User login

MDedge Daily News: Why most heart failure may be preventable

Why most heart failure may be preventable. Statins miss the mark in familial high cholesterol. Why mumps outbreaks are on the rise. And how using epileptic drugs in pregnancy affects school test scores.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Why most heart failure may be preventable. Statins miss the mark in familial high cholesterol. Why mumps outbreaks are on the rise. And how using epileptic drugs in pregnancy affects school test scores.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Why most heart failure may be preventable. Statins miss the mark in familial high cholesterol. Why mumps outbreaks are on the rise. And how using epileptic drugs in pregnancy affects school test scores.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Dr. T. Berry Brazelton was a pioneer of child-centered parenting

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

High-dose oral ibuprofen most effective for PDA closure

compared with other pharmacological treatments, according to results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

However, using placebo or no treatment at all did not increase the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage in the study, published in JAMA.

PDA is a common cardiovascular issue among prematurely born infants. According to Dr. Mitra and his coauthors, it’s thought that a large proportion of PDAs spontaneously close in a few days and have minimal effect on clinical outcomes.

As a result, treatment is often targeted to PDAs deemed hemodynamically significant based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters, the authors wrote, although there is little guidance on what, if any, treatment to use in this situation.

“The dilemma is whether to use pharmacotherapy at all, and if a decision is made to treat the PDA medically, what should be the ideal choice of pharmacotherapy,” they wrote.

Dr. Mitra and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

They found that closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with the two of the most widely used treatments, namely standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and standard-dose intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Despite that finding, there was no significant difference in the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage for use of placebo or no treatment, compared with any of the treatment modalities, the investigators added.

“With increasing emphasis on conservative management of PDA, these results may encourage researchers to revisit placebo-controlled trials against newer pharmacotherapeutic options,” they said.

Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

compared with other pharmacological treatments, according to results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

However, using placebo or no treatment at all did not increase the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage in the study, published in JAMA.

PDA is a common cardiovascular issue among prematurely born infants. According to Dr. Mitra and his coauthors, it’s thought that a large proportion of PDAs spontaneously close in a few days and have minimal effect on clinical outcomes.

As a result, treatment is often targeted to PDAs deemed hemodynamically significant based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters, the authors wrote, although there is little guidance on what, if any, treatment to use in this situation.

“The dilemma is whether to use pharmacotherapy at all, and if a decision is made to treat the PDA medically, what should be the ideal choice of pharmacotherapy,” they wrote.

Dr. Mitra and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

They found that closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with the two of the most widely used treatments, namely standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and standard-dose intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Despite that finding, there was no significant difference in the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage for use of placebo or no treatment, compared with any of the treatment modalities, the investigators added.

“With increasing emphasis on conservative management of PDA, these results may encourage researchers to revisit placebo-controlled trials against newer pharmacotherapeutic options,” they said.

Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

compared with other pharmacological treatments, according to results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

However, using placebo or no treatment at all did not increase the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage in the study, published in JAMA.

PDA is a common cardiovascular issue among prematurely born infants. According to Dr. Mitra and his coauthors, it’s thought that a large proportion of PDAs spontaneously close in a few days and have minimal effect on clinical outcomes.

As a result, treatment is often targeted to PDAs deemed hemodynamically significant based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters, the authors wrote, although there is little guidance on what, if any, treatment to use in this situation.

“The dilemma is whether to use pharmacotherapy at all, and if a decision is made to treat the PDA medically, what should be the ideal choice of pharmacotherapy,” they wrote.

Dr. Mitra and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

They found that closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with the two of the most widely used treatments, namely standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and standard-dose intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Despite that finding, there was no significant difference in the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage for use of placebo or no treatment, compared with any of the treatment modalities, the investigators added.

“With increasing emphasis on conservative management of PDA, these results may encourage researchers to revisit placebo-controlled trials against newer pharmacotherapeutic options,” they said.

Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Compared with other pharmacological treatments, high-dose oral ibuprofen may be most likely to result in closure of hemodynamically significant PDA in preterm infants.

Major finding: Closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

Disclosures: Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

RSV immunoprophylaxis in premature infants doesn’t prevent later asthma

reported Nienke M. Scheltema, MD, of Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands, and associates.

In a study of 395 otherwise healthy premature infants who were randomized to receive palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis or placebo and followed for 6 years, 14% of the 199 infants in the RSV prevention group had parent-reported asthma, compared with 24% of the 196 in the placebo group (absolute risk reduction, 9.9%). This was explained mostly by differences in infrequent wheeze, the researchers said. However, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past 12 months was not significantly different between the two groups at 6 years: 10.3% in the RSV prevention group and 9.9% in the placebo group.

SOURCE: Scheltema NM et al. Lancet. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9.

reported Nienke M. Scheltema, MD, of Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands, and associates.

In a study of 395 otherwise healthy premature infants who were randomized to receive palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis or placebo and followed for 6 years, 14% of the 199 infants in the RSV prevention group had parent-reported asthma, compared with 24% of the 196 in the placebo group (absolute risk reduction, 9.9%). This was explained mostly by differences in infrequent wheeze, the researchers said. However, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past 12 months was not significantly different between the two groups at 6 years: 10.3% in the RSV prevention group and 9.9% in the placebo group.

SOURCE: Scheltema NM et al. Lancet. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9.

reported Nienke M. Scheltema, MD, of Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands, and associates.

In a study of 395 otherwise healthy premature infants who were randomized to receive palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis or placebo and followed for 6 years, 14% of the 199 infants in the RSV prevention group had parent-reported asthma, compared with 24% of the 196 in the placebo group (absolute risk reduction, 9.9%). This was explained mostly by differences in infrequent wheeze, the researchers said. However, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past 12 months was not significantly different between the two groups at 6 years: 10.3% in the RSV prevention group and 9.9% in the placebo group.

SOURCE: Scheltema NM et al. Lancet. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9.

FROM THE LANCET

Interventions urged to stop rising NAS, stem Medicaid costs

The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and the corresponding costs to Medicaid are unlikely to decline unless interventions focus on stopping opioid use by low-income mothers, said Tyler N.A. Winkelman, MD, of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his associates.

Dr. Winkelman and his associates conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis that used 9,115,457 birth discharge records from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which were representative of 43.6 million weighted births. Overall, 3,991,336 infants were covered by Medicaid, which were representative of 19.1 million weighted births. There were 35,629 (0.89%) infants with a diagnosis of NAS, which were representative of 173,384 weighted births. Medicaid was the primary payer for 74% (95% confidence interval, 68.9%-77.9%) of NAS-related births in 2004 and 82% (95% CI, 80.5%-83.5%) of NAS-related births in 2014.

Infants with NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid were significantly more likely to be male, live in a rural county, and have comorbidities reflective of the syndrome than were infants without NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid, the researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

from 1.5 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 1.2-1.9) to 8 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 7.2-8.7), as the opioid epidemic worsened in the country.

Infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid had a greater chance of being transferred to another hospital for care (9% vs. 7%; P = .02) and stay in the hospital longer (17 days vs. 15 days; P less than .001), compared with infants with NAS who were covered by private insurance.

NAS is costly. In the 2011-2014 era, mean hospital costs for a NAS infant covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for an infant without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth; P less than .001). After adjustment for inflation, mean hospital costs for infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid increased 26% between 2004-2006 and 2011-2014 ($15,350 vs. $19,340; P less than .001), the researchers reported. Annual hospital costs, which were adjusted for inflation to 2014 U.S. dollars, for all infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid rose from $65.4 million in 2004 to $462 million in 2014.

“With the disproportionate impact of NAS on the Medicaid population, we suggest that NAS incidence rates are unlikely to improve without interventions targeted at low-income mothers and infants,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates concluded.

Nonpharmacologic interventions are available to help NAS infants. “Systematic implementation of policies that support rooming-in, breastfeeding, swaddling, on-demand feeding schedules, and minimization of sleep disruption may reduce symptoms of NAS and reduce the duration of, or even eliminate the need for, pharmacologic treatment of NAS,” the researchers said. “Pharmacologic treatment with buprenorphine, for example, has been shown to reduce hospital length of stay by 35%.”

Another intervention is medication-assisted treatment during pregnancy, which studies have shown “improves outcomes and reduces costs associated with NAS, compared with attempted abstinence,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates said. It does not necessarily reduce NAS incidence, but “it may prevent prolonged hospital stays due to preterm birth, reduce NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] admissions, decrease the severity of NAS symptoms, and improve birth outcomes for some infants.”

The researchers also endorsed screening, referral, and treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders among reproductive age women, including adolescents, because these are risk factors for opioid abuse.

One author was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and the corresponding costs to Medicaid are unlikely to decline unless interventions focus on stopping opioid use by low-income mothers, said Tyler N.A. Winkelman, MD, of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his associates.

Dr. Winkelman and his associates conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis that used 9,115,457 birth discharge records from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which were representative of 43.6 million weighted births. Overall, 3,991,336 infants were covered by Medicaid, which were representative of 19.1 million weighted births. There were 35,629 (0.89%) infants with a diagnosis of NAS, which were representative of 173,384 weighted births. Medicaid was the primary payer for 74% (95% confidence interval, 68.9%-77.9%) of NAS-related births in 2004 and 82% (95% CI, 80.5%-83.5%) of NAS-related births in 2014.

Infants with NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid were significantly more likely to be male, live in a rural county, and have comorbidities reflective of the syndrome than were infants without NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid, the researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

from 1.5 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 1.2-1.9) to 8 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 7.2-8.7), as the opioid epidemic worsened in the country.

Infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid had a greater chance of being transferred to another hospital for care (9% vs. 7%; P = .02) and stay in the hospital longer (17 days vs. 15 days; P less than .001), compared with infants with NAS who were covered by private insurance.

NAS is costly. In the 2011-2014 era, mean hospital costs for a NAS infant covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for an infant without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth; P less than .001). After adjustment for inflation, mean hospital costs for infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid increased 26% between 2004-2006 and 2011-2014 ($15,350 vs. $19,340; P less than .001), the researchers reported. Annual hospital costs, which were adjusted for inflation to 2014 U.S. dollars, for all infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid rose from $65.4 million in 2004 to $462 million in 2014.

“With the disproportionate impact of NAS on the Medicaid population, we suggest that NAS incidence rates are unlikely to improve without interventions targeted at low-income mothers and infants,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates concluded.

Nonpharmacologic interventions are available to help NAS infants. “Systematic implementation of policies that support rooming-in, breastfeeding, swaddling, on-demand feeding schedules, and minimization of sleep disruption may reduce symptoms of NAS and reduce the duration of, or even eliminate the need for, pharmacologic treatment of NAS,” the researchers said. “Pharmacologic treatment with buprenorphine, for example, has been shown to reduce hospital length of stay by 35%.”

Another intervention is medication-assisted treatment during pregnancy, which studies have shown “improves outcomes and reduces costs associated with NAS, compared with attempted abstinence,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates said. It does not necessarily reduce NAS incidence, but “it may prevent prolonged hospital stays due to preterm birth, reduce NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] admissions, decrease the severity of NAS symptoms, and improve birth outcomes for some infants.”

The researchers also endorsed screening, referral, and treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders among reproductive age women, including adolescents, because these are risk factors for opioid abuse.

One author was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and the corresponding costs to Medicaid are unlikely to decline unless interventions focus on stopping opioid use by low-income mothers, said Tyler N.A. Winkelman, MD, of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his associates.

Dr. Winkelman and his associates conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis that used 9,115,457 birth discharge records from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which were representative of 43.6 million weighted births. Overall, 3,991,336 infants were covered by Medicaid, which were representative of 19.1 million weighted births. There were 35,629 (0.89%) infants with a diagnosis of NAS, which were representative of 173,384 weighted births. Medicaid was the primary payer for 74% (95% confidence interval, 68.9%-77.9%) of NAS-related births in 2004 and 82% (95% CI, 80.5%-83.5%) of NAS-related births in 2014.

Infants with NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid were significantly more likely to be male, live in a rural county, and have comorbidities reflective of the syndrome than were infants without NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid, the researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

from 1.5 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 1.2-1.9) to 8 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 7.2-8.7), as the opioid epidemic worsened in the country.

Infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid had a greater chance of being transferred to another hospital for care (9% vs. 7%; P = .02) and stay in the hospital longer (17 days vs. 15 days; P less than .001), compared with infants with NAS who were covered by private insurance.

NAS is costly. In the 2011-2014 era, mean hospital costs for a NAS infant covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for an infant without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth; P less than .001). After adjustment for inflation, mean hospital costs for infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid increased 26% between 2004-2006 and 2011-2014 ($15,350 vs. $19,340; P less than .001), the researchers reported. Annual hospital costs, which were adjusted for inflation to 2014 U.S. dollars, for all infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid rose from $65.4 million in 2004 to $462 million in 2014.

“With the disproportionate impact of NAS on the Medicaid population, we suggest that NAS incidence rates are unlikely to improve without interventions targeted at low-income mothers and infants,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates concluded.

Nonpharmacologic interventions are available to help NAS infants. “Systematic implementation of policies that support rooming-in, breastfeeding, swaddling, on-demand feeding schedules, and minimization of sleep disruption may reduce symptoms of NAS and reduce the duration of, or even eliminate the need for, pharmacologic treatment of NAS,” the researchers said. “Pharmacologic treatment with buprenorphine, for example, has been shown to reduce hospital length of stay by 35%.”

Another intervention is medication-assisted treatment during pregnancy, which studies have shown “improves outcomes and reduces costs associated with NAS, compared with attempted abstinence,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates said. It does not necessarily reduce NAS incidence, but “it may prevent prolonged hospital stays due to preterm birth, reduce NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] admissions, decrease the severity of NAS symptoms, and improve birth outcomes for some infants.”

The researchers also endorsed screening, referral, and treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders among reproductive age women, including adolescents, because these are risk factors for opioid abuse.

One author was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 2011-2014, mean hospital costs for NAS infants covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for infants without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth).

Study details: A serial cross-sectional analysis that usd data from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) of 9,115,457 birth discharge records.

Disclosures: Stephen W. Patrick, MD, was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

Maternal biologic therapy does not affect infant vaccine responses

MAUI, HAWAII – The infants of inflammatory bowel disease patients on biologic therapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding do not have a diminished response rate to the inactivated vaccines routinely given during the first 6 months of life, Uma Mahadevan, MD, said at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Those babies are going to have detectable levels of drug on board, but they respond to vaccines just as well as infants born to mothers with IBD who were not on biologic therapy. The rates are the same, albeit lower than in the general population,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Previous reports from the national registry have established that continuation of biologics in IBD patients throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain disease control poses no increased risks to the fetus in terms of rates of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or longer-term developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies whose mothers have IBD.

Dr. Ananthakrishnan’s analysis focused on response rates to tetanus and Haemophilus influenzae B vaccines in the infants of 179 PIANO patients. Sixty-five percent of the IBD patients were on various biologic agents during pregnancy, 8% were on a thiopurine, 21% were on combination therapy, and 6% weren’t exposed to any IBD medications. Serologic studies showed that there was no difference across the four groups in terms of infant rates of protective titers in response to the vaccines. However, the 69%-84% rates of protective titers in the four groups fell short of the 90%-plus rate expected in the general population.

Live virus vaccines are contraindicated in the first 6 months of life in infants exposed to maternal biologics in utero. The only live virus vaccine given during that time frame in the United States is rotavirus, administered at months 2 and 3. Dr. Mahadevan and others recommend skipping that vaccine in babies exposed in utero to any IBD biologic other than certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), which uniquely doesn’t cross the placenta.

“That being said, infants born to 71 of our PIANO participants on anti-TNF therapy in pregnancy inadvertently got the rotavirus vaccine, and they were all just fine, even with very high drug levels,” the gastroenterologist said.

The live virus varicella and MMR vaccines can safely be given as scheduled at 1 year of age. By that time the biologics are long gone from the child.

Dr. Mahadevan reported receiving research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, which sponsors the PIANO registry. She also has financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The infants of inflammatory bowel disease patients on biologic therapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding do not have a diminished response rate to the inactivated vaccines routinely given during the first 6 months of life, Uma Mahadevan, MD, said at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Those babies are going to have detectable levels of drug on board, but they respond to vaccines just as well as infants born to mothers with IBD who were not on biologic therapy. The rates are the same, albeit lower than in the general population,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Previous reports from the national registry have established that continuation of biologics in IBD patients throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain disease control poses no increased risks to the fetus in terms of rates of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or longer-term developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies whose mothers have IBD.

Dr. Ananthakrishnan’s analysis focused on response rates to tetanus and Haemophilus influenzae B vaccines in the infants of 179 PIANO patients. Sixty-five percent of the IBD patients were on various biologic agents during pregnancy, 8% were on a thiopurine, 21% were on combination therapy, and 6% weren’t exposed to any IBD medications. Serologic studies showed that there was no difference across the four groups in terms of infant rates of protective titers in response to the vaccines. However, the 69%-84% rates of protective titers in the four groups fell short of the 90%-plus rate expected in the general population.

Live virus vaccines are contraindicated in the first 6 months of life in infants exposed to maternal biologics in utero. The only live virus vaccine given during that time frame in the United States is rotavirus, administered at months 2 and 3. Dr. Mahadevan and others recommend skipping that vaccine in babies exposed in utero to any IBD biologic other than certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), which uniquely doesn’t cross the placenta.

“That being said, infants born to 71 of our PIANO participants on anti-TNF therapy in pregnancy inadvertently got the rotavirus vaccine, and they were all just fine, even with very high drug levels,” the gastroenterologist said.

The live virus varicella and MMR vaccines can safely be given as scheduled at 1 year of age. By that time the biologics are long gone from the child.

Dr. Mahadevan reported receiving research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, which sponsors the PIANO registry. She also has financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The infants of inflammatory bowel disease patients on biologic therapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding do not have a diminished response rate to the inactivated vaccines routinely given during the first 6 months of life, Uma Mahadevan, MD, said at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Those babies are going to have detectable levels of drug on board, but they respond to vaccines just as well as infants born to mothers with IBD who were not on biologic therapy. The rates are the same, albeit lower than in the general population,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Previous reports from the national registry have established that continuation of biologics in IBD patients throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain disease control poses no increased risks to the fetus in terms of rates of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or longer-term developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies whose mothers have IBD.

Dr. Ananthakrishnan’s analysis focused on response rates to tetanus and Haemophilus influenzae B vaccines in the infants of 179 PIANO patients. Sixty-five percent of the IBD patients were on various biologic agents during pregnancy, 8% were on a thiopurine, 21% were on combination therapy, and 6% weren’t exposed to any IBD medications. Serologic studies showed that there was no difference across the four groups in terms of infant rates of protective titers in response to the vaccines. However, the 69%-84% rates of protective titers in the four groups fell short of the 90%-plus rate expected in the general population.

Live virus vaccines are contraindicated in the first 6 months of life in infants exposed to maternal biologics in utero. The only live virus vaccine given during that time frame in the United States is rotavirus, administered at months 2 and 3. Dr. Mahadevan and others recommend skipping that vaccine in babies exposed in utero to any IBD biologic other than certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), which uniquely doesn’t cross the placenta.

“That being said, infants born to 71 of our PIANO participants on anti-TNF therapy in pregnancy inadvertently got the rotavirus vaccine, and they were all just fine, even with very high drug levels,” the gastroenterologist said.

The live virus varicella and MMR vaccines can safely be given as scheduled at 1 year of age. By that time the biologics are long gone from the child.

Dr. Mahadevan reported receiving research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, which sponsors the PIANO registry. She also has financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2018

Alternative oxygen therapy reduces treatment failure in bronchiolitis

High-flow oxygen therapy outside the ICU boosts the likelihood that infants with bronchiolitis will avoid treatment failure and an escalation of treatment, a study finds.

“High flow can be safely used in general emergency wards and general pediatric ward settings in regional and metropolitan hospitals that have no immediate direct access to dedicated pediatric intensive care facilities,” study coauthor Andreas Schibler, MD, of University of Queensland in Australia, said in an interview. The findings were published March 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The typical treatment for bronchiolitis is supportive therapy, providing nutrition, fluids, and if needed respiratory support including provision of oxygen,” Dr. Schibler said.

The prognosis is generally goods thanks to improvements in intensive care, he said, which some infants need because the standard oxygen therapy provided in general pediatric wards is insufficient. The new study examines whether high-flow oxygen therapy through a cannula – which he said has become more common – reduces the risk of treatment failure in non-ICU therapy, compared with standard oxygen treatment.

Dr. Schibler and his colleagues tracked 1,472 patients under 12 months with bronchiolitis and a need for oxygen treatment who were randomly assigned to high-flow or standard oxygen therapy to maintain their oxygen saturation at 92%-98% or 94%-98%, depending on policy at the hospital. The subjects were patients at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

A total of 739 infants received high-flow treatment that provided heated and humidified oxygen at a rate of 2 liters per kilogram of body weight per minute. The other 733 infants received standard oxygen therapy up to a maximum 2 liters per minute.

The treatment failed, requiring an escalation of care, in 87 of 739 patients (12%) in the high-flow group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group. (risk difference = –11% points; 95% confidence interval, –15 to –7; P less than .001).

“The ease to use and simplicity of high flow made us recognize and think that this level of respiratory care can be provided outside intensive care,” Dr. Schibler said. “This was further supported by the observational fact that most of these infants with bronchiolitis showed a dramatically improved respiratory condition once on high flow.”

Dr. Schibler said there haven’t been any signs of adverse effects from high-flow oxygen therapy. As for the cost of the treatment, he said it is “likely offset by a reduced need for intensive care therapy or costs associated with transferring to a children’s hospital.”

What should physicians and hospitals take from the study findings? “If a hospital explores the option to use high flow in bronchiolitis, then start the therapy early in the disease process or once an oxygen requirement is recognized,” Dr. Schibler said. “Implementation of a solid and structured training program with a clear hospital guideline based on the evidence will ensure the staff who care for these patients will be empowered and comfortable to adjust the oxygen levels given by the high-flow equipment. The greater the confidence and comfort level for the nursing and respiratory technician staff the better for these infants, as they will sooner observe those infants who are not responding well and may require a higher level of care such as intensive care or they will recognize the infant who responds well.”

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment and consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

SOURCE: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1112-31.

High-flow oxygen therapy outside the ICU boosts the likelihood that infants with bronchiolitis will avoid treatment failure and an escalation of treatment, a study finds.

“High flow can be safely used in general emergency wards and general pediatric ward settings in regional and metropolitan hospitals that have no immediate direct access to dedicated pediatric intensive care facilities,” study coauthor Andreas Schibler, MD, of University of Queensland in Australia, said in an interview. The findings were published March 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The typical treatment for bronchiolitis is supportive therapy, providing nutrition, fluids, and if needed respiratory support including provision of oxygen,” Dr. Schibler said.

The prognosis is generally goods thanks to improvements in intensive care, he said, which some infants need because the standard oxygen therapy provided in general pediatric wards is insufficient. The new study examines whether high-flow oxygen therapy through a cannula – which he said has become more common – reduces the risk of treatment failure in non-ICU therapy, compared with standard oxygen treatment.

Dr. Schibler and his colleagues tracked 1,472 patients under 12 months with bronchiolitis and a need for oxygen treatment who were randomly assigned to high-flow or standard oxygen therapy to maintain their oxygen saturation at 92%-98% or 94%-98%, depending on policy at the hospital. The subjects were patients at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

A total of 739 infants received high-flow treatment that provided heated and humidified oxygen at a rate of 2 liters per kilogram of body weight per minute. The other 733 infants received standard oxygen therapy up to a maximum 2 liters per minute.

The treatment failed, requiring an escalation of care, in 87 of 739 patients (12%) in the high-flow group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group. (risk difference = –11% points; 95% confidence interval, –15 to –7; P less than .001).

“The ease to use and simplicity of high flow made us recognize and think that this level of respiratory care can be provided outside intensive care,” Dr. Schibler said. “This was further supported by the observational fact that most of these infants with bronchiolitis showed a dramatically improved respiratory condition once on high flow.”

Dr. Schibler said there haven’t been any signs of adverse effects from high-flow oxygen therapy. As for the cost of the treatment, he said it is “likely offset by a reduced need for intensive care therapy or costs associated with transferring to a children’s hospital.”

What should physicians and hospitals take from the study findings? “If a hospital explores the option to use high flow in bronchiolitis, then start the therapy early in the disease process or once an oxygen requirement is recognized,” Dr. Schibler said. “Implementation of a solid and structured training program with a clear hospital guideline based on the evidence will ensure the staff who care for these patients will be empowered and comfortable to adjust the oxygen levels given by the high-flow equipment. The greater the confidence and comfort level for the nursing and respiratory technician staff the better for these infants, as they will sooner observe those infants who are not responding well and may require a higher level of care such as intensive care or they will recognize the infant who responds well.”

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment and consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

SOURCE: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1112-31.

High-flow oxygen therapy outside the ICU boosts the likelihood that infants with bronchiolitis will avoid treatment failure and an escalation of treatment, a study finds.

“High flow can be safely used in general emergency wards and general pediatric ward settings in regional and metropolitan hospitals that have no immediate direct access to dedicated pediatric intensive care facilities,” study coauthor Andreas Schibler, MD, of University of Queensland in Australia, said in an interview. The findings were published March 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The typical treatment for bronchiolitis is supportive therapy, providing nutrition, fluids, and if needed respiratory support including provision of oxygen,” Dr. Schibler said.

The prognosis is generally goods thanks to improvements in intensive care, he said, which some infants need because the standard oxygen therapy provided in general pediatric wards is insufficient. The new study examines whether high-flow oxygen therapy through a cannula – which he said has become more common – reduces the risk of treatment failure in non-ICU therapy, compared with standard oxygen treatment.

Dr. Schibler and his colleagues tracked 1,472 patients under 12 months with bronchiolitis and a need for oxygen treatment who were randomly assigned to high-flow or standard oxygen therapy to maintain their oxygen saturation at 92%-98% or 94%-98%, depending on policy at the hospital. The subjects were patients at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

A total of 739 infants received high-flow treatment that provided heated and humidified oxygen at a rate of 2 liters per kilogram of body weight per minute. The other 733 infants received standard oxygen therapy up to a maximum 2 liters per minute.

The treatment failed, requiring an escalation of care, in 87 of 739 patients (12%) in the high-flow group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group. (risk difference = –11% points; 95% confidence interval, –15 to –7; P less than .001).

“The ease to use and simplicity of high flow made us recognize and think that this level of respiratory care can be provided outside intensive care,” Dr. Schibler said. “This was further supported by the observational fact that most of these infants with bronchiolitis showed a dramatically improved respiratory condition once on high flow.”

Dr. Schibler said there haven’t been any signs of adverse effects from high-flow oxygen therapy. As for the cost of the treatment, he said it is “likely offset by a reduced need for intensive care therapy or costs associated with transferring to a children’s hospital.”

What should physicians and hospitals take from the study findings? “If a hospital explores the option to use high flow in bronchiolitis, then start the therapy early in the disease process or once an oxygen requirement is recognized,” Dr. Schibler said. “Implementation of a solid and structured training program with a clear hospital guideline based on the evidence will ensure the staff who care for these patients will be empowered and comfortable to adjust the oxygen levels given by the high-flow equipment. The greater the confidence and comfort level for the nursing and respiratory technician staff the better for these infants, as they will sooner observe those infants who are not responding well and may require a higher level of care such as intensive care or they will recognize the infant who responds well.”

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment and consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

SOURCE: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1112-31.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: In non-ICUs, infants under 12 months with bronchiolitis are less likely to fail treatment if they are given high-flow oxygen therapy instead of standard oxygen therapy.

Major finding: Treatment failure occurred in 8 of 739 (12%) patients in the high-flow oxygen therapy group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group.

Study details: Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 1,472 infants.

Disclosures: The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment/consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

Source: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med 2018;378(12):1112-31.

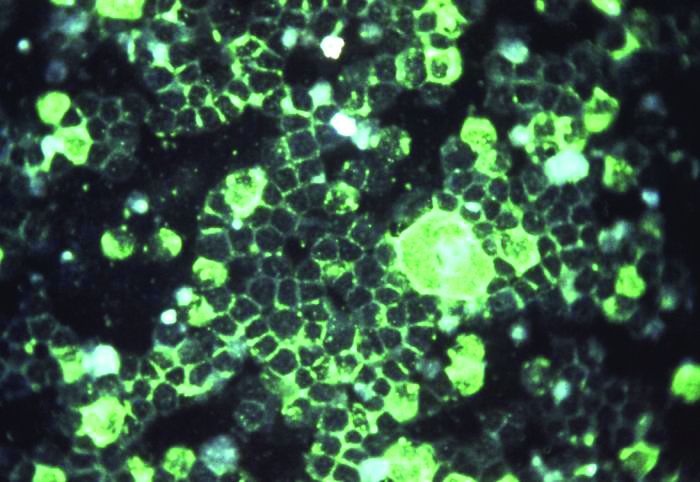

Full-term infant mortality: United States versus Europe

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Toxicology reveals worse maternal and fetal outcomes with teen marijuana use

DALLAS – . Also, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were higher in marijuana users, according to a study that incorporated universal urine toxicology testing of adolescents.

The study compared maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes in 211 marijuana-exposed with 995 unexposed pregnancies. Christina Rodriguez, MD, and her coinvestigators found that the risk of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome was higher in marijuana users, occurring in 97/211 marijuana users (46%), and in 337/995 (33.9%) of the non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Dr. Rodriguez said that since it used biological samples to confirm marijuana exposure, the study helps fill a gap in the literature. She presented the retrospective cohort study at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Previous work, she said, had established that up to 70% of pregnant women who had positive tests for tetrahydrocannabinol also denied marijuana use. “If marijuana use is determined by self-report, some women are misclassified as nonusers,” making it difficult to ascertain the true association between marijuana use during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Dr. Rodriguez of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Whether marijuana is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes is an increasingly pressing question given rapidly shifting legislation, said Dr. Rodriguez. “In a state with legal access to marijuana, use is common in adolescent pregnancies,” she said.

Participants who were enrolled in prenatal care through the University of Colorado’s adolescent maternity program, where Dr. Rodriguez is a fellow, and who delivered at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, were eligible to participate; adolescents were excluded for multiple gestation and for known major fetal anomalies or aneuploidy.

In addition to urine toxicology testing, participants also completed a uniformly administered substance use questionnaire. Marijuana exposure was defined as either having a positive urine toxicology result or self-reported marijuana use on the questionnaire (or both). Of the marijuana-exposed pregnancies, 133 (63%) of the adolescents tested positive on urine toxicology, 18 (9%) were positive by self-report, and 60 (28%) had both positive marijuana urine toxicology and positive self-report. Toxicology was available for 91% of participants.

Participants were negative for marijuana exposure if they had a negative toxicology screen, regardless of their response on the substance-use questionnaire.

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth, defined as Apgar score of 0; any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count); preterm birth, defined as spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks gestation; and infants born small for gestational age, defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile after adjustment for gestational age and sex.

Secondary outcomes included pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. Neonatal outcomes included weight, length, and head circumference at birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. An Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes was considered an adverse neonatal outcome.

The sample size was determined by an estimate drawn from previous chart abstraction that the composite outcome would be seen in 16% of the clinic’s non–marijuana exposed patients, and 24% of the marijuana-exposed patients. The investigators also factored in that 18% of adolescents in the clinic database were marijuana users.

Dr. Rodriguez and her collaborators used a variety of models for statistical analysis, some of which included self-report alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology. In the end, they found that significant associations between their composite endpoint and marijuana use were seen when patients were dichotomized into those who had at least one positive urine toxicology test, versus those who had no positive toxicology results.

One of the study limitations was that the study didn’t permit investigators to get accurate information about the quantity, timing, or route of marijuana dosing. Also, this methodology may primarily identify heavier marijuana users, said Dr. Rodriguez.

Tobacco use was determined only by self-report, and outcomes were followed over a relatively short period of time.

Still, said Dr. Rodriguez, the study had many strengths, including the use of biological sampling to determine exposure and the near-universal participant urine toxicology testing. The investigators were able to capture and account for many important factors that could confound the results, she said. “Uncertainty regarding the impact of [marijuana] on pregnancy outcomes in the literature may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure,” she and her coinvestigators wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

SOURCE: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

DALLAS – . Also, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were higher in marijuana users, according to a study that incorporated universal urine toxicology testing of adolescents.

The study compared maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes in 211 marijuana-exposed with 995 unexposed pregnancies. Christina Rodriguez, MD, and her coinvestigators found that the risk of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome was higher in marijuana users, occurring in 97/211 marijuana users (46%), and in 337/995 (33.9%) of the non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Dr. Rodriguez said that since it used biological samples to confirm marijuana exposure, the study helps fill a gap in the literature. She presented the retrospective cohort study at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Previous work, she said, had established that up to 70% of pregnant women who had positive tests for tetrahydrocannabinol also denied marijuana use. “If marijuana use is determined by self-report, some women are misclassified as nonusers,” making it difficult to ascertain the true association between marijuana use during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Dr. Rodriguez of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Whether marijuana is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes is an increasingly pressing question given rapidly shifting legislation, said Dr. Rodriguez. “In a state with legal access to marijuana, use is common in adolescent pregnancies,” she said.

Participants who were enrolled in prenatal care through the University of Colorado’s adolescent maternity program, where Dr. Rodriguez is a fellow, and who delivered at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, were eligible to participate; adolescents were excluded for multiple gestation and for known major fetal anomalies or aneuploidy.

In addition to urine toxicology testing, participants also completed a uniformly administered substance use questionnaire. Marijuana exposure was defined as either having a positive urine toxicology result or self-reported marijuana use on the questionnaire (or both). Of the marijuana-exposed pregnancies, 133 (63%) of the adolescents tested positive on urine toxicology, 18 (9%) were positive by self-report, and 60 (28%) had both positive marijuana urine toxicology and positive self-report. Toxicology was available for 91% of participants.

Participants were negative for marijuana exposure if they had a negative toxicology screen, regardless of their response on the substance-use questionnaire.

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth, defined as Apgar score of 0; any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count); preterm birth, defined as spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks gestation; and infants born small for gestational age, defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile after adjustment for gestational age and sex.

Secondary outcomes included pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. Neonatal outcomes included weight, length, and head circumference at birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. An Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes was considered an adverse neonatal outcome.

The sample size was determined by an estimate drawn from previous chart abstraction that the composite outcome would be seen in 16% of the clinic’s non–marijuana exposed patients, and 24% of the marijuana-exposed patients. The investigators also factored in that 18% of adolescents in the clinic database were marijuana users.

Dr. Rodriguez and her collaborators used a variety of models for statistical analysis, some of which included self-report alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology. In the end, they found that significant associations between their composite endpoint and marijuana use were seen when patients were dichotomized into those who had at least one positive urine toxicology test, versus those who had no positive toxicology results.

One of the study limitations was that the study didn’t permit investigators to get accurate information about the quantity, timing, or route of marijuana dosing. Also, this methodology may primarily identify heavier marijuana users, said Dr. Rodriguez.

Tobacco use was determined only by self-report, and outcomes were followed over a relatively short period of time.

Still, said Dr. Rodriguez, the study had many strengths, including the use of biological sampling to determine exposure and the near-universal participant urine toxicology testing. The investigators were able to capture and account for many important factors that could confound the results, she said. “Uncertainty regarding the impact of [marijuana] on pregnancy outcomes in the literature may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure,” she and her coinvestigators wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

SOURCE: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

DALLAS – . Also, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were higher in marijuana users, according to a study that incorporated universal urine toxicology testing of adolescents.

The study compared maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes in 211 marijuana-exposed with 995 unexposed pregnancies. Christina Rodriguez, MD, and her coinvestigators found that the risk of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome was higher in marijuana users, occurring in 97/211 marijuana users (46%), and in 337/995 (33.9%) of the non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Dr. Rodriguez said that since it used biological samples to confirm marijuana exposure, the study helps fill a gap in the literature. She presented the retrospective cohort study at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Previous work, she said, had established that up to 70% of pregnant women who had positive tests for tetrahydrocannabinol also denied marijuana use. “If marijuana use is determined by self-report, some women are misclassified as nonusers,” making it difficult to ascertain the true association between marijuana use during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Dr. Rodriguez of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Whether marijuana is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes is an increasingly pressing question given rapidly shifting legislation, said Dr. Rodriguez. “In a state with legal access to marijuana, use is common in adolescent pregnancies,” she said.

Participants who were enrolled in prenatal care through the University of Colorado’s adolescent maternity program, where Dr. Rodriguez is a fellow, and who delivered at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, were eligible to participate; adolescents were excluded for multiple gestation and for known major fetal anomalies or aneuploidy.

In addition to urine toxicology testing, participants also completed a uniformly administered substance use questionnaire. Marijuana exposure was defined as either having a positive urine toxicology result or self-reported marijuana use on the questionnaire (or both). Of the marijuana-exposed pregnancies, 133 (63%) of the adolescents tested positive on urine toxicology, 18 (9%) were positive by self-report, and 60 (28%) had both positive marijuana urine toxicology and positive self-report. Toxicology was available for 91% of participants.

Participants were negative for marijuana exposure if they had a negative toxicology screen, regardless of their response on the substance-use questionnaire.

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth, defined as Apgar score of 0; any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count); preterm birth, defined as spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks gestation; and infants born small for gestational age, defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile after adjustment for gestational age and sex.

Secondary outcomes included pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. Neonatal outcomes included weight, length, and head circumference at birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. An Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes was considered an adverse neonatal outcome.

The sample size was determined by an estimate drawn from previous chart abstraction that the composite outcome would be seen in 16% of the clinic’s non–marijuana exposed patients, and 24% of the marijuana-exposed patients. The investigators also factored in that 18% of adolescents in the clinic database were marijuana users.

Dr. Rodriguez and her collaborators used a variety of models for statistical analysis, some of which included self-report alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology. In the end, they found that significant associations between their composite endpoint and marijuana use were seen when patients were dichotomized into those who had at least one positive urine toxicology test, versus those who had no positive toxicology results.

One of the study limitations was that the study didn’t permit investigators to get accurate information about the quantity, timing, or route of marijuana dosing. Also, this methodology may primarily identify heavier marijuana users, said Dr. Rodriguez.

Tobacco use was determined only by self-report, and outcomes were followed over a relatively short period of time.

Still, said Dr. Rodriguez, the study had many strengths, including the use of biological sampling to determine exposure and the near-universal participant urine toxicology testing. The investigators were able to capture and account for many important factors that could confound the results, she said. “Uncertainty regarding the impact of [marijuana] on pregnancy outcomes in the literature may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure,” she and her coinvestigators wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

SOURCE: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Maternal and fetal outcomes were worse when marijuana use was detected by urine toxicology.

Major finding: A composite adverse outcome occurred in 46% of adolescent marijuana users, compared with 34% of non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of participants in an adolescent maternity clinic.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

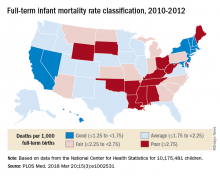

Newborn oral rotavirus vaccine held effective

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.