User login

2019 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

Through the years, the surgical approach to hysterectomy has expanded from its early beginnings of being performed only through an abdominal or transvaginal route with traditional surgical clamps and suture. The late 1980s saw the advent of the laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH), and from that point forward several additional hysterectomy methods evolved, including today’s robotic approaches.

Although clinical evidence and societal endorsements support vaginal hysterectomy as a superior high-value modality, it remains one of the least performed among all available routes.1-3 In an analysis of inpatient hysterectomies published by Wright and colleagues in 2013, 16.7% of hysterectomies were performed vaginally, a number that essentially has remained steady throughout the ensuing years.4

Attempts to improve the application of vaginal hysterectomy have been made.5 These include the development of various curriculum and simulation-based medical education programs on vaginal surgical skills training and acquisition in the hopes of improving utilization.6 An interesting recent development is the rethinking of vaginal hysterectomy by several surgeons globally who are applying facets of the various hysterectomy methods to a transvaginal approach known as vaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (vNOTES).7,8 Unique to this thinking is the incorporation of conventional laparoscopic instrumentation.

Although I have not yet incorporated this approach in my surgical armamentarium at Columbia University Medical Center/New York–Presbyterian Hospital, I am intrigued by the possibility that this technique may serve as a rescue for vaginal hysterectomies that are at risk of conversion or of not being performed at all.9

At this time, vNOTES is not a standard of care and should be performed only by highly specialized surgeons. However, in the spirit of this Update on minimally invasive surgery and to keep our readers abreast of burgeoning techniques, I am delighted to bring you this overview by Dr. Xiaoming Guan, one of the pioneers of this surgical approach, and Dr. Tamisa Koythong and Dr. Juan Liu. I hope you find this recent development in hysterectomy of interest.

—Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Continue to: Development and evolution of NOTES...

Development and evolution of NOTES

Over the past few decades, emphasis has shifted from laparotomy to minimally invasive surgery because of its proven significant advantages in patient care, such as improved cosmesis, shorter hospital stay, shorter postoperative recovery, and decreased postoperative pain and blood loss.10 Advances in laparoendoscopic surgery and instrumentation, including robot-assisted laparoscopy (RAL), single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), and most recently natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES), reflect ongoing innovative developments in the field of minimally invasive surgery.

Here, we provide a brief literature review of the NOTES technique, focus on its application in gynecologic surgery, and describe how we perform NOTES at our institution.

NOTES application in gynecology

With NOTES, peritoneal access is gained through a natural orifice (such as the mouth, vagina, urethra, or anus) to perform endoscopic surgery, occasionally without requiring an abdominal incision. First described in 2004, transgastric peritoneoscopy was performed in a porcine model, and shortly thereafter the first transgastric appendectomy was performed in humans.11,12 The technique has further been adopted in cholecystectomy, appendectomy, gastrectomy, and nephrectomy procedures.13

Given rapid interest in a possible paradigm shift in the field of minimally invasive surgery, the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortiumfor Assessment and Research (NOSCAR) was formed, and the group published an article on potential barriers to accepted practice and adoption of NOTES as a realistic alternative to traditional laparoscopic surgery.14

While transgastric and transanal access to the peritoneum were initially more popular, the risk of anastomotic leaks associated with incomplete closure and subsequent infection were thought to be prohibitively high.15 Transvaginal access was considered a safer and simpler alternative, allowing for complete closure without increased risk of infection, and this is now the route through which the majority of NOTES procedures are completed.16,17

The eventual application of NOTES in the field of gynecology seemed inevitable. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that transvaginal surgery is the most minimally invasive and preferred surgical route in the management of patients with benign gynecologic diseases.18 However, performing it can be challenging at times due to limited visualization and lack of the required skills for single-site surgery. NOTES allows a gynecologic surgeon to improve visualization through the use of laparoendoscopic instruments and to complete surgery through a transvaginal route.

In 2012, Ahn and colleagues demonstrated the feasibility of the NOTES technique in gynecologic surgery after using it to successfully complete benign adnexal surgery in 10 patients.19 Vaginal NOTES (vNOTES) has since been further developed to include successful hysterectomy, myomectomy, sacrocolpopexy, tubal anastomosis, and even lymphadenectomy in the treatment of early- stage endometrial carcinoma.20-26 vNOTES also can be considered a rescue approach for traditional vaginal hysterectomy in instances in which it is necessary to evaluate adnexal pathology.9 Most recently, vNOTES hysterectomy has been reported with da Vinci Si or Xi robotic platforms.27,28

Continue to: Operative time, post-op stay shorter in NAOC-treated patients...

Operative time, post-op stay shorter in NAOC-treated patients

Few studies have compared outcomes with vNOTES to those with traditional laparoscopy. In 2016, Wang and colleagues compared surgical outcomes between NOTES-assisted ovarian cystectomy (NAOC) and laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy (LOC) in a case-matched study that included 277 patients.29 Although mean (SD) blood loss in patients who underwent LOC was significantly less compared with those who underwent NAOC (21.4 [14.7] mL vs 31.6 [24.1] mL; P = .028), absolute blood loss in both groups was deemed minimal. Additionally, mean (SD) operative time and postoperative stay were significantly less in patients undergoing NAOC compared with those having LOC (38.23 [10.19] minutes vs 53.82 [18.61] minutes; P≤.001; and 1.38 [0.55] days vs 1.82 [0.52] days; P≤.001; respectively).29

How vNOTES hysterectomy stacked up against TLH

In 2018, Baekelandt and colleagues compared outcomes between vNOTES hysterectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) in a noninferiority single-blinded trial of 70 women.8 Compared with TLH, vNOTES hysterectomy was associated with shorter operative time (41 vs 75 minutes; P<.001), shorter hospital stay (0.8 vs 1.3 days; P = .004), and lower postoperative analgesic requirement (8 vs 14 U; P = .006). Additionally, there were no differences between the 2 groups in postoperative infection rate, intraoperative complications, or hospital readmissions within 6 weeks.8

Clearly, vNOTES is the next exciting development in minimally invasive surgery, improving patient outcomes and satisfaction with truly scarless surgery. Compared with traditional transvaginal surgery, vNOTES has the advantage of improved visualization with laparoendoscopic guidance, and it may be beneficial even for patients previously thought to have relative contraindications to successful completion of transvaginal surgery, such as nulliparity or a narrow introitus.

Approach for performing vNOTES procedures

At our institution, Baylor College of Medicine, the majority of gynecologic surgeries are performed via either transumbilical robot-assisted single-incision laparoscopy or vNOTES. Preoperative selection of appropriate candidates for vNOTES includes:

- low suspicion for or prior diagnosis of endometriosis with obliteration of the posterior cul-de-sac

- no surgical history suggestive of severe adhesive disease, and

- adequate vaginal sidewall access and sufficient descent for instrumentation for entry into the peritoneal cavity.

In general, a key concept in vNOTES is "vaginal pull, laparoscopic push," which means that the surgeon must pull the cervix while performing vaginal entry and then push the uterus back in the peritoneal cavity to increase surgical space during laparoscopic surgery.

Continue to: Overview of vNOTES steps...

Overview of vNOTES steps

Below we break down a description of vNOTES in 6 sections. Our patients are always placed in dorsal lithotomy position with TrenGuard (D.A. Surgical) Trendelenburg restraint. We prep the abdomen in case we need to convert to transabdominal surgery via transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic surgery or traditional laparoscopic surgery.

1. Vaginal entry

Accessing the peritoneal cavity through the vagina initially proceeds like a vaginal hysterectomy. We inject dilute vasopressin (20 U in 20 mL of normal saline) circumferentially in the cervix (for hysterectomy) or in the posterior cervix in the cervicovaginal junction (for adnexal surgery without hysterectomy) for vasoconstriction and hydrodissection.

We then incise the vaginal mucosa circumferentially with electrosurgical cautery and follow with posterior colpotomy. We find that reapproximating the posterior peritoneum to the posterior vagina with either figure-of-8 stitches or a running stitch of polyglactin 910 suture (2-0 Vicryl) assists in port placement, bleeding at the peritoneal edge, and closure of the cuff or colpotomy at the end of the case. We tag this suture with a curved hemostat.

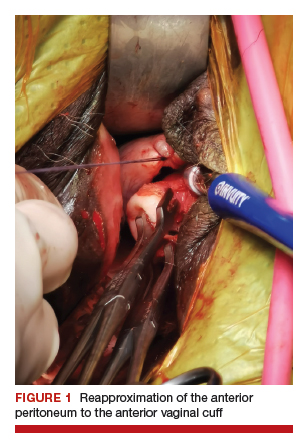

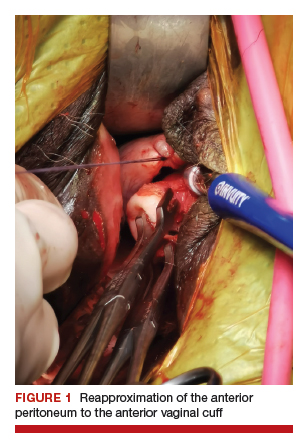

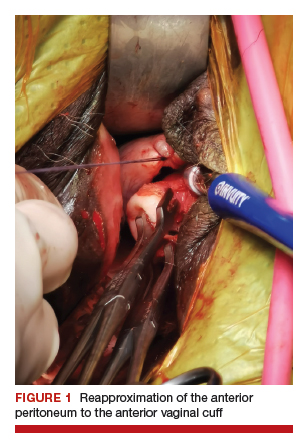

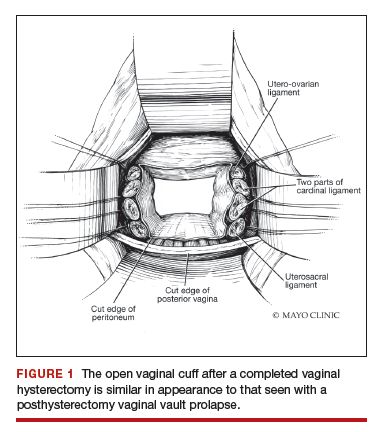

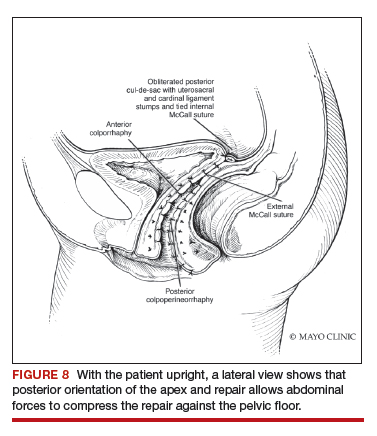

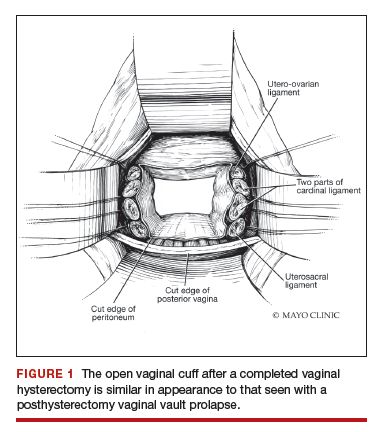

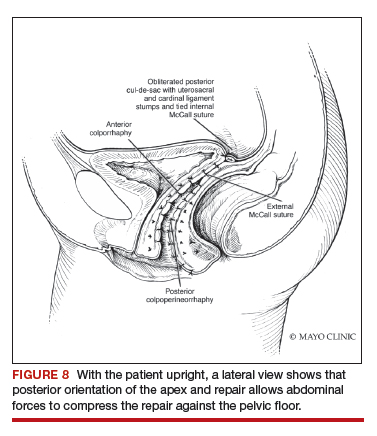

Depending on whether a hysterectomy is being performed, anterior colpotomy is made. Again, the anterior peritoneum is then tagged to the anterior vaginal cuff in similar fashion, and this suture is tagged with a different instrument; we typically use a straight hemostat or Sarot clamp (FIGURE 1).

2. Traditional vaginal hysterectomy

After colpotomy, we prefer to perform progressive clamping of the broad ligament from the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments to the level of uterine artery as in traditional vaginal hysterectomy, if feasible.

3. Single-site port placement

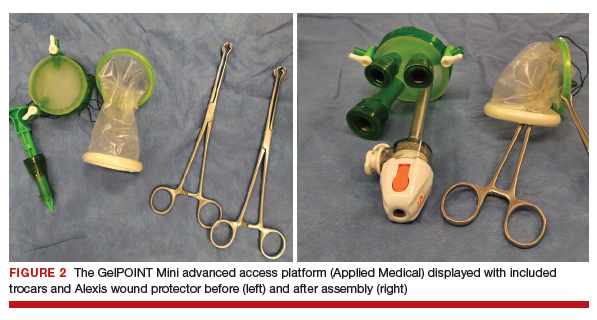

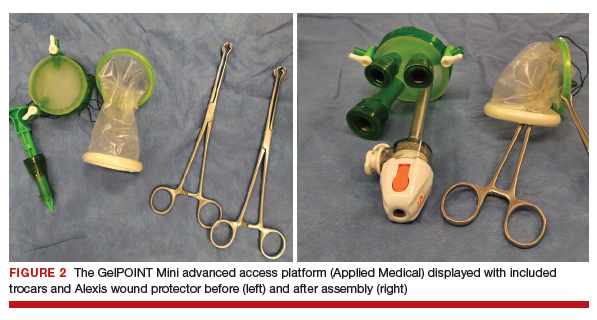

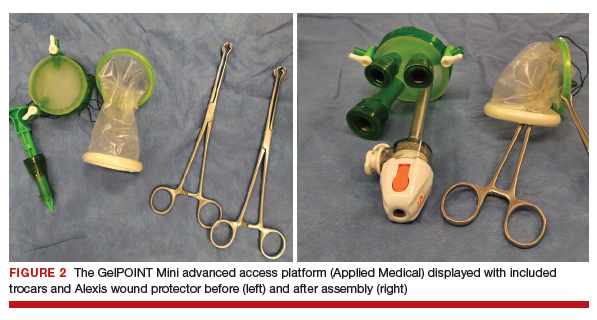

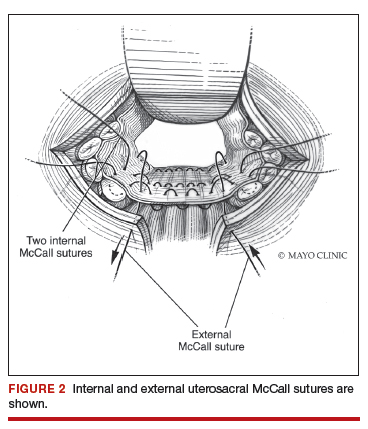

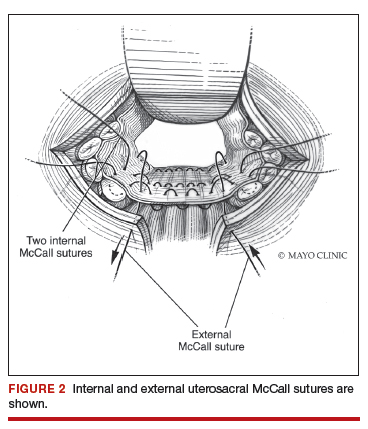

The assembled GelPOINT Mini advanced access platform (Applied Medical) (FIGURE 2) is introduced through the vagina after the Alexis wound protector (included with the kit) is first placed through the colpotomy with assistance of Babcock clamps (FIGURE 3).

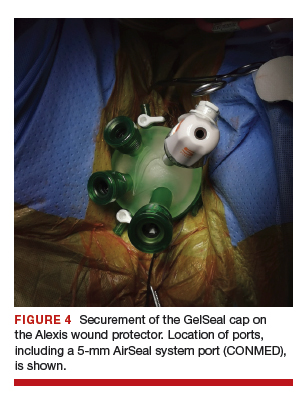

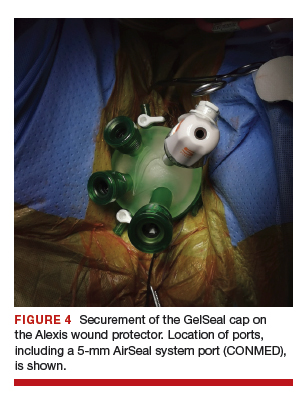

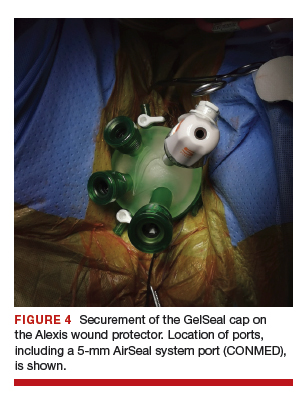

After ensuring that the green rigid ring of the Alexis wound protector is contained and completely expanded within the peritoneal cavity, we cross our previously tagged sutures as we find this helps with preventing the GelPOINT Mini access platform from inadvertently shifting out of the peritoneal cavity during surgery. The GelSeal cap is then secured and pneumoperitoneum is established (FIGURE 4).

Continue to: 4. Laparoendoscopic surgery...

4. Laparoendoscopic surgery

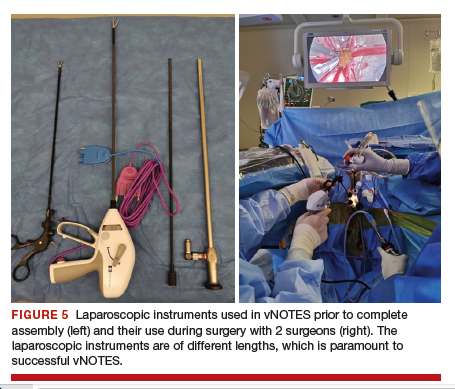

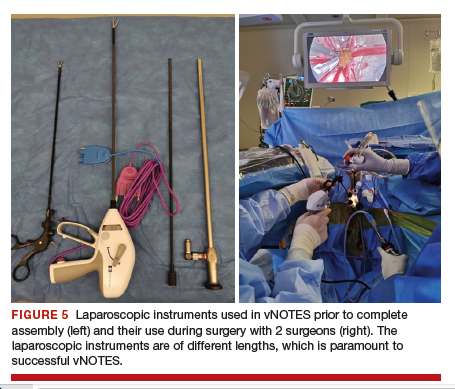

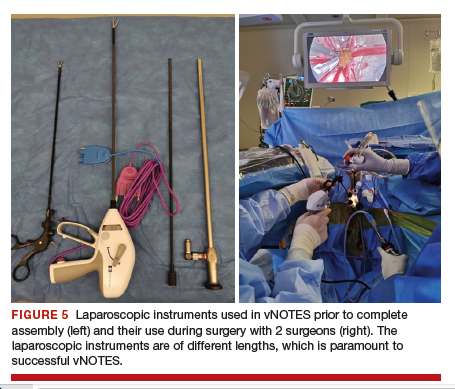

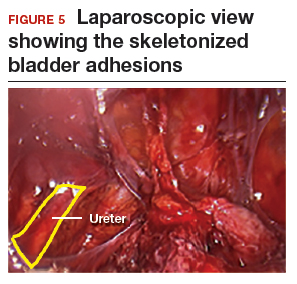

Instruments used in our surgeries include a 10-mm rigid 30° 43-cm working length laparoscope; a 44-cm LigaSure device (Medtronic); a 5-mm, 37-cm laparoscopic cobra grasping forceps and fenestrated grasper (Karl Storz); and a 5-mm, 45-cm laparoscopic suction with hydrodissection tip (Stryker) (FIGURE 5).

vNOTES allows a gynecologic surgeon the unique ability to survey the upper abdomen. The remainder of the surgery proceeds using basic laparoscopic single-site skills.

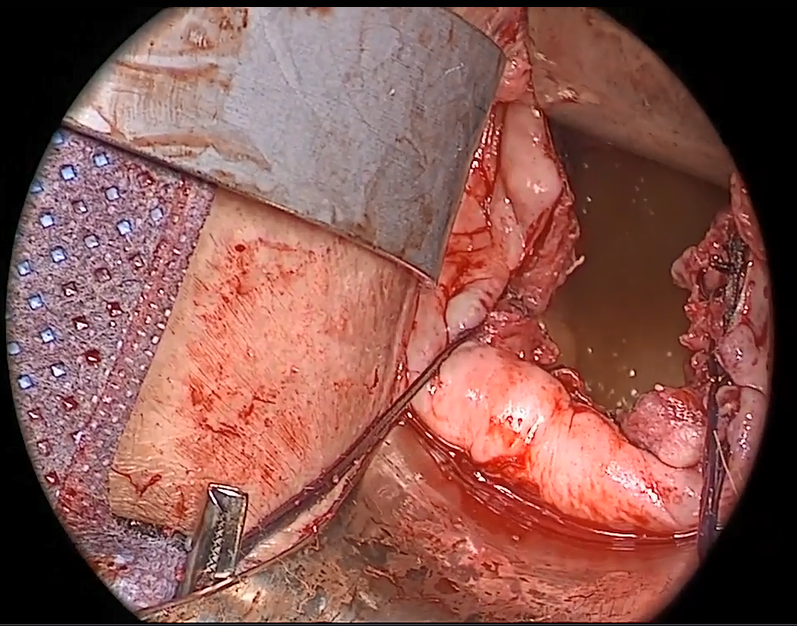

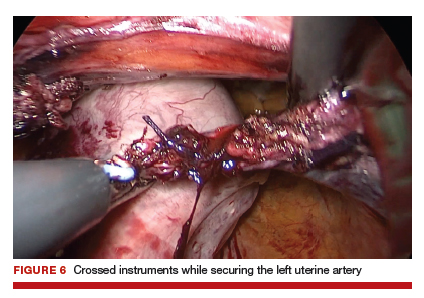

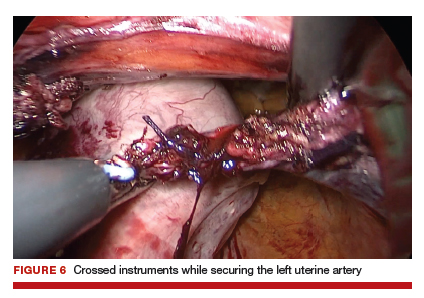

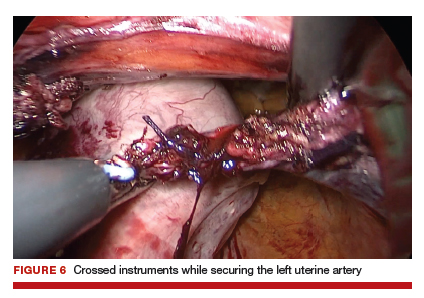

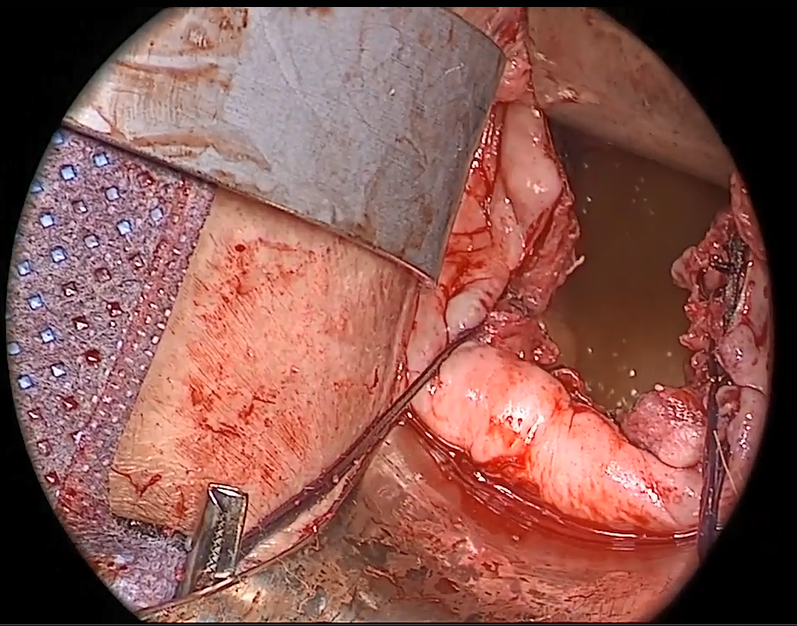

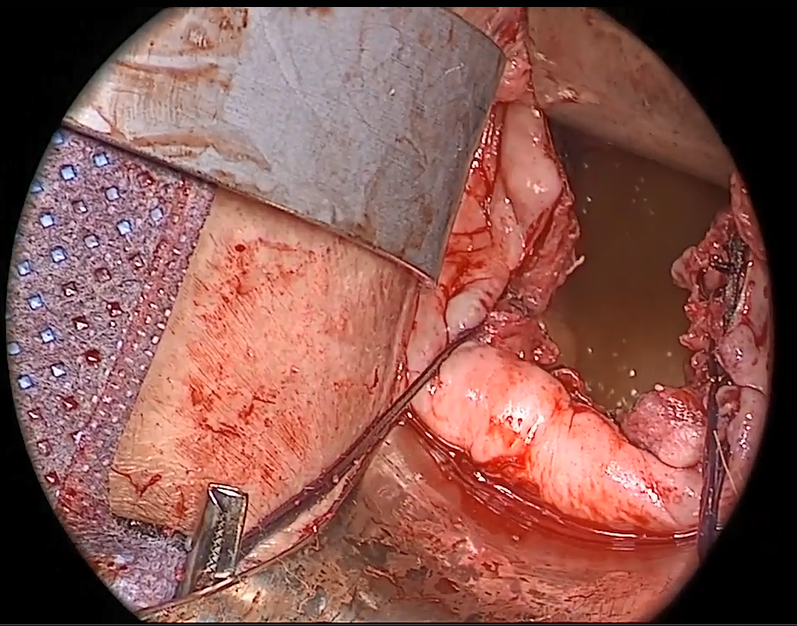

During vNOTES, as with all single-site surgical procedures, understanding the optimal placement of crossed instruments is important for successful completion. For example, when securing the right uterine artery, the surgeon needs to push the cervix toward the patient's left and slightly into the peritoneal cavity using a laparoscopic cobra grasper with his or her left hand while then securing the uterine pedicle using the LigaSure device with his or her right hand. This is then reversed when securing the left uterine artery, where the assistant surgeon pushes the cervix toward the patient's right while the surgeon secures the pedicle ("vaginal pull, laparoscopic push") (FIGURE 6).

This again is reiterated in securing the ovarian pedicles, which are pushed into the peritoneal cavity while being secured with the LigaSure device.

5. Specimen removal

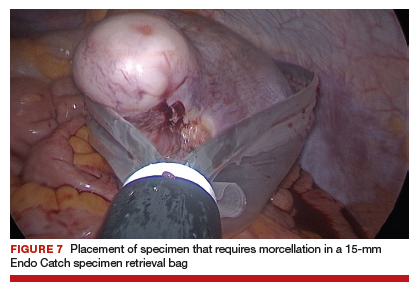

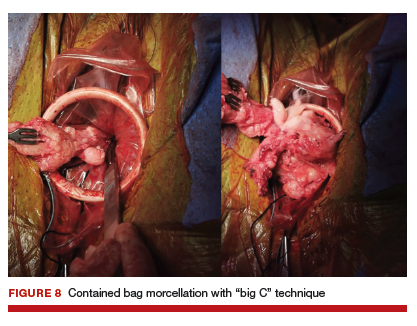

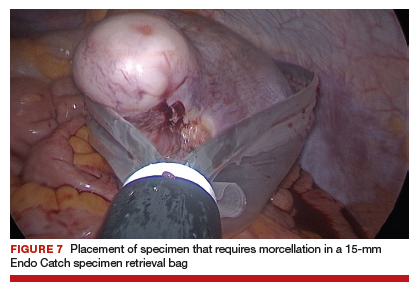

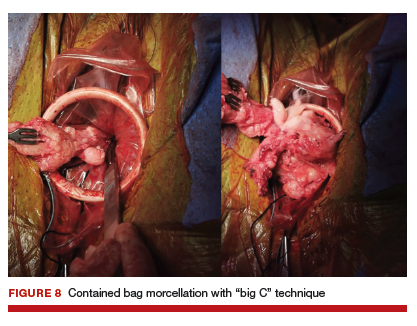

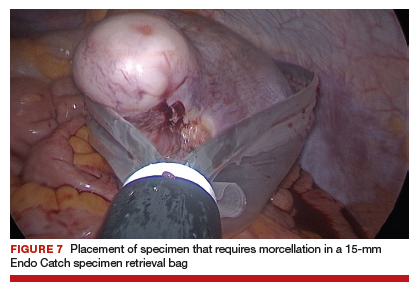

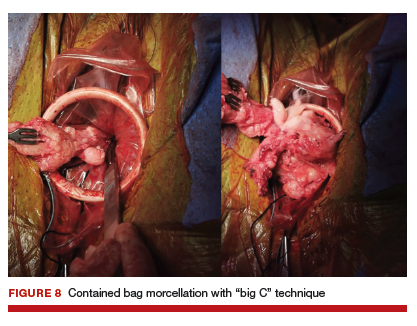

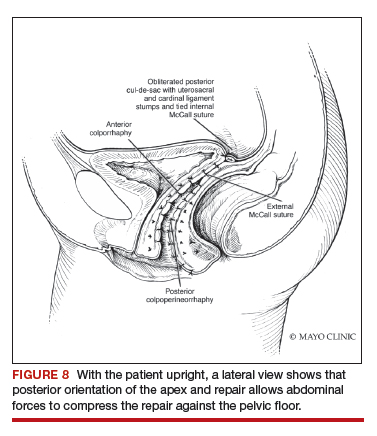

For large uteri or specimens that need morcellation, a 15-mm Endo Catch specimen retrieval bag (Medtronic) is introduced through the GelPOINT Mini system. The specimen is then placed in the bag and delivered to the vagina, where contained bag morcellation is performed in standard fashion (FIGURES 7 AND 8). We utilized the "big C" technique by first grasping the specimen with a penetrating clamp. The clamp is then held in our nondominant hand and a No. 10 blade scalpel is used to create a reverse c-incision, keeping one surface of the specimen intact. This is continued until the specimen can be completely delivered through the vagina.

Specimens that do not require morcellation can be grasped laparoscopically, brought to the GelPOINT Mini port, which is quickly disassembled, and delivered. The GelSeal cap is then reassembled.

6. Vaginal cuff closure

The colpotomy or vaginal cuff is closed with barbed suture continuously, as in traditional vaginal hysterectomy cuff closure. Uterosacral ligament suspension should be performed for vaginal cuff support.

vNOTES is the most recent innovative development in the field of minimally invasive surgery, and it has demonstrated feasibility and safety in the fields of general surgery, urology, and gynecology. Adopting vNOTES in clinical practice can improve patient satisfaction and cosmesis as well as surgical outcomes. Gynecologic surgeons can think of vNOTES hysterectomy as "placing an eye" in the vagina while performing transvaginal hysterectomy. The surgical principle of "vaginal pull, laparoscopic push" facilitates the learning process.

1. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 444. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-1158.

2. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3.

3. Whiteside JL, Kaeser CT, Ridgeway B. Achieving high value in the surgical approach to hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:242-245.

4. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233-241.

5. Moen M, Walter A, Harmanli O, et al. Considerations to improve the evidence-based use of vaginal hysterectomy in benign gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:585-588.

6. Balgobin S, Owens DM, Florian-Rodriguez ME, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy suturing skills training model and curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:553-558.

7. Baekelandt J. Total vaginal NOTES hysterectomy: a new approach to hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1088-1094.

8. Baekelandt JF, De Mulder PA, Le Roy I, et al. Hysterectomy by transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery versus laparoscopy as a day-care procedure: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2019;126:105-113.

9. Guan X, Bardawil E, Liu J, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery as a rescue for total vaginal hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:1135-1136.

10. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD003677.

11. Kalloo AN, Singh VK, Jagannath SB, et al. Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: a novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:114-117.

12. Reddy N, Rao P. Per oral transgastric endoscopic appendectomy in human. Paper Presented at: 45th Annual Conference of the Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy of India; February 28-29, 2004; Jaipur, India.

13. Clark MP, Qayed ES, Kooby DA, et al. Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery in humans: a review. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;189296.

14. Rattner D, Kalloo A; ASGE/SAGES Working Group. ASGE/ SAGES Working Group on natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery, October 2005. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:329-333.

15. Autorino R, Yakoubi R, White WM, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): where are we going? A bibliometric assessment. BJU Int. 2013;111:11-16.

16. Santos BF, Hungness ES. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: progress in humans since the white paper. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1655-1665.

17. Tolcher MC, Kalogera E, Hopkins MR, et al. Safety of culdotomy as a surgical approach: implications for natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2012;16:413-420.

18. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 701. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017:129:e155-e159.

19. Ahn KH, Song JY, Kim SH, et al. Transvaginal single-port natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for benign uterine adnexal pathologies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:631-635.

20. Liu J, Kohn J, Sun B, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery sacrocolpopexy: tips and tricks. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:38-39.

21. Liu J, Kohn J, Fu H, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for sacrocolpopexy: a pilot study of 26 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:748-753.

22. Su H, Yen CF, Wu KY, et al. Hysterectomy via transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): feasibility of an innovative approach. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;51:217-221.

23. Lee CL, Huang CY, Wu KY, et al. Natural orifice transvaginal endoscopic surgery myomectomy: an innovative approach to myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:127-130.

24. Chen Y, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Transvaginal single-port laparoscopy sacrocolpopexy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:585- 588.

25. Lee CL, Wu KY, Tsao FY, et al. Natural orifice transvaginal endoscopic surgery for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:89-92.

26. Leblanc E, Narducci F, Bresson L, et al. Fluorescence-assisted sentinel (SND) and pelvic node dissections by single-port transvaginal laparoscopic surgery, for the management of an endometrial carcinoma (EC) in an elderly obese patient. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:686-687.

27. Lee CL, Wu KY, Su H, et al. Robot-assisted natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for hysterectomy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:761-765.

28. Rezai S, Giovane RA, Johnson SN, et al. Robotic natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (R-NOTES) in gynecologic surgeries, a case report and review of literature. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2019;10:287-289.

29. Wang CJ, Wu PY, Kuo HH, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery-assisted versus laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy (NAOC vs. LOC): a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1227-1234.

Through the years, the surgical approach to hysterectomy has expanded from its early beginnings of being performed only through an abdominal or transvaginal route with traditional surgical clamps and suture. The late 1980s saw the advent of the laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH), and from that point forward several additional hysterectomy methods evolved, including today’s robotic approaches.

Although clinical evidence and societal endorsements support vaginal hysterectomy as a superior high-value modality, it remains one of the least performed among all available routes.1-3 In an analysis of inpatient hysterectomies published by Wright and colleagues in 2013, 16.7% of hysterectomies were performed vaginally, a number that essentially has remained steady throughout the ensuing years.4

Attempts to improve the application of vaginal hysterectomy have been made.5 These include the development of various curriculum and simulation-based medical education programs on vaginal surgical skills training and acquisition in the hopes of improving utilization.6 An interesting recent development is the rethinking of vaginal hysterectomy by several surgeons globally who are applying facets of the various hysterectomy methods to a transvaginal approach known as vaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (vNOTES).7,8 Unique to this thinking is the incorporation of conventional laparoscopic instrumentation.

Although I have not yet incorporated this approach in my surgical armamentarium at Columbia University Medical Center/New York–Presbyterian Hospital, I am intrigued by the possibility that this technique may serve as a rescue for vaginal hysterectomies that are at risk of conversion or of not being performed at all.9

At this time, vNOTES is not a standard of care and should be performed only by highly specialized surgeons. However, in the spirit of this Update on minimally invasive surgery and to keep our readers abreast of burgeoning techniques, I am delighted to bring you this overview by Dr. Xiaoming Guan, one of the pioneers of this surgical approach, and Dr. Tamisa Koythong and Dr. Juan Liu. I hope you find this recent development in hysterectomy of interest.

—Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Continue to: Development and evolution of NOTES...

Development and evolution of NOTES

Over the past few decades, emphasis has shifted from laparotomy to minimally invasive surgery because of its proven significant advantages in patient care, such as improved cosmesis, shorter hospital stay, shorter postoperative recovery, and decreased postoperative pain and blood loss.10 Advances in laparoendoscopic surgery and instrumentation, including robot-assisted laparoscopy (RAL), single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), and most recently natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES), reflect ongoing innovative developments in the field of minimally invasive surgery.

Here, we provide a brief literature review of the NOTES technique, focus on its application in gynecologic surgery, and describe how we perform NOTES at our institution.

NOTES application in gynecology

With NOTES, peritoneal access is gained through a natural orifice (such as the mouth, vagina, urethra, or anus) to perform endoscopic surgery, occasionally without requiring an abdominal incision. First described in 2004, transgastric peritoneoscopy was performed in a porcine model, and shortly thereafter the first transgastric appendectomy was performed in humans.11,12 The technique has further been adopted in cholecystectomy, appendectomy, gastrectomy, and nephrectomy procedures.13

Given rapid interest in a possible paradigm shift in the field of minimally invasive surgery, the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortiumfor Assessment and Research (NOSCAR) was formed, and the group published an article on potential barriers to accepted practice and adoption of NOTES as a realistic alternative to traditional laparoscopic surgery.14

While transgastric and transanal access to the peritoneum were initially more popular, the risk of anastomotic leaks associated with incomplete closure and subsequent infection were thought to be prohibitively high.15 Transvaginal access was considered a safer and simpler alternative, allowing for complete closure without increased risk of infection, and this is now the route through which the majority of NOTES procedures are completed.16,17

The eventual application of NOTES in the field of gynecology seemed inevitable. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that transvaginal surgery is the most minimally invasive and preferred surgical route in the management of patients with benign gynecologic diseases.18 However, performing it can be challenging at times due to limited visualization and lack of the required skills for single-site surgery. NOTES allows a gynecologic surgeon to improve visualization through the use of laparoendoscopic instruments and to complete surgery through a transvaginal route.

In 2012, Ahn and colleagues demonstrated the feasibility of the NOTES technique in gynecologic surgery after using it to successfully complete benign adnexal surgery in 10 patients.19 Vaginal NOTES (vNOTES) has since been further developed to include successful hysterectomy, myomectomy, sacrocolpopexy, tubal anastomosis, and even lymphadenectomy in the treatment of early- stage endometrial carcinoma.20-26 vNOTES also can be considered a rescue approach for traditional vaginal hysterectomy in instances in which it is necessary to evaluate adnexal pathology.9 Most recently, vNOTES hysterectomy has been reported with da Vinci Si or Xi robotic platforms.27,28

Continue to: Operative time, post-op stay shorter in NAOC-treated patients...

Operative time, post-op stay shorter in NAOC-treated patients

Few studies have compared outcomes with vNOTES to those with traditional laparoscopy. In 2016, Wang and colleagues compared surgical outcomes between NOTES-assisted ovarian cystectomy (NAOC) and laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy (LOC) in a case-matched study that included 277 patients.29 Although mean (SD) blood loss in patients who underwent LOC was significantly less compared with those who underwent NAOC (21.4 [14.7] mL vs 31.6 [24.1] mL; P = .028), absolute blood loss in both groups was deemed minimal. Additionally, mean (SD) operative time and postoperative stay were significantly less in patients undergoing NAOC compared with those having LOC (38.23 [10.19] minutes vs 53.82 [18.61] minutes; P≤.001; and 1.38 [0.55] days vs 1.82 [0.52] days; P≤.001; respectively).29

How vNOTES hysterectomy stacked up against TLH

In 2018, Baekelandt and colleagues compared outcomes between vNOTES hysterectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) in a noninferiority single-blinded trial of 70 women.8 Compared with TLH, vNOTES hysterectomy was associated with shorter operative time (41 vs 75 minutes; P<.001), shorter hospital stay (0.8 vs 1.3 days; P = .004), and lower postoperative analgesic requirement (8 vs 14 U; P = .006). Additionally, there were no differences between the 2 groups in postoperative infection rate, intraoperative complications, or hospital readmissions within 6 weeks.8

Clearly, vNOTES is the next exciting development in minimally invasive surgery, improving patient outcomes and satisfaction with truly scarless surgery. Compared with traditional transvaginal surgery, vNOTES has the advantage of improved visualization with laparoendoscopic guidance, and it may be beneficial even for patients previously thought to have relative contraindications to successful completion of transvaginal surgery, such as nulliparity or a narrow introitus.

Approach for performing vNOTES procedures

At our institution, Baylor College of Medicine, the majority of gynecologic surgeries are performed via either transumbilical robot-assisted single-incision laparoscopy or vNOTES. Preoperative selection of appropriate candidates for vNOTES includes:

- low suspicion for or prior diagnosis of endometriosis with obliteration of the posterior cul-de-sac

- no surgical history suggestive of severe adhesive disease, and

- adequate vaginal sidewall access and sufficient descent for instrumentation for entry into the peritoneal cavity.

In general, a key concept in vNOTES is "vaginal pull, laparoscopic push," which means that the surgeon must pull the cervix while performing vaginal entry and then push the uterus back in the peritoneal cavity to increase surgical space during laparoscopic surgery.

Continue to: Overview of vNOTES steps...

Overview of vNOTES steps

Below we break down a description of vNOTES in 6 sections. Our patients are always placed in dorsal lithotomy position with TrenGuard (D.A. Surgical) Trendelenburg restraint. We prep the abdomen in case we need to convert to transabdominal surgery via transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic surgery or traditional laparoscopic surgery.

1. Vaginal entry

Accessing the peritoneal cavity through the vagina initially proceeds like a vaginal hysterectomy. We inject dilute vasopressin (20 U in 20 mL of normal saline) circumferentially in the cervix (for hysterectomy) or in the posterior cervix in the cervicovaginal junction (for adnexal surgery without hysterectomy) for vasoconstriction and hydrodissection.

We then incise the vaginal mucosa circumferentially with electrosurgical cautery and follow with posterior colpotomy. We find that reapproximating the posterior peritoneum to the posterior vagina with either figure-of-8 stitches or a running stitch of polyglactin 910 suture (2-0 Vicryl) assists in port placement, bleeding at the peritoneal edge, and closure of the cuff or colpotomy at the end of the case. We tag this suture with a curved hemostat.

Depending on whether a hysterectomy is being performed, anterior colpotomy is made. Again, the anterior peritoneum is then tagged to the anterior vaginal cuff in similar fashion, and this suture is tagged with a different instrument; we typically use a straight hemostat or Sarot clamp (FIGURE 1).

2. Traditional vaginal hysterectomy

After colpotomy, we prefer to perform progressive clamping of the broad ligament from the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments to the level of uterine artery as in traditional vaginal hysterectomy, if feasible.

3. Single-site port placement

The assembled GelPOINT Mini advanced access platform (Applied Medical) (FIGURE 2) is introduced through the vagina after the Alexis wound protector (included with the kit) is first placed through the colpotomy with assistance of Babcock clamps (FIGURE 3).

After ensuring that the green rigid ring of the Alexis wound protector is contained and completely expanded within the peritoneal cavity, we cross our previously tagged sutures as we find this helps with preventing the GelPOINT Mini access platform from inadvertently shifting out of the peritoneal cavity during surgery. The GelSeal cap is then secured and pneumoperitoneum is established (FIGURE 4).

Continue to: 4. Laparoendoscopic surgery...

4. Laparoendoscopic surgery

Instruments used in our surgeries include a 10-mm rigid 30° 43-cm working length laparoscope; a 44-cm LigaSure device (Medtronic); a 5-mm, 37-cm laparoscopic cobra grasping forceps and fenestrated grasper (Karl Storz); and a 5-mm, 45-cm laparoscopic suction with hydrodissection tip (Stryker) (FIGURE 5).

vNOTES allows a gynecologic surgeon the unique ability to survey the upper abdomen. The remainder of the surgery proceeds using basic laparoscopic single-site skills.

During vNOTES, as with all single-site surgical procedures, understanding the optimal placement of crossed instruments is important for successful completion. For example, when securing the right uterine artery, the surgeon needs to push the cervix toward the patient's left and slightly into the peritoneal cavity using a laparoscopic cobra grasper with his or her left hand while then securing the uterine pedicle using the LigaSure device with his or her right hand. This is then reversed when securing the left uterine artery, where the assistant surgeon pushes the cervix toward the patient's right while the surgeon secures the pedicle ("vaginal pull, laparoscopic push") (FIGURE 6).

This again is reiterated in securing the ovarian pedicles, which are pushed into the peritoneal cavity while being secured with the LigaSure device.

5. Specimen removal

For large uteri or specimens that need morcellation, a 15-mm Endo Catch specimen retrieval bag (Medtronic) is introduced through the GelPOINT Mini system. The specimen is then placed in the bag and delivered to the vagina, where contained bag morcellation is performed in standard fashion (FIGURES 7 AND 8). We utilized the "big C" technique by first grasping the specimen with a penetrating clamp. The clamp is then held in our nondominant hand and a No. 10 blade scalpel is used to create a reverse c-incision, keeping one surface of the specimen intact. This is continued until the specimen can be completely delivered through the vagina.

Specimens that do not require morcellation can be grasped laparoscopically, brought to the GelPOINT Mini port, which is quickly disassembled, and delivered. The GelSeal cap is then reassembled.

6. Vaginal cuff closure

The colpotomy or vaginal cuff is closed with barbed suture continuously, as in traditional vaginal hysterectomy cuff closure. Uterosacral ligament suspension should be performed for vaginal cuff support.

vNOTES is the most recent innovative development in the field of minimally invasive surgery, and it has demonstrated feasibility and safety in the fields of general surgery, urology, and gynecology. Adopting vNOTES in clinical practice can improve patient satisfaction and cosmesis as well as surgical outcomes. Gynecologic surgeons can think of vNOTES hysterectomy as "placing an eye" in the vagina while performing transvaginal hysterectomy. The surgical principle of "vaginal pull, laparoscopic push" facilitates the learning process.

Through the years, the surgical approach to hysterectomy has expanded from its early beginnings of being performed only through an abdominal or transvaginal route with traditional surgical clamps and suture. The late 1980s saw the advent of the laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH), and from that point forward several additional hysterectomy methods evolved, including today’s robotic approaches.

Although clinical evidence and societal endorsements support vaginal hysterectomy as a superior high-value modality, it remains one of the least performed among all available routes.1-3 In an analysis of inpatient hysterectomies published by Wright and colleagues in 2013, 16.7% of hysterectomies were performed vaginally, a number that essentially has remained steady throughout the ensuing years.4

Attempts to improve the application of vaginal hysterectomy have been made.5 These include the development of various curriculum and simulation-based medical education programs on vaginal surgical skills training and acquisition in the hopes of improving utilization.6 An interesting recent development is the rethinking of vaginal hysterectomy by several surgeons globally who are applying facets of the various hysterectomy methods to a transvaginal approach known as vaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (vNOTES).7,8 Unique to this thinking is the incorporation of conventional laparoscopic instrumentation.

Although I have not yet incorporated this approach in my surgical armamentarium at Columbia University Medical Center/New York–Presbyterian Hospital, I am intrigued by the possibility that this technique may serve as a rescue for vaginal hysterectomies that are at risk of conversion or of not being performed at all.9

At this time, vNOTES is not a standard of care and should be performed only by highly specialized surgeons. However, in the spirit of this Update on minimally invasive surgery and to keep our readers abreast of burgeoning techniques, I am delighted to bring you this overview by Dr. Xiaoming Guan, one of the pioneers of this surgical approach, and Dr. Tamisa Koythong and Dr. Juan Liu. I hope you find this recent development in hysterectomy of interest.

—Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Continue to: Development and evolution of NOTES...

Development and evolution of NOTES

Over the past few decades, emphasis has shifted from laparotomy to minimally invasive surgery because of its proven significant advantages in patient care, such as improved cosmesis, shorter hospital stay, shorter postoperative recovery, and decreased postoperative pain and blood loss.10 Advances in laparoendoscopic surgery and instrumentation, including robot-assisted laparoscopy (RAL), single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), and most recently natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES), reflect ongoing innovative developments in the field of minimally invasive surgery.

Here, we provide a brief literature review of the NOTES technique, focus on its application in gynecologic surgery, and describe how we perform NOTES at our institution.

NOTES application in gynecology

With NOTES, peritoneal access is gained through a natural orifice (such as the mouth, vagina, urethra, or anus) to perform endoscopic surgery, occasionally without requiring an abdominal incision. First described in 2004, transgastric peritoneoscopy was performed in a porcine model, and shortly thereafter the first transgastric appendectomy was performed in humans.11,12 The technique has further been adopted in cholecystectomy, appendectomy, gastrectomy, and nephrectomy procedures.13

Given rapid interest in a possible paradigm shift in the field of minimally invasive surgery, the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortiumfor Assessment and Research (NOSCAR) was formed, and the group published an article on potential barriers to accepted practice and adoption of NOTES as a realistic alternative to traditional laparoscopic surgery.14

While transgastric and transanal access to the peritoneum were initially more popular, the risk of anastomotic leaks associated with incomplete closure and subsequent infection were thought to be prohibitively high.15 Transvaginal access was considered a safer and simpler alternative, allowing for complete closure without increased risk of infection, and this is now the route through which the majority of NOTES procedures are completed.16,17

The eventual application of NOTES in the field of gynecology seemed inevitable. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that transvaginal surgery is the most minimally invasive and preferred surgical route in the management of patients with benign gynecologic diseases.18 However, performing it can be challenging at times due to limited visualization and lack of the required skills for single-site surgery. NOTES allows a gynecologic surgeon to improve visualization through the use of laparoendoscopic instruments and to complete surgery through a transvaginal route.

In 2012, Ahn and colleagues demonstrated the feasibility of the NOTES technique in gynecologic surgery after using it to successfully complete benign adnexal surgery in 10 patients.19 Vaginal NOTES (vNOTES) has since been further developed to include successful hysterectomy, myomectomy, sacrocolpopexy, tubal anastomosis, and even lymphadenectomy in the treatment of early- stage endometrial carcinoma.20-26 vNOTES also can be considered a rescue approach for traditional vaginal hysterectomy in instances in which it is necessary to evaluate adnexal pathology.9 Most recently, vNOTES hysterectomy has been reported with da Vinci Si or Xi robotic platforms.27,28

Continue to: Operative time, post-op stay shorter in NAOC-treated patients...

Operative time, post-op stay shorter in NAOC-treated patients

Few studies have compared outcomes with vNOTES to those with traditional laparoscopy. In 2016, Wang and colleagues compared surgical outcomes between NOTES-assisted ovarian cystectomy (NAOC) and laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy (LOC) in a case-matched study that included 277 patients.29 Although mean (SD) blood loss in patients who underwent LOC was significantly less compared with those who underwent NAOC (21.4 [14.7] mL vs 31.6 [24.1] mL; P = .028), absolute blood loss in both groups was deemed minimal. Additionally, mean (SD) operative time and postoperative stay were significantly less in patients undergoing NAOC compared with those having LOC (38.23 [10.19] minutes vs 53.82 [18.61] minutes; P≤.001; and 1.38 [0.55] days vs 1.82 [0.52] days; P≤.001; respectively).29

How vNOTES hysterectomy stacked up against TLH

In 2018, Baekelandt and colleagues compared outcomes between vNOTES hysterectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) in a noninferiority single-blinded trial of 70 women.8 Compared with TLH, vNOTES hysterectomy was associated with shorter operative time (41 vs 75 minutes; P<.001), shorter hospital stay (0.8 vs 1.3 days; P = .004), and lower postoperative analgesic requirement (8 vs 14 U; P = .006). Additionally, there were no differences between the 2 groups in postoperative infection rate, intraoperative complications, or hospital readmissions within 6 weeks.8

Clearly, vNOTES is the next exciting development in minimally invasive surgery, improving patient outcomes and satisfaction with truly scarless surgery. Compared with traditional transvaginal surgery, vNOTES has the advantage of improved visualization with laparoendoscopic guidance, and it may be beneficial even for patients previously thought to have relative contraindications to successful completion of transvaginal surgery, such as nulliparity or a narrow introitus.

Approach for performing vNOTES procedures

At our institution, Baylor College of Medicine, the majority of gynecologic surgeries are performed via either transumbilical robot-assisted single-incision laparoscopy or vNOTES. Preoperative selection of appropriate candidates for vNOTES includes:

- low suspicion for or prior diagnosis of endometriosis with obliteration of the posterior cul-de-sac

- no surgical history suggestive of severe adhesive disease, and

- adequate vaginal sidewall access and sufficient descent for instrumentation for entry into the peritoneal cavity.

In general, a key concept in vNOTES is "vaginal pull, laparoscopic push," which means that the surgeon must pull the cervix while performing vaginal entry and then push the uterus back in the peritoneal cavity to increase surgical space during laparoscopic surgery.

Continue to: Overview of vNOTES steps...

Overview of vNOTES steps

Below we break down a description of vNOTES in 6 sections. Our patients are always placed in dorsal lithotomy position with TrenGuard (D.A. Surgical) Trendelenburg restraint. We prep the abdomen in case we need to convert to transabdominal surgery via transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic surgery or traditional laparoscopic surgery.

1. Vaginal entry

Accessing the peritoneal cavity through the vagina initially proceeds like a vaginal hysterectomy. We inject dilute vasopressin (20 U in 20 mL of normal saline) circumferentially in the cervix (for hysterectomy) or in the posterior cervix in the cervicovaginal junction (for adnexal surgery without hysterectomy) for vasoconstriction and hydrodissection.

We then incise the vaginal mucosa circumferentially with electrosurgical cautery and follow with posterior colpotomy. We find that reapproximating the posterior peritoneum to the posterior vagina with either figure-of-8 stitches or a running stitch of polyglactin 910 suture (2-0 Vicryl) assists in port placement, bleeding at the peritoneal edge, and closure of the cuff or colpotomy at the end of the case. We tag this suture with a curved hemostat.

Depending on whether a hysterectomy is being performed, anterior colpotomy is made. Again, the anterior peritoneum is then tagged to the anterior vaginal cuff in similar fashion, and this suture is tagged with a different instrument; we typically use a straight hemostat or Sarot clamp (FIGURE 1).

2. Traditional vaginal hysterectomy

After colpotomy, we prefer to perform progressive clamping of the broad ligament from the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments to the level of uterine artery as in traditional vaginal hysterectomy, if feasible.

3. Single-site port placement

The assembled GelPOINT Mini advanced access platform (Applied Medical) (FIGURE 2) is introduced through the vagina after the Alexis wound protector (included with the kit) is first placed through the colpotomy with assistance of Babcock clamps (FIGURE 3).

After ensuring that the green rigid ring of the Alexis wound protector is contained and completely expanded within the peritoneal cavity, we cross our previously tagged sutures as we find this helps with preventing the GelPOINT Mini access platform from inadvertently shifting out of the peritoneal cavity during surgery. The GelSeal cap is then secured and pneumoperitoneum is established (FIGURE 4).

Continue to: 4. Laparoendoscopic surgery...

4. Laparoendoscopic surgery

Instruments used in our surgeries include a 10-mm rigid 30° 43-cm working length laparoscope; a 44-cm LigaSure device (Medtronic); a 5-mm, 37-cm laparoscopic cobra grasping forceps and fenestrated grasper (Karl Storz); and a 5-mm, 45-cm laparoscopic suction with hydrodissection tip (Stryker) (FIGURE 5).

vNOTES allows a gynecologic surgeon the unique ability to survey the upper abdomen. The remainder of the surgery proceeds using basic laparoscopic single-site skills.

During vNOTES, as with all single-site surgical procedures, understanding the optimal placement of crossed instruments is important for successful completion. For example, when securing the right uterine artery, the surgeon needs to push the cervix toward the patient's left and slightly into the peritoneal cavity using a laparoscopic cobra grasper with his or her left hand while then securing the uterine pedicle using the LigaSure device with his or her right hand. This is then reversed when securing the left uterine artery, where the assistant surgeon pushes the cervix toward the patient's right while the surgeon secures the pedicle ("vaginal pull, laparoscopic push") (FIGURE 6).

This again is reiterated in securing the ovarian pedicles, which are pushed into the peritoneal cavity while being secured with the LigaSure device.

5. Specimen removal

For large uteri or specimens that need morcellation, a 15-mm Endo Catch specimen retrieval bag (Medtronic) is introduced through the GelPOINT Mini system. The specimen is then placed in the bag and delivered to the vagina, where contained bag morcellation is performed in standard fashion (FIGURES 7 AND 8). We utilized the "big C" technique by first grasping the specimen with a penetrating clamp. The clamp is then held in our nondominant hand and a No. 10 blade scalpel is used to create a reverse c-incision, keeping one surface of the specimen intact. This is continued until the specimen can be completely delivered through the vagina.

Specimens that do not require morcellation can be grasped laparoscopically, brought to the GelPOINT Mini port, which is quickly disassembled, and delivered. The GelSeal cap is then reassembled.

6. Vaginal cuff closure

The colpotomy or vaginal cuff is closed with barbed suture continuously, as in traditional vaginal hysterectomy cuff closure. Uterosacral ligament suspension should be performed for vaginal cuff support.

vNOTES is the most recent innovative development in the field of minimally invasive surgery, and it has demonstrated feasibility and safety in the fields of general surgery, urology, and gynecology. Adopting vNOTES in clinical practice can improve patient satisfaction and cosmesis as well as surgical outcomes. Gynecologic surgeons can think of vNOTES hysterectomy as "placing an eye" in the vagina while performing transvaginal hysterectomy. The surgical principle of "vaginal pull, laparoscopic push" facilitates the learning process.

1. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 444. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-1158.

2. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3.

3. Whiteside JL, Kaeser CT, Ridgeway B. Achieving high value in the surgical approach to hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:242-245.

4. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233-241.

5. Moen M, Walter A, Harmanli O, et al. Considerations to improve the evidence-based use of vaginal hysterectomy in benign gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:585-588.

6. Balgobin S, Owens DM, Florian-Rodriguez ME, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy suturing skills training model and curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:553-558.

7. Baekelandt J. Total vaginal NOTES hysterectomy: a new approach to hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1088-1094.

8. Baekelandt JF, De Mulder PA, Le Roy I, et al. Hysterectomy by transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery versus laparoscopy as a day-care procedure: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2019;126:105-113.

9. Guan X, Bardawil E, Liu J, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery as a rescue for total vaginal hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:1135-1136.

10. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD003677.

11. Kalloo AN, Singh VK, Jagannath SB, et al. Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: a novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:114-117.

12. Reddy N, Rao P. Per oral transgastric endoscopic appendectomy in human. Paper Presented at: 45th Annual Conference of the Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy of India; February 28-29, 2004; Jaipur, India.

13. Clark MP, Qayed ES, Kooby DA, et al. Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery in humans: a review. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;189296.

14. Rattner D, Kalloo A; ASGE/SAGES Working Group. ASGE/ SAGES Working Group on natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery, October 2005. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:329-333.

15. Autorino R, Yakoubi R, White WM, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): where are we going? A bibliometric assessment. BJU Int. 2013;111:11-16.

16. Santos BF, Hungness ES. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: progress in humans since the white paper. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1655-1665.

17. Tolcher MC, Kalogera E, Hopkins MR, et al. Safety of culdotomy as a surgical approach: implications for natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2012;16:413-420.

18. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 701. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017:129:e155-e159.

19. Ahn KH, Song JY, Kim SH, et al. Transvaginal single-port natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for benign uterine adnexal pathologies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:631-635.

20. Liu J, Kohn J, Sun B, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery sacrocolpopexy: tips and tricks. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:38-39.

21. Liu J, Kohn J, Fu H, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for sacrocolpopexy: a pilot study of 26 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:748-753.

22. Su H, Yen CF, Wu KY, et al. Hysterectomy via transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): feasibility of an innovative approach. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;51:217-221.

23. Lee CL, Huang CY, Wu KY, et al. Natural orifice transvaginal endoscopic surgery myomectomy: an innovative approach to myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:127-130.

24. Chen Y, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Transvaginal single-port laparoscopy sacrocolpopexy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:585- 588.

25. Lee CL, Wu KY, Tsao FY, et al. Natural orifice transvaginal endoscopic surgery for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:89-92.

26. Leblanc E, Narducci F, Bresson L, et al. Fluorescence-assisted sentinel (SND) and pelvic node dissections by single-port transvaginal laparoscopic surgery, for the management of an endometrial carcinoma (EC) in an elderly obese patient. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:686-687.

27. Lee CL, Wu KY, Su H, et al. Robot-assisted natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for hysterectomy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:761-765.

28. Rezai S, Giovane RA, Johnson SN, et al. Robotic natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (R-NOTES) in gynecologic surgeries, a case report and review of literature. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2019;10:287-289.

29. Wang CJ, Wu PY, Kuo HH, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery-assisted versus laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy (NAOC vs. LOC): a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1227-1234.

1. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 444. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-1158.

2. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3.

3. Whiteside JL, Kaeser CT, Ridgeway B. Achieving high value in the surgical approach to hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:242-245.

4. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233-241.

5. Moen M, Walter A, Harmanli O, et al. Considerations to improve the evidence-based use of vaginal hysterectomy in benign gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:585-588.

6. Balgobin S, Owens DM, Florian-Rodriguez ME, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy suturing skills training model and curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:553-558.

7. Baekelandt J. Total vaginal NOTES hysterectomy: a new approach to hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1088-1094.

8. Baekelandt JF, De Mulder PA, Le Roy I, et al. Hysterectomy by transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery versus laparoscopy as a day-care procedure: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2019;126:105-113.

9. Guan X, Bardawil E, Liu J, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery as a rescue for total vaginal hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:1135-1136.

10. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD003677.

11. Kalloo AN, Singh VK, Jagannath SB, et al. Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: a novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:114-117.

12. Reddy N, Rao P. Per oral transgastric endoscopic appendectomy in human. Paper Presented at: 45th Annual Conference of the Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy of India; February 28-29, 2004; Jaipur, India.

13. Clark MP, Qayed ES, Kooby DA, et al. Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery in humans: a review. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;189296.

14. Rattner D, Kalloo A; ASGE/SAGES Working Group. ASGE/ SAGES Working Group on natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery, October 2005. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:329-333.

15. Autorino R, Yakoubi R, White WM, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): where are we going? A bibliometric assessment. BJU Int. 2013;111:11-16.

16. Santos BF, Hungness ES. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: progress in humans since the white paper. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1655-1665.

17. Tolcher MC, Kalogera E, Hopkins MR, et al. Safety of culdotomy as a surgical approach: implications for natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2012;16:413-420.

18. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 701. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017:129:e155-e159.

19. Ahn KH, Song JY, Kim SH, et al. Transvaginal single-port natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for benign uterine adnexal pathologies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:631-635.

20. Liu J, Kohn J, Sun B, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery sacrocolpopexy: tips and tricks. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:38-39.

21. Liu J, Kohn J, Fu H, et al. Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for sacrocolpopexy: a pilot study of 26 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:748-753.

22. Su H, Yen CF, Wu KY, et al. Hysterectomy via transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): feasibility of an innovative approach. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;51:217-221.

23. Lee CL, Huang CY, Wu KY, et al. Natural orifice transvaginal endoscopic surgery myomectomy: an innovative approach to myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:127-130.

24. Chen Y, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Transvaginal single-port laparoscopy sacrocolpopexy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:585- 588.

25. Lee CL, Wu KY, Tsao FY, et al. Natural orifice transvaginal endoscopic surgery for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:89-92.

26. Leblanc E, Narducci F, Bresson L, et al. Fluorescence-assisted sentinel (SND) and pelvic node dissections by single-port transvaginal laparoscopic surgery, for the management of an endometrial carcinoma (EC) in an elderly obese patient. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:686-687.

27. Lee CL, Wu KY, Su H, et al. Robot-assisted natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery for hysterectomy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:761-765.

28. Rezai S, Giovane RA, Johnson SN, et al. Robotic natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (R-NOTES) in gynecologic surgeries, a case report and review of literature. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2019;10:287-289.

29. Wang CJ, Wu PY, Kuo HH, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery-assisted versus laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy (NAOC vs. LOC): a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1227-1234.

Hysterectomy in patients with history of prior cesarean delivery: A reverse dissection technique for vesicouterine adhesions

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

Creating the “new” space

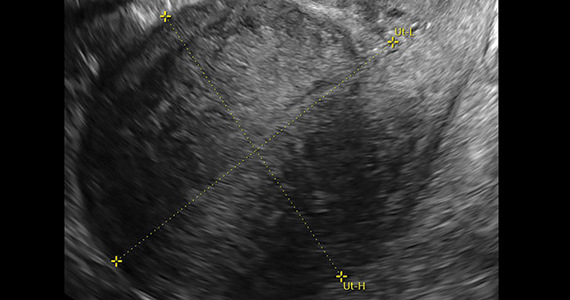

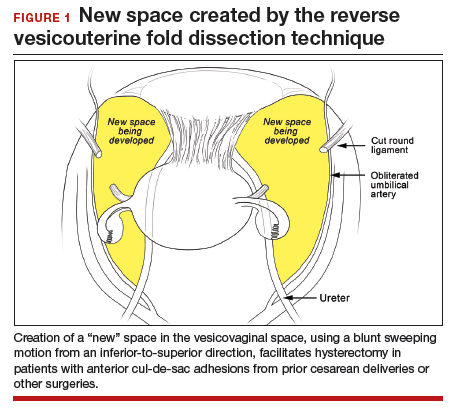

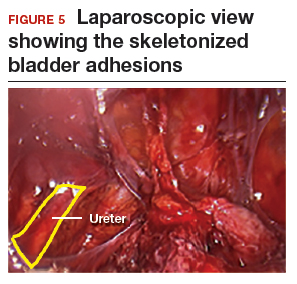

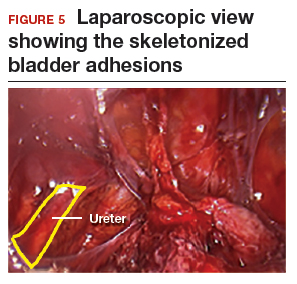

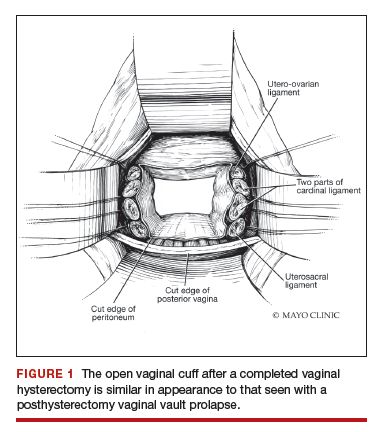

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

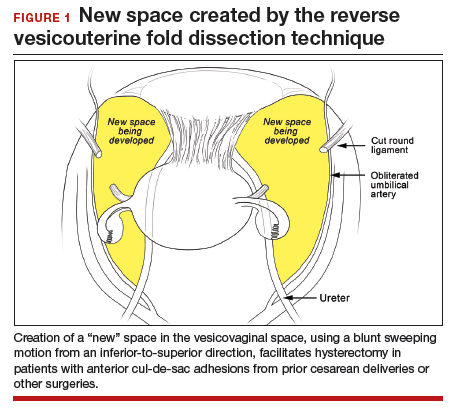

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

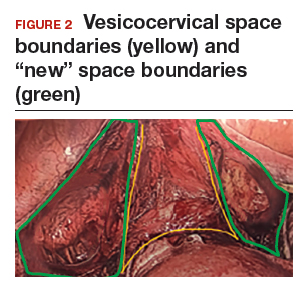

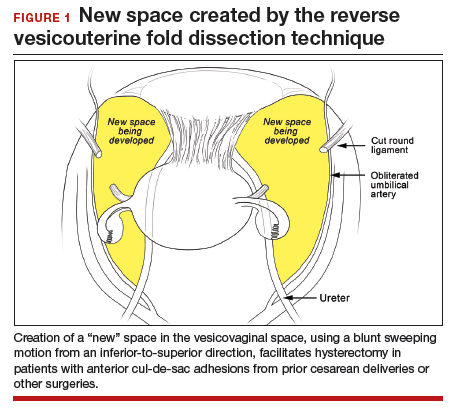

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.

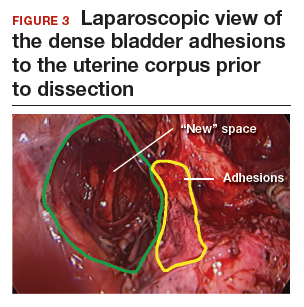

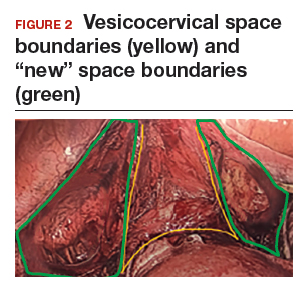

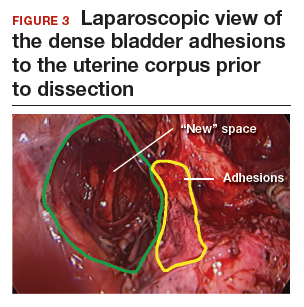

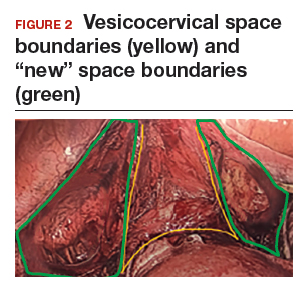

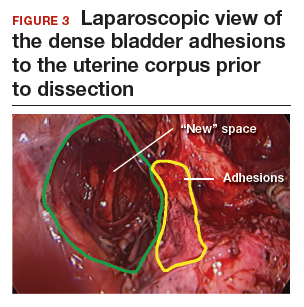

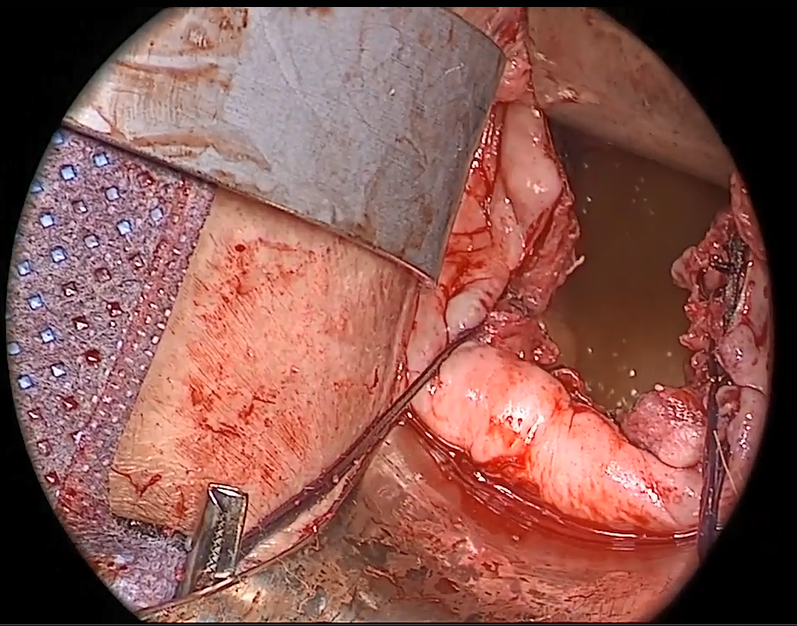

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be performed from this space. Using the previously described blunt sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, the vesicovaginal and vesicocervical space is further developed from an unscarred plane. This will separate the lowest portion of the bladder from the vagina, cervix, and uterus in a safe manner. Similar to the technique performed during a vaginal hysterectomy, this reverse motion of developing the bladder flap avoids erroneous and blind dissection through the vesicouterine adhesions (FIGURES 3–5).

Once the bladder adhesions are well delineated and separated from the uterus by the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique, it is safe to proceed with complete bladder mobilization. Sharp dissection can be used to dissect the remaining scarred bladder at its most superior attachments. Avoid the use of thermal energy to prevent heat injury to the bladder. Carefully dissect the bladder adhesions from the cervicouterine junction. Additional inferior bladder mobilization should be performed up to 3 cm past the leading edge of the cervicovaginal junction to ensure sufficient vaginal tissue for cuff closure. Note that the bladder pillars occasionally may be trapped inside a CD scar. This surgical technique could make it easier to release the pillars from inside the adhesions and penetrating into the scar.15

Continue to: Completing the surgery...

Completing the surgery

Once the bladder is freely mobilized and all adhesions have been dissected, the cervix is circumferentially amputated using monopolar cautery. The vaginal cuff can then be closed from either a laparoscopic or vaginal approach using polyglactin 910 (0-Vicryl) or barbed (V-Loc) suture in a running or interrupted fashion. Our practice uses a 1.5-cm margin depth with each suture. At the end of the surgery, routine cystoscopy is performed to verify distal ureteral patency.16 Postoperatively, we manage these patients using a fast-track, or enhanced recovery, model.17

From the Center for Special Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

https://youtu.be/wgGssnd1JAo

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Case 1: TLH with development of the "new space": The technique with prior C-section

- Case 2: A straightforward case: Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia

- Case 3: History of multiple C-sections with adhesions and fibroids

https://youtu.be/6vHamfPZhdY

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean delivery

An effective technique in challenging situations

Genitourinary injury is a common complication of hysterectomy.18 The proximity of the bladder and ureters to the field of dissection during a hysterectomy can be especially challenging when the anatomy is distorted by adhesion formation from prior surgeries. One study demonstrated a 1.3% incidence of urinary tract injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy.6 This included 0.54% ureteral injuries, 0.71% urinary bladder injuries, and 0.06% combined bladder and ureteral injuries.6 Particularly among patients with a prior CD, the risk of bladder injury can be significantly heightened.18

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique that we described offers multiple benefits. By starting the procedure from an untouched and avascular plane, dissection into the plane of the prior adhesions can be circumvented; thus, bleeding is limited and injury to the bladder and ureters is avoided or minimized. By using blunt and sharp dissection, thermal injury and delayed necrosis can be mitigated. Finally, with bladder mobilization well below the colpotomy site, more adequate vaginal tissue is free to be incorporated into the vaginal cuff closure, thereby limiting the risk of cuff dehiscence.16

While we have found this technique effective for patients with prior cesarean deliveries, it also may be applied to any patient who has a scarred anterior cul-de-sac. This could include patients with prior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect, or endometriosis. Despite the technique being a safeguard against bladder injury, surgeons must still use care in developing the spaces to avoid ureteral injury, especially in a setting of distorted anatomy.

- Page B. Nezhat & the advent of advanced operative video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-179. https://laparoscopy.blogs.com/endoscopyhistory/chapter_22. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Podratz KC. Degrees of freedom: advances in gynecological and obstetric surgery. In: American College of Surgeons. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years, 1913-2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013:113-119. http://endometriosisspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Degrees-of-Freedom-Advances-in-Gynecological-and-Obstetrical-Surgery.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- Kelley WE Jr. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS. 2008;12:351-357.

- Tokunaga T. Video surgery expands its scope. Stanford Med. 1993/1994;11(2)12-16.

- Rooney CM, Crawford AT, Vassallo BJ, et al. Is previous cesarean section a risk for incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy? A case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2041-2044.

- Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Reinsch CS, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and urinary tract injury: experience in a health maintenance organization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1278-1286.

- Sinha R, Sundaram M, Lakhotia S, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women with previous cesarean sections. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:513-517.

- O'Hanlan KA. Cystosufflation to prevent bladder injury. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:195-197.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1-65.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy with DVD, 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Nezhat C, Grace LA, Razavi GM, et al. Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:629-633.

- Nezhat C, Xie J, Aldape D, et al. Use of laparoscopic modified nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for the treatment of extensive endometriosis. Cureus. 2014;6:e159.

- Yabuki Y, Sasaki H, Hatakeyama N, et al. Discrepancies between classic anatomy and modern gynecologic surgery on pelvic connective tissue structure: harmonization of those concepts by collaborative cadaver dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:7-15.

- Uhlenhuth E. Problems in the Anatomy of the Pelvis: An Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1953.

- Nezhat C, Grace, L, Soliemannjad, et al. Cesarean scar defect: what is it and how should it be treated? OBG Manag. 2016;28(4):32,34,36,38-39,53.

- Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:972-985.

- Nezhat C, Main J, Paka C, et al. Advanced gynecologic laparoscopy in a fast-track ambulatory surgery center. JSLS. 2014;18:pii:e2014.00291.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

Creating the “new” space

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.