User login

Fracture risk linked to mortality in women with myeloma

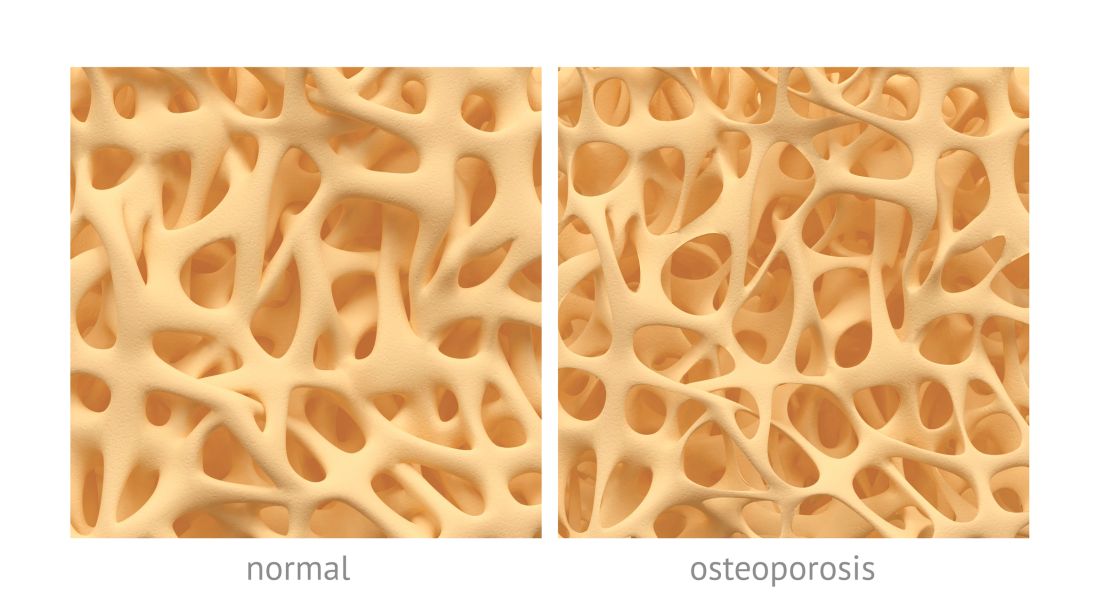

Preexisting osteoporosis is an important risk factor for mortality risk in cancer-free postmenopausal women who go on to develop multiple myeloma, results of a recent analysis suggest.

High fracture risk was associated with an increased risk of death, independent of other clinical risk factors, in this analysis of postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) data set.

The findings help define osteoporosis as an important prognostic factor associated with mortality in postmenopausal women who develop myeloma, according to study author Ashley E. Rosko, MD, of Ohio State University, Columbus, and her colleagues.

“Osteoporosis is highly prevalent in aging adults, and very little is known on how this comorbid condition contributes to outcomes in individuals who develop myeloma,” wrote Dr. Rosko and her coauthors. Their report is in the journal Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

The analysis involved 362 women in the WHI data set who developed myeloma and had no history of any cancer at baseline. Women in the WHI were between 50 and 79 years of age and postmenopausal at baseline when originally recruited at 40 U.S. centers between 1993 and 1998.

Dr. Rosko and her colleagues calculated bone health for women in the data set using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), a web-based tool that calculates 10-year probability of hip and other major osteoporotic fractures.

Of the 362 women who developed myeloma, 98 were classified as having high FRAX scores, defined as a 10-year probability of 3% or greater for hip fracture, or 20% or greater for other major osteoporosis-related fractures.

With a median follow-up of 10.5 years, the adjusted risk of death was elevated in women with high FRAX scores, according to investigators, with a covariate-adjusted hazard ratio of 1.51 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.25; P = .044) versus women with low FRAX scores.

Of the 362 patients who developed myeloma, 226 died during the follow-up period. That included 71 women with high FRAX scores, or 72% of that subset; and 155 women with low FRAX scores, or 59% of that subset, investigators reported.

These findings suggest osteoporosis is an “important comorbidity” in women who develop multiple myeloma, Dr. Rosko and her coauthors said in a discussion of the study results.

“Recognizing osteoporosis as a risk factor associated with multiple myeloma mortality is an important prognostic factor in postmenopausal women,” they said.

This investigation was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rosko AE et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Sep;18(9):597-602.e1.

Preexisting osteoporosis is an important risk factor for mortality risk in cancer-free postmenopausal women who go on to develop multiple myeloma, results of a recent analysis suggest.

High fracture risk was associated with an increased risk of death, independent of other clinical risk factors, in this analysis of postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) data set.

The findings help define osteoporosis as an important prognostic factor associated with mortality in postmenopausal women who develop myeloma, according to study author Ashley E. Rosko, MD, of Ohio State University, Columbus, and her colleagues.

“Osteoporosis is highly prevalent in aging adults, and very little is known on how this comorbid condition contributes to outcomes in individuals who develop myeloma,” wrote Dr. Rosko and her coauthors. Their report is in the journal Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

The analysis involved 362 women in the WHI data set who developed myeloma and had no history of any cancer at baseline. Women in the WHI were between 50 and 79 years of age and postmenopausal at baseline when originally recruited at 40 U.S. centers between 1993 and 1998.

Dr. Rosko and her colleagues calculated bone health for women in the data set using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), a web-based tool that calculates 10-year probability of hip and other major osteoporotic fractures.

Of the 362 women who developed myeloma, 98 were classified as having high FRAX scores, defined as a 10-year probability of 3% or greater for hip fracture, or 20% or greater for other major osteoporosis-related fractures.

With a median follow-up of 10.5 years, the adjusted risk of death was elevated in women with high FRAX scores, according to investigators, with a covariate-adjusted hazard ratio of 1.51 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.25; P = .044) versus women with low FRAX scores.

Of the 362 patients who developed myeloma, 226 died during the follow-up period. That included 71 women with high FRAX scores, or 72% of that subset; and 155 women with low FRAX scores, or 59% of that subset, investigators reported.

These findings suggest osteoporosis is an “important comorbidity” in women who develop multiple myeloma, Dr. Rosko and her coauthors said in a discussion of the study results.

“Recognizing osteoporosis as a risk factor associated with multiple myeloma mortality is an important prognostic factor in postmenopausal women,” they said.

This investigation was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rosko AE et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Sep;18(9):597-602.e1.

Preexisting osteoporosis is an important risk factor for mortality risk in cancer-free postmenopausal women who go on to develop multiple myeloma, results of a recent analysis suggest.

High fracture risk was associated with an increased risk of death, independent of other clinical risk factors, in this analysis of postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) data set.

The findings help define osteoporosis as an important prognostic factor associated with mortality in postmenopausal women who develop myeloma, according to study author Ashley E. Rosko, MD, of Ohio State University, Columbus, and her colleagues.

“Osteoporosis is highly prevalent in aging adults, and very little is known on how this comorbid condition contributes to outcomes in individuals who develop myeloma,” wrote Dr. Rosko and her coauthors. Their report is in the journal Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

The analysis involved 362 women in the WHI data set who developed myeloma and had no history of any cancer at baseline. Women in the WHI were between 50 and 79 years of age and postmenopausal at baseline when originally recruited at 40 U.S. centers between 1993 and 1998.

Dr. Rosko and her colleagues calculated bone health for women in the data set using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), a web-based tool that calculates 10-year probability of hip and other major osteoporotic fractures.

Of the 362 women who developed myeloma, 98 were classified as having high FRAX scores, defined as a 10-year probability of 3% or greater for hip fracture, or 20% or greater for other major osteoporosis-related fractures.

With a median follow-up of 10.5 years, the adjusted risk of death was elevated in women with high FRAX scores, according to investigators, with a covariate-adjusted hazard ratio of 1.51 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.25; P = .044) versus women with low FRAX scores.

Of the 362 patients who developed myeloma, 226 died during the follow-up period. That included 71 women with high FRAX scores, or 72% of that subset; and 155 women with low FRAX scores, or 59% of that subset, investigators reported.

These findings suggest osteoporosis is an “important comorbidity” in women who develop multiple myeloma, Dr. Rosko and her coauthors said in a discussion of the study results.

“Recognizing osteoporosis as a risk factor associated with multiple myeloma mortality is an important prognostic factor in postmenopausal women,” they said.

This investigation was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rosko AE et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Sep;18(9):597-602.e1.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA AND LEUKEMIA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk of death was elevated in women at high risk of fracture (covariate-adjusted hazard ratio, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.25; P = .044) versus women with low fracture risk.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative data set including 362 postmenopausal women who were cancer free at baseline and developed myeloma over the course of study follow-up.

Disclosures: The analysis was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Rosko AE et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Sep;18(9):597-602.e1.

Could An Antibiotic Be the Next Great Oncologic Drug?

An antibiotic drug used to treat acne, among other things, may turn out to have potential well beyond that. Researchers from University of Antioquiain Medellin, Colombia, suggest that minocycline could be a promising antileukemic drug.

Minocycline is a well-established tetracycline derivative, used clinically since 1971, with a safe track record. But it also has nonantibiotic properties, exerting both antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects. There is even “compelling” preclinical evidence, the researchers say, that minocycline induces apoptosis in an acute myeloid leukemia cell line and a chronic myeloid leukemia cell line. Would the same be true of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells? To test their hypothesis, the researchers examined minocycline’s mechanism of action in the Jurkat cell line, an ALL tumor line established in the 1970s from the peripheral blood of a 14-year-old boy.

The researchers found that minocycline did in fact induce apoptosis in Jurkat cells through a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-mediated signaling pathway. Indeed, they add, H2O2 triggers a whole cascade of adverse effects, including up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins. The researchers suggest that minocycline might even be capable of generating H2O2, which could explain the cytotoxic effects not only of minocycline, but of other tetracycline analogues. “Interestingly,” the researchers say, minocycline did all that without inducing oxidative stress or apoptosis makers in human peripheral blood lymphocyte cells.

The significance of their study is twofold, the researchers say: First, that minocycline is a safe and specific apoptosis-inducing drug against Jurkat cells in vitro; second, that it is pharmacologically well characterized and widely available.

The researchers note that no information is available on whether minocycline might efficiently kill ALL cells in vivo. However, they also note that minocycline has been found to be safe and well tolerated in doses up to 10 mg/kg in stroke patients—a dose that could be a sufficient concentration to reduce the viability of leukemia cell lines.

Source:

Ruiz-Moreno C, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M. Toxicol In Vitro. 2018;50:336-346.

doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.03.012

An antibiotic drug used to treat acne, among other things, may turn out to have potential well beyond that. Researchers from University of Antioquiain Medellin, Colombia, suggest that minocycline could be a promising antileukemic drug.

Minocycline is a well-established tetracycline derivative, used clinically since 1971, with a safe track record. But it also has nonantibiotic properties, exerting both antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects. There is even “compelling” preclinical evidence, the researchers say, that minocycline induces apoptosis in an acute myeloid leukemia cell line and a chronic myeloid leukemia cell line. Would the same be true of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells? To test their hypothesis, the researchers examined minocycline’s mechanism of action in the Jurkat cell line, an ALL tumor line established in the 1970s from the peripheral blood of a 14-year-old boy.

The researchers found that minocycline did in fact induce apoptosis in Jurkat cells through a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-mediated signaling pathway. Indeed, they add, H2O2 triggers a whole cascade of adverse effects, including up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins. The researchers suggest that minocycline might even be capable of generating H2O2, which could explain the cytotoxic effects not only of minocycline, but of other tetracycline analogues. “Interestingly,” the researchers say, minocycline did all that without inducing oxidative stress or apoptosis makers in human peripheral blood lymphocyte cells.

The significance of their study is twofold, the researchers say: First, that minocycline is a safe and specific apoptosis-inducing drug against Jurkat cells in vitro; second, that it is pharmacologically well characterized and widely available.

The researchers note that no information is available on whether minocycline might efficiently kill ALL cells in vivo. However, they also note that minocycline has been found to be safe and well tolerated in doses up to 10 mg/kg in stroke patients—a dose that could be a sufficient concentration to reduce the viability of leukemia cell lines.

Source:

Ruiz-Moreno C, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M. Toxicol In Vitro. 2018;50:336-346.

doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.03.012

An antibiotic drug used to treat acne, among other things, may turn out to have potential well beyond that. Researchers from University of Antioquiain Medellin, Colombia, suggest that minocycline could be a promising antileukemic drug.

Minocycline is a well-established tetracycline derivative, used clinically since 1971, with a safe track record. But it also has nonantibiotic properties, exerting both antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects. There is even “compelling” preclinical evidence, the researchers say, that minocycline induces apoptosis in an acute myeloid leukemia cell line and a chronic myeloid leukemia cell line. Would the same be true of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells? To test their hypothesis, the researchers examined minocycline’s mechanism of action in the Jurkat cell line, an ALL tumor line established in the 1970s from the peripheral blood of a 14-year-old boy.

The researchers found that minocycline did in fact induce apoptosis in Jurkat cells through a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-mediated signaling pathway. Indeed, they add, H2O2 triggers a whole cascade of adverse effects, including up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins. The researchers suggest that minocycline might even be capable of generating H2O2, which could explain the cytotoxic effects not only of minocycline, but of other tetracycline analogues. “Interestingly,” the researchers say, minocycline did all that without inducing oxidative stress or apoptosis makers in human peripheral blood lymphocyte cells.

The significance of their study is twofold, the researchers say: First, that minocycline is a safe and specific apoptosis-inducing drug against Jurkat cells in vitro; second, that it is pharmacologically well characterized and widely available.

The researchers note that no information is available on whether minocycline might efficiently kill ALL cells in vivo. However, they also note that minocycline has been found to be safe and well tolerated in doses up to 10 mg/kg in stroke patients—a dose that could be a sufficient concentration to reduce the viability of leukemia cell lines.

Source:

Ruiz-Moreno C, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M. Toxicol In Vitro. 2018;50:336-346.

doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.03.012

Phase 1 CAR T trial for NHL launches in Cleveland

University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center in Cleveland has launched a phase 1 clinical trial to study the safety of CAR T therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The trial will enroll 12-15 adult patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who have not responded to standard therapies, according to a statement from University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center.

The principal investigator for the trial will be Paolo Caimi, MD, of UH Seidman and Case Western Reserve University.

UH Seidman, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University, is one of a handful of centers that has the ability to manufacture the CAR T cells from the patient’s own genetically modified T cells on site in the shared Case Western Reserve University National Center for Regenerative Medicine and the UH Seidman Cellular Therapy Laboratory, saving time for patients.

“Having the ability to make cells on-site means there will be a shorter turnaround time in having the cells available for the patient, compared to shipping them off-site,” said Dr. Caimi in the press statement.

University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center in Cleveland has launched a phase 1 clinical trial to study the safety of CAR T therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The trial will enroll 12-15 adult patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who have not responded to standard therapies, according to a statement from University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center.

The principal investigator for the trial will be Paolo Caimi, MD, of UH Seidman and Case Western Reserve University.

UH Seidman, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University, is one of a handful of centers that has the ability to manufacture the CAR T cells from the patient’s own genetically modified T cells on site in the shared Case Western Reserve University National Center for Regenerative Medicine and the UH Seidman Cellular Therapy Laboratory, saving time for patients.

“Having the ability to make cells on-site means there will be a shorter turnaround time in having the cells available for the patient, compared to shipping them off-site,” said Dr. Caimi in the press statement.

University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center in Cleveland has launched a phase 1 clinical trial to study the safety of CAR T therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The trial will enroll 12-15 adult patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who have not responded to standard therapies, according to a statement from University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center.

The principal investigator for the trial will be Paolo Caimi, MD, of UH Seidman and Case Western Reserve University.

UH Seidman, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University, is one of a handful of centers that has the ability to manufacture the CAR T cells from the patient’s own genetically modified T cells on site in the shared Case Western Reserve University National Center for Regenerative Medicine and the UH Seidman Cellular Therapy Laboratory, saving time for patients.

“Having the ability to make cells on-site means there will be a shorter turnaround time in having the cells available for the patient, compared to shipping them off-site,” said Dr. Caimi in the press statement.

Key clinical point: A phase 1 trial of CAR T therapy is enrolling adult patients with NHL who have not responded to standard therapies.

Major finding: The trial site has the ability to manufacture the cells on site, saving patients time.

Study details: A phase 1 trial to evaluate safety.

Disclosures: The study will be funded by University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center.

Immunotherapies shape the treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is evolving faster than ever before, with a range of available therapeutic options that is now almost as diverse as this group of tumors. Immunotherapy in particular is front and center in the battle to control these diseases. Here, we describe the latest promising developments.

Exploiting T cells

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is diverse, but one particular type of therapy has led the charge in improving patient outcomes. Several features of hematologic malignancies may make them particularly amenable to immunotherapy, including the fact that they are derived from corrupt immune cells and come into constant contact with other immune cells within the hematopoietic environment in which they reside. One of the oldest forms of immunotherapy, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), remains the only curative option for many patients with hematologic malignancies.1,2

Given the central role of T lymphocytes in antitumor immunity, research efforts have focused on harnessing their activity for cancer treatment. One example of this is adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), in which T cells are collected from a patient, grown outside the body to increase their number and then reinfused back to the patient. Allogeneic HSCT, in which the stem cells are collected from a matching donor and transplanted into the patient, is a crude example of ACT. The graft-versus-tumor effect is driven by donor cells present in the transplant, but is limited by the development of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), whereby the donor T cells attack healthy host tissue.

Other types of ACT have been developed in an effort to capitalize on the anti-tumor effects of the patients own T cells and thus avoid the potentially fatal complication of GvHD. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy was developed to exploit the presence of tumor-specific T cells in the tumor microenvironment. To date, the efficacy of TIL therapy has been predominantly limited to melanoma.1,3,4

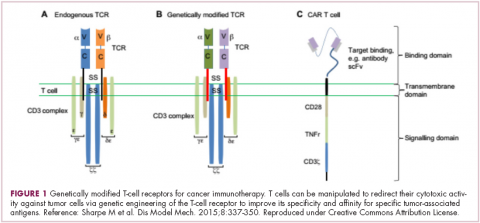

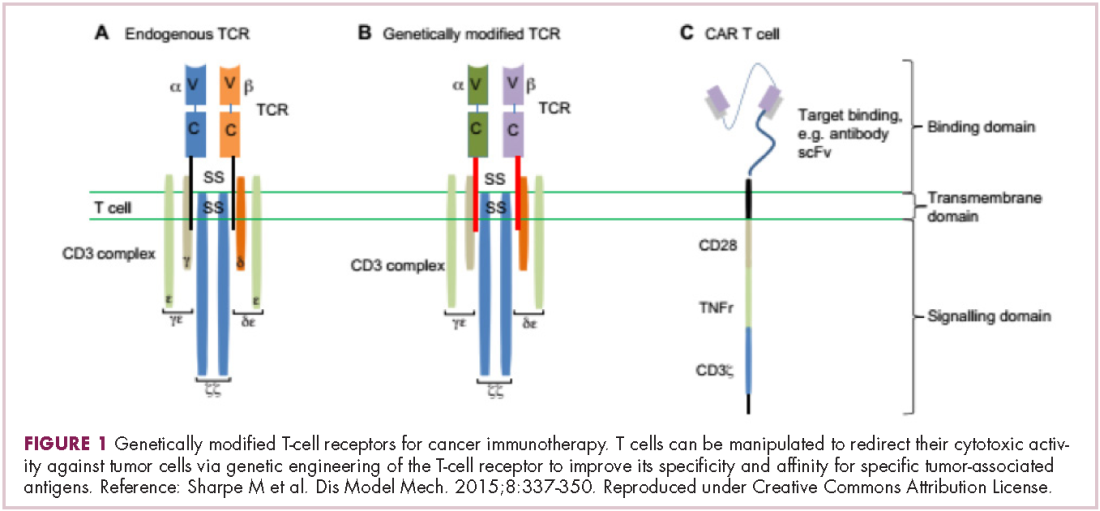

Most recently, there has been a substantial buzz around the idea of genetically engineering T cells before they are reintroduced into the patient, to increase their anti-tumor efficacy and minimize damage to healthy tissue. This is achieved either by manipulating the antigen binding portion of the T-cell receptor to alter its specificity (TCR T cells) or by generating artificial fusion receptors known as chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells; Figure 1). The former is limited by the need for the TCR to be genetically matched to the patient’s immune type, whereas the latter is more flexible in this regard and has proved most successful.

CARs are formed by fusing part of the single-chain variable fragment of a monoclonal antibody to part of the TCR and one or more costimulatory molecules. In this way, the T cell is guided to the tumor through antibody recognition of a particular tumor-associated antigen, whereupon its effector functions are activated by engagement of the TCR and costimulatory signal.5

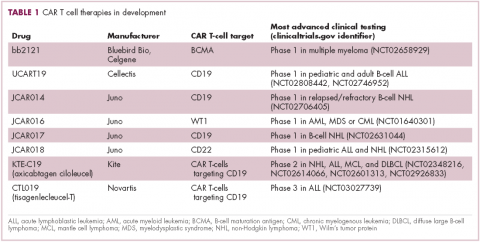

Headlining advancements with CAR T cells

CAR T cells directed against the CD19 antigen, found on the surface of many hematologic malignancies, are the most clinically advanced in this rapidly evolving field (Table 1). Durable remissions have been demonstrated in patients with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL), with efficacy in both the pre- and posttransplant setting and in patients with chemotherapy-refractory disease.4,5

CTL019, a CD19-targeted CAR-T cell therapy, also known as tisagenlecleucel-T, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL and, more recently, for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma.6

It is edging closer to FDA approval for the ALL indication, having been granted priority review in March on the basis of the phase 2 ELIANA trial, in which 50 patients received a single infusion of CTL019. Data presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016 showed that 82% of patients achieved either complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi) 3 months after treatment.7

Meanwhile, Kite Pharma has a rolling submission with the FDA for KTE-C19 (axicabtagene ciloleucel) for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell NHL who are ineligible for HSCT. In the ZUMA-1 trial, this therapy demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 71%.8 Juno Therapeutics is developing several CAR T-cell therapies, including JCAR017, which elicited CR in 60% of patients with relapsed/refractory NHL.9

Target antigens other than CD19 are being explored, but these are mostly in the early stages of clinical development. While the focus has predominantly been on the treatment of lymphoma and leukemia, a presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting in June reported the efficacy of a CAR-T cell therapy targeting the B-cell maturation antigen in patients with multiple myeloma. Results from 19 patients enrolled in an ongoing phase 1 trial in China showed that 14 had achieved stringent CR, 1 partial remission (PR) and 4 very good partial remission (VGPR).10

Antibodies evolve

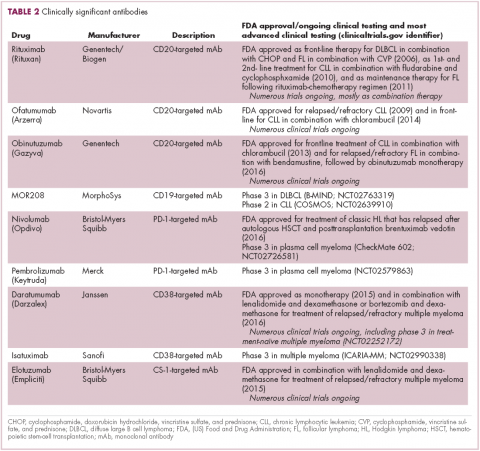

Another type of immunotherapy that has revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies is monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), targeting antigens on the surface of malignant B and T cells, in particular CD20. The approval of CD20-targeting mAb rituximab in 1997 was the first coup for the development of immunotherapy for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. It has become part of the standard treatment regimen for B-cell malignancies, including NHL and CLL, in combination with various types of chemotherapy.

Several other CD20-targeting antibodies have been developed (Table 2), some of which work in the same way as rituximab (eg, ofatumumab) and some that have a slightly different mechanism of action (eg, obinutuzumab).11 Both types of antibody have proved highly effective; ofatumumab is FDA approved for the treatment of advanced CLL and is being evaluated in phase 3 trials in other hematologic malignancies, while obinutuzumab has received regulatory approval for the first-line treatment of CLL, replacing the standard rituximab-containing regimen.12

The use of ofatumumab as maintenance therapy is supported by the results of the phase 3 PROLONG study in which 474 patients were randomly assigned to ofatumumab maintenance for 2 years or observation. Over a median follow-up of close to 20 months, ofatumumab-treated patients experienced improved progression-free survival (PFS; median PFS: 29.4 months vs 15.2 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.50; P < .0001).13 Obinutuzumab’s new indication is based on data from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial, in which the obinutuzumab arm showed improved 3-year PFS compared with rituximab.14Until recently, multiple myeloma had proven relatively resistant to mAb therapy, but two new drug targets have dramatically altered the treatment landscape for this type of hematologic malignancy. CD2 subset 1 (CS1), also known as signaling lymphocytic activation molecule 7 (SLAMF7), and CD38 are glycoproteins expressed highly and nearly uniformly on the surface of multiple myeloma cells and only at low levels on other lymphoid and myeloid cells.15

Several antibodies directed at these targets are in clinical development, but daratumumab and elotuzumab, targeting CD38 and CS1, respectively, are both newly approved by the FDA for relapsed/refractory disease, daratumumab as monotherapy and elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The indication for daratumumab was subsequently expanded to include its use in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone or bortezomib plus dexamethasone. Support for this new indication came from 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. In the CASTOR trial, the combination of daratumumab with bortezomib–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 61%, compared with bortezomib–dexamethasone alone, whereas daratumumab with lenalidomide–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 63% in the POLLUX trial.16,17

Numerous clinical trials for both drugs are ongoing, including in the front-line setting in multiple myeloma, as well as trials in other types of B-cell malignancy, and several other CD38-targeting mAbs are also in development, including isatuximab, which has reached the phase 3 stage (NCT02990338).

Innovative design

Newer drug designs, which have sought to take mAb therapy to the next level, have also shown significant efficacy in hematologic malignancies. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) combine the cytotoxic efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents with the specificity of a mAb targeting a tumor-specific antigen. This essentially creates a targeted payload that improves upon the efficacy of mAb monotherapy but mitigates some of the side effects of chemotherapy related to their indiscriminate killing of both cancerous and healthy cells.

The development of ADCs has been somewhat of a rollercoaster ride, with the approval and subsequent withdrawal of the first-in-class drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin in 2010, but the field was reinvigorated with the successful development of brentuximab vedotin, which targets the CD30 antigen and is approved for the treatment of multiple different hematologic malignancies, including, most recently, for posttransplant consolidation therapy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma at high risk of relapse or progression.18

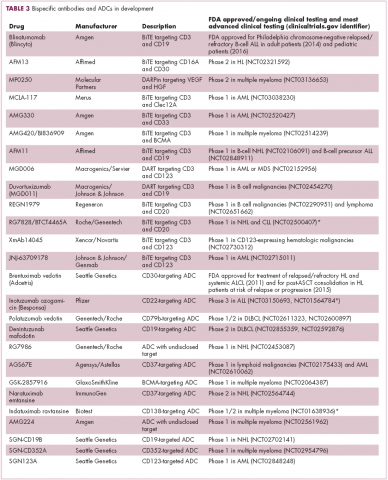

Brentuximab vedotin may soon be joined by another FDA-approved ADC, this one targeting CD22. Inotuzumab ozogamicin was recently granted priority review for the treatment of relapsed/refractory ALL. The FDA is reviewing data from the phase 3 INO-VATE study in which inotuzumab ozogamicin reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 55% compared with standard therapy, and a decision is expected by August.19 Other ADC targets being investigated in clinical trials include CD138, CD19, and CD33 (Table 3). Meanwhile, a meta-analysis of randomized trials suggested that the withdrawal of gemtuzumab ozogamicin may have been premature, indicating that it does improve long-term overall survival (OS) and reduces the risk of relapse.20

Bispecific antibodies that link natural killer (NK) cells to tumor cells, by targeting the NK-cell receptor CD16, known as BiKEs, are also in development in an attempt to harness the power of the innate immune response.

B-cell signaling a ripe target

Beyond immunotherapy, molecularly targeted drugs directed against key drivers of hematologic malignancies are also showing great promise. In particular, the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway, a central regulator of B-cell function, and its constituent kinases that are frequently dysregulated in B cell malignancies, has emerged as an exciting therapeutic avenue.

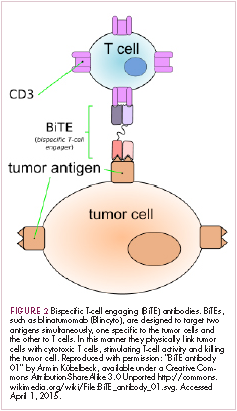

A variety of small molecule inhibitors targeting different nodes of the BCR pathway have been developed (Table 4), but the greatest success to date has been achieved with drugs targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK). Their clinical development culminated in the approval of ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma in 2013 and subsequently for patients with CLL, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and most recently for patients with marginal zone lymphoma.

More than 100 clinical trials of ibrutinib are ongoing in an effort to further clarify its role in a variety of different disease settings. Furthermore, in an effort to address some of the toxicity concerns with ibrutinib, more specific BTK inhibitors are also being developed.

Other kinases that orchestrate the BCR pathway, including phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and SYK, are also being targeted. The delta isoform of PI3K is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells and a number of PI3K delta inhibitors have been developed. Idelalisib received regulatory approval for the treatment of patients with CLL in combination with rituximab, and for patients with follicular lymphoma and small lymphocytic leukemia.

As with ibrutinib, a plethora of clinical trials are ongoing, however a major setback was suffered in the frontline setting when Gilead Sciences halted 6 clinical trials due to reports of increased rates of adverse events, including deaths.26 Meanwhile, SYK inhibitors have lagged behind somewhat in their development, but one such offering, entospletinib, is showing promise in patients with AML.27

Finally, there has been some success in targeting one of the downstream targets of the BCR signaling pathway, the Bcl2 protein that is involved in the regulation of apoptosis. Venetoclax was approved last year for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL in patients who have a chromosome 17p deletion, based on the demonstration of impressive, durable responses.28

1. Bachireddy P, Burkhardt UE, Rajasagi M, Wu CJ. Haemato- logical malignancies: at the forefront of immunotherapeutic innovation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):201-215.

2. Im A, Pavletic SZ. Immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies: past, present, and future. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):94.

3. Gill S. Planes, trains, and automobiles: perspectives on CAR T cells and other cellular therapies for hematologic malignancies. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(4):318-325.

4. Ye B, Stary CM, Gao Q, et al. Genetically modified T-cell-based adoptive immunotherapy in hematological malignancies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5237740/. Published January 2, 2017. Accessed July 22, 2017.

5. Sharpe M, Mount N. Genetically modified T cells in cancer therapy: opportunities and challenges. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8(4):337-350.

6. Novartis. Novartis personalized cell therapy CTL019 receives FDA breakthrough therapy designation. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-personalized-cell-therapy-ctl019-receivesfda-breakthrough-therapy. Published July 7, 2014. Accessed June 19,

2017.

7. Novartis. Novartis presents results from first global registration trial of CTL019 in pediatric and young adult patients with r/r B-ALL. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-presentsresults-first-global-registration-trial-ctl019-pediatric-and. Published December 4, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

8. Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 Results of ZUMA1: a multicenter study of KTE-C19 Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in refractory aggressive lymphoma. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):285-295.

9. Abramson JS, Palomba L, Gordon L. Transcend NHL 001: immunotherapy with the CD19-Directd CAR T-cell product JCAR017 results in high complete response rates in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Paper presented at 58th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; December 3-6, 2016; San Diego, CA.

10. Fan F, Zhao W, Liu J, et al. Durable remissions with BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl;):Abstr LBA3001.

11. Okroj M, Osterborg A, Blom AM. Effector mechanisms of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in B cell malignancies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):632-639.

12. Safdari Y, Ahmadzadeh V, Farajnia S. CD20-targeting in B-cell malignancies: novel prospects for antibodies and combination therapies. Invest New Drugs. 2016;34(4):497-512.

13. van Oers MH, Kuliczkowski K, Smolej L, et al. Ofatumumab maintenance versus observation in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (PROLONG): an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1370-1379.

14. Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1081-1093.

15. Touzeau C, Moreau P, Dumontet C. Monoclonal antibody therapy in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2017;31(5):1039-1047.

16. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):754-766.

17. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(14):1319-1331.

18. Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, Corvaia N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(5):315-337.

19. Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):740-753.

20. Hills RK, Castaigne S, Appelbaum FR, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):986-996.

21. Huehls AM, Coupet TA, Sentman CL. Bispecific T-cell engagers for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;93(3):290-296.

22. Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gokbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):836-847.

23. Koehrer S, Burger JA. B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B-cell malignancies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14(1):55-65.

24. Seda V, Mraz M. B-cell receptor signalling and its crosstalk with other pathways in normal and malignant cells. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94(3):193-205.

25. Bojarczuk K, Bobrowicz M, Dwojak M, et al. B-cell receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of lymphoid malignancies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;55(3):255-265.

26. Medscape Medical News. Gilead stops six trials adding idelalisib to other drugs. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/860372. Published March 14, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

27. Sharman J, Di Paolo J. Targeting B-cell receptor signaling kinases in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the promise of entospletinib. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(3):157-170.

28. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new drug for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with a specific chromosomal abnormality. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm495253.htm. Released April 11, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is evolving faster than ever before, with a range of available therapeutic options that is now almost as diverse as this group of tumors. Immunotherapy in particular is front and center in the battle to control these diseases. Here, we describe the latest promising developments.

Exploiting T cells

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is diverse, but one particular type of therapy has led the charge in improving patient outcomes. Several features of hematologic malignancies may make them particularly amenable to immunotherapy, including the fact that they are derived from corrupt immune cells and come into constant contact with other immune cells within the hematopoietic environment in which they reside. One of the oldest forms of immunotherapy, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), remains the only curative option for many patients with hematologic malignancies.1,2

Given the central role of T lymphocytes in antitumor immunity, research efforts have focused on harnessing their activity for cancer treatment. One example of this is adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), in which T cells are collected from a patient, grown outside the body to increase their number and then reinfused back to the patient. Allogeneic HSCT, in which the stem cells are collected from a matching donor and transplanted into the patient, is a crude example of ACT. The graft-versus-tumor effect is driven by donor cells present in the transplant, but is limited by the development of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), whereby the donor T cells attack healthy host tissue.

Other types of ACT have been developed in an effort to capitalize on the anti-tumor effects of the patients own T cells and thus avoid the potentially fatal complication of GvHD. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy was developed to exploit the presence of tumor-specific T cells in the tumor microenvironment. To date, the efficacy of TIL therapy has been predominantly limited to melanoma.1,3,4

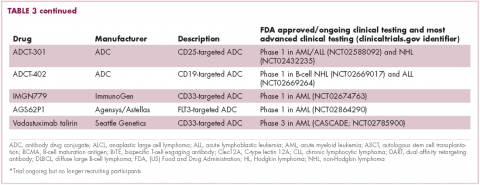

Most recently, there has been a substantial buzz around the idea of genetically engineering T cells before they are reintroduced into the patient, to increase their anti-tumor efficacy and minimize damage to healthy tissue. This is achieved either by manipulating the antigen binding portion of the T-cell receptor to alter its specificity (TCR T cells) or by generating artificial fusion receptors known as chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells; Figure 1). The former is limited by the need for the TCR to be genetically matched to the patient’s immune type, whereas the latter is more flexible in this regard and has proved most successful.

CARs are formed by fusing part of the single-chain variable fragment of a monoclonal antibody to part of the TCR and one or more costimulatory molecules. In this way, the T cell is guided to the tumor through antibody recognition of a particular tumor-associated antigen, whereupon its effector functions are activated by engagement of the TCR and costimulatory signal.5

Headlining advancements with CAR T cells

CAR T cells directed against the CD19 antigen, found on the surface of many hematologic malignancies, are the most clinically advanced in this rapidly evolving field (Table 1). Durable remissions have been demonstrated in patients with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL), with efficacy in both the pre- and posttransplant setting and in patients with chemotherapy-refractory disease.4,5

CTL019, a CD19-targeted CAR-T cell therapy, also known as tisagenlecleucel-T, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL and, more recently, for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma.6

It is edging closer to FDA approval for the ALL indication, having been granted priority review in March on the basis of the phase 2 ELIANA trial, in which 50 patients received a single infusion of CTL019. Data presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016 showed that 82% of patients achieved either complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi) 3 months after treatment.7

Meanwhile, Kite Pharma has a rolling submission with the FDA for KTE-C19 (axicabtagene ciloleucel) for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell NHL who are ineligible for HSCT. In the ZUMA-1 trial, this therapy demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 71%.8 Juno Therapeutics is developing several CAR T-cell therapies, including JCAR017, which elicited CR in 60% of patients with relapsed/refractory NHL.9

Target antigens other than CD19 are being explored, but these are mostly in the early stages of clinical development. While the focus has predominantly been on the treatment of lymphoma and leukemia, a presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting in June reported the efficacy of a CAR-T cell therapy targeting the B-cell maturation antigen in patients with multiple myeloma. Results from 19 patients enrolled in an ongoing phase 1 trial in China showed that 14 had achieved stringent CR, 1 partial remission (PR) and 4 very good partial remission (VGPR).10

Antibodies evolve

Another type of immunotherapy that has revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies is monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), targeting antigens on the surface of malignant B and T cells, in particular CD20. The approval of CD20-targeting mAb rituximab in 1997 was the first coup for the development of immunotherapy for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. It has become part of the standard treatment regimen for B-cell malignancies, including NHL and CLL, in combination with various types of chemotherapy.

Several other CD20-targeting antibodies have been developed (Table 2), some of which work in the same way as rituximab (eg, ofatumumab) and some that have a slightly different mechanism of action (eg, obinutuzumab).11 Both types of antibody have proved highly effective; ofatumumab is FDA approved for the treatment of advanced CLL and is being evaluated in phase 3 trials in other hematologic malignancies, while obinutuzumab has received regulatory approval for the first-line treatment of CLL, replacing the standard rituximab-containing regimen.12

The use of ofatumumab as maintenance therapy is supported by the results of the phase 3 PROLONG study in which 474 patients were randomly assigned to ofatumumab maintenance for 2 years or observation. Over a median follow-up of close to 20 months, ofatumumab-treated patients experienced improved progression-free survival (PFS; median PFS: 29.4 months vs 15.2 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.50; P < .0001).13 Obinutuzumab’s new indication is based on data from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial, in which the obinutuzumab arm showed improved 3-year PFS compared with rituximab.14Until recently, multiple myeloma had proven relatively resistant to mAb therapy, but two new drug targets have dramatically altered the treatment landscape for this type of hematologic malignancy. CD2 subset 1 (CS1), also known as signaling lymphocytic activation molecule 7 (SLAMF7), and CD38 are glycoproteins expressed highly and nearly uniformly on the surface of multiple myeloma cells and only at low levels on other lymphoid and myeloid cells.15

Several antibodies directed at these targets are in clinical development, but daratumumab and elotuzumab, targeting CD38 and CS1, respectively, are both newly approved by the FDA for relapsed/refractory disease, daratumumab as monotherapy and elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The indication for daratumumab was subsequently expanded to include its use in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone or bortezomib plus dexamethasone. Support for this new indication came from 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. In the CASTOR trial, the combination of daratumumab with bortezomib–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 61%, compared with bortezomib–dexamethasone alone, whereas daratumumab with lenalidomide–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 63% in the POLLUX trial.16,17

Numerous clinical trials for both drugs are ongoing, including in the front-line setting in multiple myeloma, as well as trials in other types of B-cell malignancy, and several other CD38-targeting mAbs are also in development, including isatuximab, which has reached the phase 3 stage (NCT02990338).

Innovative design

Newer drug designs, which have sought to take mAb therapy to the next level, have also shown significant efficacy in hematologic malignancies. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) combine the cytotoxic efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents with the specificity of a mAb targeting a tumor-specific antigen. This essentially creates a targeted payload that improves upon the efficacy of mAb monotherapy but mitigates some of the side effects of chemotherapy related to their indiscriminate killing of both cancerous and healthy cells.

The development of ADCs has been somewhat of a rollercoaster ride, with the approval and subsequent withdrawal of the first-in-class drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin in 2010, but the field was reinvigorated with the successful development of brentuximab vedotin, which targets the CD30 antigen and is approved for the treatment of multiple different hematologic malignancies, including, most recently, for posttransplant consolidation therapy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma at high risk of relapse or progression.18

Brentuximab vedotin may soon be joined by another FDA-approved ADC, this one targeting CD22. Inotuzumab ozogamicin was recently granted priority review for the treatment of relapsed/refractory ALL. The FDA is reviewing data from the phase 3 INO-VATE study in which inotuzumab ozogamicin reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 55% compared with standard therapy, and a decision is expected by August.19 Other ADC targets being investigated in clinical trials include CD138, CD19, and CD33 (Table 3). Meanwhile, a meta-analysis of randomized trials suggested that the withdrawal of gemtuzumab ozogamicin may have been premature, indicating that it does improve long-term overall survival (OS) and reduces the risk of relapse.20

Bispecific antibodies that link natural killer (NK) cells to tumor cells, by targeting the NK-cell receptor CD16, known as BiKEs, are also in development in an attempt to harness the power of the innate immune response.

B-cell signaling a ripe target

Beyond immunotherapy, molecularly targeted drugs directed against key drivers of hematologic malignancies are also showing great promise. In particular, the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway, a central regulator of B-cell function, and its constituent kinases that are frequently dysregulated in B cell malignancies, has emerged as an exciting therapeutic avenue.

A variety of small molecule inhibitors targeting different nodes of the BCR pathway have been developed (Table 4), but the greatest success to date has been achieved with drugs targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK). Their clinical development culminated in the approval of ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma in 2013 and subsequently for patients with CLL, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and most recently for patients with marginal zone lymphoma.

More than 100 clinical trials of ibrutinib are ongoing in an effort to further clarify its role in a variety of different disease settings. Furthermore, in an effort to address some of the toxicity concerns with ibrutinib, more specific BTK inhibitors are also being developed.

Other kinases that orchestrate the BCR pathway, including phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and SYK, are also being targeted. The delta isoform of PI3K is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells and a number of PI3K delta inhibitors have been developed. Idelalisib received regulatory approval for the treatment of patients with CLL in combination with rituximab, and for patients with follicular lymphoma and small lymphocytic leukemia.

As with ibrutinib, a plethora of clinical trials are ongoing, however a major setback was suffered in the frontline setting when Gilead Sciences halted 6 clinical trials due to reports of increased rates of adverse events, including deaths.26 Meanwhile, SYK inhibitors have lagged behind somewhat in their development, but one such offering, entospletinib, is showing promise in patients with AML.27

Finally, there has been some success in targeting one of the downstream targets of the BCR signaling pathway, the Bcl2 protein that is involved in the regulation of apoptosis. Venetoclax was approved last year for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL in patients who have a chromosome 17p deletion, based on the demonstration of impressive, durable responses.28

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is evolving faster than ever before, with a range of available therapeutic options that is now almost as diverse as this group of tumors. Immunotherapy in particular is front and center in the battle to control these diseases. Here, we describe the latest promising developments.

Exploiting T cells

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is diverse, but one particular type of therapy has led the charge in improving patient outcomes. Several features of hematologic malignancies may make them particularly amenable to immunotherapy, including the fact that they are derived from corrupt immune cells and come into constant contact with other immune cells within the hematopoietic environment in which they reside. One of the oldest forms of immunotherapy, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), remains the only curative option for many patients with hematologic malignancies.1,2

Given the central role of T lymphocytes in antitumor immunity, research efforts have focused on harnessing their activity for cancer treatment. One example of this is adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), in which T cells are collected from a patient, grown outside the body to increase their number and then reinfused back to the patient. Allogeneic HSCT, in which the stem cells are collected from a matching donor and transplanted into the patient, is a crude example of ACT. The graft-versus-tumor effect is driven by donor cells present in the transplant, but is limited by the development of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), whereby the donor T cells attack healthy host tissue.

Other types of ACT have been developed in an effort to capitalize on the anti-tumor effects of the patients own T cells and thus avoid the potentially fatal complication of GvHD. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy was developed to exploit the presence of tumor-specific T cells in the tumor microenvironment. To date, the efficacy of TIL therapy has been predominantly limited to melanoma.1,3,4

Most recently, there has been a substantial buzz around the idea of genetically engineering T cells before they are reintroduced into the patient, to increase their anti-tumor efficacy and minimize damage to healthy tissue. This is achieved either by manipulating the antigen binding portion of the T-cell receptor to alter its specificity (TCR T cells) or by generating artificial fusion receptors known as chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells; Figure 1). The former is limited by the need for the TCR to be genetically matched to the patient’s immune type, whereas the latter is more flexible in this regard and has proved most successful.

CARs are formed by fusing part of the single-chain variable fragment of a monoclonal antibody to part of the TCR and one or more costimulatory molecules. In this way, the T cell is guided to the tumor through antibody recognition of a particular tumor-associated antigen, whereupon its effector functions are activated by engagement of the TCR and costimulatory signal.5

Headlining advancements with CAR T cells

CAR T cells directed against the CD19 antigen, found on the surface of many hematologic malignancies, are the most clinically advanced in this rapidly evolving field (Table 1). Durable remissions have been demonstrated in patients with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL), with efficacy in both the pre- and posttransplant setting and in patients with chemotherapy-refractory disease.4,5

CTL019, a CD19-targeted CAR-T cell therapy, also known as tisagenlecleucel-T, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL and, more recently, for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma.6

It is edging closer to FDA approval for the ALL indication, having been granted priority review in March on the basis of the phase 2 ELIANA trial, in which 50 patients received a single infusion of CTL019. Data presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016 showed that 82% of patients achieved either complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi) 3 months after treatment.7

Meanwhile, Kite Pharma has a rolling submission with the FDA for KTE-C19 (axicabtagene ciloleucel) for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell NHL who are ineligible for HSCT. In the ZUMA-1 trial, this therapy demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 71%.8 Juno Therapeutics is developing several CAR T-cell therapies, including JCAR017, which elicited CR in 60% of patients with relapsed/refractory NHL.9

Target antigens other than CD19 are being explored, but these are mostly in the early stages of clinical development. While the focus has predominantly been on the treatment of lymphoma and leukemia, a presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting in June reported the efficacy of a CAR-T cell therapy targeting the B-cell maturation antigen in patients with multiple myeloma. Results from 19 patients enrolled in an ongoing phase 1 trial in China showed that 14 had achieved stringent CR, 1 partial remission (PR) and 4 very good partial remission (VGPR).10

Antibodies evolve

Another type of immunotherapy that has revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies is monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), targeting antigens on the surface of malignant B and T cells, in particular CD20. The approval of CD20-targeting mAb rituximab in 1997 was the first coup for the development of immunotherapy for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. It has become part of the standard treatment regimen for B-cell malignancies, including NHL and CLL, in combination with various types of chemotherapy.

Several other CD20-targeting antibodies have been developed (Table 2), some of which work in the same way as rituximab (eg, ofatumumab) and some that have a slightly different mechanism of action (eg, obinutuzumab).11 Both types of antibody have proved highly effective; ofatumumab is FDA approved for the treatment of advanced CLL and is being evaluated in phase 3 trials in other hematologic malignancies, while obinutuzumab has received regulatory approval for the first-line treatment of CLL, replacing the standard rituximab-containing regimen.12

The use of ofatumumab as maintenance therapy is supported by the results of the phase 3 PROLONG study in which 474 patients were randomly assigned to ofatumumab maintenance for 2 years or observation. Over a median follow-up of close to 20 months, ofatumumab-treated patients experienced improved progression-free survival (PFS; median PFS: 29.4 months vs 15.2 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.50; P < .0001).13 Obinutuzumab’s new indication is based on data from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial, in which the obinutuzumab arm showed improved 3-year PFS compared with rituximab.14Until recently, multiple myeloma had proven relatively resistant to mAb therapy, but two new drug targets have dramatically altered the treatment landscape for this type of hematologic malignancy. CD2 subset 1 (CS1), also known as signaling lymphocytic activation molecule 7 (SLAMF7), and CD38 are glycoproteins expressed highly and nearly uniformly on the surface of multiple myeloma cells and only at low levels on other lymphoid and myeloid cells.15

Several antibodies directed at these targets are in clinical development, but daratumumab and elotuzumab, targeting CD38 and CS1, respectively, are both newly approved by the FDA for relapsed/refractory disease, daratumumab as monotherapy and elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The indication for daratumumab was subsequently expanded to include its use in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone or bortezomib plus dexamethasone. Support for this new indication came from 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. In the CASTOR trial, the combination of daratumumab with bortezomib–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 61%, compared with bortezomib–dexamethasone alone, whereas daratumumab with lenalidomide–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 63% in the POLLUX trial.16,17

Numerous clinical trials for both drugs are ongoing, including in the front-line setting in multiple myeloma, as well as trials in other types of B-cell malignancy, and several other CD38-targeting mAbs are also in development, including isatuximab, which has reached the phase 3 stage (NCT02990338).

Innovative design

Newer drug designs, which have sought to take mAb therapy to the next level, have also shown significant efficacy in hematologic malignancies. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) combine the cytotoxic efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents with the specificity of a mAb targeting a tumor-specific antigen. This essentially creates a targeted payload that improves upon the efficacy of mAb monotherapy but mitigates some of the side effects of chemotherapy related to their indiscriminate killing of both cancerous and healthy cells.

The development of ADCs has been somewhat of a rollercoaster ride, with the approval and subsequent withdrawal of the first-in-class drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin in 2010, but the field was reinvigorated with the successful development of brentuximab vedotin, which targets the CD30 antigen and is approved for the treatment of multiple different hematologic malignancies, including, most recently, for posttransplant consolidation therapy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma at high risk of relapse or progression.18

Brentuximab vedotin may soon be joined by another FDA-approved ADC, this one targeting CD22. Inotuzumab ozogamicin was recently granted priority review for the treatment of relapsed/refractory ALL. The FDA is reviewing data from the phase 3 INO-VATE study in which inotuzumab ozogamicin reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 55% compared with standard therapy, and a decision is expected by August.19 Other ADC targets being investigated in clinical trials include CD138, CD19, and CD33 (Table 3). Meanwhile, a meta-analysis of randomized trials suggested that the withdrawal of gemtuzumab ozogamicin may have been premature, indicating that it does improve long-term overall survival (OS) and reduces the risk of relapse.20

Bispecific antibodies that link natural killer (NK) cells to tumor cells, by targeting the NK-cell receptor CD16, known as BiKEs, are also in development in an attempt to harness the power of the innate immune response.

B-cell signaling a ripe target

Beyond immunotherapy, molecularly targeted drugs directed against key drivers of hematologic malignancies are also showing great promise. In particular, the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway, a central regulator of B-cell function, and its constituent kinases that are frequently dysregulated in B cell malignancies, has emerged as an exciting therapeutic avenue.

A variety of small molecule inhibitors targeting different nodes of the BCR pathway have been developed (Table 4), but the greatest success to date has been achieved with drugs targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK). Their clinical development culminated in the approval of ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma in 2013 and subsequently for patients with CLL, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and most recently for patients with marginal zone lymphoma.

More than 100 clinical trials of ibrutinib are ongoing in an effort to further clarify its role in a variety of different disease settings. Furthermore, in an effort to address some of the toxicity concerns with ibrutinib, more specific BTK inhibitors are also being developed.

Other kinases that orchestrate the BCR pathway, including phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and SYK, are also being targeted. The delta isoform of PI3K is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells and a number of PI3K delta inhibitors have been developed. Idelalisib received regulatory approval for the treatment of patients with CLL in combination with rituximab, and for patients with follicular lymphoma and small lymphocytic leukemia.

As with ibrutinib, a plethora of clinical trials are ongoing, however a major setback was suffered in the frontline setting when Gilead Sciences halted 6 clinical trials due to reports of increased rates of adverse events, including deaths.26 Meanwhile, SYK inhibitors have lagged behind somewhat in their development, but one such offering, entospletinib, is showing promise in patients with AML.27

Finally, there has been some success in targeting one of the downstream targets of the BCR signaling pathway, the Bcl2 protein that is involved in the regulation of apoptosis. Venetoclax was approved last year for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL in patients who have a chromosome 17p deletion, based on the demonstration of impressive, durable responses.28

1. Bachireddy P, Burkhardt UE, Rajasagi M, Wu CJ. Haemato- logical malignancies: at the forefront of immunotherapeutic innovation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):201-215.

2. Im A, Pavletic SZ. Immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies: past, present, and future. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):94.

3. Gill S. Planes, trains, and automobiles: perspectives on CAR T cells and other cellular therapies for hematologic malignancies. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(4):318-325.

4. Ye B, Stary CM, Gao Q, et al. Genetically modified T-cell-based adoptive immunotherapy in hematological malignancies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5237740/. Published January 2, 2017. Accessed July 22, 2017.

5. Sharpe M, Mount N. Genetically modified T cells in cancer therapy: opportunities and challenges. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8(4):337-350.

6. Novartis. Novartis personalized cell therapy CTL019 receives FDA breakthrough therapy designation. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-personalized-cell-therapy-ctl019-receivesfda-breakthrough-therapy. Published July 7, 2014. Accessed June 19,

2017.

7. Novartis. Novartis presents results from first global registration trial of CTL019 in pediatric and young adult patients with r/r B-ALL. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-presentsresults-first-global-registration-trial-ctl019-pediatric-and. Published December 4, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

8. Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 Results of ZUMA1: a multicenter study of KTE-C19 Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in refractory aggressive lymphoma. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):285-295.

9. Abramson JS, Palomba L, Gordon L. Transcend NHL 001: immunotherapy with the CD19-Directd CAR T-cell product JCAR017 results in high complete response rates in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Paper presented at 58th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; December 3-6, 2016; San Diego, CA.

10. Fan F, Zhao W, Liu J, et al. Durable remissions with BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl;):Abstr LBA3001.

11. Okroj M, Osterborg A, Blom AM. Effector mechanisms of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in B cell malignancies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):632-639.

12. Safdari Y, Ahmadzadeh V, Farajnia S. CD20-targeting in B-cell malignancies: novel prospects for antibodies and combination therapies. Invest New Drugs. 2016;34(4):497-512.

13. van Oers MH, Kuliczkowski K, Smolej L, et al. Ofatumumab maintenance versus observation in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (PROLONG): an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1370-1379.

14. Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1081-1093.

15. Touzeau C, Moreau P, Dumontet C. Monoclonal antibody therapy in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2017;31(5):1039-1047.

16. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):754-766.

17. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(14):1319-1331.

18. Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, Corvaia N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(5):315-337.

19. Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):740-753.

20. Hills RK, Castaigne S, Appelbaum FR, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):986-996.

21. Huehls AM, Coupet TA, Sentman CL. Bispecific T-cell engagers for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;93(3):290-296.

22. Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gokbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):836-847.

23. Koehrer S, Burger JA. B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B-cell malignancies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14(1):55-65.

24. Seda V, Mraz M. B-cell receptor signalling and its crosstalk with other pathways in normal and malignant cells. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94(3):193-205.

25. Bojarczuk K, Bobrowicz M, Dwojak M, et al. B-cell receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of lymphoid malignancies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;55(3):255-265.

26. Medscape Medical News. Gilead stops six trials adding idelalisib to other drugs. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/860372. Published March 14, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

27. Sharman J, Di Paolo J. Targeting B-cell receptor signaling kinases in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the promise of entospletinib. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(3):157-170.

28. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new drug for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with a specific chromosomal abnormality. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm495253.htm. Released April 11, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

1. Bachireddy P, Burkhardt UE, Rajasagi M, Wu CJ. Haemato- logical malignancies: at the forefront of immunotherapeutic innovation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):201-215.

2. Im A, Pavletic SZ. Immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies: past, present, and future. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):94.

3. Gill S. Planes, trains, and automobiles: perspectives on CAR T cells and other cellular therapies for hematologic malignancies. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(4):318-325.

4. Ye B, Stary CM, Gao Q, et al. Genetically modified T-cell-based adoptive immunotherapy in hematological malignancies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5237740/. Published January 2, 2017. Accessed July 22, 2017.

5. Sharpe M, Mount N. Genetically modified T cells in cancer therapy: opportunities and challenges. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8(4):337-350.

6. Novartis. Novartis personalized cell therapy CTL019 receives FDA breakthrough therapy designation. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-personalized-cell-therapy-ctl019-receivesfda-breakthrough-therapy. Published July 7, 2014. Accessed June 19,

2017.

7. Novartis. Novartis presents results from first global registration trial of CTL019 in pediatric and young adult patients with r/r B-ALL. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-presentsresults-first-global-registration-trial-ctl019-pediatric-and. Published December 4, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

8. Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 Results of ZUMA1: a multicenter study of KTE-C19 Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in refractory aggressive lymphoma. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):285-295.

9. Abramson JS, Palomba L, Gordon L. Transcend NHL 001: immunotherapy with the CD19-Directd CAR T-cell product JCAR017 results in high complete response rates in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Paper presented at 58th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; December 3-6, 2016; San Diego, CA.

10. Fan F, Zhao W, Liu J, et al. Durable remissions with BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl;):Abstr LBA3001.

11. Okroj M, Osterborg A, Blom AM. Effector mechanisms of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in B cell malignancies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):632-639.

12. Safdari Y, Ahmadzadeh V, Farajnia S. CD20-targeting in B-cell malignancies: novel prospects for antibodies and combination therapies. Invest New Drugs. 2016;34(4):497-512.

13. van Oers MH, Kuliczkowski K, Smolej L, et al. Ofatumumab maintenance versus observation in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (PROLONG): an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1370-1379.

14. Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1081-1093.

15. Touzeau C, Moreau P, Dumontet C. Monoclonal antibody therapy in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2017;31(5):1039-1047.

16. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):754-766.

17. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(14):1319-1331.

18. Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, Corvaia N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(5):315-337.

19. Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):740-753.

20. Hills RK, Castaigne S, Appelbaum FR, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):986-996.

21. Huehls AM, Coupet TA, Sentman CL. Bispecific T-cell engagers for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;93(3):290-296.

22. Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gokbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):836-847.

23. Koehrer S, Burger JA. B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B-cell malignancies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14(1):55-65.

24. Seda V, Mraz M. B-cell receptor signalling and its crosstalk with other pathways in normal and malignant cells. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94(3):193-205.

25. Bojarczuk K, Bobrowicz M, Dwojak M, et al. B-cell receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of lymphoid malignancies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;55(3):255-265.

26. Medscape Medical News. Gilead stops six trials adding idelalisib to other drugs. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/860372. Published March 14, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

27. Sharman J, Di Paolo J. Targeting B-cell receptor signaling kinases in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the promise of entospletinib. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(3):157-170.

28. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new drug for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with a specific chromosomal abnormality. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm495253.htm. Released April 11, 2016. Accessed June 19, 2017.

Bendamustine-Based Salvage Regimen Offers Hope

Many patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) experience rapid, aggressive progression of CNS malignancy. It is “accepted,” say researchers from Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital in the Republic of Korea, that salvage therapy is beneficial and significantly improves survival in comparison to palliative care, but therapy options remain limited—mainly because few trials have been done. Several case reports have suggested that bendamustine has modest clinical activity against relapsed PCNSL, the researchers note, but its effect as part of combination salvage therapy in these patients has not been established. The study offers some validation of previous findings and new information about the benefits of a bendamustine-based combination regimen.

The researchers enrolled 10 patients, of whom 7 had refractory disease. All had previously been on high-dose methotrexate. Of the 3 relapsed patients, 1 entered the study at second relapse. The patients received either R-B(O)AD or R-BAD (rituximab, vincristine, bendamustine, cytarabine, dexamethasone) every 4 weeks for up to 4 cycles. Vincristine was omitted in 4 regimens, and dosages of bendamustine and cytarabine were reduced for 4 patients who were over 70.

The overall response rate for R-B(O)AD was 50%. One patient achieved complete response and 4 achieved partial response. The researchers observed “remarkable effects” on imaging in patients who responded. They attribute the activity to the anticipated synergy of bendamustine combined with cytarabine—even though disease in the majority of the patients had progressed despite previous treatment with cytarabine.

However, the synergistic effects also led to significant marrow depression; hematologic toxicity with R-B(O)AD was “considerable,” with grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia seen in more than 85% of treatment cycles. Moreover, 3 patients developed severe infection, all with involvement of the lungs. The researchers therefore amended the study protocol to reduce cytarabine dosage. While the toxicity is significant, the researchers say, it is manageable with the dose reduction and supportive care.

Bendamustine cerebrospinal fluid levels were minimal, but corresponded to plasma exposure and response to treatment in deep tumor locations.

Although the study is small, it supports the use of the bendamustine-based regimen as an effective salvage option, the researchers conclude, especially for patients who are no longer responding to methotrexate or have developed cumulative renal or neurotoxicity from treatment.

Source:

Kim T, Choi HY, Lee HS, et al. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):729

Many patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) experience rapid, aggressive progression of CNS malignancy. It is “accepted,” say researchers from Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital in the Republic of Korea, that salvage therapy is beneficial and significantly improves survival in comparison to palliative care, but therapy options remain limited—mainly because few trials have been done. Several case reports have suggested that bendamustine has modest clinical activity against relapsed PCNSL, the researchers note, but its effect as part of combination salvage therapy in these patients has not been established. The study offers some validation of previous findings and new information about the benefits of a bendamustine-based combination regimen.