User login

Can Serum Free Light Chains Be Used for the Early Diagnosis of Monoclonal Immunoglobulin-Secreting B-Cell and Plasma-Cell Diseases? (FULL)

Patients who are undergoing multiple myeloma screening with serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, especially those with renal failure, also should receive serum free light chain testing to increase specificity and reduce false-negatives.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a devastating disease with an estimated 26,850 new cases in 2015 according to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data and no definitive chemotherapeutic cure.1 In 97% of cases, MM is defined by monoclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, in which a malignant plasma cell clone secretes a monoclonal globulin; the remaining cases are nonsecretors.2 Each pathologically produced clonal globulin contains 2 heavy chains attached by disulfide linkage and 2 light chains. Unchecked plasma cell production is what later causes the symptoms of renal failure, bone destruction, and anemia.

The rate of MM is disproportionately high in the veteran population, and the VA health care system provides care for many of these patients. The higher rate is likely secondary to the predominantly male population, which has higher MM rates, and has been linked to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam. As MM is not easy to diagnose, any algorithm or testing method would be of great benefit to this population.

The gold standard for MM detection remains serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) with immunofixation (IFE), but other detection methods have been emerging. The method of serum free light chain (SFLC) assay has become more readily available, and its incorporation into diagnostic guidelines has become more apparent but is not universal.3

In the case series reported in this article, SPEP/IFE and SFLC assays were used to test 207 patients from the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS). All these patients had a clinical context for MM testing.

Methods

In this retrospective study, the authors reviewed the charts of VANYHHS patients who were being treated for conditions that prompted SPEP/IFE and λ and κ SFLC analysis between December 2013 and March 2014. The study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

The SPEP/IFE analysis was performed with an automated electrophoresis machine (Sebia Electrophoresis), and the SFLC analysis was performed with an automated SFLC assay (Freelite). Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated using SPEP/IFE as the gold standard and SFLC κ-to-λ ratio asthe test method. Patients with a positive κ-to-λ ratio but negative SPEP were considered false-positives. These patients’ SFLC analyses were further analyzed in an effort to evaluate use of the κ-to-λ ratio as an early tumor marker.

The κ reference range used was 3.3 to 19.4 mg/L, and the λ reference range used was 5.7 to 26.3 mg/L.4 The traditional reference range for the κ-to-λ ratio is 0.26 to 1.65.5

Results

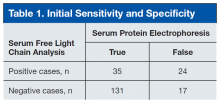

Of the 207 patients in this study, 205 were men. Mean age was 69 years (range, 28-97 years). Mean serum urea nitrogen level was 8.75 mmol/L (range, 2.86-38.21 mmol/L), and mean creatinine level was 140.59 μmol/L (range, 44.21-1503.14 μmol/L). Mean κ was 49.82 mg/L (range, 4.6-700.96 mg/L), and mean λ was 54.27 mg/L (range, 3-1,750 mg/L). Table 1 compares the SPEP and SFLC data. Sensitivity was 67%, specificity was 85%, positive predictive value was 58%, and negative predictive value was 89%. Concordance of the 2 methods was 80%. The false-positive group was followed up 16 months later to check for diagnosis of disease. Two of the 24 patients in this quadrant were later diagnosed with MM (Table 1).

One of the patients with MM was an 82-year-old African American man with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and prostate cancer (Gleason 4 + 4 = 8/10). He presented to VANYHHS after a fall in which he sustained a pathologic fracture of the left acromion. Recurrent prostate cancer was initially suspected, and nuclear bone scintigraphy revealed increased uptake in the left shoulder and the posterior ninth rib. Results of computed tomography-guided biopsy showed the rib lesion packed with plasma cells and consistent with MM. Immunohistochemical analysis was positive for CD138 and κ in the malignant plasma cells. Initial SPEP performed before the biopsy showed an acute phase reaction with hypogammaglobulinemia, and SPEP after the biopsy showed an increased α-2 band but no monoclonal gammaglobulinopathy. The initial κ of 42.18 mg/L (κ-to-λ ratio, 4.01) was up to 67.53 mg/L 4 months later.

The other patient with MM was a 91-year-old man who had coronary artery disease after undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting in 1993, sick sinus syndrome after pacemaker implantation, hypertension, and anemia. He initially presented to the geriatrics clinic with polyneuropathy, which prompted SPEP and SFLC analysis. SPEP results showed a normal electrophoretic pattern, but κ increased to 47.52 mg/L (κ-to-λ ratio, 2.63). The decision was made to monitor the patient in the hematology clinic. Subsequent κ chain analysis revealed an increase to 59.50 mg/L. A repeat SPEP, performed 1 year after the first SPEP, revealed monoclonal immunoglobulin A on IFE.

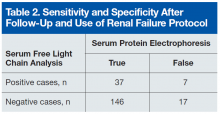

Of the 24 patients with false-positive results, 16 had moderate-to-severe kidney disease (stage IIIa-IV).6All patients in this quadrant were men; their mean age was 75 years, and their mean creatinine level was 182.15 μmol/L. Further laboratory data are listed in Table 2.

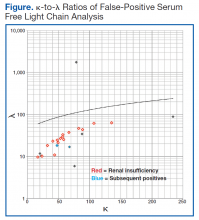

The patient whose biopsy results led to an MM diagnosis and the patient whose IFE led to a gammopathy diagnosis both maintained a glomerular filtration rate within normal limits. The Figure shows the κ-to-λ ratios of this quadrant logarithmically.

Discussion

Use of SFLC analysis as a supplement to serum and urine protein electrophoresis has been investigated and accepted in the recent literature.3,4,7,8 Use of light chains as a method of earlier or alternative detection has not been proved. In the present study of 207 patients, comparisons showed that more traditional MM detection methods and SFLC analysis are largely concordant. The 2 patients with MM and negative electrophoretic patterns provided a clear indication of the potential benefit of SFLC analysis in the diagnosis of secretory and nonsecretory myeloma.

In 2014, Kim and colleagues compared 2 SFLC assays (Freelite, N Latex) to each other and to SPEP in a 120-patient population.9 The Freelite results in their study correlated closely with VA population findings (κ-to-λ ratio sensitivity and specificity: 72.2% and 93.6%, respectively). N Latex, the newer SFLC assay, had lower sensitivity (64.6%) and higher specificity (100%). With application of the extended reference range (0.37-3.1) proposed by Hutchison and colleagues for use in patients with renal failure, SFLC becomes a more statistically powerful tool.5

The patients who tested false-positive had higher mean creatinine levels, and 16 had renal insufficiency. The 2 false-positive patients were later found to have clinical myeloma and were within the normal range of renal function. Of the 16 patients with an abnormal κ-to-λ ratio and renal failure, 15 would be within the revised normal reference range, leaving 9 false-positives, 2 of whom eventually were found to have disease. With the application of the extended light chain range (as per Hutchison) for those patients with renal failure, 15 of the original 24 false-positives became true-negatives. Two of the false-positives become true-positives after they were subsequently diagnosed. Therefore, SFLC analysis detected disease in 22% of the revised false-positives when SPEP could not.

Table 2 lists the revised data after follow-up and renal failure correction. The strongest aspect of SFLC analysis remains its 95% specificity; its 69% sensitivity remains relatively constant. The test’s positive predictive value is 84%, and its negative predictive value is 90%. In veteran and other at-risk populations, SFLC analysis proves to be a very powerful tool on its own.

Conclusion

Both patient cases described in this article demonstrate the usefulness of SFLC analysis as an adjunct to SPEP. The authors propose SFLC testing for all patients who are undergoing MM screening with SPEP/IFE. In patients with renal failure, the expanded reference range seems to reduce erroneous false-positive results. Patients who have abnormal ratios should be followed up in clinic with repeat MM testing. It seems clear that, at the very least, SFLC analysis is a necessary adjunct to SPEP testing. However, SFLC stands on its own merit as well.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER website. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed July 11, 2016.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

3. Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Fermand JP, et al; International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Consensus recommendations for standard investigative workup: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Blood. 2011;117(18):4701-4705.

4. Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1437-1444.

5. Hutchison CA, Plant T, Drayson M, et al. Serum free light chain measurement

aids the diagnosis of myeloma in patients with severe renal failure.

BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:11.

6. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease

Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration

rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612.

7. McTaggart MP, Lindsay J, Kearney EM. Replacing urine protein electrophoresis

with serum free light chain analysis as a first-line test for detecting plasma

cell disorders offers increased diagnostic accuracy and potential health benefit

to patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140(6):890-897.

8. Abadie JM, Bankson DD. Assessment of serum free light chain assays for

plasma cell disorder screening in a Veterans Affairs population. Ann Clin Lab

Sci. 2006;36(2):157-162.

9. Kim HS, Kim HS, Shin KS, et al. Clinical comparisons of two free light chain

assays to immunofixation electrophoresis for detecting monoclonal gammopathy.

Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:647238.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Patients who are undergoing multiple myeloma screening with serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, especially those with renal failure, also should receive serum free light chain testing to increase specificity and reduce false-negatives.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a devastating disease with an estimated 26,850 new cases in 2015 according to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data and no definitive chemotherapeutic cure.1 In 97% of cases, MM is defined by monoclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, in which a malignant plasma cell clone secretes a monoclonal globulin; the remaining cases are nonsecretors.2 Each pathologically produced clonal globulin contains 2 heavy chains attached by disulfide linkage and 2 light chains. Unchecked plasma cell production is what later causes the symptoms of renal failure, bone destruction, and anemia.

The rate of MM is disproportionately high in the veteran population, and the VA health care system provides care for many of these patients. The higher rate is likely secondary to the predominantly male population, which has higher MM rates, and has been linked to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam. As MM is not easy to diagnose, any algorithm or testing method would be of great benefit to this population.

The gold standard for MM detection remains serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) with immunofixation (IFE), but other detection methods have been emerging. The method of serum free light chain (SFLC) assay has become more readily available, and its incorporation into diagnostic guidelines has become more apparent but is not universal.3

In the case series reported in this article, SPEP/IFE and SFLC assays were used to test 207 patients from the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS). All these patients had a clinical context for MM testing.

Methods

In this retrospective study, the authors reviewed the charts of VANYHHS patients who were being treated for conditions that prompted SPEP/IFE and λ and κ SFLC analysis between December 2013 and March 2014. The study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

The SPEP/IFE analysis was performed with an automated electrophoresis machine (Sebia Electrophoresis), and the SFLC analysis was performed with an automated SFLC assay (Freelite). Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated using SPEP/IFE as the gold standard and SFLC κ-to-λ ratio asthe test method. Patients with a positive κ-to-λ ratio but negative SPEP were considered false-positives. These patients’ SFLC analyses were further analyzed in an effort to evaluate use of the κ-to-λ ratio as an early tumor marker.

The κ reference range used was 3.3 to 19.4 mg/L, and the λ reference range used was 5.7 to 26.3 mg/L.4 The traditional reference range for the κ-to-λ ratio is 0.26 to 1.65.5

Results

Of the 207 patients in this study, 205 were men. Mean age was 69 years (range, 28-97 years). Mean serum urea nitrogen level was 8.75 mmol/L (range, 2.86-38.21 mmol/L), and mean creatinine level was 140.59 μmol/L (range, 44.21-1503.14 μmol/L). Mean κ was 49.82 mg/L (range, 4.6-700.96 mg/L), and mean λ was 54.27 mg/L (range, 3-1,750 mg/L). Table 1 compares the SPEP and SFLC data. Sensitivity was 67%, specificity was 85%, positive predictive value was 58%, and negative predictive value was 89%. Concordance of the 2 methods was 80%. The false-positive group was followed up 16 months later to check for diagnosis of disease. Two of the 24 patients in this quadrant were later diagnosed with MM (Table 1).

One of the patients with MM was an 82-year-old African American man with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and prostate cancer (Gleason 4 + 4 = 8/10). He presented to VANYHHS after a fall in which he sustained a pathologic fracture of the left acromion. Recurrent prostate cancer was initially suspected, and nuclear bone scintigraphy revealed increased uptake in the left shoulder and the posterior ninth rib. Results of computed tomography-guided biopsy showed the rib lesion packed with plasma cells and consistent with MM. Immunohistochemical analysis was positive for CD138 and κ in the malignant plasma cells. Initial SPEP performed before the biopsy showed an acute phase reaction with hypogammaglobulinemia, and SPEP after the biopsy showed an increased α-2 band but no monoclonal gammaglobulinopathy. The initial κ of 42.18 mg/L (κ-to-λ ratio, 4.01) was up to 67.53 mg/L 4 months later.

The other patient with MM was a 91-year-old man who had coronary artery disease after undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting in 1993, sick sinus syndrome after pacemaker implantation, hypertension, and anemia. He initially presented to the geriatrics clinic with polyneuropathy, which prompted SPEP and SFLC analysis. SPEP results showed a normal electrophoretic pattern, but κ increased to 47.52 mg/L (κ-to-λ ratio, 2.63). The decision was made to monitor the patient in the hematology clinic. Subsequent κ chain analysis revealed an increase to 59.50 mg/L. A repeat SPEP, performed 1 year after the first SPEP, revealed monoclonal immunoglobulin A on IFE.

Of the 24 patients with false-positive results, 16 had moderate-to-severe kidney disease (stage IIIa-IV).6All patients in this quadrant were men; their mean age was 75 years, and their mean creatinine level was 182.15 μmol/L. Further laboratory data are listed in Table 2.

The patient whose biopsy results led to an MM diagnosis and the patient whose IFE led to a gammopathy diagnosis both maintained a glomerular filtration rate within normal limits. The Figure shows the κ-to-λ ratios of this quadrant logarithmically.

Discussion

Use of SFLC analysis as a supplement to serum and urine protein electrophoresis has been investigated and accepted in the recent literature.3,4,7,8 Use of light chains as a method of earlier or alternative detection has not been proved. In the present study of 207 patients, comparisons showed that more traditional MM detection methods and SFLC analysis are largely concordant. The 2 patients with MM and negative electrophoretic patterns provided a clear indication of the potential benefit of SFLC analysis in the diagnosis of secretory and nonsecretory myeloma.

In 2014, Kim and colleagues compared 2 SFLC assays (Freelite, N Latex) to each other and to SPEP in a 120-patient population.9 The Freelite results in their study correlated closely with VA population findings (κ-to-λ ratio sensitivity and specificity: 72.2% and 93.6%, respectively). N Latex, the newer SFLC assay, had lower sensitivity (64.6%) and higher specificity (100%). With application of the extended reference range (0.37-3.1) proposed by Hutchison and colleagues for use in patients with renal failure, SFLC becomes a more statistically powerful tool.5

The patients who tested false-positive had higher mean creatinine levels, and 16 had renal insufficiency. The 2 false-positive patients were later found to have clinical myeloma and were within the normal range of renal function. Of the 16 patients with an abnormal κ-to-λ ratio and renal failure, 15 would be within the revised normal reference range, leaving 9 false-positives, 2 of whom eventually were found to have disease. With the application of the extended light chain range (as per Hutchison) for those patients with renal failure, 15 of the original 24 false-positives became true-negatives. Two of the false-positives become true-positives after they were subsequently diagnosed. Therefore, SFLC analysis detected disease in 22% of the revised false-positives when SPEP could not.

Table 2 lists the revised data after follow-up and renal failure correction. The strongest aspect of SFLC analysis remains its 95% specificity; its 69% sensitivity remains relatively constant. The test’s positive predictive value is 84%, and its negative predictive value is 90%. In veteran and other at-risk populations, SFLC analysis proves to be a very powerful tool on its own.

Conclusion

Both patient cases described in this article demonstrate the usefulness of SFLC analysis as an adjunct to SPEP. The authors propose SFLC testing for all patients who are undergoing MM screening with SPEP/IFE. In patients with renal failure, the expanded reference range seems to reduce erroneous false-positive results. Patients who have abnormal ratios should be followed up in clinic with repeat MM testing. It seems clear that, at the very least, SFLC analysis is a necessary adjunct to SPEP testing. However, SFLC stands on its own merit as well.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Patients who are undergoing multiple myeloma screening with serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, especially those with renal failure, also should receive serum free light chain testing to increase specificity and reduce false-negatives.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a devastating disease with an estimated 26,850 new cases in 2015 according to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data and no definitive chemotherapeutic cure.1 In 97% of cases, MM is defined by monoclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, in which a malignant plasma cell clone secretes a monoclonal globulin; the remaining cases are nonsecretors.2 Each pathologically produced clonal globulin contains 2 heavy chains attached by disulfide linkage and 2 light chains. Unchecked plasma cell production is what later causes the symptoms of renal failure, bone destruction, and anemia.

The rate of MM is disproportionately high in the veteran population, and the VA health care system provides care for many of these patients. The higher rate is likely secondary to the predominantly male population, which has higher MM rates, and has been linked to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam. As MM is not easy to diagnose, any algorithm or testing method would be of great benefit to this population.

The gold standard for MM detection remains serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) with immunofixation (IFE), but other detection methods have been emerging. The method of serum free light chain (SFLC) assay has become more readily available, and its incorporation into diagnostic guidelines has become more apparent but is not universal.3

In the case series reported in this article, SPEP/IFE and SFLC assays were used to test 207 patients from the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS). All these patients had a clinical context for MM testing.

Methods

In this retrospective study, the authors reviewed the charts of VANYHHS patients who were being treated for conditions that prompted SPEP/IFE and λ and κ SFLC analysis between December 2013 and March 2014. The study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

The SPEP/IFE analysis was performed with an automated electrophoresis machine (Sebia Electrophoresis), and the SFLC analysis was performed with an automated SFLC assay (Freelite). Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated using SPEP/IFE as the gold standard and SFLC κ-to-λ ratio asthe test method. Patients with a positive κ-to-λ ratio but negative SPEP were considered false-positives. These patients’ SFLC analyses were further analyzed in an effort to evaluate use of the κ-to-λ ratio as an early tumor marker.

The κ reference range used was 3.3 to 19.4 mg/L, and the λ reference range used was 5.7 to 26.3 mg/L.4 The traditional reference range for the κ-to-λ ratio is 0.26 to 1.65.5

Results

Of the 207 patients in this study, 205 were men. Mean age was 69 years (range, 28-97 years). Mean serum urea nitrogen level was 8.75 mmol/L (range, 2.86-38.21 mmol/L), and mean creatinine level was 140.59 μmol/L (range, 44.21-1503.14 μmol/L). Mean κ was 49.82 mg/L (range, 4.6-700.96 mg/L), and mean λ was 54.27 mg/L (range, 3-1,750 mg/L). Table 1 compares the SPEP and SFLC data. Sensitivity was 67%, specificity was 85%, positive predictive value was 58%, and negative predictive value was 89%. Concordance of the 2 methods was 80%. The false-positive group was followed up 16 months later to check for diagnosis of disease. Two of the 24 patients in this quadrant were later diagnosed with MM (Table 1).

One of the patients with MM was an 82-year-old African American man with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and prostate cancer (Gleason 4 + 4 = 8/10). He presented to VANYHHS after a fall in which he sustained a pathologic fracture of the left acromion. Recurrent prostate cancer was initially suspected, and nuclear bone scintigraphy revealed increased uptake in the left shoulder and the posterior ninth rib. Results of computed tomography-guided biopsy showed the rib lesion packed with plasma cells and consistent with MM. Immunohistochemical analysis was positive for CD138 and κ in the malignant plasma cells. Initial SPEP performed before the biopsy showed an acute phase reaction with hypogammaglobulinemia, and SPEP after the biopsy showed an increased α-2 band but no monoclonal gammaglobulinopathy. The initial κ of 42.18 mg/L (κ-to-λ ratio, 4.01) was up to 67.53 mg/L 4 months later.

The other patient with MM was a 91-year-old man who had coronary artery disease after undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting in 1993, sick sinus syndrome after pacemaker implantation, hypertension, and anemia. He initially presented to the geriatrics clinic with polyneuropathy, which prompted SPEP and SFLC analysis. SPEP results showed a normal electrophoretic pattern, but κ increased to 47.52 mg/L (κ-to-λ ratio, 2.63). The decision was made to monitor the patient in the hematology clinic. Subsequent κ chain analysis revealed an increase to 59.50 mg/L. A repeat SPEP, performed 1 year after the first SPEP, revealed monoclonal immunoglobulin A on IFE.

Of the 24 patients with false-positive results, 16 had moderate-to-severe kidney disease (stage IIIa-IV).6All patients in this quadrant were men; their mean age was 75 years, and their mean creatinine level was 182.15 μmol/L. Further laboratory data are listed in Table 2.

The patient whose biopsy results led to an MM diagnosis and the patient whose IFE led to a gammopathy diagnosis both maintained a glomerular filtration rate within normal limits. The Figure shows the κ-to-λ ratios of this quadrant logarithmically.

Discussion

Use of SFLC analysis as a supplement to serum and urine protein electrophoresis has been investigated and accepted in the recent literature.3,4,7,8 Use of light chains as a method of earlier or alternative detection has not been proved. In the present study of 207 patients, comparisons showed that more traditional MM detection methods and SFLC analysis are largely concordant. The 2 patients with MM and negative electrophoretic patterns provided a clear indication of the potential benefit of SFLC analysis in the diagnosis of secretory and nonsecretory myeloma.

In 2014, Kim and colleagues compared 2 SFLC assays (Freelite, N Latex) to each other and to SPEP in a 120-patient population.9 The Freelite results in their study correlated closely with VA population findings (κ-to-λ ratio sensitivity and specificity: 72.2% and 93.6%, respectively). N Latex, the newer SFLC assay, had lower sensitivity (64.6%) and higher specificity (100%). With application of the extended reference range (0.37-3.1) proposed by Hutchison and colleagues for use in patients with renal failure, SFLC becomes a more statistically powerful tool.5

The patients who tested false-positive had higher mean creatinine levels, and 16 had renal insufficiency. The 2 false-positive patients were later found to have clinical myeloma and were within the normal range of renal function. Of the 16 patients with an abnormal κ-to-λ ratio and renal failure, 15 would be within the revised normal reference range, leaving 9 false-positives, 2 of whom eventually were found to have disease. With the application of the extended light chain range (as per Hutchison) for those patients with renal failure, 15 of the original 24 false-positives became true-negatives. Two of the false-positives become true-positives after they were subsequently diagnosed. Therefore, SFLC analysis detected disease in 22% of the revised false-positives when SPEP could not.

Table 2 lists the revised data after follow-up and renal failure correction. The strongest aspect of SFLC analysis remains its 95% specificity; its 69% sensitivity remains relatively constant. The test’s positive predictive value is 84%, and its negative predictive value is 90%. In veteran and other at-risk populations, SFLC analysis proves to be a very powerful tool on its own.

Conclusion

Both patient cases described in this article demonstrate the usefulness of SFLC analysis as an adjunct to SPEP. The authors propose SFLC testing for all patients who are undergoing MM screening with SPEP/IFE. In patients with renal failure, the expanded reference range seems to reduce erroneous false-positive results. Patients who have abnormal ratios should be followed up in clinic with repeat MM testing. It seems clear that, at the very least, SFLC analysis is a necessary adjunct to SPEP testing. However, SFLC stands on its own merit as well.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER website. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed July 11, 2016.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

3. Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Fermand JP, et al; International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Consensus recommendations for standard investigative workup: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Blood. 2011;117(18):4701-4705.

4. Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1437-1444.

5. Hutchison CA, Plant T, Drayson M, et al. Serum free light chain measurement

aids the diagnosis of myeloma in patients with severe renal failure.

BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:11.

6. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease

Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration

rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612.

7. McTaggart MP, Lindsay J, Kearney EM. Replacing urine protein electrophoresis

with serum free light chain analysis as a first-line test for detecting plasma

cell disorders offers increased diagnostic accuracy and potential health benefit

to patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140(6):890-897.

8. Abadie JM, Bankson DD. Assessment of serum free light chain assays for

plasma cell disorder screening in a Veterans Affairs population. Ann Clin Lab

Sci. 2006;36(2):157-162.

9. Kim HS, Kim HS, Shin KS, et al. Clinical comparisons of two free light chain

assays to immunofixation electrophoresis for detecting monoclonal gammopathy.

Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:647238.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER website. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed July 11, 2016.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

3. Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Fermand JP, et al; International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Consensus recommendations for standard investigative workup: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Blood. 2011;117(18):4701-4705.

4. Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1437-1444.

5. Hutchison CA, Plant T, Drayson M, et al. Serum free light chain measurement

aids the diagnosis of myeloma in patients with severe renal failure.

BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:11.

6. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease

Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration

rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612.

7. McTaggart MP, Lindsay J, Kearney EM. Replacing urine protein electrophoresis

with serum free light chain analysis as a first-line test for detecting plasma

cell disorders offers increased diagnostic accuracy and potential health benefit

to patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140(6):890-897.

8. Abadie JM, Bankson DD. Assessment of serum free light chain assays for

plasma cell disorder screening in a Veterans Affairs population. Ann Clin Lab

Sci. 2006;36(2):157-162.

9. Kim HS, Kim HS, Shin KS, et al. Clinical comparisons of two free light chain

assays to immunofixation electrophoresis for detecting monoclonal gammopathy.

Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:647238.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Pneumatic Tube-Induced Reverse Pseudohyperkalemia in a Patient With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Pseudohyperkalemia is a potentially dangerous phenomenon where falsely reported elevated potassium levels result in potentially unwarranted correction of potassium by sodium polystyrene or by dialysis in extreme cases. Overcorrection of potassium in a patient whose potassium is normal or low can lead to hypokalemia and potentially life-threatening consequences. Typical pseudohyperkalemia is thought to be a result of platelet-mediated release of potassium that occurs from the clotting process of a serum sample where no anticoagulant is present. As a result, pseudohyperkalemia is typically corrected when potassium is measured with a plasma sample where heparin and other preservatives are present in the collection tube.1

Reverse pseudohyperkalemia is seen in patients with leukemia and lymphoma with significant lymphocytosis when laboratory studies demonstrate falsely elevated potassium. In reverse pseudohyperkalemia the potassium level from a plasma sample is falsely elevated despite the presence of an anticoagulant, as the process is independent of platelet activation and occurs as a result of white blood cell (WBC) breakdown.2

For several decades, it has been suggested that the presence of heparin in tubes used to collect plasma is the cause of lysis of WBCs, presumably due to possible membrane fragility of these cells. Correction was recommended with the use of low-heparin-coated tubes.3 The other proposed theory for reverse pseudohyperkalemia is that lysis of WBCs is primarily due to procedural handling: Several case reports suggest that pneumatic tube transport likely plays a strong role, as well as other factors, such as the length of time to the laboratory.4-6

The authors report a case of a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who presented with significant reverse pseudohyperkalemia that later was determined to be dependent on pneumatic tube transport and independent of heparin.

Case Presentation

The patient, an 83-year-old man with a long history of asymptomatic CLL, was noted to have rapid WBC doubling time. His WBC counts had increased from 45 × 103/μL to 95 x 103/μL over the year preceding admission, then further increased to 300 x 103/μL in the month before admission.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed significant lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. The patient presented to the hospital for treatment with a planned first cycle of bendamustine alone and subsequent cycles of bendamustine and rituximab. His medical history included Prinzmetal angina, coronary artery disease, wet macular degeneration, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Notably, he had a documented history of hyperkalemia with potassium levels ranging from 4.7 mEq/L to 4.9 mEq/L over the previous year and was placed on a potassium-restricted diet.

On presentation, he reported no recent history of B symptoms of fever, night sweats, weight loss, and malaise. His labs oratory results showed an elevated potassium level of 6.1 mEq/L with repeated whole blood potassium of 8.2 mEq/L. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm, no noted T-wave abnormalities, and no conduction abnormalities. A physical exam was significant for normal muscle strength, cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly.

The patient was initially treated for hyperkalemia with insulin plus glucose and sodium polystyrene. He responded with mild improvement of his potassium level to 6.3 mEq/L, 5.6 mEq/L, and 5.1 mEq/L after receiving 5 doses of 30 g of polystyrene over multiple checks during a 24-hour period. Hemolysis results drawn at that time were unremarkable. It was noted that the patient had an elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 328 IU/L.

The following morning, his potassium level remained elevated at 6.2 mEq/L, but because the treatment team suspected pseudohyperkalemia, the decision at the time was to proceed with chemotherapy.

To evaluate this possibility, the authors attempted to correct for procedural handling resulting in unwanted WBC lysis. They reduced the lithium heparin in the collection from 81 IU of lithium heparin found in the green-mint collection tube and instead used an arterial blood gas (ABG) syringe that contained 23.5 IU of heparin and hand-carried the sample to the lab. The potassium value was 3.4 mEq/L in the sample collected in the ABG syringe, and a concurrent value collected by the standard method was 7.4 mEq/L. A repeated ECG was negative for any cardiac arrhythmias or conduction abnormalities. The subsequent 2 sets of potassium values were 3.9 mEq/L for the ABG syringe and 6.4 mEq/L for the standard heparinized tube, and 3.5 mEq/L and 5.8 mEq/L, respectively. The patient received the remainder of his chemotherapy, and there was no evidence of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS).

The following day, tumor lysis labs were collected in a low-heparin ABG syringe and a regular green-mint collection tube. Both samples were manually brought to the lab without pneumatic tube transport. Interestingly, the patient’s repeat potassium levels were 3.3 mEq/L and 3.1 mEq/L, respectively. Therefore, it was determined that the potassium level was not dependent on the presence of an anticoagulant. The following day the patient remained asymptomatic with normal potassium levels, and he was discharged on a normal cardiac diet. When he was evaluated in an outpatient setting a month later, the patient was found to have a normal potassium level at 4.3 mEq/L on a normal potassium diet.

Conclusion

In the hospital setting, pseudohyperkalemia is a potentially dangerous situation. Because the patient discussed here initially presented with potassium values as high as 8.2 mEq/L, treatment was warranted. However, given the presence of CLL with extreme leukocytosis and otherwise

normal clinical findings, suspicion for pseudohyperkalemia was high. Initial treatment of the elevated potassium levels, which were revealed to be borderline low later in his clinical course, may have had detrimental effects on his cardiac function if hypokalemia had been inadvertently exacerbated to a significant level. The authors bring this case to the attention of health care providers of patients with CLL because this patient had been chronically managed for hyperkalemia with a lowpotassium diet.

Further, this case confirms the importance of avoiding the use of pneumatic tubes to prevent WBC lysis in patients with significant malignant leukocytosis. Importantly, the authors were able to differentiate between postulated heparin-mediated lysis and pneumatictube usage. As the literature has suggested, the authors speculated that mechanical stress on chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells is the primary cause of pseudo-hyperkalemia.

Pneumatic tube use or mechanical manipulation seemed to cause unwanted WBC lysis in this case, as values in the standard 81 IU heparin tubes used in this case study could be corrected by manually transporting the tube to the lab. This suggests that the process is heparin-independent, although initial investigations on that effect focused on the use of low-heparin vials. The potassium correction also was supported by the correction of likely falsely elevated LDH, which normalized when samples were manually transported. This supports the mechanism of WBC lysis. The authors’ observations are in line with several recent reports where pneumatic tube use was suspected as the cause of reverse pseudohyperkalemia.4,5,7,8

During the authors’ monitoring of the patient for TLS, comparison of repeat values for potassium showed a significant difference of about 2.7 mEq/L between samples transported manually and samples sent via pneumatic tube (Figure). Similar elevations of values have been described in other case reports.1

Reverse pseudohyperkalemia is a phenomenon that should not be overlooked in the medical management of patients with CLL with leukocytosis, especially in asymptomatic chronic patients. Although initially the differences can be benign, as the tumor burden increases, the degree of falsely elevated potassium can increase to thresholds that lead to inappropriate management in an acute setting. To prevent mismanagement, the authors recommend placing precautionary flags with hospital laboratories so that if a patient with CLL has a high potassium draw, lab values are rechecked with hand-delivered samples. The authors hope that this case will highlight the importance of suspecting this diagnosis in patients with CLL and provide guidance on obtaining accurate labs to better manage these patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Avelar T. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Perm J. 2014;18(4):e150-e152.

2. Abraham B, Fakhar I, Tikaria A, et al. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in a leukemic patient. Clin Chem. 2008;54(2):449-451.

3. Singh PJ, Zawada ET, Santella RN. A case of “reverse” pseudohyperkalemia. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1997;23(1):58-61.

4. Garwicz D, Karlman M. Early recognition of reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples during leukemic hyperleukocytosis can prevent iatrogenic hypokalemia. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(18):1700-1702.

5. Garwicz D, Karlman M, Øra I. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples from a child with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with hyperleukocytosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(3-4):396-397.

6. Kintzel PE, Scott WL. Pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphoblastic leukemia and tumor lysis syndrome. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18(4):432-435.

7. Sindhu SK, Hix JK, Fricke W. Pseudohyperkalemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: phlebotomy sites and pneumatic tubes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(2):354-355.

8. Kellerman PS, Thornbery JM. Pseudohyperkalemia due to pneumatic tube transport in a leukemic patient. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):746-748

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Pseudohyperkalemia is a potentially dangerous phenomenon where falsely reported elevated potassium levels result in potentially unwarranted correction of potassium by sodium polystyrene or by dialysis in extreme cases. Overcorrection of potassium in a patient whose potassium is normal or low can lead to hypokalemia and potentially life-threatening consequences. Typical pseudohyperkalemia is thought to be a result of platelet-mediated release of potassium that occurs from the clotting process of a serum sample where no anticoagulant is present. As a result, pseudohyperkalemia is typically corrected when potassium is measured with a plasma sample where heparin and other preservatives are present in the collection tube.1

Reverse pseudohyperkalemia is seen in patients with leukemia and lymphoma with significant lymphocytosis when laboratory studies demonstrate falsely elevated potassium. In reverse pseudohyperkalemia the potassium level from a plasma sample is falsely elevated despite the presence of an anticoagulant, as the process is independent of platelet activation and occurs as a result of white blood cell (WBC) breakdown.2

For several decades, it has been suggested that the presence of heparin in tubes used to collect plasma is the cause of lysis of WBCs, presumably due to possible membrane fragility of these cells. Correction was recommended with the use of low-heparin-coated tubes.3 The other proposed theory for reverse pseudohyperkalemia is that lysis of WBCs is primarily due to procedural handling: Several case reports suggest that pneumatic tube transport likely plays a strong role, as well as other factors, such as the length of time to the laboratory.4-6

The authors report a case of a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who presented with significant reverse pseudohyperkalemia that later was determined to be dependent on pneumatic tube transport and independent of heparin.

Case Presentation

The patient, an 83-year-old man with a long history of asymptomatic CLL, was noted to have rapid WBC doubling time. His WBC counts had increased from 45 × 103/μL to 95 x 103/μL over the year preceding admission, then further increased to 300 x 103/μL in the month before admission.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed significant lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. The patient presented to the hospital for treatment with a planned first cycle of bendamustine alone and subsequent cycles of bendamustine and rituximab. His medical history included Prinzmetal angina, coronary artery disease, wet macular degeneration, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Notably, he had a documented history of hyperkalemia with potassium levels ranging from 4.7 mEq/L to 4.9 mEq/L over the previous year and was placed on a potassium-restricted diet.

On presentation, he reported no recent history of B symptoms of fever, night sweats, weight loss, and malaise. His labs oratory results showed an elevated potassium level of 6.1 mEq/L with repeated whole blood potassium of 8.2 mEq/L. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm, no noted T-wave abnormalities, and no conduction abnormalities. A physical exam was significant for normal muscle strength, cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly.

The patient was initially treated for hyperkalemia with insulin plus glucose and sodium polystyrene. He responded with mild improvement of his potassium level to 6.3 mEq/L, 5.6 mEq/L, and 5.1 mEq/L after receiving 5 doses of 30 g of polystyrene over multiple checks during a 24-hour period. Hemolysis results drawn at that time were unremarkable. It was noted that the patient had an elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 328 IU/L.

The following morning, his potassium level remained elevated at 6.2 mEq/L, but because the treatment team suspected pseudohyperkalemia, the decision at the time was to proceed with chemotherapy.

To evaluate this possibility, the authors attempted to correct for procedural handling resulting in unwanted WBC lysis. They reduced the lithium heparin in the collection from 81 IU of lithium heparin found in the green-mint collection tube and instead used an arterial blood gas (ABG) syringe that contained 23.5 IU of heparin and hand-carried the sample to the lab. The potassium value was 3.4 mEq/L in the sample collected in the ABG syringe, and a concurrent value collected by the standard method was 7.4 mEq/L. A repeated ECG was negative for any cardiac arrhythmias or conduction abnormalities. The subsequent 2 sets of potassium values were 3.9 mEq/L for the ABG syringe and 6.4 mEq/L for the standard heparinized tube, and 3.5 mEq/L and 5.8 mEq/L, respectively. The patient received the remainder of his chemotherapy, and there was no evidence of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS).

The following day, tumor lysis labs were collected in a low-heparin ABG syringe and a regular green-mint collection tube. Both samples were manually brought to the lab without pneumatic tube transport. Interestingly, the patient’s repeat potassium levels were 3.3 mEq/L and 3.1 mEq/L, respectively. Therefore, it was determined that the potassium level was not dependent on the presence of an anticoagulant. The following day the patient remained asymptomatic with normal potassium levels, and he was discharged on a normal cardiac diet. When he was evaluated in an outpatient setting a month later, the patient was found to have a normal potassium level at 4.3 mEq/L on a normal potassium diet.

Conclusion

In the hospital setting, pseudohyperkalemia is a potentially dangerous situation. Because the patient discussed here initially presented with potassium values as high as 8.2 mEq/L, treatment was warranted. However, given the presence of CLL with extreme leukocytosis and otherwise

normal clinical findings, suspicion for pseudohyperkalemia was high. Initial treatment of the elevated potassium levels, which were revealed to be borderline low later in his clinical course, may have had detrimental effects on his cardiac function if hypokalemia had been inadvertently exacerbated to a significant level. The authors bring this case to the attention of health care providers of patients with CLL because this patient had been chronically managed for hyperkalemia with a lowpotassium diet.

Further, this case confirms the importance of avoiding the use of pneumatic tubes to prevent WBC lysis in patients with significant malignant leukocytosis. Importantly, the authors were able to differentiate between postulated heparin-mediated lysis and pneumatictube usage. As the literature has suggested, the authors speculated that mechanical stress on chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells is the primary cause of pseudo-hyperkalemia.

Pneumatic tube use or mechanical manipulation seemed to cause unwanted WBC lysis in this case, as values in the standard 81 IU heparin tubes used in this case study could be corrected by manually transporting the tube to the lab. This suggests that the process is heparin-independent, although initial investigations on that effect focused on the use of low-heparin vials. The potassium correction also was supported by the correction of likely falsely elevated LDH, which normalized when samples were manually transported. This supports the mechanism of WBC lysis. The authors’ observations are in line with several recent reports where pneumatic tube use was suspected as the cause of reverse pseudohyperkalemia.4,5,7,8

During the authors’ monitoring of the patient for TLS, comparison of repeat values for potassium showed a significant difference of about 2.7 mEq/L between samples transported manually and samples sent via pneumatic tube (Figure). Similar elevations of values have been described in other case reports.1

Reverse pseudohyperkalemia is a phenomenon that should not be overlooked in the medical management of patients with CLL with leukocytosis, especially in asymptomatic chronic patients. Although initially the differences can be benign, as the tumor burden increases, the degree of falsely elevated potassium can increase to thresholds that lead to inappropriate management in an acute setting. To prevent mismanagement, the authors recommend placing precautionary flags with hospital laboratories so that if a patient with CLL has a high potassium draw, lab values are rechecked with hand-delivered samples. The authors hope that this case will highlight the importance of suspecting this diagnosis in patients with CLL and provide guidance on obtaining accurate labs to better manage these patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Pseudohyperkalemia is a potentially dangerous phenomenon where falsely reported elevated potassium levels result in potentially unwarranted correction of potassium by sodium polystyrene or by dialysis in extreme cases. Overcorrection of potassium in a patient whose potassium is normal or low can lead to hypokalemia and potentially life-threatening consequences. Typical pseudohyperkalemia is thought to be a result of platelet-mediated release of potassium that occurs from the clotting process of a serum sample where no anticoagulant is present. As a result, pseudohyperkalemia is typically corrected when potassium is measured with a plasma sample where heparin and other preservatives are present in the collection tube.1

Reverse pseudohyperkalemia is seen in patients with leukemia and lymphoma with significant lymphocytosis when laboratory studies demonstrate falsely elevated potassium. In reverse pseudohyperkalemia the potassium level from a plasma sample is falsely elevated despite the presence of an anticoagulant, as the process is independent of platelet activation and occurs as a result of white blood cell (WBC) breakdown.2

For several decades, it has been suggested that the presence of heparin in tubes used to collect plasma is the cause of lysis of WBCs, presumably due to possible membrane fragility of these cells. Correction was recommended with the use of low-heparin-coated tubes.3 The other proposed theory for reverse pseudohyperkalemia is that lysis of WBCs is primarily due to procedural handling: Several case reports suggest that pneumatic tube transport likely plays a strong role, as well as other factors, such as the length of time to the laboratory.4-6

The authors report a case of a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who presented with significant reverse pseudohyperkalemia that later was determined to be dependent on pneumatic tube transport and independent of heparin.

Case Presentation

The patient, an 83-year-old man with a long history of asymptomatic CLL, was noted to have rapid WBC doubling time. His WBC counts had increased from 45 × 103/μL to 95 x 103/μL over the year preceding admission, then further increased to 300 x 103/μL in the month before admission.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed significant lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. The patient presented to the hospital for treatment with a planned first cycle of bendamustine alone and subsequent cycles of bendamustine and rituximab. His medical history included Prinzmetal angina, coronary artery disease, wet macular degeneration, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Notably, he had a documented history of hyperkalemia with potassium levels ranging from 4.7 mEq/L to 4.9 mEq/L over the previous year and was placed on a potassium-restricted diet.

On presentation, he reported no recent history of B symptoms of fever, night sweats, weight loss, and malaise. His labs oratory results showed an elevated potassium level of 6.1 mEq/L with repeated whole blood potassium of 8.2 mEq/L. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm, no noted T-wave abnormalities, and no conduction abnormalities. A physical exam was significant for normal muscle strength, cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly.

The patient was initially treated for hyperkalemia with insulin plus glucose and sodium polystyrene. He responded with mild improvement of his potassium level to 6.3 mEq/L, 5.6 mEq/L, and 5.1 mEq/L after receiving 5 doses of 30 g of polystyrene over multiple checks during a 24-hour period. Hemolysis results drawn at that time were unremarkable. It was noted that the patient had an elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 328 IU/L.

The following morning, his potassium level remained elevated at 6.2 mEq/L, but because the treatment team suspected pseudohyperkalemia, the decision at the time was to proceed with chemotherapy.

To evaluate this possibility, the authors attempted to correct for procedural handling resulting in unwanted WBC lysis. They reduced the lithium heparin in the collection from 81 IU of lithium heparin found in the green-mint collection tube and instead used an arterial blood gas (ABG) syringe that contained 23.5 IU of heparin and hand-carried the sample to the lab. The potassium value was 3.4 mEq/L in the sample collected in the ABG syringe, and a concurrent value collected by the standard method was 7.4 mEq/L. A repeated ECG was negative for any cardiac arrhythmias or conduction abnormalities. The subsequent 2 sets of potassium values were 3.9 mEq/L for the ABG syringe and 6.4 mEq/L for the standard heparinized tube, and 3.5 mEq/L and 5.8 mEq/L, respectively. The patient received the remainder of his chemotherapy, and there was no evidence of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS).

The following day, tumor lysis labs were collected in a low-heparin ABG syringe and a regular green-mint collection tube. Both samples were manually brought to the lab without pneumatic tube transport. Interestingly, the patient’s repeat potassium levels were 3.3 mEq/L and 3.1 mEq/L, respectively. Therefore, it was determined that the potassium level was not dependent on the presence of an anticoagulant. The following day the patient remained asymptomatic with normal potassium levels, and he was discharged on a normal cardiac diet. When he was evaluated in an outpatient setting a month later, the patient was found to have a normal potassium level at 4.3 mEq/L on a normal potassium diet.

Conclusion

In the hospital setting, pseudohyperkalemia is a potentially dangerous situation. Because the patient discussed here initially presented with potassium values as high as 8.2 mEq/L, treatment was warranted. However, given the presence of CLL with extreme leukocytosis and otherwise

normal clinical findings, suspicion for pseudohyperkalemia was high. Initial treatment of the elevated potassium levels, which were revealed to be borderline low later in his clinical course, may have had detrimental effects on his cardiac function if hypokalemia had been inadvertently exacerbated to a significant level. The authors bring this case to the attention of health care providers of patients with CLL because this patient had been chronically managed for hyperkalemia with a lowpotassium diet.

Further, this case confirms the importance of avoiding the use of pneumatic tubes to prevent WBC lysis in patients with significant malignant leukocytosis. Importantly, the authors were able to differentiate between postulated heparin-mediated lysis and pneumatictube usage. As the literature has suggested, the authors speculated that mechanical stress on chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells is the primary cause of pseudo-hyperkalemia.

Pneumatic tube use or mechanical manipulation seemed to cause unwanted WBC lysis in this case, as values in the standard 81 IU heparin tubes used in this case study could be corrected by manually transporting the tube to the lab. This suggests that the process is heparin-independent, although initial investigations on that effect focused on the use of low-heparin vials. The potassium correction also was supported by the correction of likely falsely elevated LDH, which normalized when samples were manually transported. This supports the mechanism of WBC lysis. The authors’ observations are in line with several recent reports where pneumatic tube use was suspected as the cause of reverse pseudohyperkalemia.4,5,7,8

During the authors’ monitoring of the patient for TLS, comparison of repeat values for potassium showed a significant difference of about 2.7 mEq/L between samples transported manually and samples sent via pneumatic tube (Figure). Similar elevations of values have been described in other case reports.1

Reverse pseudohyperkalemia is a phenomenon that should not be overlooked in the medical management of patients with CLL with leukocytosis, especially in asymptomatic chronic patients. Although initially the differences can be benign, as the tumor burden increases, the degree of falsely elevated potassium can increase to thresholds that lead to inappropriate management in an acute setting. To prevent mismanagement, the authors recommend placing precautionary flags with hospital laboratories so that if a patient with CLL has a high potassium draw, lab values are rechecked with hand-delivered samples. The authors hope that this case will highlight the importance of suspecting this diagnosis in patients with CLL and provide guidance on obtaining accurate labs to better manage these patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Avelar T. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Perm J. 2014;18(4):e150-e152.

2. Abraham B, Fakhar I, Tikaria A, et al. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in a leukemic patient. Clin Chem. 2008;54(2):449-451.

3. Singh PJ, Zawada ET, Santella RN. A case of “reverse” pseudohyperkalemia. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1997;23(1):58-61.

4. Garwicz D, Karlman M. Early recognition of reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples during leukemic hyperleukocytosis can prevent iatrogenic hypokalemia. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(18):1700-1702.

5. Garwicz D, Karlman M, Øra I. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples from a child with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with hyperleukocytosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(3-4):396-397.

6. Kintzel PE, Scott WL. Pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphoblastic leukemia and tumor lysis syndrome. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18(4):432-435.

7. Sindhu SK, Hix JK, Fricke W. Pseudohyperkalemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: phlebotomy sites and pneumatic tubes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(2):354-355.

8. Kellerman PS, Thornbery JM. Pseudohyperkalemia due to pneumatic tube transport in a leukemic patient. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):746-748

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. Avelar T. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Perm J. 2014;18(4):e150-e152.

2. Abraham B, Fakhar I, Tikaria A, et al. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in a leukemic patient. Clin Chem. 2008;54(2):449-451.

3. Singh PJ, Zawada ET, Santella RN. A case of “reverse” pseudohyperkalemia. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1997;23(1):58-61.

4. Garwicz D, Karlman M. Early recognition of reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples during leukemic hyperleukocytosis can prevent iatrogenic hypokalemia. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(18):1700-1702.

5. Garwicz D, Karlman M, Øra I. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples from a child with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with hyperleukocytosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(3-4):396-397.

6. Kintzel PE, Scott WL. Pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphoblastic leukemia and tumor lysis syndrome. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18(4):432-435.

7. Sindhu SK, Hix JK, Fricke W. Pseudohyperkalemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: phlebotomy sites and pneumatic tubes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(2):354-355.

8. Kellerman PS, Thornbery JM. Pseudohyperkalemia due to pneumatic tube transport in a leukemic patient. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):746-748

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Daratumumab Effective in Combo Regimen

Adding daratumumab to bortezomib (a protease inhibitor [PI]) and dexamethasone reduces the risk of disease progression or death by 61% in patients with multiple myeloma (MM), compared with bortezomib and dexamethasone alone, according to an interim analysis of phase 3 trial results.

Related: Multiple Myeloma: Updates on Diagnosis and Management

Daratumumab is a biologic that targets CD38, a surface protein that is highly expressed across MM cells, regardless of disease stage. “CD38 is the most important tumor antigen on myeloma plasma cells,” said Antonio Palumbo, MD, University of Torino, Italy, who presented the study findings at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in June. Daratumumab has more than 1 immune-mediated mechanism of action and both direct and indirect antimyeloma activity: It depletes CD38+ immunosuppressive regulatory cells and promotes T-cell expansion and activation, all while directly killing myeloma cells.

The multinational study (CASTOR) included 498 patients with MM who had received a median of 2 prior lines of therapy: bortezomib, an immunomodulatory agent, or a PI and immunomodulatory agent. Prior treatments had been unsuccessful in one-third of patients. In this study, researchers randomly assigned 251 patients to combination treatment with daratumumab.

Related: Treating Patients With Multiple Myeloma in the VA

Daratumumab significantly increased the overall response rate (83% vs 63%) and doubled rates of complete response or better (19% vs 9%). It also doubled the rates of very good partial response (59% vs 29%). The combination therapy met the primary endpoint of improved progression-free survival at a median follow-up of 7.4 months (60.7% in the combination arm, compared with 26.9%). The treatment was unblinded after meeting the primary endpoint.

The treatment benefits of the combination regimen were maintained across clinically relevant subgroups, the researchers said. The most common adverse effects were thrombocytopenia ,sensory peripheral neuropathy, anaemia, and diarrhea.

“These compelling phase 3 results demonstrate that a regimen built on daratumumab deepens clinical responses and help to underscore its potential for multiple myeloma patients who have been previously treated,” said Dr. Palumbo.

Related: A Mysterious Massive Hemorrhage

In a discussion of the study, Paul Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, praised the study as “outstanding” and “potentially practice changing.” However, another panel member noted that with an added cost of more than $10,000 a month, the treatment could be out of reach for many.

Adding daratumumab to bortezomib (a protease inhibitor [PI]) and dexamethasone reduces the risk of disease progression or death by 61% in patients with multiple myeloma (MM), compared with bortezomib and dexamethasone alone, according to an interim analysis of phase 3 trial results.

Related: Multiple Myeloma: Updates on Diagnosis and Management

Daratumumab is a biologic that targets CD38, a surface protein that is highly expressed across MM cells, regardless of disease stage. “CD38 is the most important tumor antigen on myeloma plasma cells,” said Antonio Palumbo, MD, University of Torino, Italy, who presented the study findings at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in June. Daratumumab has more than 1 immune-mediated mechanism of action and both direct and indirect antimyeloma activity: It depletes CD38+ immunosuppressive regulatory cells and promotes T-cell expansion and activation, all while directly killing myeloma cells.

The multinational study (CASTOR) included 498 patients with MM who had received a median of 2 prior lines of therapy: bortezomib, an immunomodulatory agent, or a PI and immunomodulatory agent. Prior treatments had been unsuccessful in one-third of patients. In this study, researchers randomly assigned 251 patients to combination treatment with daratumumab.

Related: Treating Patients With Multiple Myeloma in the VA

Daratumumab significantly increased the overall response rate (83% vs 63%) and doubled rates of complete response or better (19% vs 9%). It also doubled the rates of very good partial response (59% vs 29%). The combination therapy met the primary endpoint of improved progression-free survival at a median follow-up of 7.4 months (60.7% in the combination arm, compared with 26.9%). The treatment was unblinded after meeting the primary endpoint.

The treatment benefits of the combination regimen were maintained across clinically relevant subgroups, the researchers said. The most common adverse effects were thrombocytopenia ,sensory peripheral neuropathy, anaemia, and diarrhea.

“These compelling phase 3 results demonstrate that a regimen built on daratumumab deepens clinical responses and help to underscore its potential for multiple myeloma patients who have been previously treated,” said Dr. Palumbo.

Related: A Mysterious Massive Hemorrhage

In a discussion of the study, Paul Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, praised the study as “outstanding” and “potentially practice changing.” However, another panel member noted that with an added cost of more than $10,000 a month, the treatment could be out of reach for many.

Adding daratumumab to bortezomib (a protease inhibitor [PI]) and dexamethasone reduces the risk of disease progression or death by 61% in patients with multiple myeloma (MM), compared with bortezomib and dexamethasone alone, according to an interim analysis of phase 3 trial results.

Related: Multiple Myeloma: Updates on Diagnosis and Management

Daratumumab is a biologic that targets CD38, a surface protein that is highly expressed across MM cells, regardless of disease stage. “CD38 is the most important tumor antigen on myeloma plasma cells,” said Antonio Palumbo, MD, University of Torino, Italy, who presented the study findings at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in June. Daratumumab has more than 1 immune-mediated mechanism of action and both direct and indirect antimyeloma activity: It depletes CD38+ immunosuppressive regulatory cells and promotes T-cell expansion and activation, all while directly killing myeloma cells.

The multinational study (CASTOR) included 498 patients with MM who had received a median of 2 prior lines of therapy: bortezomib, an immunomodulatory agent, or a PI and immunomodulatory agent. Prior treatments had been unsuccessful in one-third of patients. In this study, researchers randomly assigned 251 patients to combination treatment with daratumumab.

Related: Treating Patients With Multiple Myeloma in the VA

Daratumumab significantly increased the overall response rate (83% vs 63%) and doubled rates of complete response or better (19% vs 9%). It also doubled the rates of very good partial response (59% vs 29%). The combination therapy met the primary endpoint of improved progression-free survival at a median follow-up of 7.4 months (60.7% in the combination arm, compared with 26.9%). The treatment was unblinded after meeting the primary endpoint.

The treatment benefits of the combination regimen were maintained across clinically relevant subgroups, the researchers said. The most common adverse effects were thrombocytopenia ,sensory peripheral neuropathy, anaemia, and diarrhea.

“These compelling phase 3 results demonstrate that a regimen built on daratumumab deepens clinical responses and help to underscore its potential for multiple myeloma patients who have been previously treated,” said Dr. Palumbo.

Related: A Mysterious Massive Hemorrhage

In a discussion of the study, Paul Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, praised the study as “outstanding” and “potentially practice changing.” However, another panel member noted that with an added cost of more than $10,000 a month, the treatment could be out of reach for many.

Sustained Remissions After Discontinuation of Ibrutinib in Relapsed/Refractory CLL: A Basis for Reducing Drug Toxicity and Treatment Costs?

In contrast to traditional chemotherapy, patients responding to biological or targeted therapies often are treated indefinitely until progression or toxicity. This therapeutic model, however, increases treatment costs, may induce greater toxicity and theoretically could select for earlier emergence of drug resistance. Moreover, little data are available regarding the outcomes of patients who discontinue targeted therapies after achieving remission. In this regard, we report 2 patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who chose to stop therapy unrelated to toxicity or disease status after the induction of remission by the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.

Patient A started ibrutinib for progressive CLL at an absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 137,000 mm3 and recurrent hemolytic anemia. After 5 months, the hemolysis had resolved (Hgb 15.6 g/dL), while the ALC had declined to 9,200 mm3. Treatment was then interrupted due to patient preference. One month after drug discontinuation, the ALC was in the normal range at 1,400 mm3 and remained within or near the normal range for a total of 12 months. Two months later, the ALC was again markedly elevated at 68,000 mm3 and anemia recurred. The patient then agreed to restart ibrutinib. After 4 months of re-treatment, he has had prompt resolution of the anemia and achieved a partial remission thus far.

Patient B was started on ibrutinib for a rising ALC (26,000 mm3) and severe hemolytic anemia. After 9 months of treatment, the hemoglobin was 13 g/dL and the ALC was in the normal range at 3,300 mm3. Due to unrelated medical problems, ibrutinib therapy was stopped. Currently, 6 months since drug discontinuation, the ALC remains in the normal range, and no other signs of CLL are present.

These clinical observations suggest that interruption of ibrutinib may be feasible in at least some CLL patients who achieve remission. Even if flow cytometry were performed at monthly intervals to detect early recurrence and ensure prompt re-institution of therapy, the cost savings would still be considerable. Of course, clinical trials will be necessary to confirm equivalent long-term efficacy and overall survival for intermittent versus continuous ibrutinib therapy in CLL.

In contrast to traditional chemotherapy, patients responding to biological or targeted therapies often are treated indefinitely until progression or toxicity. This therapeutic model, however, increases treatment costs, may induce greater toxicity and theoretically could select for earlier emergence of drug resistance. Moreover, little data are available regarding the outcomes of patients who discontinue targeted therapies after achieving remission. In this regard, we report 2 patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who chose to stop therapy unrelated to toxicity or disease status after the induction of remission by the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.

Patient A started ibrutinib for progressive CLL at an absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 137,000 mm3 and recurrent hemolytic anemia. After 5 months, the hemolysis had resolved (Hgb 15.6 g/dL), while the ALC had declined to 9,200 mm3. Treatment was then interrupted due to patient preference. One month after drug discontinuation, the ALC was in the normal range at 1,400 mm3 and remained within or near the normal range for a total of 12 months. Two months later, the ALC was again markedly elevated at 68,000 mm3 and anemia recurred. The patient then agreed to restart ibrutinib. After 4 months of re-treatment, he has had prompt resolution of the anemia and achieved a partial remission thus far.

Patient B was started on ibrutinib for a rising ALC (26,000 mm3) and severe hemolytic anemia. After 9 months of treatment, the hemoglobin was 13 g/dL and the ALC was in the normal range at 3,300 mm3. Due to unrelated medical problems, ibrutinib therapy was stopped. Currently, 6 months since drug discontinuation, the ALC remains in the normal range, and no other signs of CLL are present.

These clinical observations suggest that interruption of ibrutinib may be feasible in at least some CLL patients who achieve remission. Even if flow cytometry were performed at monthly intervals to detect early recurrence and ensure prompt re-institution of therapy, the cost savings would still be considerable. Of course, clinical trials will be necessary to confirm equivalent long-term efficacy and overall survival for intermittent versus continuous ibrutinib therapy in CLL.

In contrast to traditional chemotherapy, patients responding to biological or targeted therapies often are treated indefinitely until progression or toxicity. This therapeutic model, however, increases treatment costs, may induce greater toxicity and theoretically could select for earlier emergence of drug resistance. Moreover, little data are available regarding the outcomes of patients who discontinue targeted therapies after achieving remission. In this regard, we report 2 patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who chose to stop therapy unrelated to toxicity or disease status after the induction of remission by the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.