User login

Liquid biopsy a valuable tool for detecting, monitoring HCC

Liquid biopsy using circulating tumor (ctDNA) detection and profiling is a valuable tool for clinicians in monitoring hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly in monitoring progression, researchers wrote in a recent review.

Details of the review, led by co–first authors Xueying Lyu and Yu-Man Tsui, both of the department of pathology and State Key Laboratory of Liver Research at the University of Hong Kong, were published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Because there are few treatment options for advanced-stage liver cancer, scientists are searching for noninvasive ways to detect liver cancer before is progresses. Liver resection is the primary treatment for HCC, but the recurrence rate is high. Early detection increases the ability to identify relevant molecular-targeted drugs and helps predict patient response.

There is growing interest in noninvasive circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as well as in ctDNA – both are part of promising strategies to test circulating DNA in the bloodstream. Together with other circulating biomarkers, they are called liquid biopsy.

HCC can be detected noninvasively by detecting plasma ctDNA released from dying cancer cells. Detection depends on determining whether the circulating tumor DNA has the same molecular alterations as its tumor source. cfDNA contains genomic DNA from different tumor clones or tumors from different sites within a patient to help real-time monitoring of tumor progression.

Barriers to widespread clinical use of liquid biopsy include lack of standardization of the collection process. Procedures differ across health systems on how much blood should be collected, which tubes should be used for collection and how samples should be stored and shipped. The study authors suggested that “specialized tubes can be used for blood sample collection to reduce the chance of white blood cell rupture and genomic DNA contamination from the damaged white blood cells.”

Further research is needed

The study findings indicated that some aspects of liquid biopsy with cfDNA/ctDNA still need further exploration. For example, the effects of tumor vascularization, tumor aggressiveness, metabolic activity, and cell death mechanism on the dynamics of ctDNA in the bloodstream need to be identified.

It’s not yet clear how cfDNA is released into the bloodstream. Actively released cfDNA from the tumor may convey a different message from cfDNA released passively from dying cells upon treatment. The first represents treatment-resistant cells/subclones while the second represents treatment-responsive cells/subclones. Moreover, it is difficult to detect ctDNA mutation in early stage cancers that have lower tumor burden.

The investigators wrote: “The contributions of cfDNA from apoptosis, necrosis, autophagic cell death, and active release at different time points during disease progression, treatment response, and resistance appearance are poorly understood and will affect interpretation of the clinical observation in cfDNA assays.” A lower limit of detection needs to be determined and a standard curve set so that researchers can quantify the allelic frequencies of the mutants in cfDNA and avoid false-negative detection.

They urged establishing external quality assurance to verify laboratory performance, the proficiency in the cfDNA diagnostic test, and interpretation of results to identify errors in sampling, procedures, and decision making. Legal liability and cost effectiveness of using plasma cfDNA in treatment decisions also need to be considered.

The researchers wrote that, to better understand how ctDNA/cfDNA can be used to complement precision medicine in liver cancer, large multicenter cohorts and long-term follow-up are needed to compare ctDNA-guided decision-making against standard treatment without guidance from ctDNA profiling.

The authors disclosed having no conflicts of interest.

Detection and characterization of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is one of the major forms of liquid biopsy. Because ctDNA can reflect molecular features of cancer tissues, it is considered an ideal alternative to tissue biopsy. Furthermore, it can overcome the limitation of tumor tissue biopsies such as bleeding, needle tract seeding, and sampling error.

Currently, several large biomarker trials of ctDNA for early HCC detection are underway. Once its accuracy is established in phase 3-4 biomarker studies, the role of ctDNA in the context of the existing surveillance program should be further defined. As the combination of ctDNA and other orthogonal circulating biomarkers was shown to enhance the performance, future research should explore biomarker panels that include ctDNA and other promising markers to maximize performance. Predictive biomarkers for treatment response is an unmet need in HCC. Investigating the role of a specific ctDNA marker panel as a predictor of immunotherapy responsiveness would be of great interest and is under active investigation.

Ju Dong Yang, MD, is with the Karsh Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases in the department of medicine, with the Comprehensive Transplant Center, and with the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. He disclosed providing consulting services for Exact Sciences and Exelixis and Eisai.

Detection and characterization of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is one of the major forms of liquid biopsy. Because ctDNA can reflect molecular features of cancer tissues, it is considered an ideal alternative to tissue biopsy. Furthermore, it can overcome the limitation of tumor tissue biopsies such as bleeding, needle tract seeding, and sampling error.

Currently, several large biomarker trials of ctDNA for early HCC detection are underway. Once its accuracy is established in phase 3-4 biomarker studies, the role of ctDNA in the context of the existing surveillance program should be further defined. As the combination of ctDNA and other orthogonal circulating biomarkers was shown to enhance the performance, future research should explore biomarker panels that include ctDNA and other promising markers to maximize performance. Predictive biomarkers for treatment response is an unmet need in HCC. Investigating the role of a specific ctDNA marker panel as a predictor of immunotherapy responsiveness would be of great interest and is under active investigation.

Ju Dong Yang, MD, is with the Karsh Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases in the department of medicine, with the Comprehensive Transplant Center, and with the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. He disclosed providing consulting services for Exact Sciences and Exelixis and Eisai.

Detection and characterization of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is one of the major forms of liquid biopsy. Because ctDNA can reflect molecular features of cancer tissues, it is considered an ideal alternative to tissue biopsy. Furthermore, it can overcome the limitation of tumor tissue biopsies such as bleeding, needle tract seeding, and sampling error.

Currently, several large biomarker trials of ctDNA for early HCC detection are underway. Once its accuracy is established in phase 3-4 biomarker studies, the role of ctDNA in the context of the existing surveillance program should be further defined. As the combination of ctDNA and other orthogonal circulating biomarkers was shown to enhance the performance, future research should explore biomarker panels that include ctDNA and other promising markers to maximize performance. Predictive biomarkers for treatment response is an unmet need in HCC. Investigating the role of a specific ctDNA marker panel as a predictor of immunotherapy responsiveness would be of great interest and is under active investigation.

Ju Dong Yang, MD, is with the Karsh Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases in the department of medicine, with the Comprehensive Transplant Center, and with the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. He disclosed providing consulting services for Exact Sciences and Exelixis and Eisai.

Liquid biopsy using circulating tumor (ctDNA) detection and profiling is a valuable tool for clinicians in monitoring hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly in monitoring progression, researchers wrote in a recent review.

Details of the review, led by co–first authors Xueying Lyu and Yu-Man Tsui, both of the department of pathology and State Key Laboratory of Liver Research at the University of Hong Kong, were published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Because there are few treatment options for advanced-stage liver cancer, scientists are searching for noninvasive ways to detect liver cancer before is progresses. Liver resection is the primary treatment for HCC, but the recurrence rate is high. Early detection increases the ability to identify relevant molecular-targeted drugs and helps predict patient response.

There is growing interest in noninvasive circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as well as in ctDNA – both are part of promising strategies to test circulating DNA in the bloodstream. Together with other circulating biomarkers, they are called liquid biopsy.

HCC can be detected noninvasively by detecting plasma ctDNA released from dying cancer cells. Detection depends on determining whether the circulating tumor DNA has the same molecular alterations as its tumor source. cfDNA contains genomic DNA from different tumor clones or tumors from different sites within a patient to help real-time monitoring of tumor progression.

Barriers to widespread clinical use of liquid biopsy include lack of standardization of the collection process. Procedures differ across health systems on how much blood should be collected, which tubes should be used for collection and how samples should be stored and shipped. The study authors suggested that “specialized tubes can be used for blood sample collection to reduce the chance of white blood cell rupture and genomic DNA contamination from the damaged white blood cells.”

Further research is needed

The study findings indicated that some aspects of liquid biopsy with cfDNA/ctDNA still need further exploration. For example, the effects of tumor vascularization, tumor aggressiveness, metabolic activity, and cell death mechanism on the dynamics of ctDNA in the bloodstream need to be identified.

It’s not yet clear how cfDNA is released into the bloodstream. Actively released cfDNA from the tumor may convey a different message from cfDNA released passively from dying cells upon treatment. The first represents treatment-resistant cells/subclones while the second represents treatment-responsive cells/subclones. Moreover, it is difficult to detect ctDNA mutation in early stage cancers that have lower tumor burden.

The investigators wrote: “The contributions of cfDNA from apoptosis, necrosis, autophagic cell death, and active release at different time points during disease progression, treatment response, and resistance appearance are poorly understood and will affect interpretation of the clinical observation in cfDNA assays.” A lower limit of detection needs to be determined and a standard curve set so that researchers can quantify the allelic frequencies of the mutants in cfDNA and avoid false-negative detection.

They urged establishing external quality assurance to verify laboratory performance, the proficiency in the cfDNA diagnostic test, and interpretation of results to identify errors in sampling, procedures, and decision making. Legal liability and cost effectiveness of using plasma cfDNA in treatment decisions also need to be considered.

The researchers wrote that, to better understand how ctDNA/cfDNA can be used to complement precision medicine in liver cancer, large multicenter cohorts and long-term follow-up are needed to compare ctDNA-guided decision-making against standard treatment without guidance from ctDNA profiling.

The authors disclosed having no conflicts of interest.

Liquid biopsy using circulating tumor (ctDNA) detection and profiling is a valuable tool for clinicians in monitoring hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly in monitoring progression, researchers wrote in a recent review.

Details of the review, led by co–first authors Xueying Lyu and Yu-Man Tsui, both of the department of pathology and State Key Laboratory of Liver Research at the University of Hong Kong, were published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Because there are few treatment options for advanced-stage liver cancer, scientists are searching for noninvasive ways to detect liver cancer before is progresses. Liver resection is the primary treatment for HCC, but the recurrence rate is high. Early detection increases the ability to identify relevant molecular-targeted drugs and helps predict patient response.

There is growing interest in noninvasive circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as well as in ctDNA – both are part of promising strategies to test circulating DNA in the bloodstream. Together with other circulating biomarkers, they are called liquid biopsy.

HCC can be detected noninvasively by detecting plasma ctDNA released from dying cancer cells. Detection depends on determining whether the circulating tumor DNA has the same molecular alterations as its tumor source. cfDNA contains genomic DNA from different tumor clones or tumors from different sites within a patient to help real-time monitoring of tumor progression.

Barriers to widespread clinical use of liquid biopsy include lack of standardization of the collection process. Procedures differ across health systems on how much blood should be collected, which tubes should be used for collection and how samples should be stored and shipped. The study authors suggested that “specialized tubes can be used for blood sample collection to reduce the chance of white blood cell rupture and genomic DNA contamination from the damaged white blood cells.”

Further research is needed

The study findings indicated that some aspects of liquid biopsy with cfDNA/ctDNA still need further exploration. For example, the effects of tumor vascularization, tumor aggressiveness, metabolic activity, and cell death mechanism on the dynamics of ctDNA in the bloodstream need to be identified.

It’s not yet clear how cfDNA is released into the bloodstream. Actively released cfDNA from the tumor may convey a different message from cfDNA released passively from dying cells upon treatment. The first represents treatment-resistant cells/subclones while the second represents treatment-responsive cells/subclones. Moreover, it is difficult to detect ctDNA mutation in early stage cancers that have lower tumor burden.

The investigators wrote: “The contributions of cfDNA from apoptosis, necrosis, autophagic cell death, and active release at different time points during disease progression, treatment response, and resistance appearance are poorly understood and will affect interpretation of the clinical observation in cfDNA assays.” A lower limit of detection needs to be determined and a standard curve set so that researchers can quantify the allelic frequencies of the mutants in cfDNA and avoid false-negative detection.

They urged establishing external quality assurance to verify laboratory performance, the proficiency in the cfDNA diagnostic test, and interpretation of results to identify errors in sampling, procedures, and decision making. Legal liability and cost effectiveness of using plasma cfDNA in treatment decisions also need to be considered.

The researchers wrote that, to better understand how ctDNA/cfDNA can be used to complement precision medicine in liver cancer, large multicenter cohorts and long-term follow-up are needed to compare ctDNA-guided decision-making against standard treatment without guidance from ctDNA profiling.

The authors disclosed having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Can pickle juice help ease cirrhotic cramps?

In the trial, patients with cirrhotic cramps who sipped pickle brine at the onset of a muscle cramp saw a significant decrease in cramp severity relative to peers who sipped tap water when the cramp hit.

“The acid (vinegar) in the brine triggers a nerve reflex to stop the cramp when it hits the throat. This is why only a sip is needed,” lead investigator Elliot Tapper, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told this news organization. The study was published online April 13 in American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Common and bothersome

Cramps are common in adults with cirrhosis, irrespective of disease severity. They can sometimes last for hours, and treatment options are limited.

In a prior study, 1 tablespoon of pickle juice rapidly stopped experimentally induced cramps.

“This is something that athletes use, and kidney doctors often recommend to their patients, so it is nothing unique to cirrhosis,” Dr. Tapper said.

The PICCLES trial involved 74 adults (mean age, 56.6 years) with at least 4 muscle cramps in the prior month. In the cohort, 54% were men, and 41% had ascites.

The median cramp frequency was 11-12 per month, with an average cramp severity of more than 4 out of 10 on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for cramps.

Some patients were receiving medications for their cramps at baseline, such as magnesium, potassium, baclofen, vitamin E, taurine, and gabapentin/pregabalin.

Thirty-eight patients were randomly allocated to sip pickle juice and 36 to sip tap water at the onset of a muscle cramp.

The proportion of cramps treated was similar in the pickle juice and tap water groups (77% and 72%). More patients in the pickle juice group said their cramps were aborted by the intervention (69% vs. 40%).

The primary outcome was the change in cramp severity at 28-days VAS for cramps. Cramps were assessed 10 times over 28 days using interactive text messages.

Pickle juice was associated with a larger average reduction in cramp severity than tap water (–2.25 points vs. –0.36 on the VAS-cramps), a difference that was statistically significant (P = .03).

There were no significant changes in the proportion of days with cramp severity of more than 5 on the VAS, or on sleep quality or health-related quality of life.

Because pickle juice contains sodium, the researchers also assessed weight change as a safety outcome. They found no significant differences in weight change between the two groups overall or in the subset with ascites.

Pickle juice is a “safe option that can stop painful cramps,” Dr. Tapper said in an interview, but was “disheartened” that it did not improve quality of life.

Dr. Tapper encourages patients with cramps to ask their doctor about pickle juice and doctors to ask their patients about muscle cramps.

“Awareness of a patient’s cramps is often lacking. Asking about cramps is not routine but could be the most important advance relating to this study,” he said.

While sips of pickle juice are “unlikely to cause harm,” Dr. Tapper said, he is “a little nervous about advising patients to address their complex needs alone. [Doctors] are there to think through the root causes and help make adjustments that could prevent the cramps in the first place,” he said.

Outside experts weigh in

This news organization reached out to several outside experts for their perspective on the study.

Nancy Reau, MD, professor of internal medicine, associate director of solid organ transplantation, and section chief of hepatology. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, noted that interventions to manage and prevent muscle cramps are “important, as cramping is common in cirrhosis and strongly affects quality of life.”

Dr. Reau cautioned that while pickle juice “sounds benign, it does have a lot of salt. Despite the salt content, this study didn’t show any difference between patients with and without ascites.

“However, cramping is more common in our patients with sarcopenia and those on diuretics for fluid management and it would be easy to see how this might impact fluid management,” Dr. Reau noted.

“Given that it is the acid (not the salt) in the pickle juice, there might be low salt alternatives,” Dr. Reau said.

Echoing Dr. Reau, Ankur Shah, MD, division of kidney disease and hypertension, Brown University, Providence, R.I., noted that “overuse of pickle juice could place patients at risk of developing high blood pressure and fluid overload, and pickle juice should be included in the sodium restriction guidance given to patients with high blood pressure and heart failure.”

In this study, however, the individual dose consumed was low, Dr. Shah noted.

He said the study “elegantly provides evidence to support the practice of sipping pickle juice for cramping.”

The authors should be “applauded for studying a simple solution with the most rigorous of methodologies, a randomized controlled trial,” Dr. Shah added.

“This simple treatment may be helpful to patients far beyond those with just cirrhosis, and expect future studies to explore this treatment in other populations,” Dr. Shah said in an interview.

Paul Martin, MD, chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases and Mandel Chair in Gastroenterology, University of Miami, noted that, while muscle cramps can have a major impact on quality of life, “in terms of some of the other complications of cirrhosis that health care providers are dealing with, they may seem relatively innocuous, but obviously patients have a slightly different interpretation because of the effect cramps can have on sleep and so on.

“There have been a variety of home remedies to treat muscle cramps, but this study is intriguing as it suggests that pickle juice, which is freely available, helps mitigate the severity of the cramps. However, it’s unclear whether it prevents cramps,” Dr. Martin said in an interview.

Given that the study is getting traction on Twitter, Dr. Martin encouraged health care providers to be aware of the study and prepared to answer questions from patients.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Tapper has served as a consultant to Novartis, Axcella, and Allergan, has served on advisory boards for Mallinckrodt, Bausch Health, Kaleido, and Novo Nordisk, and has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead and Valeant. Dr. Reau, Dr. Shah, and Dr. Martin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the trial, patients with cirrhotic cramps who sipped pickle brine at the onset of a muscle cramp saw a significant decrease in cramp severity relative to peers who sipped tap water when the cramp hit.

“The acid (vinegar) in the brine triggers a nerve reflex to stop the cramp when it hits the throat. This is why only a sip is needed,” lead investigator Elliot Tapper, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told this news organization. The study was published online April 13 in American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Common and bothersome

Cramps are common in adults with cirrhosis, irrespective of disease severity. They can sometimes last for hours, and treatment options are limited.

In a prior study, 1 tablespoon of pickle juice rapidly stopped experimentally induced cramps.

“This is something that athletes use, and kidney doctors often recommend to their patients, so it is nothing unique to cirrhosis,” Dr. Tapper said.

The PICCLES trial involved 74 adults (mean age, 56.6 years) with at least 4 muscle cramps in the prior month. In the cohort, 54% were men, and 41% had ascites.

The median cramp frequency was 11-12 per month, with an average cramp severity of more than 4 out of 10 on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for cramps.

Some patients were receiving medications for their cramps at baseline, such as magnesium, potassium, baclofen, vitamin E, taurine, and gabapentin/pregabalin.

Thirty-eight patients were randomly allocated to sip pickle juice and 36 to sip tap water at the onset of a muscle cramp.

The proportion of cramps treated was similar in the pickle juice and tap water groups (77% and 72%). More patients in the pickle juice group said their cramps were aborted by the intervention (69% vs. 40%).

The primary outcome was the change in cramp severity at 28-days VAS for cramps. Cramps were assessed 10 times over 28 days using interactive text messages.

Pickle juice was associated with a larger average reduction in cramp severity than tap water (–2.25 points vs. –0.36 on the VAS-cramps), a difference that was statistically significant (P = .03).

There were no significant changes in the proportion of days with cramp severity of more than 5 on the VAS, or on sleep quality or health-related quality of life.

Because pickle juice contains sodium, the researchers also assessed weight change as a safety outcome. They found no significant differences in weight change between the two groups overall or in the subset with ascites.

Pickle juice is a “safe option that can stop painful cramps,” Dr. Tapper said in an interview, but was “disheartened” that it did not improve quality of life.

Dr. Tapper encourages patients with cramps to ask their doctor about pickle juice and doctors to ask their patients about muscle cramps.

“Awareness of a patient’s cramps is often lacking. Asking about cramps is not routine but could be the most important advance relating to this study,” he said.

While sips of pickle juice are “unlikely to cause harm,” Dr. Tapper said, he is “a little nervous about advising patients to address their complex needs alone. [Doctors] are there to think through the root causes and help make adjustments that could prevent the cramps in the first place,” he said.

Outside experts weigh in

This news organization reached out to several outside experts for their perspective on the study.

Nancy Reau, MD, professor of internal medicine, associate director of solid organ transplantation, and section chief of hepatology. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, noted that interventions to manage and prevent muscle cramps are “important, as cramping is common in cirrhosis and strongly affects quality of life.”

Dr. Reau cautioned that while pickle juice “sounds benign, it does have a lot of salt. Despite the salt content, this study didn’t show any difference between patients with and without ascites.

“However, cramping is more common in our patients with sarcopenia and those on diuretics for fluid management and it would be easy to see how this might impact fluid management,” Dr. Reau noted.

“Given that it is the acid (not the salt) in the pickle juice, there might be low salt alternatives,” Dr. Reau said.

Echoing Dr. Reau, Ankur Shah, MD, division of kidney disease and hypertension, Brown University, Providence, R.I., noted that “overuse of pickle juice could place patients at risk of developing high blood pressure and fluid overload, and pickle juice should be included in the sodium restriction guidance given to patients with high blood pressure and heart failure.”

In this study, however, the individual dose consumed was low, Dr. Shah noted.

He said the study “elegantly provides evidence to support the practice of sipping pickle juice for cramping.”

The authors should be “applauded for studying a simple solution with the most rigorous of methodologies, a randomized controlled trial,” Dr. Shah added.

“This simple treatment may be helpful to patients far beyond those with just cirrhosis, and expect future studies to explore this treatment in other populations,” Dr. Shah said in an interview.

Paul Martin, MD, chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases and Mandel Chair in Gastroenterology, University of Miami, noted that, while muscle cramps can have a major impact on quality of life, “in terms of some of the other complications of cirrhosis that health care providers are dealing with, they may seem relatively innocuous, but obviously patients have a slightly different interpretation because of the effect cramps can have on sleep and so on.

“There have been a variety of home remedies to treat muscle cramps, but this study is intriguing as it suggests that pickle juice, which is freely available, helps mitigate the severity of the cramps. However, it’s unclear whether it prevents cramps,” Dr. Martin said in an interview.

Given that the study is getting traction on Twitter, Dr. Martin encouraged health care providers to be aware of the study and prepared to answer questions from patients.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Tapper has served as a consultant to Novartis, Axcella, and Allergan, has served on advisory boards for Mallinckrodt, Bausch Health, Kaleido, and Novo Nordisk, and has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead and Valeant. Dr. Reau, Dr. Shah, and Dr. Martin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the trial, patients with cirrhotic cramps who sipped pickle brine at the onset of a muscle cramp saw a significant decrease in cramp severity relative to peers who sipped tap water when the cramp hit.

“The acid (vinegar) in the brine triggers a nerve reflex to stop the cramp when it hits the throat. This is why only a sip is needed,” lead investigator Elliot Tapper, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told this news organization. The study was published online April 13 in American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Common and bothersome

Cramps are common in adults with cirrhosis, irrespective of disease severity. They can sometimes last for hours, and treatment options are limited.

In a prior study, 1 tablespoon of pickle juice rapidly stopped experimentally induced cramps.

“This is something that athletes use, and kidney doctors often recommend to their patients, so it is nothing unique to cirrhosis,” Dr. Tapper said.

The PICCLES trial involved 74 adults (mean age, 56.6 years) with at least 4 muscle cramps in the prior month. In the cohort, 54% were men, and 41% had ascites.

The median cramp frequency was 11-12 per month, with an average cramp severity of more than 4 out of 10 on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for cramps.

Some patients were receiving medications for their cramps at baseline, such as magnesium, potassium, baclofen, vitamin E, taurine, and gabapentin/pregabalin.

Thirty-eight patients were randomly allocated to sip pickle juice and 36 to sip tap water at the onset of a muscle cramp.

The proportion of cramps treated was similar in the pickle juice and tap water groups (77% and 72%). More patients in the pickle juice group said their cramps were aborted by the intervention (69% vs. 40%).

The primary outcome was the change in cramp severity at 28-days VAS for cramps. Cramps were assessed 10 times over 28 days using interactive text messages.

Pickle juice was associated with a larger average reduction in cramp severity than tap water (–2.25 points vs. –0.36 on the VAS-cramps), a difference that was statistically significant (P = .03).

There were no significant changes in the proportion of days with cramp severity of more than 5 on the VAS, or on sleep quality or health-related quality of life.

Because pickle juice contains sodium, the researchers also assessed weight change as a safety outcome. They found no significant differences in weight change between the two groups overall or in the subset with ascites.

Pickle juice is a “safe option that can stop painful cramps,” Dr. Tapper said in an interview, but was “disheartened” that it did not improve quality of life.

Dr. Tapper encourages patients with cramps to ask their doctor about pickle juice and doctors to ask their patients about muscle cramps.

“Awareness of a patient’s cramps is often lacking. Asking about cramps is not routine but could be the most important advance relating to this study,” he said.

While sips of pickle juice are “unlikely to cause harm,” Dr. Tapper said, he is “a little nervous about advising patients to address their complex needs alone. [Doctors] are there to think through the root causes and help make adjustments that could prevent the cramps in the first place,” he said.

Outside experts weigh in

This news organization reached out to several outside experts for their perspective on the study.

Nancy Reau, MD, professor of internal medicine, associate director of solid organ transplantation, and section chief of hepatology. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, noted that interventions to manage and prevent muscle cramps are “important, as cramping is common in cirrhosis and strongly affects quality of life.”

Dr. Reau cautioned that while pickle juice “sounds benign, it does have a lot of salt. Despite the salt content, this study didn’t show any difference between patients with and without ascites.

“However, cramping is more common in our patients with sarcopenia and those on diuretics for fluid management and it would be easy to see how this might impact fluid management,” Dr. Reau noted.

“Given that it is the acid (not the salt) in the pickle juice, there might be low salt alternatives,” Dr. Reau said.

Echoing Dr. Reau, Ankur Shah, MD, division of kidney disease and hypertension, Brown University, Providence, R.I., noted that “overuse of pickle juice could place patients at risk of developing high blood pressure and fluid overload, and pickle juice should be included in the sodium restriction guidance given to patients with high blood pressure and heart failure.”

In this study, however, the individual dose consumed was low, Dr. Shah noted.

He said the study “elegantly provides evidence to support the practice of sipping pickle juice for cramping.”

The authors should be “applauded for studying a simple solution with the most rigorous of methodologies, a randomized controlled trial,” Dr. Shah added.

“This simple treatment may be helpful to patients far beyond those with just cirrhosis, and expect future studies to explore this treatment in other populations,” Dr. Shah said in an interview.

Paul Martin, MD, chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases and Mandel Chair in Gastroenterology, University of Miami, noted that, while muscle cramps can have a major impact on quality of life, “in terms of some of the other complications of cirrhosis that health care providers are dealing with, they may seem relatively innocuous, but obviously patients have a slightly different interpretation because of the effect cramps can have on sleep and so on.

“There have been a variety of home remedies to treat muscle cramps, but this study is intriguing as it suggests that pickle juice, which is freely available, helps mitigate the severity of the cramps. However, it’s unclear whether it prevents cramps,” Dr. Martin said in an interview.

Given that the study is getting traction on Twitter, Dr. Martin encouraged health care providers to be aware of the study and prepared to answer questions from patients.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Tapper has served as a consultant to Novartis, Axcella, and Allergan, has served on advisory boards for Mallinckrodt, Bausch Health, Kaleido, and Novo Nordisk, and has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead and Valeant. Dr. Reau, Dr. Shah, and Dr. Martin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To engage injection drug users in HCV care, go to where they are

For injection drug users with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, providing treatment opportunities within a local needle exchange program can provide care to more patients and eventually cure more patients, a new study suggests.

The study’s findings help “counteract the implicit belief within the medical community that people who inject drugs can’t or don’t want to engage in health care,” lead author Benjamin Eckhardt, MD, with NYU Grossman School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“By simply focusing on patient accompaniment, limiting stigma, and removing the punitive response for missed appointments, we can effectively engage people who inject drugs in health care and more specifically cure their infection, making significant inroads to HCV elimination,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

The study was published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Nonjudgmental, patient-centered approach

Researchers included 165 injection drug users with HCV (mean age, 42 years; 78% men); 82 were randomly allocated to the accessible care intervention and 83 to a usual care control group.

The accessible care model provides HCV treatment within a community-based needle exchange program in a comfortable, nonjudgmental atmosphere, “without fear of shame or stigma that people who inject drugs often experience in mainstream institutions,” the investigators explain.

Control participants were connected to a patient navigator who facilitated referrals to community direct antigen antiviral therapy programs that were not at a syringe service program.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, those enrolled in the accessible care group achieved sustained viral eradication at 12 months at significantly higher rates than those in the control group (67% vs. 23%; P < .001).

Once patients initiated treatment, cure rates were the same in both groups (86%), indicating that the major benefit of the accessible care program was in facilitating treatment, rather than increasing adherence to or response to treatment, the researchers noted.

This is reflected in the fact that the percentage of participants who advanced along the care cascade was significantly higher at each step for the accessible care group than the control group, from referral to an HCV clinician (93% vs. 45%), attendance of the initial HCV clinical visit (87% vs. 37%), completion of baseline laboratory testing (87% vs. 31%), and treatment initiation (78% vs. 27%).

Getting to the population in need

“The most surprising aspect of the study was how successful we were at recruiting, engaging, and treating people who inject drugs who lived outside the immediate community where the syringe exchange program was located and had no prior connection to the program,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

“We had numerous individuals travel 45-plus minutes on the subway from the South Bronx, passing four major medical centers with robust hepatitis C treatment programs, to seek care for hepatitis C in a small, dark office – but also an office they’d heard can be trusted – without fear of stigma or preconditions,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

Commenting on the study’s findings, Nancy Reau, MD, section chief of hepatology at Rush Medical College, Chicago, said, “This is another successful example of making therapy accessible to the population who is in need versus trying to move them into a tertiary care model.”

Dr. Reau noted that similar care models exist in the United States but are not always accessible to the population in need.

“The safety and efficacy of current therapy and the simplified care cascade make HCV an appropriate disease for this delivery,” she said, adding that this study “highlights not just the importance of these programs but also the necessity of engaging the medical community, changing policy, and using patient navigators and monetary support/prioritization to provide appropriate HCV management to those who are at high risk for the disease and for transmission.”

Accessible care beyond HCV

The coauthors of an accompanying editor’s note point out that the treatment for HCV has improved substantially, but it can be a real challenge to provide treatment to injection drug users because the U.S. health care system is not oriented toward the needs of this population.

“It is not surprising that the accessible care arm achieved a higher rate of viral eradication, as it created a patient-focused experience,” write Asha Choudhury, MD, MPH, with the University of California, San Francisco, and Mitchell Katz, MD, with NYC Health and Hospitals. “Creating inviting and engaging environments is particularly important when caring for patients from stigmatized groups. Having more sites that are accessible and inclusive like this for treating patients will likely increase treatment of hepatitis C.”

In their view, the study raises “two dueling questions: Is this model replicable across the U.S.? And, conversely, why isn’t all medical care offered in friendly, nonjudgmental settings with the intention of meeting patient goals?”

They conclude that the study’s lessons extend beyond this particular population and have implications for the field at large.

“The model is replicable to the extent that health care systems are prepared to provide nonjudgmental supportive care for persons who inject drugs,” they write. “However, all patients would benefit from a health care system that provided more patient-centered environments.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Eckhardt reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Gilead during the conduct of the study. Dr. Choudhury, Dr. Katz, and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For injection drug users with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, providing treatment opportunities within a local needle exchange program can provide care to more patients and eventually cure more patients, a new study suggests.

The study’s findings help “counteract the implicit belief within the medical community that people who inject drugs can’t or don’t want to engage in health care,” lead author Benjamin Eckhardt, MD, with NYU Grossman School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“By simply focusing on patient accompaniment, limiting stigma, and removing the punitive response for missed appointments, we can effectively engage people who inject drugs in health care and more specifically cure their infection, making significant inroads to HCV elimination,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

The study was published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Nonjudgmental, patient-centered approach

Researchers included 165 injection drug users with HCV (mean age, 42 years; 78% men); 82 were randomly allocated to the accessible care intervention and 83 to a usual care control group.

The accessible care model provides HCV treatment within a community-based needle exchange program in a comfortable, nonjudgmental atmosphere, “without fear of shame or stigma that people who inject drugs often experience in mainstream institutions,” the investigators explain.

Control participants were connected to a patient navigator who facilitated referrals to community direct antigen antiviral therapy programs that were not at a syringe service program.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, those enrolled in the accessible care group achieved sustained viral eradication at 12 months at significantly higher rates than those in the control group (67% vs. 23%; P < .001).

Once patients initiated treatment, cure rates were the same in both groups (86%), indicating that the major benefit of the accessible care program was in facilitating treatment, rather than increasing adherence to or response to treatment, the researchers noted.

This is reflected in the fact that the percentage of participants who advanced along the care cascade was significantly higher at each step for the accessible care group than the control group, from referral to an HCV clinician (93% vs. 45%), attendance of the initial HCV clinical visit (87% vs. 37%), completion of baseline laboratory testing (87% vs. 31%), and treatment initiation (78% vs. 27%).

Getting to the population in need

“The most surprising aspect of the study was how successful we were at recruiting, engaging, and treating people who inject drugs who lived outside the immediate community where the syringe exchange program was located and had no prior connection to the program,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

“We had numerous individuals travel 45-plus minutes on the subway from the South Bronx, passing four major medical centers with robust hepatitis C treatment programs, to seek care for hepatitis C in a small, dark office – but also an office they’d heard can be trusted – without fear of stigma or preconditions,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

Commenting on the study’s findings, Nancy Reau, MD, section chief of hepatology at Rush Medical College, Chicago, said, “This is another successful example of making therapy accessible to the population who is in need versus trying to move them into a tertiary care model.”

Dr. Reau noted that similar care models exist in the United States but are not always accessible to the population in need.

“The safety and efficacy of current therapy and the simplified care cascade make HCV an appropriate disease for this delivery,” she said, adding that this study “highlights not just the importance of these programs but also the necessity of engaging the medical community, changing policy, and using patient navigators and monetary support/prioritization to provide appropriate HCV management to those who are at high risk for the disease and for transmission.”

Accessible care beyond HCV

The coauthors of an accompanying editor’s note point out that the treatment for HCV has improved substantially, but it can be a real challenge to provide treatment to injection drug users because the U.S. health care system is not oriented toward the needs of this population.

“It is not surprising that the accessible care arm achieved a higher rate of viral eradication, as it created a patient-focused experience,” write Asha Choudhury, MD, MPH, with the University of California, San Francisco, and Mitchell Katz, MD, with NYC Health and Hospitals. “Creating inviting and engaging environments is particularly important when caring for patients from stigmatized groups. Having more sites that are accessible and inclusive like this for treating patients will likely increase treatment of hepatitis C.”

In their view, the study raises “two dueling questions: Is this model replicable across the U.S.? And, conversely, why isn’t all medical care offered in friendly, nonjudgmental settings with the intention of meeting patient goals?”

They conclude that the study’s lessons extend beyond this particular population and have implications for the field at large.

“The model is replicable to the extent that health care systems are prepared to provide nonjudgmental supportive care for persons who inject drugs,” they write. “However, all patients would benefit from a health care system that provided more patient-centered environments.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Eckhardt reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Gilead during the conduct of the study. Dr. Choudhury, Dr. Katz, and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For injection drug users with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, providing treatment opportunities within a local needle exchange program can provide care to more patients and eventually cure more patients, a new study suggests.

The study’s findings help “counteract the implicit belief within the medical community that people who inject drugs can’t or don’t want to engage in health care,” lead author Benjamin Eckhardt, MD, with NYU Grossman School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“By simply focusing on patient accompaniment, limiting stigma, and removing the punitive response for missed appointments, we can effectively engage people who inject drugs in health care and more specifically cure their infection, making significant inroads to HCV elimination,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

The study was published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Nonjudgmental, patient-centered approach

Researchers included 165 injection drug users with HCV (mean age, 42 years; 78% men); 82 were randomly allocated to the accessible care intervention and 83 to a usual care control group.

The accessible care model provides HCV treatment within a community-based needle exchange program in a comfortable, nonjudgmental atmosphere, “without fear of shame or stigma that people who inject drugs often experience in mainstream institutions,” the investigators explain.

Control participants were connected to a patient navigator who facilitated referrals to community direct antigen antiviral therapy programs that were not at a syringe service program.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, those enrolled in the accessible care group achieved sustained viral eradication at 12 months at significantly higher rates than those in the control group (67% vs. 23%; P < .001).

Once patients initiated treatment, cure rates were the same in both groups (86%), indicating that the major benefit of the accessible care program was in facilitating treatment, rather than increasing adherence to or response to treatment, the researchers noted.

This is reflected in the fact that the percentage of participants who advanced along the care cascade was significantly higher at each step for the accessible care group than the control group, from referral to an HCV clinician (93% vs. 45%), attendance of the initial HCV clinical visit (87% vs. 37%), completion of baseline laboratory testing (87% vs. 31%), and treatment initiation (78% vs. 27%).

Getting to the population in need

“The most surprising aspect of the study was how successful we were at recruiting, engaging, and treating people who inject drugs who lived outside the immediate community where the syringe exchange program was located and had no prior connection to the program,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

“We had numerous individuals travel 45-plus minutes on the subway from the South Bronx, passing four major medical centers with robust hepatitis C treatment programs, to seek care for hepatitis C in a small, dark office – but also an office they’d heard can be trusted – without fear of stigma or preconditions,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

Commenting on the study’s findings, Nancy Reau, MD, section chief of hepatology at Rush Medical College, Chicago, said, “This is another successful example of making therapy accessible to the population who is in need versus trying to move them into a tertiary care model.”

Dr. Reau noted that similar care models exist in the United States but are not always accessible to the population in need.

“The safety and efficacy of current therapy and the simplified care cascade make HCV an appropriate disease for this delivery,” she said, adding that this study “highlights not just the importance of these programs but also the necessity of engaging the medical community, changing policy, and using patient navigators and monetary support/prioritization to provide appropriate HCV management to those who are at high risk for the disease and for transmission.”

Accessible care beyond HCV

The coauthors of an accompanying editor’s note point out that the treatment for HCV has improved substantially, but it can be a real challenge to provide treatment to injection drug users because the U.S. health care system is not oriented toward the needs of this population.

“It is not surprising that the accessible care arm achieved a higher rate of viral eradication, as it created a patient-focused experience,” write Asha Choudhury, MD, MPH, with the University of California, San Francisco, and Mitchell Katz, MD, with NYC Health and Hospitals. “Creating inviting and engaging environments is particularly important when caring for patients from stigmatized groups. Having more sites that are accessible and inclusive like this for treating patients will likely increase treatment of hepatitis C.”

In their view, the study raises “two dueling questions: Is this model replicable across the U.S.? And, conversely, why isn’t all medical care offered in friendly, nonjudgmental settings with the intention of meeting patient goals?”

They conclude that the study’s lessons extend beyond this particular population and have implications for the field at large.

“The model is replicable to the extent that health care systems are prepared to provide nonjudgmental supportive care for persons who inject drugs,” they write. “However, all patients would benefit from a health care system that provided more patient-centered environments.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Eckhardt reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Gilead during the conduct of the study. Dr. Choudhury, Dr. Katz, and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AHA statement addresses CVD risk in NAFLD

At least one in four adults worldwide is thought to have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is the leading cause of death in NAFLD, but the condition is widely underdiagnosed, according to a new American Heart Association scientific statement on NAFLD and cardiovascular risks.

The statement, published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, aims to increase awareness of NAFLD among cardiologists and other clinicians treating vulnerable patients. It pulls together the existing evidence for using imaging to diagnose NAFLD as well as the role of current and emerging treatments for managing the disease.

“NAFLD is common, but most patients are undiagnosed,” statement writing committee chair P. Barton Duell, MD, said in an interview. “The identification of normal liver enzyme levels does not exclude the diagnosis of NAFLD. Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary to improve the health of patients with established NAFLD, as well as preventing the development of NAFLD in patients who are at risk for the condition.”

Dr. Duell is a professor at the Knight Cardiovascular Institute and division of endocrinology, diabetes and clinical nutrition at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

This is the AHA’s first scientific statement on NAFLD. In 2021, the association issued a statement on obesity and CVD). Also in 2021, a multiorganization group headed by the American Gastroenterological Association published a “Call to Action” on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) , a form of NAFLD that’s characterized by inflammation and scarring of the liver, and typically requires a liver biopsy for diagnosis.

Key take-homes

The AHA statement on NAFLD is sweeping. Among its key take-home messages:

- Calling into question the effectiveness of AST and ALT testing for diagnosing NAFLD and NASH.

- Providing context to the role of insulin resistance – either with or without diabetes – as well as obesity (particularly visceral adiposity), metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia in NAFLD.

- Advocating for lifestyle interventions – diet, exercise, weight loss and alcohol avoidance – as the key therapeutic intervention for NAFLD.

- Asserting that glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists may modestly improve NAFLD.

The statement also tackles the differences in terminology different organizations use to describe NAFLD. “The terminology section is important to ensure everyone is using the right terminology in assessing patients, as well as choosing appropriate treatment interventions,” Dr. Duell said.

The statement also explores genetic factors that can predispose people to NAFLD, Dr. Duell pointed out, and it goes into detail about strategies for screening NAFLD and NASH. “It is not possible to diagnose NAFLD without understanding the pros and cons of various screening modalities, as well as the lack of sensitivity of some tests for detection of NAFLD We hope this information will increase success in screening for and early identification of NAFLD.”

Dr. Duell explained the rationale for issuing the statement. “Rates of NAFLD are increasing worldwide in association with rising rates of elevated body mass index and the metabolic syndrome, but the condition is commonly undiagnosed,” he said. “This allows patients to experience progression of disease, leading to hepatic and cardiovascular complications.”

Avoiding NAFLD risk factors along with early diagnosis and treatment “may have the potential to mitigate long-term complications from NAFLD,” Dr. Duell said.

“This is one of first times where we really look at cardiovascular risks associated with NAFLD and pinpoint the risk factors, the imaging tools that can be used for diagnosing fatty liver disease, and ultimately what potential treatments we can consider,” Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley, MD, MPH, author of the AHA statement on obesity and CV risk, said in an interview.

“NAFLD has not been at the forefront of cardiologists’ minds, but this statement highlights the importance of liver fat as a fat depot,” said Dr. Powell-Wiley, chief of the Social Determinants of Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk Laboratory at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md.

“It does provide greater clarity for us as cardiologists, especially when thinking about what is required for diagnosis and ultimately how this relates to cardiovascular disease for people with fatty liver disease,” she said.

Dr. Duell and Dr. Powell-Wiley have no relevant relationships to disclose.

At least one in four adults worldwide is thought to have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is the leading cause of death in NAFLD, but the condition is widely underdiagnosed, according to a new American Heart Association scientific statement on NAFLD and cardiovascular risks.

The statement, published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, aims to increase awareness of NAFLD among cardiologists and other clinicians treating vulnerable patients. It pulls together the existing evidence for using imaging to diagnose NAFLD as well as the role of current and emerging treatments for managing the disease.

“NAFLD is common, but most patients are undiagnosed,” statement writing committee chair P. Barton Duell, MD, said in an interview. “The identification of normal liver enzyme levels does not exclude the diagnosis of NAFLD. Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary to improve the health of patients with established NAFLD, as well as preventing the development of NAFLD in patients who are at risk for the condition.”

Dr. Duell is a professor at the Knight Cardiovascular Institute and division of endocrinology, diabetes and clinical nutrition at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

This is the AHA’s first scientific statement on NAFLD. In 2021, the association issued a statement on obesity and CVD). Also in 2021, a multiorganization group headed by the American Gastroenterological Association published a “Call to Action” on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) , a form of NAFLD that’s characterized by inflammation and scarring of the liver, and typically requires a liver biopsy for diagnosis.

Key take-homes

The AHA statement on NAFLD is sweeping. Among its key take-home messages:

- Calling into question the effectiveness of AST and ALT testing for diagnosing NAFLD and NASH.

- Providing context to the role of insulin resistance – either with or without diabetes – as well as obesity (particularly visceral adiposity), metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia in NAFLD.

- Advocating for lifestyle interventions – diet, exercise, weight loss and alcohol avoidance – as the key therapeutic intervention for NAFLD.

- Asserting that glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists may modestly improve NAFLD.

The statement also tackles the differences in terminology different organizations use to describe NAFLD. “The terminology section is important to ensure everyone is using the right terminology in assessing patients, as well as choosing appropriate treatment interventions,” Dr. Duell said.

The statement also explores genetic factors that can predispose people to NAFLD, Dr. Duell pointed out, and it goes into detail about strategies for screening NAFLD and NASH. “It is not possible to diagnose NAFLD without understanding the pros and cons of various screening modalities, as well as the lack of sensitivity of some tests for detection of NAFLD We hope this information will increase success in screening for and early identification of NAFLD.”

Dr. Duell explained the rationale for issuing the statement. “Rates of NAFLD are increasing worldwide in association with rising rates of elevated body mass index and the metabolic syndrome, but the condition is commonly undiagnosed,” he said. “This allows patients to experience progression of disease, leading to hepatic and cardiovascular complications.”

Avoiding NAFLD risk factors along with early diagnosis and treatment “may have the potential to mitigate long-term complications from NAFLD,” Dr. Duell said.

“This is one of first times where we really look at cardiovascular risks associated with NAFLD and pinpoint the risk factors, the imaging tools that can be used for diagnosing fatty liver disease, and ultimately what potential treatments we can consider,” Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley, MD, MPH, author of the AHA statement on obesity and CV risk, said in an interview.

“NAFLD has not been at the forefront of cardiologists’ minds, but this statement highlights the importance of liver fat as a fat depot,” said Dr. Powell-Wiley, chief of the Social Determinants of Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk Laboratory at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md.

“It does provide greater clarity for us as cardiologists, especially when thinking about what is required for diagnosis and ultimately how this relates to cardiovascular disease for people with fatty liver disease,” she said.

Dr. Duell and Dr. Powell-Wiley have no relevant relationships to disclose.

At least one in four adults worldwide is thought to have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is the leading cause of death in NAFLD, but the condition is widely underdiagnosed, according to a new American Heart Association scientific statement on NAFLD and cardiovascular risks.

The statement, published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, aims to increase awareness of NAFLD among cardiologists and other clinicians treating vulnerable patients. It pulls together the existing evidence for using imaging to diagnose NAFLD as well as the role of current and emerging treatments for managing the disease.

“NAFLD is common, but most patients are undiagnosed,” statement writing committee chair P. Barton Duell, MD, said in an interview. “The identification of normal liver enzyme levels does not exclude the diagnosis of NAFLD. Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary to improve the health of patients with established NAFLD, as well as preventing the development of NAFLD in patients who are at risk for the condition.”

Dr. Duell is a professor at the Knight Cardiovascular Institute and division of endocrinology, diabetes and clinical nutrition at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

This is the AHA’s first scientific statement on NAFLD. In 2021, the association issued a statement on obesity and CVD). Also in 2021, a multiorganization group headed by the American Gastroenterological Association published a “Call to Action” on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) , a form of NAFLD that’s characterized by inflammation and scarring of the liver, and typically requires a liver biopsy for diagnosis.

Key take-homes

The AHA statement on NAFLD is sweeping. Among its key take-home messages:

- Calling into question the effectiveness of AST and ALT testing for diagnosing NAFLD and NASH.

- Providing context to the role of insulin resistance – either with or without diabetes – as well as obesity (particularly visceral adiposity), metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia in NAFLD.

- Advocating for lifestyle interventions – diet, exercise, weight loss and alcohol avoidance – as the key therapeutic intervention for NAFLD.

- Asserting that glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists may modestly improve NAFLD.

The statement also tackles the differences in terminology different organizations use to describe NAFLD. “The terminology section is important to ensure everyone is using the right terminology in assessing patients, as well as choosing appropriate treatment interventions,” Dr. Duell said.

The statement also explores genetic factors that can predispose people to NAFLD, Dr. Duell pointed out, and it goes into detail about strategies for screening NAFLD and NASH. “It is not possible to diagnose NAFLD without understanding the pros and cons of various screening modalities, as well as the lack of sensitivity of some tests for detection of NAFLD We hope this information will increase success in screening for and early identification of NAFLD.”

Dr. Duell explained the rationale for issuing the statement. “Rates of NAFLD are increasing worldwide in association with rising rates of elevated body mass index and the metabolic syndrome, but the condition is commonly undiagnosed,” he said. “This allows patients to experience progression of disease, leading to hepatic and cardiovascular complications.”

Avoiding NAFLD risk factors along with early diagnosis and treatment “may have the potential to mitigate long-term complications from NAFLD,” Dr. Duell said.

“This is one of first times where we really look at cardiovascular risks associated with NAFLD and pinpoint the risk factors, the imaging tools that can be used for diagnosing fatty liver disease, and ultimately what potential treatments we can consider,” Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley, MD, MPH, author of the AHA statement on obesity and CV risk, said in an interview.

“NAFLD has not been at the forefront of cardiologists’ minds, but this statement highlights the importance of liver fat as a fat depot,” said Dr. Powell-Wiley, chief of the Social Determinants of Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk Laboratory at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md.

“It does provide greater clarity for us as cardiologists, especially when thinking about what is required for diagnosis and ultimately how this relates to cardiovascular disease for people with fatty liver disease,” she said.

Dr. Duell and Dr. Powell-Wiley have no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM ARTERIOSCLEROSIS, THROMBOSIS, AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY

52-year-old man • hematemesis • history of cirrhosis • persistent fevers • Dx?

THE CASE

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department after vomiting a large volume of blood and was admitted to the intensive care unit. His past medical history was remarkable for untreated chronic hepatitis C resulting from injection drug use and cirrhosis without prior history of esophageal varices.

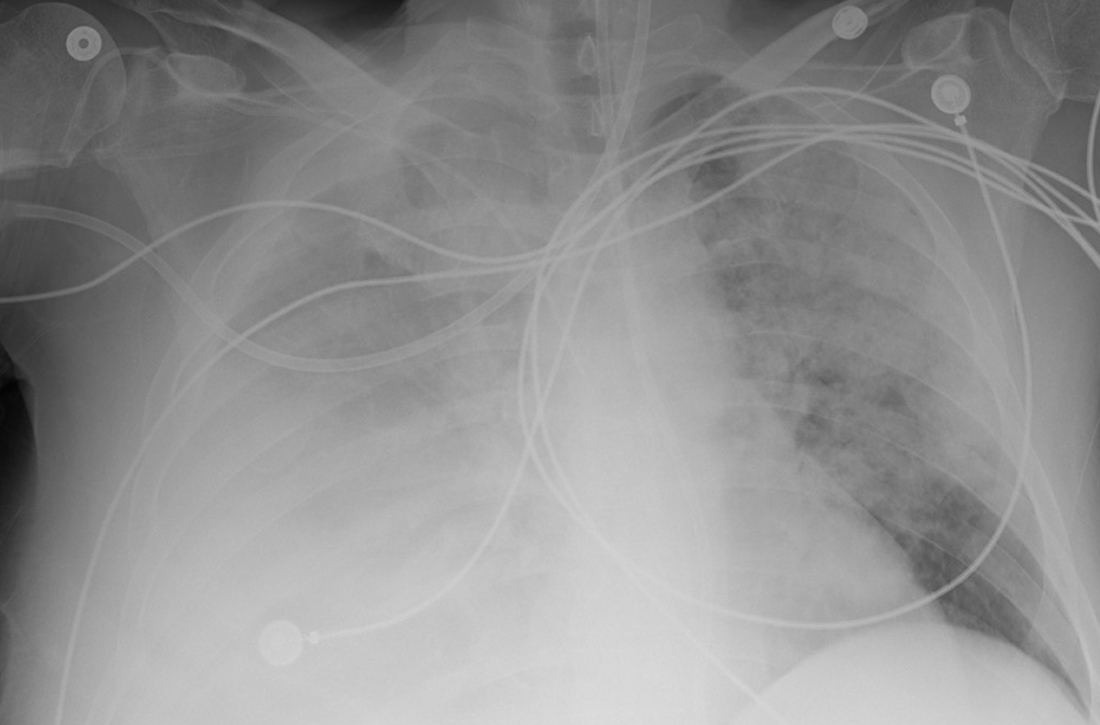

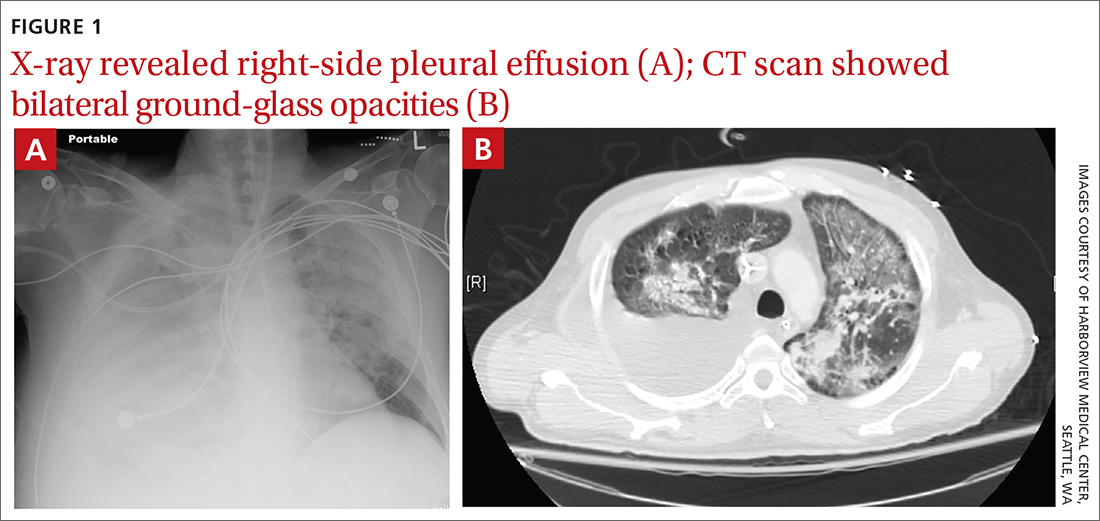

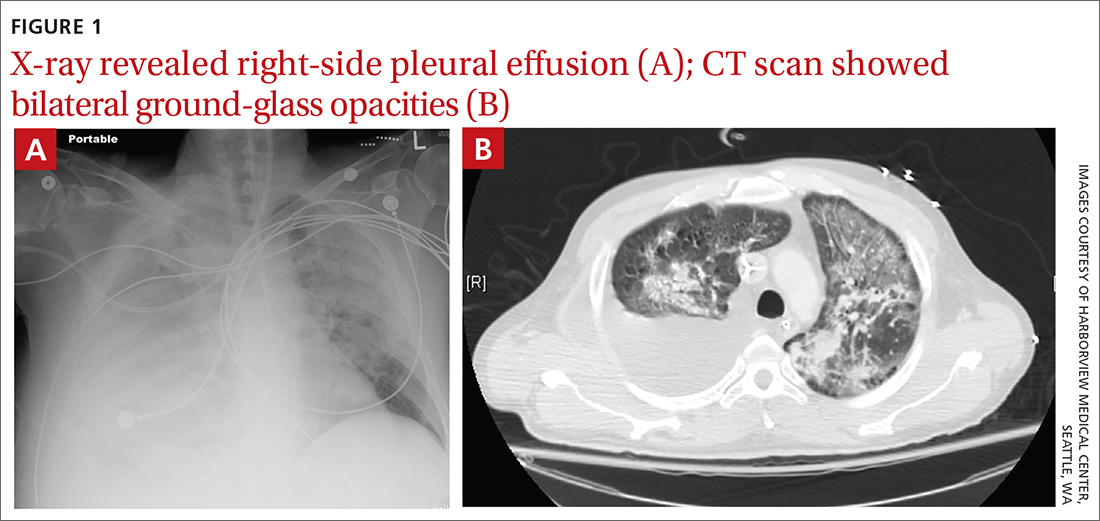

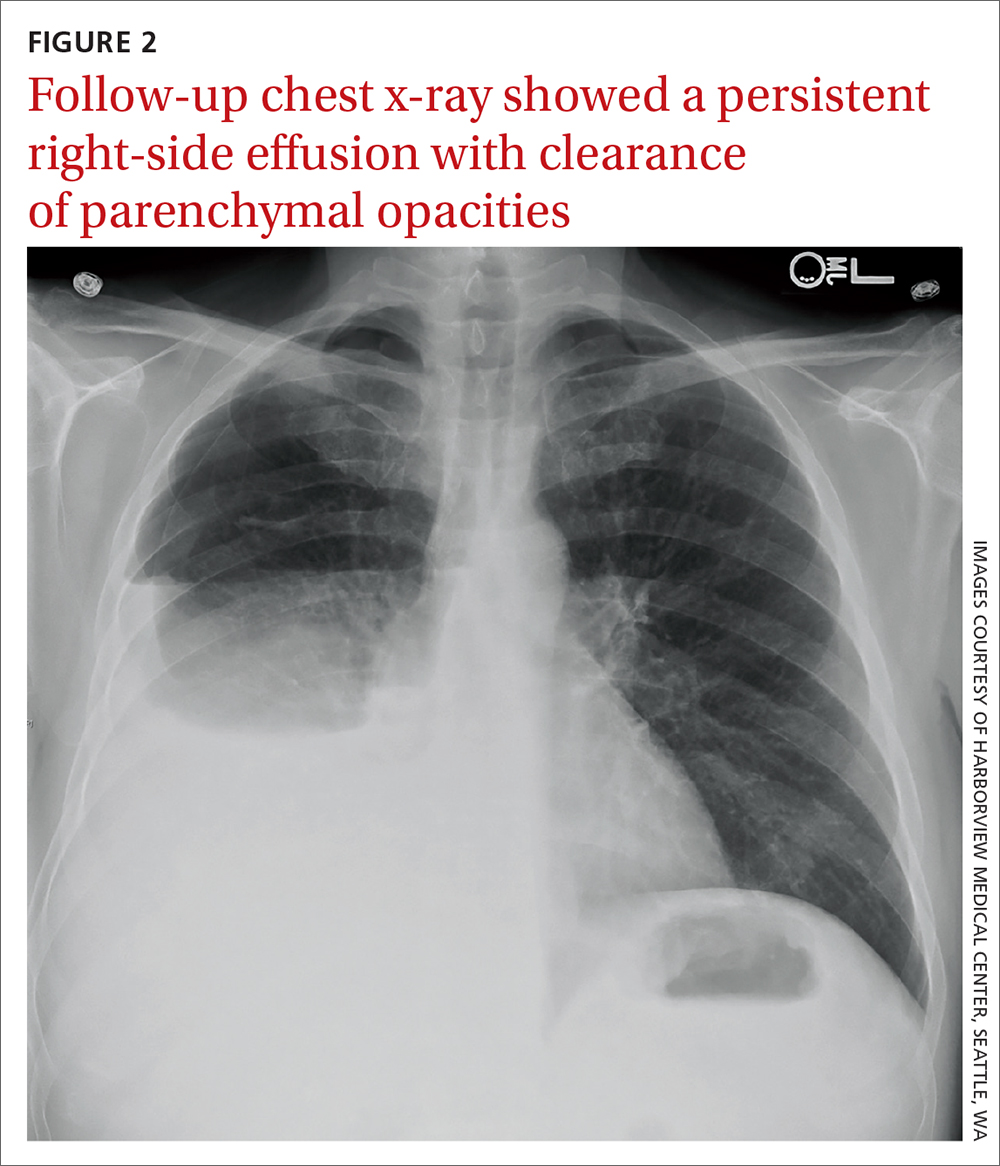

Due to ongoing hematemesis, he was intubated for airway protection and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with banding of large esophageal varices on hospital day (HD) 1. He was extubated on HD 2 after clinical stability was achieved; however, he became encephalopathic over the subsequent days despite treatment with lactulose. On HD 4, the patient required re-intubation for progressive respiratory failure. Chest imaging revealed a large, simple-appearing right pleural effusion and extensive bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities (FIGURE 1).

Thoracentesis was ordered and revealed transudative pleural fluid; this finding, along with negative infectious studies, was consistent with hepatic hydrothorax. In the setting of initial decompensation, empiric treatment with vancomycin and meropenem was started for suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The patient had persistent fevers that had developed during his hospital stay and pulmonary opacities, despite 72 hours of treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Thus, a diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. BAL cell count and differential revealed 363 nucleated cells/µL, with profound eosinophilia (42% eosinophils, 44% macrophages, 14% neutrophils).

Bacterial and fungal cultures and a viral polymerase chain reaction panel were negative. HIV antibody-antigen and RNA testing were also negative. The patient had no evidence or history of underlying malignancy, autoimmune disease, or recent immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids. Due to consistent imaging findings and lack of improvement with appropriate treatment for bacterial pneumonia, further work-up was pursued.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Given the consistent radiographic pattern, the differential diagnosis for this patient included pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a potentially life-threatening opportunistic infection. Work-up therefore included direct fluorescent antibody testing, which was positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii, a fungus that can cause PCP.

Of note, the patient’s white blood cell count was elevated on admission (11.44 × 103/µL) but low for much of his hospital stay (nadir = 1.97 × 103/µL), with associated lymphopenia (nadir = 0.22 × 103/µl). No peripheral eosinophilia was noted.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

PCP typically occurs in immunocompromised individuals and may be related to HIV infection, malignancy, or exposure to immunosuppressive therapies.1,2 While rare cases of PCP have been described in adults without predisposing factors, many of these cases occurred at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, prior to reliable HIV testing.3-5

Uncharted territory. We were confident in our diagnosis because immunofluorescence testing has very few false-positives and a high specificity.6-8 But there were informational gaps. The eosinophilia recorded on BAL is poorly described in HIV-negative patients with PCP but well-described in HIV-positive patients, with the level of eosinophilia associated with disease severity.9,10 Eosinophils are thought to contribute to pulmonary inflammation, which may explain the severity of our patient’s course.10

A first of its kind case?

To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCP in a patient with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis C virus infection and no other predisposing conditions or preceding immunosuppressive therapy. We suspect that his lymphopenia, which was noted during his critical illness, predisposed him to PCP.

Lymphocytes (in particular CD4+ T cells) have been shown to play an important role, along with alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, in directing the host defense against

Typical risk factors for lymphopenia had not been observed in this patient. However, cirrhosis has been associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts and disruption of cell-mediated immunity, even in HIV-seronegative patients.14,15 There are several postulated mechanisms for low CD4+ T-cell counts in cirrhosis, including splenic sequestration, impaired T-cell production (due to impaired thymopoiesis), increased T-cell consumption, and apoptosis (due to persistent immune system activation from bacterial translocation and an overall pro-inflammatory state).16,17

Continue to: Predisposing factors guide treatment

Predisposing factors guide treatment

Routine treatment for PCP in patients without HIV is a 21-day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Dosing for patients with normal renal function is 15 to 20 mg/kg orally or intravenously per day. Patients with allergy to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole should ideally undergo desensitization, given its effectiveness against PCP.

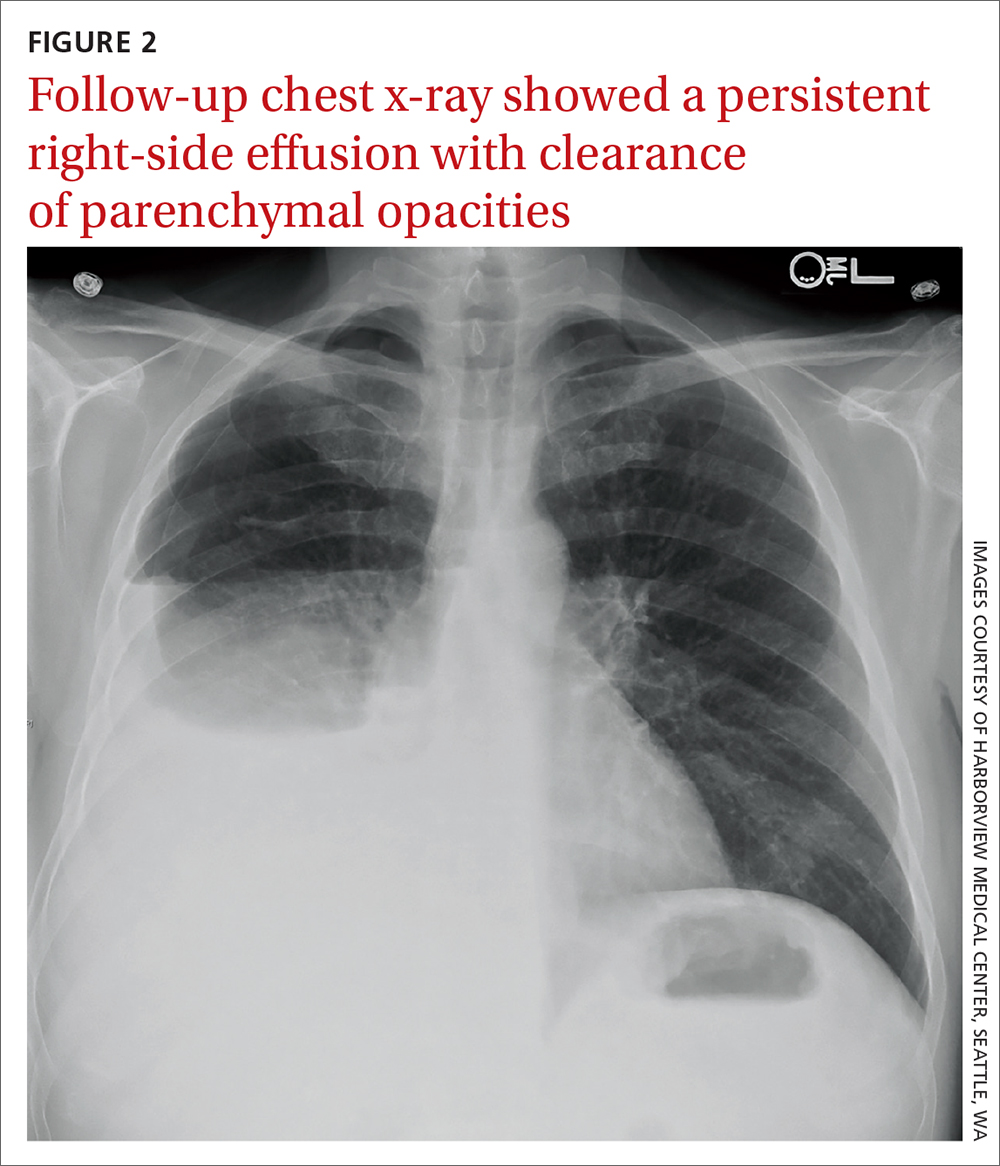

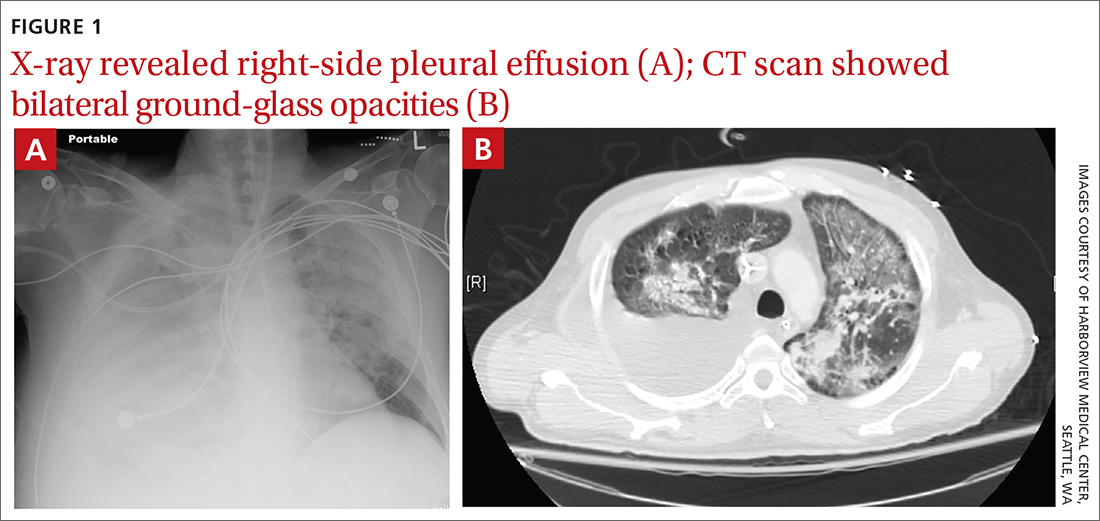

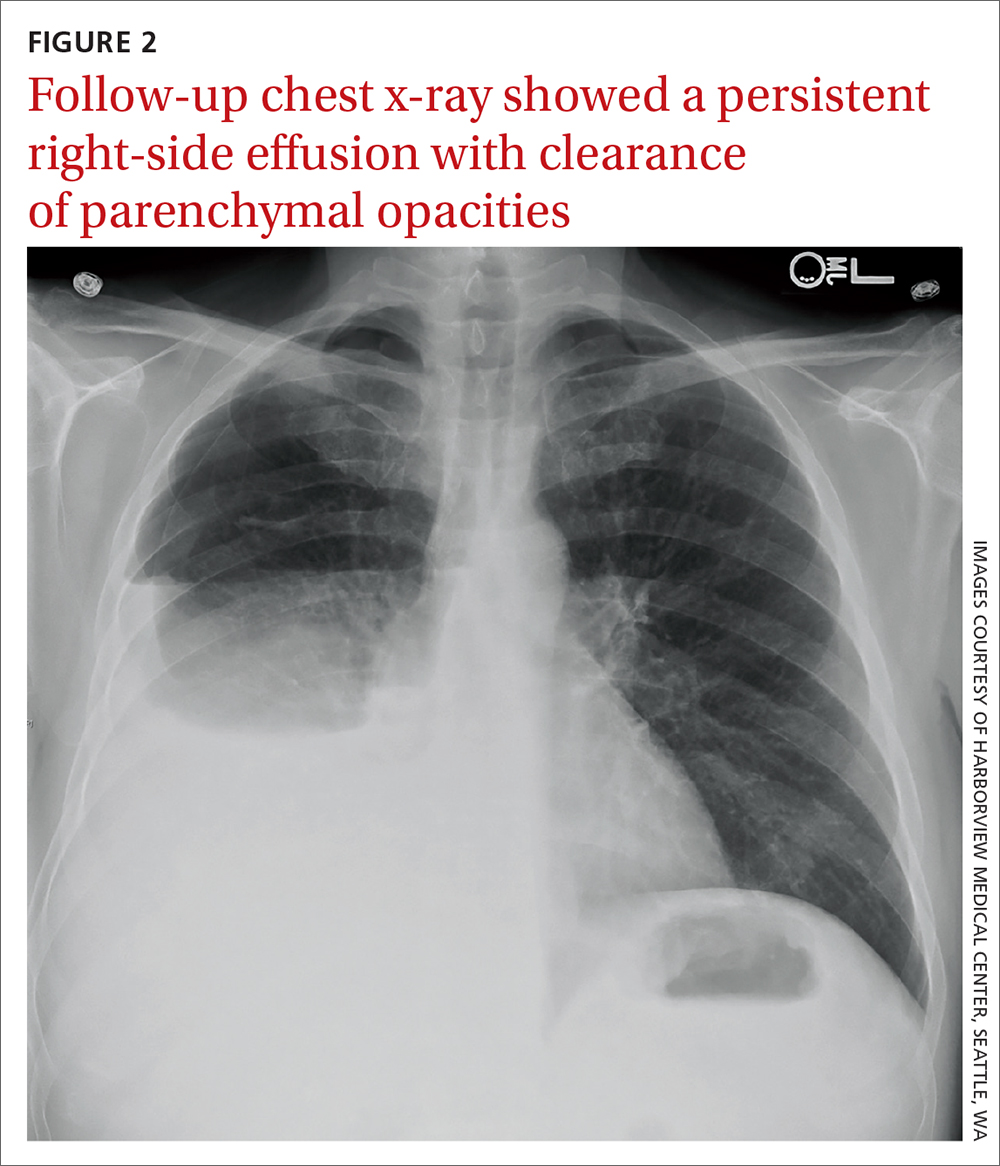

Due to a sulfonamide allergy, our patient was started on primaquine 30 mg/d, clindamycin 600 mg tid, and prednisone 40 mg bid. (The corticosteroid was added because of the severity of the disease.) Three days after starting treatment—and 10 days into his hospital stay—the patient had significant improvement in his respiratory status and was successfully extubated. He underwent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole desensitization and completed a 21-day course of treatment for PCP with complete resolution of respiratory symptoms. Follow-up chest radiograph 2 months later (FIGURE 2) confirmed clearance of opacities.

THE TAKEAWAY

PCP remains a rare disease in patients without the typical immunosuppressive risk factors. However, it should be considered in patients with cirrhosis who develop respiratory failure, especially those with compatible radiographic findings and negative microbiologic evaluation for other, more typical, organisms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tyler Albert, MD, VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, 1660 South Columbian Way, S-111-Pulm, Seattle, WA 98108; [email protected]

1. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487-2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032588

2. Walzer PD, Perl DP, Krogstad DJ, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the United States. Epidemiologic, diagnostic, and clinical features. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:83-93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-1-83

3. Sepkowitz KA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17 suppl 2:S416-422. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s416

4. Al Soub H, Taha RY, El Deeb Y, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a patient without a predisposing illness: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:618-621. doi: 10.1080/00365540410017608

5. Jacobs JL, Libby DM, Winters RA, et al. A cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in adults without predisposing illnesses. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:246-250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240407

6. Ng VL, Yajko DM, McPhaul LW, et al. Evaluation of an indirect fluorescent-antibody stain for detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:975-979. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.975-979.1990

7. Cregan P, Yamamoto A, Lum A, et al. Comparison of four methods for rapid detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2432-2436. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2432-2436.1990

8. Turner D, Schwarz Y, Yust I. Induced sputum for diagnosing Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV patients: new data, new issues. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:204-208. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00035303

9. Smith RL, el-Sadr WM, Lewis ML. Correlation of bronchoalveolar lavage cell populations with clinical severity of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest. 1988;93:60-64. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.60

10. Fleury-Feith J, Van Nhieu JT, Picard C, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage eosinophilia associated with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis in AIDS patients. Comparative study with non-AIDS patients. Chest. 1989;95:1198-1201. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.6.1198

11. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:298-308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1621

12. Toh BH, Roberts-Thomson IC, Mathews JD, et al. Depression of cell-mediated immunity in old age and the immunopathic diseases, lupus erythematosus, chronic hepatitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;14:193-202.

13. Mansharamani NG, Balachandran D, Vernovsky I, et al. Peripheral blood CD4 + T-lymphocyte counts during Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in immunocompromised patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2000;118:712-720. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.712

14. McGovern BH, Golan Y, Lopez M, et al. The impact of cirrhosis on CD4+ T cell counts in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:431-437. doi: 10.1086/509580

15. Bienvenu AL, Traore K, Plekhanova I, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia suspected cases in 604 non-HIV and HIV patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;46:11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.018

16. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385-1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010

17. Lario M, Muñoz L, Ubeda M, et al. Defective thymopoiesis and poor peripheral homeostatic replenishment of T-helper cells cause T-cell lymphopenia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;59:723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.042

THE CASE

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department after vomiting a large volume of blood and was admitted to the intensive care unit. His past medical history was remarkable for untreated chronic hepatitis C resulting from injection drug use and cirrhosis without prior history of esophageal varices.

Due to ongoing hematemesis, he was intubated for airway protection and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with banding of large esophageal varices on hospital day (HD) 1. He was extubated on HD 2 after clinical stability was achieved; however, he became encephalopathic over the subsequent days despite treatment with lactulose. On HD 4, the patient required re-intubation for progressive respiratory failure. Chest imaging revealed a large, simple-appearing right pleural effusion and extensive bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities (FIGURE 1).

Thoracentesis was ordered and revealed transudative pleural fluid; this finding, along with negative infectious studies, was consistent with hepatic hydrothorax. In the setting of initial decompensation, empiric treatment with vancomycin and meropenem was started for suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The patient had persistent fevers that had developed during his hospital stay and pulmonary opacities, despite 72 hours of treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Thus, a diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. BAL cell count and differential revealed 363 nucleated cells/µL, with profound eosinophilia (42% eosinophils, 44% macrophages, 14% neutrophils).

Bacterial and fungal cultures and a viral polymerase chain reaction panel were negative. HIV antibody-antigen and RNA testing were also negative. The patient had no evidence or history of underlying malignancy, autoimmune disease, or recent immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids. Due to consistent imaging findings and lack of improvement with appropriate treatment for bacterial pneumonia, further work-up was pursued.

THE DIAGNOSIS