User login

2018 Update on bone health

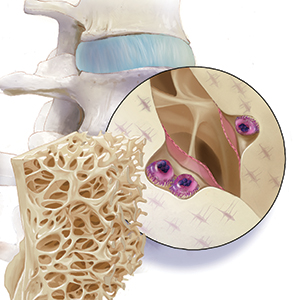

As ObGyns, we are the first-line health care providers for our menopausal patients in terms of identifying, preventing, and initiating treatment for women at risk for fragility fractures. Osteoporosis is probably the most important risk factor for bone health, although sarcopenia, frailty, poor eyesight, and falls also play a significant role in bone health and fragility fracture.

In 2005, more than 2 million incident fractures were reported in the United States, with a total cost of $17 billion.1 By 2025, annual fractures and costs are expected to rise by almost 50%. People who are 65 to 74 years of age will likely experience the largest increase in fracture—greater than 87%.1

Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative study showed that the number of women who had a clinical fracture in 1 year exceeded all the cases of myocardial infarction, stroke, and breast cancer combined.2 Furthermore, the morbidity and mortality rates for fractures are staggering. Thirty percent of women with a hip fracture will be dead within 1 year.3 So, although many patients fear developing breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease remains the number 1 cause of death, the impact of maintaining and protecting bone health cannot be emphasized enough.

_

WHI incidental findings: Hormone-treated menopausal women had decreased hip fracture rate

Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al; WHI Investigators. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318:927-938.

Manson and colleagues examined the total and cause-specific cumulative mortality of the 2 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) hormone therapy trials. This was an observational follow-up of US multiethnic postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years (mean age at baseline, 63.4 years) enrolled in 2 randomized clinical trials between 1993 and 1998 and followed up through December 31, 2014. A total of 27,347 women were randomly assigned to treatment.

Treatment groups

Depending on the presence or absence of a uterus, women received conjugated equine estrogens (CEE, 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 2.5 mg/d) (n = 8,506) or placebo (n = 8,102) for a median of 5.6 years or CEE alone (n = 5,310) versus placebo (n = 5,429) for a median of 7.2 years. All-cause mortality (the primary outcome) and cause-specific mortality (cardiovascular disease mortality, cancer mortality, and other major causes of mortality) were analyzed in the 2 trials pooled and in each trial individually.

All-cause and cause-specific mortality findings

Mortality follow-up was available for more than 98% of participants. During the cumulative 18-year follow-up, 7,489 deaths occurred. In the overall pooled cohort, all-cause mortality in the hormone therapy group was 27.1% compared with 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.99 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.94–1.03]). In the CEE plus MPA group, the HR was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.96–1.08). For those in the CEE-alone group, the HR was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88–1.01).

In the pooled cohort for cardiovascular mortality, the HR was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.92–1.08 [8.9% with hormone therapy vs 9.0% with placebo]). For total cancer mortality, the HR was 1.03 (95% CI, 0.95–1.12 [8.2% with hormone therapy vs 8.0% with placebo]). For other causes, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.88–1.02 [10.0% with hormone therapy vs 10.7% with placebo]). Results did not differ significantly between trials.

Key takeaway

The study authors concluded that among postmenopausal women, hormone therapy with CEE plus MPA for a median of 5.6 years or with CEE alone for a median of 7.2 years was not associated with risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, or cancer mortality during a cumulative follow-up of 18 years.

Postmenopausal hormone therapy is arguably the most effective “bone drug” available. While all other antiresorptive agents show hip fracture efficacy only in subgroup analyses of the highest-risk patients (women with established osteoporosis, who often already have pre-existing vertebral fractures), the hormone-treated women in the WHI—who were not chosen for having low bone mass (in fact, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DXA] scores were not even recorded)—still had a statistically significant decrease in hip fracture as an adverse event when compared with placebo-treated women. Increasing data on the long-term safety of hormone therapy in menopausal patients will perhaps encourage its greater use from a bone health perspective.

Continue to: Appropriate to defer DXA testing to age 65...

Appropriate to defer DXA testing to age 65 when baseline FRAX score is below treatment level

Gourlay ML, Overman RA, Fine JP, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Time to clinically relevant fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e15-862.e23.

Gourlay ML, Fine JP, Preisser JS, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:225-233.

Many clinicians used to (and still do) order bone mineral density (BMD) testing at 23-month intervals because that was what insurance would allow. Gourlay and colleagues previously published a study on BMD testing intervals and the time it takes to develop osteoporosis. I covered that information in previous Updates.4,5

To recap, Gourlay and colleagues studied 4,957 women, 67 years of age or older, with normal BMD or osteopenia and with no history of hip or clinical vertebral fracture or of treatment for osteoporosis; the women were followed prospectively for up to 15 years. The estimated time for 10% of women to make the transition to osteoporosis was 16.8 years for those with normal BMD, 4.7 years for those with moderate osteopenia, and 1.1 years for women with advanced osteopenia.

Today, FRAX is recommended to assess need for treatment

Older treatment recommendations involved determining various osteopenic BMD levels and the presence or absence of certain risk factors. More recently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation and many medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have recommended using the FRAX fracture prediction algorithm (available at https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/) instead of T-scores to consider initiating pharmacotherapy.

The FRAX calculation tool uses information such as the country where the patient lives, age, sex, height, weight, history of previous fracture, parental fracture, current smoking, glucocorticoid use, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, alcohol use of 3 or more units per day, and, if available, BMD determination at the femoral neck. It then yields the 10-year absolute risk of hip fracture and any major osteoporotic fracture for that individual or, more precisely, for an individual like that.

In the United States, accepted levels for cost-effective pharmacotherapy are a 10-year absolute risk of hip fracture of 3% or major osteoporotic fracture of 20%.

Continue to: Age also is a key factor in fracture risk assessment

Age also is a key factor in fracture risk assessment

Gourlay and colleagues more recently conducted a retrospective analysis of new occurrence of treatment-level fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women (50 years of age and older) before they received pharmacologic treatment and before they experienced a first hip or clinical vertebral fracture.

In 54,280 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 without a BMD test, the time for 10% to develop a treatment-level FRAX score could not be estimated accurately because of the rarity of treatment-level scores. In 6,096 women who had FRAX scores calculated with their BMD score, the estimated time to treatment-level FRAX was 7.6 years for those 65 to 69 and 5.1 years for 75 to 79 year olds. Furthermore, of 17,967 women aged 50 to 64 with a screening-level FRAX at baseline, only 100 (0.6%) experienced a hip or clinical vertebral fracture by age 65.

The investigators concluded that, “Postmenopausal women with sub-threshold fracture risk scores at baseline were unlikely to develop a treatment-level FRAX score between ages 50 and 64 years. After age 65, the increased incidence of treatment-level fracture risk scores, osteoporosis, and major osteoporotic fracture supports more frequent consideration of FRAX and bone mineral density testing.”

Many health care providers begin BMD testing early in menopause. Bone mass results may motivate patients to initiate healthy lifestyle choices, such as adequate dietary calcium, vitamin D supplementation, exercise, moderate alcohol use, smoking cessation, and fall prevention strategies. However, providers and their patients should be aware that if the fracture risk is beneath the threshold score at baseline, the risk of experiencing an osteoporotic fracture prior to age 65 is extremely low, and this should be taken into account before prescribing pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, as stated, FRAX can be performed without a DXA score. When the result is beneath a treatment level in a woman under 65, DXA testing may be deferred until age 65.

Continue to: USPSTF offers updated recommendations for osteoporosis screening

USPSTF offers updated recommendations for osteoporosis screening

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:2521-2531.

The 2018 updated osteoporosis screening recommendations from the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) may seem contradictory to the conclusions of Gourlay and colleagues discussed above. They are not.

The USPSTF authors point out that by 2020, about 12.3 million US individuals older than 50 years are expected to have osteoporosis. Osteoporotic fractures (especially hip fractures) are associated with limitations in ambulation, chronic pain and disability, loss of independence, and decreased quality of life. In fact, 21% to 30% of people who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year. As the US population continues to age, the potential preventable burden will likely increase.

_

Evidence on bone measurement tests, risk assessment tools, and drug therapy efficacy

The USPSTF conducted an evidence review on screening for and treatment of osteoporotic fractures in women as well as risk assessment tools. The task force found the evidence convincing that bone measurement tests are accurate for detecting osteoporosis and predicting osteoporotic fractures. In addition, there is adequate evidence that clinical risk assessment tools are moderately accurate in identifying risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Furthermore, there is convincing evidence that drug therapies reduce subsequent fracture rates in postmenopausal women.

The USPSTF recommends the following:

- For women aged 65 and older, screen for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

- For women younger than 65 who are at increased risk for osteoporosis based on formal clinical risk assessment tools, screen for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

We all agree that women older than 65 years of age should be screened with DXA measurements of bone mass. The USPSTF says that in women under 65, a fracture assessment tool like FRAX, which does not require bone density testing to yield an individual’s absolute 10-year fracture risk, should be used to determine if bone mass measurement by DXA is, in fact, warranted. This recommendation is further supported by the article by Gourlay and colleagues, in which women aged 50 to 64 with subthreshold FRAX scores had a very low risk of fracture prior to age 65.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475.

- Cauley JA, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Incidence of fractures compared to cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1717-1723.

- Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, et al. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302:1573-1579.

- Goldstein SR. Update on osteoporosis. OBG Manag. 2012;24:16-21.

- Goldstein SR. 2017 update on bone health. OBG Manag. 2017;29-32, 48.

As ObGyns, we are the first-line health care providers for our menopausal patients in terms of identifying, preventing, and initiating treatment for women at risk for fragility fractures. Osteoporosis is probably the most important risk factor for bone health, although sarcopenia, frailty, poor eyesight, and falls also play a significant role in bone health and fragility fracture.

In 2005, more than 2 million incident fractures were reported in the United States, with a total cost of $17 billion.1 By 2025, annual fractures and costs are expected to rise by almost 50%. People who are 65 to 74 years of age will likely experience the largest increase in fracture—greater than 87%.1

Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative study showed that the number of women who had a clinical fracture in 1 year exceeded all the cases of myocardial infarction, stroke, and breast cancer combined.2 Furthermore, the morbidity and mortality rates for fractures are staggering. Thirty percent of women with a hip fracture will be dead within 1 year.3 So, although many patients fear developing breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease remains the number 1 cause of death, the impact of maintaining and protecting bone health cannot be emphasized enough.

_

WHI incidental findings: Hormone-treated menopausal women had decreased hip fracture rate

Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al; WHI Investigators. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318:927-938.

Manson and colleagues examined the total and cause-specific cumulative mortality of the 2 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) hormone therapy trials. This was an observational follow-up of US multiethnic postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years (mean age at baseline, 63.4 years) enrolled in 2 randomized clinical trials between 1993 and 1998 and followed up through December 31, 2014. A total of 27,347 women were randomly assigned to treatment.

Treatment groups

Depending on the presence or absence of a uterus, women received conjugated equine estrogens (CEE, 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 2.5 mg/d) (n = 8,506) or placebo (n = 8,102) for a median of 5.6 years or CEE alone (n = 5,310) versus placebo (n = 5,429) for a median of 7.2 years. All-cause mortality (the primary outcome) and cause-specific mortality (cardiovascular disease mortality, cancer mortality, and other major causes of mortality) were analyzed in the 2 trials pooled and in each trial individually.

All-cause and cause-specific mortality findings

Mortality follow-up was available for more than 98% of participants. During the cumulative 18-year follow-up, 7,489 deaths occurred. In the overall pooled cohort, all-cause mortality in the hormone therapy group was 27.1% compared with 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.99 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.94–1.03]). In the CEE plus MPA group, the HR was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.96–1.08). For those in the CEE-alone group, the HR was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88–1.01).

In the pooled cohort for cardiovascular mortality, the HR was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.92–1.08 [8.9% with hormone therapy vs 9.0% with placebo]). For total cancer mortality, the HR was 1.03 (95% CI, 0.95–1.12 [8.2% with hormone therapy vs 8.0% with placebo]). For other causes, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.88–1.02 [10.0% with hormone therapy vs 10.7% with placebo]). Results did not differ significantly between trials.

Key takeaway

The study authors concluded that among postmenopausal women, hormone therapy with CEE plus MPA for a median of 5.6 years or with CEE alone for a median of 7.2 years was not associated with risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, or cancer mortality during a cumulative follow-up of 18 years.

Postmenopausal hormone therapy is arguably the most effective “bone drug” available. While all other antiresorptive agents show hip fracture efficacy only in subgroup analyses of the highest-risk patients (women with established osteoporosis, who often already have pre-existing vertebral fractures), the hormone-treated women in the WHI—who were not chosen for having low bone mass (in fact, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DXA] scores were not even recorded)—still had a statistically significant decrease in hip fracture as an adverse event when compared with placebo-treated women. Increasing data on the long-term safety of hormone therapy in menopausal patients will perhaps encourage its greater use from a bone health perspective.

Continue to: Appropriate to defer DXA testing to age 65...

Appropriate to defer DXA testing to age 65 when baseline FRAX score is below treatment level

Gourlay ML, Overman RA, Fine JP, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Time to clinically relevant fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e15-862.e23.

Gourlay ML, Fine JP, Preisser JS, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:225-233.

Many clinicians used to (and still do) order bone mineral density (BMD) testing at 23-month intervals because that was what insurance would allow. Gourlay and colleagues previously published a study on BMD testing intervals and the time it takes to develop osteoporosis. I covered that information in previous Updates.4,5

To recap, Gourlay and colleagues studied 4,957 women, 67 years of age or older, with normal BMD or osteopenia and with no history of hip or clinical vertebral fracture or of treatment for osteoporosis; the women were followed prospectively for up to 15 years. The estimated time for 10% of women to make the transition to osteoporosis was 16.8 years for those with normal BMD, 4.7 years for those with moderate osteopenia, and 1.1 years for women with advanced osteopenia.

Today, FRAX is recommended to assess need for treatment

Older treatment recommendations involved determining various osteopenic BMD levels and the presence or absence of certain risk factors. More recently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation and many medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have recommended using the FRAX fracture prediction algorithm (available at https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/) instead of T-scores to consider initiating pharmacotherapy.

The FRAX calculation tool uses information such as the country where the patient lives, age, sex, height, weight, history of previous fracture, parental fracture, current smoking, glucocorticoid use, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, alcohol use of 3 or more units per day, and, if available, BMD determination at the femoral neck. It then yields the 10-year absolute risk of hip fracture and any major osteoporotic fracture for that individual or, more precisely, for an individual like that.

In the United States, accepted levels for cost-effective pharmacotherapy are a 10-year absolute risk of hip fracture of 3% or major osteoporotic fracture of 20%.

Continue to: Age also is a key factor in fracture risk assessment

Age also is a key factor in fracture risk assessment

Gourlay and colleagues more recently conducted a retrospective analysis of new occurrence of treatment-level fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women (50 years of age and older) before they received pharmacologic treatment and before they experienced a first hip or clinical vertebral fracture.

In 54,280 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 without a BMD test, the time for 10% to develop a treatment-level FRAX score could not be estimated accurately because of the rarity of treatment-level scores. In 6,096 women who had FRAX scores calculated with their BMD score, the estimated time to treatment-level FRAX was 7.6 years for those 65 to 69 and 5.1 years for 75 to 79 year olds. Furthermore, of 17,967 women aged 50 to 64 with a screening-level FRAX at baseline, only 100 (0.6%) experienced a hip or clinical vertebral fracture by age 65.

The investigators concluded that, “Postmenopausal women with sub-threshold fracture risk scores at baseline were unlikely to develop a treatment-level FRAX score between ages 50 and 64 years. After age 65, the increased incidence of treatment-level fracture risk scores, osteoporosis, and major osteoporotic fracture supports more frequent consideration of FRAX and bone mineral density testing.”

Many health care providers begin BMD testing early in menopause. Bone mass results may motivate patients to initiate healthy lifestyle choices, such as adequate dietary calcium, vitamin D supplementation, exercise, moderate alcohol use, smoking cessation, and fall prevention strategies. However, providers and their patients should be aware that if the fracture risk is beneath the threshold score at baseline, the risk of experiencing an osteoporotic fracture prior to age 65 is extremely low, and this should be taken into account before prescribing pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, as stated, FRAX can be performed without a DXA score. When the result is beneath a treatment level in a woman under 65, DXA testing may be deferred until age 65.

Continue to: USPSTF offers updated recommendations for osteoporosis screening

USPSTF offers updated recommendations for osteoporosis screening

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:2521-2531.

The 2018 updated osteoporosis screening recommendations from the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) may seem contradictory to the conclusions of Gourlay and colleagues discussed above. They are not.

The USPSTF authors point out that by 2020, about 12.3 million US individuals older than 50 years are expected to have osteoporosis. Osteoporotic fractures (especially hip fractures) are associated with limitations in ambulation, chronic pain and disability, loss of independence, and decreased quality of life. In fact, 21% to 30% of people who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year. As the US population continues to age, the potential preventable burden will likely increase.

_

Evidence on bone measurement tests, risk assessment tools, and drug therapy efficacy

The USPSTF conducted an evidence review on screening for and treatment of osteoporotic fractures in women as well as risk assessment tools. The task force found the evidence convincing that bone measurement tests are accurate for detecting osteoporosis and predicting osteoporotic fractures. In addition, there is adequate evidence that clinical risk assessment tools are moderately accurate in identifying risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Furthermore, there is convincing evidence that drug therapies reduce subsequent fracture rates in postmenopausal women.

The USPSTF recommends the following:

- For women aged 65 and older, screen for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

- For women younger than 65 who are at increased risk for osteoporosis based on formal clinical risk assessment tools, screen for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

We all agree that women older than 65 years of age should be screened with DXA measurements of bone mass. The USPSTF says that in women under 65, a fracture assessment tool like FRAX, which does not require bone density testing to yield an individual’s absolute 10-year fracture risk, should be used to determine if bone mass measurement by DXA is, in fact, warranted. This recommendation is further supported by the article by Gourlay and colleagues, in which women aged 50 to 64 with subthreshold FRAX scores had a very low risk of fracture prior to age 65.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As ObGyns, we are the first-line health care providers for our menopausal patients in terms of identifying, preventing, and initiating treatment for women at risk for fragility fractures. Osteoporosis is probably the most important risk factor for bone health, although sarcopenia, frailty, poor eyesight, and falls also play a significant role in bone health and fragility fracture.

In 2005, more than 2 million incident fractures were reported in the United States, with a total cost of $17 billion.1 By 2025, annual fractures and costs are expected to rise by almost 50%. People who are 65 to 74 years of age will likely experience the largest increase in fracture—greater than 87%.1

Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative study showed that the number of women who had a clinical fracture in 1 year exceeded all the cases of myocardial infarction, stroke, and breast cancer combined.2 Furthermore, the morbidity and mortality rates for fractures are staggering. Thirty percent of women with a hip fracture will be dead within 1 year.3 So, although many patients fear developing breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease remains the number 1 cause of death, the impact of maintaining and protecting bone health cannot be emphasized enough.

_

WHI incidental findings: Hormone-treated menopausal women had decreased hip fracture rate

Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al; WHI Investigators. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318:927-938.

Manson and colleagues examined the total and cause-specific cumulative mortality of the 2 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) hormone therapy trials. This was an observational follow-up of US multiethnic postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years (mean age at baseline, 63.4 years) enrolled in 2 randomized clinical trials between 1993 and 1998 and followed up through December 31, 2014. A total of 27,347 women were randomly assigned to treatment.

Treatment groups

Depending on the presence or absence of a uterus, women received conjugated equine estrogens (CEE, 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 2.5 mg/d) (n = 8,506) or placebo (n = 8,102) for a median of 5.6 years or CEE alone (n = 5,310) versus placebo (n = 5,429) for a median of 7.2 years. All-cause mortality (the primary outcome) and cause-specific mortality (cardiovascular disease mortality, cancer mortality, and other major causes of mortality) were analyzed in the 2 trials pooled and in each trial individually.

All-cause and cause-specific mortality findings

Mortality follow-up was available for more than 98% of participants. During the cumulative 18-year follow-up, 7,489 deaths occurred. In the overall pooled cohort, all-cause mortality in the hormone therapy group was 27.1% compared with 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.99 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.94–1.03]). In the CEE plus MPA group, the HR was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.96–1.08). For those in the CEE-alone group, the HR was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88–1.01).

In the pooled cohort for cardiovascular mortality, the HR was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.92–1.08 [8.9% with hormone therapy vs 9.0% with placebo]). For total cancer mortality, the HR was 1.03 (95% CI, 0.95–1.12 [8.2% with hormone therapy vs 8.0% with placebo]). For other causes, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.88–1.02 [10.0% with hormone therapy vs 10.7% with placebo]). Results did not differ significantly between trials.

Key takeaway

The study authors concluded that among postmenopausal women, hormone therapy with CEE plus MPA for a median of 5.6 years or with CEE alone for a median of 7.2 years was not associated with risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, or cancer mortality during a cumulative follow-up of 18 years.

Postmenopausal hormone therapy is arguably the most effective “bone drug” available. While all other antiresorptive agents show hip fracture efficacy only in subgroup analyses of the highest-risk patients (women with established osteoporosis, who often already have pre-existing vertebral fractures), the hormone-treated women in the WHI—who were not chosen for having low bone mass (in fact, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DXA] scores were not even recorded)—still had a statistically significant decrease in hip fracture as an adverse event when compared with placebo-treated women. Increasing data on the long-term safety of hormone therapy in menopausal patients will perhaps encourage its greater use from a bone health perspective.

Continue to: Appropriate to defer DXA testing to age 65...

Appropriate to defer DXA testing to age 65 when baseline FRAX score is below treatment level

Gourlay ML, Overman RA, Fine JP, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Time to clinically relevant fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e15-862.e23.

Gourlay ML, Fine JP, Preisser JS, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:225-233.

Many clinicians used to (and still do) order bone mineral density (BMD) testing at 23-month intervals because that was what insurance would allow. Gourlay and colleagues previously published a study on BMD testing intervals and the time it takes to develop osteoporosis. I covered that information in previous Updates.4,5

To recap, Gourlay and colleagues studied 4,957 women, 67 years of age or older, with normal BMD or osteopenia and with no history of hip or clinical vertebral fracture or of treatment for osteoporosis; the women were followed prospectively for up to 15 years. The estimated time for 10% of women to make the transition to osteoporosis was 16.8 years for those with normal BMD, 4.7 years for those with moderate osteopenia, and 1.1 years for women with advanced osteopenia.

Today, FRAX is recommended to assess need for treatment

Older treatment recommendations involved determining various osteopenic BMD levels and the presence or absence of certain risk factors. More recently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation and many medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have recommended using the FRAX fracture prediction algorithm (available at https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/) instead of T-scores to consider initiating pharmacotherapy.

The FRAX calculation tool uses information such as the country where the patient lives, age, sex, height, weight, history of previous fracture, parental fracture, current smoking, glucocorticoid use, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, alcohol use of 3 or more units per day, and, if available, BMD determination at the femoral neck. It then yields the 10-year absolute risk of hip fracture and any major osteoporotic fracture for that individual or, more precisely, for an individual like that.

In the United States, accepted levels for cost-effective pharmacotherapy are a 10-year absolute risk of hip fracture of 3% or major osteoporotic fracture of 20%.

Continue to: Age also is a key factor in fracture risk assessment

Age also is a key factor in fracture risk assessment

Gourlay and colleagues more recently conducted a retrospective analysis of new occurrence of treatment-level fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women (50 years of age and older) before they received pharmacologic treatment and before they experienced a first hip or clinical vertebral fracture.

In 54,280 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 without a BMD test, the time for 10% to develop a treatment-level FRAX score could not be estimated accurately because of the rarity of treatment-level scores. In 6,096 women who had FRAX scores calculated with their BMD score, the estimated time to treatment-level FRAX was 7.6 years for those 65 to 69 and 5.1 years for 75 to 79 year olds. Furthermore, of 17,967 women aged 50 to 64 with a screening-level FRAX at baseline, only 100 (0.6%) experienced a hip or clinical vertebral fracture by age 65.

The investigators concluded that, “Postmenopausal women with sub-threshold fracture risk scores at baseline were unlikely to develop a treatment-level FRAX score between ages 50 and 64 years. After age 65, the increased incidence of treatment-level fracture risk scores, osteoporosis, and major osteoporotic fracture supports more frequent consideration of FRAX and bone mineral density testing.”

Many health care providers begin BMD testing early in menopause. Bone mass results may motivate patients to initiate healthy lifestyle choices, such as adequate dietary calcium, vitamin D supplementation, exercise, moderate alcohol use, smoking cessation, and fall prevention strategies. However, providers and their patients should be aware that if the fracture risk is beneath the threshold score at baseline, the risk of experiencing an osteoporotic fracture prior to age 65 is extremely low, and this should be taken into account before prescribing pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, as stated, FRAX can be performed without a DXA score. When the result is beneath a treatment level in a woman under 65, DXA testing may be deferred until age 65.

Continue to: USPSTF offers updated recommendations for osteoporosis screening

USPSTF offers updated recommendations for osteoporosis screening

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:2521-2531.

The 2018 updated osteoporosis screening recommendations from the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) may seem contradictory to the conclusions of Gourlay and colleagues discussed above. They are not.

The USPSTF authors point out that by 2020, about 12.3 million US individuals older than 50 years are expected to have osteoporosis. Osteoporotic fractures (especially hip fractures) are associated with limitations in ambulation, chronic pain and disability, loss of independence, and decreased quality of life. In fact, 21% to 30% of people who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year. As the US population continues to age, the potential preventable burden will likely increase.

_

Evidence on bone measurement tests, risk assessment tools, and drug therapy efficacy

The USPSTF conducted an evidence review on screening for and treatment of osteoporotic fractures in women as well as risk assessment tools. The task force found the evidence convincing that bone measurement tests are accurate for detecting osteoporosis and predicting osteoporotic fractures. In addition, there is adequate evidence that clinical risk assessment tools are moderately accurate in identifying risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Furthermore, there is convincing evidence that drug therapies reduce subsequent fracture rates in postmenopausal women.

The USPSTF recommends the following:

- For women aged 65 and older, screen for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

- For women younger than 65 who are at increased risk for osteoporosis based on formal clinical risk assessment tools, screen for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

We all agree that women older than 65 years of age should be screened with DXA measurements of bone mass. The USPSTF says that in women under 65, a fracture assessment tool like FRAX, which does not require bone density testing to yield an individual’s absolute 10-year fracture risk, should be used to determine if bone mass measurement by DXA is, in fact, warranted. This recommendation is further supported by the article by Gourlay and colleagues, in which women aged 50 to 64 with subthreshold FRAX scores had a very low risk of fracture prior to age 65.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475.

- Cauley JA, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Incidence of fractures compared to cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1717-1723.

- Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, et al. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302:1573-1579.

- Goldstein SR. Update on osteoporosis. OBG Manag. 2012;24:16-21.

- Goldstein SR. 2017 update on bone health. OBG Manag. 2017;29-32, 48.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475.

- Cauley JA, Wampler NS, Barnhart JM, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Incidence of fractures compared to cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1717-1723.

- Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, et al. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302:1573-1579.

- Goldstein SR. Update on osteoporosis. OBG Manag. 2012;24:16-21.

- Goldstein SR. 2017 update on bone health. OBG Manag. 2017;29-32, 48.

Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

Women who have a healthier lifestyle during the menopausal transition could significantly reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease, new research suggests.

Because women experience a steeper increase in CVD risk during and after the menopausal transition, researchers analyzed data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women aged 42-52 years. The report is in JAHA: Journal of the American Heart Association.

The analysis revealed that women with the highest average Healthy Lifestyle Score – a composite score of dietary quality, levels of physical activity, and smoking – over 10 years of follow-up had a 0.024-mm smaller common carotid artery intima-media thickness and 0.16-mm smaller adventitial diameter, compared to those with the lowest average score. This was after adjustment for confounders and physiological risk factors such as ethnicity, age, menopausal status, body mass index, and cholesterol levels.

“Smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity are three well-known modifiable behavioral risk factors for CVD,” wrote Dongqing Wang of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors. “Even after adjusting for the lifestyle-related physiological risk factors, the adherence to a healthy lifestyle composed of abstinence from smoking, healthy diet, and regular engagement in physical activity is inversely associated with atherosclerosis in midlife women.”

Women with higher average health lifestyle score also had lower levels of carotid plaque after adjustment for confounding factors, but this was no longer significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors.

The authors analyzed the three components of the healthy lifestyle score separately, and found that not smoking was strongly and significantly associated with lower scores for all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. Women who never smoked across the duration of the study had a 49% lower odds of having a high carotid plaque index compared with women who smoked at some point during the follow-up period.

The analysis showed an inverse association between average Alternate Healthy Eating Index score – a measure of diet quality – and smaller common carotid artery adventitial diameter, although after adjustment for BMI this association was no longer statistically significant. Likewise, the association between dietary quality and intima-media thickness was only marginally significant and lost that significance after adjustment for BMI.

Long-term physical activity was only marginally significantly associated with common carotid artery intima-media thickness, but this was not significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors. No association was found between physical activity and common carotid artery adventitial diameter or carotid plaque.

The authors said that 1.7% of the study population managed to stay in the top category for all three components of healthy lifestyle at all three follow-up time points in the study.

“The low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle in midlife women highlights the potential for lifestyle interventions aimed at this vulnerable population,” they wrote.

In particular, they highlighted abstinence from smoking as having the strongest impact on all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, which is known to affect women more than men. However, the outcomes from diet and physical activity weren’t so strong: The authors suggested that BMI could partly mediate the effects of healthier diet and greater levels of physical activity.

One strength of the study was its ethnically diverse population, which included African American, Chinese, and Hispanic women in addition to non-Hispanic white women. However, the study was not powered to examine the impacts ethnicity may have had on outcomes, the researchers wrote.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

Women who have a healthier lifestyle during the menopausal transition could significantly reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease, new research suggests.

Because women experience a steeper increase in CVD risk during and after the menopausal transition, researchers analyzed data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women aged 42-52 years. The report is in JAHA: Journal of the American Heart Association.

The analysis revealed that women with the highest average Healthy Lifestyle Score – a composite score of dietary quality, levels of physical activity, and smoking – over 10 years of follow-up had a 0.024-mm smaller common carotid artery intima-media thickness and 0.16-mm smaller adventitial diameter, compared to those with the lowest average score. This was after adjustment for confounders and physiological risk factors such as ethnicity, age, menopausal status, body mass index, and cholesterol levels.

“Smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity are three well-known modifiable behavioral risk factors for CVD,” wrote Dongqing Wang of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors. “Even after adjusting for the lifestyle-related physiological risk factors, the adherence to a healthy lifestyle composed of abstinence from smoking, healthy diet, and regular engagement in physical activity is inversely associated with atherosclerosis in midlife women.”

Women with higher average health lifestyle score also had lower levels of carotid plaque after adjustment for confounding factors, but this was no longer significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors.

The authors analyzed the three components of the healthy lifestyle score separately, and found that not smoking was strongly and significantly associated with lower scores for all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. Women who never smoked across the duration of the study had a 49% lower odds of having a high carotid plaque index compared with women who smoked at some point during the follow-up period.

The analysis showed an inverse association between average Alternate Healthy Eating Index score – a measure of diet quality – and smaller common carotid artery adventitial diameter, although after adjustment for BMI this association was no longer statistically significant. Likewise, the association between dietary quality and intima-media thickness was only marginally significant and lost that significance after adjustment for BMI.

Long-term physical activity was only marginally significantly associated with common carotid artery intima-media thickness, but this was not significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors. No association was found between physical activity and common carotid artery adventitial diameter or carotid plaque.

The authors said that 1.7% of the study population managed to stay in the top category for all three components of healthy lifestyle at all three follow-up time points in the study.

“The low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle in midlife women highlights the potential for lifestyle interventions aimed at this vulnerable population,” they wrote.

In particular, they highlighted abstinence from smoking as having the strongest impact on all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, which is known to affect women more than men. However, the outcomes from diet and physical activity weren’t so strong: The authors suggested that BMI could partly mediate the effects of healthier diet and greater levels of physical activity.

One strength of the study was its ethnically diverse population, which included African American, Chinese, and Hispanic women in addition to non-Hispanic white women. However, the study was not powered to examine the impacts ethnicity may have had on outcomes, the researchers wrote.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

Women who have a healthier lifestyle during the menopausal transition could significantly reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease, new research suggests.

Because women experience a steeper increase in CVD risk during and after the menopausal transition, researchers analyzed data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women aged 42-52 years. The report is in JAHA: Journal of the American Heart Association.

The analysis revealed that women with the highest average Healthy Lifestyle Score – a composite score of dietary quality, levels of physical activity, and smoking – over 10 years of follow-up had a 0.024-mm smaller common carotid artery intima-media thickness and 0.16-mm smaller adventitial diameter, compared to those with the lowest average score. This was after adjustment for confounders and physiological risk factors such as ethnicity, age, menopausal status, body mass index, and cholesterol levels.

“Smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity are three well-known modifiable behavioral risk factors for CVD,” wrote Dongqing Wang of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors. “Even after adjusting for the lifestyle-related physiological risk factors, the adherence to a healthy lifestyle composed of abstinence from smoking, healthy diet, and regular engagement in physical activity is inversely associated with atherosclerosis in midlife women.”

Women with higher average health lifestyle score also had lower levels of carotid plaque after adjustment for confounding factors, but this was no longer significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors.

The authors analyzed the three components of the healthy lifestyle score separately, and found that not smoking was strongly and significantly associated with lower scores for all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. Women who never smoked across the duration of the study had a 49% lower odds of having a high carotid plaque index compared with women who smoked at some point during the follow-up period.

The analysis showed an inverse association between average Alternate Healthy Eating Index score – a measure of diet quality – and smaller common carotid artery adventitial diameter, although after adjustment for BMI this association was no longer statistically significant. Likewise, the association between dietary quality and intima-media thickness was only marginally significant and lost that significance after adjustment for BMI.

Long-term physical activity was only marginally significantly associated with common carotid artery intima-media thickness, but this was not significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors. No association was found between physical activity and common carotid artery adventitial diameter or carotid plaque.

The authors said that 1.7% of the study population managed to stay in the top category for all three components of healthy lifestyle at all three follow-up time points in the study.

“The low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle in midlife women highlights the potential for lifestyle interventions aimed at this vulnerable population,” they wrote.

In particular, they highlighted abstinence from smoking as having the strongest impact on all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, which is known to affect women more than men. However, the outcomes from diet and physical activity weren’t so strong: The authors suggested that BMI could partly mediate the effects of healthier diet and greater levels of physical activity.

One strength of the study was its ethnically diverse population, which included African American, Chinese, and Hispanic women in addition to non-Hispanic white women. However, the study was not powered to examine the impacts ethnicity may have had on outcomes, the researchers wrote.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

FROM JAHA: JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: Following a healthier diet and not smoking were significantly linked with lower subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in menopausal women.

Study details: A prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women.

Disclosures: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

Intimate partner violence and PTSD increase menopausal symptom risk

Intimate partner violence or sexual assault may have a significant effect on menopausal symptoms in women, according to a cohort study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 2,016 women aged 40 years or older who were enrolled in the observational Reproductive Risks of Incontinence Study; 40% were non-Latina white, 21% were black, 20% were Latina or Hispanic, and 19% were Asian. Of this cohort, 21% had experienced emotional intimate partner violence (IPV) – 64 (3.2%) in the past 12 months – 16% had experienced physical IPV, 14% had experienced both, and 19% reported sexual assault. More than one in five women (23%) met the criteria for clinically significant PTSD.

Women who had experienced emotional domestic abuse were 36% more likely to report difficulty sleeping, 50% more like to experience night sweats, and 60% more likely to experience pain with intercourse, compared with women who had not experienced any abuse.

Physical abuse was associated with 33% higher odds of night sweats, and sexual assault was associated with 41% higher odds of vaginal dryness, 42% higher odds of vaginal irritation, and 44% higher odds of pain with intercourse.

Women with clinically significant PTSD symptoms were significantly more likely to experience all the symptoms of menopause, including twofold higher odds of pain with intercourse and threefold higher odds of difficulty sleeping. When authors accounted for the effect of PTSD symptoms in the cohort, they found that only the association between emotional abuse and night sweats or pain with intercourse, and between sexual assault and vaginal dryness, remained independently significant.

Carolyn J. Gibson, PhD, MPH, of the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and coauthors said that the biological and hormonal changes that underpin menopausal symptoms, as well as health risk behaviors, cardiometabolic risk factors, and other chronic health conditions associated with menopause, all are impacted by trauma and its psychological effects.

“Chronic hyperarousal and hypervigilance, common in individuals who have experienced trauma and characteristic symptoms of PTSD, may affect sleep and symptom sensitivity,” they wrote.

The reverse is also true; that the symptoms of menopause can impact the symptoms of PTSD by affecting a woman’s sense of self-efficacy, interpersonal engagements, and heighten the stress associated with this period of transition.

“The clinical management of menopause symptoms may also be enhanced by trauma-informed care, including recognition of challenges that may impair efforts to address menopause-related concerns among women affected by trauma,” the authors wrote.

Clinicians also could help by providing education about the link between trauma and health, providing their patients with a safe and supportive treatment environment, and facilitating referrals for psychological or trauma-specific services when needed, they said.

The research was supported by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and funded by the University of California San Francisco–Kaiser Permanente Grants Program for Delivery Science, the Office of Research on Women’s Health Specialized Center of Research, and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

SOURCE: Gibson C et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5233.

An estimated 33% of women in the United States have been sexually assaulted, and an estimated 25% have experienced IPV, so be aware of how common this “wicked problem” is, the way it impacts health, and what role you can play in educating and helping patients by connecting them to available resources.

But that is not enough. Consider measures such as training yourself and staff in how to assess for IPV and sexual assault and use of EHR to integrate IPV assessment into routine clinical care, as well as developing protocols to be followed when a patient discloses IPV or sexual assault. A multidisciplinary approach also can help, including victim service advocates and behavioral health clinicians to provide care and support.

State requirements for reporting partner and sexual violence differ, so be aware of your state laws.

A strength of this study is that it included emotional as well as physical IPV, which often is left out although it has serious impacts.

Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, is from the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, is from the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5242). Dr. Thurston declared research support from the National Institutes of Health and consultancies for Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and MAS Innovations.

An estimated 33% of women in the United States have been sexually assaulted, and an estimated 25% have experienced IPV, so be aware of how common this “wicked problem” is, the way it impacts health, and what role you can play in educating and helping patients by connecting them to available resources.

But that is not enough. Consider measures such as training yourself and staff in how to assess for IPV and sexual assault and use of EHR to integrate IPV assessment into routine clinical care, as well as developing protocols to be followed when a patient discloses IPV or sexual assault. A multidisciplinary approach also can help, including victim service advocates and behavioral health clinicians to provide care and support.

State requirements for reporting partner and sexual violence differ, so be aware of your state laws.

A strength of this study is that it included emotional as well as physical IPV, which often is left out although it has serious impacts.

Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, is from the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, is from the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5242). Dr. Thurston declared research support from the National Institutes of Health and consultancies for Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and MAS Innovations.

An estimated 33% of women in the United States have been sexually assaulted, and an estimated 25% have experienced IPV, so be aware of how common this “wicked problem” is, the way it impacts health, and what role you can play in educating and helping patients by connecting them to available resources.

But that is not enough. Consider measures such as training yourself and staff in how to assess for IPV and sexual assault and use of EHR to integrate IPV assessment into routine clinical care, as well as developing protocols to be followed when a patient discloses IPV or sexual assault. A multidisciplinary approach also can help, including victim service advocates and behavioral health clinicians to provide care and support.

State requirements for reporting partner and sexual violence differ, so be aware of your state laws.

A strength of this study is that it included emotional as well as physical IPV, which often is left out although it has serious impacts.

Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, is from the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, is from the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5242). Dr. Thurston declared research support from the National Institutes of Health and consultancies for Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and MAS Innovations.

Intimate partner violence or sexual assault may have a significant effect on menopausal symptoms in women, according to a cohort study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 2,016 women aged 40 years or older who were enrolled in the observational Reproductive Risks of Incontinence Study; 40% were non-Latina white, 21% were black, 20% were Latina or Hispanic, and 19% were Asian. Of this cohort, 21% had experienced emotional intimate partner violence (IPV) – 64 (3.2%) in the past 12 months – 16% had experienced physical IPV, 14% had experienced both, and 19% reported sexual assault. More than one in five women (23%) met the criteria for clinically significant PTSD.

Women who had experienced emotional domestic abuse were 36% more likely to report difficulty sleeping, 50% more like to experience night sweats, and 60% more likely to experience pain with intercourse, compared with women who had not experienced any abuse.

Physical abuse was associated with 33% higher odds of night sweats, and sexual assault was associated with 41% higher odds of vaginal dryness, 42% higher odds of vaginal irritation, and 44% higher odds of pain with intercourse.

Women with clinically significant PTSD symptoms were significantly more likely to experience all the symptoms of menopause, including twofold higher odds of pain with intercourse and threefold higher odds of difficulty sleeping. When authors accounted for the effect of PTSD symptoms in the cohort, they found that only the association between emotional abuse and night sweats or pain with intercourse, and between sexual assault and vaginal dryness, remained independently significant.

Carolyn J. Gibson, PhD, MPH, of the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and coauthors said that the biological and hormonal changes that underpin menopausal symptoms, as well as health risk behaviors, cardiometabolic risk factors, and other chronic health conditions associated with menopause, all are impacted by trauma and its psychological effects.

“Chronic hyperarousal and hypervigilance, common in individuals who have experienced trauma and characteristic symptoms of PTSD, may affect sleep and symptom sensitivity,” they wrote.

The reverse is also true; that the symptoms of menopause can impact the symptoms of PTSD by affecting a woman’s sense of self-efficacy, interpersonal engagements, and heighten the stress associated with this period of transition.

“The clinical management of menopause symptoms may also be enhanced by trauma-informed care, including recognition of challenges that may impair efforts to address menopause-related concerns among women affected by trauma,” the authors wrote.

Clinicians also could help by providing education about the link between trauma and health, providing their patients with a safe and supportive treatment environment, and facilitating referrals for psychological or trauma-specific services when needed, they said.

The research was supported by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and funded by the University of California San Francisco–Kaiser Permanente Grants Program for Delivery Science, the Office of Research on Women’s Health Specialized Center of Research, and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

SOURCE: Gibson C et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5233.

Intimate partner violence or sexual assault may have a significant effect on menopausal symptoms in women, according to a cohort study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 2,016 women aged 40 years or older who were enrolled in the observational Reproductive Risks of Incontinence Study; 40% were non-Latina white, 21% were black, 20% were Latina or Hispanic, and 19% were Asian. Of this cohort, 21% had experienced emotional intimate partner violence (IPV) – 64 (3.2%) in the past 12 months – 16% had experienced physical IPV, 14% had experienced both, and 19% reported sexual assault. More than one in five women (23%) met the criteria for clinically significant PTSD.

Women who had experienced emotional domestic abuse were 36% more likely to report difficulty sleeping, 50% more like to experience night sweats, and 60% more likely to experience pain with intercourse, compared with women who had not experienced any abuse.

Physical abuse was associated with 33% higher odds of night sweats, and sexual assault was associated with 41% higher odds of vaginal dryness, 42% higher odds of vaginal irritation, and 44% higher odds of pain with intercourse.

Women with clinically significant PTSD symptoms were significantly more likely to experience all the symptoms of menopause, including twofold higher odds of pain with intercourse and threefold higher odds of difficulty sleeping. When authors accounted for the effect of PTSD symptoms in the cohort, they found that only the association between emotional abuse and night sweats or pain with intercourse, and between sexual assault and vaginal dryness, remained independently significant.

Carolyn J. Gibson, PhD, MPH, of the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and coauthors said that the biological and hormonal changes that underpin menopausal symptoms, as well as health risk behaviors, cardiometabolic risk factors, and other chronic health conditions associated with menopause, all are impacted by trauma and its psychological effects.

“Chronic hyperarousal and hypervigilance, common in individuals who have experienced trauma and characteristic symptoms of PTSD, may affect sleep and symptom sensitivity,” they wrote.

The reverse is also true; that the symptoms of menopause can impact the symptoms of PTSD by affecting a woman’s sense of self-efficacy, interpersonal engagements, and heighten the stress associated with this period of transition.

“The clinical management of menopause symptoms may also be enhanced by trauma-informed care, including recognition of challenges that may impair efforts to address menopause-related concerns among women affected by trauma,” the authors wrote.

Clinicians also could help by providing education about the link between trauma and health, providing their patients with a safe and supportive treatment environment, and facilitating referrals for psychological or trauma-specific services when needed, they said.

The research was supported by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and funded by the University of California San Francisco–Kaiser Permanente Grants Program for Delivery Science, the Office of Research on Women’s Health Specialized Center of Research, and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

SOURCE: Gibson C et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5233.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Intimate partner violence increases the risk of menopausal symptoms.

Major finding:

Study details: A cohort study in 2,016 women aged 40 years and older.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and funded by the University of California San Francisco–Kaiser Permanente Grants Program for Delivery Science, the Office of Research on Women’s Health Specialized Center of Research, and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Source: Gibson C et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Nov 19. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5233.

Estetrol safely limited menopause symptoms in a phase 2b study

Estetrol (Donesta) relieved vasomotor menopausal symptoms without stimulating breast tenderness or raising triglyceride levels in a dose-finding study of the investigational drug presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by the fetal liver, is the first native estrogen acting selectively in tissues. Since it crosses the placenta, estetrol is present in maternal urine at about 9 weeks’ gestation. In fetal plasma, it circulates at concentrations about 12 times higher than maternal estetrol levels. The hormone has a half-life of 28-32 hours, longer than the half-life of most other estrogens.

E4 “has been shown to have a remarkably safe profile and I like to describe it as the first natural oral estrogen with the safety profile of a transdermal estrogen,” said Wulf H. Utian, MD, the Arthur H. Bill Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Estetrol uniquely activates nuclear estrogen receptor–alpha, while antagonizing membrane estrogen receptor-alpha. These properties give E4 selective tissue action, with low breast stimulation meaning less breast tenderness and “low carcinogenic impact.”

Additionally, triglyceride levels are minimally affected, and serum markers for venous thromboembolism generally remain unchanged with E4 exposure, he said.

In a phase 2b dose-finding study, a variety of estetrol doses were compared with placebo to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years with at least 7 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, or at least 50 moderate to severe hot flashes in the week before randomization. The multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial took place in five European countries, with 200 women overall completing the study. The study design excluded women with personal histories of malignancy, thromboembolism, or coagulopathy, and women with diabetes and poor glycemic control. Women with a uterus who had current or past endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or an abnormal cervical smear were also excluded.

Women who had an intact uterus were included if transvaginal ultrasound showed endometrial thickness of 5 mm or less. Participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive four different E4 doses: 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg.

At the highest dose of 15 mg, E4 significantly reduced the frequency of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo by study week 4 and throughout the 12-week study period (P less than .05).

This high dose also resulted in a 28% reduction in vasomotor symptom severity, compared with placebo by study week 12, with a significant separation from placebo by week 12.

In terms of the number of women who experienced at least a 50% drop in severe vasomotor symptoms, the 15-mg E4 dose also bested placebo (P less than .01). Among the group taking the 15 mg dose, significantly more also saw at least a 75% drop in frequency of severe vasomotor symptom (P less than .001).

Vaginal cytology showed that by week 12 all doses of E4 significantly increased the vaginal maturation index from baseline, a finding that corresponds with less thinning of vaginal tissues (P less than .001, compared with placebo for all doses).

The safety profile of E4 was good, Dr. Utian said. Coagulation markers were unaffected, and most lipid and blood glucose markers were also unchanged. There were “small but potentially beneficial changes in HDL-C [HDL cholesterol levels] and HbA1c values [hemoglobin A1c]” in groups taking the two highest doses of E4.

Also, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen and osteocalcin values were reduced, “suggesting reduction in bone resorption,” he said.

According to Dr. Utian, those taking the two highest doses also saw a “slight though significant increase” from baseline in sex hormone–binding globulin levels, “indicating that the E4 estrogenic effect was mild and dose dependent.”

Endometrial biopsies showed no hyperplasia. In those taking the 15-mg E4 dose, mean endometrial thickness did increase from a mean 2 mm at baseline to 6 mm at 12 weeks. However, endometrial thickness returned to baseline after progestin therapy, said Dr. Utian. There were no unexpected adverse events during the study.

Dr. Utian reported consultant relationships with Mithra, the maker of estetrol; AMAG; Pharmavite; and Endoceutics. The study was funded by Mithra.

SOURCE: Utian W. NAMS 2018, Friday concurrent session 1.

Estetrol (Donesta) relieved vasomotor menopausal symptoms without stimulating breast tenderness or raising triglyceride levels in a dose-finding study of the investigational drug presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by the fetal liver, is the first native estrogen acting selectively in tissues. Since it crosses the placenta, estetrol is present in maternal urine at about 9 weeks’ gestation. In fetal plasma, it circulates at concentrations about 12 times higher than maternal estetrol levels. The hormone has a half-life of 28-32 hours, longer than the half-life of most other estrogens.

E4 “has been shown to have a remarkably safe profile and I like to describe it as the first natural oral estrogen with the safety profile of a transdermal estrogen,” said Wulf H. Utian, MD, the Arthur H. Bill Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Estetrol uniquely activates nuclear estrogen receptor–alpha, while antagonizing membrane estrogen receptor-alpha. These properties give E4 selective tissue action, with low breast stimulation meaning less breast tenderness and “low carcinogenic impact.”

Additionally, triglyceride levels are minimally affected, and serum markers for venous thromboembolism generally remain unchanged with E4 exposure, he said.

In a phase 2b dose-finding study, a variety of estetrol doses were compared with placebo to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years with at least 7 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, or at least 50 moderate to severe hot flashes in the week before randomization. The multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial took place in five European countries, with 200 women overall completing the study. The study design excluded women with personal histories of malignancy, thromboembolism, or coagulopathy, and women with diabetes and poor glycemic control. Women with a uterus who had current or past endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or an abnormal cervical smear were also excluded.

Women who had an intact uterus were included if transvaginal ultrasound showed endometrial thickness of 5 mm or less. Participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive four different E4 doses: 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg.

At the highest dose of 15 mg, E4 significantly reduced the frequency of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo by study week 4 and throughout the 12-week study period (P less than .05).

This high dose also resulted in a 28% reduction in vasomotor symptom severity, compared with placebo by study week 12, with a significant separation from placebo by week 12.

In terms of the number of women who experienced at least a 50% drop in severe vasomotor symptoms, the 15-mg E4 dose also bested placebo (P less than .01). Among the group taking the 15 mg dose, significantly more also saw at least a 75% drop in frequency of severe vasomotor symptom (P less than .001).

Vaginal cytology showed that by week 12 all doses of E4 significantly increased the vaginal maturation index from baseline, a finding that corresponds with less thinning of vaginal tissues (P less than .001, compared with placebo for all doses).

The safety profile of E4 was good, Dr. Utian said. Coagulation markers were unaffected, and most lipid and blood glucose markers were also unchanged. There were “small but potentially beneficial changes in HDL-C [HDL cholesterol levels] and HbA1c values [hemoglobin A1c]” in groups taking the two highest doses of E4.

Also, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen and osteocalcin values were reduced, “suggesting reduction in bone resorption,” he said.

According to Dr. Utian, those taking the two highest doses also saw a “slight though significant increase” from baseline in sex hormone–binding globulin levels, “indicating that the E4 estrogenic effect was mild and dose dependent.”

Endometrial biopsies showed no hyperplasia. In those taking the 15-mg E4 dose, mean endometrial thickness did increase from a mean 2 mm at baseline to 6 mm at 12 weeks. However, endometrial thickness returned to baseline after progestin therapy, said Dr. Utian. There were no unexpected adverse events during the study.

Dr. Utian reported consultant relationships with Mithra, the maker of estetrol; AMAG; Pharmavite; and Endoceutics. The study was funded by Mithra.

SOURCE: Utian W. NAMS 2018, Friday concurrent session 1.

Estetrol (Donesta) relieved vasomotor menopausal symptoms without stimulating breast tenderness or raising triglyceride levels in a dose-finding study of the investigational drug presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by the fetal liver, is the first native estrogen acting selectively in tissues. Since it crosses the placenta, estetrol is present in maternal urine at about 9 weeks’ gestation. In fetal plasma, it circulates at concentrations about 12 times higher than maternal estetrol levels. The hormone has a half-life of 28-32 hours, longer than the half-life of most other estrogens.

E4 “has been shown to have a remarkably safe profile and I like to describe it as the first natural oral estrogen with the safety profile of a transdermal estrogen,” said Wulf H. Utian, MD, the Arthur H. Bill Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Estetrol uniquely activates nuclear estrogen receptor–alpha, while antagonizing membrane estrogen receptor-alpha. These properties give E4 selective tissue action, with low breast stimulation meaning less breast tenderness and “low carcinogenic impact.”

Additionally, triglyceride levels are minimally affected, and serum markers for venous thromboembolism generally remain unchanged with E4 exposure, he said.

In a phase 2b dose-finding study, a variety of estetrol doses were compared with placebo to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years with at least 7 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, or at least 50 moderate to severe hot flashes in the week before randomization. The multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial took place in five European countries, with 200 women overall completing the study. The study design excluded women with personal histories of malignancy, thromboembolism, or coagulopathy, and women with diabetes and poor glycemic control. Women with a uterus who had current or past endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or an abnormal cervical smear were also excluded.

Women who had an intact uterus were included if transvaginal ultrasound showed endometrial thickness of 5 mm or less. Participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive four different E4 doses: 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg.

At the highest dose of 15 mg, E4 significantly reduced the frequency of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo by study week 4 and throughout the 12-week study period (P less than .05).

This high dose also resulted in a 28% reduction in vasomotor symptom severity, compared with placebo by study week 12, with a significant separation from placebo by week 12.

In terms of the number of women who experienced at least a 50% drop in severe vasomotor symptoms, the 15-mg E4 dose also bested placebo (P less than .01). Among the group taking the 15 mg dose, significantly more also saw at least a 75% drop in frequency of severe vasomotor symptom (P less than .001).

Vaginal cytology showed that by week 12 all doses of E4 significantly increased the vaginal maturation index from baseline, a finding that corresponds with less thinning of vaginal tissues (P less than .001, compared with placebo for all doses).