User login

FDA OKs spinal cord stimulation for diabetic neuropathy pain

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first high-frequency spinal cord stimulation (SCS) therapy for treating painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN).

The approval is specific for the treatment of chronic pain associated with PDN using the Nevro’s Senza System with 10 kHz stimulation. It is intended for patients whose pain is refractory to, or who can’t tolerate, conventional medical treatment. According to the company, there are currently about 2.3 million individuals with refractory PDN in the United States.

The 10 kHz device, called HFX, involves minimally invasive epidural implantation of the stimulator device, which delivers mild electrical impulses to the nerves to interrupt pain signal to the brain. Such spinal cord stimulation “is a straightforward, well-established treatment for chronic pain that’s been used for over 30 years,” according to the company, although this is the first approval of the modality specifically for PDN.

Asked to comment, Rodica Pop-Busui MD, PhD, the Larry D. Soderquist Professor in Diabetes at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said that “the approval of the Nevro 10kHz high-frequency spinal cord stimulation to treat pain associated with diabetic neuropathy has the potential for benefit for many patients with diabetes and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy.”

She noted that, “although there are several other pharmacological agents that currently carry the FDA approval for PDN, this is a condition that is notoriously difficult to treat, particularly when taking into account the actual number needed to treat with a specific agent to achieve a clinically meaningful pain reduction, as well as the spectrum of side effects and drug-drug interactions in a patient population that require many other additional agents to manage diabetes and comorbidities on a daily basis. Thus, this new therapeutic approach besides effective pain reduction has the additional benefit of bypassing drug interactions.” Dr. Pop-Busui was the lead author on the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 position statement on diabetic neuropathy.

She also cautioned, on the other hand, that “it is not very clear yet how easy it will be for all eligible patients to have access to this technology, what will be the actual costs, the insurance coverage, or the acceptance by patients across various sociodemographic backgrounds from the at-large clinical care. However, given the challenges we encounter to treat diabetic neuropathy and particularly the pain associated with it, it is quite encouraging to see that the tools available to help our patients are now broader.”

Both 6-and 12-month results show benefit

The FDA approval was based on 6-month data from a prospective, multicenter, open-label randomized clinical trial published in JAMA Neurology.

Use of the 10-kHz SCS device was compared with conventional treatment alone in 216 patients with PDN refractory to gabapentinoids and at least one other analgesic class and lower limb pain intensity of 5 cm or more on a 10-cm visual analog scale.

The primary endpoint, percentage of participants reporting 50% pain relief or more without worsening of baseline neurologic deficits at 3 months, was met by 5 of 94 (5%) patients in the conventional group, compared with 75 of 95 (79%) with the 10-kHz SCS plus conventional treatment (P < .001).

Infections requiring device explant occurred in two patients in the 10-kHz SCS group (2%).

At 12 months, those in the original SCS group plus 86% of subjects given the option to cross over from the conventional treatment group showed “clear and sustained” benefits of the 10-kHz SCS with regard to lower-limb pain, pain interference with daily living, sleep quality, and activity, Erika Petersen, MD, director of the section of functional and restorative neurosurgery at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock , reported at the 2021 annual scientific sessions of the ADA.

Infection was the most common study-related adverse event, affecting 8 of 154 patients with the SCS implants (5.2%). Three resolved with conservative treatment and five (3.2%) required removal of the device.

The patients will be followed for a total of 24 months.

Commercial launch of HFX in the United States will begin immediately, the company said.

Dr. Pop-Busui has received consultant fees in the last 12 months from Averitas Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Petersen has financial relationships with Nevro, Medtronic, and several other neuromodulator makers.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first high-frequency spinal cord stimulation (SCS) therapy for treating painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN).

The approval is specific for the treatment of chronic pain associated with PDN using the Nevro’s Senza System with 10 kHz stimulation. It is intended for patients whose pain is refractory to, or who can’t tolerate, conventional medical treatment. According to the company, there are currently about 2.3 million individuals with refractory PDN in the United States.

The 10 kHz device, called HFX, involves minimally invasive epidural implantation of the stimulator device, which delivers mild electrical impulses to the nerves to interrupt pain signal to the brain. Such spinal cord stimulation “is a straightforward, well-established treatment for chronic pain that’s been used for over 30 years,” according to the company, although this is the first approval of the modality specifically for PDN.

Asked to comment, Rodica Pop-Busui MD, PhD, the Larry D. Soderquist Professor in Diabetes at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said that “the approval of the Nevro 10kHz high-frequency spinal cord stimulation to treat pain associated with diabetic neuropathy has the potential for benefit for many patients with diabetes and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy.”

She noted that, “although there are several other pharmacological agents that currently carry the FDA approval for PDN, this is a condition that is notoriously difficult to treat, particularly when taking into account the actual number needed to treat with a specific agent to achieve a clinically meaningful pain reduction, as well as the spectrum of side effects and drug-drug interactions in a patient population that require many other additional agents to manage diabetes and comorbidities on a daily basis. Thus, this new therapeutic approach besides effective pain reduction has the additional benefit of bypassing drug interactions.” Dr. Pop-Busui was the lead author on the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 position statement on diabetic neuropathy.

She also cautioned, on the other hand, that “it is not very clear yet how easy it will be for all eligible patients to have access to this technology, what will be the actual costs, the insurance coverage, or the acceptance by patients across various sociodemographic backgrounds from the at-large clinical care. However, given the challenges we encounter to treat diabetic neuropathy and particularly the pain associated with it, it is quite encouraging to see that the tools available to help our patients are now broader.”

Both 6-and 12-month results show benefit

The FDA approval was based on 6-month data from a prospective, multicenter, open-label randomized clinical trial published in JAMA Neurology.

Use of the 10-kHz SCS device was compared with conventional treatment alone in 216 patients with PDN refractory to gabapentinoids and at least one other analgesic class and lower limb pain intensity of 5 cm or more on a 10-cm visual analog scale.

The primary endpoint, percentage of participants reporting 50% pain relief or more without worsening of baseline neurologic deficits at 3 months, was met by 5 of 94 (5%) patients in the conventional group, compared with 75 of 95 (79%) with the 10-kHz SCS plus conventional treatment (P < .001).

Infections requiring device explant occurred in two patients in the 10-kHz SCS group (2%).

At 12 months, those in the original SCS group plus 86% of subjects given the option to cross over from the conventional treatment group showed “clear and sustained” benefits of the 10-kHz SCS with regard to lower-limb pain, pain interference with daily living, sleep quality, and activity, Erika Petersen, MD, director of the section of functional and restorative neurosurgery at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock , reported at the 2021 annual scientific sessions of the ADA.

Infection was the most common study-related adverse event, affecting 8 of 154 patients with the SCS implants (5.2%). Three resolved with conservative treatment and five (3.2%) required removal of the device.

The patients will be followed for a total of 24 months.

Commercial launch of HFX in the United States will begin immediately, the company said.

Dr. Pop-Busui has received consultant fees in the last 12 months from Averitas Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Petersen has financial relationships with Nevro, Medtronic, and several other neuromodulator makers.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first high-frequency spinal cord stimulation (SCS) therapy for treating painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN).

The approval is specific for the treatment of chronic pain associated with PDN using the Nevro’s Senza System with 10 kHz stimulation. It is intended for patients whose pain is refractory to, or who can’t tolerate, conventional medical treatment. According to the company, there are currently about 2.3 million individuals with refractory PDN in the United States.

The 10 kHz device, called HFX, involves minimally invasive epidural implantation of the stimulator device, which delivers mild electrical impulses to the nerves to interrupt pain signal to the brain. Such spinal cord stimulation “is a straightforward, well-established treatment for chronic pain that’s been used for over 30 years,” according to the company, although this is the first approval of the modality specifically for PDN.

Asked to comment, Rodica Pop-Busui MD, PhD, the Larry D. Soderquist Professor in Diabetes at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said that “the approval of the Nevro 10kHz high-frequency spinal cord stimulation to treat pain associated with diabetic neuropathy has the potential for benefit for many patients with diabetes and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy.”

She noted that, “although there are several other pharmacological agents that currently carry the FDA approval for PDN, this is a condition that is notoriously difficult to treat, particularly when taking into account the actual number needed to treat with a specific agent to achieve a clinically meaningful pain reduction, as well as the spectrum of side effects and drug-drug interactions in a patient population that require many other additional agents to manage diabetes and comorbidities on a daily basis. Thus, this new therapeutic approach besides effective pain reduction has the additional benefit of bypassing drug interactions.” Dr. Pop-Busui was the lead author on the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 position statement on diabetic neuropathy.

She also cautioned, on the other hand, that “it is not very clear yet how easy it will be for all eligible patients to have access to this technology, what will be the actual costs, the insurance coverage, or the acceptance by patients across various sociodemographic backgrounds from the at-large clinical care. However, given the challenges we encounter to treat diabetic neuropathy and particularly the pain associated with it, it is quite encouraging to see that the tools available to help our patients are now broader.”

Both 6-and 12-month results show benefit

The FDA approval was based on 6-month data from a prospective, multicenter, open-label randomized clinical trial published in JAMA Neurology.

Use of the 10-kHz SCS device was compared with conventional treatment alone in 216 patients with PDN refractory to gabapentinoids and at least one other analgesic class and lower limb pain intensity of 5 cm or more on a 10-cm visual analog scale.

The primary endpoint, percentage of participants reporting 50% pain relief or more without worsening of baseline neurologic deficits at 3 months, was met by 5 of 94 (5%) patients in the conventional group, compared with 75 of 95 (79%) with the 10-kHz SCS plus conventional treatment (P < .001).

Infections requiring device explant occurred in two patients in the 10-kHz SCS group (2%).

At 12 months, those in the original SCS group plus 86% of subjects given the option to cross over from the conventional treatment group showed “clear and sustained” benefits of the 10-kHz SCS with regard to lower-limb pain, pain interference with daily living, sleep quality, and activity, Erika Petersen, MD, director of the section of functional and restorative neurosurgery at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock , reported at the 2021 annual scientific sessions of the ADA.

Infection was the most common study-related adverse event, affecting 8 of 154 patients with the SCS implants (5.2%). Three resolved with conservative treatment and five (3.2%) required removal of the device.

The patients will be followed for a total of 24 months.

Commercial launch of HFX in the United States will begin immediately, the company said.

Dr. Pop-Busui has received consultant fees in the last 12 months from Averitas Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Petersen has financial relationships with Nevro, Medtronic, and several other neuromodulator makers.

27-year-old woman • postpartum seizures • PTSD • history of depression • Dx?

THE CASE

A 27-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic to establish care for a recent onset of seizures, for which she had previously been admitted, 4 months after delivering her first child. Her pregnancy was complicated by type 1 diabetes and poor glycemic control. Labor was induced at 37 weeks; however, vaginal delivery was impeded by arrest of dilation. An emergency cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia, resulting in a healthy newborn male.

Six weeks after giving birth, the patient was started on sertraline 50 mg/d for postpartum depression. Her history was significant for depression 8 years prior that was controlled with psychotherapy, and treated prior to coming to our clinic. She had not experienced any depressive symptoms during pregnancy.

Three months postpartum, she was hospitalized for recurrent syncopal episodes. They lasted about 2 minutes, with prodromal generalized weakness followed by loss of consciousness. There was no post-event confusion, tongue-biting, or incontinence. Physical exam, electroencephalogram (EEG), echocardiogram, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck demonstrated no acute findings.

These episodes escalated in frequency weeks after they began, involving as many as 40 daily attacks, some of which lasted up to 45 minutes. During these events, the patient was nonresponsive but reported reliving the delivery of her child. Upon initial consultation with Neurology, no cause was found, and she was advised to wear a helmet, stop driving, and refrain from carrying her son. No antiepileptic medications were initiated because there were no EEG findings that supported seizure, and her mood had not improved, despite an increase in sertraline dosage, a switch to citalopram, and the addition of bupropion. She described anxiety, nightmares, and intrusive thoughts during psychotherapy sessions. Her psychiatrist gave her an additional diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) secondary to her delivery. The family medicine clinic assisted the patient and her family throughout her care by functioning as a home base for her.

Eight months following initial symptoms, repeat evaluation with a video-EEG revealed no evidence of EEG changes during seizure-like activity.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of

DISCUSSION

With a prevalence of 5% to 10% and 20% to 40% in outpatient and inpatient epilepsy clinics respectively, PNES events have become of increasing interest to physicians.2 There are few cases of PNES in women during pregnancy reported in the literature.3,4 This is the first case report of PNES with postpartum onset.

Continue to: Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

PNES episodes appear similar to epileptic seizures, but without a definitive neurobiologic source.2,3 However, recent literature suggests the root cause may be found in abnormalities in neurologic networks, such as dysfunction of frontal and parietal lobe connectivity and increased communication from emotional centers of the brain.2,5 There are no typical pathognomonic symptoms of PNES, leading to diagnostic difficulty.2 A definitive diagnosis may be made when a patient experiences seizures without EEG abnormalities.2 Further diagnostic brain imaging is unnecessary.

Trauma may be the underlying cause

A predominance of PNES in both women and young adults, with no definitive associated factors, has been reported in the literature.2 Studies suggest childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, traumatic brain injury, and health-related trauma, such as distressing medical experiences and surgeries, may be risk factors, while depression, misdiagnosis, and mistreatment can heighten seizure activity.2,3

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary team

Effective management of PNES requires collaboration between the primary care physician, neurologist, psychiatrist, and psychotherapist, with an emphasis on evaluation and control of the underlying trigger(s).3 Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive care, and patient education in reducing seizure frequency at the 6-month follow-up.3,6 Additional studies have reported the best prognostic factor in PNES management is patient employment of an internal locus of control—the patient’s belief that they control life events.7,8 Case series suggest electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective alternative mood stabilization and seizure reduction therapy when tolerated.9

Our patient tried several combinations of treatment to manage PNES and comorbid psychiatric conditions, including CBT, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. After about 5 treatment failures, she pursued ECT for treatment-resistant depression and PNES frequency reduction but failed to tolerate therapy. Currently, her PNES has been reduced to 1 to 2 weekly episodes with a 200 mg/d dose of lamotrigine as a mood stabilizer combined with CBT.

THE TAKEAWAY

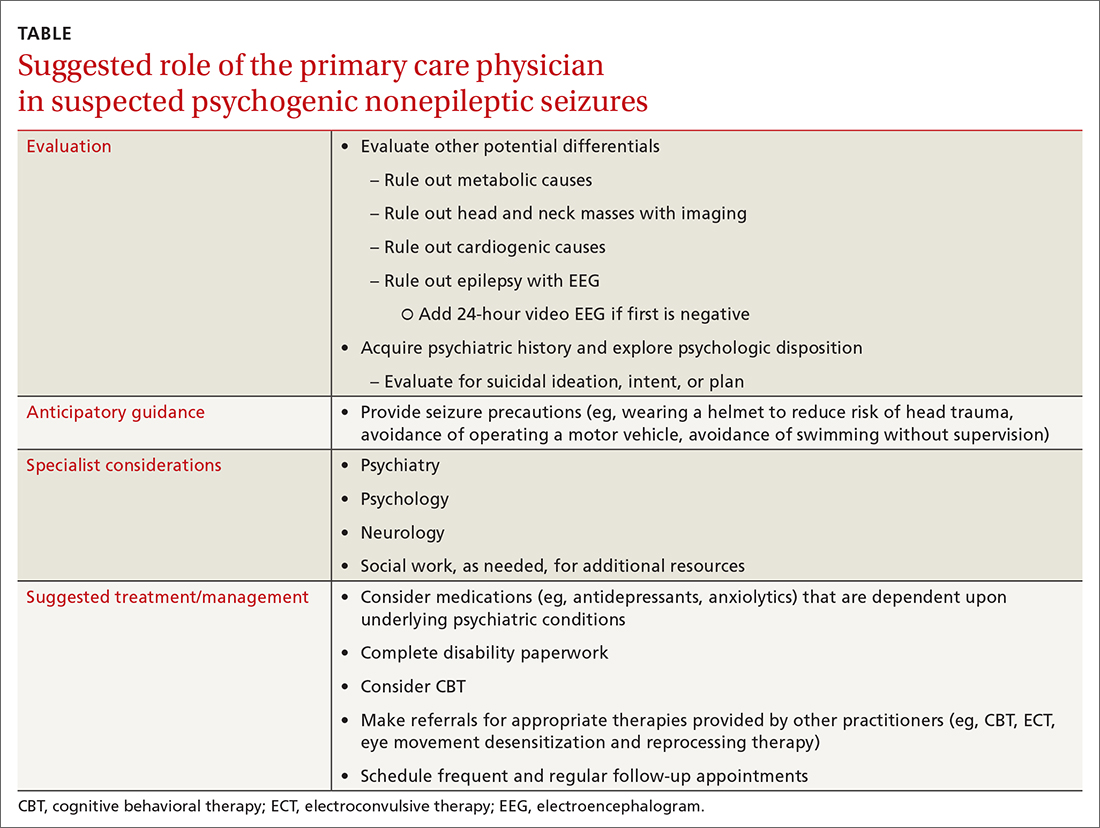

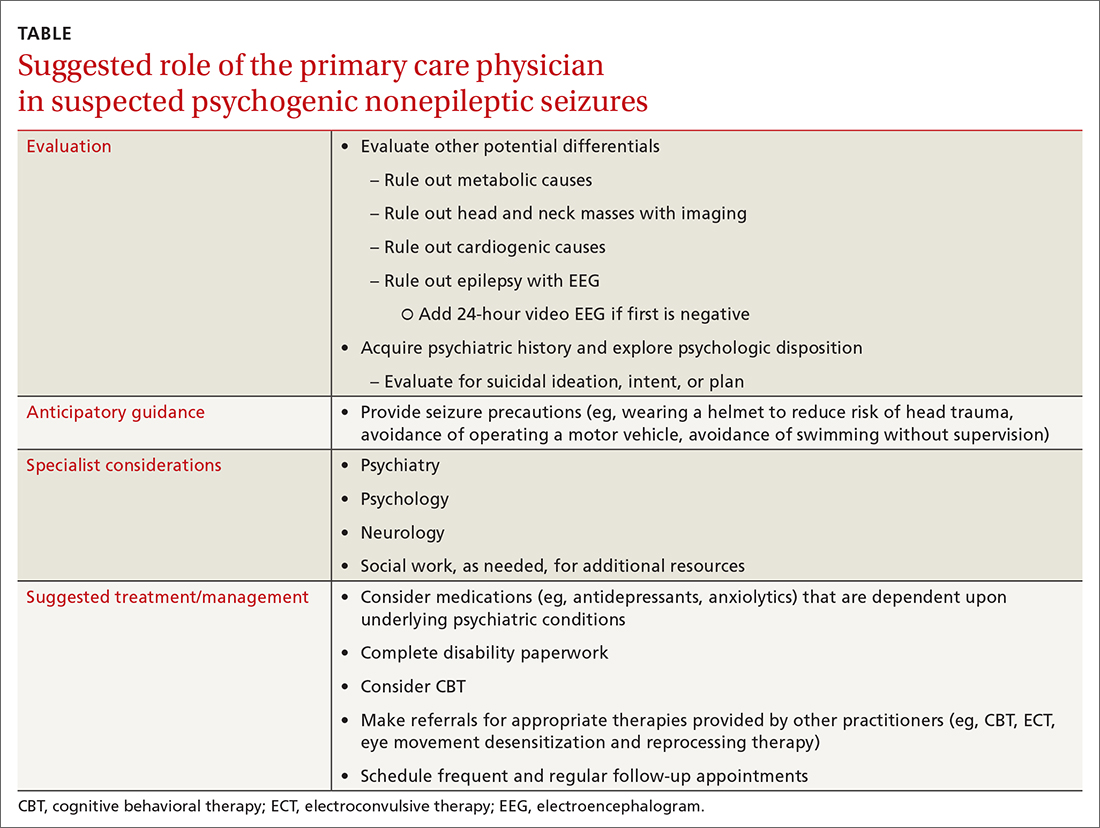

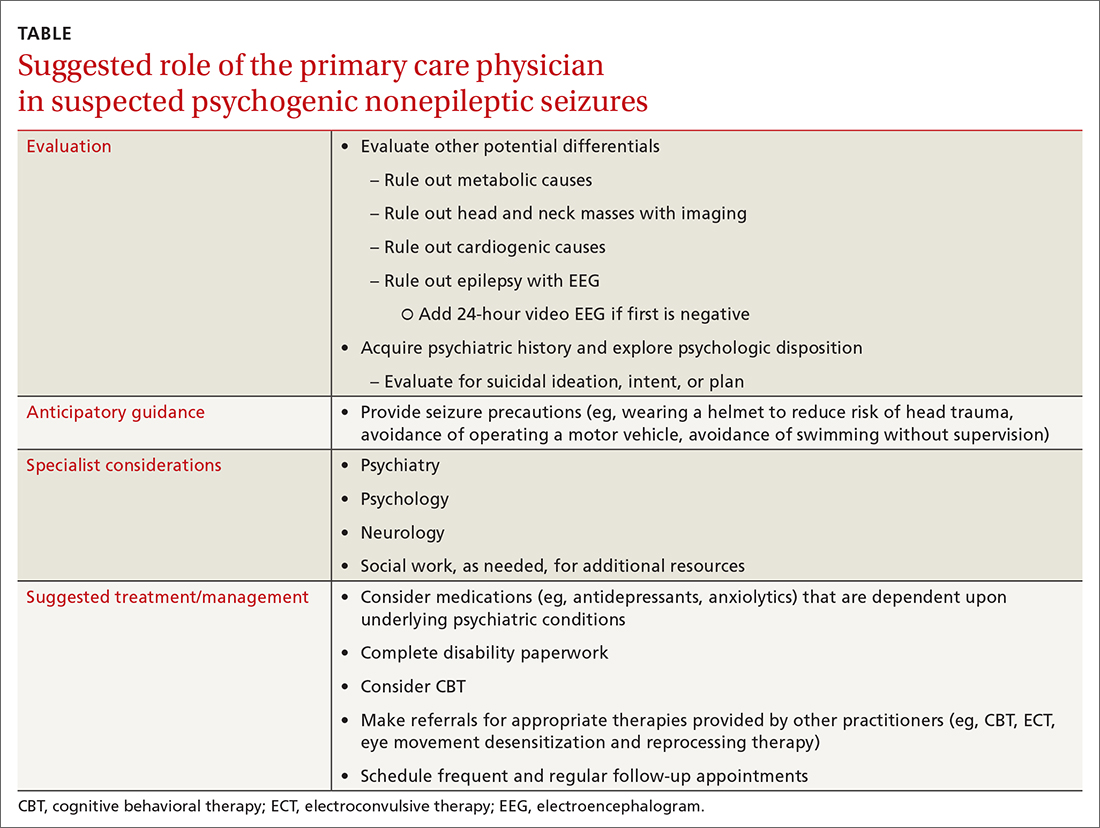

Providers should investigate a patient’s history and psychologic disposition when the patient presents with seizure-like behavior without a neurobiologic source or with a negative video-EEG study. A history of depression, traumatic experience, PTSD, or other psychosocial triggers must be noted early to prevent a delay in treatment when PNES is part of the differential. Due to a delayed diagnosis of PNES in our patient, she went without full treatment for almost 12 months and experienced worsening episodes. The primary care physician plays an integral role in early identification and intervention through anticipatory guidance, initial work-up, and support for patients with suspected PNES (TABLE).

CORRESPONDENCE

Karim Hanna, MD, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL; [email protected]

1. LaFrance WC Jr, Baker GA, Duncan R, et al. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a staged approach: a report from the International League Against Epilepsy Nonepileptic Seizures Task Force. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2005-2018. doi: 10.1111/epi.12356

2. Asadi-Pooya AA, Sperling MR. Epidemiology of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;46:60-65. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.015

3. Devireddy VK, Sharma A. A case of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, unresponsive type, in pregnancy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16:PCC.13l01574. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13l01574

4. DeToledo JC, Lowe MR, Puig A. Nonepileptic seizures in pregnancy. Neurology. 2000;55:120-121. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.120

5. Ding J-R, An D, Liao W, et al. Altered functional and structural connectivity networks in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063850

6. Goldstein LH, Chalder T, Chigwedere C, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a pilot RCT. Neurology. 2010;74:1986-1994. doi: 0.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e39658

7. McLaughlin DP, Pachana NA, McFarland K. The impact of depression, seizure variables and locus of control on health related quality of life in a community dwelling sample of older adults. Seizure. 2010;19:232-236. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.02.008

8. Duncan R, Anderson J, Cullen B, et al. Predictors of 6-month and 3-year outcomes after psychological intervention for psychogenic non epileptic seizures. Seizure. 2016;36:22-26. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.016

9. Blumer D, Rice S, Adamolekun B. Electroconvulsive treatment for nonepileptic seizure disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;15:382-387. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.05.004

THE CASE

A 27-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic to establish care for a recent onset of seizures, for which she had previously been admitted, 4 months after delivering her first child. Her pregnancy was complicated by type 1 diabetes and poor glycemic control. Labor was induced at 37 weeks; however, vaginal delivery was impeded by arrest of dilation. An emergency cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia, resulting in a healthy newborn male.

Six weeks after giving birth, the patient was started on sertraline 50 mg/d for postpartum depression. Her history was significant for depression 8 years prior that was controlled with psychotherapy, and treated prior to coming to our clinic. She had not experienced any depressive symptoms during pregnancy.

Three months postpartum, she was hospitalized for recurrent syncopal episodes. They lasted about 2 minutes, with prodromal generalized weakness followed by loss of consciousness. There was no post-event confusion, tongue-biting, or incontinence. Physical exam, electroencephalogram (EEG), echocardiogram, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck demonstrated no acute findings.

These episodes escalated in frequency weeks after they began, involving as many as 40 daily attacks, some of which lasted up to 45 minutes. During these events, the patient was nonresponsive but reported reliving the delivery of her child. Upon initial consultation with Neurology, no cause was found, and she was advised to wear a helmet, stop driving, and refrain from carrying her son. No antiepileptic medications were initiated because there were no EEG findings that supported seizure, and her mood had not improved, despite an increase in sertraline dosage, a switch to citalopram, and the addition of bupropion. She described anxiety, nightmares, and intrusive thoughts during psychotherapy sessions. Her psychiatrist gave her an additional diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) secondary to her delivery. The family medicine clinic assisted the patient and her family throughout her care by functioning as a home base for her.

Eight months following initial symptoms, repeat evaluation with a video-EEG revealed no evidence of EEG changes during seizure-like activity.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of

DISCUSSION

With a prevalence of 5% to 10% and 20% to 40% in outpatient and inpatient epilepsy clinics respectively, PNES events have become of increasing interest to physicians.2 There are few cases of PNES in women during pregnancy reported in the literature.3,4 This is the first case report of PNES with postpartum onset.

Continue to: Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

PNES episodes appear similar to epileptic seizures, but without a definitive neurobiologic source.2,3 However, recent literature suggests the root cause may be found in abnormalities in neurologic networks, such as dysfunction of frontal and parietal lobe connectivity and increased communication from emotional centers of the brain.2,5 There are no typical pathognomonic symptoms of PNES, leading to diagnostic difficulty.2 A definitive diagnosis may be made when a patient experiences seizures without EEG abnormalities.2 Further diagnostic brain imaging is unnecessary.

Trauma may be the underlying cause

A predominance of PNES in both women and young adults, with no definitive associated factors, has been reported in the literature.2 Studies suggest childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, traumatic brain injury, and health-related trauma, such as distressing medical experiences and surgeries, may be risk factors, while depression, misdiagnosis, and mistreatment can heighten seizure activity.2,3

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary team

Effective management of PNES requires collaboration between the primary care physician, neurologist, psychiatrist, and psychotherapist, with an emphasis on evaluation and control of the underlying trigger(s).3 Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive care, and patient education in reducing seizure frequency at the 6-month follow-up.3,6 Additional studies have reported the best prognostic factor in PNES management is patient employment of an internal locus of control—the patient’s belief that they control life events.7,8 Case series suggest electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective alternative mood stabilization and seizure reduction therapy when tolerated.9

Our patient tried several combinations of treatment to manage PNES and comorbid psychiatric conditions, including CBT, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. After about 5 treatment failures, she pursued ECT for treatment-resistant depression and PNES frequency reduction but failed to tolerate therapy. Currently, her PNES has been reduced to 1 to 2 weekly episodes with a 200 mg/d dose of lamotrigine as a mood stabilizer combined with CBT.

THE TAKEAWAY

Providers should investigate a patient’s history and psychologic disposition when the patient presents with seizure-like behavior without a neurobiologic source or with a negative video-EEG study. A history of depression, traumatic experience, PTSD, or other psychosocial triggers must be noted early to prevent a delay in treatment when PNES is part of the differential. Due to a delayed diagnosis of PNES in our patient, she went without full treatment for almost 12 months and experienced worsening episodes. The primary care physician plays an integral role in early identification and intervention through anticipatory guidance, initial work-up, and support for patients with suspected PNES (TABLE).

CORRESPONDENCE

Karim Hanna, MD, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 27-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic to establish care for a recent onset of seizures, for which she had previously been admitted, 4 months after delivering her first child. Her pregnancy was complicated by type 1 diabetes and poor glycemic control. Labor was induced at 37 weeks; however, vaginal delivery was impeded by arrest of dilation. An emergency cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia, resulting in a healthy newborn male.

Six weeks after giving birth, the patient was started on sertraline 50 mg/d for postpartum depression. Her history was significant for depression 8 years prior that was controlled with psychotherapy, and treated prior to coming to our clinic. She had not experienced any depressive symptoms during pregnancy.

Three months postpartum, she was hospitalized for recurrent syncopal episodes. They lasted about 2 minutes, with prodromal generalized weakness followed by loss of consciousness. There was no post-event confusion, tongue-biting, or incontinence. Physical exam, electroencephalogram (EEG), echocardiogram, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck demonstrated no acute findings.

These episodes escalated in frequency weeks after they began, involving as many as 40 daily attacks, some of which lasted up to 45 minutes. During these events, the patient was nonresponsive but reported reliving the delivery of her child. Upon initial consultation with Neurology, no cause was found, and she was advised to wear a helmet, stop driving, and refrain from carrying her son. No antiepileptic medications were initiated because there were no EEG findings that supported seizure, and her mood had not improved, despite an increase in sertraline dosage, a switch to citalopram, and the addition of bupropion. She described anxiety, nightmares, and intrusive thoughts during psychotherapy sessions. Her psychiatrist gave her an additional diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) secondary to her delivery. The family medicine clinic assisted the patient and her family throughout her care by functioning as a home base for her.

Eight months following initial symptoms, repeat evaluation with a video-EEG revealed no evidence of EEG changes during seizure-like activity.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of

DISCUSSION

With a prevalence of 5% to 10% and 20% to 40% in outpatient and inpatient epilepsy clinics respectively, PNES events have become of increasing interest to physicians.2 There are few cases of PNES in women during pregnancy reported in the literature.3,4 This is the first case report of PNES with postpartum onset.

Continue to: Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

PNES episodes appear similar to epileptic seizures, but without a definitive neurobiologic source.2,3 However, recent literature suggests the root cause may be found in abnormalities in neurologic networks, such as dysfunction of frontal and parietal lobe connectivity and increased communication from emotional centers of the brain.2,5 There are no typical pathognomonic symptoms of PNES, leading to diagnostic difficulty.2 A definitive diagnosis may be made when a patient experiences seizures without EEG abnormalities.2 Further diagnostic brain imaging is unnecessary.

Trauma may be the underlying cause

A predominance of PNES in both women and young adults, with no definitive associated factors, has been reported in the literature.2 Studies suggest childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, traumatic brain injury, and health-related trauma, such as distressing medical experiences and surgeries, may be risk factors, while depression, misdiagnosis, and mistreatment can heighten seizure activity.2,3

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary team

Effective management of PNES requires collaboration between the primary care physician, neurologist, psychiatrist, and psychotherapist, with an emphasis on evaluation and control of the underlying trigger(s).3 Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive care, and patient education in reducing seizure frequency at the 6-month follow-up.3,6 Additional studies have reported the best prognostic factor in PNES management is patient employment of an internal locus of control—the patient’s belief that they control life events.7,8 Case series suggest electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective alternative mood stabilization and seizure reduction therapy when tolerated.9

Our patient tried several combinations of treatment to manage PNES and comorbid psychiatric conditions, including CBT, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. After about 5 treatment failures, she pursued ECT for treatment-resistant depression and PNES frequency reduction but failed to tolerate therapy. Currently, her PNES has been reduced to 1 to 2 weekly episodes with a 200 mg/d dose of lamotrigine as a mood stabilizer combined with CBT.

THE TAKEAWAY

Providers should investigate a patient’s history and psychologic disposition when the patient presents with seizure-like behavior without a neurobiologic source or with a negative video-EEG study. A history of depression, traumatic experience, PTSD, or other psychosocial triggers must be noted early to prevent a delay in treatment when PNES is part of the differential. Due to a delayed diagnosis of PNES in our patient, she went without full treatment for almost 12 months and experienced worsening episodes. The primary care physician plays an integral role in early identification and intervention through anticipatory guidance, initial work-up, and support for patients with suspected PNES (TABLE).

CORRESPONDENCE

Karim Hanna, MD, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL; [email protected]

1. LaFrance WC Jr, Baker GA, Duncan R, et al. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a staged approach: a report from the International League Against Epilepsy Nonepileptic Seizures Task Force. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2005-2018. doi: 10.1111/epi.12356

2. Asadi-Pooya AA, Sperling MR. Epidemiology of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;46:60-65. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.015

3. Devireddy VK, Sharma A. A case of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, unresponsive type, in pregnancy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16:PCC.13l01574. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13l01574

4. DeToledo JC, Lowe MR, Puig A. Nonepileptic seizures in pregnancy. Neurology. 2000;55:120-121. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.120

5. Ding J-R, An D, Liao W, et al. Altered functional and structural connectivity networks in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063850

6. Goldstein LH, Chalder T, Chigwedere C, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a pilot RCT. Neurology. 2010;74:1986-1994. doi: 0.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e39658

7. McLaughlin DP, Pachana NA, McFarland K. The impact of depression, seizure variables and locus of control on health related quality of life in a community dwelling sample of older adults. Seizure. 2010;19:232-236. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.02.008

8. Duncan R, Anderson J, Cullen B, et al. Predictors of 6-month and 3-year outcomes after psychological intervention for psychogenic non epileptic seizures. Seizure. 2016;36:22-26. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.016

9. Blumer D, Rice S, Adamolekun B. Electroconvulsive treatment for nonepileptic seizure disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;15:382-387. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.05.004

1. LaFrance WC Jr, Baker GA, Duncan R, et al. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a staged approach: a report from the International League Against Epilepsy Nonepileptic Seizures Task Force. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2005-2018. doi: 10.1111/epi.12356

2. Asadi-Pooya AA, Sperling MR. Epidemiology of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;46:60-65. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.015

3. Devireddy VK, Sharma A. A case of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, unresponsive type, in pregnancy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16:PCC.13l01574. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13l01574

4. DeToledo JC, Lowe MR, Puig A. Nonepileptic seizures in pregnancy. Neurology. 2000;55:120-121. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.120

5. Ding J-R, An D, Liao W, et al. Altered functional and structural connectivity networks in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063850

6. Goldstein LH, Chalder T, Chigwedere C, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a pilot RCT. Neurology. 2010;74:1986-1994. doi: 0.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e39658

7. McLaughlin DP, Pachana NA, McFarland K. The impact of depression, seizure variables and locus of control on health related quality of life in a community dwelling sample of older adults. Seizure. 2010;19:232-236. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.02.008

8. Duncan R, Anderson J, Cullen B, et al. Predictors of 6-month and 3-year outcomes after psychological intervention for psychogenic non epileptic seizures. Seizure. 2016;36:22-26. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.12.016

9. Blumer D, Rice S, Adamolekun B. Electroconvulsive treatment for nonepileptic seizure disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;15:382-387. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.05.004

Treatment of opioid use disorder with buprenorphine and methadone effective but underutilized

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Legalization of cannabis tied to drop in opioid-related ED visits

State laws permitting recreational marijuana use have not led to an increase in opioid-related emergency department visits, as many had feared.

On the contrary, states that legalize recreational marijuana may see a short-term decrease in opioid-related ED visits in the first 6 months, after which rates may return to prelegalization levels, new research suggests.

Previous research suggests that individuals may reduce the use of opioids when they have an alternative and that cannabis can provide pain relief.

“At the same time, we often hear claims from politicians that we should not legalize cannabis because it may act as a ‘gateway drug’ that leads to use of other drugs,” lead researcher Coleman Drake, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, told this news organization.

“Our findings indicate that cannabis legalization does not effect any increase in opioid-related ED visits, contradicting the gateway drug explanation,” Dr. Drake said.

The study was published online July 12 in Health Economics.

Significant reduction

So far, 19 states have legalized recreational cannabis, meaning that nearly half of the U.S. population lives in a state that allows recreational cannabis use.

The investigators analyzed data on opioid-related ED visits from 29 states between 2011 and 2017. Four states – California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada – legalized recreational marijuana during the study period; the remaining 25 states did not.

The four states with recreational cannabis laws experienced a 7.6% reduction in opioid-related ED visits for 6 months after the law went into effect in comparison with the states that did not legalize recreational marijuana.

“This isn’t trivial – a decline in opioid-related emergency department visits, even if only for 6 months, is a welcome public health development,” Dr. Drake said in a statement.

Not surprisingly, these effects are driven by men and adults aged 25 to 44 years. “These are populations that are more likely to use cannabis, and the reduction in opioid-related ED visits that we find is concentrated among them,” Dr. Drake told this news organization.

However, the downturn in opioid-related ED visits after making marijuana legal was only temporary.

“

Encouragingly, he said, the data show that opioid-related ED visits don’t increase above baseline after recreational marijuana laws are adopted.

“We conclude that cannabis legalization likely is not a panacea for the opioid epidemic, but there are some helpful effects,” Dr. Drake said in an interview.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

State laws permitting recreational marijuana use have not led to an increase in opioid-related emergency department visits, as many had feared.

On the contrary, states that legalize recreational marijuana may see a short-term decrease in opioid-related ED visits in the first 6 months, after which rates may return to prelegalization levels, new research suggests.

Previous research suggests that individuals may reduce the use of opioids when they have an alternative and that cannabis can provide pain relief.

“At the same time, we often hear claims from politicians that we should not legalize cannabis because it may act as a ‘gateway drug’ that leads to use of other drugs,” lead researcher Coleman Drake, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, told this news organization.

“Our findings indicate that cannabis legalization does not effect any increase in opioid-related ED visits, contradicting the gateway drug explanation,” Dr. Drake said.

The study was published online July 12 in Health Economics.

Significant reduction

So far, 19 states have legalized recreational cannabis, meaning that nearly half of the U.S. population lives in a state that allows recreational cannabis use.

The investigators analyzed data on opioid-related ED visits from 29 states between 2011 and 2017. Four states – California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada – legalized recreational marijuana during the study period; the remaining 25 states did not.

The four states with recreational cannabis laws experienced a 7.6% reduction in opioid-related ED visits for 6 months after the law went into effect in comparison with the states that did not legalize recreational marijuana.

“This isn’t trivial – a decline in opioid-related emergency department visits, even if only for 6 months, is a welcome public health development,” Dr. Drake said in a statement.

Not surprisingly, these effects are driven by men and adults aged 25 to 44 years. “These are populations that are more likely to use cannabis, and the reduction in opioid-related ED visits that we find is concentrated among them,” Dr. Drake told this news organization.

However, the downturn in opioid-related ED visits after making marijuana legal was only temporary.

“

Encouragingly, he said, the data show that opioid-related ED visits don’t increase above baseline after recreational marijuana laws are adopted.

“We conclude that cannabis legalization likely is not a panacea for the opioid epidemic, but there are some helpful effects,” Dr. Drake said in an interview.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

State laws permitting recreational marijuana use have not led to an increase in opioid-related emergency department visits, as many had feared.

On the contrary, states that legalize recreational marijuana may see a short-term decrease in opioid-related ED visits in the first 6 months, after which rates may return to prelegalization levels, new research suggests.

Previous research suggests that individuals may reduce the use of opioids when they have an alternative and that cannabis can provide pain relief.

“At the same time, we often hear claims from politicians that we should not legalize cannabis because it may act as a ‘gateway drug’ that leads to use of other drugs,” lead researcher Coleman Drake, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, told this news organization.

“Our findings indicate that cannabis legalization does not effect any increase in opioid-related ED visits, contradicting the gateway drug explanation,” Dr. Drake said.

The study was published online July 12 in Health Economics.

Significant reduction

So far, 19 states have legalized recreational cannabis, meaning that nearly half of the U.S. population lives in a state that allows recreational cannabis use.

The investigators analyzed data on opioid-related ED visits from 29 states between 2011 and 2017. Four states – California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada – legalized recreational marijuana during the study period; the remaining 25 states did not.

The four states with recreational cannabis laws experienced a 7.6% reduction in opioid-related ED visits for 6 months after the law went into effect in comparison with the states that did not legalize recreational marijuana.

“This isn’t trivial – a decline in opioid-related emergency department visits, even if only for 6 months, is a welcome public health development,” Dr. Drake said in a statement.

Not surprisingly, these effects are driven by men and adults aged 25 to 44 years. “These are populations that are more likely to use cannabis, and the reduction in opioid-related ED visits that we find is concentrated among them,” Dr. Drake told this news organization.

However, the downturn in opioid-related ED visits after making marijuana legal was only temporary.

“

Encouragingly, he said, the data show that opioid-related ED visits don’t increase above baseline after recreational marijuana laws are adopted.

“We conclude that cannabis legalization likely is not a panacea for the opioid epidemic, but there are some helpful effects,” Dr. Drake said in an interview.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Zero benefit of aducanumab for Alzheimer’s disease, expert panel rules

adding to growing opposition from medical experts to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this controversial drug.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review asked one of its expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, to consider the available data about aducanumab and requested that members vote on whether there was sufficient evidence of a net benefit of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone. All 15 panelists voted no.

Several panelists, including ICER President Steven D. Pearson, MD, talked about their personal experience with family members who have the disease.

There was universal agreement among the panelists that there is an urgent need for effective medications to treat the disease. However, the panel of clinicians and researchers also agreed that the evidence to date does not show that the drug helps patients with this debilitating disease.

Panelist Sei Lee, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, said he lost his mother to AD 6 years ago. In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Lee has conducted research focused on improving the targeting of preventive AD interventions for older adults to maximize benefits and minimize harms.

Dr. Lee said he frequently felt completely overwhelmed by the challenges of his mother’s disease.

“I absolutely hear everyone who is saying we need an effective therapy for this,” Dr. Lee said.

Dr. Lee added that, as an experienced researcher who has weighed the aducanumab data, he saw no clear proof of a benefit that would outweigh the drug’s documented side effects in the two phase 3 trials of the drug. Those side effects include temporary brain swelling. Dr. Lee suggested that Biogen do more to address concerns about this side effect, saying it should not be ignored.

“There’s clearly substantial uncertainty” about aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “If I had to guess, I think the data is stronger for net harm than it is for that benefit.”

Questions persist about the data Biogen used in support of aducanumab after announcing that the drug had failed in a dual-track phase 3 program.

In March 2019, it was announced that two phase 3 clinical trials, EMERGE and ENGAGE, were scrapped because of disappointing results. The trials were intended to show that aducanumab could slow progression of cognitive and functional impairment, as measured by changes in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

However, in October 2019, there was an about-face – Biogen announced that, in one of the studies, there were positive findings for a subset of patients who received a higher dose of aducanumab.

No treatment benefit was observed in either the high- or low-dose arms at week 78 in the ENGAGE trial. In the EMERGE trial, however, there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline in CDR-SB score in the high-dose arm (difference vs. placebo, –0.39; 95% confidence interval, –0.69 to –0.09) but not in the low-dose arm, ICER noted in a draft report.

Still, there are questions about whether this difference would translate into clinical benefit. “Although statistically significant, the change in CDR-SB score in the high-dose group was less than the 1- to 2-point change that has been suggested as a minimal clinically important difference,” ICER staff wrote.

More push back

Other influential organizations also remain skeptical.

On July 14, the Cleveland Clinic announced it would not use aducanumab at this time, following a staff review of the evidence. Physicians from the clinic could prescribe it to appropriate patients, who would receive their infusions at external facilities, a spokeswoman for the clinic told this news organization. The Cleveland Clinic said it will reevaluate this position as additional data become available.

In addition, as reported by the New York Times, the Mount Sinai Health System in New York also decided not to administer the drug.

The drug received accelerated approval from the FDA. That approval was conditional upon Biogen’s conducting further research by 2030 that demonstrates that the drug has clinical benefit.

On July 14, the executive committee of the American Neurological Association issued a statement asking for a speedier timeline.

The FDA should ensure that Biogen completes the required confirmatory study “as soon as possible, preferably within 3 years, to confirm or not whether clinical efficacy is observed,” the ANA executive committee wrote in the letter.

The ANA executive committee also criticized the FDA’s decision to allow Biogen to begin sales of the drug. In light of the clinical evidence available at this time, aducanumab “should not have been approved” in the first place, the ANA executive committee stated.

drawing from the discussion at the meeting and the panel’s votes. The work of the Boston-based group is used by private insurers to inform medication coverage decisions.

Lawmakers have taken an interest in aducanumab. On July 12, two top Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a letter that they had sent to Biogen as part of their investigation into how the FDA handled the aducanumab approval and Biogen’s pricing for the drug.

In the letter, House Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) and Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) wrote that they had “significant questions about the drug’s clinical benefit, and the steep $56,000 annual price tag.”

At the ICER meeting on July 15, Dr. Lee said patients with AD and their caregivers would benefit more from increased spending on supportive services, such as home health care.

“There’s so many things we could do” with money that Biogen may get for aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “To spend it on a medication that is more likely to do more harm than help seems really ill advised.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

adding to growing opposition from medical experts to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this controversial drug.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review asked one of its expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, to consider the available data about aducanumab and requested that members vote on whether there was sufficient evidence of a net benefit of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone. All 15 panelists voted no.

Several panelists, including ICER President Steven D. Pearson, MD, talked about their personal experience with family members who have the disease.

There was universal agreement among the panelists that there is an urgent need for effective medications to treat the disease. However, the panel of clinicians and researchers also agreed that the evidence to date does not show that the drug helps patients with this debilitating disease.

Panelist Sei Lee, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, said he lost his mother to AD 6 years ago. In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Lee has conducted research focused on improving the targeting of preventive AD interventions for older adults to maximize benefits and minimize harms.

Dr. Lee said he frequently felt completely overwhelmed by the challenges of his mother’s disease.

“I absolutely hear everyone who is saying we need an effective therapy for this,” Dr. Lee said.

Dr. Lee added that, as an experienced researcher who has weighed the aducanumab data, he saw no clear proof of a benefit that would outweigh the drug’s documented side effects in the two phase 3 trials of the drug. Those side effects include temporary brain swelling. Dr. Lee suggested that Biogen do more to address concerns about this side effect, saying it should not be ignored.

“There’s clearly substantial uncertainty” about aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “If I had to guess, I think the data is stronger for net harm than it is for that benefit.”

Questions persist about the data Biogen used in support of aducanumab after announcing that the drug had failed in a dual-track phase 3 program.

In March 2019, it was announced that two phase 3 clinical trials, EMERGE and ENGAGE, were scrapped because of disappointing results. The trials were intended to show that aducanumab could slow progression of cognitive and functional impairment, as measured by changes in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

However, in October 2019, there was an about-face – Biogen announced that, in one of the studies, there were positive findings for a subset of patients who received a higher dose of aducanumab.

No treatment benefit was observed in either the high- or low-dose arms at week 78 in the ENGAGE trial. In the EMERGE trial, however, there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline in CDR-SB score in the high-dose arm (difference vs. placebo, –0.39; 95% confidence interval, –0.69 to –0.09) but not in the low-dose arm, ICER noted in a draft report.

Still, there are questions about whether this difference would translate into clinical benefit. “Although statistically significant, the change in CDR-SB score in the high-dose group was less than the 1- to 2-point change that has been suggested as a minimal clinically important difference,” ICER staff wrote.

More push back

Other influential organizations also remain skeptical.

On July 14, the Cleveland Clinic announced it would not use aducanumab at this time, following a staff review of the evidence. Physicians from the clinic could prescribe it to appropriate patients, who would receive their infusions at external facilities, a spokeswoman for the clinic told this news organization. The Cleveland Clinic said it will reevaluate this position as additional data become available.

In addition, as reported by the New York Times, the Mount Sinai Health System in New York also decided not to administer the drug.

The drug received accelerated approval from the FDA. That approval was conditional upon Biogen’s conducting further research by 2030 that demonstrates that the drug has clinical benefit.

On July 14, the executive committee of the American Neurological Association issued a statement asking for a speedier timeline.

The FDA should ensure that Biogen completes the required confirmatory study “as soon as possible, preferably within 3 years, to confirm or not whether clinical efficacy is observed,” the ANA executive committee wrote in the letter.

The ANA executive committee also criticized the FDA’s decision to allow Biogen to begin sales of the drug. In light of the clinical evidence available at this time, aducanumab “should not have been approved” in the first place, the ANA executive committee stated.

drawing from the discussion at the meeting and the panel’s votes. The work of the Boston-based group is used by private insurers to inform medication coverage decisions.

Lawmakers have taken an interest in aducanumab. On July 12, two top Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a letter that they had sent to Biogen as part of their investigation into how the FDA handled the aducanumab approval and Biogen’s pricing for the drug.

In the letter, House Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) and Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) wrote that they had “significant questions about the drug’s clinical benefit, and the steep $56,000 annual price tag.”

At the ICER meeting on July 15, Dr. Lee said patients with AD and their caregivers would benefit more from increased spending on supportive services, such as home health care.

“There’s so many things we could do” with money that Biogen may get for aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “To spend it on a medication that is more likely to do more harm than help seems really ill advised.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

adding to growing opposition from medical experts to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this controversial drug.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review asked one of its expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, to consider the available data about aducanumab and requested that members vote on whether there was sufficient evidence of a net benefit of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone. All 15 panelists voted no.

Several panelists, including ICER President Steven D. Pearson, MD, talked about their personal experience with family members who have the disease.

There was universal agreement among the panelists that there is an urgent need for effective medications to treat the disease. However, the panel of clinicians and researchers also agreed that the evidence to date does not show that the drug helps patients with this debilitating disease.

Panelist Sei Lee, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, said he lost his mother to AD 6 years ago. In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Lee has conducted research focused on improving the targeting of preventive AD interventions for older adults to maximize benefits and minimize harms.

Dr. Lee said he frequently felt completely overwhelmed by the challenges of his mother’s disease.

“I absolutely hear everyone who is saying we need an effective therapy for this,” Dr. Lee said.

Dr. Lee added that, as an experienced researcher who has weighed the aducanumab data, he saw no clear proof of a benefit that would outweigh the drug’s documented side effects in the two phase 3 trials of the drug. Those side effects include temporary brain swelling. Dr. Lee suggested that Biogen do more to address concerns about this side effect, saying it should not be ignored.

“There’s clearly substantial uncertainty” about aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “If I had to guess, I think the data is stronger for net harm than it is for that benefit.”

Questions persist about the data Biogen used in support of aducanumab after announcing that the drug had failed in a dual-track phase 3 program.

In March 2019, it was announced that two phase 3 clinical trials, EMERGE and ENGAGE, were scrapped because of disappointing results. The trials were intended to show that aducanumab could slow progression of cognitive and functional impairment, as measured by changes in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

However, in October 2019, there was an about-face – Biogen announced that, in one of the studies, there were positive findings for a subset of patients who received a higher dose of aducanumab.

No treatment benefit was observed in either the high- or low-dose arms at week 78 in the ENGAGE trial. In the EMERGE trial, however, there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline in CDR-SB score in the high-dose arm (difference vs. placebo, –0.39; 95% confidence interval, –0.69 to –0.09) but not in the low-dose arm, ICER noted in a draft report.

Still, there are questions about whether this difference would translate into clinical benefit. “Although statistically significant, the change in CDR-SB score in the high-dose group was less than the 1- to 2-point change that has been suggested as a minimal clinically important difference,” ICER staff wrote.

More push back

Other influential organizations also remain skeptical.

On July 14, the Cleveland Clinic announced it would not use aducanumab at this time, following a staff review of the evidence. Physicians from the clinic could prescribe it to appropriate patients, who would receive their infusions at external facilities, a spokeswoman for the clinic told this news organization. The Cleveland Clinic said it will reevaluate this position as additional data become available.

In addition, as reported by the New York Times, the Mount Sinai Health System in New York also decided not to administer the drug.

The drug received accelerated approval from the FDA. That approval was conditional upon Biogen’s conducting further research by 2030 that demonstrates that the drug has clinical benefit.

On July 14, the executive committee of the American Neurological Association issued a statement asking for a speedier timeline.

The FDA should ensure that Biogen completes the required confirmatory study “as soon as possible, preferably within 3 years, to confirm or not whether clinical efficacy is observed,” the ANA executive committee wrote in the letter.

The ANA executive committee also criticized the FDA’s decision to allow Biogen to begin sales of the drug. In light of the clinical evidence available at this time, aducanumab “should not have been approved” in the first place, the ANA executive committee stated.

drawing from the discussion at the meeting and the panel’s votes. The work of the Boston-based group is used by private insurers to inform medication coverage decisions.

Lawmakers have taken an interest in aducanumab. On July 12, two top Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a letter that they had sent to Biogen as part of their investigation into how the FDA handled the aducanumab approval and Biogen’s pricing for the drug.

In the letter, House Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) and Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) wrote that they had “significant questions about the drug’s clinical benefit, and the steep $56,000 annual price tag.”

At the ICER meeting on July 15, Dr. Lee said patients with AD and their caregivers would benefit more from increased spending on supportive services, such as home health care.

“There’s so many things we could do” with money that Biogen may get for aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “To spend it on a medication that is more likely to do more harm than help seems really ill advised.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated consensus statement assesses new migraine treatments

“Because the benefit–risk profiles of newer treatments will continue to evolve as clinical trial and real-world data accrue, the American Headache Society intends to review this statement regularly and update, if appropriate, based on the emergence of evidence with implications for clinical practice,” wrote lead author Jessica Ailani, MD, of the department of neurology at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, and colleagues. The statement was published in Headache.

To assess recent data on the efficacy, safety, and clinical use of newly introduced acute and preventive migraine treatments, the AHS convened a small task force to review relevant literature published from December 2018 through February 2021. The society’s board of directors, along with patients and patient advocates associated with the American Migraine Foundation, also provided pertinent commentary.

New migraine treatment

Five recently approved acute migraine treatments were specifically noted: two small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists – rimegepant and ubrogepant – along with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug celecoxib, the serotonin 5-HT1F agonist lasmiditan, and remote electrical neuromodulation (REN). Highlighted risks include serious cardiovascular thrombotic events in patients on celecoxib, along with driving impairment, sleepiness, and the possibility of overuse in patients on lasmiditan. The authors added, however, that REN “has shown good tolerability and safety in clinical trials” and that frequent use of rimegepant or ubrogepant does not appear to lead to medication-overuse headache.

Regarding acute treatment overall, the statement recommended nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations – such as aspirin plus acetaminophen plus caffeine – for mild to moderate attacks. For moderate or severe attacks, they recommended migraine-specific agents such as triptans, small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), or selective serotonin 5-HT1F receptor agonists (ditans). No matter the prescribed treatment, the statement pushed for patients to “treat at the first sign of pain to improve the probability of achieving freedom from pain and reduce attack-related disability.”

The authors added that 30% of patients on triptans have an “insufficient response” and as such may benefit from a second triptan or – if certain criteria are met – switching to a gepant, a ditan, or a neuromodulatory device. They also recommended a nonoral formulation for patients whose attacks are often accompanied by severe nausea or vomiting.

More broadly, they addressed the tolerability and safety issues associated with certain treatments, including the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects of NSAIDs and the dangers of using triptans in patients with coronary artery disease or other vascular disorders. And while gepants and ditans appeared in clinical trials to be safe choices for patients with stable cardiovascular disease, “benefit-risk should be assessed in each patient as the real-world database for these therapies grows,” they wrote.

Only one recently approved preventive treatment – eptinezumab, an intravenous anti-CGRP ligand monoclonal antibody (MAB) – was highlighted. The authors noted that its benefits can begin within 24 hours, and it can reduce acute medication use and therefore the risk of medication-overuse headache.

Regarding preventive treatments overall, the authors stated that prevention should be offered if patients suffer from 6 or more days of headache per month, or 3-4 days of headache plus some-to-severe disability. Preventive treatments should be considered in patients who range from at least 2 days of headache per month plus severe disability to 4 or 5 days of headache. Prevention should also be considered in patients with uncommon migraine subtypes, including hemiplegic migraine, migraine with brainstem aura, and migraine with prolonged aura.

Initiating treatment

When considering initiation of treatment with one of the four Food and Drug Administration–approved CGRP MABs – eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, or galcanezumab – the authors recommend their use if migraine patients show an inability to tolerate or respond to a trial of two or more older oral medications or other established effective therapies. Though they emphasized that oral preventive medications should be started at a low dose and titrated slowly until the target response is reached or tolerability issues emerge, no such need was specified for the parenteral treatments. They also endorsed the approach of patients staying on oral preventive drugs for a minimum of 8 weeks to determine effectiveness or a lack thereof; at that point, switching to another treatment is recommended.

The dual use of therapies such as neuromodulation, biobehavioral therapies, and gepants were also examined, including gepants’ potential as a “continuum between the acute and preventive treatment of migraine” and the limited use of neuromodulatory devices in clinical practice despite clear benefits in patients who prefer to avoid medication or those suffering from frequent attacks and subsequent medication overuse. In addition, it was stated that biobehavioral therapies have “grade A evidence” supporting their use in patients who either prefer nonpharmacologic treatments or have an adverse or poor reaction to the drugs.

From the patient perspective, one of the six reviewers shared concerns about migraine patients being required to try two established preventive medications before starting a recently introduced option, noting that the older drugs have lower efficacy and tolerability. Two reviewers would have liked to see the statement focus more on nonpharmacologic and device-related therapies, and one reviewer noted the possible value in guidance regarding “exploratory approaches” such as cannabis.

The authors acknowledged numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving speaking and consulting fees, grants, personal fees, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical and publishing companies.

Not everyone agrees

Commenting on the AHS consensus statement, James A Charles, MD, and Ira Turner, MD, had this to say: “This Consensus Statement incorporates the best available evidence including the newer CGRP therapies as well as the older treatments. The AHS posture is that the CGRP abortive and preventive treatments have a lesser amount of data and experience than the older treatments which have a wealth of literature and data because they have been around longer. As a result, there are 2 statements in these guidelines that the insurance companies quote in their manual of policies:

1. Inadequate response to two or more oral triptans before using a gepant as abortive treatment

2. Inadequate response to an 8-week trial at a dose established to be potentially effective of two or more of the following before using CGRP MAB for preventive treatment: topiramate, divalproex sodium/valproate sodium; beta-blocker: metoprolol, propranolol, timolol, atenolol, nadolol; tricyclic antidepressant: amitriptyline, nortriptyline; serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor: venlafaxine, duloxetine; other Level A or B treatments.”

Dr. Charles, who is affiliated with Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck N.J., and Dr. Turner, who is affiliated with the Center for Headache Care and Research at Island Neurological Associates in Plainview, N.Y., further said that “giving the CGRP MABs and gepants second-class status because they have not been around as long as the old boys is an insult to the research, development, and successful execution of gepant and CGRP MAB therapies in the last several years. The authors omitted the Hepp study and the long list of adverse effects of triptans leading to high discontinuance rates, and how trying a second triptan will probably not work.” Importantly, they said, “the authors have given the insurance carriers a weapon to deny direct access to gepants and CGRP MABs making direct access to these agents difficult for patients and physicians and their staffs.”

Dr. Charles and Dr. Turner point out that the AHS guidelines use the term “cost effective” – that it is better to use the cheaper, older drugs first. “Ineffective treatment of a patient for 8 weeks before using CGRP blocking therapies and using 2 triptans before a gepant is cost ineffective,” they said. “Inadequate delayed treatment results in loss of work productivity and loss of school and family participation and excessive use of ER visits. These guidelines forget that we ameliorate current disability and prevent chronification by treating with the most effective abortive and preventive therapies which may not commence with the cheaper old drugs.”

They explain: “Of course, we would use a beta-blocker for comorbid hypertension and/or anxiety, and venlafaxine for comorbid depression. And if a patient is pain free in 2 hrs with no adverse effects from a triptan used less than 10 times a month, it would not be appropriate to switch to a gepant. However, a treatment naive migraineur with accelerating migraine should have the option of going directly to a gepant and CGRP blocking MAB.” Dr. Charles and Dr. Turner concur that the phrase in the AHS consensus statement regarding the staging of therapy – two triptans before a gepant and two oral preventatives for 8 weeks before a CGRP MAB – “should be removed so that the CGRP drugs get the equal credit they deserve, as can be attested to by the migraine voices of lives saved by the sound research that led to their development and approval by the FDA.”

Ultimately, Dr. Charles and Dr. Turner said, “the final decision on treatment should be made by the physician and patient, not the insurance company or consensus statements.”