User login

Americans concerned about cost of cancer care

A recent survey suggests Americans are nearly as worried about the cost of a cancer diagnosis as they are about dying from cancer.

The cost of cancer care was a top concern even among people who had no prior experience with cancer.

At the same time, cancer patients/survivors admitted to delaying or forgoing care due to costs, and caregivers reported taking “dramatic” actions to pay for their loved one’s care.

These are findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)’s second annual National Cancer Opinion Survey.

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll from July 10, 2018, to August 10, 2018. It included 4,887 U.S. adults age 18 and older—1,001 of whom have or had cancer.

Cost among top concerns

Death and pain/suffering were the top concerns related to a cancer diagnosis. Fifty-four percent of respondents said death would be one of their greatest concerns if they were diagnosed with cancer, and the same percentage rated pain/suffering a top concern.

Forty-four percent of respondents said paying for cancer treatment would be a top concern, and 45% said the same about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their family. When combined, financial issues were a top concern for 57% of respondents.

Paying for treatment was a top concern for:

- 36% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 51% of caregivers

- 43% of people with no prior cancer experience.

The financial impact on family was a top concern for:

- 39% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 55% of caregivers

- 42% of people with no prior cancer experience.

Cutting costs

Sixty-one percent of caregivers surveyed said they or another relative have taken a “dramatic” step to help pay for their loved one’s care, including:

- Dipping into savings accounts (35%)

- Working extra hours (23%)

- Taking an early withdrawal from a retirement account or college fund (14%)

- Postponing retirement (14%)

- Taking out a second mortgage or other type of loan (13%)

- Taking an additional job (13%)

- Selling family heirlooms (9%).

Twenty percent of cancer patients/survivors said they have taken actions to reduce treatment costs, including:

- Delaying scans (7%)

- Skipping or delaying appointments (7%)

- Skipping doses of prescribed treatment (6%)

- Postponing or not filling prescriptions (5%)

- Refusing treatment (3%).

“Patients are right to be concerned about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their families,” said Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO’s chief medical officer.

“It’s clear that high treatment costs are taking a serious toll not only on patients, but also on the people who care for them. If a family member has been diagnosed with cancer, the sole focus should be helping them get well. Instead, Americans are worrying about affording treatment, and, in many cases, they’re making serious personal sacrifices to help pay for their loved ones’ care.”

A recent survey suggests Americans are nearly as worried about the cost of a cancer diagnosis as they are about dying from cancer.

The cost of cancer care was a top concern even among people who had no prior experience with cancer.

At the same time, cancer patients/survivors admitted to delaying or forgoing care due to costs, and caregivers reported taking “dramatic” actions to pay for their loved one’s care.

These are findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)’s second annual National Cancer Opinion Survey.

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll from July 10, 2018, to August 10, 2018. It included 4,887 U.S. adults age 18 and older—1,001 of whom have or had cancer.

Cost among top concerns

Death and pain/suffering were the top concerns related to a cancer diagnosis. Fifty-four percent of respondents said death would be one of their greatest concerns if they were diagnosed with cancer, and the same percentage rated pain/suffering a top concern.

Forty-four percent of respondents said paying for cancer treatment would be a top concern, and 45% said the same about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their family. When combined, financial issues were a top concern for 57% of respondents.

Paying for treatment was a top concern for:

- 36% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 51% of caregivers

- 43% of people with no prior cancer experience.

The financial impact on family was a top concern for:

- 39% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 55% of caregivers

- 42% of people with no prior cancer experience.

Cutting costs

Sixty-one percent of caregivers surveyed said they or another relative have taken a “dramatic” step to help pay for their loved one’s care, including:

- Dipping into savings accounts (35%)

- Working extra hours (23%)

- Taking an early withdrawal from a retirement account or college fund (14%)

- Postponing retirement (14%)

- Taking out a second mortgage or other type of loan (13%)

- Taking an additional job (13%)

- Selling family heirlooms (9%).

Twenty percent of cancer patients/survivors said they have taken actions to reduce treatment costs, including:

- Delaying scans (7%)

- Skipping or delaying appointments (7%)

- Skipping doses of prescribed treatment (6%)

- Postponing or not filling prescriptions (5%)

- Refusing treatment (3%).

“Patients are right to be concerned about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their families,” said Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO’s chief medical officer.

“It’s clear that high treatment costs are taking a serious toll not only on patients, but also on the people who care for them. If a family member has been diagnosed with cancer, the sole focus should be helping them get well. Instead, Americans are worrying about affording treatment, and, in many cases, they’re making serious personal sacrifices to help pay for their loved ones’ care.”

A recent survey suggests Americans are nearly as worried about the cost of a cancer diagnosis as they are about dying from cancer.

The cost of cancer care was a top concern even among people who had no prior experience with cancer.

At the same time, cancer patients/survivors admitted to delaying or forgoing care due to costs, and caregivers reported taking “dramatic” actions to pay for their loved one’s care.

These are findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)’s second annual National Cancer Opinion Survey.

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll from July 10, 2018, to August 10, 2018. It included 4,887 U.S. adults age 18 and older—1,001 of whom have or had cancer.

Cost among top concerns

Death and pain/suffering were the top concerns related to a cancer diagnosis. Fifty-four percent of respondents said death would be one of their greatest concerns if they were diagnosed with cancer, and the same percentage rated pain/suffering a top concern.

Forty-four percent of respondents said paying for cancer treatment would be a top concern, and 45% said the same about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their family. When combined, financial issues were a top concern for 57% of respondents.

Paying for treatment was a top concern for:

- 36% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 51% of caregivers

- 43% of people with no prior cancer experience.

The financial impact on family was a top concern for:

- 39% of respondents who had/have cancer

- 55% of caregivers

- 42% of people with no prior cancer experience.

Cutting costs

Sixty-one percent of caregivers surveyed said they or another relative have taken a “dramatic” step to help pay for their loved one’s care, including:

- Dipping into savings accounts (35%)

- Working extra hours (23%)

- Taking an early withdrawal from a retirement account or college fund (14%)

- Postponing retirement (14%)

- Taking out a second mortgage or other type of loan (13%)

- Taking an additional job (13%)

- Selling family heirlooms (9%).

Twenty percent of cancer patients/survivors said they have taken actions to reduce treatment costs, including:

- Delaying scans (7%)

- Skipping or delaying appointments (7%)

- Skipping doses of prescribed treatment (6%)

- Postponing or not filling prescriptions (5%)

- Refusing treatment (3%).

“Patients are right to be concerned about the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis on their families,” said Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO’s chief medical officer.

“It’s clear that high treatment costs are taking a serious toll not only on patients, but also on the people who care for them. If a family member has been diagnosed with cancer, the sole focus should be helping them get well. Instead, Americans are worrying about affording treatment, and, in many cases, they’re making serious personal sacrifices to help pay for their loved ones’ care.”

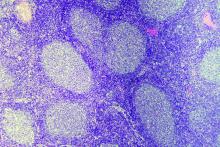

Rituximab biosimilar looks equivalent in follicular lymphoma

The rituximab biosimilar CT-P10 has equivalent efficacy, compared with rituximab, and is well tolerated in the treatment of low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma, according to results from a multinational, randomized, phase 3 study.

Overall response after 7 months of treatment exceeded 80% for patients assigned to CT-P10 and for those assigned to rituximab, investigators reported in the Lancet Haematology.

Adverse event profiles were comparable for rituximab and the biosimilar over that time period, while pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity were likewise comparable between arms, according to investigators.

“Thus, CT-P10 monotherapy is suggested as a new therapeutic option for patients with low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma,” wrote senior author Larry W Kwak, MD, PhD, of the Comprehensive Cancer Center, City of Hope, Duarte, Calif., and his colleagues.

CT-P10, the first rituximab biosimilar to be authorized by the European Medicines Agency, has been recommended for approval in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee.

If approved by the FDA, CT-P10 would be the first rituximab biosimilar available in the United States, according to the company, which noted three proposed indications in non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In the current randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trial, 258 patients with stage II-IV low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma were randomly assigned to CT-P10 (130 patients) or rituximab sourced in the United States (128 patients).

Treatment consisted of an induction period of intravenous CT-P10 or rituximab weekly for 4 weeks, while patients experiencing disease control went on to a maintenance phase with their assigned treatment given every 8 weeks for six cycles, followed by another year of maintenance therapy with CT-P10 for those still on study.

The primary endpoint of the study was overall response at 7 months, defined as a complete response, unconfirmed complete response, or partial response.

Overall response was seen in 83% of patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% of patients randomized to rituximab at 7 months, Dr. Kwak and his colleagues reported.

The two treatments were deemed therapeutically equivalent, as illustrated by 90% confidence intervals within a prespecified equivalence margin of 17%, investigators said.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events in either group were infusion-related reactions, which were of grade 1-2, except for one grade 3 reaction reported in the CT-P10 group, according to the report. Other common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infections and fatigue.

Serious adverse events were reported in six patients in the CT-P10 arm and three patients in the rituximab arm.

The availability of a rituximab biosimilar is anticipated to reduce the cost of treatment and improve patient access, according to investigators.

Introduction of CT-P10 in the European Union was projected to save between 90 and 150 million euros over a year, enabling more than 12,500 new patients to be treated with the biosimilar, according to results of a budget impact analysis investigators cited in their report.

“Widespread adoption of a rituximab biosimilar could have a substantial effect on health care budgets and might also have effects at a societal level,” Dr. Kwak and his coauthors said in the report.

The trial was sponsored by Celltrion and three coauthors of the study were employees of the company. Dr. Kwak and several other coinvestigators not employed by Celltrion reported disclosures related to the company. Other disclosures provided related to Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other entities.

SOURCE: Ogura M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e543-53.

The rituximab biosimilar CT-P10 has equivalent efficacy, compared with rituximab, and is well tolerated in the treatment of low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma, according to results from a multinational, randomized, phase 3 study.

Overall response after 7 months of treatment exceeded 80% for patients assigned to CT-P10 and for those assigned to rituximab, investigators reported in the Lancet Haematology.

Adverse event profiles were comparable for rituximab and the biosimilar over that time period, while pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity were likewise comparable between arms, according to investigators.

“Thus, CT-P10 monotherapy is suggested as a new therapeutic option for patients with low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma,” wrote senior author Larry W Kwak, MD, PhD, of the Comprehensive Cancer Center, City of Hope, Duarte, Calif., and his colleagues.

CT-P10, the first rituximab biosimilar to be authorized by the European Medicines Agency, has been recommended for approval in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee.

If approved by the FDA, CT-P10 would be the first rituximab biosimilar available in the United States, according to the company, which noted three proposed indications in non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In the current randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trial, 258 patients with stage II-IV low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma were randomly assigned to CT-P10 (130 patients) or rituximab sourced in the United States (128 patients).

Treatment consisted of an induction period of intravenous CT-P10 or rituximab weekly for 4 weeks, while patients experiencing disease control went on to a maintenance phase with their assigned treatment given every 8 weeks for six cycles, followed by another year of maintenance therapy with CT-P10 for those still on study.

The primary endpoint of the study was overall response at 7 months, defined as a complete response, unconfirmed complete response, or partial response.

Overall response was seen in 83% of patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% of patients randomized to rituximab at 7 months, Dr. Kwak and his colleagues reported.

The two treatments were deemed therapeutically equivalent, as illustrated by 90% confidence intervals within a prespecified equivalence margin of 17%, investigators said.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events in either group were infusion-related reactions, which were of grade 1-2, except for one grade 3 reaction reported in the CT-P10 group, according to the report. Other common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infections and fatigue.

Serious adverse events were reported in six patients in the CT-P10 arm and three patients in the rituximab arm.

The availability of a rituximab biosimilar is anticipated to reduce the cost of treatment and improve patient access, according to investigators.

Introduction of CT-P10 in the European Union was projected to save between 90 and 150 million euros over a year, enabling more than 12,500 new patients to be treated with the biosimilar, according to results of a budget impact analysis investigators cited in their report.

“Widespread adoption of a rituximab biosimilar could have a substantial effect on health care budgets and might also have effects at a societal level,” Dr. Kwak and his coauthors said in the report.

The trial was sponsored by Celltrion and three coauthors of the study were employees of the company. Dr. Kwak and several other coinvestigators not employed by Celltrion reported disclosures related to the company. Other disclosures provided related to Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other entities.

SOURCE: Ogura M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e543-53.

The rituximab biosimilar CT-P10 has equivalent efficacy, compared with rituximab, and is well tolerated in the treatment of low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma, according to results from a multinational, randomized, phase 3 study.

Overall response after 7 months of treatment exceeded 80% for patients assigned to CT-P10 and for those assigned to rituximab, investigators reported in the Lancet Haematology.

Adverse event profiles were comparable for rituximab and the biosimilar over that time period, while pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity were likewise comparable between arms, according to investigators.

“Thus, CT-P10 monotherapy is suggested as a new therapeutic option for patients with low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma,” wrote senior author Larry W Kwak, MD, PhD, of the Comprehensive Cancer Center, City of Hope, Duarte, Calif., and his colleagues.

CT-P10, the first rituximab biosimilar to be authorized by the European Medicines Agency, has been recommended for approval in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee.

If approved by the FDA, CT-P10 would be the first rituximab biosimilar available in the United States, according to the company, which noted three proposed indications in non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In the current randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trial, 258 patients with stage II-IV low–tumor-burden follicular lymphoma were randomly assigned to CT-P10 (130 patients) or rituximab sourced in the United States (128 patients).

Treatment consisted of an induction period of intravenous CT-P10 or rituximab weekly for 4 weeks, while patients experiencing disease control went on to a maintenance phase with their assigned treatment given every 8 weeks for six cycles, followed by another year of maintenance therapy with CT-P10 for those still on study.

The primary endpoint of the study was overall response at 7 months, defined as a complete response, unconfirmed complete response, or partial response.

Overall response was seen in 83% of patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% of patients randomized to rituximab at 7 months, Dr. Kwak and his colleagues reported.

The two treatments were deemed therapeutically equivalent, as illustrated by 90% confidence intervals within a prespecified equivalence margin of 17%, investigators said.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events in either group were infusion-related reactions, which were of grade 1-2, except for one grade 3 reaction reported in the CT-P10 group, according to the report. Other common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infections and fatigue.

Serious adverse events were reported in six patients in the CT-P10 arm and three patients in the rituximab arm.

The availability of a rituximab biosimilar is anticipated to reduce the cost of treatment and improve patient access, according to investigators.

Introduction of CT-P10 in the European Union was projected to save between 90 and 150 million euros over a year, enabling more than 12,500 new patients to be treated with the biosimilar, according to results of a budget impact analysis investigators cited in their report.

“Widespread adoption of a rituximab biosimilar could have a substantial effect on health care budgets and might also have effects at a societal level,” Dr. Kwak and his coauthors said in the report.

The trial was sponsored by Celltrion and three coauthors of the study were employees of the company. Dr. Kwak and several other coinvestigators not employed by Celltrion reported disclosures related to the company. Other disclosures provided related to Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other entities.

SOURCE: Ogura M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e543-53.

FROM LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall response after 7 months of treatment was seen in 83% of patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% of patients randomized to rituximab.

Study details: Analysis of 258 patients randomized to CT-P10 or rituximab in a phase 3, double-blind, parallel-group trial.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored by Celltrion and three coauthors of the study were employees of the company. Other study coauthors reported disclosures related to Celltrion, Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other companies.

Source: Ogura M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e543-53.

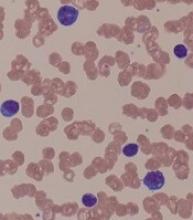

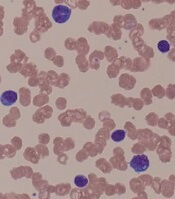

Bortezomib may overcome resistance in WM

Bortezomib may help overcome treatment resistance in patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) and CXCR4 mutations, according to a new study.

Researchers assessed the impact of treatment with bortezomib and rituximab in patients with WM, based on their CXCR4 mutation status.

The team found no significant difference in progression-free survival or overall survival between patients with CXCR4 mutations and those with wild-type CXCR4.

Romanos Sklavenitis-Pistofidis, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported this discovery in Blood.

The researchers’ main analysis included 43 patients with WM, 17 (39.5%) of whom had a CXCR4 mutation.

All patients who carried a CXCR4 mutation also had MYD88 L265P. Ten patients had frameshift mutations, one patient had a nonsense mutation, and six patients had missense mutations.

The patients were treated with bortezomib and rituximab, either upfront (n=14) or in the relapsed/refractory (n=29) setting, as part of a phase 2 trial.

Bortezomib was given at 1.6 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days for six cycles, and rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 during cycles one and four. Patients were taken off therapy after two cycles if they had progressive disease.

The median follow-up was 90.7 months.

The researchers found no significant difference between CXCR4-mutated and wild-type patients when it came to progression-free survival (P=0.994) or overall survival (P=0.407).

The researchers repeated their analysis after excluding six patients with missense mutations and accounting for different treatment settings and found that survival remained unchanged.

“We report, for the first time, that a bortezomib-based combination is impervious to the impact of CXCR4 mutations in a cohort of patients with WM,” the researchers wrote.

“Previously, we had shown this to be true in WM cell lines, whereby genetically engineering BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 to overexpress CXCR4 had no impact on bortezomib resistance.”

The researchers noted, however, that the mechanism at work here may be different than what is seen with bortezomib in other cancers.

“Different experiments have linked CXCR4 expression and bortezomib in a variety of ways in other hematological malignancies, including multiple myeloma,” the researchers wrote.

“However, despite the complicated association in those cancer types, in WM, there seems to be a consistently neutral effect of CXCR4 mutations on bortezomib resistance in both cell line and patient data.”

The researchers recommended that this theory be tested in a prospective trial of bortezomib-based therapy in WM patients with CXCR4 mutations.

Another thing to be determined, they said, is the role of rituximab in the survival results seen in the current analysis.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the International Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Foundation. One of the authors reported consulting and research funding from Takeda, which markets bortezomib, and other companies.

Bortezomib may help overcome treatment resistance in patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) and CXCR4 mutations, according to a new study.

Researchers assessed the impact of treatment with bortezomib and rituximab in patients with WM, based on their CXCR4 mutation status.

The team found no significant difference in progression-free survival or overall survival between patients with CXCR4 mutations and those with wild-type CXCR4.

Romanos Sklavenitis-Pistofidis, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported this discovery in Blood.

The researchers’ main analysis included 43 patients with WM, 17 (39.5%) of whom had a CXCR4 mutation.

All patients who carried a CXCR4 mutation also had MYD88 L265P. Ten patients had frameshift mutations, one patient had a nonsense mutation, and six patients had missense mutations.

The patients were treated with bortezomib and rituximab, either upfront (n=14) or in the relapsed/refractory (n=29) setting, as part of a phase 2 trial.

Bortezomib was given at 1.6 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days for six cycles, and rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 during cycles one and four. Patients were taken off therapy after two cycles if they had progressive disease.

The median follow-up was 90.7 months.

The researchers found no significant difference between CXCR4-mutated and wild-type patients when it came to progression-free survival (P=0.994) or overall survival (P=0.407).

The researchers repeated their analysis after excluding six patients with missense mutations and accounting for different treatment settings and found that survival remained unchanged.

“We report, for the first time, that a bortezomib-based combination is impervious to the impact of CXCR4 mutations in a cohort of patients with WM,” the researchers wrote.

“Previously, we had shown this to be true in WM cell lines, whereby genetically engineering BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 to overexpress CXCR4 had no impact on bortezomib resistance.”

The researchers noted, however, that the mechanism at work here may be different than what is seen with bortezomib in other cancers.

“Different experiments have linked CXCR4 expression and bortezomib in a variety of ways in other hematological malignancies, including multiple myeloma,” the researchers wrote.

“However, despite the complicated association in those cancer types, in WM, there seems to be a consistently neutral effect of CXCR4 mutations on bortezomib resistance in both cell line and patient data.”

The researchers recommended that this theory be tested in a prospective trial of bortezomib-based therapy in WM patients with CXCR4 mutations.

Another thing to be determined, they said, is the role of rituximab in the survival results seen in the current analysis.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the International Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Foundation. One of the authors reported consulting and research funding from Takeda, which markets bortezomib, and other companies.

Bortezomib may help overcome treatment resistance in patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) and CXCR4 mutations, according to a new study.

Researchers assessed the impact of treatment with bortezomib and rituximab in patients with WM, based on their CXCR4 mutation status.

The team found no significant difference in progression-free survival or overall survival between patients with CXCR4 mutations and those with wild-type CXCR4.

Romanos Sklavenitis-Pistofidis, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported this discovery in Blood.

The researchers’ main analysis included 43 patients with WM, 17 (39.5%) of whom had a CXCR4 mutation.

All patients who carried a CXCR4 mutation also had MYD88 L265P. Ten patients had frameshift mutations, one patient had a nonsense mutation, and six patients had missense mutations.

The patients were treated with bortezomib and rituximab, either upfront (n=14) or in the relapsed/refractory (n=29) setting, as part of a phase 2 trial.

Bortezomib was given at 1.6 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days for six cycles, and rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 during cycles one and four. Patients were taken off therapy after two cycles if they had progressive disease.

The median follow-up was 90.7 months.

The researchers found no significant difference between CXCR4-mutated and wild-type patients when it came to progression-free survival (P=0.994) or overall survival (P=0.407).

The researchers repeated their analysis after excluding six patients with missense mutations and accounting for different treatment settings and found that survival remained unchanged.

“We report, for the first time, that a bortezomib-based combination is impervious to the impact of CXCR4 mutations in a cohort of patients with WM,” the researchers wrote.

“Previously, we had shown this to be true in WM cell lines, whereby genetically engineering BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 to overexpress CXCR4 had no impact on bortezomib resistance.”

The researchers noted, however, that the mechanism at work here may be different than what is seen with bortezomib in other cancers.

“Different experiments have linked CXCR4 expression and bortezomib in a variety of ways in other hematological malignancies, including multiple myeloma,” the researchers wrote.

“However, despite the complicated association in those cancer types, in WM, there seems to be a consistently neutral effect of CXCR4 mutations on bortezomib resistance in both cell line and patient data.”

The researchers recommended that this theory be tested in a prospective trial of bortezomib-based therapy in WM patients with CXCR4 mutations.

Another thing to be determined, they said, is the role of rituximab in the survival results seen in the current analysis.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the International Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Foundation. One of the authors reported consulting and research funding from Takeda, which markets bortezomib, and other companies.

FDA expands approval of brentuximab vedotin to PTCL

The , marking the first FDA approval of a treatment for newly-diagnosed PTCL.

The drug, which is marketed by Seattle Genetics as Adcetris, is a monoclonal antibody that binds to CD30 protein found on some cancer cells.

It was previously approved for adult patients with untreated stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), cHL after relapse, cHL after stem cell transplant in patients at high risk for relapse or progression, systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) after other treatments fail, and primary cutaneous ALCL or CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides after other treatments fail.

The expanded approval, which followed the granting of Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designations for the supplemental Biologic License Application, was made using the FDA’s new Real-Time Oncology Review pilot program (RTOR). This program allows for data review and communication with a sponsor prior to official application submission with the goal of speeding up the review process.

The brentuximab vedotin approval now extends to previously untreated systemic ALCL and other CD30-expressing PTCLs in combination with chemotherapy.

Approval was based on the ECHELON-2 clinical trial involving 452 patients, which demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with certain types of PTCL who were treated first-line with either brentuximab vedotin plus chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone (CHP), or standard chemotherapy with CHP and vincristine (CHOP). Median PFS was 48 months vs. 21 months in the groups, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.71).

The FDA advises health care providers to “monitor patients for infusion reactions, life-threatening allergic reactions (anaphylaxis), neuropathy, fever, gastrointestinal complications, and infections,” according to a press release announcing the approval, which also states that patients should be monitored for tumor lysis syndrome, serious skin reactions, pulmonary toxicity, and hepatotoxicity.

The drug may cause harm to a developing fetus or newborn and should not be used in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. A Boxed Warning regarding risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is also included in the prescribing information.

The current standard of care for initial treatment of PTCL is multiagent chemotherapy – a treatment that “has not significantly changed in decades and is too often unsuccessful in leading to long-term remissions, underscoring the need for new treatments, ” Steven Horwitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in a statement issued by Seattle Genetics.

“With this approval, clinicians have the opportunity to transform the way newly diagnosed CD30-expressing PTCL patients are treated,” Dr. Horwitz said.

The ECHELON-2 data will be presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in San Diego on Monday, Dec. 3, 2018.

The , marking the first FDA approval of a treatment for newly-diagnosed PTCL.

The drug, which is marketed by Seattle Genetics as Adcetris, is a monoclonal antibody that binds to CD30 protein found on some cancer cells.

It was previously approved for adult patients with untreated stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), cHL after relapse, cHL after stem cell transplant in patients at high risk for relapse or progression, systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) after other treatments fail, and primary cutaneous ALCL or CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides after other treatments fail.

The expanded approval, which followed the granting of Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designations for the supplemental Biologic License Application, was made using the FDA’s new Real-Time Oncology Review pilot program (RTOR). This program allows for data review and communication with a sponsor prior to official application submission with the goal of speeding up the review process.

The brentuximab vedotin approval now extends to previously untreated systemic ALCL and other CD30-expressing PTCLs in combination with chemotherapy.

Approval was based on the ECHELON-2 clinical trial involving 452 patients, which demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with certain types of PTCL who were treated first-line with either brentuximab vedotin plus chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone (CHP), or standard chemotherapy with CHP and vincristine (CHOP). Median PFS was 48 months vs. 21 months in the groups, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.71).

The FDA advises health care providers to “monitor patients for infusion reactions, life-threatening allergic reactions (anaphylaxis), neuropathy, fever, gastrointestinal complications, and infections,” according to a press release announcing the approval, which also states that patients should be monitored for tumor lysis syndrome, serious skin reactions, pulmonary toxicity, and hepatotoxicity.

The drug may cause harm to a developing fetus or newborn and should not be used in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. A Boxed Warning regarding risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is also included in the prescribing information.

The current standard of care for initial treatment of PTCL is multiagent chemotherapy – a treatment that “has not significantly changed in decades and is too often unsuccessful in leading to long-term remissions, underscoring the need for new treatments, ” Steven Horwitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in a statement issued by Seattle Genetics.

“With this approval, clinicians have the opportunity to transform the way newly diagnosed CD30-expressing PTCL patients are treated,” Dr. Horwitz said.

The ECHELON-2 data will be presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in San Diego on Monday, Dec. 3, 2018.

The , marking the first FDA approval of a treatment for newly-diagnosed PTCL.

The drug, which is marketed by Seattle Genetics as Adcetris, is a monoclonal antibody that binds to CD30 protein found on some cancer cells.

It was previously approved for adult patients with untreated stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), cHL after relapse, cHL after stem cell transplant in patients at high risk for relapse or progression, systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) after other treatments fail, and primary cutaneous ALCL or CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides after other treatments fail.

The expanded approval, which followed the granting of Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designations for the supplemental Biologic License Application, was made using the FDA’s new Real-Time Oncology Review pilot program (RTOR). This program allows for data review and communication with a sponsor prior to official application submission with the goal of speeding up the review process.

The brentuximab vedotin approval now extends to previously untreated systemic ALCL and other CD30-expressing PTCLs in combination with chemotherapy.

Approval was based on the ECHELON-2 clinical trial involving 452 patients, which demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with certain types of PTCL who were treated first-line with either brentuximab vedotin plus chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone (CHP), or standard chemotherapy with CHP and vincristine (CHOP). Median PFS was 48 months vs. 21 months in the groups, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.71).

The FDA advises health care providers to “monitor patients for infusion reactions, life-threatening allergic reactions (anaphylaxis), neuropathy, fever, gastrointestinal complications, and infections,” according to a press release announcing the approval, which also states that patients should be monitored for tumor lysis syndrome, serious skin reactions, pulmonary toxicity, and hepatotoxicity.

The drug may cause harm to a developing fetus or newborn and should not be used in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. A Boxed Warning regarding risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is also included in the prescribing information.

The current standard of care for initial treatment of PTCL is multiagent chemotherapy – a treatment that “has not significantly changed in decades and is too often unsuccessful in leading to long-term remissions, underscoring the need for new treatments, ” Steven Horwitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in a statement issued by Seattle Genetics.

“With this approval, clinicians have the opportunity to transform the way newly diagnosed CD30-expressing PTCL patients are treated,” Dr. Horwitz said.

The ECHELON-2 data will be presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in San Diego on Monday, Dec. 3, 2018.

Quick FDA approval for brentuximab vedotin in PTCL

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a new indication for brentuximab vedotin (ADCETRIS®) less than 2 weeks after receiving the completed supplemental biologics license application (sBLA).

Brentuximab vedotin is now approved for use in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) to treat adults with previously untreated systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma or other CD30-expressing peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and PTCL not otherwise specified.

The FDA granted priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to the sBLA for brentuximab vedotin in this indication.

The FDA reviewed the sBLA under the Real-Time Oncology Review Pilot Program, which led to approval less than 2 weeks after the application was submitted in full.

“The Real-Time Oncology Review program allows the FDA to access key data prior to the official submission of the application, allowing the review team to begin their review earlier and communicate with the sponsor prior to the application’s actual submission,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products.

“When the sponsor submits the completed application, the review team will already be familiar with the data and be able to conduct a more efficient, timely, and thorough review.”

Trial data

The FDA’s approval is based on results from the phase 3 ECHELON-2 trial (NCT01777152).

Seattle Genetics, Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited announced results from this trial last month. Additional results are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 997).

The trial enrolled 452 patients with CD30-positive PTCL. The patients were randomized to receive brentuximab vedotin (BV) plus CHP or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP).

The objective response rate was 83% in the BV-CHP arm and 72% in the CHOP arm (P=0.003). The complete response rate was 68% and 56%, respectively (P=0.007).

Progression-free survival was significantly better in the BV-CHP arm than in the CHOP arm (hazard ratio=0.71; P=0.011), as was overall survival (hazard ratio=0.66; P=0.024).

The most common adverse events of any grade that occurred in at least 20% of patients in the BV-CHP arm were peripheral neuropathy, nausea, diarrhea, neutropenia, lymphopenia, fatigue, mucositis, constipation, alopecia, pyrexia, vomiting, and anemia.

Serious adverse events occurring in at least 2% of patients in the BV-CHP arm included febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, pyrexia, and sepsis.

Results of this trial suggest prophylactic growth factors should be given to previously untreated PTCL patients receiving BV-CHP (starting at cycle 1).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a new indication for brentuximab vedotin (ADCETRIS®) less than 2 weeks after receiving the completed supplemental biologics license application (sBLA).

Brentuximab vedotin is now approved for use in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) to treat adults with previously untreated systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma or other CD30-expressing peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and PTCL not otherwise specified.

The FDA granted priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to the sBLA for brentuximab vedotin in this indication.

The FDA reviewed the sBLA under the Real-Time Oncology Review Pilot Program, which led to approval less than 2 weeks after the application was submitted in full.

“The Real-Time Oncology Review program allows the FDA to access key data prior to the official submission of the application, allowing the review team to begin their review earlier and communicate with the sponsor prior to the application’s actual submission,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products.

“When the sponsor submits the completed application, the review team will already be familiar with the data and be able to conduct a more efficient, timely, and thorough review.”

Trial data

The FDA’s approval is based on results from the phase 3 ECHELON-2 trial (NCT01777152).

Seattle Genetics, Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited announced results from this trial last month. Additional results are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 997).

The trial enrolled 452 patients with CD30-positive PTCL. The patients were randomized to receive brentuximab vedotin (BV) plus CHP or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP).

The objective response rate was 83% in the BV-CHP arm and 72% in the CHOP arm (P=0.003). The complete response rate was 68% and 56%, respectively (P=0.007).

Progression-free survival was significantly better in the BV-CHP arm than in the CHOP arm (hazard ratio=0.71; P=0.011), as was overall survival (hazard ratio=0.66; P=0.024).

The most common adverse events of any grade that occurred in at least 20% of patients in the BV-CHP arm were peripheral neuropathy, nausea, diarrhea, neutropenia, lymphopenia, fatigue, mucositis, constipation, alopecia, pyrexia, vomiting, and anemia.

Serious adverse events occurring in at least 2% of patients in the BV-CHP arm included febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, pyrexia, and sepsis.

Results of this trial suggest prophylactic growth factors should be given to previously untreated PTCL patients receiving BV-CHP (starting at cycle 1).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a new indication for brentuximab vedotin (ADCETRIS®) less than 2 weeks after receiving the completed supplemental biologics license application (sBLA).

Brentuximab vedotin is now approved for use in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) to treat adults with previously untreated systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma or other CD30-expressing peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and PTCL not otherwise specified.

The FDA granted priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to the sBLA for brentuximab vedotin in this indication.

The FDA reviewed the sBLA under the Real-Time Oncology Review Pilot Program, which led to approval less than 2 weeks after the application was submitted in full.

“The Real-Time Oncology Review program allows the FDA to access key data prior to the official submission of the application, allowing the review team to begin their review earlier and communicate with the sponsor prior to the application’s actual submission,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products.

“When the sponsor submits the completed application, the review team will already be familiar with the data and be able to conduct a more efficient, timely, and thorough review.”

Trial data

The FDA’s approval is based on results from the phase 3 ECHELON-2 trial (NCT01777152).

Seattle Genetics, Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited announced results from this trial last month. Additional results are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 997).

The trial enrolled 452 patients with CD30-positive PTCL. The patients were randomized to receive brentuximab vedotin (BV) plus CHP or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP).

The objective response rate was 83% in the BV-CHP arm and 72% in the CHOP arm (P=0.003). The complete response rate was 68% and 56%, respectively (P=0.007).

Progression-free survival was significantly better in the BV-CHP arm than in the CHOP arm (hazard ratio=0.71; P=0.011), as was overall survival (hazard ratio=0.66; P=0.024).

The most common adverse events of any grade that occurred in at least 20% of patients in the BV-CHP arm were peripheral neuropathy, nausea, diarrhea, neutropenia, lymphopenia, fatigue, mucositis, constipation, alopecia, pyrexia, vomiting, and anemia.

Serious adverse events occurring in at least 2% of patients in the BV-CHP arm included febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, pyrexia, and sepsis.

Results of this trial suggest prophylactic growth factors should be given to previously untreated PTCL patients receiving BV-CHP (starting at cycle 1).

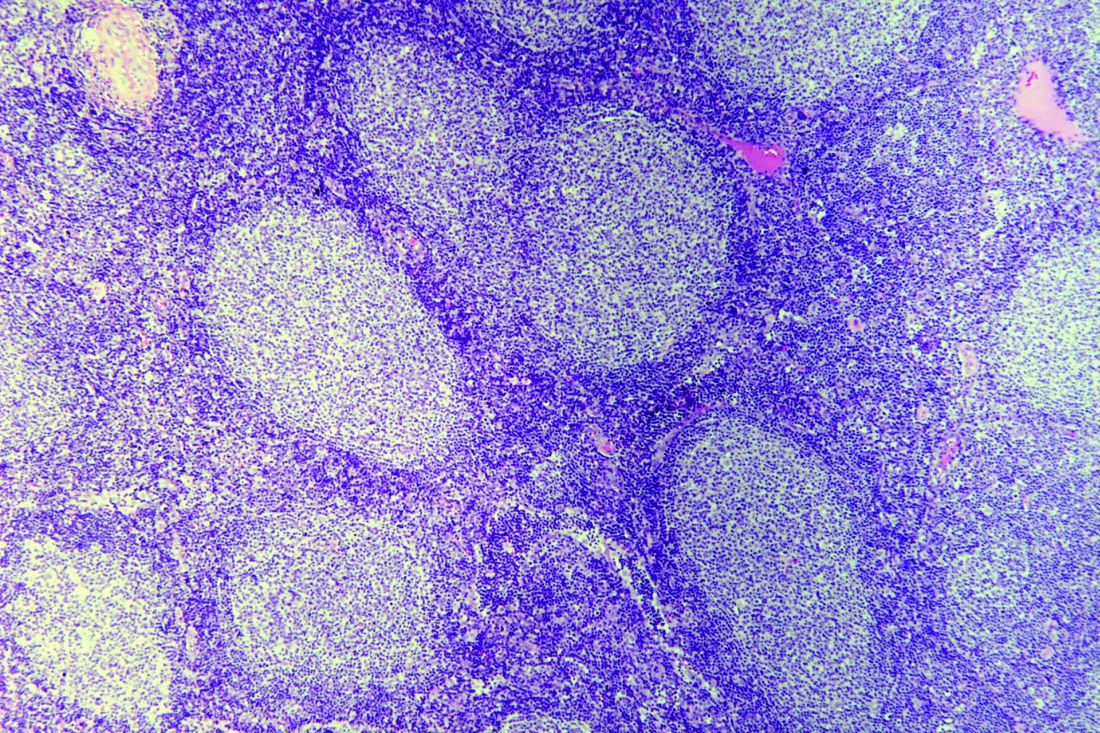

R-CHOP effective as first-line treatment in FL

Long-term data suggest R-CHOP can be effective as first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

In a phase 2-3 trial, investigators compared R-CHOP-21 and R-CHOP-14 in a cohort of patients with indolent lymphomas, most of whom had FL.

Ten-year survival rates were similar between the R-CHOP-21 and R-CHOP-14 groups, with progression-free survival (PFS) rates of 33% and 39%, respectively, and overall survival (OS) rates of 81% and 85%, respectively.

The investigators did note that 9% of patients in each treatment group developed secondary malignancies, and grade 3 infections were a concern as well.

Takashi Watanabe, MD, PhD, of Mie University in Japan, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Haematology.

The trial (JCOG0203) included 300 patients with stage III or IV indolent B-cell lymphomas from 44 Japanese hospitals.

Most patients (n=248) had grade 1-3a FL, 17 had grade 3b FL, 6 had marginal zone lymphoma, 6 had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 had mantle cell lymphoma, 2 had small lymphocytic lymphoma, 1 had plasmacytoma, 13 had other indolent B-cell lymphomas, and 3 had other lymphomas.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of R-CHOP 21 (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 3 weeks) or R-CHOP 14 (R-CHOP every 2 weeks with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor support). Neither group received rituximab maintenance.

Overall results

The median follow-up was 11.2 years (interquartile range, 10.1 to 12.7 years).

The 10-year PFS was 33% in the R-CHOP-21 group and 39% in the R-CHOP-14 group (hazard ratio=0.89). The 10-year OS was 81% and 85%, respectively (hazard ratio=0.87).

At 10 years, the incidence of secondary malignancies was 9% in both the R-CHOP-21 group (14/148) and the R-CHOP-14 group (14/151).

The most frequent solid tumor malignancies were stomach (n=5), lung (n=4), colon (n=3), bladder (n=2), and prostate (n=2) cancers. Hematologic malignancies included myelodysplastic syndromes (n=6), acute myeloid leukemia (n=2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), and chronic myeloid leukemia (n=1).

There were nine deaths from secondary malignancies, four in the R-CHOP-21 group and five in the R-CHOP-14 group.

The rate of grade 3 adverse events was 18% (n=53) for the entire cohort. Grade 3 infections occurred in 23% of the R-CHOP-21 group and 12% of the R-CHOP-14 group.

Focus on grade 1-3a FL

Among the 248 patients with grade 1-3a FL, the PFS (for both treatment groups) was 45% at 5 years, 39% at 8 years, and 36% at 10 years. The OS was 94% at 5 years, 87% at 8 years, and 85% at 10 years.

Histological transformation was observed in 11% of the patients who had grade 1-3a FL at enrollment. The cumulative incidence of histological transformation was 2.4% at 3 years, 3.2% at 5 years, 8.5% at 8 years, and 9.3% at 10 years.

Secondary malignancies occurred in 10% (12/125) of the R-CHOP-21 group and 11% (13/123) of the R-CHOP-14 group.

The cumulative incidence of hematologic secondary malignancies at 10 years was 2.9%.

The investigators noted that the actual incidence of secondary solid tumors or hematologic malignancies apart from the setting of autologous stem cell transplants is not known. They emphasized that patients should be followed beyond 10 years to ensure the risk of secondary malignancies is not underestimated.

“Clinicians choosing a first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma should be cautious of secondary malignancies caused by immunochemotherapy and severe complications of infectious diseases in the long-term follow-up—both of which could lead to death,” the investigators wrote.

This study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan.

Dr. Wantanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy at Mie University. Multiple co-authors reported similar relationships.

Long-term data suggest R-CHOP can be effective as first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

In a phase 2-3 trial, investigators compared R-CHOP-21 and R-CHOP-14 in a cohort of patients with indolent lymphomas, most of whom had FL.

Ten-year survival rates were similar between the R-CHOP-21 and R-CHOP-14 groups, with progression-free survival (PFS) rates of 33% and 39%, respectively, and overall survival (OS) rates of 81% and 85%, respectively.

The investigators did note that 9% of patients in each treatment group developed secondary malignancies, and grade 3 infections were a concern as well.

Takashi Watanabe, MD, PhD, of Mie University in Japan, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Haematology.

The trial (JCOG0203) included 300 patients with stage III or IV indolent B-cell lymphomas from 44 Japanese hospitals.

Most patients (n=248) had grade 1-3a FL, 17 had grade 3b FL, 6 had marginal zone lymphoma, 6 had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 had mantle cell lymphoma, 2 had small lymphocytic lymphoma, 1 had plasmacytoma, 13 had other indolent B-cell lymphomas, and 3 had other lymphomas.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of R-CHOP 21 (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 3 weeks) or R-CHOP 14 (R-CHOP every 2 weeks with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor support). Neither group received rituximab maintenance.

Overall results

The median follow-up was 11.2 years (interquartile range, 10.1 to 12.7 years).

The 10-year PFS was 33% in the R-CHOP-21 group and 39% in the R-CHOP-14 group (hazard ratio=0.89). The 10-year OS was 81% and 85%, respectively (hazard ratio=0.87).

At 10 years, the incidence of secondary malignancies was 9% in both the R-CHOP-21 group (14/148) and the R-CHOP-14 group (14/151).

The most frequent solid tumor malignancies were stomach (n=5), lung (n=4), colon (n=3), bladder (n=2), and prostate (n=2) cancers. Hematologic malignancies included myelodysplastic syndromes (n=6), acute myeloid leukemia (n=2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), and chronic myeloid leukemia (n=1).

There were nine deaths from secondary malignancies, four in the R-CHOP-21 group and five in the R-CHOP-14 group.

The rate of grade 3 adverse events was 18% (n=53) for the entire cohort. Grade 3 infections occurred in 23% of the R-CHOP-21 group and 12% of the R-CHOP-14 group.

Focus on grade 1-3a FL

Among the 248 patients with grade 1-3a FL, the PFS (for both treatment groups) was 45% at 5 years, 39% at 8 years, and 36% at 10 years. The OS was 94% at 5 years, 87% at 8 years, and 85% at 10 years.

Histological transformation was observed in 11% of the patients who had grade 1-3a FL at enrollment. The cumulative incidence of histological transformation was 2.4% at 3 years, 3.2% at 5 years, 8.5% at 8 years, and 9.3% at 10 years.

Secondary malignancies occurred in 10% (12/125) of the R-CHOP-21 group and 11% (13/123) of the R-CHOP-14 group.

The cumulative incidence of hematologic secondary malignancies at 10 years was 2.9%.

The investigators noted that the actual incidence of secondary solid tumors or hematologic malignancies apart from the setting of autologous stem cell transplants is not known. They emphasized that patients should be followed beyond 10 years to ensure the risk of secondary malignancies is not underestimated.

“Clinicians choosing a first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma should be cautious of secondary malignancies caused by immunochemotherapy and severe complications of infectious diseases in the long-term follow-up—both of which could lead to death,” the investigators wrote.

This study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan.

Dr. Wantanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy at Mie University. Multiple co-authors reported similar relationships.

Long-term data suggest R-CHOP can be effective as first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

In a phase 2-3 trial, investigators compared R-CHOP-21 and R-CHOP-14 in a cohort of patients with indolent lymphomas, most of whom had FL.

Ten-year survival rates were similar between the R-CHOP-21 and R-CHOP-14 groups, with progression-free survival (PFS) rates of 33% and 39%, respectively, and overall survival (OS) rates of 81% and 85%, respectively.

The investigators did note that 9% of patients in each treatment group developed secondary malignancies, and grade 3 infections were a concern as well.

Takashi Watanabe, MD, PhD, of Mie University in Japan, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Haematology.

The trial (JCOG0203) included 300 patients with stage III or IV indolent B-cell lymphomas from 44 Japanese hospitals.

Most patients (n=248) had grade 1-3a FL, 17 had grade 3b FL, 6 had marginal zone lymphoma, 6 had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 had mantle cell lymphoma, 2 had small lymphocytic lymphoma, 1 had plasmacytoma, 13 had other indolent B-cell lymphomas, and 3 had other lymphomas.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of R-CHOP 21 (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 3 weeks) or R-CHOP 14 (R-CHOP every 2 weeks with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor support). Neither group received rituximab maintenance.

Overall results

The median follow-up was 11.2 years (interquartile range, 10.1 to 12.7 years).

The 10-year PFS was 33% in the R-CHOP-21 group and 39% in the R-CHOP-14 group (hazard ratio=0.89). The 10-year OS was 81% and 85%, respectively (hazard ratio=0.87).

At 10 years, the incidence of secondary malignancies was 9% in both the R-CHOP-21 group (14/148) and the R-CHOP-14 group (14/151).

The most frequent solid tumor malignancies were stomach (n=5), lung (n=4), colon (n=3), bladder (n=2), and prostate (n=2) cancers. Hematologic malignancies included myelodysplastic syndromes (n=6), acute myeloid leukemia (n=2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), and chronic myeloid leukemia (n=1).

There were nine deaths from secondary malignancies, four in the R-CHOP-21 group and five in the R-CHOP-14 group.

The rate of grade 3 adverse events was 18% (n=53) for the entire cohort. Grade 3 infections occurred in 23% of the R-CHOP-21 group and 12% of the R-CHOP-14 group.

Focus on grade 1-3a FL

Among the 248 patients with grade 1-3a FL, the PFS (for both treatment groups) was 45% at 5 years, 39% at 8 years, and 36% at 10 years. The OS was 94% at 5 years, 87% at 8 years, and 85% at 10 years.

Histological transformation was observed in 11% of the patients who had grade 1-3a FL at enrollment. The cumulative incidence of histological transformation was 2.4% at 3 years, 3.2% at 5 years, 8.5% at 8 years, and 9.3% at 10 years.

Secondary malignancies occurred in 10% (12/125) of the R-CHOP-21 group and 11% (13/123) of the R-CHOP-14 group.

The cumulative incidence of hematologic secondary malignancies at 10 years was 2.9%.

The investigators noted that the actual incidence of secondary solid tumors or hematologic malignancies apart from the setting of autologous stem cell transplants is not known. They emphasized that patients should be followed beyond 10 years to ensure the risk of secondary malignancies is not underestimated.

“Clinicians choosing a first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma should be cautious of secondary malignancies caused by immunochemotherapy and severe complications of infectious diseases in the long-term follow-up—both of which could lead to death,” the investigators wrote.

This study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan.

Dr. Wantanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy at Mie University. Multiple co-authors reported similar relationships.

R-CHOP looks viable as first line in follicular lymphoma

A decade of follow-up data suggest that patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma may derive long-term benefit from first-line therapy with the R-CHOP regimen, according to investigators in Japan.

Among patients with untreated follicular and other indolent B-cell lymphomas enrolled in a randomized phase 2/3 trial, the 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate for patients assigned to R-CHOP-21 (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 3 weeks) was 33%, and the 10-year PFS rate for patients assigned to R-CHOP-14 (R-CHOP every 2 weeks with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF] support] was 39%, and these PFS rates did not differ between the treatment arms, Takashi Watanabe, MD, PhD, from Mie University in Tsu, Japan, and his colleagues reported in the Lancet Haematology.

They also found that, compared with therapeutic regimens prior to the introduction of rituximab, R-CHOP was associated with a reduced likelihood of histological transformation of follicular lymphoma into a poor-prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), with no apparent increase in risk of secondary malignancies.

“The gold-standard, first-line treatment in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma remains undetermined. However, because of the reduction in incidence of transformation without an increase in either secondary malignancies or fatal infectious events, the R-CHOP regimen should be a candidate for standard treatment, particularly from the viewpoint of long-term follow-up,” the investigators wrote

The JCOG0203 trial, which began enrollment in September 2002, included patients with stage III or IV indolent B-cell lymphomas, including grades 1-3 follicular lymphoma, from 44 Japanese hospitals. The patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of either R-CHOP-14 plus G-CSF or R-CHOP-21 administered once daily for 6 days beginning on day 8 of every cycle). Patients did not receive rituximab maintenance in either group.

In the primary analysis of the trial, published in 2011, the investigators reported that in 299 patients there were no significant differences in either PFS or 6-year overall survival (OS).

In the current analysis, the investigators reported that, for 248 patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma, the 8-year PFS rate was 39% and the 10-year PFS rate was 36%.

The cumulative incidence of histological transformation was 3.2% at 5 years, 8.5% at 8 years, and 9.3% 10 years after the last patient was enrolled.

“In our study, survival after histological transformation was still poor; therefore, reducing histological transformation remains a crucial issue for patients with follicular lymphoma,” the investigators wrote.

The cumulative incidence of secondary malignancies at 10 years was 8.1%, and the cumulative incidence of hematological secondary malignancies was 2.9%.

The investigators noted that the actual incidence of secondary solid tumors or hematologic malignancies apart from the setting of autologous stem cell transplants is not known and emphasized that patients should be followed beyond 10 years to ensure that the risk of secondary malignancies is not underestimated.

“Clinicians choosing a first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma should be cautious of secondary malignancies caused by immunochemotherapy and severe complications of infectious diseases in the long-term follow-up – both of which could lead to death,” they advised.

The study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan. Dr. Watanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy at Mie University. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships.

SOURCE: Watanabe T et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e520-31.

A decade of follow-up data suggest that patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma may derive long-term benefit from first-line therapy with the R-CHOP regimen, according to investigators in Japan.

Among patients with untreated follicular and other indolent B-cell lymphomas enrolled in a randomized phase 2/3 trial, the 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate for patients assigned to R-CHOP-21 (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 3 weeks) was 33%, and the 10-year PFS rate for patients assigned to R-CHOP-14 (R-CHOP every 2 weeks with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF] support] was 39%, and these PFS rates did not differ between the treatment arms, Takashi Watanabe, MD, PhD, from Mie University in Tsu, Japan, and his colleagues reported in the Lancet Haematology.

They also found that, compared with therapeutic regimens prior to the introduction of rituximab, R-CHOP was associated with a reduced likelihood of histological transformation of follicular lymphoma into a poor-prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), with no apparent increase in risk of secondary malignancies.

“The gold-standard, first-line treatment in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma remains undetermined. However, because of the reduction in incidence of transformation without an increase in either secondary malignancies or fatal infectious events, the R-CHOP regimen should be a candidate for standard treatment, particularly from the viewpoint of long-term follow-up,” the investigators wrote

The JCOG0203 trial, which began enrollment in September 2002, included patients with stage III or IV indolent B-cell lymphomas, including grades 1-3 follicular lymphoma, from 44 Japanese hospitals. The patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of either R-CHOP-14 plus G-CSF or R-CHOP-21 administered once daily for 6 days beginning on day 8 of every cycle). Patients did not receive rituximab maintenance in either group.

In the primary analysis of the trial, published in 2011, the investigators reported that in 299 patients there were no significant differences in either PFS or 6-year overall survival (OS).

In the current analysis, the investigators reported that, for 248 patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma, the 8-year PFS rate was 39% and the 10-year PFS rate was 36%.

The cumulative incidence of histological transformation was 3.2% at 5 years, 8.5% at 8 years, and 9.3% 10 years after the last patient was enrolled.

“In our study, survival after histological transformation was still poor; therefore, reducing histological transformation remains a crucial issue for patients with follicular lymphoma,” the investigators wrote.

The cumulative incidence of secondary malignancies at 10 years was 8.1%, and the cumulative incidence of hematological secondary malignancies was 2.9%.

The investigators noted that the actual incidence of secondary solid tumors or hematologic malignancies apart from the setting of autologous stem cell transplants is not known and emphasized that patients should be followed beyond 10 years to ensure that the risk of secondary malignancies is not underestimated.

“Clinicians choosing a first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma should be cautious of secondary malignancies caused by immunochemotherapy and severe complications of infectious diseases in the long-term follow-up – both of which could lead to death,” they advised.

The study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan. Dr. Watanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy at Mie University. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships.

SOURCE: Watanabe T et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e520-31.

A decade of follow-up data suggest that patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma may derive long-term benefit from first-line therapy with the R-CHOP regimen, according to investigators in Japan.

Among patients with untreated follicular and other indolent B-cell lymphomas enrolled in a randomized phase 2/3 trial, the 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate for patients assigned to R-CHOP-21 (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 3 weeks) was 33%, and the 10-year PFS rate for patients assigned to R-CHOP-14 (R-CHOP every 2 weeks with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF] support] was 39%, and these PFS rates did not differ between the treatment arms, Takashi Watanabe, MD, PhD, from Mie University in Tsu, Japan, and his colleagues reported in the Lancet Haematology.

They also found that, compared with therapeutic regimens prior to the introduction of rituximab, R-CHOP was associated with a reduced likelihood of histological transformation of follicular lymphoma into a poor-prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), with no apparent increase in risk of secondary malignancies.

“The gold-standard, first-line treatment in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma remains undetermined. However, because of the reduction in incidence of transformation without an increase in either secondary malignancies or fatal infectious events, the R-CHOP regimen should be a candidate for standard treatment, particularly from the viewpoint of long-term follow-up,” the investigators wrote

The JCOG0203 trial, which began enrollment in September 2002, included patients with stage III or IV indolent B-cell lymphomas, including grades 1-3 follicular lymphoma, from 44 Japanese hospitals. The patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of either R-CHOP-14 plus G-CSF or R-CHOP-21 administered once daily for 6 days beginning on day 8 of every cycle). Patients did not receive rituximab maintenance in either group.

In the primary analysis of the trial, published in 2011, the investigators reported that in 299 patients there were no significant differences in either PFS or 6-year overall survival (OS).

In the current analysis, the investigators reported that, for 248 patients with grade 1-3a follicular lymphoma, the 8-year PFS rate was 39% and the 10-year PFS rate was 36%.

The cumulative incidence of histological transformation was 3.2% at 5 years, 8.5% at 8 years, and 9.3% 10 years after the last patient was enrolled.

“In our study, survival after histological transformation was still poor; therefore, reducing histological transformation remains a crucial issue for patients with follicular lymphoma,” the investigators wrote.

The cumulative incidence of secondary malignancies at 10 years was 8.1%, and the cumulative incidence of hematological secondary malignancies was 2.9%.

The investigators noted that the actual incidence of secondary solid tumors or hematologic malignancies apart from the setting of autologous stem cell transplants is not known and emphasized that patients should be followed beyond 10 years to ensure that the risk of secondary malignancies is not underestimated.

“Clinicians choosing a first-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma should be cautious of secondary malignancies caused by immunochemotherapy and severe complications of infectious diseases in the long-term follow-up – both of which could lead to death,” they advised.

The study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan. Dr. Watanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy at Mie University. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships.

SOURCE: Watanabe T et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e520-31.

FROM LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Approximately one-third of patients treated with R-CHOP-14 plus G-CSF or R-CHOP-21 had no disease progression after 10 years of follow-up.

Study details: Long-term analysis of a randomized phase 2/3 trial in 299 patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund of Japan. Dr. Wantanabe has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Taisho Toyama, Celgene, Nippon Shinyaku, and Novartis and funding resources from TakaraBio and United Immunity to support the Department of Immuno-Gene Therapy in Mie University. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships.

Source: Wantanabe T et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e520-31.

Bortezomib may unlock resistance in WM with mutations

The use of bortezomib may help overcome treatment resistance in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) with CXCR4 mutations, according to new research.

Romanos Sklavenitis-Pistofidis, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues compared the effects of treatment with bortezomib/rituximab in patients with WM based on their CXCR4 mutation status. They found no significant difference in progression-free survival (Log-rank, P = .994) or overall survival (Log-rank, P = .407) when comparing patients who have CXCR4 mutations with those who have CXCR4 wild type.

“We report for the first time that a bortezomib-based combination is impervious to the impact of CXCR4 mutations in a cohort of patients with WM,” the researchers wrote in Blood. “Previously, we had shown this to be true in WM cell lines, whereby genetically engineering BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 to overexpress CXCR4 had no impact on bortezomib resistance.”

The researchers noted, however, that the mechanism at work may be different than that seen with bortezomib in other cancers.

“Different experiments have linked CXCR4 expression and bortezomib in a variety of ways in other hematological malignancies, including multiple myeloma. However, despite the complicated association in those cancer types, in WM there seems to be a consistently neutral effect of CXCR4 mutations on bortezomib resistance in both cell line and patient data,” they wrote.

The researchers recommended that the theory be tested in a prospective trial of bortezomib-based therapy in WM patients with CXCR4 mutations. Another question to be investigated, they pointed out, is the role of rituximab in the survival results seen in the current analysis.

The study included 63 patients with WM who were treated with bortezomib/rituximab either as upfront treatment or in the relapsed/refractory setting as part of a phase 2 trial.

Bortezomib was given by IV weekly at 1.6 mg/m2 for six cycles and rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 during cycles one and four. Patients were taken off therapy after two cycles if they had progressive disease.

The researchers excluded 20 patients from the study because of a lack of material for genotyping. However, they noted that their clinical characteristics were not different from those patients who were included.

Out of 43 patients who were genotyped for CXCR4, 17 patients had a mutation. All patients who carried a CXCR4 mutation also had MYD88 L265P. Ten patients had frameshift mutations, one patient had a nonsense mutation, and six patients had missense mutations. The median follow-up of the analysis was 90.7 months.

The researchers repeated the analysis after excluding six patients with missense mutations and accounting for different treatment settings and found that survival remained unchanged.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the International Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Foundation. One of the authors reported consulting and research funding from Takeda, which markets bortezomib, and other companies.

SOURCE: Sklavenitis-Pistofidis R et al. Blood. 2018 Oct 26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-863241.

The use of bortezomib may help overcome treatment resistance in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) with CXCR4 mutations, according to new research.

Romanos Sklavenitis-Pistofidis, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues compared the effects of treatment with bortezomib/rituximab in patients with WM based on their CXCR4 mutation status. They found no significant difference in progression-free survival (Log-rank, P = .994) or overall survival (Log-rank, P = .407) when comparing patients who have CXCR4 mutations with those who have CXCR4 wild type.

“We report for the first time that a bortezomib-based combination is impervious to the impact of CXCR4 mutations in a cohort of patients with WM,” the researchers wrote in Blood. “Previously, we had shown this to be true in WM cell lines, whereby genetically engineering BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 to overexpress CXCR4 had no impact on bortezomib resistance.”

The researchers noted, however, that the mechanism at work may be different than that seen with bortezomib in other cancers.

“Different experiments have linked CXCR4 expression and bortezomib in a variety of ways in other hematological malignancies, including multiple myeloma. However, despite the complicated association in those cancer types, in WM there seems to be a consistently neutral effect of CXCR4 mutations on bortezomib resistance in both cell line and patient data,” they wrote.

The researchers recommended that the theory be tested in a prospective trial of bortezomib-based therapy in WM patients with CXCR4 mutations. Another question to be investigated, they pointed out, is the role of rituximab in the survival results seen in the current analysis.