User login

First-of-its kind guideline on lipid monitoring in endocrine diseases

Endocrine diseases of any type – not just diabetes – can represent a cardiovascular risk and patients with those disorders should be screened for high cholesterol, according to a new clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society.

“The simple recommendation to check a lipid panel in patients with endocrine diseases and calculate cardiovascular risk may be practice changing because that is not done routinely,” Connie Newman, MD, chair of the Endocrine Society committee that developed the guideline, said in an interview.

“Usually the focus is on assessment and treatment of the endocrine disease, rather than on assessment and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk,” said Newman, an adjunct professor of medicine in the department of medicine, division of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism, at New York University.

Whereas diabetes, well-known for its increased cardiovascular risk profile, is commonly addressed in other cardiovascular and cholesterol practice management guidelines, the array of other endocrine diseases are not typically included.

“This guideline is the first of its kind,” Dr. Newman said. “The Endocrine Society has not previously issued a guideline on lipid management in endocrine disorders [and] other organizations have not written guidelines on this topic.

“Rather, guidelines have been written on cholesterol management, but these do not describe cholesterol management in patients with endocrine diseases such as thyroid disease [hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism], Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, growth hormone deficiency, menopause, male hypogonadism, and obesity,” she noted.

But these conditions carry a host of cardiovascular risk factors that may require careful monitoring and management.

“Although endocrine hormones, such as thyroid hormone, cortisol, estrogen, testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin, affect pathways for lipid metabolism, physicians lack guidance on lipid abnormalities, cardiovascular risk, and treatment to reduce lipids and cardiovascular risk in patients with endocrine diseases,” she explained.

Vinaya Simha, MD, an internal medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., agrees that the guideline is notable in addressing an unmet need.

Recommendations that stand out to Dr. Simha include the suggestion of adding eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) ethyl ester to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with diabetes or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who have elevated triglyceride levels despite statin treatment.

James L. Rosenzweig, MD, an endocrinologist at Hebrew SeniorLife in Boston, agreed that this is an important addition to an area that needs more guidance.

“Many of these clinical situations can exacerbate dyslipidemia and some also increase the cardiovascular risk to a greater extent in combination with elevated cholesterol and/or triglycerides,” he said in an interview.

“In many cases, treatment of the underlying disorder appropriately can have an important impact in resolving the lipid disorder. In others, more aggressive pharmacological treatment is indicated,” he said.

“I think that this will be a valuable resource, especially for endocrinologists, but it can be used as well by providers in other disciplines.”

Key recommendations for different endocrine conditions

The guideline, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, details those risks and provides evidence-based recommendations on their management and treatment.

Key recommendations include:

- Obtain a lipid panel and evaluate cardiovascular risk factors in all adults with endocrine disorders.

- In patients with and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, start statin therapy in addition to lifestyle modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. “This could mean earlier treatment because other guidelines recommend consideration of therapy at age 40,” Dr. Newman said.

- Statin therapy is also recommended for adults over 40 with with a duration of diabetes of more than 20 years and/or microvascular complications, regardless of their cardiovascular risk score. “This means earlier treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes with statins in order to reduce cardiovascular disease risk,” Dr. Newman noted.

- In patients with hyperlipidemia, rule out as the cause before treating with lipid-lowering medications. And among patients who are found to have hypothyroidism, reevaluate the lipid profile when the patient has thyroid hormone levels in the normal range.

- Adults with persistent endogenous Cushing’s syndrome should have their lipid profile monitored. Statin therapy should be considered in addition to lifestyle modifications, irrespective of the cardiovascular risk score.

- In postmenopausal women, high cholesterol or triglycerides should be treated with statins rather than hormone therapy.

- Evaluate and treat lipids and other cardiovascular risk factors in women who enter menopause early (before the age of 40-45 years).

Nice summary of ‘risk-enhancing’ endocrine disorders

Dr. Simha said in an interview that the new guideline is “probably the first comprehensive statement addressing lipid treatment in patients with a broad range of endocrine disorders besides diabetes.”

“Most of the treatment recommendations are congruent with other current guidelines such as the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [guidelines], but there is specific mention of which endocrine disorders represent enhanced cardiovascular risk,” she explained.

The new recommendations are notable for including “a nice summary of how different endocrine disorders affect lipid values, and also which endocrine disorders need to be considered as ‘risk-enhancing factors,’ ” Dr. Simha noted.

“The use of EPA in patients with hypertriglyceridemia is novel, compared to the ACC/AHA recommendation. This reflects new data which is now available,” she added.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists also just issued a new algorithm on lipid management and prevention of cardiovascular disease in which treatment of hypertriglyceridemia is emphasized.

In addition, the new Endocrine Society guideline “also mentions an LDL [cholesterol] treatment threshold of 70 mg/dL, and 55 mg/dL in some patient categories, which previous guidelines have not,” Dr. Simha noted.

Overall, Dr. Newman added that the goal of the guideline is to increase awareness of key issues with endocrine diseases that may not necessarily be on clinicians’ radars.

“We hope that it will make a lipid panel and cardiovascular risk evaluation routine in adults with endocrine diseases and cause a greater focus on therapies to reduce heart disease and stroke,” she said.

Dr. Newman, Dr. Simha, and Dr. Rosenzweig reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Endocrine diseases of any type – not just diabetes – can represent a cardiovascular risk and patients with those disorders should be screened for high cholesterol, according to a new clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society.

“The simple recommendation to check a lipid panel in patients with endocrine diseases and calculate cardiovascular risk may be practice changing because that is not done routinely,” Connie Newman, MD, chair of the Endocrine Society committee that developed the guideline, said in an interview.

“Usually the focus is on assessment and treatment of the endocrine disease, rather than on assessment and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk,” said Newman, an adjunct professor of medicine in the department of medicine, division of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism, at New York University.

Whereas diabetes, well-known for its increased cardiovascular risk profile, is commonly addressed in other cardiovascular and cholesterol practice management guidelines, the array of other endocrine diseases are not typically included.

“This guideline is the first of its kind,” Dr. Newman said. “The Endocrine Society has not previously issued a guideline on lipid management in endocrine disorders [and] other organizations have not written guidelines on this topic.

“Rather, guidelines have been written on cholesterol management, but these do not describe cholesterol management in patients with endocrine diseases such as thyroid disease [hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism], Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, growth hormone deficiency, menopause, male hypogonadism, and obesity,” she noted.

But these conditions carry a host of cardiovascular risk factors that may require careful monitoring and management.

“Although endocrine hormones, such as thyroid hormone, cortisol, estrogen, testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin, affect pathways for lipid metabolism, physicians lack guidance on lipid abnormalities, cardiovascular risk, and treatment to reduce lipids and cardiovascular risk in patients with endocrine diseases,” she explained.

Vinaya Simha, MD, an internal medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., agrees that the guideline is notable in addressing an unmet need.

Recommendations that stand out to Dr. Simha include the suggestion of adding eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) ethyl ester to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with diabetes or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who have elevated triglyceride levels despite statin treatment.

James L. Rosenzweig, MD, an endocrinologist at Hebrew SeniorLife in Boston, agreed that this is an important addition to an area that needs more guidance.

“Many of these clinical situations can exacerbate dyslipidemia and some also increase the cardiovascular risk to a greater extent in combination with elevated cholesterol and/or triglycerides,” he said in an interview.

“In many cases, treatment of the underlying disorder appropriately can have an important impact in resolving the lipid disorder. In others, more aggressive pharmacological treatment is indicated,” he said.

“I think that this will be a valuable resource, especially for endocrinologists, but it can be used as well by providers in other disciplines.”

Key recommendations for different endocrine conditions

The guideline, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, details those risks and provides evidence-based recommendations on their management and treatment.

Key recommendations include:

- Obtain a lipid panel and evaluate cardiovascular risk factors in all adults with endocrine disorders.

- In patients with and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, start statin therapy in addition to lifestyle modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. “This could mean earlier treatment because other guidelines recommend consideration of therapy at age 40,” Dr. Newman said.

- Statin therapy is also recommended for adults over 40 with with a duration of diabetes of more than 20 years and/or microvascular complications, regardless of their cardiovascular risk score. “This means earlier treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes with statins in order to reduce cardiovascular disease risk,” Dr. Newman noted.

- In patients with hyperlipidemia, rule out as the cause before treating with lipid-lowering medications. And among patients who are found to have hypothyroidism, reevaluate the lipid profile when the patient has thyroid hormone levels in the normal range.

- Adults with persistent endogenous Cushing’s syndrome should have their lipid profile monitored. Statin therapy should be considered in addition to lifestyle modifications, irrespective of the cardiovascular risk score.

- In postmenopausal women, high cholesterol or triglycerides should be treated with statins rather than hormone therapy.

- Evaluate and treat lipids and other cardiovascular risk factors in women who enter menopause early (before the age of 40-45 years).

Nice summary of ‘risk-enhancing’ endocrine disorders

Dr. Simha said in an interview that the new guideline is “probably the first comprehensive statement addressing lipid treatment in patients with a broad range of endocrine disorders besides diabetes.”

“Most of the treatment recommendations are congruent with other current guidelines such as the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [guidelines], but there is specific mention of which endocrine disorders represent enhanced cardiovascular risk,” she explained.

The new recommendations are notable for including “a nice summary of how different endocrine disorders affect lipid values, and also which endocrine disorders need to be considered as ‘risk-enhancing factors,’ ” Dr. Simha noted.

“The use of EPA in patients with hypertriglyceridemia is novel, compared to the ACC/AHA recommendation. This reflects new data which is now available,” she added.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists also just issued a new algorithm on lipid management and prevention of cardiovascular disease in which treatment of hypertriglyceridemia is emphasized.

In addition, the new Endocrine Society guideline “also mentions an LDL [cholesterol] treatment threshold of 70 mg/dL, and 55 mg/dL in some patient categories, which previous guidelines have not,” Dr. Simha noted.

Overall, Dr. Newman added that the goal of the guideline is to increase awareness of key issues with endocrine diseases that may not necessarily be on clinicians’ radars.

“We hope that it will make a lipid panel and cardiovascular risk evaluation routine in adults with endocrine diseases and cause a greater focus on therapies to reduce heart disease and stroke,” she said.

Dr. Newman, Dr. Simha, and Dr. Rosenzweig reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Endocrine diseases of any type – not just diabetes – can represent a cardiovascular risk and patients with those disorders should be screened for high cholesterol, according to a new clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society.

“The simple recommendation to check a lipid panel in patients with endocrine diseases and calculate cardiovascular risk may be practice changing because that is not done routinely,” Connie Newman, MD, chair of the Endocrine Society committee that developed the guideline, said in an interview.

“Usually the focus is on assessment and treatment of the endocrine disease, rather than on assessment and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk,” said Newman, an adjunct professor of medicine in the department of medicine, division of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism, at New York University.

Whereas diabetes, well-known for its increased cardiovascular risk profile, is commonly addressed in other cardiovascular and cholesterol practice management guidelines, the array of other endocrine diseases are not typically included.

“This guideline is the first of its kind,” Dr. Newman said. “The Endocrine Society has not previously issued a guideline on lipid management in endocrine disorders [and] other organizations have not written guidelines on this topic.

“Rather, guidelines have been written on cholesterol management, but these do not describe cholesterol management in patients with endocrine diseases such as thyroid disease [hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism], Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, growth hormone deficiency, menopause, male hypogonadism, and obesity,” she noted.

But these conditions carry a host of cardiovascular risk factors that may require careful monitoring and management.

“Although endocrine hormones, such as thyroid hormone, cortisol, estrogen, testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin, affect pathways for lipid metabolism, physicians lack guidance on lipid abnormalities, cardiovascular risk, and treatment to reduce lipids and cardiovascular risk in patients with endocrine diseases,” she explained.

Vinaya Simha, MD, an internal medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., agrees that the guideline is notable in addressing an unmet need.

Recommendations that stand out to Dr. Simha include the suggestion of adding eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) ethyl ester to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with diabetes or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who have elevated triglyceride levels despite statin treatment.

James L. Rosenzweig, MD, an endocrinologist at Hebrew SeniorLife in Boston, agreed that this is an important addition to an area that needs more guidance.

“Many of these clinical situations can exacerbate dyslipidemia and some also increase the cardiovascular risk to a greater extent in combination with elevated cholesterol and/or triglycerides,” he said in an interview.

“In many cases, treatment of the underlying disorder appropriately can have an important impact in resolving the lipid disorder. In others, more aggressive pharmacological treatment is indicated,” he said.

“I think that this will be a valuable resource, especially for endocrinologists, but it can be used as well by providers in other disciplines.”

Key recommendations for different endocrine conditions

The guideline, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, details those risks and provides evidence-based recommendations on their management and treatment.

Key recommendations include:

- Obtain a lipid panel and evaluate cardiovascular risk factors in all adults with endocrine disorders.

- In patients with and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, start statin therapy in addition to lifestyle modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. “This could mean earlier treatment because other guidelines recommend consideration of therapy at age 40,” Dr. Newman said.

- Statin therapy is also recommended for adults over 40 with with a duration of diabetes of more than 20 years and/or microvascular complications, regardless of their cardiovascular risk score. “This means earlier treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes with statins in order to reduce cardiovascular disease risk,” Dr. Newman noted.

- In patients with hyperlipidemia, rule out as the cause before treating with lipid-lowering medications. And among patients who are found to have hypothyroidism, reevaluate the lipid profile when the patient has thyroid hormone levels in the normal range.

- Adults with persistent endogenous Cushing’s syndrome should have their lipid profile monitored. Statin therapy should be considered in addition to lifestyle modifications, irrespective of the cardiovascular risk score.

- In postmenopausal women, high cholesterol or triglycerides should be treated with statins rather than hormone therapy.

- Evaluate and treat lipids and other cardiovascular risk factors in women who enter menopause early (before the age of 40-45 years).

Nice summary of ‘risk-enhancing’ endocrine disorders

Dr. Simha said in an interview that the new guideline is “probably the first comprehensive statement addressing lipid treatment in patients with a broad range of endocrine disorders besides diabetes.”

“Most of the treatment recommendations are congruent with other current guidelines such as the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [guidelines], but there is specific mention of which endocrine disorders represent enhanced cardiovascular risk,” she explained.

The new recommendations are notable for including “a nice summary of how different endocrine disorders affect lipid values, and also which endocrine disorders need to be considered as ‘risk-enhancing factors,’ ” Dr. Simha noted.

“The use of EPA in patients with hypertriglyceridemia is novel, compared to the ACC/AHA recommendation. This reflects new data which is now available,” she added.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists also just issued a new algorithm on lipid management and prevention of cardiovascular disease in which treatment of hypertriglyceridemia is emphasized.

In addition, the new Endocrine Society guideline “also mentions an LDL [cholesterol] treatment threshold of 70 mg/dL, and 55 mg/dL in some patient categories, which previous guidelines have not,” Dr. Simha noted.

Overall, Dr. Newman added that the goal of the guideline is to increase awareness of key issues with endocrine diseases that may not necessarily be on clinicians’ radars.

“We hope that it will make a lipid panel and cardiovascular risk evaluation routine in adults with endocrine diseases and cause a greater focus on therapies to reduce heart disease and stroke,” she said.

Dr. Newman, Dr. Simha, and Dr. Rosenzweig reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New return-to-play recommendations for athletes with COVID-19

The latest recommendations from sports cardiologists on getting athletes with COVID-19 back on the playing field safely emphasize a more judicious approach to screening for cardiac injury.

The new recommendations, made by the American College of Cardiology’s Sports and Exercise Cardiology Section, are for adult athletes in competitive sports and also for two important groups: younger athletes taking part in competitive high school sports and older athletes aged 35 and older, the Masters athletes, who continue to be active throughout their lives. The document was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

Because of the evolving nature of knowledge about COVID-19, updates on recommendations for safe return to play for athletes of all ages will continue to be made, senior author Aaron L. Baggish, MD, director of the cardiovascular performance program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said.

“The recommendations we released in May were entirely based on our experience taking care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19; we had no athletes in this population. We used a lot of conservative guesswork around how this would apply to otherwise healthy athletes,” Dr. Baggish said in an interview.

“But as sports started to open up, and we started to see large numbers of first professional and then college athletes come back into training, we realized that we needed to stop and ask whether the recommendations we put forward back in May were still appropriate,” Dr. Baggish said.

“Once we started to actually get into the trenches with these athletes, literally hundreds of them, and applying the testing strategies that we had initially recommended in everybody, we realized that we probably had some room for improvement, and that’s why we reconvened, to make these revisions,” he said.

Essentially, the recommendations now urge less cardiac testing. “Cardiac injury is not as common as we may have originally thought,” said Dr. Baggish.

“In the early days of COVID, people who were hospitalized had evidence of heart injury, and so we wondered if that prevalence would also be applicable to otherwise young, healthy people who got COVID. If that had been the case, we would have been in big trouble with respect to getting people back into sports. So this is why we started with a conservative screening approach and a lot of testing in order to not miss a huge burden of disease,” he said.

“But what we’ve learned over the past few months is that young people who get either asymptomatic or mild infection appear to have very, very low risk of having associated heart injury, so the need for testing in that population, when people who have infections recover fully, is almost certainly not going to be high yield,” Dr. Baggish said.

First iteration of the recommendations

Published in May in the early weeks of the pandemic, the first recommendations for safe return to play said that all athletes should stop training for at least 2 weeks after their symptoms resolve, then undergo “careful, clinical cardiovascular evaluation in combination with cardiac biomarkers and imaging.”

Additional testing with cardiac MRI, exercise testing, or ambulatory rhythm monitoring was to be done “based on the clinical course and initial testing.”

But experts caution that monitoring on such a scale in everyone is unnecessary and could even be counterproductive.

“Sending young athletes for extensive testing is not warranted and could send them to unnecessary testing, cardiac imaging, and so on,” Dr. Baggish said.

Only those athletes who continue to have symptoms or whose symptoms return when they get back to their athletic activities should go on for more screening.

“There, in essence, is the single main change from May, and that is a move away from screening with testing everyone, [and instead] confining that to the people who had moderate or greater severity disease,” he said.

Both iterations of the recommendations end with the same message.

“We are at the beginning of our knowledge about the cardiotoxic effects of COVID-19 but we are gathering evidence every day,” said Dr. Baggish. “Just as they did earlier, we acknowledge that our approaches are subject to change when we learn more about how COVID affects the heart, and specifically the hearts of athletes. This will be an ongoing process.”

Something to lean on

The recommendations are welcome, said James E. Udelson, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, coauthor of an accompanying editorial.

“It was a bit of the wild west out there, because each university, each college, all with good intentions, had been all struggling to figure out what to do, and how much to do. Probably the most important message from this new paper is the fact that now there is something out there that all coaches, athletes, families, schools, trainers can get some guidance from,” Dr. Udelson said in an interview.

Refining the cardiac screening criteria was a necessary step, Dr. Udelson said.

“How much cardiac imaging do you do? That is a matter of controversy,” said Dr. Udelson, who coauthored the commentary with Tufts cardiologist Ethan Rowin, MD, and Michael A. Curtis, MEd, a certified strength and conditioning specialist at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. “The problem is that if you use a very sensitive imaging test on a lot of people, sometimes you find things that you really didn’t need to know about. They’re really not important. And now, the athlete is told he or she cannot play for 3 months because they might have myocarditis.

“Should we be too sensitive, meaning do we want to pick up anything no matter whether it’s important or not?” he added. “There will be a lot of false positives, and we are going to disqualify a lot of people. Or do you tune it a different way?”

Dr. Udelson said he would like to see commercial sports donate money to support research into the potential cardiotoxicity of COVID-19.

“If the organizations that benefit from these athletes, like the National Collegiate Athletic Association and professional sports leagues, can fund some of this research, that would be a huge help,” Dr. Udelson said.

“These are the top sports cardiologists in the country, and they have to start somewhere, and these are all based on what we know right now, as well as their own extensive experience. We all know that we are just at the beginning of our knowledge of this. But we have to have something to guide this huge community out there that is really thirsty for help.”

Dr. Baggish reports receiving research funding for the study of athletes in competitive sports from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Football League Players Association; and the American Heart Association and receiving compensation for his role as team cardiologist from the US Olympic Committee/US Olympic Training Centers, US Soccer, US Rowing, the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, and Harvard University. Dr. Udelson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The latest recommendations from sports cardiologists on getting athletes with COVID-19 back on the playing field safely emphasize a more judicious approach to screening for cardiac injury.

The new recommendations, made by the American College of Cardiology’s Sports and Exercise Cardiology Section, are for adult athletes in competitive sports and also for two important groups: younger athletes taking part in competitive high school sports and older athletes aged 35 and older, the Masters athletes, who continue to be active throughout their lives. The document was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

Because of the evolving nature of knowledge about COVID-19, updates on recommendations for safe return to play for athletes of all ages will continue to be made, senior author Aaron L. Baggish, MD, director of the cardiovascular performance program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said.

“The recommendations we released in May were entirely based on our experience taking care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19; we had no athletes in this population. We used a lot of conservative guesswork around how this would apply to otherwise healthy athletes,” Dr. Baggish said in an interview.

“But as sports started to open up, and we started to see large numbers of first professional and then college athletes come back into training, we realized that we needed to stop and ask whether the recommendations we put forward back in May were still appropriate,” Dr. Baggish said.

“Once we started to actually get into the trenches with these athletes, literally hundreds of them, and applying the testing strategies that we had initially recommended in everybody, we realized that we probably had some room for improvement, and that’s why we reconvened, to make these revisions,” he said.

Essentially, the recommendations now urge less cardiac testing. “Cardiac injury is not as common as we may have originally thought,” said Dr. Baggish.

“In the early days of COVID, people who were hospitalized had evidence of heart injury, and so we wondered if that prevalence would also be applicable to otherwise young, healthy people who got COVID. If that had been the case, we would have been in big trouble with respect to getting people back into sports. So this is why we started with a conservative screening approach and a lot of testing in order to not miss a huge burden of disease,” he said.

“But what we’ve learned over the past few months is that young people who get either asymptomatic or mild infection appear to have very, very low risk of having associated heart injury, so the need for testing in that population, when people who have infections recover fully, is almost certainly not going to be high yield,” Dr. Baggish said.

First iteration of the recommendations

Published in May in the early weeks of the pandemic, the first recommendations for safe return to play said that all athletes should stop training for at least 2 weeks after their symptoms resolve, then undergo “careful, clinical cardiovascular evaluation in combination with cardiac biomarkers and imaging.”

Additional testing with cardiac MRI, exercise testing, or ambulatory rhythm monitoring was to be done “based on the clinical course and initial testing.”

But experts caution that monitoring on such a scale in everyone is unnecessary and could even be counterproductive.

“Sending young athletes for extensive testing is not warranted and could send them to unnecessary testing, cardiac imaging, and so on,” Dr. Baggish said.

Only those athletes who continue to have symptoms or whose symptoms return when they get back to their athletic activities should go on for more screening.

“There, in essence, is the single main change from May, and that is a move away from screening with testing everyone, [and instead] confining that to the people who had moderate or greater severity disease,” he said.

Both iterations of the recommendations end with the same message.

“We are at the beginning of our knowledge about the cardiotoxic effects of COVID-19 but we are gathering evidence every day,” said Dr. Baggish. “Just as they did earlier, we acknowledge that our approaches are subject to change when we learn more about how COVID affects the heart, and specifically the hearts of athletes. This will be an ongoing process.”

Something to lean on

The recommendations are welcome, said James E. Udelson, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, coauthor of an accompanying editorial.

“It was a bit of the wild west out there, because each university, each college, all with good intentions, had been all struggling to figure out what to do, and how much to do. Probably the most important message from this new paper is the fact that now there is something out there that all coaches, athletes, families, schools, trainers can get some guidance from,” Dr. Udelson said in an interview.

Refining the cardiac screening criteria was a necessary step, Dr. Udelson said.

“How much cardiac imaging do you do? That is a matter of controversy,” said Dr. Udelson, who coauthored the commentary with Tufts cardiologist Ethan Rowin, MD, and Michael A. Curtis, MEd, a certified strength and conditioning specialist at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. “The problem is that if you use a very sensitive imaging test on a lot of people, sometimes you find things that you really didn’t need to know about. They’re really not important. And now, the athlete is told he or she cannot play for 3 months because they might have myocarditis.

“Should we be too sensitive, meaning do we want to pick up anything no matter whether it’s important or not?” he added. “There will be a lot of false positives, and we are going to disqualify a lot of people. Or do you tune it a different way?”

Dr. Udelson said he would like to see commercial sports donate money to support research into the potential cardiotoxicity of COVID-19.

“If the organizations that benefit from these athletes, like the National Collegiate Athletic Association and professional sports leagues, can fund some of this research, that would be a huge help,” Dr. Udelson said.

“These are the top sports cardiologists in the country, and they have to start somewhere, and these are all based on what we know right now, as well as their own extensive experience. We all know that we are just at the beginning of our knowledge of this. But we have to have something to guide this huge community out there that is really thirsty for help.”

Dr. Baggish reports receiving research funding for the study of athletes in competitive sports from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Football League Players Association; and the American Heart Association and receiving compensation for his role as team cardiologist from the US Olympic Committee/US Olympic Training Centers, US Soccer, US Rowing, the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, and Harvard University. Dr. Udelson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The latest recommendations from sports cardiologists on getting athletes with COVID-19 back on the playing field safely emphasize a more judicious approach to screening for cardiac injury.

The new recommendations, made by the American College of Cardiology’s Sports and Exercise Cardiology Section, are for adult athletes in competitive sports and also for two important groups: younger athletes taking part in competitive high school sports and older athletes aged 35 and older, the Masters athletes, who continue to be active throughout their lives. The document was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

Because of the evolving nature of knowledge about COVID-19, updates on recommendations for safe return to play for athletes of all ages will continue to be made, senior author Aaron L. Baggish, MD, director of the cardiovascular performance program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said.

“The recommendations we released in May were entirely based on our experience taking care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19; we had no athletes in this population. We used a lot of conservative guesswork around how this would apply to otherwise healthy athletes,” Dr. Baggish said in an interview.

“But as sports started to open up, and we started to see large numbers of first professional and then college athletes come back into training, we realized that we needed to stop and ask whether the recommendations we put forward back in May were still appropriate,” Dr. Baggish said.

“Once we started to actually get into the trenches with these athletes, literally hundreds of them, and applying the testing strategies that we had initially recommended in everybody, we realized that we probably had some room for improvement, and that’s why we reconvened, to make these revisions,” he said.

Essentially, the recommendations now urge less cardiac testing. “Cardiac injury is not as common as we may have originally thought,” said Dr. Baggish.

“In the early days of COVID, people who were hospitalized had evidence of heart injury, and so we wondered if that prevalence would also be applicable to otherwise young, healthy people who got COVID. If that had been the case, we would have been in big trouble with respect to getting people back into sports. So this is why we started with a conservative screening approach and a lot of testing in order to not miss a huge burden of disease,” he said.

“But what we’ve learned over the past few months is that young people who get either asymptomatic or mild infection appear to have very, very low risk of having associated heart injury, so the need for testing in that population, when people who have infections recover fully, is almost certainly not going to be high yield,” Dr. Baggish said.

First iteration of the recommendations

Published in May in the early weeks of the pandemic, the first recommendations for safe return to play said that all athletes should stop training for at least 2 weeks after their symptoms resolve, then undergo “careful, clinical cardiovascular evaluation in combination with cardiac biomarkers and imaging.”

Additional testing with cardiac MRI, exercise testing, or ambulatory rhythm monitoring was to be done “based on the clinical course and initial testing.”

But experts caution that monitoring on such a scale in everyone is unnecessary and could even be counterproductive.

“Sending young athletes for extensive testing is not warranted and could send them to unnecessary testing, cardiac imaging, and so on,” Dr. Baggish said.

Only those athletes who continue to have symptoms or whose symptoms return when they get back to their athletic activities should go on for more screening.

“There, in essence, is the single main change from May, and that is a move away from screening with testing everyone, [and instead] confining that to the people who had moderate or greater severity disease,” he said.

Both iterations of the recommendations end with the same message.

“We are at the beginning of our knowledge about the cardiotoxic effects of COVID-19 but we are gathering evidence every day,” said Dr. Baggish. “Just as they did earlier, we acknowledge that our approaches are subject to change when we learn more about how COVID affects the heart, and specifically the hearts of athletes. This will be an ongoing process.”

Something to lean on

The recommendations are welcome, said James E. Udelson, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, coauthor of an accompanying editorial.

“It was a bit of the wild west out there, because each university, each college, all with good intentions, had been all struggling to figure out what to do, and how much to do. Probably the most important message from this new paper is the fact that now there is something out there that all coaches, athletes, families, schools, trainers can get some guidance from,” Dr. Udelson said in an interview.

Refining the cardiac screening criteria was a necessary step, Dr. Udelson said.

“How much cardiac imaging do you do? That is a matter of controversy,” said Dr. Udelson, who coauthored the commentary with Tufts cardiologist Ethan Rowin, MD, and Michael A. Curtis, MEd, a certified strength and conditioning specialist at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. “The problem is that if you use a very sensitive imaging test on a lot of people, sometimes you find things that you really didn’t need to know about. They’re really not important. And now, the athlete is told he or she cannot play for 3 months because they might have myocarditis.

“Should we be too sensitive, meaning do we want to pick up anything no matter whether it’s important or not?” he added. “There will be a lot of false positives, and we are going to disqualify a lot of people. Or do you tune it a different way?”

Dr. Udelson said he would like to see commercial sports donate money to support research into the potential cardiotoxicity of COVID-19.

“If the organizations that benefit from these athletes, like the National Collegiate Athletic Association and professional sports leagues, can fund some of this research, that would be a huge help,” Dr. Udelson said.

“These are the top sports cardiologists in the country, and they have to start somewhere, and these are all based on what we know right now, as well as their own extensive experience. We all know that we are just at the beginning of our knowledge of this. But we have to have something to guide this huge community out there that is really thirsty for help.”

Dr. Baggish reports receiving research funding for the study of athletes in competitive sports from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Football League Players Association; and the American Heart Association and receiving compensation for his role as team cardiologist from the US Olympic Committee/US Olympic Training Centers, US Soccer, US Rowing, the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, and Harvard University. Dr. Udelson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AACE issues ‘cookbook’ algorithm to manage dyslipidemia

A new algorithm on lipid management and prevention of cardiovascular disease from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists* (AACE) and the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) is “a nice cookbook” that many clinicians, especially those who are not lipid experts, will find useful, according to writing committee chair Yehuda Handelsman, MD.

The algorithm, published Oct. 10 in Endocrine Practice as 10 slides, or as part of a more detailed consensus statement, is a companion to the 2017 AACE/ACE guidelines for lipid management and includes more recent information about new therapies.

“What we’re trying to do here is to say, ‘focus on LDL-C, triglycerides, high-risk patients, and lifestyle. Understand all the medications available to you to reduce LDL-C and reduce triglycerides,’ ” Dr. Handelsman, of the Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., explained in an interview.

“We touch on lipoprotein(a), which we still don’t have medication for, but it identifies people at high risk, and we need that.”

Clinicians also need to know “that we’ve got some newer drugs in the market that can manage people who have statin intolerance,” Dr. Handelsman added.

“We introduced new therapies like icosapent ethyl” (Vascepa, Amarin) for hypertriglyceridemia, “when to use it, and how to use it. Even though it was not part of the 2017 guideline, we gave recommendations based on current data in the algorithm.”

Although there is no good evidence that lowering triglycerides reduces heart disease, he continued, many experts believe that the target triglyceride level should be less than 150 mg/dL, and the algorithm explains how to treat to this goal.

“Last, and most importantly, I cannot fail to underscore the fact that lifestyle is very important,” he emphasized.

Robert H. Eckel, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and president of medicine and science at the American Diabetes Association, who was not involved with this algorithm, said in an interview that the algorithm is important since it offers “the clinician or health care practitioner an approach, a kind of a cookbook or application of the guidelines, for how to manage lipid disorders in patients at risk ... It’s geared for the nonexperts too,” he said.

Dyslipidemia treatment summarized in 10 slides

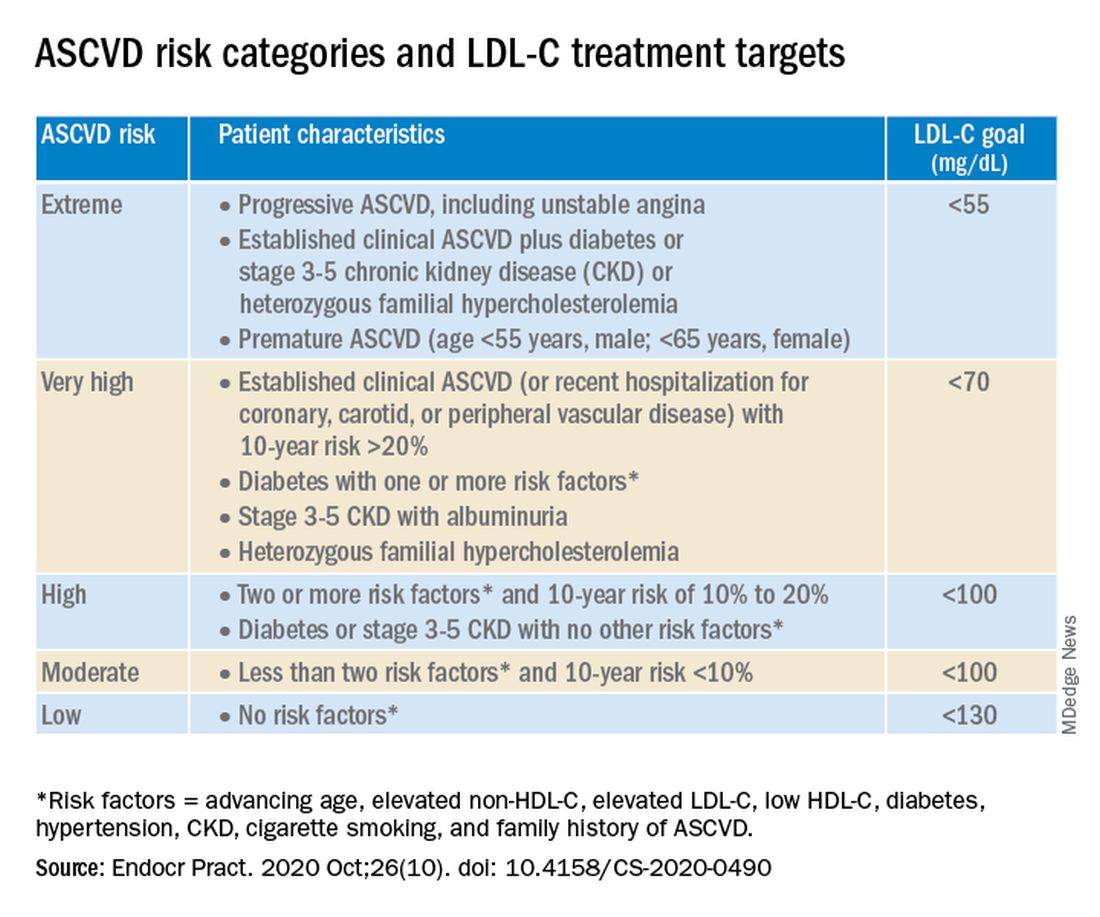

The AACE/ACE algorithm comprises 10 slides, one each for dyslipidemic states, secondary causes of lipid disorders, screening for and assessing lipid disorders and atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk, ASCVD risk categories and treatment goals, lifestyle recommendations, treating LDL-C to goal, managing statin intolerance and safety, management of hypertriglyceridemia and the role of icosapent ethyl, assessment and management of elevated lipoprotein(a), and profiles of medications for dyslipidemia.

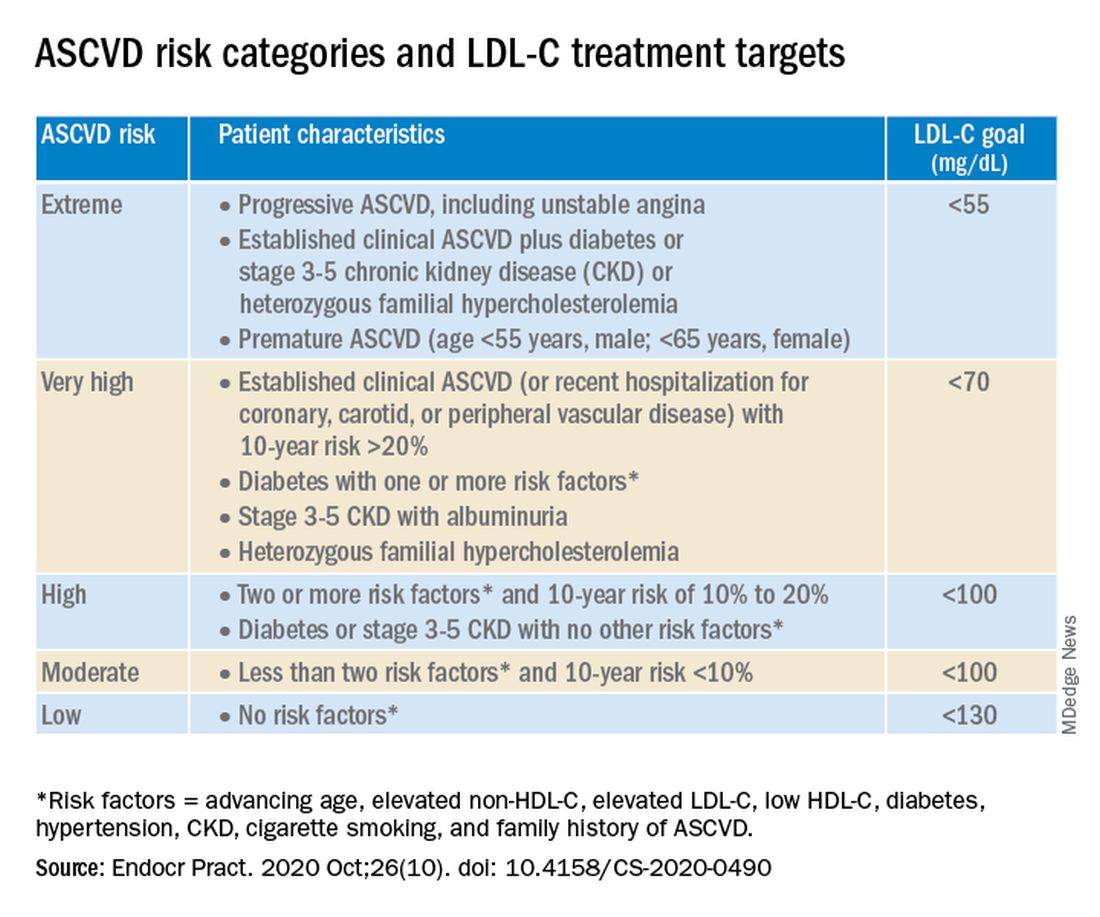

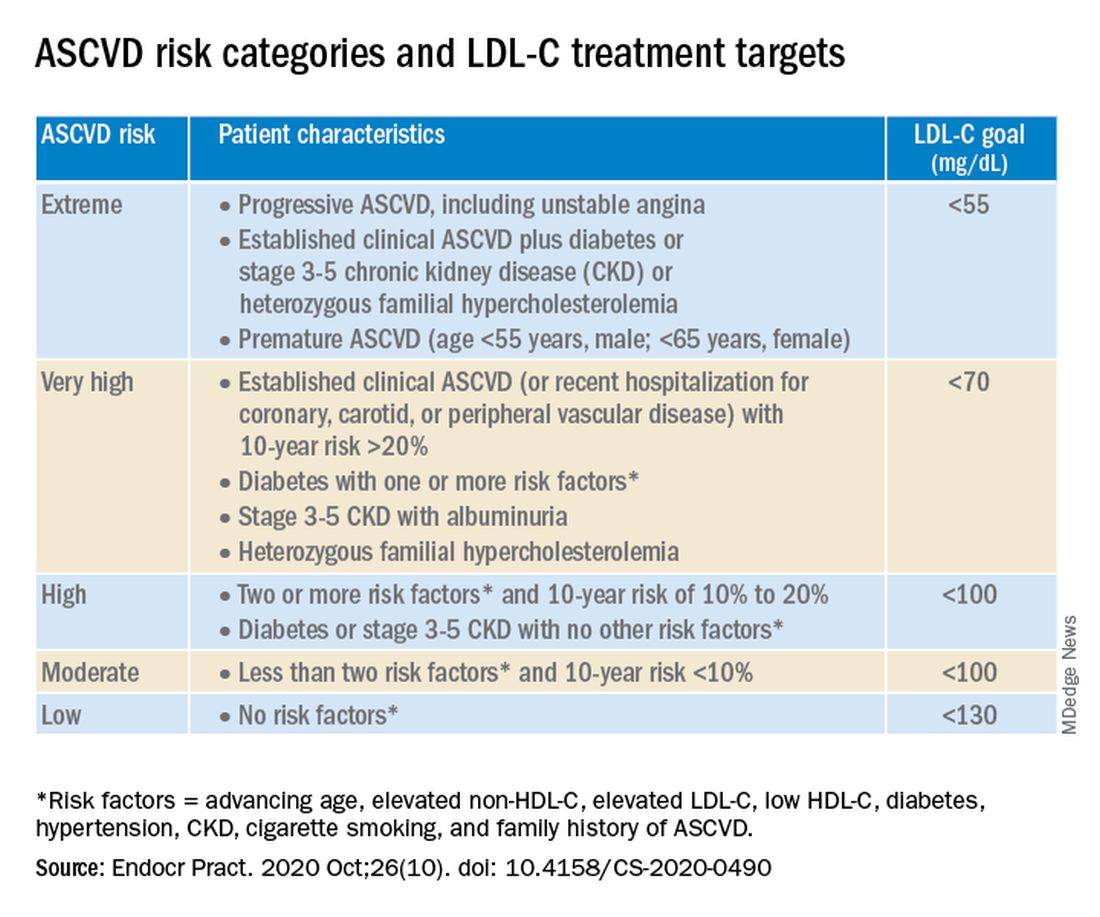

The algorithm defines five ASCVD risk categories and recommends increasingly lower LDL-C, non–HDL-C, and apo B target levels with increasing risk, but the same triglyceride target for all.

First, “treatment of lipid disorders begins with lifestyle therapy to improve nutrition, physical activity, weight, and other factors that affect lipids,” the consensus statement authors stress.

Next, “LDL-C has been, and remains, the main focus of efforts to improve lipid profiles in individuals at risk for ASCVD” (see table).

“We stratify [LDL-C] not as a one-treatment-target-for-all,” but rather as extreme, very high, high, moderate, and low ASCVD risk, Dr. Handelsman explained, with different treatment pathways (specified in another slide) to reach different risk-dependent goals.

“Unlike the ACC [American College of Cardiology] guideline, which shows if you want to further reduce LDL after statin give ezetimibe first, we say ‘no’,” he noted. “If somebody has an extreme risk, and you don’t think ezetimibe will get to a goal below 55 mg/dL, you should go first with a PCSK9 [proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9] inhibitor, and only then add ezetimibe or [colesevelam] or other drugs,” he said.

The consensus statement authors expand on this scenario. “Treatment for patients at extreme risk should begin with lifestyle therapy plus a high-intensity statin (atorvastatin 40 to 80 mg or rosuvastatin 20 to 40 mg, or the highest tolerated statin dose) to achieve an LDL-C goal of less than 55 mg/dL.”

“If LDL-C remains above goal after 3 months,” a PCSK9 inhibitor (evolocumab [Repatha, Amgen] or alirocumab [Praluent, Sanofi/Regeneron]), the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe, or the bile acid sequestrant colesevelam (Welchol, Daiichi Sankyo) or the adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase (ACL) inhibitor bempedoic acid (Nexletol, Esperion) “should be added, depending on required LDL-C lowering, and a third agent should be added if the combination fails to achieve the goal.”

However, “because the cost of ezetimibe is low, it may be preferred over PCSK9 inhibitors as second-line therapy to achieve an LDL-C below 70 mg/dL for patients who require no more than 15%-20% further reduction to reach goals.”

For patients at moderate or high risk, lipid management should begin with a moderate-intensity statin and be increased to a high-intensity statin before adding a second lipid-lowering medication to reach an LDL-C below 100 mg/dL.

According to the consensus statement, the desirable goal for triglycerides is less than 150 mg/dL.

In all patients with triglyceride levels of at least 500 mg/dL, statin therapy should be combined with a fibrate, prescription-grade omega-3 fatty acid, and/or niacin to reduce triglycerides.

In any patient with established ASCVD or diabetes with at least 2 ASCVD risk factors and triglycerides of 135-499 mg/dL, icosapent ethyl should be added to a statin to prevent ASCVD events.

Statement aligns with major guidelines

In general, the 2017 AACE/ACE guidelines and algorithm are “pretty similar” to other guidelines such as the 2018 ACC/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cholesterol management, the 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines for primary prevention of CVD, and the 2019 European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia, according to Dr. Eckel.

They have “all have now taken into consideration the evidence behind PCSK9 inhibitors,” he noted. “That’s important because those drugs have proven to be effective.”

Two differences, he pointed out, are that the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines suggest that lipoprotein(a) measurement be considered at least once in every adult’s lifetime, and they recommend apo B analysis in people with high triglycerides but normal LDL (or no higher than 100 mg/dL), to identify additional risk.

*AACE changes its name, broadens focus

Shortly after its algorithm was published, AACE announced that it has a new organization name and brand, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, which “more clearly defines AACE as a community of individuals who work together to elevate the practice of clinical endocrinology,” according to an Oct. 20 statement.

The change is meant to acknowledge AACE’s “more modern, inclusive approach to endocrinology that supports multidisciplinary care teams – with endocrinologists leading the way.”

Along with the name change is a new global website. The statement notes that “health care professionals and community members can access all of the valuable clinical content such as guidelines, disease state networks and important education by visiting the pro portal in the top right corner of the site, or by going directly to pro.aace.com.”

Dr. Handelsman discloses that he receives research grant support from Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Gan & Lee, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, and he is a consultant and/or speaker for Amarin, BI-Lilly, and Sanofi.

Dr. Eckel has received consultant/advisory board fees from Kowa, Novo Nordisk, and Provention Bio.

A new algorithm on lipid management and prevention of cardiovascular disease from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists* (AACE) and the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) is “a nice cookbook” that many clinicians, especially those who are not lipid experts, will find useful, according to writing committee chair Yehuda Handelsman, MD.

The algorithm, published Oct. 10 in Endocrine Practice as 10 slides, or as part of a more detailed consensus statement, is a companion to the 2017 AACE/ACE guidelines for lipid management and includes more recent information about new therapies.

“What we’re trying to do here is to say, ‘focus on LDL-C, triglycerides, high-risk patients, and lifestyle. Understand all the medications available to you to reduce LDL-C and reduce triglycerides,’ ” Dr. Handelsman, of the Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., explained in an interview.

“We touch on lipoprotein(a), which we still don’t have medication for, but it identifies people at high risk, and we need that.”

Clinicians also need to know “that we’ve got some newer drugs in the market that can manage people who have statin intolerance,” Dr. Handelsman added.

“We introduced new therapies like icosapent ethyl” (Vascepa, Amarin) for hypertriglyceridemia, “when to use it, and how to use it. Even though it was not part of the 2017 guideline, we gave recommendations based on current data in the algorithm.”

Although there is no good evidence that lowering triglycerides reduces heart disease, he continued, many experts believe that the target triglyceride level should be less than 150 mg/dL, and the algorithm explains how to treat to this goal.

“Last, and most importantly, I cannot fail to underscore the fact that lifestyle is very important,” he emphasized.

Robert H. Eckel, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and president of medicine and science at the American Diabetes Association, who was not involved with this algorithm, said in an interview that the algorithm is important since it offers “the clinician or health care practitioner an approach, a kind of a cookbook or application of the guidelines, for how to manage lipid disorders in patients at risk ... It’s geared for the nonexperts too,” he said.

Dyslipidemia treatment summarized in 10 slides

The AACE/ACE algorithm comprises 10 slides, one each for dyslipidemic states, secondary causes of lipid disorders, screening for and assessing lipid disorders and atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk, ASCVD risk categories and treatment goals, lifestyle recommendations, treating LDL-C to goal, managing statin intolerance and safety, management of hypertriglyceridemia and the role of icosapent ethyl, assessment and management of elevated lipoprotein(a), and profiles of medications for dyslipidemia.

The algorithm defines five ASCVD risk categories and recommends increasingly lower LDL-C, non–HDL-C, and apo B target levels with increasing risk, but the same triglyceride target for all.

First, “treatment of lipid disorders begins with lifestyle therapy to improve nutrition, physical activity, weight, and other factors that affect lipids,” the consensus statement authors stress.

Next, “LDL-C has been, and remains, the main focus of efforts to improve lipid profiles in individuals at risk for ASCVD” (see table).

“We stratify [LDL-C] not as a one-treatment-target-for-all,” but rather as extreme, very high, high, moderate, and low ASCVD risk, Dr. Handelsman explained, with different treatment pathways (specified in another slide) to reach different risk-dependent goals.

“Unlike the ACC [American College of Cardiology] guideline, which shows if you want to further reduce LDL after statin give ezetimibe first, we say ‘no’,” he noted. “If somebody has an extreme risk, and you don’t think ezetimibe will get to a goal below 55 mg/dL, you should go first with a PCSK9 [proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9] inhibitor, and only then add ezetimibe or [colesevelam] or other drugs,” he said.

The consensus statement authors expand on this scenario. “Treatment for patients at extreme risk should begin with lifestyle therapy plus a high-intensity statin (atorvastatin 40 to 80 mg or rosuvastatin 20 to 40 mg, or the highest tolerated statin dose) to achieve an LDL-C goal of less than 55 mg/dL.”

“If LDL-C remains above goal after 3 months,” a PCSK9 inhibitor (evolocumab [Repatha, Amgen] or alirocumab [Praluent, Sanofi/Regeneron]), the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe, or the bile acid sequestrant colesevelam (Welchol, Daiichi Sankyo) or the adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase (ACL) inhibitor bempedoic acid (Nexletol, Esperion) “should be added, depending on required LDL-C lowering, and a third agent should be added if the combination fails to achieve the goal.”

However, “because the cost of ezetimibe is low, it may be preferred over PCSK9 inhibitors as second-line therapy to achieve an LDL-C below 70 mg/dL for patients who require no more than 15%-20% further reduction to reach goals.”

For patients at moderate or high risk, lipid management should begin with a moderate-intensity statin and be increased to a high-intensity statin before adding a second lipid-lowering medication to reach an LDL-C below 100 mg/dL.

According to the consensus statement, the desirable goal for triglycerides is less than 150 mg/dL.

In all patients with triglyceride levels of at least 500 mg/dL, statin therapy should be combined with a fibrate, prescription-grade omega-3 fatty acid, and/or niacin to reduce triglycerides.

In any patient with established ASCVD or diabetes with at least 2 ASCVD risk factors and triglycerides of 135-499 mg/dL, icosapent ethyl should be added to a statin to prevent ASCVD events.

Statement aligns with major guidelines

In general, the 2017 AACE/ACE guidelines and algorithm are “pretty similar” to other guidelines such as the 2018 ACC/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cholesterol management, the 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines for primary prevention of CVD, and the 2019 European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia, according to Dr. Eckel.

They have “all have now taken into consideration the evidence behind PCSK9 inhibitors,” he noted. “That’s important because those drugs have proven to be effective.”

Two differences, he pointed out, are that the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines suggest that lipoprotein(a) measurement be considered at least once in every adult’s lifetime, and they recommend apo B analysis in people with high triglycerides but normal LDL (or no higher than 100 mg/dL), to identify additional risk.

*AACE changes its name, broadens focus

Shortly after its algorithm was published, AACE announced that it has a new organization name and brand, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, which “more clearly defines AACE as a community of individuals who work together to elevate the practice of clinical endocrinology,” according to an Oct. 20 statement.

The change is meant to acknowledge AACE’s “more modern, inclusive approach to endocrinology that supports multidisciplinary care teams – with endocrinologists leading the way.”

Along with the name change is a new global website. The statement notes that “health care professionals and community members can access all of the valuable clinical content such as guidelines, disease state networks and important education by visiting the pro portal in the top right corner of the site, or by going directly to pro.aace.com.”

Dr. Handelsman discloses that he receives research grant support from Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Gan & Lee, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, and he is a consultant and/or speaker for Amarin, BI-Lilly, and Sanofi.

Dr. Eckel has received consultant/advisory board fees from Kowa, Novo Nordisk, and Provention Bio.

A new algorithm on lipid management and prevention of cardiovascular disease from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists* (AACE) and the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) is “a nice cookbook” that many clinicians, especially those who are not lipid experts, will find useful, according to writing committee chair Yehuda Handelsman, MD.

The algorithm, published Oct. 10 in Endocrine Practice as 10 slides, or as part of a more detailed consensus statement, is a companion to the 2017 AACE/ACE guidelines for lipid management and includes more recent information about new therapies.

“What we’re trying to do here is to say, ‘focus on LDL-C, triglycerides, high-risk patients, and lifestyle. Understand all the medications available to you to reduce LDL-C and reduce triglycerides,’ ” Dr. Handelsman, of the Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., explained in an interview.

“We touch on lipoprotein(a), which we still don’t have medication for, but it identifies people at high risk, and we need that.”

Clinicians also need to know “that we’ve got some newer drugs in the market that can manage people who have statin intolerance,” Dr. Handelsman added.

“We introduced new therapies like icosapent ethyl” (Vascepa, Amarin) for hypertriglyceridemia, “when to use it, and how to use it. Even though it was not part of the 2017 guideline, we gave recommendations based on current data in the algorithm.”

Although there is no good evidence that lowering triglycerides reduces heart disease, he continued, many experts believe that the target triglyceride level should be less than 150 mg/dL, and the algorithm explains how to treat to this goal.

“Last, and most importantly, I cannot fail to underscore the fact that lifestyle is very important,” he emphasized.

Robert H. Eckel, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and president of medicine and science at the American Diabetes Association, who was not involved with this algorithm, said in an interview that the algorithm is important since it offers “the clinician or health care practitioner an approach, a kind of a cookbook or application of the guidelines, for how to manage lipid disorders in patients at risk ... It’s geared for the nonexperts too,” he said.

Dyslipidemia treatment summarized in 10 slides

The AACE/ACE algorithm comprises 10 slides, one each for dyslipidemic states, secondary causes of lipid disorders, screening for and assessing lipid disorders and atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk, ASCVD risk categories and treatment goals, lifestyle recommendations, treating LDL-C to goal, managing statin intolerance and safety, management of hypertriglyceridemia and the role of icosapent ethyl, assessment and management of elevated lipoprotein(a), and profiles of medications for dyslipidemia.

The algorithm defines five ASCVD risk categories and recommends increasingly lower LDL-C, non–HDL-C, and apo B target levels with increasing risk, but the same triglyceride target for all.

First, “treatment of lipid disorders begins with lifestyle therapy to improve nutrition, physical activity, weight, and other factors that affect lipids,” the consensus statement authors stress.

Next, “LDL-C has been, and remains, the main focus of efforts to improve lipid profiles in individuals at risk for ASCVD” (see table).

“We stratify [LDL-C] not as a one-treatment-target-for-all,” but rather as extreme, very high, high, moderate, and low ASCVD risk, Dr. Handelsman explained, with different treatment pathways (specified in another slide) to reach different risk-dependent goals.

“Unlike the ACC [American College of Cardiology] guideline, which shows if you want to further reduce LDL after statin give ezetimibe first, we say ‘no’,” he noted. “If somebody has an extreme risk, and you don’t think ezetimibe will get to a goal below 55 mg/dL, you should go first with a PCSK9 [proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9] inhibitor, and only then add ezetimibe or [colesevelam] or other drugs,” he said.

The consensus statement authors expand on this scenario. “Treatment for patients at extreme risk should begin with lifestyle therapy plus a high-intensity statin (atorvastatin 40 to 80 mg or rosuvastatin 20 to 40 mg, or the highest tolerated statin dose) to achieve an LDL-C goal of less than 55 mg/dL.”

“If LDL-C remains above goal after 3 months,” a PCSK9 inhibitor (evolocumab [Repatha, Amgen] or alirocumab [Praluent, Sanofi/Regeneron]), the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe, or the bile acid sequestrant colesevelam (Welchol, Daiichi Sankyo) or the adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase (ACL) inhibitor bempedoic acid (Nexletol, Esperion) “should be added, depending on required LDL-C lowering, and a third agent should be added if the combination fails to achieve the goal.”

However, “because the cost of ezetimibe is low, it may be preferred over PCSK9 inhibitors as second-line therapy to achieve an LDL-C below 70 mg/dL for patients who require no more than 15%-20% further reduction to reach goals.”

For patients at moderate or high risk, lipid management should begin with a moderate-intensity statin and be increased to a high-intensity statin before adding a second lipid-lowering medication to reach an LDL-C below 100 mg/dL.

According to the consensus statement, the desirable goal for triglycerides is less than 150 mg/dL.

In all patients with triglyceride levels of at least 500 mg/dL, statin therapy should be combined with a fibrate, prescription-grade omega-3 fatty acid, and/or niacin to reduce triglycerides.

In any patient with established ASCVD or diabetes with at least 2 ASCVD risk factors and triglycerides of 135-499 mg/dL, icosapent ethyl should be added to a statin to prevent ASCVD events.

Statement aligns with major guidelines

In general, the 2017 AACE/ACE guidelines and algorithm are “pretty similar” to other guidelines such as the 2018 ACC/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cholesterol management, the 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines for primary prevention of CVD, and the 2019 European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia, according to Dr. Eckel.

They have “all have now taken into consideration the evidence behind PCSK9 inhibitors,” he noted. “That’s important because those drugs have proven to be effective.”

Two differences, he pointed out, are that the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines suggest that lipoprotein(a) measurement be considered at least once in every adult’s lifetime, and they recommend apo B analysis in people with high triglycerides but normal LDL (or no higher than 100 mg/dL), to identify additional risk.

*AACE changes its name, broadens focus

Shortly after its algorithm was published, AACE announced that it has a new organization name and brand, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, which “more clearly defines AACE as a community of individuals who work together to elevate the practice of clinical endocrinology,” according to an Oct. 20 statement.

The change is meant to acknowledge AACE’s “more modern, inclusive approach to endocrinology that supports multidisciplinary care teams – with endocrinologists leading the way.”

Along with the name change is a new global website. The statement notes that “health care professionals and community members can access all of the valuable clinical content such as guidelines, disease state networks and important education by visiting the pro portal in the top right corner of the site, or by going directly to pro.aace.com.”

Dr. Handelsman discloses that he receives research grant support from Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Gan & Lee, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, and he is a consultant and/or speaker for Amarin, BI-Lilly, and Sanofi.

Dr. Eckel has received consultant/advisory board fees from Kowa, Novo Nordisk, and Provention Bio.

Higher serum omega-3 tied to better outcome after STEMI

Regular consumption of foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids was associated with improved prognosis after ST-segment myocardial infarction (STEMI) in a new observational study.

The prospective study, which involved 944 patients with STEMI who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), showed that plasma levels of fatty acids at the time of the STEMI were inversely associated with both incident major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and cardiovascular readmissions (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 and 0.74 for 1-SD increase; for both, P < .05).

No association was seen for the endpoint of all-cause mortality.

“What we showed is that your consumption of fish and other sources of omega-3 fatty acids before the heart attack impacts your prognosis after the heart attack. It’s a novel approach because it’s not primary prevention or secondary prevention,” said Aleix Sala-Vila, PharmD, PhD, from the Institut Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mèdiques (IMIM) in Barcelona, Spain.

Sala-Vila, co–senior author Antoni Bayés-Genís, MD, PhD, Heart Universitari Germans Trias I Pujol, Barcelona, and first author Iolanda Lázaro, PhD, also from IMIM, reported their findings online Oct. 26 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It has been established that dietary omega-3 eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) has cardioprotective properties, but observational studies and randomized trials of EPA intake have yielded disparate findings.

This study avoided the usual traps of nutritional epidemiology research – self-reported food diaries and intake questionnaires. For this study, the researchers measured tissue levels of EPA and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) by measuring serum phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels, which reflect dietary intake during the previous 3 or 4 weeks.

This technique, said Sala-Vila, not only provides a more reliable measure of fatty acid intake over time but also avoids measurement errors related to fatty acid content variation.

For example, “The EPA content of a piece of fish eaten in January could be very different from one eaten in June,” explained Sala-Vila.

That said, he acknowledged that this technique, which uses gas chromatography, does not at present have a clear clinical application. “It’s quite difficult just to convert levels of serum-PC EPA into consumption of fatty fish. We feel that the best advice at this point is that given by the American Heart Association to eat two servings of fatty fish a week.”

EPA and ALA: Partners in prevention?

In addition to the findings regarding EPA, the researchers also found that serum-PC ALA was inversely related to all-cause mortality after STEMI (HR, 0.65 for 1-SD increase; P < .05).

A trend was seen for an association between ALA and lower risk for incident MACE (P = .093).

ALA is readily available from inexpensive plant sources (eg, chia seeds, flax seeds, walnuts, soy beans) and has been associated with lower all-cause mortality in high-risk individuals.

This omega-3 fatty acid is often given short shrift in the fatty acid world because of the seven-step enzymatic process needed to convert it into more beneficial forms.

“We know that the conversion of ALA to EPA or DHA [docohexaenoic acid] is marginal, but we decided to include it in the study because we feel that this fatty acid is becoming more important because there are some issues with fish consumption – people are concerned about pollutants and sustainability, and some just don’t like it,” explained Sala-Vila.

“We were shocked to see that the marine-derived and vegetable-derived fatty acids don’t appear to compete, but rather they act synergistically,” said Sala-Villa. The researchers suggested that marine and vegetable omega-3 fatty acids may act as “partners in prevention.”

“We are not metabolically adapted to converting ALA to EPA, but despite this, there is a large body of evidence showing that one way to increase the status of EPA and DHA in our membranes is by eating these sources of fatty acids,” said Sala-Vila.

For almost 20 years, Sala-Vila has been studying how the consumption of foods rich in omega-3 affects disease. Two of his current projects involve studying levels of ALA in red blood cell membranes as a risk factor for ischemic stroke and omega-3 status in individuals with cognitive impairment who are at high risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Applicable to all patients with atherosclerosis

In comments to theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, Deepak Bhatt, MD, called the study “terrific,” adding that the effort is “as good as it gets” for observational nutrition research.

“I think one has to view these findings in the larger universe of what is really a revolution in omega-3 fatty acid research,” said Bhatt.

This universe, he said, includes a wealth of observational research showing the benefits of omega-3s, two outcome trials – JELIS and REDUCE-IT – that showed the benefits of EPA supplementation, and two imaging studies – EVAPORATE and CHERRY – that showed favorable effects of EPA on the vasculature.

REDUCE-IT, for which Bhatt served as principal investigator, showed that treatment with icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), a high-dose purified form of EPA, led to a 25% relative risk reduction in MACE in an at-risk Western population.

The results, said Bhatt, who co-wrote an editorial that accompanies the current Sala-Vila article, “likely apply to all patients with atherosclerosis or who are at high risk for it” and supports the practice of counseling patients to increase their intake of food rich in omega-3 fatty acids.

The field may be due for a shake-up, he noted. At next month’s American Heart Association meeting, the results of another trial of another prescription-grade EPA/DHA supplement will be presented, and they are expected to be negative.

AstraZeneca announced in January 2020 the early closure of the STRENGTH trial of Epanova after an interim analysis showed a low likelihood of their product demonstrating benefit in the enrolled population.

Epanova is a fish-oil derived mixture of free fatty acids, primarily EPA and DHA. It is approved in the United States and is indicated as an adjunct to diet to reduce triglyceride levels in adults with severe (≥500 mg/dL) hypertriglyceridemia. This indication is not affected by the data from the STRENGTH trial, according to a company press release.

Sala-Vila has received grants and support from the California Walnut Commission, including a grant to support part of this study. Bayés-Genís and Bhatt have relationships with a number of companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Regular consumption of foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids was associated with improved prognosis after ST-segment myocardial infarction (STEMI) in a new observational study.

The prospective study, which involved 944 patients with STEMI who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), showed that plasma levels of fatty acids at the time of the STEMI were inversely associated with both incident major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and cardiovascular readmissions (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 and 0.74 for 1-SD increase; for both, P < .05).

No association was seen for the endpoint of all-cause mortality.

“What we showed is that your consumption of fish and other sources of omega-3 fatty acids before the heart attack impacts your prognosis after the heart attack. It’s a novel approach because it’s not primary prevention or secondary prevention,” said Aleix Sala-Vila, PharmD, PhD, from the Institut Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mèdiques (IMIM) in Barcelona, Spain.

Sala-Vila, co–senior author Antoni Bayés-Genís, MD, PhD, Heart Universitari Germans Trias I Pujol, Barcelona, and first author Iolanda Lázaro, PhD, also from IMIM, reported their findings online Oct. 26 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It has been established that dietary omega-3 eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) has cardioprotective properties, but observational studies and randomized trials of EPA intake have yielded disparate findings.

This study avoided the usual traps of nutritional epidemiology research – self-reported food diaries and intake questionnaires. For this study, the researchers measured tissue levels of EPA and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) by measuring serum phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels, which reflect dietary intake during the previous 3 or 4 weeks.

This technique, said Sala-Vila, not only provides a more reliable measure of fatty acid intake over time but also avoids measurement errors related to fatty acid content variation.

For example, “The EPA content of a piece of fish eaten in January could be very different from one eaten in June,” explained Sala-Vila.

That said, he acknowledged that this technique, which uses gas chromatography, does not at present have a clear clinical application. “It’s quite difficult just to convert levels of serum-PC EPA into consumption of fatty fish. We feel that the best advice at this point is that given by the American Heart Association to eat two servings of fatty fish a week.”

EPA and ALA: Partners in prevention?

In addition to the findings regarding EPA, the researchers also found that serum-PC ALA was inversely related to all-cause mortality after STEMI (HR, 0.65 for 1-SD increase; P < .05).

A trend was seen for an association between ALA and lower risk for incident MACE (P = .093).

ALA is readily available from inexpensive plant sources (eg, chia seeds, flax seeds, walnuts, soy beans) and has been associated with lower all-cause mortality in high-risk individuals.

This omega-3 fatty acid is often given short shrift in the fatty acid world because of the seven-step enzymatic process needed to convert it into more beneficial forms.

“We know that the conversion of ALA to EPA or DHA [docohexaenoic acid] is marginal, but we decided to include it in the study because we feel that this fatty acid is becoming more important because there are some issues with fish consumption – people are concerned about pollutants and sustainability, and some just don’t like it,” explained Sala-Vila.

“We were shocked to see that the marine-derived and vegetable-derived fatty acids don’t appear to compete, but rather they act synergistically,” said Sala-Villa. The researchers suggested that marine and vegetable omega-3 fatty acids may act as “partners in prevention.”

“We are not metabolically adapted to converting ALA to EPA, but despite this, there is a large body of evidence showing that one way to increase the status of EPA and DHA in our membranes is by eating these sources of fatty acids,” said Sala-Vila.

For almost 20 years, Sala-Vila has been studying how the consumption of foods rich in omega-3 affects disease. Two of his current projects involve studying levels of ALA in red blood cell membranes as a risk factor for ischemic stroke and omega-3 status in individuals with cognitive impairment who are at high risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Applicable to all patients with atherosclerosis

In comments to theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, Deepak Bhatt, MD, called the study “terrific,” adding that the effort is “as good as it gets” for observational nutrition research.

“I think one has to view these findings in the larger universe of what is really a revolution in omega-3 fatty acid research,” said Bhatt.

This universe, he said, includes a wealth of observational research showing the benefits of omega-3s, two outcome trials – JELIS and REDUCE-IT – that showed the benefits of EPA supplementation, and two imaging studies – EVAPORATE and CHERRY – that showed favorable effects of EPA on the vasculature.

REDUCE-IT, for which Bhatt served as principal investigator, showed that treatment with icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), a high-dose purified form of EPA, led to a 25% relative risk reduction in MACE in an at-risk Western population.

The results, said Bhatt, who co-wrote an editorial that accompanies the current Sala-Vila article, “likely apply to all patients with atherosclerosis or who are at high risk for it” and supports the practice of counseling patients to increase their intake of food rich in omega-3 fatty acids.