User login

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

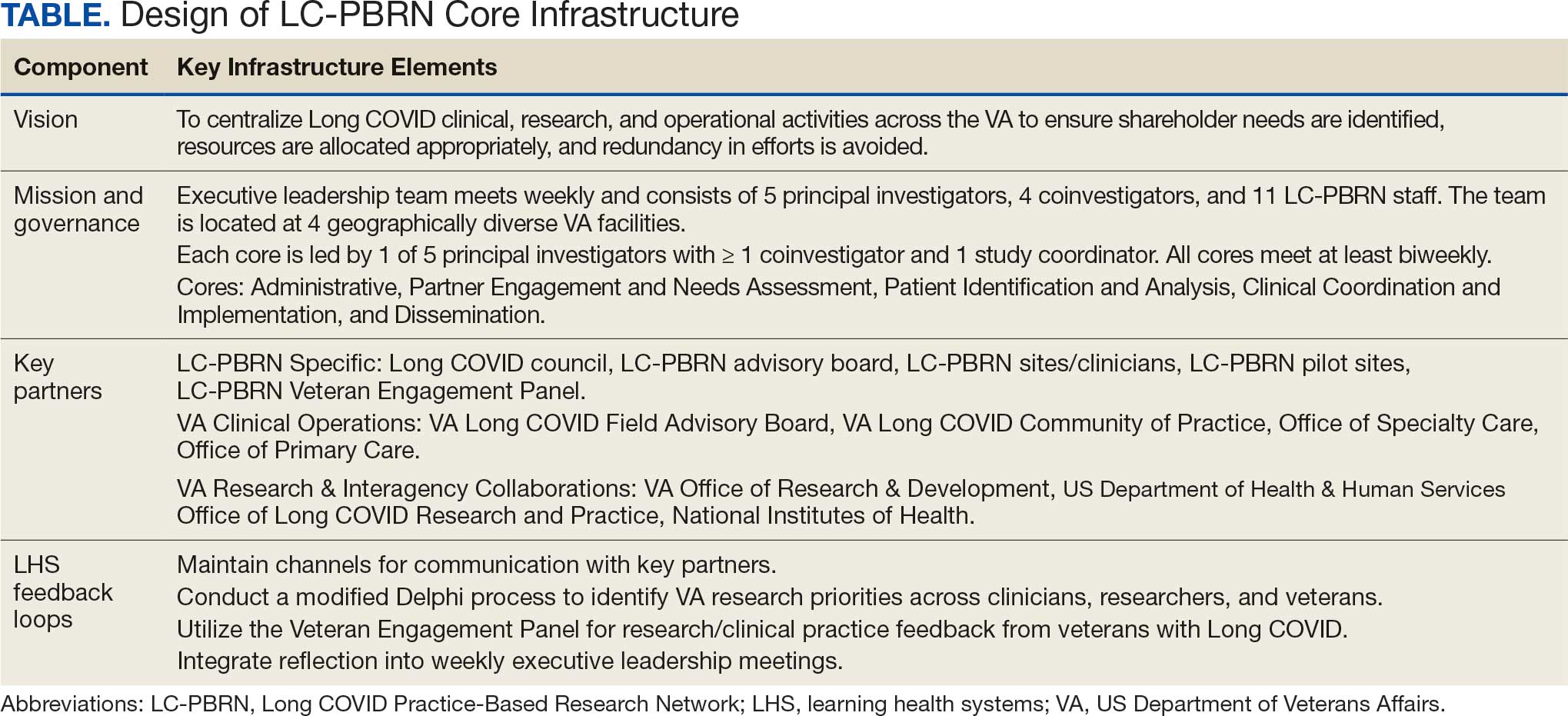

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

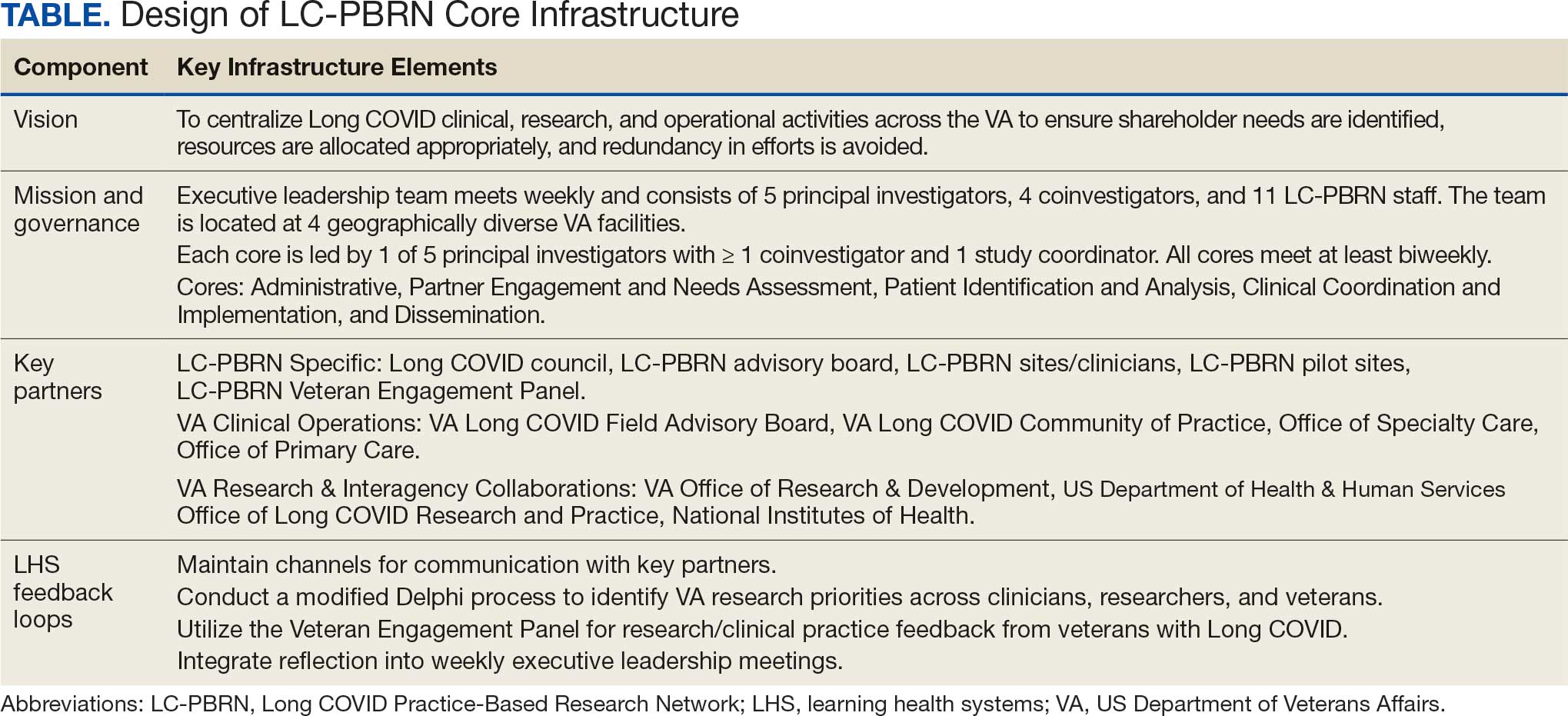

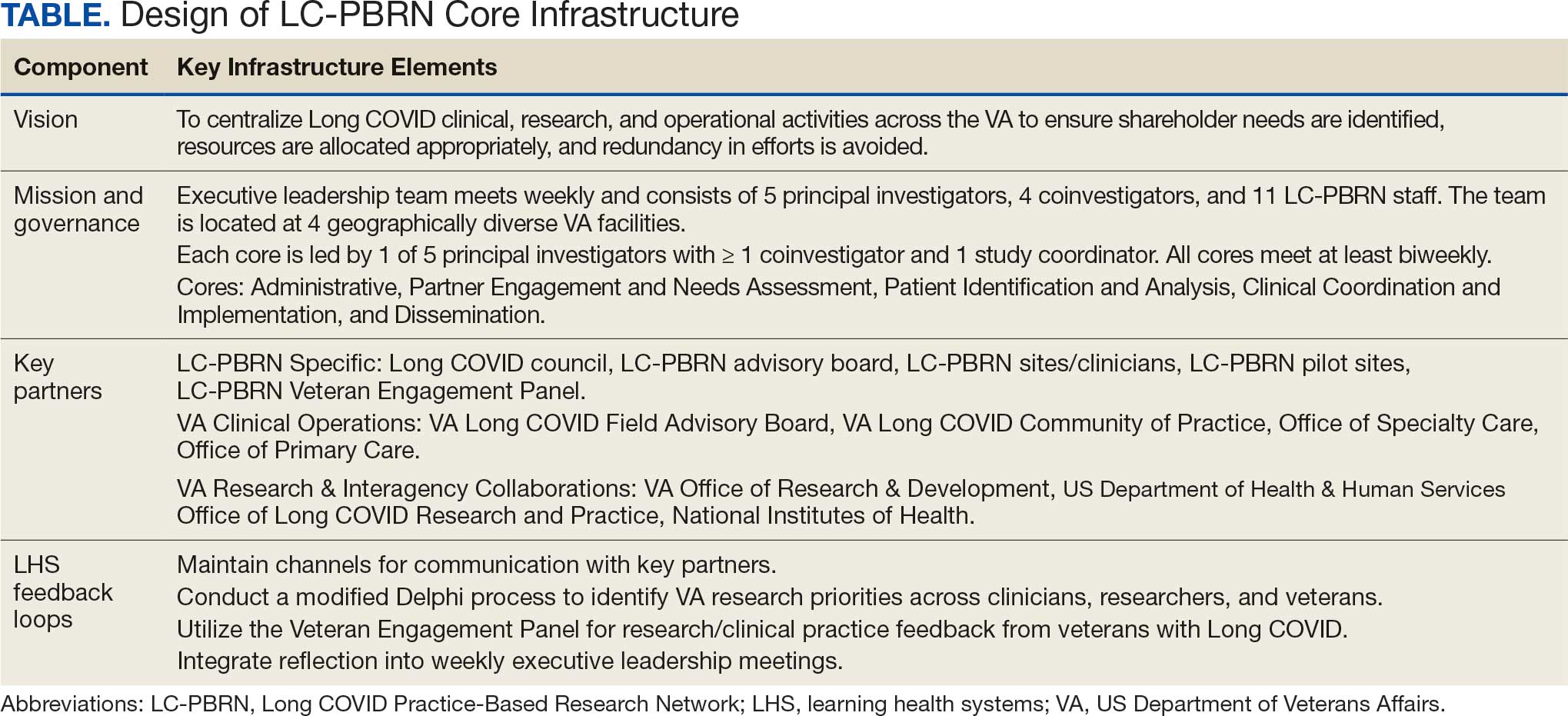

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

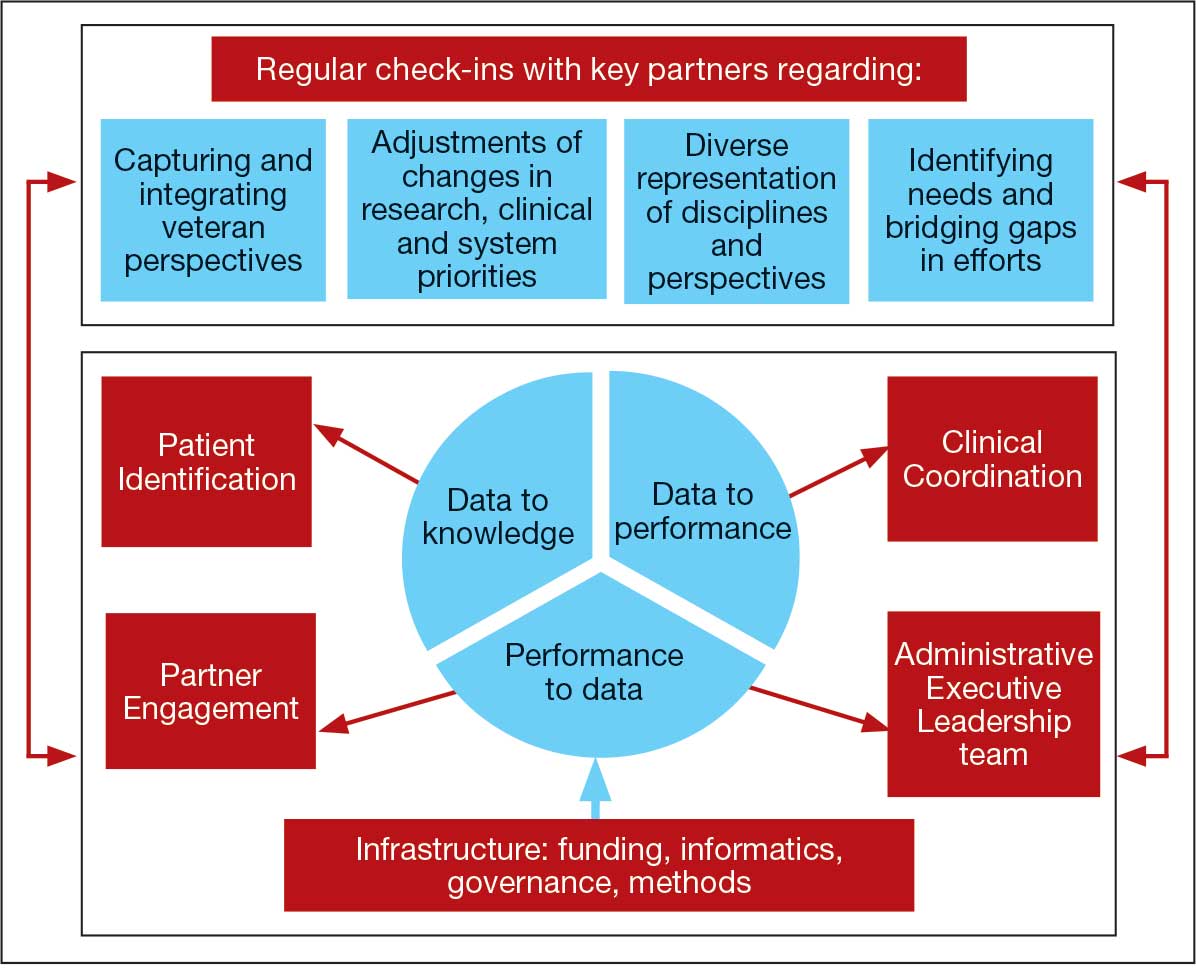

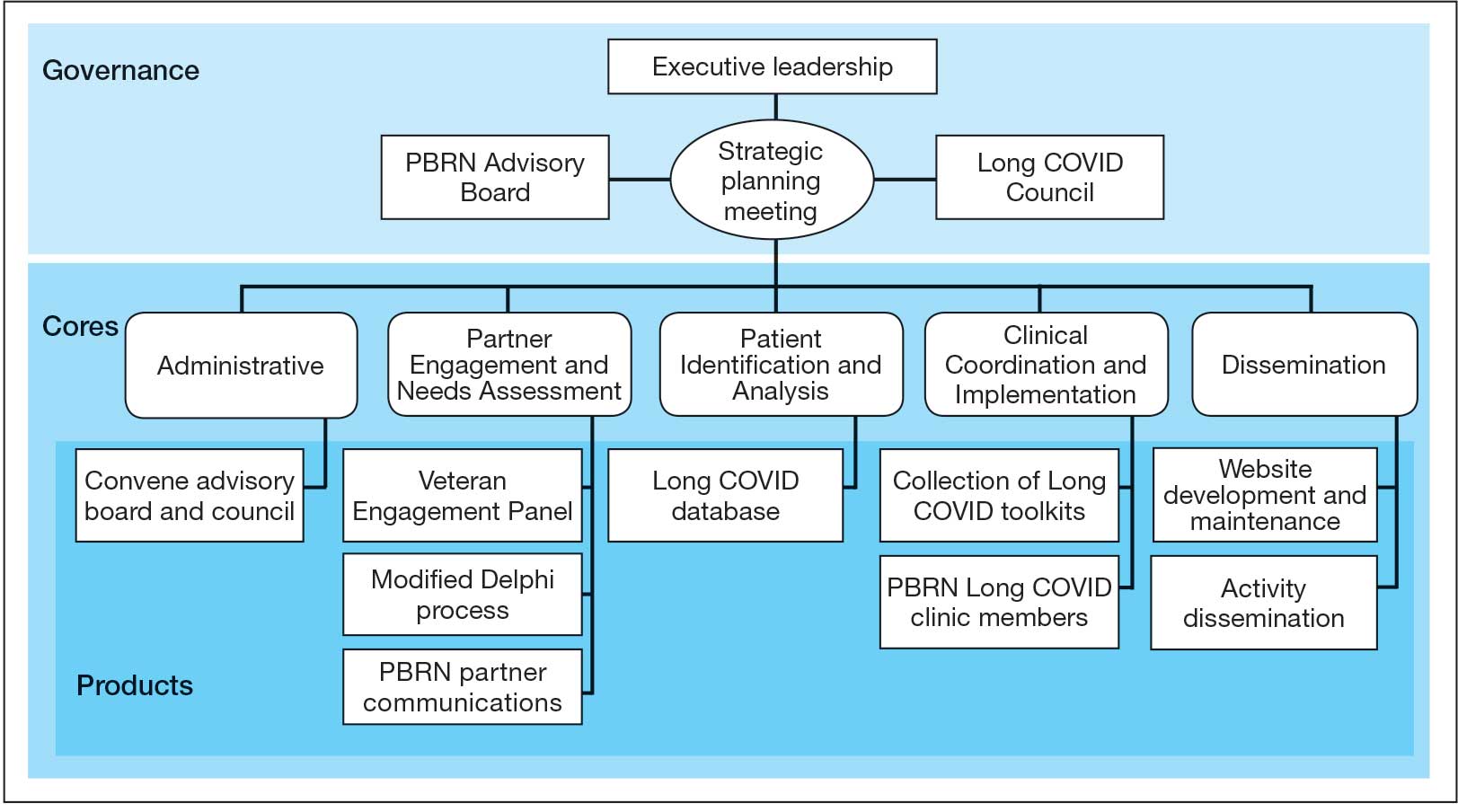

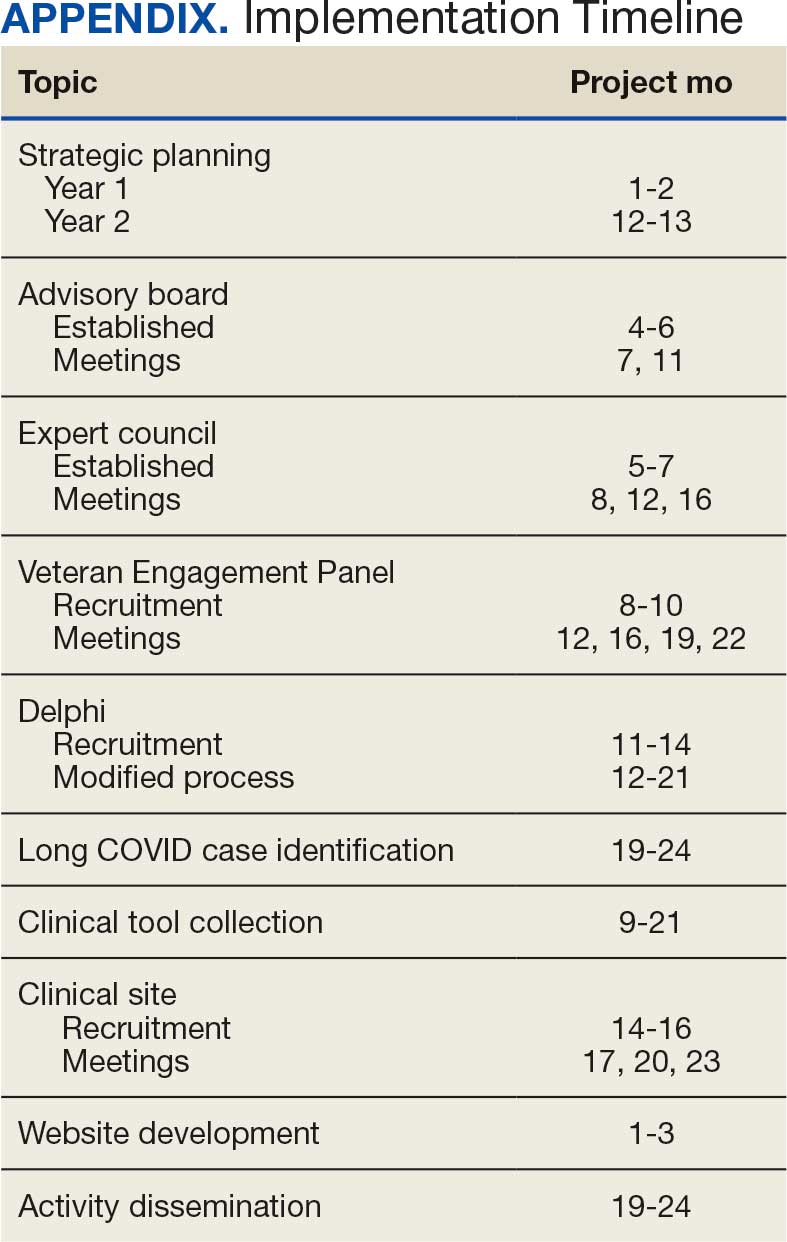

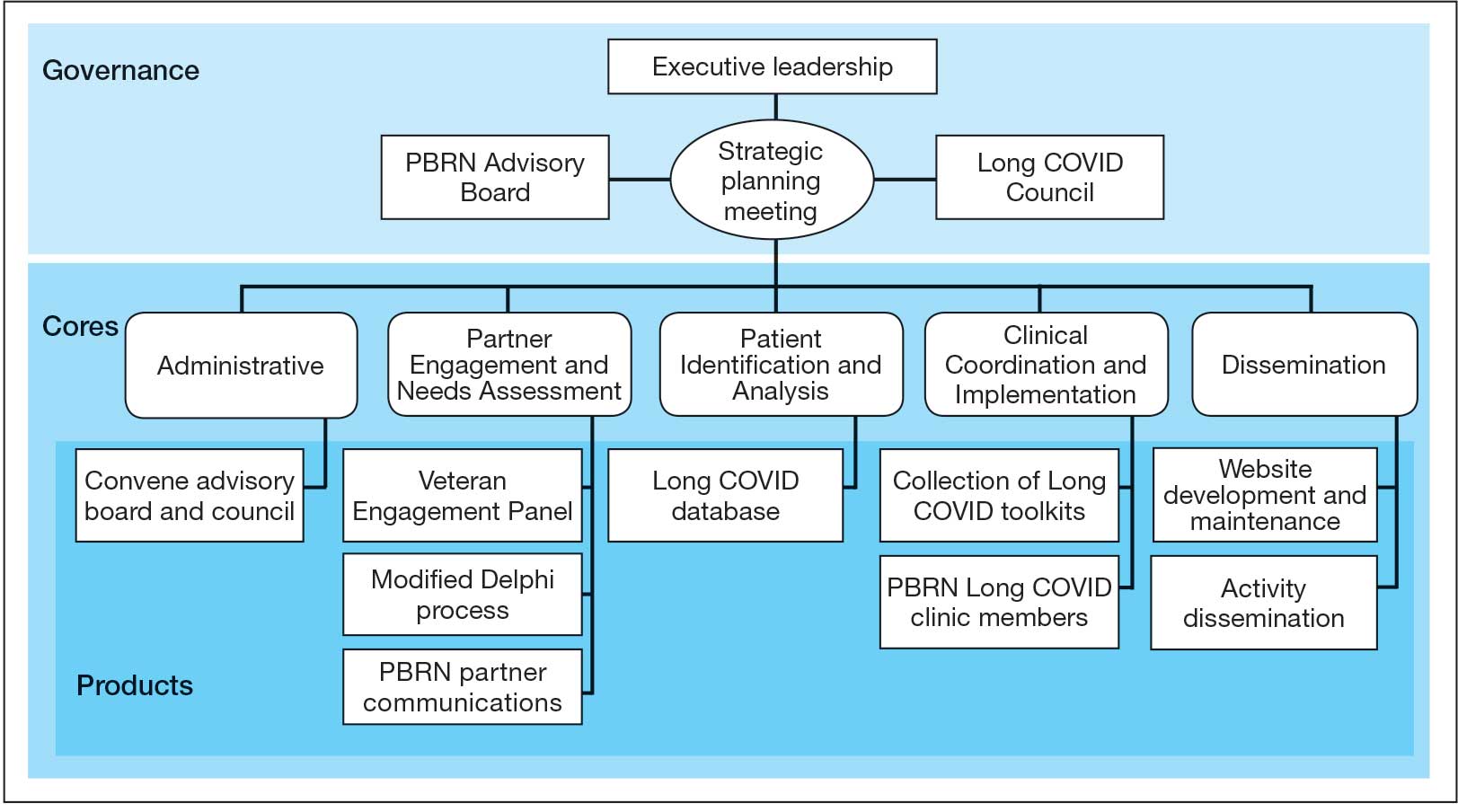

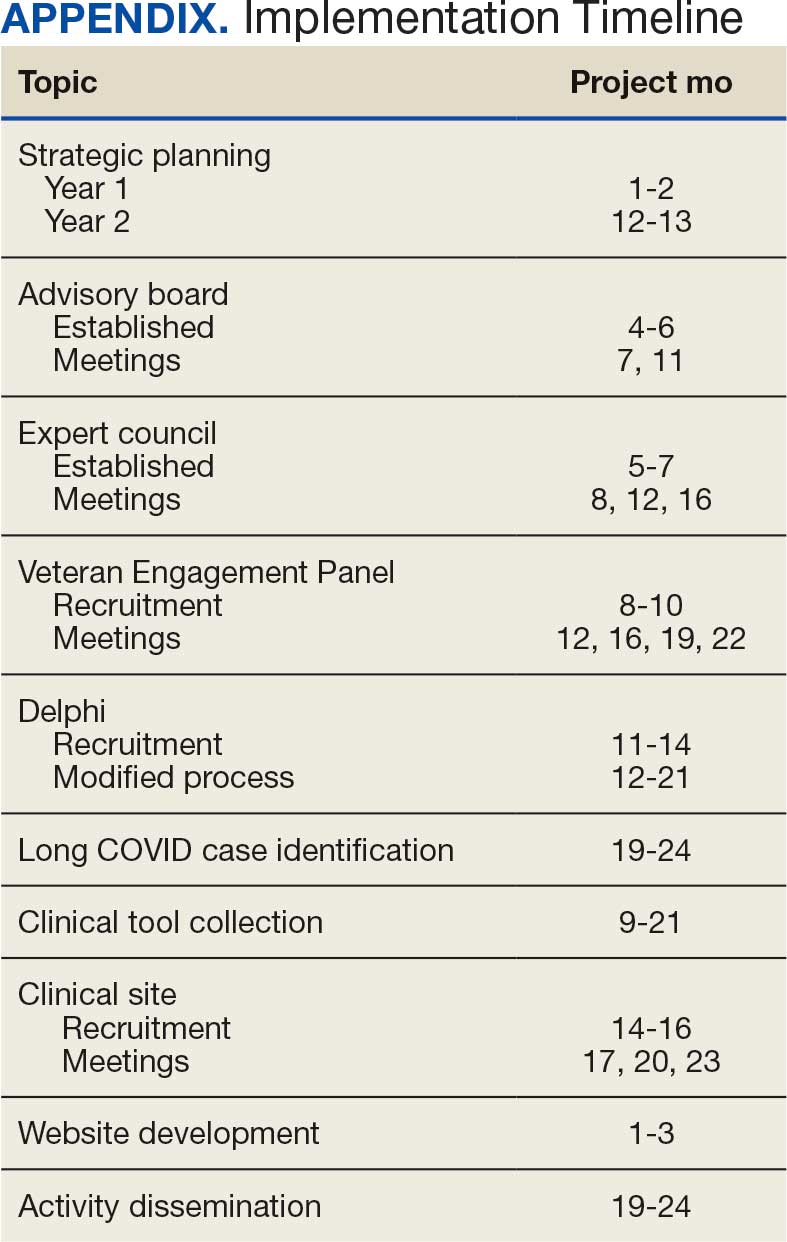

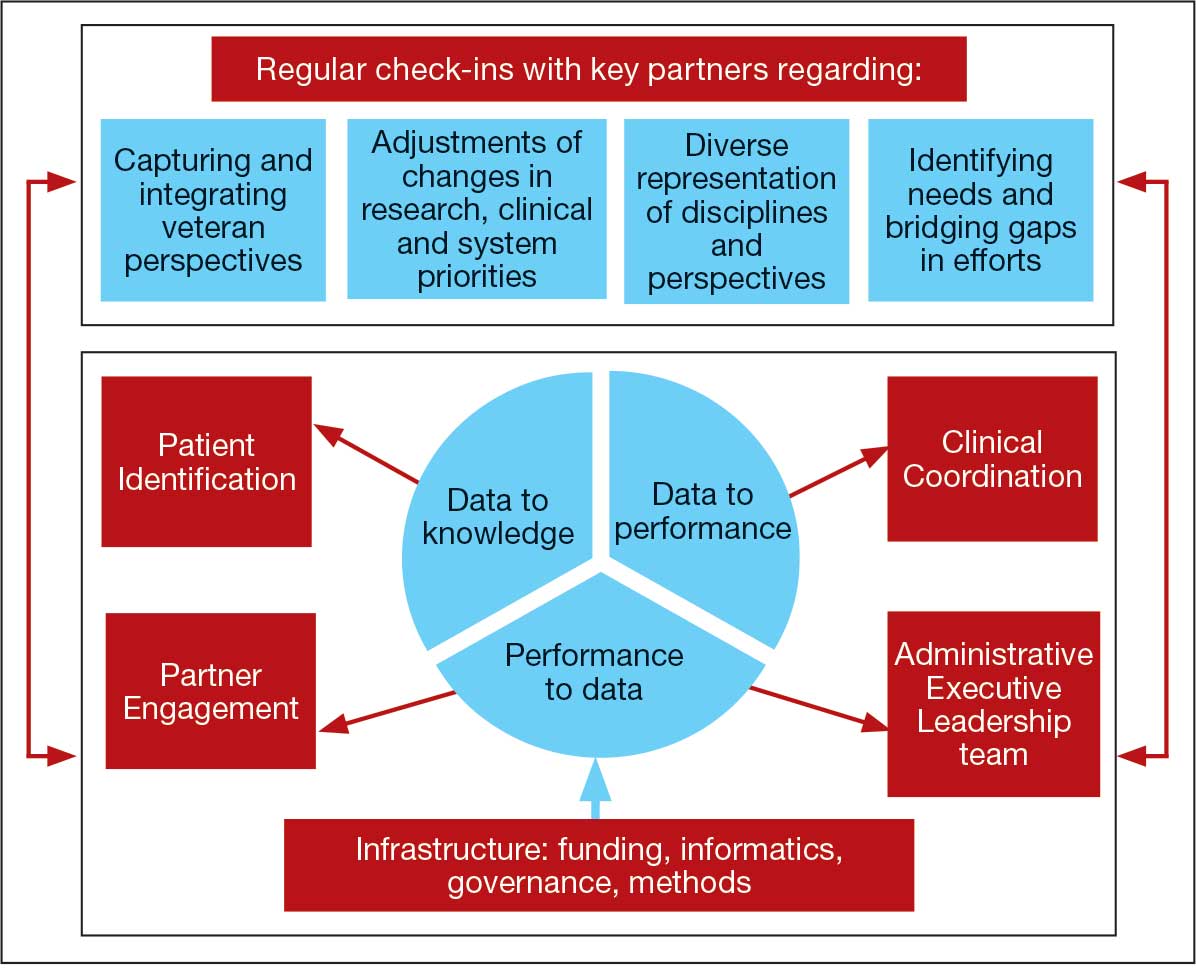

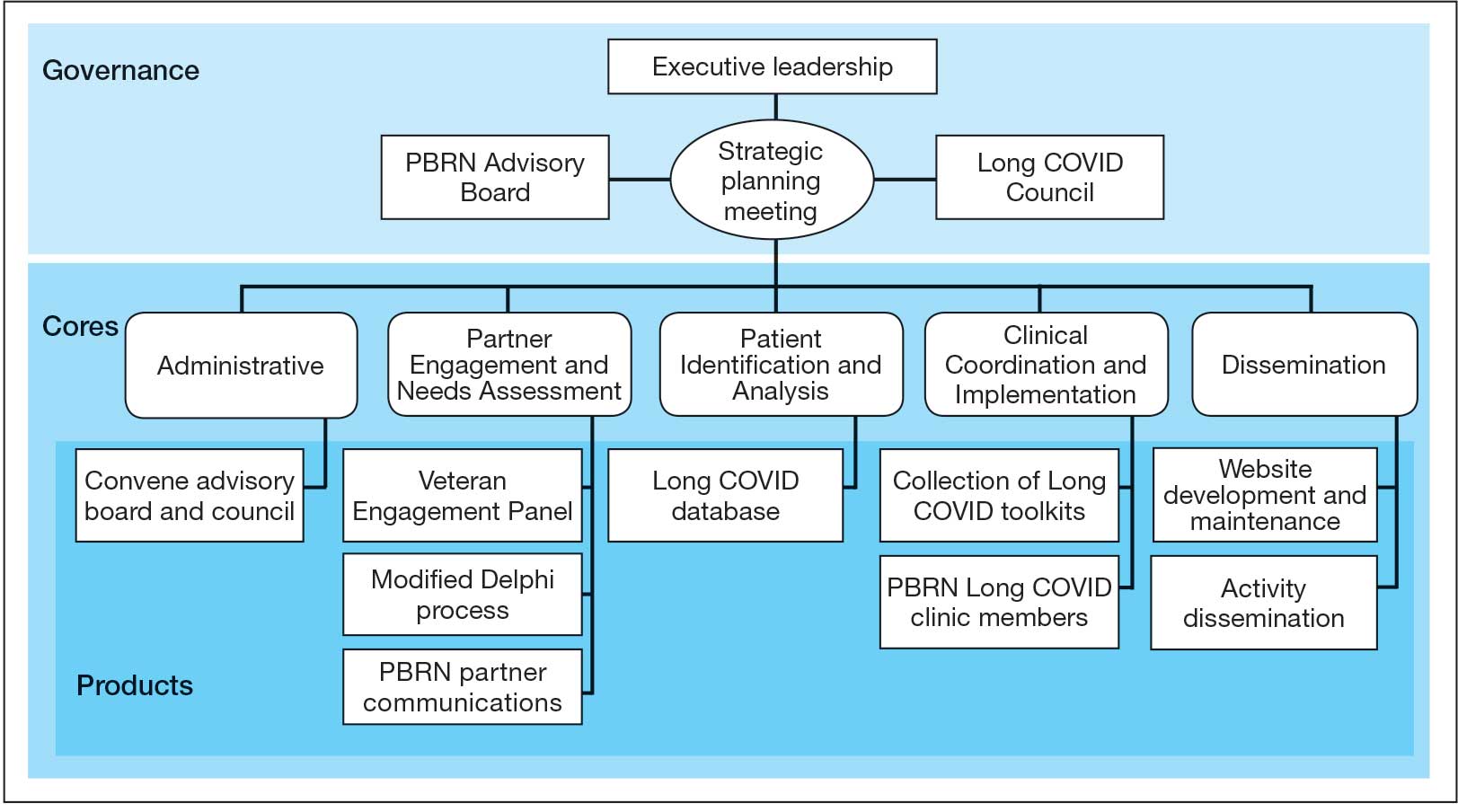

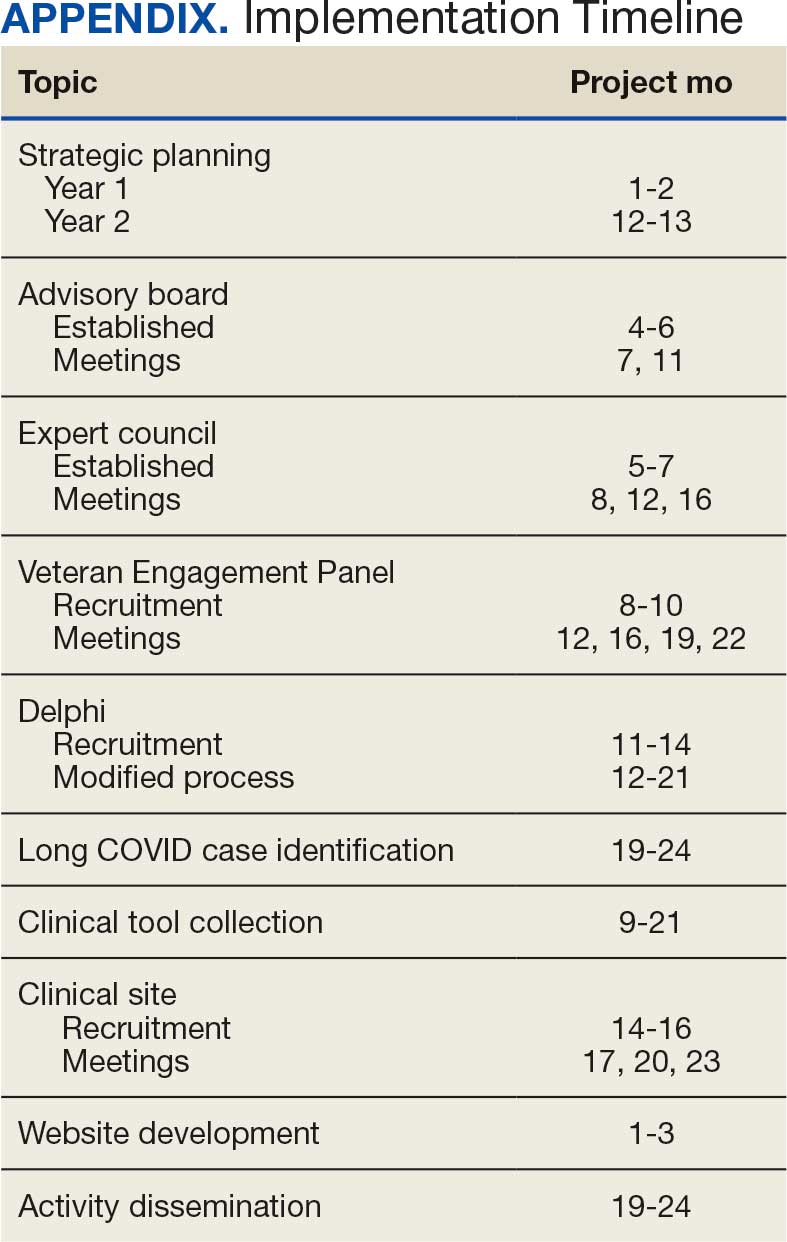

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

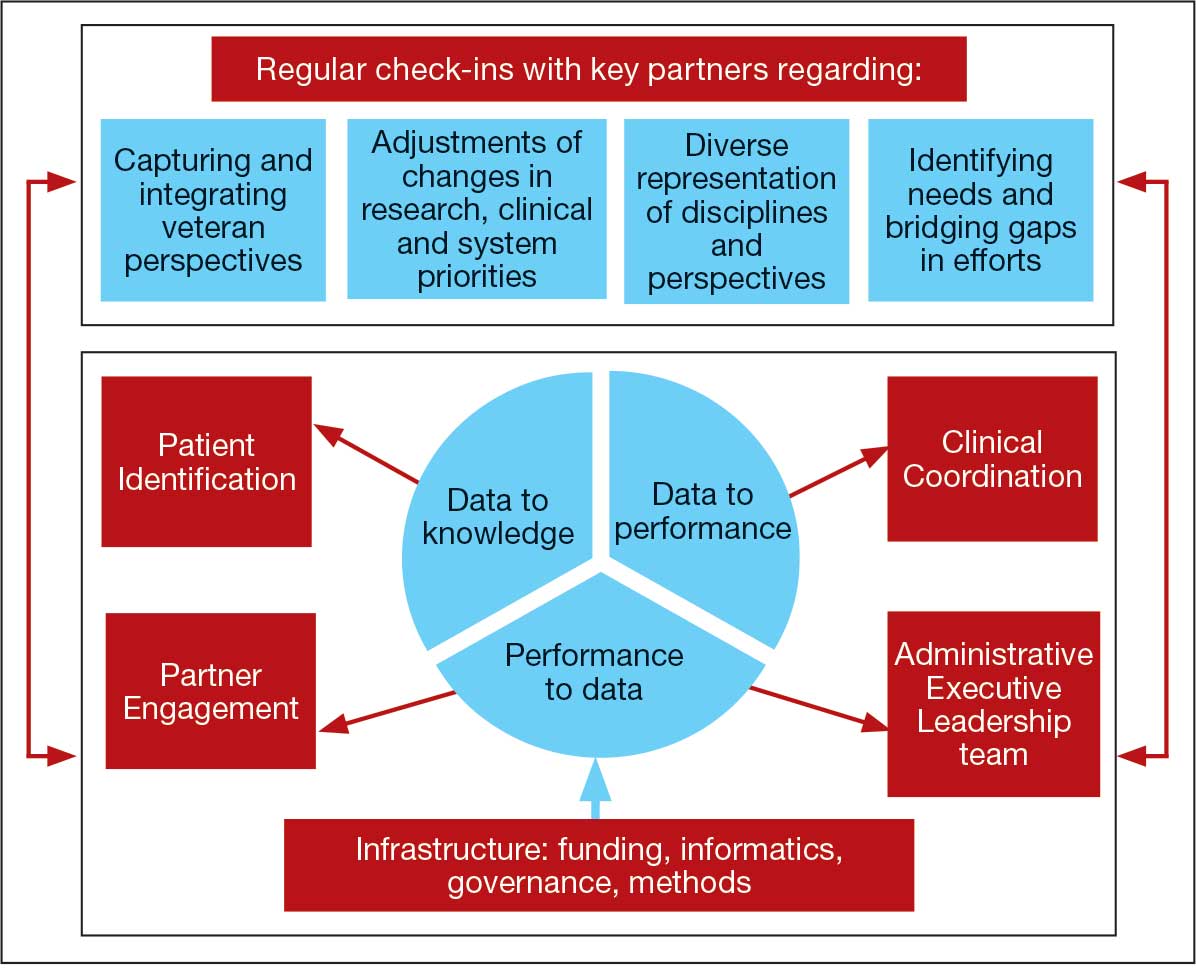

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at [email protected]) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at [email protected]) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at [email protected]) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Management of Children and Adolescents With Long COVID

Current management of children and adolescents with long COVID was the focus of various presentations at the 3rd Long COVID Congress in Berlin in November 2024. The congress aimed to facilitate in-depth discussions on recent research projects, diagnostic procedures, and therapeutic approaches to enhance care for long COVID patients. This year, the focus was on research into long COVID in children and adolescents and how to improve their care.

Uta Behrends, MD, head of the Munich Chronic Fatigue Center, Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at the Technical University of Munich, Germany, and Nicole Toepfner, MD, a pediatrician at the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, provided an initial overview.

Prevalence Data Are Limited

Data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition in children and adolescents are limited because most studies have primarily examined adults. A 2022 Swiss study estimated that it affects between 2% and 3.5% of children and adolescents who contract COVID-19. A recent study published in JAMA involving 5367 children and adolescents found that 20% of children aged 6-11 years and 14% of adolescents met the researchers’ criteria for long COVID.

Impaired Mental Health

Initial data from the latest wave of the population-based longitudinal COPSY (Corona and Psyche) study showed that compared with their peer group children and adolescents diagnosed with long COVID exhibit significantly higher rates of psychological issues and depressive symptoms. Although no significant differences were found in anxiety levels, study leader Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer, PhD, from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany, told the congress that those with long COVID do also report more frequent somatic or psychological health complaints and lower health-related quality of life than peers.

Addressing Data Gaps

Another study due to launch in January 2025 and run through to 2028 is the COVYOUTH data study, which aims to better understand the nature, frequency, and risk factors of COVID-related sequelae in children and adolescents.

Study centers include Ruhr University Bochum, University Hospital Cologne, the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, and University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Using routine data from statutory health insurance and newly developed case definitions, researchers aim to investigate:

- Psychological stress caused by COVID-19 measures

- Post-COVID syndrome and myocarditis

- Adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccinations

Specialized Diagnostics and Care

The Post-COVID Kids Bavaria project offers specialized diagnostics and care for children and adolescents, including a day clinic, telemedical follow-ups, and an inpatient pain therapy module providing age-appropriate care as close to patients’ homes as possible.

MOVE-COVID is a model project for patient-focused research on long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) involving university pediatric hospitals in Freiburg, Heidelberg, Tübingen, and Ulm. It also aims to establish a care network across the state of Baden-Württemberg, including the establishment of long COVID outpatient clinics at social pediatric centers in the network hospitals, as well as enhanced telemedical support and standardized diagnostic and treatment protocols. “MOVE-COVID has successfully consolidated competencies and capacities in patient care, health services research, and patient-focused studies across multiple centers,” Behrends said.

Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Post-COVID syndromes in children and adolescents may feature profound fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, post-exertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction, and orthostatic intolerance and overlap with conditions such as ME/CFS. According to the German patient association Fatigatio, Berlin, research and studies for these conditions in children remain limited compared with those in adults. However, the US Centers for Disease Control estimates that around 2% of ME/CFS patients are children or adolescents, with the majority being teenagers.

Two inpatient treatment concepts, SHARK and TIGER, developed by Lea Höfel, PhD, head of the Centre for Pain Therapy for Young People and the Psychological Service at the Children’s Hospital in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, address chronic pain, fatigue, and ME/CFS in young people. These programs integrate structured breaks and flexible access to multiple therapists as needed. The TIGER program focuses on those with post-exertional malaise, while the SHARK program is designed for adolescents without this symptom. Both programs last 4.5-5 weeks and emphasize symptom reduction, education, and energy management.

Preliminary Results

SHARK included 30 participants (7 men; average age, 16 years), of whom 12 had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. TIGER involved 100 participants (24 men; average age, 16.7 years), of whom 32 had a SARS-CoV-2 infection as a triggering event. Other triggers included Epstein-Barr virus and other infections.

Preliminary findings from the projects indicate that optimized management with outpatient and follow-up care can yield positive, sometimes lasting effects. No significant differences between SARS-CoV-2 and other triggers emerged, but pain proved more manageable in the SHARK group than in the TIGER group, suggesting they may involve different pathological mechanisms.

Hope for Improved Outcomes

“It’s important to move away from the idea that nothing can be done,” Behrends said. This is a common attitude with children and adolescents displaying these types of symptoms, but it’s simply not true. “Even in pediatrics, we have numerous therapeutic options that may offer relief, from medication to psychosocial interventions,” she concluded.

This story was translated from Medscape’s German edition using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Current management of children and adolescents with long COVID was the focus of various presentations at the 3rd Long COVID Congress in Berlin in November 2024. The congress aimed to facilitate in-depth discussions on recent research projects, diagnostic procedures, and therapeutic approaches to enhance care for long COVID patients. This year, the focus was on research into long COVID in children and adolescents and how to improve their care.

Uta Behrends, MD, head of the Munich Chronic Fatigue Center, Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at the Technical University of Munich, Germany, and Nicole Toepfner, MD, a pediatrician at the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, provided an initial overview.

Prevalence Data Are Limited

Data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition in children and adolescents are limited because most studies have primarily examined adults. A 2022 Swiss study estimated that it affects between 2% and 3.5% of children and adolescents who contract COVID-19. A recent study published in JAMA involving 5367 children and adolescents found that 20% of children aged 6-11 years and 14% of adolescents met the researchers’ criteria for long COVID.

Impaired Mental Health

Initial data from the latest wave of the population-based longitudinal COPSY (Corona and Psyche) study showed that compared with their peer group children and adolescents diagnosed with long COVID exhibit significantly higher rates of psychological issues and depressive symptoms. Although no significant differences were found in anxiety levels, study leader Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer, PhD, from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany, told the congress that those with long COVID do also report more frequent somatic or psychological health complaints and lower health-related quality of life than peers.

Addressing Data Gaps

Another study due to launch in January 2025 and run through to 2028 is the COVYOUTH data study, which aims to better understand the nature, frequency, and risk factors of COVID-related sequelae in children and adolescents.

Study centers include Ruhr University Bochum, University Hospital Cologne, the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, and University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Using routine data from statutory health insurance and newly developed case definitions, researchers aim to investigate:

- Psychological stress caused by COVID-19 measures

- Post-COVID syndrome and myocarditis

- Adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccinations

Specialized Diagnostics and Care

The Post-COVID Kids Bavaria project offers specialized diagnostics and care for children and adolescents, including a day clinic, telemedical follow-ups, and an inpatient pain therapy module providing age-appropriate care as close to patients’ homes as possible.

MOVE-COVID is a model project for patient-focused research on long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) involving university pediatric hospitals in Freiburg, Heidelberg, Tübingen, and Ulm. It also aims to establish a care network across the state of Baden-Württemberg, including the establishment of long COVID outpatient clinics at social pediatric centers in the network hospitals, as well as enhanced telemedical support and standardized diagnostic and treatment protocols. “MOVE-COVID has successfully consolidated competencies and capacities in patient care, health services research, and patient-focused studies across multiple centers,” Behrends said.

Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Post-COVID syndromes in children and adolescents may feature profound fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, post-exertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction, and orthostatic intolerance and overlap with conditions such as ME/CFS. According to the German patient association Fatigatio, Berlin, research and studies for these conditions in children remain limited compared with those in adults. However, the US Centers for Disease Control estimates that around 2% of ME/CFS patients are children or adolescents, with the majority being teenagers.

Two inpatient treatment concepts, SHARK and TIGER, developed by Lea Höfel, PhD, head of the Centre for Pain Therapy for Young People and the Psychological Service at the Children’s Hospital in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, address chronic pain, fatigue, and ME/CFS in young people. These programs integrate structured breaks and flexible access to multiple therapists as needed. The TIGER program focuses on those with post-exertional malaise, while the SHARK program is designed for adolescents without this symptom. Both programs last 4.5-5 weeks and emphasize symptom reduction, education, and energy management.

Preliminary Results

SHARK included 30 participants (7 men; average age, 16 years), of whom 12 had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. TIGER involved 100 participants (24 men; average age, 16.7 years), of whom 32 had a SARS-CoV-2 infection as a triggering event. Other triggers included Epstein-Barr virus and other infections.

Preliminary findings from the projects indicate that optimized management with outpatient and follow-up care can yield positive, sometimes lasting effects. No significant differences between SARS-CoV-2 and other triggers emerged, but pain proved more manageable in the SHARK group than in the TIGER group, suggesting they may involve different pathological mechanisms.

Hope for Improved Outcomes

“It’s important to move away from the idea that nothing can be done,” Behrends said. This is a common attitude with children and adolescents displaying these types of symptoms, but it’s simply not true. “Even in pediatrics, we have numerous therapeutic options that may offer relief, from medication to psychosocial interventions,” she concluded.

This story was translated from Medscape’s German edition using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Current management of children and adolescents with long COVID was the focus of various presentations at the 3rd Long COVID Congress in Berlin in November 2024. The congress aimed to facilitate in-depth discussions on recent research projects, diagnostic procedures, and therapeutic approaches to enhance care for long COVID patients. This year, the focus was on research into long COVID in children and adolescents and how to improve their care.

Uta Behrends, MD, head of the Munich Chronic Fatigue Center, Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at the Technical University of Munich, Germany, and Nicole Toepfner, MD, a pediatrician at the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, provided an initial overview.

Prevalence Data Are Limited

Data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition in children and adolescents are limited because most studies have primarily examined adults. A 2022 Swiss study estimated that it affects between 2% and 3.5% of children and adolescents who contract COVID-19. A recent study published in JAMA involving 5367 children and adolescents found that 20% of children aged 6-11 years and 14% of adolescents met the researchers’ criteria for long COVID.

Impaired Mental Health

Initial data from the latest wave of the population-based longitudinal COPSY (Corona and Psyche) study showed that compared with their peer group children and adolescents diagnosed with long COVID exhibit significantly higher rates of psychological issues and depressive symptoms. Although no significant differences were found in anxiety levels, study leader Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer, PhD, from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany, told the congress that those with long COVID do also report more frequent somatic or psychological health complaints and lower health-related quality of life than peers.

Addressing Data Gaps

Another study due to launch in January 2025 and run through to 2028 is the COVYOUTH data study, which aims to better understand the nature, frequency, and risk factors of COVID-related sequelae in children and adolescents.

Study centers include Ruhr University Bochum, University Hospital Cologne, the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, and University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Using routine data from statutory health insurance and newly developed case definitions, researchers aim to investigate:

- Psychological stress caused by COVID-19 measures

- Post-COVID syndrome and myocarditis

- Adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccinations

Specialized Diagnostics and Care

The Post-COVID Kids Bavaria project offers specialized diagnostics and care for children and adolescents, including a day clinic, telemedical follow-ups, and an inpatient pain therapy module providing age-appropriate care as close to patients’ homes as possible.

MOVE-COVID is a model project for patient-focused research on long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) involving university pediatric hospitals in Freiburg, Heidelberg, Tübingen, and Ulm. It also aims to establish a care network across the state of Baden-Württemberg, including the establishment of long COVID outpatient clinics at social pediatric centers in the network hospitals, as well as enhanced telemedical support and standardized diagnostic and treatment protocols. “MOVE-COVID has successfully consolidated competencies and capacities in patient care, health services research, and patient-focused studies across multiple centers,” Behrends said.

Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Post-COVID syndromes in children and adolescents may feature profound fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, post-exertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction, and orthostatic intolerance and overlap with conditions such as ME/CFS. According to the German patient association Fatigatio, Berlin, research and studies for these conditions in children remain limited compared with those in adults. However, the US Centers for Disease Control estimates that around 2% of ME/CFS patients are children or adolescents, with the majority being teenagers.