User login

Obstetric perineal trauma prevented with SAFE PASSAGES

LAS VEGAS – Severe obstetric perineal trauma can often be avoided, even in operative deliveries, with the use of a suite of evidence-based interventions, according to findings from two prospective studies.

Collectively, these interventions resulted in significant reductions in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations in both military and civilian settings, according to research presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

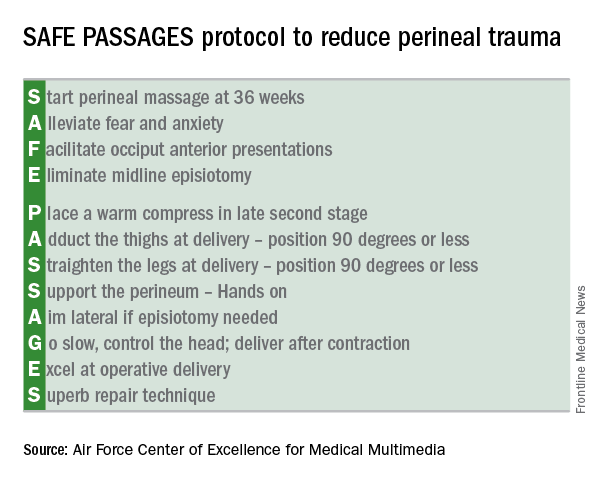

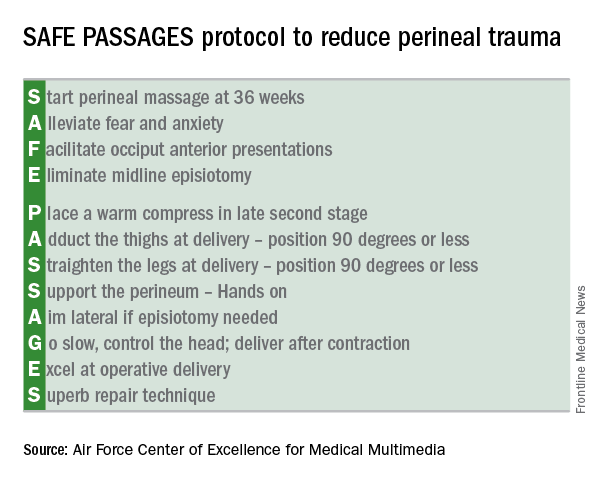

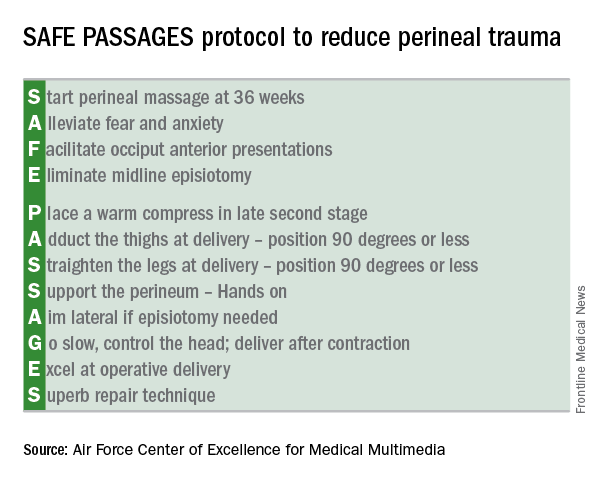

Developed by the Military Health System, the SAFE PASSAGES protocol brings together interventions that help achieve a controlled delivery over a relaxed perineum, minimizing risk for maternal obstetric trauma.

The entire SAFE PASSAGES curriculum is available free online.

Military results

In a prospective cohort design, 272,161 deliveries conducted before the 2011 implementation of the SAFE PASSAGES training program were compared with 451,446 postimplementation deliveries. Primary outcome measures were the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations during vaginal deliveries with and without instrumentation.

For vaginal deliveries with instrumentation within one service branch of the military medical system (Service X), implementation of SAFE PASSAGES training was associated with a 63.6% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, compared with preintervention rates (P less than .001).

The other two services – Service Y and Service Z – received just administrative encouragement and saw a 15.5% reduction and a 12.6% increase in significant obstetric trauma when instrumentation-assisted vaginal deliveries were performed (P = .04 and .30, respectively), according to Merlin Fausett, MD, an ob.gyn. currently in private practice in Missoula, Mont., who led the SAFE PASSAGES efforts before retiring from the Air Force.

For vaginal deliveries performed without instrumentation, the rates also fell for Service X, which saw a 41.8% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations (P less than .002). The other services saw a 16% increase and a 12% decrease with administrative encouragement alone (P = .48 and .08, respectively).

Though the military training program had initially been conducted in person, Dr. Fausett said that the program was switched to web-based simulations because of budget constraints. Efficacy remained high, he said.

Civilian results

When the team-based simulation that formed the core of the military SAFE PASSAGES training was rolled out in a large civilian health care system, similar improvements were seen.

Over an 18-month period, 675 nurses, midwives, and physicians received simulation-based training in the SAFE PASSAGES techniques. Overall, severe perineal laceration rates in the civilian facilities were down by 38.53% after adoption of SAFE PASSAGES.

“We have really achieved a culture shift,” said Emily Marko, MD, an ob.gyn. and clerkship director for the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine Inova Campus in Falls Church, Va. “This really requires the whole delivery team to get involved: the patient, the patient’s support person, the nurses, any midwives or doulas that are there,” she said. “To tell you the truth, this whole program is about paying attention to the perineum, and not rushing delivery.”

Posttraining surveys showed that 95% of providers had changed their practice patterns after training in the delivery strategies.

Interventions

The emphasis in SAFE PASSAGES is to achieve a slow, controlled delivery and to minimize strain on the perineum by means of conditioning, relaxation, and positioning.

The first intervention is to have pregnant women “start” perineal massage at 36 weeks. Next, providers are urged to “alleviate” maternal fears. Providers are also encouraged to recognize posterior presentations, and to “facilitate” an anterior presentation through rotation. The “E” in SAFE stands for “eliminating” midline episiotomies – one of the more difficult practices to shift, according to both Dr. Fausett and Dr. Marko.

Despite a wealth of evidence showing fewer anal sphincter disruptions and better overall outcomes, it’s been difficult to convince U.S. physicians to adopt the mediolateral episiotomy technique that’s widely adopted in Europe, they said.

The protocol calls for “placing” a warm compress over the perineum during labor to encourage relaxation and stretching. Though prenatal perineal massage is encouraged, Dr. Marko said that intrapartum massage is not, as it’s thought to contribute to edema when performed during labor.

During delivery, leg positioning to reduce stretching of the perineum is also important: The thighs should be “adducted” to 90 degrees or less, and “straightened” to 90 degrees or less as well. Though this can make “a bit of a tight space” for the delivering physician, Dr. Marko said, it really “helps engage the pelvic muscles to support the perineum,” and a few technique adjustments make the position workable.

The perineum should be “supported” during delivery by one hand of the delivering practitioner forming a U shape with the thumb and forefinger, with the first webspace overlying the posterior fourchette. Reinforcing the importance of avoiding a midline episiotomy, the “A” of passages stands for “aiming” lateral when an episiotomy is needed.

During the delivery, the physician should “go” slow, controlling the head and delivering after, rather than during, a contraction.

It’s important to be comfortable with forceps deliveries and vacuum extractions in order to minimize both maternal and fetal trauma; thus, physicians should “excel” at operative delivery, according to the protocol.

The SAFE PASSAGES website includes comprehensive explanations, with graphics and demonstrations using a model, of both forceps and vacuum delivery techniques.

Finally, should a laceration occur, the SAFE PASSAGES website provides detailed explanations of repair techniques, with an emphasis on understanding perineal, vaginal, and anal anatomy so “superb” approximation and repair can be achieved.

Though obstetric trauma may not be life threatening, it’s still associated with significant and persistent morbidity. When perineal and pelvic floor trauma disrupts the anal sphincter, anal incontinence can occur, even after a meticulous attempt at repair. Perineal and pelvic floor trauma can result in a host of urinary and sexual problems as well.

After the intensive training period, Dr. Fausett said, “laceration rates can creep back up if people forget about it and stop paying attention to it. But where it becomes a culture, the rates can stay low. Standardized training can reduce perineal trauma rates without increasing cesarean or neonatal trauma rates,” Dr. Fausett said.

Dr. Marko and Dr. Fausett reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Severe obstetric perineal trauma can often be avoided, even in operative deliveries, with the use of a suite of evidence-based interventions, according to findings from two prospective studies.

Collectively, these interventions resulted in significant reductions in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations in both military and civilian settings, according to research presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

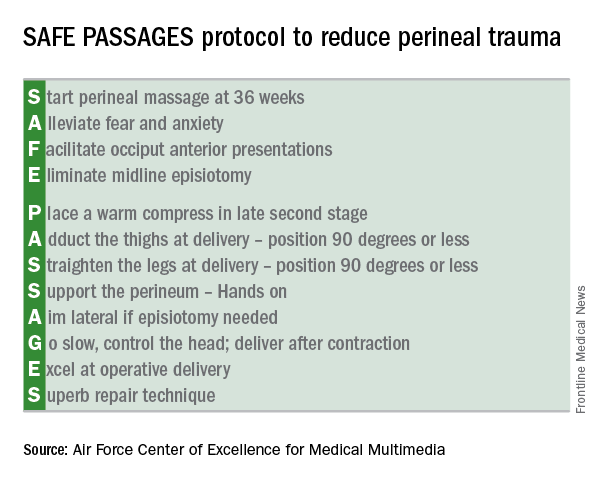

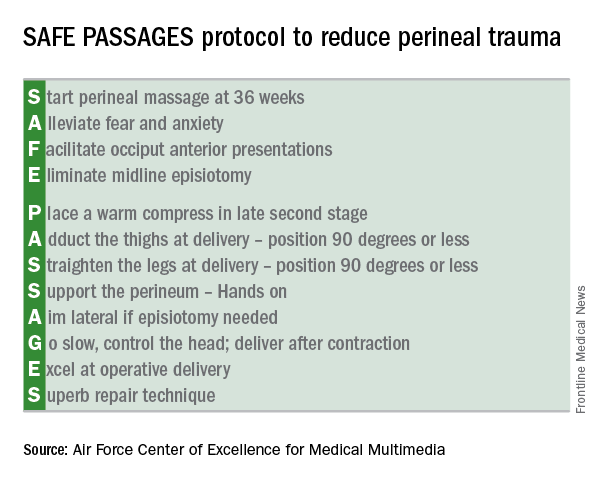

Developed by the Military Health System, the SAFE PASSAGES protocol brings together interventions that help achieve a controlled delivery over a relaxed perineum, minimizing risk for maternal obstetric trauma.

The entire SAFE PASSAGES curriculum is available free online.

Military results

In a prospective cohort design, 272,161 deliveries conducted before the 2011 implementation of the SAFE PASSAGES training program were compared with 451,446 postimplementation deliveries. Primary outcome measures were the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations during vaginal deliveries with and without instrumentation.

For vaginal deliveries with instrumentation within one service branch of the military medical system (Service X), implementation of SAFE PASSAGES training was associated with a 63.6% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, compared with preintervention rates (P less than .001).

The other two services – Service Y and Service Z – received just administrative encouragement and saw a 15.5% reduction and a 12.6% increase in significant obstetric trauma when instrumentation-assisted vaginal deliveries were performed (P = .04 and .30, respectively), according to Merlin Fausett, MD, an ob.gyn. currently in private practice in Missoula, Mont., who led the SAFE PASSAGES efforts before retiring from the Air Force.

For vaginal deliveries performed without instrumentation, the rates also fell for Service X, which saw a 41.8% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations (P less than .002). The other services saw a 16% increase and a 12% decrease with administrative encouragement alone (P = .48 and .08, respectively).

Though the military training program had initially been conducted in person, Dr. Fausett said that the program was switched to web-based simulations because of budget constraints. Efficacy remained high, he said.

Civilian results

When the team-based simulation that formed the core of the military SAFE PASSAGES training was rolled out in a large civilian health care system, similar improvements were seen.

Over an 18-month period, 675 nurses, midwives, and physicians received simulation-based training in the SAFE PASSAGES techniques. Overall, severe perineal laceration rates in the civilian facilities were down by 38.53% after adoption of SAFE PASSAGES.

“We have really achieved a culture shift,” said Emily Marko, MD, an ob.gyn. and clerkship director for the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine Inova Campus in Falls Church, Va. “This really requires the whole delivery team to get involved: the patient, the patient’s support person, the nurses, any midwives or doulas that are there,” she said. “To tell you the truth, this whole program is about paying attention to the perineum, and not rushing delivery.”

Posttraining surveys showed that 95% of providers had changed their practice patterns after training in the delivery strategies.

Interventions

The emphasis in SAFE PASSAGES is to achieve a slow, controlled delivery and to minimize strain on the perineum by means of conditioning, relaxation, and positioning.

The first intervention is to have pregnant women “start” perineal massage at 36 weeks. Next, providers are urged to “alleviate” maternal fears. Providers are also encouraged to recognize posterior presentations, and to “facilitate” an anterior presentation through rotation. The “E” in SAFE stands for “eliminating” midline episiotomies – one of the more difficult practices to shift, according to both Dr. Fausett and Dr. Marko.

Despite a wealth of evidence showing fewer anal sphincter disruptions and better overall outcomes, it’s been difficult to convince U.S. physicians to adopt the mediolateral episiotomy technique that’s widely adopted in Europe, they said.

The protocol calls for “placing” a warm compress over the perineum during labor to encourage relaxation and stretching. Though prenatal perineal massage is encouraged, Dr. Marko said that intrapartum massage is not, as it’s thought to contribute to edema when performed during labor.

During delivery, leg positioning to reduce stretching of the perineum is also important: The thighs should be “adducted” to 90 degrees or less, and “straightened” to 90 degrees or less as well. Though this can make “a bit of a tight space” for the delivering physician, Dr. Marko said, it really “helps engage the pelvic muscles to support the perineum,” and a few technique adjustments make the position workable.

The perineum should be “supported” during delivery by one hand of the delivering practitioner forming a U shape with the thumb and forefinger, with the first webspace overlying the posterior fourchette. Reinforcing the importance of avoiding a midline episiotomy, the “A” of passages stands for “aiming” lateral when an episiotomy is needed.

During the delivery, the physician should “go” slow, controlling the head and delivering after, rather than during, a contraction.

It’s important to be comfortable with forceps deliveries and vacuum extractions in order to minimize both maternal and fetal trauma; thus, physicians should “excel” at operative delivery, according to the protocol.

The SAFE PASSAGES website includes comprehensive explanations, with graphics and demonstrations using a model, of both forceps and vacuum delivery techniques.

Finally, should a laceration occur, the SAFE PASSAGES website provides detailed explanations of repair techniques, with an emphasis on understanding perineal, vaginal, and anal anatomy so “superb” approximation and repair can be achieved.

Though obstetric trauma may not be life threatening, it’s still associated with significant and persistent morbidity. When perineal and pelvic floor trauma disrupts the anal sphincter, anal incontinence can occur, even after a meticulous attempt at repair. Perineal and pelvic floor trauma can result in a host of urinary and sexual problems as well.

After the intensive training period, Dr. Fausett said, “laceration rates can creep back up if people forget about it and stop paying attention to it. But where it becomes a culture, the rates can stay low. Standardized training can reduce perineal trauma rates without increasing cesarean or neonatal trauma rates,” Dr. Fausett said.

Dr. Marko and Dr. Fausett reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Severe obstetric perineal trauma can often be avoided, even in operative deliveries, with the use of a suite of evidence-based interventions, according to findings from two prospective studies.

Collectively, these interventions resulted in significant reductions in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations in both military and civilian settings, according to research presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

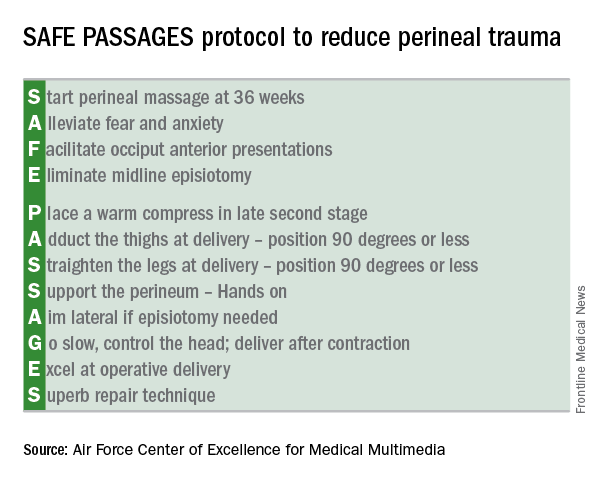

Developed by the Military Health System, the SAFE PASSAGES protocol brings together interventions that help achieve a controlled delivery over a relaxed perineum, minimizing risk for maternal obstetric trauma.

The entire SAFE PASSAGES curriculum is available free online.

Military results

In a prospective cohort design, 272,161 deliveries conducted before the 2011 implementation of the SAFE PASSAGES training program were compared with 451,446 postimplementation deliveries. Primary outcome measures were the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations during vaginal deliveries with and without instrumentation.

For vaginal deliveries with instrumentation within one service branch of the military medical system (Service X), implementation of SAFE PASSAGES training was associated with a 63.6% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, compared with preintervention rates (P less than .001).

The other two services – Service Y and Service Z – received just administrative encouragement and saw a 15.5% reduction and a 12.6% increase in significant obstetric trauma when instrumentation-assisted vaginal deliveries were performed (P = .04 and .30, respectively), according to Merlin Fausett, MD, an ob.gyn. currently in private practice in Missoula, Mont., who led the SAFE PASSAGES efforts before retiring from the Air Force.

For vaginal deliveries performed without instrumentation, the rates also fell for Service X, which saw a 41.8% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations (P less than .002). The other services saw a 16% increase and a 12% decrease with administrative encouragement alone (P = .48 and .08, respectively).

Though the military training program had initially been conducted in person, Dr. Fausett said that the program was switched to web-based simulations because of budget constraints. Efficacy remained high, he said.

Civilian results

When the team-based simulation that formed the core of the military SAFE PASSAGES training was rolled out in a large civilian health care system, similar improvements were seen.

Over an 18-month period, 675 nurses, midwives, and physicians received simulation-based training in the SAFE PASSAGES techniques. Overall, severe perineal laceration rates in the civilian facilities were down by 38.53% after adoption of SAFE PASSAGES.

“We have really achieved a culture shift,” said Emily Marko, MD, an ob.gyn. and clerkship director for the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine Inova Campus in Falls Church, Va. “This really requires the whole delivery team to get involved: the patient, the patient’s support person, the nurses, any midwives or doulas that are there,” she said. “To tell you the truth, this whole program is about paying attention to the perineum, and not rushing delivery.”

Posttraining surveys showed that 95% of providers had changed their practice patterns after training in the delivery strategies.

Interventions

The emphasis in SAFE PASSAGES is to achieve a slow, controlled delivery and to minimize strain on the perineum by means of conditioning, relaxation, and positioning.

The first intervention is to have pregnant women “start” perineal massage at 36 weeks. Next, providers are urged to “alleviate” maternal fears. Providers are also encouraged to recognize posterior presentations, and to “facilitate” an anterior presentation through rotation. The “E” in SAFE stands for “eliminating” midline episiotomies – one of the more difficult practices to shift, according to both Dr. Fausett and Dr. Marko.

Despite a wealth of evidence showing fewer anal sphincter disruptions and better overall outcomes, it’s been difficult to convince U.S. physicians to adopt the mediolateral episiotomy technique that’s widely adopted in Europe, they said.

The protocol calls for “placing” a warm compress over the perineum during labor to encourage relaxation and stretching. Though prenatal perineal massage is encouraged, Dr. Marko said that intrapartum massage is not, as it’s thought to contribute to edema when performed during labor.

During delivery, leg positioning to reduce stretching of the perineum is also important: The thighs should be “adducted” to 90 degrees or less, and “straightened” to 90 degrees or less as well. Though this can make “a bit of a tight space” for the delivering physician, Dr. Marko said, it really “helps engage the pelvic muscles to support the perineum,” and a few technique adjustments make the position workable.

The perineum should be “supported” during delivery by one hand of the delivering practitioner forming a U shape with the thumb and forefinger, with the first webspace overlying the posterior fourchette. Reinforcing the importance of avoiding a midline episiotomy, the “A” of passages stands for “aiming” lateral when an episiotomy is needed.

During the delivery, the physician should “go” slow, controlling the head and delivering after, rather than during, a contraction.

It’s important to be comfortable with forceps deliveries and vacuum extractions in order to minimize both maternal and fetal trauma; thus, physicians should “excel” at operative delivery, according to the protocol.

The SAFE PASSAGES website includes comprehensive explanations, with graphics and demonstrations using a model, of both forceps and vacuum delivery techniques.

Finally, should a laceration occur, the SAFE PASSAGES website provides detailed explanations of repair techniques, with an emphasis on understanding perineal, vaginal, and anal anatomy so “superb” approximation and repair can be achieved.

Though obstetric trauma may not be life threatening, it’s still associated with significant and persistent morbidity. When perineal and pelvic floor trauma disrupts the anal sphincter, anal incontinence can occur, even after a meticulous attempt at repair. Perineal and pelvic floor trauma can result in a host of urinary and sexual problems as well.

After the intensive training period, Dr. Fausett said, “laceration rates can creep back up if people forget about it and stop paying attention to it. But where it becomes a culture, the rates can stay low. Standardized training can reduce perineal trauma rates without increasing cesarean or neonatal trauma rates,” Dr. Fausett said.

Dr. Marko and Dr. Fausett reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations dropped by as much as 64% after SAFE PASSAGES training.

Data source: Prospective cohort study of 723,607 military deliveries; prospective study of 675 providers involved in labor and delivery at four civilian hospitals in a large health care system.

Disclosures: Dr. Marko and Dr. Fausett reported having no conflicts of interest.

Fewer infant deaths during ‘39-week rule’ era

LAS VEGAS – Closer adherence by U.S. physicians to the “39-week rule” for elective deliveries appears to have cut net neonatal mortality in an analysis of more than 14 million deliveries during 2008-2012.

This net drop in mortality occurred despite a concurrent rise in stillbirths, Rachel A. Pilliod, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The increase in stillbirths was more than counterbalanced by a larger drop in infant deaths during the same period.

“It’s not a one-to-one trade, where each stillbirth corresponds to an infant death that is subsequently avoided. It’s hard to make this trade-off when counseling parents,” she said. “We think that there has been some effect from increasing gestational age on reducing overall mortality, but we need to do even better on identifying high risk [deliveries].”

What is “unacceptable,” Dr. Pilliod said, is if a woman needs an earlier delivery but it gets pushed back because of a poorly informed application of the 39-week rule.

Her study used data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics on U.S. deliveries each year, focusing on pregnancies that were singletons and nonanomalous.

She compared the 7,388,782 deliveries during 2008 and 2009 and 6,980,962 births during 2011 and 2012, selecting the 2-year time periods on either side of the Joint Commission’s 2010 adoption of a quality measure aimed at decreasing elective deliveries prior to 39 weeks gestation.

The Joint Commission’s action had its desired effect. Deliveries at 39 weeks jumped from 36% of all elective births in 2008 and 2009 to 43% in 2011 and 2012, while deliveries at 38 weeks show the biggest drop, from 22% to 20%, Dr. Pilliod reported (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.959).

Concurrent with the rise in 39-week births and a drop in neonates with shorter gestation times, the incidence of stillbirths rose from 9.32 per 10,000 births in 2008 and 2009 to 10.15, an increase of 0.83 per 10,000 births.

But during the same periods the incidence of infant deaths fell, from 20.63 per 10,000 births in 2008 and 2009 to 19.0 in 2011 and 2012, a reduction of 1.63 per 10,000. Overall the stillbirth and infant death data combined for a net mortality reduction of 0.8 per 10,000 births.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Closer adherence by U.S. physicians to the “39-week rule” for elective deliveries appears to have cut net neonatal mortality in an analysis of more than 14 million deliveries during 2008-2012.

This net drop in mortality occurred despite a concurrent rise in stillbirths, Rachel A. Pilliod, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The increase in stillbirths was more than counterbalanced by a larger drop in infant deaths during the same period.

“It’s not a one-to-one trade, where each stillbirth corresponds to an infant death that is subsequently avoided. It’s hard to make this trade-off when counseling parents,” she said. “We think that there has been some effect from increasing gestational age on reducing overall mortality, but we need to do even better on identifying high risk [deliveries].”

What is “unacceptable,” Dr. Pilliod said, is if a woman needs an earlier delivery but it gets pushed back because of a poorly informed application of the 39-week rule.

Her study used data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics on U.S. deliveries each year, focusing on pregnancies that were singletons and nonanomalous.

She compared the 7,388,782 deliveries during 2008 and 2009 and 6,980,962 births during 2011 and 2012, selecting the 2-year time periods on either side of the Joint Commission’s 2010 adoption of a quality measure aimed at decreasing elective deliveries prior to 39 weeks gestation.

The Joint Commission’s action had its desired effect. Deliveries at 39 weeks jumped from 36% of all elective births in 2008 and 2009 to 43% in 2011 and 2012, while deliveries at 38 weeks show the biggest drop, from 22% to 20%, Dr. Pilliod reported (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.959).

Concurrent with the rise in 39-week births and a drop in neonates with shorter gestation times, the incidence of stillbirths rose from 9.32 per 10,000 births in 2008 and 2009 to 10.15, an increase of 0.83 per 10,000 births.

But during the same periods the incidence of infant deaths fell, from 20.63 per 10,000 births in 2008 and 2009 to 19.0 in 2011 and 2012, a reduction of 1.63 per 10,000. Overall the stillbirth and infant death data combined for a net mortality reduction of 0.8 per 10,000 births.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Closer adherence by U.S. physicians to the “39-week rule” for elective deliveries appears to have cut net neonatal mortality in an analysis of more than 14 million deliveries during 2008-2012.

This net drop in mortality occurred despite a concurrent rise in stillbirths, Rachel A. Pilliod, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The increase in stillbirths was more than counterbalanced by a larger drop in infant deaths during the same period.

“It’s not a one-to-one trade, where each stillbirth corresponds to an infant death that is subsequently avoided. It’s hard to make this trade-off when counseling parents,” she said. “We think that there has been some effect from increasing gestational age on reducing overall mortality, but we need to do even better on identifying high risk [deliveries].”

What is “unacceptable,” Dr. Pilliod said, is if a woman needs an earlier delivery but it gets pushed back because of a poorly informed application of the 39-week rule.

Her study used data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics on U.S. deliveries each year, focusing on pregnancies that were singletons and nonanomalous.

She compared the 7,388,782 deliveries during 2008 and 2009 and 6,980,962 births during 2011 and 2012, selecting the 2-year time periods on either side of the Joint Commission’s 2010 adoption of a quality measure aimed at decreasing elective deliveries prior to 39 weeks gestation.

The Joint Commission’s action had its desired effect. Deliveries at 39 weeks jumped from 36% of all elective births in 2008 and 2009 to 43% in 2011 and 2012, while deliveries at 38 weeks show the biggest drop, from 22% to 20%, Dr. Pilliod reported (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.959).

Concurrent with the rise in 39-week births and a drop in neonates with shorter gestation times, the incidence of stillbirths rose from 9.32 per 10,000 births in 2008 and 2009 to 10.15, an increase of 0.83 per 10,000 births.

But during the same periods the incidence of infant deaths fell, from 20.63 per 10,000 births in 2008 and 2009 to 19.0 in 2011 and 2012, a reduction of 1.63 per 10,000. Overall the stillbirth and infant death data combined for a net mortality reduction of 0.8 per 10,000 births.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Net mortality dropped by 0.8 per 10,000 births from 2008 and 2009 to 2011 and 2012.

Data source: Review of U.S. birth records from the National Center for Health Statistics during 2008-2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Pilliod reported having no financial disclosures.

More risk factors boost mortality in home births

LAS VEGAS – Analysis of nearly 13 million U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013 identified two new, significant dangers posed to neonates delivered by planned home births: nulliparous pregnancies and deliveries at 41 weeks gestational age or older.

Both conditions linked with a substantially increased risk for neonatal mortality, compared with babies delivered at a hospital, either by a nurse midwife or a physician, said Amos Grünebaum, MD, at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The critical difference between a home birth–like setting at a hospital and home birth in the field is distance from a hospital when emergency care is needed, he said.

“Women want less intervention during delivery and should get less intervention,” but a midwife run, home birth–like clinic should operate adjacent to a hospital able to handle obstetrical and neonatal emergencies, Dr. Grünebaum said in an interview. “Women need to understand the risks of home births.”

He and his associates used data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on 12,953,671 U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013 for singleton, nonanomalous neonates with at least 37 weeks gestation at birth and weighing at least 2,500 grams. The total included 91% hospital deliveries by a physician, 8% hospital deliveries by a nurse-midwife, and 96,815 home births or 0.75% of U.S. deliveries during this period. Despite that low percentage, the number of U.S. home births nearly tripled from 2007 to 2015, he noted.

The rate of neonatal deaths for each 10,000 live births was 3 among infants delivered by nurse midwives at hospitals, 5 for infants delivered by physicians at hospitals, and 12 for infants delivered by home births. The standard mortality ratio was 66% higher for physicians at hospitals, compared with nurse-midwives at hospitals, because physicians handle higher-risk deliveries, and more than fourfold higher for home births, compared with hospital deliveries by nurse-midwives, Dr. Grünebaum reported.

Further analysis showed that the death rate per 10,000 neonates for pregnancies that continued to a gestational age of 41 weeks or more was 17.2, and for deliveries among nulliparous women, neonatal mortality was 22.5 deaths per 10,000 births. These rates were in the same ballpark as three conditions cited by an ACOG committee in a 2016 report as contraindications for home birth: prior cesarean delivery, which had home birth mortality of 18.9 per 10,000 neonates in the current study, multiple gestations, and breach presentation, with home birth mortality in the current study of 127.5 per 10,000.Maternal age of 35 years or greater at the time of delivery linked with a death rate of 13.6 per 10,000 births, a rate that Dr. Grünebaum did not consider high enough to specifically label it a contraindication to home birth. But Dr. Grünebaum took a dim view of home births in general. For any type of pregnancy, a birth center not adjacent to a hospital is “unprofessional,” he declared.

A journal article with this report also appeared online (Am J Ob Gyn. 2017 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.012).

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Analysis of nearly 13 million U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013 identified two new, significant dangers posed to neonates delivered by planned home births: nulliparous pregnancies and deliveries at 41 weeks gestational age or older.

Both conditions linked with a substantially increased risk for neonatal mortality, compared with babies delivered at a hospital, either by a nurse midwife or a physician, said Amos Grünebaum, MD, at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The critical difference between a home birth–like setting at a hospital and home birth in the field is distance from a hospital when emergency care is needed, he said.

“Women want less intervention during delivery and should get less intervention,” but a midwife run, home birth–like clinic should operate adjacent to a hospital able to handle obstetrical and neonatal emergencies, Dr. Grünebaum said in an interview. “Women need to understand the risks of home births.”

He and his associates used data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on 12,953,671 U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013 for singleton, nonanomalous neonates with at least 37 weeks gestation at birth and weighing at least 2,500 grams. The total included 91% hospital deliveries by a physician, 8% hospital deliveries by a nurse-midwife, and 96,815 home births or 0.75% of U.S. deliveries during this period. Despite that low percentage, the number of U.S. home births nearly tripled from 2007 to 2015, he noted.

The rate of neonatal deaths for each 10,000 live births was 3 among infants delivered by nurse midwives at hospitals, 5 for infants delivered by physicians at hospitals, and 12 for infants delivered by home births. The standard mortality ratio was 66% higher for physicians at hospitals, compared with nurse-midwives at hospitals, because physicians handle higher-risk deliveries, and more than fourfold higher for home births, compared with hospital deliveries by nurse-midwives, Dr. Grünebaum reported.

Further analysis showed that the death rate per 10,000 neonates for pregnancies that continued to a gestational age of 41 weeks or more was 17.2, and for deliveries among nulliparous women, neonatal mortality was 22.5 deaths per 10,000 births. These rates were in the same ballpark as three conditions cited by an ACOG committee in a 2016 report as contraindications for home birth: prior cesarean delivery, which had home birth mortality of 18.9 per 10,000 neonates in the current study, multiple gestations, and breach presentation, with home birth mortality in the current study of 127.5 per 10,000.Maternal age of 35 years or greater at the time of delivery linked with a death rate of 13.6 per 10,000 births, a rate that Dr. Grünebaum did not consider high enough to specifically label it a contraindication to home birth. But Dr. Grünebaum took a dim view of home births in general. For any type of pregnancy, a birth center not adjacent to a hospital is “unprofessional,” he declared.

A journal article with this report also appeared online (Am J Ob Gyn. 2017 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.012).

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Analysis of nearly 13 million U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013 identified two new, significant dangers posed to neonates delivered by planned home births: nulliparous pregnancies and deliveries at 41 weeks gestational age or older.

Both conditions linked with a substantially increased risk for neonatal mortality, compared with babies delivered at a hospital, either by a nurse midwife or a physician, said Amos Grünebaum, MD, at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The critical difference between a home birth–like setting at a hospital and home birth in the field is distance from a hospital when emergency care is needed, he said.

“Women want less intervention during delivery and should get less intervention,” but a midwife run, home birth–like clinic should operate adjacent to a hospital able to handle obstetrical and neonatal emergencies, Dr. Grünebaum said in an interview. “Women need to understand the risks of home births.”

He and his associates used data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on 12,953,671 U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013 for singleton, nonanomalous neonates with at least 37 weeks gestation at birth and weighing at least 2,500 grams. The total included 91% hospital deliveries by a physician, 8% hospital deliveries by a nurse-midwife, and 96,815 home births or 0.75% of U.S. deliveries during this period. Despite that low percentage, the number of U.S. home births nearly tripled from 2007 to 2015, he noted.

The rate of neonatal deaths for each 10,000 live births was 3 among infants delivered by nurse midwives at hospitals, 5 for infants delivered by physicians at hospitals, and 12 for infants delivered by home births. The standard mortality ratio was 66% higher for physicians at hospitals, compared with nurse-midwives at hospitals, because physicians handle higher-risk deliveries, and more than fourfold higher for home births, compared with hospital deliveries by nurse-midwives, Dr. Grünebaum reported.

Further analysis showed that the death rate per 10,000 neonates for pregnancies that continued to a gestational age of 41 weeks or more was 17.2, and for deliveries among nulliparous women, neonatal mortality was 22.5 deaths per 10,000 births. These rates were in the same ballpark as three conditions cited by an ACOG committee in a 2016 report as contraindications for home birth: prior cesarean delivery, which had home birth mortality of 18.9 per 10,000 neonates in the current study, multiple gestations, and breach presentation, with home birth mortality in the current study of 127.5 per 10,000.Maternal age of 35 years or greater at the time of delivery linked with a death rate of 13.6 per 10,000 births, a rate that Dr. Grünebaum did not consider high enough to specifically label it a contraindication to home birth. But Dr. Grünebaum took a dim view of home births in general. For any type of pregnancy, a birth center not adjacent to a hospital is “unprofessional,” he declared.

A journal article with this report also appeared online (Am J Ob Gyn. 2017 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.012).

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Home birth neonatal mortality per 10,000 births was 22.5 from nulliparous pregnancies and 17.2 with 41 weeks gestational age or greater.

Data source: Analysis of data from 12,953,671 selected full-term U.S. deliveries during 2009-2013, collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosures: Dr. Grünebaum had no disclosures.

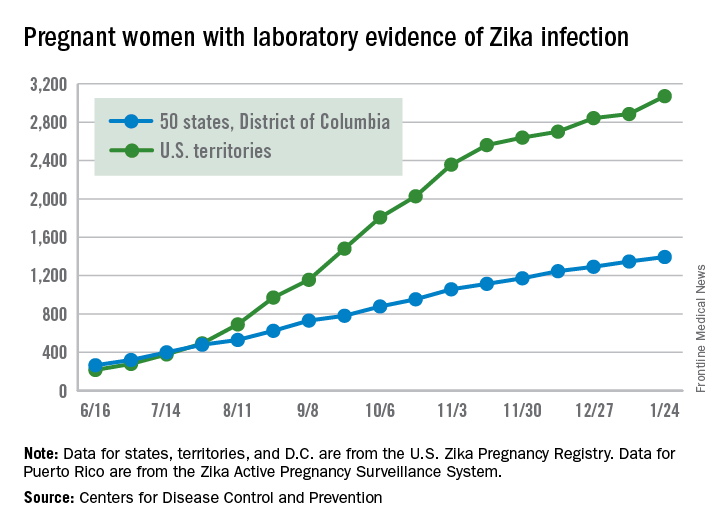

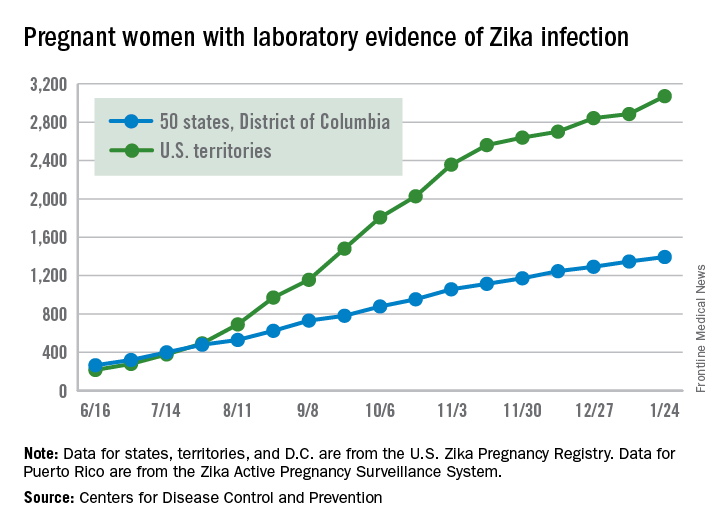

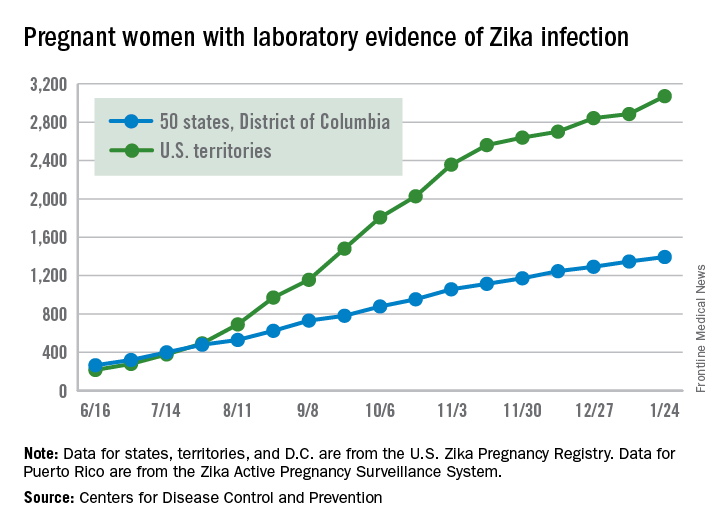

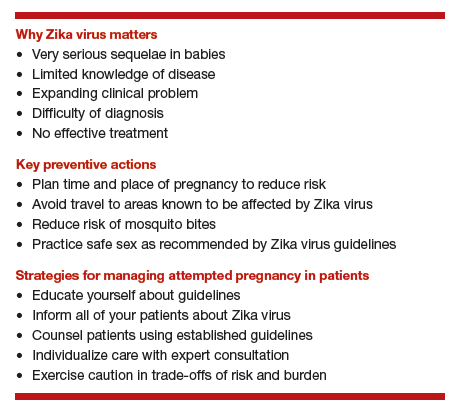

New Zika-infected pregnancies down for most of United States

New cases of Zika infection in pregnant women were down again for the 50 states over the 2-week reporting period ending Jan. 24, but U.S. territories saw a big increase, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It is important to note, however, that Puerto Rico, where most U.S. Zika cases are occurring, has been retroactively reporting cases for months, which can result in larger-than-normal increases.

The territories had 186 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection for the 2 weeks ending Jan. 24, compared with 43 for the previous 2-week period. The corresponding numbers for the 50 states and the District of Columbia were 47 (Jan. 24) and 55 (Jan. 10), the CDC data show.

So far for 2016-2017, there have been 4,465 pregnant women reported to have Zika virus infection in the United States: 3,071 in the territories and 1,394 in the 50 states and D.C., according to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry (states, territories, and the District of Columbia) and the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System (Puerto Rico).

Of the nearly 1,400 state/D.C. Zika-infected pregnancies, 999 have been completed, with 38 infants born with birth defects and 5 defect-related pregnancy losses, the CDC said. There have been no Zika-related pregnancy losses reported in the states/D.C. since late June. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria.

Among all Americans in 2015-2017, there have been 41,387 cases of Zika infection as of Feb. 1. Of that total, 35,334 cases, which is more than 85%, have occurred in Puerto Rico, according to data from the CDC’s Arboviral Disease Branch.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

New cases of Zika infection in pregnant women were down again for the 50 states over the 2-week reporting period ending Jan. 24, but U.S. territories saw a big increase, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It is important to note, however, that Puerto Rico, where most U.S. Zika cases are occurring, has been retroactively reporting cases for months, which can result in larger-than-normal increases.

The territories had 186 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection for the 2 weeks ending Jan. 24, compared with 43 for the previous 2-week period. The corresponding numbers for the 50 states and the District of Columbia were 47 (Jan. 24) and 55 (Jan. 10), the CDC data show.

So far for 2016-2017, there have been 4,465 pregnant women reported to have Zika virus infection in the United States: 3,071 in the territories and 1,394 in the 50 states and D.C., according to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry (states, territories, and the District of Columbia) and the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System (Puerto Rico).

Of the nearly 1,400 state/D.C. Zika-infected pregnancies, 999 have been completed, with 38 infants born with birth defects and 5 defect-related pregnancy losses, the CDC said. There have been no Zika-related pregnancy losses reported in the states/D.C. since late June. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria.

Among all Americans in 2015-2017, there have been 41,387 cases of Zika infection as of Feb. 1. Of that total, 35,334 cases, which is more than 85%, have occurred in Puerto Rico, according to data from the CDC’s Arboviral Disease Branch.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

New cases of Zika infection in pregnant women were down again for the 50 states over the 2-week reporting period ending Jan. 24, but U.S. territories saw a big increase, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It is important to note, however, that Puerto Rico, where most U.S. Zika cases are occurring, has been retroactively reporting cases for months, which can result in larger-than-normal increases.

The territories had 186 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection for the 2 weeks ending Jan. 24, compared with 43 for the previous 2-week period. The corresponding numbers for the 50 states and the District of Columbia were 47 (Jan. 24) and 55 (Jan. 10), the CDC data show.

So far for 2016-2017, there have been 4,465 pregnant women reported to have Zika virus infection in the United States: 3,071 in the territories and 1,394 in the 50 states and D.C., according to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry (states, territories, and the District of Columbia) and the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System (Puerto Rico).

Of the nearly 1,400 state/D.C. Zika-infected pregnancies, 999 have been completed, with 38 infants born with birth defects and 5 defect-related pregnancy losses, the CDC said. There have been no Zika-related pregnancy losses reported in the states/D.C. since late June. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria.

Among all Americans in 2015-2017, there have been 41,387 cases of Zika infection as of Feb. 1. Of that total, 35,334 cases, which is more than 85%, have occurred in Puerto Rico, according to data from the CDC’s Arboviral Disease Branch.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Detecting and managing monochorionic twin complications

Approximately 20% of all twin pregnancies are monochorionic, with the fetuses sharing a single placenta. Although the majority of these pregnancies are uncomplicated, monochorionic twins are significantly more likely than dichorionic twins to incur complications that can threaten the life and health of one or both fetuses.

The death of one monochorionic twin leaves the other twin with a 15% risk of demise. Survival after the loss of a co-twin is also associated with a 25% incidence of neurologic injury, compared with a 2% incidence in dichorionic pregnancies. Additionally, monochorionic pregnancies carry the risk of unique complications such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, selective fetal growth restriction, twin anemia polycythemia sequence, and twin reversed arterial perfusion.

Increased ultrasonographic surveillance recommended for monochorionic twin pregnancies has been outlined in a recent consensus statement from the North American Fetal Therapy Network (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jan;125[1]:118-23). Beginning at 16 weeks’ gestation, monochorionic twins should be assessed every 2 weeks using amniotic fluid balance, presence/absence of fluid within the fetal bladder, and with fetal Doppler (umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery, and ductus venosus) studies. Fetal growth should also be assessed at least every 4 weeks.

Since monochorionic twins are at increased risk for congenital heart disease, echocardiography is also performed between 18 and 22 weeks, with surveillance intervals of 2 weeks or shorter if potential complications are identified. Early detection of these and other complications allows for earlier intervention, earlier referral if necessary, and potentially better outcomes.

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) is one of the most common and most serious complications, affecting approximately 10% of monochorionic pregnancies. Significant imbalances in blood-flow exchange lead to progressive cardiovascular decompensation that causes one twin to become a “donor” of blood volume, and the other twin to become a “recipient.” Without proper treatment between 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation, the perinatal mortality rate has been estimated to be 70% or higher.

Disease severity is classified according to the Quintero staging system. Stage I is characterized by amniotic fluid discordance. In stage II, the bladder of the donor twin is no longer visible sonographically. Stage III is marked by critically abnormal Doppler waveforms in either twin (absent/reverse end-diastolic velocity in the umbilical artery, reverse flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile flow in the umbilical vein). In stage IV, one of the twins has developed hydrops, and stage V is characterized by the death of one or both of the twins.

Amnioreduction to decrease intra-amniotic pressure had been the treatment of choice until a randomized controlled trial, published in 2004, demonstrated that fetoscopic laser coagulation of anastomoses was superior as a first-line treatment for severe TTTS that is diagnosed before 26 weeks. Perinatal mortality and morbidity were significantly lower after the laser treatment (N Engl J Med. 2004 Jul 8;351[2]:136-44).

Outcomes were further improved over the next decade as the laser surgery technique was modified to cover the entire vascular equator rather than selective components of the vasculature. In an open-label randomized controlled trial comparing the two approaches for severe TTTS, fetoscopic laser coagulation of the vascular equator (known as the Solomon technique) reduced the risk of twin anemia polycythemia sequence and recurrence of TTTS – the two main postoperative complications associated with residual anastomoses after selective coagulation (Lancet. 2014 Jun 21;383[9935]:2144-51).

The procedure has many challenges and can be impacted by one’s inability to see the entire vascular equator because of poor access, by the patient’s history of other interventions, and by the stage of TTTS.

Laser coagulation is regarded as the standard treatment for Quintero stage II-IV disease, and it is offered in some cases of stage I disease, such as those involving severe polyhydramnios and shortened cervix. Research currently underway is examining the outcomes of treatment for stage I disease, but data thus far suggest that intervening at stage I is generally better than expectant management.

With laser coagulation treatment, the survival rate in pregnancies complicated by TTTS is about 85%-90% for one fetus, and about 70% for both. TTTS sometimes causes one twin, particularly the recipient, to develop pulmonary valve stenosis, but this is generally a functional problem that resolves when the syndrome is treated.

After treatment, it is important to monitor for the development of twin anemia-polycythemia sequence, which may still occur if full visualization of the vascular equator was not possible or if a fine vessel was missed. Such monitoring involves weekly ultrasound surveillance with middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity measurements.

Patients should also be monitored for abnormal neurologic development, ventriculomegaly, and other signs of abnormal brain development. Even “perfect” laser treatment with seemingly complete placental separation has been associated with abnormal neurologic development in about 10%-15% of cases.

Maternal complications with TTTS include placental abruption and preterm membrane rupture, the latter of which occurs about 15%-20% of the time.

Currently under much discussion is fetoscopic laser coagulation of TTTS placentas that have “proximate cord insertions.” The surgery in these cases – where the cords are less than 4 cm apart – is much more challenging because of technical difficulties in visualizing the vascular equator, and outcomes are being studied. Some centers will not perform laser surgery on placentas with proximate cord insertions, which fortunately are uncommon. However, the surgery is possible; I have completed three cases thus far, each with dual survival.

Selective fetal growth restriction

Selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR) stems from unequal placental sharing and affects approximately 15%-20% of all monochorionic pregnancies, making it a bit more common than TTTS. Diagnostic criteria vary, but the North American Fetal Therapy Network recommends using either an estimated fetal weight below the 10th percentile, with or without significant growth discordance (greater than 25%), or just growth discordance greater than 25%. Either provides an acceptable definition of sFGR.

With sFGR, in general, the normally growing twin has normal fluid and the growth-restricted twin has less fluid. This makes it different from TTTS, in which the twins may have different sizes but fluid discordance is always present. Also in TTTS, there is a finding of polyhydramnios in the recipient.

There are three types of sFGR, based on umbilical artery Doppler findings. In type I there is no cardiovascular imbalance, and management typically involves weekly monitoring with Doppler ultrasound. If Doppler findings remain normal for some time, monitoring every 2-4 weeks will suffice. Elective delivery is generally set for 35 or 36 weeks.

Type II sFGR involves cardiovascular compromise early in pregnancy, with umbilical artery Doppler showing persistent reversed or absent end-diastolic flow. Treatment options include monitoring closely and, in general, delivering by 32 weeks. In these cases, prematurity may jeopardize the life or health of the normally growing twin while saving the life of the growth-restricted twin.

When type II sFGR is diagnosed early, selective termination of the growth-restricted fetus may be another option. This is a relatively safe procedure overall but it carries risks such as ruptured membrane and damage to the normal twin (10%-35% risk).

Type III sFGR is uniquely unpredictable, with intermittently absent or reversed flow stemming from a large artery-artery anastomosis. The direction of blood flow may suddenly change; in fact, the diagnosis is made by placing the Doppler caliper close to the placenta cord insertion and watching the end-diastolic flow. Present, absent, and reverse flow within a minute of observation demonstrates the presence of a large artery-artery anastomosis.

The risk of unexpected fetal death with severe sFGR is estimated to be 15% or higher, and the spontaneous death of the poorly growing twin threatens both the survival and the neurologic health of the co-twin. The risk of a parenchymal lesion for the co-twin is about 20%-40%.

Management decisions can be extremely difficult. As with type II, one could manage expectantly and generally deliver by 32 weeks. Fetoscopic laser coagulation to achieve complete dichorionization, as done with TTTS, could also be discussed; this approach could save the life of one twin in the event that the co-twin dies. Finally, selective termination may again be an option. None is a perfect treatment, and parents must be thoroughly counseled and supported in understanding the options and risks.

Twin anemia polycythemia sequence

Unlike TTTS, twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS) does not involve a fluid shift. Rather, red blood cells shift from one fetus to the other through extremely small-caliber vessels, leading to severe anemia of one fetus and polycythemia of the other. The chronic and unbalanced transfusion occurs in about 5% of monochorionic twins, generally after 26 weeks’ gestation.

TAPS also occurs after laser treatment for TTTS in about 10%-15% of cases (generally within 4 weeks of treatment), though this incidence is significantly reduced when complete dichorionization is achieved using the Solomon technique for fetoscopic laser coagulation. Diagnosis is made when the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity of the red blood cell donor is greater than 1.5 MoM and the peak systolic velocity of the recipient is less than 1.0 MoM, without amniotic fluid discordance.

There are no established preferred treatments, but fetoscopic laser coagulation is an option for some patients. Visibility can be extremely poor when TAPS occurs after a laser treatment and vessels can be difficult to identify, but in selected cases it is possible with an experienced team. When performed, treatment can be followed by delivery or by intrauterine transfusion of the anemic fetus. Intrauterine transfusion has been studied as a primary treatment, but it generally is problematic because the small vessels at the root of TAPS continue to exist.

Twin reversed arterial perfusion

In about 1% of monochorionic pregnancies, an arterial incident prevents one of the twins from developing a heart and upper body. Some research has suggested that the condition is associated with trisomies in about 10% of the cases.

The viable, structurally normal co-twin therefore acts like a pump, continually perfusing the nonviable twin through an abnormal vascular circuit that allows arterial blood to flow in a reverse direction. In the process, the normal twin, or “pump twin,” can develop heart failure and hydrops. Mortality appears to be about 55%.

Diagnosis is straightforward, but it has been challenging to determine which pregnancies will require intervention. Some research has suggested that the risk of hydrops and mortality increases significantly – and favors intervention – when the weight difference is greater than 70%. On the other hand, if the difference is less than 50%, survival of the pump twin approaches 80% and continuing surveillance may be most appropriate.

Radiofrequency ablation of the cord of the nonviable twin is one of the treatment methods and has about an 80% success rate. Another option is coagulation of the blood supply in the abnormal twin using a laser fiber via a fine needle during the first trimester. An ongoing European trial of the procedure is showing success rates of approximately 70%.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery, and an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Approximately 20% of all twin pregnancies are monochorionic, with the fetuses sharing a single placenta. Although the majority of these pregnancies are uncomplicated, monochorionic twins are significantly more likely than dichorionic twins to incur complications that can threaten the life and health of one or both fetuses.

The death of one monochorionic twin leaves the other twin with a 15% risk of demise. Survival after the loss of a co-twin is also associated with a 25% incidence of neurologic injury, compared with a 2% incidence in dichorionic pregnancies. Additionally, monochorionic pregnancies carry the risk of unique complications such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, selective fetal growth restriction, twin anemia polycythemia sequence, and twin reversed arterial perfusion.

Increased ultrasonographic surveillance recommended for monochorionic twin pregnancies has been outlined in a recent consensus statement from the North American Fetal Therapy Network (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jan;125[1]:118-23). Beginning at 16 weeks’ gestation, monochorionic twins should be assessed every 2 weeks using amniotic fluid balance, presence/absence of fluid within the fetal bladder, and with fetal Doppler (umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery, and ductus venosus) studies. Fetal growth should also be assessed at least every 4 weeks.

Since monochorionic twins are at increased risk for congenital heart disease, echocardiography is also performed between 18 and 22 weeks, with surveillance intervals of 2 weeks or shorter if potential complications are identified. Early detection of these and other complications allows for earlier intervention, earlier referral if necessary, and potentially better outcomes.

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) is one of the most common and most serious complications, affecting approximately 10% of monochorionic pregnancies. Significant imbalances in blood-flow exchange lead to progressive cardiovascular decompensation that causes one twin to become a “donor” of blood volume, and the other twin to become a “recipient.” Without proper treatment between 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation, the perinatal mortality rate has been estimated to be 70% or higher.

Disease severity is classified according to the Quintero staging system. Stage I is characterized by amniotic fluid discordance. In stage II, the bladder of the donor twin is no longer visible sonographically. Stage III is marked by critically abnormal Doppler waveforms in either twin (absent/reverse end-diastolic velocity in the umbilical artery, reverse flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile flow in the umbilical vein). In stage IV, one of the twins has developed hydrops, and stage V is characterized by the death of one or both of the twins.

Amnioreduction to decrease intra-amniotic pressure had been the treatment of choice until a randomized controlled trial, published in 2004, demonstrated that fetoscopic laser coagulation of anastomoses was superior as a first-line treatment for severe TTTS that is diagnosed before 26 weeks. Perinatal mortality and morbidity were significantly lower after the laser treatment (N Engl J Med. 2004 Jul 8;351[2]:136-44).

Outcomes were further improved over the next decade as the laser surgery technique was modified to cover the entire vascular equator rather than selective components of the vasculature. In an open-label randomized controlled trial comparing the two approaches for severe TTTS, fetoscopic laser coagulation of the vascular equator (known as the Solomon technique) reduced the risk of twin anemia polycythemia sequence and recurrence of TTTS – the two main postoperative complications associated with residual anastomoses after selective coagulation (Lancet. 2014 Jun 21;383[9935]:2144-51).

The procedure has many challenges and can be impacted by one’s inability to see the entire vascular equator because of poor access, by the patient’s history of other interventions, and by the stage of TTTS.

Laser coagulation is regarded as the standard treatment for Quintero stage II-IV disease, and it is offered in some cases of stage I disease, such as those involving severe polyhydramnios and shortened cervix. Research currently underway is examining the outcomes of treatment for stage I disease, but data thus far suggest that intervening at stage I is generally better than expectant management.

With laser coagulation treatment, the survival rate in pregnancies complicated by TTTS is about 85%-90% for one fetus, and about 70% for both. TTTS sometimes causes one twin, particularly the recipient, to develop pulmonary valve stenosis, but this is generally a functional problem that resolves when the syndrome is treated.

After treatment, it is important to monitor for the development of twin anemia-polycythemia sequence, which may still occur if full visualization of the vascular equator was not possible or if a fine vessel was missed. Such monitoring involves weekly ultrasound surveillance with middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity measurements.

Patients should also be monitored for abnormal neurologic development, ventriculomegaly, and other signs of abnormal brain development. Even “perfect” laser treatment with seemingly complete placental separation has been associated with abnormal neurologic development in about 10%-15% of cases.

Maternal complications with TTTS include placental abruption and preterm membrane rupture, the latter of which occurs about 15%-20% of the time.

Currently under much discussion is fetoscopic laser coagulation of TTTS placentas that have “proximate cord insertions.” The surgery in these cases – where the cords are less than 4 cm apart – is much more challenging because of technical difficulties in visualizing the vascular equator, and outcomes are being studied. Some centers will not perform laser surgery on placentas with proximate cord insertions, which fortunately are uncommon. However, the surgery is possible; I have completed three cases thus far, each with dual survival.

Selective fetal growth restriction

Selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR) stems from unequal placental sharing and affects approximately 15%-20% of all monochorionic pregnancies, making it a bit more common than TTTS. Diagnostic criteria vary, but the North American Fetal Therapy Network recommends using either an estimated fetal weight below the 10th percentile, with or without significant growth discordance (greater than 25%), or just growth discordance greater than 25%. Either provides an acceptable definition of sFGR.

With sFGR, in general, the normally growing twin has normal fluid and the growth-restricted twin has less fluid. This makes it different from TTTS, in which the twins may have different sizes but fluid discordance is always present. Also in TTTS, there is a finding of polyhydramnios in the recipient.

There are three types of sFGR, based on umbilical artery Doppler findings. In type I there is no cardiovascular imbalance, and management typically involves weekly monitoring with Doppler ultrasound. If Doppler findings remain normal for some time, monitoring every 2-4 weeks will suffice. Elective delivery is generally set for 35 or 36 weeks.

Type II sFGR involves cardiovascular compromise early in pregnancy, with umbilical artery Doppler showing persistent reversed or absent end-diastolic flow. Treatment options include monitoring closely and, in general, delivering by 32 weeks. In these cases, prematurity may jeopardize the life or health of the normally growing twin while saving the life of the growth-restricted twin.

When type II sFGR is diagnosed early, selective termination of the growth-restricted fetus may be another option. This is a relatively safe procedure overall but it carries risks such as ruptured membrane and damage to the normal twin (10%-35% risk).

Type III sFGR is uniquely unpredictable, with intermittently absent or reversed flow stemming from a large artery-artery anastomosis. The direction of blood flow may suddenly change; in fact, the diagnosis is made by placing the Doppler caliper close to the placenta cord insertion and watching the end-diastolic flow. Present, absent, and reverse flow within a minute of observation demonstrates the presence of a large artery-artery anastomosis.

The risk of unexpected fetal death with severe sFGR is estimated to be 15% or higher, and the spontaneous death of the poorly growing twin threatens both the survival and the neurologic health of the co-twin. The risk of a parenchymal lesion for the co-twin is about 20%-40%.

Management decisions can be extremely difficult. As with type II, one could manage expectantly and generally deliver by 32 weeks. Fetoscopic laser coagulation to achieve complete dichorionization, as done with TTTS, could also be discussed; this approach could save the life of one twin in the event that the co-twin dies. Finally, selective termination may again be an option. None is a perfect treatment, and parents must be thoroughly counseled and supported in understanding the options and risks.

Twin anemia polycythemia sequence

Unlike TTTS, twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS) does not involve a fluid shift. Rather, red blood cells shift from one fetus to the other through extremely small-caliber vessels, leading to severe anemia of one fetus and polycythemia of the other. The chronic and unbalanced transfusion occurs in about 5% of monochorionic twins, generally after 26 weeks’ gestation.

TAPS also occurs after laser treatment for TTTS in about 10%-15% of cases (generally within 4 weeks of treatment), though this incidence is significantly reduced when complete dichorionization is achieved using the Solomon technique for fetoscopic laser coagulation. Diagnosis is made when the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity of the red blood cell donor is greater than 1.5 MoM and the peak systolic velocity of the recipient is less than 1.0 MoM, without amniotic fluid discordance.

There are no established preferred treatments, but fetoscopic laser coagulation is an option for some patients. Visibility can be extremely poor when TAPS occurs after a laser treatment and vessels can be difficult to identify, but in selected cases it is possible with an experienced team. When performed, treatment can be followed by delivery or by intrauterine transfusion of the anemic fetus. Intrauterine transfusion has been studied as a primary treatment, but it generally is problematic because the small vessels at the root of TAPS continue to exist.

Twin reversed arterial perfusion

In about 1% of monochorionic pregnancies, an arterial incident prevents one of the twins from developing a heart and upper body. Some research has suggested that the condition is associated with trisomies in about 10% of the cases.

The viable, structurally normal co-twin therefore acts like a pump, continually perfusing the nonviable twin through an abnormal vascular circuit that allows arterial blood to flow in a reverse direction. In the process, the normal twin, or “pump twin,” can develop heart failure and hydrops. Mortality appears to be about 55%.

Diagnosis is straightforward, but it has been challenging to determine which pregnancies will require intervention. Some research has suggested that the risk of hydrops and mortality increases significantly – and favors intervention – when the weight difference is greater than 70%. On the other hand, if the difference is less than 50%, survival of the pump twin approaches 80% and continuing surveillance may be most appropriate.

Radiofrequency ablation of the cord of the nonviable twin is one of the treatment methods and has about an 80% success rate. Another option is coagulation of the blood supply in the abnormal twin using a laser fiber via a fine needle during the first trimester. An ongoing European trial of the procedure is showing success rates of approximately 70%.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery, and an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Approximately 20% of all twin pregnancies are monochorionic, with the fetuses sharing a single placenta. Although the majority of these pregnancies are uncomplicated, monochorionic twins are significantly more likely than dichorionic twins to incur complications that can threaten the life and health of one or both fetuses.

The death of one monochorionic twin leaves the other twin with a 15% risk of demise. Survival after the loss of a co-twin is also associated with a 25% incidence of neurologic injury, compared with a 2% incidence in dichorionic pregnancies. Additionally, monochorionic pregnancies carry the risk of unique complications such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, selective fetal growth restriction, twin anemia polycythemia sequence, and twin reversed arterial perfusion.

Increased ultrasonographic surveillance recommended for monochorionic twin pregnancies has been outlined in a recent consensus statement from the North American Fetal Therapy Network (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jan;125[1]:118-23). Beginning at 16 weeks’ gestation, monochorionic twins should be assessed every 2 weeks using amniotic fluid balance, presence/absence of fluid within the fetal bladder, and with fetal Doppler (umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery, and ductus venosus) studies. Fetal growth should also be assessed at least every 4 weeks.

Since monochorionic twins are at increased risk for congenital heart disease, echocardiography is also performed between 18 and 22 weeks, with surveillance intervals of 2 weeks or shorter if potential complications are identified. Early detection of these and other complications allows for earlier intervention, earlier referral if necessary, and potentially better outcomes.

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) is one of the most common and most serious complications, affecting approximately 10% of monochorionic pregnancies. Significant imbalances in blood-flow exchange lead to progressive cardiovascular decompensation that causes one twin to become a “donor” of blood volume, and the other twin to become a “recipient.” Without proper treatment between 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation, the perinatal mortality rate has been estimated to be 70% or higher.

Disease severity is classified according to the Quintero staging system. Stage I is characterized by amniotic fluid discordance. In stage II, the bladder of the donor twin is no longer visible sonographically. Stage III is marked by critically abnormal Doppler waveforms in either twin (absent/reverse end-diastolic velocity in the umbilical artery, reverse flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile flow in the umbilical vein). In stage IV, one of the twins has developed hydrops, and stage V is characterized by the death of one or both of the twins.

Amnioreduction to decrease intra-amniotic pressure had been the treatment of choice until a randomized controlled trial, published in 2004, demonstrated that fetoscopic laser coagulation of anastomoses was superior as a first-line treatment for severe TTTS that is diagnosed before 26 weeks. Perinatal mortality and morbidity were significantly lower after the laser treatment (N Engl J Med. 2004 Jul 8;351[2]:136-44).

Outcomes were further improved over the next decade as the laser surgery technique was modified to cover the entire vascular equator rather than selective components of the vasculature. In an open-label randomized controlled trial comparing the two approaches for severe TTTS, fetoscopic laser coagulation of the vascular equator (known as the Solomon technique) reduced the risk of twin anemia polycythemia sequence and recurrence of TTTS – the two main postoperative complications associated with residual anastomoses after selective coagulation (Lancet. 2014 Jun 21;383[9935]:2144-51).

The procedure has many challenges and can be impacted by one’s inability to see the entire vascular equator because of poor access, by the patient’s history of other interventions, and by the stage of TTTS.

Laser coagulation is regarded as the standard treatment for Quintero stage II-IV disease, and it is offered in some cases of stage I disease, such as those involving severe polyhydramnios and shortened cervix. Research currently underway is examining the outcomes of treatment for stage I disease, but data thus far suggest that intervening at stage I is generally better than expectant management.

With laser coagulation treatment, the survival rate in pregnancies complicated by TTTS is about 85%-90% for one fetus, and about 70% for both. TTTS sometimes causes one twin, particularly the recipient, to develop pulmonary valve stenosis, but this is generally a functional problem that resolves when the syndrome is treated.

After treatment, it is important to monitor for the development of twin anemia-polycythemia sequence, which may still occur if full visualization of the vascular equator was not possible or if a fine vessel was missed. Such monitoring involves weekly ultrasound surveillance with middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity measurements.

Patients should also be monitored for abnormal neurologic development, ventriculomegaly, and other signs of abnormal brain development. Even “perfect” laser treatment with seemingly complete placental separation has been associated with abnormal neurologic development in about 10%-15% of cases.

Maternal complications with TTTS include placental abruption and preterm membrane rupture, the latter of which occurs about 15%-20% of the time.

Currently under much discussion is fetoscopic laser coagulation of TTTS placentas that have “proximate cord insertions.” The surgery in these cases – where the cords are less than 4 cm apart – is much more challenging because of technical difficulties in visualizing the vascular equator, and outcomes are being studied. Some centers will not perform laser surgery on placentas with proximate cord insertions, which fortunately are uncommon. However, the surgery is possible; I have completed three cases thus far, each with dual survival.

Selective fetal growth restriction

Selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR) stems from unequal placental sharing and affects approximately 15%-20% of all monochorionic pregnancies, making it a bit more common than TTTS. Diagnostic criteria vary, but the North American Fetal Therapy Network recommends using either an estimated fetal weight below the 10th percentile, with or without significant growth discordance (greater than 25%), or just growth discordance greater than 25%. Either provides an acceptable definition of sFGR.

With sFGR, in general, the normally growing twin has normal fluid and the growth-restricted twin has less fluid. This makes it different from TTTS, in which the twins may have different sizes but fluid discordance is always present. Also in TTTS, there is a finding of polyhydramnios in the recipient.

There are three types of sFGR, based on umbilical artery Doppler findings. In type I there is no cardiovascular imbalance, and management typically involves weekly monitoring with Doppler ultrasound. If Doppler findings remain normal for some time, monitoring every 2-4 weeks will suffice. Elective delivery is generally set for 35 or 36 weeks.

Type II sFGR involves cardiovascular compromise early in pregnancy, with umbilical artery Doppler showing persistent reversed or absent end-diastolic flow. Treatment options include monitoring closely and, in general, delivering by 32 weeks. In these cases, prematurity may jeopardize the life or health of the normally growing twin while saving the life of the growth-restricted twin.

When type II sFGR is diagnosed early, selective termination of the growth-restricted fetus may be another option. This is a relatively safe procedure overall but it carries risks such as ruptured membrane and damage to the normal twin (10%-35% risk).

Type III sFGR is uniquely unpredictable, with intermittently absent or reversed flow stemming from a large artery-artery anastomosis. The direction of blood flow may suddenly change; in fact, the diagnosis is made by placing the Doppler caliper close to the placenta cord insertion and watching the end-diastolic flow. Present, absent, and reverse flow within a minute of observation demonstrates the presence of a large artery-artery anastomosis.

The risk of unexpected fetal death with severe sFGR is estimated to be 15% or higher, and the spontaneous death of the poorly growing twin threatens both the survival and the neurologic health of the co-twin. The risk of a parenchymal lesion for the co-twin is about 20%-40%.