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute at Carolinas Health System, Charlotte, N.C., said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “With respect to length of stay, that goes from 5 days on average for a normal, uninfected patient, to 22 days if they’ve had an infection. The mortality rate can be as high as 6% in those people that have developed infections, so that in itself is an enormous burden.”

He went on to discuss the most common HAIs in the hospital setting and noted that combating them involves strategies that consider people, the environment, and technology. He predicted that in coming years clinicians will have a better “analytic capability to understand what we’ve done in the past and what correlates with success in the future, and then be able to implement and learn from that.”

Dr. Lobdell reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – If you happen to believe that the impact of health care–acquired infections is insignificant, think again. According to Dr. Kevin W. Lobdell, health care–acquired infections (HAIs) cause more deaths each year in the United States than breast cancer, lung cancer, and AIDS combined.

“If you look at hospitalized patients, one in five will acquire a health care–acquired infection,” Dr. Lobdell of the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute at Carolinas Health System, Charlotte, N.C., said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “With respect to length of stay, that goes from 5 days on average for a normal, uninfected patient, to 22 days if they’ve had an infection. The mortality rate can be as high as 6% in those people that have developed infections, so that in itself is an enormous burden.”

He went on to discuss the most common HAIs in the hospital setting and noted that combating them involves strategies that consider people, the environment, and technology. He predicted that in coming years clinicians will have a better “analytic capability to understand what we’ve done in the past and what correlates with success in the future, and then be able to implement and learn from that.”

Dr. Lobdell reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – If you happen to believe that the impact of health care–acquired infections is insignificant, think again. According to Dr. Kevin W. Lobdell, health care–acquired infections (HAIs) cause more deaths each year in the United States than breast cancer, lung cancer, and AIDS combined.

“If you look at hospitalized patients, one in five will acquire a health care–acquired infection,” Dr. Lobdell of the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute at Carolinas Health System, Charlotte, N.C., said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “With respect to length of stay, that goes from 5 days on average for a normal, uninfected patient, to 22 days if they’ve had an infection. The mortality rate can be as high as 6% in those people that have developed infections, so that in itself is an enormous burden.”

He went on to discuss the most common HAIs in the hospital setting and noted that combating them involves strategies that consider people, the environment, and technology. He predicted that in coming years clinicians will have a better “analytic capability to understand what we’ve done in the past and what correlates with success in the future, and then be able to implement and learn from that.”

Dr. Lobdell reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Preventing healthcare acquired infections after CT surgery

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Limit antibiotics to 4 days for percutaneous abdominal infection drainage

SAN ANTONIO – Four days of antibiotics is sufficient and safe for percutaneous drainage of complicated intra-abdominal infections in non-ICU patients, according to investigators from the University of Miami.

“There was no difference in outcome between a shorter and longer duration of antimicrobial therapy in those with percutaneously drained source control of a CIAI [complicated intra-abdominal infection]. Percutaneously drained intra-abdominal infections do not require longer duration of antimicrobial therapy,” they concluded.

The findings are from a posthoc subgroup analysis of the influential STOP-IT [Study to Optimize Peritoneal Infection Therapy] trial, which found that in CIAI patients with adequate source control, “the outcomes after fixed-duration antibiotic therapy (approximately 4 days) were similar to those after a longer course of antibiotics (approximately 7 days) that extended until after the resolution of physiological abnormalities” (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21;372[21]:1996-2005).

STOP-IT lumped together patients who had both surgical and percutaneous source control. Unlike surgical clean out, percutaneous drainage usually leaves behind some infection; the Miami investigators wanted to see if that made a difference in the safety and effectiveness of short-course antibiotics. Seventy-two patients received a 4-day course and 57 were on antibiotics until 2 days after their symptoms resolved, which usually worked out to about 7 days.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the rates of recurrent intra-abdominal infection (9.7% in the 4-day group vs. 10.5% in the longer-duration group, P = 1.00), Clostridium difficile infection (0% vs. 1.8%; P = .442), and hospital days (a mean of 4 days in both). The only difference was that the time to recurrent infection was shorter in the 4-day group (12.7 vs. 21.3 days; P = .015). None of the patients died.

The big caveat with STOP-IT and the posthoc analysis is that the patients weren’t very sick. Their mean APACHE [Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation] score was 10, and fevers and leukocytosis were generally mild. Patients without adequate source control, patients with open abdomens, and those likely to die within 72 hours were excluded.

“They were very different from our patients in the ICU with major complex intra-abdominal infections and septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction. To take STOP-IT or our analysis and say we are going to extrapolate that to our sickest patients and stop their antibiotics at 4 days is dangerous without further study. That’s the population everyone’s asking about now. We need a larger [randomized, controlled trial] in a much sicker population” to know how to handle the issue, said posthoc investigator Dr. Rishi Rattan, a critical care and trauma surgery fellow at the University of Miami.

The other big question, as raised by an audience member, and one at the other end of the spectrum is if antibiotics are needed at all after adequate source control, at least in some patients.

“We should look at that. I think we need to push the envelope and drill down even further to 48 and 24 hours, and study that versus 4 days,” Dr. Rattan said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

Patients in STOP-IT were aged 16 years and older with either a temperature of at least 38º C, white blood cell counts of 11,000 cells/mm3 or higher, or peritonitis-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, and illness severity were similar between treatment arms. Appendicitis was limited to about 10% of infections, so there was a diversity of infections and heterogeneity in the study population. Antibiotic selection was empiric, based on investigators’ institutions.

Based on STOP-IT, the University of Miami now usually limits antibiotics to 4 days after source control of CIAI in less-sick patients. The University was a STOP-IT site, which is why the posthoc team had access to the data.

The investigators have no disclosures.

This project is an important one. We hit [complicated intra-abdominal infection patients] hard and fast, and they do better, but when do we stop?

We all know that we give antibiotics for too long and to the wrong patients, and that this isn’t for free. Increased costs, drug resistance, and C. difficile infections result. But like training wheels and crutches, it’s hard to know when to give them up. The authors tackled this question, but patients without adequate source control were excluded and the study was underpowered. We know shorter courses of antibiotics are probably the right thing, but how do we prove it?

Dr. Jennifer Knight is an acute care surgeon at the West Virginia University in Morgantown. She has no disclosures.

This project is an important one. We hit [complicated intra-abdominal infection patients] hard and fast, and they do better, but when do we stop?

We all know that we give antibiotics for too long and to the wrong patients, and that this isn’t for free. Increased costs, drug resistance, and C. difficile infections result. But like training wheels and crutches, it’s hard to know when to give them up. The authors tackled this question, but patients without adequate source control were excluded and the study was underpowered. We know shorter courses of antibiotics are probably the right thing, but how do we prove it?

Dr. Jennifer Knight is an acute care surgeon at the West Virginia University in Morgantown. She has no disclosures.

This project is an important one. We hit [complicated intra-abdominal infection patients] hard and fast, and they do better, but when do we stop?

We all know that we give antibiotics for too long and to the wrong patients, and that this isn’t for free. Increased costs, drug resistance, and C. difficile infections result. But like training wheels and crutches, it’s hard to know when to give them up. The authors tackled this question, but patients without adequate source control were excluded and the study was underpowered. We know shorter courses of antibiotics are probably the right thing, but how do we prove it?

Dr. Jennifer Knight is an acute care surgeon at the West Virginia University in Morgantown. She has no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Four days of antibiotics is sufficient and safe for percutaneous drainage of complicated intra-abdominal infections in non-ICU patients, according to investigators from the University of Miami.

“There was no difference in outcome between a shorter and longer duration of antimicrobial therapy in those with percutaneously drained source control of a CIAI [complicated intra-abdominal infection]. Percutaneously drained intra-abdominal infections do not require longer duration of antimicrobial therapy,” they concluded.

The findings are from a posthoc subgroup analysis of the influential STOP-IT [Study to Optimize Peritoneal Infection Therapy] trial, which found that in CIAI patients with adequate source control, “the outcomes after fixed-duration antibiotic therapy (approximately 4 days) were similar to those after a longer course of antibiotics (approximately 7 days) that extended until after the resolution of physiological abnormalities” (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21;372[21]:1996-2005).

STOP-IT lumped together patients who had both surgical and percutaneous source control. Unlike surgical clean out, percutaneous drainage usually leaves behind some infection; the Miami investigators wanted to see if that made a difference in the safety and effectiveness of short-course antibiotics. Seventy-two patients received a 4-day course and 57 were on antibiotics until 2 days after their symptoms resolved, which usually worked out to about 7 days.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the rates of recurrent intra-abdominal infection (9.7% in the 4-day group vs. 10.5% in the longer-duration group, P = 1.00), Clostridium difficile infection (0% vs. 1.8%; P = .442), and hospital days (a mean of 4 days in both). The only difference was that the time to recurrent infection was shorter in the 4-day group (12.7 vs. 21.3 days; P = .015). None of the patients died.

The big caveat with STOP-IT and the posthoc analysis is that the patients weren’t very sick. Their mean APACHE [Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation] score was 10, and fevers and leukocytosis were generally mild. Patients without adequate source control, patients with open abdomens, and those likely to die within 72 hours were excluded.

“They were very different from our patients in the ICU with major complex intra-abdominal infections and septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction. To take STOP-IT or our analysis and say we are going to extrapolate that to our sickest patients and stop their antibiotics at 4 days is dangerous without further study. That’s the population everyone’s asking about now. We need a larger [randomized, controlled trial] in a much sicker population” to know how to handle the issue, said posthoc investigator Dr. Rishi Rattan, a critical care and trauma surgery fellow at the University of Miami.

The other big question, as raised by an audience member, and one at the other end of the spectrum is if antibiotics are needed at all after adequate source control, at least in some patients.

“We should look at that. I think we need to push the envelope and drill down even further to 48 and 24 hours, and study that versus 4 days,” Dr. Rattan said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

Patients in STOP-IT were aged 16 years and older with either a temperature of at least 38º C, white blood cell counts of 11,000 cells/mm3 or higher, or peritonitis-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, and illness severity were similar between treatment arms. Appendicitis was limited to about 10% of infections, so there was a diversity of infections and heterogeneity in the study population. Antibiotic selection was empiric, based on investigators’ institutions.

Based on STOP-IT, the University of Miami now usually limits antibiotics to 4 days after source control of CIAI in less-sick patients. The University was a STOP-IT site, which is why the posthoc team had access to the data.

The investigators have no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Four days of antibiotics is sufficient and safe for percutaneous drainage of complicated intra-abdominal infections in non-ICU patients, according to investigators from the University of Miami.

“There was no difference in outcome between a shorter and longer duration of antimicrobial therapy in those with percutaneously drained source control of a CIAI [complicated intra-abdominal infection]. Percutaneously drained intra-abdominal infections do not require longer duration of antimicrobial therapy,” they concluded.

The findings are from a posthoc subgroup analysis of the influential STOP-IT [Study to Optimize Peritoneal Infection Therapy] trial, which found that in CIAI patients with adequate source control, “the outcomes after fixed-duration antibiotic therapy (approximately 4 days) were similar to those after a longer course of antibiotics (approximately 7 days) that extended until after the resolution of physiological abnormalities” (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21;372[21]:1996-2005).

STOP-IT lumped together patients who had both surgical and percutaneous source control. Unlike surgical clean out, percutaneous drainage usually leaves behind some infection; the Miami investigators wanted to see if that made a difference in the safety and effectiveness of short-course antibiotics. Seventy-two patients received a 4-day course and 57 were on antibiotics until 2 days after their symptoms resolved, which usually worked out to about 7 days.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the rates of recurrent intra-abdominal infection (9.7% in the 4-day group vs. 10.5% in the longer-duration group, P = 1.00), Clostridium difficile infection (0% vs. 1.8%; P = .442), and hospital days (a mean of 4 days in both). The only difference was that the time to recurrent infection was shorter in the 4-day group (12.7 vs. 21.3 days; P = .015). None of the patients died.

The big caveat with STOP-IT and the posthoc analysis is that the patients weren’t very sick. Their mean APACHE [Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation] score was 10, and fevers and leukocytosis were generally mild. Patients without adequate source control, patients with open abdomens, and those likely to die within 72 hours were excluded.

“They were very different from our patients in the ICU with major complex intra-abdominal infections and septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction. To take STOP-IT or our analysis and say we are going to extrapolate that to our sickest patients and stop their antibiotics at 4 days is dangerous without further study. That’s the population everyone’s asking about now. We need a larger [randomized, controlled trial] in a much sicker population” to know how to handle the issue, said posthoc investigator Dr. Rishi Rattan, a critical care and trauma surgery fellow at the University of Miami.

The other big question, as raised by an audience member, and one at the other end of the spectrum is if antibiotics are needed at all after adequate source control, at least in some patients.

“We should look at that. I think we need to push the envelope and drill down even further to 48 and 24 hours, and study that versus 4 days,” Dr. Rattan said at the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma scientific assembly.

Patients in STOP-IT were aged 16 years and older with either a temperature of at least 38º C, white blood cell counts of 11,000 cells/mm3 or higher, or peritonitis-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, and illness severity were similar between treatment arms. Appendicitis was limited to about 10% of infections, so there was a diversity of infections and heterogeneity in the study population. Antibiotic selection was empiric, based on investigators’ institutions.

Based on STOP-IT, the University of Miami now usually limits antibiotics to 4 days after source control of CIAI in less-sick patients. The University was a STOP-IT site, which is why the posthoc team had access to the data.

The investigators have no disclosures.

AT The EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: For patients who aren’t too sick, a 4-day course of antibiotics is adequate for percutaneous drainage of complicated intra-abdominal infections.

Major finding: The rate of recurrent infection is the same whether patients have a 4- or 7-day course (9.7% vs. 10.5%; P = 1.00),

Data source: Posthoc analysis of 129 patients in the STOP-IT trial

Disclosures: The investigators have no disclosures.

Patient isolation key to containing in-hospital norovirus

Patient isolation in their own rooms is the most important factor in controlling outbreaks of norovirus within hospitals, according to a report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Investigators surveyed six London hospitals for a 3-month period to gather data concerning norovirus outbreaks. They assessed two teaching hospitals with 230 and 780 beds, respectively; one specialist center with 160 beds; two district general hospitals with 284 and 650 beds, respectively; and one 100-bed community hospital. There were 20 norovirus outbreaks during the survey period involving 57 patients and 7 staff members, said Martina Cummins, a nurse consultant and deputy director, Infection Prevention and Control, Bart’s Health NHS Trust, Ilford (England) and Derren Ready, a clinical scientist at Public Health England, London.

The number of outbreaks varied markedly among the different hospitals. The smaller teaching hospital and the smaller district general hospital had zero outbreaks, while the specialist hospital and the community hospital had only one outbreak each involving only three and six patients, respectively. The larger teaching hospital had two outbreaks involving only four patients in total. In contrast, the larger district general hospital, which had an older infrastructure, had 16 separate outbreaks involving 44 patients, and it was the only facility in which staff members (7) also became ill.

The ability to control an outbreak of norovirus hinged on the availability of isolation rooms. All the hospitals with two or fewer outbreaks had easily available isolation rooms, while the hospital that had numerous outbreaks did not. The most severely affected hospital had large wards caring for up to 26 patients, with limited or no barriers between beds. The beds in these wards were closer together (within 2.3 meters) than those in all the other hospitals. In addition, this hospital had limited care facilities, including only two sinks per ward for staff members to use and only four shared toilets per ward, Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready said (J Infect Dis. 2016;213[S1]:S12-S14. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv529).

Norovirus outbreaks among patients can have a major impact on the affected departments, wards, or clinical areas, but those that extend to staff members can lead to severe staffing shortages that close down whole wards or even entire hospitals, they noted.

No sponsor or funding source was identified for this study. Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Patient isolation in their own rooms is the most important factor in controlling outbreaks of norovirus within hospitals, according to a report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Investigators surveyed six London hospitals for a 3-month period to gather data concerning norovirus outbreaks. They assessed two teaching hospitals with 230 and 780 beds, respectively; one specialist center with 160 beds; two district general hospitals with 284 and 650 beds, respectively; and one 100-bed community hospital. There were 20 norovirus outbreaks during the survey period involving 57 patients and 7 staff members, said Martina Cummins, a nurse consultant and deputy director, Infection Prevention and Control, Bart’s Health NHS Trust, Ilford (England) and Derren Ready, a clinical scientist at Public Health England, London.

The number of outbreaks varied markedly among the different hospitals. The smaller teaching hospital and the smaller district general hospital had zero outbreaks, while the specialist hospital and the community hospital had only one outbreak each involving only three and six patients, respectively. The larger teaching hospital had two outbreaks involving only four patients in total. In contrast, the larger district general hospital, which had an older infrastructure, had 16 separate outbreaks involving 44 patients, and it was the only facility in which staff members (7) also became ill.

The ability to control an outbreak of norovirus hinged on the availability of isolation rooms. All the hospitals with two or fewer outbreaks had easily available isolation rooms, while the hospital that had numerous outbreaks did not. The most severely affected hospital had large wards caring for up to 26 patients, with limited or no barriers between beds. The beds in these wards were closer together (within 2.3 meters) than those in all the other hospitals. In addition, this hospital had limited care facilities, including only two sinks per ward for staff members to use and only four shared toilets per ward, Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready said (J Infect Dis. 2016;213[S1]:S12-S14. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv529).

Norovirus outbreaks among patients can have a major impact on the affected departments, wards, or clinical areas, but those that extend to staff members can lead to severe staffing shortages that close down whole wards or even entire hospitals, they noted.

No sponsor or funding source was identified for this study. Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Patient isolation in their own rooms is the most important factor in controlling outbreaks of norovirus within hospitals, according to a report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Investigators surveyed six London hospitals for a 3-month period to gather data concerning norovirus outbreaks. They assessed two teaching hospitals with 230 and 780 beds, respectively; one specialist center with 160 beds; two district general hospitals with 284 and 650 beds, respectively; and one 100-bed community hospital. There were 20 norovirus outbreaks during the survey period involving 57 patients and 7 staff members, said Martina Cummins, a nurse consultant and deputy director, Infection Prevention and Control, Bart’s Health NHS Trust, Ilford (England) and Derren Ready, a clinical scientist at Public Health England, London.

The number of outbreaks varied markedly among the different hospitals. The smaller teaching hospital and the smaller district general hospital had zero outbreaks, while the specialist hospital and the community hospital had only one outbreak each involving only three and six patients, respectively. The larger teaching hospital had two outbreaks involving only four patients in total. In contrast, the larger district general hospital, which had an older infrastructure, had 16 separate outbreaks involving 44 patients, and it was the only facility in which staff members (7) also became ill.

The ability to control an outbreak of norovirus hinged on the availability of isolation rooms. All the hospitals with two or fewer outbreaks had easily available isolation rooms, while the hospital that had numerous outbreaks did not. The most severely affected hospital had large wards caring for up to 26 patients, with limited or no barriers between beds. The beds in these wards were closer together (within 2.3 meters) than those in all the other hospitals. In addition, this hospital had limited care facilities, including only two sinks per ward for staff members to use and only four shared toilets per ward, Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready said (J Infect Dis. 2016;213[S1]:S12-S14. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv529).

Norovirus outbreaks among patients can have a major impact on the affected departments, wards, or clinical areas, but those that extend to staff members can lead to severe staffing shortages that close down whole wards or even entire hospitals, they noted.

No sponsor or funding source was identified for this study. Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Patient isolation is the key to containing norovirus outbreaks within hospitals.

Major finding: All five hospitals with two or fewer outbreaks had easily available isolation rooms, while the one hospital that had 16 outbreaks did not.

Data source: An enhanced surveillance study of six London hospitals that had 20 norovirus outbreaks involving 57 patients and 7 staff members during a 3-month period.

Disclosures: No sponsor or funding source was identified for this study. Ms. Cummins and Mr. Ready reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Frozen noninferior to fresh fecal microbiota transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to that using fresh material for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA.

Using frozen rather than fresh fecal material offers many advantages, such as allowing much more widespread and immediate accessibility of the treatment; reducing the number and frequency of donor screenings, which in turn would reduce costs; and ameliorating concern about potential transmission of pathogens from the donor to the recipient, since samples could be stored in quarantine until screening results are known, said Dr. Christine H. Lee of the department of pathology and molecular medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton (Ont.), and her associates.

They performed a 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial at six academic medical centers in Canada to compare frozen with fresh donor material in 232 adults with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. These study participants had “an extensive burden of comorbidity”: most had inflammatory bowel diseases and approximately 85% were immunocompromised, having undergone chronic hemodialysis or kidney transplantation, or having had metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. Half of the study subjects were inpatients, and approximately 75% were aged 65 years and older.

The patients were assigned to receive 50 mL of frozen-then-thawed FMT (114 participants) or fresh FMT (118 participants) by retention enema, delivered using 60-mL syringes. Those who didn’t improve by day 4 were given an additional FMT from the same donor. “Administration by enema is significantly less invasive than colonoscopy or nasojejunal/gastric administration and can be performed outside an acute care facility,” Dr. Lee and her associates noted.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical resolution, defined as no recurrence of C. difficile–related diarrhea at 13 weeks and no need for antibiotics. In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved this endpoint. In the intention-to-treat population, 75.0% of the frozen FMT group and 70.3% of the fresh FMT group achieved it. Both results demonstrate the noninferiority of frozen FMT, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:142-9. doi:10.1001/jama.201518098).

The proportion of adverse events and severe adverse events was deemed low and did not differ between the two study groups. The most common adverse events that may possibly have been related to treatment occurred in similar numbers of each group and included transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea during the first 24 hours after transplantation and constipation and excess flatulence during the 13-week follow-up.

Even though this follow-up was longer than that in most clinical trials of FMT for C. difficile infection, which only tracked patients for 40 days, it is still insufficient to assess the long-term safety of the treatment. Ten-year follow-up of the participants in this trial is currently under way to examine any beneficial effects the treatment might exert on the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or autoimmune disease, as well as any negative effects such as the development of autoimmune disorders or cancer.

The findings of Dr. Lee and her associates offer the best evidence to date supporting the use of frozen stool material in FMT, which would eliminate many of the logistical burdens associated with the treatment. For example, stool collection and processing would no longer have to be tied to the date and time of each individual transplantation.

These results also support the use of centralized stool banks, which would offer clinicians access to safe, screened stool material that could be shipped and stored frozen, then thawed for use as needed.

Dr. Preeti N. Malani and Dr. Krishna Rao are with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. Dr. Malani is also an associate editor at JAMA and Dr. Rao is also with the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Rao’s work is supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Malani and Dr. Rao reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:137-8) accompanying Dr. Lee’s report.

The findings of Dr. Lee and her associates offer the best evidence to date supporting the use of frozen stool material in FMT, which would eliminate many of the logistical burdens associated with the treatment. For example, stool collection and processing would no longer have to be tied to the date and time of each individual transplantation.

These results also support the use of centralized stool banks, which would offer clinicians access to safe, screened stool material that could be shipped and stored frozen, then thawed for use as needed.

Dr. Preeti N. Malani and Dr. Krishna Rao are with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. Dr. Malani is also an associate editor at JAMA and Dr. Rao is also with the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Rao’s work is supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Malani and Dr. Rao reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:137-8) accompanying Dr. Lee’s report.

The findings of Dr. Lee and her associates offer the best evidence to date supporting the use of frozen stool material in FMT, which would eliminate many of the logistical burdens associated with the treatment. For example, stool collection and processing would no longer have to be tied to the date and time of each individual transplantation.

These results also support the use of centralized stool banks, which would offer clinicians access to safe, screened stool material that could be shipped and stored frozen, then thawed for use as needed.

Dr. Preeti N. Malani and Dr. Krishna Rao are with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. Dr. Malani is also an associate editor at JAMA and Dr. Rao is also with the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Rao’s work is supported in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Malani and Dr. Rao reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:137-8) accompanying Dr. Lee’s report.

Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to that using fresh material for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA.

Using frozen rather than fresh fecal material offers many advantages, such as allowing much more widespread and immediate accessibility of the treatment; reducing the number and frequency of donor screenings, which in turn would reduce costs; and ameliorating concern about potential transmission of pathogens from the donor to the recipient, since samples could be stored in quarantine until screening results are known, said Dr. Christine H. Lee of the department of pathology and molecular medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton (Ont.), and her associates.

They performed a 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial at six academic medical centers in Canada to compare frozen with fresh donor material in 232 adults with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. These study participants had “an extensive burden of comorbidity”: most had inflammatory bowel diseases and approximately 85% were immunocompromised, having undergone chronic hemodialysis or kidney transplantation, or having had metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. Half of the study subjects were inpatients, and approximately 75% were aged 65 years and older.

The patients were assigned to receive 50 mL of frozen-then-thawed FMT (114 participants) or fresh FMT (118 participants) by retention enema, delivered using 60-mL syringes. Those who didn’t improve by day 4 were given an additional FMT from the same donor. “Administration by enema is significantly less invasive than colonoscopy or nasojejunal/gastric administration and can be performed outside an acute care facility,” Dr. Lee and her associates noted.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical resolution, defined as no recurrence of C. difficile–related diarrhea at 13 weeks and no need for antibiotics. In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved this endpoint. In the intention-to-treat population, 75.0% of the frozen FMT group and 70.3% of the fresh FMT group achieved it. Both results demonstrate the noninferiority of frozen FMT, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:142-9. doi:10.1001/jama.201518098).

The proportion of adverse events and severe adverse events was deemed low and did not differ between the two study groups. The most common adverse events that may possibly have been related to treatment occurred in similar numbers of each group and included transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea during the first 24 hours after transplantation and constipation and excess flatulence during the 13-week follow-up.

Even though this follow-up was longer than that in most clinical trials of FMT for C. difficile infection, which only tracked patients for 40 days, it is still insufficient to assess the long-term safety of the treatment. Ten-year follow-up of the participants in this trial is currently under way to examine any beneficial effects the treatment might exert on the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or autoimmune disease, as well as any negative effects such as the development of autoimmune disorders or cancer.

Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to that using fresh material for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA.

Using frozen rather than fresh fecal material offers many advantages, such as allowing much more widespread and immediate accessibility of the treatment; reducing the number and frequency of donor screenings, which in turn would reduce costs; and ameliorating concern about potential transmission of pathogens from the donor to the recipient, since samples could be stored in quarantine until screening results are known, said Dr. Christine H. Lee of the department of pathology and molecular medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton (Ont.), and her associates.

They performed a 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial at six academic medical centers in Canada to compare frozen with fresh donor material in 232 adults with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. These study participants had “an extensive burden of comorbidity”: most had inflammatory bowel diseases and approximately 85% were immunocompromised, having undergone chronic hemodialysis or kidney transplantation, or having had metastatic solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. Half of the study subjects were inpatients, and approximately 75% were aged 65 years and older.

The patients were assigned to receive 50 mL of frozen-then-thawed FMT (114 participants) or fresh FMT (118 participants) by retention enema, delivered using 60-mL syringes. Those who didn’t improve by day 4 were given an additional FMT from the same donor. “Administration by enema is significantly less invasive than colonoscopy or nasojejunal/gastric administration and can be performed outside an acute care facility,” Dr. Lee and her associates noted.

The primary efficacy endpoint was clinical resolution, defined as no recurrence of C. difficile–related diarrhea at 13 weeks and no need for antibiotics. In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved this endpoint. In the intention-to-treat population, 75.0% of the frozen FMT group and 70.3% of the fresh FMT group achieved it. Both results demonstrate the noninferiority of frozen FMT, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016;315[2]:142-9. doi:10.1001/jama.201518098).

The proportion of adverse events and severe adverse events was deemed low and did not differ between the two study groups. The most common adverse events that may possibly have been related to treatment occurred in similar numbers of each group and included transient diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea during the first 24 hours after transplantation and constipation and excess flatulence during the 13-week follow-up.

Even though this follow-up was longer than that in most clinical trials of FMT for C. difficile infection, which only tracked patients for 40 days, it is still insufficient to assess the long-term safety of the treatment. Ten-year follow-up of the participants in this trial is currently under way to examine any beneficial effects the treatment might exert on the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or autoimmune disease, as well as any negative effects such as the development of autoimmune disorders or cancer.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Fecal microbiota transplantation using frozen-then-thawed fecal material proved noninferior to using fresh material for recurrent/refractory Clostridium difficile infection.

Major finding: In the per-protocol population, 83.5% of the frozen FMT group and 85.1% of the fresh FMT group achieved clinical resolution.

Data source: A 2-year randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial involving 232 patients treated at six academic medical centers in Canada and followed for 13 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Physicians Services Inc., the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council, the National Science Foundation, and the gastrointestinal diseases research unit at Kingston (Ont.) General Hospital. Dr. Lee reported participating in clinical trials for ViroPharma, Actelion, Cubist, and Merck, and serving on the advisory boards of Rebiotix and Merck. Her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

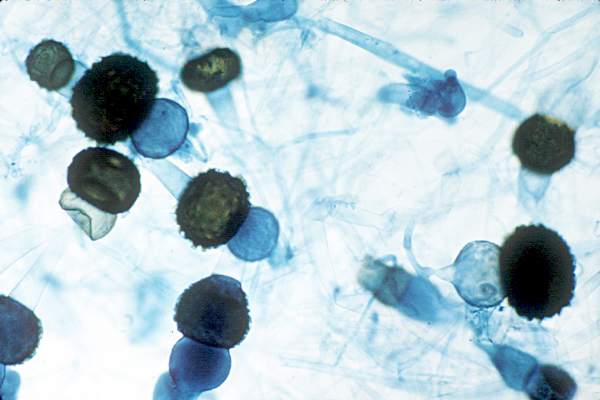

Hong Kong zygomycosis deaths pinned to dirty hospital laundry

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,

Major finding: Of 195 environmental samples at the contaminated laundry, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples.

Data source: Epidemiological study in Hong Kong.

Disclosures: Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors do not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Patients may safely self-administer long-term IV antibiotics

Uninsured patients can be trained to safely and efficiently self-administer long-term intravenous antibiotics, according to a 4-year outcomes study published in PLOS Medicine.

Between 2010 and 2013, 994 uninsured patients at Parkland Hospital in Dallas were enrolled in a self-administered outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (S-OPAT) program, and 224 insured patients were discharged to a health care–administered OPAT program. Patients in the S-OPAT group were trained to self-administer intravenous antimicrobials, tested for their ability to treat themselves before discharge, and then monitored by weekly visits to the S-OPAT outpatient clinic. The 224 insured patients in the H-OPAT program had antibiotics administered by a health care worker.

A research team led by Dr. Kavita Bhavan of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, estimated the effect of S-OPAT versus H-OPAT on 30-day all-cause readmission and 1-year all-cause mortality after controlling for selection bias with a propensity score developed using baseline clinical and sociodemographic information collected from the patients.

The 30-day readmission rate was 47% lower in the S-OPAT group than in the H-OPAT group, and the 1-year mortality rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. Because the S-OPAT program resulted in patients spending fewer days having inpatient infusions, 27,666 inpatient days were avoided over the study period.

Thus, S-OPAT was associated with similar or better outcomes than H-OPAT, meaning S-OPAT may be an acceptable model of treatment for uninsured, medically stable patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antimicrobials at home.

Read the full study online at PLOS Medicine (PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 15;12[12]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001922).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Uninsured patients can be trained to safely and efficiently self-administer long-term intravenous antibiotics, according to a 4-year outcomes study published in PLOS Medicine.

Between 2010 and 2013, 994 uninsured patients at Parkland Hospital in Dallas were enrolled in a self-administered outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (S-OPAT) program, and 224 insured patients were discharged to a health care–administered OPAT program. Patients in the S-OPAT group were trained to self-administer intravenous antimicrobials, tested for their ability to treat themselves before discharge, and then monitored by weekly visits to the S-OPAT outpatient clinic. The 224 insured patients in the H-OPAT program had antibiotics administered by a health care worker.

A research team led by Dr. Kavita Bhavan of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, estimated the effect of S-OPAT versus H-OPAT on 30-day all-cause readmission and 1-year all-cause mortality after controlling for selection bias with a propensity score developed using baseline clinical and sociodemographic information collected from the patients.

The 30-day readmission rate was 47% lower in the S-OPAT group than in the H-OPAT group, and the 1-year mortality rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. Because the S-OPAT program resulted in patients spending fewer days having inpatient infusions, 27,666 inpatient days were avoided over the study period.

Thus, S-OPAT was associated with similar or better outcomes than H-OPAT, meaning S-OPAT may be an acceptable model of treatment for uninsured, medically stable patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antimicrobials at home.

Read the full study online at PLOS Medicine (PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 15;12[12]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001922).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Uninsured patients can be trained to safely and efficiently self-administer long-term intravenous antibiotics, according to a 4-year outcomes study published in PLOS Medicine.

Between 2010 and 2013, 994 uninsured patients at Parkland Hospital in Dallas were enrolled in a self-administered outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (S-OPAT) program, and 224 insured patients were discharged to a health care–administered OPAT program. Patients in the S-OPAT group were trained to self-administer intravenous antimicrobials, tested for their ability to treat themselves before discharge, and then monitored by weekly visits to the S-OPAT outpatient clinic. The 224 insured patients in the H-OPAT program had antibiotics administered by a health care worker.

A research team led by Dr. Kavita Bhavan of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, estimated the effect of S-OPAT versus H-OPAT on 30-day all-cause readmission and 1-year all-cause mortality after controlling for selection bias with a propensity score developed using baseline clinical and sociodemographic information collected from the patients.

The 30-day readmission rate was 47% lower in the S-OPAT group than in the H-OPAT group, and the 1-year mortality rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. Because the S-OPAT program resulted in patients spending fewer days having inpatient infusions, 27,666 inpatient days were avoided over the study period.

Thus, S-OPAT was associated with similar or better outcomes than H-OPAT, meaning S-OPAT may be an acceptable model of treatment for uninsured, medically stable patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antimicrobials at home.

Read the full study online at PLOS Medicine (PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 15;12[12]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001922).

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Hospital-acquired pneumonia threatens cervical spinal cord injury patients

SAN DIEGO – The overall rate of hospital-acquired pneumonia following cervical spinal cord injury is about 20%, results from a study of national data demonstrated.

“Cervical spinal cord injury patients are at an increased risk for the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia,” lead study author Dr. Pablo J. Diaz-Collado said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society.

“Complete cord injuries, longer length of stay, ICU stay and ventilation time lead to significantly increased risk of HAP, which then leads to poor inpatient outcomes,” he said. “It is of crucial importance to keep these risk factors in mind when treating patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. There is a need to optimize the management protocols for these patients to help prevent the development of HAPs.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado, an orthopedic surgery resident at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, and his associates identified 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) to analyze risk factors for the development of HAP and inpatient outcomes in this population. They used multivariate logistic regression to identify independent associations of various risk factors with the occurrence of HAP.

The researchers found that the overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%, which amounted to 1,065 patients. Factors independently associated with HAP were complete spinal cord injuries (compared to central cord injuries; OR 1.44; P = .009); longer inpatient length of stay (OR 3.08 for a stay that lasted 7-13 days, OR 10.21 for 21-27 days, and OR 14.89 for 35 days or more; P = .001 or less for all associations); longer ICU stay (OR 2.86 for a stay that lasted 9-11 days, OR 3.05 for 12-14 days, and OR 2.94 for 15 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations), and longer time on mechanical ventilation (OR 2.68 for ventilation that lasted 3-6 days, OR 3.76 for 7-13 days, OR 3.98 for 14-20 days, and OR 3.99 for 21 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations).

After the researchers controlled for all other risk factors, including patient comorbidities, Injury Severity Score, and other inpatient complications, HAP was associated with increased odds of death (OR 1.60; P = .005), inpatient adverse events (OR 1.65; P less than .001), discharge to an extended-care facility (OR 1.93; P = .001), and longer length of stay (a mean of an additional 10.93 days; P less than .001).

Dr. Diaz-Collado acknowledged that the study is “limited by the quality of the data entry. In addition, the database does not include classifications of fractures, and thus stratification of the analysis in terms of the different kinds of fractures in the cervical spine is not possible. Finally, procedural codes are less accurate and thus including whether or not patients underwent a surgical intervention is less reliable.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The overall rate of hospital-acquired pneumonia following cervical spinal cord injury is about 20%, results from a study of national data demonstrated.

“Cervical spinal cord injury patients are at an increased risk for the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia,” lead study author Dr. Pablo J. Diaz-Collado said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society.

“Complete cord injuries, longer length of stay, ICU stay and ventilation time lead to significantly increased risk of HAP, which then leads to poor inpatient outcomes,” he said. “It is of crucial importance to keep these risk factors in mind when treating patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. There is a need to optimize the management protocols for these patients to help prevent the development of HAPs.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado, an orthopedic surgery resident at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, and his associates identified 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) to analyze risk factors for the development of HAP and inpatient outcomes in this population. They used multivariate logistic regression to identify independent associations of various risk factors with the occurrence of HAP.

The researchers found that the overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%, which amounted to 1,065 patients. Factors independently associated with HAP were complete spinal cord injuries (compared to central cord injuries; OR 1.44; P = .009); longer inpatient length of stay (OR 3.08 for a stay that lasted 7-13 days, OR 10.21 for 21-27 days, and OR 14.89 for 35 days or more; P = .001 or less for all associations); longer ICU stay (OR 2.86 for a stay that lasted 9-11 days, OR 3.05 for 12-14 days, and OR 2.94 for 15 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations), and longer time on mechanical ventilation (OR 2.68 for ventilation that lasted 3-6 days, OR 3.76 for 7-13 days, OR 3.98 for 14-20 days, and OR 3.99 for 21 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations).

After the researchers controlled for all other risk factors, including patient comorbidities, Injury Severity Score, and other inpatient complications, HAP was associated with increased odds of death (OR 1.60; P = .005), inpatient adverse events (OR 1.65; P less than .001), discharge to an extended-care facility (OR 1.93; P = .001), and longer length of stay (a mean of an additional 10.93 days; P less than .001).

Dr. Diaz-Collado acknowledged that the study is “limited by the quality of the data entry. In addition, the database does not include classifications of fractures, and thus stratification of the analysis in terms of the different kinds of fractures in the cervical spine is not possible. Finally, procedural codes are less accurate and thus including whether or not patients underwent a surgical intervention is less reliable.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The overall rate of hospital-acquired pneumonia following cervical spinal cord injury is about 20%, results from a study of national data demonstrated.

“Cervical spinal cord injury patients are at an increased risk for the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia,” lead study author Dr. Pablo J. Diaz-Collado said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society.

“Complete cord injuries, longer length of stay, ICU stay and ventilation time lead to significantly increased risk of HAP, which then leads to poor inpatient outcomes,” he said. “It is of crucial importance to keep these risk factors in mind when treating patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. There is a need to optimize the management protocols for these patients to help prevent the development of HAPs.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado, an orthopedic surgery resident at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, and his associates identified 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) to analyze risk factors for the development of HAP and inpatient outcomes in this population. They used multivariate logistic regression to identify independent associations of various risk factors with the occurrence of HAP.

The researchers found that the overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%, which amounted to 1,065 patients. Factors independently associated with HAP were complete spinal cord injuries (compared to central cord injuries; OR 1.44; P = .009); longer inpatient length of stay (OR 3.08 for a stay that lasted 7-13 days, OR 10.21 for 21-27 days, and OR 14.89 for 35 days or more; P = .001 or less for all associations); longer ICU stay (OR 2.86 for a stay that lasted 9-11 days, OR 3.05 for 12-14 days, and OR 2.94 for 15 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations), and longer time on mechanical ventilation (OR 2.68 for ventilation that lasted 3-6 days, OR 3.76 for 7-13 days, OR 3.98 for 14-20 days, and OR 3.99 for 21 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations).

After the researchers controlled for all other risk factors, including patient comorbidities, Injury Severity Score, and other inpatient complications, HAP was associated with increased odds of death (OR 1.60; P = .005), inpatient adverse events (OR 1.65; P less than .001), discharge to an extended-care facility (OR 1.93; P = .001), and longer length of stay (a mean of an additional 10.93 days; P less than .001).

Dr. Diaz-Collado acknowledged that the study is “limited by the quality of the data entry. In addition, the database does not include classifications of fractures, and thus stratification of the analysis in terms of the different kinds of fractures in the cervical spine is not possible. Finally, procedural codes are less accurate and thus including whether or not patients underwent a surgical intervention is less reliable.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

AT CSRS 2015

Key clinical point: About one in five cervical spinal cord injury patients develop hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Major finding: The overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%.

Data source: A study of 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank.

Disclosures: Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

Tricks for treating C. diff in IBD

ORLANDO – You can confidently treat mild to severe Clostridium difficile infection in persons with inflammatory bowel disease, without disrupting their immunosuppression or other treatments, according to an expert.

“If your patient with IBD needs a fecal transplant for C. diff., you should not be concerned about withholding it,” Dr. Alan C. Moss said during a basic science presentation at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Moss is an associate professor of medicine and the director of translational research at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The first step, after you’ve determined that your patient has a true C. diff. infection, as opposed to having only been colonized by the bacteria, is choosing the best antibiotic. “Unfortunately, almost all IBD patients are excluded from controlled trials of antibiotics in C. diff. infection, so all we really have to go on are retrospective cohort data,” said Dr. Moss.

One such study, uncontrolled for disease severity, showed that a third of 114 inpatients with IBD who had a co-occurring C. diff. infection had higher 30-day readmission rates when treated first with metronidazole, per current standards of care, compared with the remaining two-thirds of patients who were treated first with vancomycin. The metronidazole group also averaged double the length of stays of the vancomycin group (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Sep;58:5054-9 [doi: 10.1128/AAC.02606-13]).

“This suggests that in IBD patients, especially for those who meet criteria for a severe C. diff. infection, vancomycin is the way to go,” Dr. Moss said, noting a trend of metronidazole for mild infections in this cohort having ever less efficacy.

Beyond mild infection, Dr. Moss said the first line of treatment should be vancomycin 125 mg four times daily, or 500 mg four times daily if it is complicated disease.

If your patient has recurrent C. diff. infection, Dr. Moss recommended a prolonged taper of vancomycin, but to be vigilant about it being truly an infection and not a flare-up of colonized bacteria.

“My bar for doing fecal transplant in these patients has dropped considerably in the last few years, because if you really want to squeeze out the niche that C. diff. occupies in the microbiome, fecal transplant is really the most effective way we have of doing that,” Dr. Moss said.

While there is a division in the field over whether to continue immunosuppression during antibiotic treatment, Dr. Moss cited a small study indicating that if a patient were on two or more immunosuppressants, they had a higher risk of death, megacolon, or shock during C. diff. treatment. “I think it’s hard to draw many conclusions from that,” Dr. Moss said. “It may just be a surrogate marker of severity of disease rather than infection, per se.”

The standard of care for recurrent and refractory C. diff. infection is now fecal transplant, according to Dr. Moss. A recent study of fecal transplantation showed an 89% cure rate of C. diff. infection after a single fecal transplant in IBD patients. Of the 36 IBD patients in the study, half of whom were on biologic and immunosuppressive therapies, four experienced disease flare-ups (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;109:1065-71 [doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.133]. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368:474-5 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1214816]).