User login

Triglyceride puzzle: Do TG metabolites better predict risk?

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

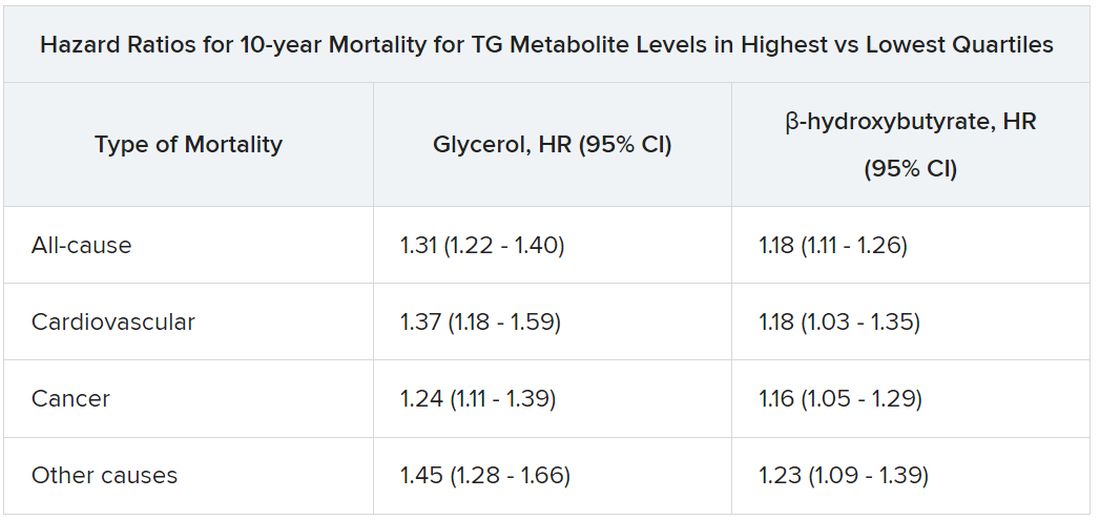

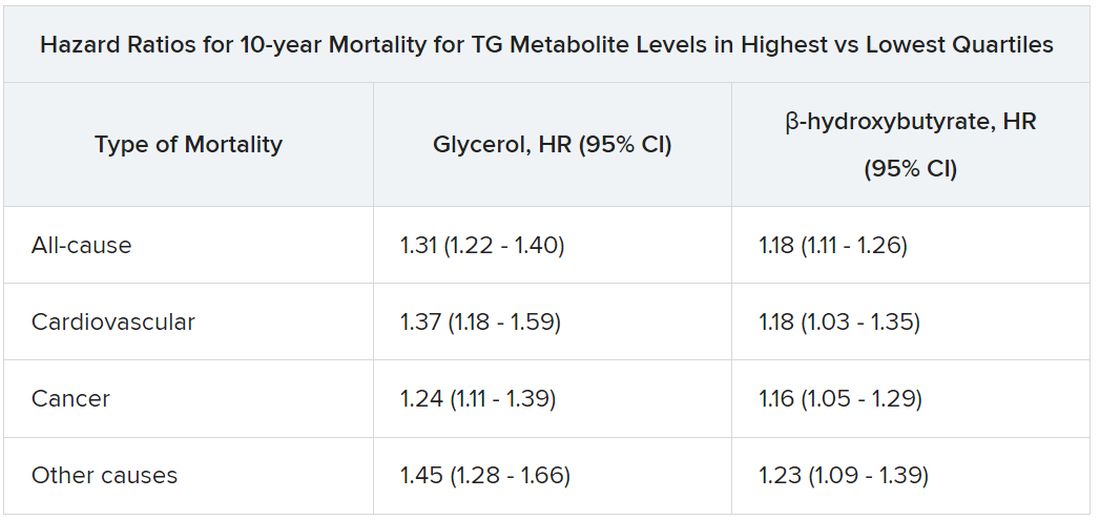

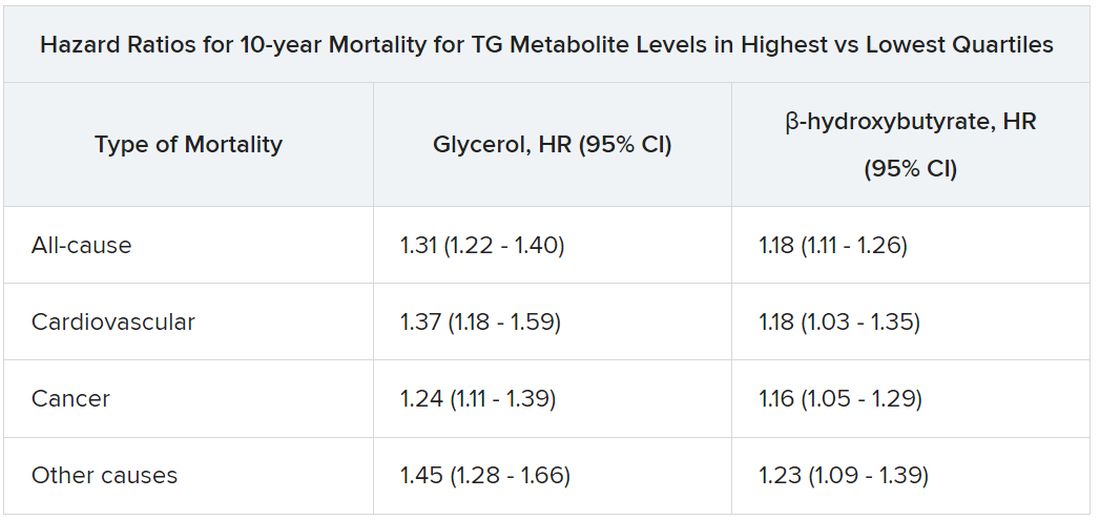

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

‘Water fasting’ benefits don’t last

Health benefits of prolonged “water fasting” (zero calories) or Buchinger fasting (200-300 calories/day) don’t last, according to authors of a review of eight studies.

Five days of fasting lowered weight by about 6%, but this weight was regained after 3 months of regular eating, the investigators found. The article was published in Nutrition Reviews.

“Water fasting led to improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels, but these were short-lived,” senior author Krista A. Varady, PhD, told this news organization.

“Levels returned to baseline ... quickly after participants started eating. Most benefits disappeared in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Varady, professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

“My overall conclusion,” she said, “is that I guess you could try it, but it just seems like a lot of work, and all those metabolic benefits disappear. I would encourage someone hoping to lose weight to try intermittent fasting instead of water fasting, because there’s a lot more data to show it can help with weight management.

“People should consult their doctor if they have diabetes or any other major obesity-related conditions before doing water fasting,” Dr. Varady cautioned.

“Healthy people with obesity can probably fast safely for 5 days on their own (if they don’t have any other conditions). However, no one should undertake one of these fasts for more than 5 days without medical supervision,” she stressed.

Eight studies of water and Buchinger fasting

Although several favorable effects of prolonged fasting have been observed, benefits must be weighed against risks, Dr. Varady and her coauthors wrote.

Most medically supervised fasting programs have reported only minor adverse events, which included hunger, headaches, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, and fatigue. However, more severe events have been documented, including edema, abnormal results on liver function tests, decreased bone density, and metabolic acidosis.

The researchers aimed to determine the effect of prolonged fasting on weight, blood pressure, lipid levels, and glycemic control, as well as safety and the effects of refeeding.

They examined two types of prolonged fasting: water fasting and Buchinger fasting, which involves consuming 250 mL of fruit or vegetable juice for lunch and 250 mL of soup for dinner every day of the 5- to 20-day fast.

Buchinger fasting is popular in Central Europe. Water fasting “institutes” exist in the United States, such as one in California, Dr. Varady noted.

The researchers excluded fasting during Ramadan or fasting practiced by Seventh Day Adventists.

They identified four studies of water fasting and four studies of Buchinger fasting (of which one study of 1,422 participants assessed fasting for 5, 10, 15, and 20 days).

The review showed that prolonged fasting for 5-20 days produced large increases in circulating ketones, weight loss of 2%-10%, and decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

People who fasted 5 days typically lost 4%-6% of their weight; those who fasted 7-10 days lost 2%-10% of their weight; and those who fasted 15-20 days lost 7%-10% of their weight.

LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels decreased in some trials.

Fasting glucose levels, fasting insulin levels, insulin resistance, and A1c decreased in adults without diabetes but remained unchanged in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Some participants experienced metabolic acidosis, headaches, insomnia, or hunger.

About two-thirds of the weight lost was of lean mass, and one-third was of fat mass. The loss of lean mass loss suggests that prolonged fasting may increase the breakdown of muscle proteins, which is a concern, the researchers noted.

Few of the trials examined the effects of refeeding. In one study, normal-weight adults lost 6% of their weight after 5 days of water-only fasting but then gained it all back after 3 months of eating regularly.

In three trials, participants regained 1%-2% of their weight 2-4 months after fasting; however, those trials instructed participants to follow a calorie-restricted diet during the refeeding period.

Three to 4 months after the fast was completed, none of the metabolic benefits were maintained, even when weight loss was maintained.

The study did not receive external funding. Dr. Varady has received author fees from Hachette Book Group for “The Every Other Day Diet” and from Pan Macmillan Press for “The Fastest Diet.” The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Health benefits of prolonged “water fasting” (zero calories) or Buchinger fasting (200-300 calories/day) don’t last, according to authors of a review of eight studies.

Five days of fasting lowered weight by about 6%, but this weight was regained after 3 months of regular eating, the investigators found. The article was published in Nutrition Reviews.

“Water fasting led to improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels, but these were short-lived,” senior author Krista A. Varady, PhD, told this news organization.

“Levels returned to baseline ... quickly after participants started eating. Most benefits disappeared in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Varady, professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

“My overall conclusion,” she said, “is that I guess you could try it, but it just seems like a lot of work, and all those metabolic benefits disappear. I would encourage someone hoping to lose weight to try intermittent fasting instead of water fasting, because there’s a lot more data to show it can help with weight management.

“People should consult their doctor if they have diabetes or any other major obesity-related conditions before doing water fasting,” Dr. Varady cautioned.

“Healthy people with obesity can probably fast safely for 5 days on their own (if they don’t have any other conditions). However, no one should undertake one of these fasts for more than 5 days without medical supervision,” she stressed.

Eight studies of water and Buchinger fasting

Although several favorable effects of prolonged fasting have been observed, benefits must be weighed against risks, Dr. Varady and her coauthors wrote.

Most medically supervised fasting programs have reported only minor adverse events, which included hunger, headaches, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, and fatigue. However, more severe events have been documented, including edema, abnormal results on liver function tests, decreased bone density, and metabolic acidosis.

The researchers aimed to determine the effect of prolonged fasting on weight, blood pressure, lipid levels, and glycemic control, as well as safety and the effects of refeeding.

They examined two types of prolonged fasting: water fasting and Buchinger fasting, which involves consuming 250 mL of fruit or vegetable juice for lunch and 250 mL of soup for dinner every day of the 5- to 20-day fast.

Buchinger fasting is popular in Central Europe. Water fasting “institutes” exist in the United States, such as one in California, Dr. Varady noted.

The researchers excluded fasting during Ramadan or fasting practiced by Seventh Day Adventists.

They identified four studies of water fasting and four studies of Buchinger fasting (of which one study of 1,422 participants assessed fasting for 5, 10, 15, and 20 days).

The review showed that prolonged fasting for 5-20 days produced large increases in circulating ketones, weight loss of 2%-10%, and decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

People who fasted 5 days typically lost 4%-6% of their weight; those who fasted 7-10 days lost 2%-10% of their weight; and those who fasted 15-20 days lost 7%-10% of their weight.

LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels decreased in some trials.

Fasting glucose levels, fasting insulin levels, insulin resistance, and A1c decreased in adults without diabetes but remained unchanged in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Some participants experienced metabolic acidosis, headaches, insomnia, or hunger.

About two-thirds of the weight lost was of lean mass, and one-third was of fat mass. The loss of lean mass loss suggests that prolonged fasting may increase the breakdown of muscle proteins, which is a concern, the researchers noted.

Few of the trials examined the effects of refeeding. In one study, normal-weight adults lost 6% of their weight after 5 days of water-only fasting but then gained it all back after 3 months of eating regularly.

In three trials, participants regained 1%-2% of their weight 2-4 months after fasting; however, those trials instructed participants to follow a calorie-restricted diet during the refeeding period.

Three to 4 months after the fast was completed, none of the metabolic benefits were maintained, even when weight loss was maintained.

The study did not receive external funding. Dr. Varady has received author fees from Hachette Book Group for “The Every Other Day Diet” and from Pan Macmillan Press for “The Fastest Diet.” The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Health benefits of prolonged “water fasting” (zero calories) or Buchinger fasting (200-300 calories/day) don’t last, according to authors of a review of eight studies.

Five days of fasting lowered weight by about 6%, but this weight was regained after 3 months of regular eating, the investigators found. The article was published in Nutrition Reviews.

“Water fasting led to improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels, but these were short-lived,” senior author Krista A. Varady, PhD, told this news organization.

“Levels returned to baseline ... quickly after participants started eating. Most benefits disappeared in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Varady, professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

“My overall conclusion,” she said, “is that I guess you could try it, but it just seems like a lot of work, and all those metabolic benefits disappear. I would encourage someone hoping to lose weight to try intermittent fasting instead of water fasting, because there’s a lot more data to show it can help with weight management.

“People should consult their doctor if they have diabetes or any other major obesity-related conditions before doing water fasting,” Dr. Varady cautioned.

“Healthy people with obesity can probably fast safely for 5 days on their own (if they don’t have any other conditions). However, no one should undertake one of these fasts for more than 5 days without medical supervision,” she stressed.

Eight studies of water and Buchinger fasting

Although several favorable effects of prolonged fasting have been observed, benefits must be weighed against risks, Dr. Varady and her coauthors wrote.

Most medically supervised fasting programs have reported only minor adverse events, which included hunger, headaches, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, and fatigue. However, more severe events have been documented, including edema, abnormal results on liver function tests, decreased bone density, and metabolic acidosis.

The researchers aimed to determine the effect of prolonged fasting on weight, blood pressure, lipid levels, and glycemic control, as well as safety and the effects of refeeding.

They examined two types of prolonged fasting: water fasting and Buchinger fasting, which involves consuming 250 mL of fruit or vegetable juice for lunch and 250 mL of soup for dinner every day of the 5- to 20-day fast.

Buchinger fasting is popular in Central Europe. Water fasting “institutes” exist in the United States, such as one in California, Dr. Varady noted.

The researchers excluded fasting during Ramadan or fasting practiced by Seventh Day Adventists.

They identified four studies of water fasting and four studies of Buchinger fasting (of which one study of 1,422 participants assessed fasting for 5, 10, 15, and 20 days).

The review showed that prolonged fasting for 5-20 days produced large increases in circulating ketones, weight loss of 2%-10%, and decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

People who fasted 5 days typically lost 4%-6% of their weight; those who fasted 7-10 days lost 2%-10% of their weight; and those who fasted 15-20 days lost 7%-10% of their weight.

LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels decreased in some trials.

Fasting glucose levels, fasting insulin levels, insulin resistance, and A1c decreased in adults without diabetes but remained unchanged in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Some participants experienced metabolic acidosis, headaches, insomnia, or hunger.

About two-thirds of the weight lost was of lean mass, and one-third was of fat mass. The loss of lean mass loss suggests that prolonged fasting may increase the breakdown of muscle proteins, which is a concern, the researchers noted.

Few of the trials examined the effects of refeeding. In one study, normal-weight adults lost 6% of their weight after 5 days of water-only fasting but then gained it all back after 3 months of eating regularly.

In three trials, participants regained 1%-2% of their weight 2-4 months after fasting; however, those trials instructed participants to follow a calorie-restricted diet during the refeeding period.

Three to 4 months after the fast was completed, none of the metabolic benefits were maintained, even when weight loss was maintained.

The study did not receive external funding. Dr. Varady has received author fees from Hachette Book Group for “The Every Other Day Diet” and from Pan Macmillan Press for “The Fastest Diet.” The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-dose colchicine for ASCVD: Your questions answered

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. O’Donoghue: We’re going to discuss a very important and emerging topic, which is the use of low-dose colchicine. I think there’s much interest in the use of this drug, which now has a Food and Drug Administration indication, which we’ll talk about further, and it’s also been written into both European and American guidelines that have been recently released.

who’s been at the forefront of research into anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Lifestyle lipid-lowering paramount

Dr. O’Donoghue: As we think about the concept behind the use of colchicine, we’ve obviously done a large amount of research into lipid-lowering drugs, but where does colchicine now fit in?

Dr. Ridker: Let’s make sure we get the basics down. Anti-inflammatory therapy is going to be added on top of quality other care. This is not a replacement for lipids; it’s not a change in diet, exercise, and smoking cessation. The new data are really telling us that a patient who’s aggressively treated to guideline-recommended levels can still do much better in terms of preventing heart attack, stroke, cardiovascular death, and revascularization by adding low-dose colchicine as the first proven anti-inflammatory therapy for atherosclerotic disease.

I have to say, Michelle, for me, it’s been a wonderful end of a journey in many ways. This story starts almost 30 years ago for quite a few of us, thinking about inflammation and atherosclerosis. The whole C-reactive protein (CRP) story is still an ongoing one. We recently showed, for example, that residual inflammatory risk in some 30,000 patients, all taking a statin, was a far better predictor of the likelihood of more cardiovascular events, in particular cardiovascular death, than was residual cholesterol risk.

Think about that. We’re all aggressively giving second lipid-lowering drugs in our very sick patients, but that means inflammation is really the untapped piece of this.

The two clinical trials we have in front of us, the COLCOT trial and the LoDoCo2 trial – both New England Journal of Medicine papers, both with roughly 5,000 patients – provide very clear evidence that following a relatively recent myocardial infarction (that’s COLCOT) in chronic stable atherosclerosis (that’s LoDoCo2), we’re getting 25%-30% relative risk reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) on top of aggressive statin therapy. That’s a big deal. It’s safe, it works, and it’s fully consistent with all the information we have about inflammation being part and parcel of atherosclerosis. It’s a pretty exciting time.

Inflammatory pathway

Dr. O’Donoghue: It beautifully proves the inflammatory hypothesis in many ways. You led CANTOS, and that was a much more specific target. Here, in terms of the effects of colchicine, what do we know about how it may work on the inflammatory cascade?

Dr. Ridker: Our CANTOS trial was proof of principle that you could directly target, with a very specific monoclonal antibody, a specific piece of this innate immune cascade and lower cardiovascular event rates.

Colchicine is a more broad-spectrum drug. It does have a number of antineutrophil effects – that’s important, by the way. Neutrophils are really becoming very important in atherosclerotic disease progression. It’s an indirect inhibitor of the so-called NLRP3 inflammasome, which is where both interleukin-1 (that’s the target for canakinumab) and IL-6 are up-regulated. As you know, it’s been used to treat gout and pericarditis in high doses in short, little bursts.

The change here is this use of low-dose colchicine, that’s 0.5 mg once a day for years to treat chronic, stable atherosclerosis. It is very much like using a statin. The idea here is to prevent the progression of the disease by slowing down and maybe stabilizing the plaque so we have fewer heart attacks and strokes down the road.

It’s entering the armamentarium – at least my armamentarium – as chronic, stable secondary prevention. That’s where the new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also put it. It’s really in as a treatment for chronic, stable atherosclerosis. I think that’s where it belongs.

When to start colchicine, and in whom?

Dr. O’Donoghue: To that point, as we think about the efficacy, I think it’s nice, as you outlined, that we have two complementary trials that are both showing a consistent reduction in MACEs, one in the post–acute coronary syndrome (ACS) state and one for more chronic patients.

At what point do you think would be the appropriate time to start therapy, and who would you be starting it for?

Dr. Ridker: Michelle, that’s a great question. There’s a very interesting analysis that just came out from the LoDoCo2 investigators. It’s kind of a landmark analysis. What they show is that 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, and 4 years since the initiating myocardial infarction, the drug is very effective.

In fact, you could think about starting this drug at your clinic in patients with chronic, stable atherosclerotic disease. That’s just like we would start a statin in people who had a heart attack some time ago, and that’s absolutely fine.

I’m using it for what I call my frequent fliers, those patients who just keep coming back. They’re already on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy. I have them on beta-blockers, aspirin, and all the usual things. I say, look, I can get a large risk reduction by starting them on this drug.

There are a few caveats, Michelle. Like all drugs, colchicine comes with some adverse effects. Most of them are pretty rare, but there are some patients I would not give this drug to, just to be very clear. Colchicine is cleared by the kidney and by the liver. Patients who have severe chronic kidney disease and severe liver disease – this is a no-go for those patients. We should talk about where patients in that realm might want to go.

Then there are some unusual drugs. Colchicine is metabolized by the CYP3A4 and the P-glycoprotein pathway. There are a few drugs, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, and cyclosporine, that if your primary care doctor or internist is going to start for a short term, you probably want to stop your colchicine for a week or two.

In people with familial Mediterranean fever, for whom colchicine is lifesaving and life-changing and who take it for 20, 30, or 40 years, there’s been no increase in risk for cancer. There have been very few adverse effects. I think it’s interesting that we, who practice in North America, basically never see familial Mediterranean fever. If we were practicing in Lebanon, Israel, or North Africa, this would be a very common therapy that we’d all be extremely familiar with.

Dr. O’Donoghue: To that point, it’s interesting to hear that colchicine was even used by the ancient Greeks and ancient Egyptians. It’s a drug that’s been around for a long time.

In terms of its safety, some people have been talking about the fact that an increase in noncardiovascular death was seen in LoDoCo2. What are your thoughts on that? Is that anything that we should be concerned about?

Colchicine safety and contraindications

Dr. Ridker: First, to set the record straight, a meta-analysis has been done of all-cause mortality in the various colchicine trials, and the hazard ratio is 1.04. I’ll remind you, and all of us know, that the hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in the PCSK9 trials, the bempedoic acid trials, and the ezetimibe trials are also essentially neutral. We’re in a state where we don’t let these trials roll long enough to see benefits necessarily on all-cause mortality. Some of us think we probably should, but that’s just the reality of trials.

One of most interesting things that was part of the FDA review, I suspect, was that there was no specific cause of any of this. It was not like there was a set of particular issues. I suspect that most people think this is probably the play of chance and with time, things will get better.

Again, I do want to emphasize this is not a drug for severe chronic kidney disease and severe liver disease, because those patients will get in trouble with this. The other thing that’s worth knowing is when you start a patient on low-dose colchicine – that’s 0.5 mg/d – there will be some patients who get some short-term gastrointestinal upset. That’s very common when you start colchicine at the much higher doses you might use to treat acute gout or pericarditis. In these trials, the vast majority of patients treated through that, and there were very few episodes long-term. I think it’s generally safe. That’s where we’re at.

Dr. O’Donoghue: Paul, you’ve been a leader, certainly, at looking at CRP as a marker of inflammation. Do you, in your practice, consider CRP levels when making a decision about who is appropriate for this therapy?

Dr. Ridker: That’s another terrific question. I do, because I’m trying to distinguish in my own mind patients who have residual inflammatory risk, in whom the high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) level remains high despite being on statins versus those with residual cholesterol risk, in whom I’m really predominantly worried about LDL cholesterol, that I haven’t brought it down far enough.

I do measure it, and if the CRP remains high and the LDL cholesterol is low, to me, that’s residual inflammatory risk and that’s the patient I would target this to. Conversely, if the LDL cholesterol was still, say, above some threshold of 75-100 and I’m worried about that, even if the CRP is low, I’ll probably add a second lipid-lowering drug.

The complexity of this, however, is that CRP was not measured in either LoDoCo2 or COLCOT. That’s mostly because they didn’t have much funding. These trials were done really on a shoestring. They were not sponsored by major pharma at all. We know that the median hsCRP in these trials was probably around 3.5-4 mg/L so I’m pretty comfortable doing that. Others have just advocated giving it to many patients. I must say I like to use biomarkers to think through the biology and who might have the best benefit-to-risk ratio. In my practice, I am doing it that way.

Inpatient vs. outpatient initiation

Dr. O’Donoghue: This is perhaps my last question for you before we wrap up. I know you talked about use of low-dose colchicine for patients with more chronic, stable coronary disease. Now obviously, COLCOT studied patients who were early post ACS, and there we certainly think about the anti-inflammatory effects as potentially having more benefit. What are your thoughts about early initiation of colchicine in that setting, the acute hospitalized setting? Do you think it’s more appropriate for an outpatient start?

Dr. Ridker: Today, I think this is all about chronic, stable atherosclerosis. Yes, COLCOT enrolled their patients within 30 days of a recent myocardial infarction, but as we all know, that’s a pretty stable phase. The vast majority were enrolled after 15 days. There were a small number enrolled within 3 days or something like that, but the benefit is about the same in all these patients.

Conversely, there’s been a small number of trials looking at colchicine in acute coronary ischemia and they’ve not been terribly promising. That makes some sense, though, right? We want to get an artery open. In acute ischemia, that’s about revascularization. It’s about oxygenation. It’s about reperfusion injury. My guess is that 3, 4, 5, or 6 days later, when it becomes a stable situation, is when the drug is probably effective.

Again, there will be some ongoing true intervention trials with large sample sizes for acute coronary ischemia. We don’t have those yet. Right now, I think it’s a therapy for chronic, stable angina. That’s many of our patients.

I would say that if you compare the relative benefit in these trials of adding ezetimibe to a statin, that’s a 5% or 6% benefit. For PCSK9 inhibitors – we all use them – it’s about a 15% benefit. These are 25%-30% risk reductions. If we’re going to think about what’s the next drug to give on top of the statin, serious consideration should be given to low-dose colchicine.

Let me also emphasize that this is not an either/or situation. This is about the fact that we now understand atherosclerosis to be a disorder both of lipid accumulation and a proinflammatory systemic response. We can give these drugs together. I suspect that the best patient care is going to be very aggressive lipid-lowering combined with pretty aggressive inflammation inhibition. I suspect that, down the road, that’s where all of us are going to be.

Dr. O’Donoghue: Thank you so much, Paul, for walking us through that today. I think it was a very nice, succinct review of the evidence, and then also just getting our minds more accustomed to the concept that we can now start to target more orthogonal axes that really get at the pathobiology of what’s going on in the atherosclerotic plaque. I think it’s an important topic.

Dr. O’Donoghue is an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and an associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston. Dr. Ridker is director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Both Dr. O’Donoghue and Dr. Ridker reported numerous conflicts of interest.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. O’Donoghue: We’re going to discuss a very important and emerging topic, which is the use of low-dose colchicine. I think there’s much interest in the use of this drug, which now has a Food and Drug Administration indication, which we’ll talk about further, and it’s also been written into both European and American guidelines that have been recently released.

who’s been at the forefront of research into anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Lifestyle lipid-lowering paramount

Dr. O’Donoghue: As we think about the concept behind the use of colchicine, we’ve obviously done a large amount of research into lipid-lowering drugs, but where does colchicine now fit in?

Dr. Ridker: Let’s make sure we get the basics down. Anti-inflammatory therapy is going to be added on top of quality other care. This is not a replacement for lipids; it’s not a change in diet, exercise, and smoking cessation. The new data are really telling us that a patient who’s aggressively treated to guideline-recommended levels can still do much better in terms of preventing heart attack, stroke, cardiovascular death, and revascularization by adding low-dose colchicine as the first proven anti-inflammatory therapy for atherosclerotic disease.

I have to say, Michelle, for me, it’s been a wonderful end of a journey in many ways. This story starts almost 30 years ago for quite a few of us, thinking about inflammation and atherosclerosis. The whole C-reactive protein (CRP) story is still an ongoing one. We recently showed, for example, that residual inflammatory risk in some 30,000 patients, all taking a statin, was a far better predictor of the likelihood of more cardiovascular events, in particular cardiovascular death, than was residual cholesterol risk.

Think about that. We’re all aggressively giving second lipid-lowering drugs in our very sick patients, but that means inflammation is really the untapped piece of this.

The two clinical trials we have in front of us, the COLCOT trial and the LoDoCo2 trial – both New England Journal of Medicine papers, both with roughly 5,000 patients – provide very clear evidence that following a relatively recent myocardial infarction (that’s COLCOT) in chronic stable atherosclerosis (that’s LoDoCo2), we’re getting 25%-30% relative risk reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) on top of aggressive statin therapy. That’s a big deal. It’s safe, it works, and it’s fully consistent with all the information we have about inflammation being part and parcel of atherosclerosis. It’s a pretty exciting time.

Inflammatory pathway

Dr. O’Donoghue: It beautifully proves the inflammatory hypothesis in many ways. You led CANTOS, and that was a much more specific target. Here, in terms of the effects of colchicine, what do we know about how it may work on the inflammatory cascade?

Dr. Ridker: Our CANTOS trial was proof of principle that you could directly target, with a very specific monoclonal antibody, a specific piece of this innate immune cascade and lower cardiovascular event rates.

Colchicine is a more broad-spectrum drug. It does have a number of antineutrophil effects – that’s important, by the way. Neutrophils are really becoming very important in atherosclerotic disease progression. It’s an indirect inhibitor of the so-called NLRP3 inflammasome, which is where both interleukin-1 (that’s the target for canakinumab) and IL-6 are up-regulated. As you know, it’s been used to treat gout and pericarditis in high doses in short, little bursts.

The change here is this use of low-dose colchicine, that’s 0.5 mg once a day for years to treat chronic, stable atherosclerosis. It is very much like using a statin. The idea here is to prevent the progression of the disease by slowing down and maybe stabilizing the plaque so we have fewer heart attacks and strokes down the road.

It’s entering the armamentarium – at least my armamentarium – as chronic, stable secondary prevention. That’s where the new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also put it. It’s really in as a treatment for chronic, stable atherosclerosis. I think that’s where it belongs.

When to start colchicine, and in whom?

Dr. O’Donoghue: To that point, as we think about the efficacy, I think it’s nice, as you outlined, that we have two complementary trials that are both showing a consistent reduction in MACEs, one in the post–acute coronary syndrome (ACS) state and one for more chronic patients.

At what point do you think would be the appropriate time to start therapy, and who would you be starting it for?

Dr. Ridker: Michelle, that’s a great question. There’s a very interesting analysis that just came out from the LoDoCo2 investigators. It’s kind of a landmark analysis. What they show is that 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, and 4 years since the initiating myocardial infarction, the drug is very effective.

In fact, you could think about starting this drug at your clinic in patients with chronic, stable atherosclerotic disease. That’s just like we would start a statin in people who had a heart attack some time ago, and that’s absolutely fine.

I’m using it for what I call my frequent fliers, those patients who just keep coming back. They’re already on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy. I have them on beta-blockers, aspirin, and all the usual things. I say, look, I can get a large risk reduction by starting them on this drug.

There are a few caveats, Michelle. Like all drugs, colchicine comes with some adverse effects. Most of them are pretty rare, but there are some patients I would not give this drug to, just to be very clear. Colchicine is cleared by the kidney and by the liver. Patients who have severe chronic kidney disease and severe liver disease – this is a no-go for those patients. We should talk about where patients in that realm might want to go.

Then there are some unusual drugs. Colchicine is metabolized by the CYP3A4 and the P-glycoprotein pathway. There are a few drugs, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, and cyclosporine, that if your primary care doctor or internist is going to start for a short term, you probably want to stop your colchicine for a week or two.

In people with familial Mediterranean fever, for whom colchicine is lifesaving and life-changing and who take it for 20, 30, or 40 years, there’s been no increase in risk for cancer. There have been very few adverse effects. I think it’s interesting that we, who practice in North America, basically never see familial Mediterranean fever. If we were practicing in Lebanon, Israel, or North Africa, this would be a very common therapy that we’d all be extremely familiar with.

Dr. O’Donoghue: To that point, it’s interesting to hear that colchicine was even used by the ancient Greeks and ancient Egyptians. It’s a drug that’s been around for a long time.

In terms of its safety, some people have been talking about the fact that an increase in noncardiovascular death was seen in LoDoCo2. What are your thoughts on that? Is that anything that we should be concerned about?

Colchicine safety and contraindications

Dr. Ridker: First, to set the record straight, a meta-analysis has been done of all-cause mortality in the various colchicine trials, and the hazard ratio is 1.04. I’ll remind you, and all of us know, that the hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in the PCSK9 trials, the bempedoic acid trials, and the ezetimibe trials are also essentially neutral. We’re in a state where we don’t let these trials roll long enough to see benefits necessarily on all-cause mortality. Some of us think we probably should, but that’s just the reality of trials.

One of most interesting things that was part of the FDA review, I suspect, was that there was no specific cause of any of this. It was not like there was a set of particular issues. I suspect that most people think this is probably the play of chance and with time, things will get better.

Again, I do want to emphasize this is not a drug for severe chronic kidney disease and severe liver disease, because those patients will get in trouble with this. The other thing that’s worth knowing is when you start a patient on low-dose colchicine – that’s 0.5 mg/d – there will be some patients who get some short-term gastrointestinal upset. That’s very common when you start colchicine at the much higher doses you might use to treat acute gout or pericarditis. In these trials, the vast majority of patients treated through that, and there were very few episodes long-term. I think it’s generally safe. That’s where we’re at.

Dr. O’Donoghue: Paul, you’ve been a leader, certainly, at looking at CRP as a marker of inflammation. Do you, in your practice, consider CRP levels when making a decision about who is appropriate for this therapy?

Dr. Ridker: That’s another terrific question. I do, because I’m trying to distinguish in my own mind patients who have residual inflammatory risk, in whom the high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) level remains high despite being on statins versus those with residual cholesterol risk, in whom I’m really predominantly worried about LDL cholesterol, that I haven’t brought it down far enough.

I do measure it, and if the CRP remains high and the LDL cholesterol is low, to me, that’s residual inflammatory risk and that’s the patient I would target this to. Conversely, if the LDL cholesterol was still, say, above some threshold of 75-100 and I’m worried about that, even if the CRP is low, I’ll probably add a second lipid-lowering drug.

The complexity of this, however, is that CRP was not measured in either LoDoCo2 or COLCOT. That’s mostly because they didn’t have much funding. These trials were done really on a shoestring. They were not sponsored by major pharma at all. We know that the median hsCRP in these trials was probably around 3.5-4 mg/L so I’m pretty comfortable doing that. Others have just advocated giving it to many patients. I must say I like to use biomarkers to think through the biology and who might have the best benefit-to-risk ratio. In my practice, I am doing it that way.

Inpatient vs. outpatient initiation

Dr. O’Donoghue: This is perhaps my last question for you before we wrap up. I know you talked about use of low-dose colchicine for patients with more chronic, stable coronary disease. Now obviously, COLCOT studied patients who were early post ACS, and there we certainly think about the anti-inflammatory effects as potentially having more benefit. What are your thoughts about early initiation of colchicine in that setting, the acute hospitalized setting? Do you think it’s more appropriate for an outpatient start?

Dr. Ridker: Today, I think this is all about chronic, stable atherosclerosis. Yes, COLCOT enrolled their patients within 30 days of a recent myocardial infarction, but as we all know, that’s a pretty stable phase. The vast majority were enrolled after 15 days. There were a small number enrolled within 3 days or something like that, but the benefit is about the same in all these patients.

Conversely, there’s been a small number of trials looking at colchicine in acute coronary ischemia and they’ve not been terribly promising. That makes some sense, though, right? We want to get an artery open. In acute ischemia, that’s about revascularization. It’s about oxygenation. It’s about reperfusion injury. My guess is that 3, 4, 5, or 6 days later, when it becomes a stable situation, is when the drug is probably effective.

Again, there will be some ongoing true intervention trials with large sample sizes for acute coronary ischemia. We don’t have those yet. Right now, I think it’s a therapy for chronic, stable angina. That’s many of our patients.

I would say that if you compare the relative benefit in these trials of adding ezetimibe to a statin, that’s a 5% or 6% benefit. For PCSK9 inhibitors – we all use them – it’s about a 15% benefit. These are 25%-30% risk reductions. If we’re going to think about what’s the next drug to give on top of the statin, serious consideration should be given to low-dose colchicine.

Let me also emphasize that this is not an either/or situation. This is about the fact that we now understand atherosclerosis to be a disorder both of lipid accumulation and a proinflammatory systemic response. We can give these drugs together. I suspect that the best patient care is going to be very aggressive lipid-lowering combined with pretty aggressive inflammation inhibition. I suspect that, down the road, that’s where all of us are going to be.

Dr. O’Donoghue: Thank you so much, Paul, for walking us through that today. I think it was a very nice, succinct review of the evidence, and then also just getting our minds more accustomed to the concept that we can now start to target more orthogonal axes that really get at the pathobiology of what’s going on in the atherosclerotic plaque. I think it’s an important topic.

Dr. O’Donoghue is an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and an associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston. Dr. Ridker is director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Both Dr. O’Donoghue and Dr. Ridker reported numerous conflicts of interest.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. O’Donoghue: We’re going to discuss a very important and emerging topic, which is the use of low-dose colchicine. I think there’s much interest in the use of this drug, which now has a Food and Drug Administration indication, which we’ll talk about further, and it’s also been written into both European and American guidelines that have been recently released.

who’s been at the forefront of research into anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Lifestyle lipid-lowering paramount

Dr. O’Donoghue: As we think about the concept behind the use of colchicine, we’ve obviously done a large amount of research into lipid-lowering drugs, but where does colchicine now fit in?

Dr. Ridker: Let’s make sure we get the basics down. Anti-inflammatory therapy is going to be added on top of quality other care. This is not a replacement for lipids; it’s not a change in diet, exercise, and smoking cessation. The new data are really telling us that a patient who’s aggressively treated to guideline-recommended levels can still do much better in terms of preventing heart attack, stroke, cardiovascular death, and revascularization by adding low-dose colchicine as the first proven anti-inflammatory therapy for atherosclerotic disease.

I have to say, Michelle, for me, it’s been a wonderful end of a journey in many ways. This story starts almost 30 years ago for quite a few of us, thinking about inflammation and atherosclerosis. The whole C-reactive protein (CRP) story is still an ongoing one. We recently showed, for example, that residual inflammatory risk in some 30,000 patients, all taking a statin, was a far better predictor of the likelihood of more cardiovascular events, in particular cardiovascular death, than was residual cholesterol risk.

Think about that. We’re all aggressively giving second lipid-lowering drugs in our very sick patients, but that means inflammation is really the untapped piece of this.

The two clinical trials we have in front of us, the COLCOT trial and the LoDoCo2 trial – both New England Journal of Medicine papers, both with roughly 5,000 patients – provide very clear evidence that following a relatively recent myocardial infarction (that’s COLCOT) in chronic stable atherosclerosis (that’s LoDoCo2), we’re getting 25%-30% relative risk reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) on top of aggressive statin therapy. That’s a big deal. It’s safe, it works, and it’s fully consistent with all the information we have about inflammation being part and parcel of atherosclerosis. It’s a pretty exciting time.

Inflammatory pathway

Dr. O’Donoghue: It beautifully proves the inflammatory hypothesis in many ways. You led CANTOS, and that was a much more specific target. Here, in terms of the effects of colchicine, what do we know about how it may work on the inflammatory cascade?

Dr. Ridker: Our CANTOS trial was proof of principle that you could directly target, with a very specific monoclonal antibody, a specific piece of this innate immune cascade and lower cardiovascular event rates.

Colchicine is a more broad-spectrum drug. It does have a number of antineutrophil effects – that’s important, by the way. Neutrophils are really becoming very important in atherosclerotic disease progression. It’s an indirect inhibitor of the so-called NLRP3 inflammasome, which is where both interleukin-1 (that’s the target for canakinumab) and IL-6 are up-regulated. As you know, it’s been used to treat gout and pericarditis in high doses in short, little bursts.

The change here is this use of low-dose colchicine, that’s 0.5 mg once a day for years to treat chronic, stable atherosclerosis. It is very much like using a statin. The idea here is to prevent the progression of the disease by slowing down and maybe stabilizing the plaque so we have fewer heart attacks and strokes down the road.

It’s entering the armamentarium – at least my armamentarium – as chronic, stable secondary prevention. That’s where the new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also put it. It’s really in as a treatment for chronic, stable atherosclerosis. I think that’s where it belongs.

When to start colchicine, and in whom?

Dr. O’Donoghue: To that point, as we think about the efficacy, I think it’s nice, as you outlined, that we have two complementary trials that are both showing a consistent reduction in MACEs, one in the post–acute coronary syndrome (ACS) state and one for more chronic patients.

At what point do you think would be the appropriate time to start therapy, and who would you be starting it for?

Dr. Ridker: Michelle, that’s a great question. There’s a very interesting analysis that just came out from the LoDoCo2 investigators. It’s kind of a landmark analysis. What they show is that 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, and 4 years since the initiating myocardial infarction, the drug is very effective.

In fact, you could think about starting this drug at your clinic in patients with chronic, stable atherosclerotic disease. That’s just like we would start a statin in people who had a heart attack some time ago, and that’s absolutely fine.

I’m using it for what I call my frequent fliers, those patients who just keep coming back. They’re already on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy. I have them on beta-blockers, aspirin, and all the usual things. I say, look, I can get a large risk reduction by starting them on this drug.

There are a few caveats, Michelle. Like all drugs, colchicine comes with some adverse effects. Most of them are pretty rare, but there are some patients I would not give this drug to, just to be very clear. Colchicine is cleared by the kidney and by the liver. Patients who have severe chronic kidney disease and severe liver disease – this is a no-go for those patients. We should talk about where patients in that realm might want to go.

Then there are some unusual drugs. Colchicine is metabolized by the CYP3A4 and the P-glycoprotein pathway. There are a few drugs, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, and cyclosporine, that if your primary care doctor or internist is going to start for a short term, you probably want to stop your colchicine for a week or two.

In people with familial Mediterranean fever, for whom colchicine is lifesaving and life-changing and who take it for 20, 30, or 40 years, there’s been no increase in risk for cancer. There have been very few adverse effects. I think it’s interesting that we, who practice in North America, basically never see familial Mediterranean fever. If we were practicing in Lebanon, Israel, or North Africa, this would be a very common therapy that we’d all be extremely familiar with.

Dr. O’Donoghue: To that point, it’s interesting to hear that colchicine was even used by the ancient Greeks and ancient Egyptians. It’s a drug that’s been around for a long time.

In terms of its safety, some people have been talking about the fact that an increase in noncardiovascular death was seen in LoDoCo2. What are your thoughts on that? Is that anything that we should be concerned about?

Colchicine safety and contraindications

Dr. Ridker: First, to set the record straight, a meta-analysis has been done of all-cause mortality in the various colchicine trials, and the hazard ratio is 1.04. I’ll remind you, and all of us know, that the hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in the PCSK9 trials, the bempedoic acid trials, and the ezetimibe trials are also essentially neutral. We’re in a state where we don’t let these trials roll long enough to see benefits necessarily on all-cause mortality. Some of us think we probably should, but that’s just the reality of trials.

One of most interesting things that was part of the FDA review, I suspect, was that there was no specific cause of any of this. It was not like there was a set of particular issues. I suspect that most people think this is probably the play of chance and with time, things will get better.

Again, I do want to emphasize this is not a drug for severe chronic kidney disease and severe liver disease, because those patients will get in trouble with this. The other thing that’s worth knowing is when you start a patient on low-dose colchicine – that’s 0.5 mg/d – there will be some patients who get some short-term gastrointestinal upset. That’s very common when you start colchicine at the much higher doses you might use to treat acute gout or pericarditis. In these trials, the vast majority of patients treated through that, and there were very few episodes long-term. I think it’s generally safe. That’s where we’re at.

Dr. O’Donoghue: Paul, you’ve been a leader, certainly, at looking at CRP as a marker of inflammation. Do you, in your practice, consider CRP levels when making a decision about who is appropriate for this therapy?

Dr. Ridker: That’s another terrific question. I do, because I’m trying to distinguish in my own mind patients who have residual inflammatory risk, in whom the high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) level remains high despite being on statins versus those with residual cholesterol risk, in whom I’m really predominantly worried about LDL cholesterol, that I haven’t brought it down far enough.

I do measure it, and if the CRP remains high and the LDL cholesterol is low, to me, that’s residual inflammatory risk and that’s the patient I would target this to. Conversely, if the LDL cholesterol was still, say, above some threshold of 75-100 and I’m worried about that, even if the CRP is low, I’ll probably add a second lipid-lowering drug.

The complexity of this, however, is that CRP was not measured in either LoDoCo2 or COLCOT. That’s mostly because they didn’t have much funding. These trials were done really on a shoestring. They were not sponsored by major pharma at all. We know that the median hsCRP in these trials was probably around 3.5-4 mg/L so I’m pretty comfortable doing that. Others have just advocated giving it to many patients. I must say I like to use biomarkers to think through the biology and who might have the best benefit-to-risk ratio. In my practice, I am doing it that way.

Inpatient vs. outpatient initiation

Dr. O’Donoghue: This is perhaps my last question for you before we wrap up. I know you talked about use of low-dose colchicine for patients with more chronic, stable coronary disease. Now obviously, COLCOT studied patients who were early post ACS, and there we certainly think about the anti-inflammatory effects as potentially having more benefit. What are your thoughts about early initiation of colchicine in that setting, the acute hospitalized setting? Do you think it’s more appropriate for an outpatient start?

Dr. Ridker: Today, I think this is all about chronic, stable atherosclerosis. Yes, COLCOT enrolled their patients within 30 days of a recent myocardial infarction, but as we all know, that’s a pretty stable phase. The vast majority were enrolled after 15 days. There were a small number enrolled within 3 days or something like that, but the benefit is about the same in all these patients.

Conversely, there’s been a small number of trials looking at colchicine in acute coronary ischemia and they’ve not been terribly promising. That makes some sense, though, right? We want to get an artery open. In acute ischemia, that’s about revascularization. It’s about oxygenation. It’s about reperfusion injury. My guess is that 3, 4, 5, or 6 days later, when it becomes a stable situation, is when the drug is probably effective.

Again, there will be some ongoing true intervention trials with large sample sizes for acute coronary ischemia. We don’t have those yet. Right now, I think it’s a therapy for chronic, stable angina. That’s many of our patients.

I would say that if you compare the relative benefit in these trials of adding ezetimibe to a statin, that’s a 5% or 6% benefit. For PCSK9 inhibitors – we all use them – it’s about a 15% benefit. These are 25%-30% risk reductions. If we’re going to think about what’s the next drug to give on top of the statin, serious consideration should be given to low-dose colchicine.

Let me also emphasize that this is not an either/or situation. This is about the fact that we now understand atherosclerosis to be a disorder both of lipid accumulation and a proinflammatory systemic response. We can give these drugs together. I suspect that the best patient care is going to be very aggressive lipid-lowering combined with pretty aggressive inflammation inhibition. I suspect that, down the road, that’s where all of us are going to be.

Dr. O’Donoghue: Thank you so much, Paul, for walking us through that today. I think it was a very nice, succinct review of the evidence, and then also just getting our minds more accustomed to the concept that we can now start to target more orthogonal axes that really get at the pathobiology of what’s going on in the atherosclerotic plaque. I think it’s an important topic.

Dr. O’Donoghue is an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and an associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston. Dr. Ridker is director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Both Dr. O’Donoghue and Dr. Ridker reported numerous conflicts of interest.

Prioritize nutrients, limit ultraprocessed food in diabetes

In a large cohort of older adults with type 2 diabetes in Italy, those with the highest intake of ultraprocessed food and beverages (UPF) were more likely to die of all causes or cardiovascular disease (CVD) within a decade than those with the lowest intake – independent of adherence to a healthy Mediterranean diet.

Adults in the top quartile of UPF intake had a 64% increased risk of all-cause death and a 2.5-fold increased risk of CVD death during follow-up, compared with those in the lowest quartile, after adjusting for variables including Mediterranean diet score.

These findings from the Moli-sani study by Marialaura Bonaccio, PhD, from the Institute for Research, Hospitalization and Healthcare (IRCCS) Neuromed, in Pozzilli, Italy, and colleagues, were published online in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

“Dietary recommendations for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes almost exclusively prioritize consumption of nutritionally balanced foods that are the source of fiber [and] healthy fats and [are] poor in free sugars, and promote dietary patterns – such as the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet – that place a large emphasis on food groups (for example, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fruits, and vegetables) regardless of food processing,” the researchers note.

The research suggests that “besides prioritizing the adoption of a diet based on nutritional requirements, dietary guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes should also recommend limiting UPF,” they conclude.

“In addition to the adoption of a diet based on well-known nutritional requirements, dietary recommendations should also suggest limiting the consumption of ultraprocessed foods as much as possible,” Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, president, IRCCS Neuromed, echoed, in a press release from the institute.

“In this context, and not only for people with diabetes, the front-of-pack nutrition labels should also include information on the degree of food processing,” he observed.

Caroline M. Apovian, MD, who was not involved with the study, agrees that it is wise to limit consumption of UPF.

However, we need more research to better understand which components of UPF are harmful and the biologic mechanisms, Dr. Apovian, who is codirector, Center for Weight Management and Wellness, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told this news organization in an interview.

She noted that in a randomized crossover trial in 20 patients who were instructed to eat as much or as little as they wanted, people ate more and gained weight during 2 weeks of a diet high in UPF, compared with 2 weeks of an unprocessed diet matched for presented calories, carbohydrate, sugar, fat, sodium, and fiber.

Ultraprocessed foods classed according to Nova system

UPF is “made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives, using a series of processes and containing minimal whole foods,” and they “are usually nutrient-poor, high in calories, added sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fats,” the Italian researchers write.

High intake of UPF, they add, may exacerbate health risks in people with type 2 diabetes, who are already at higher risk of premature mortality, mainly due to diabetes-related complications.

The researchers analyzed data from a subset of patients in the Moli-sani study of environmental and genetic factors underlying disease, which enrolled 24,325 individuals aged 35 and older who lived in Molise, in central-southern Italy, in 2005-2010.

The current analysis included 1,065 participants in Moli-sani who had type 2 diabetes at baseline and completed a food frequency questionnaire by which participants reported their consumption of 188 foods and beverages in the previous 12 months.

Participants were a mean age of 65 years, and 60% were men.

Most UPF intake was from processed meat (22.4%), crispbread/rusks (16.6%), nonhomemade pizza (11.2%), and cakes, pies, pastries, and puddings (8.8%).

Researchers categorized foods and beverages into four groups with increasing degrees of processing, based on the Nova Food Classification System:

- Group 1: Fresh or minimally processed foods and beverages (for example, fruit, meat, milk).

- Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients (for example, oils, butter).

- Group 3: Processed foods and beverages (for example, canned fish, bread).

- Group 4: UPF (22 foods and beverages including carbonated drinks, processed meats, sweet or savory packaged snacks, margarine, and foods and beverages with artificial sweeteners).

Participants were divided into four quartiles based on UPF consumption.

The mean percentage of UPF consumption out of total food and beverage intake was 2.8%, 5.2%, 7.7%, and 14.4% for quartiles 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. By sex, these rates for quartile 1 were < 4.7% for women and < 3.7% for men, and for quartile 4 were ≥ 10.5% for women and ≥ 9% for men.

Participants with the highest UPF intake were younger (mean age, 63 vs. 67 years) but otherwise had similar characteristics as other participants.

During a median follow-up of 11.6 years, 308 participants died from all causes, including 129 who died from CVD.

Compared with participants with the lowest intake of UPF (quartile 1), those with the highest intake (quartile 4) had a higher risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.70) and CVD mortality (HR, 2.64) during follow-up, after multivariable adjustment. The analysis adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, residence, education, housing, smoking, body mass index, leisure-time physical activity, history of cancer or cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, aspirin use, years since type 2 diabetes diagnosis, and special diet for blood glucose control.

After further adjusting for Mediterranean diet score, the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality during follow-up for patients with the highest versus lowest intake of UPF remained similar (HR, 1.64 and 2.55, respectively).

There was a linear dose–response relationship between UPF and all-cause and CVD mortality.

Increasing intake of fruit drinks, carbonated drinks, and salty biscuits was associated with higher all-cause and CVD mortality rates, and consumption of stock cubes and margarine was further related to higher CVD death.

The researchers acknowledge that the study was observational, and therefore cannot determine cause and effect, and was not designed to specifically collect dietary data according to the Nova classification. The findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

The analysis was partly funded by grants from the AIRC and Italian Ministry of Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large cohort of older adults with type 2 diabetes in Italy, those with the highest intake of ultraprocessed food and beverages (UPF) were more likely to die of all causes or cardiovascular disease (CVD) within a decade than those with the lowest intake – independent of adherence to a healthy Mediterranean diet.

Adults in the top quartile of UPF intake had a 64% increased risk of all-cause death and a 2.5-fold increased risk of CVD death during follow-up, compared with those in the lowest quartile, after adjusting for variables including Mediterranean diet score.

These findings from the Moli-sani study by Marialaura Bonaccio, PhD, from the Institute for Research, Hospitalization and Healthcare (IRCCS) Neuromed, in Pozzilli, Italy, and colleagues, were published online in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

“Dietary recommendations for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes almost exclusively prioritize consumption of nutritionally balanced foods that are the source of fiber [and] healthy fats and [are] poor in free sugars, and promote dietary patterns – such as the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet – that place a large emphasis on food groups (for example, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fruits, and vegetables) regardless of food processing,” the researchers note.

The research suggests that “besides prioritizing the adoption of a diet based on nutritional requirements, dietary guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes should also recommend limiting UPF,” they conclude.

“In addition to the adoption of a diet based on well-known nutritional requirements, dietary recommendations should also suggest limiting the consumption of ultraprocessed foods as much as possible,” Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, president, IRCCS Neuromed, echoed, in a press release from the institute.

“In this context, and not only for people with diabetes, the front-of-pack nutrition labels should also include information on the degree of food processing,” he observed.

Caroline M. Apovian, MD, who was not involved with the study, agrees that it is wise to limit consumption of UPF.

However, we need more research to better understand which components of UPF are harmful and the biologic mechanisms, Dr. Apovian, who is codirector, Center for Weight Management and Wellness, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told this news organization in an interview.

She noted that in a randomized crossover trial in 20 patients who were instructed to eat as much or as little as they wanted, people ate more and gained weight during 2 weeks of a diet high in UPF, compared with 2 weeks of an unprocessed diet matched for presented calories, carbohydrate, sugar, fat, sodium, and fiber.

Ultraprocessed foods classed according to Nova system

UPF is “made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives, using a series of processes and containing minimal whole foods,” and they “are usually nutrient-poor, high in calories, added sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fats,” the Italian researchers write.

High intake of UPF, they add, may exacerbate health risks in people with type 2 diabetes, who are already at higher risk of premature mortality, mainly due to diabetes-related complications.

The researchers analyzed data from a subset of patients in the Moli-sani study of environmental and genetic factors underlying disease, which enrolled 24,325 individuals aged 35 and older who lived in Molise, in central-southern Italy, in 2005-2010.

The current analysis included 1,065 participants in Moli-sani who had type 2 diabetes at baseline and completed a food frequency questionnaire by which participants reported their consumption of 188 foods and beverages in the previous 12 months.