User login

Gut Bacteria’s Influence on Obesity Differs in Men and Women

Gut bacteria predictive of body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and fat mass are different in men and women, and therefore, interventions to prevent obesity may need to be different, as well, new research suggested.

Metagenomic analyses of fecal samples and metabolomic analyses of serum samples from 361 volunteers in Spain showed that an imbalance in specific bacterial strains likely play an important role in the onset and development of obesity, and that there are “considerable differences” between the sexes, said lead study author Paula Aranaz, MD, Centre for Nutrition Research, at the University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain.

“We are still far from knowing the magnitude of the effect that the microbiota [bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa] has on our metabolic health and, therefore, on the greater or lesser risk of suffering from obesity,” Dr. Aranaz told this news organization.

“However,” she said, “what does seem clear is that the microorganisms of our intestine perform a crucial role in the way we metabolize nutrients and, therefore, influence the compounds and molecules that circulate through our body, affecting different organs and tissues, and our general metabolic health.”

The study will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity (ECO) 2024, to be held in Venice, Italy, from May 12 to 15. The abstract is now available online.

Variation in Bacteria Species, Abundance

The researchers examined the fecal metabolome of 361 adult volunteers (median age, 44; 70%, women) from the Spanish Obekit randomized trial, which investigated the relationship between genetic variants and how participants responded to a low-calorie diet.

A total of 65 participants were normal weight, 110 with overweight, and 186 with obesity. They were matched for sex and age and classified according to an obesity (OB) index as LOW or HIGH.

LOW included those with a BMI ≤ 30 kg/m2, fat mass percentage ≤ 25% (women) or ≤ 32% (men), and waist circumference ≤ 88 cm (women) or ≤ 102 cm (men). HIGH included those with a BMI > 30 kg/m2, fat mass > 25% (women) or > 32% (men), and waist circumference > 88 cm (women) or > 102 cm (men).

In men, a greater abundance of Parabacteroides helcogenes and Campylobacter canadensis species was associated with higher BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference.

By contrast, in women, a greater abundance of Prevotella micans, P brevis, and P sacharolitica was predictive of higher BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference.

Untargeted metabolomic analyses revealed variation in the abundance of certain metabolites in participants with a HIGH OB index — notably, higher levels of phospholipids (implicated in the development of metabolic disease and modulators of insulin sensitivity) and sphingolipids, which play a role in the development of diabetes and the emergence of vascular complications.

“We can reduce the risk of metabolic diseases by modulating the gut microbiome through nutritional and lifestyle factors, including dietary patterns, foods, exercise, probiotics, and postbiotics,” Dr. Aranaz said. Which modifications can and should be made “depend on many factors, including the host genetics, endocrine system, sex, and age.”

The researchers currently are working to try to relate the identified metabolites to the bacterial species that could be producing them and to characterize the biological effect that these species and their metabolites exert on the organism, Dr. Aranaz added.

Ultimately, she said, “we would like to [design] a microbiota/metabolomic test that can be used in clinical practice to identify human enterotypes and to personalize the dietary strategies to minimize the health risks related to gut dysbiosis.”

No funding was reported. Dr. Aranaz declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Gut bacteria predictive of body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and fat mass are different in men and women, and therefore, interventions to prevent obesity may need to be different, as well, new research suggested.

Metagenomic analyses of fecal samples and metabolomic analyses of serum samples from 361 volunteers in Spain showed that an imbalance in specific bacterial strains likely play an important role in the onset and development of obesity, and that there are “considerable differences” between the sexes, said lead study author Paula Aranaz, MD, Centre for Nutrition Research, at the University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain.

“We are still far from knowing the magnitude of the effect that the microbiota [bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa] has on our metabolic health and, therefore, on the greater or lesser risk of suffering from obesity,” Dr. Aranaz told this news organization.

“However,” she said, “what does seem clear is that the microorganisms of our intestine perform a crucial role in the way we metabolize nutrients and, therefore, influence the compounds and molecules that circulate through our body, affecting different organs and tissues, and our general metabolic health.”

The study will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity (ECO) 2024, to be held in Venice, Italy, from May 12 to 15. The abstract is now available online.

Variation in Bacteria Species, Abundance

The researchers examined the fecal metabolome of 361 adult volunteers (median age, 44; 70%, women) from the Spanish Obekit randomized trial, which investigated the relationship between genetic variants and how participants responded to a low-calorie diet.

A total of 65 participants were normal weight, 110 with overweight, and 186 with obesity. They were matched for sex and age and classified according to an obesity (OB) index as LOW or HIGH.

LOW included those with a BMI ≤ 30 kg/m2, fat mass percentage ≤ 25% (women) or ≤ 32% (men), and waist circumference ≤ 88 cm (women) or ≤ 102 cm (men). HIGH included those with a BMI > 30 kg/m2, fat mass > 25% (women) or > 32% (men), and waist circumference > 88 cm (women) or > 102 cm (men).

In men, a greater abundance of Parabacteroides helcogenes and Campylobacter canadensis species was associated with higher BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference.

By contrast, in women, a greater abundance of Prevotella micans, P brevis, and P sacharolitica was predictive of higher BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference.

Untargeted metabolomic analyses revealed variation in the abundance of certain metabolites in participants with a HIGH OB index — notably, higher levels of phospholipids (implicated in the development of metabolic disease and modulators of insulin sensitivity) and sphingolipids, which play a role in the development of diabetes and the emergence of vascular complications.

“We can reduce the risk of metabolic diseases by modulating the gut microbiome through nutritional and lifestyle factors, including dietary patterns, foods, exercise, probiotics, and postbiotics,” Dr. Aranaz said. Which modifications can and should be made “depend on many factors, including the host genetics, endocrine system, sex, and age.”

The researchers currently are working to try to relate the identified metabolites to the bacterial species that could be producing them and to characterize the biological effect that these species and their metabolites exert on the organism, Dr. Aranaz added.

Ultimately, she said, “we would like to [design] a microbiota/metabolomic test that can be used in clinical practice to identify human enterotypes and to personalize the dietary strategies to minimize the health risks related to gut dysbiosis.”

No funding was reported. Dr. Aranaz declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Gut bacteria predictive of body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and fat mass are different in men and women, and therefore, interventions to prevent obesity may need to be different, as well, new research suggested.

Metagenomic analyses of fecal samples and metabolomic analyses of serum samples from 361 volunteers in Spain showed that an imbalance in specific bacterial strains likely play an important role in the onset and development of obesity, and that there are “considerable differences” between the sexes, said lead study author Paula Aranaz, MD, Centre for Nutrition Research, at the University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain.

“We are still far from knowing the magnitude of the effect that the microbiota [bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa] has on our metabolic health and, therefore, on the greater or lesser risk of suffering from obesity,” Dr. Aranaz told this news organization.

“However,” she said, “what does seem clear is that the microorganisms of our intestine perform a crucial role in the way we metabolize nutrients and, therefore, influence the compounds and molecules that circulate through our body, affecting different organs and tissues, and our general metabolic health.”

The study will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity (ECO) 2024, to be held in Venice, Italy, from May 12 to 15. The abstract is now available online.

Variation in Bacteria Species, Abundance

The researchers examined the fecal metabolome of 361 adult volunteers (median age, 44; 70%, women) from the Spanish Obekit randomized trial, which investigated the relationship between genetic variants and how participants responded to a low-calorie diet.

A total of 65 participants were normal weight, 110 with overweight, and 186 with obesity. They were matched for sex and age and classified according to an obesity (OB) index as LOW or HIGH.

LOW included those with a BMI ≤ 30 kg/m2, fat mass percentage ≤ 25% (women) or ≤ 32% (men), and waist circumference ≤ 88 cm (women) or ≤ 102 cm (men). HIGH included those with a BMI > 30 kg/m2, fat mass > 25% (women) or > 32% (men), and waist circumference > 88 cm (women) or > 102 cm (men).

In men, a greater abundance of Parabacteroides helcogenes and Campylobacter canadensis species was associated with higher BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference.

By contrast, in women, a greater abundance of Prevotella micans, P brevis, and P sacharolitica was predictive of higher BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference.

Untargeted metabolomic analyses revealed variation in the abundance of certain metabolites in participants with a HIGH OB index — notably, higher levels of phospholipids (implicated in the development of metabolic disease and modulators of insulin sensitivity) and sphingolipids, which play a role in the development of diabetes and the emergence of vascular complications.

“We can reduce the risk of metabolic diseases by modulating the gut microbiome through nutritional and lifestyle factors, including dietary patterns, foods, exercise, probiotics, and postbiotics,” Dr. Aranaz said. Which modifications can and should be made “depend on many factors, including the host genetics, endocrine system, sex, and age.”

The researchers currently are working to try to relate the identified metabolites to the bacterial species that could be producing them and to characterize the biological effect that these species and their metabolites exert on the organism, Dr. Aranaz added.

Ultimately, she said, “we would like to [design] a microbiota/metabolomic test that can be used in clinical practice to identify human enterotypes and to personalize the dietary strategies to minimize the health risks related to gut dysbiosis.”

No funding was reported. Dr. Aranaz declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Do Adults With Obesity Feel Pain More Intensely?

TOPLINE:

Adults with excess weight or obesity tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity than those with a normal weight, highlighting the importance of addressing obesity as part of pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies suggest that obesity may change pain perception and worsen existing painful conditions.

- To examine the association between overweight or obesity and self-perceived pain intensities, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies that included 31,210 adults older than 18 years and from diverse international cohorts.

- The participants were categorized by body mass index (BMI) as being normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obese (≥ 30). A BMI ≥ 25 was considered excess weight.

- Pain intensity was assessed by self-report using the Visual Analog Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Numerical Pain Rating Scale, with the lowest value indicating “no pain” and the highest value representing “pain as bad as it could be.”

- Researchers compared pain intensity between these patient BMI groups: Normal weight vs overweight plus obesity, normal weight vs overweight, normal weight vs obesity, and overweight vs obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with people with normal weight, people with excess weight (overweight or obesity; standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.15; P = .0052) or with obesity (SMD, −0.22; P = .0008) reported higher pain intensities, with a small effect size.

- The comparison of self-report pain in people who had normal weight and overweight did not show any statistically significant difference.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings encourage the treatment of obesity and the control of body mass index (weight loss) as key complementary interventions for pain management,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Miguel M. Garcia, Department of Basic Health Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Unidad Asociada de I+D+i al Instituto de Química Médica CSIC-URJC, Alcorcón, Spain. It was published online in Frontiers in Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis did not include individuals who were underweight, potentially overlooking the associations between physical pain and malnutrition. BMI may misclassify individuals with high muscularity, as it doesn’t accurately reflect adiposity and cannot distinguish between two people with similar BMIs and different body compositions. Furthermore, the study did not consider gender-based differences while evaluating pain outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with excess weight or obesity tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity than those with a normal weight, highlighting the importance of addressing obesity as part of pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies suggest that obesity may change pain perception and worsen existing painful conditions.

- To examine the association between overweight or obesity and self-perceived pain intensities, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies that included 31,210 adults older than 18 years and from diverse international cohorts.

- The participants were categorized by body mass index (BMI) as being normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obese (≥ 30). A BMI ≥ 25 was considered excess weight.

- Pain intensity was assessed by self-report using the Visual Analog Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Numerical Pain Rating Scale, with the lowest value indicating “no pain” and the highest value representing “pain as bad as it could be.”

- Researchers compared pain intensity between these patient BMI groups: Normal weight vs overweight plus obesity, normal weight vs overweight, normal weight vs obesity, and overweight vs obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with people with normal weight, people with excess weight (overweight or obesity; standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.15; P = .0052) or with obesity (SMD, −0.22; P = .0008) reported higher pain intensities, with a small effect size.

- The comparison of self-report pain in people who had normal weight and overweight did not show any statistically significant difference.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings encourage the treatment of obesity and the control of body mass index (weight loss) as key complementary interventions for pain management,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Miguel M. Garcia, Department of Basic Health Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Unidad Asociada de I+D+i al Instituto de Química Médica CSIC-URJC, Alcorcón, Spain. It was published online in Frontiers in Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis did not include individuals who were underweight, potentially overlooking the associations between physical pain and malnutrition. BMI may misclassify individuals with high muscularity, as it doesn’t accurately reflect adiposity and cannot distinguish between two people with similar BMIs and different body compositions. Furthermore, the study did not consider gender-based differences while evaluating pain outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with excess weight or obesity tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity than those with a normal weight, highlighting the importance of addressing obesity as part of pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies suggest that obesity may change pain perception and worsen existing painful conditions.

- To examine the association between overweight or obesity and self-perceived pain intensities, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies that included 31,210 adults older than 18 years and from diverse international cohorts.

- The participants were categorized by body mass index (BMI) as being normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obese (≥ 30). A BMI ≥ 25 was considered excess weight.

- Pain intensity was assessed by self-report using the Visual Analog Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Numerical Pain Rating Scale, with the lowest value indicating “no pain” and the highest value representing “pain as bad as it could be.”

- Researchers compared pain intensity between these patient BMI groups: Normal weight vs overweight plus obesity, normal weight vs overweight, normal weight vs obesity, and overweight vs obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with people with normal weight, people with excess weight (overweight or obesity; standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.15; P = .0052) or with obesity (SMD, −0.22; P = .0008) reported higher pain intensities, with a small effect size.

- The comparison of self-report pain in people who had normal weight and overweight did not show any statistically significant difference.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings encourage the treatment of obesity and the control of body mass index (weight loss) as key complementary interventions for pain management,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Miguel M. Garcia, Department of Basic Health Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Unidad Asociada de I+D+i al Instituto de Química Médica CSIC-URJC, Alcorcón, Spain. It was published online in Frontiers in Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis did not include individuals who were underweight, potentially overlooking the associations between physical pain and malnutrition. BMI may misclassify individuals with high muscularity, as it doesn’t accurately reflect adiposity and cannot distinguish between two people with similar BMIs and different body compositions. Furthermore, the study did not consider gender-based differences while evaluating pain outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

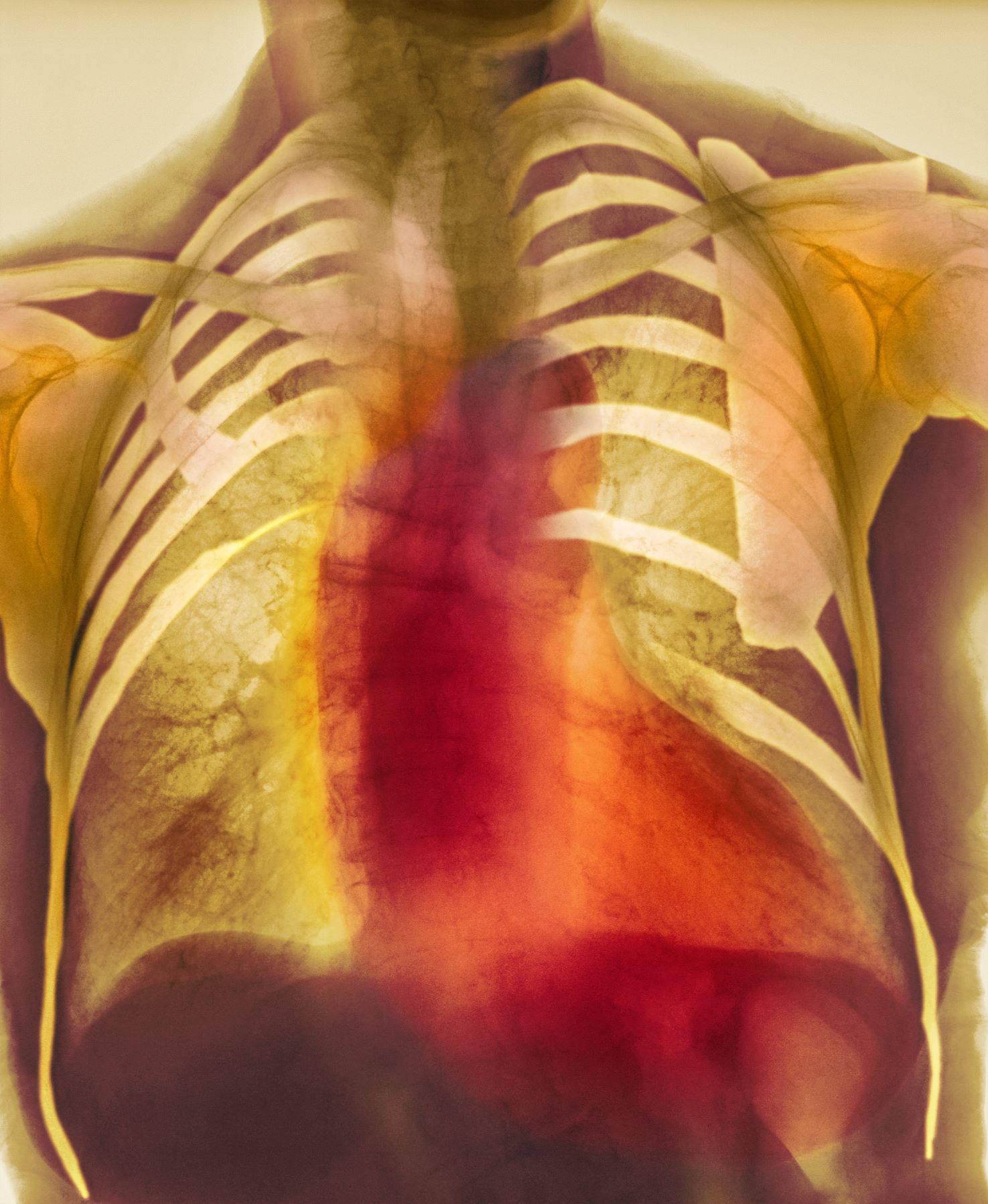

Dyspnea and mild edema

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old patient with obesity presents with dyspnea and mild edema. The patient is 5 ft 9 in, weighs 210 lb (BMI 31), and received an obesity diagnosis 1 year ago with a weight of 220 lb (BMI 32.5) but notes having lived with a BMI ≥ 30 for at least 5 years. Since being diagnosed with obesity, the patient has participated in regular counseling with a clinical nutrition specialist and exercise therapy, reports satisfaction with these, and is happy to have lost 10 lb. The patient presents today for follow-up physical exam and lab workup, with a complaint of increasing dyspnea that has limited participation in exercise therapy over the past 2 months.

On physical exam, the patient appears pale, with shortness of breath and mild edema in the ankles. The heart rhythm is fluttery and the heart rate is elevated at 90 beats/min. Blood pressure is 150/90 mm Hg. Lab results show A1c 6.6% and fasting glucose of 115 mg/dL. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is 101 mg/dL. Thyroid and hematologic findings are within normal parameters. The patient is sent for chest radiography, shown above (colorized).

Higher BMI More CVD Protective in Older Adults With T2D?

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) older than 65 years, a body mass index (BMI) in the moderate overweight category (26-28) appears to offer better protection from cardiovascular death than does a BMI in the “normal” range, new data suggested.

On the other hand, the study findings also suggest that the “normal” range of 23-25 is optimal for middle-aged adults with T2D.

The findings reflect a previously demonstrated phenomenon called the “obesity paradox,” in which older people with overweight may have better outcomes than leaner people due to factors such as bone loss, frailty, and nutritional deficits, study lead author Shaoyong Xu, of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China, told this news organization.

“In this era of population growth and aging, the question arises as to whether obesity or overweight can be beneficial in improving survival rates for older individuals with diabetes. This topic holds significant relevance due to the potential implications it has on weight management strategies for older adults. If overweight does not pose an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, it may suggest that older individuals are not necessarily required to strive for weight loss to achieve so-called normal values.”

Moreover, Dr. Xu added, “inappropriate weight loss and being underweight could potentially elevate the risk of cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and all-cause mortality.”

Thus, he said, “while there are general guidelines recommending a BMI below 25, our findings suggest that personalized BMI targets may be more beneficial, particularly for different age groups and individuals with specific health conditions.”

Asked to comment, Ian J. Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, pointed out that older people who are underweight or in lower weight categories may be more likely to smoke or have undiagnosed cancer, or that “their BMI is not so much reflective of fat mass as of low muscle mass, or sarcopenia, and that is definitely a risk factor for adverse outcomes and risks. ... And those who have slightly higher BMIs may be maintaining muscle mass, even though they’re older, and therefore they have less risk.”

However, Dr. Neeland disagreed with the authors’ conclusions regarding “optimal” BMI. “Just because you have different risk categories based on BMI doesn’t mean that’s ‘optimal’ BMI. The way I would interpret this paper is that there’s an association of mildly overweight with better outcomes in adults who are over 65 with type 2 diabetes. We need to try to understand the mechanisms underlying that observation.”

Dr. Neeland advised that for an older person with T2D who has low muscle mass and frailty, “I wouldn’t recommend necessarily targeted weight loss in that person. But I would potentially recommend weight loss in addition to resistance training, muscle building, and endurance training, and therefore reducing fat mass. The goal would be not so much weight loss but reduction of body fat and maintaining and improving muscle health.”

U-Shaped Relationship Found Between Age, BMI, and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk

The data come from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. A total of 22,874 participants with baseline T2D were included in the current study. Baseline surveys were conducted between 2006 and 2010, and follow-up was a median of 12.52 years. During that time, 891 people died of CVD.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for baseline variables including age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, level of physical exercise, and history of CVDs.

Compared with people with BMI a < 25 in the group who were aged 65 years or younger, those with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 had a 13% higher risk for cardiovascular death. However, among those older than 65 years, a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 was associated with an 18% lower risk.

A U-shaped relationship was found between BMI and the risk for cardiovascular death, with an optimal BMI cutoff of 24.0 in the under-65 group and a 27.0 cutoff in the older group. Ranges of 23.0-25.0 in the under-65 group and 26.0-28 in the older group were associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, there was a linear relationship between both waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio and the risk for cardiovascular death, making those more direct measures of adiposity, Dr. Xu told this news organization.

“For clinicians, our data underscores the importance of considering age when assessing BMI targets for cardiovascular health. Personalized treatment plans that account for age-specific BMI cutoffs and other risk factors may enhance patient outcomes and reduce CVD mortality,” Dr. Xu said.

However, he added, “while these findings suggest an optimal BMI range, it is crucial to acknowledge that these cutoff points may vary based on gender, race, and other factors. Our future studies will validate these findings in different populations and attempt to explain the mechanism by which the optimal nodal values exist in people with diabetes at different ages.”

Dr. Neeland cautioned, “I think more work needs to be done in terms of not just identifying the risk differences but understanding why and how to better risk stratify individuals and do personalized medicine. I think that’s important, but you have to have good data to support the strategies you’re going to use. These data are observational, and they’re a good start, but they wouldn’t directly impact practice at this point.”

The data will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity taking place May 12-15 in Venice, Italy.

The authors declared no competing interests. Study funding came from several sources, including the Young Talents Project of Hubei Provincial Health Commission, China, Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, the Science and Technology Research Key Project of the Education Department of Hubei Province China, and the Sanuo Diabetes Charity Foundation, China, and the Xiangyang Science and Technology Plan Project, China. Dr. Neeland is a speaker and/or consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, and Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) older than 65 years, a body mass index (BMI) in the moderate overweight category (26-28) appears to offer better protection from cardiovascular death than does a BMI in the “normal” range, new data suggested.

On the other hand, the study findings also suggest that the “normal” range of 23-25 is optimal for middle-aged adults with T2D.

The findings reflect a previously demonstrated phenomenon called the “obesity paradox,” in which older people with overweight may have better outcomes than leaner people due to factors such as bone loss, frailty, and nutritional deficits, study lead author Shaoyong Xu, of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China, told this news organization.

“In this era of population growth and aging, the question arises as to whether obesity or overweight can be beneficial in improving survival rates for older individuals with diabetes. This topic holds significant relevance due to the potential implications it has on weight management strategies for older adults. If overweight does not pose an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, it may suggest that older individuals are not necessarily required to strive for weight loss to achieve so-called normal values.”

Moreover, Dr. Xu added, “inappropriate weight loss and being underweight could potentially elevate the risk of cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and all-cause mortality.”

Thus, he said, “while there are general guidelines recommending a BMI below 25, our findings suggest that personalized BMI targets may be more beneficial, particularly for different age groups and individuals with specific health conditions.”

Asked to comment, Ian J. Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, pointed out that older people who are underweight or in lower weight categories may be more likely to smoke or have undiagnosed cancer, or that “their BMI is not so much reflective of fat mass as of low muscle mass, or sarcopenia, and that is definitely a risk factor for adverse outcomes and risks. ... And those who have slightly higher BMIs may be maintaining muscle mass, even though they’re older, and therefore they have less risk.”

However, Dr. Neeland disagreed with the authors’ conclusions regarding “optimal” BMI. “Just because you have different risk categories based on BMI doesn’t mean that’s ‘optimal’ BMI. The way I would interpret this paper is that there’s an association of mildly overweight with better outcomes in adults who are over 65 with type 2 diabetes. We need to try to understand the mechanisms underlying that observation.”

Dr. Neeland advised that for an older person with T2D who has low muscle mass and frailty, “I wouldn’t recommend necessarily targeted weight loss in that person. But I would potentially recommend weight loss in addition to resistance training, muscle building, and endurance training, and therefore reducing fat mass. The goal would be not so much weight loss but reduction of body fat and maintaining and improving muscle health.”

U-Shaped Relationship Found Between Age, BMI, and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk

The data come from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. A total of 22,874 participants with baseline T2D were included in the current study. Baseline surveys were conducted between 2006 and 2010, and follow-up was a median of 12.52 years. During that time, 891 people died of CVD.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for baseline variables including age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, level of physical exercise, and history of CVDs.

Compared with people with BMI a < 25 in the group who were aged 65 years or younger, those with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 had a 13% higher risk for cardiovascular death. However, among those older than 65 years, a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 was associated with an 18% lower risk.

A U-shaped relationship was found between BMI and the risk for cardiovascular death, with an optimal BMI cutoff of 24.0 in the under-65 group and a 27.0 cutoff in the older group. Ranges of 23.0-25.0 in the under-65 group and 26.0-28 in the older group were associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, there was a linear relationship between both waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio and the risk for cardiovascular death, making those more direct measures of adiposity, Dr. Xu told this news organization.

“For clinicians, our data underscores the importance of considering age when assessing BMI targets for cardiovascular health. Personalized treatment plans that account for age-specific BMI cutoffs and other risk factors may enhance patient outcomes and reduce CVD mortality,” Dr. Xu said.

However, he added, “while these findings suggest an optimal BMI range, it is crucial to acknowledge that these cutoff points may vary based on gender, race, and other factors. Our future studies will validate these findings in different populations and attempt to explain the mechanism by which the optimal nodal values exist in people with diabetes at different ages.”

Dr. Neeland cautioned, “I think more work needs to be done in terms of not just identifying the risk differences but understanding why and how to better risk stratify individuals and do personalized medicine. I think that’s important, but you have to have good data to support the strategies you’re going to use. These data are observational, and they’re a good start, but they wouldn’t directly impact practice at this point.”

The data will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity taking place May 12-15 in Venice, Italy.

The authors declared no competing interests. Study funding came from several sources, including the Young Talents Project of Hubei Provincial Health Commission, China, Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, the Science and Technology Research Key Project of the Education Department of Hubei Province China, and the Sanuo Diabetes Charity Foundation, China, and the Xiangyang Science and Technology Plan Project, China. Dr. Neeland is a speaker and/or consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, and Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) older than 65 years, a body mass index (BMI) in the moderate overweight category (26-28) appears to offer better protection from cardiovascular death than does a BMI in the “normal” range, new data suggested.

On the other hand, the study findings also suggest that the “normal” range of 23-25 is optimal for middle-aged adults with T2D.

The findings reflect a previously demonstrated phenomenon called the “obesity paradox,” in which older people with overweight may have better outcomes than leaner people due to factors such as bone loss, frailty, and nutritional deficits, study lead author Shaoyong Xu, of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China, told this news organization.

“In this era of population growth and aging, the question arises as to whether obesity or overweight can be beneficial in improving survival rates for older individuals with diabetes. This topic holds significant relevance due to the potential implications it has on weight management strategies for older adults. If overweight does not pose an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, it may suggest that older individuals are not necessarily required to strive for weight loss to achieve so-called normal values.”

Moreover, Dr. Xu added, “inappropriate weight loss and being underweight could potentially elevate the risk of cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and all-cause mortality.”

Thus, he said, “while there are general guidelines recommending a BMI below 25, our findings suggest that personalized BMI targets may be more beneficial, particularly for different age groups and individuals with specific health conditions.”

Asked to comment, Ian J. Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, pointed out that older people who are underweight or in lower weight categories may be more likely to smoke or have undiagnosed cancer, or that “their BMI is not so much reflective of fat mass as of low muscle mass, or sarcopenia, and that is definitely a risk factor for adverse outcomes and risks. ... And those who have slightly higher BMIs may be maintaining muscle mass, even though they’re older, and therefore they have less risk.”

However, Dr. Neeland disagreed with the authors’ conclusions regarding “optimal” BMI. “Just because you have different risk categories based on BMI doesn’t mean that’s ‘optimal’ BMI. The way I would interpret this paper is that there’s an association of mildly overweight with better outcomes in adults who are over 65 with type 2 diabetes. We need to try to understand the mechanisms underlying that observation.”

Dr. Neeland advised that for an older person with T2D who has low muscle mass and frailty, “I wouldn’t recommend necessarily targeted weight loss in that person. But I would potentially recommend weight loss in addition to resistance training, muscle building, and endurance training, and therefore reducing fat mass. The goal would be not so much weight loss but reduction of body fat and maintaining and improving muscle health.”

U-Shaped Relationship Found Between Age, BMI, and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk

The data come from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. A total of 22,874 participants with baseline T2D were included in the current study. Baseline surveys were conducted between 2006 and 2010, and follow-up was a median of 12.52 years. During that time, 891 people died of CVD.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for baseline variables including age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, level of physical exercise, and history of CVDs.

Compared with people with BMI a < 25 in the group who were aged 65 years or younger, those with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 had a 13% higher risk for cardiovascular death. However, among those older than 65 years, a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 was associated with an 18% lower risk.

A U-shaped relationship was found between BMI and the risk for cardiovascular death, with an optimal BMI cutoff of 24.0 in the under-65 group and a 27.0 cutoff in the older group. Ranges of 23.0-25.0 in the under-65 group and 26.0-28 in the older group were associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, there was a linear relationship between both waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio and the risk for cardiovascular death, making those more direct measures of adiposity, Dr. Xu told this news organization.

“For clinicians, our data underscores the importance of considering age when assessing BMI targets for cardiovascular health. Personalized treatment plans that account for age-specific BMI cutoffs and other risk factors may enhance patient outcomes and reduce CVD mortality,” Dr. Xu said.

However, he added, “while these findings suggest an optimal BMI range, it is crucial to acknowledge that these cutoff points may vary based on gender, race, and other factors. Our future studies will validate these findings in different populations and attempt to explain the mechanism by which the optimal nodal values exist in people with diabetes at different ages.”

Dr. Neeland cautioned, “I think more work needs to be done in terms of not just identifying the risk differences but understanding why and how to better risk stratify individuals and do personalized medicine. I think that’s important, but you have to have good data to support the strategies you’re going to use. These data are observational, and they’re a good start, but they wouldn’t directly impact practice at this point.”

The data will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity taking place May 12-15 in Venice, Italy.

The authors declared no competing interests. Study funding came from several sources, including the Young Talents Project of Hubei Provincial Health Commission, China, Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, the Science and Technology Research Key Project of the Education Department of Hubei Province China, and the Sanuo Diabetes Charity Foundation, China, and the Xiangyang Science and Technology Plan Project, China. Dr. Neeland is a speaker and/or consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, and Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity in Children

How to Cure Hedonic Eating?

Logan is a 62-year-old woman who has reached the pinnacle of professional success. She started a $50 million consumer products company and, after selling it, managed to develop another successful brand. She is healthy and happily married, with four adult children. And yet, despite all her achievements and stable family life, Logan was always bothered by her inability to lose weight.

Despite peddling in beauty, she felt perpetually overweight and, frankly, unattractive. She has no family history of obesity, drinks minimal alcohol, and follows an (allegedly) healthy diet. Logan had tried “everything” to lose weight — human growth hormone injections (not prescribed by me), Ozempic-like medications, Belviq, etc. — all to no avail.

Here’s the catch: After she finished with her busy days of meetings and spreadsheets, Logan sat down to read through countless emails and rewarded herself with all her favorite foods. Without realizing it, she often doubled her daily caloric intake in one sitting. She wasn’t hungry in these moments, rather just a little worn out and perhaps a little careless. She then proceeded to email her doctor (me) to report on this endless cycle of unwanted behavior.

In January 2024, a novel study from Turkey examined the relationship between hedonic eating, self-condemnation, and self-esteem. Surprising to no one, the study determined that higher hedonic hunger scores were associated with lower self-esteem and an increased propensity to self-stigmatize.

Oprah could have handily predicted this conclusion. Many years ago, she described food as a fake friend: Perhaps you’ve had a long and difficult day. While you’re busy eating your feelings, the heaping plate of pasta feels like your best buddy in the world. However, the moment the plate is empty, you realize that you feel worse than before. Not only do you have to unbutton your new jeans, but you also realize that you have just lost your ability to self-regulate.

While the positive association between hedonic eating and low self-esteem may seem self-evident, the solution is less obvious. Mindfulness is one possible approach to this issue. Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” and has existed for thousands of years. Mindful eating, in particular, involves paying close attention to our food choices and how they affect our emotions, and typically includes some combination of:

- Slowing down eating/chewing thoroughly

- Eliminating distractions such as TV, computers, and phones — perhaps even eating in silence

- Eating only until physically satiated

- Distinguishing between true hunger and cravings

- Noticing the texture, flavors, and smell of food

- Paying attention to the effect of food on your mood

- Appreciating food

In our society, where processed food is so readily available and stress is so ubiquitous, eating can become a hedonic and fast-paced activity. Our brains don’t have time to process our bodies’ signals of fullness and, as a result, we often ingest many more calories than we need for a healthy lifestyle.

If mindless eating is part of the problem, mindful eating is part of the solution. Indeed, a meta-review of 10 scientific studies showed that mindful eating is as effective as conventional weight loss programs in regard to body mass index and waist circumference. On the basis of these studies — as well as some good old-fashioned common sense — intuitive eating is an important component of sustainable weight reduction.

Eventually, I convinced Logan to meet up with the psychologist in our group who specializes in emotional eating. Through weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, Logan was able to understand the impetus behind her self-defeating behavior and has finally been able to reverse some of her lifelong habits. Once she started practicing mindful eating, I was able to introduce Ozempic, and now Logan is happily shedding several pounds a week.

Dr. Messer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and associate professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York City.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Logan is a 62-year-old woman who has reached the pinnacle of professional success. She started a $50 million consumer products company and, after selling it, managed to develop another successful brand. She is healthy and happily married, with four adult children. And yet, despite all her achievements and stable family life, Logan was always bothered by her inability to lose weight.

Despite peddling in beauty, she felt perpetually overweight and, frankly, unattractive. She has no family history of obesity, drinks minimal alcohol, and follows an (allegedly) healthy diet. Logan had tried “everything” to lose weight — human growth hormone injections (not prescribed by me), Ozempic-like medications, Belviq, etc. — all to no avail.

Here’s the catch: After she finished with her busy days of meetings and spreadsheets, Logan sat down to read through countless emails and rewarded herself with all her favorite foods. Without realizing it, she often doubled her daily caloric intake in one sitting. She wasn’t hungry in these moments, rather just a little worn out and perhaps a little careless. She then proceeded to email her doctor (me) to report on this endless cycle of unwanted behavior.

In January 2024, a novel study from Turkey examined the relationship between hedonic eating, self-condemnation, and self-esteem. Surprising to no one, the study determined that higher hedonic hunger scores were associated with lower self-esteem and an increased propensity to self-stigmatize.

Oprah could have handily predicted this conclusion. Many years ago, she described food as a fake friend: Perhaps you’ve had a long and difficult day. While you’re busy eating your feelings, the heaping plate of pasta feels like your best buddy in the world. However, the moment the plate is empty, you realize that you feel worse than before. Not only do you have to unbutton your new jeans, but you also realize that you have just lost your ability to self-regulate.

While the positive association between hedonic eating and low self-esteem may seem self-evident, the solution is less obvious. Mindfulness is one possible approach to this issue. Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” and has existed for thousands of years. Mindful eating, in particular, involves paying close attention to our food choices and how they affect our emotions, and typically includes some combination of:

- Slowing down eating/chewing thoroughly

- Eliminating distractions such as TV, computers, and phones — perhaps even eating in silence

- Eating only until physically satiated

- Distinguishing between true hunger and cravings

- Noticing the texture, flavors, and smell of food

- Paying attention to the effect of food on your mood

- Appreciating food

In our society, where processed food is so readily available and stress is so ubiquitous, eating can become a hedonic and fast-paced activity. Our brains don’t have time to process our bodies’ signals of fullness and, as a result, we often ingest many more calories than we need for a healthy lifestyle.

If mindless eating is part of the problem, mindful eating is part of the solution. Indeed, a meta-review of 10 scientific studies showed that mindful eating is as effective as conventional weight loss programs in regard to body mass index and waist circumference. On the basis of these studies — as well as some good old-fashioned common sense — intuitive eating is an important component of sustainable weight reduction.

Eventually, I convinced Logan to meet up with the psychologist in our group who specializes in emotional eating. Through weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, Logan was able to understand the impetus behind her self-defeating behavior and has finally been able to reverse some of her lifelong habits. Once she started practicing mindful eating, I was able to introduce Ozempic, and now Logan is happily shedding several pounds a week.

Dr. Messer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and associate professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York City.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Logan is a 62-year-old woman who has reached the pinnacle of professional success. She started a $50 million consumer products company and, after selling it, managed to develop another successful brand. She is healthy and happily married, with four adult children. And yet, despite all her achievements and stable family life, Logan was always bothered by her inability to lose weight.

Despite peddling in beauty, she felt perpetually overweight and, frankly, unattractive. She has no family history of obesity, drinks minimal alcohol, and follows an (allegedly) healthy diet. Logan had tried “everything” to lose weight — human growth hormone injections (not prescribed by me), Ozempic-like medications, Belviq, etc. — all to no avail.

Here’s the catch: After she finished with her busy days of meetings and spreadsheets, Logan sat down to read through countless emails and rewarded herself with all her favorite foods. Without realizing it, she often doubled her daily caloric intake in one sitting. She wasn’t hungry in these moments, rather just a little worn out and perhaps a little careless. She then proceeded to email her doctor (me) to report on this endless cycle of unwanted behavior.

In January 2024, a novel study from Turkey examined the relationship between hedonic eating, self-condemnation, and self-esteem. Surprising to no one, the study determined that higher hedonic hunger scores were associated with lower self-esteem and an increased propensity to self-stigmatize.

Oprah could have handily predicted this conclusion. Many years ago, she described food as a fake friend: Perhaps you’ve had a long and difficult day. While you’re busy eating your feelings, the heaping plate of pasta feels like your best buddy in the world. However, the moment the plate is empty, you realize that you feel worse than before. Not only do you have to unbutton your new jeans, but you also realize that you have just lost your ability to self-regulate.

While the positive association between hedonic eating and low self-esteem may seem self-evident, the solution is less obvious. Mindfulness is one possible approach to this issue. Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” and has existed for thousands of years. Mindful eating, in particular, involves paying close attention to our food choices and how they affect our emotions, and typically includes some combination of:

- Slowing down eating/chewing thoroughly

- Eliminating distractions such as TV, computers, and phones — perhaps even eating in silence

- Eating only until physically satiated

- Distinguishing between true hunger and cravings

- Noticing the texture, flavors, and smell of food

- Paying attention to the effect of food on your mood

- Appreciating food

In our society, where processed food is so readily available and stress is so ubiquitous, eating can become a hedonic and fast-paced activity. Our brains don’t have time to process our bodies’ signals of fullness and, as a result, we often ingest many more calories than we need for a healthy lifestyle.

If mindless eating is part of the problem, mindful eating is part of the solution. Indeed, a meta-review of 10 scientific studies showed that mindful eating is as effective as conventional weight loss programs in regard to body mass index and waist circumference. On the basis of these studies — as well as some good old-fashioned common sense — intuitive eating is an important component of sustainable weight reduction.

Eventually, I convinced Logan to meet up with the psychologist in our group who specializes in emotional eating. Through weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, Logan was able to understand the impetus behind her self-defeating behavior and has finally been able to reverse some of her lifelong habits. Once she started practicing mindful eating, I was able to introduce Ozempic, and now Logan is happily shedding several pounds a week.

Dr. Messer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and associate professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York City.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study Highlights Some Semaglutide-Associated Skin Effects

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Do New Antiobesity Meds Still Require Lifestyle Management?

Is lifestyle counseling needed with the more effective second-generation nutrient-stimulated, hormone-based medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide?

If so, how intensive does the counseling need to be, and what components should be emphasized?

These are the clinical practice questions at the top of mind for healthcare professionals and researchers who provide care to patients who have overweight and/or obesity.

This is what we know. Lifestyle management is considered foundational in the care of patients with obesity.

Because obesity is fundamentally a disease of energy dysregulation, counseling has traditionally focused on dietary caloric reduction, increased physical activity, and strategies to adapt new cognitive and lifestyle behaviors.

On the basis of trial results from the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD studies, provision of intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) is recommended for treatment of obesity by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and by the US Preventive Services Task Force (Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force).

IBT is commonly defined as consisting of 12-26 comprehensive and multicomponent sessions over the course of a year.

Reaffirming the primacy of lifestyle management, all antiobesity medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

The beneficial effect of combining IBT with earlier-generation medications like naltrexone/bupropion or liraglutide demonstrated that more participants in the trials achieved ≥ 10% weight loss with IBT compared with those taking the medication without IBT: 38.4% vs 20% for naltrexone/bupropion and 46% vs 33% for liraglutide.

Although there aren’t trial data for other first-generation medications like phentermine, orlistat, or phentermine/topiramate, it is assumed that patients taking these medications would also achieve greater weight loss when combined with IBT.

The obesity pharmacotherapy landscape was upended, however, with the approval of semaglutide (Wegovy), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in 2021; and tirzepatide (Zepbound), a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide dual receptor agonist, in 2023.

These highly effective medications harness the effect of naturally occurring incretin hormones that reduce appetite through direct and indirect effects on the brain. Although the study designs differed between the STEP 1 and STEP 3 trials, the addition of IBT to semaglutide increased mean percent weight loss from 15% to 16% after 68 weeks of treatment (Wilding JPH et al; Wadden TA).

Comparable benefits from the STEP 3 and SURMOUNT-1 trials of adding IBT to tirzepatide at the maximal tolerated dose increased mean percent weight loss from 21% to 24% after 72 weeks (Wadden TA; Jastreboff AM). Though multicomponent IBT appears to provide greater weight loss when used with nutrient-stimulated hormone-based therapeutics, the additional benefit may be less when compared with first-generation medications.

So, how should we view the role and importance of lifestyle management when a patient is taking a second-generation medication? We need to shift the focus from prescribing a calorie-reduced diet to counseling for healthy eating patterns.

Because the second-generation drugs are more biologically effective in suppressing appetite (ie, reducing hunger, food noise, and cravings, and increasing satiation and satiety), it is easier for patients to reduce their food intake without a sense of deprivation. Furthermore, many patients express less desire to consume savory, sweet, and other enticing foods.

Patients should be encouraged to optimize the quality of their diet, prioritizing lean protein sources with meals and snacks; increasing fruits, vegetables, fiber, and complex carbohydrates; and keeping well hydrated. Because of the risk of developing micronutrient deficiencies while consuming a low-calorie diet — most notably calcium, iron, and vitamin D — patients may be advised to take a daily multivitamin supplement. Dietary counseling should be introduced when patients start pharmacotherapy, and if needed, referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist may be helpful in making these changes.

Additional counseling tips to mitigate the gastrointestinal side effects of these drugs that most commonly occur during the early dose-escalation phase include eating slowly; choosing smaller portion sizes; stopping eating when full; not skipping meals; and avoiding fatty, fried, and greasy foods. These dietary changes are particularly important over the first days after patients take the injection.

The increased weight loss achieved also raises concerns about the need to maintain lean body mass and the importance of physical activity and exercise counseling. All weight loss interventions, including dietary restriction, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, result in loss of fat mass and lean body mass.

The goal of lifestyle counseling is to minimize and preserve muscle mass (a component of lean body mass) which is needed for optimal health, mobility, daily function, and quality of life. Counseling should incorporate both aerobic and resistance training. Aerobic exercise (eg, brisk walking, jogging, dancing, elliptical machine, and cycling) improves cardiovascular fitness, metabolic health, and energy expenditure. Resistance (strength) training (eg, weightlifting, resistance bands, and circuit training) lessens the loss of muscle mass, enhances functional strength and mobility, and improves bone density (Gorgojo-Martinez JJ et al; Oppert JM et al).

Robust physical activity has also been shown to be a predictor of weight loss maintenance. A recently published randomized placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of supervised exercise in maintaining body weight and lean body mass after discontinuing 52 weeks of liraglutide treatment compared with no exercise.

Rather than minimizing the provision of lifestyle management, using highly effective second-generation therapeutics redirects the focus on how patients with obesity can strive to achieve a healthy and productive life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.