User login

Hypertension in SLE pregnancy: Is it lupus flare or preeclampsia?

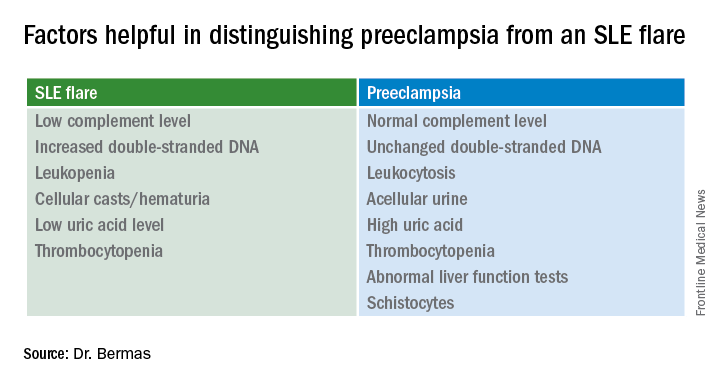

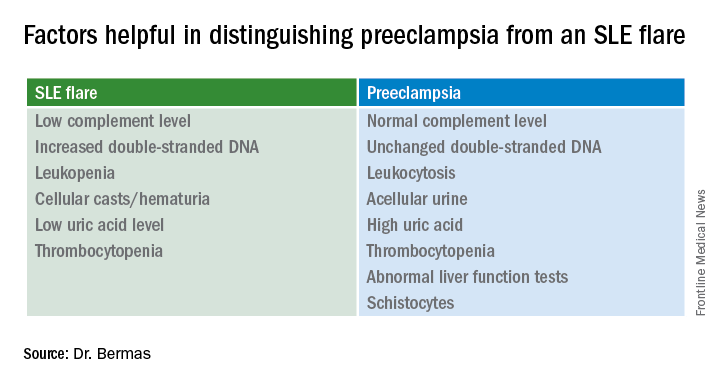

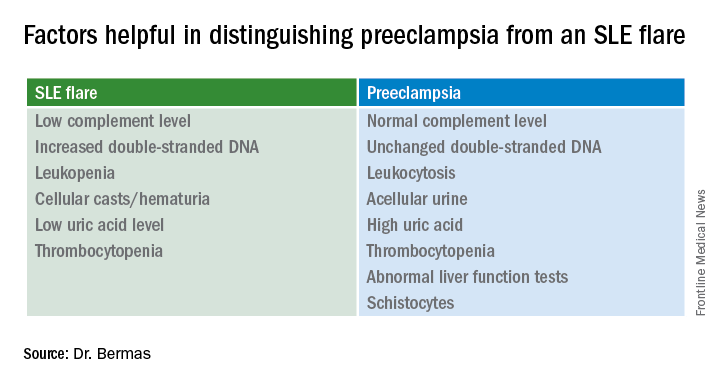

SNOWMASS, COLO. – No hard and fast test exists that would enable a physician to tell a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus from preeclampsia in a pregnant lupus patient who becomes hypertensive and ill, but there are highly useful clues, Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

“There is no perfect way of distinguishing between a lupus flare and preeclampsia. I’ve never walked away from the labor floor and said, ‘This is great – I know this is a lupus flare,’ or ‘I know this is preeclampsia.’ But you make your best guess as to which one it is, and that will inform your management,” explained Dr. Bermas, a rheumatologist and director of the clinical lupus program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Why do we care? Because if it’s preeclampsia the mother needs to be delivered immediately for her safety, while if it’s an SLE flare sometimes you can treat it and get the fetus to a more viable age. A 23-week-old baby isn’t at all likely to make it, but a 27-week-old could,” Dr. Bermas said.

The fact that the patient has thrombocytopenia isn’t helpful in making the distinction, since that feature is shared in common by SLE flares and preeclampsia. But the uric acid level is a useful clue.

It’s quite possible that much of the current guesswork in predicting preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients will give way to reliable risk testing within the next several years. Investigators in the U.S. multicenter prospective PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study have reported that circulating levels of the angiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor were abnormal as early as gestational weeks 12-15 in patients who went on to develop preeclampsia or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, monthly testing demonstrated that SLE patients in the top quartile for soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 at weeks 12-15 had an adjusted 17.3-fold greater likelihood of experiencing a severe adverse pregnancy outcome than did those in the lowest quartile. A high level had a positive predictive value of 61% and a negative predictive value of 93% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214[1]:108.e1-14). These findings are being further explored in ongoing studies.

“Hopefully, in another few years we’re going to be able to say early in pregnancy, ‘This person is set up to get preeclampsia.’ Maybe that will lead to better treatment as well,” Dr. Bermas said.

The risk of preeclampsia has been shown to be threefold higher in women with SLE than in the general population of pregnant women in a study of more than 16.7 million admissions for childbirth in the United States during a 4-year period. The SLE patients were also at 2.4-fold increased risk for preterm labor. Their risks of infection, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion were each three- to seven-fold higher as well (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199[2]:127.e1-16).

Dr. Bermas reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – No hard and fast test exists that would enable a physician to tell a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus from preeclampsia in a pregnant lupus patient who becomes hypertensive and ill, but there are highly useful clues, Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

“There is no perfect way of distinguishing between a lupus flare and preeclampsia. I’ve never walked away from the labor floor and said, ‘This is great – I know this is a lupus flare,’ or ‘I know this is preeclampsia.’ But you make your best guess as to which one it is, and that will inform your management,” explained Dr. Bermas, a rheumatologist and director of the clinical lupus program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Why do we care? Because if it’s preeclampsia the mother needs to be delivered immediately for her safety, while if it’s an SLE flare sometimes you can treat it and get the fetus to a more viable age. A 23-week-old baby isn’t at all likely to make it, but a 27-week-old could,” Dr. Bermas said.

The fact that the patient has thrombocytopenia isn’t helpful in making the distinction, since that feature is shared in common by SLE flares and preeclampsia. But the uric acid level is a useful clue.

It’s quite possible that much of the current guesswork in predicting preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients will give way to reliable risk testing within the next several years. Investigators in the U.S. multicenter prospective PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study have reported that circulating levels of the angiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor were abnormal as early as gestational weeks 12-15 in patients who went on to develop preeclampsia or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, monthly testing demonstrated that SLE patients in the top quartile for soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 at weeks 12-15 had an adjusted 17.3-fold greater likelihood of experiencing a severe adverse pregnancy outcome than did those in the lowest quartile. A high level had a positive predictive value of 61% and a negative predictive value of 93% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214[1]:108.e1-14). These findings are being further explored in ongoing studies.

“Hopefully, in another few years we’re going to be able to say early in pregnancy, ‘This person is set up to get preeclampsia.’ Maybe that will lead to better treatment as well,” Dr. Bermas said.

The risk of preeclampsia has been shown to be threefold higher in women with SLE than in the general population of pregnant women in a study of more than 16.7 million admissions for childbirth in the United States during a 4-year period. The SLE patients were also at 2.4-fold increased risk for preterm labor. Their risks of infection, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion were each three- to seven-fold higher as well (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199[2]:127.e1-16).

Dr. Bermas reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – No hard and fast test exists that would enable a physician to tell a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus from preeclampsia in a pregnant lupus patient who becomes hypertensive and ill, but there are highly useful clues, Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

“There is no perfect way of distinguishing between a lupus flare and preeclampsia. I’ve never walked away from the labor floor and said, ‘This is great – I know this is a lupus flare,’ or ‘I know this is preeclampsia.’ But you make your best guess as to which one it is, and that will inform your management,” explained Dr. Bermas, a rheumatologist and director of the clinical lupus program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Why do we care? Because if it’s preeclampsia the mother needs to be delivered immediately for her safety, while if it’s an SLE flare sometimes you can treat it and get the fetus to a more viable age. A 23-week-old baby isn’t at all likely to make it, but a 27-week-old could,” Dr. Bermas said.

The fact that the patient has thrombocytopenia isn’t helpful in making the distinction, since that feature is shared in common by SLE flares and preeclampsia. But the uric acid level is a useful clue.

It’s quite possible that much of the current guesswork in predicting preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients will give way to reliable risk testing within the next several years. Investigators in the U.S. multicenter prospective PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study have reported that circulating levels of the angiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor were abnormal as early as gestational weeks 12-15 in patients who went on to develop preeclampsia or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, monthly testing demonstrated that SLE patients in the top quartile for soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 at weeks 12-15 had an adjusted 17.3-fold greater likelihood of experiencing a severe adverse pregnancy outcome than did those in the lowest quartile. A high level had a positive predictive value of 61% and a negative predictive value of 93% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214[1]:108.e1-14). These findings are being further explored in ongoing studies.

“Hopefully, in another few years we’re going to be able to say early in pregnancy, ‘This person is set up to get preeclampsia.’ Maybe that will lead to better treatment as well,” Dr. Bermas said.

The risk of preeclampsia has been shown to be threefold higher in women with SLE than in the general population of pregnant women in a study of more than 16.7 million admissions for childbirth in the United States during a 4-year period. The SLE patients were also at 2.4-fold increased risk for preterm labor. Their risks of infection, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion were each three- to seven-fold higher as well (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199[2]:127.e1-16).

Dr. Bermas reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

VIDEO: Dual antibiotic prophylaxis cuts cesarean SSIs

LAS VEGAS – Two days of prophylaxis with two oral antibiotics cut the surgical site infection rate by more than half in a randomized trial with more than 400 obese women who had cesarean deliveries.

The protective effect from combined treatment with cephalexin and metronidazole was especially powerful in the most at-risk patients, women with ruptured membranes before cesarean surgery. In this subgroup prophylaxis with the two antibiotics for 2 days cut surgical site infections (SSIs) during the 30 days after surgery, from a rate of 33% in control women who received placebo to a 10% rate, a 77% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant, Carri R. Warshak, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine.

“I am very excited that we found a way to help the kinds of women in the study, very-high-risk women, with an effective way to reduce their risk of infection,” Dr. Warshak of the University of Cincinnati said in a video interview. The obese women enrolled in the study, especially those with ruptured membranes, “have a very high risk of morbidity, so it’s very exciting that we found a way to help prevent” SSIs.

“Our study is the first to target postpartum interventions to reduce SSIs specifically in this high-risk population” of obese mothers, said Amy M. Valent, DO, a maternal fetal medicine clinician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who ran the trial with Dr. Warshak.

The trial randomized women with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 who underwent a planned or unplanned cesarean delivery at the University of Cincinnati during 2010-2015. Following standard management during cesarean delivery, the women received either 500 mg oral cephalexin and 500 mg oral metronidazole or placebo every 8 hours for 48 hours following delivery. The primary outcome was the incidence of SSIs, and randomization was stratified so that similar numbers of women with ruptured membranes got into each treatment arm. The enrolled women averaged 28 years of age, and average BMI was about 40 kg/m2. Nearly a third of the women had ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, more than a quarter of the enrolled women used tobacco, and more than a fifth had preeclampsia.

Additional analyses reported at the meeting by Dr. Valent showed that other risk factors that significantly boosted the rate of SSIs were labor prior to delivery, use of internal monitoring, and operative time of more than 90 minutes. Antibiotic prophylaxis was able to significantly reduce SSI rates in women with any of these additional risk factors, compared with placebo. A cost effectiveness analysis she ran estimated that if the antibiotic prophylaxis tested in the study were used on the roughly 460,000 obese U.S. women having cesarean deliveries annually, it would be cost saving as long as the antibiotic regimen cost no more than $357 a person. Factoring in the SSIs and long-term morbidity that prophylaxis would prevent, and the quality-adjusted life-years it would add, showed that prophylaxis would be cost-effective up to a cost of $33,557 per woman.

The prophylaxis carries a “relatively low cost and is easy to use,” Dr. Valent said.

Safety of the antibiotic combination was a question raised by Laura E. Riley, MD, director of ob.gyn. infectious disease and labor and delivery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “My biggest concern is 48 hours of these antibiotics,” and whether prophylaxis could be achieved with fewer doses, she said in an interview. “I’d want to minimize the dosage, and also try other, nondrug approaches to minimizing SSI risk in obese women.”

“I wouldn’t say that universally, every obstetrical program should do this, but clinicians should look at the comorbidities their mothers have and their SSI rates. There are populations out there at lower risk, but there are also populations like ours, with a SSI rate of 10%-20%,” Dr. Warshak said.

She also acknowledged that even her own obstetrical group in Cincinnati needs to now reach a consensus on an appropriate strategy for expanded cesarean-delivery prophylaxis. That’s because a 2016 report from a large, randomized trial documented another successful strategy for limiting infections following cesarean delivery: a preoperative intravenous dose of azithromycin as a supplement to standard cefazolin. The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial, done in women with any BMI but specifically nonelective cesarean deliveries, showed a significant reduction in the combined rate of SSIs, endometritis, or any other infection during 6 weeks of follow-up among women who received azithromycin on top of standard prophylaxis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29;375[13]:1231-41).

“The bottom line is that, a couple of grams of cefazolin [administered before the incision] isn’t enough, especially for women with risk factors for infection. We see infection rates of more than 10% because cefazolin alone is simply inadequate. The results from both our study and the 2016 study show we can do better to reduce morbidity,” said Dr. Warshak.

“In high-risk women, such as those who are obese, we probably need to expand the spectrum and duration of prophylaxis,” agreed Dr. Main. “Obesity is one high-risk group, but there are others.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Two days of prophylaxis with two oral antibiotics cut the surgical site infection rate by more than half in a randomized trial with more than 400 obese women who had cesarean deliveries.

The protective effect from combined treatment with cephalexin and metronidazole was especially powerful in the most at-risk patients, women with ruptured membranes before cesarean surgery. In this subgroup prophylaxis with the two antibiotics for 2 days cut surgical site infections (SSIs) during the 30 days after surgery, from a rate of 33% in control women who received placebo to a 10% rate, a 77% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant, Carri R. Warshak, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine.

“I am very excited that we found a way to help the kinds of women in the study, very-high-risk women, with an effective way to reduce their risk of infection,” Dr. Warshak of the University of Cincinnati said in a video interview. The obese women enrolled in the study, especially those with ruptured membranes, “have a very high risk of morbidity, so it’s very exciting that we found a way to help prevent” SSIs.

“Our study is the first to target postpartum interventions to reduce SSIs specifically in this high-risk population” of obese mothers, said Amy M. Valent, DO, a maternal fetal medicine clinician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who ran the trial with Dr. Warshak.

The trial randomized women with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 who underwent a planned or unplanned cesarean delivery at the University of Cincinnati during 2010-2015. Following standard management during cesarean delivery, the women received either 500 mg oral cephalexin and 500 mg oral metronidazole or placebo every 8 hours for 48 hours following delivery. The primary outcome was the incidence of SSIs, and randomization was stratified so that similar numbers of women with ruptured membranes got into each treatment arm. The enrolled women averaged 28 years of age, and average BMI was about 40 kg/m2. Nearly a third of the women had ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, more than a quarter of the enrolled women used tobacco, and more than a fifth had preeclampsia.

Additional analyses reported at the meeting by Dr. Valent showed that other risk factors that significantly boosted the rate of SSIs were labor prior to delivery, use of internal monitoring, and operative time of more than 90 minutes. Antibiotic prophylaxis was able to significantly reduce SSI rates in women with any of these additional risk factors, compared with placebo. A cost effectiveness analysis she ran estimated that if the antibiotic prophylaxis tested in the study were used on the roughly 460,000 obese U.S. women having cesarean deliveries annually, it would be cost saving as long as the antibiotic regimen cost no more than $357 a person. Factoring in the SSIs and long-term morbidity that prophylaxis would prevent, and the quality-adjusted life-years it would add, showed that prophylaxis would be cost-effective up to a cost of $33,557 per woman.

The prophylaxis carries a “relatively low cost and is easy to use,” Dr. Valent said.

Safety of the antibiotic combination was a question raised by Laura E. Riley, MD, director of ob.gyn. infectious disease and labor and delivery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “My biggest concern is 48 hours of these antibiotics,” and whether prophylaxis could be achieved with fewer doses, she said in an interview. “I’d want to minimize the dosage, and also try other, nondrug approaches to minimizing SSI risk in obese women.”

“I wouldn’t say that universally, every obstetrical program should do this, but clinicians should look at the comorbidities their mothers have and their SSI rates. There are populations out there at lower risk, but there are also populations like ours, with a SSI rate of 10%-20%,” Dr. Warshak said.

She also acknowledged that even her own obstetrical group in Cincinnati needs to now reach a consensus on an appropriate strategy for expanded cesarean-delivery prophylaxis. That’s because a 2016 report from a large, randomized trial documented another successful strategy for limiting infections following cesarean delivery: a preoperative intravenous dose of azithromycin as a supplement to standard cefazolin. The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial, done in women with any BMI but specifically nonelective cesarean deliveries, showed a significant reduction in the combined rate of SSIs, endometritis, or any other infection during 6 weeks of follow-up among women who received azithromycin on top of standard prophylaxis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29;375[13]:1231-41).

“The bottom line is that, a couple of grams of cefazolin [administered before the incision] isn’t enough, especially for women with risk factors for infection. We see infection rates of more than 10% because cefazolin alone is simply inadequate. The results from both our study and the 2016 study show we can do better to reduce morbidity,” said Dr. Warshak.

“In high-risk women, such as those who are obese, we probably need to expand the spectrum and duration of prophylaxis,” agreed Dr. Main. “Obesity is one high-risk group, but there are others.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Two days of prophylaxis with two oral antibiotics cut the surgical site infection rate by more than half in a randomized trial with more than 400 obese women who had cesarean deliveries.

The protective effect from combined treatment with cephalexin and metronidazole was especially powerful in the most at-risk patients, women with ruptured membranes before cesarean surgery. In this subgroup prophylaxis with the two antibiotics for 2 days cut surgical site infections (SSIs) during the 30 days after surgery, from a rate of 33% in control women who received placebo to a 10% rate, a 77% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant, Carri R. Warshak, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine.

“I am very excited that we found a way to help the kinds of women in the study, very-high-risk women, with an effective way to reduce their risk of infection,” Dr. Warshak of the University of Cincinnati said in a video interview. The obese women enrolled in the study, especially those with ruptured membranes, “have a very high risk of morbidity, so it’s very exciting that we found a way to help prevent” SSIs.

“Our study is the first to target postpartum interventions to reduce SSIs specifically in this high-risk population” of obese mothers, said Amy M. Valent, DO, a maternal fetal medicine clinician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who ran the trial with Dr. Warshak.

The trial randomized women with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 who underwent a planned or unplanned cesarean delivery at the University of Cincinnati during 2010-2015. Following standard management during cesarean delivery, the women received either 500 mg oral cephalexin and 500 mg oral metronidazole or placebo every 8 hours for 48 hours following delivery. The primary outcome was the incidence of SSIs, and randomization was stratified so that similar numbers of women with ruptured membranes got into each treatment arm. The enrolled women averaged 28 years of age, and average BMI was about 40 kg/m2. Nearly a third of the women had ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, more than a quarter of the enrolled women used tobacco, and more than a fifth had preeclampsia.

Additional analyses reported at the meeting by Dr. Valent showed that other risk factors that significantly boosted the rate of SSIs were labor prior to delivery, use of internal monitoring, and operative time of more than 90 minutes. Antibiotic prophylaxis was able to significantly reduce SSI rates in women with any of these additional risk factors, compared with placebo. A cost effectiveness analysis she ran estimated that if the antibiotic prophylaxis tested in the study were used on the roughly 460,000 obese U.S. women having cesarean deliveries annually, it would be cost saving as long as the antibiotic regimen cost no more than $357 a person. Factoring in the SSIs and long-term morbidity that prophylaxis would prevent, and the quality-adjusted life-years it would add, showed that prophylaxis would be cost-effective up to a cost of $33,557 per woman.

The prophylaxis carries a “relatively low cost and is easy to use,” Dr. Valent said.

Safety of the antibiotic combination was a question raised by Laura E. Riley, MD, director of ob.gyn. infectious disease and labor and delivery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “My biggest concern is 48 hours of these antibiotics,” and whether prophylaxis could be achieved with fewer doses, she said in an interview. “I’d want to minimize the dosage, and also try other, nondrug approaches to minimizing SSI risk in obese women.”

“I wouldn’t say that universally, every obstetrical program should do this, but clinicians should look at the comorbidities their mothers have and their SSI rates. There are populations out there at lower risk, but there are also populations like ours, with a SSI rate of 10%-20%,” Dr. Warshak said.

She also acknowledged that even her own obstetrical group in Cincinnati needs to now reach a consensus on an appropriate strategy for expanded cesarean-delivery prophylaxis. That’s because a 2016 report from a large, randomized trial documented another successful strategy for limiting infections following cesarean delivery: a preoperative intravenous dose of azithromycin as a supplement to standard cefazolin. The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial, done in women with any BMI but specifically nonelective cesarean deliveries, showed a significant reduction in the combined rate of SSIs, endometritis, or any other infection during 6 weeks of follow-up among women who received azithromycin on top of standard prophylaxis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29;375[13]:1231-41).

“The bottom line is that, a couple of grams of cefazolin [administered before the incision] isn’t enough, especially for women with risk factors for infection. We see infection rates of more than 10% because cefazolin alone is simply inadequate. The results from both our study and the 2016 study show we can do better to reduce morbidity,” said Dr. Warshak.

“In high-risk women, such as those who are obese, we probably need to expand the spectrum and duration of prophylaxis,” agreed Dr. Main. “Obesity is one high-risk group, but there are others.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Surgical site infections occurred in 7% of women who received oral prophylaxis and 16% of controls during 30-day follow-up.

Data source: A single-center randomized trial with 382 evaluable women.

Disclosures: Dr. Warshak had no relevant disclosures.

Study highlights importance of genotyping in von Willebrand disease

Patients with genetically confirmed von Willebrand disease (VWD) type 2M have a relatively mild clinical phenotype, according to findings from a retrospective cross-sectional study.

In fact, three of 31 patients included in the study had a near normal laboratory phenotype. Additionally, patients with the p.Val1360Ala mutation had significantly higher values of all von Willebrand factor (VWF)-related laboratory parameters, compared with those with the p.Arg1374Cys or p.Phe1293Leu mutation, Dominique Maas reported at the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders annual meeting.

The findings underscore the importance of genotyping for making a correct diagnosis of VWD type 2M, said Ms. Maas of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

The study subjects, who had a least one VWD type 2M mutation, had a median age of 34 years and a median bleeding score of 6. Most suffered from mucocutaneous bleeding, but with low frequency compared with other VWD subtypes. The incidence of muscle hematomas, postpartum hemorrhage, and postsurgery bleeding were relatively high, however. Age and bleeding score were strongly positively correlated.

Subjects had a median VWF antigen level of 24 IU dL-1, median VWF ristocetin cofactor activity of 6 IU dL-1, and median VSF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio of 0.29. The VSF collagen binding activity and VWF:Ag ratio was normal, she said.

Genotyping is a powerful diagnostic tool for making an appropriate diagnosis and classification of VWD. The current findings are important because understanding the correlation between genotype and phenotype improves the understanding of VWD pathogenesis and has important implications for treatment, follow-up, and genetic counseling, but has not been throughly investigated in fully genotyped patients with VWD type 2M, she said.

Ms. Maas reported having no disclosures.

Patients with genetically confirmed von Willebrand disease (VWD) type 2M have a relatively mild clinical phenotype, according to findings from a retrospective cross-sectional study.

In fact, three of 31 patients included in the study had a near normal laboratory phenotype. Additionally, patients with the p.Val1360Ala mutation had significantly higher values of all von Willebrand factor (VWF)-related laboratory parameters, compared with those with the p.Arg1374Cys or p.Phe1293Leu mutation, Dominique Maas reported at the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders annual meeting.

The findings underscore the importance of genotyping for making a correct diagnosis of VWD type 2M, said Ms. Maas of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

The study subjects, who had a least one VWD type 2M mutation, had a median age of 34 years and a median bleeding score of 6. Most suffered from mucocutaneous bleeding, but with low frequency compared with other VWD subtypes. The incidence of muscle hematomas, postpartum hemorrhage, and postsurgery bleeding were relatively high, however. Age and bleeding score were strongly positively correlated.

Subjects had a median VWF antigen level of 24 IU dL-1, median VWF ristocetin cofactor activity of 6 IU dL-1, and median VSF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio of 0.29. The VSF collagen binding activity and VWF:Ag ratio was normal, she said.

Genotyping is a powerful diagnostic tool for making an appropriate diagnosis and classification of VWD. The current findings are important because understanding the correlation between genotype and phenotype improves the understanding of VWD pathogenesis and has important implications for treatment, follow-up, and genetic counseling, but has not been throughly investigated in fully genotyped patients with VWD type 2M, she said.

Ms. Maas reported having no disclosures.

Patients with genetically confirmed von Willebrand disease (VWD) type 2M have a relatively mild clinical phenotype, according to findings from a retrospective cross-sectional study.

In fact, three of 31 patients included in the study had a near normal laboratory phenotype. Additionally, patients with the p.Val1360Ala mutation had significantly higher values of all von Willebrand factor (VWF)-related laboratory parameters, compared with those with the p.Arg1374Cys or p.Phe1293Leu mutation, Dominique Maas reported at the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders annual meeting.

The findings underscore the importance of genotyping for making a correct diagnosis of VWD type 2M, said Ms. Maas of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

The study subjects, who had a least one VWD type 2M mutation, had a median age of 34 years and a median bleeding score of 6. Most suffered from mucocutaneous bleeding, but with low frequency compared with other VWD subtypes. The incidence of muscle hematomas, postpartum hemorrhage, and postsurgery bleeding were relatively high, however. Age and bleeding score were strongly positively correlated.

Subjects had a median VWF antigen level of 24 IU dL-1, median VWF ristocetin cofactor activity of 6 IU dL-1, and median VSF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio of 0.29. The VSF collagen binding activity and VWF:Ag ratio was normal, she said.

Genotyping is a powerful diagnostic tool for making an appropriate diagnosis and classification of VWD. The current findings are important because understanding the correlation between genotype and phenotype improves the understanding of VWD pathogenesis and has important implications for treatment, follow-up, and genetic counseling, but has not been throughly investigated in fully genotyped patients with VWD type 2M, she said.

Ms. Maas reported having no disclosures.

FROM EAHAD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Three of 31 patients included in the study had a near normal laboratory phenotype.

Data source: A retrospective cross-sectional study of 31 patients.

Disclosures: Ms. Maas reported having no disclosures.

Maternal mental health: New consensus on optimal care

A new consensus bundle of recommendations calls on ob.gyns. to integrate mental health care into their care of pregnant and postpartum women.

The interdisciplinary Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care issued a consensus document summarizing existing recommendations on maternal mental health and pairing them with appropriate screening and other resources. The bundle of recommendations was jointly issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and other groups (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;129(3):422-430)*.

While no novel information is included in the bundle, the goal is to provide a streamlined document that pairs previous recommendations with resources and tools.

“Embedding a mental health professional with the women’s health care provider would seem to be the ideal, [but] in reality, this may not be available in every setting or geographic location,” Susan Kendig, JD, MSN, WHNP-BC, FAANP, policy director for the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and one of the authors of the document, said in an interview. “The purpose of the consensus bundle is to provide a framework for women’s health care providers to use in developing a system of care that includes standardized risk assessment for existing or emerging mental health issues, strategies for brief interventions, identification of community resources available to the woman, and/or resources to support the provider in addressing the woman’s needs and facilitating appropriate referrals, and addressing emergencies to prevent harm.”

The framework is grouped in four domains: readiness, recognition and prevention, response, and reporting and systems learning.

Readiness is focused largely on setting up clinical and administrative protocols, including mental health screening that is seamlessly integrated into the patient visit, established algorithms that are triggered according to screening results, and designated staff to both educate colleagues on the protocols and to drive their implementation.

The goal for physicians in all settings, according to the authors, is to balance cost, availability of tools, ease of use, and the validity of the tools against the need to capture often unrecognized signs and symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, including changes in sleep patterns, appetite, or anxiety levels that often are attributed to the physiologic and neuroendocrinologic changes inherent in childbirth. More than 80% of women know something is “off” but do not bring up their symptoms to their clinician, according to the recommendation document.

“Coordination and team cohesiveness is not necessarily dependent on co-location,” Ms. Kendig said. “Virtual teams, where care is coordinated among providers at different locations, can also achieve positive outcomes.”

The follow-on to this – recognition and prevention – views every patient visit as an opportunity to draw a thorough picture of mental and physical health by taking a complete family and patient history, maintaining routine screening, and offering psychoeducation to patients and their families or others on whom they rely for emotional support.

When a woman does screen positive for perinatal mood or anxiety disorders, the next bundle offers a rough outline of a stage-based response for intervention and follow-up.

“Screening alone does not appear to improve pregnancy or maternal-child outcomes,” the authors wrote.

Several possible algorithms are included in the document, including for emergent mental health concerns such as suicidal or homicidal ideation.

The final domain relies on data capture, taking a systems approach to not only delivering care, but also improving it. This includes scheduling regular staff debriefings after severe maternal mental health crises, troubleshooting why some patients become lost to follow-up, and examining data to see patterns.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CORRECTION, 3/20/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the citation.

A new consensus bundle of recommendations calls on ob.gyns. to integrate mental health care into their care of pregnant and postpartum women.

The interdisciplinary Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care issued a consensus document summarizing existing recommendations on maternal mental health and pairing them with appropriate screening and other resources. The bundle of recommendations was jointly issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and other groups (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;129(3):422-430)*.

While no novel information is included in the bundle, the goal is to provide a streamlined document that pairs previous recommendations with resources and tools.

“Embedding a mental health professional with the women’s health care provider would seem to be the ideal, [but] in reality, this may not be available in every setting or geographic location,” Susan Kendig, JD, MSN, WHNP-BC, FAANP, policy director for the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and one of the authors of the document, said in an interview. “The purpose of the consensus bundle is to provide a framework for women’s health care providers to use in developing a system of care that includes standardized risk assessment for existing or emerging mental health issues, strategies for brief interventions, identification of community resources available to the woman, and/or resources to support the provider in addressing the woman’s needs and facilitating appropriate referrals, and addressing emergencies to prevent harm.”

The framework is grouped in four domains: readiness, recognition and prevention, response, and reporting and systems learning.

Readiness is focused largely on setting up clinical and administrative protocols, including mental health screening that is seamlessly integrated into the patient visit, established algorithms that are triggered according to screening results, and designated staff to both educate colleagues on the protocols and to drive their implementation.

The goal for physicians in all settings, according to the authors, is to balance cost, availability of tools, ease of use, and the validity of the tools against the need to capture often unrecognized signs and symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, including changes in sleep patterns, appetite, or anxiety levels that often are attributed to the physiologic and neuroendocrinologic changes inherent in childbirth. More than 80% of women know something is “off” but do not bring up their symptoms to their clinician, according to the recommendation document.

“Coordination and team cohesiveness is not necessarily dependent on co-location,” Ms. Kendig said. “Virtual teams, where care is coordinated among providers at different locations, can also achieve positive outcomes.”

The follow-on to this – recognition and prevention – views every patient visit as an opportunity to draw a thorough picture of mental and physical health by taking a complete family and patient history, maintaining routine screening, and offering psychoeducation to patients and their families or others on whom they rely for emotional support.

When a woman does screen positive for perinatal mood or anxiety disorders, the next bundle offers a rough outline of a stage-based response for intervention and follow-up.

“Screening alone does not appear to improve pregnancy or maternal-child outcomes,” the authors wrote.

Several possible algorithms are included in the document, including for emergent mental health concerns such as suicidal or homicidal ideation.

The final domain relies on data capture, taking a systems approach to not only delivering care, but also improving it. This includes scheduling regular staff debriefings after severe maternal mental health crises, troubleshooting why some patients become lost to follow-up, and examining data to see patterns.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CORRECTION, 3/20/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the citation.

A new consensus bundle of recommendations calls on ob.gyns. to integrate mental health care into their care of pregnant and postpartum women.

The interdisciplinary Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care issued a consensus document summarizing existing recommendations on maternal mental health and pairing them with appropriate screening and other resources. The bundle of recommendations was jointly issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and other groups (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;129(3):422-430)*.

While no novel information is included in the bundle, the goal is to provide a streamlined document that pairs previous recommendations with resources and tools.

“Embedding a mental health professional with the women’s health care provider would seem to be the ideal, [but] in reality, this may not be available in every setting or geographic location,” Susan Kendig, JD, MSN, WHNP-BC, FAANP, policy director for the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, and one of the authors of the document, said in an interview. “The purpose of the consensus bundle is to provide a framework for women’s health care providers to use in developing a system of care that includes standardized risk assessment for existing or emerging mental health issues, strategies for brief interventions, identification of community resources available to the woman, and/or resources to support the provider in addressing the woman’s needs and facilitating appropriate referrals, and addressing emergencies to prevent harm.”

The framework is grouped in four domains: readiness, recognition and prevention, response, and reporting and systems learning.

Readiness is focused largely on setting up clinical and administrative protocols, including mental health screening that is seamlessly integrated into the patient visit, established algorithms that are triggered according to screening results, and designated staff to both educate colleagues on the protocols and to drive their implementation.

The goal for physicians in all settings, according to the authors, is to balance cost, availability of tools, ease of use, and the validity of the tools against the need to capture often unrecognized signs and symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, including changes in sleep patterns, appetite, or anxiety levels that often are attributed to the physiologic and neuroendocrinologic changes inherent in childbirth. More than 80% of women know something is “off” but do not bring up their symptoms to their clinician, according to the recommendation document.

“Coordination and team cohesiveness is not necessarily dependent on co-location,” Ms. Kendig said. “Virtual teams, where care is coordinated among providers at different locations, can also achieve positive outcomes.”

The follow-on to this – recognition and prevention – views every patient visit as an opportunity to draw a thorough picture of mental and physical health by taking a complete family and patient history, maintaining routine screening, and offering psychoeducation to patients and their families or others on whom they rely for emotional support.

When a woman does screen positive for perinatal mood or anxiety disorders, the next bundle offers a rough outline of a stage-based response for intervention and follow-up.

“Screening alone does not appear to improve pregnancy or maternal-child outcomes,” the authors wrote.

Several possible algorithms are included in the document, including for emergent mental health concerns such as suicidal or homicidal ideation.

The final domain relies on data capture, taking a systems approach to not only delivering care, but also improving it. This includes scheduling regular staff debriefings after severe maternal mental health crises, troubleshooting why some patients become lost to follow-up, and examining data to see patterns.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CORRECTION, 3/20/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the citation.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Guidelines needed for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study of pregnant Medicaid patients in Pennsylvania found that 12% filled prescriptions for opioids within 5 days of vaginal delivery, even though fewer than one-third of the women had pain-inducing conditions.

“Our study raises the question: Why is outpatient opioid use not rare after vaginal delivery?” lead author Marian Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “Outpatient opioid prescriptions after a hospitalization may be one potential pathway to opioid use disorder. I hope the study will prompt some thought about why opioids are being prescribed for women after vaginal delivery and how to best manage postdelivery pain. This is especially important in areas of the country that have extraordinarily high rates of opioid use disorder.”

A total of 12% of the women (18,131) filled an outpatient prescription for an opioid with 5 days of giving birth. Of those, just 28.2% (5,110) had one or more conditions that cause an increased level of pain after delivery, such as bilateral tubal ligation, certain kinds of lacerations, and episiotomy.

During the first 5 days after birth, the most commonly prescribed opioid was oxycodone-acetaminophen (53.3%), followed by acetaminophen-codeine (20.5%), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (19.6%).

Of the 18,131 women with an early postdelivery opioid prescription, 14% (2,592) filled at least one other opioid prescription within 6-60 days – that’s 1.6% of all the women in the study.

“On a positive note, we saw the supply of opioid prescriptions was generally short at 3-7 days,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

The researchers linked tobacco use and a mental health condition (both adjusted odds ratio 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.4) to a higher risk of filling a prescription without being diagnosed with a pain-causing disorder. They also found an association between substance use disorder (not related to opioids) and a higher risk of these types of prescriptions, but only for filling a second opioid prescription in the 6-60 day period (aOR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6).

The researchers called for national guidelines regarding the use of opioids after birth.

“Several organizations have developed opioid prescribing guidelines for chronic and acute pain,” Dr. Jarlenski said. “These guidelines are necessary because the risk of opioid use disorder and subsequent overdose events is well established. Although delivery is the most common reason for hospitalization in the United States, there are no national guidelines for outpatient opioid use after vaginal delivery.”

The study was partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 12% of women on Medicaid filled opioid prescriptions within 5 days of delivery; just 28.2% of those patients had a pain-inducing condition.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 164,720 women enrolled in Medicaid in Pennsylvania who delivered live-born babies vaginally from 2008 to 2013.

Disclosures: The study is partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Review offers reassurance on prenatal Tdap vaccination safety

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60.

Data source: A systematic review of 21 studies.

Disclosures: Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Hypertensive disease of pregnancy linked to earlier mortality

LAS VEGAS – Women who develop any form of hypertensive disease during pregnancy have a significantly increased mortality rate until they reach age 50, compared with women without the condition.

The findings, presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, are based on a review of more than 2 million mothers who delivered babies in Utah during 1939-2012.

The relatively increased mortality rate linked with hypertensive disease of pregnancy (HDP) reached its peak during the first decade immediately following the index delivery and was dramatically higher in women for whom the index HDP was preceded by at least one earlier HDP. Increased mortality was especially elevated for certain types of deaths including stroke, diabetes, circulatory disease, and ischemic heart disease, said Lauren Theilen, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine researcher at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

She calculated that during the decade following an index case of HDP, life expectancy among mothers who had two or more HDP-affected pregnancies was about 49 years, life expectancy among women with a history of one HDP was 52 years, and postpartum women without HDP had a life expectancy of 55 years.

The data came from 2,083,331 singleton pregnancies delivered in Utah during 1939-2012 where the mother remained in Utah for at least 1 year following delivery. From this group, Dr. Theilen and her associates identified 67,384 women (3%) with HDP, including 49,598 women without a prior history of HDP and 7,786 with at least one prior HDP pregnancy. They included four different diagnoses as HDP: gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count), or eclampsia.

The analysis excluded women with chronic hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome, pregestational diabetes, or chronic kidney disease. It also excluded women who died within a year of the index delivery. For each of the included 67,384 cases with HDP, the researchers selected two controls with a delivery unaffected by HDP and matched them to a case by age, year of childbirth, and parity.

The women in the study were 26 years old on average. Gestational age at delivery among the HDP cases averaged 1 week less than among the controls, 37.8 weeks compared with 38.9 weeks, a statistically significant difference. Average birth weight also differed by a significant amount, 3,079 grams in the HDP neonates and 3,319 grams in the control newborns. During follow-up, 8% of the HDP women died, compared with 6% of the control women.

Analysis showed that relative mortality rates in HDP women were especially elevated for certain types of death: endocrine and metabolic, circulatory, genitourinary, infectious disease, and digestive. In most types of death, the increased risk linked with HDP was markedly higher in the women with recurrent HDP.

Dr. Theilen reported the relative risks of death for certain specific mortality causes (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan;216[1][suppl]:S32-3). In women with a single index case of HDP, the mortality rate compared to women with no HDP was threefold higher for diabetes, twofold higher for ischemic heart disease, and 85% higher for stroke. In women with recurrent HDP, the relative mortality risks were fourfold higher for diabetes, threefold higher for ischemic heart disease, and fivefold higher for stroke.

For all causes of death except stroke, the increased relative risk from HDP existed only for women younger than 51 years. Once HDP women passed the age of 50, their excess mortality risk was substantially muted, even in women with recurrent HDP. But for stroke mortality, the added risk persisted among older women with a history of at least two HDPs. In this subgroup, stroke deaths were nearly fourfold higher than in the matched controls.

Dr. Theilen reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The findings Dr. Theilen and her associates made in this study confirm results reported several decades ago that first established a link between hypertensive disease of pregnancy (HDP) and significantly reduced life expectancy. We have known for some time that HDP identifies women with a long-term mortality risk. The real question is: Can we ameliorate the risk linked with HDP?

We know that HDP requires acute management, but we are not sure how to best manage these women once they have delivered. To address that, we need prospective studies.

Not all women who experience HDP receive appropriate follow-up after delivery. We need to ensure a better handoff of women who developed HDP from the physicians who cared for these women during pregnancy to the physicians who care for these women postpartum and during the balance of their life. Ideally, a primary care physician should closely follow and manage blood pressure and other risk factors of HDP women once they are no longer pregnant.

Mary E. D’Alton, MD , is professor and chair of ob.gyn. at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. She is on the advisory board of Merck for Mothers. She made these comments in an interview.

The findings Dr. Theilen and her associates made in this study confirm results reported several decades ago that first established a link between hypertensive disease of pregnancy (HDP) and significantly reduced life expectancy. We have known for some time that HDP identifies women with a long-term mortality risk. The real question is: Can we ameliorate the risk linked with HDP?

We know that HDP requires acute management, but we are not sure how to best manage these women once they have delivered. To address that, we need prospective studies.

Not all women who experience HDP receive appropriate follow-up after delivery. We need to ensure a better handoff of women who developed HDP from the physicians who cared for these women during pregnancy to the physicians who care for these women postpartum and during the balance of their life. Ideally, a primary care physician should closely follow and manage blood pressure and other risk factors of HDP women once they are no longer pregnant.

Mary E. D’Alton, MD , is professor and chair of ob.gyn. at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. She is on the advisory board of Merck for Mothers. She made these comments in an interview.

The findings Dr. Theilen and her associates made in this study confirm results reported several decades ago that first established a link between hypertensive disease of pregnancy (HDP) and significantly reduced life expectancy. We have known for some time that HDP identifies women with a long-term mortality risk. The real question is: Can we ameliorate the risk linked with HDP?

We know that HDP requires acute management, but we are not sure how to best manage these women once they have delivered. To address that, we need prospective studies.

Not all women who experience HDP receive appropriate follow-up after delivery. We need to ensure a better handoff of women who developed HDP from the physicians who cared for these women during pregnancy to the physicians who care for these women postpartum and during the balance of their life. Ideally, a primary care physician should closely follow and manage blood pressure and other risk factors of HDP women once they are no longer pregnant.

Mary E. D’Alton, MD , is professor and chair of ob.gyn. at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. She is on the advisory board of Merck for Mothers. She made these comments in an interview.

LAS VEGAS – Women who develop any form of hypertensive disease during pregnancy have a significantly increased mortality rate until they reach age 50, compared with women without the condition.

The findings, presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, are based on a review of more than 2 million mothers who delivered babies in Utah during 1939-2012.

The relatively increased mortality rate linked with hypertensive disease of pregnancy (HDP) reached its peak during the first decade immediately following the index delivery and was dramatically higher in women for whom the index HDP was preceded by at least one earlier HDP. Increased mortality was especially elevated for certain types of deaths including stroke, diabetes, circulatory disease, and ischemic heart disease, said Lauren Theilen, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine researcher at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

She calculated that during the decade following an index case of HDP, life expectancy among mothers who had two or more HDP-affected pregnancies was about 49 years, life expectancy among women with a history of one HDP was 52 years, and postpartum women without HDP had a life expectancy of 55 years.

The data came from 2,083,331 singleton pregnancies delivered in Utah during 1939-2012 where the mother remained in Utah for at least 1 year following delivery. From this group, Dr. Theilen and her associates identified 67,384 women (3%) with HDP, including 49,598 women without a prior history of HDP and 7,786 with at least one prior HDP pregnancy. They included four different diagnoses as HDP: gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count), or eclampsia.

The analysis excluded women with chronic hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome, pregestational diabetes, or chronic kidney disease. It also excluded women who died within a year of the index delivery. For each of the included 67,384 cases with HDP, the researchers selected two controls with a delivery unaffected by HDP and matched them to a case by age, year of childbirth, and parity.

The women in the study were 26 years old on average. Gestational age at delivery among the HDP cases averaged 1 week less than among the controls, 37.8 weeks compared with 38.9 weeks, a statistically significant difference. Average birth weight also differed by a significant amount, 3,079 grams in the HDP neonates and 3,319 grams in the control newborns. During follow-up, 8% of the HDP women died, compared with 6% of the control women.

Analysis showed that relative mortality rates in HDP women were especially elevated for certain types of death: endocrine and metabolic, circulatory, genitourinary, infectious disease, and digestive. In most types of death, the increased risk linked with HDP was markedly higher in the women with recurrent HDP.

Dr. Theilen reported the relative risks of death for certain specific mortality causes (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan;216[1][suppl]:S32-3). In women with a single index case of HDP, the mortality rate compared to women with no HDP was threefold higher for diabetes, twofold higher for ischemic heart disease, and 85% higher for stroke. In women with recurrent HDP, the relative mortality risks were fourfold higher for diabetes, threefold higher for ischemic heart disease, and fivefold higher for stroke.

For all causes of death except stroke, the increased relative risk from HDP existed only for women younger than 51 years. Once HDP women passed the age of 50, their excess mortality risk was substantially muted, even in women with recurrent HDP. But for stroke mortality, the added risk persisted among older women with a history of at least two HDPs. In this subgroup, stroke deaths were nearly fourfold higher than in the matched controls.

Dr. Theilen reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Women who develop any form of hypertensive disease during pregnancy have a significantly increased mortality rate until they reach age 50, compared with women without the condition.

The findings, presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, are based on a review of more than 2 million mothers who delivered babies in Utah during 1939-2012.

The relatively increased mortality rate linked with hypertensive disease of pregnancy (HDP) reached its peak during the first decade immediately following the index delivery and was dramatically higher in women for whom the index HDP was preceded by at least one earlier HDP. Increased mortality was especially elevated for certain types of deaths including stroke, diabetes, circulatory disease, and ischemic heart disease, said Lauren Theilen, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine researcher at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

She calculated that during the decade following an index case of HDP, life expectancy among mothers who had two or more HDP-affected pregnancies was about 49 years, life expectancy among women with a history of one HDP was 52 years, and postpartum women without HDP had a life expectancy of 55 years.

The data came from 2,083,331 singleton pregnancies delivered in Utah during 1939-2012 where the mother remained in Utah for at least 1 year following delivery. From this group, Dr. Theilen and her associates identified 67,384 women (3%) with HDP, including 49,598 women without a prior history of HDP and 7,786 with at least one prior HDP pregnancy. They included four different diagnoses as HDP: gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count), or eclampsia.

The analysis excluded women with chronic hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome, pregestational diabetes, or chronic kidney disease. It also excluded women who died within a year of the index delivery. For each of the included 67,384 cases with HDP, the researchers selected two controls with a delivery unaffected by HDP and matched them to a case by age, year of childbirth, and parity.

The women in the study were 26 years old on average. Gestational age at delivery among the HDP cases averaged 1 week less than among the controls, 37.8 weeks compared with 38.9 weeks, a statistically significant difference. Average birth weight also differed by a significant amount, 3,079 grams in the HDP neonates and 3,319 grams in the control newborns. During follow-up, 8% of the HDP women died, compared with 6% of the control women.

Analysis showed that relative mortality rates in HDP women were especially elevated for certain types of death: endocrine and metabolic, circulatory, genitourinary, infectious disease, and digestive. In most types of death, the increased risk linked with HDP was markedly higher in the women with recurrent HDP.

Dr. Theilen reported the relative risks of death for certain specific mortality causes (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan;216[1][suppl]:S32-3). In women with a single index case of HDP, the mortality rate compared to women with no HDP was threefold higher for diabetes, twofold higher for ischemic heart disease, and 85% higher for stroke. In women with recurrent HDP, the relative mortality risks were fourfold higher for diabetes, threefold higher for ischemic heart disease, and fivefold higher for stroke.

For all causes of death except stroke, the increased relative risk from HDP existed only for women younger than 51 years. Once HDP women passed the age of 50, their excess mortality risk was substantially muted, even in women with recurrent HDP. But for stroke mortality, the added risk persisted among older women with a history of at least two HDPs. In this subgroup, stroke deaths were nearly fourfold higher than in the matched controls.

Dr. Theilen reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Postpartum life expectancy was 49 years in women with two or more hypertensive pregnancies and 55 years in women without hypertension.

Data source: Retrospective, case-control study of 2,083,331 singleton pregnancies delivered in Utah during 1939-2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Theilen reported having no financial disclosures.

Aspirin reduces recurrent preeclampsia in real-world study

LAS VEGAS – Using low-dose aspirin during pregnancy significantly reduced the risk of recurrent preeclampsia, according to results of a new study.

“The net benefit of aspirin is substantial,” Mary Catherine Tolcher, MD, the study’s lead author said. “The number needed to treat to prevent one case of recurrent preeclampsia is six... The cost of daily low-dose aspirin for the duration of one pregnancy is about $4.00. Comparatively, the cost to prevent one case of eclampsia is approximately $21,000.”

Dr. Tolcher, a postdoctorate fellow in ob.gyn. at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and her colleagues found a total of 417 at-risk women in the institution’s labor and delivery database during the August 2011–June 2016 study period; 284 were identified before the guidelines were implemented in 2014, while 133 women were identified as high-risk after guideline implementation.

While nearly one-third (32.4%) of women with a history of preeclampsia had a recurrence in the before group, the recurrence rate fell to 16.5% in the after group, who had been instructed to take low-dose aspirin in accordance with the guidelines. When the investigators calculated the fully adjusted odds ratio for recurrent preeclampsia, they found a reduction of about 30% in recurrent preeclampsia [aOR, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.52-0.95].

“This decrease is greater than the approximately 10 to 15 percent reduction that has been previously reported in clinical trials, and different from the meta-analysis that prompted the national recommendations,” Dr. Tolcher said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

She and her colleagues hypothesize that the greater effect size may be attributable to limiting the study population to the higher-risk group of women with a history of preeclampsia. Alternatively, she said, aspirin’s pharmacodynamics can differ by race, so racial differences between study populations may also be at play.