User login

Shunt diameter predicts liver function after obliteration procedure

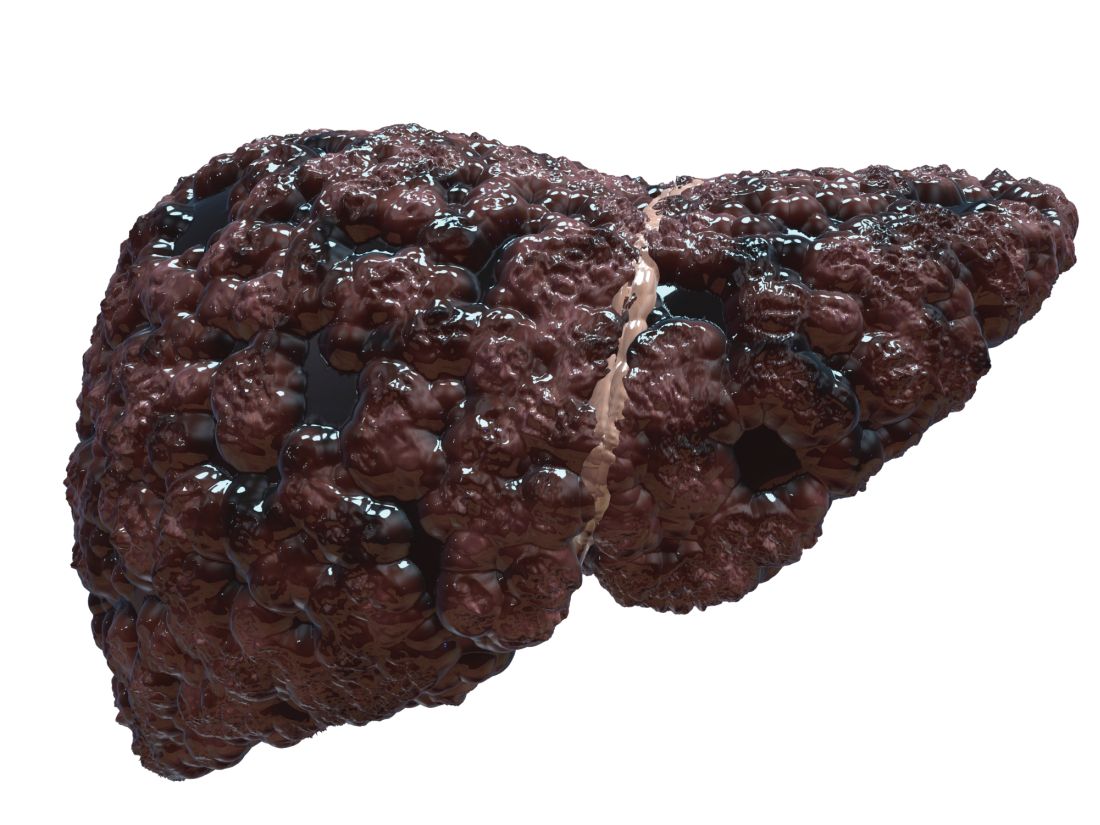

Patients with cirrhosis and larger spontaneous shunt diameters showed a significantly greater increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) following balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration compared to patients with smaller shunt diameters, based on data from 34 adults.

Portal hypertension remains a key source of complications that greatly impact quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, wrote Akihisa Tatsumi, MD, of the University of Yamanashi, Japan, and colleagues. These patients sometimes develop spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) to lower portal pressure, but these natural shunts are an incomplete solution – one that may contribute to liver dysfunction by reducing hepatic portal blood flow. However, the association of SPSS with liver functional reserve remains unclear, the researchers said.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is gaining popularity as a treatment for SPSS in patients with cirrhosis but determining the patients who will benefit from this procedure remains a challenge, the researchers wrote. “Apart from BRTO, some recent studies have reported the impact of the SPSS diameter on the future pathological state of the liver,” which prompted the question of whether SPSS diameter plays a role in predicting portal hypertension–related liver function at baseline and after BRTO, the researchers explained.

In their study, published in JGH Open, the researchers identified 34 cirrhotic patients with SPSS who underwent BRTO at a single center in Japan between 2006 and 2018; all of the patients were available for follow-up at least 6 months after the procedure.

The reasons for BRTO were intractable gastric varices in 18 patients and refractory hepatic encephalopathy with shunt in 16 patients; the mean observation period was 1,182 days (3.24 years). The median age of the patients was 66.5 years, and 53% were male. A majority (76%) of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis with Child-Pugh (CP) scores of B or C, and the maximum diameter of SPSS increased significantly with increased in CP scores (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Overall, at 6 months after BRTO, patients showed significant improvements in liver function from baseline. However, the improvement rate was lower in patients whose shunt diameter was 10 mm or less, and improvement was greatest when the shunt diameter was between 10 mm and 20 mm. “Because the CP score is a significant cofounding factor of the SPSS diameter, we next evaluated the changes in liver function classified by CP scores,” the researchers wrote. In this analysis, the post-BRTO changes in liver function in patients with CP scores of A or B still showed an association between improvement in liver function and larger shunt diameter, but this relationship did not extend to patients with CP scores of C, the researchers said.

A larger shunt diameter also was significantly associated with a greater increase in HVPG after balloon occlusion (P = .005).

“Considering that patients with large SPSS diameters might gain higher portal flow following elevation of HVPG after BRTO, it is natural that the larger the SPSS diameter, the greater the improvements in liver function,” the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. “However, such a clear correlation was evident only when the baseline CP scores were within A or B, and not in C, indicating that the improvement of liver function might not parallel HVPG increase in some CP C patients,” they noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the retrospective design from a single center and its small sample size, the researchers noted. Other limitations included selecting and measuring only the largest SPSS of each patient and lack of data on the impact of SPSS diameter on overall survival, they said.

However, the results suggest that SPSS diameter may serve not only as an indicator of portal hypertension involvement at baseline, but also as a useful clinical predictor of liver function after BRTO, they concluded.

Study supports potential benefits of BRTO

“While the association between SPSS and complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy have been known, data are lacking in regard to characteristics of SPSS that are most dysfunctional, and whether certain patients may benefit from BRTO to occlude these shunts,” Khashayar Farsad, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview.

“The results are in many ways expected based on anticipated impact of larger versus smaller SPSS in overall liver function,” Dr. Farsad noted. “The study, however, does show a nice correlation between several factors involved in liver function and their changes depending on shunt diameter, correlated with changes in the relative venous pressure gradient across the liver,” he said. “Furthermore, the finding that changes were most evident in those with relatively preserved liver function [Child-Turcotte-Pugh grades A and B] suggests less of a relationship between SPSS and liver function in those with more decompensated liver disease,” he added.

“The impact of the study is significantly limited by its retrospective design, small numbers with potential patient heterogeneity, and lack of a control cohort,” said Dr. Farsad. However, “The major take-home message for clinicians is a potential signal that the size of the SPSS at baseline may predict the impact of the SPSS on liver function, and therefore, the potential benefit of a procedure such as BRTO to positively influence this,” he said. “Additional research with larger cohorts and a prospective study design would be warranted, however, before this information would be meaningful in daily clinical decision making,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the Research Program on Hepatitis of the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Farsad disclosed research support from W.L. Gore & Associates, Guerbet LLC, Boston Scientific, and Exelixis; serving as a consultant for NeuWave Medical, Cook Medical, Guerbet LLC, and Eisai, and holding equity in Auxetics Inc.

Patients with cirrhosis and larger spontaneous shunt diameters showed a significantly greater increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) following balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration compared to patients with smaller shunt diameters, based on data from 34 adults.

Portal hypertension remains a key source of complications that greatly impact quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, wrote Akihisa Tatsumi, MD, of the University of Yamanashi, Japan, and colleagues. These patients sometimes develop spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) to lower portal pressure, but these natural shunts are an incomplete solution – one that may contribute to liver dysfunction by reducing hepatic portal blood flow. However, the association of SPSS with liver functional reserve remains unclear, the researchers said.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is gaining popularity as a treatment for SPSS in patients with cirrhosis but determining the patients who will benefit from this procedure remains a challenge, the researchers wrote. “Apart from BRTO, some recent studies have reported the impact of the SPSS diameter on the future pathological state of the liver,” which prompted the question of whether SPSS diameter plays a role in predicting portal hypertension–related liver function at baseline and after BRTO, the researchers explained.

In their study, published in JGH Open, the researchers identified 34 cirrhotic patients with SPSS who underwent BRTO at a single center in Japan between 2006 and 2018; all of the patients were available for follow-up at least 6 months after the procedure.

The reasons for BRTO were intractable gastric varices in 18 patients and refractory hepatic encephalopathy with shunt in 16 patients; the mean observation period was 1,182 days (3.24 years). The median age of the patients was 66.5 years, and 53% were male. A majority (76%) of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis with Child-Pugh (CP) scores of B or C, and the maximum diameter of SPSS increased significantly with increased in CP scores (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Overall, at 6 months after BRTO, patients showed significant improvements in liver function from baseline. However, the improvement rate was lower in patients whose shunt diameter was 10 mm or less, and improvement was greatest when the shunt diameter was between 10 mm and 20 mm. “Because the CP score is a significant cofounding factor of the SPSS diameter, we next evaluated the changes in liver function classified by CP scores,” the researchers wrote. In this analysis, the post-BRTO changes in liver function in patients with CP scores of A or B still showed an association between improvement in liver function and larger shunt diameter, but this relationship did not extend to patients with CP scores of C, the researchers said.

A larger shunt diameter also was significantly associated with a greater increase in HVPG after balloon occlusion (P = .005).

“Considering that patients with large SPSS diameters might gain higher portal flow following elevation of HVPG after BRTO, it is natural that the larger the SPSS diameter, the greater the improvements in liver function,” the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. “However, such a clear correlation was evident only when the baseline CP scores were within A or B, and not in C, indicating that the improvement of liver function might not parallel HVPG increase in some CP C patients,” they noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the retrospective design from a single center and its small sample size, the researchers noted. Other limitations included selecting and measuring only the largest SPSS of each patient and lack of data on the impact of SPSS diameter on overall survival, they said.

However, the results suggest that SPSS diameter may serve not only as an indicator of portal hypertension involvement at baseline, but also as a useful clinical predictor of liver function after BRTO, they concluded.

Study supports potential benefits of BRTO

“While the association between SPSS and complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy have been known, data are lacking in regard to characteristics of SPSS that are most dysfunctional, and whether certain patients may benefit from BRTO to occlude these shunts,” Khashayar Farsad, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview.

“The results are in many ways expected based on anticipated impact of larger versus smaller SPSS in overall liver function,” Dr. Farsad noted. “The study, however, does show a nice correlation between several factors involved in liver function and their changes depending on shunt diameter, correlated with changes in the relative venous pressure gradient across the liver,” he said. “Furthermore, the finding that changes were most evident in those with relatively preserved liver function [Child-Turcotte-Pugh grades A and B] suggests less of a relationship between SPSS and liver function in those with more decompensated liver disease,” he added.

“The impact of the study is significantly limited by its retrospective design, small numbers with potential patient heterogeneity, and lack of a control cohort,” said Dr. Farsad. However, “The major take-home message for clinicians is a potential signal that the size of the SPSS at baseline may predict the impact of the SPSS on liver function, and therefore, the potential benefit of a procedure such as BRTO to positively influence this,” he said. “Additional research with larger cohorts and a prospective study design would be warranted, however, before this information would be meaningful in daily clinical decision making,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the Research Program on Hepatitis of the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Farsad disclosed research support from W.L. Gore & Associates, Guerbet LLC, Boston Scientific, and Exelixis; serving as a consultant for NeuWave Medical, Cook Medical, Guerbet LLC, and Eisai, and holding equity in Auxetics Inc.

Patients with cirrhosis and larger spontaneous shunt diameters showed a significantly greater increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) following balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration compared to patients with smaller shunt diameters, based on data from 34 adults.

Portal hypertension remains a key source of complications that greatly impact quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, wrote Akihisa Tatsumi, MD, of the University of Yamanashi, Japan, and colleagues. These patients sometimes develop spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) to lower portal pressure, but these natural shunts are an incomplete solution – one that may contribute to liver dysfunction by reducing hepatic portal blood flow. However, the association of SPSS with liver functional reserve remains unclear, the researchers said.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is gaining popularity as a treatment for SPSS in patients with cirrhosis but determining the patients who will benefit from this procedure remains a challenge, the researchers wrote. “Apart from BRTO, some recent studies have reported the impact of the SPSS diameter on the future pathological state of the liver,” which prompted the question of whether SPSS diameter plays a role in predicting portal hypertension–related liver function at baseline and after BRTO, the researchers explained.

In their study, published in JGH Open, the researchers identified 34 cirrhotic patients with SPSS who underwent BRTO at a single center in Japan between 2006 and 2018; all of the patients were available for follow-up at least 6 months after the procedure.

The reasons for BRTO were intractable gastric varices in 18 patients and refractory hepatic encephalopathy with shunt in 16 patients; the mean observation period was 1,182 days (3.24 years). The median age of the patients was 66.5 years, and 53% were male. A majority (76%) of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis with Child-Pugh (CP) scores of B or C, and the maximum diameter of SPSS increased significantly with increased in CP scores (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Overall, at 6 months after BRTO, patients showed significant improvements in liver function from baseline. However, the improvement rate was lower in patients whose shunt diameter was 10 mm or less, and improvement was greatest when the shunt diameter was between 10 mm and 20 mm. “Because the CP score is a significant cofounding factor of the SPSS diameter, we next evaluated the changes in liver function classified by CP scores,” the researchers wrote. In this analysis, the post-BRTO changes in liver function in patients with CP scores of A or B still showed an association between improvement in liver function and larger shunt diameter, but this relationship did not extend to patients with CP scores of C, the researchers said.

A larger shunt diameter also was significantly associated with a greater increase in HVPG after balloon occlusion (P = .005).

“Considering that patients with large SPSS diameters might gain higher portal flow following elevation of HVPG after BRTO, it is natural that the larger the SPSS diameter, the greater the improvements in liver function,” the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. “However, such a clear correlation was evident only when the baseline CP scores were within A or B, and not in C, indicating that the improvement of liver function might not parallel HVPG increase in some CP C patients,” they noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the retrospective design from a single center and its small sample size, the researchers noted. Other limitations included selecting and measuring only the largest SPSS of each patient and lack of data on the impact of SPSS diameter on overall survival, they said.

However, the results suggest that SPSS diameter may serve not only as an indicator of portal hypertension involvement at baseline, but also as a useful clinical predictor of liver function after BRTO, they concluded.

Study supports potential benefits of BRTO

“While the association between SPSS and complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy have been known, data are lacking in regard to characteristics of SPSS that are most dysfunctional, and whether certain patients may benefit from BRTO to occlude these shunts,” Khashayar Farsad, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview.

“The results are in many ways expected based on anticipated impact of larger versus smaller SPSS in overall liver function,” Dr. Farsad noted. “The study, however, does show a nice correlation between several factors involved in liver function and their changes depending on shunt diameter, correlated with changes in the relative venous pressure gradient across the liver,” he said. “Furthermore, the finding that changes were most evident in those with relatively preserved liver function [Child-Turcotte-Pugh grades A and B] suggests less of a relationship between SPSS and liver function in those with more decompensated liver disease,” he added.

“The impact of the study is significantly limited by its retrospective design, small numbers with potential patient heterogeneity, and lack of a control cohort,” said Dr. Farsad. However, “The major take-home message for clinicians is a potential signal that the size of the SPSS at baseline may predict the impact of the SPSS on liver function, and therefore, the potential benefit of a procedure such as BRTO to positively influence this,” he said. “Additional research with larger cohorts and a prospective study design would be warranted, however, before this information would be meaningful in daily clinical decision making,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the Research Program on Hepatitis of the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Farsad disclosed research support from W.L. Gore & Associates, Guerbet LLC, Boston Scientific, and Exelixis; serving as a consultant for NeuWave Medical, Cook Medical, Guerbet LLC, and Eisai, and holding equity in Auxetics Inc.

FROM JGH OPEN

Weekend catch-up sleep may help fatty liver

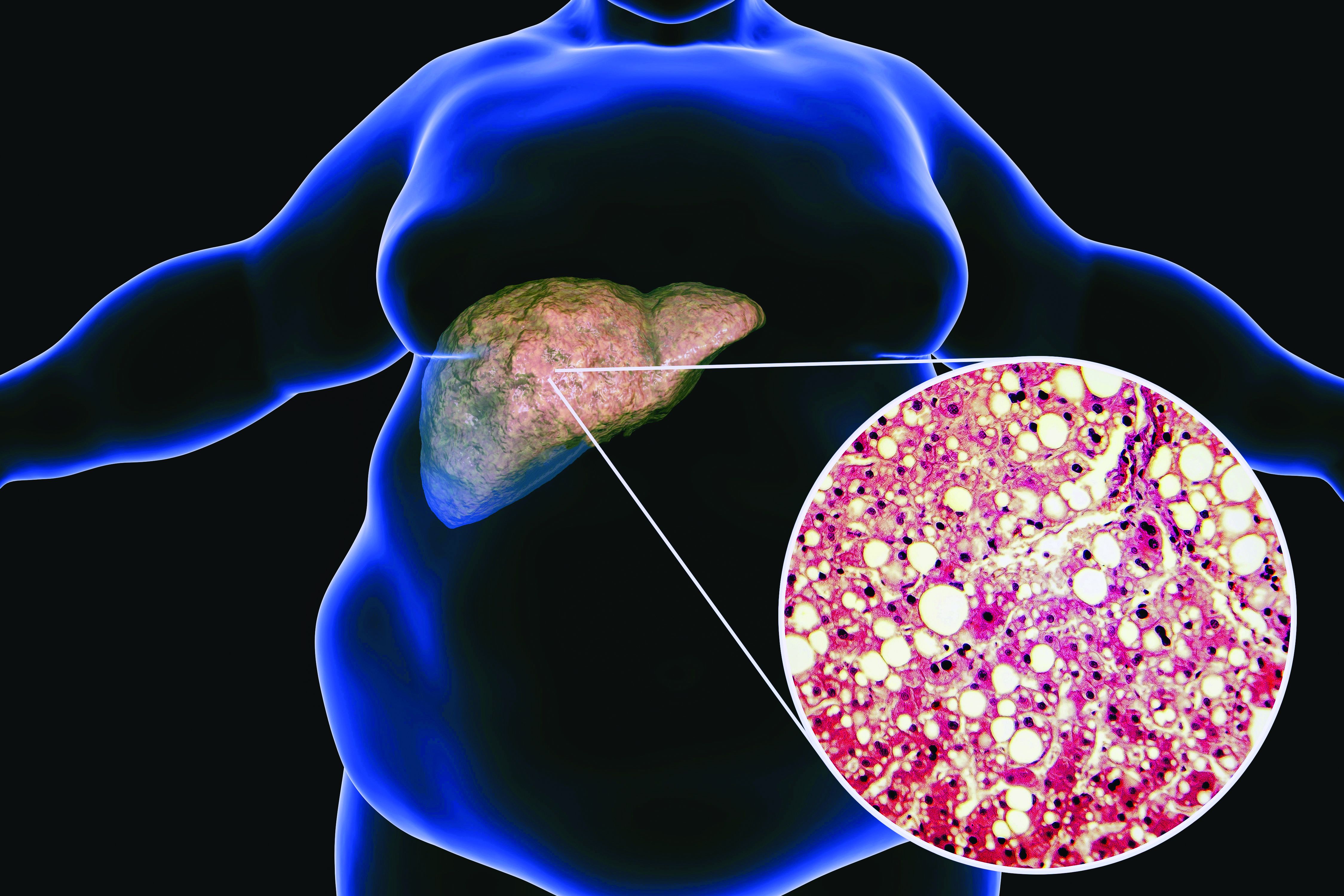

People who don’t get enough sleep during the week may be able to reduce their risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by catching up on the weekends, researchers say.

“Our study revealed that people who get enough sleep have a lower risk of developing NAFLD than those who get insufficient sleep,” Sangheun Lee, MD, PhD, from Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Hepatology.

However, they cautioned that further research is needed to verify their finding.

Previous studies have associated insufficient sleep with obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, as well as liver fibrosis.

A busy weekday schedule can make it harder to get enough sleep, and some people try to compensate by sleeping longer on weekends. Studies so far have produced mixed findings on this strategy, with some showing that more sleep on the weekend reduces the risk for obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, and others showing no effect on metabolic dysregulation or energy balance.

Accessing a nation’s sleep data

To explore the relationship between sleep patterns and NAFLD, Dr. Lee and colleagues analyzed data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys collected from 2008 to 2019. They excluded people aged less than 20 years, those with hepatitis B or C infections, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, shift workers and others who “slept irregularly,” and those who consumed alcohol excessively, leaving a cohort of 101,138 participants.

The survey didn’t distinguish between sleep on weekdays and weekends until 2016, so the researchers divided their findings into two: 68,759 people surveyed from 2008 to 2015 (set 1) and 32,379 surveyed from 2016 to 2019 (set 2).

Set 1 was further divided into those who averaged more than 7 hours of sleep per day and those who slept less than that. Set 2 was divided into three groups: one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did not catch up on weekends, one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did catch up on weekends, and one that averaged more than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week.

The researchers used the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) to determine the presence of a fatty liver, calculated as 8 x (ratio of serum ALT to serum AST) + body mass index (+ 2 for female, + 2 in case of diabetes). An HSI of at least36 was considered an indicator of fatty liver.

Less sleep, more risk

Participants in set 1 slept for a mean of 6.8 hours, with 58.6% sleeping more than 7 hours a day. Those in set 2 slept a mean of 6.9 hours during weekdays, with 59.9% sleeping more than 7 hours. They also slept a mean of 7.7 hours on weekends.

In set 1, sleeping at least7 hours was associated with a 16% lower risk for NAFLD (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.89).

In set 2, sleeping at least 7 hours on weekdays was associated with a 19% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.89). Sleeping at least 7 hours on the weekend was associated with a 22% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.87). Compared with those who slept less than 7 hours throughout the week, those who slept less than 7 hours on weekdays and more than 7 hours on weekends had a 20% lower rate of NAFLD (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.92).

All these associations held true for both men and women.

Why getting your Z’s may have hepatic advantages

One explanation for the link between sleep patterns and NAFLD is that dysregulation of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and norepinephrine are associated with both variations in sleep and NAFLD onset, Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

They also pointed out that a lack of sleep can reduce the secretion of two hormones that promote satiety: leptin and glucagonlike peptide–1. As a result, people who sleep less may eat more and gain weight, which increases the risk for NAFLD.

Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, a professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, who was not involved in the study, noted that it was based on comparing a cross section of a population instead of following the participants over time.

“So, I think it’s an association rather than a cause and effect,” he said in an interview.

The authors don’t report a multivariate analysis to determine whether comorbidities or other characteristics of the patients could explain the association, he pointed out, noting that obesity, for example, can increase the risk for both NAFLD and sleep apnea.

Still, Dr. Singal said, the paper will influence him to mention sleep in the context of lifestyle factors that can affect fatty liver disease. “I’m going to tell my patients, and tell the community physicians to tell their patients, to follow a good sleep hygiene and make sure that they sleep at least 5-7 hours.”

Dr. Singal and the study authors all reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who don’t get enough sleep during the week may be able to reduce their risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by catching up on the weekends, researchers say.

“Our study revealed that people who get enough sleep have a lower risk of developing NAFLD than those who get insufficient sleep,” Sangheun Lee, MD, PhD, from Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Hepatology.

However, they cautioned that further research is needed to verify their finding.

Previous studies have associated insufficient sleep with obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, as well as liver fibrosis.

A busy weekday schedule can make it harder to get enough sleep, and some people try to compensate by sleeping longer on weekends. Studies so far have produced mixed findings on this strategy, with some showing that more sleep on the weekend reduces the risk for obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, and others showing no effect on metabolic dysregulation or energy balance.

Accessing a nation’s sleep data

To explore the relationship between sleep patterns and NAFLD, Dr. Lee and colleagues analyzed data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys collected from 2008 to 2019. They excluded people aged less than 20 years, those with hepatitis B or C infections, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, shift workers and others who “slept irregularly,” and those who consumed alcohol excessively, leaving a cohort of 101,138 participants.

The survey didn’t distinguish between sleep on weekdays and weekends until 2016, so the researchers divided their findings into two: 68,759 people surveyed from 2008 to 2015 (set 1) and 32,379 surveyed from 2016 to 2019 (set 2).

Set 1 was further divided into those who averaged more than 7 hours of sleep per day and those who slept less than that. Set 2 was divided into three groups: one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did not catch up on weekends, one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did catch up on weekends, and one that averaged more than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week.

The researchers used the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) to determine the presence of a fatty liver, calculated as 8 x (ratio of serum ALT to serum AST) + body mass index (+ 2 for female, + 2 in case of diabetes). An HSI of at least36 was considered an indicator of fatty liver.

Less sleep, more risk

Participants in set 1 slept for a mean of 6.8 hours, with 58.6% sleeping more than 7 hours a day. Those in set 2 slept a mean of 6.9 hours during weekdays, with 59.9% sleeping more than 7 hours. They also slept a mean of 7.7 hours on weekends.

In set 1, sleeping at least7 hours was associated with a 16% lower risk for NAFLD (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.89).

In set 2, sleeping at least 7 hours on weekdays was associated with a 19% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.89). Sleeping at least 7 hours on the weekend was associated with a 22% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.87). Compared with those who slept less than 7 hours throughout the week, those who slept less than 7 hours on weekdays and more than 7 hours on weekends had a 20% lower rate of NAFLD (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.92).

All these associations held true for both men and women.

Why getting your Z’s may have hepatic advantages

One explanation for the link between sleep patterns and NAFLD is that dysregulation of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and norepinephrine are associated with both variations in sleep and NAFLD onset, Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

They also pointed out that a lack of sleep can reduce the secretion of two hormones that promote satiety: leptin and glucagonlike peptide–1. As a result, people who sleep less may eat more and gain weight, which increases the risk for NAFLD.

Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, a professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, who was not involved in the study, noted that it was based on comparing a cross section of a population instead of following the participants over time.

“So, I think it’s an association rather than a cause and effect,” he said in an interview.

The authors don’t report a multivariate analysis to determine whether comorbidities or other characteristics of the patients could explain the association, he pointed out, noting that obesity, for example, can increase the risk for both NAFLD and sleep apnea.

Still, Dr. Singal said, the paper will influence him to mention sleep in the context of lifestyle factors that can affect fatty liver disease. “I’m going to tell my patients, and tell the community physicians to tell their patients, to follow a good sleep hygiene and make sure that they sleep at least 5-7 hours.”

Dr. Singal and the study authors all reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who don’t get enough sleep during the week may be able to reduce their risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by catching up on the weekends, researchers say.

“Our study revealed that people who get enough sleep have a lower risk of developing NAFLD than those who get insufficient sleep,” Sangheun Lee, MD, PhD, from Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Hepatology.

However, they cautioned that further research is needed to verify their finding.

Previous studies have associated insufficient sleep with obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, as well as liver fibrosis.

A busy weekday schedule can make it harder to get enough sleep, and some people try to compensate by sleeping longer on weekends. Studies so far have produced mixed findings on this strategy, with some showing that more sleep on the weekend reduces the risk for obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, and others showing no effect on metabolic dysregulation or energy balance.

Accessing a nation’s sleep data

To explore the relationship between sleep patterns and NAFLD, Dr. Lee and colleagues analyzed data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys collected from 2008 to 2019. They excluded people aged less than 20 years, those with hepatitis B or C infections, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, shift workers and others who “slept irregularly,” and those who consumed alcohol excessively, leaving a cohort of 101,138 participants.

The survey didn’t distinguish between sleep on weekdays and weekends until 2016, so the researchers divided their findings into two: 68,759 people surveyed from 2008 to 2015 (set 1) and 32,379 surveyed from 2016 to 2019 (set 2).

Set 1 was further divided into those who averaged more than 7 hours of sleep per day and those who slept less than that. Set 2 was divided into three groups: one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did not catch up on weekends, one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did catch up on weekends, and one that averaged more than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week.

The researchers used the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) to determine the presence of a fatty liver, calculated as 8 x (ratio of serum ALT to serum AST) + body mass index (+ 2 for female, + 2 in case of diabetes). An HSI of at least36 was considered an indicator of fatty liver.

Less sleep, more risk

Participants in set 1 slept for a mean of 6.8 hours, with 58.6% sleeping more than 7 hours a day. Those in set 2 slept a mean of 6.9 hours during weekdays, with 59.9% sleeping more than 7 hours. They also slept a mean of 7.7 hours on weekends.

In set 1, sleeping at least7 hours was associated with a 16% lower risk for NAFLD (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.89).

In set 2, sleeping at least 7 hours on weekdays was associated with a 19% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.89). Sleeping at least 7 hours on the weekend was associated with a 22% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.87). Compared with those who slept less than 7 hours throughout the week, those who slept less than 7 hours on weekdays and more than 7 hours on weekends had a 20% lower rate of NAFLD (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.92).

All these associations held true for both men and women.

Why getting your Z’s may have hepatic advantages

One explanation for the link between sleep patterns and NAFLD is that dysregulation of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and norepinephrine are associated with both variations in sleep and NAFLD onset, Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

They also pointed out that a lack of sleep can reduce the secretion of two hormones that promote satiety: leptin and glucagonlike peptide–1. As a result, people who sleep less may eat more and gain weight, which increases the risk for NAFLD.

Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, a professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, who was not involved in the study, noted that it was based on comparing a cross section of a population instead of following the participants over time.

“So, I think it’s an association rather than a cause and effect,” he said in an interview.

The authors don’t report a multivariate analysis to determine whether comorbidities or other characteristics of the patients could explain the association, he pointed out, noting that obesity, for example, can increase the risk for both NAFLD and sleep apnea.

Still, Dr. Singal said, the paper will influence him to mention sleep in the context of lifestyle factors that can affect fatty liver disease. “I’m going to tell my patients, and tell the community physicians to tell their patients, to follow a good sleep hygiene and make sure that they sleep at least 5-7 hours.”

Dr. Singal and the study authors all reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF HEPATOLOGY

Freiburg index accurately predicts survival in liver procedure

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

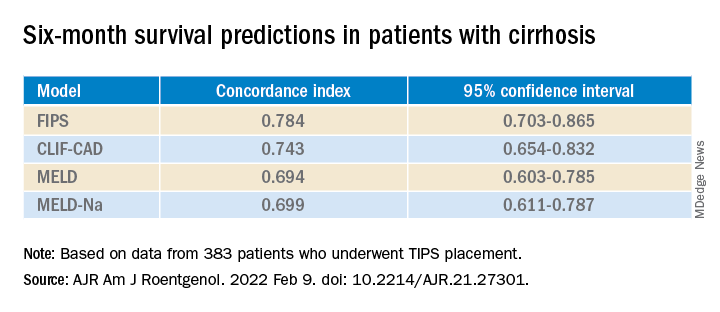

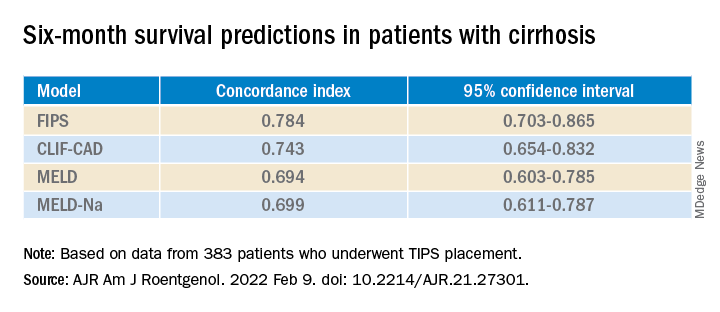

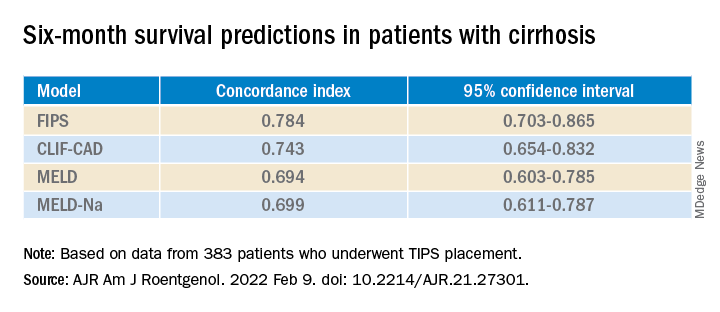

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ROENTGENOLOGY

Novel scoring system emerges for alcoholic hepatitis mortality

A new scoring system proved more accurate than several other available models at predicting the 30-day mortality risk for patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), according to new data.

The system, called the Mortality Index for Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis (MIAAH), was created by a team of Mayo Clinic researchers, who published their results in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Among the currently available prognostic models for assessing AH severity are the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD); the Age, serum Bilirubin, International normalized ratio, and serum Creatinine (ABIC) score; the Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF); and the Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS). However, these models have poor accuracy, with the area under the curve between 0.71 and 0.77.

By comparison, the new model has an accuracy of 86% in predicting 30-day mortality for AH, said coauthor Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, Sioux Falls.

“It’s a better predictor of the outcome, and that’s what sets it apart,” he told this news organization. “I think providers and patients will benefit.”

He said accuracy in determining the likelihood of death can help clinicians better determine treatment options and prepare patients and their families.

Camille Kezer, MD, a Mayo Clinic resident internist and first author of the paper, said in a statement, “MIAAH also has the advantage of performing well in patients, regardless of whether they’ve been treated with steroids, which makes it generalizable.”

Creating and validating the MIAAH

Researchers analyzed the health records of 266 eligible patients diagnosed with AH between 1998 and 2018 at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. The patients collectively had a 30-day mortality rate of 19.2%.

They then studied the effect of several variables, of which the following were found to be significantly associated with mortality: age (P = .002), blood urea nitrogen (P = .003), albumin (P = .01), bilirubin (P = .02), and international normalized ratio (P = .001).

Mayo researchers built the MIAAH model using these variables and found that it was able to achieve a C statistic of 0.86, which translates into its being able to accurately predict mortality more than 86% of the time. When tested in the initial cohort of 266 patients, MIAAH had a significantly superior C statistic compared with several other available models, such as the MELD, MDF, and GAHS, although not for the ABIC.

The researchers then tested the MIAAH model in a validation cohort of 249 patients from health care centers at the University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls, and the University of Kansas, Lawrence. In this cohort, the MIAAH’s C statistic decreased to 0.73, which remained significantly more accurate than the MDF but was comparable to that found with the MELD.

Helping with transplant decisions

There are no pharmacologic treatments that can reduce 90-day mortality in severe cases of AH, and only a small survival benefit at 30 days has been reported with prednisolone use.

With a shortage of liver donors, many centers still require 6 months of alcohol abstinence for transplant consideration, although exceptions are sometimes made for cases of early transplant.

A model that more accurately predicts who is at the highest risk of dying within a month can help clinicians decide how best to proceed, Dr. Singal said.

Paul Martin, MD, chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases, Mandel Chair in gastroenterology, and professor of medicine at the University of Miami, told this news organization that the model is potentially important in light of the rising prevalence of AH.

“The numbers of patients with AH are unequivocally increasing and often in young patients,” he noted, presenting difficult choices of who to treat with steroids and who to refer for a transplant.

“This model is certainly timely,” he said. “We need more accuracy in predicting which patients will recover with medical therapy and which patients won’t in the absence of a liver transplant.”

He noted, however, that the study’s retrospective design requires that it’s validated prospectively: “not only looking at the outcome in terms of mortality of patients, but its potential utility in identifying candidates for liver transplantation who are not going to recover on their own.”

He said it was unlikely that the model would replace others, particularly MELD, which is ingrained in practices in the United States and other countries, but may instead have a complementary role.

Dr. Singal, Dr. Kezer, and Dr. Martin report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new scoring system proved more accurate than several other available models at predicting the 30-day mortality risk for patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), according to new data.

The system, called the Mortality Index for Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis (MIAAH), was created by a team of Mayo Clinic researchers, who published their results in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Among the currently available prognostic models for assessing AH severity are the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD); the Age, serum Bilirubin, International normalized ratio, and serum Creatinine (ABIC) score; the Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF); and the Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS). However, these models have poor accuracy, with the area under the curve between 0.71 and 0.77.

By comparison, the new model has an accuracy of 86% in predicting 30-day mortality for AH, said coauthor Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, Sioux Falls.

“It’s a better predictor of the outcome, and that’s what sets it apart,” he told this news organization. “I think providers and patients will benefit.”

He said accuracy in determining the likelihood of death can help clinicians better determine treatment options and prepare patients and their families.

Camille Kezer, MD, a Mayo Clinic resident internist and first author of the paper, said in a statement, “MIAAH also has the advantage of performing well in patients, regardless of whether they’ve been treated with steroids, which makes it generalizable.”

Creating and validating the MIAAH

Researchers analyzed the health records of 266 eligible patients diagnosed with AH between 1998 and 2018 at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. The patients collectively had a 30-day mortality rate of 19.2%.

They then studied the effect of several variables, of which the following were found to be significantly associated with mortality: age (P = .002), blood urea nitrogen (P = .003), albumin (P = .01), bilirubin (P = .02), and international normalized ratio (P = .001).

Mayo researchers built the MIAAH model using these variables and found that it was able to achieve a C statistic of 0.86, which translates into its being able to accurately predict mortality more than 86% of the time. When tested in the initial cohort of 266 patients, MIAAH had a significantly superior C statistic compared with several other available models, such as the MELD, MDF, and GAHS, although not for the ABIC.

The researchers then tested the MIAAH model in a validation cohort of 249 patients from health care centers at the University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls, and the University of Kansas, Lawrence. In this cohort, the MIAAH’s C statistic decreased to 0.73, which remained significantly more accurate than the MDF but was comparable to that found with the MELD.

Helping with transplant decisions

There are no pharmacologic treatments that can reduce 90-day mortality in severe cases of AH, and only a small survival benefit at 30 days has been reported with prednisolone use.

With a shortage of liver donors, many centers still require 6 months of alcohol abstinence for transplant consideration, although exceptions are sometimes made for cases of early transplant.

A model that more accurately predicts who is at the highest risk of dying within a month can help clinicians decide how best to proceed, Dr. Singal said.

Paul Martin, MD, chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases, Mandel Chair in gastroenterology, and professor of medicine at the University of Miami, told this news organization that the model is potentially important in light of the rising prevalence of AH.

“The numbers of patients with AH are unequivocally increasing and often in young patients,” he noted, presenting difficult choices of who to treat with steroids and who to refer for a transplant.

“This model is certainly timely,” he said. “We need more accuracy in predicting which patients will recover with medical therapy and which patients won’t in the absence of a liver transplant.”

He noted, however, that the study’s retrospective design requires that it’s validated prospectively: “not only looking at the outcome in terms of mortality of patients, but its potential utility in identifying candidates for liver transplantation who are not going to recover on their own.”

He said it was unlikely that the model would replace others, particularly MELD, which is ingrained in practices in the United States and other countries, but may instead have a complementary role.

Dr. Singal, Dr. Kezer, and Dr. Martin report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new scoring system proved more accurate than several other available models at predicting the 30-day mortality risk for patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), according to new data.

The system, called the Mortality Index for Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis (MIAAH), was created by a team of Mayo Clinic researchers, who published their results in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Among the currently available prognostic models for assessing AH severity are the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD); the Age, serum Bilirubin, International normalized ratio, and serum Creatinine (ABIC) score; the Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF); and the Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS). However, these models have poor accuracy, with the area under the curve between 0.71 and 0.77.

By comparison, the new model has an accuracy of 86% in predicting 30-day mortality for AH, said coauthor Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, Sioux Falls.

“It’s a better predictor of the outcome, and that’s what sets it apart,” he told this news organization. “I think providers and patients will benefit.”

He said accuracy in determining the likelihood of death can help clinicians better determine treatment options and prepare patients and their families.

Camille Kezer, MD, a Mayo Clinic resident internist and first author of the paper, said in a statement, “MIAAH also has the advantage of performing well in patients, regardless of whether they’ve been treated with steroids, which makes it generalizable.”

Creating and validating the MIAAH

Researchers analyzed the health records of 266 eligible patients diagnosed with AH between 1998 and 2018 at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. The patients collectively had a 30-day mortality rate of 19.2%.

They then studied the effect of several variables, of which the following were found to be significantly associated with mortality: age (P = .002), blood urea nitrogen (P = .003), albumin (P = .01), bilirubin (P = .02), and international normalized ratio (P = .001).

Mayo researchers built the MIAAH model using these variables and found that it was able to achieve a C statistic of 0.86, which translates into its being able to accurately predict mortality more than 86% of the time. When tested in the initial cohort of 266 patients, MIAAH had a significantly superior C statistic compared with several other available models, such as the MELD, MDF, and GAHS, although not for the ABIC.

The researchers then tested the MIAAH model in a validation cohort of 249 patients from health care centers at the University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls, and the University of Kansas, Lawrence. In this cohort, the MIAAH’s C statistic decreased to 0.73, which remained significantly more accurate than the MDF but was comparable to that found with the MELD.

Helping with transplant decisions

There are no pharmacologic treatments that can reduce 90-day mortality in severe cases of AH, and only a small survival benefit at 30 days has been reported with prednisolone use.

With a shortage of liver donors, many centers still require 6 months of alcohol abstinence for transplant consideration, although exceptions are sometimes made for cases of early transplant.

A model that more accurately predicts who is at the highest risk of dying within a month can help clinicians decide how best to proceed, Dr. Singal said.

Paul Martin, MD, chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases, Mandel Chair in gastroenterology, and professor of medicine at the University of Miami, told this news organization that the model is potentially important in light of the rising prevalence of AH.

“The numbers of patients with AH are unequivocally increasing and often in young patients,” he noted, presenting difficult choices of who to treat with steroids and who to refer for a transplant.

“This model is certainly timely,” he said. “We need more accuracy in predicting which patients will recover with medical therapy and which patients won’t in the absence of a liver transplant.”

He noted, however, that the study’s retrospective design requires that it’s validated prospectively: “not only looking at the outcome in terms of mortality of patients, but its potential utility in identifying candidates for liver transplantation who are not going to recover on their own.”

He said it was unlikely that the model would replace others, particularly MELD, which is ingrained in practices in the United States and other countries, but may instead have a complementary role.

Dr. Singal, Dr. Kezer, and Dr. Martin report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

Universal hepatitis B screening, vaccination deemed cost effective for pregnant women

Screening for hepatitis B antibodies and vaccinating pregnant women without immunity appears to be a cost-effective health measure, according to a recent analysis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Malavika Prabhu, MD, of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and department of obstetrics and gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said in an interview that the impetus to conduct the study came from the idea that hepatitis B is a concern throughout a woman’s life, but not necessarily during pregnancy. While vaccination is not routine during pregnancy, guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that at-risk women should be screened and vaccinated for hepatitis B during pregnancy.

“What we thought made more sense just from thinking about other principles of prenatal care was that it would make sense for us to screen, see who’s susceptible, counsel them on the risk of hepatitis B, and then vaccinate them in the course of the pregnancy,” Dr. Prabhu said.

After writing a commentary arguing in favor of universal screening and vaccination, she and her colleagues noted it was still unclear whether that approach was cost effective, she said. “Health care costs in this country are so expensive at baseline that, as we continue to add more things to health care, we have to make sure that it’s value added.”

Dr. Prabhu and her colleagues evaluated a theoretical cohort of 3.6 million pregnant women in the United States and created a decision-analytic model to determine how universal hepatitis B surface antibody screening and vaccination for hepatitis B affected factors such as cost, cost-effectiveness, and outcomes. They included hepatitis B virus cases as well as long-term problems associated with hepatitis B infection such as hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant, and death. Assumptions of the model were that 84% of the women would undergo the screening, 61% would receive the vaccine, and 90% would seroconvert after the vaccine series, and were based on probabilities from other studies.

The cost-effectiveness ratio was calculated as the total cost and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) relative to the lifetime of the woman after the index pregnancy, with $50,000 per QALY set as the willingness-to-pay threshold. The researchers also performed an additional analysis and simulations to estimate which variables had the most effect, and an additional model was created to estimate the effect of universal screening and vaccination if at-risk patients were removed.

Dr. Prabhu and colleagues found the universal screening and vaccination program was cost effective, with 1,702 fewer cases of hepatitis B, 11 fewer deaths, 7 fewer decompensated cirrhosis cases, and 4 fewer liver transplants in their model. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was $1,890 per QALY, and the total increased lifetime cohort cost was $13,841,889. The researchers said the model held up in scenarios where there was a high level of hepatitis B immunity, and when at-risk women were removed from the model.

“While it does increase some costs to the health care system to screen everyone and vaccinate those susceptible; overall, it would cost more to not do that because we’re avoiding all of those long-term devastating health outcomes by vaccinating in pregnancy,” Dr. Prabhu said in an interview.

Hepatitis B screening and vaccination for all pregnant women?

Is universal hepatitis B screening and vaccination for pregnant women an upcoming change in prenatal care? In a related editorial, Martina L. Badell, MD, of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, emphasized the hepatitis B vaccine’s safety and effectiveness during pregnancy based on prior studies and compared a universal hepatitis B screening and vaccination program for pregnant women to how clinicians screen universally for rubella as standard of care in this group.

“Owing to the success of rubella vaccination campaigns, today there are fewer than 10 cases of rubella in the United States annually, and, since 2012, all of these cases have been in persons infected when living in or traveling to other countries,” she wrote. “Approximately 850,000 people are living with hepatitis B infection in the United States, and approximately 21,900 acute hepatitis B infections occurred in 2015. Despite the very different prevalence in these infections, we currently screen pregnant and nonpregnant patients for rubella immunity but not hepatitis B.”

If real-world studies bear out that a hepatitis B universal screening and vaccination program is cost effective, guidelines on who should be screened and vaccinated might need to be reconsidered, Dr. Prabhu said. Although following women for decades to see whether hepatitis B screening and vaccination is cost effective is impractical, “a lot of medicine has been predicated on risk-based strategies and risk stratifying, and there is a lot of value to approaching patients like that,” she explained.

How an ob.gyn. determines whether a patient is high risk and qualifies for hepatitis B vaccination under current guidelines is made more complicated by the large amount of information covered in a prenatal visit. There is a “laundry list” of risk factors to consider, and “patients are just meeting you for the first time, and so they may not feel comfortable completely sharing what their risk factors may or may not be,” Dr. Prabhu said. In addition, they may not know the risk factors of their partners.

Under guidelines where all pregnant women are screened and vaccinated for hepatitis B regardless of risk, “it doesn’t harm a woman to check one extra blood test when she’s already having this bevy of blood tests at the first prenatal visit,” she said.

Clinicians may be more aware of the need to add hepatitis B screening to prenatal care given that routine hepatitis C screening for pregnant women was recently released by ACOG as a practice advisory. “I think hepatitis is a little bit more on the forefront of the obstetrician or prenatal care provider’s mind as a result of that recent shift,” she said.

“A lot of women only really access care and access consistent care during their pregnancy, either due to insurance reasons or work reasons. People do things for their developing fetus that they might not do for themselves,” Dr. Prabhu said. “It’s a unique opportunity to have the time to build a relationship, build some trust in the health care system and also educate women about their health and what they can do to keep themselves in good health.

“It’s more than just about the next 9 months and keeping you and your baby safe, so I think there’s a real opportunity for us to think about the public health and the long-term health of a woman.”

One author reported receiving funding from UpToDate; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Badell reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Screening for hepatitis B antibodies and vaccinating pregnant women without immunity appears to be a cost-effective health measure, according to a recent analysis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Malavika Prabhu, MD, of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and department of obstetrics and gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said in an interview that the impetus to conduct the study came from the idea that hepatitis B is a concern throughout a woman’s life, but not necessarily during pregnancy. While vaccination is not routine during pregnancy, guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that at-risk women should be screened and vaccinated for hepatitis B during pregnancy.

“What we thought made more sense just from thinking about other principles of prenatal care was that it would make sense for us to screen, see who’s susceptible, counsel them on the risk of hepatitis B, and then vaccinate them in the course of the pregnancy,” Dr. Prabhu said.

After writing a commentary arguing in favor of universal screening and vaccination, she and her colleagues noted it was still unclear whether that approach was cost effective, she said. “Health care costs in this country are so expensive at baseline that, as we continue to add more things to health care, we have to make sure that it’s value added.”

Dr. Prabhu and her colleagues evaluated a theoretical cohort of 3.6 million pregnant women in the United States and created a decision-analytic model to determine how universal hepatitis B surface antibody screening and vaccination for hepatitis B affected factors such as cost, cost-effectiveness, and outcomes. They included hepatitis B virus cases as well as long-term problems associated with hepatitis B infection such as hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant, and death. Assumptions of the model were that 84% of the women would undergo the screening, 61% would receive the vaccine, and 90% would seroconvert after the vaccine series, and were based on probabilities from other studies.

The cost-effectiveness ratio was calculated as the total cost and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) relative to the lifetime of the woman after the index pregnancy, with $50,000 per QALY set as the willingness-to-pay threshold. The researchers also performed an additional analysis and simulations to estimate which variables had the most effect, and an additional model was created to estimate the effect of universal screening and vaccination if at-risk patients were removed.

Dr. Prabhu and colleagues found the universal screening and vaccination program was cost effective, with 1,702 fewer cases of hepatitis B, 11 fewer deaths, 7 fewer decompensated cirrhosis cases, and 4 fewer liver transplants in their model. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was $1,890 per QALY, and the total increased lifetime cohort cost was $13,841,889. The researchers said the model held up in scenarios where there was a high level of hepatitis B immunity, and when at-risk women were removed from the model.

“While it does increase some costs to the health care system to screen everyone and vaccinate those susceptible; overall, it would cost more to not do that because we’re avoiding all of those long-term devastating health outcomes by vaccinating in pregnancy,” Dr. Prabhu said in an interview.

Hepatitis B screening and vaccination for all pregnant women?

Is universal hepatitis B screening and vaccination for pregnant women an upcoming change in prenatal care? In a related editorial, Martina L. Badell, MD, of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, emphasized the hepatitis B vaccine’s safety and effectiveness during pregnancy based on prior studies and compared a universal hepatitis B screening and vaccination program for pregnant women to how clinicians screen universally for rubella as standard of care in this group.

“Owing to the success of rubella vaccination campaigns, today there are fewer than 10 cases of rubella in the United States annually, and, since 2012, all of these cases have been in persons infected when living in or traveling to other countries,” she wrote. “Approximately 850,000 people are living with hepatitis B infection in the United States, and approximately 21,900 acute hepatitis B infections occurred in 2015. Despite the very different prevalence in these infections, we currently screen pregnant and nonpregnant patients for rubella immunity but not hepatitis B.”

If real-world studies bear out that a hepatitis B universal screening and vaccination program is cost effective, guidelines on who should be screened and vaccinated might need to be reconsidered, Dr. Prabhu said. Although following women for decades to see whether hepatitis B screening and vaccination is cost effective is impractical, “a lot of medicine has been predicated on risk-based strategies and risk stratifying, and there is a lot of value to approaching patients like that,” she explained.

How an ob.gyn. determines whether a patient is high risk and qualifies for hepatitis B vaccination under current guidelines is made more complicated by the large amount of information covered in a prenatal visit. There is a “laundry list” of risk factors to consider, and “patients are just meeting you for the first time, and so they may not feel comfortable completely sharing what their risk factors may or may not be,” Dr. Prabhu said. In addition, they may not know the risk factors of their partners.

Under guidelines where all pregnant women are screened and vaccinated for hepatitis B regardless of risk, “it doesn’t harm a woman to check one extra blood test when she’s already having this bevy of blood tests at the first prenatal visit,” she said.

Clinicians may be more aware of the need to add hepatitis B screening to prenatal care given that routine hepatitis C screening for pregnant women was recently released by ACOG as a practice advisory. “I think hepatitis is a little bit more on the forefront of the obstetrician or prenatal care provider’s mind as a result of that recent shift,” she said.

“A lot of women only really access care and access consistent care during their pregnancy, either due to insurance reasons or work reasons. People do things for their developing fetus that they might not do for themselves,” Dr. Prabhu said. “It’s a unique opportunity to have the time to build a relationship, build some trust in the health care system and also educate women about their health and what they can do to keep themselves in good health.

“It’s more than just about the next 9 months and keeping you and your baby safe, so I think there’s a real opportunity for us to think about the public health and the long-term health of a woman.”

One author reported receiving funding from UpToDate; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Badell reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Screening for hepatitis B antibodies and vaccinating pregnant women without immunity appears to be a cost-effective health measure, according to a recent analysis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Malavika Prabhu, MD, of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and department of obstetrics and gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said in an interview that the impetus to conduct the study came from the idea that hepatitis B is a concern throughout a woman’s life, but not necessarily during pregnancy. While vaccination is not routine during pregnancy, guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that at-risk women should be screened and vaccinated for hepatitis B during pregnancy.

“What we thought made more sense just from thinking about other principles of prenatal care was that it would make sense for us to screen, see who’s susceptible, counsel them on the risk of hepatitis B, and then vaccinate them in the course of the pregnancy,” Dr. Prabhu said.

After writing a commentary arguing in favor of universal screening and vaccination, she and her colleagues noted it was still unclear whether that approach was cost effective, she said. “Health care costs in this country are so expensive at baseline that, as we continue to add more things to health care, we have to make sure that it’s value added.”

Dr. Prabhu and her colleagues evaluated a theoretical cohort of 3.6 million pregnant women in the United States and created a decision-analytic model to determine how universal hepatitis B surface antibody screening and vaccination for hepatitis B affected factors such as cost, cost-effectiveness, and outcomes. They included hepatitis B virus cases as well as long-term problems associated with hepatitis B infection such as hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant, and death. Assumptions of the model were that 84% of the women would undergo the screening, 61% would receive the vaccine, and 90% would seroconvert after the vaccine series, and were based on probabilities from other studies.