User login

Study reinforced value of preconception IBD care

Targeted and regular outpatient care before conception helped prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) during pregnancy, according to a single-center prospective observational study reported in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Women who received such care had about 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant compared with women seen only after conception, said Alison de Lima, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC–University Medical Hospital Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and her associates. “Preconception care seems effective in achieving desirable behavioral modifications in IBD women in terms of folic acid intake, smoking cessation, and correct IBD medication adherence, eventually reducing disease relapse during pregnancy. Most importantly, preconception care positively influences birth outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Several recent studies have reported “incorrect beliefs, unfounded fears, and insufficient knowledge” among women with IBD when it comes to pregnancy, the researchers noted. These beliefs can undermine medication adherence, potentially increasing the risk of complications and poor birth outcomes, they added. Studies have confirmed the value of preconception care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, but none had done so for IBD (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018). Therefore, Dr. de Lima and her associates prospectively followed 317 women seen at the IBD preconception outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral hospital during 2008-2014. A total of 155 patients first visited the clinic before becoming pregnant, while the other 162 patients did so only after conception. New patient visits lasted about 30-45 minutes and included fecal calprotectin testing to assess disease activity, education about the need to avoid conceiving during a disease flare, and general advice about taking folic acid, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. Follow-up visits, which occurred every 3 months before pregnancy and every 2 months thereafter, included clinical assessments of disease activity, maternal serum testing to assess compliance with antitumor necrosis factor and thiopurine therapy, and assessments of folic acid supplementation, smoking, and alcohol use.

Patients who received such care before conceiving tended to be younger (29.7 vs. 31.4 years; P = .001), were more often nulliparous (76% vs. 51%; P = .0001), and had a shorter history of IBD (5.1 vs. 8 years; P = .0001), compared with the postconception care group, the researchers said. However, after researchers controlled for parity, disease duration, and the number of relapses in the year before pregnancy, the preconception care group had a nearly sixfold greater odds of adhering to IBD medications during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.3), about a fivefold greater odds of sufficient folic acid intake (aOR, 5.3; 95% CI, 2.7-10.3), and a more than fourfold odds of smoking cessation during pregnancy (aOR, 4.63; 95% CI, 1.2-17.6). Notably, preconception care was tied to a 49% lower odds of disease relapse during pregnancy (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI; 0.28-0.95) and to a nearly 50% lower rate of low birth weight (birth weight less than 2,500 g).

“To our surprise, this study did not detect an effect of preconception care on periconceptional disease activity,” the researchers said – even though they strove to educate patients on this concept. “We can only speculate about the explanation for this finding, but we believe this could be a result of a discrepancy between physician-declared disease remission and the patient’s own feeling of well-being combined with a strong reproductive desire.”

The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

Targeted and regular outpatient care before conception helped prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) during pregnancy, according to a single-center prospective observational study reported in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Women who received such care had about 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant compared with women seen only after conception, said Alison de Lima, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC–University Medical Hospital Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and her associates. “Preconception care seems effective in achieving desirable behavioral modifications in IBD women in terms of folic acid intake, smoking cessation, and correct IBD medication adherence, eventually reducing disease relapse during pregnancy. Most importantly, preconception care positively influences birth outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Several recent studies have reported “incorrect beliefs, unfounded fears, and insufficient knowledge” among women with IBD when it comes to pregnancy, the researchers noted. These beliefs can undermine medication adherence, potentially increasing the risk of complications and poor birth outcomes, they added. Studies have confirmed the value of preconception care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, but none had done so for IBD (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018). Therefore, Dr. de Lima and her associates prospectively followed 317 women seen at the IBD preconception outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral hospital during 2008-2014. A total of 155 patients first visited the clinic before becoming pregnant, while the other 162 patients did so only after conception. New patient visits lasted about 30-45 minutes and included fecal calprotectin testing to assess disease activity, education about the need to avoid conceiving during a disease flare, and general advice about taking folic acid, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. Follow-up visits, which occurred every 3 months before pregnancy and every 2 months thereafter, included clinical assessments of disease activity, maternal serum testing to assess compliance with antitumor necrosis factor and thiopurine therapy, and assessments of folic acid supplementation, smoking, and alcohol use.

Patients who received such care before conceiving tended to be younger (29.7 vs. 31.4 years; P = .001), were more often nulliparous (76% vs. 51%; P = .0001), and had a shorter history of IBD (5.1 vs. 8 years; P = .0001), compared with the postconception care group, the researchers said. However, after researchers controlled for parity, disease duration, and the number of relapses in the year before pregnancy, the preconception care group had a nearly sixfold greater odds of adhering to IBD medications during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.3), about a fivefold greater odds of sufficient folic acid intake (aOR, 5.3; 95% CI, 2.7-10.3), and a more than fourfold odds of smoking cessation during pregnancy (aOR, 4.63; 95% CI, 1.2-17.6). Notably, preconception care was tied to a 49% lower odds of disease relapse during pregnancy (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI; 0.28-0.95) and to a nearly 50% lower rate of low birth weight (birth weight less than 2,500 g).

“To our surprise, this study did not detect an effect of preconception care on periconceptional disease activity,” the researchers said – even though they strove to educate patients on this concept. “We can only speculate about the explanation for this finding, but we believe this could be a result of a discrepancy between physician-declared disease remission and the patient’s own feeling of well-being combined with a strong reproductive desire.”

The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

Targeted and regular outpatient care before conception helped prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) during pregnancy, according to a single-center prospective observational study reported in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Women who received such care had about 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant compared with women seen only after conception, said Alison de Lima, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC–University Medical Hospital Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and her associates. “Preconception care seems effective in achieving desirable behavioral modifications in IBD women in terms of folic acid intake, smoking cessation, and correct IBD medication adherence, eventually reducing disease relapse during pregnancy. Most importantly, preconception care positively influences birth outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Several recent studies have reported “incorrect beliefs, unfounded fears, and insufficient knowledge” among women with IBD when it comes to pregnancy, the researchers noted. These beliefs can undermine medication adherence, potentially increasing the risk of complications and poor birth outcomes, they added. Studies have confirmed the value of preconception care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, but none had done so for IBD (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018). Therefore, Dr. de Lima and her associates prospectively followed 317 women seen at the IBD preconception outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral hospital during 2008-2014. A total of 155 patients first visited the clinic before becoming pregnant, while the other 162 patients did so only after conception. New patient visits lasted about 30-45 minutes and included fecal calprotectin testing to assess disease activity, education about the need to avoid conceiving during a disease flare, and general advice about taking folic acid, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol during pregnancy. Follow-up visits, which occurred every 3 months before pregnancy and every 2 months thereafter, included clinical assessments of disease activity, maternal serum testing to assess compliance with antitumor necrosis factor and thiopurine therapy, and assessments of folic acid supplementation, smoking, and alcohol use.

Patients who received such care before conceiving tended to be younger (29.7 vs. 31.4 years; P = .001), were more often nulliparous (76% vs. 51%; P = .0001), and had a shorter history of IBD (5.1 vs. 8 years; P = .0001), compared with the postconception care group, the researchers said. However, after researchers controlled for parity, disease duration, and the number of relapses in the year before pregnancy, the preconception care group had a nearly sixfold greater odds of adhering to IBD medications during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.3), about a fivefold greater odds of sufficient folic acid intake (aOR, 5.3; 95% CI, 2.7-10.3), and a more than fourfold odds of smoking cessation during pregnancy (aOR, 4.63; 95% CI, 1.2-17.6). Notably, preconception care was tied to a 49% lower odds of disease relapse during pregnancy (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI; 0.28-0.95) and to a nearly 50% lower rate of low birth weight (birth weight less than 2,500 g).

“To our surprise, this study did not detect an effect of preconception care on periconceptional disease activity,” the researchers said – even though they strove to educate patients on this concept. “We can only speculate about the explanation for this finding, but we believe this could be a result of a discrepancy between physician-declared disease remission and the patient’s own feeling of well-being combined with a strong reproductive desire.”

The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Preconception care with intensive follow-up seems to help prevent relapse of IBD during pregnancy.

Major finding: Women who were seen and followed before pregnancy had about a 50% lower odds of relapse while pregnant than did women who did not seek care until after becoming pregnant.

Data source: A single-center prospective observational study of 317 women with IBD seen at a university outpatient clinic.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no funding sources, and Dr. de Lima had no disclosures. Two coinvestigators reported ties to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, Shire, and Ferring.

Woman, 36, With Fever and Malaise

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clinical presentation and evaluation

- Terminology table

- Outcome for the case patient

A 36-year-old Bengali woman with a history of well-controlled diabetes presents to the emergency department with complaints of feeling “unwell” for about two weeks. She does not speak English, and a hospital-provided phone translator is used to obtain history and explain hospital course. The patient is vague regarding symptomatology, describing general malaise and tiredness. She says she became “much worse” two days ago and has shaking chills, sore throat, headache, and nonproductive cough, but she denies shortness of breath or chest pain. She also developed nausea and vomiting, stating, “I can’t keep anything down.”

She has not recently traveled out of the country and has no known sick contacts. Influenza activity is high in the area, and the patient has not received immunization. She had a “normal” menstrual period two weeks ago and firmly states, “There is no way I can be pregnant.” She admits to vaginal “spotting” off and on for the past two weeks without abdominal pain. She is married with six children and has no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion; she is not taking any form of birth control.

On exam, the patient is tachycardic, with a heart rate of 127 beats/min, and has a fever of 103.3°F. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry are normal. She appears unwell and dehydrated. Her mucous membranes are dry, but no skin rash is noted. There is no tonsillar swelling or exudate and no meningismus; the lung exam is clear, with no adventitious sounds. Abdominal exam demonstrates mild, generalized tenderness in the lower abdomen without peritoneal signs. No costovertebral angle tenderness is noted. Initial diagnostic considerations include sources of fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, viral illness), or abdominal sources, such as appendicitis.

An upright anteroposterior chest x-ray shows no infiltrate, pleural effusion, or cardiomegaly. Laboratory results include a high white blood cell (WBC) count (16.9 k/mm3) with bandemia and normal electrolytes without anion gap. Rapid influenza A and B testing is negative. A urine pregnancy test is positive, and the urinalysis shows no infection but +2 ketones. Rh factor is positive. A serum quantitative β-hCG is 130,581 mIU/mL. Blood cultures are obtained, but results are not available.

Due to cultural differences, the patient is very reluctant to consent to a pelvic exam. After extensive counseling, she agrees to a bimanual exam only. The uterus is boggy and enlarged to about 12 weeks. There is exquisite uterine tenderness and purulent discharge on the gloved finger. The cervical os is closed, and there is scant bleeding.

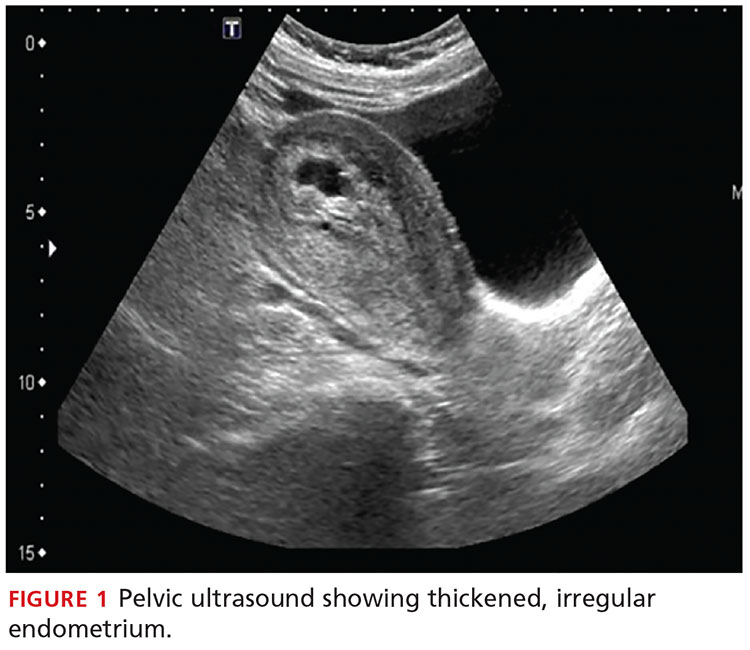

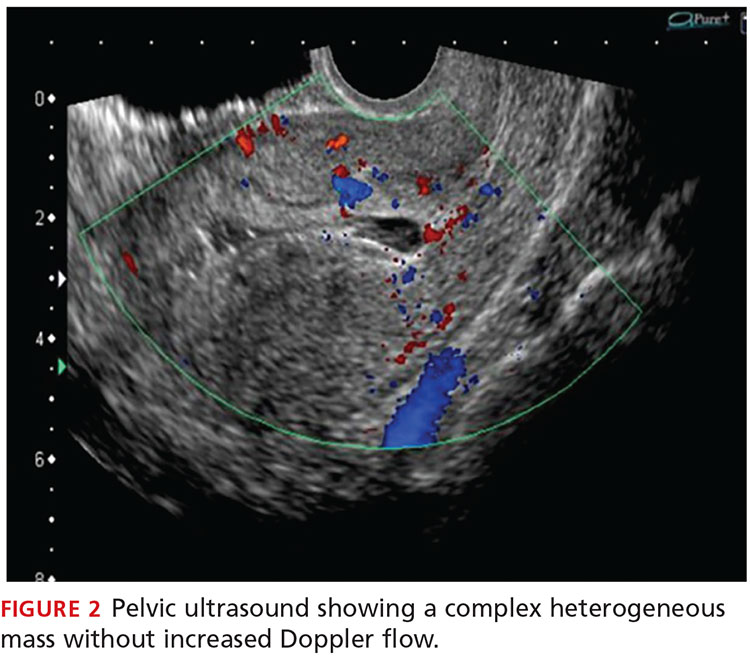

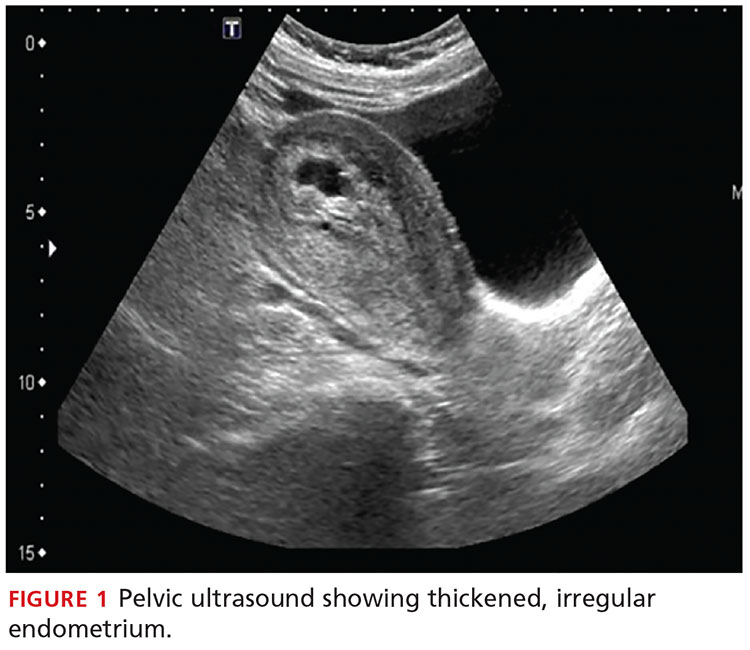

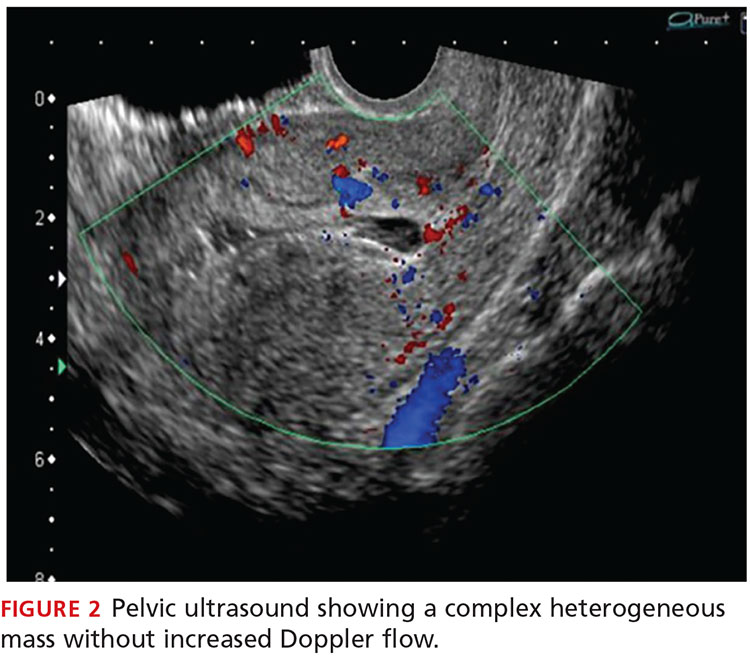

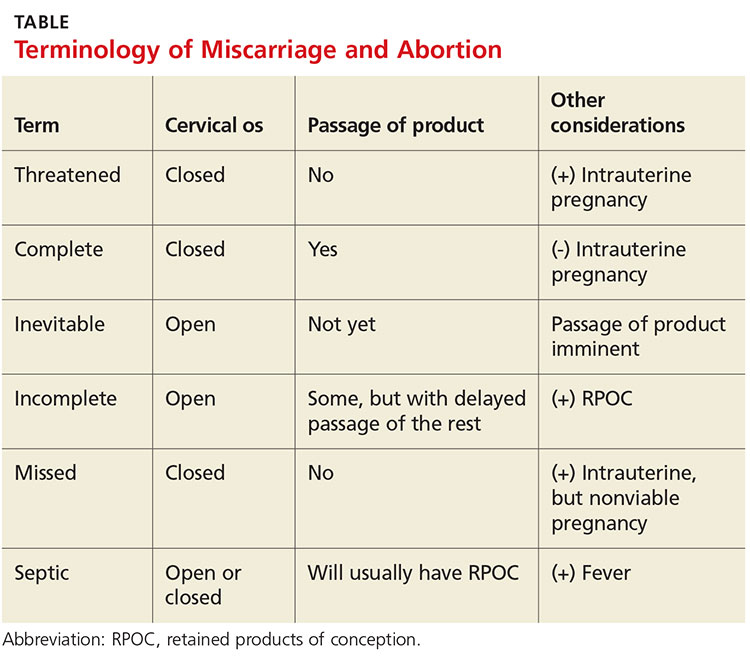

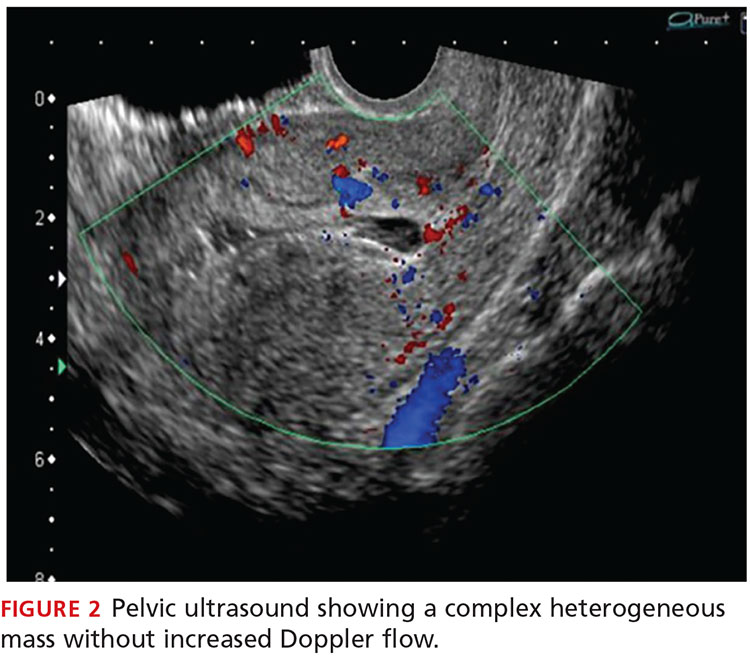

A transvaginal ultrasound is obtained; it reveals a thickened endometrium with echogenicity, without increased vascularity, and no identifiable intrauterine pregnancy. The adnexa have no masses, and there is no free fluid in the endometrium (see Figures 1 and 2).

The patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgently transported to the operating room by Ob-Gyn for uterine evacuation. She is found to have a septic abortion due to retained products of conception (RPOC) from an incomplete miscarriage.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSIONIt is not uncommon for a woman to miscarry a very early pregnancy and not realize she had been pregnant.1 Many attribute it to a “heavy” or unusual period. In one study, 11% of patients who denied the possibility of pregnancy were, in fact, pregnant.2

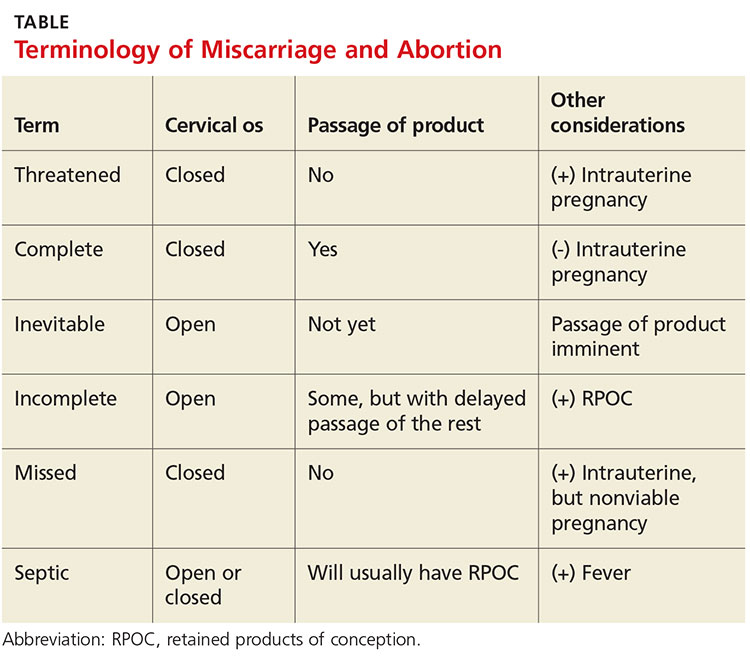

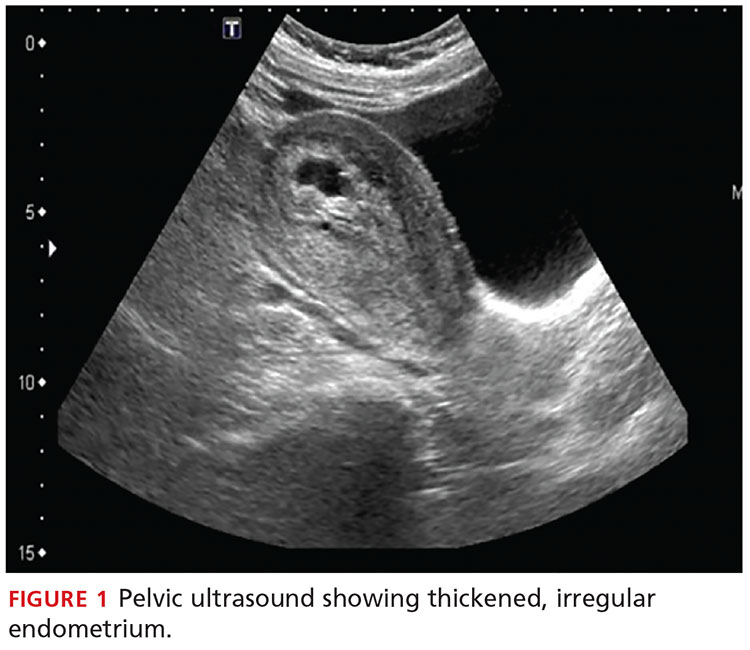

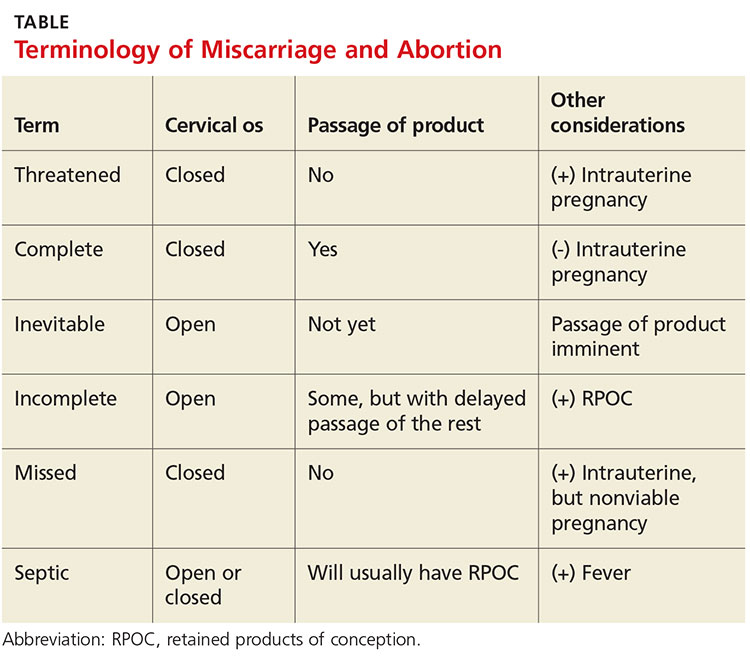

Miscarriage is a frequent outcome of early pregnancy; it is estimated that 11% to 20% of early pregnancies result in a spontaneous miscarriage.3-5 Most resolve without complications, but risk increases with gestational age. When they do occur, complications include RPOC, heavy prolonged bleeding, and endometritis. RPOC refers to placental or fetal tissue that remains in the uterus after a miscarriage, surgical abortion, or preterm/term delivery (see Table for additional terminology related to miscarriage and abortion). Because of increased morbidity, it is important to suspect RPOC after a known miscarriage or an induced abortion, or in a pregnant patient with bleeding.

Incidence and pathophysiologySeptic abortion is a relatively rare complication of miscarriage. It can refer to a spontaneous miscarriage complicated by a subsequent intrauterine infection, often caused by RPOC. Septic abortion is much more common after an induced abortion, in which there is instrumentation of the uterus.

The infection after a spontaneous miscarriage usually begins as endometritis. It involves the necrotic RPOC, which are prone to infection by the cervical and vaginal flora. It may spread further into the parametrium/myometrium and the peritoneal cavity. The infection may then progress to bacteremia and sepsis. Typical causative organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus vulgaris, hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and some anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium perfringens.3

Death, although rare in developed countries, is usually secondary to the sequela of sepsis, including septic shock, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,6,7 Pelvic adhesions and hysterectomy are also possible outcomes of a septic abortion.

Continue for clinical presentation and evaluation >>

Clinical presentation and evaluationMany findings suggestive of septic abortion are nonspecific, such as bleeding, pain, uterine tenderness, and fever. A combination of historical risk, physical exam, and laboratory and ultrasound findings will often be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Fever is never to be expected in an uncomplicated miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding and some cramping are common after miscarriage; women will bleed, on average, between eight and 11 days afterward.5 Women who fall outside the normal range and experience prolonged bleeding, heavy bleeding, or severe abdominal pain should be evaluated.

A workup for patients with a possible septic abortion should include a complete blood count, blood culture with additional laboratory investigation if there is concern for bacteremia/sepsis, and type and screen for Rh factor and for possible blood transfusion, if needed.

All patients with postabortion complications should be screened for Rh factor; Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) should be administered if results indicate that the patient is Rh-negative and unsensitized. A quantitative β-hCG level can be obtained to confirm pregnancy. A single measurement will not be helpful; β-hCG can remain positive for weeks after an uncomplicated miscarriage. On the other hand, a low level does not exclude RPOC—the RPOC, if necrotic, may remain in the uterus without secreting hormone. The trend of β-hCG over time can be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear.

A careful physical exam, including a pelvic exam, should be performed. Assess for uterine tenderness, peritoneal signs, and purulent discharge from the cervix. An open cervical os is suggestive of RPOC, as the cervix closes quickly after a complete miscarriage, but a closed cervical os does not exclude the possibility of RPOC or septic abortion. The amount of bleeding should be noted, along with any tissue or clots within the vaginal vault or cervix.

A pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in all patients concerning for a septic incomplete miscarriage. Ultrasound findings can be nonspecific, because small amounts of retained tissue can look like blood (a common finding after miscarriage). Ultrasound findings of heterogeneous, echogenic material within the uterus or a thick, irregular endometrium support a diagnosis of RPOC in patients considered at risk.8,9 Increased color Doppler flow is often seen with RPOC, but there may be decreased flow in the case of necrotic RPOC. Ultrasound findings consistent with RPOC in a febrile, ill patient suggest a septic abortion.

Continue for treatment and prognosis >>

Treatment and prognosisPatients with a septic abortion require immediate evacuation of the uterus to prevent deadly complications; antibiotics may not be able to perfuse to the necrotic source of infection.10 Suction curettage is less likely than sharp curettage to cause perforation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The bacteria associated with a septic incomplete miscarriage are usually polymicrobial and represent the normal flora of the vagina and cervix. The choice of agents recommended is usually the same as for pelvic inflammatory disease.11

The treatment regimen typically includes clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h), plus gentamicin (5 mg/kg IV once a day), with or without ampicillin (2 g IV q4h).11,12 Alternatively, a combination of ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole (500 mg IV q8h) can be used.

Further surgery, including laparotomy and possible hysterectomy, is indicated in patients who do not respond to uterine evacuation and parenteral antibiotics. Other possible complications requiring surgery include pelvic abscess, necrotizing Clostridium infections in the myometrium, and uterine perforation.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENTThe patient was started on IV ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin and taken promptly for a suction dilation and curettage. Pathology later showed a gestational sac with severe acute necrotizing chorioamnionitis and extensive bacterial growth. This confirmed the diagnosis of a septic, incomplete miscarriage.

Blood cultures remained without any growth, and the patient was afebrile on the second postop day. The WBC count and β-hCG level trended downward.

The patient was discharged on a 14-day course of oral doxycycline and metronidazole. She was then lost to further follow-up.

CONCLUSIONThe differential diagnosis in this ill, febrile patient was initially very broad. The importance of suspecting pregnancy in all women of childbearing age, especially those not using contraception, cannot be underestimated. The accuracy of patient history and recall of last menstrual period in determining the possibility of pregnancy is not sufficiently reliable.

1. Promislow JH, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, et al. Bleeding following pregnancy loss prior to six weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):853-857.

2. Ramoska EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):48-50.

3. Osazuwa H, Aziken M. Septic abortion: a review of social and demographic characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):117-119.

4. Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, et al. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37109.

5. Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):84-86.

6. Eschenbach DA. Treating spontaneous and induced septic abortions. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1042-1048.

7. Rana A, Pradhan N, Gurung G, Singh M. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):3-8.

8. Abbasi S, Jamal A, Eslamian L, Marsousi V. Role of clinical and ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):704-707.

9. Esmaeillou H, Jamal A, Eslamian L, et al. Accurate detection of retained products of conception after first- and second-trimester abortion by color doppler sonography. J Med Ultrasound. 2015;23(7):34-38.

10. Finkielman JD, De Feo FD, Heller PG, Afessa B. The clinical course of patients with septic abortion admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1097-1102.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

12. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD001067.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clinical presentation and evaluation

- Terminology table

- Outcome for the case patient

A 36-year-old Bengali woman with a history of well-controlled diabetes presents to the emergency department with complaints of feeling “unwell” for about two weeks. She does not speak English, and a hospital-provided phone translator is used to obtain history and explain hospital course. The patient is vague regarding symptomatology, describing general malaise and tiredness. She says she became “much worse” two days ago and has shaking chills, sore throat, headache, and nonproductive cough, but she denies shortness of breath or chest pain. She also developed nausea and vomiting, stating, “I can’t keep anything down.”

She has not recently traveled out of the country and has no known sick contacts. Influenza activity is high in the area, and the patient has not received immunization. She had a “normal” menstrual period two weeks ago and firmly states, “There is no way I can be pregnant.” She admits to vaginal “spotting” off and on for the past two weeks without abdominal pain. She is married with six children and has no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion; she is not taking any form of birth control.

On exam, the patient is tachycardic, with a heart rate of 127 beats/min, and has a fever of 103.3°F. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry are normal. She appears unwell and dehydrated. Her mucous membranes are dry, but no skin rash is noted. There is no tonsillar swelling or exudate and no meningismus; the lung exam is clear, with no adventitious sounds. Abdominal exam demonstrates mild, generalized tenderness in the lower abdomen without peritoneal signs. No costovertebral angle tenderness is noted. Initial diagnostic considerations include sources of fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, viral illness), or abdominal sources, such as appendicitis.

An upright anteroposterior chest x-ray shows no infiltrate, pleural effusion, or cardiomegaly. Laboratory results include a high white blood cell (WBC) count (16.9 k/mm3) with bandemia and normal electrolytes without anion gap. Rapid influenza A and B testing is negative. A urine pregnancy test is positive, and the urinalysis shows no infection but +2 ketones. Rh factor is positive. A serum quantitative β-hCG is 130,581 mIU/mL. Blood cultures are obtained, but results are not available.

Due to cultural differences, the patient is very reluctant to consent to a pelvic exam. After extensive counseling, she agrees to a bimanual exam only. The uterus is boggy and enlarged to about 12 weeks. There is exquisite uterine tenderness and purulent discharge on the gloved finger. The cervical os is closed, and there is scant bleeding.

A transvaginal ultrasound is obtained; it reveals a thickened endometrium with echogenicity, without increased vascularity, and no identifiable intrauterine pregnancy. The adnexa have no masses, and there is no free fluid in the endometrium (see Figures 1 and 2).

The patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgently transported to the operating room by Ob-Gyn for uterine evacuation. She is found to have a septic abortion due to retained products of conception (RPOC) from an incomplete miscarriage.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSIONIt is not uncommon for a woman to miscarry a very early pregnancy and not realize she had been pregnant.1 Many attribute it to a “heavy” or unusual period. In one study, 11% of patients who denied the possibility of pregnancy were, in fact, pregnant.2

Miscarriage is a frequent outcome of early pregnancy; it is estimated that 11% to 20% of early pregnancies result in a spontaneous miscarriage.3-5 Most resolve without complications, but risk increases with gestational age. When they do occur, complications include RPOC, heavy prolonged bleeding, and endometritis. RPOC refers to placental or fetal tissue that remains in the uterus after a miscarriage, surgical abortion, or preterm/term delivery (see Table for additional terminology related to miscarriage and abortion). Because of increased morbidity, it is important to suspect RPOC after a known miscarriage or an induced abortion, or in a pregnant patient with bleeding.

Incidence and pathophysiologySeptic abortion is a relatively rare complication of miscarriage. It can refer to a spontaneous miscarriage complicated by a subsequent intrauterine infection, often caused by RPOC. Septic abortion is much more common after an induced abortion, in which there is instrumentation of the uterus.

The infection after a spontaneous miscarriage usually begins as endometritis. It involves the necrotic RPOC, which are prone to infection by the cervical and vaginal flora. It may spread further into the parametrium/myometrium and the peritoneal cavity. The infection may then progress to bacteremia and sepsis. Typical causative organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus vulgaris, hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and some anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium perfringens.3

Death, although rare in developed countries, is usually secondary to the sequela of sepsis, including septic shock, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,6,7 Pelvic adhesions and hysterectomy are also possible outcomes of a septic abortion.

Continue for clinical presentation and evaluation >>

Clinical presentation and evaluationMany findings suggestive of septic abortion are nonspecific, such as bleeding, pain, uterine tenderness, and fever. A combination of historical risk, physical exam, and laboratory and ultrasound findings will often be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Fever is never to be expected in an uncomplicated miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding and some cramping are common after miscarriage; women will bleed, on average, between eight and 11 days afterward.5 Women who fall outside the normal range and experience prolonged bleeding, heavy bleeding, or severe abdominal pain should be evaluated.

A workup for patients with a possible septic abortion should include a complete blood count, blood culture with additional laboratory investigation if there is concern for bacteremia/sepsis, and type and screen for Rh factor and for possible blood transfusion, if needed.

All patients with postabortion complications should be screened for Rh factor; Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) should be administered if results indicate that the patient is Rh-negative and unsensitized. A quantitative β-hCG level can be obtained to confirm pregnancy. A single measurement will not be helpful; β-hCG can remain positive for weeks after an uncomplicated miscarriage. On the other hand, a low level does not exclude RPOC—the RPOC, if necrotic, may remain in the uterus without secreting hormone. The trend of β-hCG over time can be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear.

A careful physical exam, including a pelvic exam, should be performed. Assess for uterine tenderness, peritoneal signs, and purulent discharge from the cervix. An open cervical os is suggestive of RPOC, as the cervix closes quickly after a complete miscarriage, but a closed cervical os does not exclude the possibility of RPOC or septic abortion. The amount of bleeding should be noted, along with any tissue or clots within the vaginal vault or cervix.

A pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in all patients concerning for a septic incomplete miscarriage. Ultrasound findings can be nonspecific, because small amounts of retained tissue can look like blood (a common finding after miscarriage). Ultrasound findings of heterogeneous, echogenic material within the uterus or a thick, irregular endometrium support a diagnosis of RPOC in patients considered at risk.8,9 Increased color Doppler flow is often seen with RPOC, but there may be decreased flow in the case of necrotic RPOC. Ultrasound findings consistent with RPOC in a febrile, ill patient suggest a septic abortion.

Continue for treatment and prognosis >>

Treatment and prognosisPatients with a septic abortion require immediate evacuation of the uterus to prevent deadly complications; antibiotics may not be able to perfuse to the necrotic source of infection.10 Suction curettage is less likely than sharp curettage to cause perforation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The bacteria associated with a septic incomplete miscarriage are usually polymicrobial and represent the normal flora of the vagina and cervix. The choice of agents recommended is usually the same as for pelvic inflammatory disease.11

The treatment regimen typically includes clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h), plus gentamicin (5 mg/kg IV once a day), with or without ampicillin (2 g IV q4h).11,12 Alternatively, a combination of ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole (500 mg IV q8h) can be used.

Further surgery, including laparotomy and possible hysterectomy, is indicated in patients who do not respond to uterine evacuation and parenteral antibiotics. Other possible complications requiring surgery include pelvic abscess, necrotizing Clostridium infections in the myometrium, and uterine perforation.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENTThe patient was started on IV ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin and taken promptly for a suction dilation and curettage. Pathology later showed a gestational sac with severe acute necrotizing chorioamnionitis and extensive bacterial growth. This confirmed the diagnosis of a septic, incomplete miscarriage.

Blood cultures remained without any growth, and the patient was afebrile on the second postop day. The WBC count and β-hCG level trended downward.

The patient was discharged on a 14-day course of oral doxycycline and metronidazole. She was then lost to further follow-up.

CONCLUSIONThe differential diagnosis in this ill, febrile patient was initially very broad. The importance of suspecting pregnancy in all women of childbearing age, especially those not using contraception, cannot be underestimated. The accuracy of patient history and recall of last menstrual period in determining the possibility of pregnancy is not sufficiently reliable.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clinical presentation and evaluation

- Terminology table

- Outcome for the case patient

A 36-year-old Bengali woman with a history of well-controlled diabetes presents to the emergency department with complaints of feeling “unwell” for about two weeks. She does not speak English, and a hospital-provided phone translator is used to obtain history and explain hospital course. The patient is vague regarding symptomatology, describing general malaise and tiredness. She says she became “much worse” two days ago and has shaking chills, sore throat, headache, and nonproductive cough, but she denies shortness of breath or chest pain. She also developed nausea and vomiting, stating, “I can’t keep anything down.”

She has not recently traveled out of the country and has no known sick contacts. Influenza activity is high in the area, and the patient has not received immunization. She had a “normal” menstrual period two weeks ago and firmly states, “There is no way I can be pregnant.” She admits to vaginal “spotting” off and on for the past two weeks without abdominal pain. She is married with six children and has no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion; she is not taking any form of birth control.

On exam, the patient is tachycardic, with a heart rate of 127 beats/min, and has a fever of 103.3°F. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry are normal. She appears unwell and dehydrated. Her mucous membranes are dry, but no skin rash is noted. There is no tonsillar swelling or exudate and no meningismus; the lung exam is clear, with no adventitious sounds. Abdominal exam demonstrates mild, generalized tenderness in the lower abdomen without peritoneal signs. No costovertebral angle tenderness is noted. Initial diagnostic considerations include sources of fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, viral illness), or abdominal sources, such as appendicitis.

An upright anteroposterior chest x-ray shows no infiltrate, pleural effusion, or cardiomegaly. Laboratory results include a high white blood cell (WBC) count (16.9 k/mm3) with bandemia and normal electrolytes without anion gap. Rapid influenza A and B testing is negative. A urine pregnancy test is positive, and the urinalysis shows no infection but +2 ketones. Rh factor is positive. A serum quantitative β-hCG is 130,581 mIU/mL. Blood cultures are obtained, but results are not available.

Due to cultural differences, the patient is very reluctant to consent to a pelvic exam. After extensive counseling, she agrees to a bimanual exam only. The uterus is boggy and enlarged to about 12 weeks. There is exquisite uterine tenderness and purulent discharge on the gloved finger. The cervical os is closed, and there is scant bleeding.

A transvaginal ultrasound is obtained; it reveals a thickened endometrium with echogenicity, without increased vascularity, and no identifiable intrauterine pregnancy. The adnexa have no masses, and there is no free fluid in the endometrium (see Figures 1 and 2).

The patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgently transported to the operating room by Ob-Gyn for uterine evacuation. She is found to have a septic abortion due to retained products of conception (RPOC) from an incomplete miscarriage.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSIONIt is not uncommon for a woman to miscarry a very early pregnancy and not realize she had been pregnant.1 Many attribute it to a “heavy” or unusual period. In one study, 11% of patients who denied the possibility of pregnancy were, in fact, pregnant.2

Miscarriage is a frequent outcome of early pregnancy; it is estimated that 11% to 20% of early pregnancies result in a spontaneous miscarriage.3-5 Most resolve without complications, but risk increases with gestational age. When they do occur, complications include RPOC, heavy prolonged bleeding, and endometritis. RPOC refers to placental or fetal tissue that remains in the uterus after a miscarriage, surgical abortion, or preterm/term delivery (see Table for additional terminology related to miscarriage and abortion). Because of increased morbidity, it is important to suspect RPOC after a known miscarriage or an induced abortion, or in a pregnant patient with bleeding.

Incidence and pathophysiologySeptic abortion is a relatively rare complication of miscarriage. It can refer to a spontaneous miscarriage complicated by a subsequent intrauterine infection, often caused by RPOC. Septic abortion is much more common after an induced abortion, in which there is instrumentation of the uterus.

The infection after a spontaneous miscarriage usually begins as endometritis. It involves the necrotic RPOC, which are prone to infection by the cervical and vaginal flora. It may spread further into the parametrium/myometrium and the peritoneal cavity. The infection may then progress to bacteremia and sepsis. Typical causative organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus vulgaris, hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and some anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium perfringens.3

Death, although rare in developed countries, is usually secondary to the sequela of sepsis, including septic shock, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,6,7 Pelvic adhesions and hysterectomy are also possible outcomes of a septic abortion.

Continue for clinical presentation and evaluation >>

Clinical presentation and evaluationMany findings suggestive of septic abortion are nonspecific, such as bleeding, pain, uterine tenderness, and fever. A combination of historical risk, physical exam, and laboratory and ultrasound findings will often be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Fever is never to be expected in an uncomplicated miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding and some cramping are common after miscarriage; women will bleed, on average, between eight and 11 days afterward.5 Women who fall outside the normal range and experience prolonged bleeding, heavy bleeding, or severe abdominal pain should be evaluated.

A workup for patients with a possible septic abortion should include a complete blood count, blood culture with additional laboratory investigation if there is concern for bacteremia/sepsis, and type and screen for Rh factor and for possible blood transfusion, if needed.

All patients with postabortion complications should be screened for Rh factor; Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) should be administered if results indicate that the patient is Rh-negative and unsensitized. A quantitative β-hCG level can be obtained to confirm pregnancy. A single measurement will not be helpful; β-hCG can remain positive for weeks after an uncomplicated miscarriage. On the other hand, a low level does not exclude RPOC—the RPOC, if necrotic, may remain in the uterus without secreting hormone. The trend of β-hCG over time can be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear.

A careful physical exam, including a pelvic exam, should be performed. Assess for uterine tenderness, peritoneal signs, and purulent discharge from the cervix. An open cervical os is suggestive of RPOC, as the cervix closes quickly after a complete miscarriage, but a closed cervical os does not exclude the possibility of RPOC or septic abortion. The amount of bleeding should be noted, along with any tissue or clots within the vaginal vault or cervix.

A pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in all patients concerning for a septic incomplete miscarriage. Ultrasound findings can be nonspecific, because small amounts of retained tissue can look like blood (a common finding after miscarriage). Ultrasound findings of heterogeneous, echogenic material within the uterus or a thick, irregular endometrium support a diagnosis of RPOC in patients considered at risk.8,9 Increased color Doppler flow is often seen with RPOC, but there may be decreased flow in the case of necrotic RPOC. Ultrasound findings consistent with RPOC in a febrile, ill patient suggest a septic abortion.

Continue for treatment and prognosis >>

Treatment and prognosisPatients with a septic abortion require immediate evacuation of the uterus to prevent deadly complications; antibiotics may not be able to perfuse to the necrotic source of infection.10 Suction curettage is less likely than sharp curettage to cause perforation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The bacteria associated with a septic incomplete miscarriage are usually polymicrobial and represent the normal flora of the vagina and cervix. The choice of agents recommended is usually the same as for pelvic inflammatory disease.11

The treatment regimen typically includes clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h), plus gentamicin (5 mg/kg IV once a day), with or without ampicillin (2 g IV q4h).11,12 Alternatively, a combination of ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole (500 mg IV q8h) can be used.

Further surgery, including laparotomy and possible hysterectomy, is indicated in patients who do not respond to uterine evacuation and parenteral antibiotics. Other possible complications requiring surgery include pelvic abscess, necrotizing Clostridium infections in the myometrium, and uterine perforation.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENTThe patient was started on IV ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin and taken promptly for a suction dilation and curettage. Pathology later showed a gestational sac with severe acute necrotizing chorioamnionitis and extensive bacterial growth. This confirmed the diagnosis of a septic, incomplete miscarriage.

Blood cultures remained without any growth, and the patient was afebrile on the second postop day. The WBC count and β-hCG level trended downward.

The patient was discharged on a 14-day course of oral doxycycline and metronidazole. She was then lost to further follow-up.

CONCLUSIONThe differential diagnosis in this ill, febrile patient was initially very broad. The importance of suspecting pregnancy in all women of childbearing age, especially those not using contraception, cannot be underestimated. The accuracy of patient history and recall of last menstrual period in determining the possibility of pregnancy is not sufficiently reliable.

1. Promislow JH, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, et al. Bleeding following pregnancy loss prior to six weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):853-857.

2. Ramoska EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):48-50.

3. Osazuwa H, Aziken M. Septic abortion: a review of social and demographic characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):117-119.

4. Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, et al. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37109.

5. Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):84-86.

6. Eschenbach DA. Treating spontaneous and induced septic abortions. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1042-1048.

7. Rana A, Pradhan N, Gurung G, Singh M. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):3-8.

8. Abbasi S, Jamal A, Eslamian L, Marsousi V. Role of clinical and ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):704-707.

9. Esmaeillou H, Jamal A, Eslamian L, et al. Accurate detection of retained products of conception after first- and second-trimester abortion by color doppler sonography. J Med Ultrasound. 2015;23(7):34-38.

10. Finkielman JD, De Feo FD, Heller PG, Afessa B. The clinical course of patients with septic abortion admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1097-1102.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

12. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD001067.

1. Promislow JH, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, et al. Bleeding following pregnancy loss prior to six weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):853-857.

2. Ramoska EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):48-50.

3. Osazuwa H, Aziken M. Septic abortion: a review of social and demographic characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):117-119.

4. Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, et al. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37109.

5. Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):84-86.

6. Eschenbach DA. Treating spontaneous and induced septic abortions. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1042-1048.

7. Rana A, Pradhan N, Gurung G, Singh M. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):3-8.

8. Abbasi S, Jamal A, Eslamian L, Marsousi V. Role of clinical and ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):704-707.

9. Esmaeillou H, Jamal A, Eslamian L, et al. Accurate detection of retained products of conception after first- and second-trimester abortion by color doppler sonography. J Med Ultrasound. 2015;23(7):34-38.

10. Finkielman JD, De Feo FD, Heller PG, Afessa B. The clinical course of patients with septic abortion admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1097-1102.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

12. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD001067.

Postpartum HIV treatment reduces key maternal illnesses

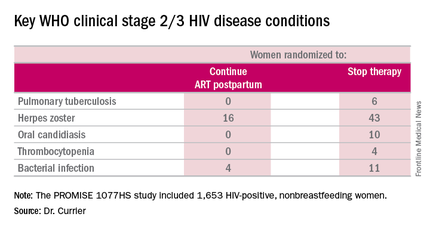

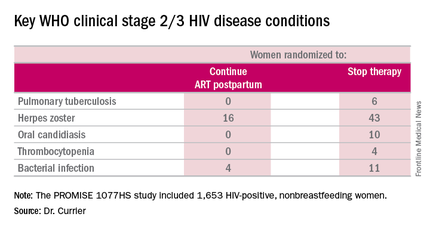

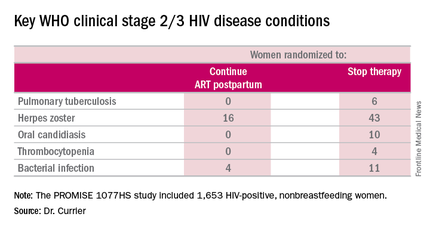

DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA – HIV-infected women who remained on antiretroviral therapy throughout the postpartum period reduced their risk of clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events by 53%, compared with those who stopped treatment postpartum in the PROMISE 1077HS trial, Judith Currier, MD, reported at the 21st International AIDS Conference.

PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere) is an ongoing multinational, multicomponent series of clinical trials. PROMISE 1077HS was designed to assess the risks and benefits of continued antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with stopping therapy among nonbreastfeeding women postpartum, explained Dr. Currier, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles.

PROMISE 1077HS included 1,653 HIV-positive women in the United States and seven low- or middle-income countries. All participants were relatively healthy as evidenced by their median CD4+ count of 550 cells/mm3 prior to starting ART in pregnancy. None were planning to breastfeed. Upon delivery, the women were randomized to continue ART – the chief regimen was ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (Kaletra) plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) – or stop therapy, restarting only when their CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3.

Participants were prospectively followed for a median of 2.3 years post delivery. At that point, in summer 2015, the results of the landmark START trial were released (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373[9]:795-807), paving the way for the current global strategy of ART for life in HIV-infected patients regardless of their CD4+ cell count.

The primary efficacy endpoint in PROMISE 1077HS was a composite of an AIDS event, death, or a serious cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic event. In this relatively healthy population, too few of these events occurred to allow the researchers to draw conclusions (four in the continued-ART group and six in the controls who stopped ART post partum).

But the secondary endpoint of time to World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events was a different story. A total of 39 of these events occurred in the continued-ART group, for a rate of 2.02% per year, compared with 80 events and a rate of 4.36% per year in controls. That difference translated into a 53% relative risk reduction. Some key WHO clinical stage 2 and 3 HIV disease events include pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, thrombocytopenia, and bacterial infection.

Fully 23% of patients in the continued-ART group had laboratory-confirmed virologic failure as defined by a viral load of HIV RNA in excess of 1,000 copies/mL after at least 24 weeks of postpartum ART. Additionally, resistance testing indicated two-thirds of affected patients showed no evidence of resistance at the time of virologic failure, meaning their viremia was due to nonadherence to ART.

“This virologic failure rate highlights the importance of the challenge of adherence in this population,” Dr. Currier said. “Interventions to improve adherence as well as studies to examine newer regimens with a high genetic barrier to resistance are needed to ensure maximal long-term benefit from this strategy of continued ART postpartum.”

The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA – HIV-infected women who remained on antiretroviral therapy throughout the postpartum period reduced their risk of clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events by 53%, compared with those who stopped treatment postpartum in the PROMISE 1077HS trial, Judith Currier, MD, reported at the 21st International AIDS Conference.

PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere) is an ongoing multinational, multicomponent series of clinical trials. PROMISE 1077HS was designed to assess the risks and benefits of continued antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with stopping therapy among nonbreastfeeding women postpartum, explained Dr. Currier, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles.

PROMISE 1077HS included 1,653 HIV-positive women in the United States and seven low- or middle-income countries. All participants were relatively healthy as evidenced by their median CD4+ count of 550 cells/mm3 prior to starting ART in pregnancy. None were planning to breastfeed. Upon delivery, the women were randomized to continue ART – the chief regimen was ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (Kaletra) plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) – or stop therapy, restarting only when their CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3.

Participants were prospectively followed for a median of 2.3 years post delivery. At that point, in summer 2015, the results of the landmark START trial were released (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373[9]:795-807), paving the way for the current global strategy of ART for life in HIV-infected patients regardless of their CD4+ cell count.

The primary efficacy endpoint in PROMISE 1077HS was a composite of an AIDS event, death, or a serious cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic event. In this relatively healthy population, too few of these events occurred to allow the researchers to draw conclusions (four in the continued-ART group and six in the controls who stopped ART post partum).

But the secondary endpoint of time to World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events was a different story. A total of 39 of these events occurred in the continued-ART group, for a rate of 2.02% per year, compared with 80 events and a rate of 4.36% per year in controls. That difference translated into a 53% relative risk reduction. Some key WHO clinical stage 2 and 3 HIV disease events include pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, thrombocytopenia, and bacterial infection.

Fully 23% of patients in the continued-ART group had laboratory-confirmed virologic failure as defined by a viral load of HIV RNA in excess of 1,000 copies/mL after at least 24 weeks of postpartum ART. Additionally, resistance testing indicated two-thirds of affected patients showed no evidence of resistance at the time of virologic failure, meaning their viremia was due to nonadherence to ART.

“This virologic failure rate highlights the importance of the challenge of adherence in this population,” Dr. Currier said. “Interventions to improve adherence as well as studies to examine newer regimens with a high genetic barrier to resistance are needed to ensure maximal long-term benefit from this strategy of continued ART postpartum.”

The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA – HIV-infected women who remained on antiretroviral therapy throughout the postpartum period reduced their risk of clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events by 53%, compared with those who stopped treatment postpartum in the PROMISE 1077HS trial, Judith Currier, MD, reported at the 21st International AIDS Conference.

PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere) is an ongoing multinational, multicomponent series of clinical trials. PROMISE 1077HS was designed to assess the risks and benefits of continued antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with stopping therapy among nonbreastfeeding women postpartum, explained Dr. Currier, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles.

PROMISE 1077HS included 1,653 HIV-positive women in the United States and seven low- or middle-income countries. All participants were relatively healthy as evidenced by their median CD4+ count of 550 cells/mm3 prior to starting ART in pregnancy. None were planning to breastfeed. Upon delivery, the women were randomized to continue ART – the chief regimen was ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (Kaletra) plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) – or stop therapy, restarting only when their CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3.

Participants were prospectively followed for a median of 2.3 years post delivery. At that point, in summer 2015, the results of the landmark START trial were released (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373[9]:795-807), paving the way for the current global strategy of ART for life in HIV-infected patients regardless of their CD4+ cell count.

The primary efficacy endpoint in PROMISE 1077HS was a composite of an AIDS event, death, or a serious cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic event. In this relatively healthy population, too few of these events occurred to allow the researchers to draw conclusions (four in the continued-ART group and six in the controls who stopped ART post partum).

But the secondary endpoint of time to World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events was a different story. A total of 39 of these events occurred in the continued-ART group, for a rate of 2.02% per year, compared with 80 events and a rate of 4.36% per year in controls. That difference translated into a 53% relative risk reduction. Some key WHO clinical stage 2 and 3 HIV disease events include pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, thrombocytopenia, and bacterial infection.

Fully 23% of patients in the continued-ART group had laboratory-confirmed virologic failure as defined by a viral load of HIV RNA in excess of 1,000 copies/mL after at least 24 weeks of postpartum ART. Additionally, resistance testing indicated two-thirds of affected patients showed no evidence of resistance at the time of virologic failure, meaning their viremia was due to nonadherence to ART.

“This virologic failure rate highlights the importance of the challenge of adherence in this population,” Dr. Currier said. “Interventions to improve adherence as well as studies to examine newer regimens with a high genetic barrier to resistance are needed to ensure maximal long-term benefit from this strategy of continued ART postpartum.”

The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AIDS 2016

Key clinical point: Women with HIV should continue antiretroviral therapy post partum.

Major finding: HIV-infected women who continued antiretroviral therapy post partum experienced 53% fewer WHO clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events than women assigned to stop therapy after delivery.

Data source: The PROMISE 1077HS study included 1,653 HIV-positive, nonbreastfeeding women randomized to either continue or stop antiretroviral therapy post partum.

Disclosures: The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

Serious infections in second trimester increase epilepsy risk

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Febrile infections occurring in the second trimester appear to pose the greatest risk to the neurodevelopment of the fetus, a population based cohort study has shown.

In a review of 8,618,171 California births between January 1991 and December 2008, Ms. Hilary Haber, a third-year medical student at the University of California, Davis, and her coinvestigators found that maternal infections requiring hospitalizations during the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy, a relative risk of 2.3 of having a child with an intellectual disability, and a relative risk of 1.2 of having a child with autism.

Significant associations were observed between subcategories of infection and intellectual disability and epilepsy, particularly those of a bacterial cause and from respiratory and genitourinary sites. Overall, any maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 43% increased risk of epilepsy, a 33% increased risk of intellectual disability, and an 8% increased risk of autism.

The exact mechanism of action between the maternal infection and adverse fetal neurodevelopmental outcomes is still unclear, Ms. Haber said at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Next, we are considering which specific [maternal] infections we should look at,” Ms. Haber said in an interview. “There is something about febrile infections, so we want to narrow that down and better characterize the outcomes from mild, moderate, severe infections.”

Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Febrile infections occurring in the second trimester appear to pose the greatest risk to the neurodevelopment of the fetus, a population based cohort study has shown.

In a review of 8,618,171 California births between January 1991 and December 2008, Ms. Hilary Haber, a third-year medical student at the University of California, Davis, and her coinvestigators found that maternal infections requiring hospitalizations during the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy, a relative risk of 2.3 of having a child with an intellectual disability, and a relative risk of 1.2 of having a child with autism.

Significant associations were observed between subcategories of infection and intellectual disability and epilepsy, particularly those of a bacterial cause and from respiratory and genitourinary sites. Overall, any maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 43% increased risk of epilepsy, a 33% increased risk of intellectual disability, and an 8% increased risk of autism.

The exact mechanism of action between the maternal infection and adverse fetal neurodevelopmental outcomes is still unclear, Ms. Haber said at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Next, we are considering which specific [maternal] infections we should look at,” Ms. Haber said in an interview. “There is something about febrile infections, so we want to narrow that down and better characterize the outcomes from mild, moderate, severe infections.”

Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Febrile infections occurring in the second trimester appear to pose the greatest risk to the neurodevelopment of the fetus, a population based cohort study has shown.

In a review of 8,618,171 California births between January 1991 and December 2008, Ms. Hilary Haber, a third-year medical student at the University of California, Davis, and her coinvestigators found that maternal infections requiring hospitalizations during the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy, a relative risk of 2.3 of having a child with an intellectual disability, and a relative risk of 1.2 of having a child with autism.

Significant associations were observed between subcategories of infection and intellectual disability and epilepsy, particularly those of a bacterial cause and from respiratory and genitourinary sites. Overall, any maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 43% increased risk of epilepsy, a 33% increased risk of intellectual disability, and an 8% increased risk of autism.

The exact mechanism of action between the maternal infection and adverse fetal neurodevelopmental outcomes is still unclear, Ms. Haber said at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Next, we are considering which specific [maternal] infections we should look at,” Ms. Haber said in an interview. “There is something about febrile infections, so we want to narrow that down and better characterize the outcomes from mild, moderate, severe infections.”

Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT IDSOG

Key clinical point: Serious maternal infections in the second trimester pose an increased risk of having a child with epilepsy or intellectual disability.

Major finding: Maternal infections in the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy.

Data source: Retrospective, population-based cohort study of more than 8 million births between 1991 and 2008.

Disclosures: Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Should lower uterine segment thickness measurement be included in the TOLAC decision-making process?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

After having a previous cesarean delivery (CD), women who subsequently become pregnant inevitably face the decision to undergo a repeat CD or attempt a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC). Currently in the United States, 83% of women with a prior uterine scar are delivered by repeat CD.1 According to the Consortium on Safe Labor, more than half of all CD indications are attributed to having a prior uterine scar.1 Furthermore, only 28% of women attempt a TOLAC, with a successful vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate of approximately 57%.1

The reason for the low TOLAC rate is multifactorial, but a primary concern may be the safety risk of a TOLAC as it relates to uterine rupture, a rare but potentially catastrophic complication. In a large, multicenter prospective observational trial of more than 17,800 women attempting a TOLAC, the symptomatic uterine rupture rate was 0.7%.2 As such, efforts to identify women at highest risk for uterine rupture and those with characteristics predictive of a successful VBAC have remained ongoing. Jastrow and colleagues have expanded this body of knowledge with their prospective cohort study.

Details of the study

The researchers assessed lower uterine segment thickness via vaginal and abdominal ultrasound at 34 to 38 weeks’ gestation in more than 1,850 women with a previous CD. Women enrolled in the trial were classified into 3 risk categories based on lower uterine segment thickness: high risk (<2.0 mm), intermediate risk (2.0 to 2.4 mm), and low risk (≥2.5 mm). The investigators’ objective was to estimate the occurrence of uterine rupture when this measurement was included in the decision-making process on mode of delivery.

An important aspect of this study involved how the provider discussed the mode of delivery with the patient after the lower uterine segment measurement was obtained. Both the provider and the patient were informed of the risk category, and further counseling included the following:

- average overall uterine rupture risk, 0.5% to 1%

- if <2.0 mm, uterine rupture risk likely >1%

- if ≥2.5 mm, uterine rupture risk likely <0.5%

- uterine rupture risks (including perinatal asphyxia and death)

- maternal and neonatal complications of cesarean

- estimation of likelihood for successful VBAC.

How did risk-stratified women fare?

In approximately 1,000 cases, the authors reported no symptomatic uterine ruptures. Of particular interest, however, is the rate of women attempting a TOLAC in each category:

- 194 women with high risk

- 9% underwent a TOLAC

- 82% had a successful vaginal birth

- 217 women with intermediate risk

- 42% underwent a TOLAC

- 78% had a successful vaginal birth

- 1,438 women with low risk

- 61% underwent a TOLAC

- 66% had a successful vaginal birth.

Considering cesarean scar defect

Finally, uterine scar defects at CD in those who underwent a TOLAC were 0/3 (0%), 5/21 (25%), and 20/276 (7%) in the high-, intermediate-, and low-risk groups, respectively. Given the observational nature of the study, the authors suggest that uterine scar dehiscence may be predictive of labor dystocia, but it remains unclear if it predicts or is a prerequisite for subsequent uterine rupture if labor occurs.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, et al; Consortium on Safe Labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):326.e1–326.e10.

- Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;16;351(25):2581–2589.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

After having a previous cesarean delivery (CD), women who subsequently become pregnant inevitably face the decision to undergo a repeat CD or attempt a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC). Currently in the United States, 83% of women with a prior uterine scar are delivered by repeat CD.1 According to the Consortium on Safe Labor, more than half of all CD indications are attributed to having a prior uterine scar.1 Furthermore, only 28% of women attempt a TOLAC, with a successful vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate of approximately 57%.1

The reason for the low TOLAC rate is multifactorial, but a primary concern may be the safety risk of a TOLAC as it relates to uterine rupture, a rare but potentially catastrophic complication. In a large, multicenter prospective observational trial of more than 17,800 women attempting a TOLAC, the symptomatic uterine rupture rate was 0.7%.2 As such, efforts to identify women at highest risk for uterine rupture and those with characteristics predictive of a successful VBAC have remained ongoing. Jastrow and colleagues have expanded this body of knowledge with their prospective cohort study.

Details of the study

The researchers assessed lower uterine segment thickness via vaginal and abdominal ultrasound at 34 to 38 weeks’ gestation in more than 1,850 women with a previous CD. Women enrolled in the trial were classified into 3 risk categories based on lower uterine segment thickness: high risk (<2.0 mm), intermediate risk (2.0 to 2.4 mm), and low risk (≥2.5 mm). The investigators’ objective was to estimate the occurrence of uterine rupture when this measurement was included in the decision-making process on mode of delivery.

An important aspect of this study involved how the provider discussed the mode of delivery with the patient after the lower uterine segment measurement was obtained. Both the provider and the patient were informed of the risk category, and further counseling included the following:

- average overall uterine rupture risk, 0.5% to 1%

- if <2.0 mm, uterine rupture risk likely >1%

- if ≥2.5 mm, uterine rupture risk likely <0.5%

- uterine rupture risks (including perinatal asphyxia and death)

- maternal and neonatal complications of cesarean

- estimation of likelihood for successful VBAC.

How did risk-stratified women fare?

In approximately 1,000 cases, the authors reported no symptomatic uterine ruptures. Of particular interest, however, is the rate of women attempting a TOLAC in each category:

- 194 women with high risk

- 9% underwent a TOLAC

- 82% had a successful vaginal birth

- 217 women with intermediate risk

- 42% underwent a TOLAC

- 78% had a successful vaginal birth

- 1,438 women with low risk

- 61% underwent a TOLAC

- 66% had a successful vaginal birth.

Considering cesarean scar defect

Finally, uterine scar defects at CD in those who underwent a TOLAC were 0/3 (0%), 5/21 (25%), and 20/276 (7%) in the high-, intermediate-, and low-risk groups, respectively. Given the observational nature of the study, the authors suggest that uterine scar dehiscence may be predictive of labor dystocia, but it remains unclear if it predicts or is a prerequisite for subsequent uterine rupture if labor occurs.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

After having a previous cesarean delivery (CD), women who subsequently become pregnant inevitably face the decision to undergo a repeat CD or attempt a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC). Currently in the United States, 83% of women with a prior uterine scar are delivered by repeat CD.1 According to the Consortium on Safe Labor, more than half of all CD indications are attributed to having a prior uterine scar.1 Furthermore, only 28% of women attempt a TOLAC, with a successful vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate of approximately 57%.1

The reason for the low TOLAC rate is multifactorial, but a primary concern may be the safety risk of a TOLAC as it relates to uterine rupture, a rare but potentially catastrophic complication. In a large, multicenter prospective observational trial of more than 17,800 women attempting a TOLAC, the symptomatic uterine rupture rate was 0.7%.2 As such, efforts to identify women at highest risk for uterine rupture and those with characteristics predictive of a successful VBAC have remained ongoing. Jastrow and colleagues have expanded this body of knowledge with their prospective cohort study.

Details of the study

The researchers assessed lower uterine segment thickness via vaginal and abdominal ultrasound at 34 to 38 weeks’ gestation in more than 1,850 women with a previous CD. Women enrolled in the trial were classified into 3 risk categories based on lower uterine segment thickness: high risk (<2.0 mm), intermediate risk (2.0 to 2.4 mm), and low risk (≥2.5 mm). The investigators’ objective was to estimate the occurrence of uterine rupture when this measurement was included in the decision-making process on mode of delivery.

An important aspect of this study involved how the provider discussed the mode of delivery with the patient after the lower uterine segment measurement was obtained. Both the provider and the patient were informed of the risk category, and further counseling included the following:

- average overall uterine rupture risk, 0.5% to 1%

- if <2.0 mm, uterine rupture risk likely >1%

- if ≥2.5 mm, uterine rupture risk likely <0.5%

- uterine rupture risks (including perinatal asphyxia and death)

- maternal and neonatal complications of cesarean

- estimation of likelihood for successful VBAC.

How did risk-stratified women fare?

In approximately 1,000 cases, the authors reported no symptomatic uterine ruptures. Of particular interest, however, is the rate of women attempting a TOLAC in each category:

- 194 women with high risk

- 9% underwent a TOLAC

- 82% had a successful vaginal birth

- 217 women with intermediate risk

- 42% underwent a TOLAC

- 78% had a successful vaginal birth

- 1,438 women with low risk

- 61% underwent a TOLAC

- 66% had a successful vaginal birth.

Considering cesarean scar defect

Finally, uterine scar defects at CD in those who underwent a TOLAC were 0/3 (0%), 5/21 (25%), and 20/276 (7%) in the high-, intermediate-, and low-risk groups, respectively. Given the observational nature of the study, the authors suggest that uterine scar dehiscence may be predictive of labor dystocia, but it remains unclear if it predicts or is a prerequisite for subsequent uterine rupture if labor occurs.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, et al; Consortium on Safe Labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):326.e1–326.e10.

- Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;16;351(25):2581–2589.

- Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, et al; Consortium on Safe Labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):326.e1–326.e10.

- Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;16;351(25):2581–2589.

Letters to the Editor: Treating uterine atony

“STOP USING RECTAL MISOPROSTOL FOR THE TREATMENT OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE CAUSED BY UTERINE ATONY”Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2016)

The BEPCOP strategy for uterine atony

I appreciated Dr. Barbieri’s editorial about oxytocics for postpartum uterine atony and have personally noted the poor effectiveness of rectal misoprostol. I was reminded of his previous editorial that recommended administering intravenous (IV) oxytocin to postcesarean delivery patients for about 6 to 8 hours to reduce the risk of postoperative hemorrhage.

At my current hospital we usually use postpartum oxytocin, 30 units in 500 mL of 5% dextrose in water (D5W) for vaginal deliveries, and that infusion typically is administered for only 1 to 2 hours. Cesarean delivery patients receive oxytocin, 20 units in 1,000 mL of Ringer’s lactate, over the first 1 to 2 hours postoperatively. As an OB hospitalist I have been summoned occasionally to the bedside of patients who have uterine atony and hemorrhage, which usually occurs several hours after their oxytocin infusion has finished.

With this in mind I developed a proactive protocol that I call BEPCOP, an acronym for “Barnes’ Excellent Post Cesarean Oxytocin Protocol.” This involves simply running a 500-mL bag of oxytocin (30 units in 500 mL of D5W) at a constant rate of 50 mL/hour, which provides 50 mU/min oxytocin over the first 10 hours postdelivery.

I recommend BEPCOP for every cesarean delivery patient, as well as for any vaginally delivered patients who are at increased risk for atony, such as those with prolonged labor, large babies, polyhydramnios, multifetal gestation, chorioamnio‑nitis, and history of hemorrhage after a previous delivery, and for patients who are Jehovah’s Witnesses. It is important to reduce the rate of the mainline IV bag while the oxytocin is infusing to reduce the risk of fluid overload.

Since starting this routine I have seen a noticeable decrease in postpartum and postcesarean uterine atony.

E. Darryl Barnes, MD

Mechanicsville, Virginia

Nondissolving misoprostol is ineffective