User login

Influenza vaccine efficacy called undiminished in MS

, Jackie Nguyen reported at the virtual annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). She presented a systematic review and meta-analysis of nine published cohort studies including 417 MS patients and more than 500 healthy controls, all of whom received inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine.

The impetus for this project was a recognition that the great majority of the research on the impact of influenza vaccine in patients with MS has focused on safety and MS relapse rates. In contrast, the nine studies included in the meta-analysis contained data on influenza vaccine efficacy as reflected in the ability to mount an adequate immune response. This was defined in standard fashion either by seroconversion, which required at least a fourfold increase in antibody titers following vaccination, or seroprotection, with a postvaccination antihemagglutination immunoglobulin G titer of at least 40. The analysis included patients with MS irrespective of disease duration or severity or treatment regimen, noted Ms. Nguyen, a third-year medical student at Nova Southeastern University College of Allopathic Medicine in Davie, Fla.

The researchers found that there was no significant difference between patients with MS and healthy controls in the rates of an adequate immune response for influenza H1N1, H3N2, or influenza B virus. “The vaccine should thus continue to be recommended for MS patients, as the data shows it to be efficacious,” she said.

Her conclusion is consistent with guidance provided in the American Academy of Neurology’s 2019 practice guideline update on immunization in MS, highlighted elsewhere at CMSC 2020 in a presentation by Marijean Buhse, PhD, of Stony Brook University in New York.

The guideline, updated for the first time in 17 years, states that all MS patients should be advised to receive influenza vaccine annually: “With known risks of exacerbation and other morbidity with influenza infection and no identified risks of exacerbation with influenza vaccines, benefits of influenza vaccination outweigh the risks in most scenarios. The exception involves the relatively few MS patients having a specific contraindication to the influenza vaccine, such as a previous severe reaction, noted Dr. Buhse, who wasn’t involved in developing the evidence-based guidelines.

The available evidence indicates that some but not all disease-modifying therapies for MS reduce the effectiveness of vaccination against influenza.

According to the guideline, “it is possible” that persons with MS being treated with glatiramer acetate have a reduced likelihood of seroprotection from influenza vaccine, a conclusion the guidelines committee drew with “low confidence in the evidence.” Further, the guideline states that “it is probable” MS patients on fingolimod have a lower likelihood of obtaining seroprotection from influenza vaccine than patients not on the drug, with moderate confidence in the evidence. Also, it is deemed probable that patients with MS who are taking mitoxantrone have a reduced likelihood of response to influenza vaccination, compared with healthy controls. But it is probable that patients with MS who are receiving interferon-beta have no diminution in the likelihood of seroprotection. According to the guideline, there is insufficient evidence to say whether patients with MS who are on natalizumab, teriflunomide, or methotrexate have a diminished response to influenza vaccination.

Dr. Buhse noted that rituximab is off-label therapy for MS, so there are no data available regarding the likelihood of seroprotection in response to influenza vaccination in that setting. However, rituximab profoundly decreases the immunogenicity of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in rheumatoid arthritis patients. It is therefore recommended that inactivated influenza vaccine be given to patients with MS at least 2 weeks prior to starting rituximab or 6 months after the last dose in order to optimize the humoral results. Ms. Nguyen reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation. Dr. Buhse reported having received honoraria from Genzyme and Biogen.

, Jackie Nguyen reported at the virtual annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). She presented a systematic review and meta-analysis of nine published cohort studies including 417 MS patients and more than 500 healthy controls, all of whom received inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine.

The impetus for this project was a recognition that the great majority of the research on the impact of influenza vaccine in patients with MS has focused on safety and MS relapse rates. In contrast, the nine studies included in the meta-analysis contained data on influenza vaccine efficacy as reflected in the ability to mount an adequate immune response. This was defined in standard fashion either by seroconversion, which required at least a fourfold increase in antibody titers following vaccination, or seroprotection, with a postvaccination antihemagglutination immunoglobulin G titer of at least 40. The analysis included patients with MS irrespective of disease duration or severity or treatment regimen, noted Ms. Nguyen, a third-year medical student at Nova Southeastern University College of Allopathic Medicine in Davie, Fla.

The researchers found that there was no significant difference between patients with MS and healthy controls in the rates of an adequate immune response for influenza H1N1, H3N2, or influenza B virus. “The vaccine should thus continue to be recommended for MS patients, as the data shows it to be efficacious,” she said.

Her conclusion is consistent with guidance provided in the American Academy of Neurology’s 2019 practice guideline update on immunization in MS, highlighted elsewhere at CMSC 2020 in a presentation by Marijean Buhse, PhD, of Stony Brook University in New York.

The guideline, updated for the first time in 17 years, states that all MS patients should be advised to receive influenza vaccine annually: “With known risks of exacerbation and other morbidity with influenza infection and no identified risks of exacerbation with influenza vaccines, benefits of influenza vaccination outweigh the risks in most scenarios. The exception involves the relatively few MS patients having a specific contraindication to the influenza vaccine, such as a previous severe reaction, noted Dr. Buhse, who wasn’t involved in developing the evidence-based guidelines.

The available evidence indicates that some but not all disease-modifying therapies for MS reduce the effectiveness of vaccination against influenza.

According to the guideline, “it is possible” that persons with MS being treated with glatiramer acetate have a reduced likelihood of seroprotection from influenza vaccine, a conclusion the guidelines committee drew with “low confidence in the evidence.” Further, the guideline states that “it is probable” MS patients on fingolimod have a lower likelihood of obtaining seroprotection from influenza vaccine than patients not on the drug, with moderate confidence in the evidence. Also, it is deemed probable that patients with MS who are taking mitoxantrone have a reduced likelihood of response to influenza vaccination, compared with healthy controls. But it is probable that patients with MS who are receiving interferon-beta have no diminution in the likelihood of seroprotection. According to the guideline, there is insufficient evidence to say whether patients with MS who are on natalizumab, teriflunomide, or methotrexate have a diminished response to influenza vaccination.

Dr. Buhse noted that rituximab is off-label therapy for MS, so there are no data available regarding the likelihood of seroprotection in response to influenza vaccination in that setting. However, rituximab profoundly decreases the immunogenicity of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in rheumatoid arthritis patients. It is therefore recommended that inactivated influenza vaccine be given to patients with MS at least 2 weeks prior to starting rituximab or 6 months after the last dose in order to optimize the humoral results. Ms. Nguyen reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation. Dr. Buhse reported having received honoraria from Genzyme and Biogen.

, Jackie Nguyen reported at the virtual annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). She presented a systematic review and meta-analysis of nine published cohort studies including 417 MS patients and more than 500 healthy controls, all of whom received inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine.

The impetus for this project was a recognition that the great majority of the research on the impact of influenza vaccine in patients with MS has focused on safety and MS relapse rates. In contrast, the nine studies included in the meta-analysis contained data on influenza vaccine efficacy as reflected in the ability to mount an adequate immune response. This was defined in standard fashion either by seroconversion, which required at least a fourfold increase in antibody titers following vaccination, or seroprotection, with a postvaccination antihemagglutination immunoglobulin G titer of at least 40. The analysis included patients with MS irrespective of disease duration or severity or treatment regimen, noted Ms. Nguyen, a third-year medical student at Nova Southeastern University College of Allopathic Medicine in Davie, Fla.

The researchers found that there was no significant difference between patients with MS and healthy controls in the rates of an adequate immune response for influenza H1N1, H3N2, or influenza B virus. “The vaccine should thus continue to be recommended for MS patients, as the data shows it to be efficacious,” she said.

Her conclusion is consistent with guidance provided in the American Academy of Neurology’s 2019 practice guideline update on immunization in MS, highlighted elsewhere at CMSC 2020 in a presentation by Marijean Buhse, PhD, of Stony Brook University in New York.

The guideline, updated for the first time in 17 years, states that all MS patients should be advised to receive influenza vaccine annually: “With known risks of exacerbation and other morbidity with influenza infection and no identified risks of exacerbation with influenza vaccines, benefits of influenza vaccination outweigh the risks in most scenarios. The exception involves the relatively few MS patients having a specific contraindication to the influenza vaccine, such as a previous severe reaction, noted Dr. Buhse, who wasn’t involved in developing the evidence-based guidelines.

The available evidence indicates that some but not all disease-modifying therapies for MS reduce the effectiveness of vaccination against influenza.

According to the guideline, “it is possible” that persons with MS being treated with glatiramer acetate have a reduced likelihood of seroprotection from influenza vaccine, a conclusion the guidelines committee drew with “low confidence in the evidence.” Further, the guideline states that “it is probable” MS patients on fingolimod have a lower likelihood of obtaining seroprotection from influenza vaccine than patients not on the drug, with moderate confidence in the evidence. Also, it is deemed probable that patients with MS who are taking mitoxantrone have a reduced likelihood of response to influenza vaccination, compared with healthy controls. But it is probable that patients with MS who are receiving interferon-beta have no diminution in the likelihood of seroprotection. According to the guideline, there is insufficient evidence to say whether patients with MS who are on natalizumab, teriflunomide, or methotrexate have a diminished response to influenza vaccination.

Dr. Buhse noted that rituximab is off-label therapy for MS, so there are no data available regarding the likelihood of seroprotection in response to influenza vaccination in that setting. However, rituximab profoundly decreases the immunogenicity of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in rheumatoid arthritis patients. It is therefore recommended that inactivated influenza vaccine be given to patients with MS at least 2 weeks prior to starting rituximab or 6 months after the last dose in order to optimize the humoral results. Ms. Nguyen reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation. Dr. Buhse reported having received honoraria from Genzyme and Biogen.

REPORTING FROM CMSC 2020

Healthy Aging Project-Brain: A Psychoeducational and Motivational Group for Older Veterans

With a rapidly growing older adult population, increased attention has been given to cognitive changes that occur with age, with a focus on optimizing the cognitive health of aging individuals.1 Given the absence of pharmaceutical treatments to prevent cognitive decline, there is an increased need for health care systems to offer alternative or behavioral interventions that can mitigate the effects of cognitive decline in aging.

Notably, many individuals are able to maintain or even improve cognitive functioning throughout their lifespan, with some research implicating health behaviors as an important factor for promoting brain health with age. Specifically, sleep, exercise, eating habits, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation have been linked to improved cognitive functioning.2-8 In addition to the potential benefits for brain health, there is evidence that greater investment in attaining health goals is associated with subjective reports of higher well-being, fewer mental health symptoms, lower physical health stresses, decreased caregiver burden, and increased functional independence linked with longer independent living.9 The latter has a substantial financial impact, such that the positive consequence of increased independence is likely staving off the need for admission to assisted living and adult family homes, which can be costly.

Despite the role of health behaviors in brain aging and overall health and functioning, research indicates that only a small number of older adults (12.8%) follow recommended guidelines for healthy lifestyle factors.10 Education has been identified as one factor associated with the likelihood of engaging in positive health behaviors, prompting the delivery of health-education interventions. Most psychoeducational interventions have traditionally focused on one aspect of behavior change at a time (eg, sleep); however, Gross and colleaguesconducted a meta-analysis of cognitive interventions and in addition to the overall positive benefits (effect size 0.38), they also found suggestive evidence that interventions that combined multiple training strategies were associated with larger training gains (P = .04) after adjusting for multiple comparisons.11 For example, Miller and colleagues found a significant improvement on both subjective and objective measures of memory following a multicomponent approach that combined training in memory skills, stress reduction, nutrition, and physical activity.12

In addition to the potential positive impacts of health behaviors on brain health, findings suggest that targeted emphasis on health behavior change may have the potential to stave off mild cognitiveimpairment (MCI) or dementia even if for a short time. Given the increasing prevalence rates of MCI with age (6.7% in adults aged 60-64 years, reaching 25.2% in adults aged 80-84 years13) and dementia (prevalence of MCI converting to dementia is 18-40%14), as well as the corresponding emotional, financial, and family-oriented consequences (eg, impact on the well-being of family caregivers), the need for behavioral interventions that seek to optimize brain health is becoming increasingly apparent.

More than 9 million veterans are now aged ≥ 65 years.15 In addition to representing nearly half of all veterans and a sizable portion of aging adults in the US, older veterans are at increased risk of frailty, mortality, and high rates of chronic medical/mental health conditions that can lead to accelerated cognitive aging.6-17 Together, these conditions highlight the importance of developing comprehensive psychoeducational and behavioral interventions in this population. To address this need, we developed a novel psychoeducation and behavior change group called the Healthy Aging Project-Brain (HAP-B, pronounced “happy”). The HAP-B intervention was designed to promote healthy brain aging by using empirically supported health behavior change strategies, including education, personalized goal setting, and community support. The primary aim of this project was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable (eg, could be implemented in our setting, was appropriate for a veteran population) and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Methods

We recruited veterans aged ≥ 50 years through primary care clinics and self-referrals via flyers in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS), Seattle Division hospital. We targeted the “worried well” and welcomed veterans with MCI and mental health diagnoses. Notably, if there were significant mental health and/or substance use concerns, we encouraged veterans to seek focused care and stabilization prior to or concurrent with group participation. Exclusion criteria included presence of suicidality/homicidality, untreated or unstable substance use disorder, or a diagnosis of dementia. Exclusion criteria were assessed by the referring health care providers (HCPs), when appropriate, and through a health record review. Group facilitators used their clinical judgment to monitor participants if they began experiencing more severe cognitive impairment or acute mental health concerns. Although we did not encounter any of these instances, facilitators were prepared to discuss any concerns with the veteran and their referring HCP. Participants sampled were from 1 of 5 groups offered between January 2018 and March 2019. A waiver from the institutional review board was obtained after meeting criteria for quality improvement/quality assurance (QI/QA) for this study.

Procedures

At the initial stages of development, our team conducted a needs assessment to identify health-related areas where HCPs felt veterans would benefit from additional education and support. The needs assessment was conducted across primary care, geriatric extended care, and the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC) at VAPSHCS. Combining the needs assessment results with the available research base, we identified sleep, physical activity, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation as areas for focus. Notably, although nutrition has been identified as an important factor in cognitive aging, a diet and nutrition class was already available to older veterans at the Seattle VA; hence, we chose to limit overlap by not covering this topic in our group.

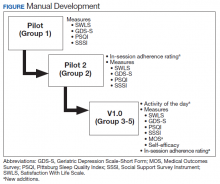

The group was offered on a quarterly basis as six 90-minute psychoeducational classes to allow time for didactics, discussion, and practice without overloading participants with information. Each group consisted of 4 to 9 veterans led by 2 cofacilitators. Group structure allowed for feedback and ideas from group members as well as accountability for engaging in behavior change. Cognitive functioning was not formally evaluated. Attendees were asked but not required to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. In addition at the completion of each group, feedback was collected from veterans and used to modify group content (Figure).

Two pilot groups were implemented in early and mid-2018 with iterative changes after each group. Then we revised the assessment battery and implemented the current version (v1.0), which was first offered in the fall of 2018 and was used with the final 3 groups. Noteworthy changes included weekly check-ins to assess use of health behavior logs and progress toward individual goals, additional pre-and postgroup measures, and in vivo skills practice relevant to the topic being discussed that day.

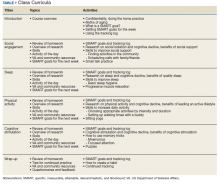

Each session began with a check-in, which included a review of daily logs and SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant/realistic, and timebound) goals from the previous week.18 This allowed for praise/reinforcement of health behaviors as well as discussion of potential barriers. Second, an overview of research focusing on the relationship between aging, brain health, and the topic of the day was presented. As an example, in the discussion of social engagement, research was presented about the link between social isolation and cognitive decline; the indirect benefits of social support (eg, social support is linked to improved physical and mental health, which, in turn, is associated with less cognitive decline); and the direct benefits of social support (eg, high levels of emotional support are associated with better cognitive function) (Table 1).6

Next, facilitators reviewed skills and strategies to improve functioning in the topic of discussion. During the social engagement group, for example, facilitators discussed tips to improve social skills (eg, asking open-ended questions) and how to build social support into a daily routine (eg, scheduling weekly phone calls with family and friends). Following this discussion of skills, an activity was practiced, reinforcing learned material. During the social engagement group, veterans were invited to use small talk strategies with fellow group members. Finally, group sessions ended with each participant identifying a SMART goal for the coming week and troubleshooting potential barriers to success. SMART goals were kept broad, so veterans could choose a goal related to the topic discussed at the group that day (eg, scheduling a phone call with a friend twice in the coming week during the social engagement-focused group) or choose any other goal to focus on (eg, a sleep-related goal). Similarly, goals could change week to week, or could remain the same throughout the 6-week classes.

Measures

The questionnaires used for QI/QA analyses included the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-S); Social Support Survey Instrument (SSSI); Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); Medical Outcomes Survey-Short Form (MOS-36 SF); and a self-efficacy scale (adapted from Huckans and colleagues for traumatic brain injury).19-24 Written feedback was collected at the end of the last group to assess perception of progress, self-perceived behavior change, what was helpful or unhelpful, and how likely the participants were to recommend the group to other veterans (0 to 3, very unlikely to very likely).

To promote consistency with other health and behavior change interventions at the VA, HAP-B used resources from the Whole Health model SMART goals. Research supports the use of self-monitoring techniques like SMART goals for behavior change.25

To facilitate skills practice and self-monitoring between classes, veterans were asked to complete 2 homework assignments. First, at the end of each group, each veteran identified a specific SMART goal to focus on and track in the coming week. Goals were unique to each veteran and allowed to change from week to week. Group discussion around SMART goals involved plans for how to address potential barriers; progress toward goals was discussed at the beginning of the following group. Second, veterans were asked to complete a worksheet used to track progress toward the weekly SMART goal and the specific health behaviors related to the 4 domains targeted by HAP-B. For example, when tracking sleep behaviors, veterans noted bedtime, waketime, number of times they woke up during the night, and length of daytime naps if applicable. Tracking logs were provided at the end of each class for personal purposes only. We asked veterans to rate themselves each week on whether they used the tracking sheet to monitor health behaviors; and how successful they were at accomplishing their previously identified SMART goal. We recorded responses on a 0 to 2 scale (0, not good; 1, fair; 2, good). This rating system was developed and implemented in later groups to promote self-monitoring, accountability, and discussion of potential barriers. However, due to the small sample that completed these ratings and the absence of objective corroborating data, these ratings were not included in the current analyses.

Every participant received a manual in binder format, which provided the didactic information for each group session, skills and strategies discussed in each session, and relevant resources in both the VA and community. For example, social engagement resources included information about volunteer opportunities, VA groups that focus on developing interpersonal skills, and recommendations from past group members on social events (eg, dance lessons at a senior center). We also developed a facilitator version of the manual in which we added comments and guidance on topics for discussion. Materials were developed with the goal of optimizing the ease of dissemination to other sites.

Results

Across the 5 groups, 31 veterans enrolled as participants and completed the initial intake measures, with an average of 6 participants per group (range 4-9). The majority (80%) attended at least 5 of the 6 classes. The mean

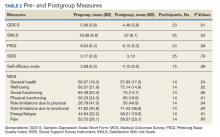

At the start of the class, the mean (SD) reports of participants were mild depressive symptoms 5.96 (3.8) on the GDS scale, moderate levels of self-efficacy 3.69 (0.5) on the self-efficacy scale, and moderate levels of satisfaction with life 18.08 (6.8) on the SWLS scale (Table 2). Data from 25 of 31 veterans who completed both pregroup and postgroup surveys were analyzed and paired samples t tests without corrections indicated a reduction in depressive symptoms (P = .01), improved self-efficacy (P = .08), and improved satisfaction with life (P = .03). There were no significant differences in self-reported sleep quality or perceived social support from pregroup to postgroup evaluations. Because the sample size was smaller for the MOS-36, which was not used until group 3, and the subscales are composed of few items each, we conducted exploratory analyses of the 8 MOS-36 subscales and found that well-being, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical and emotional functioning, and energy/fatigue significantly improved over time (Ps < .04).

Twenty-eight veterans provided written feedback following the final session. Qualitative feedback received at the completion of the group focused on participants’ desire for increased number of classes, longer sessions (eg, 2 participants recommended lengthening the group to 2 hours), and integrating mindfulness-based activities into each class. Participants rated themselves somewhat likely to very likely to recommend this group to other veterans (mean, 2.9 [SD, 0.4]).

Discussion

The ability and need to promote brain health with age is an emerging priority as our aging population grows. A growing body of evidence supports the role of health behaviors in healthy brain aging. Education and skills training in a group setting provides a supportive, cost-effective approach for increasing overall health in aging adults. Yet older adults are statistically less likely to engage in these behaviors on a regular basis. The current investigation provides preliminary support for a model of care that uses a comprehensive, experiential psychoeducational approach to facilitate behavior change in older adults. Our aim was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable to our older veterans and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Participants indicated that they enjoyed the group, learned new skills (per participant feedback and facilitator observation), and experienced improvements in mood, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction. Given the participants’ positive response to the group and its content, as well as continued referrals by HCPs to this group and low difficulty with ongoing recruitment, this program was deemed both feasible and acceptable in our veteran health care setting. Questions remain about the extent to which participants modified their health behaviors given that we did not collect objective measurements of behaviors (eg, time spent exercising), the duration of behavior change (ie, how long during and after the group were behaviors maintained), and the role of premorbid or concurrent characteristics that may moderate the effect of the intervention on health-related outcomes (eg, sleep quality, perceived social support, overall functioning, concurrent interventions, medications).

Strengths and Limitations

This study had a limited sample size and no control group. However, evidence of significant improvements in depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction in the development groups without a control group is encouraging. This is particularly noteworthy given that older veterans as a group have higher rates of frailty and mortality than do other similarly aged counterparts.17An additional weakness is the absence of a brief cognitive assessment or other formal assessment as part of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. However, this program development project provides data from a realistic condition (recruited broadly and with few exclusions, offered in similar format as other VA classes), thus adding strength to the interpretation and possibly the generalizability of these findings.

Conclusions

Future directions include disseminating HAP-B materials and procedures across a variety of sites, both VA and non-VA. In line with this goal, we hope to increase sample size and sample diversity while optimizing protocol integrity during the exportation phase. With a greater sample size and power, we aim to examine the role of self-efficacy and other premorbid factors (eg, cognitive functioning at baseline) as mediators for observed changes in pre-/postmeasures and outcomes. We also hope to incorporate objective measures of behavior change, such as fitness trackers, heart rate/pulse monitors, and actigraphy for monitoring sleep. Finally, we are interested in conducting follow-up with past and future participants to detect changes that may occur with learning new skills following the completion of the group (eg, changes in sleep behavior that take time to take effect) and the extent to which participants continue to use the health behavior skills and strategies to maintain or enhance progress in behavioral goals. Finally, although this intervention was initially designed for use with older veterans receiving health care through the VA, we believe the concepts and work products described here can be used with older adults across a wide range of health care settings. Providers interested in trialing HAP-B at their local site are encouraged to contact the authors.

1. Jacobsen LA, Kent M, Lee M, Mather M. America’s aging population. Popul Bull. 2011;66(1):1-20.

2. Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):85-592. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.5.585

3. Kelly ME, Loughrey D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. The impact of exercise on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:12-31. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.05.002

4. Middleton LE, Manini TM, Simonsick EM, et al. Activity energy expenditure and incident cognitive impairment in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1251-1257. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.277

5. World Health Organization. Interventions on diet and physical activity: what works. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/whatworks/en/. Published 2009. Accessed June 19, 2020.

6. Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychol. 2001;20(4):243-255. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243

7. La Rue A. Healthy brain aging: role of cognitive reserve, cognitive stimulation and cognitive exercises. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(1):99-111. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2009.11.003

8. Salthouse TA, Berish DE, Miles JD. The role of cognitive stimulation on the relations between age and cognitive functioning. Psychol Aging. 2002;17(4):548-557. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.548

9. Wrosch C, Schulz R, Heckhausen J. Health stresses and depressive symptomatology in the elderly: the importance of health engagement control strategies. Health Psychol. 2002;21(4):340-348. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.340

10. Pronk NP, Anderson LH, Crain AL, et al. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors: prevalence, clustering, and predictors among adolescent, adult, and senior health plan members. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(suppl 2):25-33. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.022

11. Gross AL, Parisi JM, Spira AP, et al. Memory training interventions for older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(6):722-734. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.667783

12. Miller KJ, Siddarth P, Gaines JM, et al. The memory fitness program: cognitive effects of a healthy aging intervention. Am J Geriat Psychiatry. 2012;20(6):514-523. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e318227f821

13. Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(3):126-135. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826

14. Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262-1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5

15. US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics.Veteran population. 2020. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Updated May 21, 2020 . Accessed June 17, 2020.

16. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown K, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique healthcare needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. RAND Health Q. 2016;5(4):13.

17. Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho Y, et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. Veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly232

18. Doran GT. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manag Rev. 1981;70(11):35-36.

19. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901-13

20. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1-2):165-173. doi:10.1300/J018v05n01_09

21. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705-714. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b

22. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193-213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

23. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483.

24. Huckans M, Pavawalla S, Demadura T, et al. A pilot study examining effects of group-based cognitive strategy training treatment on self-reported cognitive problems, psychiatric symptoms, functioning, and compensatory strategy use in OIF/OEF combat veterans with persistent mild cognitive disorder and history of traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(1):43-60. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.02.0019

25. Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):32-42. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.018

With a rapidly growing older adult population, increased attention has been given to cognitive changes that occur with age, with a focus on optimizing the cognitive health of aging individuals.1 Given the absence of pharmaceutical treatments to prevent cognitive decline, there is an increased need for health care systems to offer alternative or behavioral interventions that can mitigate the effects of cognitive decline in aging.

Notably, many individuals are able to maintain or even improve cognitive functioning throughout their lifespan, with some research implicating health behaviors as an important factor for promoting brain health with age. Specifically, sleep, exercise, eating habits, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation have been linked to improved cognitive functioning.2-8 In addition to the potential benefits for brain health, there is evidence that greater investment in attaining health goals is associated with subjective reports of higher well-being, fewer mental health symptoms, lower physical health stresses, decreased caregiver burden, and increased functional independence linked with longer independent living.9 The latter has a substantial financial impact, such that the positive consequence of increased independence is likely staving off the need for admission to assisted living and adult family homes, which can be costly.

Despite the role of health behaviors in brain aging and overall health and functioning, research indicates that only a small number of older adults (12.8%) follow recommended guidelines for healthy lifestyle factors.10 Education has been identified as one factor associated with the likelihood of engaging in positive health behaviors, prompting the delivery of health-education interventions. Most psychoeducational interventions have traditionally focused on one aspect of behavior change at a time (eg, sleep); however, Gross and colleaguesconducted a meta-analysis of cognitive interventions and in addition to the overall positive benefits (effect size 0.38), they also found suggestive evidence that interventions that combined multiple training strategies were associated with larger training gains (P = .04) after adjusting for multiple comparisons.11 For example, Miller and colleagues found a significant improvement on both subjective and objective measures of memory following a multicomponent approach that combined training in memory skills, stress reduction, nutrition, and physical activity.12

In addition to the potential positive impacts of health behaviors on brain health, findings suggest that targeted emphasis on health behavior change may have the potential to stave off mild cognitiveimpairment (MCI) or dementia even if for a short time. Given the increasing prevalence rates of MCI with age (6.7% in adults aged 60-64 years, reaching 25.2% in adults aged 80-84 years13) and dementia (prevalence of MCI converting to dementia is 18-40%14), as well as the corresponding emotional, financial, and family-oriented consequences (eg, impact on the well-being of family caregivers), the need for behavioral interventions that seek to optimize brain health is becoming increasingly apparent.

More than 9 million veterans are now aged ≥ 65 years.15 In addition to representing nearly half of all veterans and a sizable portion of aging adults in the US, older veterans are at increased risk of frailty, mortality, and high rates of chronic medical/mental health conditions that can lead to accelerated cognitive aging.6-17 Together, these conditions highlight the importance of developing comprehensive psychoeducational and behavioral interventions in this population. To address this need, we developed a novel psychoeducation and behavior change group called the Healthy Aging Project-Brain (HAP-B, pronounced “happy”). The HAP-B intervention was designed to promote healthy brain aging by using empirically supported health behavior change strategies, including education, personalized goal setting, and community support. The primary aim of this project was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable (eg, could be implemented in our setting, was appropriate for a veteran population) and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Methods

We recruited veterans aged ≥ 50 years through primary care clinics and self-referrals via flyers in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS), Seattle Division hospital. We targeted the “worried well” and welcomed veterans with MCI and mental health diagnoses. Notably, if there were significant mental health and/or substance use concerns, we encouraged veterans to seek focused care and stabilization prior to or concurrent with group participation. Exclusion criteria included presence of suicidality/homicidality, untreated or unstable substance use disorder, or a diagnosis of dementia. Exclusion criteria were assessed by the referring health care providers (HCPs), when appropriate, and through a health record review. Group facilitators used their clinical judgment to monitor participants if they began experiencing more severe cognitive impairment or acute mental health concerns. Although we did not encounter any of these instances, facilitators were prepared to discuss any concerns with the veteran and their referring HCP. Participants sampled were from 1 of 5 groups offered between January 2018 and March 2019. A waiver from the institutional review board was obtained after meeting criteria for quality improvement/quality assurance (QI/QA) for this study.

Procedures

At the initial stages of development, our team conducted a needs assessment to identify health-related areas where HCPs felt veterans would benefit from additional education and support. The needs assessment was conducted across primary care, geriatric extended care, and the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC) at VAPSHCS. Combining the needs assessment results with the available research base, we identified sleep, physical activity, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation as areas for focus. Notably, although nutrition has been identified as an important factor in cognitive aging, a diet and nutrition class was already available to older veterans at the Seattle VA; hence, we chose to limit overlap by not covering this topic in our group.

The group was offered on a quarterly basis as six 90-minute psychoeducational classes to allow time for didactics, discussion, and practice without overloading participants with information. Each group consisted of 4 to 9 veterans led by 2 cofacilitators. Group structure allowed for feedback and ideas from group members as well as accountability for engaging in behavior change. Cognitive functioning was not formally evaluated. Attendees were asked but not required to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. In addition at the completion of each group, feedback was collected from veterans and used to modify group content (Figure).

Two pilot groups were implemented in early and mid-2018 with iterative changes after each group. Then we revised the assessment battery and implemented the current version (v1.0), which was first offered in the fall of 2018 and was used with the final 3 groups. Noteworthy changes included weekly check-ins to assess use of health behavior logs and progress toward individual goals, additional pre-and postgroup measures, and in vivo skills practice relevant to the topic being discussed that day.

Each session began with a check-in, which included a review of daily logs and SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant/realistic, and timebound) goals from the previous week.18 This allowed for praise/reinforcement of health behaviors as well as discussion of potential barriers. Second, an overview of research focusing on the relationship between aging, brain health, and the topic of the day was presented. As an example, in the discussion of social engagement, research was presented about the link between social isolation and cognitive decline; the indirect benefits of social support (eg, social support is linked to improved physical and mental health, which, in turn, is associated with less cognitive decline); and the direct benefits of social support (eg, high levels of emotional support are associated with better cognitive function) (Table 1).6

Next, facilitators reviewed skills and strategies to improve functioning in the topic of discussion. During the social engagement group, for example, facilitators discussed tips to improve social skills (eg, asking open-ended questions) and how to build social support into a daily routine (eg, scheduling weekly phone calls with family and friends). Following this discussion of skills, an activity was practiced, reinforcing learned material. During the social engagement group, veterans were invited to use small talk strategies with fellow group members. Finally, group sessions ended with each participant identifying a SMART goal for the coming week and troubleshooting potential barriers to success. SMART goals were kept broad, so veterans could choose a goal related to the topic discussed at the group that day (eg, scheduling a phone call with a friend twice in the coming week during the social engagement-focused group) or choose any other goal to focus on (eg, a sleep-related goal). Similarly, goals could change week to week, or could remain the same throughout the 6-week classes.

Measures

The questionnaires used for QI/QA analyses included the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-S); Social Support Survey Instrument (SSSI); Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); Medical Outcomes Survey-Short Form (MOS-36 SF); and a self-efficacy scale (adapted from Huckans and colleagues for traumatic brain injury).19-24 Written feedback was collected at the end of the last group to assess perception of progress, self-perceived behavior change, what was helpful or unhelpful, and how likely the participants were to recommend the group to other veterans (0 to 3, very unlikely to very likely).

To promote consistency with other health and behavior change interventions at the VA, HAP-B used resources from the Whole Health model SMART goals. Research supports the use of self-monitoring techniques like SMART goals for behavior change.25

To facilitate skills practice and self-monitoring between classes, veterans were asked to complete 2 homework assignments. First, at the end of each group, each veteran identified a specific SMART goal to focus on and track in the coming week. Goals were unique to each veteran and allowed to change from week to week. Group discussion around SMART goals involved plans for how to address potential barriers; progress toward goals was discussed at the beginning of the following group. Second, veterans were asked to complete a worksheet used to track progress toward the weekly SMART goal and the specific health behaviors related to the 4 domains targeted by HAP-B. For example, when tracking sleep behaviors, veterans noted bedtime, waketime, number of times they woke up during the night, and length of daytime naps if applicable. Tracking logs were provided at the end of each class for personal purposes only. We asked veterans to rate themselves each week on whether they used the tracking sheet to monitor health behaviors; and how successful they were at accomplishing their previously identified SMART goal. We recorded responses on a 0 to 2 scale (0, not good; 1, fair; 2, good). This rating system was developed and implemented in later groups to promote self-monitoring, accountability, and discussion of potential barriers. However, due to the small sample that completed these ratings and the absence of objective corroborating data, these ratings were not included in the current analyses.

Every participant received a manual in binder format, which provided the didactic information for each group session, skills and strategies discussed in each session, and relevant resources in both the VA and community. For example, social engagement resources included information about volunteer opportunities, VA groups that focus on developing interpersonal skills, and recommendations from past group members on social events (eg, dance lessons at a senior center). We also developed a facilitator version of the manual in which we added comments and guidance on topics for discussion. Materials were developed with the goal of optimizing the ease of dissemination to other sites.

Results

Across the 5 groups, 31 veterans enrolled as participants and completed the initial intake measures, with an average of 6 participants per group (range 4-9). The majority (80%) attended at least 5 of the 6 classes. The mean

At the start of the class, the mean (SD) reports of participants were mild depressive symptoms 5.96 (3.8) on the GDS scale, moderate levels of self-efficacy 3.69 (0.5) on the self-efficacy scale, and moderate levels of satisfaction with life 18.08 (6.8) on the SWLS scale (Table 2). Data from 25 of 31 veterans who completed both pregroup and postgroup surveys were analyzed and paired samples t tests without corrections indicated a reduction in depressive symptoms (P = .01), improved self-efficacy (P = .08), and improved satisfaction with life (P = .03). There were no significant differences in self-reported sleep quality or perceived social support from pregroup to postgroup evaluations. Because the sample size was smaller for the MOS-36, which was not used until group 3, and the subscales are composed of few items each, we conducted exploratory analyses of the 8 MOS-36 subscales and found that well-being, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical and emotional functioning, and energy/fatigue significantly improved over time (Ps < .04).

Twenty-eight veterans provided written feedback following the final session. Qualitative feedback received at the completion of the group focused on participants’ desire for increased number of classes, longer sessions (eg, 2 participants recommended lengthening the group to 2 hours), and integrating mindfulness-based activities into each class. Participants rated themselves somewhat likely to very likely to recommend this group to other veterans (mean, 2.9 [SD, 0.4]).

Discussion

The ability and need to promote brain health with age is an emerging priority as our aging population grows. A growing body of evidence supports the role of health behaviors in healthy brain aging. Education and skills training in a group setting provides a supportive, cost-effective approach for increasing overall health in aging adults. Yet older adults are statistically less likely to engage in these behaviors on a regular basis. The current investigation provides preliminary support for a model of care that uses a comprehensive, experiential psychoeducational approach to facilitate behavior change in older adults. Our aim was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable to our older veterans and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Participants indicated that they enjoyed the group, learned new skills (per participant feedback and facilitator observation), and experienced improvements in mood, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction. Given the participants’ positive response to the group and its content, as well as continued referrals by HCPs to this group and low difficulty with ongoing recruitment, this program was deemed both feasible and acceptable in our veteran health care setting. Questions remain about the extent to which participants modified their health behaviors given that we did not collect objective measurements of behaviors (eg, time spent exercising), the duration of behavior change (ie, how long during and after the group were behaviors maintained), and the role of premorbid or concurrent characteristics that may moderate the effect of the intervention on health-related outcomes (eg, sleep quality, perceived social support, overall functioning, concurrent interventions, medications).

Strengths and Limitations

This study had a limited sample size and no control group. However, evidence of significant improvements in depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction in the development groups without a control group is encouraging. This is particularly noteworthy given that older veterans as a group have higher rates of frailty and mortality than do other similarly aged counterparts.17An additional weakness is the absence of a brief cognitive assessment or other formal assessment as part of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. However, this program development project provides data from a realistic condition (recruited broadly and with few exclusions, offered in similar format as other VA classes), thus adding strength to the interpretation and possibly the generalizability of these findings.

Conclusions

Future directions include disseminating HAP-B materials and procedures across a variety of sites, both VA and non-VA. In line with this goal, we hope to increase sample size and sample diversity while optimizing protocol integrity during the exportation phase. With a greater sample size and power, we aim to examine the role of self-efficacy and other premorbid factors (eg, cognitive functioning at baseline) as mediators for observed changes in pre-/postmeasures and outcomes. We also hope to incorporate objective measures of behavior change, such as fitness trackers, heart rate/pulse monitors, and actigraphy for monitoring sleep. Finally, we are interested in conducting follow-up with past and future participants to detect changes that may occur with learning new skills following the completion of the group (eg, changes in sleep behavior that take time to take effect) and the extent to which participants continue to use the health behavior skills and strategies to maintain or enhance progress in behavioral goals. Finally, although this intervention was initially designed for use with older veterans receiving health care through the VA, we believe the concepts and work products described here can be used with older adults across a wide range of health care settings. Providers interested in trialing HAP-B at their local site are encouraged to contact the authors.

With a rapidly growing older adult population, increased attention has been given to cognitive changes that occur with age, with a focus on optimizing the cognitive health of aging individuals.1 Given the absence of pharmaceutical treatments to prevent cognitive decline, there is an increased need for health care systems to offer alternative or behavioral interventions that can mitigate the effects of cognitive decline in aging.

Notably, many individuals are able to maintain or even improve cognitive functioning throughout their lifespan, with some research implicating health behaviors as an important factor for promoting brain health with age. Specifically, sleep, exercise, eating habits, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation have been linked to improved cognitive functioning.2-8 In addition to the potential benefits for brain health, there is evidence that greater investment in attaining health goals is associated with subjective reports of higher well-being, fewer mental health symptoms, lower physical health stresses, decreased caregiver burden, and increased functional independence linked with longer independent living.9 The latter has a substantial financial impact, such that the positive consequence of increased independence is likely staving off the need for admission to assisted living and adult family homes, which can be costly.

Despite the role of health behaviors in brain aging and overall health and functioning, research indicates that only a small number of older adults (12.8%) follow recommended guidelines for healthy lifestyle factors.10 Education has been identified as one factor associated with the likelihood of engaging in positive health behaviors, prompting the delivery of health-education interventions. Most psychoeducational interventions have traditionally focused on one aspect of behavior change at a time (eg, sleep); however, Gross and colleaguesconducted a meta-analysis of cognitive interventions and in addition to the overall positive benefits (effect size 0.38), they also found suggestive evidence that interventions that combined multiple training strategies were associated with larger training gains (P = .04) after adjusting for multiple comparisons.11 For example, Miller and colleagues found a significant improvement on both subjective and objective measures of memory following a multicomponent approach that combined training in memory skills, stress reduction, nutrition, and physical activity.12

In addition to the potential positive impacts of health behaviors on brain health, findings suggest that targeted emphasis on health behavior change may have the potential to stave off mild cognitiveimpairment (MCI) or dementia even if for a short time. Given the increasing prevalence rates of MCI with age (6.7% in adults aged 60-64 years, reaching 25.2% in adults aged 80-84 years13) and dementia (prevalence of MCI converting to dementia is 18-40%14), as well as the corresponding emotional, financial, and family-oriented consequences (eg, impact on the well-being of family caregivers), the need for behavioral interventions that seek to optimize brain health is becoming increasingly apparent.

More than 9 million veterans are now aged ≥ 65 years.15 In addition to representing nearly half of all veterans and a sizable portion of aging adults in the US, older veterans are at increased risk of frailty, mortality, and high rates of chronic medical/mental health conditions that can lead to accelerated cognitive aging.6-17 Together, these conditions highlight the importance of developing comprehensive psychoeducational and behavioral interventions in this population. To address this need, we developed a novel psychoeducation and behavior change group called the Healthy Aging Project-Brain (HAP-B, pronounced “happy”). The HAP-B intervention was designed to promote healthy brain aging by using empirically supported health behavior change strategies, including education, personalized goal setting, and community support. The primary aim of this project was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable (eg, could be implemented in our setting, was appropriate for a veteran population) and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Methods

We recruited veterans aged ≥ 50 years through primary care clinics and self-referrals via flyers in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS), Seattle Division hospital. We targeted the “worried well” and welcomed veterans with MCI and mental health diagnoses. Notably, if there were significant mental health and/or substance use concerns, we encouraged veterans to seek focused care and stabilization prior to or concurrent with group participation. Exclusion criteria included presence of suicidality/homicidality, untreated or unstable substance use disorder, or a diagnosis of dementia. Exclusion criteria were assessed by the referring health care providers (HCPs), when appropriate, and through a health record review. Group facilitators used their clinical judgment to monitor participants if they began experiencing more severe cognitive impairment or acute mental health concerns. Although we did not encounter any of these instances, facilitators were prepared to discuss any concerns with the veteran and their referring HCP. Participants sampled were from 1 of 5 groups offered between January 2018 and March 2019. A waiver from the institutional review board was obtained after meeting criteria for quality improvement/quality assurance (QI/QA) for this study.

Procedures

At the initial stages of development, our team conducted a needs assessment to identify health-related areas where HCPs felt veterans would benefit from additional education and support. The needs assessment was conducted across primary care, geriatric extended care, and the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC) at VAPSHCS. Combining the needs assessment results with the available research base, we identified sleep, physical activity, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation as areas for focus. Notably, although nutrition has been identified as an important factor in cognitive aging, a diet and nutrition class was already available to older veterans at the Seattle VA; hence, we chose to limit overlap by not covering this topic in our group.

The group was offered on a quarterly basis as six 90-minute psychoeducational classes to allow time for didactics, discussion, and practice without overloading participants with information. Each group consisted of 4 to 9 veterans led by 2 cofacilitators. Group structure allowed for feedback and ideas from group members as well as accountability for engaging in behavior change. Cognitive functioning was not formally evaluated. Attendees were asked but not required to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. In addition at the completion of each group, feedback was collected from veterans and used to modify group content (Figure).

Two pilot groups were implemented in early and mid-2018 with iterative changes after each group. Then we revised the assessment battery and implemented the current version (v1.0), which was first offered in the fall of 2018 and was used with the final 3 groups. Noteworthy changes included weekly check-ins to assess use of health behavior logs and progress toward individual goals, additional pre-and postgroup measures, and in vivo skills practice relevant to the topic being discussed that day.

Each session began with a check-in, which included a review of daily logs and SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant/realistic, and timebound) goals from the previous week.18 This allowed for praise/reinforcement of health behaviors as well as discussion of potential barriers. Second, an overview of research focusing on the relationship between aging, brain health, and the topic of the day was presented. As an example, in the discussion of social engagement, research was presented about the link between social isolation and cognitive decline; the indirect benefits of social support (eg, social support is linked to improved physical and mental health, which, in turn, is associated with less cognitive decline); and the direct benefits of social support (eg, high levels of emotional support are associated with better cognitive function) (Table 1).6

Next, facilitators reviewed skills and strategies to improve functioning in the topic of discussion. During the social engagement group, for example, facilitators discussed tips to improve social skills (eg, asking open-ended questions) and how to build social support into a daily routine (eg, scheduling weekly phone calls with family and friends). Following this discussion of skills, an activity was practiced, reinforcing learned material. During the social engagement group, veterans were invited to use small talk strategies with fellow group members. Finally, group sessions ended with each participant identifying a SMART goal for the coming week and troubleshooting potential barriers to success. SMART goals were kept broad, so veterans could choose a goal related to the topic discussed at the group that day (eg, scheduling a phone call with a friend twice in the coming week during the social engagement-focused group) or choose any other goal to focus on (eg, a sleep-related goal). Similarly, goals could change week to week, or could remain the same throughout the 6-week classes.

Measures

The questionnaires used for QI/QA analyses included the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-S); Social Support Survey Instrument (SSSI); Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); Medical Outcomes Survey-Short Form (MOS-36 SF); and a self-efficacy scale (adapted from Huckans and colleagues for traumatic brain injury).19-24 Written feedback was collected at the end of the last group to assess perception of progress, self-perceived behavior change, what was helpful or unhelpful, and how likely the participants were to recommend the group to other veterans (0 to 3, very unlikely to very likely).

To promote consistency with other health and behavior change interventions at the VA, HAP-B used resources from the Whole Health model SMART goals. Research supports the use of self-monitoring techniques like SMART goals for behavior change.25

To facilitate skills practice and self-monitoring between classes, veterans were asked to complete 2 homework assignments. First, at the end of each group, each veteran identified a specific SMART goal to focus on and track in the coming week. Goals were unique to each veteran and allowed to change from week to week. Group discussion around SMART goals involved plans for how to address potential barriers; progress toward goals was discussed at the beginning of the following group. Second, veterans were asked to complete a worksheet used to track progress toward the weekly SMART goal and the specific health behaviors related to the 4 domains targeted by HAP-B. For example, when tracking sleep behaviors, veterans noted bedtime, waketime, number of times they woke up during the night, and length of daytime naps if applicable. Tracking logs were provided at the end of each class for personal purposes only. We asked veterans to rate themselves each week on whether they used the tracking sheet to monitor health behaviors; and how successful they were at accomplishing their previously identified SMART goal. We recorded responses on a 0 to 2 scale (0, not good; 1, fair; 2, good). This rating system was developed and implemented in later groups to promote self-monitoring, accountability, and discussion of potential barriers. However, due to the small sample that completed these ratings and the absence of objective corroborating data, these ratings were not included in the current analyses.

Every participant received a manual in binder format, which provided the didactic information for each group session, skills and strategies discussed in each session, and relevant resources in both the VA and community. For example, social engagement resources included information about volunteer opportunities, VA groups that focus on developing interpersonal skills, and recommendations from past group members on social events (eg, dance lessons at a senior center). We also developed a facilitator version of the manual in which we added comments and guidance on topics for discussion. Materials were developed with the goal of optimizing the ease of dissemination to other sites.

Results

Across the 5 groups, 31 veterans enrolled as participants and completed the initial intake measures, with an average of 6 participants per group (range 4-9). The majority (80%) attended at least 5 of the 6 classes. The mean

At the start of the class, the mean (SD) reports of participants were mild depressive symptoms 5.96 (3.8) on the GDS scale, moderate levels of self-efficacy 3.69 (0.5) on the self-efficacy scale, and moderate levels of satisfaction with life 18.08 (6.8) on the SWLS scale (Table 2). Data from 25 of 31 veterans who completed both pregroup and postgroup surveys were analyzed and paired samples t tests without corrections indicated a reduction in depressive symptoms (P = .01), improved self-efficacy (P = .08), and improved satisfaction with life (P = .03). There were no significant differences in self-reported sleep quality or perceived social support from pregroup to postgroup evaluations. Because the sample size was smaller for the MOS-36, which was not used until group 3, and the subscales are composed of few items each, we conducted exploratory analyses of the 8 MOS-36 subscales and found that well-being, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical and emotional functioning, and energy/fatigue significantly improved over time (Ps < .04).

Twenty-eight veterans provided written feedback following the final session. Qualitative feedback received at the completion of the group focused on participants’ desire for increased number of classes, longer sessions (eg, 2 participants recommended lengthening the group to 2 hours), and integrating mindfulness-based activities into each class. Participants rated themselves somewhat likely to very likely to recommend this group to other veterans (mean, 2.9 [SD, 0.4]).

Discussion

The ability and need to promote brain health with age is an emerging priority as our aging population grows. A growing body of evidence supports the role of health behaviors in healthy brain aging. Education and skills training in a group setting provides a supportive, cost-effective approach for increasing overall health in aging adults. Yet older adults are statistically less likely to engage in these behaviors on a regular basis. The current investigation provides preliminary support for a model of care that uses a comprehensive, experiential psychoeducational approach to facilitate behavior change in older adults. Our aim was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable to our older veterans and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Participants indicated that they enjoyed the group, learned new skills (per participant feedback and facilitator observation), and experienced improvements in mood, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction. Given the participants’ positive response to the group and its content, as well as continued referrals by HCPs to this group and low difficulty with ongoing recruitment, this program was deemed both feasible and acceptable in our veteran health care setting. Questions remain about the extent to which participants modified their health behaviors given that we did not collect objective measurements of behaviors (eg, time spent exercising), the duration of behavior change (ie, how long during and after the group were behaviors maintained), and the role of premorbid or concurrent characteristics that may moderate the effect of the intervention on health-related outcomes (eg, sleep quality, perceived social support, overall functioning, concurrent interventions, medications).

Strengths and Limitations

This study had a limited sample size and no control group. However, evidence of significant improvements in depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction in the development groups without a control group is encouraging. This is particularly noteworthy given that older veterans as a group have higher rates of frailty and mortality than do other similarly aged counterparts.17An additional weakness is the absence of a brief cognitive assessment or other formal assessment as part of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. However, this program development project provides data from a realistic condition (recruited broadly and with few exclusions, offered in similar format as other VA classes), thus adding strength to the interpretation and possibly the generalizability of these findings.

Conclusions

Future directions include disseminating HAP-B materials and procedures across a variety of sites, both VA and non-VA. In line with this goal, we hope to increase sample size and sample diversity while optimizing protocol integrity during the exportation phase. With a greater sample size and power, we aim to examine the role of self-efficacy and other premorbid factors (eg, cognitive functioning at baseline) as mediators for observed changes in pre-/postmeasures and outcomes. We also hope to incorporate objective measures of behavior change, such as fitness trackers, heart rate/pulse monitors, and actigraphy for monitoring sleep. Finally, we are interested in conducting follow-up with past and future participants to detect changes that may occur with learning new skills following the completion of the group (eg, changes in sleep behavior that take time to take effect) and the extent to which participants continue to use the health behavior skills and strategies to maintain or enhance progress in behavioral goals. Finally, although this intervention was initially designed for use with older veterans receiving health care through the VA, we believe the concepts and work products described here can be used with older adults across a wide range of health care settings. Providers interested in trialing HAP-B at their local site are encouraged to contact the authors.

1. Jacobsen LA, Kent M, Lee M, Mather M. America’s aging population. Popul Bull. 2011;66(1):1-20.

2. Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):85-592. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.5.585

3. Kelly ME, Loughrey D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. The impact of exercise on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:12-31. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.05.002

4. Middleton LE, Manini TM, Simonsick EM, et al. Activity energy expenditure and incident cognitive impairment in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1251-1257. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.277

5. World Health Organization. Interventions on diet and physical activity: what works. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/whatworks/en/. Published 2009. Accessed June 19, 2020.

6. Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychol. 2001;20(4):243-255. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243

7. La Rue A. Healthy brain aging: role of cognitive reserve, cognitive stimulation and cognitive exercises. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(1):99-111. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2009.11.003

8. Salthouse TA, Berish DE, Miles JD. The role of cognitive stimulation on the relations between age and cognitive functioning. Psychol Aging. 2002;17(4):548-557. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.548

9. Wrosch C, Schulz R, Heckhausen J. Health stresses and depressive symptomatology in the elderly: the importance of health engagement control strategies. Health Psychol. 2002;21(4):340-348. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.340

10. Pronk NP, Anderson LH, Crain AL, et al. Meeting recommendations for multiple healthy lifestyle factors: prevalence, clustering, and predictors among adolescent, adult, and senior health plan members. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(suppl 2):25-33. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.022

11. Gross AL, Parisi JM, Spira AP, et al. Memory training interventions for older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(6):722-734. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.667783

12. Miller KJ, Siddarth P, Gaines JM, et al. The memory fitness program: cognitive effects of a healthy aging intervention. Am J Geriat Psychiatry. 2012;20(6):514-523. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e318227f821

13. Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(3):126-135. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826

14. Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262-1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5

15. US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics.Veteran population. 2020. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Updated May 21, 2020 . Accessed June 17, 2020.

16. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown K, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique healthcare needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. RAND Health Q. 2016;5(4):13.

17. Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho Y, et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. Veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly232

18. Doran GT. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manag Rev. 1981;70(11):35-36.

19. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901-13

20. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1-2):165-173. doi:10.1300/J018v05n01_09

21. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705-714. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b

22. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193-213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

23. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483.

24. Huckans M, Pavawalla S, Demadura T, et al. A pilot study examining effects of group-based cognitive strategy training treatment on self-reported cognitive problems, psychiatric symptoms, functioning, and compensatory strategy use in OIF/OEF combat veterans with persistent mild cognitive disorder and history of traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(1):43-60. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.02.0019

25. Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):32-42. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.018

1. Jacobsen LA, Kent M, Lee M, Mather M. America’s aging population. Popul Bull. 2011;66(1):1-20.

2. Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):85-592. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.5.585

3. Kelly ME, Loughrey D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. The impact of exercise on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:12-31. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.05.002

4. Middleton LE, Manini TM, Simonsick EM, et al. Activity energy expenditure and incident cognitive impairment in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1251-1257. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.277

5. World Health Organization. Interventions on diet and physical activity: what works. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/whatworks/en/. Published 2009. Accessed June 19, 2020.