User login

Intelligent Liver Function Testing Helps Detect, Diagnose Chronic Liver Disease

TOPLINE:

, new data show.

METHODOLOGY:

- At the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2024, researchers presented 5-year, real-world data of the iLFT platform from its use in NHS Tayside in Dundee, Scotland, which serves a population of 400,000. The platform has been available since 2018.

- The iLFT platform uses an automated algorithm that analyzes standard liver function test results.

- Abnormal results prompt the system to initiate further fibrosis scoring and relevant etiologic testing to determine the cause of liver dysfunction.

- The results of these tests combined with practitioner-entered clinical information produce a probable diagnosis and recommend a patient-management strategy.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 26,459 iLFT tests performed between 2018 and 2023, 68.3% (18,079) required further testing beyond the initial liver function test, whereas 31.7% (8380) did not.

- Further testing generated 20,895 outcomes, of which, isolated abnormal alanine transaminase (ALT) without fibrosis was most frequent (23.7%). Abnormal ALT was found to be most likely due to metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

- Overall, half of cascaded samples had a positive etiologic diagnosis. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and MASLD were the most common etiologic outcomes identified.

- In addition, 20% of cascaded tests identified potentially significant liver fibrosis.

- A total of 69.9% of outcomes recommended that patients could be safely managed in primary care. The inclusion of automatic Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) testing in 2020 further reduced the requirement for referral to secondary care by 34%.

IN PRACTICE:

“Without this algorithm, the 18,000 patients who had algorithm-directed further testing would have had to go back to the [primary care practitioner] to obtain the additional tests, and the [primary care practitioner] would need to interpret them too,” said Damien Leith, MD, trainee hepatologist at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, Scotland, who presented the findings. “iLFTs ensure the right patients get automated, appropriate follow-up testing and subsequent recommendation of referral to secondary care if necessary, and importantly iLFT helps the primary care practitioner identify the cause of chronic liver disease.”

SOURCE:

This study was presented on June 6, 2024 at the EASL Congress 2024 (abstract OS-007-YI).

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include the need for further refinement of the algorithm to increase the proportion of positive etiologic iLFT outcomes. More analysis is needed to optimize the cost-effectiveness of iLFT.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Leith reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new data show.

METHODOLOGY:

- At the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2024, researchers presented 5-year, real-world data of the iLFT platform from its use in NHS Tayside in Dundee, Scotland, which serves a population of 400,000. The platform has been available since 2018.

- The iLFT platform uses an automated algorithm that analyzes standard liver function test results.

- Abnormal results prompt the system to initiate further fibrosis scoring and relevant etiologic testing to determine the cause of liver dysfunction.

- The results of these tests combined with practitioner-entered clinical information produce a probable diagnosis and recommend a patient-management strategy.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 26,459 iLFT tests performed between 2018 and 2023, 68.3% (18,079) required further testing beyond the initial liver function test, whereas 31.7% (8380) did not.

- Further testing generated 20,895 outcomes, of which, isolated abnormal alanine transaminase (ALT) without fibrosis was most frequent (23.7%). Abnormal ALT was found to be most likely due to metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

- Overall, half of cascaded samples had a positive etiologic diagnosis. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and MASLD were the most common etiologic outcomes identified.

- In addition, 20% of cascaded tests identified potentially significant liver fibrosis.

- A total of 69.9% of outcomes recommended that patients could be safely managed in primary care. The inclusion of automatic Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) testing in 2020 further reduced the requirement for referral to secondary care by 34%.

IN PRACTICE:

“Without this algorithm, the 18,000 patients who had algorithm-directed further testing would have had to go back to the [primary care practitioner] to obtain the additional tests, and the [primary care practitioner] would need to interpret them too,” said Damien Leith, MD, trainee hepatologist at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, Scotland, who presented the findings. “iLFTs ensure the right patients get automated, appropriate follow-up testing and subsequent recommendation of referral to secondary care if necessary, and importantly iLFT helps the primary care practitioner identify the cause of chronic liver disease.”

SOURCE:

This study was presented on June 6, 2024 at the EASL Congress 2024 (abstract OS-007-YI).

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include the need for further refinement of the algorithm to increase the proportion of positive etiologic iLFT outcomes. More analysis is needed to optimize the cost-effectiveness of iLFT.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Leith reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new data show.

METHODOLOGY:

- At the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2024, researchers presented 5-year, real-world data of the iLFT platform from its use in NHS Tayside in Dundee, Scotland, which serves a population of 400,000. The platform has been available since 2018.

- The iLFT platform uses an automated algorithm that analyzes standard liver function test results.

- Abnormal results prompt the system to initiate further fibrosis scoring and relevant etiologic testing to determine the cause of liver dysfunction.

- The results of these tests combined with practitioner-entered clinical information produce a probable diagnosis and recommend a patient-management strategy.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 26,459 iLFT tests performed between 2018 and 2023, 68.3% (18,079) required further testing beyond the initial liver function test, whereas 31.7% (8380) did not.

- Further testing generated 20,895 outcomes, of which, isolated abnormal alanine transaminase (ALT) without fibrosis was most frequent (23.7%). Abnormal ALT was found to be most likely due to metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

- Overall, half of cascaded samples had a positive etiologic diagnosis. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and MASLD were the most common etiologic outcomes identified.

- In addition, 20% of cascaded tests identified potentially significant liver fibrosis.

- A total of 69.9% of outcomes recommended that patients could be safely managed in primary care. The inclusion of automatic Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) testing in 2020 further reduced the requirement for referral to secondary care by 34%.

IN PRACTICE:

“Without this algorithm, the 18,000 patients who had algorithm-directed further testing would have had to go back to the [primary care practitioner] to obtain the additional tests, and the [primary care practitioner] would need to interpret them too,” said Damien Leith, MD, trainee hepatologist at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, Scotland, who presented the findings. “iLFTs ensure the right patients get automated, appropriate follow-up testing and subsequent recommendation of referral to secondary care if necessary, and importantly iLFT helps the primary care practitioner identify the cause of chronic liver disease.”

SOURCE:

This study was presented on June 6, 2024 at the EASL Congress 2024 (abstract OS-007-YI).

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include the need for further refinement of the algorithm to increase the proportion of positive etiologic iLFT outcomes. More analysis is needed to optimize the cost-effectiveness of iLFT.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Leith reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASL 2024

FDA OKs Iqirvo, First-in-Class PPAR Treatment for Primary Biliary Cholangitis

in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in adults who do not respond adequately to UDCA or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.

PBC is a rare, chronic cholestatic liver disease that destroys interlobular bile ducts and leads to cholestasis and liver fibrosis. Left untreated, the disease can worsen over time, leading to cirrhosis and liver transplant and, in some cases, premature death. PBC also harms quality of life, with patients often experiencing severe fatigue and pruritus.

Iqirvo, an oral dual peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and delta agonist, is the first new drug approved in nearly a decade for treatment of PBC.

Accelerated approval of Iqirvo for PBC was based on data from the phase 3 ELATIVE trial published last year in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial randomly assigned patients with PBC who had an inadequate response to or unacceptable side effects with UDCA to receive either once-daily elafibranor (80 mg) or placebo.

The primary endpoint was a biochemical response, defined as an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level < 1.67 times the upper limit of the normal range, with a reduction ≥ 15% from baseline, as well as normal total bilirubin levels.

Among 161 patients, a biochemical response was seen in 55 of 108 (51%) who received elafibranor vs 2 of 53 (4%) who received placebo.

At week 52, the ALP level normalized in 15% of patients in the elafibranor group and none of the patients in the placebo group.

In a news release announcing approval of Iqirvo, the company notes that improvement in survival and prevention of liver decompensation events have not been demonstrated and that continued approval for PBC may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

The most common adverse effects with Iqirvo, reported in ≥ 10% of study participants, were weight gain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Iqirvo is not recommended for people who have or develop decompensated cirrhosis. Full prescribing information is available online.

The data show that Iqirvo is “an effective second-line treatment for patients with PBC with favorable benefit and risk data,” Kris Kowdley, MD, AGAF, director of the Liver Institute Northwest in Seattle, Washington, and a primary investigator on the ELATIVE study, said in the news release.

The approval of Iqirvo “will allow healthcare providers in the US to address an unmet need with the potential to significantly reduce ALP levels for our patients with PBC,” Dr. Kowdley said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in adults who do not respond adequately to UDCA or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.

PBC is a rare, chronic cholestatic liver disease that destroys interlobular bile ducts and leads to cholestasis and liver fibrosis. Left untreated, the disease can worsen over time, leading to cirrhosis and liver transplant and, in some cases, premature death. PBC also harms quality of life, with patients often experiencing severe fatigue and pruritus.

Iqirvo, an oral dual peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and delta agonist, is the first new drug approved in nearly a decade for treatment of PBC.

Accelerated approval of Iqirvo for PBC was based on data from the phase 3 ELATIVE trial published last year in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial randomly assigned patients with PBC who had an inadequate response to or unacceptable side effects with UDCA to receive either once-daily elafibranor (80 mg) or placebo.

The primary endpoint was a biochemical response, defined as an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level < 1.67 times the upper limit of the normal range, with a reduction ≥ 15% from baseline, as well as normal total bilirubin levels.

Among 161 patients, a biochemical response was seen in 55 of 108 (51%) who received elafibranor vs 2 of 53 (4%) who received placebo.

At week 52, the ALP level normalized in 15% of patients in the elafibranor group and none of the patients in the placebo group.

In a news release announcing approval of Iqirvo, the company notes that improvement in survival and prevention of liver decompensation events have not been demonstrated and that continued approval for PBC may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

The most common adverse effects with Iqirvo, reported in ≥ 10% of study participants, were weight gain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Iqirvo is not recommended for people who have or develop decompensated cirrhosis. Full prescribing information is available online.

The data show that Iqirvo is “an effective second-line treatment for patients with PBC with favorable benefit and risk data,” Kris Kowdley, MD, AGAF, director of the Liver Institute Northwest in Seattle, Washington, and a primary investigator on the ELATIVE study, said in the news release.

The approval of Iqirvo “will allow healthcare providers in the US to address an unmet need with the potential to significantly reduce ALP levels for our patients with PBC,” Dr. Kowdley said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in adults who do not respond adequately to UDCA or as monotherapy in patients unable to tolerate UDCA.

PBC is a rare, chronic cholestatic liver disease that destroys interlobular bile ducts and leads to cholestasis and liver fibrosis. Left untreated, the disease can worsen over time, leading to cirrhosis and liver transplant and, in some cases, premature death. PBC also harms quality of life, with patients often experiencing severe fatigue and pruritus.

Iqirvo, an oral dual peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and delta agonist, is the first new drug approved in nearly a decade for treatment of PBC.

Accelerated approval of Iqirvo for PBC was based on data from the phase 3 ELATIVE trial published last year in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial randomly assigned patients with PBC who had an inadequate response to or unacceptable side effects with UDCA to receive either once-daily elafibranor (80 mg) or placebo.

The primary endpoint was a biochemical response, defined as an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level < 1.67 times the upper limit of the normal range, with a reduction ≥ 15% from baseline, as well as normal total bilirubin levels.

Among 161 patients, a biochemical response was seen in 55 of 108 (51%) who received elafibranor vs 2 of 53 (4%) who received placebo.

At week 52, the ALP level normalized in 15% of patients in the elafibranor group and none of the patients in the placebo group.

In a news release announcing approval of Iqirvo, the company notes that improvement in survival and prevention of liver decompensation events have not been demonstrated and that continued approval for PBC may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

The most common adverse effects with Iqirvo, reported in ≥ 10% of study participants, were weight gain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Iqirvo is not recommended for people who have or develop decompensated cirrhosis. Full prescribing information is available online.

The data show that Iqirvo is “an effective second-line treatment for patients with PBC with favorable benefit and risk data,” Kris Kowdley, MD, AGAF, director of the Liver Institute Northwest in Seattle, Washington, and a primary investigator on the ELATIVE study, said in the news release.

The approval of Iqirvo “will allow healthcare providers in the US to address an unmet need with the potential to significantly reduce ALP levels for our patients with PBC,” Dr. Kowdley said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FMT Could Prevent Recurrence of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients With Cirrhosis

MILAN — , results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial show.

“Not only was FMT more beneficial, but also it didn’t matter which route of administration was used — oral or enema — which is good because people don’t really like enemas,” said Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, professor, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and hepatologist at Richmond VA Medical Center.

Donor background (including vegan or omnivore) and dose range also did not affect the efficacy of FMT, Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj presented the findings (Abstract GS-001) at the opening session of the annual European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2024.

Hepatic encephalopathy is a complication of advanced liver disease that causes a dementia-like state. Standard treatment with lactulose and rifaximin often results in a lack of patient response, meaning the patient is constantly being readmitted to the hospital, Dr. Bajaj said.

“This is a burden for the family as well as the patients,” and is very difficult to manage from a clinical and psychosocial perspective, he said in an interview.

With FMT, “we are transferring an ecosystem of good microbes,” which modifies the gut microbiome in patients with advanced liver disease and reduces associated brain toxicity, Dr. Bajaj explained.

Resetting the Gut

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled a total of 60 patients with cirrhosis who had experienced hepatic encephalopathy. Aged 61-65 years, participants had Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores of 12-13, all were taking lactulose and rifaximin, and all had experienced their last hepatic encephalopathy episode 8-13 months prior.

Participants had similar baseline cognition, Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), and cirrhosis severity. Those with recent infections, taking other antibiotics, with a MELD score > 22, had received a transplant, or were immunosuppressed were excluded.

Study participants were divided into four dose administration groups (n = 15 each): oral and enema active FMT therapy (group 1), oral active FMT and enema placebo (group 2), oral placebo and enema active FMT (group 3), and oral and enema placebo (group 4).

The range of FMT dose frequency was zero (all placebo), or one, two, or three FMT administrations, each given 1 month apart.

Two thirds of those receiving active FMT were given omnivore-donor FMT, and one third were given vegan-donor FMT, in addition to receiving standard of care.

“Colony-forming units were standard and the same whether given via oral capsule or enema,” Dr. Bajaj said. This is “similar to what we used in our phase 1 study.”

Intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed with 6-month data. The primary outcomes were safety and hepatic encephalopathy recurrence defined as ≥ grade 2 on West-Haven criteria. Secondary outcomes included other adverse events, changes in infections, severity of cirrhosis and cognition, and patient-reported outcomes. A statistical regression for hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was also performed. Patients were followed for 6 months or until death.

One Dose of FMT Better Than None

Hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was highest (40%) in group 4 patients, compared with those in group 1 (13%), group 2 (13%), and group 3 (0%), as were liver-related hospitalizations (47% vs 7%-20%).

SIP total/physical and psych scores improved with FMT (P = .003).

When all patients were included in the analysis, the hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was related to dose number (odds radio [OR], 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.79; P = .02), male sex (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.03-0.89; P = .04), and physical SIP (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.10, P = .05). However, when analyzing results from FMT recipients only, FMT dose, route of administration, and donor source were not found to affect recurrence.

Of those on placebo alone, six patients (40%) had a recurrence, compared with four on FMT (8.8%) in the combined FMT groups.

“As long as a patient received at least one FMT dose, they had a better response than a patient who had none,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Six patients dropped out; two in group 1 died after hepatic encephalopathy and falls, and one in group 2 died after a seizure. Three others did not return for follow-up visits. Four patients developed infections, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, cholecystitis, and cellulitis, all unrelated to FMT.

“I think many patients in Western countries are underserved because apart from lactulose and rifaximin, there is little else to give them,” Dr. Bajaj said. “The assumption is because rifaximin kills everything, we shouldn’t give FMT. But here, we administered it to a harsh and hostile wasteland of microbiota, and it still got a toehold and generated a reduction in hepatic encephalopathy.”

He pointed out that in smaller prior studies, the effects lasted up to 1 year.

Setting the Stage for Phase 3 Trials

Dr. Bajaj noted that this phase 2 study sets the stage for larger phase 3 trials in patients not responding to first-line therapy.

“Given how well-tolerated and effective FMT appears to be in these patients, if the larger phase 3 trial shows similar results, I can imagine FMT becoming a standard therapy,” said Colleen R. Kelly, MD, AGAF, gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

This study was built on Dr. Bajaj’s prior work that established the safety of FMT by enema, she added, stressing that this new research was incredibly important in these immunocompromised patients who are at higher risk for infection transmission.

That the administration route doesn’t matter is also an important finding as oral administration is much more feasible than enema, said Dr. Kelly, who went on to point out the importance of finding an alternative to rifaximin and lactulose, which are often poorly tolerated.

The study highlights the central role played by the gut microbiota in dysbiosis in the pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy, Dr. Kelly said. “It is another exciting example of how gut microbiota can be manipulated to treat disease.”

Dr. Bajaj and Dr. Kelly report no relevant financial relationships to this study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN — , results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial show.

“Not only was FMT more beneficial, but also it didn’t matter which route of administration was used — oral or enema — which is good because people don’t really like enemas,” said Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, professor, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and hepatologist at Richmond VA Medical Center.

Donor background (including vegan or omnivore) and dose range also did not affect the efficacy of FMT, Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj presented the findings (Abstract GS-001) at the opening session of the annual European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2024.

Hepatic encephalopathy is a complication of advanced liver disease that causes a dementia-like state. Standard treatment with lactulose and rifaximin often results in a lack of patient response, meaning the patient is constantly being readmitted to the hospital, Dr. Bajaj said.

“This is a burden for the family as well as the patients,” and is very difficult to manage from a clinical and psychosocial perspective, he said in an interview.

With FMT, “we are transferring an ecosystem of good microbes,” which modifies the gut microbiome in patients with advanced liver disease and reduces associated brain toxicity, Dr. Bajaj explained.

Resetting the Gut

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled a total of 60 patients with cirrhosis who had experienced hepatic encephalopathy. Aged 61-65 years, participants had Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores of 12-13, all were taking lactulose and rifaximin, and all had experienced their last hepatic encephalopathy episode 8-13 months prior.

Participants had similar baseline cognition, Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), and cirrhosis severity. Those with recent infections, taking other antibiotics, with a MELD score > 22, had received a transplant, or were immunosuppressed were excluded.

Study participants were divided into four dose administration groups (n = 15 each): oral and enema active FMT therapy (group 1), oral active FMT and enema placebo (group 2), oral placebo and enema active FMT (group 3), and oral and enema placebo (group 4).

The range of FMT dose frequency was zero (all placebo), or one, two, or three FMT administrations, each given 1 month apart.

Two thirds of those receiving active FMT were given omnivore-donor FMT, and one third were given vegan-donor FMT, in addition to receiving standard of care.

“Colony-forming units were standard and the same whether given via oral capsule or enema,” Dr. Bajaj said. This is “similar to what we used in our phase 1 study.”

Intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed with 6-month data. The primary outcomes were safety and hepatic encephalopathy recurrence defined as ≥ grade 2 on West-Haven criteria. Secondary outcomes included other adverse events, changes in infections, severity of cirrhosis and cognition, and patient-reported outcomes. A statistical regression for hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was also performed. Patients were followed for 6 months or until death.

One Dose of FMT Better Than None

Hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was highest (40%) in group 4 patients, compared with those in group 1 (13%), group 2 (13%), and group 3 (0%), as were liver-related hospitalizations (47% vs 7%-20%).

SIP total/physical and psych scores improved with FMT (P = .003).

When all patients were included in the analysis, the hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was related to dose number (odds radio [OR], 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.79; P = .02), male sex (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.03-0.89; P = .04), and physical SIP (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.10, P = .05). However, when analyzing results from FMT recipients only, FMT dose, route of administration, and donor source were not found to affect recurrence.

Of those on placebo alone, six patients (40%) had a recurrence, compared with four on FMT (8.8%) in the combined FMT groups.

“As long as a patient received at least one FMT dose, they had a better response than a patient who had none,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Six patients dropped out; two in group 1 died after hepatic encephalopathy and falls, and one in group 2 died after a seizure. Three others did not return for follow-up visits. Four patients developed infections, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, cholecystitis, and cellulitis, all unrelated to FMT.

“I think many patients in Western countries are underserved because apart from lactulose and rifaximin, there is little else to give them,” Dr. Bajaj said. “The assumption is because rifaximin kills everything, we shouldn’t give FMT. But here, we administered it to a harsh and hostile wasteland of microbiota, and it still got a toehold and generated a reduction in hepatic encephalopathy.”

He pointed out that in smaller prior studies, the effects lasted up to 1 year.

Setting the Stage for Phase 3 Trials

Dr. Bajaj noted that this phase 2 study sets the stage for larger phase 3 trials in patients not responding to first-line therapy.

“Given how well-tolerated and effective FMT appears to be in these patients, if the larger phase 3 trial shows similar results, I can imagine FMT becoming a standard therapy,” said Colleen R. Kelly, MD, AGAF, gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

This study was built on Dr. Bajaj’s prior work that established the safety of FMT by enema, she added, stressing that this new research was incredibly important in these immunocompromised patients who are at higher risk for infection transmission.

That the administration route doesn’t matter is also an important finding as oral administration is much more feasible than enema, said Dr. Kelly, who went on to point out the importance of finding an alternative to rifaximin and lactulose, which are often poorly tolerated.

The study highlights the central role played by the gut microbiota in dysbiosis in the pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy, Dr. Kelly said. “It is another exciting example of how gut microbiota can be manipulated to treat disease.”

Dr. Bajaj and Dr. Kelly report no relevant financial relationships to this study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN — , results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial show.

“Not only was FMT more beneficial, but also it didn’t matter which route of administration was used — oral or enema — which is good because people don’t really like enemas,” said Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, professor, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and hepatologist at Richmond VA Medical Center.

Donor background (including vegan or omnivore) and dose range also did not affect the efficacy of FMT, Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj presented the findings (Abstract GS-001) at the opening session of the annual European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Congress 2024.

Hepatic encephalopathy is a complication of advanced liver disease that causes a dementia-like state. Standard treatment with lactulose and rifaximin often results in a lack of patient response, meaning the patient is constantly being readmitted to the hospital, Dr. Bajaj said.

“This is a burden for the family as well as the patients,” and is very difficult to manage from a clinical and psychosocial perspective, he said in an interview.

With FMT, “we are transferring an ecosystem of good microbes,” which modifies the gut microbiome in patients with advanced liver disease and reduces associated brain toxicity, Dr. Bajaj explained.

Resetting the Gut

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled a total of 60 patients with cirrhosis who had experienced hepatic encephalopathy. Aged 61-65 years, participants had Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores of 12-13, all were taking lactulose and rifaximin, and all had experienced their last hepatic encephalopathy episode 8-13 months prior.

Participants had similar baseline cognition, Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), and cirrhosis severity. Those with recent infections, taking other antibiotics, with a MELD score > 22, had received a transplant, or were immunosuppressed were excluded.

Study participants were divided into four dose administration groups (n = 15 each): oral and enema active FMT therapy (group 1), oral active FMT and enema placebo (group 2), oral placebo and enema active FMT (group 3), and oral and enema placebo (group 4).

The range of FMT dose frequency was zero (all placebo), or one, two, or three FMT administrations, each given 1 month apart.

Two thirds of those receiving active FMT were given omnivore-donor FMT, and one third were given vegan-donor FMT, in addition to receiving standard of care.

“Colony-forming units were standard and the same whether given via oral capsule or enema,” Dr. Bajaj said. This is “similar to what we used in our phase 1 study.”

Intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed with 6-month data. The primary outcomes were safety and hepatic encephalopathy recurrence defined as ≥ grade 2 on West-Haven criteria. Secondary outcomes included other adverse events, changes in infections, severity of cirrhosis and cognition, and patient-reported outcomes. A statistical regression for hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was also performed. Patients were followed for 6 months or until death.

One Dose of FMT Better Than None

Hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was highest (40%) in group 4 patients, compared with those in group 1 (13%), group 2 (13%), and group 3 (0%), as were liver-related hospitalizations (47% vs 7%-20%).

SIP total/physical and psych scores improved with FMT (P = .003).

When all patients were included in the analysis, the hepatic encephalopathy recurrence was related to dose number (odds radio [OR], 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.79; P = .02), male sex (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.03-0.89; P = .04), and physical SIP (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.10, P = .05). However, when analyzing results from FMT recipients only, FMT dose, route of administration, and donor source were not found to affect recurrence.

Of those on placebo alone, six patients (40%) had a recurrence, compared with four on FMT (8.8%) in the combined FMT groups.

“As long as a patient received at least one FMT dose, they had a better response than a patient who had none,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Six patients dropped out; two in group 1 died after hepatic encephalopathy and falls, and one in group 2 died after a seizure. Three others did not return for follow-up visits. Four patients developed infections, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, cholecystitis, and cellulitis, all unrelated to FMT.

“I think many patients in Western countries are underserved because apart from lactulose and rifaximin, there is little else to give them,” Dr. Bajaj said. “The assumption is because rifaximin kills everything, we shouldn’t give FMT. But here, we administered it to a harsh and hostile wasteland of microbiota, and it still got a toehold and generated a reduction in hepatic encephalopathy.”

He pointed out that in smaller prior studies, the effects lasted up to 1 year.

Setting the Stage for Phase 3 Trials

Dr. Bajaj noted that this phase 2 study sets the stage for larger phase 3 trials in patients not responding to first-line therapy.

“Given how well-tolerated and effective FMT appears to be in these patients, if the larger phase 3 trial shows similar results, I can imagine FMT becoming a standard therapy,” said Colleen R. Kelly, MD, AGAF, gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

This study was built on Dr. Bajaj’s prior work that established the safety of FMT by enema, she added, stressing that this new research was incredibly important in these immunocompromised patients who are at higher risk for infection transmission.

That the administration route doesn’t matter is also an important finding as oral administration is much more feasible than enema, said Dr. Kelly, who went on to point out the importance of finding an alternative to rifaximin and lactulose, which are often poorly tolerated.

The study highlights the central role played by the gut microbiota in dysbiosis in the pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy, Dr. Kelly said. “It is another exciting example of how gut microbiota can be manipulated to treat disease.”

Dr. Bajaj and Dr. Kelly report no relevant financial relationships to this study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASL 2024

FIB-4 Index Misclassifies Many Patients

, potentially impacting clinical decisions, according to investigators.

These findings call for a cautious interpretation of low-risk FIB-4 results among patients at greatest risk of misclassification, and/or use of alternative assessment strategies, reported Mazen Noureddin, MD, MHSc, of Houston Methodist Hospital, and coauthors.

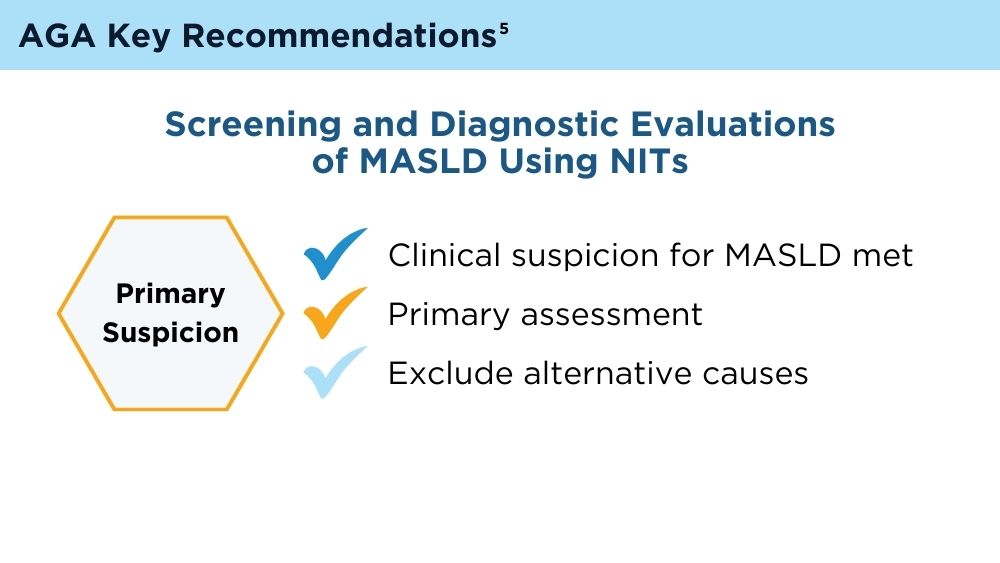

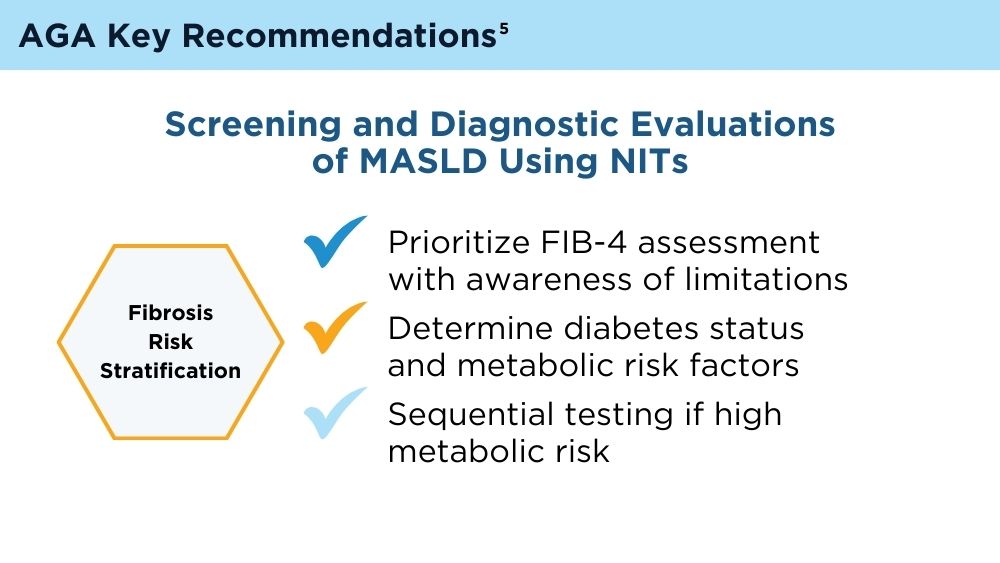

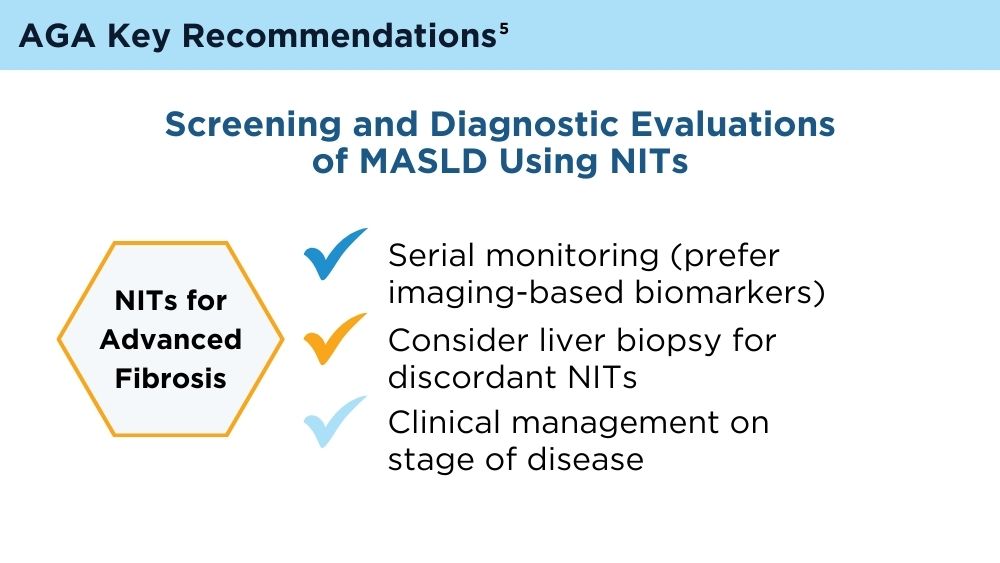

“Currently, the AGA/AASLD Pathways recommends identifying patients at risk for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), then using sequential testing with FIB-4 followed by FibroScan to risk-stratify patients,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Yet the performance of the FIB-4 index in this context remains unclear.

“Previous studies have shown FIB-4 to have low accuracy for screening liver fibrosis, especially among obese and diabetic patients,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, there is a concern that classifying patients with FIB-4 can lead to misclassification and missed diagnosis.”

To explore this concern, Dr. Noureddin and colleagues turned to data from the 2017-2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, including 5285 subjects at risk for MASLD. Exclusions were made for those with excessive alcohol intake or other liver diseases, resulting in a final cohort of 3741 individuals.

All subjects were classified as low-, indeterminate-, or high-risk for advanced liver fibrosis based on FIB-4 scores. These scores were then compared with liver stiffness measurements (LSM) obtained through transient elastography (FibroScan).

Out of 2776 subjects classified as low-risk by FIB-4, 277 (10%) were reclassified as higher risk by LSM, including 75 (2.7%) who were found to be at high risk. Out of 879 subjects with indeterminate FIB-4 scores, 37 (4.2%) were at high risk according to LSM. Finally, among the 86 subjects classified as high risk by FIB-4, 68 (79.1%) were reclassified as lower risk by LSM, including 54 (62.8%) who were deemed low risk.

Subjects misclassified as low risk by FIB-4 were typically older and had higher waist circumferences, body mass indices, glycohemoglobin A1c levels, fasting glucose levels, liver enzyme levels, diastolic blood pressures, controlled attenuation parameter scores, white blood cell counts, and alkaline phosphatase levels, but lower high-density lipoprotein and albumin levels (all P less than .05). They were also more likely to have prediabetes or diabetes.

“[I]t is important to acknowledge that 10% of the subjects were misclassified as low risk by FIB-4,” Dr. Noureddin and colleagues wrote, including 2.7% of patients who were actually high risk. “This misclassification of high-risk patients can lead to missed diagnoses, delaying crucial medical treatments or lifestyle interventions.”

They therefore suggested cautious interpretation of low-risk FIB-4 results among patients with factors predicting misclassification, or even use of alternative diagnostic strategies.

“Some possible alternatives to FIB-4 include new serum tests such NIS-2+, MASEF, SAFE score, and machine learning methods,” Dr. Noureddin and colleagues wrote. “However, additional confirmatory and cost-effective studies are required to validate the effectiveness of these tests, including studies conducted on the general population.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Corcept, Galectin, and others.

, potentially impacting clinical decisions, according to investigators.

These findings call for a cautious interpretation of low-risk FIB-4 results among patients at greatest risk of misclassification, and/or use of alternative assessment strategies, reported Mazen Noureddin, MD, MHSc, of Houston Methodist Hospital, and coauthors.

“Currently, the AGA/AASLD Pathways recommends identifying patients at risk for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), then using sequential testing with FIB-4 followed by FibroScan to risk-stratify patients,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Yet the performance of the FIB-4 index in this context remains unclear.

“Previous studies have shown FIB-4 to have low accuracy for screening liver fibrosis, especially among obese and diabetic patients,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, there is a concern that classifying patients with FIB-4 can lead to misclassification and missed diagnosis.”

To explore this concern, Dr. Noureddin and colleagues turned to data from the 2017-2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, including 5285 subjects at risk for MASLD. Exclusions were made for those with excessive alcohol intake or other liver diseases, resulting in a final cohort of 3741 individuals.

All subjects were classified as low-, indeterminate-, or high-risk for advanced liver fibrosis based on FIB-4 scores. These scores were then compared with liver stiffness measurements (LSM) obtained through transient elastography (FibroScan).

Out of 2776 subjects classified as low-risk by FIB-4, 277 (10%) were reclassified as higher risk by LSM, including 75 (2.7%) who were found to be at high risk. Out of 879 subjects with indeterminate FIB-4 scores, 37 (4.2%) were at high risk according to LSM. Finally, among the 86 subjects classified as high risk by FIB-4, 68 (79.1%) were reclassified as lower risk by LSM, including 54 (62.8%) who were deemed low risk.

Subjects misclassified as low risk by FIB-4 were typically older and had higher waist circumferences, body mass indices, glycohemoglobin A1c levels, fasting glucose levels, liver enzyme levels, diastolic blood pressures, controlled attenuation parameter scores, white blood cell counts, and alkaline phosphatase levels, but lower high-density lipoprotein and albumin levels (all P less than .05). They were also more likely to have prediabetes or diabetes.

“[I]t is important to acknowledge that 10% of the subjects were misclassified as low risk by FIB-4,” Dr. Noureddin and colleagues wrote, including 2.7% of patients who were actually high risk. “This misclassification of high-risk patients can lead to missed diagnoses, delaying crucial medical treatments or lifestyle interventions.”

They therefore suggested cautious interpretation of low-risk FIB-4 results among patients with factors predicting misclassification, or even use of alternative diagnostic strategies.

“Some possible alternatives to FIB-4 include new serum tests such NIS-2+, MASEF, SAFE score, and machine learning methods,” Dr. Noureddin and colleagues wrote. “However, additional confirmatory and cost-effective studies are required to validate the effectiveness of these tests, including studies conducted on the general population.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Corcept, Galectin, and others.

, potentially impacting clinical decisions, according to investigators.

These findings call for a cautious interpretation of low-risk FIB-4 results among patients at greatest risk of misclassification, and/or use of alternative assessment strategies, reported Mazen Noureddin, MD, MHSc, of Houston Methodist Hospital, and coauthors.

“Currently, the AGA/AASLD Pathways recommends identifying patients at risk for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), then using sequential testing with FIB-4 followed by FibroScan to risk-stratify patients,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Yet the performance of the FIB-4 index in this context remains unclear.

“Previous studies have shown FIB-4 to have low accuracy for screening liver fibrosis, especially among obese and diabetic patients,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, there is a concern that classifying patients with FIB-4 can lead to misclassification and missed diagnosis.”

To explore this concern, Dr. Noureddin and colleagues turned to data from the 2017-2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, including 5285 subjects at risk for MASLD. Exclusions were made for those with excessive alcohol intake or other liver diseases, resulting in a final cohort of 3741 individuals.

All subjects were classified as low-, indeterminate-, or high-risk for advanced liver fibrosis based on FIB-4 scores. These scores were then compared with liver stiffness measurements (LSM) obtained through transient elastography (FibroScan).

Out of 2776 subjects classified as low-risk by FIB-4, 277 (10%) were reclassified as higher risk by LSM, including 75 (2.7%) who were found to be at high risk. Out of 879 subjects with indeterminate FIB-4 scores, 37 (4.2%) were at high risk according to LSM. Finally, among the 86 subjects classified as high risk by FIB-4, 68 (79.1%) were reclassified as lower risk by LSM, including 54 (62.8%) who were deemed low risk.

Subjects misclassified as low risk by FIB-4 were typically older and had higher waist circumferences, body mass indices, glycohemoglobin A1c levels, fasting glucose levels, liver enzyme levels, diastolic blood pressures, controlled attenuation parameter scores, white blood cell counts, and alkaline phosphatase levels, but lower high-density lipoprotein and albumin levels (all P less than .05). They were also more likely to have prediabetes or diabetes.

“[I]t is important to acknowledge that 10% of the subjects were misclassified as low risk by FIB-4,” Dr. Noureddin and colleagues wrote, including 2.7% of patients who were actually high risk. “This misclassification of high-risk patients can lead to missed diagnoses, delaying crucial medical treatments or lifestyle interventions.”

They therefore suggested cautious interpretation of low-risk FIB-4 results among patients with factors predicting misclassification, or even use of alternative diagnostic strategies.

“Some possible alternatives to FIB-4 include new serum tests such NIS-2+, MASEF, SAFE score, and machine learning methods,” Dr. Noureddin and colleagues wrote. “However, additional confirmatory and cost-effective studies are required to validate the effectiveness of these tests, including studies conducted on the general population.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Corcept, Galectin, and others.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

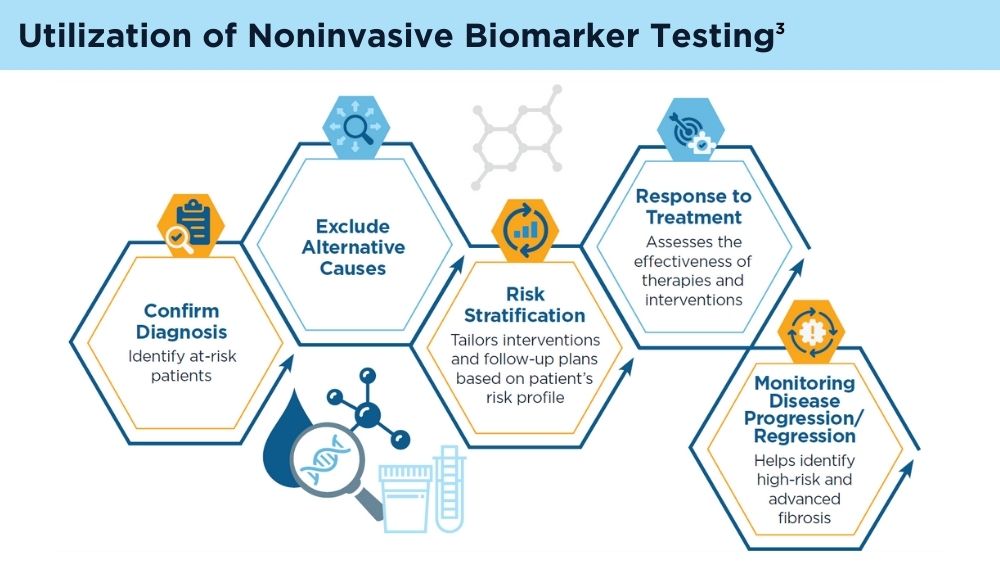

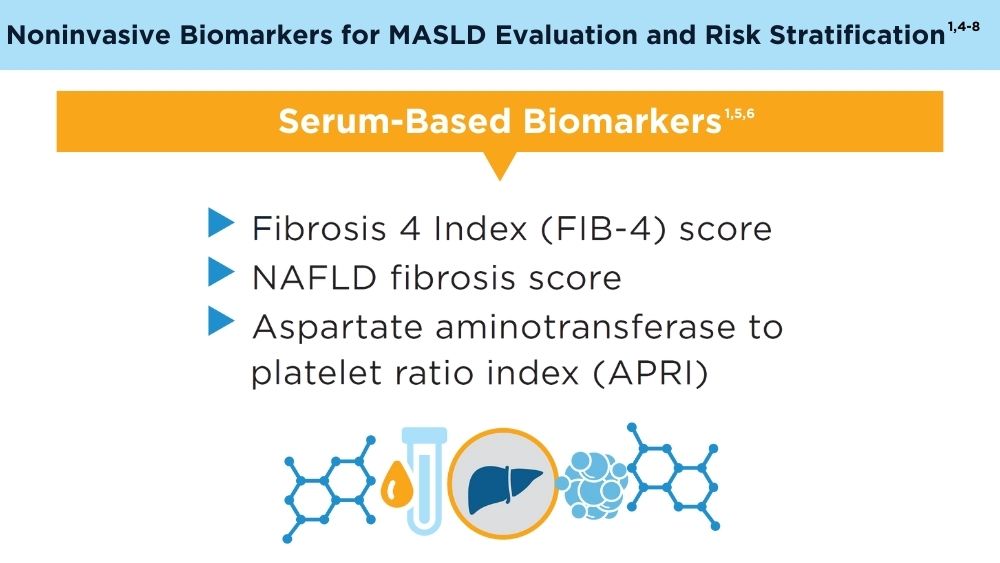

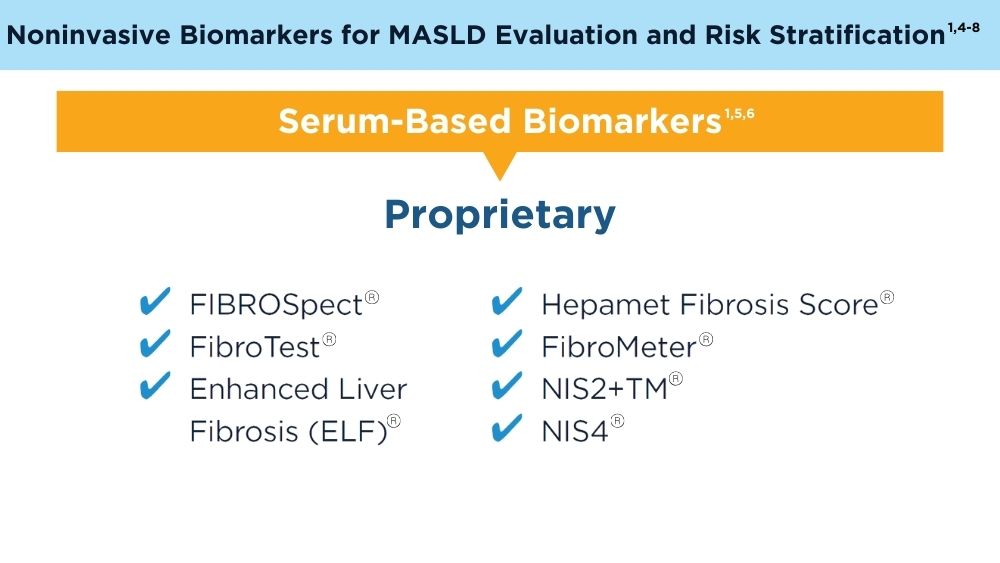

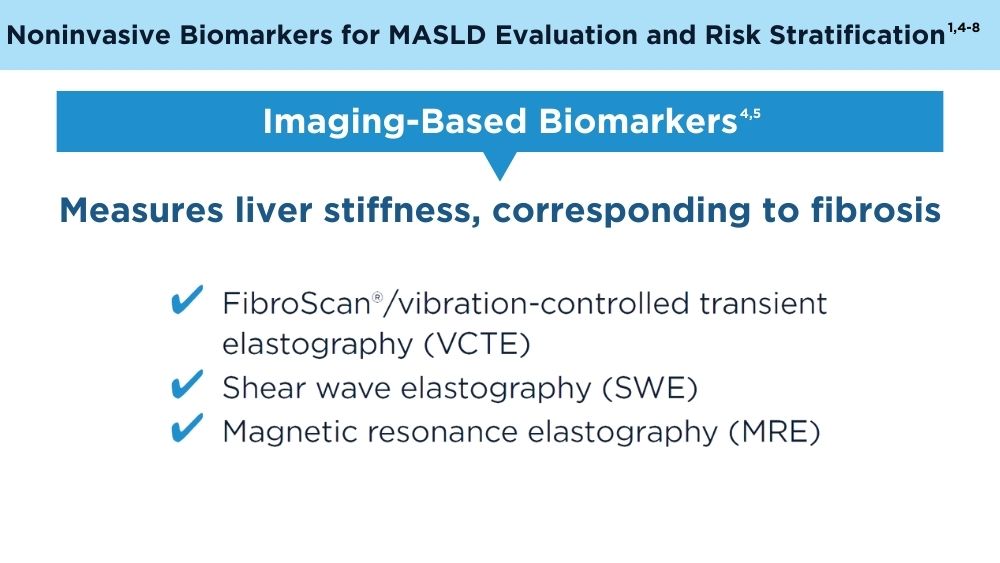

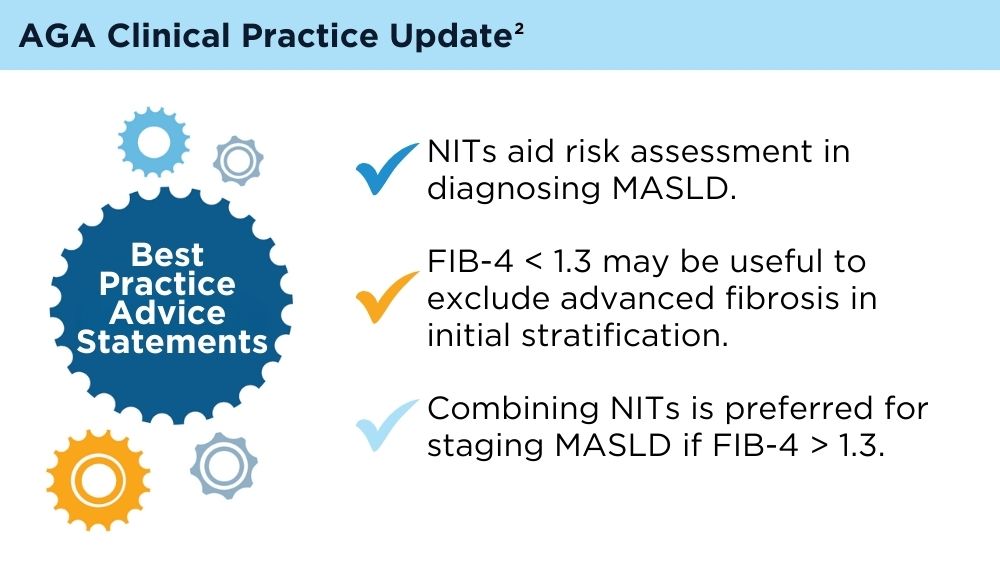

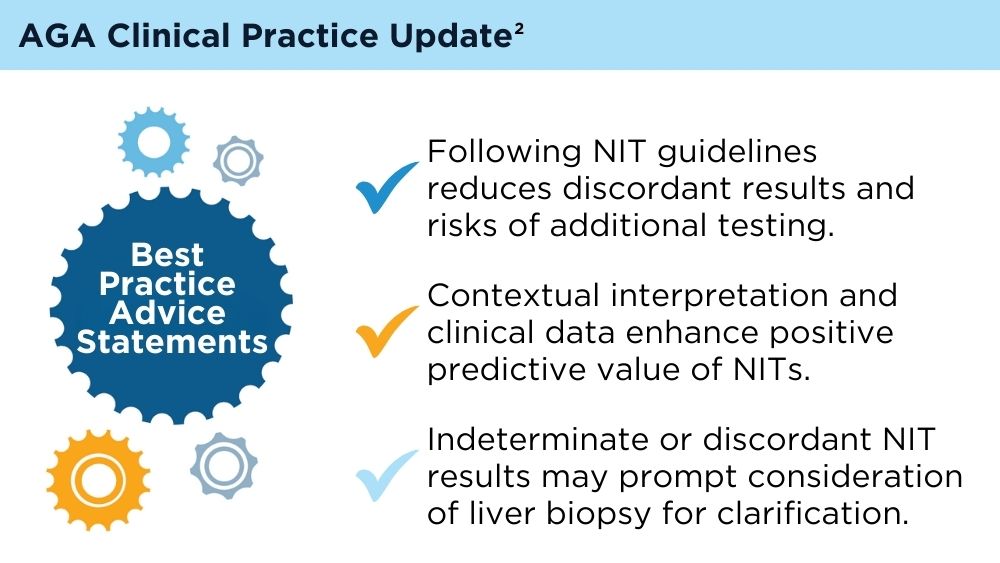

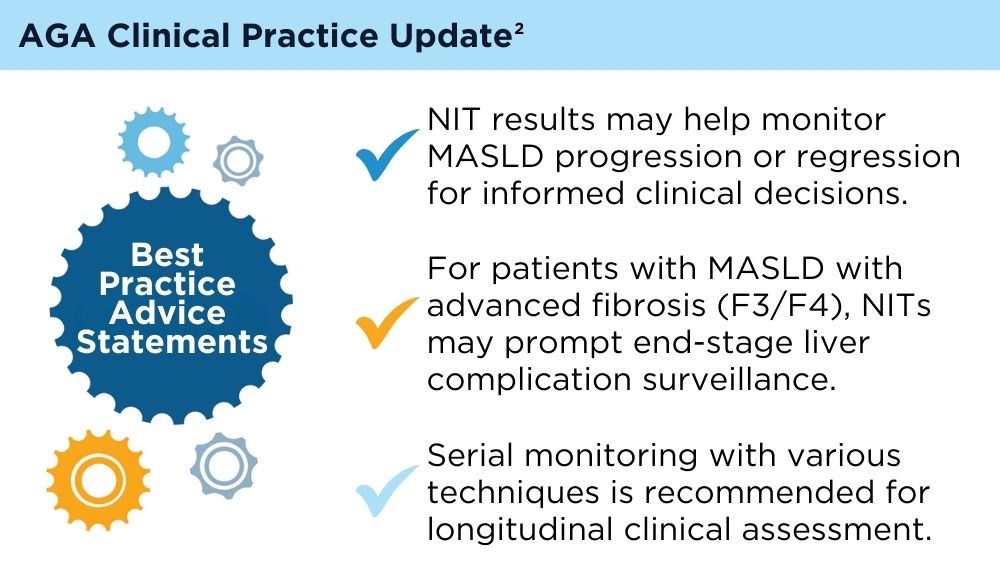

Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78(6):1966-1986. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520

Wattacheril JJ, Abdelmalek MF, Lim JK, Sanyal AJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(4):1080-1088. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.06.013

Di Mauro S, Scamporrino A, Filippello A, et al. Clinical and Molecular Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Staging of NAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11905. Published 2021 Nov 2. doi:10.3390/ijms222111905

Hsu C, Caussy C, Imajo K, et al. Magnetic Resonance vs Transient Elastography Analysis of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of Individual Participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):630-637.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.059

Ilagan-Ying YC, Banini BA, Do A, Lam R, Lim JK. Screening, Diagnosis, and Staging of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Application of Society Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25(10):213-224. doi:10.1007/s11894-023-00883-8

Chen W, Gao Y, Xie W, et al. Genome-wide association analyses provide genetic and biochemical insights into natural variation in rice metabolism. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):714-721. doi:10.1038/ng.3007

Wu YL, Kumar R, Wang MF, et al. Validation of conventional non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(34):5753-5763. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i34.5753

Kaneva AM, Bojko ER. Fatty liver index (FLI): more than a marker of hepatic steatosis. J Physiol Biochem. Published online October 25, 2023. doi:10.1007/s13105-023-00991-z

Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78(6):1966-1986. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520

Wattacheril JJ, Abdelmalek MF, Lim JK, Sanyal AJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(4):1080-1088. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.06.013

Di Mauro S, Scamporrino A, Filippello A, et al. Clinical and Molecular Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Staging of NAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11905. Published 2021 Nov 2. doi:10.3390/ijms222111905

Hsu C, Caussy C, Imajo K, et al. Magnetic Resonance vs Transient Elastography Analysis of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of Individual Participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):630-637.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.059

Ilagan-Ying YC, Banini BA, Do A, Lam R, Lim JK. Screening, Diagnosis, and Staging of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Application of Society Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25(10):213-224. doi:10.1007/s11894-023-00883-8

Chen W, Gao Y, Xie W, et al. Genome-wide association analyses provide genetic and biochemical insights into natural variation in rice metabolism. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):714-721. doi:10.1038/ng.3007

Wu YL, Kumar R, Wang MF, et al. Validation of conventional non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(34):5753-5763. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i34.5753

Kaneva AM, Bojko ER. Fatty liver index (FLI): more than a marker of hepatic steatosis. J Physiol Biochem. Published online October 25, 2023. doi:10.1007/s13105-023-00991-z

Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78(6):1966-1986. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520

Wattacheril JJ, Abdelmalek MF, Lim JK, Sanyal AJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(4):1080-1088. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.06.013

Di Mauro S, Scamporrino A, Filippello A, et al. Clinical and Molecular Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Staging of NAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11905. Published 2021 Nov 2. doi:10.3390/ijms222111905

Hsu C, Caussy C, Imajo K, et al. Magnetic Resonance vs Transient Elastography Analysis of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of Individual Participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):630-637.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.059

Ilagan-Ying YC, Banini BA, Do A, Lam R, Lim JK. Screening, Diagnosis, and Staging of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Application of Society Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25(10):213-224. doi:10.1007/s11894-023-00883-8

Chen W, Gao Y, Xie W, et al. Genome-wide association analyses provide genetic and biochemical insights into natural variation in rice metabolism. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):714-721. doi:10.1038/ng.3007

Wu YL, Kumar R, Wang MF, et al. Validation of conventional non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(34):5753-5763. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i34.5753

Kaneva AM, Bojko ER. Fatty liver index (FLI): more than a marker of hepatic steatosis. J Physiol Biochem. Published online October 25, 2023. doi:10.1007/s13105-023-00991-z

Emerging Evidence Supports Dietary Management of MASLD Through Gut-Liver Axis

WASHINGTON — , according to a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

For instance, patients with MASLD had lower intake of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but higher consumption of added sugars and ultraprocessed foods, which correlated with the associated bacterial species and functional pathways.

“MASLD is an escalating concern globally, which highlights the need for innovative targets for disease prevention and management,” said lead author Georgina Williams, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in diet and gastroenterology at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

“Therapeutic options often rely on lifestyle modifications, with a focus on weight loss,” she said. “Diet is considered a key component of disease management.”

Although calorie restriction with a 3%-5% fat loss is associated with hepatic benefits in MASLD, Dr. Williams noted, researchers have considered whole dietary patterns and the best fit for patients. Aspects of the Mediterranean diet may be effective, as reflected in recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), which highlight dietary components such as limited carbohydrates and saturated fat, along with high fiber and unsaturated fats. The gut microbiome may be essential to consider as well, she said, given MASLD-associated differences in bile acid metabolism, inflammation, and ethanol production.

Dr. Williams and colleagues conducted a retrospective case-control study in an outpatient liver clinic to understand diet and dysbiosis in MASLD, looking at differences in diet, gut microbiota composition, and functional pathways in those with and without MASLD. The researchers investigated daily average intake, serum, and stool samples among 50 people (25 per group) matched for age and gender, comparing fibrosis-4, MASLD severity scores, macronutrients, micronutrients, food groups, metagenomic sequencing, and inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cytokeratin (CK)-18, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

Dietary Characteristics

At baseline, the groups differed by ethnicity, prescription medication use, and body mass index (BMI), where the MASLD group had greater ethnic diversity, medication use, and BMI. In addition, the MASLD group had a zero to mild score of fibrosis.

Overall, energy intake didn’t differ significantly between the two groups. The control group had higher alcohol intake, likely since the MASLD group was recommended to reduce alcohol intake, though the difference was about 5 grams per day. The MASLD group also had less caffeine intake than the control group, as well as slightly lower protein intake, though the differences weren’t statistically significant.

While consumption of total carbohydrates didn’t differ significantly between the groups, participants with MASLD consumed more calories from carbohydrates than did the controls. The MASLD group consumed more calories from added and free sugars and didn’t meet recommendations for dietary fiber.

With particular food groups, participants with MASLD ate significantly fewer whole grains, red and orange fruits, and leafy green vegetables. When consuming fruit, those with MASLD were more likely to drink juice than eat whole fruit. These findings could be relevant when considering high sugar intake and low dietary fiber, Dr. Williams said.

With dietary fat, there were no differences in total fat between the groups, but the fat profiles differed. The control group was significantly more likely to consume omega-3 fatty acids, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The MASLD group was less likely to consume seafood, nuts, seeds, avocado, and olive oil.

With inflammatory markers, hsCRP and CK-18 were increased in MASLD, while IL-1ß was increased in controls, which was consistently associated with higher alcohol intake among the control group. IL-6 and TNF-α didn’t differ between the groups.

Notably, dietary fats were most consistently associated with inflammatory markers, Dr. Williams said, with inflammation being positively associated with saturated fats and negatively associated with unsaturated fats.

Looking at microbiota, the alpha diversity was no different, but the beta diversity was across 162 taxa. Per bacterial species, there was an inverse relationship between MASLD and associations with unsaturated fat, as well as positive indicators of high sugar and fructose intake and low unsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake.

Beyond that, the functional pathways enriched in MASLD were associated with increased sugar and carbohydrates, reduced fiber, and reduced unsaturated fat. Lower butyrate production in MASLD was associated with low intake of nuts, seeds, and unsaturated fat.

In Clinical Practice

Dr. Williams suggested reinforcing AASLD guidelines and looking at diet quality, not just diet quantity. Although an energy deficit remains relevant in MASLD, macronutrient consumption matters across dietary fats, fibers, and sugars.

Future avenues for research include metabolomic pathways related to bile acids and fatty acids, she said, as well as disentangling metabolic syndrome from MASLD outcomes.

Session moderator Olivier Barbier, PhD, professor of pharmacy at Laval University in Quebec, Canada, asked about microbiome differences across countries. Dr. Williams noted the limitations in this study of looking at differences across geography and ethnicity, particularly in Australia, but said the species identified were consistent with those found in most literature globally.

In response to other questions after the presentation, Dr. Williams said supplements (such as omega-3 fatty acids) were included in total intake, and those taking prebiotics or probiotics were excluded from the study. In an upcoming clinical trial, she and colleagues plan to control for household microbiomes as well.

“The premise is that microbiomes are shared between households, so when you’re doing these sorts of large-scale clinical studies, if you’re going to look at the microbiome, then you should control for one of the major confounding variables,” said Mark Sundrud, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Center for Digestive Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Sundrud, who wasn’t involved with this study, presented on the role of bile acids in mucosal immune cell function at DDW.

“We’ve done a collaborative study looking at microbiomes and bile acids in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients versus controls,” which included consideration of households, he said. “We were able to see more intrinsic disease-specific changes.”

Dr. Williams declared no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sundrud has served as a scientific adviser to Sage Therapeutics.

WASHINGTON — , according to a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

For instance, patients with MASLD had lower intake of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but higher consumption of added sugars and ultraprocessed foods, which correlated with the associated bacterial species and functional pathways.

“MASLD is an escalating concern globally, which highlights the need for innovative targets for disease prevention and management,” said lead author Georgina Williams, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in diet and gastroenterology at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

“Therapeutic options often rely on lifestyle modifications, with a focus on weight loss,” she said. “Diet is considered a key component of disease management.”

Although calorie restriction with a 3%-5% fat loss is associated with hepatic benefits in MASLD, Dr. Williams noted, researchers have considered whole dietary patterns and the best fit for patients. Aspects of the Mediterranean diet may be effective, as reflected in recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), which highlight dietary components such as limited carbohydrates and saturated fat, along with high fiber and unsaturated fats. The gut microbiome may be essential to consider as well, she said, given MASLD-associated differences in bile acid metabolism, inflammation, and ethanol production.

Dr. Williams and colleagues conducted a retrospective case-control study in an outpatient liver clinic to understand diet and dysbiosis in MASLD, looking at differences in diet, gut microbiota composition, and functional pathways in those with and without MASLD. The researchers investigated daily average intake, serum, and stool samples among 50 people (25 per group) matched for age and gender, comparing fibrosis-4, MASLD severity scores, macronutrients, micronutrients, food groups, metagenomic sequencing, and inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cytokeratin (CK)-18, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

Dietary Characteristics

At baseline, the groups differed by ethnicity, prescription medication use, and body mass index (BMI), where the MASLD group had greater ethnic diversity, medication use, and BMI. In addition, the MASLD group had a zero to mild score of fibrosis.

Overall, energy intake didn’t differ significantly between the two groups. The control group had higher alcohol intake, likely since the MASLD group was recommended to reduce alcohol intake, though the difference was about 5 grams per day. The MASLD group also had less caffeine intake than the control group, as well as slightly lower protein intake, though the differences weren’t statistically significant.

While consumption of total carbohydrates didn’t differ significantly between the groups, participants with MASLD consumed more calories from carbohydrates than did the controls. The MASLD group consumed more calories from added and free sugars and didn’t meet recommendations for dietary fiber.

With particular food groups, participants with MASLD ate significantly fewer whole grains, red and orange fruits, and leafy green vegetables. When consuming fruit, those with MASLD were more likely to drink juice than eat whole fruit. These findings could be relevant when considering high sugar intake and low dietary fiber, Dr. Williams said.

With dietary fat, there were no differences in total fat between the groups, but the fat profiles differed. The control group was significantly more likely to consume omega-3 fatty acids, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The MASLD group was less likely to consume seafood, nuts, seeds, avocado, and olive oil.

With inflammatory markers, hsCRP and CK-18 were increased in MASLD, while IL-1ß was increased in controls, which was consistently associated with higher alcohol intake among the control group. IL-6 and TNF-α didn’t differ between the groups.

Notably, dietary fats were most consistently associated with inflammatory markers, Dr. Williams said, with inflammation being positively associated with saturated fats and negatively associated with unsaturated fats.

Looking at microbiota, the alpha diversity was no different, but the beta diversity was across 162 taxa. Per bacterial species, there was an inverse relationship between MASLD and associations with unsaturated fat, as well as positive indicators of high sugar and fructose intake and low unsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake.

Beyond that, the functional pathways enriched in MASLD were associated with increased sugar and carbohydrates, reduced fiber, and reduced unsaturated fat. Lower butyrate production in MASLD was associated with low intake of nuts, seeds, and unsaturated fat.

In Clinical Practice

Dr. Williams suggested reinforcing AASLD guidelines and looking at diet quality, not just diet quantity. Although an energy deficit remains relevant in MASLD, macronutrient consumption matters across dietary fats, fibers, and sugars.

Future avenues for research include metabolomic pathways related to bile acids and fatty acids, she said, as well as disentangling metabolic syndrome from MASLD outcomes.

Session moderator Olivier Barbier, PhD, professor of pharmacy at Laval University in Quebec, Canada, asked about microbiome differences across countries. Dr. Williams noted the limitations in this study of looking at differences across geography and ethnicity, particularly in Australia, but said the species identified were consistent with those found in most literature globally.

In response to other questions after the presentation, Dr. Williams said supplements (such as omega-3 fatty acids) were included in total intake, and those taking prebiotics or probiotics were excluded from the study. In an upcoming clinical trial, she and colleagues plan to control for household microbiomes as well.

“The premise is that microbiomes are shared between households, so when you’re doing these sorts of large-scale clinical studies, if you’re going to look at the microbiome, then you should control for one of the major confounding variables,” said Mark Sundrud, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Center for Digestive Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Sundrud, who wasn’t involved with this study, presented on the role of bile acids in mucosal immune cell function at DDW.

“We’ve done a collaborative study looking at microbiomes and bile acids in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients versus controls,” which included consideration of households, he said. “We were able to see more intrinsic disease-specific changes.”

Dr. Williams declared no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sundrud has served as a scientific adviser to Sage Therapeutics.

WASHINGTON — , according to a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

For instance, patients with MASLD had lower intake of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids but higher consumption of added sugars and ultraprocessed foods, which correlated with the associated bacterial species and functional pathways.

“MASLD is an escalating concern globally, which highlights the need for innovative targets for disease prevention and management,” said lead author Georgina Williams, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in diet and gastroenterology at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

“Therapeutic options often rely on lifestyle modifications, with a focus on weight loss,” she said. “Diet is considered a key component of disease management.”

Although calorie restriction with a 3%-5% fat loss is associated with hepatic benefits in MASLD, Dr. Williams noted, researchers have considered whole dietary patterns and the best fit for patients. Aspects of the Mediterranean diet may be effective, as reflected in recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), which highlight dietary components such as limited carbohydrates and saturated fat, along with high fiber and unsaturated fats. The gut microbiome may be essential to consider as well, she said, given MASLD-associated differences in bile acid metabolism, inflammation, and ethanol production.

Dr. Williams and colleagues conducted a retrospective case-control study in an outpatient liver clinic to understand diet and dysbiosis in MASLD, looking at differences in diet, gut microbiota composition, and functional pathways in those with and without MASLD. The researchers investigated daily average intake, serum, and stool samples among 50 people (25 per group) matched for age and gender, comparing fibrosis-4, MASLD severity scores, macronutrients, micronutrients, food groups, metagenomic sequencing, and inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cytokeratin (CK)-18, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

Dietary Characteristics

At baseline, the groups differed by ethnicity, prescription medication use, and body mass index (BMI), where the MASLD group had greater ethnic diversity, medication use, and BMI. In addition, the MASLD group had a zero to mild score of fibrosis.

Overall, energy intake didn’t differ significantly between the two groups. The control group had higher alcohol intake, likely since the MASLD group was recommended to reduce alcohol intake, though the difference was about 5 grams per day. The MASLD group also had less caffeine intake than the control group, as well as slightly lower protein intake, though the differences weren’t statistically significant.

While consumption of total carbohydrates didn’t differ significantly between the groups, participants with MASLD consumed more calories from carbohydrates than did the controls. The MASLD group consumed more calories from added and free sugars and didn’t meet recommendations for dietary fiber.

With particular food groups, participants with MASLD ate significantly fewer whole grains, red and orange fruits, and leafy green vegetables. When consuming fruit, those with MASLD were more likely to drink juice than eat whole fruit. These findings could be relevant when considering high sugar intake and low dietary fiber, Dr. Williams said.

With dietary fat, there were no differences in total fat between the groups, but the fat profiles differed. The control group was significantly more likely to consume omega-3 fatty acids, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The MASLD group was less likely to consume seafood, nuts, seeds, avocado, and olive oil.

With inflammatory markers, hsCRP and CK-18 were increased in MASLD, while IL-1ß was increased in controls, which was consistently associated with higher alcohol intake among the control group. IL-6 and TNF-α didn’t differ between the groups.

Notably, dietary fats were most consistently associated with inflammatory markers, Dr. Williams said, with inflammation being positively associated with saturated fats and negatively associated with unsaturated fats.

Looking at microbiota, the alpha diversity was no different, but the beta diversity was across 162 taxa. Per bacterial species, there was an inverse relationship between MASLD and associations with unsaturated fat, as well as positive indicators of high sugar and fructose intake and low unsaturated fat and dietary fiber intake.

Beyond that, the functional pathways enriched in MASLD were associated with increased sugar and carbohydrates, reduced fiber, and reduced unsaturated fat. Lower butyrate production in MASLD was associated with low intake of nuts, seeds, and unsaturated fat.

In Clinical Practice

Dr. Williams suggested reinforcing AASLD guidelines and looking at diet quality, not just diet quantity. Although an energy deficit remains relevant in MASLD, macronutrient consumption matters across dietary fats, fibers, and sugars.

Future avenues for research include metabolomic pathways related to bile acids and fatty acids, she said, as well as disentangling metabolic syndrome from MASLD outcomes.

Session moderator Olivier Barbier, PhD, professor of pharmacy at Laval University in Quebec, Canada, asked about microbiome differences across countries. Dr. Williams noted the limitations in this study of looking at differences across geography and ethnicity, particularly in Australia, but said the species identified were consistent with those found in most literature globally.

In response to other questions after the presentation, Dr. Williams said supplements (such as omega-3 fatty acids) were included in total intake, and those taking prebiotics or probiotics were excluded from the study. In an upcoming clinical trial, she and colleagues plan to control for household microbiomes as well.

“The premise is that microbiomes are shared between households, so when you’re doing these sorts of large-scale clinical studies, if you’re going to look at the microbiome, then you should control for one of the major confounding variables,” said Mark Sundrud, PhD, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Center for Digestive Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Sundrud, who wasn’t involved with this study, presented on the role of bile acids in mucosal immune cell function at DDW.

“We’ve done a collaborative study looking at microbiomes and bile acids in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients versus controls,” which included consideration of households, he said. “We were able to see more intrinsic disease-specific changes.”

Dr. Williams declared no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sundrud has served as a scientific adviser to Sage Therapeutics.

FROM DDW 2024

Healthy Sleep Linked to Lower Odds for Digestive Diseases

TOPLINE:

Healthier sleep is associated with lower odds of developing a wide range of gastrointestinal conditions, regardless of genetic susceptibility, new research revealed.

METHODOLOGY:

- Due to the widespread prevalence of sleep issues and a growing burden of digestive diseases globally, researchers investigated the association between sleep quality and digestive disorders in a prospective cohort study of 410,586 people in the UK Biobank.

- Five individual sleep behaviors were assessed: sleep duration, insomnia, snoring, daytime sleepiness, and chronotype.

- A healthy sleep was defined as a morning chronotype, 7-8 hours of sleep duration, no self-reported snoring, never or rare insomnia, and a low frequency of daytime sleepiness, for a score of 5/5.

- The study investigators tracked the development of 16 digestive diseases over a mean period of 13.2 years.

- As well as looking at healthy sleep scores, researchers considered genetic susceptibility to gastrointestinal conditions.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 16 digestive diseases looked at, the reduction of risk was highest for irritable bowel syndrome at 50% (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.45-0.57).

- A healthy sleep score was also associated with 37% reduced odds for metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.55-0.71), 35% lower chance for peptic ulcer (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.058-0.74), 34% reduced chance for dyspepsia (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.58-0.75), and a 25% lower risk for diverticulosis (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.71-0.80).

- High genetic risk and poor sleep scores were also associated with increased odds (53% to > 200%) of developing digestive diseases.

- However, healthy sleep reduced the risk for digestive diseases regardless of genetic susceptibility.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings underscore the potential holistic impact of different sleep behaviors in mitigating the risk of digestive diseases in clinical practice,” wrote Shiyi Yu, MD, of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, and colleagues.

Poor sleep can also change our gut microbiome, Dr. Yu told this news organization. If you don’t sleep well, the repair of the gut lining cannot be finished during the night.

SOURCE:

The study was presented at the Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), 2024, annual meeting.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Yu had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Healthier sleep is associated with lower odds of developing a wide range of gastrointestinal conditions, regardless of genetic susceptibility, new research revealed.

METHODOLOGY:

- Due to the widespread prevalence of sleep issues and a growing burden of digestive diseases globally, researchers investigated the association between sleep quality and digestive disorders in a prospective cohort study of 410,586 people in the UK Biobank.

- Five individual sleep behaviors were assessed: sleep duration, insomnia, snoring, daytime sleepiness, and chronotype.

- A healthy sleep was defined as a morning chronotype, 7-8 hours of sleep duration, no self-reported snoring, never or rare insomnia, and a low frequency of daytime sleepiness, for a score of 5/5.

- The study investigators tracked the development of 16 digestive diseases over a mean period of 13.2 years.

- As well as looking at healthy sleep scores, researchers considered genetic susceptibility to gastrointestinal conditions.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 16 digestive diseases looked at, the reduction of risk was highest for irritable bowel syndrome at 50% (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.45-0.57).

- A healthy sleep score was also associated with 37% reduced odds for metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.55-0.71), 35% lower chance for peptic ulcer (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.058-0.74), 34% reduced chance for dyspepsia (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.58-0.75), and a 25% lower risk for diverticulosis (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.71-0.80).

- High genetic risk and poor sleep scores were also associated with increased odds (53% to > 200%) of developing digestive diseases.

- However, healthy sleep reduced the risk for digestive diseases regardless of genetic susceptibility.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings underscore the potential holistic impact of different sleep behaviors in mitigating the risk of digestive diseases in clinical practice,” wrote Shiyi Yu, MD, of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, and colleagues.

Poor sleep can also change our gut microbiome, Dr. Yu told this news organization. If you don’t sleep well, the repair of the gut lining cannot be finished during the night.

SOURCE:

The study was presented at the Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), 2024, annual meeting.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Yu had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Healthier sleep is associated with lower odds of developing a wide range of gastrointestinal conditions, regardless of genetic susceptibility, new research revealed.

METHODOLOGY:

- Due to the widespread prevalence of sleep issues and a growing burden of digestive diseases globally, researchers investigated the association between sleep quality and digestive disorders in a prospective cohort study of 410,586 people in the UK Biobank.

- Five individual sleep behaviors were assessed: sleep duration, insomnia, snoring, daytime sleepiness, and chronotype.

- A healthy sleep was defined as a morning chronotype, 7-8 hours of sleep duration, no self-reported snoring, never or rare insomnia, and a low frequency of daytime sleepiness, for a score of 5/5.

- The study investigators tracked the development of 16 digestive diseases over a mean period of 13.2 years.

- As well as looking at healthy sleep scores, researchers considered genetic susceptibility to gastrointestinal conditions.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 16 digestive diseases looked at, the reduction of risk was highest for irritable bowel syndrome at 50% (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.45-0.57).