User login

Managing pain expectations is key to enhanced recovery

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.

In addition, it is important to continue to collect data and study methods to treat pain and reduce opioid use perioperatively, Dr. Miller said. Some ongoing concerns include data surrounding the use of gabapentin and possible association with respiratory depression, he noted. Several meta-analyses have suggested that “gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin) when given as a single dose preoperatively are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain and opioid consumption at 24 hours,” said Dr. Miller. “When gabapentinoids are included in multimodal analgesic regimens, intraoperative opioids must be reduced, and increased vigilance for respiratory depression may be warranted, especially in elderly patients,” he said.

Overall, opioid-free anesthesia is both feasible and appropriate in certain patient populations, Dr. Miller concluded. “Implement your pathway and measure your outcomes with timely feedback so you can revise your protocol based on data,” he emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Miller disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, and serving as a board member for the Perioperative Quality Initiative and as a founding member of the Morpheus Consortium.

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.

In addition, it is important to continue to collect data and study methods to treat pain and reduce opioid use perioperatively, Dr. Miller said. Some ongoing concerns include data surrounding the use of gabapentin and possible association with respiratory depression, he noted. Several meta-analyses have suggested that “gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin) when given as a single dose preoperatively are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain and opioid consumption at 24 hours,” said Dr. Miller. “When gabapentinoids are included in multimodal analgesic regimens, intraoperative opioids must be reduced, and increased vigilance for respiratory depression may be warranted, especially in elderly patients,” he said.

Overall, opioid-free anesthesia is both feasible and appropriate in certain patient populations, Dr. Miller concluded. “Implement your pathway and measure your outcomes with timely feedback so you can revise your protocol based on data,” he emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Miller disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, and serving as a board member for the Perioperative Quality Initiative and as a founding member of the Morpheus Consortium.

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.

In addition, it is important to continue to collect data and study methods to treat pain and reduce opioid use perioperatively, Dr. Miller said. Some ongoing concerns include data surrounding the use of gabapentin and possible association with respiratory depression, he noted. Several meta-analyses have suggested that “gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin) when given as a single dose preoperatively are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain and opioid consumption at 24 hours,” said Dr. Miller. “When gabapentinoids are included in multimodal analgesic regimens, intraoperative opioids must be reduced, and increased vigilance for respiratory depression may be warranted, especially in elderly patients,” he said.

Overall, opioid-free anesthesia is both feasible and appropriate in certain patient populations, Dr. Miller concluded. “Implement your pathway and measure your outcomes with timely feedback so you can revise your protocol based on data,” he emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Miller disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, and serving as a board member for the Perioperative Quality Initiative and as a founding member of the Morpheus Consortium.

FROM MISS

Pursue multimodal pain management in patients taking opioids

For surgical patients on chronic opioid therapy, , according to Stephanie B. Jones, MD, professor and chair of anesthesiology at Albany Medical College, New York.

“[With] any patient coming in for any sort of surgery, you should be considering multimodal pain management. That applies to the opioid use disorder patient as well,” Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The challenge of opioid-tolerant patients or opioid abuse patients is twofold – tolerance and hyperalgesia,” Dr. Jones said. Patient tolerance changes how patients perceive pain and respond to medication. Clinicians need to consider the “opioid debt,” defined as the daily amount of opioid medication required by opioid-dependent patients to maintain their usual prehospitalization opioid levels, she explained. Also consider hyperalgesia, a change in pain perception “resulting in an increase in pain sensitivity to painful stimuli, thereby decreasing the analgesic effects of opioids,” Dr. Jones added.

A multimodal approach to pain management in patients on chronic opioids can include some opioids as appropriate, Dr. Jones said. Modulation of pain may draw on epidurals and nerve blocks, as well as managing CNS perception of pain through opioids or acetaminophen, and also using systemic options such as alpha-2 agonists and tramadol, she said.

Studies have shown that opioid abuse or dependence were associated with increased readmission rates, length of stay, and health care costs in surgery patients, said Dr. Jones. However, switching opioids and managing equivalents is complex, and “equianalgesic conversions serve only as a general guide to estimate opioid dose equivalents,” according to UpToDate’s, “Management of acute pain in the patient chronically using opioids,” she said.

Dr. Jones also addressed the issue of using hospitalization as an opportunity to help patients with untreated opioid use disorder. Medication-assisted options include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“One problem with methadone is that there are a lot of medications interactions,” she said. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being long-lasting, and is formulated with naloxone which deters injection. “Because it is a partial agonist, there is a lower risk of overdose and sedation,” and it has fewer medication interactions. However, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe it and there is some risk of medication diversion, she said.

Naltrexone is newer to the role of treating opioid use disorder, Dr. Jones said. “It can cause acute withdrawal because it is a full opioid antagonist,” she noted. However, naltrexone itself causes no withdrawal if stopped, and no respiratory depression or sedation, said Dr. Jones.

“Utilize addiction services in your hospital if you suspect a patient may be at risk for opioid use disorder,” and engage these services early, she emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones had no financial conflicts to disclose.

For surgical patients on chronic opioid therapy, , according to Stephanie B. Jones, MD, professor and chair of anesthesiology at Albany Medical College, New York.

“[With] any patient coming in for any sort of surgery, you should be considering multimodal pain management. That applies to the opioid use disorder patient as well,” Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The challenge of opioid-tolerant patients or opioid abuse patients is twofold – tolerance and hyperalgesia,” Dr. Jones said. Patient tolerance changes how patients perceive pain and respond to medication. Clinicians need to consider the “opioid debt,” defined as the daily amount of opioid medication required by opioid-dependent patients to maintain their usual prehospitalization opioid levels, she explained. Also consider hyperalgesia, a change in pain perception “resulting in an increase in pain sensitivity to painful stimuli, thereby decreasing the analgesic effects of opioids,” Dr. Jones added.

A multimodal approach to pain management in patients on chronic opioids can include some opioids as appropriate, Dr. Jones said. Modulation of pain may draw on epidurals and nerve blocks, as well as managing CNS perception of pain through opioids or acetaminophen, and also using systemic options such as alpha-2 agonists and tramadol, she said.

Studies have shown that opioid abuse or dependence were associated with increased readmission rates, length of stay, and health care costs in surgery patients, said Dr. Jones. However, switching opioids and managing equivalents is complex, and “equianalgesic conversions serve only as a general guide to estimate opioid dose equivalents,” according to UpToDate’s, “Management of acute pain in the patient chronically using opioids,” she said.

Dr. Jones also addressed the issue of using hospitalization as an opportunity to help patients with untreated opioid use disorder. Medication-assisted options include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“One problem with methadone is that there are a lot of medications interactions,” she said. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being long-lasting, and is formulated with naloxone which deters injection. “Because it is a partial agonist, there is a lower risk of overdose and sedation,” and it has fewer medication interactions. However, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe it and there is some risk of medication diversion, she said.

Naltrexone is newer to the role of treating opioid use disorder, Dr. Jones said. “It can cause acute withdrawal because it is a full opioid antagonist,” she noted. However, naltrexone itself causes no withdrawal if stopped, and no respiratory depression or sedation, said Dr. Jones.

“Utilize addiction services in your hospital if you suspect a patient may be at risk for opioid use disorder,” and engage these services early, she emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones had no financial conflicts to disclose.

For surgical patients on chronic opioid therapy, , according to Stephanie B. Jones, MD, professor and chair of anesthesiology at Albany Medical College, New York.

“[With] any patient coming in for any sort of surgery, you should be considering multimodal pain management. That applies to the opioid use disorder patient as well,” Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The challenge of opioid-tolerant patients or opioid abuse patients is twofold – tolerance and hyperalgesia,” Dr. Jones said. Patient tolerance changes how patients perceive pain and respond to medication. Clinicians need to consider the “opioid debt,” defined as the daily amount of opioid medication required by opioid-dependent patients to maintain their usual prehospitalization opioid levels, she explained. Also consider hyperalgesia, a change in pain perception “resulting in an increase in pain sensitivity to painful stimuli, thereby decreasing the analgesic effects of opioids,” Dr. Jones added.

A multimodal approach to pain management in patients on chronic opioids can include some opioids as appropriate, Dr. Jones said. Modulation of pain may draw on epidurals and nerve blocks, as well as managing CNS perception of pain through opioids or acetaminophen, and also using systemic options such as alpha-2 agonists and tramadol, she said.

Studies have shown that opioid abuse or dependence were associated with increased readmission rates, length of stay, and health care costs in surgery patients, said Dr. Jones. However, switching opioids and managing equivalents is complex, and “equianalgesic conversions serve only as a general guide to estimate opioid dose equivalents,” according to UpToDate’s, “Management of acute pain in the patient chronically using opioids,” she said.

Dr. Jones also addressed the issue of using hospitalization as an opportunity to help patients with untreated opioid use disorder. Medication-assisted options include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“One problem with methadone is that there are a lot of medications interactions,” she said. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being long-lasting, and is formulated with naloxone which deters injection. “Because it is a partial agonist, there is a lower risk of overdose and sedation,” and it has fewer medication interactions. However, some doctors are reluctant to prescribe it and there is some risk of medication diversion, she said.

Naltrexone is newer to the role of treating opioid use disorder, Dr. Jones said. “It can cause acute withdrawal because it is a full opioid antagonist,” she noted. However, naltrexone itself causes no withdrawal if stopped, and no respiratory depression or sedation, said Dr. Jones.

“Utilize addiction services in your hospital if you suspect a patient may be at risk for opioid use disorder,” and engage these services early, she emphasized.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM MISS

Visualization tool aids migraine management

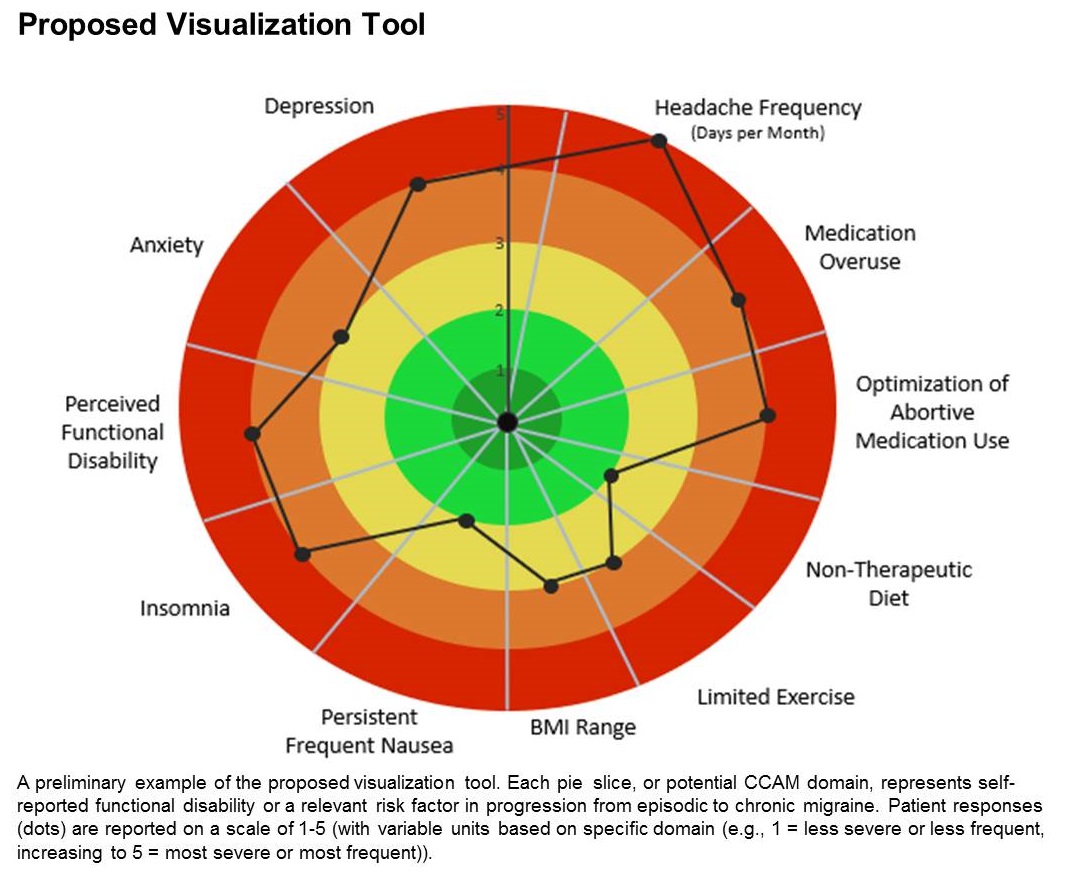

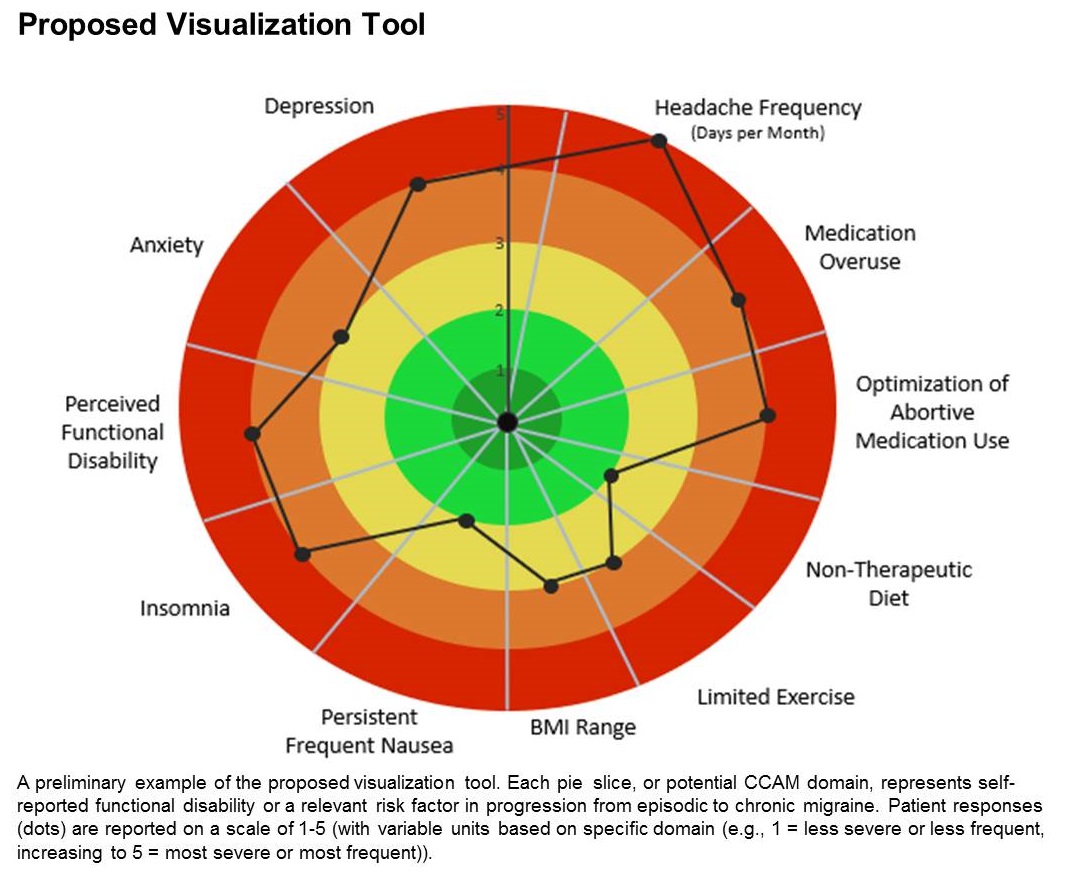

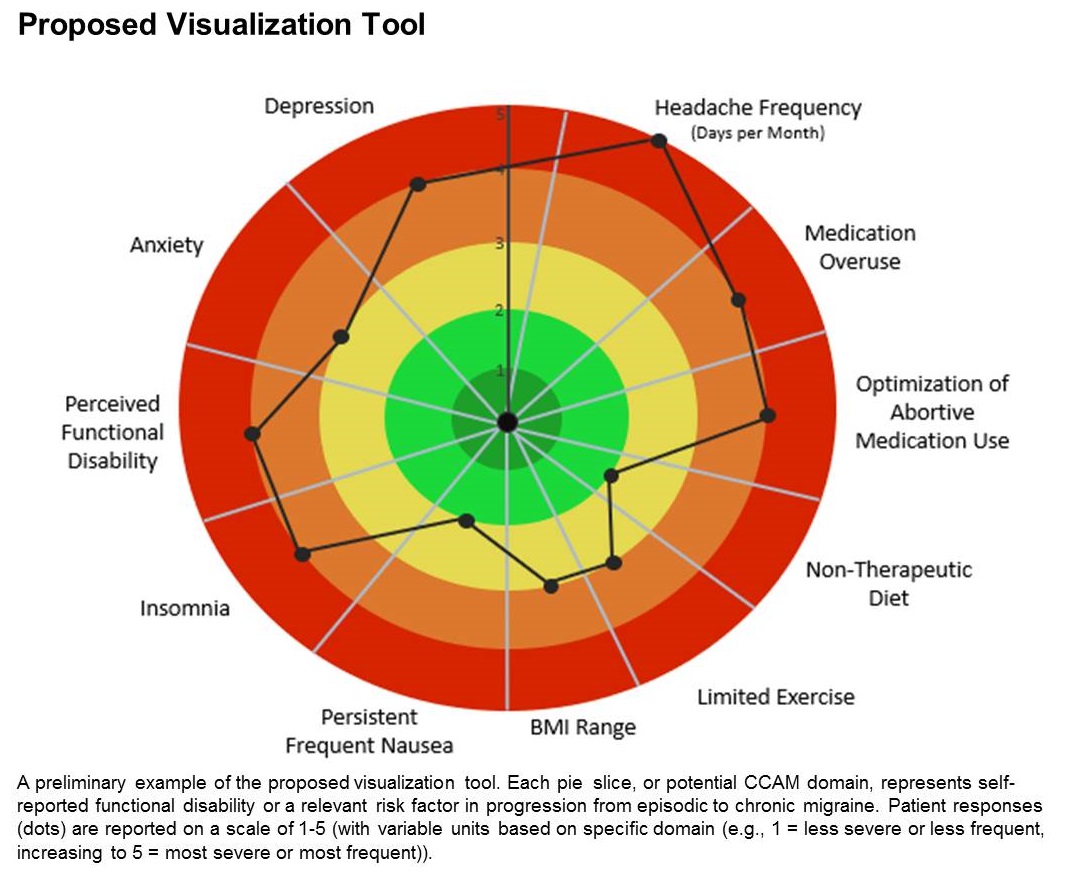

The tool is still in the prototype stage, but it could eventually synthesize patient responses to an integrated questionnaire and produce a chart illustrating where the patient stands with respect to a range of modifiable risk factors, including depression, medication overuse, insomnia, and body mass index, among others.

A few such tools exist for other conditions, such as stroke and risk of developing chronic diseases. Existing migraine visualization models focus only on individual risk factors, but they are capable of much more. “Visualization tools can effectively communicate a huge amount of clinical information,” said lead author Ami Cuneo, MD, who is a headache fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle, in an interview. Dr. Cuneo presented a poster describing the concept at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

A picture is worth a thousand words

Dr. Cuneo’s background is well suited to the effort: Before entering medicine, she was a documentary producer. “I have a lot of interest in the patient story and history,” she added. She also believes that the tool could improve patient-provider relationships. In rushed sessions, patients may not feel heard. Patients gain a therapeutic benefit from the belief that their provider is listening to them and listening to their story. Visualization tools could promote that if the provider can quickly identify key elements of the patient’s condition. “A lot of headache patients can have a complex picture,” said Dr. Cuneo.

Physicians must see patients in short appointment periods, making it difficult to communicate all of the risk factors and behavioral characteristics that can contribute to risk of progression. “If you have a patient and you’re able to look at a visualization tool quickly and say: ‘Okay, my patient really is having insomnia and sleep issues,’ you can focus the session talking about sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, and all the things we can help patients with,” said Dr. Cuneo.

The prototype visualization tool uses a color-coded wheel divided into pie slices, each representing a clinical characteristic or modifiable risk factor. In the proposed tool presented in the poster, these included depression, anxiety, functional disability, insomnia, nausea, headache frequency, medication overuse, optimization of abortive medication use, nontherapeutic diet, limited exercise, and body mass index range. The circle also contains colored concentric circles, ranging from red to green, and a small filled circle represents the patient’s status in each category as ranked using the integrated questionnaire. A line connects the circles in each pie, revealing the patient’s overall status.

The visual cue allows both the physician and patient to quickly assess these factors and see them in relationship to one another. Verbally communicating each factor is time consuming and harder for the patient to take in, according to Dr. Cuneo. “The provider can just look at it and see the areas to focus questions on to try to improve care. So it’s a way I’m hopeful that we can help target visits and improve patient-provider communication without extending visit time.”

A key challenge for the project will be choosing and consolidating scales so that the patient isn’t burdened with too many questions in advance of the appointment. The team will draw from existing scales and then create their own and validate it. “The questions will have to be vetted with patients through focus groups, and then the software platform [will have to be developed] so that patients can complete the survey online. Then we have to test it to see if providers and patients feel this is something that’s helpful in the clinical practice,” said Dr. Cuneo.

Will it change behavior?

If successful, the tool would be a welcome addition, according to Andrew Charles, MD, who was asked to comment on the work. “Epidemiological studies have identified these risk factors, but we haven’t had a way of operationalizing a strategy to reduce them systematically, so having some sort of tool that visualizes not just one but multiple risk factors is something I think could be helpful to address those factors more aggressively. The real question would be, if you put it in the hands of practitioners and patients, will they really be able to easily implement it and will it change behavior,” said Dr. Charles, who is a professor of neurology and director of the Goldberg Migraine Program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study received no funding. Dr. Cuneo and Dr. Charles have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE; Cuneo A et al. AHS 2020, Abstract 273715.

The tool is still in the prototype stage, but it could eventually synthesize patient responses to an integrated questionnaire and produce a chart illustrating where the patient stands with respect to a range of modifiable risk factors, including depression, medication overuse, insomnia, and body mass index, among others.

A few such tools exist for other conditions, such as stroke and risk of developing chronic diseases. Existing migraine visualization models focus only on individual risk factors, but they are capable of much more. “Visualization tools can effectively communicate a huge amount of clinical information,” said lead author Ami Cuneo, MD, who is a headache fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle, in an interview. Dr. Cuneo presented a poster describing the concept at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

A picture is worth a thousand words

Dr. Cuneo’s background is well suited to the effort: Before entering medicine, she was a documentary producer. “I have a lot of interest in the patient story and history,” she added. She also believes that the tool could improve patient-provider relationships. In rushed sessions, patients may not feel heard. Patients gain a therapeutic benefit from the belief that their provider is listening to them and listening to their story. Visualization tools could promote that if the provider can quickly identify key elements of the patient’s condition. “A lot of headache patients can have a complex picture,” said Dr. Cuneo.

Physicians must see patients in short appointment periods, making it difficult to communicate all of the risk factors and behavioral characteristics that can contribute to risk of progression. “If you have a patient and you’re able to look at a visualization tool quickly and say: ‘Okay, my patient really is having insomnia and sleep issues,’ you can focus the session talking about sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, and all the things we can help patients with,” said Dr. Cuneo.

The prototype visualization tool uses a color-coded wheel divided into pie slices, each representing a clinical characteristic or modifiable risk factor. In the proposed tool presented in the poster, these included depression, anxiety, functional disability, insomnia, nausea, headache frequency, medication overuse, optimization of abortive medication use, nontherapeutic diet, limited exercise, and body mass index range. The circle also contains colored concentric circles, ranging from red to green, and a small filled circle represents the patient’s status in each category as ranked using the integrated questionnaire. A line connects the circles in each pie, revealing the patient’s overall status.

The visual cue allows both the physician and patient to quickly assess these factors and see them in relationship to one another. Verbally communicating each factor is time consuming and harder for the patient to take in, according to Dr. Cuneo. “The provider can just look at it and see the areas to focus questions on to try to improve care. So it’s a way I’m hopeful that we can help target visits and improve patient-provider communication without extending visit time.”

A key challenge for the project will be choosing and consolidating scales so that the patient isn’t burdened with too many questions in advance of the appointment. The team will draw from existing scales and then create their own and validate it. “The questions will have to be vetted with patients through focus groups, and then the software platform [will have to be developed] so that patients can complete the survey online. Then we have to test it to see if providers and patients feel this is something that’s helpful in the clinical practice,” said Dr. Cuneo.

Will it change behavior?

If successful, the tool would be a welcome addition, according to Andrew Charles, MD, who was asked to comment on the work. “Epidemiological studies have identified these risk factors, but we haven’t had a way of operationalizing a strategy to reduce them systematically, so having some sort of tool that visualizes not just one but multiple risk factors is something I think could be helpful to address those factors more aggressively. The real question would be, if you put it in the hands of practitioners and patients, will they really be able to easily implement it and will it change behavior,” said Dr. Charles, who is a professor of neurology and director of the Goldberg Migraine Program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study received no funding. Dr. Cuneo and Dr. Charles have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE; Cuneo A et al. AHS 2020, Abstract 273715.

The tool is still in the prototype stage, but it could eventually synthesize patient responses to an integrated questionnaire and produce a chart illustrating where the patient stands with respect to a range of modifiable risk factors, including depression, medication overuse, insomnia, and body mass index, among others.

A few such tools exist for other conditions, such as stroke and risk of developing chronic diseases. Existing migraine visualization models focus only on individual risk factors, but they are capable of much more. “Visualization tools can effectively communicate a huge amount of clinical information,” said lead author Ami Cuneo, MD, who is a headache fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle, in an interview. Dr. Cuneo presented a poster describing the concept at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

A picture is worth a thousand words

Dr. Cuneo’s background is well suited to the effort: Before entering medicine, she was a documentary producer. “I have a lot of interest in the patient story and history,” she added. She also believes that the tool could improve patient-provider relationships. In rushed sessions, patients may not feel heard. Patients gain a therapeutic benefit from the belief that their provider is listening to them and listening to their story. Visualization tools could promote that if the provider can quickly identify key elements of the patient’s condition. “A lot of headache patients can have a complex picture,” said Dr. Cuneo.

Physicians must see patients in short appointment periods, making it difficult to communicate all of the risk factors and behavioral characteristics that can contribute to risk of progression. “If you have a patient and you’re able to look at a visualization tool quickly and say: ‘Okay, my patient really is having insomnia and sleep issues,’ you can focus the session talking about sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, and all the things we can help patients with,” said Dr. Cuneo.

The prototype visualization tool uses a color-coded wheel divided into pie slices, each representing a clinical characteristic or modifiable risk factor. In the proposed tool presented in the poster, these included depression, anxiety, functional disability, insomnia, nausea, headache frequency, medication overuse, optimization of abortive medication use, nontherapeutic diet, limited exercise, and body mass index range. The circle also contains colored concentric circles, ranging from red to green, and a small filled circle represents the patient’s status in each category as ranked using the integrated questionnaire. A line connects the circles in each pie, revealing the patient’s overall status.

The visual cue allows both the physician and patient to quickly assess these factors and see them in relationship to one another. Verbally communicating each factor is time consuming and harder for the patient to take in, according to Dr. Cuneo. “The provider can just look at it and see the areas to focus questions on to try to improve care. So it’s a way I’m hopeful that we can help target visits and improve patient-provider communication without extending visit time.”

A key challenge for the project will be choosing and consolidating scales so that the patient isn’t burdened with too many questions in advance of the appointment. The team will draw from existing scales and then create their own and validate it. “The questions will have to be vetted with patients through focus groups, and then the software platform [will have to be developed] so that patients can complete the survey online. Then we have to test it to see if providers and patients feel this is something that’s helpful in the clinical practice,” said Dr. Cuneo.

Will it change behavior?

If successful, the tool would be a welcome addition, according to Andrew Charles, MD, who was asked to comment on the work. “Epidemiological studies have identified these risk factors, but we haven’t had a way of operationalizing a strategy to reduce them systematically, so having some sort of tool that visualizes not just one but multiple risk factors is something I think could be helpful to address those factors more aggressively. The real question would be, if you put it in the hands of practitioners and patients, will they really be able to easily implement it and will it change behavior,” said Dr. Charles, who is a professor of neurology and director of the Goldberg Migraine Program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study received no funding. Dr. Cuneo and Dr. Charles have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE; Cuneo A et al. AHS 2020, Abstract 273715.

FROM AHS 2020

FDA approves new treatment for Dravet syndrome

Dravet syndrome is a rare childhood-onset epilepsy characterized by frequent, drug-resistant convulsive seizures that may contribute to intellectual disability and impairments in motor control, behavior, and cognition, as well as an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Dravet syndrome takes a “tremendous toll on both patients and their families. Fintepla offers an additional effective treatment option for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome,” Billy Dunn, MD, director, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

The FDA approved fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome based on the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials involving children ages 2 to 18 years with Dravet syndrome.

In both studies, children treated with fenfluramine experienced significantly greater reductions in the frequency of convulsive seizures than did their peers who received placebo. These reductions occurred within 3 to 4 weeks, and remained generally consistent over the 14- to 15-week treatment periods, the FDA said.

“There remains a huge unmet need for the many Dravet syndrome patients who continue to experience frequent severe seizures even while taking one or more of the currently available antiseizure medications,” Joseph Sullivan, MD, who worked on the fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome studies, said in a news release.

Given the “profound reductions” in convulsive seizure frequency seen in the clinical trials, combined with the “ongoing, robust safety monitoring,” fenfluramine offers “an extremely important treatment option for Dravet syndrome patients,” said Dr. Sullivan, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Fenfluramine is an anorectic agent that was used to treat obesity until it was removed from the market in 1997 over reports of increased risk of valvular heart disease when prescribed in higher doses and most often when prescribed with phentermine. The combination of the two drugs was known as fen-phen.

In the clinical trials of Dravet syndrome, the most common adverse reactions were decreased appetite; somnolence, sedation, lethargy; diarrhea; constipation; abnormal echocardiogram; fatigue, malaise, asthenia; ataxia, balance disorder, gait disturbance; increased blood pressure; drooling, salivary hypersecretion; pyrexia; upper respiratory tract infection; vomiting; decreased weight; fall; and status epilepticus.

The Fintepla label has a boxed warning stating that the drug is associated with valvular heart disease (VHD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Due to these risks, patients must undergo echocardiography before treatment, every 6 months during treatment, and once 3 to 6 months after treatment is stopped.

If signs of VHD, PAH, or other cardiac abnormalities are present, clinicians should weigh the benefits and risks of continuing treatment with Fintepla, the FDA said.

Fintepla is available only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, which requires physicians who prescribe the drug and pharmacies that dispense it to be certified in the Fintepla REMS and that patients be enrolled in the program.

As part of the REMS requirements, prescribers and patients must adhere to the required cardiac monitoring to receive the drug.

Fintepla will be available to certified prescribers in the United States in July. Zogenix is launching Zogenix Central, a comprehensive support service that will provide ongoing product assistance to patients, caregivers, and their medical teams. Further information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dravet syndrome is a rare childhood-onset epilepsy characterized by frequent, drug-resistant convulsive seizures that may contribute to intellectual disability and impairments in motor control, behavior, and cognition, as well as an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Dravet syndrome takes a “tremendous toll on both patients and their families. Fintepla offers an additional effective treatment option for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome,” Billy Dunn, MD, director, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

The FDA approved fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome based on the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials involving children ages 2 to 18 years with Dravet syndrome.

In both studies, children treated with fenfluramine experienced significantly greater reductions in the frequency of convulsive seizures than did their peers who received placebo. These reductions occurred within 3 to 4 weeks, and remained generally consistent over the 14- to 15-week treatment periods, the FDA said.

“There remains a huge unmet need for the many Dravet syndrome patients who continue to experience frequent severe seizures even while taking one or more of the currently available antiseizure medications,” Joseph Sullivan, MD, who worked on the fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome studies, said in a news release.

Given the “profound reductions” in convulsive seizure frequency seen in the clinical trials, combined with the “ongoing, robust safety monitoring,” fenfluramine offers “an extremely important treatment option for Dravet syndrome patients,” said Dr. Sullivan, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Fenfluramine is an anorectic agent that was used to treat obesity until it was removed from the market in 1997 over reports of increased risk of valvular heart disease when prescribed in higher doses and most often when prescribed with phentermine. The combination of the two drugs was known as fen-phen.

In the clinical trials of Dravet syndrome, the most common adverse reactions were decreased appetite; somnolence, sedation, lethargy; diarrhea; constipation; abnormal echocardiogram; fatigue, malaise, asthenia; ataxia, balance disorder, gait disturbance; increased blood pressure; drooling, salivary hypersecretion; pyrexia; upper respiratory tract infection; vomiting; decreased weight; fall; and status epilepticus.

The Fintepla label has a boxed warning stating that the drug is associated with valvular heart disease (VHD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Due to these risks, patients must undergo echocardiography before treatment, every 6 months during treatment, and once 3 to 6 months after treatment is stopped.

If signs of VHD, PAH, or other cardiac abnormalities are present, clinicians should weigh the benefits and risks of continuing treatment with Fintepla, the FDA said.

Fintepla is available only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, which requires physicians who prescribe the drug and pharmacies that dispense it to be certified in the Fintepla REMS and that patients be enrolled in the program.

As part of the REMS requirements, prescribers and patients must adhere to the required cardiac monitoring to receive the drug.

Fintepla will be available to certified prescribers in the United States in July. Zogenix is launching Zogenix Central, a comprehensive support service that will provide ongoing product assistance to patients, caregivers, and their medical teams. Further information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dravet syndrome is a rare childhood-onset epilepsy characterized by frequent, drug-resistant convulsive seizures that may contribute to intellectual disability and impairments in motor control, behavior, and cognition, as well as an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Dravet syndrome takes a “tremendous toll on both patients and their families. Fintepla offers an additional effective treatment option for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome,” Billy Dunn, MD, director, Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

The FDA approved fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome based on the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials involving children ages 2 to 18 years with Dravet syndrome.

In both studies, children treated with fenfluramine experienced significantly greater reductions in the frequency of convulsive seizures than did their peers who received placebo. These reductions occurred within 3 to 4 weeks, and remained generally consistent over the 14- to 15-week treatment periods, the FDA said.

“There remains a huge unmet need for the many Dravet syndrome patients who continue to experience frequent severe seizures even while taking one or more of the currently available antiseizure medications,” Joseph Sullivan, MD, who worked on the fenfluramine for Dravet syndrome studies, said in a news release.

Given the “profound reductions” in convulsive seizure frequency seen in the clinical trials, combined with the “ongoing, robust safety monitoring,” fenfluramine offers “an extremely important treatment option for Dravet syndrome patients,” said Dr. Sullivan, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Fenfluramine is an anorectic agent that was used to treat obesity until it was removed from the market in 1997 over reports of increased risk of valvular heart disease when prescribed in higher doses and most often when prescribed with phentermine. The combination of the two drugs was known as fen-phen.

In the clinical trials of Dravet syndrome, the most common adverse reactions were decreased appetite; somnolence, sedation, lethargy; diarrhea; constipation; abnormal echocardiogram; fatigue, malaise, asthenia; ataxia, balance disorder, gait disturbance; increased blood pressure; drooling, salivary hypersecretion; pyrexia; upper respiratory tract infection; vomiting; decreased weight; fall; and status epilepticus.

The Fintepla label has a boxed warning stating that the drug is associated with valvular heart disease (VHD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Due to these risks, patients must undergo echocardiography before treatment, every 6 months during treatment, and once 3 to 6 months after treatment is stopped.

If signs of VHD, PAH, or other cardiac abnormalities are present, clinicians should weigh the benefits and risks of continuing treatment with Fintepla, the FDA said.

Fintepla is available only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, which requires physicians who prescribe the drug and pharmacies that dispense it to be certified in the Fintepla REMS and that patients be enrolled in the program.

As part of the REMS requirements, prescribers and patients must adhere to the required cardiac monitoring to receive the drug.

Fintepla will be available to certified prescribers in the United States in July. Zogenix is launching Zogenix Central, a comprehensive support service that will provide ongoing product assistance to patients, caregivers, and their medical teams. Further information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Daily Recap: Healthy lifestyle may stave off dementia; Tentative evidence on marijuana for migraine

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

First reported U.S. case of COVID-19 linked to Guillain-Barré syndrome

The first official U.S. case of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19 has been reported by neurologists from Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, further supporting a link between the virus and neurologic complications, including GBS.

Physicians in China reported the first case that initially presented as acute GBS. Subsequently, physicians in Italy reported five cases of GBS in association with COVID-19.

“This onset is similar to a case report of acute Zika virus infection with concurrent GBS suggesting a parainfectious complication,” first author Sandeep Rana, MD, and colleagues noted. Read more.

Five healthy lifestyle choices tied to dramatic cut in dementia risk

Combining four of five healthy lifestyle choices has been linked to up to a 60% reduced risk for Alzheimer’s dementia in new research that strengthens ties between healthy behaviors and lower dementia risk. “I hope this study will motivate people to engage in a healthy lifestyle by not smoking, being physically and cognitively active, and having a high-quality diet,” lead investigator Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

They defined a healthy lifestyle score on the basis of the following factors: not smoking; engaging in 150 min/wk or more of physical exercise; light to moderate alcohol consumption; consuming a high-quality Mediterranean-DASH Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet (upper 40%); and engaging in late-life cognitive activities.

“What needs to be determined is how early should we start ‘behaving.’ We should all aim to score four to five factors across our entire lifespan, but this is not always feasible. So, when is the time to behave? Also, what is the relative weight of each of these factors?” said Luca Giliberto, MD, PhD. Read more.

Marijuana for migraine? Some tentative evidence

Medical marijuana may have promise for managing headache pain, according to results from a small study conducted at the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University. The researchers found general satisfaction with medical marijuana, more frequent use as an abortive medication rather than a preventative, and more than two-thirds using the inhaled form rather than oral.

“A lot of patients are interested in medical marijuana but don’t know how to integrate it into the therapy plan they already have – whether it should be just to treat bad headaches when they happen, or is it meant to be a preventive medicine they use every day? We have some data out there that it can be helpful, but not a lot of specific information to guide your recommendations,” said Jefferson headache fellow Claire Ceriani, MD, in an interview. Read more.

Inside Mercy’s mission to care for non-COVID patients in Los Angeles

When the hospital ship USNS Mercy departed San Diego’s Naval Station North Island on March 23, 2020, to support the Department of Defense efforts in Los Angeles during the coronavirus outbreak, Commander Erin Blevins remembers the crew’s excitement was palpable. “We normally do partnerships abroad and respond to tsunamis and earthquakes,” said Cdr. Blevins, MD, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist who served as director of medical services for the mission.

Between March 29 and May 15, about 1,071 medical personnel aboard the Mercy cared for 77 patients with an average age of 53 years who were referred from 11 Los Angeles area hospitals.

Care aboard the ship ranged from basic medical and surgical care to critical care and trauma. The most common procedures were cholecystectomies and orthopedic procedures, and the average length of stay was 4-5 days, according to Cdr. Blevins. Over the course of the mission, the medical professionals conducted 36 surgeries, 77 x-ray exams, 26 CT scans, and administered hundreds of ancillary studies ranging from routine labs to high-end x-rays and blood transfusion support. Special Feature.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

First reported U.S. case of COVID-19 linked to Guillain-Barré syndrome

The first official U.S. case of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19 has been reported by neurologists from Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, further supporting a link between the virus and neurologic complications, including GBS.

Physicians in China reported the first case that initially presented as acute GBS. Subsequently, physicians in Italy reported five cases of GBS in association with COVID-19.

“This onset is similar to a case report of acute Zika virus infection with concurrent GBS suggesting a parainfectious complication,” first author Sandeep Rana, MD, and colleagues noted. Read more.

Five healthy lifestyle choices tied to dramatic cut in dementia risk

Combining four of five healthy lifestyle choices has been linked to up to a 60% reduced risk for Alzheimer’s dementia in new research that strengthens ties between healthy behaviors and lower dementia risk. “I hope this study will motivate people to engage in a healthy lifestyle by not smoking, being physically and cognitively active, and having a high-quality diet,” lead investigator Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

They defined a healthy lifestyle score on the basis of the following factors: not smoking; engaging in 150 min/wk or more of physical exercise; light to moderate alcohol consumption; consuming a high-quality Mediterranean-DASH Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet (upper 40%); and engaging in late-life cognitive activities.

“What needs to be determined is how early should we start ‘behaving.’ We should all aim to score four to five factors across our entire lifespan, but this is not always feasible. So, when is the time to behave? Also, what is the relative weight of each of these factors?” said Luca Giliberto, MD, PhD. Read more.

Marijuana for migraine? Some tentative evidence

Medical marijuana may have promise for managing headache pain, according to results from a small study conducted at the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University. The researchers found general satisfaction with medical marijuana, more frequent use as an abortive medication rather than a preventative, and more than two-thirds using the inhaled form rather than oral.

“A lot of patients are interested in medical marijuana but don’t know how to integrate it into the therapy plan they already have – whether it should be just to treat bad headaches when they happen, or is it meant to be a preventive medicine they use every day? We have some data out there that it can be helpful, but not a lot of specific information to guide your recommendations,” said Jefferson headache fellow Claire Ceriani, MD, in an interview. Read more.

Inside Mercy’s mission to care for non-COVID patients in Los Angeles

When the hospital ship USNS Mercy departed San Diego’s Naval Station North Island on March 23, 2020, to support the Department of Defense efforts in Los Angeles during the coronavirus outbreak, Commander Erin Blevins remembers the crew’s excitement was palpable. “We normally do partnerships abroad and respond to tsunamis and earthquakes,” said Cdr. Blevins, MD, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist who served as director of medical services for the mission.

Between March 29 and May 15, about 1,071 medical personnel aboard the Mercy cared for 77 patients with an average age of 53 years who were referred from 11 Los Angeles area hospitals.

Care aboard the ship ranged from basic medical and surgical care to critical care and trauma. The most common procedures were cholecystectomies and orthopedic procedures, and the average length of stay was 4-5 days, according to Cdr. Blevins. Over the course of the mission, the medical professionals conducted 36 surgeries, 77 x-ray exams, 26 CT scans, and administered hundreds of ancillary studies ranging from routine labs to high-end x-rays and blood transfusion support. Special Feature.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

First reported U.S. case of COVID-19 linked to Guillain-Barré syndrome

The first official U.S. case of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19 has been reported by neurologists from Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, further supporting a link between the virus and neurologic complications, including GBS.

Physicians in China reported the first case that initially presented as acute GBS. Subsequently, physicians in Italy reported five cases of GBS in association with COVID-19.

“This onset is similar to a case report of acute Zika virus infection with concurrent GBS suggesting a parainfectious complication,” first author Sandeep Rana, MD, and colleagues noted. Read more.

Five healthy lifestyle choices tied to dramatic cut in dementia risk

Combining four of five healthy lifestyle choices has been linked to up to a 60% reduced risk for Alzheimer’s dementia in new research that strengthens ties between healthy behaviors and lower dementia risk. “I hope this study will motivate people to engage in a healthy lifestyle by not smoking, being physically and cognitively active, and having a high-quality diet,” lead investigator Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

They defined a healthy lifestyle score on the basis of the following factors: not smoking; engaging in 150 min/wk or more of physical exercise; light to moderate alcohol consumption; consuming a high-quality Mediterranean-DASH Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet (upper 40%); and engaging in late-life cognitive activities.

“What needs to be determined is how early should we start ‘behaving.’ We should all aim to score four to five factors across our entire lifespan, but this is not always feasible. So, when is the time to behave? Also, what is the relative weight of each of these factors?” said Luca Giliberto, MD, PhD. Read more.

Marijuana for migraine? Some tentative evidence

Medical marijuana may have promise for managing headache pain, according to results from a small study conducted at the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University. The researchers found general satisfaction with medical marijuana, more frequent use as an abortive medication rather than a preventative, and more than two-thirds using the inhaled form rather than oral.

“A lot of patients are interested in medical marijuana but don’t know how to integrate it into the therapy plan they already have – whether it should be just to treat bad headaches when they happen, or is it meant to be a preventive medicine they use every day? We have some data out there that it can be helpful, but not a lot of specific information to guide your recommendations,” said Jefferson headache fellow Claire Ceriani, MD, in an interview. Read more.

Inside Mercy’s mission to care for non-COVID patients in Los Angeles

When the hospital ship USNS Mercy departed San Diego’s Naval Station North Island on March 23, 2020, to support the Department of Defense efforts in Los Angeles during the coronavirus outbreak, Commander Erin Blevins remembers the crew’s excitement was palpable. “We normally do partnerships abroad and respond to tsunamis and earthquakes,” said Cdr. Blevins, MD, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist who served as director of medical services for the mission.

Between March 29 and May 15, about 1,071 medical personnel aboard the Mercy cared for 77 patients with an average age of 53 years who were referred from 11 Los Angeles area hospitals.

Care aboard the ship ranged from basic medical and surgical care to critical care and trauma. The most common procedures were cholecystectomies and orthopedic procedures, and the average length of stay was 4-5 days, according to Cdr. Blevins. Over the course of the mission, the medical professionals conducted 36 surgeries, 77 x-ray exams, 26 CT scans, and administered hundreds of ancillary studies ranging from routine labs to high-end x-rays and blood transfusion support. Special Feature.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

First reported U.S. case of COVID-19 linked to Guillain-Barré syndrome

further supporting a link between the virus and neurologic complications, including GBS.

Physicians in China reported the first case of COVID-19 that initially presented as acute GBS. The patient was a 61-year-old woman returning home from Wuhan during the pandemic.

Subsequently, physicians in Italy reported five cases of GBS in association with COVID-19.

The first U.S. case is described in the June issue of the Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease.

Like cases from China and Italy, the U.S. patient’s symptoms of GBS reportedly occurred within days of being infected with SARS-CoV-2. “This onset is similar to a case report of acute Zika virus infection with concurrent GBS suggesting a parainfectious complication,” first author Sandeep Rana, MD, and colleagues noted.

The 54-year-old man was transferred to Allegheny General Hospital after developing ascending limb weakness and numbness that followed symptoms of a respiratory infection. Two weeks earlier, he initially developed rhinorrhea, odynophagia, fevers, chills, and night sweats. The man reported that his wife had tested positive for COVID-19 and that his symptoms started soon after her illness. The man also tested positive for COVID-19.

His deficits were characterized by quadriparesis and areflexia, burning dysesthesias, mild ophthalmoparesis, and dysautonomia. He did not have the loss of smell and taste documented in other COVID-19 patients. He briefly required mechanical ventilation and was successfully weaned after receiving a course of intravenous immunoglobulin.

Compared with other cases reported in the literature, the unique clinical features in the U.S. case are urinary retention secondary to dysautonomia and ocular symptoms of diplopia. These highlight the variability in the clinical presentation of GBS associated with COVID-19, the researchers noted.

They added that, with the Pittsburgh patient, electrophysiological findings were typical of demyelinating polyneuropathy seen in patients with GBS. The case series from Italy suggests that axonal variants could be as common in COVID-19–associated GBS.

“Although the number of documented cases internationally is notably small to date, it’s not completely surprising that a COVID-19 diagnosis may lead to a patient developing GBS. The increase of inflammation and inflammatory cells caused by the infection may trigger an irregular immune response that leads to the hallmark symptoms of this neurological disorder,” Dr. Rana said in a news release.

“Since GBS can significantly affect the respiratory system and other vital organs being pushed into overdrive during a COVID-19 immune response, it will be critically important to further investigate and understand this potential connection,” he added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

further supporting a link between the virus and neurologic complications, including GBS.

Physicians in China reported the first case of COVID-19 that initially presented as acute GBS. The patient was a 61-year-old woman returning home from Wuhan during the pandemic.

Subsequently, physicians in Italy reported five cases of GBS in association with COVID-19.

The first U.S. case is described in the June issue of the Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease.

Like cases from China and Italy, the U.S. patient’s symptoms of GBS reportedly occurred within days of being infected with SARS-CoV-2. “This onset is similar to a case report of acute Zika virus infection with concurrent GBS suggesting a parainfectious complication,” first author Sandeep Rana, MD, and colleagues noted.

The 54-year-old man was transferred to Allegheny General Hospital after developing ascending limb weakness and numbness that followed symptoms of a respiratory infection. Two weeks earlier, he initially developed rhinorrhea, odynophagia, fevers, chills, and night sweats. The man reported that his wife had tested positive for COVID-19 and that his symptoms started soon after her illness. The man also tested positive for COVID-19.

His deficits were characterized by quadriparesis and areflexia, burning dysesthesias, mild ophthalmoparesis, and dysautonomia. He did not have the loss of smell and taste documented in other COVID-19 patients. He briefly required mechanical ventilation and was successfully weaned after receiving a course of intravenous immunoglobulin.

Compared with other cases reported in the literature, the unique clinical features in the U.S. case are urinary retention secondary to dysautonomia and ocular symptoms of diplopia. These highlight the variability in the clinical presentation of GBS associated with COVID-19, the researchers noted.

They added that, with the Pittsburgh patient, electrophysiological findings were typical of demyelinating polyneuropathy seen in patients with GBS. The case series from Italy suggests that axonal variants could be as common in COVID-19–associated GBS.

“Although the number of documented cases internationally is notably small to date, it’s not completely surprising that a COVID-19 diagnosis may lead to a patient developing GBS. The increase of inflammation and inflammatory cells caused by the infection may trigger an irregular immune response that leads to the hallmark symptoms of this neurological disorder,” Dr. Rana said in a news release.

“Since GBS can significantly affect the respiratory system and other vital organs being pushed into overdrive during a COVID-19 immune response, it will be critically important to further investigate and understand this potential connection,” he added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

further supporting a link between the virus and neurologic complications, including GBS.

Physicians in China reported the first case of COVID-19 that initially presented as acute GBS. The patient was a 61-year-old woman returning home from Wuhan during the pandemic.

Subsequently, physicians in Italy reported five cases of GBS in association with COVID-19.

The first U.S. case is described in the June issue of the Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease.

Like cases from China and Italy, the U.S. patient’s symptoms of GBS reportedly occurred within days of being infected with SARS-CoV-2. “This onset is similar to a case report of acute Zika virus infection with concurrent GBS suggesting a parainfectious complication,” first author Sandeep Rana, MD, and colleagues noted.

The 54-year-old man was transferred to Allegheny General Hospital after developing ascending limb weakness and numbness that followed symptoms of a respiratory infection. Two weeks earlier, he initially developed rhinorrhea, odynophagia, fevers, chills, and night sweats. The man reported that his wife had tested positive for COVID-19 and that his symptoms started soon after her illness. The man also tested positive for COVID-19.

His deficits were characterized by quadriparesis and areflexia, burning dysesthesias, mild ophthalmoparesis, and dysautonomia. He did not have the loss of smell and taste documented in other COVID-19 patients. He briefly required mechanical ventilation and was successfully weaned after receiving a course of intravenous immunoglobulin.

Compared with other cases reported in the literature, the unique clinical features in the U.S. case are urinary retention secondary to dysautonomia and ocular symptoms of diplopia. These highlight the variability in the clinical presentation of GBS associated with COVID-19, the researchers noted.

They added that, with the Pittsburgh patient, electrophysiological findings were typical of demyelinating polyneuropathy seen in patients with GBS. The case series from Italy suggests that axonal variants could be as common in COVID-19–associated GBS.

“Although the number of documented cases internationally is notably small to date, it’s not completely surprising that a COVID-19 diagnosis may lead to a patient developing GBS. The increase of inflammation and inflammatory cells caused by the infection may trigger an irregular immune response that leads to the hallmark symptoms of this neurological disorder,” Dr. Rana said in a news release.

“Since GBS can significantly affect the respiratory system and other vital organs being pushed into overdrive during a COVID-19 immune response, it will be critically important to further investigate and understand this potential connection,” he added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A tribute to Edward Ross Ritvo, MD, 1930-2020

Reflections on loss amid COVID-19

I sit here on Father’s Day during a global pandemic and can’t help but think of Mark Twain’s quote, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” Isn’t that what calls us to our profession? When friends ask if I have watched a particular movie or TV show, I almost always say no. Why would I? Day after day at “work” I am hearing the most remarkable stories – many unfolding right before my eyes.

My Dad’s story is no less remarkable. As he was a pioneer in our field, I hope you will allow me to share a few recollections.

June 10, just 10 days after turning 90, Dad died peacefully in his home. His obituary, written by James McCracken, MD, says: “He was an internationally known child psychiatrist who, with colleagues, formed the vanguard of UCLA researchers establishing the biomedical basis of autism in the 1960s despite the prevailing psychological theories of the day ... who would later break new ground in identifying the role of genetics, sleep, and neurophysiological differences, perinatal risk factors, and biomarkers relating to autism and autism risk.”

Dad had extensive training in psychoanalysis and worked hard to maintain expertise in both the psychological and biological arenas. While he helped established autism as a neurologic disease and advocated for DSM criteria changes, he continued teaching Psychodynamic Theory of Personality to the UCLA medical students and maintained a clinical practice based in psychotherapeutic techniques. He was practicing biopsychosocial medicine long before the concept was articulated.

He conducted the first epidemiologic survey of autism in the state of Utah. He chose Utah because the Mormons keep perfect genealogical records. He identified multiple families with more than one child affected as well as examining, pre-, peri-, and postnatal factors affecting these families. Being a maverick has its challenges. One paper about parents with mild autism was rejected from publication seven times before a watered-down version of clinical vignettes finally got accepted. In collaboration with his wife, Riva Ariella Ritvo, he developed the Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale–Revised, (RAADS-R) still in use today.

Dad’s career was complicated by medical issues beginning in his 40s when he had a near-fatal heart attack at the top of Mammoth Mountain while skiing. After struggling for 20 years, he ultimately had a heart transplant at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center at 69 years old. Months after the transplant, he was back at work. He was unstoppable and maintained his optimism and great sense of humor throughout this complicated ordeal. He always remembered his commitment to his donor and his new heart, and worked out every day. Living to 90 was against all the odds.

Dad also persevered throughout his youngest son’s 10-year battle with Ewing’s sarcoma. Despite losing Max in 2016, Dad was active in research and clinical practice until the very end. He was doing telepsychiatry with patients in prisons and rehabilitation hospitals the last few years because he was too weak to travel to an office. He continued his research, and his last paper on eye movement responses as a possible biological marker of autism was published in February 2020.

Although Dad did not have COVID-19, the social isolation and stress of the last few months hastened his decline. The last week in the hospital with no visitors was too much for such a social man, and he died days after he was discharged. Always a trailblazer, Dad’s Zoom funeral was watched across the country by his children, grandchildren, extended family, and friends. Choosing to honor his wish to be cautious in this pandemic, we remained sheltering in place.

As Dad was the ultimate professor, I know he would want us to learn from his life and his passing. We are in an accelerated growth phase now as our lives and the lives of our patients are radically altered.

I hope, like Dad, we can choose to feel nourished by our meaningful work as we travel through life’s ups and downs. We must learn new ways to care for ourselves, our families, and our patients during these challenging times. We must find ways to mourn and celebrate those lost during the pandemic.

I know Dad would love synchronicity that I spent Father’s Day writing about him for Clinical Psychiatry News! Thank you for giving me this gift of reflection on this special day.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018) and is the founder of the Bekindr Global Initiative, a movement aimed at cultivating kindness in the world. Dr. Ritvo also is the cofounder of the Bold Beauty Project, a nonprofit group that pairs women with disabilities with photographers who create art exhibitions to raise awareness.

Reflections on loss amid COVID-19

Reflections on loss amid COVID-19

I sit here on Father’s Day during a global pandemic and can’t help but think of Mark Twain’s quote, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” Isn’t that what calls us to our profession? When friends ask if I have watched a particular movie or TV show, I almost always say no. Why would I? Day after day at “work” I am hearing the most remarkable stories – many unfolding right before my eyes.

My Dad’s story is no less remarkable. As he was a pioneer in our field, I hope you will allow me to share a few recollections.

June 10, just 10 days after turning 90, Dad died peacefully in his home. His obituary, written by James McCracken, MD, says: “He was an internationally known child psychiatrist who, with colleagues, formed the vanguard of UCLA researchers establishing the biomedical basis of autism in the 1960s despite the prevailing psychological theories of the day ... who would later break new ground in identifying the role of genetics, sleep, and neurophysiological differences, perinatal risk factors, and biomarkers relating to autism and autism risk.”

Dad had extensive training in psychoanalysis and worked hard to maintain expertise in both the psychological and biological arenas. While he helped established autism as a neurologic disease and advocated for DSM criteria changes, he continued teaching Psychodynamic Theory of Personality to the UCLA medical students and maintained a clinical practice based in psychotherapeutic techniques. He was practicing biopsychosocial medicine long before the concept was articulated.

He conducted the first epidemiologic survey of autism in the state of Utah. He chose Utah because the Mormons keep perfect genealogical records. He identified multiple families with more than one child affected as well as examining, pre-, peri-, and postnatal factors affecting these families. Being a maverick has its challenges. One paper about parents with mild autism was rejected from publication seven times before a watered-down version of clinical vignettes finally got accepted. In collaboration with his wife, Riva Ariella Ritvo, he developed the Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale–Revised, (RAADS-R) still in use today.

Dad’s career was complicated by medical issues beginning in his 40s when he had a near-fatal heart attack at the top of Mammoth Mountain while skiing. After struggling for 20 years, he ultimately had a heart transplant at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center at 69 years old. Months after the transplant, he was back at work. He was unstoppable and maintained his optimism and great sense of humor throughout this complicated ordeal. He always remembered his commitment to his donor and his new heart, and worked out every day. Living to 90 was against all the odds.

Dad also persevered throughout his youngest son’s 10-year battle with Ewing’s sarcoma. Despite losing Max in 2016, Dad was active in research and clinical practice until the very end. He was doing telepsychiatry with patients in prisons and rehabilitation hospitals the last few years because he was too weak to travel to an office. He continued his research, and his last paper on eye movement responses as a possible biological marker of autism was published in February 2020.

Although Dad did not have COVID-19, the social isolation and stress of the last few months hastened his decline. The last week in the hospital with no visitors was too much for such a social man, and he died days after he was discharged. Always a trailblazer, Dad’s Zoom funeral was watched across the country by his children, grandchildren, extended family, and friends. Choosing to honor his wish to be cautious in this pandemic, we remained sheltering in place.

As Dad was the ultimate professor, I know he would want us to learn from his life and his passing. We are in an accelerated growth phase now as our lives and the lives of our patients are radically altered.

I hope, like Dad, we can choose to feel nourished by our meaningful work as we travel through life’s ups and downs. We must learn new ways to care for ourselves, our families, and our patients during these challenging times. We must find ways to mourn and celebrate those lost during the pandemic.

I know Dad would love synchronicity that I spent Father’s Day writing about him for Clinical Psychiatry News! Thank you for giving me this gift of reflection on this special day.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018) and is the founder of the Bekindr Global Initiative, a movement aimed at cultivating kindness in the world. Dr. Ritvo also is the cofounder of the Bold Beauty Project, a nonprofit group that pairs women with disabilities with photographers who create art exhibitions to raise awareness.