User login

Renal Medication Dosing: "The Good, the Bad and the Iatrogenic"

Kim Zuber offers insight into the iatrogenic causes of acute kidney injury. This video provides three takeaways in less than three minutes from her presentation at the 2015 MEDS conference, which

|

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Don’t miss Kim Zuber sharing her expertise on renal medication dosing as well as CKD and the diabetic kidney at the upcoming 2016 MEDS conference. Click here to learn more.

Kim Zuber offers insight into the iatrogenic causes of acute kidney injury. This video provides three takeaways in less than three minutes from her presentation at the 2015 MEDS conference, which

|

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Don’t miss Kim Zuber sharing her expertise on renal medication dosing as well as CKD and the diabetic kidney at the upcoming 2016 MEDS conference. Click here to learn more.

Kim Zuber offers insight into the iatrogenic causes of acute kidney injury. This video provides three takeaways in less than three minutes from her presentation at the 2015 MEDS conference, which

|

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Don’t miss Kim Zuber sharing her expertise on renal medication dosing as well as CKD and the diabetic kidney at the upcoming 2016 MEDS conference. Click here to learn more.

Casting stones

What Matters prides itself on reviewing the literature and presenting thoughtful commentary on articles that are relevant and applicable to the practicing clinician. We separate the wheat from the chaff. We are not, however, above taking on attention-grabbing articles.

Over the years, this column has reported on various methods to facilitate the expulsion of kidney stones, including tamsulosin, phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, and steroids. But this one called out for our assessment: sex to expel kidney stones. Erroneously perceived prurient interests must be forgiven.

Dr. Omer Gokhan Doluoglu of the Clinic of Ankara (Turkey) Training and Research Hospital and colleagues conducted a randomized trial evaluating the effectiveness of sexual intercourse, tamsulosin, or standard medical therapy for kidney stone expulsion (Urology. 2015;86[1]:19-24). Potential subjects were eligible for inclusion if they had radiopaque distal ureteral stones. Subjects were excluded if the stones were larger than 6 mm.

Subjects were randomized to encouragement to have sexual intercourse at least three times per week, tamsulosin 0.4 mg/day, or symptomatic therapy alone. All patients received an antispasmodic and an anti-inflammatory, and were told to drink 2 L of water per day. Sexual intercourse and masturbation were prohibited in groups 2 and 3 during the treatment period, which lasted 4 weeks.

Ninety patients were randomized to the three groups. The mean stone size was 4.7-5.0 mm and not significantly different between the groups.

At 2 weeks, 83.9% (26 of 31) of the patients in the intercourse group, 47.6% (10 of 21) in the tamsulosin group, and 34.8% (8 of 23) passed the stones (P = .001). There was no difference between the groups at 4 weeks. Mean expulsion times were 10 days, 16.6 days, and 18 days, respectively (P = .0001).

The study’s authors propose that nitrous oxide is operant here by causing ureteric relaxation when released to create penile tumescence and during sexual activity. Because masturbation could achieve the same effect, patients in the other groups were told they could not. How effective this instruction was in the current study is unknown, because only “sexual intercourses” were collected on follow-up.

The random-envelope method used is less than ideal, and no data were reported on differences in the number of sexual experiences between groups. If we assume for a moment that a real effect exists, one is left wondering if more would be better. Does the requirement of a partner decrease the likelihood of more frequent stone-expelling sexual experiences? If our patients do not have sexual partners, do we not share these data with them?

And if we use PDE5 inhibitors and encourage sexual activity, do we … kill two birds with one stone?

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article. Follow him on Twitter @jonebbert.

What Matters prides itself on reviewing the literature and presenting thoughtful commentary on articles that are relevant and applicable to the practicing clinician. We separate the wheat from the chaff. We are not, however, above taking on attention-grabbing articles.

Over the years, this column has reported on various methods to facilitate the expulsion of kidney stones, including tamsulosin, phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, and steroids. But this one called out for our assessment: sex to expel kidney stones. Erroneously perceived prurient interests must be forgiven.

Dr. Omer Gokhan Doluoglu of the Clinic of Ankara (Turkey) Training and Research Hospital and colleagues conducted a randomized trial evaluating the effectiveness of sexual intercourse, tamsulosin, or standard medical therapy for kidney stone expulsion (Urology. 2015;86[1]:19-24). Potential subjects were eligible for inclusion if they had radiopaque distal ureteral stones. Subjects were excluded if the stones were larger than 6 mm.

Subjects were randomized to encouragement to have sexual intercourse at least three times per week, tamsulosin 0.4 mg/day, or symptomatic therapy alone. All patients received an antispasmodic and an anti-inflammatory, and were told to drink 2 L of water per day. Sexual intercourse and masturbation were prohibited in groups 2 and 3 during the treatment period, which lasted 4 weeks.

Ninety patients were randomized to the three groups. The mean stone size was 4.7-5.0 mm and not significantly different between the groups.

At 2 weeks, 83.9% (26 of 31) of the patients in the intercourse group, 47.6% (10 of 21) in the tamsulosin group, and 34.8% (8 of 23) passed the stones (P = .001). There was no difference between the groups at 4 weeks. Mean expulsion times were 10 days, 16.6 days, and 18 days, respectively (P = .0001).

The study’s authors propose that nitrous oxide is operant here by causing ureteric relaxation when released to create penile tumescence and during sexual activity. Because masturbation could achieve the same effect, patients in the other groups were told they could not. How effective this instruction was in the current study is unknown, because only “sexual intercourses” were collected on follow-up.

The random-envelope method used is less than ideal, and no data were reported on differences in the number of sexual experiences between groups. If we assume for a moment that a real effect exists, one is left wondering if more would be better. Does the requirement of a partner decrease the likelihood of more frequent stone-expelling sexual experiences? If our patients do not have sexual partners, do we not share these data with them?

And if we use PDE5 inhibitors and encourage sexual activity, do we … kill two birds with one stone?

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article. Follow him on Twitter @jonebbert.

What Matters prides itself on reviewing the literature and presenting thoughtful commentary on articles that are relevant and applicable to the practicing clinician. We separate the wheat from the chaff. We are not, however, above taking on attention-grabbing articles.

Over the years, this column has reported on various methods to facilitate the expulsion of kidney stones, including tamsulosin, phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, and steroids. But this one called out for our assessment: sex to expel kidney stones. Erroneously perceived prurient interests must be forgiven.

Dr. Omer Gokhan Doluoglu of the Clinic of Ankara (Turkey) Training and Research Hospital and colleagues conducted a randomized trial evaluating the effectiveness of sexual intercourse, tamsulosin, or standard medical therapy for kidney stone expulsion (Urology. 2015;86[1]:19-24). Potential subjects were eligible for inclusion if they had radiopaque distal ureteral stones. Subjects were excluded if the stones were larger than 6 mm.

Subjects were randomized to encouragement to have sexual intercourse at least three times per week, tamsulosin 0.4 mg/day, or symptomatic therapy alone. All patients received an antispasmodic and an anti-inflammatory, and were told to drink 2 L of water per day. Sexual intercourse and masturbation were prohibited in groups 2 and 3 during the treatment period, which lasted 4 weeks.

Ninety patients were randomized to the three groups. The mean stone size was 4.7-5.0 mm and not significantly different between the groups.

At 2 weeks, 83.9% (26 of 31) of the patients in the intercourse group, 47.6% (10 of 21) in the tamsulosin group, and 34.8% (8 of 23) passed the stones (P = .001). There was no difference between the groups at 4 weeks. Mean expulsion times were 10 days, 16.6 days, and 18 days, respectively (P = .0001).

The study’s authors propose that nitrous oxide is operant here by causing ureteric relaxation when released to create penile tumescence and during sexual activity. Because masturbation could achieve the same effect, patients in the other groups were told they could not. How effective this instruction was in the current study is unknown, because only “sexual intercourses” were collected on follow-up.

The random-envelope method used is less than ideal, and no data were reported on differences in the number of sexual experiences between groups. If we assume for a moment that a real effect exists, one is left wondering if more would be better. Does the requirement of a partner decrease the likelihood of more frequent stone-expelling sexual experiences? If our patients do not have sexual partners, do we not share these data with them?

And if we use PDE5 inhibitors and encourage sexual activity, do we … kill two birds with one stone?

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article. Follow him on Twitter @jonebbert.

When in Doubt, Blame the Drug

A 54-year-old woman with chronic renal disease was diagnosed with gout and prescribed allopurinol. Two days later, she was evaluated by her nephrologist, whom she informed about her new medication.

Subsequently, the patient developed fever and rash. Laboratory analysis indicated elevated transaminase levels and eosinophilia. She was admitted to the hospital.

During her stay, an infectious disease consultation was obtained, and the allopurinol was discontinued. When the patient’s condition improved, she was discharged.

Following discharge, the patient resumed taking allopurinol, and her rash returned. Eleven days later, she returned to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with toxic epidermal necrolysis. She was found to have a desquamating rash covering 62% of her body. The patient was transferred to a burn center but eventually succumbed to multi-organ failure.

The patient’s estate filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against the nephrologist alleging negligence—specifically, failure to diagnose toxic epidermal necrolysis and failure to review her medications more carefully.

Continue for the outcome >>

OUTCOME

A $5.1 million verdict was returned against the nephrologist.

COMMENT

Many medications cause rash and are subsequently withdrawn; in a few cases, the effects are life threatening. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) are relatively uncommon but potentially fatal examples.

From the limited facts presented, we know that a 54-year-old woman with established renal disease of unknown magnitude was prescribed allopurinol for gout and consulted the nephrologist two days later. It is unclear if the patient had the rash during the first visit with her nephrologist. But we do know that she was eventually admitted and maintained on allopurinol while she had the rash, pending infectious disease consultation. At some point, the allopurinol was apparently stopped and the rash improved. After discharge, the patient resumed taking allopurinol. The rash not only returned but also worsened, necessitating her readmission to a burn center.

TEN, like SJS, is often induced by certain medications, including sulfonamides, macrolides, penicillins, and quinolones. Allopurinol, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and lamotrigine are frequently implicated as well.

TEN is rare but serious. The initial presentation may be subtle, with influenza-like symptoms such as malaise, fever, cough, rhinitis, headache, and arthralgia—and the most discriminating sign: rash.

The rash begins as a poorly defined, erythematous macular rash with purpuric centers. The lesions predominate on the torso and face, sparing the scalp. Mucosal membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases.1 Pain at the site of the skin lesions is often the predominate symptom and is often out of proportion to physical findings. Over a period of hours to days, the rash coalesces to form flaccid blisters and sheetlike epidermal detachment.2 In established cases, patients will nearly universally demonstrate Nikolsky’s sign: Mild frictional contact with the skin results in epithelial desquamation and immediate blistering.

Management involves immediate withdrawal of the offending agent and hospitalization for aggressive management. The mortality rate is high (30% to 60%3) and generally attributed to sepsis or multi-organ failure.

As clinicians, we are sometimes hesitant to label a rash allergic—thereby forever disqualifying an entire class of useful agents from that patient. However, in this case, the fact that the rash occurred simultaneously with a constellation of signs and symptoms perhaps made the rash appear to be part of an infectious process and not a drug-induced reaction. That is the challenge with TEN and SJS: The symptoms are subtle, flu-like, and confounding.

Here, the nephrologist apparently did not take action to stop the allopurinol after the patient first developed the rash. The jury was persuaded that a reasonably prudent clinician would have recognized the clinical presentation and stopped the allopurinol—and certainly not restarted it following discharge (especially after the allopurinol was stopped in the hospital and the rash began to improve).

This case brings to mind two physicians from my training who made an impression. The first was a second-year internal medicine resident. I remember quietly remarking to another student during rounds, “He is really good.” Overhearing, an attending physician answered, “He is really good because in his workup he always considers a presentation as a function of an underlying process, and walks through each of those processes in formulating his differential.”

“Walking through” various disease categories forces the clinician to consider them all: infectious, autoimmune, neoplastic, environmental/toxic, vascular, traumatic, metabolic, inflammatory. In challenging cases, I’ve found it helpful to step backward into those broad basic categories of disease and reconsider the clinical picture.

Here, doing so may have allowed the clinician to reconsider inflammatory and autoimmune processes and revisit the possibility of iatrogenic toxic/environmental causes (ie, the allopurinol). Perhaps the outcome of this case would have been different.

The second physician was a nephrology fellow, who left me with this piece of wisdom: “When in doubt, blame the drug.” Since nephrologists are expert drug-blamers, I suspect the early stages of this unfortunate case presented a clinical challenge.

IN SUM

Before you “missile lock” onto a diagnosis, take a mental step back to consider broad categories of disease. —DML

REFERENCES

1. Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(4):419-436.

2. Cohen V, Jellinek SP, Schwartz RA, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Medscape; 2013. emedicine.medscape.com/article/229698-overview. Accessed September 16, 2015.

3. Schulz JT, Sheridan RL, Ryan CM, et al. A 10-year experience with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21(3): 199-204.

A 54-year-old woman with chronic renal disease was diagnosed with gout and prescribed allopurinol. Two days later, she was evaluated by her nephrologist, whom she informed about her new medication.

Subsequently, the patient developed fever and rash. Laboratory analysis indicated elevated transaminase levels and eosinophilia. She was admitted to the hospital.

During her stay, an infectious disease consultation was obtained, and the allopurinol was discontinued. When the patient’s condition improved, she was discharged.

Following discharge, the patient resumed taking allopurinol, and her rash returned. Eleven days later, she returned to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with toxic epidermal necrolysis. She was found to have a desquamating rash covering 62% of her body. The patient was transferred to a burn center but eventually succumbed to multi-organ failure.

The patient’s estate filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against the nephrologist alleging negligence—specifically, failure to diagnose toxic epidermal necrolysis and failure to review her medications more carefully.

Continue for the outcome >>

OUTCOME

A $5.1 million verdict was returned against the nephrologist.

COMMENT

Many medications cause rash and are subsequently withdrawn; in a few cases, the effects are life threatening. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) are relatively uncommon but potentially fatal examples.

From the limited facts presented, we know that a 54-year-old woman with established renal disease of unknown magnitude was prescribed allopurinol for gout and consulted the nephrologist two days later. It is unclear if the patient had the rash during the first visit with her nephrologist. But we do know that she was eventually admitted and maintained on allopurinol while she had the rash, pending infectious disease consultation. At some point, the allopurinol was apparently stopped and the rash improved. After discharge, the patient resumed taking allopurinol. The rash not only returned but also worsened, necessitating her readmission to a burn center.

TEN, like SJS, is often induced by certain medications, including sulfonamides, macrolides, penicillins, and quinolones. Allopurinol, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and lamotrigine are frequently implicated as well.

TEN is rare but serious. The initial presentation may be subtle, with influenza-like symptoms such as malaise, fever, cough, rhinitis, headache, and arthralgia—and the most discriminating sign: rash.

The rash begins as a poorly defined, erythematous macular rash with purpuric centers. The lesions predominate on the torso and face, sparing the scalp. Mucosal membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases.1 Pain at the site of the skin lesions is often the predominate symptom and is often out of proportion to physical findings. Over a period of hours to days, the rash coalesces to form flaccid blisters and sheetlike epidermal detachment.2 In established cases, patients will nearly universally demonstrate Nikolsky’s sign: Mild frictional contact with the skin results in epithelial desquamation and immediate blistering.

Management involves immediate withdrawal of the offending agent and hospitalization for aggressive management. The mortality rate is high (30% to 60%3) and generally attributed to sepsis or multi-organ failure.

As clinicians, we are sometimes hesitant to label a rash allergic—thereby forever disqualifying an entire class of useful agents from that patient. However, in this case, the fact that the rash occurred simultaneously with a constellation of signs and symptoms perhaps made the rash appear to be part of an infectious process and not a drug-induced reaction. That is the challenge with TEN and SJS: The symptoms are subtle, flu-like, and confounding.

Here, the nephrologist apparently did not take action to stop the allopurinol after the patient first developed the rash. The jury was persuaded that a reasonably prudent clinician would have recognized the clinical presentation and stopped the allopurinol—and certainly not restarted it following discharge (especially after the allopurinol was stopped in the hospital and the rash began to improve).

This case brings to mind two physicians from my training who made an impression. The first was a second-year internal medicine resident. I remember quietly remarking to another student during rounds, “He is really good.” Overhearing, an attending physician answered, “He is really good because in his workup he always considers a presentation as a function of an underlying process, and walks through each of those processes in formulating his differential.”

“Walking through” various disease categories forces the clinician to consider them all: infectious, autoimmune, neoplastic, environmental/toxic, vascular, traumatic, metabolic, inflammatory. In challenging cases, I’ve found it helpful to step backward into those broad basic categories of disease and reconsider the clinical picture.

Here, doing so may have allowed the clinician to reconsider inflammatory and autoimmune processes and revisit the possibility of iatrogenic toxic/environmental causes (ie, the allopurinol). Perhaps the outcome of this case would have been different.

The second physician was a nephrology fellow, who left me with this piece of wisdom: “When in doubt, blame the drug.” Since nephrologists are expert drug-blamers, I suspect the early stages of this unfortunate case presented a clinical challenge.

IN SUM

Before you “missile lock” onto a diagnosis, take a mental step back to consider broad categories of disease. —DML

REFERENCES

1. Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(4):419-436.

2. Cohen V, Jellinek SP, Schwartz RA, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Medscape; 2013. emedicine.medscape.com/article/229698-overview. Accessed September 16, 2015.

3. Schulz JT, Sheridan RL, Ryan CM, et al. A 10-year experience with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21(3): 199-204.

A 54-year-old woman with chronic renal disease was diagnosed with gout and prescribed allopurinol. Two days later, she was evaluated by her nephrologist, whom she informed about her new medication.

Subsequently, the patient developed fever and rash. Laboratory analysis indicated elevated transaminase levels and eosinophilia. She was admitted to the hospital.

During her stay, an infectious disease consultation was obtained, and the allopurinol was discontinued. When the patient’s condition improved, she was discharged.

Following discharge, the patient resumed taking allopurinol, and her rash returned. Eleven days later, she returned to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with toxic epidermal necrolysis. She was found to have a desquamating rash covering 62% of her body. The patient was transferred to a burn center but eventually succumbed to multi-organ failure.

The patient’s estate filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against the nephrologist alleging negligence—specifically, failure to diagnose toxic epidermal necrolysis and failure to review her medications more carefully.

Continue for the outcome >>

OUTCOME

A $5.1 million verdict was returned against the nephrologist.

COMMENT

Many medications cause rash and are subsequently withdrawn; in a few cases, the effects are life threatening. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) are relatively uncommon but potentially fatal examples.

From the limited facts presented, we know that a 54-year-old woman with established renal disease of unknown magnitude was prescribed allopurinol for gout and consulted the nephrologist two days later. It is unclear if the patient had the rash during the first visit with her nephrologist. But we do know that she was eventually admitted and maintained on allopurinol while she had the rash, pending infectious disease consultation. At some point, the allopurinol was apparently stopped and the rash improved. After discharge, the patient resumed taking allopurinol. The rash not only returned but also worsened, necessitating her readmission to a burn center.

TEN, like SJS, is often induced by certain medications, including sulfonamides, macrolides, penicillins, and quinolones. Allopurinol, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and lamotrigine are frequently implicated as well.

TEN is rare but serious. The initial presentation may be subtle, with influenza-like symptoms such as malaise, fever, cough, rhinitis, headache, and arthralgia—and the most discriminating sign: rash.

The rash begins as a poorly defined, erythematous macular rash with purpuric centers. The lesions predominate on the torso and face, sparing the scalp. Mucosal membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases.1 Pain at the site of the skin lesions is often the predominate symptom and is often out of proportion to physical findings. Over a period of hours to days, the rash coalesces to form flaccid blisters and sheetlike epidermal detachment.2 In established cases, patients will nearly universally demonstrate Nikolsky’s sign: Mild frictional contact with the skin results in epithelial desquamation and immediate blistering.

Management involves immediate withdrawal of the offending agent and hospitalization for aggressive management. The mortality rate is high (30% to 60%3) and generally attributed to sepsis or multi-organ failure.

As clinicians, we are sometimes hesitant to label a rash allergic—thereby forever disqualifying an entire class of useful agents from that patient. However, in this case, the fact that the rash occurred simultaneously with a constellation of signs and symptoms perhaps made the rash appear to be part of an infectious process and not a drug-induced reaction. That is the challenge with TEN and SJS: The symptoms are subtle, flu-like, and confounding.

Here, the nephrologist apparently did not take action to stop the allopurinol after the patient first developed the rash. The jury was persuaded that a reasonably prudent clinician would have recognized the clinical presentation and stopped the allopurinol—and certainly not restarted it following discharge (especially after the allopurinol was stopped in the hospital and the rash began to improve).

This case brings to mind two physicians from my training who made an impression. The first was a second-year internal medicine resident. I remember quietly remarking to another student during rounds, “He is really good.” Overhearing, an attending physician answered, “He is really good because in his workup he always considers a presentation as a function of an underlying process, and walks through each of those processes in formulating his differential.”

“Walking through” various disease categories forces the clinician to consider them all: infectious, autoimmune, neoplastic, environmental/toxic, vascular, traumatic, metabolic, inflammatory. In challenging cases, I’ve found it helpful to step backward into those broad basic categories of disease and reconsider the clinical picture.

Here, doing so may have allowed the clinician to reconsider inflammatory and autoimmune processes and revisit the possibility of iatrogenic toxic/environmental causes (ie, the allopurinol). Perhaps the outcome of this case would have been different.

The second physician was a nephrology fellow, who left me with this piece of wisdom: “When in doubt, blame the drug.” Since nephrologists are expert drug-blamers, I suspect the early stages of this unfortunate case presented a clinical challenge.

IN SUM

Before you “missile lock” onto a diagnosis, take a mental step back to consider broad categories of disease. —DML

REFERENCES

1. Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(4):419-436.

2. Cohen V, Jellinek SP, Schwartz RA, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Medscape; 2013. emedicine.medscape.com/article/229698-overview. Accessed September 16, 2015.

3. Schulz JT, Sheridan RL, Ryan CM, et al. A 10-year experience with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21(3): 199-204.

Left subconjunctival hemorrhage • renal dysfunction • international normalized ratio of 4.5 • Dx?

THE CASE

A 71-year-old woman came to our clinic with a left subconjunctival hemorrhage. She had a history of atrial flutter and had received a liver transplant approximately 10 years ago. The patient reported having a procedure 2 weeks before her visit with us to remove a basal cell carcinoma on her lower left eyelid, but had no recent changes in vision or physical damage to the eye.

In the past year, she had been started on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily after developing symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Our patient had also been receiving tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily since her transplant. Other medications she was taking included hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d for rheumatoid arthritis, propafenone 225 mg twice daily for atrial fibrillation, valsartan 80 mg/d for hypertension, and ranitidine 150 mg/d for reflux.

Venipuncture coagulation tests showed a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 75.1 seconds, a prothrombin time (PT) of 46.1 seconds, and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.5 (normal range: 0.8-1.2). Point-of-care INR results were not obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable with the exception of a low platelet count and high red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Our patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were both within normal limits.

Kidney function tests told another story. The patient’s serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were elevated (1.54 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively) and her creatinine clearance (CrCl; 30.2 mL/min) suggested moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

The patient’s CHADS2 score was calculated as 1, suggesting she had a low-to-moderate risk of stroke.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a left subconjunctival hemorrhage and an elevated venipuncture INR. Based on her renal dysfunction, we suspected that her elevated INR was likely due to an excessive dose of dabigatran, as well as an interaction between dabigatran and tacrolimus.

DISCUSSION

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. An important advantage of dabigatran compared to warfarin is that the fixed-dose regimen does not require routine anticoagulation monitoring. In cases where anticoagulation monitoring is needed, PTT is the preferred method.1

While PT and INR have generally not been shown to accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation with dabigatran at therapeutic doses, there have been in vitro reports of elevated INRs with supratherapeutic dabigatran levels.2,3 At a typical peak therapeutic dabigatran concentration of approximately 184 ng/mL, the INR generally ranged from 1.1 to 1.7.2 However, at a dabigatran concentration of 1000 ng/mL, the INR was elevated to 4.5,2,3 which is the same venipuncture INR recorded in our patient. While there have been published reports of falsely elevated point-of-care INR results compared to corresponding venipuncture INR results in patients taking dabigatran,4,5 a literature review found only a case of an elevated venipuncture INR in an end-stage renal disease patient receiving hemodialysis.6

In the case noted above, as well as our patient, an accumulation of dabigatran due to the patient’s renal dysfunction likely resulted in high plasma concentrations and therefore an elevated venipuncture INR. The elimination half-life for dabigatran is approximately 14 hours in patients with normal renal function; in a patient with severe renal impairment, the half-life can be up to 28 hours.7 Our patient’s CrCl at the time of presentation was 30.2 mL/min, which indicated moderate to severe renal dysfunction. Based on dabigatran prescribing recommendations, a dose adjustment to 75 mg bid might be appropriate.1 (Our patient was taking 150 mg bid.)

We do not believe our patient’s elevated INR was due to her liver transplant because there were no clinical signs of liver dysfunction. A more likely contributing factor was a drug interaction with tacrolimus. Dabigatran is a moderate affinity P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate and tacrolimus is both a P-gp substrate and inhibitor. While an interaction between tacrolimus and dabigatran has not been studied directly, concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl: 15-30 mL/min).1 For these theoretical interactions, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) has been developed.8 In our patient’s case, the calculated DIPS score of 5 suggests a probable interaction, likely due to P-gp inhibition. The other medications our patient was taking did not have this interaction and were unlikely to contribute to the elevated INR and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Our patient was instructed to stop taking dabigatran and return in 3 days for additional lab tests. At her follow-up visit, the lab results were PTT, 34.3 seconds; PT, 11.6 seconds; and venipuncture INR, 1.1. Her CBC was unremarkable and unchanged. Shortly after the follow-up visit, our patient was assessed by her cardiologist. Due to her renal dysfunction, risk of bleeding, and relatively low CHADS2 score, the cardiologist decided to discontinue dabigatran and start her on aspirin.

THE TAKEAWAY

Dabigatran may cause elevated INR levels in patients with renal dysfunction and/or those taking other medications that could interact with dabigatran. Concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor (such as tacrolimus) and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Despite the lack of required routine laboratory monitoring, renal function and drug interactions associated with dabigatran therapy should be monitored closely.

1. Praxada [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

2. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

3. Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, et al; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371-378.

4. Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e40.

5. van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-ofcare INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125:417-420.

6. Kim J, Yadava M, An IC, et al. Coagulopathy and extremely elevated PT/INR after dabigatran etexilate use in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:131395.

7. Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259-268.

8. Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674-680.

THE CASE

A 71-year-old woman came to our clinic with a left subconjunctival hemorrhage. She had a history of atrial flutter and had received a liver transplant approximately 10 years ago. The patient reported having a procedure 2 weeks before her visit with us to remove a basal cell carcinoma on her lower left eyelid, but had no recent changes in vision or physical damage to the eye.

In the past year, she had been started on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily after developing symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Our patient had also been receiving tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily since her transplant. Other medications she was taking included hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d for rheumatoid arthritis, propafenone 225 mg twice daily for atrial fibrillation, valsartan 80 mg/d for hypertension, and ranitidine 150 mg/d for reflux.

Venipuncture coagulation tests showed a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 75.1 seconds, a prothrombin time (PT) of 46.1 seconds, and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.5 (normal range: 0.8-1.2). Point-of-care INR results were not obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable with the exception of a low platelet count and high red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Our patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were both within normal limits.

Kidney function tests told another story. The patient’s serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were elevated (1.54 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively) and her creatinine clearance (CrCl; 30.2 mL/min) suggested moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

The patient’s CHADS2 score was calculated as 1, suggesting she had a low-to-moderate risk of stroke.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a left subconjunctival hemorrhage and an elevated venipuncture INR. Based on her renal dysfunction, we suspected that her elevated INR was likely due to an excessive dose of dabigatran, as well as an interaction between dabigatran and tacrolimus.

DISCUSSION

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. An important advantage of dabigatran compared to warfarin is that the fixed-dose regimen does not require routine anticoagulation monitoring. In cases where anticoagulation monitoring is needed, PTT is the preferred method.1

While PT and INR have generally not been shown to accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation with dabigatran at therapeutic doses, there have been in vitro reports of elevated INRs with supratherapeutic dabigatran levels.2,3 At a typical peak therapeutic dabigatran concentration of approximately 184 ng/mL, the INR generally ranged from 1.1 to 1.7.2 However, at a dabigatran concentration of 1000 ng/mL, the INR was elevated to 4.5,2,3 which is the same venipuncture INR recorded in our patient. While there have been published reports of falsely elevated point-of-care INR results compared to corresponding venipuncture INR results in patients taking dabigatran,4,5 a literature review found only a case of an elevated venipuncture INR in an end-stage renal disease patient receiving hemodialysis.6

In the case noted above, as well as our patient, an accumulation of dabigatran due to the patient’s renal dysfunction likely resulted in high plasma concentrations and therefore an elevated venipuncture INR. The elimination half-life for dabigatran is approximately 14 hours in patients with normal renal function; in a patient with severe renal impairment, the half-life can be up to 28 hours.7 Our patient’s CrCl at the time of presentation was 30.2 mL/min, which indicated moderate to severe renal dysfunction. Based on dabigatran prescribing recommendations, a dose adjustment to 75 mg bid might be appropriate.1 (Our patient was taking 150 mg bid.)

We do not believe our patient’s elevated INR was due to her liver transplant because there were no clinical signs of liver dysfunction. A more likely contributing factor was a drug interaction with tacrolimus. Dabigatran is a moderate affinity P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate and tacrolimus is both a P-gp substrate and inhibitor. While an interaction between tacrolimus and dabigatran has not been studied directly, concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl: 15-30 mL/min).1 For these theoretical interactions, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) has been developed.8 In our patient’s case, the calculated DIPS score of 5 suggests a probable interaction, likely due to P-gp inhibition. The other medications our patient was taking did not have this interaction and were unlikely to contribute to the elevated INR and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Our patient was instructed to stop taking dabigatran and return in 3 days for additional lab tests. At her follow-up visit, the lab results were PTT, 34.3 seconds; PT, 11.6 seconds; and venipuncture INR, 1.1. Her CBC was unremarkable and unchanged. Shortly after the follow-up visit, our patient was assessed by her cardiologist. Due to her renal dysfunction, risk of bleeding, and relatively low CHADS2 score, the cardiologist decided to discontinue dabigatran and start her on aspirin.

THE TAKEAWAY

Dabigatran may cause elevated INR levels in patients with renal dysfunction and/or those taking other medications that could interact with dabigatran. Concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor (such as tacrolimus) and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Despite the lack of required routine laboratory monitoring, renal function and drug interactions associated with dabigatran therapy should be monitored closely.

THE CASE

A 71-year-old woman came to our clinic with a left subconjunctival hemorrhage. She had a history of atrial flutter and had received a liver transplant approximately 10 years ago. The patient reported having a procedure 2 weeks before her visit with us to remove a basal cell carcinoma on her lower left eyelid, but had no recent changes in vision or physical damage to the eye.

In the past year, she had been started on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily after developing symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Our patient had also been receiving tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily since her transplant. Other medications she was taking included hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d for rheumatoid arthritis, propafenone 225 mg twice daily for atrial fibrillation, valsartan 80 mg/d for hypertension, and ranitidine 150 mg/d for reflux.

Venipuncture coagulation tests showed a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 75.1 seconds, a prothrombin time (PT) of 46.1 seconds, and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.5 (normal range: 0.8-1.2). Point-of-care INR results were not obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable with the exception of a low platelet count and high red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Our patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were both within normal limits.

Kidney function tests told another story. The patient’s serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were elevated (1.54 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively) and her creatinine clearance (CrCl; 30.2 mL/min) suggested moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

The patient’s CHADS2 score was calculated as 1, suggesting she had a low-to-moderate risk of stroke.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a left subconjunctival hemorrhage and an elevated venipuncture INR. Based on her renal dysfunction, we suspected that her elevated INR was likely due to an excessive dose of dabigatran, as well as an interaction between dabigatran and tacrolimus.

DISCUSSION

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. An important advantage of dabigatran compared to warfarin is that the fixed-dose regimen does not require routine anticoagulation monitoring. In cases where anticoagulation monitoring is needed, PTT is the preferred method.1

While PT and INR have generally not been shown to accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation with dabigatran at therapeutic doses, there have been in vitro reports of elevated INRs with supratherapeutic dabigatran levels.2,3 At a typical peak therapeutic dabigatran concentration of approximately 184 ng/mL, the INR generally ranged from 1.1 to 1.7.2 However, at a dabigatran concentration of 1000 ng/mL, the INR was elevated to 4.5,2,3 which is the same venipuncture INR recorded in our patient. While there have been published reports of falsely elevated point-of-care INR results compared to corresponding venipuncture INR results in patients taking dabigatran,4,5 a literature review found only a case of an elevated venipuncture INR in an end-stage renal disease patient receiving hemodialysis.6

In the case noted above, as well as our patient, an accumulation of dabigatran due to the patient’s renal dysfunction likely resulted in high plasma concentrations and therefore an elevated venipuncture INR. The elimination half-life for dabigatran is approximately 14 hours in patients with normal renal function; in a patient with severe renal impairment, the half-life can be up to 28 hours.7 Our patient’s CrCl at the time of presentation was 30.2 mL/min, which indicated moderate to severe renal dysfunction. Based on dabigatran prescribing recommendations, a dose adjustment to 75 mg bid might be appropriate.1 (Our patient was taking 150 mg bid.)

We do not believe our patient’s elevated INR was due to her liver transplant because there were no clinical signs of liver dysfunction. A more likely contributing factor was a drug interaction with tacrolimus. Dabigatran is a moderate affinity P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate and tacrolimus is both a P-gp substrate and inhibitor. While an interaction between tacrolimus and dabigatran has not been studied directly, concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl: 15-30 mL/min).1 For these theoretical interactions, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) has been developed.8 In our patient’s case, the calculated DIPS score of 5 suggests a probable interaction, likely due to P-gp inhibition. The other medications our patient was taking did not have this interaction and were unlikely to contribute to the elevated INR and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Our patient was instructed to stop taking dabigatran and return in 3 days for additional lab tests. At her follow-up visit, the lab results were PTT, 34.3 seconds; PT, 11.6 seconds; and venipuncture INR, 1.1. Her CBC was unremarkable and unchanged. Shortly after the follow-up visit, our patient was assessed by her cardiologist. Due to her renal dysfunction, risk of bleeding, and relatively low CHADS2 score, the cardiologist decided to discontinue dabigatran and start her on aspirin.

THE TAKEAWAY

Dabigatran may cause elevated INR levels in patients with renal dysfunction and/or those taking other medications that could interact with dabigatran. Concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor (such as tacrolimus) and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Despite the lack of required routine laboratory monitoring, renal function and drug interactions associated with dabigatran therapy should be monitored closely.

1. Praxada [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

2. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

3. Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, et al; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371-378.

4. Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e40.

5. van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-ofcare INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125:417-420.

6. Kim J, Yadava M, An IC, et al. Coagulopathy and extremely elevated PT/INR after dabigatran etexilate use in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:131395.

7. Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259-268.

8. Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674-680.

1. Praxada [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

2. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

3. Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, et al; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371-378.

4. Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e40.

5. van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-ofcare INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125:417-420.

6. Kim J, Yadava M, An IC, et al. Coagulopathy and extremely elevated PT/INR after dabigatran etexilate use in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:131395.

7. Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259-268.

8. Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674-680.

Genitourinary manifestations of sickle cell disease

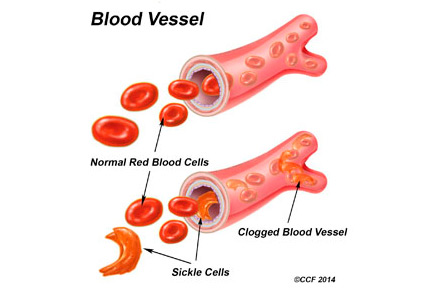

Sickle cell disease is a common genetic disorder in the United States that disproportionately affects people of African ancestry. The characteristic sickling of red blood cells under conditions of reduced oxygen tension leads to intravascular hemolysis and vaso-occlusive events, which in turn cause tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury affecting multiple organs, including the genitourinary system.1–3

In this paper, we review the genitourinary effects of sickle cell disease, focusing on sickle cell nephropathy, priapism, and renal medullary carcinoma.

THE WIDE-RANGING EFFECTS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

In the United States, sickle cell disease affects 1 of every 500 blacks and 1 of every 36,000 Hispanics.1 The term describes hemoglobinopathies associated with sickling of red blood cells.

Sickling of red blood cells results from a single base-pair change in the beta-globin gene from glutamic acid to valine at position 6, causing abnormal hemoglobin (hemoglobin S), which polymerizes under conditions of reduced oxygen tension and alters the biconcave disk shape into a rigid, irregular, unstable cell. The sickle-shaped cells are prone to intravascular hemolysis,2 causing intermittent vaso-occlusive events that result in tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Genitourinary problems include impaired ability to concentrate urine, hematuria, renal medullary carcinoma, and increased frequency of urinary tract infection.

SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY

The kidney is one of the most frequently affected organs in sickle cell disease. Renal manifestations begin to appear in early childhood, with impaired medullary concentrating ability and ischemic damage to the tubular cells caused by sickling within the vasa recta renis precipitated by the acidic, hypoxic, and hypertonic environment in the renal medulla.

As in early diabetic nephropathy, renal blood flow is enhanced and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is increased. Increased cardiac output as a result of anemia, localized release of prostaglandins, and a hypoxia-induced increase in nitric oxide synthesis all play a role in the increase in GFR.4,5

Oxidative stress, an increase in markers of inflammation, and local activation of the renin-angiotensin system contribute to renal damage in sickle cell disease.5–7 The resulting hyperfiltration injury leads to microalbuminuria, which occurs in 20% to 40% of children with sickle cell anemia8,9 and in as many as 60% of adults.

The glomerular lesions associated with sickle cell disease vary from glomerulopathy in the early stages to secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy.10

Clinical presentations and workup

Clinical presentations are not limited to glomerular disease but include hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia resulting from defects in potassium secretion and renal acidification.

Hyperphosphatemia—a result of increased reabsorption of phosphorus, increased secretion of uric acid, and increased creatinine clearance—is seen in patients with sickle cell disease.11,12 About 10% of patients can develop an acute kidney injury as a result of volume depletion, rhabdomyolysis, renal vein thrombosis, papillary necrosis, and urinary tract obstruction secondary to blood clots.11,13

Up to 30% of adult patients with sickle cell disease develop chronic kidney disease. Predictors include severe anemia, hypertension, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and microscopic hematuria.14 From 4% to 12% of patients go on to develop end-stage renal disease, but with a 1-year mortality rate three times higher than in patients without sickle cell disease.15

In general, patients with sickle cell anemia have blood pressures below those of age- and sex-matched individuals, but elevated blood pressure and low GFR are not uncommon in affected children. In a cohort of 48 children ages 3 to 18, 8.3% had an estimated GFR less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 16.7% had elevated blood pressure (prehypertension and hypertension).16

In patients with sickle cell disease, evaluation of proteinuria, hematuria, hypertension, and renal failure should take into consideration the unique renal physiologic and pathologic processes involved. Recent evidence17,18 suggests that the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation provides a better estimate of GFR than the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations, although all three creatinine-based methods overestimate GFR in patients with sickle cell disease when compared with GFR measured with technetium-99m-labeled diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid renal scanning.

Treatment options

Treatment of sickle cell nephropathy includes adequate fluid intake (given the loss of concentrating ability), adequate blood pressure control, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have microalbuminuria or proteinuria (or both)9,11,19 and hydroxyurea. Treatment with enalapril has been shown to decrease proteinuria in patients with sickle cell nephropathy.9 In a cohort of children with sickle cell disease, four of nine patients treated with an ACE inhibitor developed hyperkalemia, leading to discontinuation of the drug in three patients.9

ACE inhibitors and ARBs must be used cautiously in these patients because they have defects in potassium secretion. Hydroxyurea has also been shown to decrease hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria in recent studies,20,21 and this could protect against the development of overt nephropathy.

Higher mortality rates have been reported in patients with sickle cell disease who developed end-stage renal disease than in patients with end-stage renal disease without sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease also increases the risk of pulmonary hypertension and the vaso-occlusive complication known as acute chest syndrome, contributing to increased mortality rates. Of note, in a study that looked at the association between mortality rates and pre-end-stage care of renal disease using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, patients with sickle cell disease who had had predialysis nephrology care had lower mortality rates.15

Treatments for end-stage renal disease are also effective in patients with sickle cell disease and include hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and renal transplantation. Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing show that from 2000 to 2011, African American kidney recipients with sickle cell disease had better survival rates than patients who had undergone transplantation from 1988 to 1999, although rates of long-term survival and graft survival were lower than in transplant recipients with other diagnoses.22

It is important to note that complications as a result of vaso-occlusive events and thrombosis can lead to graft loss; therefore, sickle cell crisis after transplantation requires careful management.

Take-home messages

- Loss of urine-concentrating ability and hyperfiltration are the earliest pathologic changes in sickle cell disease.

- Microalbuminuria as seen in diabetic nephropathy is the earliest manifestation of sickle cell nephropathy, and the prevalence increases as these patients get older and live longer.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be used with caution, given the heightened risk of hyperkalemia in sickle cell disease.

- Recent results with hydroxyurea in decreasing hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria are encouraging.

- Early referral for predialysis nephrologic care is needed in sickle cell patients with chronic kidney disease.

PRIAPISM IN SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Priapism was formerly defined as a full, painful erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm. But priapism is now recognized as two separate disorders—ischemic (veno-occlusive, low-flow) priapism and nonischemic (arterial, high-flow) priapism. The new definition includes both disorders: ie, a full or partial erection lasting more than 4 hours and unrelated to sexual stimulation or orgasm.

Ischemic priapism

Hematologic disorders are major contributors to ischemic priapism and include sickle cell disease, multiple myeloma, fat emboli (hyperalimentation),23 glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and hemoglobin Olmsted variant.24

Ischemic priapism is often seen in sickle cell disease and is considered an emergency. It is characterized by an abnormally rigid erection not involving the glans penis. Entrapment of blood in the corpora cavernosa leads to hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis, which in turn leads to a painful compartment syndrome that, if untreated, results in smooth muscle necrosis and subsequent fibrosis. The results are a smaller penis and erectile dysfunction that is unresponsive to any treatment other than implantation of a penile prosthesis. However, scarring of the corpora cavernosa can make this procedure exceedingly difficult, requiring advanced techniques such as corporeal excavation.25

Men with a subtype of ischemic priapism called “stuttering” priapism26 suffer recurrent prolonged erections during sleep. The patient awakens with a painful erection that usually subsides, but sometimes only after several hours. Patients with this disorder suffer from sleep deprivation. Stuttering priapism may lead to full-blown ischemic priapism that does not resolve without intervention.

Nonischemic priapism

In nonischemic priapism, the corpora are engorged but not rigid. The condition results from unregulated arterial inflow and thus is not painful and does not result in damage to the corporeal smooth muscle.

Most cases of nonischemic priapism follow blunt perineal trauma or trauma associated with needle insertion into the corpora. This form of priapism is not associated with sickle cell disease. Because tissue damage does not occur, nonischemic or arterial priapism is not considered an emergency.

Treatment guidelines

Differentiating ischemic from nonischemic priapism is usually straightforward, based on the history, physical examination, corporeal blood gases, and duplex ultrasonography.27

Ischemic priapism is an emergency. After needle aspiration of blood from the corpora cavernosa, phenylephrine is diluted with normal saline to a concentration of 100 to 500 µg/mL and is injected in 1-mL amounts repeatedly at 3- to 5-minute intervals until the erection subsides or until a 1-hour time limit is reached. Blood pressure and pulse are monitored during these injections. If aspiration and phenylephrine irrigation fail, surgical shunting is performed.27

Measures to treat sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions) may be employed simultaneously but should never delay aspiration and phenylephrine injections.25

As nonischemic priapism is not considered an emergency, management begins with observation. Patients eventually become dissatisfied with their constant partial erection, and they then present for treatment. Most cases resolve after selective catheterization of the internal pudendal artery and embolization of the fistula with absorbable material. If this fails, surgical exploration with ligation of the vessels leading to the fistula is indicated.

Prevalence in sickle cell trait vs sickle cell disease

Ischemic priapism is uncommon in men with sickle cell trait, but prevalence rates in men with sickle cell disease are as high as 42%.28 In a study of 130 men with sickle cell disease, 35% had a history of prolonged ischemic priapism, 72% had a history of stuttering priapism, and 75% of men with stuttering priapism had their first episode before age 20.29

Rates of erectile dysfunction increase with the duration of ischemic episodes and range from 20% to 90%.28,30 In childhood, sickle cell disease accounts for 63% of the cases of ischemic priapism, and in adults it accounts for 23% of cases.31

Take-home messages

- Sickle cell disease accounts for two-thirds of cases of ischemic priapism in children, and one-fourth of adult cases.

- Ischemic priapism is a medical emergency.

- Treatment with aspiration and phenylephrine injections should begin immediately and should not await treatment measures for sickle cell disease (hydration, oxygen, exchange transfusions).

OTHER UROLOGIC COMPLICATIONS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Other urologic complications of sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease include microscopic hematuria, gross hematuria, and renal colic. A formal evaluation of any patient with persistent microscopic hematuria or gross hematuria should consist of urinalysis, computed tomography, and cystoscopy. This approach assesses the upper and lower genitourinary system for treatable causes. Renal ultrasonography can be used instead of computed tomography but tends to provide less information.

Special considerations

In patients with sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease, chronic hypoxia and subsequent sickling of erythrocytes in the renal medulla can lead to papillary hypertrophy and papillary necrosis. In papillary hypertrophy, friable blood vessels can rupture, resulting in microscopic and gross hematuria. In papillary necrosis, the papilla can slough off and become lodged in the ureter.

Nevertheless, hematuria and renal colic in patients with sickle cell disease or trait are most often attributable to common causes such as infection and stones. A finding of hydronephrosis in the absence of a stone, however, suggests obstruction due to a clot or a sloughed papilla. Ureteroscopy, fulguration, and ureteral stent placement can stop the bleeding and alleviate obstruction in these cases.

Renal medullary carcinoma

Another important reason to order imaging in patients with sickle cell disease or trait who present with urologic symptoms is to rule out renal medullary carcinoma, a rare but aggressive cancer that arises from the collecting duct epithelium. This cancer is twice as likely to occur in males than in females; it has been reported in patients ranging in age from 10 to 40, with a median age at presentation of 26.32

When patients present with symptomatic renal medullary cancer, in most cases the cancer has already metastasized.

On computed tomography, the tumor tends to occupy a central location in the kidney and appears to infiltrate and replace adjacent kidney tissue. Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and metastasis are common.

Treatment typically entails radical nephrectomy, chemotherapy, and in some circumstances, radiotherapy. Case reports have shown promising tumor responses to carboplatin and paclitaxel regimens.33,34 Also, a low threshold for imaging in patients with sickle cell disease and trait may increase the odds of early detection of this aggressive cancer.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sickle cell disease (SCD). Data and statistics. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- Paulin L, Itano HA, Singer SJ, Wells IC. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science 1949; 110:543–548.

- Powars DR, Chan LS, Hiti A, Ramicone E, Johnson C. Outcome of sickle cell anemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005; 84:363–376.

- Haymann JP, Stankovic K, Levy P, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in adult sickle cell anemia: a frequent hemolysis associated feature. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:756–761.

- da Silva GB Jr, Libório AB, Daher Ede F. New insights on pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of sickle cell nephropathy. Ann Hematol 2011; 90:1371–1379.

- Emokpae MA, Uadia PO, Gadzama AA. Correlation of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers with the severity of sickle cell nephropathy. Ann Afr Med 2010; 9:141–146.

- Chirico EN, Pialoux V. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. IUBMB Life 2012; 64:72–80.

- Datta V, Ayengar JR, Karpate S, Chaturvedi P. Microalbuminuria as a predictor of early glomerular injury in children with sickle cell disease. Indian J Pediatr 2003; 70:307–309.

- Falk RJ, Scheinman J, Phillips G, Orringer E, Johnson A, Jennette JC. Prevalence and pathologic features of sickle cell nephropathy and response to inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:910–915.

- Maigne G, Ferlicot S, Galacteros F, et al. Glomerular lesions in patients with sickle cell disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010; 89:18–27.

- Sharpe CC, Thein SL. Sickle cell nephropathy—a practical approach. Br J Haematol 2011; 155:287–297.

- Batlle D, Itsarayoungyuen K, Arruda JA, Kurtzman NA. Hyperkalemic hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis in sickle cell hemoglobinopathies. Am J Med 1982; 72:188–192.

- Sklar AH, Perez JC, Harp RJ, Caruana RJ. Acute renal failure in sickle cell anemia. Int J Artif Organs 1990; 13:347–351.

- Powars DR, Elliott-Mills DD, Chan L, et al. Chronic renal failure in sickle cell disease: risk factors, clinical course, and mortality. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:614–620.

- McClellan AC, Luthi JC, Lynch JR, et al. High one year mortality in adults with sickle cell disease and end-stage renal disease. Br J Haematol 2012; 159:360–367.

- Bodas P, Huang A, O Riordan MA, Sedor JR, Dell KM. The prevalence of hypertension and abnormal kidney function in children with sickle cell disease—a cross sectional review. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14:237.

- Asnani MR, Lynch O, Reid ME. Determining glomerular filtration rate in homozygous sickle cell disease: utility of serum creatinine based estimating equations. PLoS One 2013; 8:e69922.

- Arlet JB, Ribeil JA, Chatellier G, et al. Determination of the best method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine in adult patients with sickle cell disease: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13:83.

- McKie KT, Hanevold CD, Hernandez C, Waller JL, Ortiz L, McKie KM. Prevalence, prevention, and treatment of microalbuminuria and proteinuria in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2007; 29:140–144.

- Laurin LP, Nachman PH, Desai PC, Ataga KI, Derebail VK. Hydroxyurea is associated with lower prevalence of albuminuria in adults with sickle cell disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29:1211–1218.

- Aygun B, Mortier NA, Smeltzer MP, Shulkin BL, Hankins JS, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea treatment decreases glomerular hyperfiltration in children with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol 2013; 88:116–119.

- Huang E, Parke C, Mehrnia A, et al. Improved survival among sickle cell kidney transplant recipients in the recent era. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28:1039–1046.

- Klein EA, Montague DK, Steiger E. Priapism associated with the use of intravenous fat emulsion: case reports and postulated pathogenesis. J Urol May 1985; 133:857–859.

- Thuret I, Bardakdjian J, Badens C, et al. Priapism following splenectomy in an unstable hemoglobin: hemoglobin Olmsted beta 141 (H19) Leu-->Arg. Am J Hematol 1996; 51:133–136.

- Montague DK, Angermeier KW. Corporeal excavation: new technique for penile prosthesis implantation in men with severe corporeal fibrosis. Urology 2006; 67:1072–1075.

- Levey HR, Kutlu O, Bivalacqua TJ. Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature. Asian J Androl 2012; 14:156–163.

- Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al; Members of the Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel; American Urological Association. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol 2003; 170:1318–1324.

- Emond AM, Holman R, Hayes RJ, Serjeant GR. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140:1434–1437.

- Adeyoju AB, Olujohungbe AB, Morris J, et al. Priapism in sickle-cell disease; incidence, risk factors and complications—an international multicentre study. BJU Int 2002; 90:898–902.

- Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med 2004; 1:116–120.

- Nelson JH, 3rd, Winter CC. Priapism: evolution of management in 48 patients in a 22-year series. J Urol 1977; 117:455–458.

- Liu Q, Galli S, Srinivasan R, Linehan WM, Tsokos M, Merino MJ. Renal medullary carcinoma: molecular, immunohistochemistry, and morphologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37:368–374.

- Gangireddy VG, Liles GB, Sostre GD, Coleman T. Response of metastatic renal medullary carcinoma to carboplatinum and Paclitaxel chemotherapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2012; 10:134–139.

- Walsh AM, Fiveash JB, Reddy AT, Friedman GK. Response to radiation in renal medullary carcinoma. Rare Tumors 2011; 3:e32.

Sickle cell disease is a common genetic disorder in the United States that disproportionately affects people of African ancestry. The characteristic sickling of red blood cells under conditions of reduced oxygen tension leads to intravascular hemolysis and vaso-occlusive events, which in turn cause tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury affecting multiple organs, including the genitourinary system.1–3

In this paper, we review the genitourinary effects of sickle cell disease, focusing on sickle cell nephropathy, priapism, and renal medullary carcinoma.

THE WIDE-RANGING EFFECTS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

In the United States, sickle cell disease affects 1 of every 500 blacks and 1 of every 36,000 Hispanics.1 The term describes hemoglobinopathies associated with sickling of red blood cells.

Sickling of red blood cells results from a single base-pair change in the beta-globin gene from glutamic acid to valine at position 6, causing abnormal hemoglobin (hemoglobin S), which polymerizes under conditions of reduced oxygen tension and alters the biconcave disk shape into a rigid, irregular, unstable cell. The sickle-shaped cells are prone to intravascular hemolysis,2 causing intermittent vaso-occlusive events that result in tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Genitourinary problems include impaired ability to concentrate urine, hematuria, renal medullary carcinoma, and increased frequency of urinary tract infection.

SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY

The kidney is one of the most frequently affected organs in sickle cell disease. Renal manifestations begin to appear in early childhood, with impaired medullary concentrating ability and ischemic damage to the tubular cells caused by sickling within the vasa recta renis precipitated by the acidic, hypoxic, and hypertonic environment in the renal medulla.

As in early diabetic nephropathy, renal blood flow is enhanced and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is increased. Increased cardiac output as a result of anemia, localized release of prostaglandins, and a hypoxia-induced increase in nitric oxide synthesis all play a role in the increase in GFR.4,5

Oxidative stress, an increase in markers of inflammation, and local activation of the renin-angiotensin system contribute to renal damage in sickle cell disease.5–7 The resulting hyperfiltration injury leads to microalbuminuria, which occurs in 20% to 40% of children with sickle cell anemia8,9 and in as many as 60% of adults.

The glomerular lesions associated with sickle cell disease vary from glomerulopathy in the early stages to secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy.10

Clinical presentations and workup

Clinical presentations are not limited to glomerular disease but include hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia resulting from defects in potassium secretion and renal acidification.

Hyperphosphatemia—a result of increased reabsorption of phosphorus, increased secretion of uric acid, and increased creatinine clearance—is seen in patients with sickle cell disease.11,12 About 10% of patients can develop an acute kidney injury as a result of volume depletion, rhabdomyolysis, renal vein thrombosis, papillary necrosis, and urinary tract obstruction secondary to blood clots.11,13

Up to 30% of adult patients with sickle cell disease develop chronic kidney disease. Predictors include severe anemia, hypertension, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, and microscopic hematuria.14 From 4% to 12% of patients go on to develop end-stage renal disease, but with a 1-year mortality rate three times higher than in patients without sickle cell disease.15

In general, patients with sickle cell anemia have blood pressures below those of age- and sex-matched individuals, but elevated blood pressure and low GFR are not uncommon in affected children. In a cohort of 48 children ages 3 to 18, 8.3% had an estimated GFR less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and 16.7% had elevated blood pressure (prehypertension and hypertension).16

In patients with sickle cell disease, evaluation of proteinuria, hematuria, hypertension, and renal failure should take into consideration the unique renal physiologic and pathologic processes involved. Recent evidence17,18 suggests that the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation provides a better estimate of GFR than the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations, although all three creatinine-based methods overestimate GFR in patients with sickle cell disease when compared with GFR measured with technetium-99m-labeled diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid renal scanning.

Treatment options

Treatment of sickle cell nephropathy includes adequate fluid intake (given the loss of concentrating ability), adequate blood pressure control, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have microalbuminuria or proteinuria (or both)9,11,19 and hydroxyurea. Treatment with enalapril has been shown to decrease proteinuria in patients with sickle cell nephropathy.9 In a cohort of children with sickle cell disease, four of nine patients treated with an ACE inhibitor developed hyperkalemia, leading to discontinuation of the drug in three patients.9

ACE inhibitors and ARBs must be used cautiously in these patients because they have defects in potassium secretion. Hydroxyurea has also been shown to decrease hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria in recent studies,20,21 and this could protect against the development of overt nephropathy.