User login

Pregnancy boosts cardiac disease mortality nearly 100-fold

MUNICH – Women with cardiac disease who became pregnant had a nearly 100-fold higher mortality rate, compared with pregnant women without cardiac disease, according to the outcomes of more than 5,700 pregnancies in an international registry of women with cardiac disease.

In addition to increased mortality, women with cardiac disease who become pregnant also had a greater than 100-fold higher rate of developing heart failure, compared with pregnant women without cardiac disease.

Despite these highly elevated relative risks, the absolute rate of serious complications from pregnancy for most women with heart disease was relatively modest. The worst prognosis by far was for the 1% of women in the registry who had pulmonary arterial hypertension at the time their pregnancy began. For these women, mortality during pregnancy was about 9%, and new-onset heart failure occurred in about one third. Another subgroup showing particularly poor outcomes were women classified with WHO IV maternal cardiovascular risk by the modified World Health Organization criteria, which corresponds to having an “extremely high risk of maternal mortality or severe morbidity,” according to guidelines published in the European Heart Journal (2011 Dec 1;32[24]:3147-97).These women, constituting 7% of the registry cohort, had a 2.5% mortality rate during pregnancy and a 33% incidence of heart failure.

Across all women with cardiac disease enrolled in the registry, the incidence of death during pregnancy was 0.6% and the incidence of heart failure was 11%. Women without cardiac disease have rates of 0.007% and less than 0.1%, respectively, Jolien Roos-Hesselink, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“The most important message of my talk is that all patients should be counseled, not just the women at high risk, for whom pregnancy is contraindicated, but also the women at low risk,” who can have a child with relative safety, she said. “Many women [with cardiac disease] can go through pregnancy at low risk.” Counseling is the key so that women know their risk before becoming pregnant, stressed Dr. Roos-Hesselink, a cardiologist at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Based on the observed rates of mortality and other complications, pulmonary arterial hypertension and the other cardiac conditions that define a WHO IV maternal risk classification remain contraindications for pregnancy, she said. According to the 2011 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology for managing cardiovascular disease during pregnancy, the full list of conditions that define a WHO IV classification are the following:

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension of any cause.

- Severe systemic ventricular dysfunction (a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%) or New York Heart Association functional class III or IV.

- Previous peripartum cardiomyopathy with any residual impairment of left ventricular function.

- Severe mitral stenosis or severe symptomatic aortic stenosis.

- Marfan syndrome with the aorta dilated to more than 45 mm.

- Aortic dilatation greater than 50 mm in aortic disease associated with a bicuspid aortic valve.

- Native severe coarctation.

The registry data, collected during 2007-2018, showed a clear increase in the percentage of women with WHO class IV cardiovascular disease who became pregnant and entered the registry despite the contraindication designation for that classification, rising from about 1% of enrolled women in 2008 and 2009 to more than 10% of women in 2013, 2016, and 2017. “Individualization is necessary, but all these women are at very high risk and should be counseled against pregnancy,” Dr. Roos-Hesselink said.

The Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) enrolled 5,739 pregnant women at any of 138 participating centers in 53 countries including the United States. Clinicians submitted WHO classification of cardiovascular risk for 5,711 of these women. The most common risk was congenital heart disease in 57% of enrolled women, followed by valvular heart disease in 29% and cardiomyopathy in 7%. Nearly 1,200 women in the registry – about 21% of the total – had a WHO I classification, which meant that they would be expected to have no detectable increase in mortality rate during pregnancy, compared with women without cardiac disease, and either no rise in morbidity or a mild effect.

Delivery was by cesarean section in 44% of the pregnancies, roughly twice the rate in women without diagnosed cardiac disease, even though published guidelines don’t advise cesarean delivery because of cardiac disease, Dr. Roos-Hesselink said. “Cesarean sections are used too often, in my opinion,” she commented, but added that many of these women require delivery at a tertiary, specialized center.

Overall fetal mortality was 1%, nearly threefold higher than in pregnancies in women without cardiac disease, and the overall incidence of fetal and neonatal complications was especially high, at 53%, in women with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The incidence of obstetrical complications was roughly similar across the range of cardiac disease type, ranging from 16% to 24%. Premature delivery occurred in 28% of women in the high-risk WHO IV class, compared with a 13% rate among women in the WHO I class. The mortality rate was 0.2% among the WHO class I women, and their heart failure incidence was 5%.

The ROPAC registry is sponsored by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Roos-Hesselink had no disclosures.

MUNICH – Women with cardiac disease who became pregnant had a nearly 100-fold higher mortality rate, compared with pregnant women without cardiac disease, according to the outcomes of more than 5,700 pregnancies in an international registry of women with cardiac disease.

In addition to increased mortality, women with cardiac disease who become pregnant also had a greater than 100-fold higher rate of developing heart failure, compared with pregnant women without cardiac disease.

Despite these highly elevated relative risks, the absolute rate of serious complications from pregnancy for most women with heart disease was relatively modest. The worst prognosis by far was for the 1% of women in the registry who had pulmonary arterial hypertension at the time their pregnancy began. For these women, mortality during pregnancy was about 9%, and new-onset heart failure occurred in about one third. Another subgroup showing particularly poor outcomes were women classified with WHO IV maternal cardiovascular risk by the modified World Health Organization criteria, which corresponds to having an “extremely high risk of maternal mortality or severe morbidity,” according to guidelines published in the European Heart Journal (2011 Dec 1;32[24]:3147-97).These women, constituting 7% of the registry cohort, had a 2.5% mortality rate during pregnancy and a 33% incidence of heart failure.

Across all women with cardiac disease enrolled in the registry, the incidence of death during pregnancy was 0.6% and the incidence of heart failure was 11%. Women without cardiac disease have rates of 0.007% and less than 0.1%, respectively, Jolien Roos-Hesselink, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“The most important message of my talk is that all patients should be counseled, not just the women at high risk, for whom pregnancy is contraindicated, but also the women at low risk,” who can have a child with relative safety, she said. “Many women [with cardiac disease] can go through pregnancy at low risk.” Counseling is the key so that women know their risk before becoming pregnant, stressed Dr. Roos-Hesselink, a cardiologist at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Based on the observed rates of mortality and other complications, pulmonary arterial hypertension and the other cardiac conditions that define a WHO IV maternal risk classification remain contraindications for pregnancy, she said. According to the 2011 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology for managing cardiovascular disease during pregnancy, the full list of conditions that define a WHO IV classification are the following:

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension of any cause.

- Severe systemic ventricular dysfunction (a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%) or New York Heart Association functional class III or IV.

- Previous peripartum cardiomyopathy with any residual impairment of left ventricular function.

- Severe mitral stenosis or severe symptomatic aortic stenosis.

- Marfan syndrome with the aorta dilated to more than 45 mm.

- Aortic dilatation greater than 50 mm in aortic disease associated with a bicuspid aortic valve.

- Native severe coarctation.

The registry data, collected during 2007-2018, showed a clear increase in the percentage of women with WHO class IV cardiovascular disease who became pregnant and entered the registry despite the contraindication designation for that classification, rising from about 1% of enrolled women in 2008 and 2009 to more than 10% of women in 2013, 2016, and 2017. “Individualization is necessary, but all these women are at very high risk and should be counseled against pregnancy,” Dr. Roos-Hesselink said.

The Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) enrolled 5,739 pregnant women at any of 138 participating centers in 53 countries including the United States. Clinicians submitted WHO classification of cardiovascular risk for 5,711 of these women. The most common risk was congenital heart disease in 57% of enrolled women, followed by valvular heart disease in 29% and cardiomyopathy in 7%. Nearly 1,200 women in the registry – about 21% of the total – had a WHO I classification, which meant that they would be expected to have no detectable increase in mortality rate during pregnancy, compared with women without cardiac disease, and either no rise in morbidity or a mild effect.

Delivery was by cesarean section in 44% of the pregnancies, roughly twice the rate in women without diagnosed cardiac disease, even though published guidelines don’t advise cesarean delivery because of cardiac disease, Dr. Roos-Hesselink said. “Cesarean sections are used too often, in my opinion,” she commented, but added that many of these women require delivery at a tertiary, specialized center.

Overall fetal mortality was 1%, nearly threefold higher than in pregnancies in women without cardiac disease, and the overall incidence of fetal and neonatal complications was especially high, at 53%, in women with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The incidence of obstetrical complications was roughly similar across the range of cardiac disease type, ranging from 16% to 24%. Premature delivery occurred in 28% of women in the high-risk WHO IV class, compared with a 13% rate among women in the WHO I class. The mortality rate was 0.2% among the WHO class I women, and their heart failure incidence was 5%.

The ROPAC registry is sponsored by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Roos-Hesselink had no disclosures.

MUNICH – Women with cardiac disease who became pregnant had a nearly 100-fold higher mortality rate, compared with pregnant women without cardiac disease, according to the outcomes of more than 5,700 pregnancies in an international registry of women with cardiac disease.

In addition to increased mortality, women with cardiac disease who become pregnant also had a greater than 100-fold higher rate of developing heart failure, compared with pregnant women without cardiac disease.

Despite these highly elevated relative risks, the absolute rate of serious complications from pregnancy for most women with heart disease was relatively modest. The worst prognosis by far was for the 1% of women in the registry who had pulmonary arterial hypertension at the time their pregnancy began. For these women, mortality during pregnancy was about 9%, and new-onset heart failure occurred in about one third. Another subgroup showing particularly poor outcomes were women classified with WHO IV maternal cardiovascular risk by the modified World Health Organization criteria, which corresponds to having an “extremely high risk of maternal mortality or severe morbidity,” according to guidelines published in the European Heart Journal (2011 Dec 1;32[24]:3147-97).These women, constituting 7% of the registry cohort, had a 2.5% mortality rate during pregnancy and a 33% incidence of heart failure.

Across all women with cardiac disease enrolled in the registry, the incidence of death during pregnancy was 0.6% and the incidence of heart failure was 11%. Women without cardiac disease have rates of 0.007% and less than 0.1%, respectively, Jolien Roos-Hesselink, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“The most important message of my talk is that all patients should be counseled, not just the women at high risk, for whom pregnancy is contraindicated, but also the women at low risk,” who can have a child with relative safety, she said. “Many women [with cardiac disease] can go through pregnancy at low risk.” Counseling is the key so that women know their risk before becoming pregnant, stressed Dr. Roos-Hesselink, a cardiologist at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Based on the observed rates of mortality and other complications, pulmonary arterial hypertension and the other cardiac conditions that define a WHO IV maternal risk classification remain contraindications for pregnancy, she said. According to the 2011 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology for managing cardiovascular disease during pregnancy, the full list of conditions that define a WHO IV classification are the following:

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension of any cause.

- Severe systemic ventricular dysfunction (a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%) or New York Heart Association functional class III or IV.

- Previous peripartum cardiomyopathy with any residual impairment of left ventricular function.

- Severe mitral stenosis or severe symptomatic aortic stenosis.

- Marfan syndrome with the aorta dilated to more than 45 mm.

- Aortic dilatation greater than 50 mm in aortic disease associated with a bicuspid aortic valve.

- Native severe coarctation.

The registry data, collected during 2007-2018, showed a clear increase in the percentage of women with WHO class IV cardiovascular disease who became pregnant and entered the registry despite the contraindication designation for that classification, rising from about 1% of enrolled women in 2008 and 2009 to more than 10% of women in 2013, 2016, and 2017. “Individualization is necessary, but all these women are at very high risk and should be counseled against pregnancy,” Dr. Roos-Hesselink said.

The Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) enrolled 5,739 pregnant women at any of 138 participating centers in 53 countries including the United States. Clinicians submitted WHO classification of cardiovascular risk for 5,711 of these women. The most common risk was congenital heart disease in 57% of enrolled women, followed by valvular heart disease in 29% and cardiomyopathy in 7%. Nearly 1,200 women in the registry – about 21% of the total – had a WHO I classification, which meant that they would be expected to have no detectable increase in mortality rate during pregnancy, compared with women without cardiac disease, and either no rise in morbidity or a mild effect.

Delivery was by cesarean section in 44% of the pregnancies, roughly twice the rate in women without diagnosed cardiac disease, even though published guidelines don’t advise cesarean delivery because of cardiac disease, Dr. Roos-Hesselink said. “Cesarean sections are used too often, in my opinion,” she commented, but added that many of these women require delivery at a tertiary, specialized center.

Overall fetal mortality was 1%, nearly threefold higher than in pregnancies in women without cardiac disease, and the overall incidence of fetal and neonatal complications was especially high, at 53%, in women with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The incidence of obstetrical complications was roughly similar across the range of cardiac disease type, ranging from 16% to 24%. Premature delivery occurred in 28% of women in the high-risk WHO IV class, compared with a 13% rate among women in the WHO I class. The mortality rate was 0.2% among the WHO class I women, and their heart failure incidence was 5%.

The ROPAC registry is sponsored by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Roos-Hesselink had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: Women with cardiac disease who became pregnant had substantially increased mortality and morbidity.

Major finding: Pregnancy mortality was 0.6% in women with cardiac disease versus 0.007% in women without cardiac disorders.

Study details: The ROPAC registry, which enrolled 5,739 pregnant women at any of 138 centers in 53 countries during 2007-2018.

Disclosures: The ROPAC registry is sponsored by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Roos-Hesselink had no disclosures.

How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The opioid crisis: Treating pregnant women with addiction

Product Update: PICO NPWT; Encision; TimerCap; AMA

SURGICAL SITE WOUND THERAPY

PICO NPWT is a negative-pressure wound therapy device to treat surgical site infection (SSI). According to Smith & Nephew, a new meta-analysis demonstrates that the prophylactic application of PICO with AIRLOCK™ Technology significantly reduces surgical site complications by 58%, the rate of dehiscence by 26%, and length of stay by one-half day when compared with standard care.

The PICO System is canister-free and disposable. Patients can be discharged safely with PICO in place. Seven days of therapy are provided in each kit, with 1 pump, 2 dressings, and fixation strips to allow for a dressing change.

PICO uses a 4-layer multifunction dressing design in which the layers work together to ensure that negative pressure is delivered to the wound bed and exudate is removed through absorption and evaporation. Approximately 20% of fluid still remains in the dressing. The top film layer has a high-moisture vapor transmission rate to transpire as much as 80% of the exudate, says Smith & Nephew.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.smith-nephew.com/

SHIELDED LAPAROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTS PREVENT BURNS

Encision’s patented Active Electrode Monitoring (AEM®) Shielded Laparoscopic Instruments eliminate patient burns and the associated complications.

Every 90 minutes in the United States, a patient is severely injured from a stray energy burn during laparoscopic surgery, according to Encision. The AEM® Shielded Instruments are designed to eliminate burns caused by monopolar energy insulation failure and capacitive coupling, reducing complications and re-admissions.

In addition to helping health care professionals improve patient safety in line with a recent FDA safety communication, Active Electrode Monitoring is a recommended practice of AORN and AAGL.

Encision offers a complete line of premium laparoscopic monopolar surgical instruments with integrated AEM® technology as well as complimentary products to improve clinical effectiveness and patient safety, including bipolar and cold instrumentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.encision.com/

iSORT: 7-DAY BLUETOOTH PILLBOX

TimerCap has a new Bluetooth-enabled 7-day pill box called the iSort that sends reminders to take medication to a patient’s phone using a free TimerCap App found at the AppStore and Android Market.

The iSort automatically records and stores the times when each door/slot is opened and closed. It knows which door has been used and seamlessly updates the TimerCap App. The app will notify the patient and, if designated, a caregiver, whenever a dose is due or missed using pictures to show what and how many meds are scheduled. More than one iSort box can be used with the app.

iSort provides reminders that help improve adherence to medication dosing instructions and eliminates annoying false alarms, double entries, and unnecessary reminders when pills already have been taken. The portable iSort uses 2 AA batteries that need to be changed about once per year.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.timercap.com/isort

PLATFORM TO COORDINATE HEALTH AND TECHNOLOGY

The American Medical Association (AMA) recently has established a new initiative that introduces a solution to improve, organize, and share health care information. The Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) is a platform that coordinates the health and technology sectors around a common data model. IHMI fills the national imperative to pioneer a shared framework for organizing health data, emphasizing patient-centric information, and refining data elements to those most predictive of better outcomes. The AMA says that evolving available health data to depict a complete picture of a patient’s journey from wellness to illness to treatment and beyond allows health care delivery to fully focus on patient outcomes, goals, and wellness. Participation in IHMI is open to all health care and technology stakeholders.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.ama-assn.org/ihmi

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

SURGICAL SITE WOUND THERAPY

PICO NPWT is a negative-pressure wound therapy device to treat surgical site infection (SSI). According to Smith & Nephew, a new meta-analysis demonstrates that the prophylactic application of PICO with AIRLOCK™ Technology significantly reduces surgical site complications by 58%, the rate of dehiscence by 26%, and length of stay by one-half day when compared with standard care.

The PICO System is canister-free and disposable. Patients can be discharged safely with PICO in place. Seven days of therapy are provided in each kit, with 1 pump, 2 dressings, and fixation strips to allow for a dressing change.

PICO uses a 4-layer multifunction dressing design in which the layers work together to ensure that negative pressure is delivered to the wound bed and exudate is removed through absorption and evaporation. Approximately 20% of fluid still remains in the dressing. The top film layer has a high-moisture vapor transmission rate to transpire as much as 80% of the exudate, says Smith & Nephew.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.smith-nephew.com/

SHIELDED LAPAROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTS PREVENT BURNS

Encision’s patented Active Electrode Monitoring (AEM®) Shielded Laparoscopic Instruments eliminate patient burns and the associated complications.

Every 90 minutes in the United States, a patient is severely injured from a stray energy burn during laparoscopic surgery, according to Encision. The AEM® Shielded Instruments are designed to eliminate burns caused by monopolar energy insulation failure and capacitive coupling, reducing complications and re-admissions.

In addition to helping health care professionals improve patient safety in line with a recent FDA safety communication, Active Electrode Monitoring is a recommended practice of AORN and AAGL.

Encision offers a complete line of premium laparoscopic monopolar surgical instruments with integrated AEM® technology as well as complimentary products to improve clinical effectiveness and patient safety, including bipolar and cold instrumentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.encision.com/

iSORT: 7-DAY BLUETOOTH PILLBOX

TimerCap has a new Bluetooth-enabled 7-day pill box called the iSort that sends reminders to take medication to a patient’s phone using a free TimerCap App found at the AppStore and Android Market.

The iSort automatically records and stores the times when each door/slot is opened and closed. It knows which door has been used and seamlessly updates the TimerCap App. The app will notify the patient and, if designated, a caregiver, whenever a dose is due or missed using pictures to show what and how many meds are scheduled. More than one iSort box can be used with the app.

iSort provides reminders that help improve adherence to medication dosing instructions and eliminates annoying false alarms, double entries, and unnecessary reminders when pills already have been taken. The portable iSort uses 2 AA batteries that need to be changed about once per year.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.timercap.com/isort

PLATFORM TO COORDINATE HEALTH AND TECHNOLOGY

The American Medical Association (AMA) recently has established a new initiative that introduces a solution to improve, organize, and share health care information. The Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) is a platform that coordinates the health and technology sectors around a common data model. IHMI fills the national imperative to pioneer a shared framework for organizing health data, emphasizing patient-centric information, and refining data elements to those most predictive of better outcomes. The AMA says that evolving available health data to depict a complete picture of a patient’s journey from wellness to illness to treatment and beyond allows health care delivery to fully focus on patient outcomes, goals, and wellness. Participation in IHMI is open to all health care and technology stakeholders.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.ama-assn.org/ihmi

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

SURGICAL SITE WOUND THERAPY

PICO NPWT is a negative-pressure wound therapy device to treat surgical site infection (SSI). According to Smith & Nephew, a new meta-analysis demonstrates that the prophylactic application of PICO with AIRLOCK™ Technology significantly reduces surgical site complications by 58%, the rate of dehiscence by 26%, and length of stay by one-half day when compared with standard care.

The PICO System is canister-free and disposable. Patients can be discharged safely with PICO in place. Seven days of therapy are provided in each kit, with 1 pump, 2 dressings, and fixation strips to allow for a dressing change.

PICO uses a 4-layer multifunction dressing design in which the layers work together to ensure that negative pressure is delivered to the wound bed and exudate is removed through absorption and evaporation. Approximately 20% of fluid still remains in the dressing. The top film layer has a high-moisture vapor transmission rate to transpire as much as 80% of the exudate, says Smith & Nephew.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.smith-nephew.com/

SHIELDED LAPAROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTS PREVENT BURNS

Encision’s patented Active Electrode Monitoring (AEM®) Shielded Laparoscopic Instruments eliminate patient burns and the associated complications.

Every 90 minutes in the United States, a patient is severely injured from a stray energy burn during laparoscopic surgery, according to Encision. The AEM® Shielded Instruments are designed to eliminate burns caused by monopolar energy insulation failure and capacitive coupling, reducing complications and re-admissions.

In addition to helping health care professionals improve patient safety in line with a recent FDA safety communication, Active Electrode Monitoring is a recommended practice of AORN and AAGL.

Encision offers a complete line of premium laparoscopic monopolar surgical instruments with integrated AEM® technology as well as complimentary products to improve clinical effectiveness and patient safety, including bipolar and cold instrumentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.encision.com/

iSORT: 7-DAY BLUETOOTH PILLBOX

TimerCap has a new Bluetooth-enabled 7-day pill box called the iSort that sends reminders to take medication to a patient’s phone using a free TimerCap App found at the AppStore and Android Market.

The iSort automatically records and stores the times when each door/slot is opened and closed. It knows which door has been used and seamlessly updates the TimerCap App. The app will notify the patient and, if designated, a caregiver, whenever a dose is due or missed using pictures to show what and how many meds are scheduled. More than one iSort box can be used with the app.

iSort provides reminders that help improve adherence to medication dosing instructions and eliminates annoying false alarms, double entries, and unnecessary reminders when pills already have been taken. The portable iSort uses 2 AA batteries that need to be changed about once per year.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.timercap.com/isort

PLATFORM TO COORDINATE HEALTH AND TECHNOLOGY

The American Medical Association (AMA) recently has established a new initiative that introduces a solution to improve, organize, and share health care information. The Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) is a platform that coordinates the health and technology sectors around a common data model. IHMI fills the national imperative to pioneer a shared framework for organizing health data, emphasizing patient-centric information, and refining data elements to those most predictive of better outcomes. The AMA says that evolving available health data to depict a complete picture of a patient’s journey from wellness to illness to treatment and beyond allows health care delivery to fully focus on patient outcomes, goals, and wellness. Participation in IHMI is open to all health care and technology stakeholders.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.ama-assn.org/ihmi

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Importance of providing standardized management of hypertension in pregnancy

CASE Onset of nausea and headache, and elevated BP, at full term

A 24-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 2/7 weeks of gestation without significant medical history and with uncomplicated prenatal care presents to labor and delivery reporting uterine contractions. She reports nausea and vomiting, and reports having a severe headache this morning. Blood pressure (BP) is 154/98 mm Hg. Urine dipstick analysis demonstrates absence of protein.

How should this patient be managed?

Although we have gained a greater understanding of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy—most notably, preeclampsia—during the past 15 years, management of these patients can, as evidenced in the case above, be complicated. Providers must respect this disease and be cognizant of the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications that can be associated with hypertension during pregnancy—a leading cause of preterm birth and maternal mortality in the United States.1-3 Initiation of early and aggressive antihypertensive medical therapy, when indicated, plays a key role in preventing catastrophic complications of this disease.

Terminology and classification

Hypertension of pregnancy is classified as:

- chronic hypertension: BP≥140/90 mm Hg prior to pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Patients who have persistently elevated BP 12 weeks after delivery are also in this category.

- preeclampsia–eclampsia: hypertension along with multisystem involvement that occurs after 20 weeks of gestation.

- gestational hypertension: hypertension alone after 20 weeks of gestation; in approximately 15% to 25% of these patients, a diagnosis of preeclampsia will be made as pregnancy progresses.

- chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia: hypertension complicated by development of multisystem involvement during the course of the pregnancy—often a challenging diagnosis, associated with greater perinatal morbidity than either chronic hypertension or preeclampsia alone.

Evaluation of the hypertensive gravida

Although most pregnant patients (approximately 90%) who have a diagnosis of chronic hypertension have primary or essential hypertension, a secondary cause—including thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and underlying renal disease—might be present and should be sought out. It is important, therefore, to obtain a comprehensive history along with a directed physical examination and appropriate laboratory tests.

Ideally, a patient with chronic hypertension should be evaluated prior to pregnancy, but this rarely occurs. At the initial encounter, the patient should be informed of risks associated with chronic hypertension, as well as receive education on the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Obtain a thorough history—not only to evaluate for secondary causes of hypertension or end-organ involvement (eg, kidney disease), but to identify comorbidities (such as pregestational diabetes mellitus). The patient should be instructed to immediately discontinue any teratogenic medication (such as an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker).

Routine laboratory evaluation

Testing should comprise a chemistry panel to evaluate serum creatinine, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. A 24-hour urine collection for protein excretion and creatinine clearance or a urine protein–creatinine ratio should be obtained to record baseline kidney function.4 (Such testing is important, given that new-onset or worsening proteinuria is a manifestation of superimposed preeclampsia.) All pregnant patients with chronic hypertension also should have a complete blood count, including a platelet count, and an early screen for gestational diabetes.

Depending on what information is obtained from the history and physical examination, renal ultrasonography and any of several laboratory tests can be ordered, including thyroid function, an SLE panel, and vanillylmandelic acid/metanephrines. If the patient has a history of severe hypertension for greater than 5 years, is older than 40 years, or has cardiac symptoms, baseline electrocardio-graphy or echocardiography, or both, are recommended.

Clinical manifestations of chronic hypertension during pregnancy include5:

- in the mother: accelerated hypertension, with resulting target-organ damage involving heart, brain, and kidneys

- in the fetus: placental abruption, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death.

What should treatment seek to accomplish?

The goal of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy is to reduce maternal risk of stroke, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and severe hypertension. No convincing evidence exists that antihypertensive medications decrease the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia, preterm birth, placental abruption, or perinatal death.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), antihypertensive medication is not indicated in patients with uncomplicated chronic hypertension unless systolic BP is ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 105 mm Hg.3 The goal is to maintain systolic BP at 120–160 mm Hg and diastolic BP at 80–105 mm Hg. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends treatment of hypertension when systolic BP is ≥ 150 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 100 mm Hg.6 In patients with end-organ disease (chronic renal or cardiac disease) ACOG recommends treatment with an antihypertensive when systolic BP is >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP is >90 mm Hg.

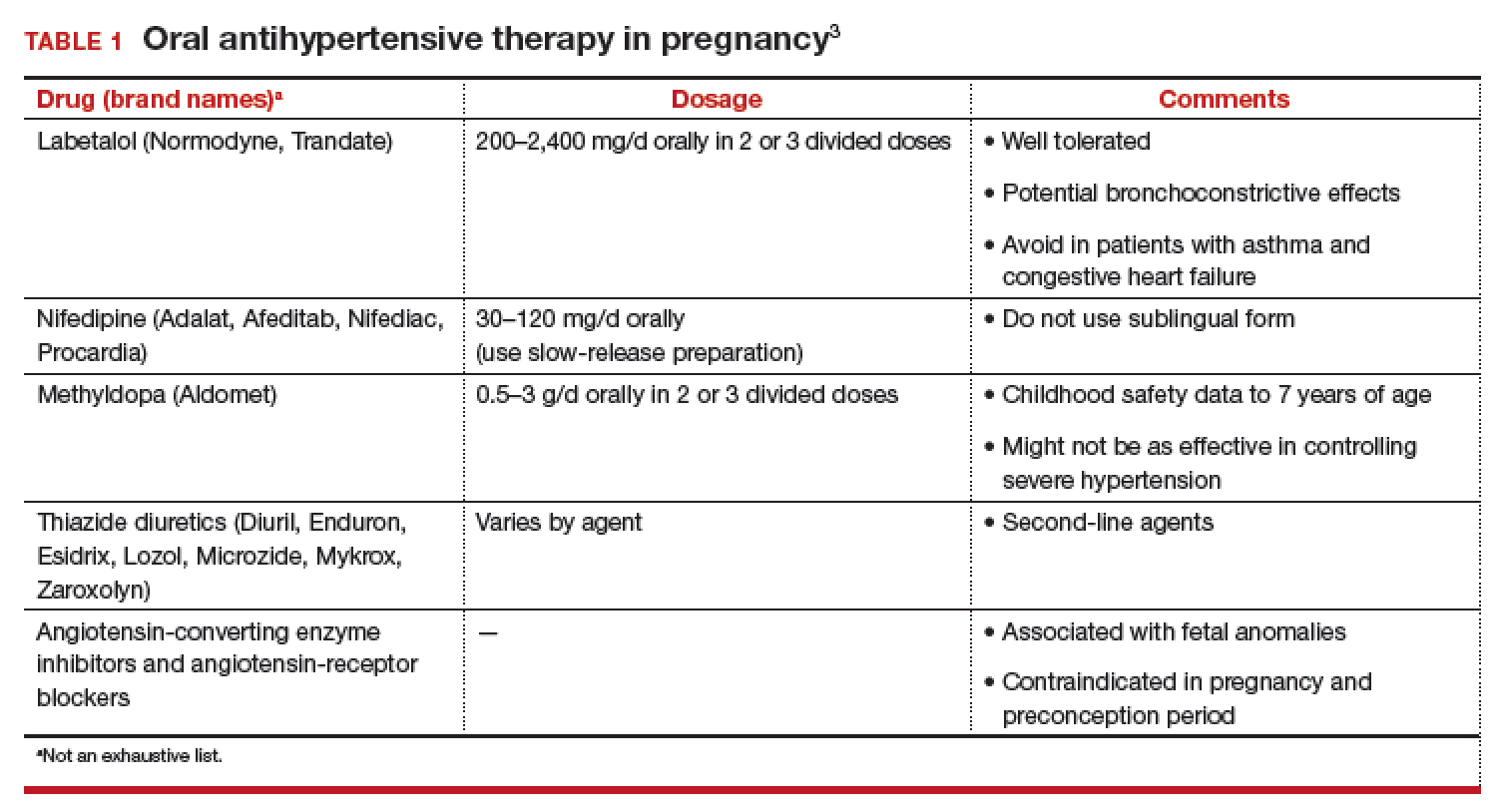

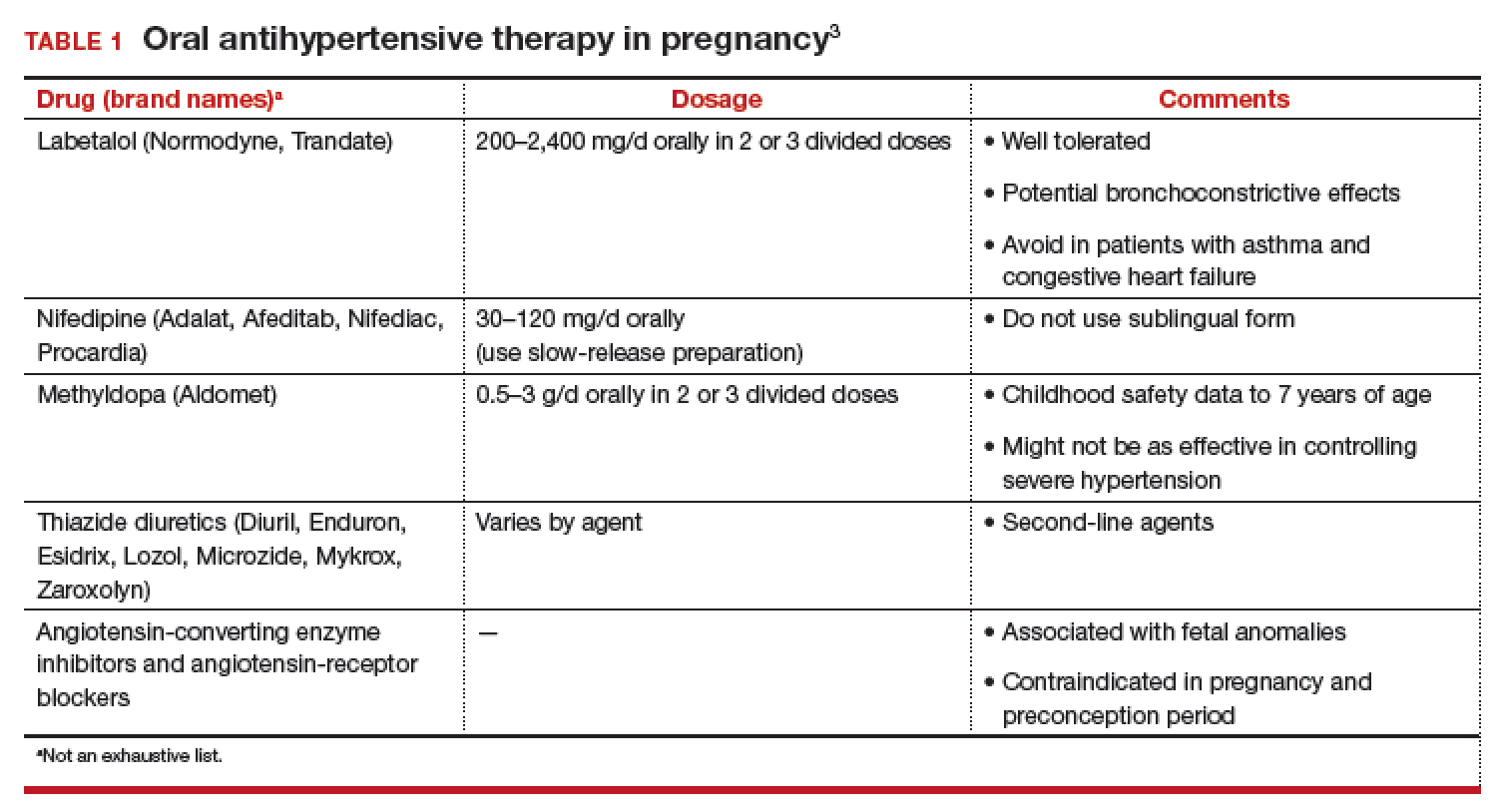

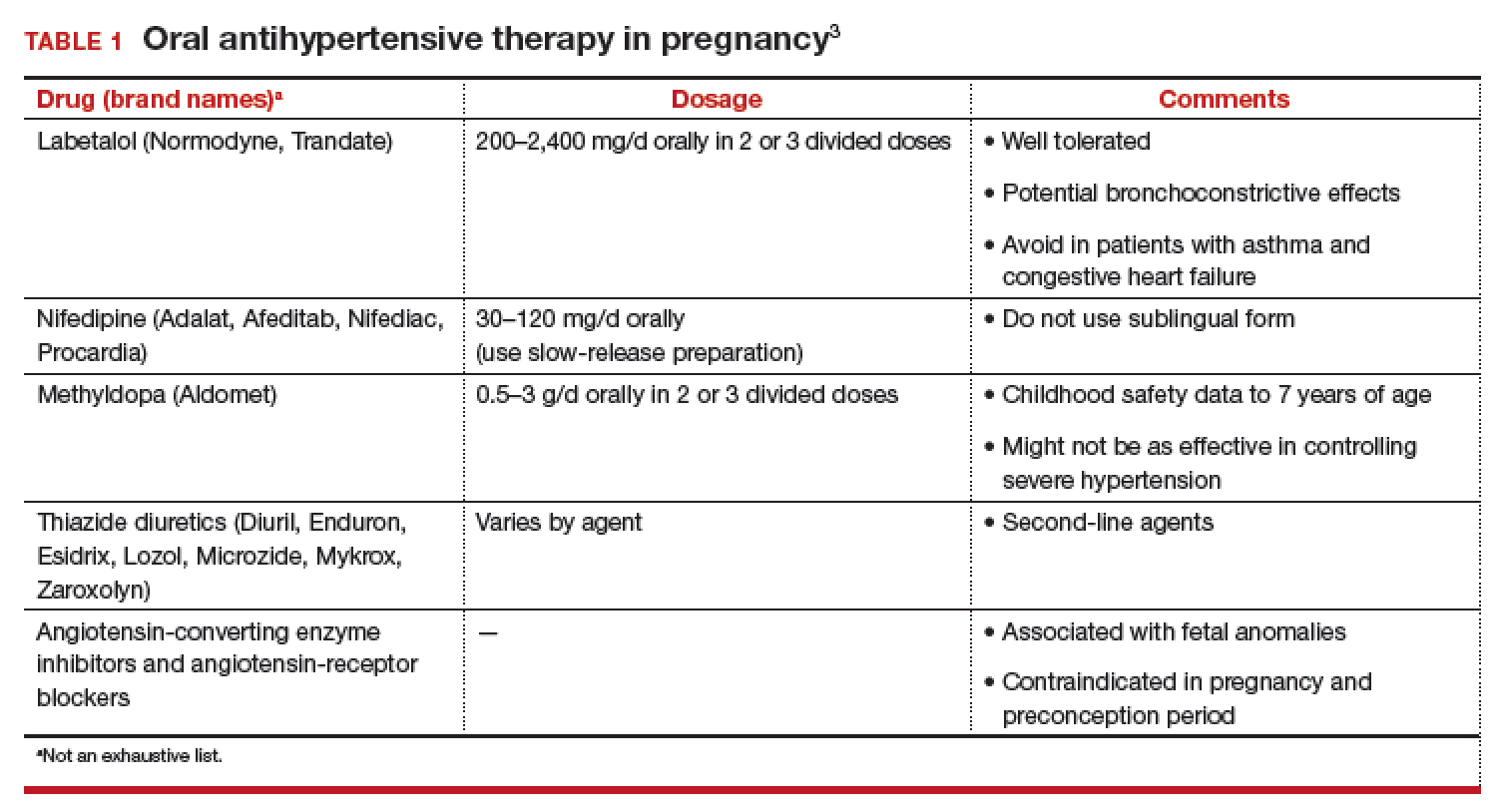

First-line antihypertensives consideredsafe during pregnancy are methyldopa, labetalol, and nifedipine. Thiazide diuretics, although considered second-line agents, may be used during pregnancy—especially if BP is adequately controlled prior to pregnancy. Again, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers are contraindicated during pregnancy (TABLE 1).3

Continuing care in chronic hypertension

Given the maternal and fetal consequences of chronic hypertension, it is recommended that a hypertensive patient be followed closely as an outpatient; in fact, it is advisablethat she check her BP at least twice daily. Beginning at 24 weeks of gestation, serial ultrasonography should be performed every 4 to 6 weeks to evaluate interval fetal growth. Twice-weekly antepartum testing should begin at 32 to 34 weeks of gestation.

During the course of the pregnancy, the chronically hypertensive patient should be observed closely for development of superimposed preeclampsia. If she does not develop preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction, and has no other pregnancy complications that necessitate early delivery, 3 recommendations regarding timing of delivery apply7:

- If the patient is not taking antihypertensive medication, delivery should occur at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation

- If hypertension is controlled with medication, delivery is recommended at 37 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation.

- If the patient has severe hypertension that is difficult to control, delivery might be advisable as early as 36 weeks of gestation.

Be vigilant for maternal complications (including cardiac compromise, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, hypertensive encephalopathy, and worsening renal disease) and fetal complications (such as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death). If any of these occur, management must be tailored and individualized accordingly. Study results have demonstrated that superimposed preeclampsia occurs in 20% to 30% of patients who have underlying mild chronic hypertension. This increases to 50% in women with underlying severe hypertension.8

Antihypertensive medication is the mainstay of treatment for severely elevated blood pressure (BP). To avoid fetal heart rate decelerations and possible emergent cesarean delivery, however, do not decrease BP too quickly or lower to values that might compromise perfusion to the fetus. The BP goal should be 140-155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90-105 mm Hg (diastolic). A

Be prepared for eclampsia, which is unpredictable and can occur in patients without symptoms or severely elevated BP and even postpartum in patients in whom the diagnosis of preeclampsia was never made prior to delivery. The response to eclamptic seizure includes administering magnesium sulfate, which is the approved initial therapy for an eclamptic seizure. A

Make algorithms for acute treatment of severe hypertension and eclampsia readily available or posted in labor and delivery units and in the emergency department. C

Counsel high-risk patients about the potential benefit of low-dosage aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. A

Strength of recommendation:

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The complex challenge of managing preeclampsia

Chronic hypertension is not the only risk factor for preeclampsia; others include nulliparity, history of preeclampsia, multifetal gestation, underlying renal disease, SLE, antiphospolipid syndrome, thyroid disease, and pregestational diabetes. Furthermore, preeclampsia has a bimodal age distribution, occurring more often in adolescent pregnancies and women of advanced maternal age. Risk is also increased in the presence of abnormal levels of various serum analytes or biochemical markers, such as a low level of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A or estriol or an elevated level of maternal serum α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, or inhibin—findings that might reflect abnormal placentation.9

In fact, the findings of most studies that have looked at the pathophysiology of preeclampsia appear to show that several noteworthy pathophysiologic changes are evident in early pregnancy10,11:

- incomplete trophoblastic invasion of spiral arteries

- retention of thick-walled, muscular arteries

- decreased placental perfusion

- early placental hypoxia

- placental release of factors that lead to endothelial dysfunction and endothelial damage.

Ultimately, vasoconstriction becomes evident, which leads to clinical manifestations of the disorder. In addition, there is an increase in the level of thromboxane (a vasoconstrictor and platelet aggregator), compared to the level of prostacyclin (a vasodilator).

ACOG revises nomenclature, provides recommendations

The considerable expansion of knowledge about preeclampsia over the past 10 to 15 years has not translated to better outcomes. In 2012, ACOG, in response to troubling observations about the condition (see “ACOG finds compelling motivation to boost understanding, management of preeclampsia,”), created a Task Force to investigate hypertension in pregnancy.

Findings and recommendations of the Task Force were published in November 2013,3 and have been endorsed and supported by professional organizations, including the American Academy of Neurology, American Society of Hypertension, Preeclampsia Foundation, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. A major premise of the Task Force that has had a direct impact on recommendations for management of preeclampsia is that the condition is a progressive and dynamic process that involves multiple organ systems and is not specifically confined to the antepartum period.

The nomenclature of mild preeclampsia and severe preeclampsia was changed in the Task Force report to preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. Preeclampsia without severe features is diagnosed when a patient has:

- systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg (measured twice at least 4 hours apart)

- proteinuria, defined as a 24-hour urine collection of ≥ 300 mg of protein or a urine protein–creatinine ratio of 0.3.

If a patient has elevated BP by those criteria, plus any of several laboratory indicators of multisystem involvement (platelet count, <100 × 103/μL; serum creatinine level, >1.1 mg/dL; doubling in the serum creatinine concentration; liver transaminase concentrations twice normal) or other findings (pulmonary edema, visual disturbance, headaches), she has preeclampsia with severe features. A diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features is upgraded to preeclampsia with severe features if systolic BP increases to >160 mm Hgor diastolic BP increases to >110 mm Hg (determined by 2 measurements 4 hours apart) or if “severe”-range BP occurs with such rapidity that acute antihypertensive medication is required.

- Incidence of preeclampsia in the United States has increased by 25% over the past 2 decades

- Etiology remains unclear

- Leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality

- Risk factor for future cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease in women

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are major contributors to prematurity

- New best-practice recommendations are urgently needed to guide clinicians in the care of women with all forms of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

- Improved patient education and counseling strategies are needed to convey, more effectively, the dangers of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

Reference

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive emergency

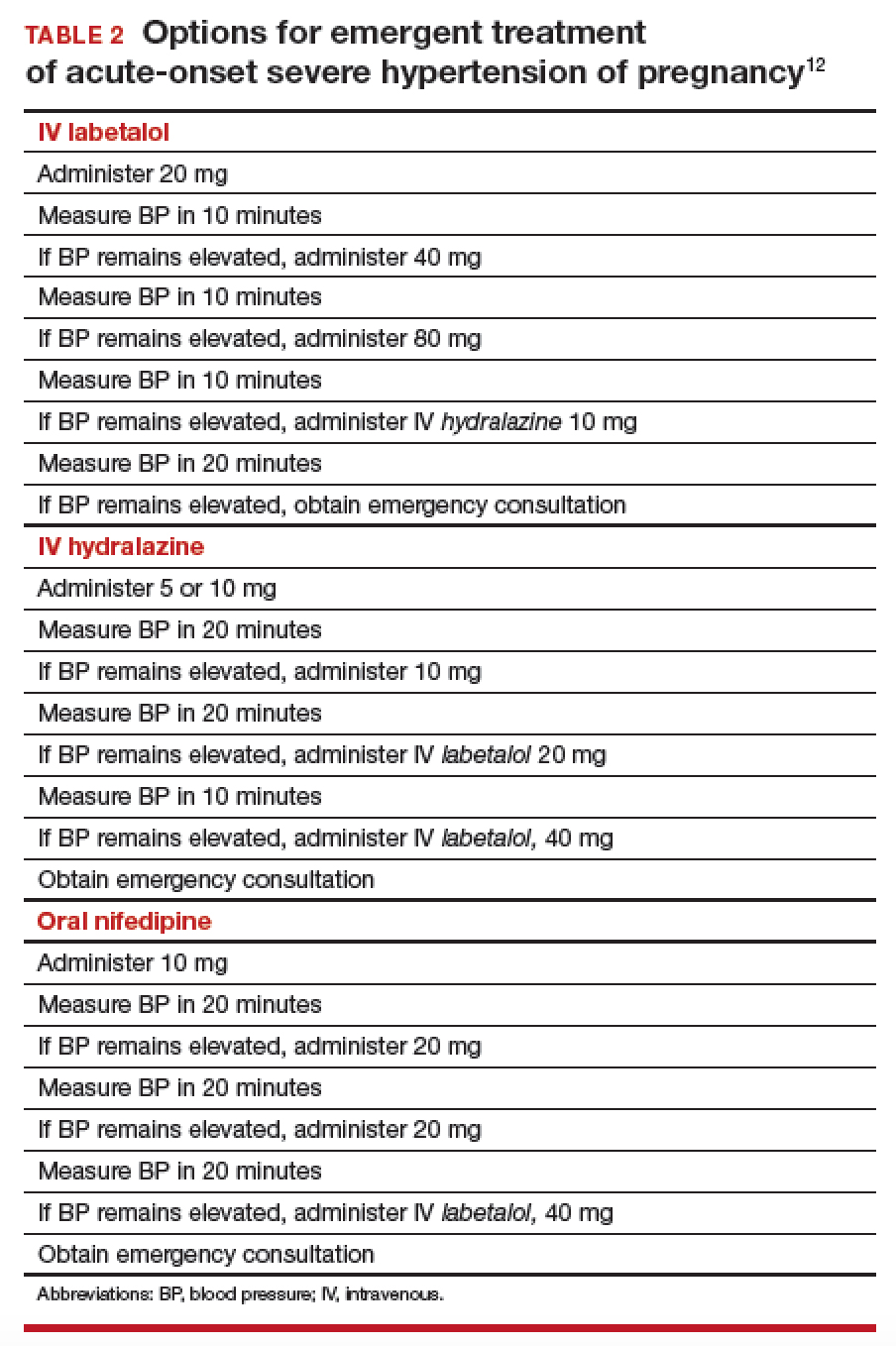

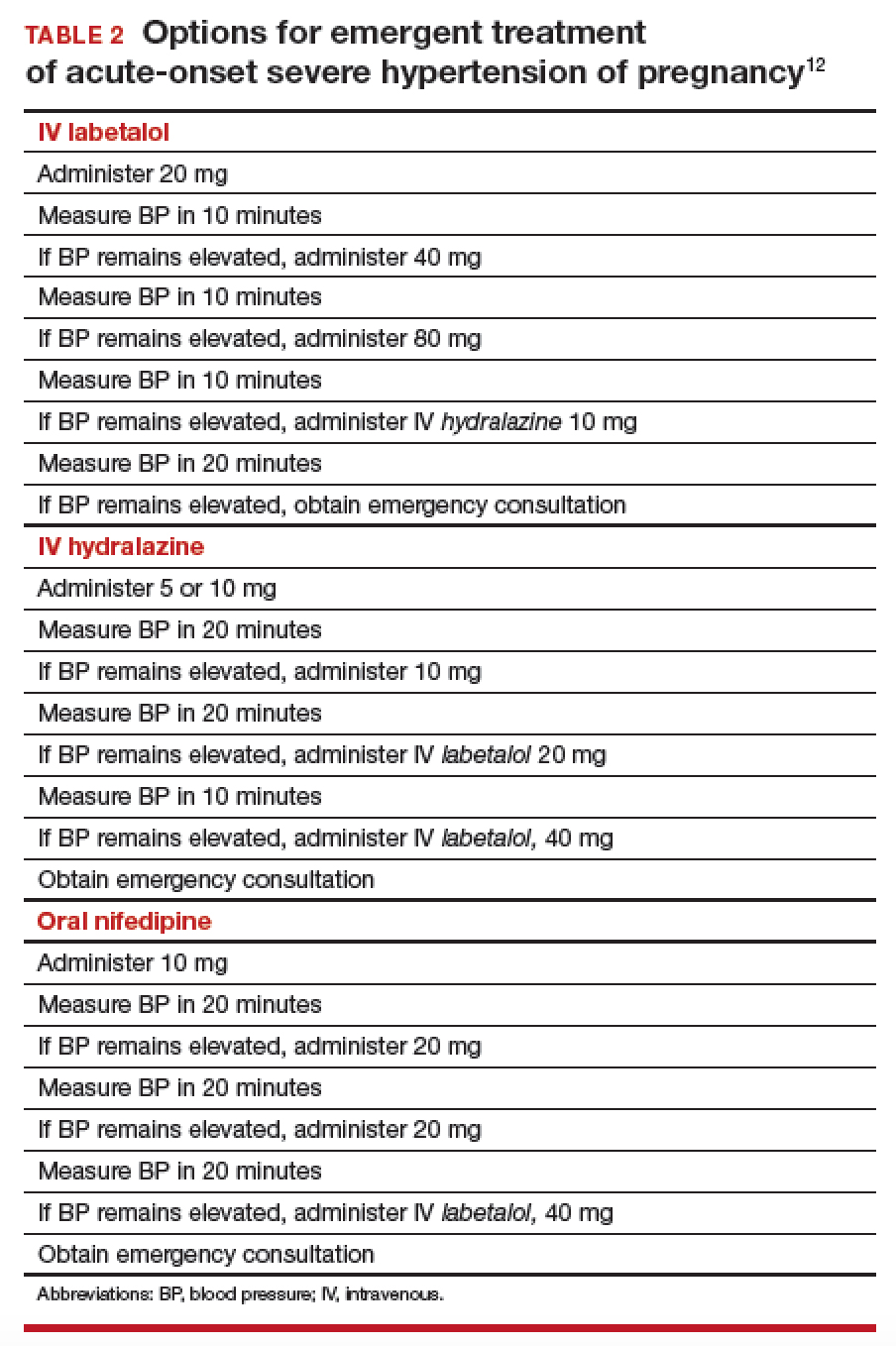

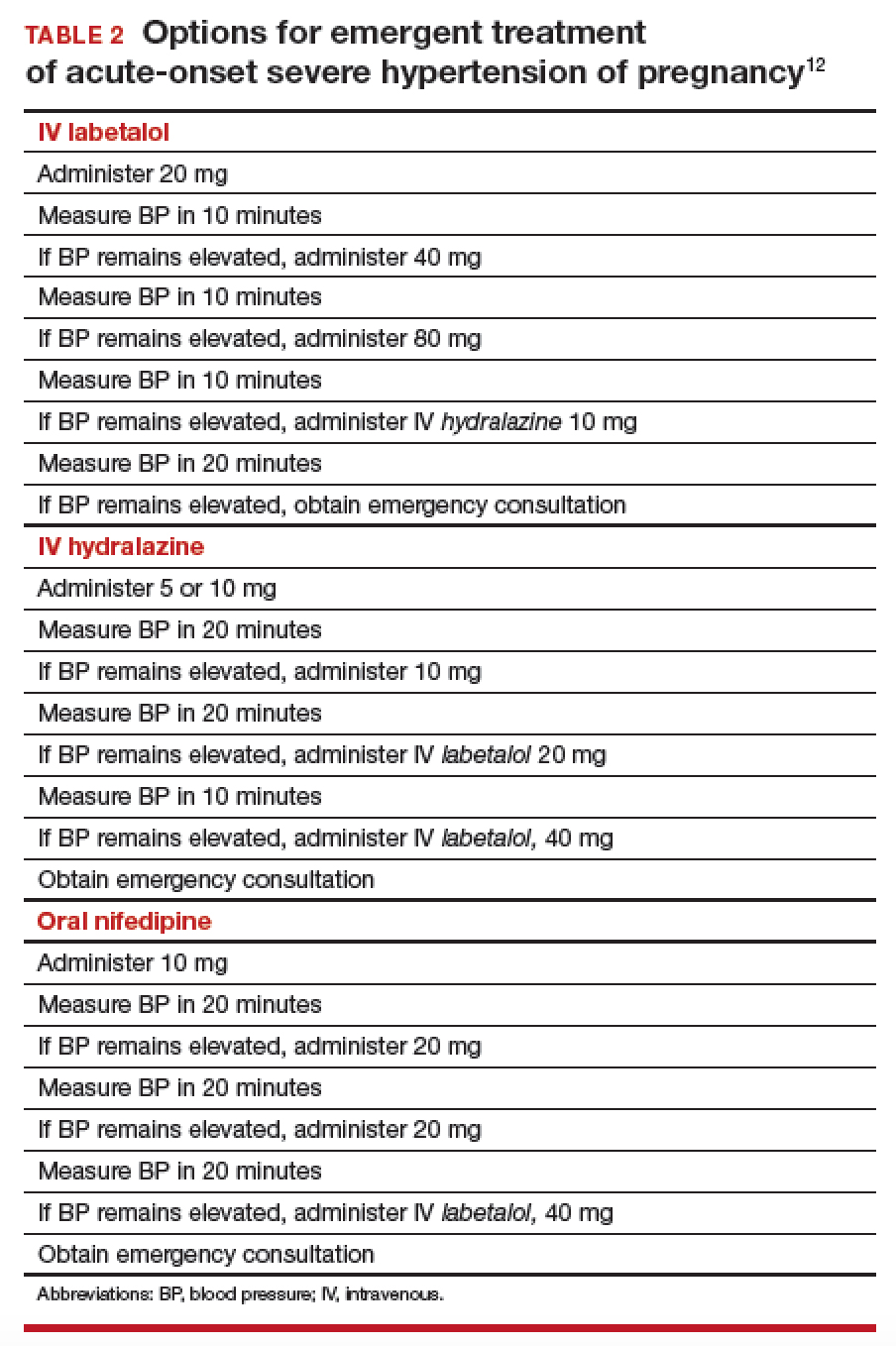

Acute BP control with intravenous (IV) labetalol or hydralazine or oral nifedipine is recommended when a patient has a hypertensive emergency, defined as acute-onset severe hypertension that persists for ≥ 15 minutes (TABLE 2).12 The goal of management is not to completely normalize BP but to lower BP to the range of 140 to 155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90 to 105 mm Hg (diastolic). Of all proposed interventions, these agents are likely the most effective in preventing a maternal cerebrovascular or cardiovascular event. (Note: Labetalol is contraindicated in patients with severe asthma and in the setting of acute cocaine or methamphetamine intoxication. Hydralazine can cause tachycardia.)13,14

Once a diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features or superimposed preeclampsia with severe features is made, the patient should remain hospitalized until delivery. If either of these diagnoses is made at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation, there is no reason to prolong pregnancy. Rather, the patient should be given prophylactic magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures and delivery should be accomplished.15,16 Earlier than 36 6/7 weeks of gestation, consider a late preterm course of corticosteroids; however, do not delay delivery in this situation.17

Planning for delivery

Route of delivery depends on customary obstetric indications. Before 34 weeks of gestation, corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and prolonging the pregnancy until 34 weeks of gestation are recommended. If, at any time, maternal or fetal condition deteriorates, delivery should be accomplished regardless of gestational age. If the patient is unwilling to accept the risks of expectant management of preeclampsia with severe features remote from term, delivery is indicated.18,19 If delivery is not likely to occur, magnesium sulfate can be discontinued after the patient has received a second dose of corticosteroids, with the plan to resume magnesium sulfate if she develops signs of worsening preeclampsia or eclampsia, or once the plan for delivery is made.

In patients who have either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia without severe features, the recommendation is to accomplish delivery no later than 37 weeks of gestation. While the patient is being expectantly managed, close maternal and fetal surveillance are necessary, comprising serial assessment of maternal symptoms and fetal movement; serial BP measurement (twice weekly); and weekly measurement of the platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes. At 34 weeks of gestation, conventional antepartum testing should begin. Again, if there is deterioration of the maternal or fetal condition, the patient should be hospitalized and delivery should be accomplished according to the recommendations above.3

Seizure management

If a patient has a tonic–clonic seizure consistent with eclampsia, management should be as follows:

- Preserve the airway and immediately tilt the head forward to prevent aspiration.

- If the patient is not receiving magnesium sulfate, immediately administer a loading dose of 4-6 g IV or 10 mg intramuscularly if IV access has not been established.20

- If the patient is already receiving magnesium sulfate, administer a loading dose of 2 g IV over 5 minutes.

- If the patient continues to have seizure activity, administer anticonvulsant medication(lorazepam, diazepam, midazolam, or phenytoin).

Eclamptic seizures are usually self-limited, lasting no longer than 1 or 2 minutes. Regrettably, these seizures are unpredictable and contribute significantly to maternal morbidity and mortality.21,22 A maternal seizure causes a significant interruption in the oxygen pathway to the fetus, with resultant late decelerations, prolonged decelerations, or bradycardia.

Resist the temptation to perform emergent cesarean delivery when eclamptic seizure occurs; rather, allow time for fetal recovery and then proceed with delivery in a controlled fashion. In many circumstances, the patient can undergo vaginal delivery after an eclamptic seizure. Keep in mind that the differential diagnosis of new-onset seizure in pregnancy includes cerebral pathology, such as a bleeding arteriovenous malformation or ruptured aneurysm. Therefore, brain-imaging studies might be indicated, especially in patients who have focal neurologic deficits, or who have seizures either while receiving magnesium sulfate or 48 to 72 hours after delivery.

Preeclampsia postpartum

More recent studies have demonstrated that preeclampsia can be exacerbated after delivery or might even present initially postpartum.23,24 In all women in whom gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or superimposed preeclampsia is diagnosed, therefore, recommendations are that BP be monitored in the hospital or on an outpatient basis for at least 72 hours postpartum and again 7 to 10 days after delivery. For all women postpartum, the recommendation is that discharge instructions 1) include information about signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and 2) emphasize the importance of promptly reporting such developments to providers.25 Remember: Sequelae of preeclampsia have been reported as late as 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.

Magnesium sulfate is recommended when a patient presents postpartum with new-onset hypertension associated with headache or blurred vision, or with preeclampsia with severe hypertension. Because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be associated with elevated BP, these medications should be replaced by other analgesics in women with hypertension that persists for more than 1 day postpartum.

Prevention of preeclampsia

Given the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications associated with preeclampsia, a number of studies have sought to determine ways in which this condition can be prevented. Currently, although no interventions appear to prevent preeclampsia in all patients, significant strides have been made in prevention for high-risk patients. Specifically, beginning low-dosage aspirin (most commonly, 81 mg/d, beginning at less than 16 weeks of gestation) has been shown to mitigate—although not eliminate—risk in patients with a history of preeclampsia and those who have chronic hypertension, multifetal gestation, pregestational diabetes, renal disease, SLE, or antiphospholipid syndrome.26,27Aspirin appears to act by preferentially blocking production of thromboxane, thus reducing the vasoconstrictive properties of this hormone.

Summing up

Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for mother, fetus, and newborn. Preeclampsia, specifically, is recognized as a dynamic and progressive disease that has the potential to involve multiple organ systems, might present for the first time after delivery, and might be associated with long-term risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism.28,29

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199:133.e1-e8.

- Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1299-1306.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Wheeler TL 2nd, Blackhurst DW, Dellinger EH, Ramsey PS. Usage of spot urine protein to creatinine ratios in the evaluation of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:465.e1-e4.

- Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LL. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. CG107, August 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg107. Accessed August 27, 2018. Last updated January 2011.

- Spong CY, Mercer BM, D'Alton M, et al. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:323-333.

- Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):369-377.

- Dugoff L; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. First- and second-trimester maternal serum markers or aneuploidy and adverse obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1052-1061.

- Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The "great obstetrical syndromes" are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:193-201.

- Huppertz B. Placental origins of preeclampsia: challenging the current hypothesis. Hypertension. 2008;51:970-975.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice; El-Sayed YY, Borders AE. Committee Opinion Number 692. Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period; April 2017. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/co692.pdf?dmc=1. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Hollander JE. The management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart. 2000;83:627-633.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877-1890.

- Sibai BM. Magnesium sulfate prophylaxis in preeclampsia: lessons learned from recent trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1520-1526.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1311-1320.

- Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:191-198.

- Norwitz E, Funai E. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: hope for the best, but expect the worst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:209-212.

- Gordon R, Magee LA, Payne B, et al. Magnesium sulphate for the management of preeclampsia and eclampsia in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of tested dosing regimens. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(2):154-163.

- Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402-410.

- Liu S, Joseph KS, Liston, RM, et al; Maternal Health Study Group of Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada). Incidence, risk factors, and associated complications of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):987-994.