User login

IBD classification needs an upgrade

The current clinical classification tools for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are suboptimal, and revision beyond the broad categories of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) could improve trial design, research, and ultimately patient outcomes, according to the authors of a recent review.

“Despite clear improvements in our understanding of disease biology and increasing treatment options, we still face an important therapeutic ceiling [in IBD],” wrote Bram Verstockt, MD, of University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium, and colleagues.

“In part, our limited therapeutic successes can be attributed to the disease heterogeneity of IBD: There is not one CD, nor a single UC phenotype,” therefore, a revision of the current systems based on better understanding of IBD is needed, the researchers said.

In a review article published in Gastroenterology, the researchers identified clinical features important to IBD heterogeneity, examined limitations of the current classifications, and proposed improvements.

Characterizing a complex condition

IBD diagnosis is challenging not only because of the overlapping phenotypes, but because other pathologies, including infections, can mimic IBD, the authors noted.

Age of onset should be considered in characterizing IBD, they wrote. Notably, patients with late-onset CD should be distinguished from elderly patients who have had CD for years. The authors cited research showing that “the development of IBD at extremes of age are specific sub-groups that require a different clinical recognition and clinical management,” and that large sample sizes and unbiased statistical methods are needed to define subgroups of IBD patients.

Current CD classification (the Montreal Classification) involves disease location, disease behavior, and age at diagnosis, and considers four phenotypes within disease location: involvement of the ileum, involvement of the colon, involvement of both the ileum and the colon, or isolated upper disease.* “Recently, there has been notable interest in the differential response rates among ileal predominant CD compared to colonic CD,” the authors wrote. Consequently, they proposed a revision of CD classification based on location. Genetic data appear to support this revision. In an IBD genotype-phenotype study including nearly 30,000 patients, three loci (NOD2, MHC, MST1 3p21) were strongly associated with disease location, they said. Other emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may vary according to disease location. The authors identified clinical aspects of CD classification based on disease location that distinguish small bowel predominant CD versus colonic predominant CD. Ileal disease patients have shown an increased risk for undergoing surgery, while those with colonic involvement have an increased risk for developing extraintestinal manifestations.

They also emphasized the value of considering rectal inflammation, which significantly impacts surgical procedures in CD.

Standard UC classification is based on macroscopic disease in the colon at the time of inflammation, the authors said. Although this approach allows for quick assessment of a patient’s risk of colectomy, the authors proposed improvements, including the use of serum biomarkers (C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) to identify patients at highest risk for colectomy and colon cancer based on inflammation. The authors also suggested that patients with refractory proctitis be enrolled in UC clinical trials or in studies focusing on refractory proctitis in particular.

The pelvic pouch has become the most often performed surgical procedure for patients undergoing colectomy, but there is no agreement on classification of inflammatory pelvic pouch disorders, and studies of etiology and treatment are lacking, the authors noted. They advised a clinical assessment based on symptoms, including stool frequency, urgency, and incontinence. They also suggested that afferent limb ulcers of erosions should be classified separately from pouch inflammation.

The authors ended by noting that extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) that occur in up to half of IBD patients may or may not be directly related to intestinal disease, and may represent a different phenotype, and the presence and type of EIM should be included in a revised IBD classification system, they said.

The authors emphasized that continuing to refer to IBD as only CD and UC “does a great disservice to our attempts to better understand IBD pathogenesis and to improve clinical patient management.”

They concluded: “Although revised clinical classification tools alone will not be sufficient and should be complemented by deeper and more detailed study into molecular subclassification of disease, the considerations here could be used as a springboard toward improved trial design, future translational research approaches and better treatment outcomes for patients.”

Review reflects complexity of IBD and challenges of change

The review is important at this time because of the growing recognition that IBD, while traditionally categorized as either UC or CD, is most likely composed of a range of heterogeneous conditions involving inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, Jatin Roper, MD, of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“Evidence that our current classification of IBD is suboptimal comes from both the wide range of clinical phenotypes as well as complexity in genetic markers that are associated with IBD,” he said. “It is well accepted in the gastroenterology community that IBD is a complex condition; so it is surprising to me that the dichotomy of UC vs. Crohn’s disease has rarely been challenged,” said Dr. Roper. “The authors of this review should be commended for raising the question of whether IBD deserves a more nuanced classification system that reflects the growing recognition of the wide heterogeneity of patient presentations and genetics,” he said.

“Challenging medical definitions is inherently difficult because patient diagnoses, treatment plans, as well as decades of clinical research have been based on well-accepted disease categories. Another major challenge in reclassification is that the course of IBD can vary greatly over time in the same patient in severity, range, and complexity, and potentially includes many disease subtypes noted by the authors of this review,” he added. “Therefore, I believe that the current system of dividing IBD in UC and CD is here to stay until subtypes based on mechanisms of disease pathogenesis are discovered.

“Additional research is needed to understand the molecular basis of IBD,” Dr. Roper emphasized. “Recent advances in RNA expression and proteomics at the single cell level may reveal distinct cell types or cell functions in tissues from IBD patients that may help us understand clinical phenotype or response to therapy.”

The study received no outside funding. The authors disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, Biogen, Chiesi, Falk, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, R-Biopharm, Takeda, and Truvion. Dr. Roper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

*Correction, 4/11/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the Montreal Classification.

The current clinical classification tools for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are suboptimal, and revision beyond the broad categories of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) could improve trial design, research, and ultimately patient outcomes, according to the authors of a recent review.

“Despite clear improvements in our understanding of disease biology and increasing treatment options, we still face an important therapeutic ceiling [in IBD],” wrote Bram Verstockt, MD, of University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium, and colleagues.

“In part, our limited therapeutic successes can be attributed to the disease heterogeneity of IBD: There is not one CD, nor a single UC phenotype,” therefore, a revision of the current systems based on better understanding of IBD is needed, the researchers said.

In a review article published in Gastroenterology, the researchers identified clinical features important to IBD heterogeneity, examined limitations of the current classifications, and proposed improvements.

Characterizing a complex condition

IBD diagnosis is challenging not only because of the overlapping phenotypes, but because other pathologies, including infections, can mimic IBD, the authors noted.

Age of onset should be considered in characterizing IBD, they wrote. Notably, patients with late-onset CD should be distinguished from elderly patients who have had CD for years. The authors cited research showing that “the development of IBD at extremes of age are specific sub-groups that require a different clinical recognition and clinical management,” and that large sample sizes and unbiased statistical methods are needed to define subgroups of IBD patients.

Current CD classification (the Montreal Classification) involves disease location, disease behavior, and age at diagnosis, and considers four phenotypes within disease location: involvement of the ileum, involvement of the colon, involvement of both the ileum and the colon, or isolated upper disease.* “Recently, there has been notable interest in the differential response rates among ileal predominant CD compared to colonic CD,” the authors wrote. Consequently, they proposed a revision of CD classification based on location. Genetic data appear to support this revision. In an IBD genotype-phenotype study including nearly 30,000 patients, three loci (NOD2, MHC, MST1 3p21) were strongly associated with disease location, they said. Other emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may vary according to disease location. The authors identified clinical aspects of CD classification based on disease location that distinguish small bowel predominant CD versus colonic predominant CD. Ileal disease patients have shown an increased risk for undergoing surgery, while those with colonic involvement have an increased risk for developing extraintestinal manifestations.

They also emphasized the value of considering rectal inflammation, which significantly impacts surgical procedures in CD.

Standard UC classification is based on macroscopic disease in the colon at the time of inflammation, the authors said. Although this approach allows for quick assessment of a patient’s risk of colectomy, the authors proposed improvements, including the use of serum biomarkers (C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) to identify patients at highest risk for colectomy and colon cancer based on inflammation. The authors also suggested that patients with refractory proctitis be enrolled in UC clinical trials or in studies focusing on refractory proctitis in particular.

The pelvic pouch has become the most often performed surgical procedure for patients undergoing colectomy, but there is no agreement on classification of inflammatory pelvic pouch disorders, and studies of etiology and treatment are lacking, the authors noted. They advised a clinical assessment based on symptoms, including stool frequency, urgency, and incontinence. They also suggested that afferent limb ulcers of erosions should be classified separately from pouch inflammation.

The authors ended by noting that extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) that occur in up to half of IBD patients may or may not be directly related to intestinal disease, and may represent a different phenotype, and the presence and type of EIM should be included in a revised IBD classification system, they said.

The authors emphasized that continuing to refer to IBD as only CD and UC “does a great disservice to our attempts to better understand IBD pathogenesis and to improve clinical patient management.”

They concluded: “Although revised clinical classification tools alone will not be sufficient and should be complemented by deeper and more detailed study into molecular subclassification of disease, the considerations here could be used as a springboard toward improved trial design, future translational research approaches and better treatment outcomes for patients.”

Review reflects complexity of IBD and challenges of change

The review is important at this time because of the growing recognition that IBD, while traditionally categorized as either UC or CD, is most likely composed of a range of heterogeneous conditions involving inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, Jatin Roper, MD, of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“Evidence that our current classification of IBD is suboptimal comes from both the wide range of clinical phenotypes as well as complexity in genetic markers that are associated with IBD,” he said. “It is well accepted in the gastroenterology community that IBD is a complex condition; so it is surprising to me that the dichotomy of UC vs. Crohn’s disease has rarely been challenged,” said Dr. Roper. “The authors of this review should be commended for raising the question of whether IBD deserves a more nuanced classification system that reflects the growing recognition of the wide heterogeneity of patient presentations and genetics,” he said.

“Challenging medical definitions is inherently difficult because patient diagnoses, treatment plans, as well as decades of clinical research have been based on well-accepted disease categories. Another major challenge in reclassification is that the course of IBD can vary greatly over time in the same patient in severity, range, and complexity, and potentially includes many disease subtypes noted by the authors of this review,” he added. “Therefore, I believe that the current system of dividing IBD in UC and CD is here to stay until subtypes based on mechanisms of disease pathogenesis are discovered.

“Additional research is needed to understand the molecular basis of IBD,” Dr. Roper emphasized. “Recent advances in RNA expression and proteomics at the single cell level may reveal distinct cell types or cell functions in tissues from IBD patients that may help us understand clinical phenotype or response to therapy.”

The study received no outside funding. The authors disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, Biogen, Chiesi, Falk, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, R-Biopharm, Takeda, and Truvion. Dr. Roper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

*Correction, 4/11/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the Montreal Classification.

The current clinical classification tools for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are suboptimal, and revision beyond the broad categories of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) could improve trial design, research, and ultimately patient outcomes, according to the authors of a recent review.

“Despite clear improvements in our understanding of disease biology and increasing treatment options, we still face an important therapeutic ceiling [in IBD],” wrote Bram Verstockt, MD, of University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium, and colleagues.

“In part, our limited therapeutic successes can be attributed to the disease heterogeneity of IBD: There is not one CD, nor a single UC phenotype,” therefore, a revision of the current systems based on better understanding of IBD is needed, the researchers said.

In a review article published in Gastroenterology, the researchers identified clinical features important to IBD heterogeneity, examined limitations of the current classifications, and proposed improvements.

Characterizing a complex condition

IBD diagnosis is challenging not only because of the overlapping phenotypes, but because other pathologies, including infections, can mimic IBD, the authors noted.

Age of onset should be considered in characterizing IBD, they wrote. Notably, patients with late-onset CD should be distinguished from elderly patients who have had CD for years. The authors cited research showing that “the development of IBD at extremes of age are specific sub-groups that require a different clinical recognition and clinical management,” and that large sample sizes and unbiased statistical methods are needed to define subgroups of IBD patients.

Current CD classification (the Montreal Classification) involves disease location, disease behavior, and age at diagnosis, and considers four phenotypes within disease location: involvement of the ileum, involvement of the colon, involvement of both the ileum and the colon, or isolated upper disease.* “Recently, there has been notable interest in the differential response rates among ileal predominant CD compared to colonic CD,” the authors wrote. Consequently, they proposed a revision of CD classification based on location. Genetic data appear to support this revision. In an IBD genotype-phenotype study including nearly 30,000 patients, three loci (NOD2, MHC, MST1 3p21) were strongly associated with disease location, they said. Other emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may vary according to disease location. The authors identified clinical aspects of CD classification based on disease location that distinguish small bowel predominant CD versus colonic predominant CD. Ileal disease patients have shown an increased risk for undergoing surgery, while those with colonic involvement have an increased risk for developing extraintestinal manifestations.

They also emphasized the value of considering rectal inflammation, which significantly impacts surgical procedures in CD.

Standard UC classification is based on macroscopic disease in the colon at the time of inflammation, the authors said. Although this approach allows for quick assessment of a patient’s risk of colectomy, the authors proposed improvements, including the use of serum biomarkers (C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) to identify patients at highest risk for colectomy and colon cancer based on inflammation. The authors also suggested that patients with refractory proctitis be enrolled in UC clinical trials or in studies focusing on refractory proctitis in particular.

The pelvic pouch has become the most often performed surgical procedure for patients undergoing colectomy, but there is no agreement on classification of inflammatory pelvic pouch disorders, and studies of etiology and treatment are lacking, the authors noted. They advised a clinical assessment based on symptoms, including stool frequency, urgency, and incontinence. They also suggested that afferent limb ulcers of erosions should be classified separately from pouch inflammation.

The authors ended by noting that extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) that occur in up to half of IBD patients may or may not be directly related to intestinal disease, and may represent a different phenotype, and the presence and type of EIM should be included in a revised IBD classification system, they said.

The authors emphasized that continuing to refer to IBD as only CD and UC “does a great disservice to our attempts to better understand IBD pathogenesis and to improve clinical patient management.”

They concluded: “Although revised clinical classification tools alone will not be sufficient and should be complemented by deeper and more detailed study into molecular subclassification of disease, the considerations here could be used as a springboard toward improved trial design, future translational research approaches and better treatment outcomes for patients.”

Review reflects complexity of IBD and challenges of change

The review is important at this time because of the growing recognition that IBD, while traditionally categorized as either UC or CD, is most likely composed of a range of heterogeneous conditions involving inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, Jatin Roper, MD, of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“Evidence that our current classification of IBD is suboptimal comes from both the wide range of clinical phenotypes as well as complexity in genetic markers that are associated with IBD,” he said. “It is well accepted in the gastroenterology community that IBD is a complex condition; so it is surprising to me that the dichotomy of UC vs. Crohn’s disease has rarely been challenged,” said Dr. Roper. “The authors of this review should be commended for raising the question of whether IBD deserves a more nuanced classification system that reflects the growing recognition of the wide heterogeneity of patient presentations and genetics,” he said.

“Challenging medical definitions is inherently difficult because patient diagnoses, treatment plans, as well as decades of clinical research have been based on well-accepted disease categories. Another major challenge in reclassification is that the course of IBD can vary greatly over time in the same patient in severity, range, and complexity, and potentially includes many disease subtypes noted by the authors of this review,” he added. “Therefore, I believe that the current system of dividing IBD in UC and CD is here to stay until subtypes based on mechanisms of disease pathogenesis are discovered.

“Additional research is needed to understand the molecular basis of IBD,” Dr. Roper emphasized. “Recent advances in RNA expression and proteomics at the single cell level may reveal distinct cell types or cell functions in tissues from IBD patients that may help us understand clinical phenotype or response to therapy.”

The study received no outside funding. The authors disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, Biogen, Chiesi, Falk, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, R-Biopharm, Takeda, and Truvion. Dr. Roper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

*Correction, 4/11/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the Montreal Classification.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

ARFID or reasonable food restriction? The jury is out

Problems with eating and nutrition are common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other gastrointestinal disorders, but clinicians who treat them should be careful not to automatically assume that patients have eating disorders, according to a psychologist who specializes in the psychological and social aspects of chronic digestive diseases.

On the other hand, clinicians must also be aware of the possibility that patients could have a recently identified syndrome cluster called avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), said Tiffany Taft, PsyD, a research associate professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology), medical social sciences, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, Chicago. In a recent study, she and her colleagues defined ARFID as “failure to meet one’s nutritional needs owing to sensory hypersensitivity, lack of interest in eating, or fear of aversive consequences from eating, and is associated with negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.”

ARFID “is a hot topic that we really don’t understand,” she said in an online presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common among patients with IBD, “and nutritional deficiencies themselves can lead to symptoms or side effects that can cause people to eat less,” she said.

“As our vitamin B12 goes down, our cognitive functioning starts to decline, and we might not be making clear decisions in how we’re deciding what to eat, when to eat, if we should be eating at all – just something to think about in your patients who have nutritional deficiencies,” she told the audience.

Other common nutritional deficiencies that can affect eating and food choice among patients with IBD include low folate (B9) levels associated with sore tongue and weight loss, low iron levels leading to nausea and loss of appetite, and zinc deficiency leading to loss of appetite and alterations in taste and/or smell, she said.

Newly recognized in GI

She noted that “ARFID actually originates in the pediatric psychiatric literature, mostly in children with sensory issues [such as] autism spectrum disorder, so this is not a construct that started in digestive disease, but has been adapted and applied to patients with digestive disease, including IBD.”

The DSM-5 lists four criteria for ARFID: significant weight loss, significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral nutrition or oral supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functions.

Helen Burton Murray, PhD, director of the gastrointestinal behavioral health program in the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is familiar with Dr. Taft’s work, said in an interview that inclusion of ARFID in DSM-5 has put a name to a syndrome or symptom cluster that in all likelihood already existed.

However, “the jury is still out about whether, if we do diagnose patients who have digestive diseases with ARFID, that then helps them get to a treatment that improves their relationship with food and improves nutritional issues that may have occurred as a result of a restricted food intake,” she said.

“We don’t know yet if the diagnosis will actually improve things. In our clinical practice, anecdotally, it has, both for patients with IBDs and for patients with other GI conditions, particularly GI functional motility disorders. We’re a little bit more confident about making the diagnosis of ARFID in GI functional motility disorders than we are in IBD of course,” she said.

Screening measures

To get a better sense of the prevalence of ARFID, compared with reasonable responses to digestive diseases, Dr. Taft and colleagues conducted their cross-sectional study in 289 adults with achalasia, celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, or IBD.

They found that 51.3% of the total sample met the diagnostic criteria for ARFID based on the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS), including 75.7 % of patients with achalasia. But Dr. Taft had cautions

“I can tell you, working with achalasia patients, 75% do not have ARFID,” Dr. Taft said.

She noted that the 51.3% of patients with IBD identified by NIAS or the 53% identified by the ARFID+ scale as having ARFID was also highly doubtful.

Dr. Taft and colleagues determined that nearly half of the variance in the NIAS could be accounted for by GI symptoms rather than psychosocial factors, making it less than ideal for use in the clinic or by researchers.

She also noted, however, that she received an email from one of the creators of NIAS, Hana F. Zickgraf, PhD, from the University of South Alabama, Mobile. Dr. Zickgraf agreed that the scale had drawbacks when applied to patients with GI disease, and pointed instead to the Fear of Food Questionnaire, a newly developed 18-item GI disease-specific instrument. Dr. Taft recommended the new questionnaire for research purposes, and expressed hope that a shorter version could be made available for screening patients in clinic.

Dr. Burton Murray said that while the Fear of Food Questionnaire, perhaps in combination with NIAS, has the potential to be a useful screening tool, cutoffs for it have yet to be established.

“At the end of the day, the diagnosis would be made by a clinician who is able to determine whether the life impairment or if the nutritional impairment or restricted food intake are reasonable in the realm of their digestive disease, or could a treatment for ARFID be warranted to help them to make changes to improve their quality of life and nutrition,” she said.

Check biases at the door

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ARFID, clinicians should also consider biases, Dr. Taft said.

“Eating disorders are highly stigmatized and stereotyped diagnoses,” more often attributed to young White women than to either men or to people of racial or ethnic minorities, she said.

Cultural background may contribute to food restrictions, and the risk may increase with age, with 68% of patients with later-onset IBD restricting diets to control the disease. It’s also possible that beliefs about food and “clean and healthy” eating may influence food and eating choices after a patient receives an IBD diagnosis.

Dr. Taft also pointed out that clinicians and patients may have different ideas about what constitutes significant food avoidance. Clinicians may expect patients with IBD to eat despite feeling nauseated, having abdominal pains, or diarrhea, for example, when the same food avoidance might be deemed reasonable in patients with short-term GI infections.

“Severe IBD symptoms are a significant predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and PTSD is hallmarked by avoidance behaviors,” she added.

She emphasized the need for clinicians to ask the right questions of patients to get at the roots of their nutritional deficiency or eating behavior, and to refer patients to mental health professionals with expertise in disordered eating or GI psychology.

Dr. Taft and Dr. Burton Murray reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2022.

Problems with eating and nutrition are common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other gastrointestinal disorders, but clinicians who treat them should be careful not to automatically assume that patients have eating disorders, according to a psychologist who specializes in the psychological and social aspects of chronic digestive diseases.

On the other hand, clinicians must also be aware of the possibility that patients could have a recently identified syndrome cluster called avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), said Tiffany Taft, PsyD, a research associate professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology), medical social sciences, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, Chicago. In a recent study, she and her colleagues defined ARFID as “failure to meet one’s nutritional needs owing to sensory hypersensitivity, lack of interest in eating, or fear of aversive consequences from eating, and is associated with negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.”

ARFID “is a hot topic that we really don’t understand,” she said in an online presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common among patients with IBD, “and nutritional deficiencies themselves can lead to symptoms or side effects that can cause people to eat less,” she said.

“As our vitamin B12 goes down, our cognitive functioning starts to decline, and we might not be making clear decisions in how we’re deciding what to eat, when to eat, if we should be eating at all – just something to think about in your patients who have nutritional deficiencies,” she told the audience.

Other common nutritional deficiencies that can affect eating and food choice among patients with IBD include low folate (B9) levels associated with sore tongue and weight loss, low iron levels leading to nausea and loss of appetite, and zinc deficiency leading to loss of appetite and alterations in taste and/or smell, she said.

Newly recognized in GI

She noted that “ARFID actually originates in the pediatric psychiatric literature, mostly in children with sensory issues [such as] autism spectrum disorder, so this is not a construct that started in digestive disease, but has been adapted and applied to patients with digestive disease, including IBD.”

The DSM-5 lists four criteria for ARFID: significant weight loss, significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral nutrition or oral supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functions.

Helen Burton Murray, PhD, director of the gastrointestinal behavioral health program in the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is familiar with Dr. Taft’s work, said in an interview that inclusion of ARFID in DSM-5 has put a name to a syndrome or symptom cluster that in all likelihood already existed.

However, “the jury is still out about whether, if we do diagnose patients who have digestive diseases with ARFID, that then helps them get to a treatment that improves their relationship with food and improves nutritional issues that may have occurred as a result of a restricted food intake,” she said.

“We don’t know yet if the diagnosis will actually improve things. In our clinical practice, anecdotally, it has, both for patients with IBDs and for patients with other GI conditions, particularly GI functional motility disorders. We’re a little bit more confident about making the diagnosis of ARFID in GI functional motility disorders than we are in IBD of course,” she said.

Screening measures

To get a better sense of the prevalence of ARFID, compared with reasonable responses to digestive diseases, Dr. Taft and colleagues conducted their cross-sectional study in 289 adults with achalasia, celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, or IBD.

They found that 51.3% of the total sample met the diagnostic criteria for ARFID based on the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS), including 75.7 % of patients with achalasia. But Dr. Taft had cautions

“I can tell you, working with achalasia patients, 75% do not have ARFID,” Dr. Taft said.

She noted that the 51.3% of patients with IBD identified by NIAS or the 53% identified by the ARFID+ scale as having ARFID was also highly doubtful.

Dr. Taft and colleagues determined that nearly half of the variance in the NIAS could be accounted for by GI symptoms rather than psychosocial factors, making it less than ideal for use in the clinic or by researchers.

She also noted, however, that she received an email from one of the creators of NIAS, Hana F. Zickgraf, PhD, from the University of South Alabama, Mobile. Dr. Zickgraf agreed that the scale had drawbacks when applied to patients with GI disease, and pointed instead to the Fear of Food Questionnaire, a newly developed 18-item GI disease-specific instrument. Dr. Taft recommended the new questionnaire for research purposes, and expressed hope that a shorter version could be made available for screening patients in clinic.

Dr. Burton Murray said that while the Fear of Food Questionnaire, perhaps in combination with NIAS, has the potential to be a useful screening tool, cutoffs for it have yet to be established.

“At the end of the day, the diagnosis would be made by a clinician who is able to determine whether the life impairment or if the nutritional impairment or restricted food intake are reasonable in the realm of their digestive disease, or could a treatment for ARFID be warranted to help them to make changes to improve their quality of life and nutrition,” she said.

Check biases at the door

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ARFID, clinicians should also consider biases, Dr. Taft said.

“Eating disorders are highly stigmatized and stereotyped diagnoses,” more often attributed to young White women than to either men or to people of racial or ethnic minorities, she said.

Cultural background may contribute to food restrictions, and the risk may increase with age, with 68% of patients with later-onset IBD restricting diets to control the disease. It’s also possible that beliefs about food and “clean and healthy” eating may influence food and eating choices after a patient receives an IBD diagnosis.

Dr. Taft also pointed out that clinicians and patients may have different ideas about what constitutes significant food avoidance. Clinicians may expect patients with IBD to eat despite feeling nauseated, having abdominal pains, or diarrhea, for example, when the same food avoidance might be deemed reasonable in patients with short-term GI infections.

“Severe IBD symptoms are a significant predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and PTSD is hallmarked by avoidance behaviors,” she added.

She emphasized the need for clinicians to ask the right questions of patients to get at the roots of their nutritional deficiency or eating behavior, and to refer patients to mental health professionals with expertise in disordered eating or GI psychology.

Dr. Taft and Dr. Burton Murray reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2022.

Problems with eating and nutrition are common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other gastrointestinal disorders, but clinicians who treat them should be careful not to automatically assume that patients have eating disorders, according to a psychologist who specializes in the psychological and social aspects of chronic digestive diseases.

On the other hand, clinicians must also be aware of the possibility that patients could have a recently identified syndrome cluster called avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), said Tiffany Taft, PsyD, a research associate professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology), medical social sciences, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, Chicago. In a recent study, she and her colleagues defined ARFID as “failure to meet one’s nutritional needs owing to sensory hypersensitivity, lack of interest in eating, or fear of aversive consequences from eating, and is associated with negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.”

ARFID “is a hot topic that we really don’t understand,” she said in an online presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common among patients with IBD, “and nutritional deficiencies themselves can lead to symptoms or side effects that can cause people to eat less,” she said.

“As our vitamin B12 goes down, our cognitive functioning starts to decline, and we might not be making clear decisions in how we’re deciding what to eat, when to eat, if we should be eating at all – just something to think about in your patients who have nutritional deficiencies,” she told the audience.

Other common nutritional deficiencies that can affect eating and food choice among patients with IBD include low folate (B9) levels associated with sore tongue and weight loss, low iron levels leading to nausea and loss of appetite, and zinc deficiency leading to loss of appetite and alterations in taste and/or smell, she said.

Newly recognized in GI

She noted that “ARFID actually originates in the pediatric psychiatric literature, mostly in children with sensory issues [such as] autism spectrum disorder, so this is not a construct that started in digestive disease, but has been adapted and applied to patients with digestive disease, including IBD.”

The DSM-5 lists four criteria for ARFID: significant weight loss, significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral nutrition or oral supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functions.

Helen Burton Murray, PhD, director of the gastrointestinal behavioral health program in the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is familiar with Dr. Taft’s work, said in an interview that inclusion of ARFID in DSM-5 has put a name to a syndrome or symptom cluster that in all likelihood already existed.

However, “the jury is still out about whether, if we do diagnose patients who have digestive diseases with ARFID, that then helps them get to a treatment that improves their relationship with food and improves nutritional issues that may have occurred as a result of a restricted food intake,” she said.

“We don’t know yet if the diagnosis will actually improve things. In our clinical practice, anecdotally, it has, both for patients with IBDs and for patients with other GI conditions, particularly GI functional motility disorders. We’re a little bit more confident about making the diagnosis of ARFID in GI functional motility disorders than we are in IBD of course,” she said.

Screening measures

To get a better sense of the prevalence of ARFID, compared with reasonable responses to digestive diseases, Dr. Taft and colleagues conducted their cross-sectional study in 289 adults with achalasia, celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, or IBD.

They found that 51.3% of the total sample met the diagnostic criteria for ARFID based on the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS), including 75.7 % of patients with achalasia. But Dr. Taft had cautions

“I can tell you, working with achalasia patients, 75% do not have ARFID,” Dr. Taft said.

She noted that the 51.3% of patients with IBD identified by NIAS or the 53% identified by the ARFID+ scale as having ARFID was also highly doubtful.

Dr. Taft and colleagues determined that nearly half of the variance in the NIAS could be accounted for by GI symptoms rather than psychosocial factors, making it less than ideal for use in the clinic or by researchers.

She also noted, however, that she received an email from one of the creators of NIAS, Hana F. Zickgraf, PhD, from the University of South Alabama, Mobile. Dr. Zickgraf agreed that the scale had drawbacks when applied to patients with GI disease, and pointed instead to the Fear of Food Questionnaire, a newly developed 18-item GI disease-specific instrument. Dr. Taft recommended the new questionnaire for research purposes, and expressed hope that a shorter version could be made available for screening patients in clinic.

Dr. Burton Murray said that while the Fear of Food Questionnaire, perhaps in combination with NIAS, has the potential to be a useful screening tool, cutoffs for it have yet to be established.

“At the end of the day, the diagnosis would be made by a clinician who is able to determine whether the life impairment or if the nutritional impairment or restricted food intake are reasonable in the realm of their digestive disease, or could a treatment for ARFID be warranted to help them to make changes to improve their quality of life and nutrition,” she said.

Check biases at the door

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ARFID, clinicians should also consider biases, Dr. Taft said.

“Eating disorders are highly stigmatized and stereotyped diagnoses,” more often attributed to young White women than to either men or to people of racial or ethnic minorities, she said.

Cultural background may contribute to food restrictions, and the risk may increase with age, with 68% of patients with later-onset IBD restricting diets to control the disease. It’s also possible that beliefs about food and “clean and healthy” eating may influence food and eating choices after a patient receives an IBD diagnosis.

Dr. Taft also pointed out that clinicians and patients may have different ideas about what constitutes significant food avoidance. Clinicians may expect patients with IBD to eat despite feeling nauseated, having abdominal pains, or diarrhea, for example, when the same food avoidance might be deemed reasonable in patients with short-term GI infections.

“Severe IBD symptoms are a significant predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and PTSD is hallmarked by avoidance behaviors,” she added.

She emphasized the need for clinicians to ask the right questions of patients to get at the roots of their nutritional deficiency or eating behavior, and to refer patients to mental health professionals with expertise in disordered eating or GI psychology.

Dr. Taft and Dr. Burton Murray reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2022.

FROM CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

The management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incidence is rising globally.1-3 In the United States, we have seen a 123% increase in prevalence of IBD among adults and a 133% increase among children from 2007 to 2016, with an annual percentage change of 9.9%.1 The rise of IBD in young people, and the overall higher prevalence in women compared with men, make pregnancy and IBD a topic of increasing importance for gastroenterologists.1 Here, we will discuss management and expectations in women with IBD before conception, during pregnancy, and post partum.

Preconception

Disease activity

Achieving both clinical and endoscopic remission of disease prior to conception is the key to ensuring the best maternal and fetal outcomes. Patients with IBD who conceive while in remission remain in remission 80% of the time.4,5 On the other hand, those who conceive while their disease is active may continue to have active or worsening disease in nearly 70% of cases.4 Active disease has been associated with an increased incidence of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small-for-gestational-age birth.6-8 Active disease can also exacerbate malnutrition and result in poor maternal weight gain, which is associated with intrauterine growth restriction.9,7 Pregnancy outcomes in patients with IBD and quiescent disease are similar to those in the general population.10,11

Health care maintenance

Optimizing maternal health prior to conception is critical. Alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, and marijuana should all be avoided. Opioids should be tapered off prior to conception, as continued use may result in neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome and long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.12,13 In addition, aiming for a healthy body mass index between 18 and 25 months prior to conception allows for better overall pregnancy outcomes.13 Appropriate cancer screening includes colon cancer screening in those with more than 8 years of colitis, regular pap smear for cervical cancer, and annual total body skin cancer examinations for patients on thiopurines and biologic therapies.14

Nutrition

Folic acid supplementation with at least 400 micrograms (mcg) daily is necessary for all women planning pregnancy. Patients with small bowel involvement or history of small bowel resection should have a folate intake of a minimum of 2 grams per day. Adequate vitamin D levels (at least 20 ng/mL) are recommended in all women with IBD. Those with malabsorption should be screened for deficiencies in vitamin B12, folate, and iron.13 These nutritional markers should be evaluated prepregnancy, during the first trimester, and thereafter as needed.15-18

Preconception counseling

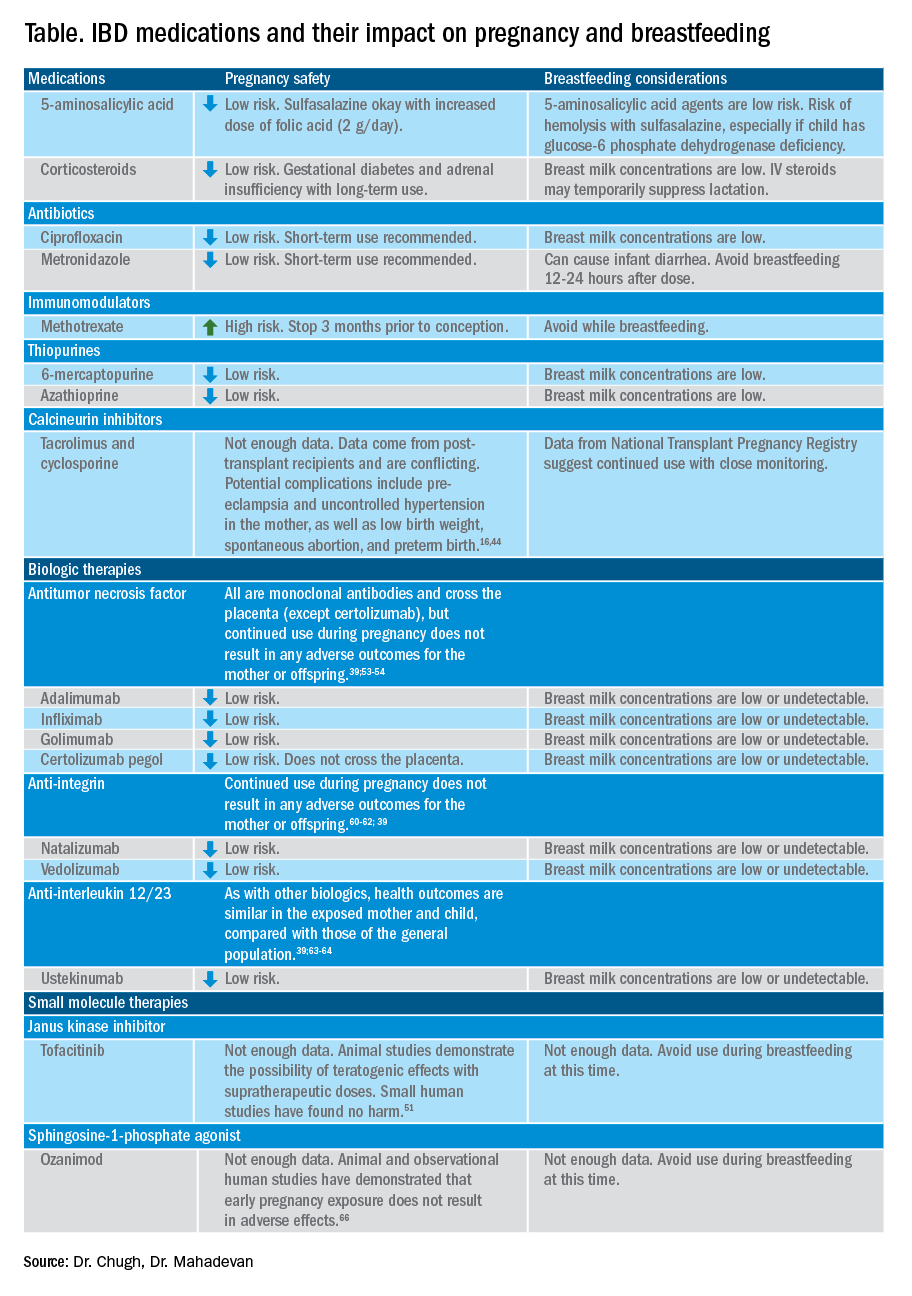

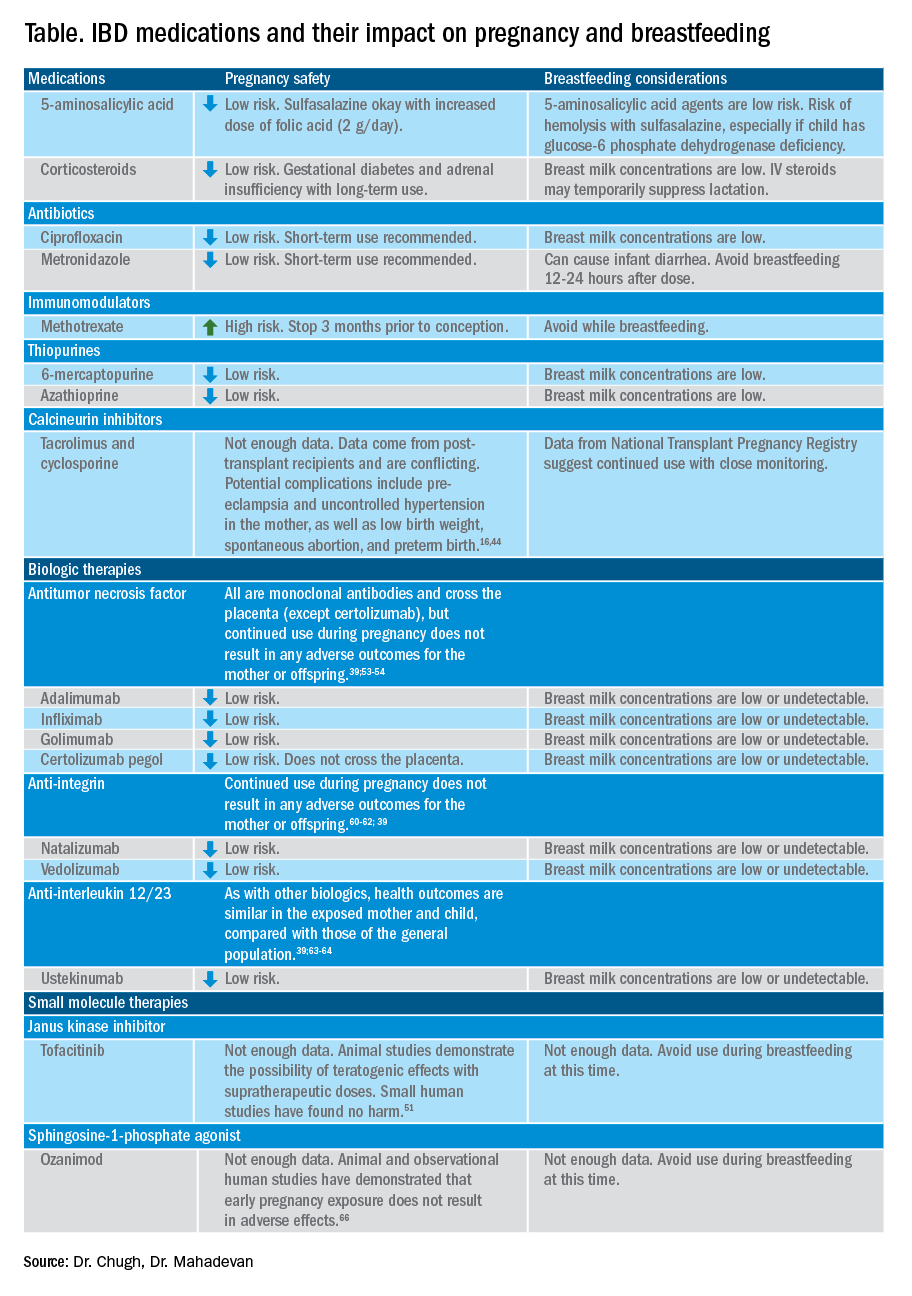

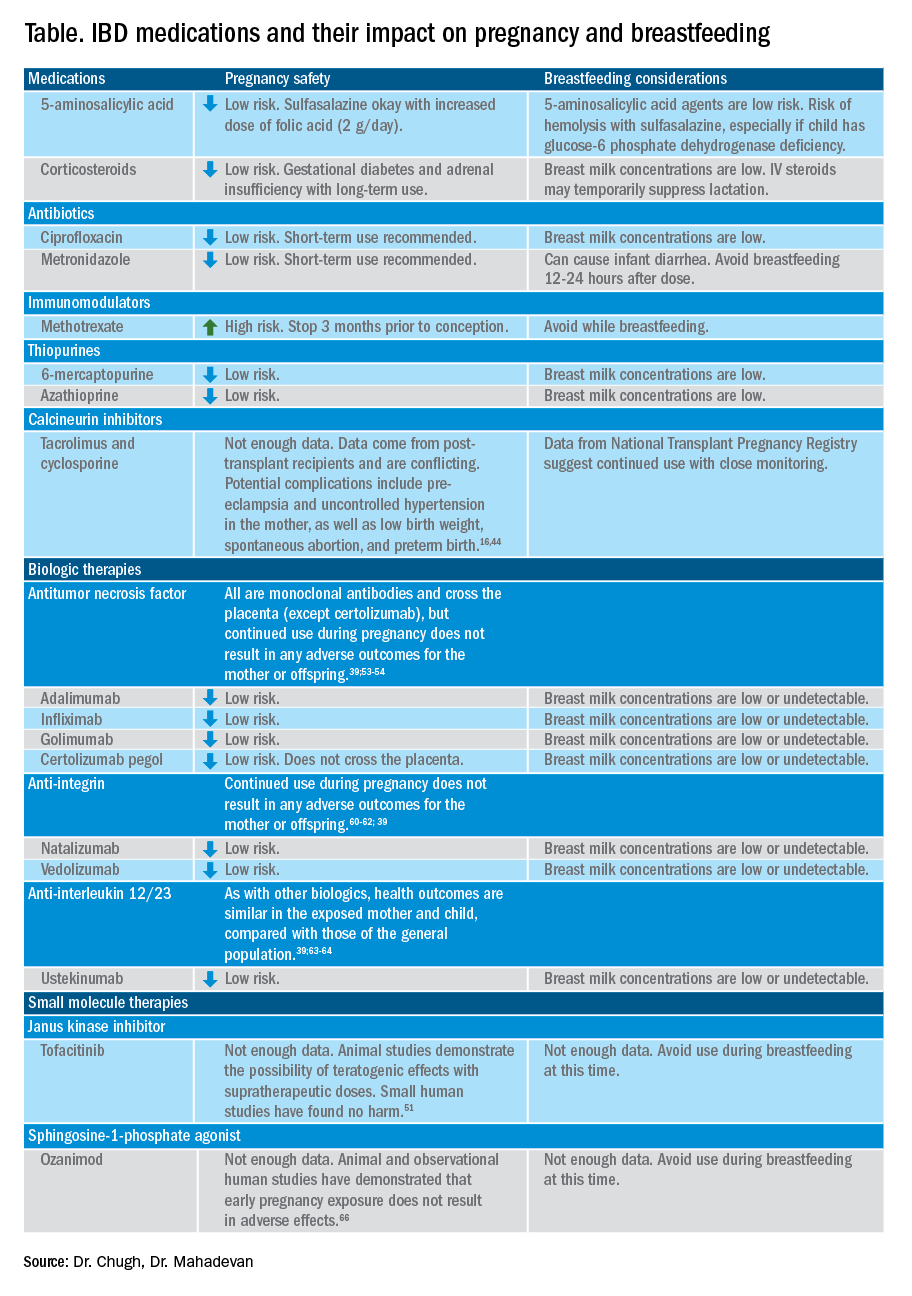

Steroid-free remission for at least 3 months prior to conception is recommended and is associated with reduced risk of flare during pregnancy.16,19 IBD medications needed to control disease activity are generally safe preconception and during pregnancy, with some exception (Table).

Misconceptions regarding heritability of IBD have sometimes discouraged men and women from having children. While genetics may increase susceptibility, environmental and other factors are involved as well. The concordance rates for monozygotic twins range from 33.3%-58.3% for Crohn’s disease and 13.4%-27.9% for ulcerative colitis (UC).20 The risk of a child developing IBD is higher in those who have multiple relatives with IBD and whose parents had IBD at the time of conception.21 While genetic testing for IBD loci is available, it is not commonly performed at this time as many genes are involved.22

Pregnancy

Coordinated care

A complete team of specialists with coordinated care among all providers is needed for optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.23,24 A gastroenterologist, ideally an IBD specialist, should follow the patient throughout pregnancy, seeing the patient at least once during the first or second trimester and as needed during pregnancy.16 A high-risk obstetrician or maternal-fetal medicine specialist should be involved early in pregnancy, as well. Open communication among all disciplines ensures that a common message is conveyed to the patient.16,24 A nutritionist, mental health provider, and lactation specialist knowledgeable about IBD drugs may be of assistance, as well.16

Disease activity

While women with IBD are at increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and labor complications, this risk is mitigated by controlling disease activity.25 The risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth, and delivery via C-section is much higher in women with moderate-to-high disease activity, compared with those with low disease activity.26 The presence of active perianal disease mandates C-section over vaginal delivery. Fourth-degree lacerations following vaginal delivery are most common among those patients with perianal disease.26,27 Stillbirths were shown to be increased only in those with active IBD when compared with non-IBD comparators and inactive IBD.28-31;11

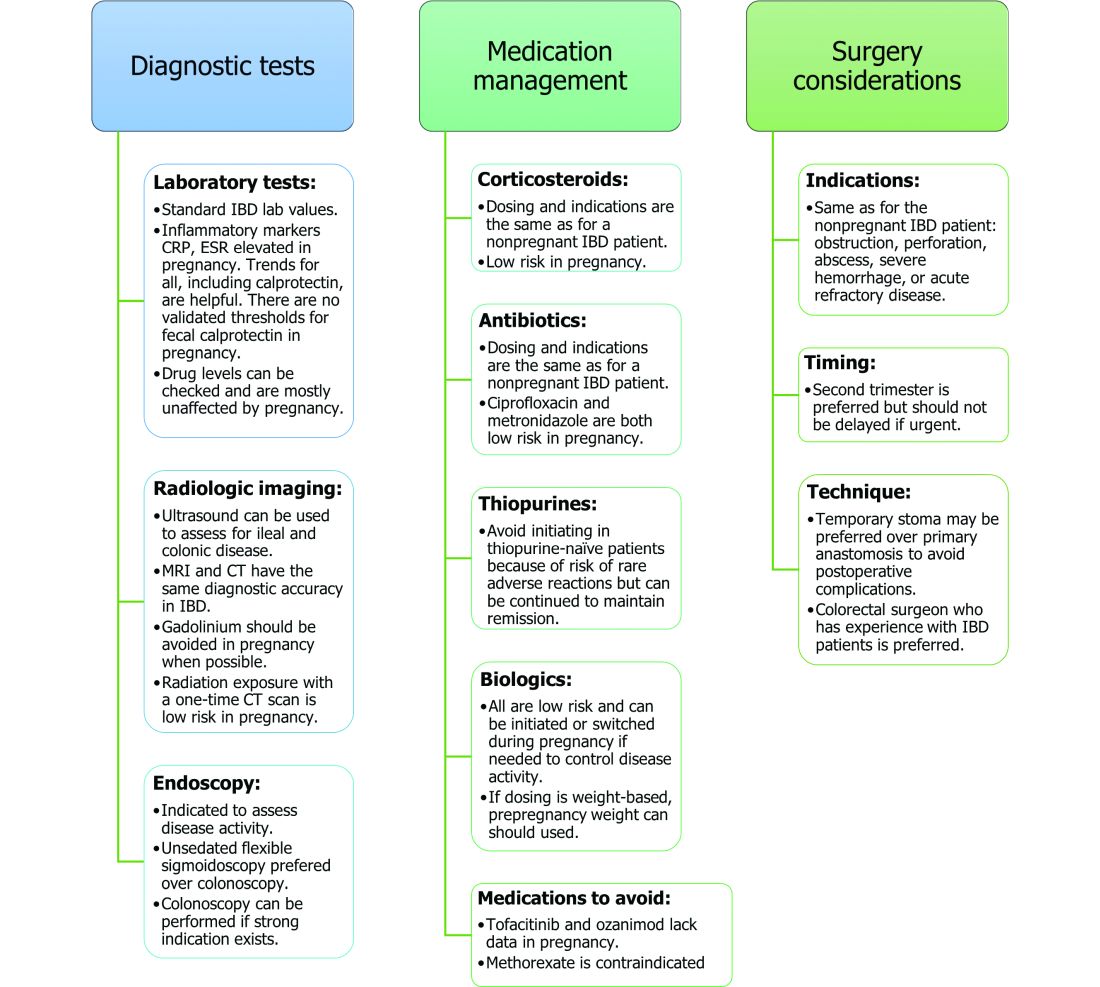

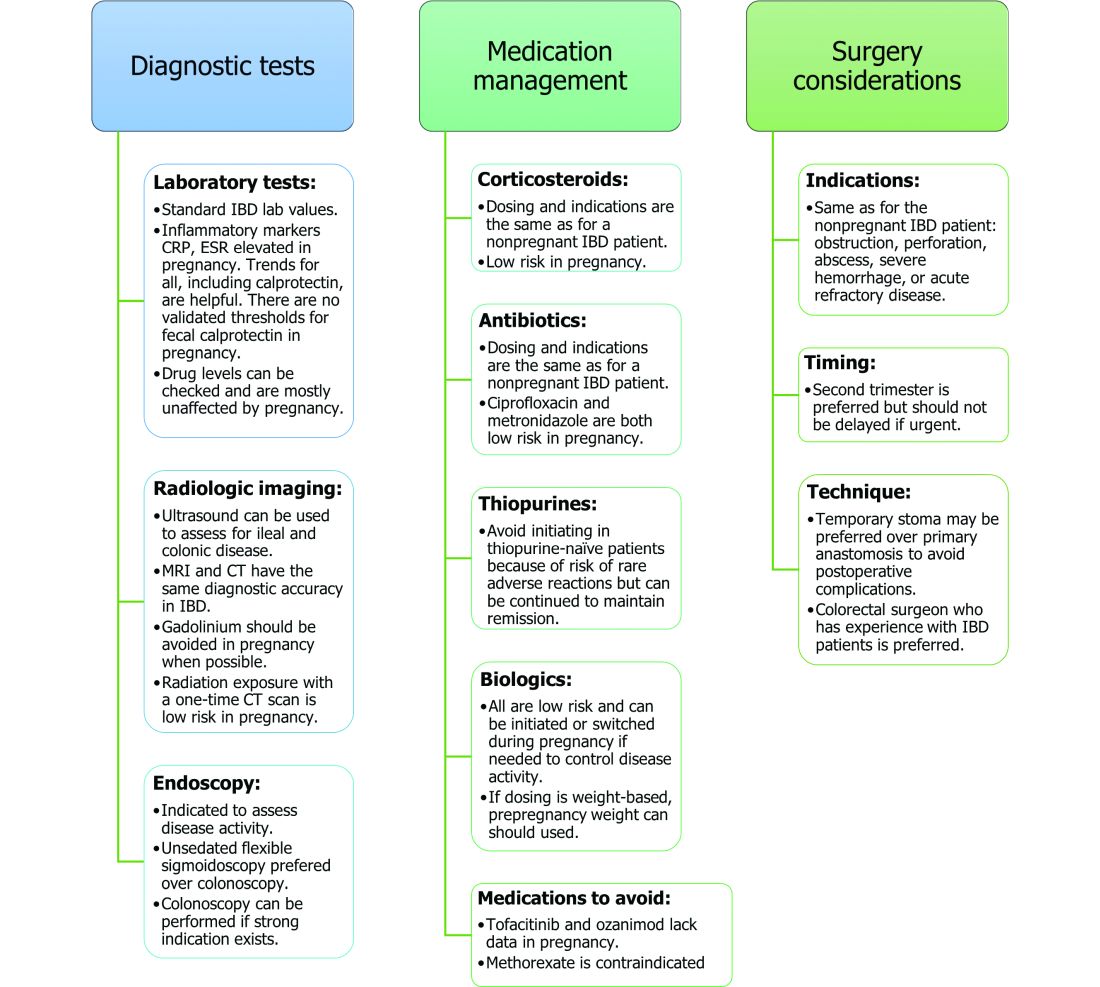

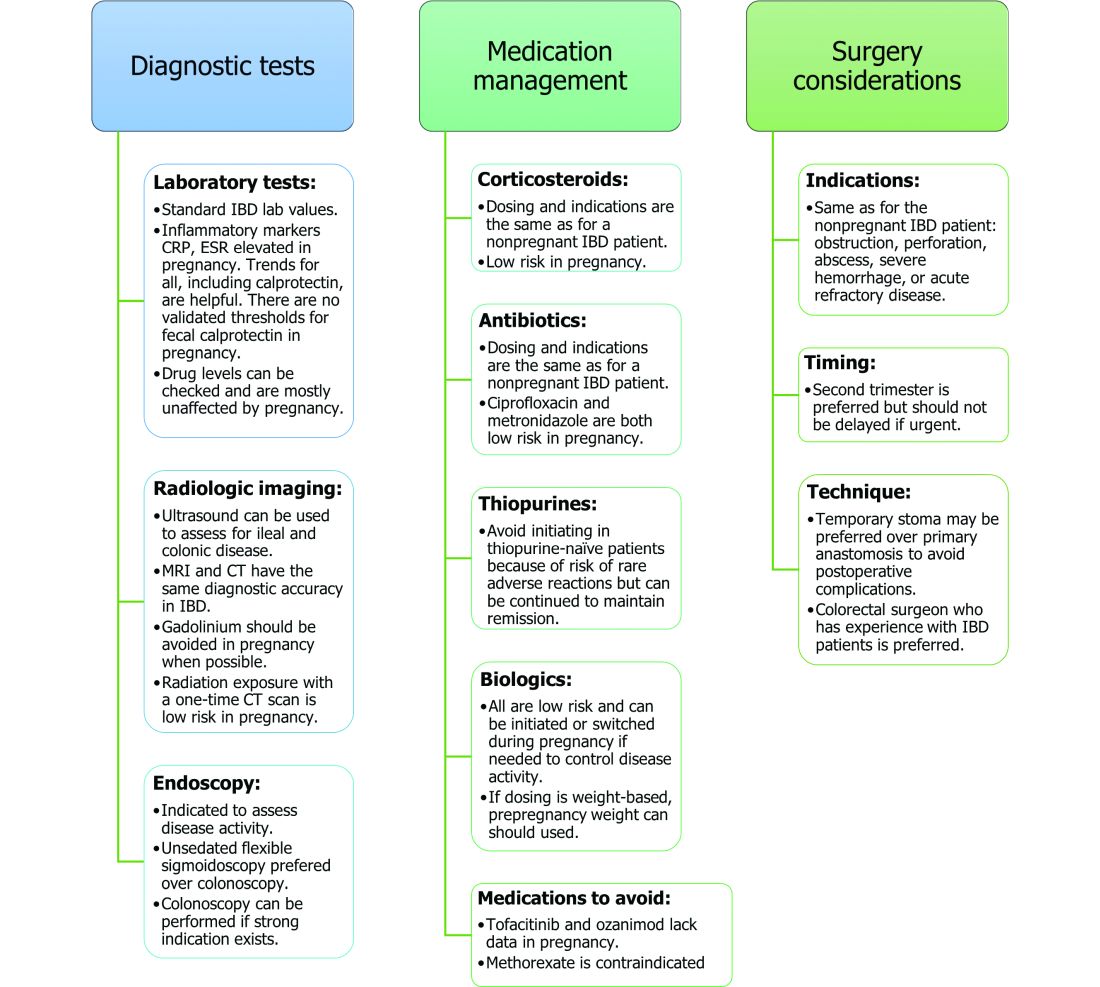

Noninvasive methods for disease monitoring are preferred in pregnancy, but serum markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may not be reliable in the pregnant patient (Figure).32 Fecal calprotectin does rise in correlation with disease activity, but exact thresholds have not been validated in pregnancy.33,34

An unsedated, unprepped flexible sigmoidoscopy can be safely performed throughout pregnancy.35 When there is a strong indication, a complete colonoscopy can be performed in the pregnant patient as well.36 Current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines suggest placing the patient in the left lateral tilt position to avoid decreased maternal and placental perfusion via compression of the aorta or inferior vena cava and performing endoscopy during the second trimester, although trimester-specific timing is not always feasible by indication.37

Medication use and safety

IBD medications are a priority topic of concern among pregnant patients or those considering conception.38 Comprehensive data from the PIANO (Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes) registry has shown that most IBD drugs do not result in adverse pregnancy outcomes and should be continued.39 The use of biologics and thiopurines, either in combination or alone, is not related to an increased risk of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or infections during the child’s first year of life.7,39 Developmental milestones also remain unaffected.39 Here, we will discuss safety considerations during pregnancy (see Table).

5-aminosalycylic acid. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) agents are generally low risk during pregnancy and should be continued.40-41 Sulfasalazine does interfere with folate metabolism, but by increasing folic acid supplementation to 2 grams per day, sulfasalazine can be continued throughout pregnancy, as well.42

Corticosteroids. Intrapartum corticosteroid use is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes and adrenal insufficiency when used long term.43-45 Short-term use may, however, be necessary to control an acute flare. The lowest dose for the shortest duration possible is recommended. Because of its high first-pass metabolism, budesonide is considered low risk in pregnancy.

Methotrexate. Methotrexate needs to be stopped at least 3 months prior to conception and should be avoided throughout pregnancy. Use during pregnancy can result in spontaneous abortions, as well as embryotoxicity.46

Thiopurines (6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine). Patients who are taking thiopurines prior to conception to maintain remission can continue to do so. Data on thiopurines from the PIANO registry has shown no increase in spontaneous abortions, congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, rates of infection in the child, or developmental delays.47-51

Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). Calcineurin inhibitors are reserved for the management of acute severe UC. Safety data on calcineurin inhibitors is conflicting, and there is not enough information at this time to identify risk during pregnancy. Cyclosporine can be used for salvage therapy if absolutely needed, and there are case reports of its successful using during pregnancy.16,52

Biologic therapies. With the exception of certolizumab, all of the currently used biologics are actively transported across the placenta.39,53,54 Intrapartum use of biologic therapies does not worsen pregnancy or neonatal outcomes, including the risk for intensive care unit admission, infections, and developmental milestones.39,47

While drug concentrations may vary slightly during pregnancy, these changes are not substantial enough to warrant more frequent monitoring or dose adjustments, and prepregnancy weight should be used for dosing.55,56

Antitumor necrosis factor agents used in IBD include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab.57 All are low risk for pregnant patients and their offspring. Dosage timings can be adjusted, but not stopped, to minimize exposure to the child; however, it cannot be adjusted for certolizumab pegol because of its lack of placental transfer.58-59

Natalizumab and vedolizumab are integrin receptor antagonists and are also low risk in pregnancy.57;60-62;39

Ustekinumab, an interleukin-12/23 antagonist, can be found in infant serum and cord blood, as well. Health outcomes are similar in the exposed mother and child, however, compared with those of the general population.39;63-64

Small molecule drugs. Unlike monoclonal antibodies, which do not cross the placenta in large amounts until early in the second trimester, small molecules can cross in the first trimester during the critical period of organogenesis.

The two small molecule agents currently approved for use in UC are tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor, and ozanimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist.65-66 Further data are still needed to make recommendations on the use of tofacitinib and ozanimod in pregnancy. At this time, we recommend weighing the risks (unknown risk to human pregnancy) vs. benefits (controlled disease activity with clear risk of harm to mother and baby from flare) in the individual patient before counseling on use in pregnancy.

Delivery

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery should be determined by the obstetrician. C-section is recommended for patients with active perianal disease or, in some cases, a history of ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA).67-68 Vaginal delivery in the setting of perianal disease has been shown to increase the risk of fourth-degree laceration and anal sphincter dysfunction in the future.26-27 Anorectal motility may be impacted by IPAA construction and vaginal delivery independently of each other. It is therefore suggested that vaginal delivery be avoided in patients with a history of IPAA to avoid compounding the risk. Some studies do not show clear harm from vaginal delivery in the setting of IPAA, however, and informed decision making among all stakeholders should be had.27;69-70

Anticoagulation

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is elevated in patients with IBD during pregnancy, and up to 12 weeks postpartum, compared with pregnant patients without IBD.71-72 VTE for prophylaxis is indicated in the pregnant patient while hospitalized and potentially thereafter depending on the patient’s risk factors, which may include obesity, prior personal history of VTE, heart failure, and prolonged immobility. Unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and warfarin are safe for breastfeeding women.16,73

Postpartum care of mother

There is a risk of postpartum flare, occurring in about one third of patients in the first 6 months postpartum.74-75 De-escalating therapy during delivery or immediately postpartum is a predictor of a postpartum flare.75 If no infection is present and the timing interval is appropriate, biologic therapies should be continued and can be resumed 24 hours after a vaginal delivery and 48 hours after a C-section.16,76

NSAIDs and opioids can be used for pain relief but should be avoided in the long-term to prevent flares (NSAIDs) and infant sedation (associated with opioids) when used while breastfeeding.77 The LactMed database is an excellent resource for clarification on risk of medication use while breastfeeding.78

In particular, contraception should be addressed postpartum. Exogenous estrogen use increases the risk of VTE, which is already increased in IBD; nonestrogen containing, long-acting reversible contraception is preferred.79-80 Progestin-only implants or intrauterine devices may be used first line. The efficacy of oral contraceptives is theoretically reduced in those with rapid bowel transit, active small bowel inflammation, and prior small bowel resection, so adding another form of contraception is recommended.16,81

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Postdelivery care of baby

Breastfeeding

Guidelines regarding medication use during breastfeeding are similar to those in pregnancy (see Table). Breastfeeding on biologics and thiopurines can continue without interruption in the child. Thiopurine concentrations in breast milk are low or undetectable.82,78 TNF receptor antagonists, anti-integrin therapies, and ustekinumab are found in low to undetectable levels in breast milk, as well.78

On the other hand, the active metabolite of methotrexate is detectable in breast milk and most sources recommend not breastfeeding on methotrexate. At doses used in IBD (15-25 milligrams per week), some experts have suggested avoiding breastfeeding for 24 hours following a dose.57,78 It is the practice of this author to recommend not breastfeeding at all on methotrexate.

5-ASA therapies are low risk for breastfeeding, but alternatives to sulfasalazine are preferred. The sulfapyridine metabolite transfers to breast milk and may cause hemolysis in infants born with a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.78

With regards to calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus appears in breast milk in low quantities, while cyclosporine levels are variable. Data from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry suggest that these medications can be used at the time of breastfeeding with close monitoring.78

There is not enough data on small molecule therapies at this time to support breastfeeding safety, and it is our practice to not recommend breastfeeding in this scenario.

The transfer of steroids to the child via breast milk does occur but at subtherapeutic levels.16 Budesonide has high first pass metabolism and is low risk during breastfeeding.83-84 As far as is known, IBD maintenance medications do not suppress lactation. The use of intravenous corticosteroids can, however, temporarily decrease milk production.16,85

Vaccines

Vaccination of infants can proceed as indicated by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, with one exception. If the child’s mother was exposed to any biologic agents (not including certolizumab) during the third trimester, any live vaccines should be withheld in the first 6 months of life. In the United States, this restriction currently only applies to the rotavirus vaccine, which is administered starting at the age of 2 months.16,86 Notably, inadvertent administration of the rotavirus vaccine in the biologic-exposed child does not appear to result in any adverse effects.87 Immunity is achieved even if the child is exposed to IBD therapies through breast milk.88

Developmental milestones

Infant exposure to biologics and thiopurines has not been shown to result in any developmental delays. The PIANO study measured developmental milestones at 48 months from birth and found no differences when compared with validated population norms.39 A separate study observing childhood development up to 7 years of age in patients born to mothers with IBD found similar cognitive scores and motor development when compared with those born to mothers without IBD.89

Conclusion

Women considering conception should be optimized prior to pregnancy and maintained on appropriate medications throughout pregnancy and lactation to achieve a healthy pregnancy for both mother and baby. To date, biologics and thiopurines are not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. More data are needed for small molecules.

Dr. Chugh is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan is professor of medicine and codirector at the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan has potential conflicts related to AbbVie, Janssen, BMS, Takeda, Pfizer, Lilly, Gilead, Arena, and Prometheus Biosciences.

References

1. Ye Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:619-25.

2. Sykora J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2741-63.

3. Murakami Y et al. J Gastroenterol 2019;54:1070-7.

4. Hashash JG and Kane S. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y) 2015;11:96-102.

5. Miller JP. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:221-5.

6. Cornish J et al. Gut. 2007;56:830-7.

7. Leung KK et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:550-62.

8. O’Toole A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2750-61.

9. Nguyen GC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1105-11.

10. Lee HH et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:861-9.

11. Kim MA et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:719-32.

12. Conradt E et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144.

13. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762: Prepregnancy Counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e78-e89.

14. Farraye FA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:241-58.

15. Lee S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:702-9.

16. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:627-41.

17. Ward MG et al. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2015;21:2839-47.

18. Battat R et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1120-8.

19. Pedersen N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:501-12.

20. Annese V. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:104892.

21. Bennett RA et al. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1638-43.

22. Turpin W et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1133-48.

23. de Lima A et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1285-92 e1.

24. Selinger C et al. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12:182-7.

25. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106-12.

26. Hatch Q et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:174-8.

27. Foulon A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:712-20.

28. Norgard B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1947-54.

29. Broms G et al. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:1462-9.

30. Meyer A et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1480-90.

31. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1011-8.

32. Tandon P et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:574-81.

33. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:839-48.

34. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1240-6.

35. Ko MS et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2979-85.

36. Cappell MS et al. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:115-23.

37. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:18-24.

38. Aboubakr A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:1829-35.

39. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1131-9.

40. Diav-Citrin O et al. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:23-8.

41. Rahimi R et al. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:271-5.

42. Norgard B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:483-6.

43. Leung YP et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:223-30.

44. Schulze H et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:991-1008.

45. Szymanska E et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101777.

46. Weber-Schoendorfer C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1101-10.

47. Nielsen OH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):74-87.e3.

48. Coelho J et al. Gut. 2011;60:198-203.

49. Sheikh M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:680-4.

50. Kanis SL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1232-41 e1.

51. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2494-500.

52. Rosen MH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:971-3.

53. Porter C et al. J Reprod Immunol. 2016;116:7-12.

54. Mahadevan U et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:286-92; quiz e24.

55. Picardo S and Seow CH. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;44-5:101670.

56. Flanagan E et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1551-62.

57. Singh S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2512-56 e9.

58. de Lima A et al. Gut. 2016;65:1261-8.

59. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:93-102.

60. Wils P et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:460-70.

61. Mahadevan U et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:941-50.

62. Bar-Gil Shitrit A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1172-5.

63. Klenske E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:267-9.

64. Matro R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696-704.

65. Feuerstein JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450-61.

66. Sandborn WJ et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jul 5;15(7):1120-1129.

67. Lamb CA et al. Gut. 2019;68:s1-s106.

68. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:734-57 e1.

69. Ravid A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1283-8.

70. Seligman NS et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:525-30.

71. Kim YH et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17309.

72. Hansen AT et al. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:702-8.

73. Bates SM et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:92-128.

74. Bennett A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 May 17;izab104.

75. Yu A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1926-32.

76. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:451-62 e2.

77. Long MD et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:152-6.

78. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). 2006 ed. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine (US), 2006-2021.

79. Khalili H et al. Gut. 2013;62:1153-9.

80. Long MD and Hutfless S. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1518-20.

81. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

82. Angelberger S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:95-100.

83. Vestergaard T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1459-62.

84. Beaulieu DB et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:25-8.

85. Anderson PO. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:199-201.

86. Wodi AP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:189-92.

87. Chiarella-Redfern H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 5;28(1):79-86.

88. Beaulieu DB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:99-105.

89. Friedman S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Dec 2;14(12):1709-1716.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incidence is rising globally.1-3 In the United States, we have seen a 123% increase in prevalence of IBD among adults and a 133% increase among children from 2007 to 2016, with an annual percentage change of 9.9%.1 The rise of IBD in young people, and the overall higher prevalence in women compared with men, make pregnancy and IBD a topic of increasing importance for gastroenterologists.1 Here, we will discuss management and expectations in women with IBD before conception, during pregnancy, and post partum.

Preconception

Disease activity

Achieving both clinical and endoscopic remission of disease prior to conception is the key to ensuring the best maternal and fetal outcomes. Patients with IBD who conceive while in remission remain in remission 80% of the time.4,5 On the other hand, those who conceive while their disease is active may continue to have active or worsening disease in nearly 70% of cases.4 Active disease has been associated with an increased incidence of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small-for-gestational-age birth.6-8 Active disease can also exacerbate malnutrition and result in poor maternal weight gain, which is associated with intrauterine growth restriction.9,7 Pregnancy outcomes in patients with IBD and quiescent disease are similar to those in the general population.10,11

Health care maintenance

Optimizing maternal health prior to conception is critical. Alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, and marijuana should all be avoided. Opioids should be tapered off prior to conception, as continued use may result in neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome and long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.12,13 In addition, aiming for a healthy body mass index between 18 and 25 months prior to conception allows for better overall pregnancy outcomes.13 Appropriate cancer screening includes colon cancer screening in those with more than 8 years of colitis, regular pap smear for cervical cancer, and annual total body skin cancer examinations for patients on thiopurines and biologic therapies.14

Nutrition

Folic acid supplementation with at least 400 micrograms (mcg) daily is necessary for all women planning pregnancy. Patients with small bowel involvement or history of small bowel resection should have a folate intake of a minimum of 2 grams per day. Adequate vitamin D levels (at least 20 ng/mL) are recommended in all women with IBD. Those with malabsorption should be screened for deficiencies in vitamin B12, folate, and iron.13 These nutritional markers should be evaluated prepregnancy, during the first trimester, and thereafter as needed.15-18

Preconception counseling

Steroid-free remission for at least 3 months prior to conception is recommended and is associated with reduced risk of flare during pregnancy.16,19 IBD medications needed to control disease activity are generally safe preconception and during pregnancy, with some exception (Table).

Misconceptions regarding heritability of IBD have sometimes discouraged men and women from having children. While genetics may increase susceptibility, environmental and other factors are involved as well. The concordance rates for monozygotic twins range from 33.3%-58.3% for Crohn’s disease and 13.4%-27.9% for ulcerative colitis (UC).20 The risk of a child developing IBD is higher in those who have multiple relatives with IBD and whose parents had IBD at the time of conception.21 While genetic testing for IBD loci is available, it is not commonly performed at this time as many genes are involved.22

Pregnancy

Coordinated care

A complete team of specialists with coordinated care among all providers is needed for optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.23,24 A gastroenterologist, ideally an IBD specialist, should follow the patient throughout pregnancy, seeing the patient at least once during the first or second trimester and as needed during pregnancy.16 A high-risk obstetrician or maternal-fetal medicine specialist should be involved early in pregnancy, as well. Open communication among all disciplines ensures that a common message is conveyed to the patient.16,24 A nutritionist, mental health provider, and lactation specialist knowledgeable about IBD drugs may be of assistance, as well.16

Disease activity

While women with IBD are at increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and labor complications, this risk is mitigated by controlling disease activity.25 The risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth, and delivery via C-section is much higher in women with moderate-to-high disease activity, compared with those with low disease activity.26 The presence of active perianal disease mandates C-section over vaginal delivery. Fourth-degree lacerations following vaginal delivery are most common among those patients with perianal disease.26,27 Stillbirths were shown to be increased only in those with active IBD when compared with non-IBD comparators and inactive IBD.28-31;11

Noninvasive methods for disease monitoring are preferred in pregnancy, but serum markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may not be reliable in the pregnant patient (Figure).32 Fecal calprotectin does rise in correlation with disease activity, but exact thresholds have not been validated in pregnancy.33,34

An unsedated, unprepped flexible sigmoidoscopy can be safely performed throughout pregnancy.35 When there is a strong indication, a complete colonoscopy can be performed in the pregnant patient as well.36 Current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines suggest placing the patient in the left lateral tilt position to avoid decreased maternal and placental perfusion via compression of the aorta or inferior vena cava and performing endoscopy during the second trimester, although trimester-specific timing is not always feasible by indication.37

Medication use and safety

IBD medications are a priority topic of concern among pregnant patients or those considering conception.38 Comprehensive data from the PIANO (Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes) registry has shown that most IBD drugs do not result in adverse pregnancy outcomes and should be continued.39 The use of biologics and thiopurines, either in combination or alone, is not related to an increased risk of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or infections during the child’s first year of life.7,39 Developmental milestones also remain unaffected.39 Here, we will discuss safety considerations during pregnancy (see Table).

5-aminosalycylic acid. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) agents are generally low risk during pregnancy and should be continued.40-41 Sulfasalazine does interfere with folate metabolism, but by increasing folic acid supplementation to 2 grams per day, sulfasalazine can be continued throughout pregnancy, as well.42

Corticosteroids. Intrapartum corticosteroid use is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes and adrenal insufficiency when used long term.43-45 Short-term use may, however, be necessary to control an acute flare. The lowest dose for the shortest duration possible is recommended. Because of its high first-pass metabolism, budesonide is considered low risk in pregnancy.

Methotrexate. Methotrexate needs to be stopped at least 3 months prior to conception and should be avoided throughout pregnancy. Use during pregnancy can result in spontaneous abortions, as well as embryotoxicity.46

Thiopurines (6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine). Patients who are taking thiopurines prior to conception to maintain remission can continue to do so. Data on thiopurines from the PIANO registry has shown no increase in spontaneous abortions, congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, rates of infection in the child, or developmental delays.47-51

Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). Calcineurin inhibitors are reserved for the management of acute severe UC. Safety data on calcineurin inhibitors is conflicting, and there is not enough information at this time to identify risk during pregnancy. Cyclosporine can be used for salvage therapy if absolutely needed, and there are case reports of its successful using during pregnancy.16,52

Biologic therapies. With the exception of certolizumab, all of the currently used biologics are actively transported across the placenta.39,53,54 Intrapartum use of biologic therapies does not worsen pregnancy or neonatal outcomes, including the risk for intensive care unit admission, infections, and developmental milestones.39,47

While drug concentrations may vary slightly during pregnancy, these changes are not substantial enough to warrant more frequent monitoring or dose adjustments, and prepregnancy weight should be used for dosing.55,56

Antitumor necrosis factor agents used in IBD include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab.57 All are low risk for pregnant patients and their offspring. Dosage timings can be adjusted, but not stopped, to minimize exposure to the child; however, it cannot be adjusted for certolizumab pegol because of its lack of placental transfer.58-59

Natalizumab and vedolizumab are integrin receptor antagonists and are also low risk in pregnancy.57;60-62;39

Ustekinumab, an interleukin-12/23 antagonist, can be found in infant serum and cord blood, as well. Health outcomes are similar in the exposed mother and child, however, compared with those of the general population.39;63-64

Small molecule drugs. Unlike monoclonal antibodies, which do not cross the placenta in large amounts until early in the second trimester, small molecules can cross in the first trimester during the critical period of organogenesis.

The two small molecule agents currently approved for use in UC are tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor, and ozanimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist.65-66 Further data are still needed to make recommendations on the use of tofacitinib and ozanimod in pregnancy. At this time, we recommend weighing the risks (unknown risk to human pregnancy) vs. benefits (controlled disease activity with clear risk of harm to mother and baby from flare) in the individual patient before counseling on use in pregnancy.

Delivery

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery should be determined by the obstetrician. C-section is recommended for patients with active perianal disease or, in some cases, a history of ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA).67-68 Vaginal delivery in the setting of perianal disease has been shown to increase the risk of fourth-degree laceration and anal sphincter dysfunction in the future.26-27 Anorectal motility may be impacted by IPAA construction and vaginal delivery independently of each other. It is therefore suggested that vaginal delivery be avoided in patients with a history of IPAA to avoid compounding the risk. Some studies do not show clear harm from vaginal delivery in the setting of IPAA, however, and informed decision making among all stakeholders should be had.27;69-70

Anticoagulation

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is elevated in patients with IBD during pregnancy, and up to 12 weeks postpartum, compared with pregnant patients without IBD.71-72 VTE for prophylaxis is indicated in the pregnant patient while hospitalized and potentially thereafter depending on the patient’s risk factors, which may include obesity, prior personal history of VTE, heart failure, and prolonged immobility. Unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and warfarin are safe for breastfeeding women.16,73

Postpartum care of mother