User login

Does newly discovered vasoactive peptide ELABELA reveal essential mechanisms for preeclampsia development?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Preeclampsia is a disorder of impaired placentation. ELABELA (ELA) encodes an endogenous ligand for the apelin receptor and is detected in preimplantation human blastocysts and in 2 organs in adults: the placenta and kidney. Recently, an international team of researchers described their study findings on ELA and its role in placental vascular development and preeclampsia in mice.

Details of the study

To delineate the contribution of ELA to mammalian development, Ho and colleagues generated Ela knockout mice. The investigators showed that during development, the ELA protein is first detected in the early placenta and becomes abundant later in placenta formation. They also demonstrated that ELA is a pregnancy hormone that circulates in the blood of pregnant, but not nonpregnant, mice.

Placental structure. The Ela knockout mice had placentas that demonstrated thin labyrinths, with poor vascularization, increased apoptosis, and reduced proliferation. Further, RNA analysis of ELA-lacking placentas revealed a gene expression profile indicative of hypoxia, including the upregulation of certain genes involved in blood vessel building. Placental vessels showed overall stunted architecture characterized by little or no extension and branching of angiogenic sprouts and impaired formation of the adequate labyrinth network required for proper perfusion in the placenta.

Given these gene expression findings and the fact that placental and vascular abnormalities have long been suspected to underlie preeclampsia, the investigators sought to determine if ELA-lacking mice exhibit preeclampsia. Evidence indicated they do.

Indicators of preeclampsia. Pregnant ELA-lacking mice had significantly higher levels of proteinuria and significantly higher blood pressure than either pregnant wild-type mice or nonpregnant ELA-lacking mice. Further, at the end of pregnancy, histology and transmission electron microscopy of kidney glomerular sections from ELA-lacking pregnant mice revealed signs of endotheliosis, a unique renal pathology that is also observed in women with preeclampsia. Pups of ELA-lacking mothers tended to weigh less than those of wild-type mothers, a situation that may be similar to the fetal intrauterine growth restriction commonly seen in women with preeclampsia.

Angiogenic factors. The authors then looked at levels of angiogenic proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia to determine if ELA is upstream. They found that ELA-lacking mice placentas had increased levels of sFlt1, Vegfa, and Plgf mRNA; these transcriptional changes, however, did not translate into significantly elevated plasma levels of the respective proteins. Thus, these findings indicate that ELA acts independently of, and possibly earlier than, angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Experimental treatment. The authors further showed that infusing recombinant ELA protein could alleviate symptoms of preeclampsia in mice. Injection of ELA protein in ELA-lacking mice led to reduction of blood pressure, reversal of glomerular endotheliosis, and rescue of fetal growth restriction.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This animal study contributes compelling molecular evidence of ELA’s role in mammalian placental development and angiogenesis, revealing that ELA deficiency leads to preeclampsia and placental abnormalities in pregnant mice. How ELA acts in humans and human pregnancy, however, has yet to be explored.

-- Sarosh Rana, MD, MPH

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Preeclampsia is a disorder of impaired placentation. ELABELA (ELA) encodes an endogenous ligand for the apelin receptor and is detected in preimplantation human blastocysts and in 2 organs in adults: the placenta and kidney. Recently, an international team of researchers described their study findings on ELA and its role in placental vascular development and preeclampsia in mice.

Details of the study

To delineate the contribution of ELA to mammalian development, Ho and colleagues generated Ela knockout mice. The investigators showed that during development, the ELA protein is first detected in the early placenta and becomes abundant later in placenta formation. They also demonstrated that ELA is a pregnancy hormone that circulates in the blood of pregnant, but not nonpregnant, mice.

Placental structure. The Ela knockout mice had placentas that demonstrated thin labyrinths, with poor vascularization, increased apoptosis, and reduced proliferation. Further, RNA analysis of ELA-lacking placentas revealed a gene expression profile indicative of hypoxia, including the upregulation of certain genes involved in blood vessel building. Placental vessels showed overall stunted architecture characterized by little or no extension and branching of angiogenic sprouts and impaired formation of the adequate labyrinth network required for proper perfusion in the placenta.

Given these gene expression findings and the fact that placental and vascular abnormalities have long been suspected to underlie preeclampsia, the investigators sought to determine if ELA-lacking mice exhibit preeclampsia. Evidence indicated they do.

Indicators of preeclampsia. Pregnant ELA-lacking mice had significantly higher levels of proteinuria and significantly higher blood pressure than either pregnant wild-type mice or nonpregnant ELA-lacking mice. Further, at the end of pregnancy, histology and transmission electron microscopy of kidney glomerular sections from ELA-lacking pregnant mice revealed signs of endotheliosis, a unique renal pathology that is also observed in women with preeclampsia. Pups of ELA-lacking mothers tended to weigh less than those of wild-type mothers, a situation that may be similar to the fetal intrauterine growth restriction commonly seen in women with preeclampsia.

Angiogenic factors. The authors then looked at levels of angiogenic proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia to determine if ELA is upstream. They found that ELA-lacking mice placentas had increased levels of sFlt1, Vegfa, and Plgf mRNA; these transcriptional changes, however, did not translate into significantly elevated plasma levels of the respective proteins. Thus, these findings indicate that ELA acts independently of, and possibly earlier than, angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Experimental treatment. The authors further showed that infusing recombinant ELA protein could alleviate symptoms of preeclampsia in mice. Injection of ELA protein in ELA-lacking mice led to reduction of blood pressure, reversal of glomerular endotheliosis, and rescue of fetal growth restriction.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This animal study contributes compelling molecular evidence of ELA’s role in mammalian placental development and angiogenesis, revealing that ELA deficiency leads to preeclampsia and placental abnormalities in pregnant mice. How ELA acts in humans and human pregnancy, however, has yet to be explored.

-- Sarosh Rana, MD, MPH

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Preeclampsia is a disorder of impaired placentation. ELABELA (ELA) encodes an endogenous ligand for the apelin receptor and is detected in preimplantation human blastocysts and in 2 organs in adults: the placenta and kidney. Recently, an international team of researchers described their study findings on ELA and its role in placental vascular development and preeclampsia in mice.

Details of the study

To delineate the contribution of ELA to mammalian development, Ho and colleagues generated Ela knockout mice. The investigators showed that during development, the ELA protein is first detected in the early placenta and becomes abundant later in placenta formation. They also demonstrated that ELA is a pregnancy hormone that circulates in the blood of pregnant, but not nonpregnant, mice.

Placental structure. The Ela knockout mice had placentas that demonstrated thin labyrinths, with poor vascularization, increased apoptosis, and reduced proliferation. Further, RNA analysis of ELA-lacking placentas revealed a gene expression profile indicative of hypoxia, including the upregulation of certain genes involved in blood vessel building. Placental vessels showed overall stunted architecture characterized by little or no extension and branching of angiogenic sprouts and impaired formation of the adequate labyrinth network required for proper perfusion in the placenta.

Given these gene expression findings and the fact that placental and vascular abnormalities have long been suspected to underlie preeclampsia, the investigators sought to determine if ELA-lacking mice exhibit preeclampsia. Evidence indicated they do.

Indicators of preeclampsia. Pregnant ELA-lacking mice had significantly higher levels of proteinuria and significantly higher blood pressure than either pregnant wild-type mice or nonpregnant ELA-lacking mice. Further, at the end of pregnancy, histology and transmission electron microscopy of kidney glomerular sections from ELA-lacking pregnant mice revealed signs of endotheliosis, a unique renal pathology that is also observed in women with preeclampsia. Pups of ELA-lacking mothers tended to weigh less than those of wild-type mothers, a situation that may be similar to the fetal intrauterine growth restriction commonly seen in women with preeclampsia.

Angiogenic factors. The authors then looked at levels of angiogenic proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia to determine if ELA is upstream. They found that ELA-lacking mice placentas had increased levels of sFlt1, Vegfa, and Plgf mRNA; these transcriptional changes, however, did not translate into significantly elevated plasma levels of the respective proteins. Thus, these findings indicate that ELA acts independently of, and possibly earlier than, angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Experimental treatment. The authors further showed that infusing recombinant ELA protein could alleviate symptoms of preeclampsia in mice. Injection of ELA protein in ELA-lacking mice led to reduction of blood pressure, reversal of glomerular endotheliosis, and rescue of fetal growth restriction.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This animal study contributes compelling molecular evidence of ELA’s role in mammalian placental development and angiogenesis, revealing that ELA deficiency leads to preeclampsia and placental abnormalities in pregnant mice. How ELA acts in humans and human pregnancy, however, has yet to be explored.

-- Sarosh Rana, MD, MPH

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Early births stress dads too

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.

“We have to understand that these fathers are now 6 weeks at home with a healthy infant, but they are still experiencing the stress of being exposed to this risk of preterm birth,” Ms. Schulze said.

By 6 months, depression had eased off in fathers whose infants made it to term; at 5%, it was similar to the rate in the control group fathers (4%) and the general population. But many fathers whose babies came early still were experiencing depression (12%).

Ms. Schulze then compared the fathers’ experience to that of the mothers. At baseline, women at risk of preterm birth had exactly the same rate of depression as their partners (35%). However, depression also was elevated among women in the control group (18%). The background rate for depression among German women is 10%, Ms. Schulze said.

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, the timing of birth did not seem to matter as much to the mothers. Depression rates were similarly elevated in those who had a preterm birth and those who did not (25%, 28%). Both were significantly higher than the 17% rate in the control group.

At 6 months, things were leveling out some for these mothers, with depression present in 10% of the preterm birth group, 19% of the full-term birth group, and 13% of the control group.

“Men seem to suffer just as much stress from this experience as women do, although perhaps in a different trajectory,” Ms. Schulze said. “Although there may be different contributing factors, we believe that the psychological care offered to mothers at risk of preterm birth should also be extended to fathers.”

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.

“We have to understand that these fathers are now 6 weeks at home with a healthy infant, but they are still experiencing the stress of being exposed to this risk of preterm birth,” Ms. Schulze said.

By 6 months, depression had eased off in fathers whose infants made it to term; at 5%, it was similar to the rate in the control group fathers (4%) and the general population. But many fathers whose babies came early still were experiencing depression (12%).

Ms. Schulze then compared the fathers’ experience to that of the mothers. At baseline, women at risk of preterm birth had exactly the same rate of depression as their partners (35%). However, depression also was elevated among women in the control group (18%). The background rate for depression among German women is 10%, Ms. Schulze said.

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, the timing of birth did not seem to matter as much to the mothers. Depression rates were similarly elevated in those who had a preterm birth and those who did not (25%, 28%). Both were significantly higher than the 17% rate in the control group.

At 6 months, things were leveling out some for these mothers, with depression present in 10% of the preterm birth group, 19% of the full-term birth group, and 13% of the control group.

“Men seem to suffer just as much stress from this experience as women do, although perhaps in a different trajectory,” Ms. Schulze said. “Although there may be different contributing factors, we believe that the psychological care offered to mothers at risk of preterm birth should also be extended to fathers.”

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.

“We have to understand that these fathers are now 6 weeks at home with a healthy infant, but they are still experiencing the stress of being exposed to this risk of preterm birth,” Ms. Schulze said.

By 6 months, depression had eased off in fathers whose infants made it to term; at 5%, it was similar to the rate in the control group fathers (4%) and the general population. But many fathers whose babies came early still were experiencing depression (12%).

Ms. Schulze then compared the fathers’ experience to that of the mothers. At baseline, women at risk of preterm birth had exactly the same rate of depression as their partners (35%). However, depression also was elevated among women in the control group (18%). The background rate for depression among German women is 10%, Ms. Schulze said.

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, the timing of birth did not seem to matter as much to the mothers. Depression rates were similarly elevated in those who had a preterm birth and those who did not (25%, 28%). Both were significantly higher than the 17% rate in the control group.

At 6 months, things were leveling out some for these mothers, with depression present in 10% of the preterm birth group, 19% of the full-term birth group, and 13% of the control group.

“Men seem to suffer just as much stress from this experience as women do, although perhaps in a different trajectory,” Ms. Schulze said. “Although there may be different contributing factors, we believe that the psychological care offered to mothers at risk of preterm birth should also be extended to fathers.”

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT WPA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Depression developed in 35% of men whose wives were admitted to the hospital for imminent preterm birth; elevated depression rates lingered for up to 6 months in these fathers.

Data source: The prospective study comprised 69 couples admitted for preterm birth risk, and 49 control couples.

Disclosures: Ms. Schulze had no financial disclosures.

Intensive exercise didn’t improve glycemic control for obese pregnant women

An intensive exercise intervention for obese pregnant women did not improve maternal glycemia, but did attenuate excessive gestational weight gain, according to the a single-center, randomized controlled trial published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Healthy Eating, Exercise and Lifestyle Trial, conducted from November 2013 through April 2016 at the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital in Dublin, randomized 88 pregnant women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater at their first prenatal visit to either a medically supervised exercise program or to the control group. The intervention consisted of 50-60 minutes of exercise at least once per week, including resistance or weights and aerobic exercises (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1001-10).

However, excessive gestational weight gain at 36 weeks’ gestation (greater than 9.1 kg) was lower in the exercise group at 22.2%, compared with 43.2% in the control group (P less than .05), Niamh Daly of Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital and her coauthors reported.

“Our study may have failed to improve maternal glycemia because the ideal time to begin such a program could be before pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “Pregnant women who are obese, however, should be advised to exercise because it attenuates excessive gestational weight gain.”

The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

An intensive exercise intervention for obese pregnant women did not improve maternal glycemia, but did attenuate excessive gestational weight gain, according to the a single-center, randomized controlled trial published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Healthy Eating, Exercise and Lifestyle Trial, conducted from November 2013 through April 2016 at the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital in Dublin, randomized 88 pregnant women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater at their first prenatal visit to either a medically supervised exercise program or to the control group. The intervention consisted of 50-60 minutes of exercise at least once per week, including resistance or weights and aerobic exercises (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1001-10).

However, excessive gestational weight gain at 36 weeks’ gestation (greater than 9.1 kg) was lower in the exercise group at 22.2%, compared with 43.2% in the control group (P less than .05), Niamh Daly of Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital and her coauthors reported.

“Our study may have failed to improve maternal glycemia because the ideal time to begin such a program could be before pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “Pregnant women who are obese, however, should be advised to exercise because it attenuates excessive gestational weight gain.”

The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

An intensive exercise intervention for obese pregnant women did not improve maternal glycemia, but did attenuate excessive gestational weight gain, according to the a single-center, randomized controlled trial published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Healthy Eating, Exercise and Lifestyle Trial, conducted from November 2013 through April 2016 at the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital in Dublin, randomized 88 pregnant women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater at their first prenatal visit to either a medically supervised exercise program or to the control group. The intervention consisted of 50-60 minutes of exercise at least once per week, including resistance or weights and aerobic exercises (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1001-10).

However, excessive gestational weight gain at 36 weeks’ gestation (greater than 9.1 kg) was lower in the exercise group at 22.2%, compared with 43.2% in the control group (P less than .05), Niamh Daly of Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital and her coauthors reported.

“Our study may have failed to improve maternal glycemia because the ideal time to begin such a program could be before pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “Pregnant women who are obese, however, should be advised to exercise because it attenuates excessive gestational weight gain.”

The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was no difference in mean fasting plasma glucose between the control group (90.0 plus or minus 9.0 mg/dL) and the exercise group (93.6 plus or minus 7.2 mg/dL) at 24-28 weeks’ gestation (P = .13).

Data source: A single-center, randomized controlled trial of 88 pregnant women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Tdap during pregnancy, or before, offers infants pertussis protection

during the early months of life, according to Tami H. Skoff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

In an analysis of 240 infants younger than 2 months with pertussis cough onset between 2011 and 2015 and 535 control infants, 57% of case mothers and 67% of control mothers had at least one valid Tdap dose; 13% of vaccinated case mothers and 14% of vaccinated control mothers had more than one valid dose of Tdap reported.

Of Tdap doses received during pregnancy in 22 cases and 117 controls, 77% were received during the third trimester, most during the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended 27-36 weeks of gestation. Of the Tdap doses received before pregnancy in mothers of 24 cases and 67 controls, 25% of the case mothers and 67% of the control mothers received Tdap 2 or fewer years before pregnancy.

The effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy was 78%, and effectiveness during the first or second trimester was 64%. Effectiveness of Tdap given 2 or fewer years before pregnancy was 83%. This study was not powered to determine a difference if the vaccine was administered in the ACIP-recommended time period during the third trimester.

A reported 49% of U.S. pregnant women received Tdap during the 2015-2016 flu season, an increase of 22% from the 2013-2014 season, according to a CDC Internet panel survey.

“While maternal immunization during pregnancy will help bridge the gap until next-generation pertussis vaccines are licensed and available for use, this highly effective strategy will likely remain an integral component of pertussis prevention and control, even in the setting of new vaccines,” the investigators said.

Read more in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix724).

during the early months of life, according to Tami H. Skoff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

In an analysis of 240 infants younger than 2 months with pertussis cough onset between 2011 and 2015 and 535 control infants, 57% of case mothers and 67% of control mothers had at least one valid Tdap dose; 13% of vaccinated case mothers and 14% of vaccinated control mothers had more than one valid dose of Tdap reported.

Of Tdap doses received during pregnancy in 22 cases and 117 controls, 77% were received during the third trimester, most during the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended 27-36 weeks of gestation. Of the Tdap doses received before pregnancy in mothers of 24 cases and 67 controls, 25% of the case mothers and 67% of the control mothers received Tdap 2 or fewer years before pregnancy.

The effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy was 78%, and effectiveness during the first or second trimester was 64%. Effectiveness of Tdap given 2 or fewer years before pregnancy was 83%. This study was not powered to determine a difference if the vaccine was administered in the ACIP-recommended time period during the third trimester.

A reported 49% of U.S. pregnant women received Tdap during the 2015-2016 flu season, an increase of 22% from the 2013-2014 season, according to a CDC Internet panel survey.

“While maternal immunization during pregnancy will help bridge the gap until next-generation pertussis vaccines are licensed and available for use, this highly effective strategy will likely remain an integral component of pertussis prevention and control, even in the setting of new vaccines,” the investigators said.

Read more in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix724).

during the early months of life, according to Tami H. Skoff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

In an analysis of 240 infants younger than 2 months with pertussis cough onset between 2011 and 2015 and 535 control infants, 57% of case mothers and 67% of control mothers had at least one valid Tdap dose; 13% of vaccinated case mothers and 14% of vaccinated control mothers had more than one valid dose of Tdap reported.

Of Tdap doses received during pregnancy in 22 cases and 117 controls, 77% were received during the third trimester, most during the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended 27-36 weeks of gestation. Of the Tdap doses received before pregnancy in mothers of 24 cases and 67 controls, 25% of the case mothers and 67% of the control mothers received Tdap 2 or fewer years before pregnancy.

The effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy was 78%, and effectiveness during the first or second trimester was 64%. Effectiveness of Tdap given 2 or fewer years before pregnancy was 83%. This study was not powered to determine a difference if the vaccine was administered in the ACIP-recommended time period during the third trimester.

A reported 49% of U.S. pregnant women received Tdap during the 2015-2016 flu season, an increase of 22% from the 2013-2014 season, according to a CDC Internet panel survey.

“While maternal immunization during pregnancy will help bridge the gap until next-generation pertussis vaccines are licensed and available for use, this highly effective strategy will likely remain an integral component of pertussis prevention and control, even in the setting of new vaccines,” the investigators said.

Read more in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix724).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

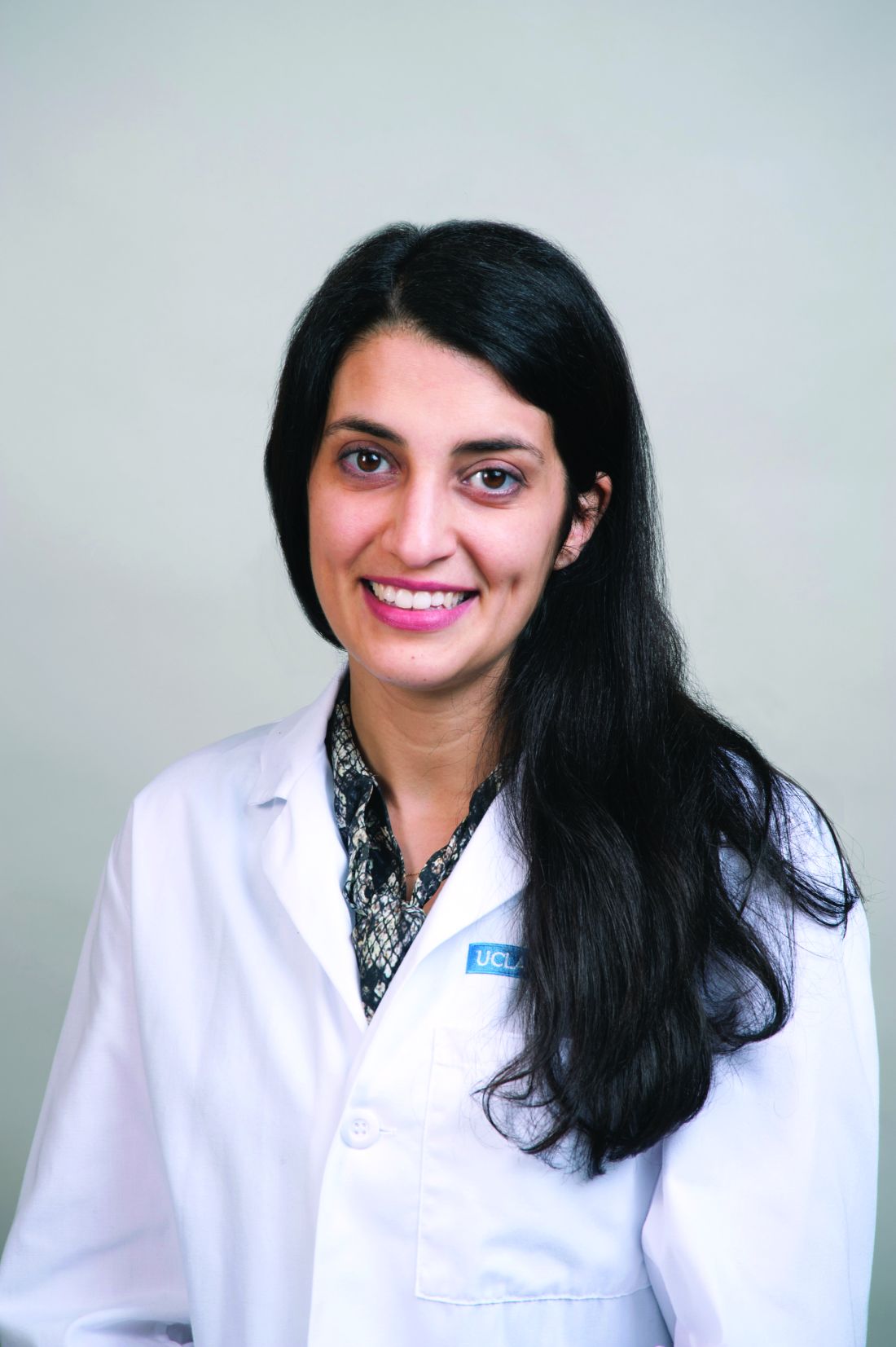

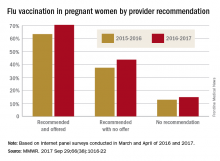

Should we stop administering the influenza vaccine to pregnant women?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Influenza can be a serious, even life-threatening infection, especially in pregnant women and their newborn infants.1 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) strongly recommend that all pregnant women receive the inactivated influenza vaccine at the start of each flu season, regardless of trimester of exposure.

The most widely-used vaccine in the United States is the inactivated quadrivalent vaccine, which is intended for intramuscular administration in a single dose. The 2017-2018 version of this vaccine includes 2 influenza A antigens and 2 influenza B antigens. The first of the A antigens differs from last year's vaccine. The other 3 antigens are the same as in the 2016-2017 vaccine:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus

- A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagota)

Several recent reports in large, diverse populations2-5 have demonstrated that the vaccine does not increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, preterm delivery, or congenital anomalies. Therefore, a recent report by Donahue and colleagues6 is surprising and is certainly worthy of our attention.

Related article:

Does influenza immunization during pregnancy confer flu protection to newborns?

Details of the study

Donahue and colleagues, experienced investigators, were tasked by the CDC with using information from the Vaccine Safety Datalink to specifically assess the safety of the influenza vaccine when administered early in pregnancy. They evaluated 485 women who had experienced a spontaneous abortion in 1 of 2 time periods: September 1, 2010 to April 28, 2011 and September 1, 2011 to April 28, 2012. These women were matched by last menstrual period with controls who subsequently had a liveborn infant or stillbirth at greater than 20 weeks of gestation. The exposure of interest was receipt of the monovalent H1N1 vaccine (H1N1pdm09), the inactivated trivalent vaccine (A/California/7/2009 H1N1 pdm09-like, A/Perth/16/2009 H3N2-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like), or both in the 28 days immediately preceding the spontaneous abortion. The investigators also considered 2 other windows of exposure: 29 to 56 days and greater than 56 days. In addition, they controlled for the following potential confounding variables: maternal age, smoking history, presence of type 1 or 2 diabetes, prepregnancy BMI, and previous health care utilization.

Cases were significantly older than controls. They also were more likely to be African-American, to have had a history of greater than or equal to 2 spontaneous abortions, and to have smoked during pregnancy. The median gestational age at the time of spontaneous abortion was 7 weeks. Overall, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of spontaneous abortion within the 1- to 28-day window was 2.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-3.6). There was not even a weak association in the other 2 windows of exposure. However, in women who received the pH1N1 vaccine in the previous flu season, the aOR was 7.7 (95% CI, 2.2-27.3). When women who had experienced 2 or more spontaneous abortions were excluded, the aOR remained significantly elevated at 6.5 (95% CI, 1.7-24.3). The aOR was 1.3 (95% CI, 0.7-2.7) in women who were not vaccinated with the pH1N1 vaccine in the previous flu season.

Donahue and colleagues6 offered several possible explanations for their observations. They noted that the pH1N1 vaccine seemed to cause at least mild increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly in pregnant compared with nonpregnant women. In addition, infection with the pH1N1 virus or vaccination with the pH1N1 vaccine induces an increase in T helper type-1 cells, which exert a pro-inflammatory effect. Excessive inflammation, in turn, may cause spontaneous abortion.

Related article:

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Study limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, the vaccine used in the investigation is not identical to the one used most commonly today. Second, although the number of women with spontaneous abortions is relatively large, the number who received the pH1N1-containing vaccine in consecutive years was relatively small. Third, this case-control study was able to estimate an odds ratio for the adverse outcome, but it could not prove causation, nor could it provide a precise estimate of absolute risk for a spontaneous miscarriage following the influenza vaccine. Finally, the authors, understandably,were unable to control for all the myriad factors that may increase the risk for spontaneous abortion.

With these limitations in mind, I certainly concur with the recommendations of the CDC and ACOG7 to continue our practice of routinely offering the influenza vaccine to virtually all pregnant women at the beginning of the flu season. For the vast majority of patients, the benefit of vaccination for both mother and baby outweighs the risk of an adverse effect. Traditionally, allergy to any of the vaccine components, principally egg protein and/or mercury, was considered a contraindication to vaccination. However, one trivalent vaccine preparation (Flublok, Protein Sciences Corporation) is now available that does not contain egg protein, and 3 trivalent preparations and at least 6 quadrivalent preparations are available that do not contain thimerosal (mercury). Therefore, allergy should rarely be a contraindication to vaccination.

In order to exercise an abundance of caution, I will not offer this vaccination in the first trimester to women who appear to be at increased risk for early pregnancy loss (women with spontaneous bleeding or a prior history of early loss). In these individuals, I will defer vaccination until the second trimester. I will also eagerly await the results of another CDC-sponsored investigation designed to evaluate the risks of spontaneous abortion in women who were vaccinated consecutively in the 2012–2013, 2013–2014, and 2014–2015 influenza seasons.6

-- Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA; California Pandemic (H1N1) Working Group. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):27–35.

- Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Pitsa CE, Falagas ME. Maternal influenza vaccination and risk for congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1075–1084.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Naleway A, Lee G, Nordin JD; Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(3):659–667.

- Sheffield JS, Greer LG, Rogers VL, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination in the first trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):532–537.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 468: influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):1006–1007.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010-11 and 2011-12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314–5322.

- Flu vaccination and possible safety signal. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html. Updated September 13, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Influenza can be a serious, even life-threatening infection, especially in pregnant women and their newborn infants.1 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) strongly recommend that all pregnant women receive the inactivated influenza vaccine at the start of each flu season, regardless of trimester of exposure.

The most widely-used vaccine in the United States is the inactivated quadrivalent vaccine, which is intended for intramuscular administration in a single dose. The 2017-2018 version of this vaccine includes 2 influenza A antigens and 2 influenza B antigens. The first of the A antigens differs from last year's vaccine. The other 3 antigens are the same as in the 2016-2017 vaccine:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus

- A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagota)

Several recent reports in large, diverse populations2-5 have demonstrated that the vaccine does not increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, preterm delivery, or congenital anomalies. Therefore, a recent report by Donahue and colleagues6 is surprising and is certainly worthy of our attention.

Related article:

Does influenza immunization during pregnancy confer flu protection to newborns?

Details of the study

Donahue and colleagues, experienced investigators, were tasked by the CDC with using information from the Vaccine Safety Datalink to specifically assess the safety of the influenza vaccine when administered early in pregnancy. They evaluated 485 women who had experienced a spontaneous abortion in 1 of 2 time periods: September 1, 2010 to April 28, 2011 and September 1, 2011 to April 28, 2012. These women were matched by last menstrual period with controls who subsequently had a liveborn infant or stillbirth at greater than 20 weeks of gestation. The exposure of interest was receipt of the monovalent H1N1 vaccine (H1N1pdm09), the inactivated trivalent vaccine (A/California/7/2009 H1N1 pdm09-like, A/Perth/16/2009 H3N2-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like), or both in the 28 days immediately preceding the spontaneous abortion. The investigators also considered 2 other windows of exposure: 29 to 56 days and greater than 56 days. In addition, they controlled for the following potential confounding variables: maternal age, smoking history, presence of type 1 or 2 diabetes, prepregnancy BMI, and previous health care utilization.

Cases were significantly older than controls. They also were more likely to be African-American, to have had a history of greater than or equal to 2 spontaneous abortions, and to have smoked during pregnancy. The median gestational age at the time of spontaneous abortion was 7 weeks. Overall, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of spontaneous abortion within the 1- to 28-day window was 2.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-3.6). There was not even a weak association in the other 2 windows of exposure. However, in women who received the pH1N1 vaccine in the previous flu season, the aOR was 7.7 (95% CI, 2.2-27.3). When women who had experienced 2 or more spontaneous abortions were excluded, the aOR remained significantly elevated at 6.5 (95% CI, 1.7-24.3). The aOR was 1.3 (95% CI, 0.7-2.7) in women who were not vaccinated with the pH1N1 vaccine in the previous flu season.

Donahue and colleagues6 offered several possible explanations for their observations. They noted that the pH1N1 vaccine seemed to cause at least mild increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly in pregnant compared with nonpregnant women. In addition, infection with the pH1N1 virus or vaccination with the pH1N1 vaccine induces an increase in T helper type-1 cells, which exert a pro-inflammatory effect. Excessive inflammation, in turn, may cause spontaneous abortion.

Related article:

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Study limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, the vaccine used in the investigation is not identical to the one used most commonly today. Second, although the number of women with spontaneous abortions is relatively large, the number who received the pH1N1-containing vaccine in consecutive years was relatively small. Third, this case-control study was able to estimate an odds ratio for the adverse outcome, but it could not prove causation, nor could it provide a precise estimate of absolute risk for a spontaneous miscarriage following the influenza vaccine. Finally, the authors, understandably,were unable to control for all the myriad factors that may increase the risk for spontaneous abortion.

With these limitations in mind, I certainly concur with the recommendations of the CDC and ACOG7 to continue our practice of routinely offering the influenza vaccine to virtually all pregnant women at the beginning of the flu season. For the vast majority of patients, the benefit of vaccination for both mother and baby outweighs the risk of an adverse effect. Traditionally, allergy to any of the vaccine components, principally egg protein and/or mercury, was considered a contraindication to vaccination. However, one trivalent vaccine preparation (Flublok, Protein Sciences Corporation) is now available that does not contain egg protein, and 3 trivalent preparations and at least 6 quadrivalent preparations are available that do not contain thimerosal (mercury). Therefore, allergy should rarely be a contraindication to vaccination.

In order to exercise an abundance of caution, I will not offer this vaccination in the first trimester to women who appear to be at increased risk for early pregnancy loss (women with spontaneous bleeding or a prior history of early loss). In these individuals, I will defer vaccination until the second trimester. I will also eagerly await the results of another CDC-sponsored investigation designed to evaluate the risks of spontaneous abortion in women who were vaccinated consecutively in the 2012–2013, 2013–2014, and 2014–2015 influenza seasons.6

-- Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Influenza can be a serious, even life-threatening infection, especially in pregnant women and their newborn infants.1 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) strongly recommend that all pregnant women receive the inactivated influenza vaccine at the start of each flu season, regardless of trimester of exposure.

The most widely-used vaccine in the United States is the inactivated quadrivalent vaccine, which is intended for intramuscular administration in a single dose. The 2017-2018 version of this vaccine includes 2 influenza A antigens and 2 influenza B antigens. The first of the A antigens differs from last year's vaccine. The other 3 antigens are the same as in the 2016-2017 vaccine:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus

- A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagota)

Several recent reports in large, diverse populations2-5 have demonstrated that the vaccine does not increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, preterm delivery, or congenital anomalies. Therefore, a recent report by Donahue and colleagues6 is surprising and is certainly worthy of our attention.

Related article:

Does influenza immunization during pregnancy confer flu protection to newborns?

Details of the study

Donahue and colleagues, experienced investigators, were tasked by the CDC with using information from the Vaccine Safety Datalink to specifically assess the safety of the influenza vaccine when administered early in pregnancy. They evaluated 485 women who had experienced a spontaneous abortion in 1 of 2 time periods: September 1, 2010 to April 28, 2011 and September 1, 2011 to April 28, 2012. These women were matched by last menstrual period with controls who subsequently had a liveborn infant or stillbirth at greater than 20 weeks of gestation. The exposure of interest was receipt of the monovalent H1N1 vaccine (H1N1pdm09), the inactivated trivalent vaccine (A/California/7/2009 H1N1 pdm09-like, A/Perth/16/2009 H3N2-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like), or both in the 28 days immediately preceding the spontaneous abortion. The investigators also considered 2 other windows of exposure: 29 to 56 days and greater than 56 days. In addition, they controlled for the following potential confounding variables: maternal age, smoking history, presence of type 1 or 2 diabetes, prepregnancy BMI, and previous health care utilization.

Cases were significantly older than controls. They also were more likely to be African-American, to have had a history of greater than or equal to 2 spontaneous abortions, and to have smoked during pregnancy. The median gestational age at the time of spontaneous abortion was 7 weeks. Overall, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of spontaneous abortion within the 1- to 28-day window was 2.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-3.6). There was not even a weak association in the other 2 windows of exposure. However, in women who received the pH1N1 vaccine in the previous flu season, the aOR was 7.7 (95% CI, 2.2-27.3). When women who had experienced 2 or more spontaneous abortions were excluded, the aOR remained significantly elevated at 6.5 (95% CI, 1.7-24.3). The aOR was 1.3 (95% CI, 0.7-2.7) in women who were not vaccinated with the pH1N1 vaccine in the previous flu season.

Donahue and colleagues6 offered several possible explanations for their observations. They noted that the pH1N1 vaccine seemed to cause at least mild increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly in pregnant compared with nonpregnant women. In addition, infection with the pH1N1 virus or vaccination with the pH1N1 vaccine induces an increase in T helper type-1 cells, which exert a pro-inflammatory effect. Excessive inflammation, in turn, may cause spontaneous abortion.

Related article:

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Study limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, the vaccine used in the investigation is not identical to the one used most commonly today. Second, although the number of women with spontaneous abortions is relatively large, the number who received the pH1N1-containing vaccine in consecutive years was relatively small. Third, this case-control study was able to estimate an odds ratio for the adverse outcome, but it could not prove causation, nor could it provide a precise estimate of absolute risk for a spontaneous miscarriage following the influenza vaccine. Finally, the authors, understandably,were unable to control for all the myriad factors that may increase the risk for spontaneous abortion.

With these limitations in mind, I certainly concur with the recommendations of the CDC and ACOG7 to continue our practice of routinely offering the influenza vaccine to virtually all pregnant women at the beginning of the flu season. For the vast majority of patients, the benefit of vaccination for both mother and baby outweighs the risk of an adverse effect. Traditionally, allergy to any of the vaccine components, principally egg protein and/or mercury, was considered a contraindication to vaccination. However, one trivalent vaccine preparation (Flublok, Protein Sciences Corporation) is now available that does not contain egg protein, and 3 trivalent preparations and at least 6 quadrivalent preparations are available that do not contain thimerosal (mercury). Therefore, allergy should rarely be a contraindication to vaccination.

In order to exercise an abundance of caution, I will not offer this vaccination in the first trimester to women who appear to be at increased risk for early pregnancy loss (women with spontaneous bleeding or a prior history of early loss). In these individuals, I will defer vaccination until the second trimester. I will also eagerly await the results of another CDC-sponsored investigation designed to evaluate the risks of spontaneous abortion in women who were vaccinated consecutively in the 2012–2013, 2013–2014, and 2014–2015 influenza seasons.6

-- Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA; California Pandemic (H1N1) Working Group. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):27–35.

- Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Pitsa CE, Falagas ME. Maternal influenza vaccination and risk for congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1075–1084.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Naleway A, Lee G, Nordin JD; Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(3):659–667.

- Sheffield JS, Greer LG, Rogers VL, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination in the first trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):532–537.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 468: influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):1006–1007.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010-11 and 2011-12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314–5322.

- Flu vaccination and possible safety signal. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html. Updated September 13, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA; California Pandemic (H1N1) Working Group. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):27–35.

- Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Pitsa CE, Falagas ME. Maternal influenza vaccination and risk for congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1075–1084.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Naleway A, Lee G, Nordin JD; Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(3):659–667.

- Sheffield JS, Greer LG, Rogers VL, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination in the first trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):532–537.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 468: influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):1006–1007.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010-11 and 2011-12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314–5322.

- Flu vaccination and possible safety signal. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html. Updated September 13, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

HIV antiretroviral resistance can affect more than 10% of pregnant women

SAN DIEGO – HIV antiretroviral resistance can affect more than 10% of pregnant women, even if they are previously treatment naive, results of a case-control study demonstrated.

“Furthermore, if there is an HIV-infected infant who received HIV prophylaxis with zidovudine and nevirapine, the infant may have developed resistance to the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs] class of medications, and timely antiretroviral-resistant testing is an important step prior to choosing an appropriate regimen,” Nava Yeganeh, MD, said in an interview prior to an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In all, 140 infants were HIV infected, and 13 had drug-resistant mutations. Of the 606 women who had sufficient nucleic acid amplification for resistance testing, 63 (10.4%) had drug-resistant mutations against one or more classes of antiretrovirals. “These mothers may have been infected with a drug-resistant strain of HIV, which they then may have passed on to their infants,” Dr. Yeganeh said. “We also found that 3 of the 13 HIV-infected infants with drug-resistant mutations against NNRTIs were born to mothers who did not have a resistant strain of HIV. These three infants likely developed resistance because of the infant prophylaxis they received with nevirapine.”

Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that drug-resistant mutation in mothers was not associated with increased risk of HIV mother-to-child transmission (adjusted odds ratio, 0.79). The only predictors of mother-to-child transmission were log HIV viral load (OR, 1.4) and infant prophylaxis arm with a two-drug regimen (OR, 1.6). In addition, the presence of drug-resistant mutations in mothers who transmitted was strongly associated with presence of drug-resistant mutations in infants (P less than .001).

A key limitation of the trial, Dr. Yeganeh said, was that it was completed in 2011. “Antiretroviral-resistant HIV may be even more common now that antiretrovirals are more available,” she said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – HIV antiretroviral resistance can affect more than 10% of pregnant women, even if they are previously treatment naive, results of a case-control study demonstrated.

“Furthermore, if there is an HIV-infected infant who received HIV prophylaxis with zidovudine and nevirapine, the infant may have developed resistance to the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs] class of medications, and timely antiretroviral-resistant testing is an important step prior to choosing an appropriate regimen,” Nava Yeganeh, MD, said in an interview prior to an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In all, 140 infants were HIV infected, and 13 had drug-resistant mutations. Of the 606 women who had sufficient nucleic acid amplification for resistance testing, 63 (10.4%) had drug-resistant mutations against one or more classes of antiretrovirals. “These mothers may have been infected with a drug-resistant strain of HIV, which they then may have passed on to their infants,” Dr. Yeganeh said. “We also found that 3 of the 13 HIV-infected infants with drug-resistant mutations against NNRTIs were born to mothers who did not have a resistant strain of HIV. These three infants likely developed resistance because of the infant prophylaxis they received with nevirapine.”

Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that drug-resistant mutation in mothers was not associated with increased risk of HIV mother-to-child transmission (adjusted odds ratio, 0.79). The only predictors of mother-to-child transmission were log HIV viral load (OR, 1.4) and infant prophylaxis arm with a two-drug regimen (OR, 1.6). In addition, the presence of drug-resistant mutations in mothers who transmitted was strongly associated with presence of drug-resistant mutations in infants (P less than .001).

A key limitation of the trial, Dr. Yeganeh said, was that it was completed in 2011. “Antiretroviral-resistant HIV may be even more common now that antiretrovirals are more available,” she said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – HIV antiretroviral resistance can affect more than 10% of pregnant women, even if they are previously treatment naive, results of a case-control study demonstrated.

“Furthermore, if there is an HIV-infected infant who received HIV prophylaxis with zidovudine and nevirapine, the infant may have developed resistance to the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs] class of medications, and timely antiretroviral-resistant testing is an important step prior to choosing an appropriate regimen,” Nava Yeganeh, MD, said in an interview prior to an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In all, 140 infants were HIV infected, and 13 had drug-resistant mutations. Of the 606 women who had sufficient nucleic acid amplification for resistance testing, 63 (10.4%) had drug-resistant mutations against one or more classes of antiretrovirals. “These mothers may have been infected with a drug-resistant strain of HIV, which they then may have passed on to their infants,” Dr. Yeganeh said. “We also found that 3 of the 13 HIV-infected infants with drug-resistant mutations against NNRTIs were born to mothers who did not have a resistant strain of HIV. These three infants likely developed resistance because of the infant prophylaxis they received with nevirapine.”

Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that drug-resistant mutation in mothers was not associated with increased risk of HIV mother-to-child transmission (adjusted odds ratio, 0.79). The only predictors of mother-to-child transmission were log HIV viral load (OR, 1.4) and infant prophylaxis arm with a two-drug regimen (OR, 1.6). In addition, the presence of drug-resistant mutations in mothers who transmitted was strongly associated with presence of drug-resistant mutations in infants (P less than .001).

A key limitation of the trial, Dr. Yeganeh said, was that it was completed in 2011. “Antiretroviral-resistant HIV may be even more common now that antiretrovirals are more available,” she said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 606 women who had sufficient nucleic acid amplification for resistance testing, 63 (10.4%) had drug-resistant mutations against one or more classes of antiretrovirals.

Study details: A case-control study of blood samples from 606 HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants.

Disclosures: Dr. Yeganeh reported having no financial disclosures.

Maternal antepartum depression creates bevy of long-term risks in offspring

PARIS – Maternal depression during pregnancy is a common occurrence that can have far-reaching effects in the offspring, according to Tiina Taka-Eilola, MD, of the University of Oulu (Finland).

Indeed, maternal antepartum depression may best be thought of as an adverse environmental factor that exacerbates the impact of any underlying genetic vulnerability to severe mental disorder that may be present in the offspring, she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

At midgestation, back in the mid-1960s, 13.9% of the mothers of the Northern Finland Birth Cohort acknowledged feeling “depressed” or “very depressed,” rates consistent with those reported in other studies using standardized depression assessment instruments. Their offspring, by age 43 years, were 1.6-fold more likely to have a history of a current or past nonpsychotic mood disorder and 2-fold more likely to have had a psychotic mood disorder than did the offspring of mothers free of antepartum depression.

These risks were greatly amplified if either parent experienced a hospital-treated severe mental disorder before, during, or up to 18 years after the pregnancy. Offspring who had both a mother who experienced antepartum depression and a parent with a severe, hospital-treated mental disorder were at 3.9-fold increased risk for being diagnosed with nonpsychotic depression by age 43 years in an analysis adjusted for sex, perinatal complications, and other potential confounders. They also were at 5.6-fold increased risk for psychotic depression and a whopping 7.8-fold greater risk of bipolar disorder than offspring with neither risk factor.

Moreover, in an earlier study, among men in the Northern Finland cohort who were assessed at age 33 years, investigators found that maternal depression during pregnancy was associated with an adjusted 1.4-fold increased likelihood of having a criminal record for a nonviolent offense, a 1.6-fold increased risk of violent crime, and a 1.7-fold increase in violent recidivism. In contrast, women whose mothers were depressed during pregnancy didn’t have a significantly higher rate of criminality, compared with those whose mothers weren’t depressed (J Affect Disord. 2003 May;74[3]:273-8).

In another earlier analysis, Dr. Taka-Eilola’s senior coinvestigators demonstrated that the risk of schizophrenia in the Northern Finland offspring was 2.6-fold greater if there was parental psychosis but no maternal antepartum depression than if neither was present, while the risk was 9.4-fold higher when both risk factors were present (Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;167[1]:70-7).

Dr. Taka-Eilola, a primary care physician, said that postpartum depression garners news headlines and is far more extensively researched than is antepartum depression, but as the Finnish data show, antepartum depression is at least as common and deserves to be taken seriously. It’s important to screen for it and to treat it in an effort to prevent adverse effects in the offspring, as well as out of concern for the mother’s well-being, she emphasized. She believes this is now more likely to happen as a consequence of a recent World Psychiatric Association report calling for greater clinician attention to perinatal mental health.

Dr. Taka-Eilola reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the Northern Finland Birth Cohort Study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Cultural Foundation Lapland Regional Fund, and grants from various nonprofit foundations.

PARIS – Maternal depression during pregnancy is a common occurrence that can have far-reaching effects in the offspring, according to Tiina Taka-Eilola, MD, of the University of Oulu (Finland).

Indeed, maternal antepartum depression may best be thought of as an adverse environmental factor that exacerbates the impact of any underlying genetic vulnerability to severe mental disorder that may be present in the offspring, she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

At midgestation, back in the mid-1960s, 13.9% of the mothers of the Northern Finland Birth Cohort acknowledged feeling “depressed” or “very depressed,” rates consistent with those reported in other studies using standardized depression assessment instruments. Their offspring, by age 43 years, were 1.6-fold more likely to have a history of a current or past nonpsychotic mood disorder and 2-fold more likely to have had a psychotic mood disorder than did the offspring of mothers free of antepartum depression.

These risks were greatly amplified if either parent experienced a hospital-treated severe mental disorder before, during, or up to 18 years after the pregnancy. Offspring who had both a mother who experienced antepartum depression and a parent with a severe, hospital-treated mental disorder were at 3.9-fold increased risk for being diagnosed with nonpsychotic depression by age 43 years in an analysis adjusted for sex, perinatal complications, and other potential confounders. They also were at 5.6-fold increased risk for psychotic depression and a whopping 7.8-fold greater risk of bipolar disorder than offspring with neither risk factor.

Moreover, in an earlier study, among men in the Northern Finland cohort who were assessed at age 33 years, investigators found that maternal depression during pregnancy was associated with an adjusted 1.4-fold increased likelihood of having a criminal record for a nonviolent offense, a 1.6-fold increased risk of violent crime, and a 1.7-fold increase in violent recidivism. In contrast, women whose mothers were depressed during pregnancy didn’t have a significantly higher rate of criminality, compared with those whose mothers weren’t depressed (J Affect Disord. 2003 May;74[3]:273-8).

In another earlier analysis, Dr. Taka-Eilola’s senior coinvestigators demonstrated that the risk of schizophrenia in the Northern Finland offspring was 2.6-fold greater if there was parental psychosis but no maternal antepartum depression than if neither was present, while the risk was 9.4-fold higher when both risk factors were present (Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;167[1]:70-7).

Dr. Taka-Eilola, a primary care physician, said that postpartum depression garners news headlines and is far more extensively researched than is antepartum depression, but as the Finnish data show, antepartum depression is at least as common and deserves to be taken seriously. It’s important to screen for it and to treat it in an effort to prevent adverse effects in the offspring, as well as out of concern for the mother’s well-being, she emphasized. She believes this is now more likely to happen as a consequence of a recent World Psychiatric Association report calling for greater clinician attention to perinatal mental health.

Dr. Taka-Eilola reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the Northern Finland Birth Cohort Study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Cultural Foundation Lapland Regional Fund, and grants from various nonprofit foundations.

PARIS – Maternal depression during pregnancy is a common occurrence that can have far-reaching effects in the offspring, according to Tiina Taka-Eilola, MD, of the University of Oulu (Finland).

Indeed, maternal antepartum depression may best be thought of as an adverse environmental factor that exacerbates the impact of any underlying genetic vulnerability to severe mental disorder that may be present in the offspring, she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

At midgestation, back in the mid-1960s, 13.9% of the mothers of the Northern Finland Birth Cohort acknowledged feeling “depressed” or “very depressed,” rates consistent with those reported in other studies using standardized depression assessment instruments. Their offspring, by age 43 years, were 1.6-fold more likely to have a history of a current or past nonpsychotic mood disorder and 2-fold more likely to have had a psychotic mood disorder than did the offspring of mothers free of antepartum depression.

These risks were greatly amplified if either parent experienced a hospital-treated severe mental disorder before, during, or up to 18 years after the pregnancy. Offspring who had both a mother who experienced antepartum depression and a parent with a severe, hospital-treated mental disorder were at 3.9-fold increased risk for being diagnosed with nonpsychotic depression by age 43 years in an analysis adjusted for sex, perinatal complications, and other potential confounders. They also were at 5.6-fold increased risk for psychotic depression and a whopping 7.8-fold greater risk of bipolar disorder than offspring with neither risk factor.

Moreover, in an earlier study, among men in the Northern Finland cohort who were assessed at age 33 years, investigators found that maternal depression during pregnancy was associated with an adjusted 1.4-fold increased likelihood of having a criminal record for a nonviolent offense, a 1.6-fold increased risk of violent crime, and a 1.7-fold increase in violent recidivism. In contrast, women whose mothers were depressed during pregnancy didn’t have a significantly higher rate of criminality, compared with those whose mothers weren’t depressed (J Affect Disord. 2003 May;74[3]:273-8).

In another earlier analysis, Dr. Taka-Eilola’s senior coinvestigators demonstrated that the risk of schizophrenia in the Northern Finland offspring was 2.6-fold greater if there was parental psychosis but no maternal antepartum depression than if neither was present, while the risk was 9.4-fold higher when both risk factors were present (Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;167[1]:70-7).

Dr. Taka-Eilola, a primary care physician, said that postpartum depression garners news headlines and is far more extensively researched than is antepartum depression, but as the Finnish data show, antepartum depression is at least as common and deserves to be taken seriously. It’s important to screen for it and to treat it in an effort to prevent adverse effects in the offspring, as well as out of concern for the mother’s well-being, she emphasized. She believes this is now more likely to happen as a consequence of a recent World Psychiatric Association report calling for greater clinician attention to perinatal mental health.

Dr. Taka-Eilola reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the Northern Finland Birth Cohort Study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Cultural Foundation Lapland Regional Fund, and grants from various nonprofit foundations.

AT THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: By midlife, offspring of an mother who had antepartum depression and a parent with a severe, hospital-treated mental disorder were at an adjusted 5.6-fold increased risk for psychotic depression and 7.8-fold greater risk of bipolar disorder than the offspring with neither risk factor.

Data source: The Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 is an ongoing, observational, prospective, general population-based study of the 12,058 individuals born in the two northernmost provinces of Finland during 1966.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Cultural Foundation Lapland Regional Fund, and grants from various nonprofit foundations.

U.S. House passes 20-week abortion ban

The U.S. House of Representatives has passed legislation that would ban abortions starting at 20 weeks.

This isn’t the first time in recent years that the Republican-controlled House has passed a 20-week ban. What’s different this time is that it has the support of the White House. Despite the Trump administration’s support for the bill, it’s unlikely to garner the support necessary to come up for a vote in the U.S. Senate.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), which opposes the bill, called it a “cruel ban” that would leave many women without treatment options.

“Many women seek abortion later in pregnancy because restrictive state laws or the lack of abortion providers made it impossible for them to access abortion earlier in their pregnancies,” ACOG said in a statement. “Additionally, many women are delayed in their ability to access abortion care because they need time to raise or save enough money to pay for it.”

Currently, 17 states have enacted their own 20-week abortion bans, according to ACOG.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

The U.S. House of Representatives has passed legislation that would ban abortions starting at 20 weeks.

This isn’t the first time in recent years that the Republican-controlled House has passed a 20-week ban. What’s different this time is that it has the support of the White House. Despite the Trump administration’s support for the bill, it’s unlikely to garner the support necessary to come up for a vote in the U.S. Senate.