User login

Zika cases in pregnant women hit new weekly high

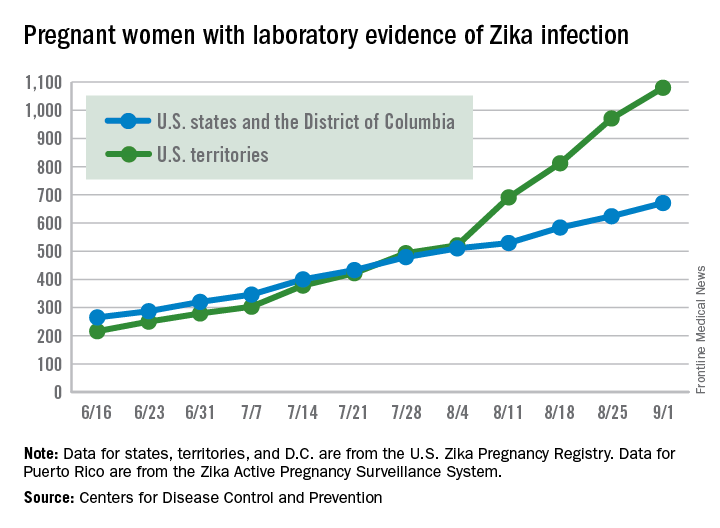

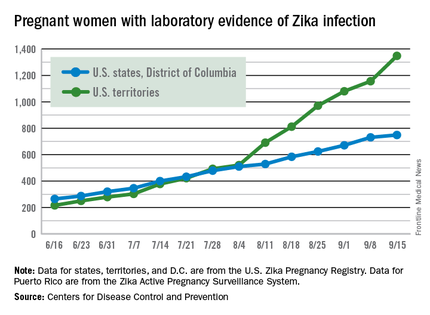

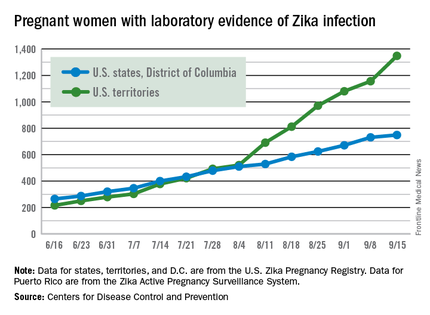

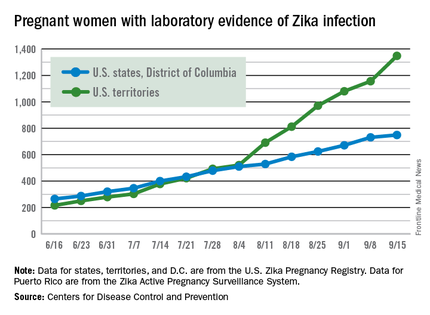

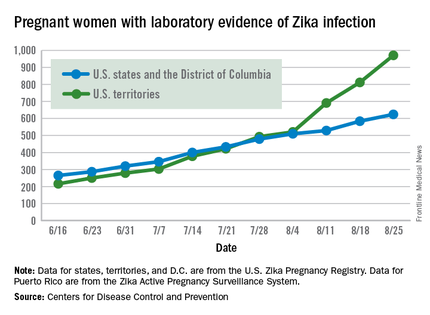

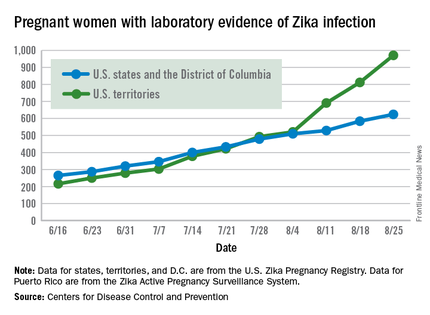

The weekly number of pregnant women in the United States with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection topped 200 for the first time during the week ending Sept. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With the 50 states and the District of Columbia reporting 18 new cases for the week and the U.S. territories reporting 192, there were 210 more pregnant women with Zika for the week ending Sept. 15, the CDC reported Sept. 22. The previous weekly high had been 199 for the week ending Aug. 25.

The CDC also reported two new cases of liveborn infants – both in the 50 states and D.C. – with Zika-related birth defects. No infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported in the territories for the week, and there were no new reports of pregnancy losses related to Zika. The number of pregnancy losses holds at six for the year so far, but the number of U.S. liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects is now 21, with 20 cases in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

There were 182 new cases of Zika infection reported among all Americans in the states/D.C. for the week ending Sept. 21, along with 2,083 new cases in the territories – almost all in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC noted Sept. 22. The U.S. total for 2015-2016 is 23,135 cases: 3,358 reported in the states/D.C. and 19,777 in the territories. Puerto Rico represents 98% of the territorial total, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

The weekly number of pregnant women in the United States with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection topped 200 for the first time during the week ending Sept. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With the 50 states and the District of Columbia reporting 18 new cases for the week and the U.S. territories reporting 192, there were 210 more pregnant women with Zika for the week ending Sept. 15, the CDC reported Sept. 22. The previous weekly high had been 199 for the week ending Aug. 25.

The CDC also reported two new cases of liveborn infants – both in the 50 states and D.C. – with Zika-related birth defects. No infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported in the territories for the week, and there were no new reports of pregnancy losses related to Zika. The number of pregnancy losses holds at six for the year so far, but the number of U.S. liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects is now 21, with 20 cases in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

There were 182 new cases of Zika infection reported among all Americans in the states/D.C. for the week ending Sept. 21, along with 2,083 new cases in the territories – almost all in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC noted Sept. 22. The U.S. total for 2015-2016 is 23,135 cases: 3,358 reported in the states/D.C. and 19,777 in the territories. Puerto Rico represents 98% of the territorial total, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

The weekly number of pregnant women in the United States with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection topped 200 for the first time during the week ending Sept. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With the 50 states and the District of Columbia reporting 18 new cases for the week and the U.S. territories reporting 192, there were 210 more pregnant women with Zika for the week ending Sept. 15, the CDC reported Sept. 22. The previous weekly high had been 199 for the week ending Aug. 25.

The CDC also reported two new cases of liveborn infants – both in the 50 states and D.C. – with Zika-related birth defects. No infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported in the territories for the week, and there were no new reports of pregnancy losses related to Zika. The number of pregnancy losses holds at six for the year so far, but the number of U.S. liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects is now 21, with 20 cases in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

There were 182 new cases of Zika infection reported among all Americans in the states/D.C. for the week ending Sept. 21, along with 2,083 new cases in the territories – almost all in Puerto Rico, which continues to retroactively report cases, the CDC noted Sept. 22. The U.S. total for 2015-2016 is 23,135 cases: 3,358 reported in the states/D.C. and 19,777 in the territories. Puerto Rico represents 98% of the territorial total, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Obstetric VTE safety recommendations stress routine risk assessment

Routine thromboembolism risk assessment and use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis is an important part of obstetrics care, according to new recommendations from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety.

Although obstetric venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, prophylaxis recommendations are varied and nonspecific across obstetric organizations. The new maternity safety bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS) aims to eliminate some of the confusion.

“Based on increasing maternal risk of obstetric venous thromboembolism in the United States, the failure of current strategies to decrease venous thromboembolism as a proportionate cause of maternal death, and observational evidence from the United Kingdom that risk factor–based prophylaxis may reduce risk, the NPMS working group has interpreted current epidemiology and clinical research evidence to support routine thromboembolism risk assessment and consideration of more extensive risk factor–based prophylaxis,” the authors wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688-98).

In the recommendations, prophylactic management of obstetric thromboembolism is organized into four categories: readiness, recognition, response, and reporting and systems learning.

The readiness component includes a recommendation to use a standard thromboembolism risk assessment tool at the first prenatal visit, all antepartum admissions, immediately post partum during childbirth hospitalization, and on discharge from the hospital after a birth. The Caprini and Padua scoring systems, which are tools designed for nonobstetric hospitalized patients, can be modified for obstetric patients, according to the recommendations.

The recognition component of the bundle emphasizes the use of education and guidelines to help physicians identify obstetric patients at risk for thromboembolism. The response component proposes a thromboembolism risk assessment at the first prenatal visit, followed by the use of standardized recommendations for mechanical thromboprophylaxis, dosing of prophylactic and therapeutic pharmacologic anticoagulation, and appropriate timing of pharmacologic prophylaxis with neuraxial anesthesia.

The reporting and systems learning component calls for reviews of a sample of a facility’s obstetric population to determine comorbid risk factors for VTE, followed by routine auditing of records to monitor risk assessment programs and patient care.

The NPMS suggests applying the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations for hospitalized, nonsurgical patients to pregnant women and postpartum women who have had a vaginal birth. However, they recommend using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with thrombophilia.

The NPMS also recommends that women receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis plus low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, should discontinue aspirin at 35-36 weeks of gestation.

“Given the wide diversity of birthing facilities, a single national protocol is not recommended; instead, each facility should adapt a single protocol to improve maternal safety based on its patient population and resources,” the NPMS members wrote.

The NPMS is a joint effort including leaders from a range of women’s health care organizations, hospitals, professional societies, and regulators.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Routine thromboembolism risk assessment and use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis is an important part of obstetrics care, according to new recommendations from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety.

Although obstetric venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, prophylaxis recommendations are varied and nonspecific across obstetric organizations. The new maternity safety bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS) aims to eliminate some of the confusion.

“Based on increasing maternal risk of obstetric venous thromboembolism in the United States, the failure of current strategies to decrease venous thromboembolism as a proportionate cause of maternal death, and observational evidence from the United Kingdom that risk factor–based prophylaxis may reduce risk, the NPMS working group has interpreted current epidemiology and clinical research evidence to support routine thromboembolism risk assessment and consideration of more extensive risk factor–based prophylaxis,” the authors wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688-98).

In the recommendations, prophylactic management of obstetric thromboembolism is organized into four categories: readiness, recognition, response, and reporting and systems learning.

The readiness component includes a recommendation to use a standard thromboembolism risk assessment tool at the first prenatal visit, all antepartum admissions, immediately post partum during childbirth hospitalization, and on discharge from the hospital after a birth. The Caprini and Padua scoring systems, which are tools designed for nonobstetric hospitalized patients, can be modified for obstetric patients, according to the recommendations.

The recognition component of the bundle emphasizes the use of education and guidelines to help physicians identify obstetric patients at risk for thromboembolism. The response component proposes a thromboembolism risk assessment at the first prenatal visit, followed by the use of standardized recommendations for mechanical thromboprophylaxis, dosing of prophylactic and therapeutic pharmacologic anticoagulation, and appropriate timing of pharmacologic prophylaxis with neuraxial anesthesia.

The reporting and systems learning component calls for reviews of a sample of a facility’s obstetric population to determine comorbid risk factors for VTE, followed by routine auditing of records to monitor risk assessment programs and patient care.

The NPMS suggests applying the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations for hospitalized, nonsurgical patients to pregnant women and postpartum women who have had a vaginal birth. However, they recommend using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with thrombophilia.

The NPMS also recommends that women receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis plus low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, should discontinue aspirin at 35-36 weeks of gestation.

“Given the wide diversity of birthing facilities, a single national protocol is not recommended; instead, each facility should adapt a single protocol to improve maternal safety based on its patient population and resources,” the NPMS members wrote.

The NPMS is a joint effort including leaders from a range of women’s health care organizations, hospitals, professional societies, and regulators.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Routine thromboembolism risk assessment and use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis is an important part of obstetrics care, according to new recommendations from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety.

Although obstetric venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, prophylaxis recommendations are varied and nonspecific across obstetric organizations. The new maternity safety bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS) aims to eliminate some of the confusion.

“Based on increasing maternal risk of obstetric venous thromboembolism in the United States, the failure of current strategies to decrease venous thromboembolism as a proportionate cause of maternal death, and observational evidence from the United Kingdom that risk factor–based prophylaxis may reduce risk, the NPMS working group has interpreted current epidemiology and clinical research evidence to support routine thromboembolism risk assessment and consideration of more extensive risk factor–based prophylaxis,” the authors wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688-98).

In the recommendations, prophylactic management of obstetric thromboembolism is organized into four categories: readiness, recognition, response, and reporting and systems learning.

The readiness component includes a recommendation to use a standard thromboembolism risk assessment tool at the first prenatal visit, all antepartum admissions, immediately post partum during childbirth hospitalization, and on discharge from the hospital after a birth. The Caprini and Padua scoring systems, which are tools designed for nonobstetric hospitalized patients, can be modified for obstetric patients, according to the recommendations.

The recognition component of the bundle emphasizes the use of education and guidelines to help physicians identify obstetric patients at risk for thromboembolism. The response component proposes a thromboembolism risk assessment at the first prenatal visit, followed by the use of standardized recommendations for mechanical thromboprophylaxis, dosing of prophylactic and therapeutic pharmacologic anticoagulation, and appropriate timing of pharmacologic prophylaxis with neuraxial anesthesia.

The reporting and systems learning component calls for reviews of a sample of a facility’s obstetric population to determine comorbid risk factors for VTE, followed by routine auditing of records to monitor risk assessment programs and patient care.

The NPMS suggests applying the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations for hospitalized, nonsurgical patients to pregnant women and postpartum women who have had a vaginal birth. However, they recommend using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with thrombophilia.

The NPMS also recommends that women receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis plus low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, should discontinue aspirin at 35-36 weeks of gestation.

“Given the wide diversity of birthing facilities, a single national protocol is not recommended; instead, each facility should adapt a single protocol to improve maternal safety based on its patient population and resources,” the NPMS members wrote.

The NPMS is a joint effort including leaders from a range of women’s health care organizations, hospitals, professional societies, and regulators.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Case-control study points to Zika virus as cause of microcephaly

A new study from Brazil demonstrates that microcephaly is strongly associated with congenital Zika virus infections, offering case-control evidence of a causal relationship.

“This is the first case-control study to examine the association between Zika virus and microcephaly using molecular and serological analysis to identify Zika virus in cases and controls at the time of birth,” Thalia Velho Barreto de Araújo, PhD, of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, said in a statement. “Our findings suggest that Zika virus should be officially added to the list of congenital infections alongside toxoplasmosis, syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes. However, many questions still remain to be answered including the role of previous dengue infection.”

In April, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly, following a systematic review of the available Zika virus research.

In the current study, the investigators looked for cases of infants born with microcephaly at eight public hospitals in Pernambuco, a state in northeastern Brazil. Thirty-two such cases were included for analysis, along with 62 controls. All infants in the study were born between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30318-8).

Zika-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were conducted on serum from both microcephaly and control infants, and cerebrospinal fluid samples only from infants with microcephaly. Mothers underwent serum testing for Zika virus and dengue virus via plaque reduction neutralization assay testing. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated to determine the association between congenital Zika virus and microcephaly.

Of the 30 women who gave birth to infants with microcephaly, 24 (80%) had Zika virus infections, compared with 39 of the 61 women (64%) in the control group (P = .12). Additionally, while 13 of the 32 infants born with microcephaly had Zika virus infections confirmed by laboratory testing, none of the infants in the control group had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection.

A total of 7 out 27 infants with microcephaly who underwent CT scans showed signs of brain abnormalities, suggesting that “congenital Zika virus syndrome can be present in neonates with microcephaly and no radiological brain abnormalities,” according to the investigators.

While the study is still ongoing, the investigators called for more research to assess other potential risk factors and to confirm the strength of association in a larger sample size, as well as to gauge the significance and role of previous dengue infections in the mothers.

The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study from Brazil demonstrates that microcephaly is strongly associated with congenital Zika virus infections, offering case-control evidence of a causal relationship.

“This is the first case-control study to examine the association between Zika virus and microcephaly using molecular and serological analysis to identify Zika virus in cases and controls at the time of birth,” Thalia Velho Barreto de Araújo, PhD, of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, said in a statement. “Our findings suggest that Zika virus should be officially added to the list of congenital infections alongside toxoplasmosis, syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes. However, many questions still remain to be answered including the role of previous dengue infection.”

In April, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly, following a systematic review of the available Zika virus research.

In the current study, the investigators looked for cases of infants born with microcephaly at eight public hospitals in Pernambuco, a state in northeastern Brazil. Thirty-two such cases were included for analysis, along with 62 controls. All infants in the study were born between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30318-8).

Zika-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were conducted on serum from both microcephaly and control infants, and cerebrospinal fluid samples only from infants with microcephaly. Mothers underwent serum testing for Zika virus and dengue virus via plaque reduction neutralization assay testing. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated to determine the association between congenital Zika virus and microcephaly.

Of the 30 women who gave birth to infants with microcephaly, 24 (80%) had Zika virus infections, compared with 39 of the 61 women (64%) in the control group (P = .12). Additionally, while 13 of the 32 infants born with microcephaly had Zika virus infections confirmed by laboratory testing, none of the infants in the control group had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection.

A total of 7 out 27 infants with microcephaly who underwent CT scans showed signs of brain abnormalities, suggesting that “congenital Zika virus syndrome can be present in neonates with microcephaly and no radiological brain abnormalities,” according to the investigators.

While the study is still ongoing, the investigators called for more research to assess other potential risk factors and to confirm the strength of association in a larger sample size, as well as to gauge the significance and role of previous dengue infections in the mothers.

The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A new study from Brazil demonstrates that microcephaly is strongly associated with congenital Zika virus infections, offering case-control evidence of a causal relationship.

“This is the first case-control study to examine the association between Zika virus and microcephaly using molecular and serological analysis to identify Zika virus in cases and controls at the time of birth,” Thalia Velho Barreto de Araújo, PhD, of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, said in a statement. “Our findings suggest that Zika virus should be officially added to the list of congenital infections alongside toxoplasmosis, syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes. However, many questions still remain to be answered including the role of previous dengue infection.”

In April, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly, following a systematic review of the available Zika virus research.

In the current study, the investigators looked for cases of infants born with microcephaly at eight public hospitals in Pernambuco, a state in northeastern Brazil. Thirty-two such cases were included for analysis, along with 62 controls. All infants in the study were born between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30318-8).

Zika-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were conducted on serum from both microcephaly and control infants, and cerebrospinal fluid samples only from infants with microcephaly. Mothers underwent serum testing for Zika virus and dengue virus via plaque reduction neutralization assay testing. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated to determine the association between congenital Zika virus and microcephaly.

Of the 30 women who gave birth to infants with microcephaly, 24 (80%) had Zika virus infections, compared with 39 of the 61 women (64%) in the control group (P = .12). Additionally, while 13 of the 32 infants born with microcephaly had Zika virus infections confirmed by laboratory testing, none of the infants in the control group had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection.

A total of 7 out 27 infants with microcephaly who underwent CT scans showed signs of brain abnormalities, suggesting that “congenital Zika virus syndrome can be present in neonates with microcephaly and no radiological brain abnormalities,” according to the investigators.

While the study is still ongoing, the investigators called for more research to assess other potential risk factors and to confirm the strength of association in a larger sample size, as well as to gauge the significance and role of previous dengue infections in the mothers.

The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: The current microcephaly epidemic is a result of congenital Zika virus infection.

Major finding: In total, 41% of infants born with microcephaly had laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection, compared with none of the infants in the control group.

Data source: Prospective, ongoing case-control study of 32 microcephaly cases and 62 controls at eight hospitals in Brazil between Jan. 15, 2016 and May 2, 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations. The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Number of Zika-infected pregnancies jumps in states/D.C.

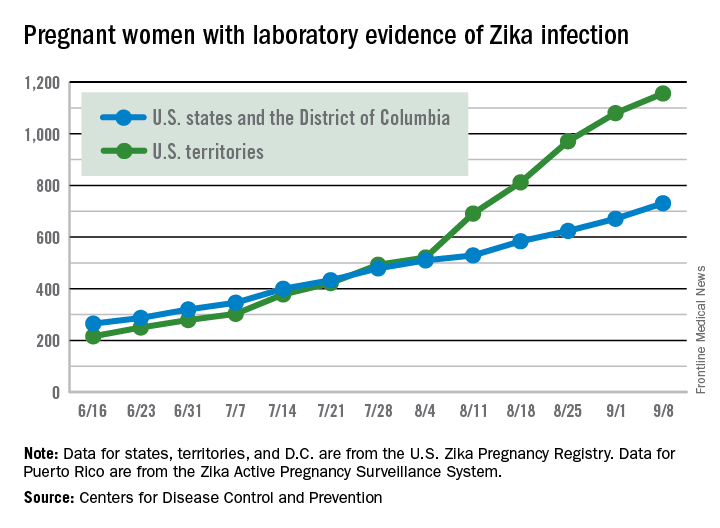

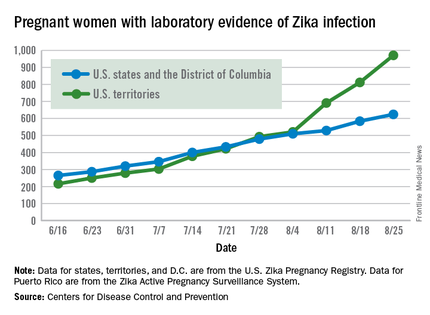

There were 60 more pregnant women in the 50 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 8, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That is the largest weekly increase yet among that population, and it brings the total number of Zika-infected pregnant women to 731 in the 50 states and D.C. so far in 2016. The U.S. territories reported 76 new cases for the week ending Sept. 8, for a territorial total of 1,156 and a combined U.S. total of 1,887 pregnant women with Zika virus, the CDC reported Sept. 15.

For the second week in a row, a liveborn infant with Zika-related birth defects was born in the 50 states/D.C. The total is now 19 for the year: 18 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories. There were no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects, so the number holds at six for the year: five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

There were 60 more pregnant women in the 50 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 8, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That is the largest weekly increase yet among that population, and it brings the total number of Zika-infected pregnant women to 731 in the 50 states and D.C. so far in 2016. The U.S. territories reported 76 new cases for the week ending Sept. 8, for a territorial total of 1,156 and a combined U.S. total of 1,887 pregnant women with Zika virus, the CDC reported Sept. 15.

For the second week in a row, a liveborn infant with Zika-related birth defects was born in the 50 states/D.C. The total is now 19 for the year: 18 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories. There were no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects, so the number holds at six for the year: five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

There were 60 more pregnant women in the 50 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 8, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That is the largest weekly increase yet among that population, and it brings the total number of Zika-infected pregnant women to 731 in the 50 states and D.C. so far in 2016. The U.S. territories reported 76 new cases for the week ending Sept. 8, for a territorial total of 1,156 and a combined U.S. total of 1,887 pregnant women with Zika virus, the CDC reported Sept. 15.

For the second week in a row, a liveborn infant with Zika-related birth defects was born in the 50 states/D.C. The total is now 19 for the year: 18 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories. There were no new pregnancy losses with Zika-related birth defects, so the number holds at six for the year: five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Both prepregnancy and gestational diabetes bode ill for babies

MUNICH – Pregestational maternal diabetes is even riskier for newborns than gestational diabetes, increasing the chance of neonatal hypoglycemia by 36 times over a normal pregnancy.

Baby’s blood sugar isn’t the only thing in danger, though, Basilio Pintaudi, MD, said at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes conference. Women with prepregnancy diabetes are significantly more likely to have babies that are either small or large for gestational age; become jaundiced; have congenital malformations; and experience respiratory distress, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, said Dr. Pintaudi of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital, Milan.

“Everyone involved in the care of pregnant women should realize there are very real risks for severe neonatal outcomes, for all forms of diabetes – whether it exists before pregnancy or develops during pregnancy,” Dr. Pintaudi said in an interview. “It’s very important to detect both prepregnancy and gestational diabetes early and optimize maternal glucose levels as quickly as possible.”

He and his colleagues studied outcomes in 135,000 pregnancies included in an administrative database in the Italian Puglia region from 2002 to 2012. They found 1,357 singleton pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes, and 234 by pregestational diabetes. They computed the risks of a number of neonatal outcomes in a multivariate analysis that controlled for hypertensive and thyroid disorders and for several drugs, including antithrombotics, antiplatelets, and ticlopidine. These drugs were chosen as indicators of high-risk pregnancy.

Both gestational and pregestational diabetes were associated with significantly higher risks of neonatal hypoglycemia (odds ratios, 10 and 36, respectively). They were also associated with significantly increased risks of a small for gestational age infant (ORs, 1.7 and 5.8), and large for gestational age infant (ORs, 1.7 and 7.9).

The risk of jaundice was also increased for both gestational and pregestational diabetes (ORs, 1.7 and 2.6).

Fetal malformations were more common in both disorders (ORs, 2.2 and 3.5). The database didn’t include specifics on what type of malformations occurred, but Dr. Pintaudi said prior studies show increases in cardiac and neural tube defects. This problem in particular illustrates the need for early screening and management of pregestational diabetes, he said in an interview.

“The pathophysiology of these malformations is such that they occur in the very early stages of pregnancy, before some women even know they might be pregnant,” he said.

Hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia of the newborn were more likely in both gestational and pregestational diabetes (ORs, 1.8 and 9.2), as was Cesarean delivery (ORs, 1.9 and 8.5).

Pregestational diabetes alone was also associated with an increased risk of respiratory distress (OR, 2.7) and polyhydramnios (OR, 46.5).

Dr. Pintaudi said that Italy does not recommend universal diabetes screening for women who are or wish to become pregnant. The first evaluation occurs at 16-18 weeks’ gestation, with a repeat evaluation at 24-28 weeks.

He had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MUNICH – Pregestational maternal diabetes is even riskier for newborns than gestational diabetes, increasing the chance of neonatal hypoglycemia by 36 times over a normal pregnancy.

Baby’s blood sugar isn’t the only thing in danger, though, Basilio Pintaudi, MD, said at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes conference. Women with prepregnancy diabetes are significantly more likely to have babies that are either small or large for gestational age; become jaundiced; have congenital malformations; and experience respiratory distress, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, said Dr. Pintaudi of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital, Milan.

“Everyone involved in the care of pregnant women should realize there are very real risks for severe neonatal outcomes, for all forms of diabetes – whether it exists before pregnancy or develops during pregnancy,” Dr. Pintaudi said in an interview. “It’s very important to detect both prepregnancy and gestational diabetes early and optimize maternal glucose levels as quickly as possible.”

He and his colleagues studied outcomes in 135,000 pregnancies included in an administrative database in the Italian Puglia region from 2002 to 2012. They found 1,357 singleton pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes, and 234 by pregestational diabetes. They computed the risks of a number of neonatal outcomes in a multivariate analysis that controlled for hypertensive and thyroid disorders and for several drugs, including antithrombotics, antiplatelets, and ticlopidine. These drugs were chosen as indicators of high-risk pregnancy.

Both gestational and pregestational diabetes were associated with significantly higher risks of neonatal hypoglycemia (odds ratios, 10 and 36, respectively). They were also associated with significantly increased risks of a small for gestational age infant (ORs, 1.7 and 5.8), and large for gestational age infant (ORs, 1.7 and 7.9).

The risk of jaundice was also increased for both gestational and pregestational diabetes (ORs, 1.7 and 2.6).

Fetal malformations were more common in both disorders (ORs, 2.2 and 3.5). The database didn’t include specifics on what type of malformations occurred, but Dr. Pintaudi said prior studies show increases in cardiac and neural tube defects. This problem in particular illustrates the need for early screening and management of pregestational diabetes, he said in an interview.

“The pathophysiology of these malformations is such that they occur in the very early stages of pregnancy, before some women even know they might be pregnant,” he said.

Hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia of the newborn were more likely in both gestational and pregestational diabetes (ORs, 1.8 and 9.2), as was Cesarean delivery (ORs, 1.9 and 8.5).

Pregestational diabetes alone was also associated with an increased risk of respiratory distress (OR, 2.7) and polyhydramnios (OR, 46.5).

Dr. Pintaudi said that Italy does not recommend universal diabetes screening for women who are or wish to become pregnant. The first evaluation occurs at 16-18 weeks’ gestation, with a repeat evaluation at 24-28 weeks.

He had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MUNICH – Pregestational maternal diabetes is even riskier for newborns than gestational diabetes, increasing the chance of neonatal hypoglycemia by 36 times over a normal pregnancy.

Baby’s blood sugar isn’t the only thing in danger, though, Basilio Pintaudi, MD, said at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes conference. Women with prepregnancy diabetes are significantly more likely to have babies that are either small or large for gestational age; become jaundiced; have congenital malformations; and experience respiratory distress, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, said Dr. Pintaudi of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital, Milan.

“Everyone involved in the care of pregnant women should realize there are very real risks for severe neonatal outcomes, for all forms of diabetes – whether it exists before pregnancy or develops during pregnancy,” Dr. Pintaudi said in an interview. “It’s very important to detect both prepregnancy and gestational diabetes early and optimize maternal glucose levels as quickly as possible.”

He and his colleagues studied outcomes in 135,000 pregnancies included in an administrative database in the Italian Puglia region from 2002 to 2012. They found 1,357 singleton pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes, and 234 by pregestational diabetes. They computed the risks of a number of neonatal outcomes in a multivariate analysis that controlled for hypertensive and thyroid disorders and for several drugs, including antithrombotics, antiplatelets, and ticlopidine. These drugs were chosen as indicators of high-risk pregnancy.

Both gestational and pregestational diabetes were associated with significantly higher risks of neonatal hypoglycemia (odds ratios, 10 and 36, respectively). They were also associated with significantly increased risks of a small for gestational age infant (ORs, 1.7 and 5.8), and large for gestational age infant (ORs, 1.7 and 7.9).

The risk of jaundice was also increased for both gestational and pregestational diabetes (ORs, 1.7 and 2.6).

Fetal malformations were more common in both disorders (ORs, 2.2 and 3.5). The database didn’t include specifics on what type of malformations occurred, but Dr. Pintaudi said prior studies show increases in cardiac and neural tube defects. This problem in particular illustrates the need for early screening and management of pregestational diabetes, he said in an interview.

“The pathophysiology of these malformations is such that they occur in the very early stages of pregnancy, before some women even know they might be pregnant,” he said.

Hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia of the newborn were more likely in both gestational and pregestational diabetes (ORs, 1.8 and 9.2), as was Cesarean delivery (ORs, 1.9 and 8.5).

Pregestational diabetes alone was also associated with an increased risk of respiratory distress (OR, 2.7) and polyhydramnios (OR, 46.5).

Dr. Pintaudi said that Italy does not recommend universal diabetes screening for women who are or wish to become pregnant. The first evaluation occurs at 16-18 weeks’ gestation, with a repeat evaluation at 24-28 weeks.

He had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT EASD 2016

Key clinical point: Pregestational and gestational diabetes increase the risk of a several poor neonatal outcomes.

Major finding: Pregestational diabetes increased the risk of neonatal hypoglycemia by 36 times; gestational diabetes by 10 times.

Data source: The database review comprised 135,000 singleton pregnancies.

Disclosures: Dr. Pintaudi had no financial disclosures.

Meta-analysis suggests earlier twin delivery to prevent stillbirth

Delivery for uncomplicated dichorionic twin pregnancies should be considered at 37 weeks’ gestation, a week earlier than is generally recommended in the United States, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported rates of stillbirth and neonatal mortality at various gestational ages.

The researchers assessed the competing risks in twin pregnancies of stillbirth from expectant management versus neonatal death from early delivery, looking for an optimal gestational age at which these risks were balanced.

In dichorionic pregnancies continuing beyond 34 weeks, these perinatal risks were balanced at 37 weeks. Beyond that, “the risks of stillbirth significantly outweighed the risk of neonatal death from delivery,” with a 1-week delay in delivery (to 38 weeks’ gestation) leading to an additional 8.8 perinatal deaths per 1,000 pregnancies due to an increase in stillbirth, Fiona Cheong-See, MD, of the Queen Mary University of London and her colleagues reported (BMJ 2016;354:i4353. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4353).

The review included 32 studies published in the past 10 years (observational cohort studies and cohorts nested in randomized studies) that reported rates of stillbirth and/or neonatal outcomes, including neonatal mortality, in monochorionic and/or dichorionic twins. Neonatal death was defined as death up to 28 days after delivery.

The study authors shared unpublished aggregate and individual patient data with the meta-analysis researchers, which enabled an analysis at weekly intervals. The data included in the review covered 35,171 women with twin gestations (29,685 dichorionic and 5,486 monochorionic pregnancies).

Pregnancies with unclear chorionicity, monoamnionity, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome were excluded from the analysis.

In monochorionic pregnancies continuing beyond 34 weeks (2,149 pregnancies), there was a trend after 36 weeks toward stillbirth risk being higher than the risk of neonatal death, but the risk difference was not significant.

More data are needed, the researchers said, but “based on our findings, there is no clear evidence to recommend early preterm delivery routinely before 36 weeks in monochorionic pregnancies.”

A committee opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (ACOG-SMFM) on medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries states that decisions regarding the timing of delivery should be individualized and should take into account relative maternal and newborn risks, practice environment, and patient preferences (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:908-10).

Still, the ACOG-SMFM document offers delivery recommendations: 38 0/7-38 6/7 weeks of gestation for dichorionic-diamniotic pregnancies, and 34 0/7-36 6/7 weeks of gestation for monochorionic-diamniotic pregnancies.

The opinion was published in 2013 and reflects recommendations made 2 years earlier by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and SMFM after a workshop on indicated preterm birth (Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:323-33). ACOG and SMFM reaffirmed their document in 2015.

Brigid McCue, MD, chief of ob.gyn. at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital–Plymouth (Mass.) and a member of ACOG’s Committee on Obstetric Practice, said the meta-analysis is of “high quality,” with “helpful and valid” findings for dichorionic twins.

The risk of stillbirth was 1.2/1,000 pregnancies at 34 weeks’ gestation, while the risk of neonatal death from delivery was 6.7/1,000 pregnancies. The risk of stillbirth remained significantly lower than the risk of neonatal death from delivery at 35 weeks, and was lower at 36 weeks as well. At 37 weeks, the two categories of perinatal death risk were basically balanced, with the risk of stillbirth at 3.4/1,000 pregnancies.

Beyond that, at 38 weeks’ gestation, the risk of stillbirth (10.6/1,000) significantly outweighed the risk of neonatal death from delivery (1.5/1,000) for a pooled risk difference of 8.8.

“The finding that stillbirth risk is higher when you allow someone to go from 37 to 38 weeks – I think this is true,” Dr. McCue said in an interview.

Further research needs to account, however, for the risks of neonatal morbidity at 37 and 38 weeks. “The next question in coming up with a point of inflection is to ask, What are other contributors to the balance of timing of the delivery?” Dr. McCue said. “There’s a bigger picture that needs more analysis.”

“We don’t induce singletons prior to 39 weeks because they can have more respiratory distress, more hypoglycemia, more temperature instability, and less success breastfeeding, for example,” she added. “These complications pale in comparison to a stillbirth, but the numbers of stillbirth are so low and the numbers for [these other morbidities] are much higher.”

The authors of the meta-analysis noted that their findings were limited by the common policy of planned delivery beyond 37 and 38 weeks’ gestation. “This reduced the sample size near term, particularly in monochorionic pregnancies, and could have led to underestimation of risk of stillbirth in the last weeks of pregnancy,” they wrote.

The rates of assisted ventilation, respiratory distress syndrome, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, and septicemia showed a consistent reduction with increasing gestational age in babies of both monochorionic and dichorionic pregnancies, the researchers noted.

The researchers reported that they received no funding support from any organization and had no relevant financial disclosures.

Delivery for uncomplicated dichorionic twin pregnancies should be considered at 37 weeks’ gestation, a week earlier than is generally recommended in the United States, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported rates of stillbirth and neonatal mortality at various gestational ages.

The researchers assessed the competing risks in twin pregnancies of stillbirth from expectant management versus neonatal death from early delivery, looking for an optimal gestational age at which these risks were balanced.

In dichorionic pregnancies continuing beyond 34 weeks, these perinatal risks were balanced at 37 weeks. Beyond that, “the risks of stillbirth significantly outweighed the risk of neonatal death from delivery,” with a 1-week delay in delivery (to 38 weeks’ gestation) leading to an additional 8.8 perinatal deaths per 1,000 pregnancies due to an increase in stillbirth, Fiona Cheong-See, MD, of the Queen Mary University of London and her colleagues reported (BMJ 2016;354:i4353. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4353).

The review included 32 studies published in the past 10 years (observational cohort studies and cohorts nested in randomized studies) that reported rates of stillbirth and/or neonatal outcomes, including neonatal mortality, in monochorionic and/or dichorionic twins. Neonatal death was defined as death up to 28 days after delivery.

The study authors shared unpublished aggregate and individual patient data with the meta-analysis researchers, which enabled an analysis at weekly intervals. The data included in the review covered 35,171 women with twin gestations (29,685 dichorionic and 5,486 monochorionic pregnancies).

Pregnancies with unclear chorionicity, monoamnionity, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome were excluded from the analysis.

In monochorionic pregnancies continuing beyond 34 weeks (2,149 pregnancies), there was a trend after 36 weeks toward stillbirth risk being higher than the risk of neonatal death, but the risk difference was not significant.

More data are needed, the researchers said, but “based on our findings, there is no clear evidence to recommend early preterm delivery routinely before 36 weeks in monochorionic pregnancies.”

A committee opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (ACOG-SMFM) on medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries states that decisions regarding the timing of delivery should be individualized and should take into account relative maternal and newborn risks, practice environment, and patient preferences (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:908-10).

Still, the ACOG-SMFM document offers delivery recommendations: 38 0/7-38 6/7 weeks of gestation for dichorionic-diamniotic pregnancies, and 34 0/7-36 6/7 weeks of gestation for monochorionic-diamniotic pregnancies.

The opinion was published in 2013 and reflects recommendations made 2 years earlier by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and SMFM after a workshop on indicated preterm birth (Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:323-33). ACOG and SMFM reaffirmed their document in 2015.

Brigid McCue, MD, chief of ob.gyn. at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital–Plymouth (Mass.) and a member of ACOG’s Committee on Obstetric Practice, said the meta-analysis is of “high quality,” with “helpful and valid” findings for dichorionic twins.

The risk of stillbirth was 1.2/1,000 pregnancies at 34 weeks’ gestation, while the risk of neonatal death from delivery was 6.7/1,000 pregnancies. The risk of stillbirth remained significantly lower than the risk of neonatal death from delivery at 35 weeks, and was lower at 36 weeks as well. At 37 weeks, the two categories of perinatal death risk were basically balanced, with the risk of stillbirth at 3.4/1,000 pregnancies.

Beyond that, at 38 weeks’ gestation, the risk of stillbirth (10.6/1,000) significantly outweighed the risk of neonatal death from delivery (1.5/1,000) for a pooled risk difference of 8.8.

“The finding that stillbirth risk is higher when you allow someone to go from 37 to 38 weeks – I think this is true,” Dr. McCue said in an interview.

Further research needs to account, however, for the risks of neonatal morbidity at 37 and 38 weeks. “The next question in coming up with a point of inflection is to ask, What are other contributors to the balance of timing of the delivery?” Dr. McCue said. “There’s a bigger picture that needs more analysis.”

“We don’t induce singletons prior to 39 weeks because they can have more respiratory distress, more hypoglycemia, more temperature instability, and less success breastfeeding, for example,” she added. “These complications pale in comparison to a stillbirth, but the numbers of stillbirth are so low and the numbers for [these other morbidities] are much higher.”

The authors of the meta-analysis noted that their findings were limited by the common policy of planned delivery beyond 37 and 38 weeks’ gestation. “This reduced the sample size near term, particularly in monochorionic pregnancies, and could have led to underestimation of risk of stillbirth in the last weeks of pregnancy,” they wrote.

The rates of assisted ventilation, respiratory distress syndrome, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, and septicemia showed a consistent reduction with increasing gestational age in babies of both monochorionic and dichorionic pregnancies, the researchers noted.

The researchers reported that they received no funding support from any organization and had no relevant financial disclosures.

Delivery for uncomplicated dichorionic twin pregnancies should be considered at 37 weeks’ gestation, a week earlier than is generally recommended in the United States, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported rates of stillbirth and neonatal mortality at various gestational ages.

The researchers assessed the competing risks in twin pregnancies of stillbirth from expectant management versus neonatal death from early delivery, looking for an optimal gestational age at which these risks were balanced.

In dichorionic pregnancies continuing beyond 34 weeks, these perinatal risks were balanced at 37 weeks. Beyond that, “the risks of stillbirth significantly outweighed the risk of neonatal death from delivery,” with a 1-week delay in delivery (to 38 weeks’ gestation) leading to an additional 8.8 perinatal deaths per 1,000 pregnancies due to an increase in stillbirth, Fiona Cheong-See, MD, of the Queen Mary University of London and her colleagues reported (BMJ 2016;354:i4353. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4353).

The review included 32 studies published in the past 10 years (observational cohort studies and cohorts nested in randomized studies) that reported rates of stillbirth and/or neonatal outcomes, including neonatal mortality, in monochorionic and/or dichorionic twins. Neonatal death was defined as death up to 28 days after delivery.

The study authors shared unpublished aggregate and individual patient data with the meta-analysis researchers, which enabled an analysis at weekly intervals. The data included in the review covered 35,171 women with twin gestations (29,685 dichorionic and 5,486 monochorionic pregnancies).

Pregnancies with unclear chorionicity, monoamnionity, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome were excluded from the analysis.

In monochorionic pregnancies continuing beyond 34 weeks (2,149 pregnancies), there was a trend after 36 weeks toward stillbirth risk being higher than the risk of neonatal death, but the risk difference was not significant.

More data are needed, the researchers said, but “based on our findings, there is no clear evidence to recommend early preterm delivery routinely before 36 weeks in monochorionic pregnancies.”

A committee opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (ACOG-SMFM) on medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries states that decisions regarding the timing of delivery should be individualized and should take into account relative maternal and newborn risks, practice environment, and patient preferences (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:908-10).

Still, the ACOG-SMFM document offers delivery recommendations: 38 0/7-38 6/7 weeks of gestation for dichorionic-diamniotic pregnancies, and 34 0/7-36 6/7 weeks of gestation for monochorionic-diamniotic pregnancies.

The opinion was published in 2013 and reflects recommendations made 2 years earlier by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and SMFM after a workshop on indicated preterm birth (Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:323-33). ACOG and SMFM reaffirmed their document in 2015.

Brigid McCue, MD, chief of ob.gyn. at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital–Plymouth (Mass.) and a member of ACOG’s Committee on Obstetric Practice, said the meta-analysis is of “high quality,” with “helpful and valid” findings for dichorionic twins.

The risk of stillbirth was 1.2/1,000 pregnancies at 34 weeks’ gestation, while the risk of neonatal death from delivery was 6.7/1,000 pregnancies. The risk of stillbirth remained significantly lower than the risk of neonatal death from delivery at 35 weeks, and was lower at 36 weeks as well. At 37 weeks, the two categories of perinatal death risk were basically balanced, with the risk of stillbirth at 3.4/1,000 pregnancies.

Beyond that, at 38 weeks’ gestation, the risk of stillbirth (10.6/1,000) significantly outweighed the risk of neonatal death from delivery (1.5/1,000) for a pooled risk difference of 8.8.

“The finding that stillbirth risk is higher when you allow someone to go from 37 to 38 weeks – I think this is true,” Dr. McCue said in an interview.

Further research needs to account, however, for the risks of neonatal morbidity at 37 and 38 weeks. “The next question in coming up with a point of inflection is to ask, What are other contributors to the balance of timing of the delivery?” Dr. McCue said. “There’s a bigger picture that needs more analysis.”

“We don’t induce singletons prior to 39 weeks because they can have more respiratory distress, more hypoglycemia, more temperature instability, and less success breastfeeding, for example,” she added. “These complications pale in comparison to a stillbirth, but the numbers of stillbirth are so low and the numbers for [these other morbidities] are much higher.”

The authors of the meta-analysis noted that their findings were limited by the common policy of planned delivery beyond 37 and 38 weeks’ gestation. “This reduced the sample size near term, particularly in monochorionic pregnancies, and could have led to underestimation of risk of stillbirth in the last weeks of pregnancy,” they wrote.

The rates of assisted ventilation, respiratory distress syndrome, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, and septicemia showed a consistent reduction with increasing gestational age in babies of both monochorionic and dichorionic pregnancies, the researchers noted.

The researchers reported that they received no funding support from any organization and had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Delivery of uncomplicated dichorionic twin pregnancies at 37 weeks’ gestation could minimize perinatal deaths.

Major finding: A delay in delivery to 38 weeks’ gestation led to an additional 8.8 perinatal deaths per 1,000 pregnancies because of an increase in stillbirth.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 studies.

Disclosures: The researchers reported that they received no funding support from any organization and had no relevant financial disclosures.

Doctors urge Congress to pass Zika funding

Federal health officials, pediatricians, and ob.gyns. are imploring Congress to pass an appropriations bill with sufficient money to fight the growing threat of the Zika virus.

“Funding for Zika research, for prevention, and for control efforts – including mosquito surveillance and control – is essentially all spent,” Beth P. Bell, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said during a press conference. The Obama administration “has already transferred millions of dollars from other important programs to help with the Zika response, [but] without additional resources from Congress, critical public health work may not be accomplished.”

President Obama asked Congress in February to appropriate $1.9 billion to address all aspects of the Zika virus situation in the United States; partisan politics surrounding funding for Planned Parenthood have derailed passage of the legislation to date.

Without additional, specific funding, development of a Zika vaccine would be severely limited, and virtually no funds would be available to conduct multitiered studies that are critical for protecting both women and children from the virus’ devastating effects, Dr. Bell said. Additionally, money allocated to state health departments for the management of patients with Zika virus would no longer be available. Development of tests for early diagnosis would be slowed or halted altogether.

“Allowing this to happen needlessly puts the American people at risk, and will result in more Zika infections and potentially more babies being born with microcephaly and other birth defects,” Dr. Bell added. “Congress has come back from their recess, and we hope that they will do the right thing.”

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “continues to develop, update, and issue guidance on the risks, prevention, assessment, and treatment of the Zika virus,” primarily through its practice advisories and resources available jointly through the CDC, ACOG president Thomas Gellhaus, MD, said.

“The biggest impact Zika has is on babies, and they are our future,” said Karen Remley, MD, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatricians, adding that funding is crucial to continue monitoring children who have been born with birth defects, as the long-term development of these and other issues is new territory for doctors across the United States and its territories.

As Congress prepared to adjourn in advance of the primary elections, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell noted that some progress is being made on Zika funding.

“We’ve made a lot of important progress already,” Sen. McConnell said Sept. 12 on the Senate floor. “I expect to move forward this week on a continuing resolution through Dec. 9 at last year’s enacted levels and include funds for Zika control and our veterans. Talks are continuing, and leaders from both parties will meet later this afternoon at the White House to discuss the progress and path forward.”

Federal health officials, pediatricians, and ob.gyns. are imploring Congress to pass an appropriations bill with sufficient money to fight the growing threat of the Zika virus.

“Funding for Zika research, for prevention, and for control efforts – including mosquito surveillance and control – is essentially all spent,” Beth P. Bell, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said during a press conference. The Obama administration “has already transferred millions of dollars from other important programs to help with the Zika response, [but] without additional resources from Congress, critical public health work may not be accomplished.”

President Obama asked Congress in February to appropriate $1.9 billion to address all aspects of the Zika virus situation in the United States; partisan politics surrounding funding for Planned Parenthood have derailed passage of the legislation to date.

Without additional, specific funding, development of a Zika vaccine would be severely limited, and virtually no funds would be available to conduct multitiered studies that are critical for protecting both women and children from the virus’ devastating effects, Dr. Bell said. Additionally, money allocated to state health departments for the management of patients with Zika virus would no longer be available. Development of tests for early diagnosis would be slowed or halted altogether.

“Allowing this to happen needlessly puts the American people at risk, and will result in more Zika infections and potentially more babies being born with microcephaly and other birth defects,” Dr. Bell added. “Congress has come back from their recess, and we hope that they will do the right thing.”

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “continues to develop, update, and issue guidance on the risks, prevention, assessment, and treatment of the Zika virus,” primarily through its practice advisories and resources available jointly through the CDC, ACOG president Thomas Gellhaus, MD, said.

“The biggest impact Zika has is on babies, and they are our future,” said Karen Remley, MD, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatricians, adding that funding is crucial to continue monitoring children who have been born with birth defects, as the long-term development of these and other issues is new territory for doctors across the United States and its territories.

As Congress prepared to adjourn in advance of the primary elections, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell noted that some progress is being made on Zika funding.

“We’ve made a lot of important progress already,” Sen. McConnell said Sept. 12 on the Senate floor. “I expect to move forward this week on a continuing resolution through Dec. 9 at last year’s enacted levels and include funds for Zika control and our veterans. Talks are continuing, and leaders from both parties will meet later this afternoon at the White House to discuss the progress and path forward.”

Federal health officials, pediatricians, and ob.gyns. are imploring Congress to pass an appropriations bill with sufficient money to fight the growing threat of the Zika virus.

“Funding for Zika research, for prevention, and for control efforts – including mosquito surveillance and control – is essentially all spent,” Beth P. Bell, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said during a press conference. The Obama administration “has already transferred millions of dollars from other important programs to help with the Zika response, [but] without additional resources from Congress, critical public health work may not be accomplished.”

President Obama asked Congress in February to appropriate $1.9 billion to address all aspects of the Zika virus situation in the United States; partisan politics surrounding funding for Planned Parenthood have derailed passage of the legislation to date.

Without additional, specific funding, development of a Zika vaccine would be severely limited, and virtually no funds would be available to conduct multitiered studies that are critical for protecting both women and children from the virus’ devastating effects, Dr. Bell said. Additionally, money allocated to state health departments for the management of patients with Zika virus would no longer be available. Development of tests for early diagnosis would be slowed or halted altogether.

“Allowing this to happen needlessly puts the American people at risk, and will result in more Zika infections and potentially more babies being born with microcephaly and other birth defects,” Dr. Bell added. “Congress has come back from their recess, and we hope that they will do the right thing.”

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “continues to develop, update, and issue guidance on the risks, prevention, assessment, and treatment of the Zika virus,” primarily through its practice advisories and resources available jointly through the CDC, ACOG president Thomas Gellhaus, MD, said.

“The biggest impact Zika has is on babies, and they are our future,” said Karen Remley, MD, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatricians, adding that funding is crucial to continue monitoring children who have been born with birth defects, as the long-term development of these and other issues is new territory for doctors across the United States and its territories.

As Congress prepared to adjourn in advance of the primary elections, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell noted that some progress is being made on Zika funding.

“We’ve made a lot of important progress already,” Sen. McConnell said Sept. 12 on the Senate floor. “I expect to move forward this week on a continuing resolution through Dec. 9 at last year’s enacted levels and include funds for Zika control and our veterans. Talks are continuing, and leaders from both parties will meet later this afternoon at the White House to discuss the progress and path forward.”

Another infant with Zika-related birth defect born in the United States

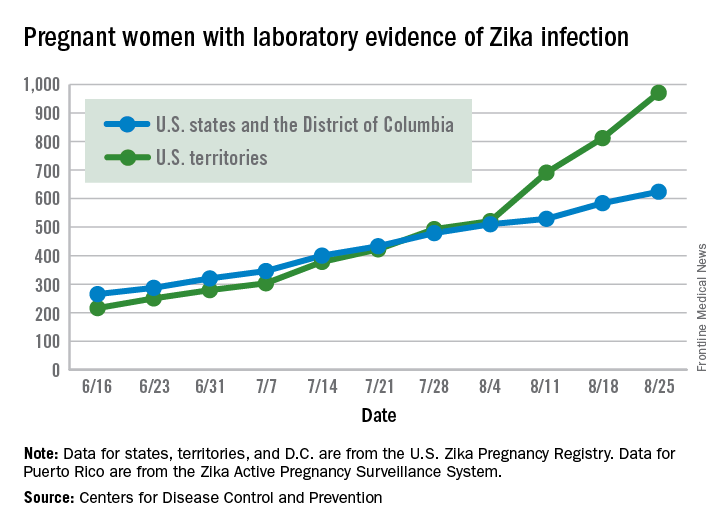

The first new case of a live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects in almost a month was reported during the week ending Sept. 1, bringing the U.S. total to 18 so far, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The infant was born in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and is the first case of a Zika-related birth defect reported since the week ending Aug. 4. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children. There were no new Zika-related pregnancy losses for the week of Sept. 1, so the total remains at six for the states, D.C., and the territories, the CDC reported Sept. 8.

The number of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika infection increased by 156 during the week ending Sept. 1: 47 new cases in the states/D.C. and 109 new cases in the territories. The total number of pregnant women with Zika for 2016 is now 1,751, the CDC said.

For 2015-2016, there have been 18,833 cases reported in the entire U.S. population: 2,964 in the states/D.C. (all but 44 were travel associated) and 15,869 in the territories. All but 60 cases in the territories were locally acquired, and 98% have occurred in Puerto Rico, the CDC also reported Sept. 8.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The first new case of a live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects in almost a month was reported during the week ending Sept. 1, bringing the U.S. total to 18 so far, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The infant was born in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and is the first case of a Zika-related birth defect reported since the week ending Aug. 4. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children. There were no new Zika-related pregnancy losses for the week of Sept. 1, so the total remains at six for the states, D.C., and the territories, the CDC reported Sept. 8.

The number of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika infection increased by 156 during the week ending Sept. 1: 47 new cases in the states/D.C. and 109 new cases in the territories. The total number of pregnant women with Zika for 2016 is now 1,751, the CDC said.

For 2015-2016, there have been 18,833 cases reported in the entire U.S. population: 2,964 in the states/D.C. (all but 44 were travel associated) and 15,869 in the territories. All but 60 cases in the territories were locally acquired, and 98% have occurred in Puerto Rico, the CDC also reported Sept. 8.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The first new case of a live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects in almost a month was reported during the week ending Sept. 1, bringing the U.S. total to 18 so far, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The infant was born in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and is the first case of a Zika-related birth defect reported since the week ending Aug. 4. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children. There were no new Zika-related pregnancy losses for the week of Sept. 1, so the total remains at six for the states, D.C., and the territories, the CDC reported Sept. 8.

The number of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika infection increased by 156 during the week ending Sept. 1: 47 new cases in the states/D.C. and 109 new cases in the territories. The total number of pregnant women with Zika for 2016 is now 1,751, the CDC said.

For 2015-2016, there have been 18,833 cases reported in the entire U.S. population: 2,964 in the states/D.C. (all but 44 were travel associated) and 15,869 in the territories. All but 60 cases in the territories were locally acquired, and 98% have occurred in Puerto Rico, the CDC also reported Sept. 8.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Intrauterine Device Migration

Although intrauterine devices (IUDs) are a mainstay of reversible contraception, they do carry the risk of complications, including septic abortion, abscess formation, ectopic pregnancy, bleeding, and uterine perforation.1 Although perforation is a relatively rare complication, occurring in 0.3 to 2.6 per 1,000 insertions for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems and 0.3 to 2.2 per 1,000 insertions for copper IUDs, it can lead to serious complications, including IUD migration to various sites.2 Most patients with uterine perforation and IUD migration present with abdominal pain and bleeding; however, 30% of patients are asymptomatic.3

This article presents the case of a young woman who was diagnosed with IUD migration into the abdominal cavity. I discuss the management of this uncommon complication, and stress the importance of adequate education for both patients and health care providers regarding proper surveillance.

Case

A 33-year-old woman (gravida 4, para 4, live 4) presented to our ED for evaluation of rectal bleeding that she had experienced intermittently over the past 2 years. She reported that the first occurrence had been 2 years ago, starting a few weeks after she had a cesarean delivery. The patient described the initial episode as bright red blood mixed with stool. She stated that subsequent episodes had been intermittent, felt as if she were “passing rocks” through her abdomen and rectum, and were accompanied by streaks of blood covering her stool. The day before the patient presented to the ED, she had experienced a second episode of a large bowel movement mixed with blood and accompanied by weakness, which prompted her to seek treatment.

A review of the patient’s symptoms revealed abdominal pain and weakness. She denied any bleeding disorders, fever, chills, sick contacts, anal trauma, presyncope, syncope, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation. She further denied any prescription-medication use, illicit drug use, or smoking, but admitted to occasional alcohol use. Her last menstrual period had been 3 weeks prior to presentation. She denied any history of cancer or abnormal Pap smears. Her gynecologic history was significant for chlamydia and trichomoniasis, for which she had been treated. The patient’s surgical history was pertinent for umbilical hernia repair with surgical mesh.

On physical examination, the patient was mildly hypotensive (blood pressure, 97/78 mm Hg) but had a normal heart rate. She had mild conjunctival pallor. The abdominal examination exhibited normoactive bowel sounds with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness to deep palpation, but without rebound, guarding, or distension. Rectal examination revealed a small internal hemorrhoid at the 6 o’clock position (no active bleeding) and an external hemorrhoid with some tenderness to palpation; the external hemorrhoid was not thrombosed, had no signs of infection, and was the same color as the surrounding skin.

A fecal occult blood screen was negative, and a serum pregnancy test was also negative. Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and urinalysis were all unremarkable and within normal ranges. Abdominal X-ray revealed a nonobstructive stool pattern and a foreign body, likely in the abdominal cavity, which appeared to be an IUD (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast were performed to accurately locate the foreign body and to assess for any complications. The CT scans revealed an IUD outside of the uterus, between loops of the transverse colon within the left midabdomen (Figure 2). There were no signs of infection, fluid, or free air. There were also findings of colonic diverticula and narrowed lumen, which were suggestive of diverticulosis.

The patient stated that the IUD had been placed several months after the vaginal birth of her third child. She continued to have normal menstrual periods with the IUD in place. Seven years later, she became pregnant with her fourth child, who was delivered via cesarean, secondary to fetal malpositioning. The IUD was not removed during the cesarean delivery.