User login

ILC: Direct Antivirals Safely Clear HCV Despite ESRD

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

ILC: Direct antivirals safely clear HCV despite ESRD

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: The trio of direct antiviral agents marketed as Viekira Pak safely eradicated chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C infection in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: All 10 patients followed so far to at least 4 weeks after completing treatment maintained a sustained virologic response.

Data source: RUBY-1, an open-label series of 20 patients with chronic HCV and advanced chronic kidney disease.

Disclosures: RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

Avoiding metformin in renal insufficiency

A 47-year-old obese male with type 2 diabetes has been on metformin for the last 2 years with good effect (hemoglobin A1c of 6.8), and with exercise has been able to lose 5-10 pounds. His last two blood tests show creatinine levels of 1.5 and 1.6. What do you recommend?

A) Continue with metformin.

B) Stop metformin, start sulfonylurea.

C) Stop metformin, begin glargine.

D) Stop metformin, begin pioglitazone.

Myth: Metformin should not be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is the most commonly used oral agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States, but the FDA-approved drug label states that it is contraindicated in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance or serum creatinine of 1.4 in women and 1.5 in men.<sup/>The concern is for development of lactic acidosis in patients because the renally excreted metformin may build up as a result of decreased renal function.

Metformin was approved for use in the United States in 1995, many years after the drug was introduced in Europe. The first drug in its class, phenformin, was removed from the United States and most European markets in 1977 because of a high incidence of lactic acidosis occurring at therapeutic doses. One in 4,000 patients taking phenformin develops lactic acidosis (J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16:881-6). Phenformin has been shown to cause type B lactic acidosis, without evidence of hypoxia or hypoperfusion, and lactic acidosis because of phenformin carried a 50% mortality rate.

Deep concern for the possibility of a similar problem with metformin played an important role in its delay of availability in the United States. It isn’t clear, however, that diabetes patients on metformin have a higher risk of developing lactic acidosis than diabetes patients who are not on metformin.

A Cochrane review of 347 studies, including 70,490 person-years of metformin use, compared with 55,451 person-years in the nonmetformin group, showed no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in either group (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Apr 14:CD002967). More than half the studies included (53%) allowed for the inclusion of patients with creatinine levels greater than 1.5. There were no differences in lactate levels between metformin-treated patients and patients who did not receive metformin.

In a study using the Saskatchewan Health administrative database, which involved 11,797 patients with 22,296 years of metformin exposure, there were two cases of lactic acidosis (Diabetes Care 1999;22:925-7). This calculates to a rate of 9 cases per 100,000 person years, the same rate as in patients with diabetes who are not taking metformin (9.7 cases per 100,000) (Diabetes Care 1998;21:1659-63).

A recent study looked at the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin with and without abnormalities in renal function (Diabetes Care 2014;37:2291-5). There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of lactic acidosis in patients who were on metformin with normal renal function, compared with those with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. The overall rate of lactic acidosis was 10.3 per 100,000 patient years, which is almost identical to the rates in the other studies mentioned, and there were no fatalities.

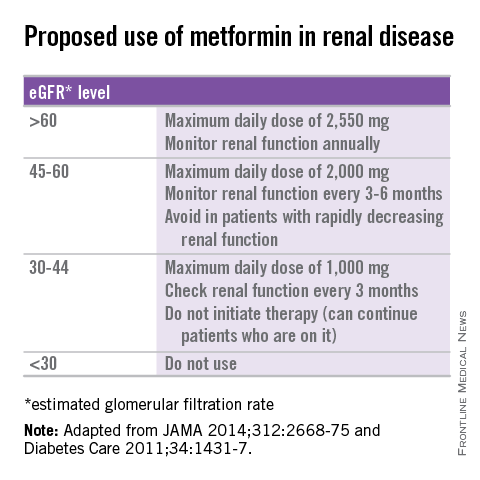

Several recommendations for using metformin in patients with renal insufficiency have been published (see table) (JAMA 2014;312:2668-75; Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431-7). Metformin has shown cardiovascular mortality benefits, compared with sulfonylureas, in the treatment of diabetes (Diabetes Care 2013;36:1304-11). Avoiding its use in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency in favor of other treatments that may not be as beneficial and may well lead to worse outcomes.

There is no evidence that metformin increases the lactic acidosis risk in patients with diabetes, but until there is a change in the FDA labeling, physicians will likely continue to be hesitant to use it in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 47-year-old obese male with type 2 diabetes has been on metformin for the last 2 years with good effect (hemoglobin A1c of 6.8), and with exercise has been able to lose 5-10 pounds. His last two blood tests show creatinine levels of 1.5 and 1.6. What do you recommend?

A) Continue with metformin.

B) Stop metformin, start sulfonylurea.

C) Stop metformin, begin glargine.

D) Stop metformin, begin pioglitazone.

Myth: Metformin should not be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is the most commonly used oral agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States, but the FDA-approved drug label states that it is contraindicated in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance or serum creatinine of 1.4 in women and 1.5 in men.<sup/>The concern is for development of lactic acidosis in patients because the renally excreted metformin may build up as a result of decreased renal function.

Metformin was approved for use in the United States in 1995, many years after the drug was introduced in Europe. The first drug in its class, phenformin, was removed from the United States and most European markets in 1977 because of a high incidence of lactic acidosis occurring at therapeutic doses. One in 4,000 patients taking phenformin develops lactic acidosis (J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16:881-6). Phenformin has been shown to cause type B lactic acidosis, without evidence of hypoxia or hypoperfusion, and lactic acidosis because of phenformin carried a 50% mortality rate.

Deep concern for the possibility of a similar problem with metformin played an important role in its delay of availability in the United States. It isn’t clear, however, that diabetes patients on metformin have a higher risk of developing lactic acidosis than diabetes patients who are not on metformin.

A Cochrane review of 347 studies, including 70,490 person-years of metformin use, compared with 55,451 person-years in the nonmetformin group, showed no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in either group (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Apr 14:CD002967). More than half the studies included (53%) allowed for the inclusion of patients with creatinine levels greater than 1.5. There were no differences in lactate levels between metformin-treated patients and patients who did not receive metformin.

In a study using the Saskatchewan Health administrative database, which involved 11,797 patients with 22,296 years of metformin exposure, there were two cases of lactic acidosis (Diabetes Care 1999;22:925-7). This calculates to a rate of 9 cases per 100,000 person years, the same rate as in patients with diabetes who are not taking metformin (9.7 cases per 100,000) (Diabetes Care 1998;21:1659-63).

A recent study looked at the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin with and without abnormalities in renal function (Diabetes Care 2014;37:2291-5). There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of lactic acidosis in patients who were on metformin with normal renal function, compared with those with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. The overall rate of lactic acidosis was 10.3 per 100,000 patient years, which is almost identical to the rates in the other studies mentioned, and there were no fatalities.

Several recommendations for using metformin in patients with renal insufficiency have been published (see table) (JAMA 2014;312:2668-75; Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431-7). Metformin has shown cardiovascular mortality benefits, compared with sulfonylureas, in the treatment of diabetes (Diabetes Care 2013;36:1304-11). Avoiding its use in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency in favor of other treatments that may not be as beneficial and may well lead to worse outcomes.

There is no evidence that metformin increases the lactic acidosis risk in patients with diabetes, but until there is a change in the FDA labeling, physicians will likely continue to be hesitant to use it in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 47-year-old obese male with type 2 diabetes has been on metformin for the last 2 years with good effect (hemoglobin A1c of 6.8), and with exercise has been able to lose 5-10 pounds. His last two blood tests show creatinine levels of 1.5 and 1.6. What do you recommend?

A) Continue with metformin.

B) Stop metformin, start sulfonylurea.

C) Stop metformin, begin glargine.

D) Stop metformin, begin pioglitazone.

Myth: Metformin should not be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is the most commonly used oral agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States, but the FDA-approved drug label states that it is contraindicated in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance or serum creatinine of 1.4 in women and 1.5 in men.<sup/>The concern is for development of lactic acidosis in patients because the renally excreted metformin may build up as a result of decreased renal function.

Metformin was approved for use in the United States in 1995, many years after the drug was introduced in Europe. The first drug in its class, phenformin, was removed from the United States and most European markets in 1977 because of a high incidence of lactic acidosis occurring at therapeutic doses. One in 4,000 patients taking phenformin develops lactic acidosis (J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16:881-6). Phenformin has been shown to cause type B lactic acidosis, without evidence of hypoxia or hypoperfusion, and lactic acidosis because of phenformin carried a 50% mortality rate.

Deep concern for the possibility of a similar problem with metformin played an important role in its delay of availability in the United States. It isn’t clear, however, that diabetes patients on metformin have a higher risk of developing lactic acidosis than diabetes patients who are not on metformin.

A Cochrane review of 347 studies, including 70,490 person-years of metformin use, compared with 55,451 person-years in the nonmetformin group, showed no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in either group (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Apr 14:CD002967). More than half the studies included (53%) allowed for the inclusion of patients with creatinine levels greater than 1.5. There were no differences in lactate levels between metformin-treated patients and patients who did not receive metformin.

In a study using the Saskatchewan Health administrative database, which involved 11,797 patients with 22,296 years of metformin exposure, there were two cases of lactic acidosis (Diabetes Care 1999;22:925-7). This calculates to a rate of 9 cases per 100,000 person years, the same rate as in patients with diabetes who are not taking metformin (9.7 cases per 100,000) (Diabetes Care 1998;21:1659-63).

A recent study looked at the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin with and without abnormalities in renal function (Diabetes Care 2014;37:2291-5). There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of lactic acidosis in patients who were on metformin with normal renal function, compared with those with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. The overall rate of lactic acidosis was 10.3 per 100,000 patient years, which is almost identical to the rates in the other studies mentioned, and there were no fatalities.

Several recommendations for using metformin in patients with renal insufficiency have been published (see table) (JAMA 2014;312:2668-75; Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431-7). Metformin has shown cardiovascular mortality benefits, compared with sulfonylureas, in the treatment of diabetes (Diabetes Care 2013;36:1304-11). Avoiding its use in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency in favor of other treatments that may not be as beneficial and may well lead to worse outcomes.

There is no evidence that metformin increases the lactic acidosis risk in patients with diabetes, but until there is a change in the FDA labeling, physicians will likely continue to be hesitant to use it in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Acute Kidney Injury: Prevalent in Sugarcane Harvesters

Q) I’ve heard a lot of talk about all the kidney problems that the sugarcane workers in Central America have. Does anyone know why this is happening?

The unusually high rates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among sugarcane workers in Central America have been a subject of great interest since National Public Radio (NPR) aired a special on this topic.3 There has been a rising epidemic of CKD in otherwise healthy male farm workers (ages 20 to 50), particularly those who harvest sugarcane.4,5 It has been hypothesized that recurrent episodes of acute kidney injury (AKI)—related to dehydration, volume depletion, pollutants, and rhabdomyolysis with inflammatory stress—are the underlying cause.5

Sugarcane harvesters typically work nine-hour days, six days per week, in extremely high temperatures and while wearing heavy, hot clothing. Each worker cuts approximately 10 tons of sugarcane daily, since they are paid based on cutting volume. Workers drink between five and 10 L of water during their shifts.

Santos et al designed a study to prospectively examine the effects of burnt sugarcane harvesting on renal function in healthy male farm workers. Twenty-eight men (ages 19 to 39) with no CKD risk factors (diabetes, smoking, obesity, hypertension, illicit drug or alcohol use) were followed for eight months from preharvest to postharvest. Blood samples were collected at the beginning and at the end of the workday and preharvest and postharvest season.5

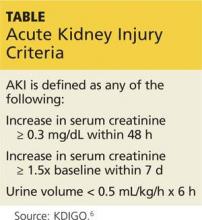

Preseason lab values were normal in all 28 men. But postseason, all workers had elevated creatinine levels, with five meeting the criteria for AKI (see Table at left).5,6

Santos and colleagues identified potential causes for AKI in this population. These included

• Dehydration and volume depletion (episodes of tachycardia, increased urine density, lower urinary/serum sodium, higher hematocrit)

• Rhabdomyolysis (increased creatine kinase at the end of each workday)

• Systemic inflammation (increased white blood count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes during the workday—possibly indicative of an inflammatory burst)

• Other factors (burning of the sugarcane releasing unknown nephrotoxic substances; unreported NSAIDs use)5

Compared to workers who showed early signs of CKD, those who developed frank AKI were more likely to have hyponatremia. Recommendations to reduce the problem include consumption of water/salt hydrating drinks, use of appropriate clothing, work-hour limitations, and changes to payment structures (ie, from a volume system to an hourly or daily system). Furthermore, education on the need to avoid alcohol, illicit drugs, and NSAIDs during the harvest season should help to decrease incidence of AKI among these workers.

Elizabeth C. Evans, RN, MSN, CNP, DNP

Renal Medicine Associates, Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFERENCES

1. Ayuk J, Gittoes N. Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51(Pt 2):179-188.

2. Firouzi A, Maadani M, Kiani R, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulfate: new method in prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(3):521-525.

3. Beaubien J. Mysterious kidney disease slays farm workers in central America. National Public Radio; 2014. www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/04/30/306907097/mysterious-kidney-disease-slays-farmworkers-in-central-america. Accessed April 1, 2015.

4. Almaguer M, Herrera R, Orantes CM. Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in agricultural communities. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16(2):9-15.

5. Santos UP, Zanetta DMT, Burdmann EA. Burnt sugarcane harvesting is associated with acute renal dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2015;87(4):792-799.

6. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1-138.

Q) I’ve heard a lot of talk about all the kidney problems that the sugarcane workers in Central America have. Does anyone know why this is happening?

The unusually high rates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among sugarcane workers in Central America have been a subject of great interest since National Public Radio (NPR) aired a special on this topic.3 There has been a rising epidemic of CKD in otherwise healthy male farm workers (ages 20 to 50), particularly those who harvest sugarcane.4,5 It has been hypothesized that recurrent episodes of acute kidney injury (AKI)—related to dehydration, volume depletion, pollutants, and rhabdomyolysis with inflammatory stress—are the underlying cause.5

Sugarcane harvesters typically work nine-hour days, six days per week, in extremely high temperatures and while wearing heavy, hot clothing. Each worker cuts approximately 10 tons of sugarcane daily, since they are paid based on cutting volume. Workers drink between five and 10 L of water during their shifts.

Santos et al designed a study to prospectively examine the effects of burnt sugarcane harvesting on renal function in healthy male farm workers. Twenty-eight men (ages 19 to 39) with no CKD risk factors (diabetes, smoking, obesity, hypertension, illicit drug or alcohol use) were followed for eight months from preharvest to postharvest. Blood samples were collected at the beginning and at the end of the workday and preharvest and postharvest season.5

Preseason lab values were normal in all 28 men. But postseason, all workers had elevated creatinine levels, with five meeting the criteria for AKI (see Table at left).5,6

Santos and colleagues identified potential causes for AKI in this population. These included

• Dehydration and volume depletion (episodes of tachycardia, increased urine density, lower urinary/serum sodium, higher hematocrit)

• Rhabdomyolysis (increased creatine kinase at the end of each workday)

• Systemic inflammation (increased white blood count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes during the workday—possibly indicative of an inflammatory burst)

• Other factors (burning of the sugarcane releasing unknown nephrotoxic substances; unreported NSAIDs use)5

Compared to workers who showed early signs of CKD, those who developed frank AKI were more likely to have hyponatremia. Recommendations to reduce the problem include consumption of water/salt hydrating drinks, use of appropriate clothing, work-hour limitations, and changes to payment structures (ie, from a volume system to an hourly or daily system). Furthermore, education on the need to avoid alcohol, illicit drugs, and NSAIDs during the harvest season should help to decrease incidence of AKI among these workers.

Elizabeth C. Evans, RN, MSN, CNP, DNP

Renal Medicine Associates, Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFERENCES

1. Ayuk J, Gittoes N. Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51(Pt 2):179-188.

2. Firouzi A, Maadani M, Kiani R, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulfate: new method in prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(3):521-525.

3. Beaubien J. Mysterious kidney disease slays farm workers in central America. National Public Radio; 2014. www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/04/30/306907097/mysterious-kidney-disease-slays-farmworkers-in-central-america. Accessed April 1, 2015.

4. Almaguer M, Herrera R, Orantes CM. Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in agricultural communities. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16(2):9-15.

5. Santos UP, Zanetta DMT, Burdmann EA. Burnt sugarcane harvesting is associated with acute renal dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2015;87(4):792-799.

6. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1-138.

Q) I’ve heard a lot of talk about all the kidney problems that the sugarcane workers in Central America have. Does anyone know why this is happening?

The unusually high rates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among sugarcane workers in Central America have been a subject of great interest since National Public Radio (NPR) aired a special on this topic.3 There has been a rising epidemic of CKD in otherwise healthy male farm workers (ages 20 to 50), particularly those who harvest sugarcane.4,5 It has been hypothesized that recurrent episodes of acute kidney injury (AKI)—related to dehydration, volume depletion, pollutants, and rhabdomyolysis with inflammatory stress—are the underlying cause.5

Sugarcane harvesters typically work nine-hour days, six days per week, in extremely high temperatures and while wearing heavy, hot clothing. Each worker cuts approximately 10 tons of sugarcane daily, since they are paid based on cutting volume. Workers drink between five and 10 L of water during their shifts.

Santos et al designed a study to prospectively examine the effects of burnt sugarcane harvesting on renal function in healthy male farm workers. Twenty-eight men (ages 19 to 39) with no CKD risk factors (diabetes, smoking, obesity, hypertension, illicit drug or alcohol use) were followed for eight months from preharvest to postharvest. Blood samples were collected at the beginning and at the end of the workday and preharvest and postharvest season.5

Preseason lab values were normal in all 28 men. But postseason, all workers had elevated creatinine levels, with five meeting the criteria for AKI (see Table at left).5,6

Santos and colleagues identified potential causes for AKI in this population. These included

• Dehydration and volume depletion (episodes of tachycardia, increased urine density, lower urinary/serum sodium, higher hematocrit)

• Rhabdomyolysis (increased creatine kinase at the end of each workday)

• Systemic inflammation (increased white blood count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes during the workday—possibly indicative of an inflammatory burst)

• Other factors (burning of the sugarcane releasing unknown nephrotoxic substances; unreported NSAIDs use)5

Compared to workers who showed early signs of CKD, those who developed frank AKI were more likely to have hyponatremia. Recommendations to reduce the problem include consumption of water/salt hydrating drinks, use of appropriate clothing, work-hour limitations, and changes to payment structures (ie, from a volume system to an hourly or daily system). Furthermore, education on the need to avoid alcohol, illicit drugs, and NSAIDs during the harvest season should help to decrease incidence of AKI among these workers.

Elizabeth C. Evans, RN, MSN, CNP, DNP

Renal Medicine Associates, Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFERENCES

1. Ayuk J, Gittoes N. Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51(Pt 2):179-188.

2. Firouzi A, Maadani M, Kiani R, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulfate: new method in prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(3):521-525.

3. Beaubien J. Mysterious kidney disease slays farm workers in central America. National Public Radio; 2014. www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/04/30/306907097/mysterious-kidney-disease-slays-farmworkers-in-central-america. Accessed April 1, 2015.

4. Almaguer M, Herrera R, Orantes CM. Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in agricultural communities. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16(2):9-15.

5. Santos UP, Zanetta DMT, Burdmann EA. Burnt sugarcane harvesting is associated with acute renal dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2015;87(4):792-799.

6. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1-138.

Acute Kidney Injury: Magnesium for Protection

Q) Our radiology department is discussing use of IV magnesium for diabetic patients to “protect them from kidney injury.” Is this a standard of care now?

Magnesium, the fourth most abundant cation in the body, plays an important physiologic role. Balance is maintained by renal regulation of magnesium reabsorption, and deficiency occurs when there is increased renal excretion initiated by osmotic diuresis. Clinical manifestations of deficiency include cardiac arrhythmias, neuromuscular hyperexcitability, and biochemical abnormalities of hypocalcaemia and hypokalemia.

Diabetes is one of the leading causes of magnesium deficiency, with incidence ranging from 25% to 39%.1 Fluctuations in serum magnesium concentrations are directly correlated with fasting blood glucose, A1C levels, albumin excretion, and the duration of diabetes. It has been postulated that magnesium depletion, via its effect on inositol transport, is pathogenic in the progression of diabetic complications.

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is a potentially adverse consequence of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), particularly in diabetic patients. It results in significant morbidity and mortality and adds to the costs of diagnostic and interventional cardiology procedures. Intravenous (IV) agents used during radiologic imaging are notorious for causing acute kidney injury in diabetic patients. Preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of all nephrotoxic medications have proven beneficial in protecting these patients from CI-AKI.

A recent prospective, randomized, open-label clinical trial looked at the effect of administering IV magnesium prior to PCI.2 The control group underwent standard preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of nephrotoxic medications. The study group added IV magnesium to the standard protocol.

In this single-center study, 26.6% of patients in the control group and 14.5% in the study group sustained CI-AKI, a statistically significant result (P = .01). Neither group experienced mortality or required dialysis.

Although not considered standard of care at this time, prophylactic use of IV magnesium (pending pre-op labs), along with the recognized benefit of preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of nephrotoxic medications, can be supported in primary PCI patients. Your radiology department is on the cutting edge of protecting these very high-risk patients.

Debra L. Coplon, DNP, DCC

City of Memphis Wellness Clinic, Tennessee

REFERENCES

1. Ayuk J, Gittoes N. Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51(Pt 2):179-188.

2. Firouzi A, Maadani M, Kiani R, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulfate: new method in prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(3):521-525.

Q) Our radiology department is discussing use of IV magnesium for diabetic patients to “protect them from kidney injury.” Is this a standard of care now?

Magnesium, the fourth most abundant cation in the body, plays an important physiologic role. Balance is maintained by renal regulation of magnesium reabsorption, and deficiency occurs when there is increased renal excretion initiated by osmotic diuresis. Clinical manifestations of deficiency include cardiac arrhythmias, neuromuscular hyperexcitability, and biochemical abnormalities of hypocalcaemia and hypokalemia.

Diabetes is one of the leading causes of magnesium deficiency, with incidence ranging from 25% to 39%.1 Fluctuations in serum magnesium concentrations are directly correlated with fasting blood glucose, A1C levels, albumin excretion, and the duration of diabetes. It has been postulated that magnesium depletion, via its effect on inositol transport, is pathogenic in the progression of diabetic complications.

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is a potentially adverse consequence of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), particularly in diabetic patients. It results in significant morbidity and mortality and adds to the costs of diagnostic and interventional cardiology procedures. Intravenous (IV) agents used during radiologic imaging are notorious for causing acute kidney injury in diabetic patients. Preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of all nephrotoxic medications have proven beneficial in protecting these patients from CI-AKI.

A recent prospective, randomized, open-label clinical trial looked at the effect of administering IV magnesium prior to PCI.2 The control group underwent standard preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of nephrotoxic medications. The study group added IV magnesium to the standard protocol.

In this single-center study, 26.6% of patients in the control group and 14.5% in the study group sustained CI-AKI, a statistically significant result (P = .01). Neither group experienced mortality or required dialysis.

Although not considered standard of care at this time, prophylactic use of IV magnesium (pending pre-op labs), along with the recognized benefit of preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of nephrotoxic medications, can be supported in primary PCI patients. Your radiology department is on the cutting edge of protecting these very high-risk patients.

Debra L. Coplon, DNP, DCC

City of Memphis Wellness Clinic, Tennessee

REFERENCES

1. Ayuk J, Gittoes N. Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51(Pt 2):179-188.

2. Firouzi A, Maadani M, Kiani R, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulfate: new method in prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(3):521-525.

Q) Our radiology department is discussing use of IV magnesium for diabetic patients to “protect them from kidney injury.” Is this a standard of care now?

Magnesium, the fourth most abundant cation in the body, plays an important physiologic role. Balance is maintained by renal regulation of magnesium reabsorption, and deficiency occurs when there is increased renal excretion initiated by osmotic diuresis. Clinical manifestations of deficiency include cardiac arrhythmias, neuromuscular hyperexcitability, and biochemical abnormalities of hypocalcaemia and hypokalemia.

Diabetes is one of the leading causes of magnesium deficiency, with incidence ranging from 25% to 39%.1 Fluctuations in serum magnesium concentrations are directly correlated with fasting blood glucose, A1C levels, albumin excretion, and the duration of diabetes. It has been postulated that magnesium depletion, via its effect on inositol transport, is pathogenic in the progression of diabetic complications.

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) is a potentially adverse consequence of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), particularly in diabetic patients. It results in significant morbidity and mortality and adds to the costs of diagnostic and interventional cardiology procedures. Intravenous (IV) agents used during radiologic imaging are notorious for causing acute kidney injury in diabetic patients. Preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of all nephrotoxic medications have proven beneficial in protecting these patients from CI-AKI.

A recent prospective, randomized, open-label clinical trial looked at the effect of administering IV magnesium prior to PCI.2 The control group underwent standard preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of nephrotoxic medications. The study group added IV magnesium to the standard protocol.

In this single-center study, 26.6% of patients in the control group and 14.5% in the study group sustained CI-AKI, a statistically significant result (P = .01). Neither group experienced mortality or required dialysis.

Although not considered standard of care at this time, prophylactic use of IV magnesium (pending pre-op labs), along with the recognized benefit of preprocedural hydration and discontinuation of nephrotoxic medications, can be supported in primary PCI patients. Your radiology department is on the cutting edge of protecting these very high-risk patients.

Debra L. Coplon, DNP, DCC

City of Memphis Wellness Clinic, Tennessee

REFERENCES

1. Ayuk J, Gittoes N. Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2014;51(Pt 2):179-188.

2. Firouzi A, Maadani M, Kiani R, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulfate: new method in prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(3):521-525.

T cells remain best urinary biomarker for lupus nephritis

T cells are still the most accurate urinary biomarker for lupus nephritis, reported Katharina Kopetschke and her coauthors.

In a study of 123 lupus patients between April 2009 and March 2013, the area under the curve values for CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells (1.000 and 0.9969, respectively) showed better distinction of active lupus nephritis (LN) than did CD19+ B cells (0.7823), CD14+ macrophages (0.9066), and proteinuria (0.9201), Ms. Kopetschke and her colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that noninvasive urine monitoring “might become a useful tool to facilitate clinical decisions concerning kidney biopsies and treatment of LN,” the investigators said in the paper.

Read the full article in Arthritis Research & Therapy (doi:10.1186/s13075-015-0600-y).

T cells are still the most accurate urinary biomarker for lupus nephritis, reported Katharina Kopetschke and her coauthors.

In a study of 123 lupus patients between April 2009 and March 2013, the area under the curve values for CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells (1.000 and 0.9969, respectively) showed better distinction of active lupus nephritis (LN) than did CD19+ B cells (0.7823), CD14+ macrophages (0.9066), and proteinuria (0.9201), Ms. Kopetschke and her colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that noninvasive urine monitoring “might become a useful tool to facilitate clinical decisions concerning kidney biopsies and treatment of LN,” the investigators said in the paper.

Read the full article in Arthritis Research & Therapy (doi:10.1186/s13075-015-0600-y).

T cells are still the most accurate urinary biomarker for lupus nephritis, reported Katharina Kopetschke and her coauthors.

In a study of 123 lupus patients between April 2009 and March 2013, the area under the curve values for CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells (1.000 and 0.9969, respectively) showed better distinction of active lupus nephritis (LN) than did CD19+ B cells (0.7823), CD14+ macrophages (0.9066), and proteinuria (0.9201), Ms. Kopetschke and her colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that noninvasive urine monitoring “might become a useful tool to facilitate clinical decisions concerning kidney biopsies and treatment of LN,” the investigators said in the paper.

Read the full article in Arthritis Research & Therapy (doi:10.1186/s13075-015-0600-y).

Gastric bypass patients on calcium had higher rates of kidney stone growth

SAN DIEGO – Patients taking calcium supplementation after gastric bypass surgery had higher rates of kidney stone growth, compared with those who received no calcium supplementation, results from a single-center retrospective study showed.

In addition, the majority of stones in patients taking calcium supplementation were comprised of calcium oxalate monohydrate, which is less amenable to extracorporeal shockwave therapy. “You need more invasive procedures to break up these kinds of stones,” lead author Christopher Loftus said in an interview at the meeting of the Endocrine Society, where the study was presented during a late-breaking abstract session.

Though it has been demonstrated that bariatric surgery is associated with an increased risk of kidney stone formation (Kidney Int. 2014 [doi:10.1038/ki.2014.352]), Mr. Loftus, a fourth-year medical student at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, and his associates set out to determine whether calcium supplementation increases the risk of nephrolithiasis in 60 stone-forming patients after gastric bypass surgery performed at the Cleveland Clinic. For each patient, two unenhanced CT scans at least 1 month apart and less than 2 years apart were selected at the start of the supplementation date and after the gastric bypass surgery date. The researchers calculated the rate of stone growth by the change in consecutive stone burden (the sum of maximum diameters of stones) divided by the elapsed time between scans.

Of the 60 patients, 31 received postoperative calcium supplementation (an average of 500 mg/day) and 29 did not. Compared with patients who did not take calcium supplementation, those who did were younger (a mean of 53 years vs. 58 years, respectively), more likely to be female (81% vs. 69%), and had a higher body mass index (34.5 kg/m2 vs. 32.7 kg/m2). In addition, a greater proportion of patients taking calcium supplements underwent Roux-en-Y bypass (83% vs. 64%; P = .19), had stones comprised of calcium oxalate (81% vs. 67%; P = .56), and a higher rate of stone growth (more than 10 mm/year vs. less than 5 mm/year; P = .0004). “We weren’t expecting such a pronounced effect,” Mr. Loftus said.

In their abstract, the researchers said that further studies are required to elucidate the exact role of calcium supplementation on stone disease in this patient population.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the American Society of Nephrology. Mr. Loftus reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

SAN DIEGO – Patients taking calcium supplementation after gastric bypass surgery had higher rates of kidney stone growth, compared with those who received no calcium supplementation, results from a single-center retrospective study showed.

In addition, the majority of stones in patients taking calcium supplementation were comprised of calcium oxalate monohydrate, which is less amenable to extracorporeal shockwave therapy. “You need more invasive procedures to break up these kinds of stones,” lead author Christopher Loftus said in an interview at the meeting of the Endocrine Society, where the study was presented during a late-breaking abstract session.

Though it has been demonstrated that bariatric surgery is associated with an increased risk of kidney stone formation (Kidney Int. 2014 [doi:10.1038/ki.2014.352]), Mr. Loftus, a fourth-year medical student at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, and his associates set out to determine whether calcium supplementation increases the risk of nephrolithiasis in 60 stone-forming patients after gastric bypass surgery performed at the Cleveland Clinic. For each patient, two unenhanced CT scans at least 1 month apart and less than 2 years apart were selected at the start of the supplementation date and after the gastric bypass surgery date. The researchers calculated the rate of stone growth by the change in consecutive stone burden (the sum of maximum diameters of stones) divided by the elapsed time between scans.

Of the 60 patients, 31 received postoperative calcium supplementation (an average of 500 mg/day) and 29 did not. Compared with patients who did not take calcium supplementation, those who did were younger (a mean of 53 years vs. 58 years, respectively), more likely to be female (81% vs. 69%), and had a higher body mass index (34.5 kg/m2 vs. 32.7 kg/m2). In addition, a greater proportion of patients taking calcium supplements underwent Roux-en-Y bypass (83% vs. 64%; P = .19), had stones comprised of calcium oxalate (81% vs. 67%; P = .56), and a higher rate of stone growth (more than 10 mm/year vs. less than 5 mm/year; P = .0004). “We weren’t expecting such a pronounced effect,” Mr. Loftus said.

In their abstract, the researchers said that further studies are required to elucidate the exact role of calcium supplementation on stone disease in this patient population.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the American Society of Nephrology. Mr. Loftus reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

SAN DIEGO – Patients taking calcium supplementation after gastric bypass surgery had higher rates of kidney stone growth, compared with those who received no calcium supplementation, results from a single-center retrospective study showed.

In addition, the majority of stones in patients taking calcium supplementation were comprised of calcium oxalate monohydrate, which is less amenable to extracorporeal shockwave therapy. “You need more invasive procedures to break up these kinds of stones,” lead author Christopher Loftus said in an interview at the meeting of the Endocrine Society, where the study was presented during a late-breaking abstract session.

Though it has been demonstrated that bariatric surgery is associated with an increased risk of kidney stone formation (Kidney Int. 2014 [doi:10.1038/ki.2014.352]), Mr. Loftus, a fourth-year medical student at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, and his associates set out to determine whether calcium supplementation increases the risk of nephrolithiasis in 60 stone-forming patients after gastric bypass surgery performed at the Cleveland Clinic. For each patient, two unenhanced CT scans at least 1 month apart and less than 2 years apart were selected at the start of the supplementation date and after the gastric bypass surgery date. The researchers calculated the rate of stone growth by the change in consecutive stone burden (the sum of maximum diameters of stones) divided by the elapsed time between scans.

Of the 60 patients, 31 received postoperative calcium supplementation (an average of 500 mg/day) and 29 did not. Compared with patients who did not take calcium supplementation, those who did were younger (a mean of 53 years vs. 58 years, respectively), more likely to be female (81% vs. 69%), and had a higher body mass index (34.5 kg/m2 vs. 32.7 kg/m2). In addition, a greater proportion of patients taking calcium supplements underwent Roux-en-Y bypass (83% vs. 64%; P = .19), had stones comprised of calcium oxalate (81% vs. 67%; P = .56), and a higher rate of stone growth (more than 10 mm/year vs. less than 5 mm/year; P = .0004). “We weren’t expecting such a pronounced effect,” Mr. Loftus said.

In their abstract, the researchers said that further studies are required to elucidate the exact role of calcium supplementation on stone disease in this patient population.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the American Society of Nephrology. Mr. Loftus reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

AT ENDO 2015

Key clinical point: Calcium supplementation for post-gastric bypass surgery patients may increase the risk of kidney stone growth.

Major finding: Compared with patients who did not take calcium supplementation, those who did had a higher rate of kidney stone growth (more than 10 mm/year vs. less than 5 mm/year; P = .0004).

Data source: An analysis of 60 stone-forming patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery at the Cleveland Clinic.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by a grant from the American Society of Nephrology. Mr. Loftus reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Acute renal failure biggest short-term risk in I-EVAR explantation

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Acute renal failure occurred postoperatively in one-third of patients who underwent endograft explantation after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR), according to the results of a small retrospective study.

The perioperative infected EVAR (I-EVAR) mortality across the study’s 36 patient records (83% male patients, average age 69 years), culled from four surgery centers’ data from 1997 to 2014, was 8%. The overall mortality was 25%, according to Dr. Victor J. Davila of Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, and his colleagues. Dr. Davila presented the findings at the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting.

“These data show that I-EVAR explantation can be performed safely, with acceptable morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Davila, who noted that while acceptable, the rates were still high, particularly for acute renal failure.

“We did not find any difference between the patients who developed renal failure and the type of graft, whether or not there was suprarenal fixation, and an incidence of postoperative acute renal failure,” Dr. Davila said, “However, because acute renal failure is multifactorial, we need to minimize aortic clamp time, as well as minimize the aortic intimal disruption around the renal arteries.”

Three deaths occurred within 30 days post operation, all from anastomotic dehiscence. Additional short-term morbidities included respiratory failure that required tracheostomy in three patients, and bleeding and sepsis in two patients each. Six patients required re-exploration because of infected hematoma, lymphatic leak, small-bowel perforation, open abdomen at initial operation, and anastomotic bleeding. Six more deaths occurred at a mean follow-up of 402 days. One death was attributable to a ruptured aneurysm, another to a progressive inflammatory illness, and four deaths were of indeterminate cause.

Only three of the explantations reviewed by Dr. Davila and his colleagues were considered emergent. The rest (92%) were either elective or urgent. Infected patients tended to present with leukocytosis (63%), pain (58%), and fever (56%), usually about 65 days prior to explantation. The average time between EVAR and presentation with infection was 589 days.

Although most underwent total graft excision, two patients underwent partial excision, including one with a distal iliac limb infection that showed no sign of infection within the main portion of the endograft. Nearly three-quarters of patients had in situ reconstruction.

While nearly a third of patients had positive preoperative blood cultures indicating infection, 81% of intraoperative cultures taken from the explanted graft, aneurysm wall, or sac contents indicated infection.

The gram-positive Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were the most common organisms found in cultures (33% and 17%, respectively), although anaerobics were found in a third of patients, gram negatives in a quarter of patients, and fungal infections in 14%. A majority (58%) of patients received long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy.

Surgeons should reserve the option to keep a graft in situ only in infected EVAR patients who likely would not survive surgical explantation and reconstruction, Dr. Davila said. “Although I believe [medical management] is an alternative, the best course of action is to remove the endograft.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Acute renal failure occurred postoperatively in one-third of patients who underwent endograft explantation after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR), according to the results of a small retrospective study.

The perioperative infected EVAR (I-EVAR) mortality across the study’s 36 patient records (83% male patients, average age 69 years), culled from four surgery centers’ data from 1997 to 2014, was 8%. The overall mortality was 25%, according to Dr. Victor J. Davila of Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, and his colleagues. Dr. Davila presented the findings at the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting.

“These data show that I-EVAR explantation can be performed safely, with acceptable morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Davila, who noted that while acceptable, the rates were still high, particularly for acute renal failure.

“We did not find any difference between the patients who developed renal failure and the type of graft, whether or not there was suprarenal fixation, and an incidence of postoperative acute renal failure,” Dr. Davila said, “However, because acute renal failure is multifactorial, we need to minimize aortic clamp time, as well as minimize the aortic intimal disruption around the renal arteries.”

Three deaths occurred within 30 days post operation, all from anastomotic dehiscence. Additional short-term morbidities included respiratory failure that required tracheostomy in three patients, and bleeding and sepsis in two patients each. Six patients required re-exploration because of infected hematoma, lymphatic leak, small-bowel perforation, open abdomen at initial operation, and anastomotic bleeding. Six more deaths occurred at a mean follow-up of 402 days. One death was attributable to a ruptured aneurysm, another to a progressive inflammatory illness, and four deaths were of indeterminate cause.

Only three of the explantations reviewed by Dr. Davila and his colleagues were considered emergent. The rest (92%) were either elective or urgent. Infected patients tended to present with leukocytosis (63%), pain (58%), and fever (56%), usually about 65 days prior to explantation. The average time between EVAR and presentation with infection was 589 days.

Although most underwent total graft excision, two patients underwent partial excision, including one with a distal iliac limb infection that showed no sign of infection within the main portion of the endograft. Nearly three-quarters of patients had in situ reconstruction.

While nearly a third of patients had positive preoperative blood cultures indicating infection, 81% of intraoperative cultures taken from the explanted graft, aneurysm wall, or sac contents indicated infection.

The gram-positive Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were the most common organisms found in cultures (33% and 17%, respectively), although anaerobics were found in a third of patients, gram negatives in a quarter of patients, and fungal infections in 14%. A majority (58%) of patients received long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy.

Surgeons should reserve the option to keep a graft in situ only in infected EVAR patients who likely would not survive surgical explantation and reconstruction, Dr. Davila said. “Although I believe [medical management] is an alternative, the best course of action is to remove the endograft.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Acute renal failure occurred postoperatively in one-third of patients who underwent endograft explantation after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR), according to the results of a small retrospective study.

The perioperative infected EVAR (I-EVAR) mortality across the study’s 36 patient records (83% male patients, average age 69 years), culled from four surgery centers’ data from 1997 to 2014, was 8%. The overall mortality was 25%, according to Dr. Victor J. Davila of Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, and his colleagues. Dr. Davila presented the findings at the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting.

“These data show that I-EVAR explantation can be performed safely, with acceptable morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Davila, who noted that while acceptable, the rates were still high, particularly for acute renal failure.

“We did not find any difference between the patients who developed renal failure and the type of graft, whether or not there was suprarenal fixation, and an incidence of postoperative acute renal failure,” Dr. Davila said, “However, because acute renal failure is multifactorial, we need to minimize aortic clamp time, as well as minimize the aortic intimal disruption around the renal arteries.”

Three deaths occurred within 30 days post operation, all from anastomotic dehiscence. Additional short-term morbidities included respiratory failure that required tracheostomy in three patients, and bleeding and sepsis in two patients each. Six patients required re-exploration because of infected hematoma, lymphatic leak, small-bowel perforation, open abdomen at initial operation, and anastomotic bleeding. Six more deaths occurred at a mean follow-up of 402 days. One death was attributable to a ruptured aneurysm, another to a progressive inflammatory illness, and four deaths were of indeterminate cause.

Only three of the explantations reviewed by Dr. Davila and his colleagues were considered emergent. The rest (92%) were either elective or urgent. Infected patients tended to present with leukocytosis (63%), pain (58%), and fever (56%), usually about 65 days prior to explantation. The average time between EVAR and presentation with infection was 589 days.

Although most underwent total graft excision, two patients underwent partial excision, including one with a distal iliac limb infection that showed no sign of infection within the main portion of the endograft. Nearly three-quarters of patients had in situ reconstruction.

While nearly a third of patients had positive preoperative blood cultures indicating infection, 81% of intraoperative cultures taken from the explanted graft, aneurysm wall, or sac contents indicated infection.

The gram-positive Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were the most common organisms found in cultures (33% and 17%, respectively), although anaerobics were found in a third of patients, gram negatives in a quarter of patients, and fungal infections in 14%. A majority (58%) of patients received long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy.

Surgeons should reserve the option to keep a graft in situ only in infected EVAR patients who likely would not survive surgical explantation and reconstruction, Dr. Davila said. “Although I believe [medical management] is an alternative, the best course of action is to remove the endograft.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE SAVS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Minimizing cross-clamp time may reduce the rate of acute renal failure 30 days post op in infected EVAR explantation patients.

Major finding: One-third of I-EVAR patients had postoperative acute renal failure; perioperative mortality in I-EVAR was 8%, and overall mortality was 25%.