User login

New ADA hypertension and diabetes treatment guide features visual aid

Clinicians can consult a diagram to plan treatment of hypertension in diabetes patients as part of the new American Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association” was published in the September 2017 issue of Diabetes Care, and online on Aug. 22. The statement updates the ADA’s previous statement on hypertension and diabetes published in 2003.

“Numerous studies have shown that antihypertensive therapy reduces ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] events, heart failure, and microvascular complications in people with diabetes,” wrote Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues.

The statement is a collaboration between nine diabetes experts from the United States, Europe, and Australia whose specialties include endocrinology, nephrology, cardiology, and internal medicine (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep.;40:1273-84).

The statement recommends that diabetes patients have their blood pressure checked at every routine clinical visit and that those with an elevated blood pressure on a clinical visit (defined as office-based measurements of 140/90 mm Hg and higher) have multiple measurements, including on a separate day to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition, during the initial evaluation, and then periodically, diabetes patients should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension “to individualize blood pressure goals, select the most appropriate antihypertensive agents, and minimize adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy,” according to the recommendations.

For most patients with diabetes and hypertension, the goal should be a blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, and even lower targets may be appropriate for patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers said.

The guidelines include recommendations for managing hypertension and diabetes through lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and following a healthy diet with minimal sodium intake and an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

The guidelines also emphasize the need for caution when treating older adults who are taking multiple medications. “Systolic blood pressure should be the main target of treatment,” for adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes and hypertension, the authors said.

In addition, the guidelines provide direction for clinicians treating pregnant women. “During pregnancy, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], or spironolactone is contraindicated, as [these medications] may cause fetal damage,” the authors wrote. Pregnant women with preexisting hypertension or with mild gestational hypertension with systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg, and no sign of end-organ damage need not take antihypertensive medications, they said. For pregnant women who require antihypertensive treatment, the aim should be a systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure between 80 mm Hg and 105 mm Hg.

The authors concluded that there currently is insufficient evidence to support blood pressure medication for diabetes patients without hypertension.

The recommendations reference several key clinical trials that compared intensive and standard hypertension treatment strategies: the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, the ADVANCE BP (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation – Blood Pressure) trial, the HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment) trial, and SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial).

Lead author Dr. de Boer reported serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and his institution has received research equipment and supplies from Medtronic and Abbott. Study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Abbott, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

Clinicians can consult a diagram to plan treatment of hypertension in diabetes patients as part of the new American Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association” was published in the September 2017 issue of Diabetes Care, and online on Aug. 22. The statement updates the ADA’s previous statement on hypertension and diabetes published in 2003.

“Numerous studies have shown that antihypertensive therapy reduces ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] events, heart failure, and microvascular complications in people with diabetes,” wrote Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues.

The statement is a collaboration between nine diabetes experts from the United States, Europe, and Australia whose specialties include endocrinology, nephrology, cardiology, and internal medicine (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep.;40:1273-84).

The statement recommends that diabetes patients have their blood pressure checked at every routine clinical visit and that those with an elevated blood pressure on a clinical visit (defined as office-based measurements of 140/90 mm Hg and higher) have multiple measurements, including on a separate day to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition, during the initial evaluation, and then periodically, diabetes patients should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension “to individualize blood pressure goals, select the most appropriate antihypertensive agents, and minimize adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy,” according to the recommendations.

For most patients with diabetes and hypertension, the goal should be a blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, and even lower targets may be appropriate for patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers said.

The guidelines include recommendations for managing hypertension and diabetes through lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and following a healthy diet with minimal sodium intake and an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

The guidelines also emphasize the need for caution when treating older adults who are taking multiple medications. “Systolic blood pressure should be the main target of treatment,” for adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes and hypertension, the authors said.

In addition, the guidelines provide direction for clinicians treating pregnant women. “During pregnancy, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], or spironolactone is contraindicated, as [these medications] may cause fetal damage,” the authors wrote. Pregnant women with preexisting hypertension or with mild gestational hypertension with systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg, and no sign of end-organ damage need not take antihypertensive medications, they said. For pregnant women who require antihypertensive treatment, the aim should be a systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure between 80 mm Hg and 105 mm Hg.

The authors concluded that there currently is insufficient evidence to support blood pressure medication for diabetes patients without hypertension.

The recommendations reference several key clinical trials that compared intensive and standard hypertension treatment strategies: the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, the ADVANCE BP (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation – Blood Pressure) trial, the HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment) trial, and SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial).

Lead author Dr. de Boer reported serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and his institution has received research equipment and supplies from Medtronic and Abbott. Study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Abbott, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

Clinicians can consult a diagram to plan treatment of hypertension in diabetes patients as part of the new American Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association” was published in the September 2017 issue of Diabetes Care, and online on Aug. 22. The statement updates the ADA’s previous statement on hypertension and diabetes published in 2003.

“Numerous studies have shown that antihypertensive therapy reduces ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] events, heart failure, and microvascular complications in people with diabetes,” wrote Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues.

The statement is a collaboration between nine diabetes experts from the United States, Europe, and Australia whose specialties include endocrinology, nephrology, cardiology, and internal medicine (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep.;40:1273-84).

The statement recommends that diabetes patients have their blood pressure checked at every routine clinical visit and that those with an elevated blood pressure on a clinical visit (defined as office-based measurements of 140/90 mm Hg and higher) have multiple measurements, including on a separate day to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition, during the initial evaluation, and then periodically, diabetes patients should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension “to individualize blood pressure goals, select the most appropriate antihypertensive agents, and minimize adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy,” according to the recommendations.

For most patients with diabetes and hypertension, the goal should be a blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, and even lower targets may be appropriate for patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers said.

The guidelines include recommendations for managing hypertension and diabetes through lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and following a healthy diet with minimal sodium intake and an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

The guidelines also emphasize the need for caution when treating older adults who are taking multiple medications. “Systolic blood pressure should be the main target of treatment,” for adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes and hypertension, the authors said.

In addition, the guidelines provide direction for clinicians treating pregnant women. “During pregnancy, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], or spironolactone is contraindicated, as [these medications] may cause fetal damage,” the authors wrote. Pregnant women with preexisting hypertension or with mild gestational hypertension with systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg, and no sign of end-organ damage need not take antihypertensive medications, they said. For pregnant women who require antihypertensive treatment, the aim should be a systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure between 80 mm Hg and 105 mm Hg.

The authors concluded that there currently is insufficient evidence to support blood pressure medication for diabetes patients without hypertension.

The recommendations reference several key clinical trials that compared intensive and standard hypertension treatment strategies: the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, the ADVANCE BP (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation – Blood Pressure) trial, the HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment) trial, and SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial).

Lead author Dr. de Boer reported serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and his institution has received research equipment and supplies from Medtronic and Abbott. Study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Abbott, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Insist on flu vaccination for all, say experts

sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

Some good news about the flu – vaccination rates increased slightly last year, compared with the previous year among all individuals aged 6 months and older without contraindications, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts continue to recommend annual influenza vaccination for all persons aged 6 months and older, but they emphasize the need to identify those at risk of not getting vaccinated and develop strategies to increase vaccination coverage.

“Vaccines are among the greatest public health achievements of modern times, but they are only as useful as we as a society take advantage of them,” Secretary of Health & Human Services Thomas E. Price, MD, said at the briefing.

Overall flu vaccination in the United States was 47% for the 2016-2017 season, compared with 46% during the 2015-2016 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Price emphasized that vaccination is only part of a successful flu prevention strategy. Stay home when you are sick to help avoid spreading germs to others and take antiviral drugs if a doctor prescribes them to help reduce and avoid complications from flu, he said.

Children aged 6-23 months were the only population subgroup to meet the 70% Healthy People 2020 goal last year, with a rate of 73%, said Patricia A. Stinchfield, RN, CPNP, senior director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Hospital Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“Our goal is to increase coverage for children of all ages,” she said. But it’s not just about the kids themselves, she emphasized.

“If your child gets the flu, they expose babies, grandparents, pregnant women. We need to vaccinate children to protect the public at large,” she said. In addition, health care professionals must be clear about recommending vaccination. The research shows that a specific recommendation often makes the difference for vaccinating families.

Pregnant women are among those who can and should safely be vaccinated, Ms. Stinchfield emphasized. Flu vaccination among pregnant women was 54% in 2016-2017, similar to the past three flu seasons, and approximately two-thirds (67%) of pregnant women in 2016-2017 reported that a health care provider recommended and offered flu vaccination, according to CDC data.

Older adults also are important targets for flu vaccination, noted Kathleen M. Neuzil, MD, director of the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Last year, approximately 65% of U.S. adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated, which was the largest subgroup of adults aged 18 years and older, she said. Older adults may be caring for frail spouses or infant grandchildren, so protecting others should be a motivating factor in continuing to encourage vaccination in this age group, she noted.

The flu vaccine supply is plentiful going into the start of the 2016-2017 flu season, with an estimated 166 million doses available in several formulations, said Daniel B. Jernigan, MD, director of the CDC’s Influenza Division.

Options for vaccination include the standard vaccine, a cell-based vaccine, and a recombinant vaccine. In addition, an adjuvanted vaccine and a high-dose vaccine are available specifically for adults aged 65 years and older; these vaccines are designed to provoke a stronger immune response, Dr. Jernigan said.

However, the briefing participants agreed that the best strategy is to get vaccinated as soon as possible, rather than postponing vaccination in order to secure a particular vaccine type.

Clinicians should not underestimate the power of leading by example when it comes to flu vaccination, Dr. Schaffner noted. Support from the highest levels of administration is important to help overcome barriers to vaccination coverage for health care workers by making vaccination easy and accessible, he said.

The overall influenza vaccination coverage estimate among health care providers was 79% for the 2016-2017 season, similar to the 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 seasons, but representing a 15% increase since 2010-2011. Vaccination coverage was highest among health care personnel whose workplaces required it.

Complete data on 2016-2017 vaccination coverage in health care workers and in pregnant women were published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Sept. 29.

The CDC’s complete flu vaccination recommendations are available online.

The briefing participants had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

Some good news about the flu – vaccination rates increased slightly last year, compared with the previous year among all individuals aged 6 months and older without contraindications, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts continue to recommend annual influenza vaccination for all persons aged 6 months and older, but they emphasize the need to identify those at risk of not getting vaccinated and develop strategies to increase vaccination coverage.

“Vaccines are among the greatest public health achievements of modern times, but they are only as useful as we as a society take advantage of them,” Secretary of Health & Human Services Thomas E. Price, MD, said at the briefing.

Overall flu vaccination in the United States was 47% for the 2016-2017 season, compared with 46% during the 2015-2016 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Price emphasized that vaccination is only part of a successful flu prevention strategy. Stay home when you are sick to help avoid spreading germs to others and take antiviral drugs if a doctor prescribes them to help reduce and avoid complications from flu, he said.

Children aged 6-23 months were the only population subgroup to meet the 70% Healthy People 2020 goal last year, with a rate of 73%, said Patricia A. Stinchfield, RN, CPNP, senior director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Hospital Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“Our goal is to increase coverage for children of all ages,” she said. But it’s not just about the kids themselves, she emphasized.

“If your child gets the flu, they expose babies, grandparents, pregnant women. We need to vaccinate children to protect the public at large,” she said. In addition, health care professionals must be clear about recommending vaccination. The research shows that a specific recommendation often makes the difference for vaccinating families.

Pregnant women are among those who can and should safely be vaccinated, Ms. Stinchfield emphasized. Flu vaccination among pregnant women was 54% in 2016-2017, similar to the past three flu seasons, and approximately two-thirds (67%) of pregnant women in 2016-2017 reported that a health care provider recommended and offered flu vaccination, according to CDC data.

Older adults also are important targets for flu vaccination, noted Kathleen M. Neuzil, MD, director of the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Last year, approximately 65% of U.S. adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated, which was the largest subgroup of adults aged 18 years and older, she said. Older adults may be caring for frail spouses or infant grandchildren, so protecting others should be a motivating factor in continuing to encourage vaccination in this age group, she noted.

The flu vaccine supply is plentiful going into the start of the 2016-2017 flu season, with an estimated 166 million doses available in several formulations, said Daniel B. Jernigan, MD, director of the CDC’s Influenza Division.

Options for vaccination include the standard vaccine, a cell-based vaccine, and a recombinant vaccine. In addition, an adjuvanted vaccine and a high-dose vaccine are available specifically for adults aged 65 years and older; these vaccines are designed to provoke a stronger immune response, Dr. Jernigan said.

However, the briefing participants agreed that the best strategy is to get vaccinated as soon as possible, rather than postponing vaccination in order to secure a particular vaccine type.

Clinicians should not underestimate the power of leading by example when it comes to flu vaccination, Dr. Schaffner noted. Support from the highest levels of administration is important to help overcome barriers to vaccination coverage for health care workers by making vaccination easy and accessible, he said.

The overall influenza vaccination coverage estimate among health care providers was 79% for the 2016-2017 season, similar to the 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 seasons, but representing a 15% increase since 2010-2011. Vaccination coverage was highest among health care personnel whose workplaces required it.

Complete data on 2016-2017 vaccination coverage in health care workers and in pregnant women were published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Sept. 29.

The CDC’s complete flu vaccination recommendations are available online.

The briefing participants had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

Some good news about the flu – vaccination rates increased slightly last year, compared with the previous year among all individuals aged 6 months and older without contraindications, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts continue to recommend annual influenza vaccination for all persons aged 6 months and older, but they emphasize the need to identify those at risk of not getting vaccinated and develop strategies to increase vaccination coverage.

“Vaccines are among the greatest public health achievements of modern times, but they are only as useful as we as a society take advantage of them,” Secretary of Health & Human Services Thomas E. Price, MD, said at the briefing.

Overall flu vaccination in the United States was 47% for the 2016-2017 season, compared with 46% during the 2015-2016 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Price emphasized that vaccination is only part of a successful flu prevention strategy. Stay home when you are sick to help avoid spreading germs to others and take antiviral drugs if a doctor prescribes them to help reduce and avoid complications from flu, he said.

Children aged 6-23 months were the only population subgroup to meet the 70% Healthy People 2020 goal last year, with a rate of 73%, said Patricia A. Stinchfield, RN, CPNP, senior director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Hospital Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“Our goal is to increase coverage for children of all ages,” she said. But it’s not just about the kids themselves, she emphasized.

“If your child gets the flu, they expose babies, grandparents, pregnant women. We need to vaccinate children to protect the public at large,” she said. In addition, health care professionals must be clear about recommending vaccination. The research shows that a specific recommendation often makes the difference for vaccinating families.

Pregnant women are among those who can and should safely be vaccinated, Ms. Stinchfield emphasized. Flu vaccination among pregnant women was 54% in 2016-2017, similar to the past three flu seasons, and approximately two-thirds (67%) of pregnant women in 2016-2017 reported that a health care provider recommended and offered flu vaccination, according to CDC data.

Older adults also are important targets for flu vaccination, noted Kathleen M. Neuzil, MD, director of the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Last year, approximately 65% of U.S. adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated, which was the largest subgroup of adults aged 18 years and older, she said. Older adults may be caring for frail spouses or infant grandchildren, so protecting others should be a motivating factor in continuing to encourage vaccination in this age group, she noted.

The flu vaccine supply is plentiful going into the start of the 2016-2017 flu season, with an estimated 166 million doses available in several formulations, said Daniel B. Jernigan, MD, director of the CDC’s Influenza Division.

Options for vaccination include the standard vaccine, a cell-based vaccine, and a recombinant vaccine. In addition, an adjuvanted vaccine and a high-dose vaccine are available specifically for adults aged 65 years and older; these vaccines are designed to provoke a stronger immune response, Dr. Jernigan said.

However, the briefing participants agreed that the best strategy is to get vaccinated as soon as possible, rather than postponing vaccination in order to secure a particular vaccine type.

Clinicians should not underestimate the power of leading by example when it comes to flu vaccination, Dr. Schaffner noted. Support from the highest levels of administration is important to help overcome barriers to vaccination coverage for health care workers by making vaccination easy and accessible, he said.

The overall influenza vaccination coverage estimate among health care providers was 79% for the 2016-2017 season, similar to the 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 seasons, but representing a 15% increase since 2010-2011. Vaccination coverage was highest among health care personnel whose workplaces required it.

Complete data on 2016-2017 vaccination coverage in health care workers and in pregnant women were published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Sept. 29.

The CDC’s complete flu vaccination recommendations are available online.

The briefing participants had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

A spike in syphilis puts prenatal care in focus

Fifteen years ago, reported cases of syphilis in the United States were so infrequent that public health officials thought it might join the ranks of malaria, polio, and smallpox as an eradicated disease. That turned out to be wishful thinking.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2012 and 2015, the overall rates of syphilis in the United States increased by 48%, while the rates of primary and secondary infection among women spiked by 56%. That was a compelling enough rise, but fresh data from the agency indicate that the overall rates of syphilis increased by 17.6% between 2015 and 2016, and by 74% between 2012 and 2016.

These trends prompted the CDC to launch a “call to action” educational campaign in an effort to curb the rising syphilis rates. The United States Preventive Services Task Force also is taking action. It recently posted a research plan on screening pregnant women for syphilis that will form the basis of a forthcoming evidence review and, potentially, new recommendations.

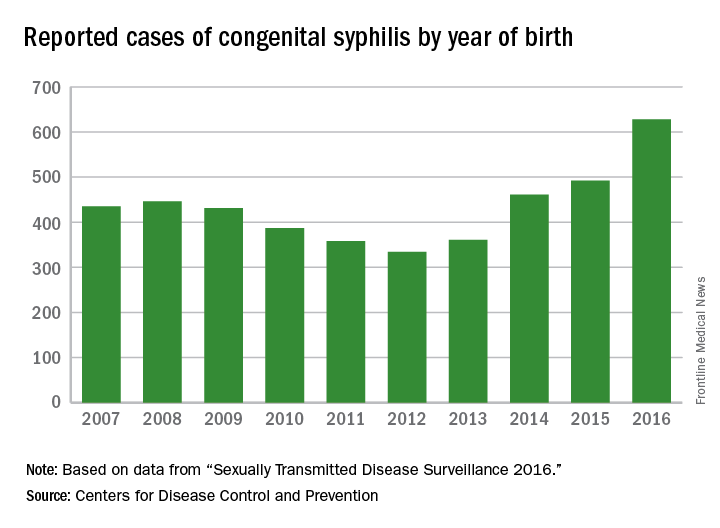

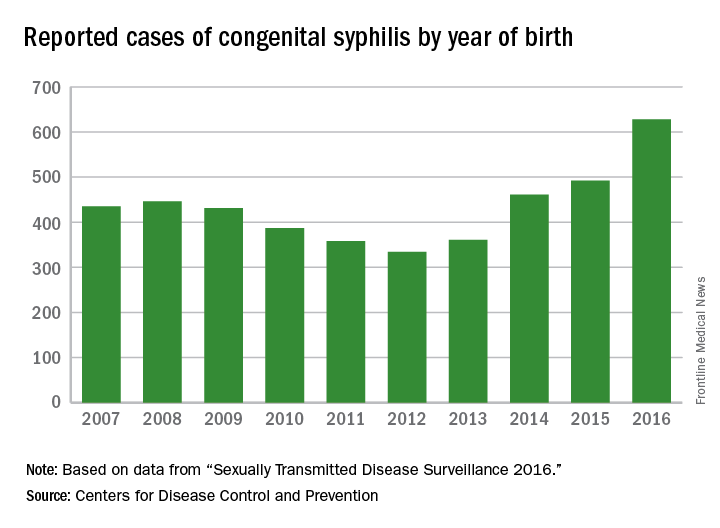

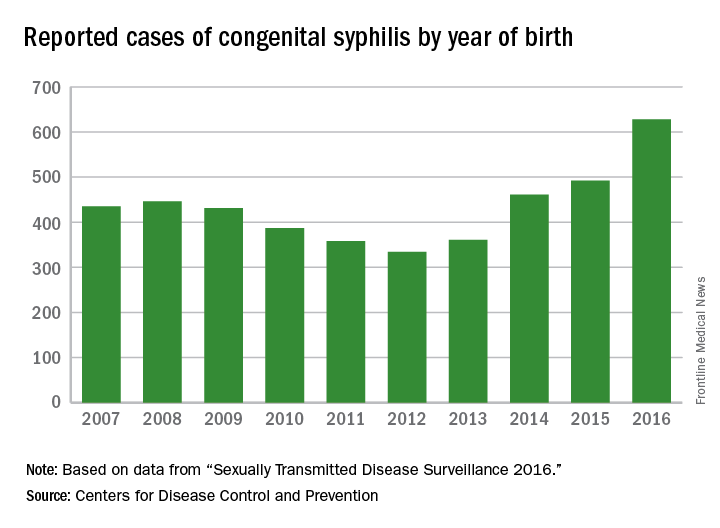

observed in all regions of the United States during the same time period, said Dr. Kidd, who coauthored a 2015 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on the topic (MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64[44]:1241-5). That analysis found that during 2012-2014, the number of reported CS cases in the United States increased from 334 to 458, which represents a rate increase from 8.4 to 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This contrasted with earlier data, which found that the overall rate of reported CS had decreased from 10.5 to 8.4 cases per 100,000 live births during 2008-2012.

In 2016, there were 628 reported cases of CS, including 41 syphilitic stillbirths, according to the CDC.

“Congenital syphilis rates tend to track female syphilis rates; so as female rates go up, we know we’re going to see a rise in congenital syphilis rates,” Dr. Kidd said. “One way to prevent syphilis is to prevent female syphilis altogether. Another way is to prevent the transmission from mother to infant when you have a pregnant woman with syphilis.”

Lack of prenatal care

CDC guidelines recommend that all pregnant women undergo routine serologic screening for syphilis during their first prenatal visit. Additional testing at 28 weeks’ gestation and again at delivery is warranted for women who are at increased risk or live in communities with increased prevalence of syphilis infection. That approach may seem sensible, but such prevention measures are ineffective when mothers don’t receive any prenatal care or receive it late, which happens in about half of all CS cases, Dr. Kidd said.

Inconsistent, inadequate, or a total absence of prenatal care is “probably the biggest risk factor for vertical transmission, especially among high-risk populations, where there is an increased background prevalence of syphilis in childbearing women,” said Robert Maupin, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology in the section of maternal-fetal medicine at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

To complicate matters, women who receive no or inconsistent prenatal care face an increased risk for preterm birth, Dr. Maupin noted. So while a clinician might follow CDC recommendations that pregnant women with confirmed or suspected syphilis complete a course of long-acting penicillin G for at least 30 days or longer before the child is born, “the timing of being able to implement effective prevention and treatment prior to that 30-day window can sometimes be compromised by the fact that she ends up delivering prematurely,” he said. “If someone’s not adequately linked to consistent prenatal care, she may not complete that full course of prevention. Additionally, patterns of care are often fragmented, meaning that patients may go to one clinic or one provider, may not return, and may end up switching to a different clinic. That translates into a potential lag in implementing treatment or making a diagnosis in the first place, and that may be disruptive in the context of our attempted prevention measures.”

Precise reasons why some pregnant women in the United States receive no or inadequate prenatal care remain unclear.

“Anecdotally, in the West, I hear that women with drug abuse histories or drug abuse issues [are vulnerable], or they may be homeless or have mental health issues,” Dr. Kidd said. “In other areas of the country, people feel that it’s more of an insurance or access to care issue, but we don’t have data on that here at the CDC.”

Repeat screening

In 2015, a large analysis of women who were commercially-insured or Medicaid-insured found that more than 95% who received prenatal care were screened for syphilis at least once during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125[5]:1211-6). However, CDC data of CS cases shows that about 15% of their mothers are infected during pregnancy, which would occur after that first screening test.

“That’s where the repeat screening early in the third trimester and at delivery becomes the real issue,” Dr. Kidd said. “For high-risk women, including those who live in the high morbidity areas, they should be screened again later in pregnancy. Many ob.gyns. may not be aware of that recommendation, or may not be aware they’re in an area that does have a high syphilis morbidity, and that the pregnant women who are seeing them may be at increased risk of syphilis.”

Dr. Maupin, who is associate dean of diversity and community engagement at LSU Health Sciences Center, advised clinicians to view CS with the same sense of urgency that existed in previous years with perinatal HIV transmission.

“In the last decade and a half we’ve seen a substantial decline in perinatal HIV transmission because of intensive efforts on the public health side in terms of both screening and use of treatment,” he said. “If we look at this with a similar level of contemporary urgency, it will bear similar fruit over time. Additionally, from a maternal-fetal medicine standpoint, the more effectively we treat and/or control diseases and comorbidities prior to pregnancy, the less likely those things will have an adverse impact on the health and well-being of the newborn.”

Steps you can take to curb CS

In its “call to action” on syphilis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cited several practical ways that clinicians can combat the spread of congenital syphilis (CS).

1. Complete a sexual history for your patients. The CDC recommends following this with STD counseling for those at risk and contraception counseling for women at risk of unintended pregnancy.

2. Test all pregnant women for syphilis. This should be done at the first prenatal visit, with repeat screening for pregnant women at high risk and in areas of high prevalence at the beginning of the third trimester and again at delivery.

3. Treat women infected with syphilis immediately. If a woman has syphilis or suspected syphilis, she should be treated with long-acting penicillin G, especially if she is pregnant. CDC also calls for testing and treating the infected woman’s sex partner(s) to avoid reinfection.

4. Confirm syphilis testing at delivery. Before discharging the mother or infant from the hospital, check that the mother has been tested for syphilis at least once during pregnancy or at delivery. All women who deliver a stillborn infant should be tested for syphilis.

5. Report CS cases to the local or state health department within 24 hours.

Fifteen years ago, reported cases of syphilis in the United States were so infrequent that public health officials thought it might join the ranks of malaria, polio, and smallpox as an eradicated disease. That turned out to be wishful thinking.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2012 and 2015, the overall rates of syphilis in the United States increased by 48%, while the rates of primary and secondary infection among women spiked by 56%. That was a compelling enough rise, but fresh data from the agency indicate that the overall rates of syphilis increased by 17.6% between 2015 and 2016, and by 74% between 2012 and 2016.

These trends prompted the CDC to launch a “call to action” educational campaign in an effort to curb the rising syphilis rates. The United States Preventive Services Task Force also is taking action. It recently posted a research plan on screening pregnant women for syphilis that will form the basis of a forthcoming evidence review and, potentially, new recommendations.

observed in all regions of the United States during the same time period, said Dr. Kidd, who coauthored a 2015 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on the topic (MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64[44]:1241-5). That analysis found that during 2012-2014, the number of reported CS cases in the United States increased from 334 to 458, which represents a rate increase from 8.4 to 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This contrasted with earlier data, which found that the overall rate of reported CS had decreased from 10.5 to 8.4 cases per 100,000 live births during 2008-2012.

In 2016, there were 628 reported cases of CS, including 41 syphilitic stillbirths, according to the CDC.

“Congenital syphilis rates tend to track female syphilis rates; so as female rates go up, we know we’re going to see a rise in congenital syphilis rates,” Dr. Kidd said. “One way to prevent syphilis is to prevent female syphilis altogether. Another way is to prevent the transmission from mother to infant when you have a pregnant woman with syphilis.”

Lack of prenatal care

CDC guidelines recommend that all pregnant women undergo routine serologic screening for syphilis during their first prenatal visit. Additional testing at 28 weeks’ gestation and again at delivery is warranted for women who are at increased risk or live in communities with increased prevalence of syphilis infection. That approach may seem sensible, but such prevention measures are ineffective when mothers don’t receive any prenatal care or receive it late, which happens in about half of all CS cases, Dr. Kidd said.

Inconsistent, inadequate, or a total absence of prenatal care is “probably the biggest risk factor for vertical transmission, especially among high-risk populations, where there is an increased background prevalence of syphilis in childbearing women,” said Robert Maupin, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology in the section of maternal-fetal medicine at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

To complicate matters, women who receive no or inconsistent prenatal care face an increased risk for preterm birth, Dr. Maupin noted. So while a clinician might follow CDC recommendations that pregnant women with confirmed or suspected syphilis complete a course of long-acting penicillin G for at least 30 days or longer before the child is born, “the timing of being able to implement effective prevention and treatment prior to that 30-day window can sometimes be compromised by the fact that she ends up delivering prematurely,” he said. “If someone’s not adequately linked to consistent prenatal care, she may not complete that full course of prevention. Additionally, patterns of care are often fragmented, meaning that patients may go to one clinic or one provider, may not return, and may end up switching to a different clinic. That translates into a potential lag in implementing treatment or making a diagnosis in the first place, and that may be disruptive in the context of our attempted prevention measures.”

Precise reasons why some pregnant women in the United States receive no or inadequate prenatal care remain unclear.

“Anecdotally, in the West, I hear that women with drug abuse histories or drug abuse issues [are vulnerable], or they may be homeless or have mental health issues,” Dr. Kidd said. “In other areas of the country, people feel that it’s more of an insurance or access to care issue, but we don’t have data on that here at the CDC.”

Repeat screening

In 2015, a large analysis of women who were commercially-insured or Medicaid-insured found that more than 95% who received prenatal care were screened for syphilis at least once during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125[5]:1211-6). However, CDC data of CS cases shows that about 15% of their mothers are infected during pregnancy, which would occur after that first screening test.

“That’s where the repeat screening early in the third trimester and at delivery becomes the real issue,” Dr. Kidd said. “For high-risk women, including those who live in the high morbidity areas, they should be screened again later in pregnancy. Many ob.gyns. may not be aware of that recommendation, or may not be aware they’re in an area that does have a high syphilis morbidity, and that the pregnant women who are seeing them may be at increased risk of syphilis.”

Dr. Maupin, who is associate dean of diversity and community engagement at LSU Health Sciences Center, advised clinicians to view CS with the same sense of urgency that existed in previous years with perinatal HIV transmission.

“In the last decade and a half we’ve seen a substantial decline in perinatal HIV transmission because of intensive efforts on the public health side in terms of both screening and use of treatment,” he said. “If we look at this with a similar level of contemporary urgency, it will bear similar fruit over time. Additionally, from a maternal-fetal medicine standpoint, the more effectively we treat and/or control diseases and comorbidities prior to pregnancy, the less likely those things will have an adverse impact on the health and well-being of the newborn.”

Steps you can take to curb CS

In its “call to action” on syphilis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cited several practical ways that clinicians can combat the spread of congenital syphilis (CS).

1. Complete a sexual history for your patients. The CDC recommends following this with STD counseling for those at risk and contraception counseling for women at risk of unintended pregnancy.

2. Test all pregnant women for syphilis. This should be done at the first prenatal visit, with repeat screening for pregnant women at high risk and in areas of high prevalence at the beginning of the third trimester and again at delivery.

3. Treat women infected with syphilis immediately. If a woman has syphilis or suspected syphilis, she should be treated with long-acting penicillin G, especially if she is pregnant. CDC also calls for testing and treating the infected woman’s sex partner(s) to avoid reinfection.

4. Confirm syphilis testing at delivery. Before discharging the mother or infant from the hospital, check that the mother has been tested for syphilis at least once during pregnancy or at delivery. All women who deliver a stillborn infant should be tested for syphilis.

5. Report CS cases to the local or state health department within 24 hours.

Fifteen years ago, reported cases of syphilis in the United States were so infrequent that public health officials thought it might join the ranks of malaria, polio, and smallpox as an eradicated disease. That turned out to be wishful thinking.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2012 and 2015, the overall rates of syphilis in the United States increased by 48%, while the rates of primary and secondary infection among women spiked by 56%. That was a compelling enough rise, but fresh data from the agency indicate that the overall rates of syphilis increased by 17.6% between 2015 and 2016, and by 74% between 2012 and 2016.

These trends prompted the CDC to launch a “call to action” educational campaign in an effort to curb the rising syphilis rates. The United States Preventive Services Task Force also is taking action. It recently posted a research plan on screening pregnant women for syphilis that will form the basis of a forthcoming evidence review and, potentially, new recommendations.

observed in all regions of the United States during the same time period, said Dr. Kidd, who coauthored a 2015 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on the topic (MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64[44]:1241-5). That analysis found that during 2012-2014, the number of reported CS cases in the United States increased from 334 to 458, which represents a rate increase from 8.4 to 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This contrasted with earlier data, which found that the overall rate of reported CS had decreased from 10.5 to 8.4 cases per 100,000 live births during 2008-2012.

In 2016, there were 628 reported cases of CS, including 41 syphilitic stillbirths, according to the CDC.

“Congenital syphilis rates tend to track female syphilis rates; so as female rates go up, we know we’re going to see a rise in congenital syphilis rates,” Dr. Kidd said. “One way to prevent syphilis is to prevent female syphilis altogether. Another way is to prevent the transmission from mother to infant when you have a pregnant woman with syphilis.”

Lack of prenatal care

CDC guidelines recommend that all pregnant women undergo routine serologic screening for syphilis during their first prenatal visit. Additional testing at 28 weeks’ gestation and again at delivery is warranted for women who are at increased risk or live in communities with increased prevalence of syphilis infection. That approach may seem sensible, but such prevention measures are ineffective when mothers don’t receive any prenatal care or receive it late, which happens in about half of all CS cases, Dr. Kidd said.

Inconsistent, inadequate, or a total absence of prenatal care is “probably the biggest risk factor for vertical transmission, especially among high-risk populations, where there is an increased background prevalence of syphilis in childbearing women,” said Robert Maupin, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology in the section of maternal-fetal medicine at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

To complicate matters, women who receive no or inconsistent prenatal care face an increased risk for preterm birth, Dr. Maupin noted. So while a clinician might follow CDC recommendations that pregnant women with confirmed or suspected syphilis complete a course of long-acting penicillin G for at least 30 days or longer before the child is born, “the timing of being able to implement effective prevention and treatment prior to that 30-day window can sometimes be compromised by the fact that she ends up delivering prematurely,” he said. “If someone’s not adequately linked to consistent prenatal care, she may not complete that full course of prevention. Additionally, patterns of care are often fragmented, meaning that patients may go to one clinic or one provider, may not return, and may end up switching to a different clinic. That translates into a potential lag in implementing treatment or making a diagnosis in the first place, and that may be disruptive in the context of our attempted prevention measures.”

Precise reasons why some pregnant women in the United States receive no or inadequate prenatal care remain unclear.

“Anecdotally, in the West, I hear that women with drug abuse histories or drug abuse issues [are vulnerable], or they may be homeless or have mental health issues,” Dr. Kidd said. “In other areas of the country, people feel that it’s more of an insurance or access to care issue, but we don’t have data on that here at the CDC.”

Repeat screening

In 2015, a large analysis of women who were commercially-insured or Medicaid-insured found that more than 95% who received prenatal care were screened for syphilis at least once during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125[5]:1211-6). However, CDC data of CS cases shows that about 15% of their mothers are infected during pregnancy, which would occur after that first screening test.

“That’s where the repeat screening early in the third trimester and at delivery becomes the real issue,” Dr. Kidd said. “For high-risk women, including those who live in the high morbidity areas, they should be screened again later in pregnancy. Many ob.gyns. may not be aware of that recommendation, or may not be aware they’re in an area that does have a high syphilis morbidity, and that the pregnant women who are seeing them may be at increased risk of syphilis.”

Dr. Maupin, who is associate dean of diversity and community engagement at LSU Health Sciences Center, advised clinicians to view CS with the same sense of urgency that existed in previous years with perinatal HIV transmission.

“In the last decade and a half we’ve seen a substantial decline in perinatal HIV transmission because of intensive efforts on the public health side in terms of both screening and use of treatment,” he said. “If we look at this with a similar level of contemporary urgency, it will bear similar fruit over time. Additionally, from a maternal-fetal medicine standpoint, the more effectively we treat and/or control diseases and comorbidities prior to pregnancy, the less likely those things will have an adverse impact on the health and well-being of the newborn.”

Steps you can take to curb CS

In its “call to action” on syphilis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cited several practical ways that clinicians can combat the spread of congenital syphilis (CS).

1. Complete a sexual history for your patients. The CDC recommends following this with STD counseling for those at risk and contraception counseling for women at risk of unintended pregnancy.

2. Test all pregnant women for syphilis. This should be done at the first prenatal visit, with repeat screening for pregnant women at high risk and in areas of high prevalence at the beginning of the third trimester and again at delivery.

3. Treat women infected with syphilis immediately. If a woman has syphilis or suspected syphilis, she should be treated with long-acting penicillin G, especially if she is pregnant. CDC also calls for testing and treating the infected woman’s sex partner(s) to avoid reinfection.

4. Confirm syphilis testing at delivery. Before discharging the mother or infant from the hospital, check that the mother has been tested for syphilis at least once during pregnancy or at delivery. All women who deliver a stillborn infant should be tested for syphilis.

5. Report CS cases to the local or state health department within 24 hours.

Stop using codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, tramadol, and aspirin in women who are breastfeeding

In 2015 more than 30,000 deaths from opioid overdose were reported (FIGURE).1 More than 50% of the deaths were due to prescription opioids. The opioid crisis is a public health emergency and clinicians are diligently working to reduce both the number of opioid prescriptions and the doses prescribed per prescription.

In obstetrics, there is growing concern that narcotics used for the treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding may increase the risk of adverse effects in newborns, including excessive sedation and respiratory depression. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend against the use of codeine and tramadol in women who are breastfeeding because their newborns may have adverse reactions, including excessive sleepiness, difficulty breathing, and potentially fatal breathing problems.2–4 In addition, there is growing concern that the use of oxycodone and hydrocodone should also be limited in women who are breastfeeding. In this article, I discuss the rationale for these recommendations.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

Codeine

Codeine is metabolized to morphine by CYP2D6 and CYP2D7. Both codeine and morphine are excreted into breast milk. Some women are ultrarapid metabolizers of codeine because of high levels of CYP2D6, resulting in higher concentrations of morphine in their breast milk and their breast fed newborn.2,5 In many women who are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine, CYP2D6 gene duplication or multiplication is the cause of the increased enzyme activity.6 Genotyping can identify some women who are ultrarapid metabolizers, but it is not currently utilized widely in clinical practice.

In the United States approximately 5% of women express high levels of CYP2D6 and are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine.4 In Ethiopia as many as 29% of women are ultrarapid metabolizers.7 Newborn central nervous system (CNS) depression is the most common adverse effect of fetal ingestion of excessive codeine and mor-phine from breast milk and may present as sedation, apnea, bradycardia, or cyanosis.8 Multiple newborn fatalities have been re-ported in the literature when lactating mothers who were ultrarapid metabolizers took co-deine. The FDA and ACOG recommend against the use of codeine in lactating women.

Hydrocodone

Hydrocodone, a hydrogenated ketone derivative of codeine, is metabolized by CYP2D6 to hydromorphone. Both hydrocodone and hydromorphone are present in breast milk. In lactating mothers taking hydrocodone, up to 9% of the dose may be ingested by the breastfeeding newborn.9 There is concern that hydrocodone use by women who are breastfeeding and are ultrarapid metabolizers may cause increased fetal consumption of hydromorphone resulting in adverse outcomes in the newborn. The AAP cautions against the use of hydrocodone.2

Oxycodone

Oxycodone is metabolized by CYP2D6 to oxymorphone and is concentrated into breast milk.10 Oxymorphone is more than 10 times more potent than oxycodone. In one study of lactating women taking oxycodone, codeine, or acetaminophen, the rates of neonate CNS depression were 20%, 17%, and 0.5%, respectively.11 The authors concluded that for mothers who are breastfeeding oxycodone was no safer than codeine because both medications were associated with a high rate of depression in the neonate. Newborns who develop CNS depression from exposure to oxycodone in breast milk will respond to naloxone treatment.12 The AAP recommends against prescribing oxycodone for women who are breastfeeding their infants.2

In a recent communication, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) observed that in the United States, following cesarean delivery the majority of women receive oxycodone or hydrocodone.13 SOAP disagreed with the AAP recommendation against the use of oxycodone or hydrocodone in breastfeeding women. SOAP noted that all narcotics can produce adverse effects in newborns of breastfeeding women and that there are no good data that the prescription of oxycodone or hydrocodone is more risky than morphine or hydromorphone. However, based on their assessment of risk and benefit, pediatricians prioritize the use of acetaminophen and morphine and seldom use oxycodone or hydrocodone to treat moderate to severe pain in babies and children.

Tramadol

Tramadol is metabolized by CYP2D6 to O-desmethyltramadol. Both tramadol and O-desmethyltramadol are excreted into breast milk. In ultrarapid metabolizers, a greater concentration of O-desmethyltramadol is excreted into breast milk. The FDA reported that they identified no serious neonatal adverse events in the literature due to the use of tramadol by women who are breastfeeding. However, given that tramadol and its CYP2D6 metabolite enter breast milk and the potential for life-threatening respiratory de-pression in the infant, the FDA included tramadol in its warning about codeine.3

Codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and tramadol are all metabolized to more potent metabolites by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Individuals with low CYP2D6 activity, representing about 5% of the US population, cannot fully activate these narcotics. Hence they may not get adequate pain relief when treated with codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, or tramadol. Given their resistance to these medications they may first be placed on a higher dose of the narcotic and then switched from a high ineffective dose of one of the agents activated by CYP2D6 to a high dose of morphine or hydromorphone. This can be dangerous because they may then receive an excessive dose of narcotic and develop respiratory depression.14

Read about how other pain medications affect breast milk.

Aspirin

There are very little high quality data about the use of aspirin in women breastfeeding and the effect on the neonate. If a mother takes aspirin, the drug will enter breast milk. It is estimated that the nursing baby receives about 4% to 8% of the mother’s dose. The World Health Organization recommends that aspirin is compatible with breastfeeding in occasional small doses, but repeated administration of aspirin in normal doses should be avoided in women who are breastfeeding. If chronic or high-dose aspirin therapy is recommended, the infant should be monitored for side effects including metabolic acidosis15 and coagulation disorders.16 The National Reye’s Syndrome Foundation recommends against the use of aspirin in women who are breastfeeding because of the theoretical risk of triggering Reye syndrome.17 Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are recommended by the WHO for chronic treatment of pain during breastfeeding.16

Acetaminophen and ibuprofen

For the medication treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding, the WHO recommends the use of acetaminophen and ibuprofen.16 Acetaminophen is transferred from the maternal circulation into breast milk, but it is estimated that the dose to the nursing neonate is <0.3% of the maternal dose.18 In mothers taking ibuprofen 1600 mg daily, the concentration of ibuprofen in breast milk was below the level of laboratory detection (<1 mg/L).19 Ibuprofen treatment is thought to be safe for women who are breastfeeding because of its short half-life (2 hours), low excretion into milk, and few reported adverse effects in infants.

Morphine

Morphine is not metabolized by CYP2D6 and is excreted into breast milk. Many experts believe that women who are breastfeeding may take standard doses of oral morphine with few adverse effects in the newborn.20,21 For the treatment of moderate to severe pain in opioid-naive adults, morphine doses in the range of 10 mg orally every 4 hours up to 30 mg orally every 4 hours are prescribed. When using a solution of morphine, standard doses are 10 mg to 20 mg every 4 hours, as needed to treat pain. When using morphine tablets, standard doses are 15 mg to 30 mg every 4 hours. The WHO states that occasional doses of morphine are usually safe for women breastfeeding their newborn.16 The AAP recommends the use of morphine and hydromorphone when narcotic agents are needed to treat pain in breastfeeding women.2

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone, a hydrogenated ketone derivative of morphine, is not metabolized by CYP2D6 and is excreted into breast milk. There are limited data on the safety of hydromorphone during breastfeeding. Breast milk concentrations of hydromorphone are low, and an occasional dose is likely associated with few adverse effects in the breastfeeding newborn.22 For the treatment of moderate to severe pain in opioid-naive adults, hydromorphone doses in the range of 2 mg orally every 4 hours up to 4 mg orally every 4 hours are prescribed. Like all narcotics, hydromorphone can result in central nervous system depression. If a mother ingests sufficient quantities of hydromorphone, respiratory depression in the breastfeeding newborn can occur. In one case report, a nursing mother was taking hydromorphone 4 mg every 4 hours for pain following a cesarean delivery. On day 6 following birth, her newborn was lethargic and she brought the infant to an emergency room. In the emergency room the infant became apneic and was successfully treated with naloxone, suggesting anarcotic overdose due to the presence of hydromorphone in breast milk.23 Hydromorphone should only be used at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest time possible.

Related article:

Should coffee consumption be added as an adjunct to the postoperative care of gynecologic oncology patients?

The bottom line

Pediatricians seldom prescribe codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, or tramadol for the treatment of pain in newborns or children. Pediatricians generally use acetaminophen and morphine for the treatment of pain in newborns. Although data from large, high quality clinical trials are not available, expert opinion recommends that acetaminophen and ibuprofen should be prescribed as first-line medications for the treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding. Use of narcotics that are metabolized by CYP2D6 should be minimized or avoided in women who are breastfeeding. If narcotic medication is necessary, the lowest effective dose of morphine or hy-dromorphone should be prescribed for the shortest time possible. If morphine is prescribed to wo-men who are breastfeeding, they should be advised to observe their baby for signs of narcotic excess, including drowsiness, poor nursing, slow breathing, or low heart rate.

The goal of reducing morbidity and mortality from opioid use is a top public health priority. Obstetrician-gynecologists can contribute through the optimal use of opioid analgesics. Reducing the number of opioid prescriptions and the quantity of medication prescribed per prescription is an important first step in our effort to reduce opioid-related deaths.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Overdose Deaths—Number of Deaths from Opioid Drugs. National Institute on Drug Abuse website. . Update January 2017. Accessed September 14, 2017.

- Sachs HC; Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796–e809.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication. FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines and tramadol pain medicines in children; recommends against use in breastfeeding women. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm118113.htm. Published April 2017. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Practice advisory on codeine and tramadol for breast feeding women. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-on-Codeine-and-Tramadol-for-Breastfeeding-Women. Published April 27, 2017. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Madadi P, Shirazi F, Walter FG, Koren G. Establishing causality of CNS depression in breastfed infants following maternal codeine use. Paediatr Drugs. 2008;10(6):399–404.

- Langaee T, Hamadeh I, Chapman AB, Gums JG, Johnson JA. A novel simple method for determining CYP2D6 gene copy number and identifying allele(s) with duplication/multiplication. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0113808.

- Cascorbi I. Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome p4502D6: genetic background and clinical implication. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33(suppl 2):17–22.

- Naumburg EG, Meny RG. Breast milk opioids and neonatal apnea. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142(1):11–12.

- Sauberan JB, Anderson PO, Lane JR, et al. Breast milk hydrocodone and hydromorphone levels in mothers using hydrocodone for postpartum pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):611–617.

- Seaton S, Reeves M, McLean S. Oxycodone as a component of multimodal analgesia for lactating mothers after Cesarean section: relationships between maternal plasma, breast milk and neonatal plasma levels. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(3):181–185.

- Lam J, Kelly L, Ciszkowski C, et al. Central nervous system depression of neonates breastfed by mothers receiving oxycodone for postpartum analgesia. J Pediatr. 2012;160(1):33–37.e2.

- Timm NL. Maternal use of oxycodone resulting in opioid intoxication in her breastfed neonate. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):421–422.

- The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Comments in response to the ACOG/SMFM Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology website. https://soap.org/soap-response-acog-smfm-advisory.pdf. Published June 10, 2017. Accessed August 28, 2017.

- Banning AM. Respiratory depression following medication change from tramadol to morphine [article in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1999;161(47):6500–6501.

- Clark JH, Wilson WG. A 16-day old breast-fed infant with metabolic acidosis caused by salicylate. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20(1):53–54.

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding and maternal medication. Recommendations for drugs in the 11th WHO model list of essential drugs. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/62435/1/55732.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Reye’s syndrome. National Reye’s Syndrome Foundation website. http://www.reyessyndrome.org. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Berline CM Jr, Yaffe SJ, Ragni M. Disposition of acetaminophen in milk, saliva, and plasma of lactating women. Pediatr Pharmacol (New York). 1980;1(2):135–141.

- Townsend RJ, Benedetti TJ, Erickson SH, et al. Excretion of ibuprofen into breast milk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149(2):184–186.

- Spigset O, Hägg S. Analgesics and breast-feeding: safety considerations. Paediatr Drugs. 2000;2(3):223–238.

- Bar-OZ B, Bulkowstein M, Benyamini L, et al. Use of antibiotic and analgesic drugs during lactation. Drug Saf. 2003;26(13):925–935.

- Edwards JE, Rudy AC, Wermeling DP, Desai N, McNamara PJ. Hydromorphone transfer into breast milk after intranasal administration. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(2):153–158.

- Schultz ML, Kostic M, Kharasch S. A case of toxic breast-feeding [published online ahead of print January 6, 2017]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001009.

In 2015 more than 30,000 deaths from opioid overdose were reported (FIGURE).1 More than 50% of the deaths were due to prescription opioids. The opioid crisis is a public health emergency and clinicians are diligently working to reduce both the number of opioid prescriptions and the doses prescribed per prescription.

In obstetrics, there is growing concern that narcotics used for the treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding may increase the risk of adverse effects in newborns, including excessive sedation and respiratory depression. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend against the use of codeine and tramadol in women who are breastfeeding because their newborns may have adverse reactions, including excessive sleepiness, difficulty breathing, and potentially fatal breathing problems.2–4 In addition, there is growing concern that the use of oxycodone and hydrocodone should also be limited in women who are breastfeeding. In this article, I discuss the rationale for these recommendations.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

Codeine

Codeine is metabolized to morphine by CYP2D6 and CYP2D7. Both codeine and morphine are excreted into breast milk. Some women are ultrarapid metabolizers of codeine because of high levels of CYP2D6, resulting in higher concentrations of morphine in their breast milk and their breast fed newborn.2,5 In many women who are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine, CYP2D6 gene duplication or multiplication is the cause of the increased enzyme activity.6 Genotyping can identify some women who are ultrarapid metabolizers, but it is not currently utilized widely in clinical practice.

In the United States approximately 5% of women express high levels of CYP2D6 and are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine.4 In Ethiopia as many as 29% of women are ultrarapid metabolizers.7 Newborn central nervous system (CNS) depression is the most common adverse effect of fetal ingestion of excessive codeine and mor-phine from breast milk and may present as sedation, apnea, bradycardia, or cyanosis.8 Multiple newborn fatalities have been re-ported in the literature when lactating mothers who were ultrarapid metabolizers took co-deine. The FDA and ACOG recommend against the use of codeine in lactating women.

Hydrocodone

Hydrocodone, a hydrogenated ketone derivative of codeine, is metabolized by CYP2D6 to hydromorphone. Both hydrocodone and hydromorphone are present in breast milk. In lactating mothers taking hydrocodone, up to 9% of the dose may be ingested by the breastfeeding newborn.9 There is concern that hydrocodone use by women who are breastfeeding and are ultrarapid metabolizers may cause increased fetal consumption of hydromorphone resulting in adverse outcomes in the newborn. The AAP cautions against the use of hydrocodone.2

Oxycodone

Oxycodone is metabolized by CYP2D6 to oxymorphone and is concentrated into breast milk.10 Oxymorphone is more than 10 times more potent than oxycodone. In one study of lactating women taking oxycodone, codeine, or acetaminophen, the rates of neonate CNS depression were 20%, 17%, and 0.5%, respectively.11 The authors concluded that for mothers who are breastfeeding oxycodone was no safer than codeine because both medications were associated with a high rate of depression in the neonate. Newborns who develop CNS depression from exposure to oxycodone in breast milk will respond to naloxone treatment.12 The AAP recommends against prescribing oxycodone for women who are breastfeeding their infants.2

In a recent communication, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) observed that in the United States, following cesarean delivery the majority of women receive oxycodone or hydrocodone.13 SOAP disagreed with the AAP recommendation against the use of oxycodone or hydrocodone in breastfeeding women. SOAP noted that all narcotics can produce adverse effects in newborns of breastfeeding women and that there are no good data that the prescription of oxycodone or hydrocodone is more risky than morphine or hydromorphone. However, based on their assessment of risk and benefit, pediatricians prioritize the use of acetaminophen and morphine and seldom use oxycodone or hydrocodone to treat moderate to severe pain in babies and children.

Tramadol

Tramadol is metabolized by CYP2D6 to O-desmethyltramadol. Both tramadol and O-desmethyltramadol are excreted into breast milk. In ultrarapid metabolizers, a greater concentration of O-desmethyltramadol is excreted into breast milk. The FDA reported that they identified no serious neonatal adverse events in the literature due to the use of tramadol by women who are breastfeeding. However, given that tramadol and its CYP2D6 metabolite enter breast milk and the potential for life-threatening respiratory de-pression in the infant, the FDA included tramadol in its warning about codeine.3

Codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and tramadol are all metabolized to more potent metabolites by the CYP2D6 enzyme. Individuals with low CYP2D6 activity, representing about 5% of the US population, cannot fully activate these narcotics. Hence they may not get adequate pain relief when treated with codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, or tramadol. Given their resistance to these medications they may first be placed on a higher dose of the narcotic and then switched from a high ineffective dose of one of the agents activated by CYP2D6 to a high dose of morphine or hydromorphone. This can be dangerous because they may then receive an excessive dose of narcotic and develop respiratory depression.14

Read about how other pain medications affect breast milk.

Aspirin

There are very little high quality data about the use of aspirin in women breastfeeding and the effect on the neonate. If a mother takes aspirin, the drug will enter breast milk. It is estimated that the nursing baby receives about 4% to 8% of the mother’s dose. The World Health Organization recommends that aspirin is compatible with breastfeeding in occasional small doses, but repeated administration of aspirin in normal doses should be avoided in women who are breastfeeding. If chronic or high-dose aspirin therapy is recommended, the infant should be monitored for side effects including metabolic acidosis15 and coagulation disorders.16 The National Reye’s Syndrome Foundation recommends against the use of aspirin in women who are breastfeeding because of the theoretical risk of triggering Reye syndrome.17 Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are recommended by the WHO for chronic treatment of pain during breastfeeding.16

Acetaminophen and ibuprofen

For the medication treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding, the WHO recommends the use of acetaminophen and ibuprofen.16 Acetaminophen is transferred from the maternal circulation into breast milk, but it is estimated that the dose to the nursing neonate is <0.3% of the maternal dose.18 In mothers taking ibuprofen 1600 mg daily, the concentration of ibuprofen in breast milk was below the level of laboratory detection (<1 mg/L).19 Ibuprofen treatment is thought to be safe for women who are breastfeeding because of its short half-life (2 hours), low excretion into milk, and few reported adverse effects in infants.

Morphine

Morphine is not metabolized by CYP2D6 and is excreted into breast milk. Many experts believe that women who are breastfeeding may take standard doses of oral morphine with few adverse effects in the newborn.20,21 For the treatment of moderate to severe pain in opioid-naive adults, morphine doses in the range of 10 mg orally every 4 hours up to 30 mg orally every 4 hours are prescribed. When using a solution of morphine, standard doses are 10 mg to 20 mg every 4 hours, as needed to treat pain. When using morphine tablets, standard doses are 15 mg to 30 mg every 4 hours. The WHO states that occasional doses of morphine are usually safe for women breastfeeding their newborn.16 The AAP recommends the use of morphine and hydromorphone when narcotic agents are needed to treat pain in breastfeeding women.2

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone, a hydrogenated ketone derivative of morphine, is not metabolized by CYP2D6 and is excreted into breast milk. There are limited data on the safety of hydromorphone during breastfeeding. Breast milk concentrations of hydromorphone are low, and an occasional dose is likely associated with few adverse effects in the breastfeeding newborn.22 For the treatment of moderate to severe pain in opioid-naive adults, hydromorphone doses in the range of 2 mg orally every 4 hours up to 4 mg orally every 4 hours are prescribed. Like all narcotics, hydromorphone can result in central nervous system depression. If a mother ingests sufficient quantities of hydromorphone, respiratory depression in the breastfeeding newborn can occur. In one case report, a nursing mother was taking hydromorphone 4 mg every 4 hours for pain following a cesarean delivery. On day 6 following birth, her newborn was lethargic and she brought the infant to an emergency room. In the emergency room the infant became apneic and was successfully treated with naloxone, suggesting anarcotic overdose due to the presence of hydromorphone in breast milk.23 Hydromorphone should only be used at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest time possible.

Related article:

Should coffee consumption be added as an adjunct to the postoperative care of gynecologic oncology patients?

The bottom line

Pediatricians seldom prescribe codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, or tramadol for the treatment of pain in newborns or children. Pediatricians generally use acetaminophen and morphine for the treatment of pain in newborns. Although data from large, high quality clinical trials are not available, expert opinion recommends that acetaminophen and ibuprofen should be prescribed as first-line medications for the treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding. Use of narcotics that are metabolized by CYP2D6 should be minimized or avoided in women who are breastfeeding. If narcotic medication is necessary, the lowest effective dose of morphine or hy-dromorphone should be prescribed for the shortest time possible. If morphine is prescribed to wo-men who are breastfeeding, they should be advised to observe their baby for signs of narcotic excess, including drowsiness, poor nursing, slow breathing, or low heart rate.

The goal of reducing morbidity and mortality from opioid use is a top public health priority. Obstetrician-gynecologists can contribute through the optimal use of opioid analgesics. Reducing the number of opioid prescriptions and the quantity of medication prescribed per prescription is an important first step in our effort to reduce opioid-related deaths.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In 2015 more than 30,000 deaths from opioid overdose were reported (FIGURE).1 More than 50% of the deaths were due to prescription opioids. The opioid crisis is a public health emergency and clinicians are diligently working to reduce both the number of opioid prescriptions and the doses prescribed per prescription.

In obstetrics, there is growing concern that narcotics used for the treatment of pain in women who are breastfeeding may increase the risk of adverse effects in newborns, including excessive sedation and respiratory depression. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend against the use of codeine and tramadol in women who are breastfeeding because their newborns may have adverse reactions, including excessive sleepiness, difficulty breathing, and potentially fatal breathing problems.2–4 In addition, there is growing concern that the use of oxycodone and hydrocodone should also be limited in women who are breastfeeding. In this article, I discuss the rationale for these recommendations.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

Codeine

Codeine is metabolized to morphine by CYP2D6 and CYP2D7. Both codeine and morphine are excreted into breast milk. Some women are ultrarapid metabolizers of codeine because of high levels of CYP2D6, resulting in higher concentrations of morphine in their breast milk and their breast fed newborn.2,5 In many women who are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine, CYP2D6 gene duplication or multiplication is the cause of the increased enzyme activity.6 Genotyping can identify some women who are ultrarapid metabolizers, but it is not currently utilized widely in clinical practice.

In the United States approximately 5% of women express high levels of CYP2D6 and are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine.4 In Ethiopia as many as 29% of women are ultrarapid metabolizers.7 Newborn central nervous system (CNS) depression is the most common adverse effect of fetal ingestion of excessive codeine and mor-phine from breast milk and may present as sedation, apnea, bradycardia, or cyanosis.8 Multiple newborn fatalities have been re-ported in the literature when lactating mothers who were ultrarapid metabolizers took co-deine. The FDA and ACOG recommend against the use of codeine in lactating women.

Hydrocodone

Hydrocodone, a hydrogenated ketone derivative of codeine, is metabolized by CYP2D6 to hydromorphone. Both hydrocodone and hydromorphone are present in breast milk. In lactating mothers taking hydrocodone, up to 9% of the dose may be ingested by the breastfeeding newborn.9 There is concern that hydrocodone use by women who are breastfeeding and are ultrarapid metabolizers may cause increased fetal consumption of hydromorphone resulting in adverse outcomes in the newborn. The AAP cautions against the use of hydrocodone.2

Oxycodone

Oxycodone is metabolized by CYP2D6 to oxymorphone and is concentrated into breast milk.10 Oxymorphone is more than 10 times more potent than oxycodone. In one study of lactating women taking oxycodone, codeine, or acetaminophen, the rates of neonate CNS depression were 20%, 17%, and 0.5%, respectively.11 The authors concluded that for mothers who are breastfeeding oxycodone was no safer than codeine because both medications were associated with a high rate of depression in the neonate. Newborns who develop CNS depression from exposure to oxycodone in breast milk will respond to naloxone treatment.12 The AAP recommends against prescribing oxycodone for women who are breastfeeding their infants.2