User login

Delivering Palliative Care in a Community Hospital: Experiences and Lessons Learned from the Front Lines

From the Division of Palliative Care, Butler Health System, Butler, PA (Drs. Stein, Reefer, Selvaggi, Ms. Doverspike); the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Rajagopal); and the Duke Cancer Institute and Duke Fuqua School of Business, Durham, NC (Dr. Kamal).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe an approach to develop a community-centric palliative care program in a rural community health system and to review data collected over the program’s first year.

- Methods: We describe the underlying foundations of our program development including the health system’s prioritization of a palliative care program, funding opportunities, collaboration with community supports, and the importance of building a team and program that reflects a community’s needs. Data were collected through a program-maintained spreadsheet and a data monitoring system available through the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance.

- Results: 516 new inpatient consultations were seen during the first year, for a penetration of 3.7%. The demographics of the patients who received consultation reflect that of the surrounding community. Over 50% of patients seen within the first year died, and hospice utilization at home and within facilities and inpatient hospice units increased. In addition, 79% of the patients seen by the palliative care team had a confirmed code status of do not resuscitate and do not intubate.

- Conclusions: Butler Health System’s approach to development of a palliative care program has resulted in increasing utilization of palliative care services in the hospital. Having hospital administration support, community support, and understanding the individualized needs of a community has been essential for the program’s expansion.

Key words: palliative care; program development; community hospital; rural.

Since its inception, palliative care has been committed to providing specialty-level consultation services to individuals with serious illness and their loved ones. The field has focused heavily on growth and acceptance, consistently moving upstream with regards to illness trajectory, across diseases, and across demographic variables such as age (eg, pediatric quality of life programs) and race (eg, community outreach programs addressing racial disparities in hospice use). An important frontier that remains challenging for much of the field is expansion into the community setting, where resources, implicit acceptance, and patient populations may vary.

As health system leaders appreciate the positive impacts palliative medicine on patient care and care quality, barriers to implementing palliative care programs in community hospitals must be addressed in ways tailored to the unique needs of smaller organizations and their communities. The goal of this paper is to outline the approach taken to develop Butler Health System’s community-centric palliative care program, describe our program’s underlying foundation rooted in community supports, and recount steps we have taken thus far to impact patient care in our hospital, health system, and community through the program’s first year.

Community Hospital Palliative Care—The Necessity and the Challenges

Palliative care has made strides in its growth and acceptance in the last decade; yet, the distribution of that growth has been skewed. Although 67% of hospitals now report access to specialist palliative care programs, most of the 148% growth over the last decade has been actualized in larger hospitals. Ninety percent of hospitals with greater than 300 beds report palliative care service availability whereas only 56% of small hospitals were identified to have this specialty care [1].

The inequity of access is also seen in other countries. A recent Canadian study retrospectively examined access to care of 23,860 deceased patients in Nova Scotia. Although they found 40.9% of study subjects were enrolled in a palliative care program at urban, academic centers, patients in a rural setting were only a third as likely to be enrolled in a palliative care program [2]. This access gap has important effects on patient-level outcomes, as evidence has consistently demonstrated that patients in rural settings who receive palliative care have decreased unnecessary hospitalizations and less in-hospital deaths [3].

While evidence of improved outcomes is strong, important barriers stand in the way. In a 2013 study, 374 health care providers at 236 rural hospitals in 7 states were interviewed to determine barriers to providing palliative care in rural settings. Barriers identified include a lack of administrative support, access to basic palliative care training for primary care physicians, and limited relationships to hospices [4]. Additional challenges include lack of access to tertiary-level specialty clinicians, access to and misconceptions about prescription medications, transportation for patients and providers, and incorporating a patient’s community supports [5–7].

Proposed Solutions

Techniques to improve palliative care access for rural and community centers that have been previously reviewed in the literature include videoconferencing with tertiary care experts in palliative care and education through small community-level lectures [8–10]. Goals of rural and suburban palliative care programs are broadly similar to programs at academic medical centers; however, few studies have identified impact of palliative medicine on patient care in community settings. In one suburban practice, a study found that patients were more likely to die at home if they had multiple caregivers, increased length of time under palliative care, and older age upon referral [11].

The United States has few large-scale pilot programs attempting to address the palliative needs of a more suburban or rural population. Of these, the Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative developed by Stratis Health is perhaps the best publicized. Stratis Health developed and led an 18-month learning collaborative from October 2008 to April 2010 through which community teams developed or improved palliative care services. Through this initiative, a community-based health care practice model was developed that took advantage of the strong interrelationships within rural communities. After 18 months, 6 out of 10 rural Minnesota communities had formal palliative care programs, and 8 to 9 out of 10 had capabilities to at least address advance directives as well as provider and community education [12]. In another initiative, the NIH established a new suburban clinic with tertiary providers specifically for resource intensive, underserved patients [13]. The clinic was established by partnering with a service that was already in place in the community. Twenty-seven patients were seen within 7 months. The most common consults were patients with numerous comorbidities and chronic pain rather than terminal diagnoses. Given the intensive need of these patients, the authors felt that a consultation service and an interdisciplinary team that included psychosocial/spiritual/social work providers offered the most efficient method of delivering advanced palliative care needs.

The research regarding both solutions to challenges and novel methods of addressing the care gap remains sparse as evidenced by the conclusions of multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses and the inability of the Cochrane review to find papers meeting inclusion criteria regarding techniques of community support in palliative care [14,15]. There remains a need to identify practical techniques of implementing palliative care in rural and suburban settings.

The Butler Health System Experience

In August 2015, we set out to start the first hospital-based palliative care consultation service in the Butler Health System. The health system is a nonprofit, single-hospital system anchored by Butler Memorial Hospital, a 294-bed community hospital located within a rural Pennsylvania county of 186,000 residents, 35 miles north of Pittsburgh. Butler County consists of a predominantly white, non-Hispanic population with over 15% of the residents being older than 65 years of age. The median household income is $61,000 earned primarily through blue collar occupations [16]. Driven by 53 employed primary care physicians, the health system provides services for 75,000 patients at sites covering an area of 4000 square miles. The hospital provides general medical, critical, surgical and subspecialty care and behavior health services as a regional referral center for 4 surrounding rural counties, accepting 12,500 inpatient admissions annually. A hospitalist service admits the majority of oncology patients, and the intensive care unit (ICU) is an open unit, where patients are admitted to the hospitalist, primary care, or surgical service.

While no formal needs assessment was performed prior to program development, perceptions of inadequate pain control, overuse of naloxone, underutilization of hospice services, and lack of consistent quality in end-of-life care were identified. These concerns were voiced at the levels of direct patient care on the floors, and by nursing and physician hospital leadership. Prior to our program, the chief medical officer attended the national Center to Advance Palliative Care conference to better understand the field of palliative care and its impact on improving quality of care. Concurrently, our health system was expanding its inpatient capabilities (eg, advanced neurologic and cardiac services), resulting in admissions with increased disease severity and illness complexity. With the vision of improved patient care, prioritizing quality end-of-life care and symptom management, the hospital board and administration overwhelmingly supported the development of the palliative care program, philosophically and financially.

Laying a Foundation—Funding, Collaboration, and Team Building

Funding and staffing are 2 important factors when building any program. Sources of funding for palliative care programs may include hospital support, billing revenue, grants, and philanthropy. Program development was a priority for the hospital and community. To help offset costs, efforts to raise financial support focused on utilizing the health system’s annual fundraising events. Through the generosity of individuals in the community, the hospital’s annual gala event, and donations from the hospital’s auxiliary, a total of $230,000 was raised prior to program initiation. Funds budgeted through direct hospital support and fundraising were allocated towards hiring palliative care team members and community marketing projects.

The hospital’s surrounding community is fortunate to have 2 local inpatient hospice facilities, and these relationships were imperative to providing quality end-of-life care preceding our palliative care program. A formal partnership was previously established with one while the other remains an important referral facility due to its proximity to the hospital. These hospice services are encouraged to participate in our weekly palliative care interdisciplinary team meetings. Their incorporation has improved coordination, continuity, and translation of care upon patient discharge from the acute hospital setting. Additionally, the relationships have been beneficial in tracking patients’ outcomes and data collection.

The standard structure of a palliative care team described by the Joint Commission and National Consensus Panel for Palliative Care consists of a physician, registered nurse or advanced practice provider, chaplaincy, and social work. Despite this recommendation, less than 40% of surveyed hospitals met the criteria, and less than 25% have dedicated funding to cover these positions [17]. Upon inception of our palliative care program, 2.6 funded full-time equivalents (FTEs) were allocated. These positions included a physician (1.0 FTE), a physician assistant (1.0 FTE), and a part time palliative care social worker (0.6 FTE). The 2015 National Palliative Care Registry found that 3.2 funded FTEs per 10,000 admissions is the average for hospitals with 150 to 299 beds [17]. The uncertainty of the utilization and consult volume, and the limited amount of qualified palliative care trained practitioners, resulted in the palliative program starting below this mean at 2.1 funded FTEs per 10,000 admissions. All the funded positions were located on site at the hospital. The pre-existing volunteer hospital chaplain service was identified as the pastoral care component for the program.

Increased FTEs have been associated with increased palliative care service penetration and ultimately in decreased time to consult [18]. In response to increasing consult volumes, concerns for delays in time to consult, and in preparation for expansion to an outpatient service, the palliative care department acquired an additional funded physician FTE (1.0). Ultimately the service reached a total of 3.6 FTE for inpatient services during its first 12 months; proportionately this resulted in an increase to 2.9 FTE per 10,000 admissions based on the yearly admission rate of 12,500 patients.

Educational Outreach

The success of a palliative care program depends on other clinicians’ acceptance and referral to the clinical program. We took a 2-pronged approach, focusing on both hospital-based and community-based education. The hospital-based nursing education included 30-minute presentations on general overviews of palliative care, differences between palliative care and hospice, and acute symptom management at the end of life. The palliative care team presented to all medical, surgical, and intensive care units and encompassed all shifts of nursing staff. These lectures included pre- and post-tests to assess for impact and feedback. Similar educational presentations, as well as an hour-long presentation on opioids and palliative care, were available for physicians for CME opportunities. We also distributed concise palliative care referral packets to outpatient primary care offices through the health system’s marketing team. The referral packets included examples of diagnoses, clinical scenarios, and symptoms to assist in the physicians’ understanding of palliative care services. The palliative care team also met with clinic office managers to discuss the program and answer questions.

There were also educational opportunities for patients and families in our community. Taking advantage of previously developed partnerships between the hospital system and local media outlets, the palliative care team performed local radio spots to educate the community on topics including an overview of palliative care, how to request palliative care, and the difference between palliative care and hospice care. We partnered with a local hospice agency and developed a well-received bereavement seminar for patients, family members, and employees and included the topic of advanced care planning.

Data Collection

We collect data using 2 different tools: a self-maintained spreadsheet shared between our palliative care clinicians, and a collective data tool (QDACT) included in our membership with and maintained by the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance. Data collected and tracked in our spreadsheet includes date of consult, patient age, primary and secondary diagnoses, disposition, goals of care discussions, date of death, and 30-day readmissions. Through the QDACT data monitoring program, we are tracking and analyzing quality measures including symptom assessment and management and code status conversion. The QDACT database also provides financial data specific to our institution such as cost savings based on our billing, readmission rates, and length of stay.

Results

Projections, Volumes, and Penetration

Prior to the start of our program, our chief medical office used Center to Advance Palliative Care tools to project inpatient consultation volumes at our institution. Variables that are recommended by this center to guide projections include number of hospital admissions per year, hospital occupancy, disposition to hospice, as well as generalized estimations of inpatient mortality rates. Based on our data, it was expected that our program would receive 204 new inpatient consults in our first year, and 774 follow-up visits. Our actual new inpatient consults totaled 516, with 919 follow-up visits. Palliative care penetration (percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by the palliative care team) our first year was 3.7% (Table 1).

Consultation Demographics

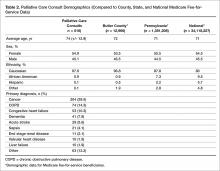

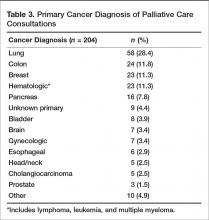

The demographics of the patients seen by the palliative care team reflect that of Butler County’s Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) population (Table 2); however, differences were seen at the state and national level with regard to ethnicity (Table 2).

Almost half of consultations (49%) were placed by the hospitalist service. Since the ICU is an open unit, critical care consults are not adequately reflected by analysis of the ordering physician alone. Analysis of consultation location revealed that 27% of inpatient consults were located within the ICU.

Patient Outcomes and Disposition

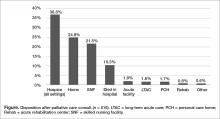

Outcomes and discharge data from the first year were collected and reviewed. Ten percent of the patients seen by palliative care died in the hospital, and 51% of patients that were seen by palliative care died within the program’s first year. Thirty-seven percent of patients discharged from the hospital utilized hospice services at home, in residential nursing facility, or at an inpatient hospice unit. The remaining 53% were discharged without hospice services to home or facility (Figure).

Hospice utilization by the health system increased during our first year. Compared to the 2014 calendar year, there were a total of 263 referrals for hospice services. During the first year of the palliative care program, which started August 2015, there were a total of 293 referrals. Of the 293 total hospice referrals, 190 (64.8%) of these referrals were for patients seen by the palliative care team.

Change of Code Status

Code status and changes in codes status data were collected. Of 462 individual patients prior to or at the time of palliative care consults, 43% were full code, 4% limited code, 8% unknown status, and 45% Do Not Resuscitate. After palliative care consult, 61% of the patients who were previously full/limited/unknown converted to do not resuscitate and do not intubate status. In total, 79% of patients seen by palliative care had a confirmed code status of Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Intubate status after consult.

Discussion

In our first year, our palliative care program exceeded the expected number of inpatient consults, corresponding with a penetration of 3.7%. With the increase of funded FTEs, preliminary data shows that the department’s penetration continues to rise remaining consistent with the data and expectations [18]. During the second year, it is anticipated that over 600 inpatient palliative care consultations will be performed with an estimated penetration of 4%. This increasing penetration reflects the rising utilization of palliative care within our hospital. Since inception of the program, the service has expanded into an outpatient clinic 2 days per week. The palliative care clinic is staffed by a registered nurse (funded 0.6 FTE) and covered by the same physicians and physician assistant providing the inpatient services. The department acquired an unfunded but designated chaplaincy volunteer to assist with patients’ spiritual needs. We believe that the success of our program during the first year was related to multiple factors: a focus of integration and education by the palliative care department, health system administration buy-in, and identification of surrounding community needs.

In addition to patient care, our palliative care department also prioritizes “tangible” impacts to better establish our contributions to the health system. We have done this through participation on hospital committees, hospital policy revision teams, and by developing innovative solutions such as a terminal extubation protocol and order set for our ICU. The health system and its administration have recognized the importance of educating nursing and physician staff on palliative care services, and have supported these continued efforts alongside our clinical obligations.

Concurrent with administration buy-in, financial supports for our palliative care services were initially supplemented by the health system. Our department understands the importance of recognizing limitations of resources in communities and their hospitals. In efforts to minimize the department’s impact on our own health system’s financial resources, we have strived to offset our costs. We helped the hospital system meet pay-for-performance palliative care metrics set by the large local insurers resulting in financial hospital reimbursement valued at $600,000 in 2016.

The question of how the program may translate into other communities raises a major limitation: the homogeneity our population. The community surrounding the hospital is primarily Caucasian, with minimal representation of minority populations. While the patient population seen by our palliative care team is reflective of our surrounding county, it does not represent Medicare FFS beneficiaries on a national level or many other types of community hospitals across the country. Variations of ethnicity, age, diagnoses, and faith are fundamental, which highlights the importance of understanding the community in which a program is developed.

The rising trajectory of our palliative care service utilization has prompted a discussion of future endeavors for our program. Expectations for a continued shortage of hospice and palliative care physicians [19] and concerns for practitioner burnout [20] underlie our thoughtful approach to expansion of inpatient and outpatient services. At this time, potential projects include a consultation trigger system and incorporation of palliative care providers in ICU rounding, as well as possible expansion of outpatient services through implantation of an advanced practitioner into surrounding nursing homes and primary care offices.

We have found a growing utilization of our program at Butler Health System. Our first year experience has highlighted the importance of identifying community and hospital administrative champions as a foundation. Additionally, understanding the specific characteristics of one’s surrounding community may allow for improved integration and acceptance of palliative care in a community setting. Our program continues to work with the health system, community, and philanthropic organizations to expand the ever-growing need for palliative care services.

1. Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, et al. The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med 2016;19:8–15.

2. Lavergne MR, Lethbridge L, Johnston G, et al. Examining palliative care program use and place of death in rural and urban contexts: a Canadian population-based study using linked data. Rural Remote Health 2015;15:3134.

3. Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g3496.

4. Fink RM, Oman KS, Youngwerth J, et al. A palliative care needs assessment of rural hospitals. J Palliat Med 2013;16:638–44.

5. Dumont S, Jacobs P, Turcotte V, et al. Palliative care costs in Canada: A descriptive comparison of studies of urban and rural patients near end of life. J Palliat Med 2015;29:908–17.

6. Kaasalainen S, Brazil K, Williams A, et al. Nurses' experiences providing palliative care to individuals living in rural communities: aspects of the physical residential setting. Rural Remote Health 2014;14:2728.

7. Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. J Palliat Med 2004;18:525–42.

8. Ray RA, Fried O, Lindsay D. Palliative care professional education via video conference builds confidence to deliver palliative care in rural and remote locations. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:272.

9. Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, et al. Systematic review of palliative care in the rural setting. Cancer Control 2015;22:450–64.

10. Akiyama M, Hirai K, Takebayashi T, et al. The effects of community-wide dissemination of information on perceptions of palliative care, knowledge about opioids, and sense of security among cancer patients, their families, and the general public. Support Care Cancer 2016;24: 347–56.

11. Maida V. Factors that promote success in home palliative care: a study of a large suburban palliative care practice. J Palliat Care 2002;18:282–6.

12. Ceronsky L, Shearer J, Weng K, et al. Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative: building palliative care capacity in rural Minnesota. J Palliat Med 2013;16:310–3.

13. Aggarwal SK, Ghosh A, Cheng MJ, et al. Initiating pain and palliative care outpatient services for the suburban underserved in Montgomery County, Maryland: Lessons learned at the NIH Clinical Center and MobileMed. Palliat Support Care 2015;16:1–6.

14. Rainsford S, MacLeod RD, Glasgow NJ. Place of death in rural palliative care: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 2016;30:745–63.

15. Horey D, Street AF, O'Connor M, et al. Training and supportive programs for palliative care volunteers in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 Jul 20;(7):CD009500.

16. The United States Census Bureau: QuickFacts: Butler County, Pennsylvania. Accessed 10 Mar 2017 at www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/42019,00.

17. Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, et al. Few hospital palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff 2016;35:1690–7.

18. Dumanovsky T, Rogers M, Spragens LH, et al. Impact of Staffing on Access to Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2015 Dec; 18(12). Pages 998-999.

19. Lupu D, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899–911.

20. Kamal AH, Bull JK, Wolf SP, et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:690–6.

From the Division of Palliative Care, Butler Health System, Butler, PA (Drs. Stein, Reefer, Selvaggi, Ms. Doverspike); the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Rajagopal); and the Duke Cancer Institute and Duke Fuqua School of Business, Durham, NC (Dr. Kamal).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe an approach to develop a community-centric palliative care program in a rural community health system and to review data collected over the program’s first year.

- Methods: We describe the underlying foundations of our program development including the health system’s prioritization of a palliative care program, funding opportunities, collaboration with community supports, and the importance of building a team and program that reflects a community’s needs. Data were collected through a program-maintained spreadsheet and a data monitoring system available through the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance.

- Results: 516 new inpatient consultations were seen during the first year, for a penetration of 3.7%. The demographics of the patients who received consultation reflect that of the surrounding community. Over 50% of patients seen within the first year died, and hospice utilization at home and within facilities and inpatient hospice units increased. In addition, 79% of the patients seen by the palliative care team had a confirmed code status of do not resuscitate and do not intubate.

- Conclusions: Butler Health System’s approach to development of a palliative care program has resulted in increasing utilization of palliative care services in the hospital. Having hospital administration support, community support, and understanding the individualized needs of a community has been essential for the program’s expansion.

Key words: palliative care; program development; community hospital; rural.

Since its inception, palliative care has been committed to providing specialty-level consultation services to individuals with serious illness and their loved ones. The field has focused heavily on growth and acceptance, consistently moving upstream with regards to illness trajectory, across diseases, and across demographic variables such as age (eg, pediatric quality of life programs) and race (eg, community outreach programs addressing racial disparities in hospice use). An important frontier that remains challenging for much of the field is expansion into the community setting, where resources, implicit acceptance, and patient populations may vary.

As health system leaders appreciate the positive impacts palliative medicine on patient care and care quality, barriers to implementing palliative care programs in community hospitals must be addressed in ways tailored to the unique needs of smaller organizations and their communities. The goal of this paper is to outline the approach taken to develop Butler Health System’s community-centric palliative care program, describe our program’s underlying foundation rooted in community supports, and recount steps we have taken thus far to impact patient care in our hospital, health system, and community through the program’s first year.

Community Hospital Palliative Care—The Necessity and the Challenges

Palliative care has made strides in its growth and acceptance in the last decade; yet, the distribution of that growth has been skewed. Although 67% of hospitals now report access to specialist palliative care programs, most of the 148% growth over the last decade has been actualized in larger hospitals. Ninety percent of hospitals with greater than 300 beds report palliative care service availability whereas only 56% of small hospitals were identified to have this specialty care [1].

The inequity of access is also seen in other countries. A recent Canadian study retrospectively examined access to care of 23,860 deceased patients in Nova Scotia. Although they found 40.9% of study subjects were enrolled in a palliative care program at urban, academic centers, patients in a rural setting were only a third as likely to be enrolled in a palliative care program [2]. This access gap has important effects on patient-level outcomes, as evidence has consistently demonstrated that patients in rural settings who receive palliative care have decreased unnecessary hospitalizations and less in-hospital deaths [3].

While evidence of improved outcomes is strong, important barriers stand in the way. In a 2013 study, 374 health care providers at 236 rural hospitals in 7 states were interviewed to determine barriers to providing palliative care in rural settings. Barriers identified include a lack of administrative support, access to basic palliative care training for primary care physicians, and limited relationships to hospices [4]. Additional challenges include lack of access to tertiary-level specialty clinicians, access to and misconceptions about prescription medications, transportation for patients and providers, and incorporating a patient’s community supports [5–7].

Proposed Solutions

Techniques to improve palliative care access for rural and community centers that have been previously reviewed in the literature include videoconferencing with tertiary care experts in palliative care and education through small community-level lectures [8–10]. Goals of rural and suburban palliative care programs are broadly similar to programs at academic medical centers; however, few studies have identified impact of palliative medicine on patient care in community settings. In one suburban practice, a study found that patients were more likely to die at home if they had multiple caregivers, increased length of time under palliative care, and older age upon referral [11].

The United States has few large-scale pilot programs attempting to address the palliative needs of a more suburban or rural population. Of these, the Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative developed by Stratis Health is perhaps the best publicized. Stratis Health developed and led an 18-month learning collaborative from October 2008 to April 2010 through which community teams developed or improved palliative care services. Through this initiative, a community-based health care practice model was developed that took advantage of the strong interrelationships within rural communities. After 18 months, 6 out of 10 rural Minnesota communities had formal palliative care programs, and 8 to 9 out of 10 had capabilities to at least address advance directives as well as provider and community education [12]. In another initiative, the NIH established a new suburban clinic with tertiary providers specifically for resource intensive, underserved patients [13]. The clinic was established by partnering with a service that was already in place in the community. Twenty-seven patients were seen within 7 months. The most common consults were patients with numerous comorbidities and chronic pain rather than terminal diagnoses. Given the intensive need of these patients, the authors felt that a consultation service and an interdisciplinary team that included psychosocial/spiritual/social work providers offered the most efficient method of delivering advanced palliative care needs.

The research regarding both solutions to challenges and novel methods of addressing the care gap remains sparse as evidenced by the conclusions of multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses and the inability of the Cochrane review to find papers meeting inclusion criteria regarding techniques of community support in palliative care [14,15]. There remains a need to identify practical techniques of implementing palliative care in rural and suburban settings.

The Butler Health System Experience

In August 2015, we set out to start the first hospital-based palliative care consultation service in the Butler Health System. The health system is a nonprofit, single-hospital system anchored by Butler Memorial Hospital, a 294-bed community hospital located within a rural Pennsylvania county of 186,000 residents, 35 miles north of Pittsburgh. Butler County consists of a predominantly white, non-Hispanic population with over 15% of the residents being older than 65 years of age. The median household income is $61,000 earned primarily through blue collar occupations [16]. Driven by 53 employed primary care physicians, the health system provides services for 75,000 patients at sites covering an area of 4000 square miles. The hospital provides general medical, critical, surgical and subspecialty care and behavior health services as a regional referral center for 4 surrounding rural counties, accepting 12,500 inpatient admissions annually. A hospitalist service admits the majority of oncology patients, and the intensive care unit (ICU) is an open unit, where patients are admitted to the hospitalist, primary care, or surgical service.

While no formal needs assessment was performed prior to program development, perceptions of inadequate pain control, overuse of naloxone, underutilization of hospice services, and lack of consistent quality in end-of-life care were identified. These concerns were voiced at the levels of direct patient care on the floors, and by nursing and physician hospital leadership. Prior to our program, the chief medical officer attended the national Center to Advance Palliative Care conference to better understand the field of palliative care and its impact on improving quality of care. Concurrently, our health system was expanding its inpatient capabilities (eg, advanced neurologic and cardiac services), resulting in admissions with increased disease severity and illness complexity. With the vision of improved patient care, prioritizing quality end-of-life care and symptom management, the hospital board and administration overwhelmingly supported the development of the palliative care program, philosophically and financially.

Laying a Foundation—Funding, Collaboration, and Team Building

Funding and staffing are 2 important factors when building any program. Sources of funding for palliative care programs may include hospital support, billing revenue, grants, and philanthropy. Program development was a priority for the hospital and community. To help offset costs, efforts to raise financial support focused on utilizing the health system’s annual fundraising events. Through the generosity of individuals in the community, the hospital’s annual gala event, and donations from the hospital’s auxiliary, a total of $230,000 was raised prior to program initiation. Funds budgeted through direct hospital support and fundraising were allocated towards hiring palliative care team members and community marketing projects.

The hospital’s surrounding community is fortunate to have 2 local inpatient hospice facilities, and these relationships were imperative to providing quality end-of-life care preceding our palliative care program. A formal partnership was previously established with one while the other remains an important referral facility due to its proximity to the hospital. These hospice services are encouraged to participate in our weekly palliative care interdisciplinary team meetings. Their incorporation has improved coordination, continuity, and translation of care upon patient discharge from the acute hospital setting. Additionally, the relationships have been beneficial in tracking patients’ outcomes and data collection.

The standard structure of a palliative care team described by the Joint Commission and National Consensus Panel for Palliative Care consists of a physician, registered nurse or advanced practice provider, chaplaincy, and social work. Despite this recommendation, less than 40% of surveyed hospitals met the criteria, and less than 25% have dedicated funding to cover these positions [17]. Upon inception of our palliative care program, 2.6 funded full-time equivalents (FTEs) were allocated. These positions included a physician (1.0 FTE), a physician assistant (1.0 FTE), and a part time palliative care social worker (0.6 FTE). The 2015 National Palliative Care Registry found that 3.2 funded FTEs per 10,000 admissions is the average for hospitals with 150 to 299 beds [17]. The uncertainty of the utilization and consult volume, and the limited amount of qualified palliative care trained practitioners, resulted in the palliative program starting below this mean at 2.1 funded FTEs per 10,000 admissions. All the funded positions were located on site at the hospital. The pre-existing volunteer hospital chaplain service was identified as the pastoral care component for the program.

Increased FTEs have been associated with increased palliative care service penetration and ultimately in decreased time to consult [18]. In response to increasing consult volumes, concerns for delays in time to consult, and in preparation for expansion to an outpatient service, the palliative care department acquired an additional funded physician FTE (1.0). Ultimately the service reached a total of 3.6 FTE for inpatient services during its first 12 months; proportionately this resulted in an increase to 2.9 FTE per 10,000 admissions based on the yearly admission rate of 12,500 patients.

Educational Outreach

The success of a palliative care program depends on other clinicians’ acceptance and referral to the clinical program. We took a 2-pronged approach, focusing on both hospital-based and community-based education. The hospital-based nursing education included 30-minute presentations on general overviews of palliative care, differences between palliative care and hospice, and acute symptom management at the end of life. The palliative care team presented to all medical, surgical, and intensive care units and encompassed all shifts of nursing staff. These lectures included pre- and post-tests to assess for impact and feedback. Similar educational presentations, as well as an hour-long presentation on opioids and palliative care, were available for physicians for CME opportunities. We also distributed concise palliative care referral packets to outpatient primary care offices through the health system’s marketing team. The referral packets included examples of diagnoses, clinical scenarios, and symptoms to assist in the physicians’ understanding of palliative care services. The palliative care team also met with clinic office managers to discuss the program and answer questions.

There were also educational opportunities for patients and families in our community. Taking advantage of previously developed partnerships between the hospital system and local media outlets, the palliative care team performed local radio spots to educate the community on topics including an overview of palliative care, how to request palliative care, and the difference between palliative care and hospice care. We partnered with a local hospice agency and developed a well-received bereavement seminar for patients, family members, and employees and included the topic of advanced care planning.

Data Collection

We collect data using 2 different tools: a self-maintained spreadsheet shared between our palliative care clinicians, and a collective data tool (QDACT) included in our membership with and maintained by the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance. Data collected and tracked in our spreadsheet includes date of consult, patient age, primary and secondary diagnoses, disposition, goals of care discussions, date of death, and 30-day readmissions. Through the QDACT data monitoring program, we are tracking and analyzing quality measures including symptom assessment and management and code status conversion. The QDACT database also provides financial data specific to our institution such as cost savings based on our billing, readmission rates, and length of stay.

Results

Projections, Volumes, and Penetration

Prior to the start of our program, our chief medical office used Center to Advance Palliative Care tools to project inpatient consultation volumes at our institution. Variables that are recommended by this center to guide projections include number of hospital admissions per year, hospital occupancy, disposition to hospice, as well as generalized estimations of inpatient mortality rates. Based on our data, it was expected that our program would receive 204 new inpatient consults in our first year, and 774 follow-up visits. Our actual new inpatient consults totaled 516, with 919 follow-up visits. Palliative care penetration (percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by the palliative care team) our first year was 3.7% (Table 1).

Consultation Demographics

The demographics of the patients seen by the palliative care team reflect that of Butler County’s Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) population (Table 2); however, differences were seen at the state and national level with regard to ethnicity (Table 2).

Almost half of consultations (49%) were placed by the hospitalist service. Since the ICU is an open unit, critical care consults are not adequately reflected by analysis of the ordering physician alone. Analysis of consultation location revealed that 27% of inpatient consults were located within the ICU.

Patient Outcomes and Disposition

Outcomes and discharge data from the first year were collected and reviewed. Ten percent of the patients seen by palliative care died in the hospital, and 51% of patients that were seen by palliative care died within the program’s first year. Thirty-seven percent of patients discharged from the hospital utilized hospice services at home, in residential nursing facility, or at an inpatient hospice unit. The remaining 53% were discharged without hospice services to home or facility (Figure).

Hospice utilization by the health system increased during our first year. Compared to the 2014 calendar year, there were a total of 263 referrals for hospice services. During the first year of the palliative care program, which started August 2015, there were a total of 293 referrals. Of the 293 total hospice referrals, 190 (64.8%) of these referrals were for patients seen by the palliative care team.

Change of Code Status

Code status and changes in codes status data were collected. Of 462 individual patients prior to or at the time of palliative care consults, 43% were full code, 4% limited code, 8% unknown status, and 45% Do Not Resuscitate. After palliative care consult, 61% of the patients who were previously full/limited/unknown converted to do not resuscitate and do not intubate status. In total, 79% of patients seen by palliative care had a confirmed code status of Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Intubate status after consult.

Discussion

In our first year, our palliative care program exceeded the expected number of inpatient consults, corresponding with a penetration of 3.7%. With the increase of funded FTEs, preliminary data shows that the department’s penetration continues to rise remaining consistent with the data and expectations [18]. During the second year, it is anticipated that over 600 inpatient palliative care consultations will be performed with an estimated penetration of 4%. This increasing penetration reflects the rising utilization of palliative care within our hospital. Since inception of the program, the service has expanded into an outpatient clinic 2 days per week. The palliative care clinic is staffed by a registered nurse (funded 0.6 FTE) and covered by the same physicians and physician assistant providing the inpatient services. The department acquired an unfunded but designated chaplaincy volunteer to assist with patients’ spiritual needs. We believe that the success of our program during the first year was related to multiple factors: a focus of integration and education by the palliative care department, health system administration buy-in, and identification of surrounding community needs.

In addition to patient care, our palliative care department also prioritizes “tangible” impacts to better establish our contributions to the health system. We have done this through participation on hospital committees, hospital policy revision teams, and by developing innovative solutions such as a terminal extubation protocol and order set for our ICU. The health system and its administration have recognized the importance of educating nursing and physician staff on palliative care services, and have supported these continued efforts alongside our clinical obligations.

Concurrent with administration buy-in, financial supports for our palliative care services were initially supplemented by the health system. Our department understands the importance of recognizing limitations of resources in communities and their hospitals. In efforts to minimize the department’s impact on our own health system’s financial resources, we have strived to offset our costs. We helped the hospital system meet pay-for-performance palliative care metrics set by the large local insurers resulting in financial hospital reimbursement valued at $600,000 in 2016.

The question of how the program may translate into other communities raises a major limitation: the homogeneity our population. The community surrounding the hospital is primarily Caucasian, with minimal representation of minority populations. While the patient population seen by our palliative care team is reflective of our surrounding county, it does not represent Medicare FFS beneficiaries on a national level or many other types of community hospitals across the country. Variations of ethnicity, age, diagnoses, and faith are fundamental, which highlights the importance of understanding the community in which a program is developed.

The rising trajectory of our palliative care service utilization has prompted a discussion of future endeavors for our program. Expectations for a continued shortage of hospice and palliative care physicians [19] and concerns for practitioner burnout [20] underlie our thoughtful approach to expansion of inpatient and outpatient services. At this time, potential projects include a consultation trigger system and incorporation of palliative care providers in ICU rounding, as well as possible expansion of outpatient services through implantation of an advanced practitioner into surrounding nursing homes and primary care offices.

We have found a growing utilization of our program at Butler Health System. Our first year experience has highlighted the importance of identifying community and hospital administrative champions as a foundation. Additionally, understanding the specific characteristics of one’s surrounding community may allow for improved integration and acceptance of palliative care in a community setting. Our program continues to work with the health system, community, and philanthropic organizations to expand the ever-growing need for palliative care services.

From the Division of Palliative Care, Butler Health System, Butler, PA (Drs. Stein, Reefer, Selvaggi, Ms. Doverspike); the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Rajagopal); and the Duke Cancer Institute and Duke Fuqua School of Business, Durham, NC (Dr. Kamal).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe an approach to develop a community-centric palliative care program in a rural community health system and to review data collected over the program’s first year.

- Methods: We describe the underlying foundations of our program development including the health system’s prioritization of a palliative care program, funding opportunities, collaboration with community supports, and the importance of building a team and program that reflects a community’s needs. Data were collected through a program-maintained spreadsheet and a data monitoring system available through the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance.

- Results: 516 new inpatient consultations were seen during the first year, for a penetration of 3.7%. The demographics of the patients who received consultation reflect that of the surrounding community. Over 50% of patients seen within the first year died, and hospice utilization at home and within facilities and inpatient hospice units increased. In addition, 79% of the patients seen by the palliative care team had a confirmed code status of do not resuscitate and do not intubate.

- Conclusions: Butler Health System’s approach to development of a palliative care program has resulted in increasing utilization of palliative care services in the hospital. Having hospital administration support, community support, and understanding the individualized needs of a community has been essential for the program’s expansion.

Key words: palliative care; program development; community hospital; rural.

Since its inception, palliative care has been committed to providing specialty-level consultation services to individuals with serious illness and their loved ones. The field has focused heavily on growth and acceptance, consistently moving upstream with regards to illness trajectory, across diseases, and across demographic variables such as age (eg, pediatric quality of life programs) and race (eg, community outreach programs addressing racial disparities in hospice use). An important frontier that remains challenging for much of the field is expansion into the community setting, where resources, implicit acceptance, and patient populations may vary.

As health system leaders appreciate the positive impacts palliative medicine on patient care and care quality, barriers to implementing palliative care programs in community hospitals must be addressed in ways tailored to the unique needs of smaller organizations and their communities. The goal of this paper is to outline the approach taken to develop Butler Health System’s community-centric palliative care program, describe our program’s underlying foundation rooted in community supports, and recount steps we have taken thus far to impact patient care in our hospital, health system, and community through the program’s first year.

Community Hospital Palliative Care—The Necessity and the Challenges

Palliative care has made strides in its growth and acceptance in the last decade; yet, the distribution of that growth has been skewed. Although 67% of hospitals now report access to specialist palliative care programs, most of the 148% growth over the last decade has been actualized in larger hospitals. Ninety percent of hospitals with greater than 300 beds report palliative care service availability whereas only 56% of small hospitals were identified to have this specialty care [1].

The inequity of access is also seen in other countries. A recent Canadian study retrospectively examined access to care of 23,860 deceased patients in Nova Scotia. Although they found 40.9% of study subjects were enrolled in a palliative care program at urban, academic centers, patients in a rural setting were only a third as likely to be enrolled in a palliative care program [2]. This access gap has important effects on patient-level outcomes, as evidence has consistently demonstrated that patients in rural settings who receive palliative care have decreased unnecessary hospitalizations and less in-hospital deaths [3].

While evidence of improved outcomes is strong, important barriers stand in the way. In a 2013 study, 374 health care providers at 236 rural hospitals in 7 states were interviewed to determine barriers to providing palliative care in rural settings. Barriers identified include a lack of administrative support, access to basic palliative care training for primary care physicians, and limited relationships to hospices [4]. Additional challenges include lack of access to tertiary-level specialty clinicians, access to and misconceptions about prescription medications, transportation for patients and providers, and incorporating a patient’s community supports [5–7].

Proposed Solutions

Techniques to improve palliative care access for rural and community centers that have been previously reviewed in the literature include videoconferencing with tertiary care experts in palliative care and education through small community-level lectures [8–10]. Goals of rural and suburban palliative care programs are broadly similar to programs at academic medical centers; however, few studies have identified impact of palliative medicine on patient care in community settings. In one suburban practice, a study found that patients were more likely to die at home if they had multiple caregivers, increased length of time under palliative care, and older age upon referral [11].

The United States has few large-scale pilot programs attempting to address the palliative needs of a more suburban or rural population. Of these, the Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative developed by Stratis Health is perhaps the best publicized. Stratis Health developed and led an 18-month learning collaborative from October 2008 to April 2010 through which community teams developed or improved palliative care services. Through this initiative, a community-based health care practice model was developed that took advantage of the strong interrelationships within rural communities. After 18 months, 6 out of 10 rural Minnesota communities had formal palliative care programs, and 8 to 9 out of 10 had capabilities to at least address advance directives as well as provider and community education [12]. In another initiative, the NIH established a new suburban clinic with tertiary providers specifically for resource intensive, underserved patients [13]. The clinic was established by partnering with a service that was already in place in the community. Twenty-seven patients were seen within 7 months. The most common consults were patients with numerous comorbidities and chronic pain rather than terminal diagnoses. Given the intensive need of these patients, the authors felt that a consultation service and an interdisciplinary team that included psychosocial/spiritual/social work providers offered the most efficient method of delivering advanced palliative care needs.

The research regarding both solutions to challenges and novel methods of addressing the care gap remains sparse as evidenced by the conclusions of multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses and the inability of the Cochrane review to find papers meeting inclusion criteria regarding techniques of community support in palliative care [14,15]. There remains a need to identify practical techniques of implementing palliative care in rural and suburban settings.

The Butler Health System Experience

In August 2015, we set out to start the first hospital-based palliative care consultation service in the Butler Health System. The health system is a nonprofit, single-hospital system anchored by Butler Memorial Hospital, a 294-bed community hospital located within a rural Pennsylvania county of 186,000 residents, 35 miles north of Pittsburgh. Butler County consists of a predominantly white, non-Hispanic population with over 15% of the residents being older than 65 years of age. The median household income is $61,000 earned primarily through blue collar occupations [16]. Driven by 53 employed primary care physicians, the health system provides services for 75,000 patients at sites covering an area of 4000 square miles. The hospital provides general medical, critical, surgical and subspecialty care and behavior health services as a regional referral center for 4 surrounding rural counties, accepting 12,500 inpatient admissions annually. A hospitalist service admits the majority of oncology patients, and the intensive care unit (ICU) is an open unit, where patients are admitted to the hospitalist, primary care, or surgical service.

While no formal needs assessment was performed prior to program development, perceptions of inadequate pain control, overuse of naloxone, underutilization of hospice services, and lack of consistent quality in end-of-life care were identified. These concerns were voiced at the levels of direct patient care on the floors, and by nursing and physician hospital leadership. Prior to our program, the chief medical officer attended the national Center to Advance Palliative Care conference to better understand the field of palliative care and its impact on improving quality of care. Concurrently, our health system was expanding its inpatient capabilities (eg, advanced neurologic and cardiac services), resulting in admissions with increased disease severity and illness complexity. With the vision of improved patient care, prioritizing quality end-of-life care and symptom management, the hospital board and administration overwhelmingly supported the development of the palliative care program, philosophically and financially.

Laying a Foundation—Funding, Collaboration, and Team Building

Funding and staffing are 2 important factors when building any program. Sources of funding for palliative care programs may include hospital support, billing revenue, grants, and philanthropy. Program development was a priority for the hospital and community. To help offset costs, efforts to raise financial support focused on utilizing the health system’s annual fundraising events. Through the generosity of individuals in the community, the hospital’s annual gala event, and donations from the hospital’s auxiliary, a total of $230,000 was raised prior to program initiation. Funds budgeted through direct hospital support and fundraising were allocated towards hiring palliative care team members and community marketing projects.

The hospital’s surrounding community is fortunate to have 2 local inpatient hospice facilities, and these relationships were imperative to providing quality end-of-life care preceding our palliative care program. A formal partnership was previously established with one while the other remains an important referral facility due to its proximity to the hospital. These hospice services are encouraged to participate in our weekly palliative care interdisciplinary team meetings. Their incorporation has improved coordination, continuity, and translation of care upon patient discharge from the acute hospital setting. Additionally, the relationships have been beneficial in tracking patients’ outcomes and data collection.

The standard structure of a palliative care team described by the Joint Commission and National Consensus Panel for Palliative Care consists of a physician, registered nurse or advanced practice provider, chaplaincy, and social work. Despite this recommendation, less than 40% of surveyed hospitals met the criteria, and less than 25% have dedicated funding to cover these positions [17]. Upon inception of our palliative care program, 2.6 funded full-time equivalents (FTEs) were allocated. These positions included a physician (1.0 FTE), a physician assistant (1.0 FTE), and a part time palliative care social worker (0.6 FTE). The 2015 National Palliative Care Registry found that 3.2 funded FTEs per 10,000 admissions is the average for hospitals with 150 to 299 beds [17]. The uncertainty of the utilization and consult volume, and the limited amount of qualified palliative care trained practitioners, resulted in the palliative program starting below this mean at 2.1 funded FTEs per 10,000 admissions. All the funded positions were located on site at the hospital. The pre-existing volunteer hospital chaplain service was identified as the pastoral care component for the program.

Increased FTEs have been associated with increased palliative care service penetration and ultimately in decreased time to consult [18]. In response to increasing consult volumes, concerns for delays in time to consult, and in preparation for expansion to an outpatient service, the palliative care department acquired an additional funded physician FTE (1.0). Ultimately the service reached a total of 3.6 FTE for inpatient services during its first 12 months; proportionately this resulted in an increase to 2.9 FTE per 10,000 admissions based on the yearly admission rate of 12,500 patients.

Educational Outreach

The success of a palliative care program depends on other clinicians’ acceptance and referral to the clinical program. We took a 2-pronged approach, focusing on both hospital-based and community-based education. The hospital-based nursing education included 30-minute presentations on general overviews of palliative care, differences between palliative care and hospice, and acute symptom management at the end of life. The palliative care team presented to all medical, surgical, and intensive care units and encompassed all shifts of nursing staff. These lectures included pre- and post-tests to assess for impact and feedback. Similar educational presentations, as well as an hour-long presentation on opioids and palliative care, were available for physicians for CME opportunities. We also distributed concise palliative care referral packets to outpatient primary care offices through the health system’s marketing team. The referral packets included examples of diagnoses, clinical scenarios, and symptoms to assist in the physicians’ understanding of palliative care services. The palliative care team also met with clinic office managers to discuss the program and answer questions.

There were also educational opportunities for patients and families in our community. Taking advantage of previously developed partnerships between the hospital system and local media outlets, the palliative care team performed local radio spots to educate the community on topics including an overview of palliative care, how to request palliative care, and the difference between palliative care and hospice care. We partnered with a local hospice agency and developed a well-received bereavement seminar for patients, family members, and employees and included the topic of advanced care planning.

Data Collection

We collect data using 2 different tools: a self-maintained spreadsheet shared between our palliative care clinicians, and a collective data tool (QDACT) included in our membership with and maintained by the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance. Data collected and tracked in our spreadsheet includes date of consult, patient age, primary and secondary diagnoses, disposition, goals of care discussions, date of death, and 30-day readmissions. Through the QDACT data monitoring program, we are tracking and analyzing quality measures including symptom assessment and management and code status conversion. The QDACT database also provides financial data specific to our institution such as cost savings based on our billing, readmission rates, and length of stay.

Results

Projections, Volumes, and Penetration

Prior to the start of our program, our chief medical office used Center to Advance Palliative Care tools to project inpatient consultation volumes at our institution. Variables that are recommended by this center to guide projections include number of hospital admissions per year, hospital occupancy, disposition to hospice, as well as generalized estimations of inpatient mortality rates. Based on our data, it was expected that our program would receive 204 new inpatient consults in our first year, and 774 follow-up visits. Our actual new inpatient consults totaled 516, with 919 follow-up visits. Palliative care penetration (percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by the palliative care team) our first year was 3.7% (Table 1).

Consultation Demographics

The demographics of the patients seen by the palliative care team reflect that of Butler County’s Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) population (Table 2); however, differences were seen at the state and national level with regard to ethnicity (Table 2).

Almost half of consultations (49%) were placed by the hospitalist service. Since the ICU is an open unit, critical care consults are not adequately reflected by analysis of the ordering physician alone. Analysis of consultation location revealed that 27% of inpatient consults were located within the ICU.

Patient Outcomes and Disposition

Outcomes and discharge data from the first year were collected and reviewed. Ten percent of the patients seen by palliative care died in the hospital, and 51% of patients that were seen by palliative care died within the program’s first year. Thirty-seven percent of patients discharged from the hospital utilized hospice services at home, in residential nursing facility, or at an inpatient hospice unit. The remaining 53% were discharged without hospice services to home or facility (Figure).

Hospice utilization by the health system increased during our first year. Compared to the 2014 calendar year, there were a total of 263 referrals for hospice services. During the first year of the palliative care program, which started August 2015, there were a total of 293 referrals. Of the 293 total hospice referrals, 190 (64.8%) of these referrals were for patients seen by the palliative care team.

Change of Code Status

Code status and changes in codes status data were collected. Of 462 individual patients prior to or at the time of palliative care consults, 43% were full code, 4% limited code, 8% unknown status, and 45% Do Not Resuscitate. After palliative care consult, 61% of the patients who were previously full/limited/unknown converted to do not resuscitate and do not intubate status. In total, 79% of patients seen by palliative care had a confirmed code status of Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Intubate status after consult.

Discussion

In our first year, our palliative care program exceeded the expected number of inpatient consults, corresponding with a penetration of 3.7%. With the increase of funded FTEs, preliminary data shows that the department’s penetration continues to rise remaining consistent with the data and expectations [18]. During the second year, it is anticipated that over 600 inpatient palliative care consultations will be performed with an estimated penetration of 4%. This increasing penetration reflects the rising utilization of palliative care within our hospital. Since inception of the program, the service has expanded into an outpatient clinic 2 days per week. The palliative care clinic is staffed by a registered nurse (funded 0.6 FTE) and covered by the same physicians and physician assistant providing the inpatient services. The department acquired an unfunded but designated chaplaincy volunteer to assist with patients’ spiritual needs. We believe that the success of our program during the first year was related to multiple factors: a focus of integration and education by the palliative care department, health system administration buy-in, and identification of surrounding community needs.

In addition to patient care, our palliative care department also prioritizes “tangible” impacts to better establish our contributions to the health system. We have done this through participation on hospital committees, hospital policy revision teams, and by developing innovative solutions such as a terminal extubation protocol and order set for our ICU. The health system and its administration have recognized the importance of educating nursing and physician staff on palliative care services, and have supported these continued efforts alongside our clinical obligations.

Concurrent with administration buy-in, financial supports for our palliative care services were initially supplemented by the health system. Our department understands the importance of recognizing limitations of resources in communities and their hospitals. In efforts to minimize the department’s impact on our own health system’s financial resources, we have strived to offset our costs. We helped the hospital system meet pay-for-performance palliative care metrics set by the large local insurers resulting in financial hospital reimbursement valued at $600,000 in 2016.

The question of how the program may translate into other communities raises a major limitation: the homogeneity our population. The community surrounding the hospital is primarily Caucasian, with minimal representation of minority populations. While the patient population seen by our palliative care team is reflective of our surrounding county, it does not represent Medicare FFS beneficiaries on a national level or many other types of community hospitals across the country. Variations of ethnicity, age, diagnoses, and faith are fundamental, which highlights the importance of understanding the community in which a program is developed.

The rising trajectory of our palliative care service utilization has prompted a discussion of future endeavors for our program. Expectations for a continued shortage of hospice and palliative care physicians [19] and concerns for practitioner burnout [20] underlie our thoughtful approach to expansion of inpatient and outpatient services. At this time, potential projects include a consultation trigger system and incorporation of palliative care providers in ICU rounding, as well as possible expansion of outpatient services through implantation of an advanced practitioner into surrounding nursing homes and primary care offices.

We have found a growing utilization of our program at Butler Health System. Our first year experience has highlighted the importance of identifying community and hospital administrative champions as a foundation. Additionally, understanding the specific characteristics of one’s surrounding community may allow for improved integration and acceptance of palliative care in a community setting. Our program continues to work with the health system, community, and philanthropic organizations to expand the ever-growing need for palliative care services.

1. Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, et al. The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med 2016;19:8–15.

2. Lavergne MR, Lethbridge L, Johnston G, et al. Examining palliative care program use and place of death in rural and urban contexts: a Canadian population-based study using linked data. Rural Remote Health 2015;15:3134.

3. Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g3496.

4. Fink RM, Oman KS, Youngwerth J, et al. A palliative care needs assessment of rural hospitals. J Palliat Med 2013;16:638–44.

5. Dumont S, Jacobs P, Turcotte V, et al. Palliative care costs in Canada: A descriptive comparison of studies of urban and rural patients near end of life. J Palliat Med 2015;29:908–17.

6. Kaasalainen S, Brazil K, Williams A, et al. Nurses' experiences providing palliative care to individuals living in rural communities: aspects of the physical residential setting. Rural Remote Health 2014;14:2728.

7. Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. J Palliat Med 2004;18:525–42.

8. Ray RA, Fried O, Lindsay D. Palliative care professional education via video conference builds confidence to deliver palliative care in rural and remote locations. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:272.

9. Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, et al. Systematic review of palliative care in the rural setting. Cancer Control 2015;22:450–64.

10. Akiyama M, Hirai K, Takebayashi T, et al. The effects of community-wide dissemination of information on perceptions of palliative care, knowledge about opioids, and sense of security among cancer patients, their families, and the general public. Support Care Cancer 2016;24: 347–56.

11. Maida V. Factors that promote success in home palliative care: a study of a large suburban palliative care practice. J Palliat Care 2002;18:282–6.

12. Ceronsky L, Shearer J, Weng K, et al. Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative: building palliative care capacity in rural Minnesota. J Palliat Med 2013;16:310–3.

13. Aggarwal SK, Ghosh A, Cheng MJ, et al. Initiating pain and palliative care outpatient services for the suburban underserved in Montgomery County, Maryland: Lessons learned at the NIH Clinical Center and MobileMed. Palliat Support Care 2015;16:1–6.

14. Rainsford S, MacLeod RD, Glasgow NJ. Place of death in rural palliative care: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 2016;30:745–63.

15. Horey D, Street AF, O'Connor M, et al. Training and supportive programs for palliative care volunteers in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 Jul 20;(7):CD009500.

16. The United States Census Bureau: QuickFacts: Butler County, Pennsylvania. Accessed 10 Mar 2017 at www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/42019,00.

17. Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, et al. Few hospital palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff 2016;35:1690–7.

18. Dumanovsky T, Rogers M, Spragens LH, et al. Impact of Staffing on Access to Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2015 Dec; 18(12). Pages 998-999.

19. Lupu D, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899–911.

20. Kamal AH, Bull JK, Wolf SP, et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:690–6.

1. Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, et al. The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med 2016;19:8–15.

2. Lavergne MR, Lethbridge L, Johnston G, et al. Examining palliative care program use and place of death in rural and urban contexts: a Canadian population-based study using linked data. Rural Remote Health 2015;15:3134.

3. Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g3496.

4. Fink RM, Oman KS, Youngwerth J, et al. A palliative care needs assessment of rural hospitals. J Palliat Med 2013;16:638–44.

5. Dumont S, Jacobs P, Turcotte V, et al. Palliative care costs in Canada: A descriptive comparison of studies of urban and rural patients near end of life. J Palliat Med 2015;29:908–17.

6. Kaasalainen S, Brazil K, Williams A, et al. Nurses' experiences providing palliative care to individuals living in rural communities: aspects of the physical residential setting. Rural Remote Health 2014;14:2728.

7. Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. J Palliat Med 2004;18:525–42.

8. Ray RA, Fried O, Lindsay D. Palliative care professional education via video conference builds confidence to deliver palliative care in rural and remote locations. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:272.

9. Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, et al. Systematic review of palliative care in the rural setting. Cancer Control 2015;22:450–64.

10. Akiyama M, Hirai K, Takebayashi T, et al. The effects of community-wide dissemination of information on perceptions of palliative care, knowledge about opioids, and sense of security among cancer patients, their families, and the general public. Support Care Cancer 2016;24: 347–56.

11. Maida V. Factors that promote success in home palliative care: a study of a large suburban palliative care practice. J Palliat Care 2002;18:282–6.

12. Ceronsky L, Shearer J, Weng K, et al. Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative: building palliative care capacity in rural Minnesota. J Palliat Med 2013;16:310–3.

13. Aggarwal SK, Ghosh A, Cheng MJ, et al. Initiating pain and palliative care outpatient services for the suburban underserved in Montgomery County, Maryland: Lessons learned at the NIH Clinical Center and MobileMed. Palliat Support Care 2015;16:1–6.

14. Rainsford S, MacLeod RD, Glasgow NJ. Place of death in rural palliative care: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 2016;30:745–63.

15. Horey D, Street AF, O'Connor M, et al. Training and supportive programs for palliative care volunteers in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 Jul 20;(7):CD009500.

16. The United States Census Bureau: QuickFacts: Butler County, Pennsylvania. Accessed 10 Mar 2017 at www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/42019,00.