User login

A Systems Engineering and Decision-Support Tool to Enhance Care of Veterans Diagnosed With Prostate Cancer

In the U.S. in 2015, there were more than 220,800 new cases of prostate cancer and about 27,000 deaths due to prostate cancer. Across the VHA, prostate cancer is the most common nonskin cancer malignancy, and more than 25,000 patients are diagnosed yearly.1 Patients who receive treatment for prostate cancer have excellent rates of disease-specific survival: nearly 100% at 5 years, 99% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

Prostate cancer is one of several cancers that can be treated successfully with radiotherapy alone, and its success or failure is defined by a discrete numerical value from the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test. Failure occurs when the PSA is 2.0 ng/mL greater than the lowest PSA value posttreatment.2 Multiple clinical trials have used this method to determine whether or not a certain intervention is successful.

Although high rates of survival and clear biochemical indicators exist, patients diagnosed with and treated for prostate cancer are at significant risk of PSA failure. The risk can range from 5% to 70% by 10 years, depending on the the treatment modality, risk group, and series reported.3 These patients require long-term follow-up for disease recurrence and management of adverse effects. The current guidelines recommend annual follow-up care 5 years after treatment.4

The number of veterans requiring follow-up care for prostate cancer constitutes a disproportionately large share of visits compared with those of other cancers, such as cancers of the head and neck region, chest, or gastrointestinal system, and there are many challenges to providing quality long-term care. Veterans in rural locations face barriers to accessing follow-up care for effective management.

Missed appointments can compromise long-term care, escalating the risk of nonadherence over time. Missed appointments occur commonly and may negatively impact outcomes and can restrict care for other patients.5 In a recently published article by Percac-Lima and colleagues, no-show rates among 5 cancer center clinics at the Massachusetts General Hospital were as high as 10%.6

Missed appointments have also been associated with decreased quality of care and increased resource use.7 Patients with prostate cancer who miss follow-up visits are at risk for having their cancer progress to the point it becomes symptomatic and no longer treatable with salvage therapies. These patients also risk lost efficacy of treatments that are still available.

Due to these challenges, automated PSA tracking systems can be an effective way to ensure that quality, longterm care is provided to the patient. The purpose of the PSA tracking system is to identify patients who require intervention before they present with clinical problems. A PSA tracking system helps prevent patients being inappropriately lost to follow-up or missing a needed followup PSA blood test. The tracker would serve to correctly identify, among thousands or millions of patients in the electronic medical record system (EMR), which patients were at risk of failure or active failing biochemically by triggering an alert to the cancer specialist to assess that patient’s chart and determine whether a higher level of intervention is required. It could also serve to avoid unnecessary travel or inconvenience to a patient whose prostate cancer disease status can correctly be confirmed as under control by a simple blood test and related to the patient by phone, letter, or online.

Prostate-specific antigen trackers have been used to monitor patients for postprostatectomy treatment failures on a small scale in Ireland.8 For a PSA tracker to be successful, the system must have access to all posttreatment PSA data. The VHA is uniquely positioned to leverage this information because most patients who receive treatment for prostate cancer at a VHA facility stay within the VHA system for follow-up care. All laboratory data are also collected and stored in the EMR system, which is sent daily to the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

Project Proposal

In November 2014, the Office of Rural Health and the National Radiation Oncology Program Office issued a request for proposal for projects that would improve follow-up care for rural patients with prostate cancer following treatment with radiotherapy. A team of health care providers at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC drafted a proposal to address this problem. Veterans Engineering Resource Centers (VERCs) in Pittsburgh and New England were also included in the proposal as key collaborators. Staff from these 2 centers brought expertise in analytics, implementation, and project management to help rapidly innovate and implement a PSA tracking system.

The proposal was submitted on time and required approval at multiple levels, including facility and VISN leadership. It was essential that the perceived value of the proposal be readily apparent to all stakeholders, or the necessary approvals would not have been obtainable.

The proposal was accepted, and funds were transferred in February 2015. Four core team members led rapid cycle design and prototyping of the PSA tracking system. The project lead and sponsor was a radiation oncologist and service line chief at the Hunter Holmes Mc-Guire VAMC who provided overall strategy, direction, and clinical domain knowledge. A VERC engineer provided project management and analytic expertise, and a VERC developer designed code to pull data from the VA CDW and led design of the user interface. Finally, a nurse practitioner dedicated numerous hours to review charts, contact patients, write notes, and provide user feedback on the system.

Development

The purpose of the radiation oncology-centered PSA tracking system within the VA was to identify patients who require intervention following definitive treatment with radiotherapy before they present with clinical problems from disease recurrence. The PSA tracker that the authors developed was based on a relatively simple algorithm that sorts through thousands of patient records and identifies patients who had a diagnosis of prostate cancer but did not have metastatic disease, were treated at the Hunter Homes McGuire VAMC with radiation therapy, were not seen in clinic within the past 400 days, and did not have a PSA drawn within 450 days or had a rising PSA of 0.5 or more above the lowest PSA value posttreatment. In other words, the tracker uses the power of the CDW to successfully identify the exact charts that need to be reviewed and helped ensure that patients were not lost to follow-up or did not receive appropriate care. Without the PSA tracking system, providers would not know whether or not patients were being missed.

Development of the tracker required regular team meetings with well-defined, achievable goals. The team consisted of a physician as team leader, a biostatistician with structured query language experience who had access to the CDW, and a project manager with an industrial engineering background. The team met weekly. The project was broken into several components that were achieved in series and at times in parallel. The first goal was determining whether an algorithm could be written to correctly identify patients with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC who did not have metastatic disease.

By using various values available within the CDW, such as ICD 9 codes, CPT codes, PSA laboratory values, dates, and other information, the authors were able to create a successful algorithm. The ability to complete the algorithm in a short time frame wasfacilitated by several factors: a very small group, weekly meetings, good communication, easy to understand concepts across all disciplines, ability to quickly determine whether the results of the algorithm were accurate or not, and high perceived value of the end product that served to motivate the team members. Each meeting ended with clear action items and a scheduled time for the next meeting. Throughout the design and implementation process, the team discussed any problems, planned solutions, and reviewed the status of project deliverables.

Results

The tracker has already been useful for reengaging patients in care and ensuring PSA testing is occurring at appropriate intervals. Of the more than 50,000 veterans currently alive who have received care at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC, 1,158 were treated with radiotherapy definitively for prostate cancer. A total of 455 (39%) prostate cancer survivors had not been seen in the clinic in the past 13 months. Of these patients, 294 were being followed appropriately elsewhere within the VA system. Meanwhile, 161 neither had a PSA level nor a prostate cancer follow-up appointment recorded in the past 13 months anywhere within the entire VA system. This yielded a loss-to-follow-up rate of 14% (161/1,158).

The authors found that 21 (13%) of patients had a PSA level > 2.0 ng/mL above the posttreatment nadir.9 The authors were able to review the charts of these 21 patients to assess whether or not they required or were suitable for salvage brachytherapy. Of these, 1 has been set up for salvage high-dose rate brachytherapy treatment. Out of 50,000 patients, the PSA tracker algorithm facilitated a focus on the 21 patients who were most likely to be in need, making it possible for a nurse practitioner and physician to spend just 3 hours looking at charts instead of 3,000 hours.

Sustained use of the tracker is critically important to the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC project team and for the care of its veterans. Funds to support sustaining the program have been approved for fiscal year 2016. Efforts are underway to try to scale up the program and test the feasibility of disseminating the program across the enterprise. The authors estimate that an experienced advanced care provider would spend about 8 hours a week reviewing charts, contacting patients in the program, sending letters, and reviewing nuanced cases. The program would still benefit from increased automation as well as identifying a method for obtaining appropriate workload credit for this unique program.

The next phase of development will focus on improving the user interface and allowing easier transfer of information between the tracker and notes within the Computerized Patient Record System. The team will also look into automating additional parts of the process but feels that a clinician (ideally a nurse practitioner or physician assistant working with the radiation oncologist) must be part of the team, because clinical decisions must be made based on multiple variables and patient preferences.

The development of this PSA tracking system has significant future implications for improving biochemical control and extending patient survival. The tracker could be easily adapted to monitor prostatectomy patients and PSA failures requiring early intervention with salvage radiotherapy. It has been shown in several publications that early treatment with radiotherapy while PSA is relatively low results in higher rates of long-term biochemical control.10-22

Conclusions

Access to the VA CDW was essential for the success of the PSA tracking system. Furthermore, veteran patients with prostate cancer tend toward a high rate of adherence and typically stay within the system. Prostate cancer is one of the few cancers where disease recurrence is detected and determined by a quantitative laboratory value, which lends itself well to objective arithmetical tracking and detection.

Patients with prostate cancer are at risk of recurrence years after their treatment and require a long-term follow-up that includes annual PSA checks. Identifying patients who have missed follow-up appointments and not had their PSA checked is essential for combating prostate cancer recurrences. The VA CDW makes it possible to track the majority of the patients with prostate cancer who are treated in the system and identify those most in need of early treatment or early intervention before they become

symptomatic.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about prostate cancer? American Cancer Society Website. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer key-statistics. Last revised March 12, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2016.

2. Roach M III, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

3. Grimm P, Billiet I, Bostwick D, et al. Comparative analysis of prostate-specific antigen free survival outcomes for patients with low, intermediate and high risk prostate cancer treatment by radical therapy. Results from the Prostate Cancer Results Study Group. BJU Int. 2012;109(suppl 1):22-29.

4. Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, et al. Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):1078-1085.

5. Husain-Gambles M, Neal RD, Dempsey O, Lawlor DA, Hodgson J. Missed appointments in primary care: questionnaire and focus group study of health professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(499):108-113.

6. Percac-Lima S, Cronin PR, Ryan DP, Chabner BA, Daly DA, Kimball AB. Patient navigation based on predictive modeling decreases no-show rates in cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1662-1670.

7. Hwang AS, Atlas SJ, Ashburner JM, et al. Appointment “no-shows” are an independent predictor of subsequent quality of care and resource utilization outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1426-1433.

8. Hennessey DB, Lynn C, Templeton H, Chambers K, Mulholland C. The PSA tracker: a computerised health care system initiative in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J. 2013;82(3):146-149.

9. Chang M, Troeschel S, DeSotto K, et al. Development of a Post-Radiotherapy Prostate-Specific Antigen Detection and Tracking System. Poster presented at: Genito-Urinary Cancers Symposium Annual Meeting; January 2016; San Francisco, CA.

10. Anscher MS, Clough R, Dodge R. Radiotherapy for a rising prostate-specific

antigen after radical prostatectomy: the first 10 years. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 2000;48(2):369-375.

11. Catton C, Gospodarowicz M, Warde P, et al. Adjuvant and salvage radiation

therapy after radical prostatectomy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Radiother

Oncol. 2001;59(1):51-60.

12. Cheung R, Kamat AM, de Crevoisier R, et al. Outcome of salvage radiotherapy for biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy with or without hormonal therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(1):134-140.

13. Katz MS, Zelefsky MJ, Venkatraman ES, Hummer A, Leibal SA. Predictors of biochemical outcome with salvage conformal radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):483-489.

14. Leventis AK, Shariat SF, Kattan MW, Butler EB, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM. Prediction of response to salvage radiation therapy in patients with prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):1030-1039.

15. Liauw SL, Webster WS, Pistenmaa DA, Roehrborn CG. Salvage radiotherapy for

biochemical failure of radical prostatectomy: a single-institution experience. Urology.

2003;61(6):1204-1210.

16. Maier J, Forman J, Tekyi-Mensah S, Bolton S, Patel R, Pontes JE. Salvage radiation

for a rising PSA following radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(1):50-56.

17. Perez CA, Michalski JM, Baglan K, Andriole G, Cui Q, Lockett MA. Radiation therapy for increasing prostate-specific antigen levels after radical prostatectomy. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;1(4):235-241.

18. Pisansky TM, Kozelsky TF, Myers RP, et al. Radiotherapy for isolated serum prostate specific antigen elevation after prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163(3):845-850.

19. Song DY, Thompson TL, Ramakrishnan V, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for rising or

persistent PSA after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2002;60(2):281-287.

20. Stephenson AJ, Shariat SF, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1325-1332.

21. Valicenti RK, Gomella LG, Ismail M, et al. Durable efficacy of early postoperative radiation therapy for high-risk pT3N0 prostate cancer: the importance of radiation dose. Urology. 1998;52(6):1034-1040.

22. Vicini FA, Ziaja EL, Kestin LL, et al. Treatment outcome with adjuvant and salvage irradiation after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54(1):111-117.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

In the U.S. in 2015, there were more than 220,800 new cases of prostate cancer and about 27,000 deaths due to prostate cancer. Across the VHA, prostate cancer is the most common nonskin cancer malignancy, and more than 25,000 patients are diagnosed yearly.1 Patients who receive treatment for prostate cancer have excellent rates of disease-specific survival: nearly 100% at 5 years, 99% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

Prostate cancer is one of several cancers that can be treated successfully with radiotherapy alone, and its success or failure is defined by a discrete numerical value from the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test. Failure occurs when the PSA is 2.0 ng/mL greater than the lowest PSA value posttreatment.2 Multiple clinical trials have used this method to determine whether or not a certain intervention is successful.

Although high rates of survival and clear biochemical indicators exist, patients diagnosed with and treated for prostate cancer are at significant risk of PSA failure. The risk can range from 5% to 70% by 10 years, depending on the the treatment modality, risk group, and series reported.3 These patients require long-term follow-up for disease recurrence and management of adverse effects. The current guidelines recommend annual follow-up care 5 years after treatment.4

The number of veterans requiring follow-up care for prostate cancer constitutes a disproportionately large share of visits compared with those of other cancers, such as cancers of the head and neck region, chest, or gastrointestinal system, and there are many challenges to providing quality long-term care. Veterans in rural locations face barriers to accessing follow-up care for effective management.

Missed appointments can compromise long-term care, escalating the risk of nonadherence over time. Missed appointments occur commonly and may negatively impact outcomes and can restrict care for other patients.5 In a recently published article by Percac-Lima and colleagues, no-show rates among 5 cancer center clinics at the Massachusetts General Hospital were as high as 10%.6

Missed appointments have also been associated with decreased quality of care and increased resource use.7 Patients with prostate cancer who miss follow-up visits are at risk for having their cancer progress to the point it becomes symptomatic and no longer treatable with salvage therapies. These patients also risk lost efficacy of treatments that are still available.

Due to these challenges, automated PSA tracking systems can be an effective way to ensure that quality, longterm care is provided to the patient. The purpose of the PSA tracking system is to identify patients who require intervention before they present with clinical problems. A PSA tracking system helps prevent patients being inappropriately lost to follow-up or missing a needed followup PSA blood test. The tracker would serve to correctly identify, among thousands or millions of patients in the electronic medical record system (EMR), which patients were at risk of failure or active failing biochemically by triggering an alert to the cancer specialist to assess that patient’s chart and determine whether a higher level of intervention is required. It could also serve to avoid unnecessary travel or inconvenience to a patient whose prostate cancer disease status can correctly be confirmed as under control by a simple blood test and related to the patient by phone, letter, or online.

Prostate-specific antigen trackers have been used to monitor patients for postprostatectomy treatment failures on a small scale in Ireland.8 For a PSA tracker to be successful, the system must have access to all posttreatment PSA data. The VHA is uniquely positioned to leverage this information because most patients who receive treatment for prostate cancer at a VHA facility stay within the VHA system for follow-up care. All laboratory data are also collected and stored in the EMR system, which is sent daily to the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

Project Proposal

In November 2014, the Office of Rural Health and the National Radiation Oncology Program Office issued a request for proposal for projects that would improve follow-up care for rural patients with prostate cancer following treatment with radiotherapy. A team of health care providers at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC drafted a proposal to address this problem. Veterans Engineering Resource Centers (VERCs) in Pittsburgh and New England were also included in the proposal as key collaborators. Staff from these 2 centers brought expertise in analytics, implementation, and project management to help rapidly innovate and implement a PSA tracking system.

The proposal was submitted on time and required approval at multiple levels, including facility and VISN leadership. It was essential that the perceived value of the proposal be readily apparent to all stakeholders, or the necessary approvals would not have been obtainable.

The proposal was accepted, and funds were transferred in February 2015. Four core team members led rapid cycle design and prototyping of the PSA tracking system. The project lead and sponsor was a radiation oncologist and service line chief at the Hunter Holmes Mc-Guire VAMC who provided overall strategy, direction, and clinical domain knowledge. A VERC engineer provided project management and analytic expertise, and a VERC developer designed code to pull data from the VA CDW and led design of the user interface. Finally, a nurse practitioner dedicated numerous hours to review charts, contact patients, write notes, and provide user feedback on the system.

Development

The purpose of the radiation oncology-centered PSA tracking system within the VA was to identify patients who require intervention following definitive treatment with radiotherapy before they present with clinical problems from disease recurrence. The PSA tracker that the authors developed was based on a relatively simple algorithm that sorts through thousands of patient records and identifies patients who had a diagnosis of prostate cancer but did not have metastatic disease, were treated at the Hunter Homes McGuire VAMC with radiation therapy, were not seen in clinic within the past 400 days, and did not have a PSA drawn within 450 days or had a rising PSA of 0.5 or more above the lowest PSA value posttreatment. In other words, the tracker uses the power of the CDW to successfully identify the exact charts that need to be reviewed and helped ensure that patients were not lost to follow-up or did not receive appropriate care. Without the PSA tracking system, providers would not know whether or not patients were being missed.

Development of the tracker required regular team meetings with well-defined, achievable goals. The team consisted of a physician as team leader, a biostatistician with structured query language experience who had access to the CDW, and a project manager with an industrial engineering background. The team met weekly. The project was broken into several components that were achieved in series and at times in parallel. The first goal was determining whether an algorithm could be written to correctly identify patients with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC who did not have metastatic disease.

By using various values available within the CDW, such as ICD 9 codes, CPT codes, PSA laboratory values, dates, and other information, the authors were able to create a successful algorithm. The ability to complete the algorithm in a short time frame wasfacilitated by several factors: a very small group, weekly meetings, good communication, easy to understand concepts across all disciplines, ability to quickly determine whether the results of the algorithm were accurate or not, and high perceived value of the end product that served to motivate the team members. Each meeting ended with clear action items and a scheduled time for the next meeting. Throughout the design and implementation process, the team discussed any problems, planned solutions, and reviewed the status of project deliverables.

Results

The tracker has already been useful for reengaging patients in care and ensuring PSA testing is occurring at appropriate intervals. Of the more than 50,000 veterans currently alive who have received care at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC, 1,158 were treated with radiotherapy definitively for prostate cancer. A total of 455 (39%) prostate cancer survivors had not been seen in the clinic in the past 13 months. Of these patients, 294 were being followed appropriately elsewhere within the VA system. Meanwhile, 161 neither had a PSA level nor a prostate cancer follow-up appointment recorded in the past 13 months anywhere within the entire VA system. This yielded a loss-to-follow-up rate of 14% (161/1,158).

The authors found that 21 (13%) of patients had a PSA level > 2.0 ng/mL above the posttreatment nadir.9 The authors were able to review the charts of these 21 patients to assess whether or not they required or were suitable for salvage brachytherapy. Of these, 1 has been set up for salvage high-dose rate brachytherapy treatment. Out of 50,000 patients, the PSA tracker algorithm facilitated a focus on the 21 patients who were most likely to be in need, making it possible for a nurse practitioner and physician to spend just 3 hours looking at charts instead of 3,000 hours.

Sustained use of the tracker is critically important to the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC project team and for the care of its veterans. Funds to support sustaining the program have been approved for fiscal year 2016. Efforts are underway to try to scale up the program and test the feasibility of disseminating the program across the enterprise. The authors estimate that an experienced advanced care provider would spend about 8 hours a week reviewing charts, contacting patients in the program, sending letters, and reviewing nuanced cases. The program would still benefit from increased automation as well as identifying a method for obtaining appropriate workload credit for this unique program.

The next phase of development will focus on improving the user interface and allowing easier transfer of information between the tracker and notes within the Computerized Patient Record System. The team will also look into automating additional parts of the process but feels that a clinician (ideally a nurse practitioner or physician assistant working with the radiation oncologist) must be part of the team, because clinical decisions must be made based on multiple variables and patient preferences.

The development of this PSA tracking system has significant future implications for improving biochemical control and extending patient survival. The tracker could be easily adapted to monitor prostatectomy patients and PSA failures requiring early intervention with salvage radiotherapy. It has been shown in several publications that early treatment with radiotherapy while PSA is relatively low results in higher rates of long-term biochemical control.10-22

Conclusions

Access to the VA CDW was essential for the success of the PSA tracking system. Furthermore, veteran patients with prostate cancer tend toward a high rate of adherence and typically stay within the system. Prostate cancer is one of the few cancers where disease recurrence is detected and determined by a quantitative laboratory value, which lends itself well to objective arithmetical tracking and detection.

Patients with prostate cancer are at risk of recurrence years after their treatment and require a long-term follow-up that includes annual PSA checks. Identifying patients who have missed follow-up appointments and not had their PSA checked is essential for combating prostate cancer recurrences. The VA CDW makes it possible to track the majority of the patients with prostate cancer who are treated in the system and identify those most in need of early treatment or early intervention before they become

symptomatic.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

In the U.S. in 2015, there were more than 220,800 new cases of prostate cancer and about 27,000 deaths due to prostate cancer. Across the VHA, prostate cancer is the most common nonskin cancer malignancy, and more than 25,000 patients are diagnosed yearly.1 Patients who receive treatment for prostate cancer have excellent rates of disease-specific survival: nearly 100% at 5 years, 99% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

Prostate cancer is one of several cancers that can be treated successfully with radiotherapy alone, and its success or failure is defined by a discrete numerical value from the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test. Failure occurs when the PSA is 2.0 ng/mL greater than the lowest PSA value posttreatment.2 Multiple clinical trials have used this method to determine whether or not a certain intervention is successful.

Although high rates of survival and clear biochemical indicators exist, patients diagnosed with and treated for prostate cancer are at significant risk of PSA failure. The risk can range from 5% to 70% by 10 years, depending on the the treatment modality, risk group, and series reported.3 These patients require long-term follow-up for disease recurrence and management of adverse effects. The current guidelines recommend annual follow-up care 5 years after treatment.4

The number of veterans requiring follow-up care for prostate cancer constitutes a disproportionately large share of visits compared with those of other cancers, such as cancers of the head and neck region, chest, or gastrointestinal system, and there are many challenges to providing quality long-term care. Veterans in rural locations face barriers to accessing follow-up care for effective management.

Missed appointments can compromise long-term care, escalating the risk of nonadherence over time. Missed appointments occur commonly and may negatively impact outcomes and can restrict care for other patients.5 In a recently published article by Percac-Lima and colleagues, no-show rates among 5 cancer center clinics at the Massachusetts General Hospital were as high as 10%.6

Missed appointments have also been associated with decreased quality of care and increased resource use.7 Patients with prostate cancer who miss follow-up visits are at risk for having their cancer progress to the point it becomes symptomatic and no longer treatable with salvage therapies. These patients also risk lost efficacy of treatments that are still available.

Due to these challenges, automated PSA tracking systems can be an effective way to ensure that quality, longterm care is provided to the patient. The purpose of the PSA tracking system is to identify patients who require intervention before they present with clinical problems. A PSA tracking system helps prevent patients being inappropriately lost to follow-up or missing a needed followup PSA blood test. The tracker would serve to correctly identify, among thousands or millions of patients in the electronic medical record system (EMR), which patients were at risk of failure or active failing biochemically by triggering an alert to the cancer specialist to assess that patient’s chart and determine whether a higher level of intervention is required. It could also serve to avoid unnecessary travel or inconvenience to a patient whose prostate cancer disease status can correctly be confirmed as under control by a simple blood test and related to the patient by phone, letter, or online.

Prostate-specific antigen trackers have been used to monitor patients for postprostatectomy treatment failures on a small scale in Ireland.8 For a PSA tracker to be successful, the system must have access to all posttreatment PSA data. The VHA is uniquely positioned to leverage this information because most patients who receive treatment for prostate cancer at a VHA facility stay within the VHA system for follow-up care. All laboratory data are also collected and stored in the EMR system, which is sent daily to the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

Project Proposal

In November 2014, the Office of Rural Health and the National Radiation Oncology Program Office issued a request for proposal for projects that would improve follow-up care for rural patients with prostate cancer following treatment with radiotherapy. A team of health care providers at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC drafted a proposal to address this problem. Veterans Engineering Resource Centers (VERCs) in Pittsburgh and New England were also included in the proposal as key collaborators. Staff from these 2 centers brought expertise in analytics, implementation, and project management to help rapidly innovate and implement a PSA tracking system.

The proposal was submitted on time and required approval at multiple levels, including facility and VISN leadership. It was essential that the perceived value of the proposal be readily apparent to all stakeholders, or the necessary approvals would not have been obtainable.

The proposal was accepted, and funds were transferred in February 2015. Four core team members led rapid cycle design and prototyping of the PSA tracking system. The project lead and sponsor was a radiation oncologist and service line chief at the Hunter Holmes Mc-Guire VAMC who provided overall strategy, direction, and clinical domain knowledge. A VERC engineer provided project management and analytic expertise, and a VERC developer designed code to pull data from the VA CDW and led design of the user interface. Finally, a nurse practitioner dedicated numerous hours to review charts, contact patients, write notes, and provide user feedback on the system.

Development

The purpose of the radiation oncology-centered PSA tracking system within the VA was to identify patients who require intervention following definitive treatment with radiotherapy before they present with clinical problems from disease recurrence. The PSA tracker that the authors developed was based on a relatively simple algorithm that sorts through thousands of patient records and identifies patients who had a diagnosis of prostate cancer but did not have metastatic disease, were treated at the Hunter Homes McGuire VAMC with radiation therapy, were not seen in clinic within the past 400 days, and did not have a PSA drawn within 450 days or had a rising PSA of 0.5 or more above the lowest PSA value posttreatment. In other words, the tracker uses the power of the CDW to successfully identify the exact charts that need to be reviewed and helped ensure that patients were not lost to follow-up or did not receive appropriate care. Without the PSA tracking system, providers would not know whether or not patients were being missed.

Development of the tracker required regular team meetings with well-defined, achievable goals. The team consisted of a physician as team leader, a biostatistician with structured query language experience who had access to the CDW, and a project manager with an industrial engineering background. The team met weekly. The project was broken into several components that were achieved in series and at times in parallel. The first goal was determining whether an algorithm could be written to correctly identify patients with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC who did not have metastatic disease.

By using various values available within the CDW, such as ICD 9 codes, CPT codes, PSA laboratory values, dates, and other information, the authors were able to create a successful algorithm. The ability to complete the algorithm in a short time frame wasfacilitated by several factors: a very small group, weekly meetings, good communication, easy to understand concepts across all disciplines, ability to quickly determine whether the results of the algorithm were accurate or not, and high perceived value of the end product that served to motivate the team members. Each meeting ended with clear action items and a scheduled time for the next meeting. Throughout the design and implementation process, the team discussed any problems, planned solutions, and reviewed the status of project deliverables.

Results

The tracker has already been useful for reengaging patients in care and ensuring PSA testing is occurring at appropriate intervals. Of the more than 50,000 veterans currently alive who have received care at the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC, 1,158 were treated with radiotherapy definitively for prostate cancer. A total of 455 (39%) prostate cancer survivors had not been seen in the clinic in the past 13 months. Of these patients, 294 were being followed appropriately elsewhere within the VA system. Meanwhile, 161 neither had a PSA level nor a prostate cancer follow-up appointment recorded in the past 13 months anywhere within the entire VA system. This yielded a loss-to-follow-up rate of 14% (161/1,158).

The authors found that 21 (13%) of patients had a PSA level > 2.0 ng/mL above the posttreatment nadir.9 The authors were able to review the charts of these 21 patients to assess whether or not they required or were suitable for salvage brachytherapy. Of these, 1 has been set up for salvage high-dose rate brachytherapy treatment. Out of 50,000 patients, the PSA tracker algorithm facilitated a focus on the 21 patients who were most likely to be in need, making it possible for a nurse practitioner and physician to spend just 3 hours looking at charts instead of 3,000 hours.

Sustained use of the tracker is critically important to the Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC project team and for the care of its veterans. Funds to support sustaining the program have been approved for fiscal year 2016. Efforts are underway to try to scale up the program and test the feasibility of disseminating the program across the enterprise. The authors estimate that an experienced advanced care provider would spend about 8 hours a week reviewing charts, contacting patients in the program, sending letters, and reviewing nuanced cases. The program would still benefit from increased automation as well as identifying a method for obtaining appropriate workload credit for this unique program.

The next phase of development will focus on improving the user interface and allowing easier transfer of information between the tracker and notes within the Computerized Patient Record System. The team will also look into automating additional parts of the process but feels that a clinician (ideally a nurse practitioner or physician assistant working with the radiation oncologist) must be part of the team, because clinical decisions must be made based on multiple variables and patient preferences.

The development of this PSA tracking system has significant future implications for improving biochemical control and extending patient survival. The tracker could be easily adapted to monitor prostatectomy patients and PSA failures requiring early intervention with salvage radiotherapy. It has been shown in several publications that early treatment with radiotherapy while PSA is relatively low results in higher rates of long-term biochemical control.10-22

Conclusions

Access to the VA CDW was essential for the success of the PSA tracking system. Furthermore, veteran patients with prostate cancer tend toward a high rate of adherence and typically stay within the system. Prostate cancer is one of the few cancers where disease recurrence is detected and determined by a quantitative laboratory value, which lends itself well to objective arithmetical tracking and detection.

Patients with prostate cancer are at risk of recurrence years after their treatment and require a long-term follow-up that includes annual PSA checks. Identifying patients who have missed follow-up appointments and not had their PSA checked is essential for combating prostate cancer recurrences. The VA CDW makes it possible to track the majority of the patients with prostate cancer who are treated in the system and identify those most in need of early treatment or early intervention before they become

symptomatic.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about prostate cancer? American Cancer Society Website. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer key-statistics. Last revised March 12, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2016.

2. Roach M III, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

3. Grimm P, Billiet I, Bostwick D, et al. Comparative analysis of prostate-specific antigen free survival outcomes for patients with low, intermediate and high risk prostate cancer treatment by radical therapy. Results from the Prostate Cancer Results Study Group. BJU Int. 2012;109(suppl 1):22-29.

4. Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, et al. Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):1078-1085.

5. Husain-Gambles M, Neal RD, Dempsey O, Lawlor DA, Hodgson J. Missed appointments in primary care: questionnaire and focus group study of health professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(499):108-113.

6. Percac-Lima S, Cronin PR, Ryan DP, Chabner BA, Daly DA, Kimball AB. Patient navigation based on predictive modeling decreases no-show rates in cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1662-1670.

7. Hwang AS, Atlas SJ, Ashburner JM, et al. Appointment “no-shows” are an independent predictor of subsequent quality of care and resource utilization outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1426-1433.

8. Hennessey DB, Lynn C, Templeton H, Chambers K, Mulholland C. The PSA tracker: a computerised health care system initiative in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J. 2013;82(3):146-149.

9. Chang M, Troeschel S, DeSotto K, et al. Development of a Post-Radiotherapy Prostate-Specific Antigen Detection and Tracking System. Poster presented at: Genito-Urinary Cancers Symposium Annual Meeting; January 2016; San Francisco, CA.

10. Anscher MS, Clough R, Dodge R. Radiotherapy for a rising prostate-specific

antigen after radical prostatectomy: the first 10 years. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 2000;48(2):369-375.

11. Catton C, Gospodarowicz M, Warde P, et al. Adjuvant and salvage radiation

therapy after radical prostatectomy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Radiother

Oncol. 2001;59(1):51-60.

12. Cheung R, Kamat AM, de Crevoisier R, et al. Outcome of salvage radiotherapy for biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy with or without hormonal therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(1):134-140.

13. Katz MS, Zelefsky MJ, Venkatraman ES, Hummer A, Leibal SA. Predictors of biochemical outcome with salvage conformal radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):483-489.

14. Leventis AK, Shariat SF, Kattan MW, Butler EB, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM. Prediction of response to salvage radiation therapy in patients with prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):1030-1039.

15. Liauw SL, Webster WS, Pistenmaa DA, Roehrborn CG. Salvage radiotherapy for

biochemical failure of radical prostatectomy: a single-institution experience. Urology.

2003;61(6):1204-1210.

16. Maier J, Forman J, Tekyi-Mensah S, Bolton S, Patel R, Pontes JE. Salvage radiation

for a rising PSA following radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(1):50-56.

17. Perez CA, Michalski JM, Baglan K, Andriole G, Cui Q, Lockett MA. Radiation therapy for increasing prostate-specific antigen levels after radical prostatectomy. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;1(4):235-241.

18. Pisansky TM, Kozelsky TF, Myers RP, et al. Radiotherapy for isolated serum prostate specific antigen elevation after prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163(3):845-850.

19. Song DY, Thompson TL, Ramakrishnan V, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for rising or

persistent PSA after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2002;60(2):281-287.

20. Stephenson AJ, Shariat SF, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1325-1332.

21. Valicenti RK, Gomella LG, Ismail M, et al. Durable efficacy of early postoperative radiation therapy for high-risk pT3N0 prostate cancer: the importance of radiation dose. Urology. 1998;52(6):1034-1040.

22. Vicini FA, Ziaja EL, Kestin LL, et al. Treatment outcome with adjuvant and salvage irradiation after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54(1):111-117.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about prostate cancer? American Cancer Society Website. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer key-statistics. Last revised March 12, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2016.

2. Roach M III, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

3. Grimm P, Billiet I, Bostwick D, et al. Comparative analysis of prostate-specific antigen free survival outcomes for patients with low, intermediate and high risk prostate cancer treatment by radical therapy. Results from the Prostate Cancer Results Study Group. BJU Int. 2012;109(suppl 1):22-29.

4. Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, et al. Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):1078-1085.

5. Husain-Gambles M, Neal RD, Dempsey O, Lawlor DA, Hodgson J. Missed appointments in primary care: questionnaire and focus group study of health professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(499):108-113.

6. Percac-Lima S, Cronin PR, Ryan DP, Chabner BA, Daly DA, Kimball AB. Patient navigation based on predictive modeling decreases no-show rates in cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1662-1670.

7. Hwang AS, Atlas SJ, Ashburner JM, et al. Appointment “no-shows” are an independent predictor of subsequent quality of care and resource utilization outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1426-1433.

8. Hennessey DB, Lynn C, Templeton H, Chambers K, Mulholland C. The PSA tracker: a computerised health care system initiative in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J. 2013;82(3):146-149.

9. Chang M, Troeschel S, DeSotto K, et al. Development of a Post-Radiotherapy Prostate-Specific Antigen Detection and Tracking System. Poster presented at: Genito-Urinary Cancers Symposium Annual Meeting; January 2016; San Francisco, CA.

10. Anscher MS, Clough R, Dodge R. Radiotherapy for a rising prostate-specific

antigen after radical prostatectomy: the first 10 years. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 2000;48(2):369-375.

11. Catton C, Gospodarowicz M, Warde P, et al. Adjuvant and salvage radiation

therapy after radical prostatectomy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Radiother

Oncol. 2001;59(1):51-60.

12. Cheung R, Kamat AM, de Crevoisier R, et al. Outcome of salvage radiotherapy for biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy with or without hormonal therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(1):134-140.

13. Katz MS, Zelefsky MJ, Venkatraman ES, Hummer A, Leibal SA. Predictors of biochemical outcome with salvage conformal radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):483-489.

14. Leventis AK, Shariat SF, Kattan MW, Butler EB, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM. Prediction of response to salvage radiation therapy in patients with prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):1030-1039.

15. Liauw SL, Webster WS, Pistenmaa DA, Roehrborn CG. Salvage radiotherapy for

biochemical failure of radical prostatectomy: a single-institution experience. Urology.

2003;61(6):1204-1210.

16. Maier J, Forman J, Tekyi-Mensah S, Bolton S, Patel R, Pontes JE. Salvage radiation

for a rising PSA following radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(1):50-56.

17. Perez CA, Michalski JM, Baglan K, Andriole G, Cui Q, Lockett MA. Radiation therapy for increasing prostate-specific antigen levels after radical prostatectomy. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;1(4):235-241.

18. Pisansky TM, Kozelsky TF, Myers RP, et al. Radiotherapy for isolated serum prostate specific antigen elevation after prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163(3):845-850.

19. Song DY, Thompson TL, Ramakrishnan V, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for rising or

persistent PSA after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2002;60(2):281-287.

20. Stephenson AJ, Shariat SF, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1325-1332.

21. Valicenti RK, Gomella LG, Ismail M, et al. Durable efficacy of early postoperative radiation therapy for high-risk pT3N0 prostate cancer: the importance of radiation dose. Urology. 1998;52(6):1034-1040.

22. Vicini FA, Ziaja EL, Kestin LL, et al. Treatment outcome with adjuvant and salvage irradiation after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54(1):111-117.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

The ethics of ICDs: History and future directions

In 1975, Julia and Joseph Quinlan approached the administrator of St. Clare’s Hospital in Denville, New Jersey, and requested that the mechanical ventilator on which their adopted daughter, Karen, was dependent be turned off. Karen Ann Quinlan, 21 years old, was in a permanent vegetative state after a severe anoxic event, and her parents had been informed by the hospital’s medical staff that she would never regain consciousness.

To the Quinlans’ request to withdraw the ventilator, the hospital administrator replied, “You have to understand our position, Mrs. Quinlan. In this hospital we don’t kill people.”1

The administrator’s response was consistent with prevailing ethical and legal perspectives, analyses, and directives at that time related to discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment. In the mid-1970s, the American Medical Association’s position was that it was permissible to not put a patient on a ventilator (ie, a physician could withhold a life-sustaining treatment), but once a patient was on a ventilator, it was not permissible to take the patient off if the intention was to allow death to occur.1 However, the New Jersey Supreme Court ultimately found this distinction between withholding and withdrawing unconvincing, and ruled unanimously that Karen Quinlan’s ventilator could be turned off.2

THE HASTINGS CENTER REPORT: STOPPING IS THE SAME AS NOT STARTING

During the subsequent decade, further ethical analysis and additional legal cases resulted in new insights and more nuanced thinking about forgoing life-sustaining treatment.

These developments were summarized in a 1987 report by the Hastings Center,3 a leading bioethics research and policy institute. The report provided normative guidance for the termination of life-sustaining treatment and for the care of dying patients. It acknowledged that deciding not to start a life-sustaining treatment can emotionally and psychologically affect healthcare professionals differently than deciding to stop such a treatment. However, the report also asserted that there is no morally important difference between withholding and withdrawing such treatments.

Reflecting a partnership model between patients and professionals for healthcare decision-making, and affirming the ethical significance of both a burden-benefit analysis and patient autonomy, the report stated that when a patient or surrogate in collaboration with a responsible healthcare professional decides that a treatment under way and the life it supports have become more burdensome than beneficial to the patient, that is sufficient reason to stop. There is no ethical requirement that treatment, once initiated, must continue against the patient’s wishes or when the surrogate determines that it is more burdensome than beneficial from the patient’s perspective. In fact, imposing treatment in such circumstances violates the patient’s right to self-determination.3

The report noted further that, because of frequent uncertainty about the efficacy of proposed treatments, it is preferable to initiate time-limited trials of treatments and then later stop them if they prove ineffective or become overly burdensome from a patient’s perspective.

ICDs ARE LIKE OTHER LIFE-SUSTAINING THERAPIES

In this issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Baibars et al4 address the question of how implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) should be managed at the end of life. The historical events and developments recounted above regarding withdrawing life-sustaining technologies are an appropriate context for ethically assessing the management of ICDs for dying patients.

Obviously, ICDs are not ventilators, but like ventilators, they are life-sustaining therapy, as are dialysis machines, blood transfusions, medically supplied nutrition and hydration, ventricular assist devices, and other implantable electronic cardiac devices such as pacemakers. Each of these life-sustaining therapies, depending on a patient’s clinical condition, underlying illness, and comorbidities, can become a death-prolonging technology.

An ethical framework and analysis about whether to continue any life-sustaining therapy, including an ICD, must include an assessment of the benefit-to-burden ratio from the patient’s perspective. Does the therapy enhance or maintain a quality of life acceptable to the patient? Or has it become overly burdensome and does it maintain a quality of life the patient finds (or would find) unacceptable? If the latter is true, and especially in the context of an underlying terminal condition, then shifting the goals of care to focus on comfort is always appropriate and ethically justified. Treatments—including ICDs—that do not contribute to patient comfort should be withdrawn.

TOWARD COMPETENCY IN ETHICAL MANAGEMENT

Baibars et al note that much more needs to be done to enhance competencies, increase proficiencies, and mitigate the moral distress of healthcare professionals caring for dying patients with ICDs and other devices. To help clinicians achieve a personal and professional “comfort zone” for ethically managing patients with ICDs, we recommend that healthcare institutions, medical schools, and nursing schools take the following steps:

Develop comprehensive end-of-life policies, procedures, and protocols that incorporate specific guidance for managing cardiac devices and that have been endorsed by a hospital ethics committee. Such guidance can be informative and educational and can ensure that decisions and resulting actions (including stopping cardiac devices) are ethically supportable.

Provide more palliative care training in medical and nursing schools, residency programs, and continuing education activities so that front-line clinicians can deliver “basic,” “primary” palliative care not requiring specialty palliative medicine. This training, called for in the Institute of Medicine’s 2014 report, Dying in America,5 should include explicit ethics discussions about managing cardiac devices at the end of life.

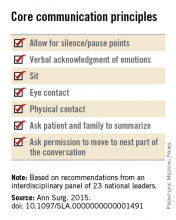

Provide ongoing training in communication skills needed for all patient-professional encounters. Effectively engaging patients in goals-of-care discussions, especially patients with life-limiting illnesses such as heart failure, cannot be achieved without these skills.

- Pence G. Comas: Karen Quinlan and Nancy Cruzan. In: Classic Cases in Medical Ethics: Accounts of Cases That Have Shaped Medical Ethics, With Philosophical, Legal, and Historical Backgrounds, 3rd edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2000:29–55.

- In the matter of Karen Quinlan, an alleged incompetent. In re Quinlan. 70 N.J. 10, 355 A.2d 647 (1976), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 922 (1976).

- Wolf SM. Hastings Center. Guidelines on the Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care of the Dying: A Report by the Hastings Center. The Hastings Center: Briarcliff Manor, NY; 1987.

- Baibars MM, Alraies MC, Kabach A, Pritzker M. Can patients opt to turn off implantable cardioverter-defibrillators near the end of life? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:97–98.

- National Academy of Sciences. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual p near the end of life. www.iom.edu/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-P-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx. Accessed January 4, 2016.

In 1975, Julia and Joseph Quinlan approached the administrator of St. Clare’s Hospital in Denville, New Jersey, and requested that the mechanical ventilator on which their adopted daughter, Karen, was dependent be turned off. Karen Ann Quinlan, 21 years old, was in a permanent vegetative state after a severe anoxic event, and her parents had been informed by the hospital’s medical staff that she would never regain consciousness.

To the Quinlans’ request to withdraw the ventilator, the hospital administrator replied, “You have to understand our position, Mrs. Quinlan. In this hospital we don’t kill people.”1

The administrator’s response was consistent with prevailing ethical and legal perspectives, analyses, and directives at that time related to discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment. In the mid-1970s, the American Medical Association’s position was that it was permissible to not put a patient on a ventilator (ie, a physician could withhold a life-sustaining treatment), but once a patient was on a ventilator, it was not permissible to take the patient off if the intention was to allow death to occur.1 However, the New Jersey Supreme Court ultimately found this distinction between withholding and withdrawing unconvincing, and ruled unanimously that Karen Quinlan’s ventilator could be turned off.2

THE HASTINGS CENTER REPORT: STOPPING IS THE SAME AS NOT STARTING

During the subsequent decade, further ethical analysis and additional legal cases resulted in new insights and more nuanced thinking about forgoing life-sustaining treatment.

These developments were summarized in a 1987 report by the Hastings Center,3 a leading bioethics research and policy institute. The report provided normative guidance for the termination of life-sustaining treatment and for the care of dying patients. It acknowledged that deciding not to start a life-sustaining treatment can emotionally and psychologically affect healthcare professionals differently than deciding to stop such a treatment. However, the report also asserted that there is no morally important difference between withholding and withdrawing such treatments.

Reflecting a partnership model between patients and professionals for healthcare decision-making, and affirming the ethical significance of both a burden-benefit analysis and patient autonomy, the report stated that when a patient or surrogate in collaboration with a responsible healthcare professional decides that a treatment under way and the life it supports have become more burdensome than beneficial to the patient, that is sufficient reason to stop. There is no ethical requirement that treatment, once initiated, must continue against the patient’s wishes or when the surrogate determines that it is more burdensome than beneficial from the patient’s perspective. In fact, imposing treatment in such circumstances violates the patient’s right to self-determination.3

The report noted further that, because of frequent uncertainty about the efficacy of proposed treatments, it is preferable to initiate time-limited trials of treatments and then later stop them if they prove ineffective or become overly burdensome from a patient’s perspective.

ICDs ARE LIKE OTHER LIFE-SUSTAINING THERAPIES

In this issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Baibars et al4 address the question of how implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) should be managed at the end of life. The historical events and developments recounted above regarding withdrawing life-sustaining technologies are an appropriate context for ethically assessing the management of ICDs for dying patients.

Obviously, ICDs are not ventilators, but like ventilators, they are life-sustaining therapy, as are dialysis machines, blood transfusions, medically supplied nutrition and hydration, ventricular assist devices, and other implantable electronic cardiac devices such as pacemakers. Each of these life-sustaining therapies, depending on a patient’s clinical condition, underlying illness, and comorbidities, can become a death-prolonging technology.

An ethical framework and analysis about whether to continue any life-sustaining therapy, including an ICD, must include an assessment of the benefit-to-burden ratio from the patient’s perspective. Does the therapy enhance or maintain a quality of life acceptable to the patient? Or has it become overly burdensome and does it maintain a quality of life the patient finds (or would find) unacceptable? If the latter is true, and especially in the context of an underlying terminal condition, then shifting the goals of care to focus on comfort is always appropriate and ethically justified. Treatments—including ICDs—that do not contribute to patient comfort should be withdrawn.

TOWARD COMPETENCY IN ETHICAL MANAGEMENT

Baibars et al note that much more needs to be done to enhance competencies, increase proficiencies, and mitigate the moral distress of healthcare professionals caring for dying patients with ICDs and other devices. To help clinicians achieve a personal and professional “comfort zone” for ethically managing patients with ICDs, we recommend that healthcare institutions, medical schools, and nursing schools take the following steps:

Develop comprehensive end-of-life policies, procedures, and protocols that incorporate specific guidance for managing cardiac devices and that have been endorsed by a hospital ethics committee. Such guidance can be informative and educational and can ensure that decisions and resulting actions (including stopping cardiac devices) are ethically supportable.

Provide more palliative care training in medical and nursing schools, residency programs, and continuing education activities so that front-line clinicians can deliver “basic,” “primary” palliative care not requiring specialty palliative medicine. This training, called for in the Institute of Medicine’s 2014 report, Dying in America,5 should include explicit ethics discussions about managing cardiac devices at the end of life.

Provide ongoing training in communication skills needed for all patient-professional encounters. Effectively engaging patients in goals-of-care discussions, especially patients with life-limiting illnesses such as heart failure, cannot be achieved without these skills.

In 1975, Julia and Joseph Quinlan approached the administrator of St. Clare’s Hospital in Denville, New Jersey, and requested that the mechanical ventilator on which their adopted daughter, Karen, was dependent be turned off. Karen Ann Quinlan, 21 years old, was in a permanent vegetative state after a severe anoxic event, and her parents had been informed by the hospital’s medical staff that she would never regain consciousness.

To the Quinlans’ request to withdraw the ventilator, the hospital administrator replied, “You have to understand our position, Mrs. Quinlan. In this hospital we don’t kill people.”1

The administrator’s response was consistent with prevailing ethical and legal perspectives, analyses, and directives at that time related to discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment. In the mid-1970s, the American Medical Association’s position was that it was permissible to not put a patient on a ventilator (ie, a physician could withhold a life-sustaining treatment), but once a patient was on a ventilator, it was not permissible to take the patient off if the intention was to allow death to occur.1 However, the New Jersey Supreme Court ultimately found this distinction between withholding and withdrawing unconvincing, and ruled unanimously that Karen Quinlan’s ventilator could be turned off.2

THE HASTINGS CENTER REPORT: STOPPING IS THE SAME AS NOT STARTING

During the subsequent decade, further ethical analysis and additional legal cases resulted in new insights and more nuanced thinking about forgoing life-sustaining treatment.

These developments were summarized in a 1987 report by the Hastings Center,3 a leading bioethics research and policy institute. The report provided normative guidance for the termination of life-sustaining treatment and for the care of dying patients. It acknowledged that deciding not to start a life-sustaining treatment can emotionally and psychologically affect healthcare professionals differently than deciding to stop such a treatment. However, the report also asserted that there is no morally important difference between withholding and withdrawing such treatments.

Reflecting a partnership model between patients and professionals for healthcare decision-making, and affirming the ethical significance of both a burden-benefit analysis and patient autonomy, the report stated that when a patient or surrogate in collaboration with a responsible healthcare professional decides that a treatment under way and the life it supports have become more burdensome than beneficial to the patient, that is sufficient reason to stop. There is no ethical requirement that treatment, once initiated, must continue against the patient’s wishes or when the surrogate determines that it is more burdensome than beneficial from the patient’s perspective. In fact, imposing treatment in such circumstances violates the patient’s right to self-determination.3

The report noted further that, because of frequent uncertainty about the efficacy of proposed treatments, it is preferable to initiate time-limited trials of treatments and then later stop them if they prove ineffective or become overly burdensome from a patient’s perspective.

ICDs ARE LIKE OTHER LIFE-SUSTAINING THERAPIES

In this issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Baibars et al4 address the question of how implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) should be managed at the end of life. The historical events and developments recounted above regarding withdrawing life-sustaining technologies are an appropriate context for ethically assessing the management of ICDs for dying patients.

Obviously, ICDs are not ventilators, but like ventilators, they are life-sustaining therapy, as are dialysis machines, blood transfusions, medically supplied nutrition and hydration, ventricular assist devices, and other implantable electronic cardiac devices such as pacemakers. Each of these life-sustaining therapies, depending on a patient’s clinical condition, underlying illness, and comorbidities, can become a death-prolonging technology.

An ethical framework and analysis about whether to continue any life-sustaining therapy, including an ICD, must include an assessment of the benefit-to-burden ratio from the patient’s perspective. Does the therapy enhance or maintain a quality of life acceptable to the patient? Or has it become overly burdensome and does it maintain a quality of life the patient finds (or would find) unacceptable? If the latter is true, and especially in the context of an underlying terminal condition, then shifting the goals of care to focus on comfort is always appropriate and ethically justified. Treatments—including ICDs—that do not contribute to patient comfort should be withdrawn.

TOWARD COMPETENCY IN ETHICAL MANAGEMENT

Baibars et al note that much more needs to be done to enhance competencies, increase proficiencies, and mitigate the moral distress of healthcare professionals caring for dying patients with ICDs and other devices. To help clinicians achieve a personal and professional “comfort zone” for ethically managing patients with ICDs, we recommend that healthcare institutions, medical schools, and nursing schools take the following steps:

Develop comprehensive end-of-life policies, procedures, and protocols that incorporate specific guidance for managing cardiac devices and that have been endorsed by a hospital ethics committee. Such guidance can be informative and educational and can ensure that decisions and resulting actions (including stopping cardiac devices) are ethically supportable.

Provide more palliative care training in medical and nursing schools, residency programs, and continuing education activities so that front-line clinicians can deliver “basic,” “primary” palliative care not requiring specialty palliative medicine. This training, called for in the Institute of Medicine’s 2014 report, Dying in America,5 should include explicit ethics discussions about managing cardiac devices at the end of life.

Provide ongoing training in communication skills needed for all patient-professional encounters. Effectively engaging patients in goals-of-care discussions, especially patients with life-limiting illnesses such as heart failure, cannot be achieved without these skills.

- Pence G. Comas: Karen Quinlan and Nancy Cruzan. In: Classic Cases in Medical Ethics: Accounts of Cases That Have Shaped Medical Ethics, With Philosophical, Legal, and Historical Backgrounds, 3rd edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2000:29–55.

- In the matter of Karen Quinlan, an alleged incompetent. In re Quinlan. 70 N.J. 10, 355 A.2d 647 (1976), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 922 (1976).

- Wolf SM. Hastings Center. Guidelines on the Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care of the Dying: A Report by the Hastings Center. The Hastings Center: Briarcliff Manor, NY; 1987.

- Baibars MM, Alraies MC, Kabach A, Pritzker M. Can patients opt to turn off implantable cardioverter-defibrillators near the end of life? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:97–98.

- National Academy of Sciences. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual p near the end of life. www.iom.edu/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-P-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx. Accessed January 4, 2016.

- Pence G. Comas: Karen Quinlan and Nancy Cruzan. In: Classic Cases in Medical Ethics: Accounts of Cases That Have Shaped Medical Ethics, With Philosophical, Legal, and Historical Backgrounds, 3rd edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2000:29–55.

- In the matter of Karen Quinlan, an alleged incompetent. In re Quinlan. 70 N.J. 10, 355 A.2d 647 (1976), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 922 (1976).

- Wolf SM. Hastings Center. Guidelines on the Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care of the Dying: A Report by the Hastings Center. The Hastings Center: Briarcliff Manor, NY; 1987.

- Baibars MM, Alraies MC, Kabach A, Pritzker M. Can patients opt to turn off implantable cardioverter-defibrillators near the end of life? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:97–98.

- National Academy of Sciences. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual p near the end of life. www.iom.edu/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-P-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx. Accessed January 4, 2016.

Can patients opt to turn off implantable cardioverter-defibrillators near the end of life?

Yes. Although implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) prevent sudden cardiac death in patients with advanced heart failure, their benefit in terminally ill patients is small.1 Furthermore, the shocks they deliver at the end of life can cause distress. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider ICD deactivation if the patient or family wishes.

A DIFFICULT DECISION

End-of-life decisions place significant emotional burdens on patients, their families, and their healthcare providers and can have social and legal consequences.

Turning off an ICD is an especially difficult decision, considering that these devices protect against sudden cardiac death and fatal arrhythmias. Also, patients and their representatives may find it more difficult to withdraw from active care than to forgo further interventions (more on this below), and they may misunderstand discussions about ICD deactivation, perceiving them as the beginning of abandonment.

ICD DEACTIVATION IS OFTEN DONE HAPHAZARDLY OR NOT AT ALL

Many healthcare providers are not trained in or comfortable with discussing end-of-life issues, and many hospitals and hospice programs lack policies and protocols for managing implanted devices at the end of life. Consequently, ICD management at the end of life varies among providers and tends to be suboptimal.2

In a report of a survey in 414 hospice facilities, 97% of facilities reported that they admitted patients with ICDs, but only 10% had a policy on device deactivation.3

In a survey of 47 European medical centers, only 4% said they addressed ICD deactivation with their patients.4

A study of 125 patients with ICDs who had died found that 52% had do-not-resuscitate orders. Nevertheless, in 100 patients the ICD had remained active in the last 24 hours of their life, and 31 of these patients had received shocks during their last 24 hours.5

In a survey of next of kin of patients with ICDs who had died of any cause,6 in only 27 of 100 cases had the clinician discussed ICD deactivation, and about three-fourths of these discussions had occurred during the last few days of life. Twenty-seven patients had received ICD discharges in the last month of life, and 8% had received a discharge during the final minutes.

TRAINING AND PROTOCOLS ARE NEEDED

Healthcare professionals need education about device deactivation at the end of life so that they are comfortable communicating with patients and families about this critical issue. To this end, several cardiac and palliative care societies have jointly released an expert statement on managing ICDs and other implantable devices in end-of-life situations.7

Many providers harbor a misunderstanding of the difference between withholding a device and withdrawing (or turning off) a device that is already implanted.2 Some mistakenly believe they would be committing a crime by deactivating an implanted life-sustaining device. Legally and ethically, there is no difference between withholding a device and withdrawing a device. Legally, carrying out a request to withdraw life-sustaining treatment is neither physician-assisted suicide nor euthanasia.

DISCUSSION SHOULD BEGIN EARLY AND SHOULD BE ONGOING

The discussion of ICD deactivation should begin before the device is implanted and should continue as the patient’s health status changes. In a survey, 40% of patients said they felt that ICD deactivation should be discussed before the device is implanted, and only 5% felt that this discussion should be undertaken in the last days of life.8

At the least, it is important to identify patients with ICDs on admission to hospice and to have policies in place that ensure adequate patient education to make an informed decision about ICD deactivation at the end of life.

The topic should be discussed when goals of care change and when do-not-resuscitate status is addressed, and also when advanced directives are being acknowledged. If the patient or his or her legal representative wishes to keep the ICD turned on, that wish should be respected. The essence of a discussion is not to impose the providers’ choice on the patient, but to help the patient make the right decision for himself or herself. Of note, patients entering hospice do not have to have do-not-resuscitate status.