User login

Review: Opioid prescriptions are the work of many physicians

A “broad swath” of Medicare providers wrote scripts for opioids in 2013, contradicting the idea that the overdose epidemic is mainly the work of “small groups of prolific prescribers and corrupt pill mills,” investigators wrote online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Contrary to the California workers’ compensation data showing a small subset of prescribers accounting for a disproportionately large percentage of opioid prescribing, Medicare opioid prescribing is distributed across many prescribers and is, if anything, less skewed than all drug prescribing,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System, and his associates.

Their study included 808,020 prescribers and almost 1.2 billion Medicare Part D claims worth nearly $81 billion dollars. They focused on schedule II opioid prescriptions containing oxycodone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, meperidine, codeine, opium, or levorphanol (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Dec 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662).

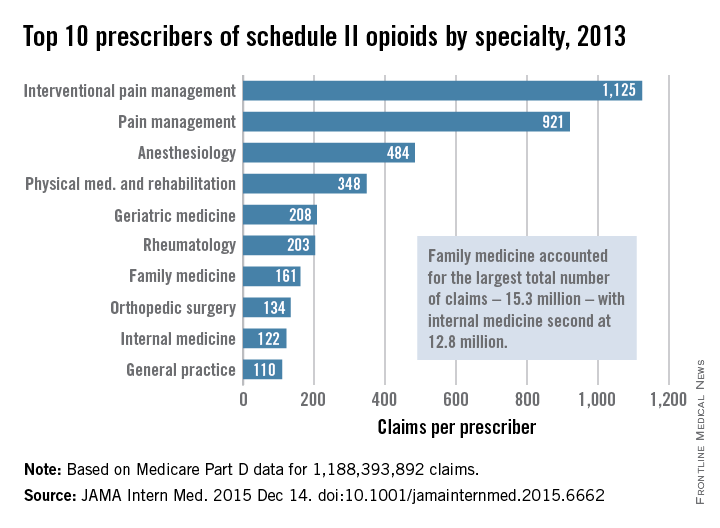

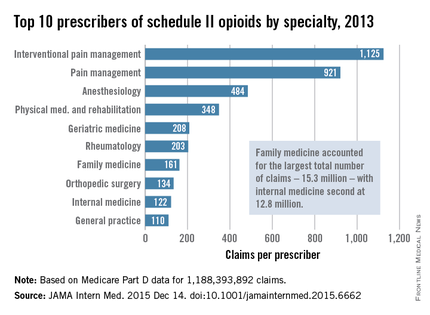

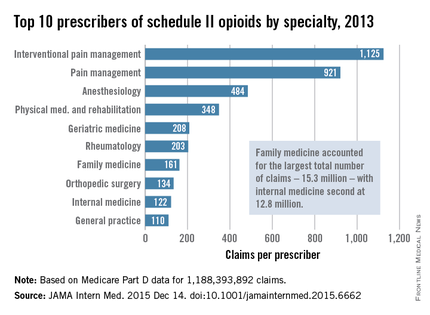

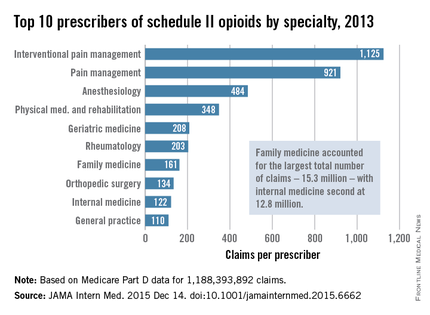

Not surprisingly, specialists in pain management, anesthesia, and physical medicine wrote the most prescriptions per provider. But family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined. “The trends hold up across state lines, with negligible geographic variability,” the researchers said.

The findings contradict an analysis of California workers’ compensation data, in which 1% of prescribers accounted for a third of schedule II opioid prescriptions, and 10% of prescribers accounted for 80% of prescriptions, the investigators noted. Nonetheless, 10% of Medicare prescribers in Dr. Chen’s study accounted for 78% of the total cost of opioids, possibly because they were prescribing pricier formulations or higher doses.

Overall, the findings suggest that opioid prescribing is “widespread” and “relatively indifferent to individual physicians, specialty, or region” – and that efforts to stem the tide must be equally broad, the researchers concluded.

Their study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

A “broad swath” of Medicare providers wrote scripts for opioids in 2013, contradicting the idea that the overdose epidemic is mainly the work of “small groups of prolific prescribers and corrupt pill mills,” investigators wrote online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Contrary to the California workers’ compensation data showing a small subset of prescribers accounting for a disproportionately large percentage of opioid prescribing, Medicare opioid prescribing is distributed across many prescribers and is, if anything, less skewed than all drug prescribing,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System, and his associates.

Their study included 808,020 prescribers and almost 1.2 billion Medicare Part D claims worth nearly $81 billion dollars. They focused on schedule II opioid prescriptions containing oxycodone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, meperidine, codeine, opium, or levorphanol (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Dec 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662).

Not surprisingly, specialists in pain management, anesthesia, and physical medicine wrote the most prescriptions per provider. But family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined. “The trends hold up across state lines, with negligible geographic variability,” the researchers said.

The findings contradict an analysis of California workers’ compensation data, in which 1% of prescribers accounted for a third of schedule II opioid prescriptions, and 10% of prescribers accounted for 80% of prescriptions, the investigators noted. Nonetheless, 10% of Medicare prescribers in Dr. Chen’s study accounted for 78% of the total cost of opioids, possibly because they were prescribing pricier formulations or higher doses.

Overall, the findings suggest that opioid prescribing is “widespread” and “relatively indifferent to individual physicians, specialty, or region” – and that efforts to stem the tide must be equally broad, the researchers concluded.

Their study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

A “broad swath” of Medicare providers wrote scripts for opioids in 2013, contradicting the idea that the overdose epidemic is mainly the work of “small groups of prolific prescribers and corrupt pill mills,” investigators wrote online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Contrary to the California workers’ compensation data showing a small subset of prescribers accounting for a disproportionately large percentage of opioid prescribing, Medicare opioid prescribing is distributed across many prescribers and is, if anything, less skewed than all drug prescribing,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System, and his associates.

Their study included 808,020 prescribers and almost 1.2 billion Medicare Part D claims worth nearly $81 billion dollars. They focused on schedule II opioid prescriptions containing oxycodone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, meperidine, codeine, opium, or levorphanol (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Dec 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662).

Not surprisingly, specialists in pain management, anesthesia, and physical medicine wrote the most prescriptions per provider. But family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined. “The trends hold up across state lines, with negligible geographic variability,” the researchers said.

The findings contradict an analysis of California workers’ compensation data, in which 1% of prescribers accounted for a third of schedule II opioid prescriptions, and 10% of prescribers accounted for 80% of prescriptions, the investigators noted. Nonetheless, 10% of Medicare prescribers in Dr. Chen’s study accounted for 78% of the total cost of opioids, possibly because they were prescribing pricier formulations or higher doses.

Overall, the findings suggest that opioid prescribing is “widespread” and “relatively indifferent to individual physicians, specialty, or region” – and that efforts to stem the tide must be equally broad, the researchers concluded.

Their study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Many different types of general practitioners and specialists often prescribe opioids to Medicare beneficiaries.

Major finding: Family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined.

Data source: An analysis of nearly 1.2 billion Medicare part D claims from 2013.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

Putting the Focus on Quality of Life in Cancer Care

Patient-centered care increasingly means focusing on quality of life. For the past 26 years, Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, director and professor, nursing research and education at City of Hope has focused on quality of life research.

Dr. Ferrell recently sat down Federal Practitioner to discuss the components of quality cancer care, the role of family caregivers, and the importance of patient communication.

According to Dr. Ferrell, quality cancer care starts a comprehensive assessment so that care providers understand not only comorbidities, but also family help and psychosocial concerns. Interdisciplinary collaboration is also an essential element of quality care, bringing together an entire team to focus on the patient. Finally, Dr. Ferrell noted, care must include patient and family education.

0:15 Quality of life research

1:35 Quality of life interventions

2:52 Family care givers

3:30 Three components of quality cancer care

4:38 Communication

5:20 VA cancer care

Patient-centered care increasingly means focusing on quality of life. For the past 26 years, Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, director and professor, nursing research and education at City of Hope has focused on quality of life research.

Dr. Ferrell recently sat down Federal Practitioner to discuss the components of quality cancer care, the role of family caregivers, and the importance of patient communication.

According to Dr. Ferrell, quality cancer care starts a comprehensive assessment so that care providers understand not only comorbidities, but also family help and psychosocial concerns. Interdisciplinary collaboration is also an essential element of quality care, bringing together an entire team to focus on the patient. Finally, Dr. Ferrell noted, care must include patient and family education.

0:15 Quality of life research

1:35 Quality of life interventions

2:52 Family care givers

3:30 Three components of quality cancer care

4:38 Communication

5:20 VA cancer care

Patient-centered care increasingly means focusing on quality of life. For the past 26 years, Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, director and professor, nursing research and education at City of Hope has focused on quality of life research.

Dr. Ferrell recently sat down Federal Practitioner to discuss the components of quality cancer care, the role of family caregivers, and the importance of patient communication.

According to Dr. Ferrell, quality cancer care starts a comprehensive assessment so that care providers understand not only comorbidities, but also family help and psychosocial concerns. Interdisciplinary collaboration is also an essential element of quality care, bringing together an entire team to focus on the patient. Finally, Dr. Ferrell noted, care must include patient and family education.

0:15 Quality of life research

1:35 Quality of life interventions

2:52 Family care givers

3:30 Three components of quality cancer care

4:38 Communication

5:20 VA cancer care

Myth of the Month: Does Colace work?

Myth: Docusate is a stool softener and helps with constipation.

A 60-year-old man is injured in a fall and breaks four ribs. He is in severe pain and is prescribed oxycodone and naproxen for pain. What treatment would you prescribe to help decrease problems with constipation?

A. Docusate.

B. Docusate and polyethylene glycol.

C. Psyllium.

D. Polyethylene glycol.

Constipation is extremely common, occurring in up to 20%-25% of the elderly population and 90% of patients treated with opioids. The formal definition of constipation is fewer than three bowel movements per week. Patients are concerned with other symptoms as well, including hard stool consistency and the feeling of incomplete evacuation.

An extremely commonly prescribed medication for patients with symptoms of constipation/hard stool passage is docusate (Colace). This medication is often a part of bowel programs for institutionalized/hospitalized patients, as well as being frequently prescribed when patients are treated with opiates.

Does it work?

Docusate is frequently prescribed as a “stool softener,” but does it increase water content in stool? In a randomized, controlled trial of docusate vs. psyllium, 170 adult patients with chronic constipation received either 5.1 g twice a day of psyllium or 100 mg twice a day of docusate (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998 May;12[5]:491-7).

Psyllium was superior in its effect on stool frequency, stool water content, total stool output, and the combination of several objective measures of constipation. Compared with baseline, psyllium increased stool water content by 2.33%, vs .01% for docusate (P =. 007), and stool weight was increased in the group treated with psyllium, compared with docusate-treated patients (359.9 g/week vs. 271.9 g/week, respectively; P = .005). Docusate does not appear to have any effect on stool water content or amount of stool.

In a study of constipation treatment in patients receiving opioids, Dr. Yoko Tarumi and her colleagues studied 74 patients admitted to hospice units (J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013 Jan;45[1]:2-13). A total of 74 patients were randomized to receive docusate 100 mg twice a day plus senna, or placebo plus senna. Once the study was started, inclusion criteria were broadened to include hospice patients with nonmalignant disease and patients who were not on opioids.

Almost all patients in the study did receive opioids (94% of the docusate patients and 100% of placebo-treated patients). There were no significant between the groups in stool volume, frequency, consistency, or in perceived completeness of evacuation.

In a randomized, controlled study of elderly patients on a medicine ward, 34 patients were randomized to docusate or control (no laxatives)(J Chronic Dis. 1976 Jan;29[1]:59-63). There was no difference in frequency or quality of stools between groups.

A systematic review of the usefulness of docusate in chronically ill patients concluded that the widespread use of docusate for the treatment of constipation in palliative-care patients is based on inadequate experimental evidence (J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Feb;19[2]:130-6).

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health concluded “the available evidence suggests that docusate is no more effective than placebo in the prevention or management of constipation” (Dioctyl sulfosuccinate or docusate [calcium or sodium] for the prevention or management of constipation: a review of the clinical effectiveness. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014 Jun 26).

Dr. Davendra Ramkumar and his colleagues published a systematic review of drug trials for the treatment of constipation in 2005 (Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Apr;100[4]:936-71). Only polyethylene glycol and tegaserod received grade A evidence for published trials. Psyllium and lactulose received grade B evidence. Docusate received a level 3, grade C for evidence (poor quality evidence, poor evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of the modality).

I have been surprised at how docusate has been the most commonly prescribed laxative agent. Polyethylene glycol or psyllium are better evidence-based options. Docusate is often prescribed as a stool softener, and it has even less evidence that it softens stool than its poor evidence as a laxative.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the late Dr. David Saunders for teaching me 30 years ago that docusate was not a helpful option for the management of constipation, and to Sarah Steinkruger for doing much of the research that was used in this column.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Myth: Docusate is a stool softener and helps with constipation.

A 60-year-old man is injured in a fall and breaks four ribs. He is in severe pain and is prescribed oxycodone and naproxen for pain. What treatment would you prescribe to help decrease problems with constipation?

A. Docusate.

B. Docusate and polyethylene glycol.

C. Psyllium.

D. Polyethylene glycol.

Constipation is extremely common, occurring in up to 20%-25% of the elderly population and 90% of patients treated with opioids. The formal definition of constipation is fewer than three bowel movements per week. Patients are concerned with other symptoms as well, including hard stool consistency and the feeling of incomplete evacuation.

An extremely commonly prescribed medication for patients with symptoms of constipation/hard stool passage is docusate (Colace). This medication is often a part of bowel programs for institutionalized/hospitalized patients, as well as being frequently prescribed when patients are treated with opiates.

Does it work?

Docusate is frequently prescribed as a “stool softener,” but does it increase water content in stool? In a randomized, controlled trial of docusate vs. psyllium, 170 adult patients with chronic constipation received either 5.1 g twice a day of psyllium or 100 mg twice a day of docusate (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998 May;12[5]:491-7).

Psyllium was superior in its effect on stool frequency, stool water content, total stool output, and the combination of several objective measures of constipation. Compared with baseline, psyllium increased stool water content by 2.33%, vs .01% for docusate (P =. 007), and stool weight was increased in the group treated with psyllium, compared with docusate-treated patients (359.9 g/week vs. 271.9 g/week, respectively; P = .005). Docusate does not appear to have any effect on stool water content or amount of stool.

In a study of constipation treatment in patients receiving opioids, Dr. Yoko Tarumi and her colleagues studied 74 patients admitted to hospice units (J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013 Jan;45[1]:2-13). A total of 74 patients were randomized to receive docusate 100 mg twice a day plus senna, or placebo plus senna. Once the study was started, inclusion criteria were broadened to include hospice patients with nonmalignant disease and patients who were not on opioids.

Almost all patients in the study did receive opioids (94% of the docusate patients and 100% of placebo-treated patients). There were no significant between the groups in stool volume, frequency, consistency, or in perceived completeness of evacuation.

In a randomized, controlled study of elderly patients on a medicine ward, 34 patients were randomized to docusate or control (no laxatives)(J Chronic Dis. 1976 Jan;29[1]:59-63). There was no difference in frequency or quality of stools between groups.

A systematic review of the usefulness of docusate in chronically ill patients concluded that the widespread use of docusate for the treatment of constipation in palliative-care patients is based on inadequate experimental evidence (J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Feb;19[2]:130-6).

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health concluded “the available evidence suggests that docusate is no more effective than placebo in the prevention or management of constipation” (Dioctyl sulfosuccinate or docusate [calcium or sodium] for the prevention or management of constipation: a review of the clinical effectiveness. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014 Jun 26).

Dr. Davendra Ramkumar and his colleagues published a systematic review of drug trials for the treatment of constipation in 2005 (Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Apr;100[4]:936-71). Only polyethylene glycol and tegaserod received grade A evidence for published trials. Psyllium and lactulose received grade B evidence. Docusate received a level 3, grade C for evidence (poor quality evidence, poor evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of the modality).

I have been surprised at how docusate has been the most commonly prescribed laxative agent. Polyethylene glycol or psyllium are better evidence-based options. Docusate is often prescribed as a stool softener, and it has even less evidence that it softens stool than its poor evidence as a laxative.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the late Dr. David Saunders for teaching me 30 years ago that docusate was not a helpful option for the management of constipation, and to Sarah Steinkruger for doing much of the research that was used in this column.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Myth: Docusate is a stool softener and helps with constipation.

A 60-year-old man is injured in a fall and breaks four ribs. He is in severe pain and is prescribed oxycodone and naproxen for pain. What treatment would you prescribe to help decrease problems with constipation?

A. Docusate.

B. Docusate and polyethylene glycol.

C. Psyllium.

D. Polyethylene glycol.

Constipation is extremely common, occurring in up to 20%-25% of the elderly population and 90% of patients treated with opioids. The formal definition of constipation is fewer than three bowel movements per week. Patients are concerned with other symptoms as well, including hard stool consistency and the feeling of incomplete evacuation.

An extremely commonly prescribed medication for patients with symptoms of constipation/hard stool passage is docusate (Colace). This medication is often a part of bowel programs for institutionalized/hospitalized patients, as well as being frequently prescribed when patients are treated with opiates.

Does it work?

Docusate is frequently prescribed as a “stool softener,” but does it increase water content in stool? In a randomized, controlled trial of docusate vs. psyllium, 170 adult patients with chronic constipation received either 5.1 g twice a day of psyllium or 100 mg twice a day of docusate (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998 May;12[5]:491-7).

Psyllium was superior in its effect on stool frequency, stool water content, total stool output, and the combination of several objective measures of constipation. Compared with baseline, psyllium increased stool water content by 2.33%, vs .01% for docusate (P =. 007), and stool weight was increased in the group treated with psyllium, compared with docusate-treated patients (359.9 g/week vs. 271.9 g/week, respectively; P = .005). Docusate does not appear to have any effect on stool water content or amount of stool.

In a study of constipation treatment in patients receiving opioids, Dr. Yoko Tarumi and her colleagues studied 74 patients admitted to hospice units (J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013 Jan;45[1]:2-13). A total of 74 patients were randomized to receive docusate 100 mg twice a day plus senna, or placebo plus senna. Once the study was started, inclusion criteria were broadened to include hospice patients with nonmalignant disease and patients who were not on opioids.

Almost all patients in the study did receive opioids (94% of the docusate patients and 100% of placebo-treated patients). There were no significant between the groups in stool volume, frequency, consistency, or in perceived completeness of evacuation.

In a randomized, controlled study of elderly patients on a medicine ward, 34 patients were randomized to docusate or control (no laxatives)(J Chronic Dis. 1976 Jan;29[1]:59-63). There was no difference in frequency or quality of stools between groups.

A systematic review of the usefulness of docusate in chronically ill patients concluded that the widespread use of docusate for the treatment of constipation in palliative-care patients is based on inadequate experimental evidence (J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Feb;19[2]:130-6).

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health concluded “the available evidence suggests that docusate is no more effective than placebo in the prevention or management of constipation” (Dioctyl sulfosuccinate or docusate [calcium or sodium] for the prevention or management of constipation: a review of the clinical effectiveness. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014 Jun 26).

Dr. Davendra Ramkumar and his colleagues published a systematic review of drug trials for the treatment of constipation in 2005 (Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Apr;100[4]:936-71). Only polyethylene glycol and tegaserod received grade A evidence for published trials. Psyllium and lactulose received grade B evidence. Docusate received a level 3, grade C for evidence (poor quality evidence, poor evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of the modality).

I have been surprised at how docusate has been the most commonly prescribed laxative agent. Polyethylene glycol or psyllium are better evidence-based options. Docusate is often prescribed as a stool softener, and it has even less evidence that it softens stool than its poor evidence as a laxative.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the late Dr. David Saunders for teaching me 30 years ago that docusate was not a helpful option for the management of constipation, and to Sarah Steinkruger for doing much of the research that was used in this column.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

PTSD in Patients With Cancer

Patients with PTSD already face difficulties, but the diagnosis of a serious illness, such as cancer, can have an effect on their symptoms in a treatment-hindering way. Matthew Cordova, PhD, a staff psychologist at the VA Northern California Martinez Outpatient Clinic, explained how PTSD can create difficulties for patients when they are diagnosed with a life-threating illness like cancer.

“Clinically what we see is that these patients are triggered to experience anxiety and avoidance specifically because of their cancer experience,” explained Dr. Cordova. Patients’ symptoms also worsen with “button pushers” such as the uncertainties of a treatment setting, diagnosis, and of people who will be around them.

Dr. Cordova also spoke about the challenge in creating trust between the patient and practitioner, which requires extra effort by the practitioner. Some best practices, he suggested, were focusing on the emotional safety of the patient, being emotionally and physically present during their time together, and creating a sense of predictability.

Another important way to make treatment transitions easier for patients is having a mental health team always present at the oncology and hematology clinics. In the video below Dr. Cordova elaborated on other best practices caregivers should be aware of when treating a patient with cancer and preexisting PTSD.

Patients with PTSD already face difficulties, but the diagnosis of a serious illness, such as cancer, can have an effect on their symptoms in a treatment-hindering way. Matthew Cordova, PhD, a staff psychologist at the VA Northern California Martinez Outpatient Clinic, explained how PTSD can create difficulties for patients when they are diagnosed with a life-threating illness like cancer.

“Clinically what we see is that these patients are triggered to experience anxiety and avoidance specifically because of their cancer experience,” explained Dr. Cordova. Patients’ symptoms also worsen with “button pushers” such as the uncertainties of a treatment setting, diagnosis, and of people who will be around them.

Dr. Cordova also spoke about the challenge in creating trust between the patient and practitioner, which requires extra effort by the practitioner. Some best practices, he suggested, were focusing on the emotional safety of the patient, being emotionally and physically present during their time together, and creating a sense of predictability.

Another important way to make treatment transitions easier for patients is having a mental health team always present at the oncology and hematology clinics. In the video below Dr. Cordova elaborated on other best practices caregivers should be aware of when treating a patient with cancer and preexisting PTSD.

Patients with PTSD already face difficulties, but the diagnosis of a serious illness, such as cancer, can have an effect on their symptoms in a treatment-hindering way. Matthew Cordova, PhD, a staff psychologist at the VA Northern California Martinez Outpatient Clinic, explained how PTSD can create difficulties for patients when they are diagnosed with a life-threating illness like cancer.

“Clinically what we see is that these patients are triggered to experience anxiety and avoidance specifically because of their cancer experience,” explained Dr. Cordova. Patients’ symptoms also worsen with “button pushers” such as the uncertainties of a treatment setting, diagnosis, and of people who will be around them.

Dr. Cordova also spoke about the challenge in creating trust between the patient and practitioner, which requires extra effort by the practitioner. Some best practices, he suggested, were focusing on the emotional safety of the patient, being emotionally and physically present during their time together, and creating a sense of predictability.

Another important way to make treatment transitions easier for patients is having a mental health team always present at the oncology and hematology clinics. In the video below Dr. Cordova elaborated on other best practices caregivers should be aware of when treating a patient with cancer and preexisting PTSD.

Million Veteran Program Sees Significant Research, Enrollment Progress

The Million Veterans Program (MVP) has reached 40% of its goal, registering more than 400,000 participants. Veterans who participate in the program donate blood for DNA extraction, which is linked to their health records. Created in 2012, MVP was expected to take 5 to 7 years to reach 1 million participants. Recently started research studies associated with MVP include cardiovascular risk factors, multisubstance use, pharmacogenomics of kidney disease, and metabolic conditions, among others.

“We are proud to see the progress being made in MVP, and we are confident the knowledge gained through this research will have a very tangible and positive impact on the health care that Veterans and all Americans receive,” said Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert A. McDonald. “We applaud our Veterans participating in the program. The selfless sacrifice they are making will allow researchers to gain valuable, important information.”

Genomic programs such as MVP received a significant boost earlier this year with the announcement of President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative. Both the Precision Medicine Initiative and MVP are part of a larger effort to better tailor treatment to individual patients based in part on their genetics. “VA is thrilled to be working closely with the White House and other federal partners on the president’s Precision Medicine Initiative,” said VA Chief Research and Development Officer Timothy O’Leary, MD, PhD. “We are committed to making precision medicine a reality for veterans and the nation."

Federal Practitioner recently spoke with Robert Nussbaum, MD, of the University of California—San Francisco on the potential impact of MVP on genomics research. Watch the video below for more on the importance of MVP and its role in genomics.

The Million Veterans Program (MVP) has reached 40% of its goal, registering more than 400,000 participants. Veterans who participate in the program donate blood for DNA extraction, which is linked to their health records. Created in 2012, MVP was expected to take 5 to 7 years to reach 1 million participants. Recently started research studies associated with MVP include cardiovascular risk factors, multisubstance use, pharmacogenomics of kidney disease, and metabolic conditions, among others.

“We are proud to see the progress being made in MVP, and we are confident the knowledge gained through this research will have a very tangible and positive impact on the health care that Veterans and all Americans receive,” said Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert A. McDonald. “We applaud our Veterans participating in the program. The selfless sacrifice they are making will allow researchers to gain valuable, important information.”

Genomic programs such as MVP received a significant boost earlier this year with the announcement of President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative. Both the Precision Medicine Initiative and MVP are part of a larger effort to better tailor treatment to individual patients based in part on their genetics. “VA is thrilled to be working closely with the White House and other federal partners on the president’s Precision Medicine Initiative,” said VA Chief Research and Development Officer Timothy O’Leary, MD, PhD. “We are committed to making precision medicine a reality for veterans and the nation."

Federal Practitioner recently spoke with Robert Nussbaum, MD, of the University of California—San Francisco on the potential impact of MVP on genomics research. Watch the video below for more on the importance of MVP and its role in genomics.

The Million Veterans Program (MVP) has reached 40% of its goal, registering more than 400,000 participants. Veterans who participate in the program donate blood for DNA extraction, which is linked to their health records. Created in 2012, MVP was expected to take 5 to 7 years to reach 1 million participants. Recently started research studies associated with MVP include cardiovascular risk factors, multisubstance use, pharmacogenomics of kidney disease, and metabolic conditions, among others.

“We are proud to see the progress being made in MVP, and we are confident the knowledge gained through this research will have a very tangible and positive impact on the health care that Veterans and all Americans receive,” said Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert A. McDonald. “We applaud our Veterans participating in the program. The selfless sacrifice they are making will allow researchers to gain valuable, important information.”

Genomic programs such as MVP received a significant boost earlier this year with the announcement of President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative. Both the Precision Medicine Initiative and MVP are part of a larger effort to better tailor treatment to individual patients based in part on their genetics. “VA is thrilled to be working closely with the White House and other federal partners on the president’s Precision Medicine Initiative,” said VA Chief Research and Development Officer Timothy O’Leary, MD, PhD. “We are committed to making precision medicine a reality for veterans and the nation."

Federal Practitioner recently spoke with Robert Nussbaum, MD, of the University of California—San Francisco on the potential impact of MVP on genomics research. Watch the video below for more on the importance of MVP and its role in genomics.

We hold the pen, but who writes the story?

Mrs. J, a physically frail but mentally sharp 75-year-old with known metastatic gastric cancer was admitted to the hospital 2 days ago with a small bowel obstruction. Despite appropriate conservative management, her symptoms are worsening. Her prior cancer treatment consisted of gastric resection with reconstruction and chemo and radiation therapy. The probability of identifying a treatable cause for her bowel obstruction during exploratory laparotomy is believed to be small.

Mr. S, a debilitated 58-year-old previously treated with primary chemotherapy and radiation for cancer at the base of his tongue, presents to your office with severe pain due to recurrent disease. The cancer is potentially resectable, but it will require an extensive resection necessitating complex free flap reconstruction in this previously irradiated field.

Is an operation indicated in either/both of these patients? The risk of causing harm with these operations may outweigh the potential benefits, so how do you decide?

Surgery residents have a lot to learn during their residency training. Not only must they gain a mastery of the pathophysiology of surgical disease, they must learn a multitude of operations while they hone their manual dexterity skills. And they must learn how to take care of a multitude of patients.

Less understood and explicitly taught is how to determine whether an operation is appropriate for this specific patient. Understanding the pathophysiology of the patient’s illness is not enough; it requires an ability to effectively communicate with the patient, to understand that person’s hopes and goals, and then honestly determine whether an operation is in fact indicated. It may sound like the antithesis of surgical training, but learning when not to operate is as important as learning when to do so.

Sometimes it’s easy. When the underlying condition is easily treatable by an operation and without it the previously healthy patient will likely die, operation is usually warranted and accepted. For the critically ill patient who will not survive transfer to the operating room and induction of anesthesia, an operation would be impossible.

As illustrated by the patients described at the beginning of this piece, the decision making can be a bit more complicated.

These are the type of patients the surgeon intuitively believes will not do well, but they are referred for an operation and what surgeons do, is ... operate. “To cut is to cure,” is the old adage, not “To cut is to care.”

These are some of the toughest decisions a surgeon can make and are the ones surgeons seem to remember. The enormous responsibility that accompanies the decision to take someone to the operating room and through a potentially difficult postoperative period can be burdensome for the surgeon and potentially fraught with suffering for all.

Understanding how to address goals of care with patients and families can make these decisions easier. Yet these communication skills are not necessarily emphasized during surgical training, and in fact, they are not the forte of many physicians in general, which has led to the growth of the specialty of palliative medicine. Palliative medicine specialists are trained experts in these communication techniques.

One of the cardinal goals of palliative medicine is to help patients and families think about and clarify their treatment goals. Asking questions about “code status” is not the same as exploring someone’s overall treatment goals. Goals can range from wanting to stay alive no matter in what condition to wanting to be kept comfortable at home surrounded by loved ones even if it means a potentially shorter lifespan. By having patients clarify their ultimate goals it may become apparent that a high-risk operation is not the best way to proceed. Perhaps aggressive pain management and arranging effective home support better meets the patient’s overall goals.

You don’t have to be a palliative medicine specialist to have these conversations with patients, but it does require specific communication skills, which can be taught.

For example, many clinicians start their patient encounters by giving a brief overview of the current situation or skip straight to discussions concerning the various treatment options. But are you sure you and your patient are really starting from the same place? You can’t assume that the patient/family truly understands the medical condition, no matter what may be implied in the medical record or the referring physician’s notes. And you can’t assume a patient wants an operation just because he or she shows up in your office.

A more effective way to start the conversation is to begin by asking patients what they understand about their conditions. This will ensure your subsequent discussion corrects any misinformation and better clarifies their understanding of the situation. Starting your encounter in this fashion is critical and can avoid misunderstandings that can lead to treatments the patients do not actually want, and mistrust should complications arise.

An elective rotation with palliative medicine providers to learn these skills can be a great addition to surgical residency training. These conversations can be some of the most meaningful patient interactions a physician can experience. Incorporating an elective rotation with a palliative medicine team into surgical residency training can add value to residency training and have long-lasting benefit for future surgeons, and ultimately, for their patients, as they venture on in their surgical careers.

Nadine B. Semer, M.D., MPH, FACS, is board certified in general surgery, plastic surgery, and palliative medicine. As a reconstructive plastic surgeon, she has worked not only in the United States, but has had the privilege of taking her skills to underserved and resource-poor areas throughout the world. She currently is practicing palliative medicine full time, and is an assistant professor at UT Southwestern Medical School, in Dallas, based at Parkland Hospital.

Mrs. J, a physically frail but mentally sharp 75-year-old with known metastatic gastric cancer was admitted to the hospital 2 days ago with a small bowel obstruction. Despite appropriate conservative management, her symptoms are worsening. Her prior cancer treatment consisted of gastric resection with reconstruction and chemo and radiation therapy. The probability of identifying a treatable cause for her bowel obstruction during exploratory laparotomy is believed to be small.

Mr. S, a debilitated 58-year-old previously treated with primary chemotherapy and radiation for cancer at the base of his tongue, presents to your office with severe pain due to recurrent disease. The cancer is potentially resectable, but it will require an extensive resection necessitating complex free flap reconstruction in this previously irradiated field.

Is an operation indicated in either/both of these patients? The risk of causing harm with these operations may outweigh the potential benefits, so how do you decide?

Surgery residents have a lot to learn during their residency training. Not only must they gain a mastery of the pathophysiology of surgical disease, they must learn a multitude of operations while they hone their manual dexterity skills. And they must learn how to take care of a multitude of patients.

Less understood and explicitly taught is how to determine whether an operation is appropriate for this specific patient. Understanding the pathophysiology of the patient’s illness is not enough; it requires an ability to effectively communicate with the patient, to understand that person’s hopes and goals, and then honestly determine whether an operation is in fact indicated. It may sound like the antithesis of surgical training, but learning when not to operate is as important as learning when to do so.

Sometimes it’s easy. When the underlying condition is easily treatable by an operation and without it the previously healthy patient will likely die, operation is usually warranted and accepted. For the critically ill patient who will not survive transfer to the operating room and induction of anesthesia, an operation would be impossible.

As illustrated by the patients described at the beginning of this piece, the decision making can be a bit more complicated.

These are the type of patients the surgeon intuitively believes will not do well, but they are referred for an operation and what surgeons do, is ... operate. “To cut is to cure,” is the old adage, not “To cut is to care.”

These are some of the toughest decisions a surgeon can make and are the ones surgeons seem to remember. The enormous responsibility that accompanies the decision to take someone to the operating room and through a potentially difficult postoperative period can be burdensome for the surgeon and potentially fraught with suffering for all.

Understanding how to address goals of care with patients and families can make these decisions easier. Yet these communication skills are not necessarily emphasized during surgical training, and in fact, they are not the forte of many physicians in general, which has led to the growth of the specialty of palliative medicine. Palliative medicine specialists are trained experts in these communication techniques.

One of the cardinal goals of palliative medicine is to help patients and families think about and clarify their treatment goals. Asking questions about “code status” is not the same as exploring someone’s overall treatment goals. Goals can range from wanting to stay alive no matter in what condition to wanting to be kept comfortable at home surrounded by loved ones even if it means a potentially shorter lifespan. By having patients clarify their ultimate goals it may become apparent that a high-risk operation is not the best way to proceed. Perhaps aggressive pain management and arranging effective home support better meets the patient’s overall goals.

You don’t have to be a palliative medicine specialist to have these conversations with patients, but it does require specific communication skills, which can be taught.

For example, many clinicians start their patient encounters by giving a brief overview of the current situation or skip straight to discussions concerning the various treatment options. But are you sure you and your patient are really starting from the same place? You can’t assume that the patient/family truly understands the medical condition, no matter what may be implied in the medical record or the referring physician’s notes. And you can’t assume a patient wants an operation just because he or she shows up in your office.

A more effective way to start the conversation is to begin by asking patients what they understand about their conditions. This will ensure your subsequent discussion corrects any misinformation and better clarifies their understanding of the situation. Starting your encounter in this fashion is critical and can avoid misunderstandings that can lead to treatments the patients do not actually want, and mistrust should complications arise.

An elective rotation with palliative medicine providers to learn these skills can be a great addition to surgical residency training. These conversations can be some of the most meaningful patient interactions a physician can experience. Incorporating an elective rotation with a palliative medicine team into surgical residency training can add value to residency training and have long-lasting benefit for future surgeons, and ultimately, for their patients, as they venture on in their surgical careers.

Nadine B. Semer, M.D., MPH, FACS, is board certified in general surgery, plastic surgery, and palliative medicine. As a reconstructive plastic surgeon, she has worked not only in the United States, but has had the privilege of taking her skills to underserved and resource-poor areas throughout the world. She currently is practicing palliative medicine full time, and is an assistant professor at UT Southwestern Medical School, in Dallas, based at Parkland Hospital.

Mrs. J, a physically frail but mentally sharp 75-year-old with known metastatic gastric cancer was admitted to the hospital 2 days ago with a small bowel obstruction. Despite appropriate conservative management, her symptoms are worsening. Her prior cancer treatment consisted of gastric resection with reconstruction and chemo and radiation therapy. The probability of identifying a treatable cause for her bowel obstruction during exploratory laparotomy is believed to be small.

Mr. S, a debilitated 58-year-old previously treated with primary chemotherapy and radiation for cancer at the base of his tongue, presents to your office with severe pain due to recurrent disease. The cancer is potentially resectable, but it will require an extensive resection necessitating complex free flap reconstruction in this previously irradiated field.

Is an operation indicated in either/both of these patients? The risk of causing harm with these operations may outweigh the potential benefits, so how do you decide?

Surgery residents have a lot to learn during their residency training. Not only must they gain a mastery of the pathophysiology of surgical disease, they must learn a multitude of operations while they hone their manual dexterity skills. And they must learn how to take care of a multitude of patients.

Less understood and explicitly taught is how to determine whether an operation is appropriate for this specific patient. Understanding the pathophysiology of the patient’s illness is not enough; it requires an ability to effectively communicate with the patient, to understand that person’s hopes and goals, and then honestly determine whether an operation is in fact indicated. It may sound like the antithesis of surgical training, but learning when not to operate is as important as learning when to do so.

Sometimes it’s easy. When the underlying condition is easily treatable by an operation and without it the previously healthy patient will likely die, operation is usually warranted and accepted. For the critically ill patient who will not survive transfer to the operating room and induction of anesthesia, an operation would be impossible.

As illustrated by the patients described at the beginning of this piece, the decision making can be a bit more complicated.

These are the type of patients the surgeon intuitively believes will not do well, but they are referred for an operation and what surgeons do, is ... operate. “To cut is to cure,” is the old adage, not “To cut is to care.”

These are some of the toughest decisions a surgeon can make and are the ones surgeons seem to remember. The enormous responsibility that accompanies the decision to take someone to the operating room and through a potentially difficult postoperative period can be burdensome for the surgeon and potentially fraught with suffering for all.

Understanding how to address goals of care with patients and families can make these decisions easier. Yet these communication skills are not necessarily emphasized during surgical training, and in fact, they are not the forte of many physicians in general, which has led to the growth of the specialty of palliative medicine. Palliative medicine specialists are trained experts in these communication techniques.

One of the cardinal goals of palliative medicine is to help patients and families think about and clarify their treatment goals. Asking questions about “code status” is not the same as exploring someone’s overall treatment goals. Goals can range from wanting to stay alive no matter in what condition to wanting to be kept comfortable at home surrounded by loved ones even if it means a potentially shorter lifespan. By having patients clarify their ultimate goals it may become apparent that a high-risk operation is not the best way to proceed. Perhaps aggressive pain management and arranging effective home support better meets the patient’s overall goals.

You don’t have to be a palliative medicine specialist to have these conversations with patients, but it does require specific communication skills, which can be taught.

For example, many clinicians start their patient encounters by giving a brief overview of the current situation or skip straight to discussions concerning the various treatment options. But are you sure you and your patient are really starting from the same place? You can’t assume that the patient/family truly understands the medical condition, no matter what may be implied in the medical record or the referring physician’s notes. And you can’t assume a patient wants an operation just because he or she shows up in your office.

A more effective way to start the conversation is to begin by asking patients what they understand about their conditions. This will ensure your subsequent discussion corrects any misinformation and better clarifies their understanding of the situation. Starting your encounter in this fashion is critical and can avoid misunderstandings that can lead to treatments the patients do not actually want, and mistrust should complications arise.

An elective rotation with palliative medicine providers to learn these skills can be a great addition to surgical residency training. These conversations can be some of the most meaningful patient interactions a physician can experience. Incorporating an elective rotation with a palliative medicine team into surgical residency training can add value to residency training and have long-lasting benefit for future surgeons, and ultimately, for their patients, as they venture on in their surgical careers.

Nadine B. Semer, M.D., MPH, FACS, is board certified in general surgery, plastic surgery, and palliative medicine. As a reconstructive plastic surgeon, she has worked not only in the United States, but has had the privilege of taking her skills to underserved and resource-poor areas throughout the world. She currently is practicing palliative medicine full time, and is an assistant professor at UT Southwestern Medical School, in Dallas, based at Parkland Hospital.

California governor signs physician-assisted suicide bill into law

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) has signed into law a controversial measure that allows physicians to help terminally ill patients legally end their lives, making California the fourth state to permit doctor-assisted suicide through its legislature.

Gov. Brown, a former seminary student, approved the End of Life Option Act Oct. 5, after state lawmakers passed the bill Sept. 11.

In a signing message, Gov. Brown said that he had considered all sides of the issue and carefully weighed religious and theological perspectives that shortening a patient’s life is sinful.

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Gov. Brown said in the message. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

Modeled after Oregon’s statute, California’s law requires two doctors to determine that a patient has 6 months or less to live before doctors could prescribe life-ending medication. Patients must have the mental capacity to make medical decisions and would physically have to be able to swallow the drugs.

In addition, patients seeking physician aid in dying must submit two oral requests, a minimum of 15 days apart, and a written request to their physician. The attending physician must receive all three requests directly from the patient and not through a designee. Before prescribing end-of-life drugs, the attending physician must refer the patient to a consulting physician for confirmation of the diagnosis and prognosis and of the patient’s capacity to make the decision.

Oregon, Vermont, and Washington each have laws permitting physician-assisted death. Court rulings in New Mexico and Montana have allowed for the practice, but litigation in those states is ongoing and the decisions have yet to be enforced.

The signing ends nearly a year of passionate debate in California that divided physicians, religious groups, lawmakers, and community members. In May, the California Medical Association (CMA) became the first state medical society to change its stance against physician-assisted suicide to that of being neutral.

“The decision to participate in the End of Life Option Act is a very personal one between a doctor and their patient, which is why CMA has removed policy that outright objects to physicians aiding terminally ill patients in end of life options,” Dr. Luther F. Cobb, CMA president, said in a statement. “We believe it is up to the individual physician and their patient to decide voluntarily whether the End of Life Option Act is something in which they want to engage. Protecting that physician-patient relationship is essential.”

The California law will take effect 90 days after the state legislature adjourns its special session on health care, which may not be until early next year. The earliest likely enactment would be spring 2016.

On Twitter @legal_med

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) has signed into law a controversial measure that allows physicians to help terminally ill patients legally end their lives, making California the fourth state to permit doctor-assisted suicide through its legislature.

Gov. Brown, a former seminary student, approved the End of Life Option Act Oct. 5, after state lawmakers passed the bill Sept. 11.

In a signing message, Gov. Brown said that he had considered all sides of the issue and carefully weighed religious and theological perspectives that shortening a patient’s life is sinful.

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Gov. Brown said in the message. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

Modeled after Oregon’s statute, California’s law requires two doctors to determine that a patient has 6 months or less to live before doctors could prescribe life-ending medication. Patients must have the mental capacity to make medical decisions and would physically have to be able to swallow the drugs.

In addition, patients seeking physician aid in dying must submit two oral requests, a minimum of 15 days apart, and a written request to their physician. The attending physician must receive all three requests directly from the patient and not through a designee. Before prescribing end-of-life drugs, the attending physician must refer the patient to a consulting physician for confirmation of the diagnosis and prognosis and of the patient’s capacity to make the decision.

Oregon, Vermont, and Washington each have laws permitting physician-assisted death. Court rulings in New Mexico and Montana have allowed for the practice, but litigation in those states is ongoing and the decisions have yet to be enforced.

The signing ends nearly a year of passionate debate in California that divided physicians, religious groups, lawmakers, and community members. In May, the California Medical Association (CMA) became the first state medical society to change its stance against physician-assisted suicide to that of being neutral.

“The decision to participate in the End of Life Option Act is a very personal one between a doctor and their patient, which is why CMA has removed policy that outright objects to physicians aiding terminally ill patients in end of life options,” Dr. Luther F. Cobb, CMA president, said in a statement. “We believe it is up to the individual physician and their patient to decide voluntarily whether the End of Life Option Act is something in which they want to engage. Protecting that physician-patient relationship is essential.”

The California law will take effect 90 days after the state legislature adjourns its special session on health care, which may not be until early next year. The earliest likely enactment would be spring 2016.

On Twitter @legal_med

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) has signed into law a controversial measure that allows physicians to help terminally ill patients legally end their lives, making California the fourth state to permit doctor-assisted suicide through its legislature.

Gov. Brown, a former seminary student, approved the End of Life Option Act Oct. 5, after state lawmakers passed the bill Sept. 11.

In a signing message, Gov. Brown said that he had considered all sides of the issue and carefully weighed religious and theological perspectives that shortening a patient’s life is sinful.

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Gov. Brown said in the message. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

Modeled after Oregon’s statute, California’s law requires two doctors to determine that a patient has 6 months or less to live before doctors could prescribe life-ending medication. Patients must have the mental capacity to make medical decisions and would physically have to be able to swallow the drugs.

In addition, patients seeking physician aid in dying must submit two oral requests, a minimum of 15 days apart, and a written request to their physician. The attending physician must receive all three requests directly from the patient and not through a designee. Before prescribing end-of-life drugs, the attending physician must refer the patient to a consulting physician for confirmation of the diagnosis and prognosis and of the patient’s capacity to make the decision.

Oregon, Vermont, and Washington each have laws permitting physician-assisted death. Court rulings in New Mexico and Montana have allowed for the practice, but litigation in those states is ongoing and the decisions have yet to be enforced.

The signing ends nearly a year of passionate debate in California that divided physicians, religious groups, lawmakers, and community members. In May, the California Medical Association (CMA) became the first state medical society to change its stance against physician-assisted suicide to that of being neutral.

“The decision to participate in the End of Life Option Act is a very personal one between a doctor and their patient, which is why CMA has removed policy that outright objects to physicians aiding terminally ill patients in end of life options,” Dr. Luther F. Cobb, CMA president, said in a statement. “We believe it is up to the individual physician and their patient to decide voluntarily whether the End of Life Option Act is something in which they want to engage. Protecting that physician-patient relationship is essential.”

The California law will take effect 90 days after the state legislature adjourns its special session on health care, which may not be until early next year. The earliest likely enactment would be spring 2016.

On Twitter @legal_med

How to Develop a Comprehensive Pediatric Palliative Care Program

For Ami Doshi, MD, FAAP, a hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego, the path to establishing a comprehensive pediatric palliative care program began with her realization during medical training that doctors didn’t always adequately address the suffering of young patients with advanced disease and their families. Then, in a hospice rotation, she saw that the palliative approach could offer a better way.

During a pediatric hospital medicine fellowship at the University of California at San Diego, Dr. Doshi conducted an educational needs assessment and then created a palliative care curriculum for residents. Rady administrators supported her attending the Palliative Care Leadership Center training at UC San Francisco, with a team from Rady and Harvard Medical School’s program in Palliative Care Education and Practice.

After five years of development, the program Dr. Doshi helped to launch at Rady has grown into a division of palliative medicine, with a medical director, an inpatient consultation service, a palliative home care program coordinated by a health navigator, and a variety of models in the outpatient clinics.

“The goal is to be seamless and to treat patients across the continuum of care,” says Dr. Doshi, who is now board certified in hospice and palliative. Although she is based in the division of hospital medicine, she leads sit-down rounds with the full palliative care team and bioethics consultants every other week.

“Finding time for this work is always a challenge,” she says, adding that administrative support for physicians’ protected time is growing and that the program is ramping up its data collection to document outcomes resulting from palliative care.

For more information on the program, email her at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

For Ami Doshi, MD, FAAP, a hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego, the path to establishing a comprehensive pediatric palliative care program began with her realization during medical training that doctors didn’t always adequately address the suffering of young patients with advanced disease and their families. Then, in a hospice rotation, she saw that the palliative approach could offer a better way.

During a pediatric hospital medicine fellowship at the University of California at San Diego, Dr. Doshi conducted an educational needs assessment and then created a palliative care curriculum for residents. Rady administrators supported her attending the Palliative Care Leadership Center training at UC San Francisco, with a team from Rady and Harvard Medical School’s program in Palliative Care Education and Practice.

After five years of development, the program Dr. Doshi helped to launch at Rady has grown into a division of palliative medicine, with a medical director, an inpatient consultation service, a palliative home care program coordinated by a health navigator, and a variety of models in the outpatient clinics.

“The goal is to be seamless and to treat patients across the continuum of care,” says Dr. Doshi, who is now board certified in hospice and palliative. Although she is based in the division of hospital medicine, she leads sit-down rounds with the full palliative care team and bioethics consultants every other week.

“Finding time for this work is always a challenge,” she says, adding that administrative support for physicians’ protected time is growing and that the program is ramping up its data collection to document outcomes resulting from palliative care.

For more information on the program, email her at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

For Ami Doshi, MD, FAAP, a hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego, the path to establishing a comprehensive pediatric palliative care program began with her realization during medical training that doctors didn’t always adequately address the suffering of young patients with advanced disease and their families. Then, in a hospice rotation, she saw that the palliative approach could offer a better way.

During a pediatric hospital medicine fellowship at the University of California at San Diego, Dr. Doshi conducted an educational needs assessment and then created a palliative care curriculum for residents. Rady administrators supported her attending the Palliative Care Leadership Center training at UC San Francisco, with a team from Rady and Harvard Medical School’s program in Palliative Care Education and Practice.

After five years of development, the program Dr. Doshi helped to launch at Rady has grown into a division of palliative medicine, with a medical director, an inpatient consultation service, a palliative home care program coordinated by a health navigator, and a variety of models in the outpatient clinics.

“The goal is to be seamless and to treat patients across the continuum of care,” says Dr. Doshi, who is now board certified in hospice and palliative. Although she is based in the division of hospital medicine, she leads sit-down rounds with the full palliative care team and bioethics consultants every other week.

“Finding time for this work is always a challenge,” she says, adding that administrative support for physicians’ protected time is growing and that the program is ramping up its data collection to document outcomes resulting from palliative care.

For more information on the program, email her at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

Promise of Genetics-Based Medicine on Display at Annual Meeting

Neither the threat of a government shutdown nor a hurricane could dampen spirits at the recently concluded 2015 AVAHO annual meeting. More than 400 physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and tumor registrars focused on hematology and oncology care convened in Washington, DC, for the meeting. Mary Thomas, MS, CNS, AOCN,was named president elect, and Anita Aggarwal, DO, took over as president from Joao Ascensao, MD.

The meeting opened with a look at the progress over the past 25 years since the launch of the Human Genome Project. Eric D. Green, MD, PhD, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health, delivered a keynote address, kicking off the meeting, followed by more in-depth discussions of incorporating value into care by Robert Nussbaum, MD, clinical professor at the University of California San Francisco.

The ability to screen for specific genetic mutations within a patient and to better identify specific mutations within a cancer cell is already transforming the ability of providers to personalize care. Even more promising, however, is the increasing awareness of the role of inheritance in individual variation in drug-response phenotypes, explained Richard Weinshilboum, MD, of the division of clinical pharmacology at Mayo Clinic’s department of molecular pharmacology and experimental therapeutics.

If the meeting opened with a focus on the promise of ’nomics-based medicine, it closed with a focus on the importance of compassionate care at the VA. Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, director and professor, nursing research and education associate director for nursing research at California-based City of Hope, delivered a second keynote on the science and research behind quality of life measures and the essential role of empathy to personalized medicine. The meeting concluded with a dynamic discussion of difficult conversations with patients, from diagnosis to end of life planning.

Neither the threat of a government shutdown nor a hurricane could dampen spirits at the recently concluded 2015 AVAHO annual meeting. More than 400 physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and tumor registrars focused on hematology and oncology care convened in Washington, DC, for the meeting. Mary Thomas, MS, CNS, AOCN,was named president elect, and Anita Aggarwal, DO, took over as president from Joao Ascensao, MD.

The meeting opened with a look at the progress over the past 25 years since the launch of the Human Genome Project. Eric D. Green, MD, PhD, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health, delivered a keynote address, kicking off the meeting, followed by more in-depth discussions of incorporating value into care by Robert Nussbaum, MD, clinical professor at the University of California San Francisco.

The ability to screen for specific genetic mutations within a patient and to better identify specific mutations within a cancer cell is already transforming the ability of providers to personalize care. Even more promising, however, is the increasing awareness of the role of inheritance in individual variation in drug-response phenotypes, explained Richard Weinshilboum, MD, of the division of clinical pharmacology at Mayo Clinic’s department of molecular pharmacology and experimental therapeutics.

If the meeting opened with a focus on the promise of ’nomics-based medicine, it closed with a focus on the importance of compassionate care at the VA. Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, director and professor, nursing research and education associate director for nursing research at California-based City of Hope, delivered a second keynote on the science and research behind quality of life measures and the essential role of empathy to personalized medicine. The meeting concluded with a dynamic discussion of difficult conversations with patients, from diagnosis to end of life planning.

Neither the threat of a government shutdown nor a hurricane could dampen spirits at the recently concluded 2015 AVAHO annual meeting. More than 400 physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and tumor registrars focused on hematology and oncology care convened in Washington, DC, for the meeting. Mary Thomas, MS, CNS, AOCN,was named president elect, and Anita Aggarwal, DO, took over as president from Joao Ascensao, MD.

The meeting opened with a look at the progress over the past 25 years since the launch of the Human Genome Project. Eric D. Green, MD, PhD, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health, delivered a keynote address, kicking off the meeting, followed by more in-depth discussions of incorporating value into care by Robert Nussbaum, MD, clinical professor at the University of California San Francisco.

The ability to screen for specific genetic mutations within a patient and to better identify specific mutations within a cancer cell is already transforming the ability of providers to personalize care. Even more promising, however, is the increasing awareness of the role of inheritance in individual variation in drug-response phenotypes, explained Richard Weinshilboum, MD, of the division of clinical pharmacology at Mayo Clinic’s department of molecular pharmacology and experimental therapeutics.

If the meeting opened with a focus on the promise of ’nomics-based medicine, it closed with a focus on the importance of compassionate care at the VA. Betty Ferrell, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, director and professor, nursing research and education associate director for nursing research at California-based City of Hope, delivered a second keynote on the science and research behind quality of life measures and the essential role of empathy to personalized medicine. The meeting concluded with a dynamic discussion of difficult conversations with patients, from diagnosis to end of life planning.

The Use of a Telehealth Clinic to Support Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy at a Site Distant From Their PCP

Purpose: To try to integrate primary care support from the “spoke” facility during the treatment of patients receiving radiation treatments at the “hub” facility.

Background: Twenty percent of the patients receiving radiation therapy at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center must relocate for up to several months in order to receive their daily treatments due to their distance from the tertiary radiation oncology unit. This makes it impossible for the patients to easily access their primary care provider (PCP) while they are out of town. Patients run out of routine medications, lose weight, have changes in renal function, and require changes in medication during this time; they must then access care via the hub emergency department (ED) or admission. In addition, the provider at the “spoke” is not necessarily in the loop regarding these patients.

Methods: We performed an analysis of the satisfaction with the current process, ED visits, and admissions of radiation oncology caregivers and patients using the Veterans House.

Results: Of patients treated with radiotherapy from April 2013, to April 1, 2014, 106 veterans stayed in the Veterans House. Patients who received palliative care with local PCPs were currently being treated at the time of the analysis or declined radiotherapy prior to starting treatment were excluded, leaving 61 patients. Of the 61 patients, there were a total of 48 ED visits and 24 admissions accounting for 168 patient-days in the hospital. A root cause analysis was performed on these 48 ED visits; 56% of those were felt to be preventable.

Discussion: After several PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycles which did not work (involving hub PCPs, involving the ED), we were successful in setting up routine weekly telehealth visits between the patient in Indianapolis at the radiation oncology unit hub and the PCP in the distant facilities in Danville and Peoria, Illinois. This allowed the PCP to manage antihypertensives, diabetic medications, and so on, as the patient moved through the radiation process.

Implications: This pilot process should decrease ED visits and admissions during radiation therapy and also serve to tighten the relationship between the hub and spoke facilities during subspecialist treatment.

Purpose: To try to integrate primary care support from the “spoke” facility during the treatment of patients receiving radiation treatments at the “hub” facility.

Background: Twenty percent of the patients receiving radiation therapy at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center must relocate for up to several months in order to receive their daily treatments due to their distance from the tertiary radiation oncology unit. This makes it impossible for the patients to easily access their primary care provider (PCP) while they are out of town. Patients run out of routine medications, lose weight, have changes in renal function, and require changes in medication during this time; they must then access care via the hub emergency department (ED) or admission. In addition, the provider at the “spoke” is not necessarily in the loop regarding these patients.

Methods: We performed an analysis of the satisfaction with the current process, ED visits, and admissions of radiation oncology caregivers and patients using the Veterans House.

Results: Of patients treated with radiotherapy from April 2013, to April 1, 2014, 106 veterans stayed in the Veterans House. Patients who received palliative care with local PCPs were currently being treated at the time of the analysis or declined radiotherapy prior to starting treatment were excluded, leaving 61 patients. Of the 61 patients, there were a total of 48 ED visits and 24 admissions accounting for 168 patient-days in the hospital. A root cause analysis was performed on these 48 ED visits; 56% of those were felt to be preventable.

Discussion: After several PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycles which did not work (involving hub PCPs, involving the ED), we were successful in setting up routine weekly telehealth visits between the patient in Indianapolis at the radiation oncology unit hub and the PCP in the distant facilities in Danville and Peoria, Illinois. This allowed the PCP to manage antihypertensives, diabetic medications, and so on, as the patient moved through the radiation process.

Implications: This pilot process should decrease ED visits and admissions during radiation therapy and also serve to tighten the relationship between the hub and spoke facilities during subspecialist treatment.