User login

United States nears 1,400 cases of Zika in pregnant women

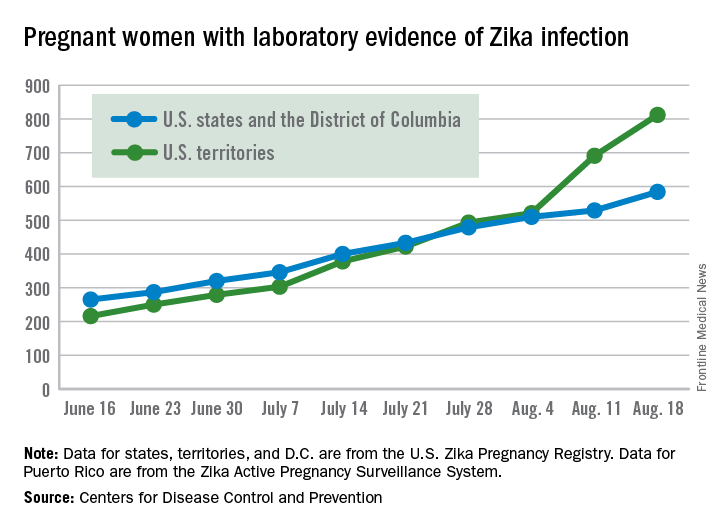

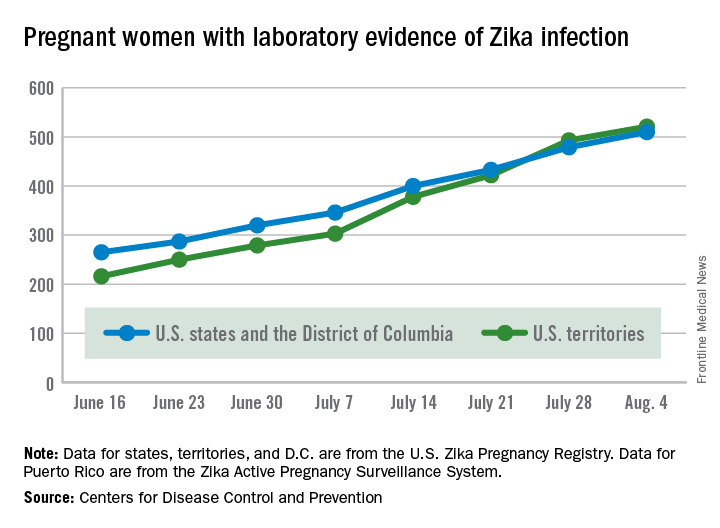

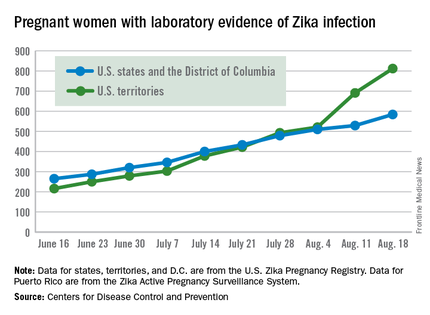

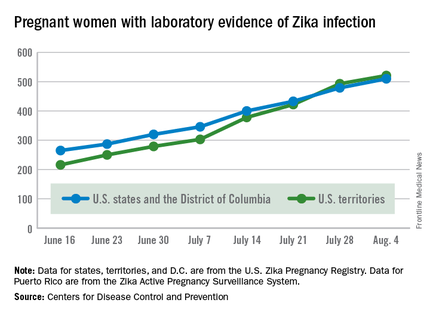

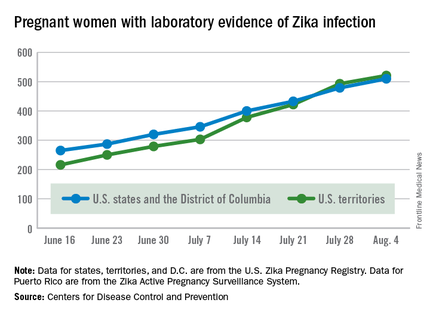

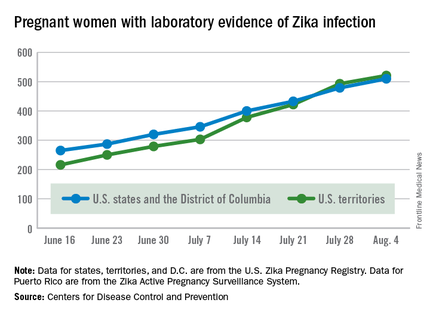

The number of new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika infection in the 50 states and the District of Columbia took a big jump during the week ending Aug. 18, 2016, while U.S. territories continued the strong increase that started the previous week, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 55 new cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women in the 50 states and D.C. reported the week ending Aug. 18. The number of new cases had been dropping, with 19 new cases the week of Aug. 11, 31 the week ending Aug. 4, and 46 the week ending July 28.

The territories had 121 new cases in the week ending Aug. 18, for a total of 176 new U.S. cases. For the year, there have been 1,396 cases of Zika in pregnant women in the United States: 584 in the states/D.C. and 812 in the territories, the CDC reported on Aug. 25. Among all Americans, there have been 11,528 cases of Zika virus in 2015-2016: 2,517 in the states/D.C. and 9,011 in the territories, of which 8,788 have occurred in Puerto Rico.

There were no new cases of Zika-related poor outcomes reported during the week ending Aug. 18, so the numbers of live-born infants who were born with birth defects remained at 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, and pregnancy losses with birth defects held at five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus–related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The number of new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika infection in the 50 states and the District of Columbia took a big jump during the week ending Aug. 18, 2016, while U.S. territories continued the strong increase that started the previous week, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 55 new cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women in the 50 states and D.C. reported the week ending Aug. 18. The number of new cases had been dropping, with 19 new cases the week of Aug. 11, 31 the week ending Aug. 4, and 46 the week ending July 28.

The territories had 121 new cases in the week ending Aug. 18, for a total of 176 new U.S. cases. For the year, there have been 1,396 cases of Zika in pregnant women in the United States: 584 in the states/D.C. and 812 in the territories, the CDC reported on Aug. 25. Among all Americans, there have been 11,528 cases of Zika virus in 2015-2016: 2,517 in the states/D.C. and 9,011 in the territories, of which 8,788 have occurred in Puerto Rico.

There were no new cases of Zika-related poor outcomes reported during the week ending Aug. 18, so the numbers of live-born infants who were born with birth defects remained at 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, and pregnancy losses with birth defects held at five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus–related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The number of new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika infection in the 50 states and the District of Columbia took a big jump during the week ending Aug. 18, 2016, while U.S. territories continued the strong increase that started the previous week, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 55 new cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women in the 50 states and D.C. reported the week ending Aug. 18. The number of new cases had been dropping, with 19 new cases the week of Aug. 11, 31 the week ending Aug. 4, and 46 the week ending July 28.

The territories had 121 new cases in the week ending Aug. 18, for a total of 176 new U.S. cases. For the year, there have been 1,396 cases of Zika in pregnant women in the United States: 584 in the states/D.C. and 812 in the territories, the CDC reported on Aug. 25. Among all Americans, there have been 11,528 cases of Zika virus in 2015-2016: 2,517 in the states/D.C. and 9,011 in the territories, of which 8,788 have occurred in Puerto Rico.

There were no new cases of Zika-related poor outcomes reported during the week ending Aug. 18, so the numbers of live-born infants who were born with birth defects remained at 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, and pregnancy losses with birth defects held at five in the states/D.C. and one in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus–related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika virus persists in serum for more than 2 months in newborns

Zika virus infections can persist for more than 2 months after birth in congenitally infected infants, indicating that viral shedding of Zika can take several weeks, according to an Aug. 24, 2016 research letter to the New England Journal of Medicine.

The case study described in the letter involves a male child born after 40 weeks’ gestation in Brazil to a mother who presented with Zika-like symptoms during the 26th week of pregnancy. The child was born with microcephaly – head circumference of 32.5 centimeters – but no signs of neurological abnormalities during the initial postnatal physical examination. Additionally, cerebrospinal fluid, ophthalmologic, and otoacoustic analyses were all deemed normal.

However, low brain parenchyma in the frontal and parietal lobes, along with calcification in the subcortical area and compensatory dilatation of the infratentorial supraventricular system was found via MRI. Furthermore, testing of serum, saliva, and urine at 54 days of age via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay came back positive for Zika virus. Serum tested at 67 days postbirth also was positive for Zika virus. Testing at day 216, however, showed no signs of Zika virus in serum.

“When the infant was examined on day 54, he had no obvious illness or evidence of any immunocompromising condition,” wrote lead author Danielle B.L. Oliveira, PhD, of the Universidade de São Paulo and her colleagues. “However, by 6 months of age, he showed neuropsychomotor developmental delay, with global hypertonia and spastic hemiplegia, with the right dominant side more severely affected.”

The report comes on the heels of a Florida Department of Health (DOH) announcement that the Zika virus has been found in a pregnant woman residing in Pinellas County, the first such case in that area, making it the third region of Florida in which Zika virus infection has been discovered. As of now, it is the only case of Zika virus in that area.

“DOH has begun door-to-door outreach in Pinellas County and mosquito abatement and reduction activities are also taking place,” the DOH announced in a statement. “DOH still believes ongoing transmission is only taking place within the small identified areas in Wynwood and Miami Beach in Miami-Dade County.”

Zika virus infections can persist for more than 2 months after birth in congenitally infected infants, indicating that viral shedding of Zika can take several weeks, according to an Aug. 24, 2016 research letter to the New England Journal of Medicine.

The case study described in the letter involves a male child born after 40 weeks’ gestation in Brazil to a mother who presented with Zika-like symptoms during the 26th week of pregnancy. The child was born with microcephaly – head circumference of 32.5 centimeters – but no signs of neurological abnormalities during the initial postnatal physical examination. Additionally, cerebrospinal fluid, ophthalmologic, and otoacoustic analyses were all deemed normal.

However, low brain parenchyma in the frontal and parietal lobes, along with calcification in the subcortical area and compensatory dilatation of the infratentorial supraventricular system was found via MRI. Furthermore, testing of serum, saliva, and urine at 54 days of age via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay came back positive for Zika virus. Serum tested at 67 days postbirth also was positive for Zika virus. Testing at day 216, however, showed no signs of Zika virus in serum.

“When the infant was examined on day 54, he had no obvious illness or evidence of any immunocompromising condition,” wrote lead author Danielle B.L. Oliveira, PhD, of the Universidade de São Paulo and her colleagues. “However, by 6 months of age, he showed neuropsychomotor developmental delay, with global hypertonia and spastic hemiplegia, with the right dominant side more severely affected.”

The report comes on the heels of a Florida Department of Health (DOH) announcement that the Zika virus has been found in a pregnant woman residing in Pinellas County, the first such case in that area, making it the third region of Florida in which Zika virus infection has been discovered. As of now, it is the only case of Zika virus in that area.

“DOH has begun door-to-door outreach in Pinellas County and mosquito abatement and reduction activities are also taking place,” the DOH announced in a statement. “DOH still believes ongoing transmission is only taking place within the small identified areas in Wynwood and Miami Beach in Miami-Dade County.”

Zika virus infections can persist for more than 2 months after birth in congenitally infected infants, indicating that viral shedding of Zika can take several weeks, according to an Aug. 24, 2016 research letter to the New England Journal of Medicine.

The case study described in the letter involves a male child born after 40 weeks’ gestation in Brazil to a mother who presented with Zika-like symptoms during the 26th week of pregnancy. The child was born with microcephaly – head circumference of 32.5 centimeters – but no signs of neurological abnormalities during the initial postnatal physical examination. Additionally, cerebrospinal fluid, ophthalmologic, and otoacoustic analyses were all deemed normal.

However, low brain parenchyma in the frontal and parietal lobes, along with calcification in the subcortical area and compensatory dilatation of the infratentorial supraventricular system was found via MRI. Furthermore, testing of serum, saliva, and urine at 54 days of age via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay came back positive for Zika virus. Serum tested at 67 days postbirth also was positive for Zika virus. Testing at day 216, however, showed no signs of Zika virus in serum.

“When the infant was examined on day 54, he had no obvious illness or evidence of any immunocompromising condition,” wrote lead author Danielle B.L. Oliveira, PhD, of the Universidade de São Paulo and her colleagues. “However, by 6 months of age, he showed neuropsychomotor developmental delay, with global hypertonia and spastic hemiplegia, with the right dominant side more severely affected.”

The report comes on the heels of a Florida Department of Health (DOH) announcement that the Zika virus has been found in a pregnant woman residing in Pinellas County, the first such case in that area, making it the third region of Florida in which Zika virus infection has been discovered. As of now, it is the only case of Zika virus in that area.

“DOH has begun door-to-door outreach in Pinellas County and mosquito abatement and reduction activities are also taking place,” the DOH announced in a statement. “DOH still believes ongoing transmission is only taking place within the small identified areas in Wynwood and Miami Beach in Miami-Dade County.”

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

U.S. breastfeeding rates rise for newborns

More than 80% of mothers in the United States started breastfeeding their infants at birth in 2013, 52% were breastfeeding at 6 months, and 30% were breastfeeding at 12 months, according to a breastfeeding report card from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall, 29 states, including Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, have met the Healthy People 2020 objective of 81.9% of infants who have ever been breastfed. However, only 12 states met the breastfeeding goal of 60.6% of infants breastfeeding at 6 months of age.

“High breastfeeding initiation rates show that most mothers in the U.S. want to breastfeed and are trying to do so,” according to the report. But the lower rates at 6 and 12 months “suggest that mothers, in part, may not be getting the support they need, such as from health care providers, family members, and employers.”

In the report, CDC officials call on states to use their breastfeeding statistics as a call to action for goals including monitoring breastfeeding progress, sharing success stories from effective hospital and community programs, building state profiles of community breastfeeding support, and identifying ways to increase breastfeeding rates through maternity care programs and peer and professional support networks.

The 2016 Breastfeeding Report Card included data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The data were taken from the U.S. National Immunization Surveys from 2014 and 2015 and referred to infants born in 2013. “Since breastfeeding data are obtained by maternal recall when children are between 19 and 35 months of age, breastfeeding rates are analyzed by birth cohort rather than survey year,” the researchers noted.

Read the complete findings on the CDC website.

More than 80% of mothers in the United States started breastfeeding their infants at birth in 2013, 52% were breastfeeding at 6 months, and 30% were breastfeeding at 12 months, according to a breastfeeding report card from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall, 29 states, including Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, have met the Healthy People 2020 objective of 81.9% of infants who have ever been breastfed. However, only 12 states met the breastfeeding goal of 60.6% of infants breastfeeding at 6 months of age.

“High breastfeeding initiation rates show that most mothers in the U.S. want to breastfeed and are trying to do so,” according to the report. But the lower rates at 6 and 12 months “suggest that mothers, in part, may not be getting the support they need, such as from health care providers, family members, and employers.”

In the report, CDC officials call on states to use their breastfeeding statistics as a call to action for goals including monitoring breastfeeding progress, sharing success stories from effective hospital and community programs, building state profiles of community breastfeeding support, and identifying ways to increase breastfeeding rates through maternity care programs and peer and professional support networks.

The 2016 Breastfeeding Report Card included data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The data were taken from the U.S. National Immunization Surveys from 2014 and 2015 and referred to infants born in 2013. “Since breastfeeding data are obtained by maternal recall when children are between 19 and 35 months of age, breastfeeding rates are analyzed by birth cohort rather than survey year,” the researchers noted.

Read the complete findings on the CDC website.

More than 80% of mothers in the United States started breastfeeding their infants at birth in 2013, 52% were breastfeeding at 6 months, and 30% were breastfeeding at 12 months, according to a breastfeeding report card from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall, 29 states, including Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, have met the Healthy People 2020 objective of 81.9% of infants who have ever been breastfed. However, only 12 states met the breastfeeding goal of 60.6% of infants breastfeeding at 6 months of age.

“High breastfeeding initiation rates show that most mothers in the U.S. want to breastfeed and are trying to do so,” according to the report. But the lower rates at 6 and 12 months “suggest that mothers, in part, may not be getting the support they need, such as from health care providers, family members, and employers.”

In the report, CDC officials call on states to use their breastfeeding statistics as a call to action for goals including monitoring breastfeeding progress, sharing success stories from effective hospital and community programs, building state profiles of community breastfeeding support, and identifying ways to increase breastfeeding rates through maternity care programs and peer and professional support networks.

The 2016 Breastfeeding Report Card included data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The data were taken from the U.S. National Immunization Surveys from 2014 and 2015 and referred to infants born in 2013. “Since breastfeeding data are obtained by maternal recall when children are between 19 and 35 months of age, breastfeeding rates are analyzed by birth cohort rather than survey year,” the researchers noted.

Read the complete findings on the CDC website.

Zika virus pits pregnant women against time, knowledge gaps

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – The scramble to learn exactly how and when after infection the Zika virus affects the developing fetus has put pregnant women at the center of an unprecedented infectious disease emergency response.

“It’s the most complicated infectious disease response we’ve ever done,” Dana Meaney-Delman, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told an audience at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology. “It’s also the first time an emergency response team has included an ob.gyn.”

Although research into Zika virus is happening at breakneck speed, every finding seems to lead to still more questions. “It’s hard to keep up,” said Dr. Meaney-Delman, who is a Clinical Deputy on the Pregnancy and Birth Defects Task Force, part of the CDC’s Zika virus response.

What is known

What is known is that Zika virus is primarily vector-borne, either manifesting as a mild illness or remaining subclinical. The virus is also communicable through male-to-female sex, female-to-female sex, blood donation, and organ transplantation. Once infected, one is immune; if symptomatic, the presentation clears within a couple of weeks. If a woman is infected during pregnancy, it can be transmitted to the developing fetus, including at the time of birth, according to Dr. Meaney-Delman.

“We know transmission can occur in any trimester. We’ve seen it in the placenta, in amniotic fluid, in the brain, as well as in the brains of infants who have died,” she said.

Whether the virus poses a risk to the fetus around the time of conception is not clear, but Dr. Meaney-Delman said that since other infections such as rubella and cytomegalovirus do pose a risk, the CDC is issuing Zika guidance accordingly.

Despite an initial theory that pregnant women were more susceptible to Zika infection, there is no evidence to date confirming this, but “the combination of mosquitoes and sexual transmission really puts a woman of reproductive age at risk,” said Catherine Y. Spong, MD, who also spoke during the meeting. Dr. Spong is acting director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Based on data derived from other flaviviruses, the “good news” is that infected nonpregnant women who later want to conceive do not have a higher risk of bearing a child with Zika-related complications, according to Dr. Meaney-Delman.

Abnormalities seen and unseen

During the initial stages of the Zika outbreak in Brazil, the spiking rate of babies born with microcephaly attracted the most attention; yet it is now apparent that children were also born with a growing list of other Zika-associated pregnancy outcomes that likely were missed at the time, according to Dr. Spong.

“That’s not to say that a child that doesn’t have microcephaly does or doesn’t have some of these other complications. We don’t know; they weren’t studied because they didn’t have the microcephaly,” Dr Spong said. “To get the data right, you need to follow all the children.”

Brain abnormalities such as ventriculomegaly and intracranial calcifications, as well as a range of growth abnormalities, miscarriage, and stillbirth are increasingly associated with infants born to infected women. Data is also beginning to link Zika virus to limb abnormalities, hypertonia, hearing loss, damage to the eyes and central nervous system, and seizures.

The World Health Organization has also noted the involvement of the cardiac, genitourinary, and digestive systems in babies born to infected mothers in Panama and Colombia. “The caveat [to these data], is that all these women were symptomatic,” Dr. Spong said, noting that in Brazil, where the outbreak was first documented, 80% of the infected pregnant women were asymptomatic during the pregnancy.

“Just because the mother has no symptoms, she’s fine? That doesn’t make any sense to me,” Dr. Spong said. “We know that infections in pregnancy can result in long-term outcomes in kids that you don’t have the ability to diagnose at birth. We need to be cognizant of this and we need to study it.”

Although initial theories were that viremia in symptomatic women was likely higher, thus imparting a higher risk of infection in their fetus, Dr. Meaney-Delman said the number of asymptomatic women whose fetuses are affected has debunked this line of thinking.

Risk of infection during pregnancy

As to what the actual risk of Zika virus infection is during pregnancy, “honestly we don’t know,” said Dr. Spong. “There are modeling estimates that [it’s] between 1% and 13% in a first trimester infection, but we don’t have the hard and fast data.”

The Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) study, recently launched by the NIH, will provide a prospective look at birth outcomes in 10,000 women aged 15 years and older who will be followed throughout their pregnancies to determine if they become infected with Zika virus, and if so, how infection impacts birth outcomes.

The international, multi-site study will help clarify the timing of risk, Dr. Spong said, and is intended to elucidate pregnancy risks in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic women. The study will also help indicate whether nutritional, socioeconomic status, and other cofactors such as Dengue infection are implicated. Once born, all children in the study will be observed for a year. “Even if they have no abnormalities, after birth there could be developmental delays, or more subtle consequences later on in the child’s life,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

Meanwhile, researchers are attempting to map how varying levels of viremia affect transmission. Zika virus has been found in semen after 90 days in at least two studies, “and we don’t know if Zika can be transmitted through other bodily fluids,” Dr. Spong said.

Surveillance data from the CDC’s Zika Pregnancy Registry has shown viremia in symptomatic women can last up to 46 days after onset of symptoms. In at least one asymptomatic pregnant woman, viremia was detected 53 days after exposure. Another study found prolonged viremia – 10 weeks – in a patient who had Zika infection in her first trimester; imaging showed the fetus was developing normally until week 20, when signs of severe brain abnormalities were detected.

The emerging picture of Zika’s potential for prolonged viremia has prompted the CDC to recommend clinicians use reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing rather than serologic testing, as it is more sensitive and helps rule out other flavivirus infections, which require different management, Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

Potential mechanisms of action

“It’s clear that the virus does directly infect human cortical neural progenitor cells with very high efficiency, and in doing so, stunts their growth, dysregulates transcription, and causes cell death,” Dr. Spong said.

Researchers have also found that Zika replicates in subgroups of trophoblasts and endothelial cells, and in primary human placental macrophages, resulting in vascular damage and growth restriction. Other research suggests the virus spreads from basal and parietal decidua to chorionic villi and amniochorionic membranes, leading to the theory that uterine-placental suppression of the viral entry cofactor TIM1 could stop transmission to the fetus.

Prevention and management

CDC officials expect the current outbreak to mimic past flavivirus outbreaks which were contained locally in portions of the South and U.S. territories, Dr. Meaney-Delman said. Still, she emphasized that clinicians should screen patients, regardless of location. “Each pregnant women should be assessed for [vector] exposure, travel, and sexual exposure and asked about symptoms consistent with Zika virus,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

She also emphasized the importance of patients consistently using insect repellent and using condoms during pregnancy, as Zika has been detected in semen for as long as 6 months. “It’s been very hard to invoke this behavioral change in women, but it’s very effective.”

The CDC continues to update guidance, including how to evaluate newborns for Zika-related defects.

As for what resources might be needed in future to help affected families, in an interview Dr. Meaney-Delman said that depends on information still unknown. “Zika is a public health concern that we should be factoring in long term, but what we do about it will depend upon the outcomes,” she said. “If there are children that are born normal but who have lab evidence of Zika, then we will probably not do much. I don’t think we have a projection yet.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – The scramble to learn exactly how and when after infection the Zika virus affects the developing fetus has put pregnant women at the center of an unprecedented infectious disease emergency response.

“It’s the most complicated infectious disease response we’ve ever done,” Dana Meaney-Delman, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told an audience at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology. “It’s also the first time an emergency response team has included an ob.gyn.”

Although research into Zika virus is happening at breakneck speed, every finding seems to lead to still more questions. “It’s hard to keep up,” said Dr. Meaney-Delman, who is a Clinical Deputy on the Pregnancy and Birth Defects Task Force, part of the CDC’s Zika virus response.

What is known

What is known is that Zika virus is primarily vector-borne, either manifesting as a mild illness or remaining subclinical. The virus is also communicable through male-to-female sex, female-to-female sex, blood donation, and organ transplantation. Once infected, one is immune; if symptomatic, the presentation clears within a couple of weeks. If a woman is infected during pregnancy, it can be transmitted to the developing fetus, including at the time of birth, according to Dr. Meaney-Delman.

“We know transmission can occur in any trimester. We’ve seen it in the placenta, in amniotic fluid, in the brain, as well as in the brains of infants who have died,” she said.

Whether the virus poses a risk to the fetus around the time of conception is not clear, but Dr. Meaney-Delman said that since other infections such as rubella and cytomegalovirus do pose a risk, the CDC is issuing Zika guidance accordingly.

Despite an initial theory that pregnant women were more susceptible to Zika infection, there is no evidence to date confirming this, but “the combination of mosquitoes and sexual transmission really puts a woman of reproductive age at risk,” said Catherine Y. Spong, MD, who also spoke during the meeting. Dr. Spong is acting director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Based on data derived from other flaviviruses, the “good news” is that infected nonpregnant women who later want to conceive do not have a higher risk of bearing a child with Zika-related complications, according to Dr. Meaney-Delman.

Abnormalities seen and unseen

During the initial stages of the Zika outbreak in Brazil, the spiking rate of babies born with microcephaly attracted the most attention; yet it is now apparent that children were also born with a growing list of other Zika-associated pregnancy outcomes that likely were missed at the time, according to Dr. Spong.

“That’s not to say that a child that doesn’t have microcephaly does or doesn’t have some of these other complications. We don’t know; they weren’t studied because they didn’t have the microcephaly,” Dr Spong said. “To get the data right, you need to follow all the children.”

Brain abnormalities such as ventriculomegaly and intracranial calcifications, as well as a range of growth abnormalities, miscarriage, and stillbirth are increasingly associated with infants born to infected women. Data is also beginning to link Zika virus to limb abnormalities, hypertonia, hearing loss, damage to the eyes and central nervous system, and seizures.

The World Health Organization has also noted the involvement of the cardiac, genitourinary, and digestive systems in babies born to infected mothers in Panama and Colombia. “The caveat [to these data], is that all these women were symptomatic,” Dr. Spong said, noting that in Brazil, where the outbreak was first documented, 80% of the infected pregnant women were asymptomatic during the pregnancy.

“Just because the mother has no symptoms, she’s fine? That doesn’t make any sense to me,” Dr. Spong said. “We know that infections in pregnancy can result in long-term outcomes in kids that you don’t have the ability to diagnose at birth. We need to be cognizant of this and we need to study it.”

Although initial theories were that viremia in symptomatic women was likely higher, thus imparting a higher risk of infection in their fetus, Dr. Meaney-Delman said the number of asymptomatic women whose fetuses are affected has debunked this line of thinking.

Risk of infection during pregnancy

As to what the actual risk of Zika virus infection is during pregnancy, “honestly we don’t know,” said Dr. Spong. “There are modeling estimates that [it’s] between 1% and 13% in a first trimester infection, but we don’t have the hard and fast data.”

The Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) study, recently launched by the NIH, will provide a prospective look at birth outcomes in 10,000 women aged 15 years and older who will be followed throughout their pregnancies to determine if they become infected with Zika virus, and if so, how infection impacts birth outcomes.

The international, multi-site study will help clarify the timing of risk, Dr. Spong said, and is intended to elucidate pregnancy risks in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic women. The study will also help indicate whether nutritional, socioeconomic status, and other cofactors such as Dengue infection are implicated. Once born, all children in the study will be observed for a year. “Even if they have no abnormalities, after birth there could be developmental delays, or more subtle consequences later on in the child’s life,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

Meanwhile, researchers are attempting to map how varying levels of viremia affect transmission. Zika virus has been found in semen after 90 days in at least two studies, “and we don’t know if Zika can be transmitted through other bodily fluids,” Dr. Spong said.

Surveillance data from the CDC’s Zika Pregnancy Registry has shown viremia in symptomatic women can last up to 46 days after onset of symptoms. In at least one asymptomatic pregnant woman, viremia was detected 53 days after exposure. Another study found prolonged viremia – 10 weeks – in a patient who had Zika infection in her first trimester; imaging showed the fetus was developing normally until week 20, when signs of severe brain abnormalities were detected.

The emerging picture of Zika’s potential for prolonged viremia has prompted the CDC to recommend clinicians use reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing rather than serologic testing, as it is more sensitive and helps rule out other flavivirus infections, which require different management, Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

Potential mechanisms of action

“It’s clear that the virus does directly infect human cortical neural progenitor cells with very high efficiency, and in doing so, stunts their growth, dysregulates transcription, and causes cell death,” Dr. Spong said.

Researchers have also found that Zika replicates in subgroups of trophoblasts and endothelial cells, and in primary human placental macrophages, resulting in vascular damage and growth restriction. Other research suggests the virus spreads from basal and parietal decidua to chorionic villi and amniochorionic membranes, leading to the theory that uterine-placental suppression of the viral entry cofactor TIM1 could stop transmission to the fetus.

Prevention and management

CDC officials expect the current outbreak to mimic past flavivirus outbreaks which were contained locally in portions of the South and U.S. territories, Dr. Meaney-Delman said. Still, she emphasized that clinicians should screen patients, regardless of location. “Each pregnant women should be assessed for [vector] exposure, travel, and sexual exposure and asked about symptoms consistent with Zika virus,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

She also emphasized the importance of patients consistently using insect repellent and using condoms during pregnancy, as Zika has been detected in semen for as long as 6 months. “It’s been very hard to invoke this behavioral change in women, but it’s very effective.”

The CDC continues to update guidance, including how to evaluate newborns for Zika-related defects.

As for what resources might be needed in future to help affected families, in an interview Dr. Meaney-Delman said that depends on information still unknown. “Zika is a public health concern that we should be factoring in long term, but what we do about it will depend upon the outcomes,” she said. “If there are children that are born normal but who have lab evidence of Zika, then we will probably not do much. I don’t think we have a projection yet.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – The scramble to learn exactly how and when after infection the Zika virus affects the developing fetus has put pregnant women at the center of an unprecedented infectious disease emergency response.

“It’s the most complicated infectious disease response we’ve ever done,” Dana Meaney-Delman, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told an audience at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology. “It’s also the first time an emergency response team has included an ob.gyn.”

Although research into Zika virus is happening at breakneck speed, every finding seems to lead to still more questions. “It’s hard to keep up,” said Dr. Meaney-Delman, who is a Clinical Deputy on the Pregnancy and Birth Defects Task Force, part of the CDC’s Zika virus response.

What is known

What is known is that Zika virus is primarily vector-borne, either manifesting as a mild illness or remaining subclinical. The virus is also communicable through male-to-female sex, female-to-female sex, blood donation, and organ transplantation. Once infected, one is immune; if symptomatic, the presentation clears within a couple of weeks. If a woman is infected during pregnancy, it can be transmitted to the developing fetus, including at the time of birth, according to Dr. Meaney-Delman.

“We know transmission can occur in any trimester. We’ve seen it in the placenta, in amniotic fluid, in the brain, as well as in the brains of infants who have died,” she said.

Whether the virus poses a risk to the fetus around the time of conception is not clear, but Dr. Meaney-Delman said that since other infections such as rubella and cytomegalovirus do pose a risk, the CDC is issuing Zika guidance accordingly.

Despite an initial theory that pregnant women were more susceptible to Zika infection, there is no evidence to date confirming this, but “the combination of mosquitoes and sexual transmission really puts a woman of reproductive age at risk,” said Catherine Y. Spong, MD, who also spoke during the meeting. Dr. Spong is acting director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Based on data derived from other flaviviruses, the “good news” is that infected nonpregnant women who later want to conceive do not have a higher risk of bearing a child with Zika-related complications, according to Dr. Meaney-Delman.

Abnormalities seen and unseen

During the initial stages of the Zika outbreak in Brazil, the spiking rate of babies born with microcephaly attracted the most attention; yet it is now apparent that children were also born with a growing list of other Zika-associated pregnancy outcomes that likely were missed at the time, according to Dr. Spong.

“That’s not to say that a child that doesn’t have microcephaly does or doesn’t have some of these other complications. We don’t know; they weren’t studied because they didn’t have the microcephaly,” Dr Spong said. “To get the data right, you need to follow all the children.”

Brain abnormalities such as ventriculomegaly and intracranial calcifications, as well as a range of growth abnormalities, miscarriage, and stillbirth are increasingly associated with infants born to infected women. Data is also beginning to link Zika virus to limb abnormalities, hypertonia, hearing loss, damage to the eyes and central nervous system, and seizures.

The World Health Organization has also noted the involvement of the cardiac, genitourinary, and digestive systems in babies born to infected mothers in Panama and Colombia. “The caveat [to these data], is that all these women were symptomatic,” Dr. Spong said, noting that in Brazil, where the outbreak was first documented, 80% of the infected pregnant women were asymptomatic during the pregnancy.

“Just because the mother has no symptoms, she’s fine? That doesn’t make any sense to me,” Dr. Spong said. “We know that infections in pregnancy can result in long-term outcomes in kids that you don’t have the ability to diagnose at birth. We need to be cognizant of this and we need to study it.”

Although initial theories were that viremia in symptomatic women was likely higher, thus imparting a higher risk of infection in their fetus, Dr. Meaney-Delman said the number of asymptomatic women whose fetuses are affected has debunked this line of thinking.

Risk of infection during pregnancy

As to what the actual risk of Zika virus infection is during pregnancy, “honestly we don’t know,” said Dr. Spong. “There are modeling estimates that [it’s] between 1% and 13% in a first trimester infection, but we don’t have the hard and fast data.”

The Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) study, recently launched by the NIH, will provide a prospective look at birth outcomes in 10,000 women aged 15 years and older who will be followed throughout their pregnancies to determine if they become infected with Zika virus, and if so, how infection impacts birth outcomes.

The international, multi-site study will help clarify the timing of risk, Dr. Spong said, and is intended to elucidate pregnancy risks in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic women. The study will also help indicate whether nutritional, socioeconomic status, and other cofactors such as Dengue infection are implicated. Once born, all children in the study will be observed for a year. “Even if they have no abnormalities, after birth there could be developmental delays, or more subtle consequences later on in the child’s life,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

Meanwhile, researchers are attempting to map how varying levels of viremia affect transmission. Zika virus has been found in semen after 90 days in at least two studies, “and we don’t know if Zika can be transmitted through other bodily fluids,” Dr. Spong said.

Surveillance data from the CDC’s Zika Pregnancy Registry has shown viremia in symptomatic women can last up to 46 days after onset of symptoms. In at least one asymptomatic pregnant woman, viremia was detected 53 days after exposure. Another study found prolonged viremia – 10 weeks – in a patient who had Zika infection in her first trimester; imaging showed the fetus was developing normally until week 20, when signs of severe brain abnormalities were detected.

The emerging picture of Zika’s potential for prolonged viremia has prompted the CDC to recommend clinicians use reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing rather than serologic testing, as it is more sensitive and helps rule out other flavivirus infections, which require different management, Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

Potential mechanisms of action

“It’s clear that the virus does directly infect human cortical neural progenitor cells with very high efficiency, and in doing so, stunts their growth, dysregulates transcription, and causes cell death,” Dr. Spong said.

Researchers have also found that Zika replicates in subgroups of trophoblasts and endothelial cells, and in primary human placental macrophages, resulting in vascular damage and growth restriction. Other research suggests the virus spreads from basal and parietal decidua to chorionic villi and amniochorionic membranes, leading to the theory that uterine-placental suppression of the viral entry cofactor TIM1 could stop transmission to the fetus.

Prevention and management

CDC officials expect the current outbreak to mimic past flavivirus outbreaks which were contained locally in portions of the South and U.S. territories, Dr. Meaney-Delman said. Still, she emphasized that clinicians should screen patients, regardless of location. “Each pregnant women should be assessed for [vector] exposure, travel, and sexual exposure and asked about symptoms consistent with Zika virus,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

She also emphasized the importance of patients consistently using insect repellent and using condoms during pregnancy, as Zika has been detected in semen for as long as 6 months. “It’s been very hard to invoke this behavioral change in women, but it’s very effective.”

The CDC continues to update guidance, including how to evaluate newborns for Zika-related defects.

As for what resources might be needed in future to help affected families, in an interview Dr. Meaney-Delman said that depends on information still unknown. “Zika is a public health concern that we should be factoring in long term, but what we do about it will depend upon the outcomes,” she said. “If there are children that are born normal but who have lab evidence of Zika, then we will probably not do much. I don’t think we have a projection yet.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT IDSOG

SAGE-547 for depression: Cause for caution and optimism

The importance of postpartum depression, both in terms of its prevalence and the need for appropriate screening and effective treatments, has become an increasingly important area of focus for clinicians, patients, and policymakers. This derives from more than a decade of data on the significant prevalence of the condition, with roughly 10% of women meeting the criteria for major or minor depression during the first 3-6 months post partum.

Over the last 5 years, interest has centered around establishing mechanisms for appropriate perinatal depression screening, most notably the January 2016 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that all adults should be screened for depression, including the at-risk populations of pregnant and postpartum women. In 2015, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed screening women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period using a validated tool. Unfortunately, we still lack data to support whether screening is effective in getting patients referred for treatment and if it leads to women accessing therapies that will actually get them well.

As we wait for that data and consider ways to best implement enhanced screening, it’s important to take stock of the available treatments for postpartum depression.

Seeking a rapid treatment

The current literature supports efficacy for nonpharmacologic therapies, such as interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, as well as several antidepressants. The efficacy of antidepressants – such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – has been demonstrated for postpartum depression, but these agents carry the typical limitations and concerns in terms of side effects and the amount of time required to ascertain if there is benefit. While these are the same challenges seen in treating depression in general, the time to response – often 4-8 weeks – is particularly problematic for postpartum women where the impact of depression on maternal morbidity and child development is so critical.

The field has been clamoring for agents that work more quickly. One possibility in that area is ketamine, which is being studied as a rapid treatment in major depression. The National Institutes of Health also has an initiative underway called RAPID (Rapidly Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression), aimed at identifying and testing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments that produce a response within days rather than weeks.

Recently, considerable interest has focused on SAGE-547, manufactured by Sage Therapeutics, which is a different type of antidepressant. The so-called neurosteriod is an allosteric modulator of the GABAA (gamma-aminobutyric acid type A) receptors. The product was granted fast-track status by the Food and Drug Administration to speed its development as a possible treatment for superrefractory status epilepticus, but it also is being studied for its potential in treating severe postpartum depression.

Approximately a year ago, there was preliminary evidence from an open-label study suggesting rapid response to SAGE-547 for women who received this medicine intravenously in a controlled hospital environment. And in July 2016, the manufacturer announced in a press release unpublished positive results from a small phase II controlled trial of SAGE-547 for the treatment of severe postpartum depression.

Specifically, this was a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial for 21 women who had severe depressive symptoms with a baseline score of at least 26 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). For some of the women, postpartum depression was not of new onset, but rather was an extension of depression that had manifested no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy. A total of 10 women received the drug, while 11 received placebo. Both groups received continuous intravenous infusion over a 60-hour period.

Consistent with the earlier report, participants receiving the active agent had a statistically significant reduction in HAM-D scores at 24 hours, compared with women who received the placebo. Seven out of 10 women who received the active drug achieved remission from depression at 60 hours, compared with only 1 of the 11 patients who received placebo. Even though the results derived from an extremely small sample, the signal for efficacy appears promising.

Of particular interest, there appeared to be a duration of benefit at 30 days’ follow-up. The medicine was well tolerated with no discontinuations due to adverse events, which were most commonly dizziness, sedation, or somnolence. The adverse events were about the same in both the drug and placebo groups.

Next steps

These early results have generated excitement, if not a “buzz,” in the field, given the rapid onset of antidepressant benefit and the apparent duration of the effect. But readers should be mindful that to date, the findings have not been peer reviewed and are available only through a company-issued press release. It is also noteworthy that on clinicaltrials.gov, the projected enrollment was 32, but 21 women enrolled. This may speak to the great difficulty in enrolling the sample and may ultimately reflect on the generalizability of the findings.

One significant challenge with SAGE-547 is the formulation. It’s hardly feasible for severely ill postpartum women to come to the hospital for 60 hours of treatment. The manufacturer will have to produce a reformulated compound that is able to sustain the efficacy signaled in this proof of concept study.

But even more importantly, we will need to see how the drug performs in a larger, rigorous phase IIB or phase III study to know if the signal of promise really translates into a potential viable treatment option for women with severe postpartum depression. When we have results from a randomized controlled trial with a substantially larger number of patients, then we’ll know whether the excitement is justified. It would be a significant advance for the field if this were to be the case.

The field of depression, in general, has been seeking an effective, rapid treatment for some time, and the role of neurosteriods has been spoken about for more than 2 decades. If postpartum women are in fact a subgroup who respond to this class of agents, then that would be an example of truly personalized medicine. But we won’t know that until the manufacturer does an appropriate large trial, which could take 2-4 years.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information and resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has no financial relationship with SAGE Therapeutics, but he has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

The importance of postpartum depression, both in terms of its prevalence and the need for appropriate screening and effective treatments, has become an increasingly important area of focus for clinicians, patients, and policymakers. This derives from more than a decade of data on the significant prevalence of the condition, with roughly 10% of women meeting the criteria for major or minor depression during the first 3-6 months post partum.

Over the last 5 years, interest has centered around establishing mechanisms for appropriate perinatal depression screening, most notably the January 2016 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that all adults should be screened for depression, including the at-risk populations of pregnant and postpartum women. In 2015, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed screening women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period using a validated tool. Unfortunately, we still lack data to support whether screening is effective in getting patients referred for treatment and if it leads to women accessing therapies that will actually get them well.

As we wait for that data and consider ways to best implement enhanced screening, it’s important to take stock of the available treatments for postpartum depression.

Seeking a rapid treatment

The current literature supports efficacy for nonpharmacologic therapies, such as interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, as well as several antidepressants. The efficacy of antidepressants – such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – has been demonstrated for postpartum depression, but these agents carry the typical limitations and concerns in terms of side effects and the amount of time required to ascertain if there is benefit. While these are the same challenges seen in treating depression in general, the time to response – often 4-8 weeks – is particularly problematic for postpartum women where the impact of depression on maternal morbidity and child development is so critical.

The field has been clamoring for agents that work more quickly. One possibility in that area is ketamine, which is being studied as a rapid treatment in major depression. The National Institutes of Health also has an initiative underway called RAPID (Rapidly Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression), aimed at identifying and testing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments that produce a response within days rather than weeks.

Recently, considerable interest has focused on SAGE-547, manufactured by Sage Therapeutics, which is a different type of antidepressant. The so-called neurosteriod is an allosteric modulator of the GABAA (gamma-aminobutyric acid type A) receptors. The product was granted fast-track status by the Food and Drug Administration to speed its development as a possible treatment for superrefractory status epilepticus, but it also is being studied for its potential in treating severe postpartum depression.

Approximately a year ago, there was preliminary evidence from an open-label study suggesting rapid response to SAGE-547 for women who received this medicine intravenously in a controlled hospital environment. And in July 2016, the manufacturer announced in a press release unpublished positive results from a small phase II controlled trial of SAGE-547 for the treatment of severe postpartum depression.

Specifically, this was a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial for 21 women who had severe depressive symptoms with a baseline score of at least 26 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). For some of the women, postpartum depression was not of new onset, but rather was an extension of depression that had manifested no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy. A total of 10 women received the drug, while 11 received placebo. Both groups received continuous intravenous infusion over a 60-hour period.

Consistent with the earlier report, participants receiving the active agent had a statistically significant reduction in HAM-D scores at 24 hours, compared with women who received the placebo. Seven out of 10 women who received the active drug achieved remission from depression at 60 hours, compared with only 1 of the 11 patients who received placebo. Even though the results derived from an extremely small sample, the signal for efficacy appears promising.

Of particular interest, there appeared to be a duration of benefit at 30 days’ follow-up. The medicine was well tolerated with no discontinuations due to adverse events, which were most commonly dizziness, sedation, or somnolence. The adverse events were about the same in both the drug and placebo groups.

Next steps

These early results have generated excitement, if not a “buzz,” in the field, given the rapid onset of antidepressant benefit and the apparent duration of the effect. But readers should be mindful that to date, the findings have not been peer reviewed and are available only through a company-issued press release. It is also noteworthy that on clinicaltrials.gov, the projected enrollment was 32, but 21 women enrolled. This may speak to the great difficulty in enrolling the sample and may ultimately reflect on the generalizability of the findings.

One significant challenge with SAGE-547 is the formulation. It’s hardly feasible for severely ill postpartum women to come to the hospital for 60 hours of treatment. The manufacturer will have to produce a reformulated compound that is able to sustain the efficacy signaled in this proof of concept study.

But even more importantly, we will need to see how the drug performs in a larger, rigorous phase IIB or phase III study to know if the signal of promise really translates into a potential viable treatment option for women with severe postpartum depression. When we have results from a randomized controlled trial with a substantially larger number of patients, then we’ll know whether the excitement is justified. It would be a significant advance for the field if this were to be the case.

The field of depression, in general, has been seeking an effective, rapid treatment for some time, and the role of neurosteriods has been spoken about for more than 2 decades. If postpartum women are in fact a subgroup who respond to this class of agents, then that would be an example of truly personalized medicine. But we won’t know that until the manufacturer does an appropriate large trial, which could take 2-4 years.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information and resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has no financial relationship with SAGE Therapeutics, but he has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

The importance of postpartum depression, both in terms of its prevalence and the need for appropriate screening and effective treatments, has become an increasingly important area of focus for clinicians, patients, and policymakers. This derives from more than a decade of data on the significant prevalence of the condition, with roughly 10% of women meeting the criteria for major or minor depression during the first 3-6 months post partum.

Over the last 5 years, interest has centered around establishing mechanisms for appropriate perinatal depression screening, most notably the January 2016 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that all adults should be screened for depression, including the at-risk populations of pregnant and postpartum women. In 2015, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed screening women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period using a validated tool. Unfortunately, we still lack data to support whether screening is effective in getting patients referred for treatment and if it leads to women accessing therapies that will actually get them well.

As we wait for that data and consider ways to best implement enhanced screening, it’s important to take stock of the available treatments for postpartum depression.

Seeking a rapid treatment

The current literature supports efficacy for nonpharmacologic therapies, such as interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, as well as several antidepressants. The efficacy of antidepressants – such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – has been demonstrated for postpartum depression, but these agents carry the typical limitations and concerns in terms of side effects and the amount of time required to ascertain if there is benefit. While these are the same challenges seen in treating depression in general, the time to response – often 4-8 weeks – is particularly problematic for postpartum women where the impact of depression on maternal morbidity and child development is so critical.

The field has been clamoring for agents that work more quickly. One possibility in that area is ketamine, which is being studied as a rapid treatment in major depression. The National Institutes of Health also has an initiative underway called RAPID (Rapidly Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression), aimed at identifying and testing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments that produce a response within days rather than weeks.

Recently, considerable interest has focused on SAGE-547, manufactured by Sage Therapeutics, which is a different type of antidepressant. The so-called neurosteriod is an allosteric modulator of the GABAA (gamma-aminobutyric acid type A) receptors. The product was granted fast-track status by the Food and Drug Administration to speed its development as a possible treatment for superrefractory status epilepticus, but it also is being studied for its potential in treating severe postpartum depression.

Approximately a year ago, there was preliminary evidence from an open-label study suggesting rapid response to SAGE-547 for women who received this medicine intravenously in a controlled hospital environment. And in July 2016, the manufacturer announced in a press release unpublished positive results from a small phase II controlled trial of SAGE-547 for the treatment of severe postpartum depression.

Specifically, this was a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial for 21 women who had severe depressive symptoms with a baseline score of at least 26 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). For some of the women, postpartum depression was not of new onset, but rather was an extension of depression that had manifested no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy. A total of 10 women received the drug, while 11 received placebo. Both groups received continuous intravenous infusion over a 60-hour period.

Consistent with the earlier report, participants receiving the active agent had a statistically significant reduction in HAM-D scores at 24 hours, compared with women who received the placebo. Seven out of 10 women who received the active drug achieved remission from depression at 60 hours, compared with only 1 of the 11 patients who received placebo. Even though the results derived from an extremely small sample, the signal for efficacy appears promising.

Of particular interest, there appeared to be a duration of benefit at 30 days’ follow-up. The medicine was well tolerated with no discontinuations due to adverse events, which were most commonly dizziness, sedation, or somnolence. The adverse events were about the same in both the drug and placebo groups.

Next steps

These early results have generated excitement, if not a “buzz,” in the field, given the rapid onset of antidepressant benefit and the apparent duration of the effect. But readers should be mindful that to date, the findings have not been peer reviewed and are available only through a company-issued press release. It is also noteworthy that on clinicaltrials.gov, the projected enrollment was 32, but 21 women enrolled. This may speak to the great difficulty in enrolling the sample and may ultimately reflect on the generalizability of the findings.

One significant challenge with SAGE-547 is the formulation. It’s hardly feasible for severely ill postpartum women to come to the hospital for 60 hours of treatment. The manufacturer will have to produce a reformulated compound that is able to sustain the efficacy signaled in this proof of concept study.

But even more importantly, we will need to see how the drug performs in a larger, rigorous phase IIB or phase III study to know if the signal of promise really translates into a potential viable treatment option for women with severe postpartum depression. When we have results from a randomized controlled trial with a substantially larger number of patients, then we’ll know whether the excitement is justified. It would be a significant advance for the field if this were to be the case.

The field of depression, in general, has been seeking an effective, rapid treatment for some time, and the role of neurosteriods has been spoken about for more than 2 decades. If postpartum women are in fact a subgroup who respond to this class of agents, then that would be an example of truly personalized medicine. But we won’t know that until the manufacturer does an appropriate large trial, which could take 2-4 years.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information and resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has no financial relationship with SAGE Therapeutics, but he has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Zika in pregnant women: CDC reports 189 new cases

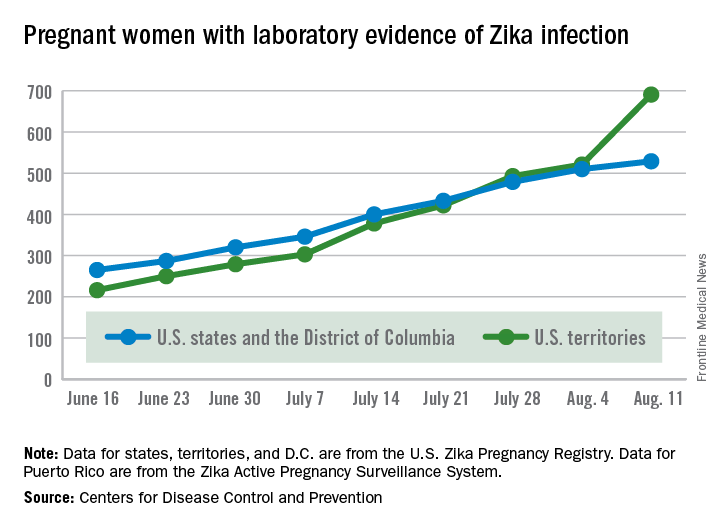

The number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection jumped by 189 during the week ending Aug. 11, with most of the increase coming in the U.S. territories, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The territories reported 170 new cases of Zika infection for that week, while the 50 states and the District of Columbia had 19 new cases in pregnant women. There have been 1,220 cases in pregnant women in the United States so far: 691 in the territories and 529 in the states and D.C. Among all Americans, there have been 10,295 cases of Zika: 8,035 in the territories and 2,260 in the states/D.C., the CDC reported.

The number of Zika-related poor outcomes did not change during the week ending Aug. 11. The number of liveborn infants born with birth defects stayed at 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, and the number of pregnancy losses with birth defects held at 5 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus–related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection jumped by 189 during the week ending Aug. 11, with most of the increase coming in the U.S. territories, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The territories reported 170 new cases of Zika infection for that week, while the 50 states and the District of Columbia had 19 new cases in pregnant women. There have been 1,220 cases in pregnant women in the United States so far: 691 in the territories and 529 in the states and D.C. Among all Americans, there have been 10,295 cases of Zika: 8,035 in the territories and 2,260 in the states/D.C., the CDC reported.

The number of Zika-related poor outcomes did not change during the week ending Aug. 11. The number of liveborn infants born with birth defects stayed at 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, and the number of pregnancy losses with birth defects held at 5 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus–related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection jumped by 189 during the week ending Aug. 11, with most of the increase coming in the U.S. territories, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The territories reported 170 new cases of Zika infection for that week, while the 50 states and the District of Columbia had 19 new cases in pregnant women. There have been 1,220 cases in pregnant women in the United States so far: 691 in the territories and 529 in the states and D.C. Among all Americans, there have been 10,295 cases of Zika: 8,035 in the territories and 2,260 in the states/D.C., the CDC reported.

The number of Zika-related poor outcomes did not change during the week ending Aug. 11. The number of liveborn infants born with birth defects stayed at 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, and the number of pregnancy losses with birth defects held at 5 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus–related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Antipsychotics in pregnancy pose no meaningful malformation risk

Antipsychotic use early in pregnancy does not appear to meaningfully increase the risk of congenital malformations, according to findings from a large Medicaid pregnancy cohort.

A possible exception is with the use of risperidone; a small increase in the risk for malformations seen with the drug should be viewed as “an initial safety signal that will require confirmation in other studies,” Krista F. Huybrechts, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues reported online Aug. 17 in JAMA Psychiatry.

In a nationwide sample of more than 1.3 million pregnant women with a live-born infant between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010, the rate of congenital malformations identified within 90 days after delivery was 32.7 per 1,000 births among 1,331,724 women with no antipsychotic (AP) exposure, compared with a rate of 44.5 per 1,000 births among 9,258 women who filled at least one prescription for an atypical AP during their first trimester, and 38.2 per 1,000 in 733 women who filled at least one prescription for a typical AP during their first trimester, the researchers found (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 17. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520).

On unadjusted analyses, an overall risk was seen with atypical AP exposure (relative risk, 1.36), but not with typical AP exposure (RR, 1.17). After adjusting for confounding variables, the risk was not statistically significant (RR, 1.05 and 0.90, respectively). The findings were similar for cardiac malformations, the researchers noted.

When agents were analyzed individually, a small increased risk in overall malformations and cardiac malformations was found with risperidone (RR, 1.26 for each).

“The findings for risperidone should be viewed as an initial safety signal that will require confirmation in other studies,” the researchers wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Huybrechts reported having no financial disclosures. Other authors disclosed receiving consulting fees and/or grant support from AstraZeneca, UCB, Alkermes, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Otsuka, Sunovion, Bayer, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, Cephalon, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda/Lundbeck, the National Institutes of Health, JDS Therapeutics, Noven Pharmaceuticals, and PamLab.

This “landmark report” by Huybrechts et al involves the largest population of women exposed to APs published to date, and addresses a “major source of concern for women and prescribers,” Katherine L. Wisner, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an editorial.

With the exception of risperidone, which was found to be associated with a 26% increase in the risk of overall and cardiac malformations, and possibly even greater risk among those who filled at least two AP prescriptions – and thus merits further exploration – AP use was found in the study to be safe.

“This study increases the field’s appetite for additional high-quality data on other maternal and offspring outcomes to improve the sophistication of risk-benefit decision making,” the authors wrote.

Nowhere in medicine is there a greater need for personalization of care, particularly when it comes to the treatment of serious mental illness with consideration of “pregnancy physiology and the mother’s capacity to provide sustenance for the growing fetus and newborn,” they wrote.

Dr. Wisner is with Northwestern University, Chicago. She reported that her department at Northwestern received contractual fees for her consultation to Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, who represented Pfizer Pharmaceutical Company in 2015. A coauthor, Christina Chambers, PhD, reported receiving research funding from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Teva. No other disclosures were reported. Their comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 17. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1538).

This “landmark report” by Huybrechts et al involves the largest population of women exposed to APs published to date, and addresses a “major source of concern for women and prescribers,” Katherine L. Wisner, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an editorial.

With the exception of risperidone, which was found to be associated with a 26% increase in the risk of overall and cardiac malformations, and possibly even greater risk among those who filled at least two AP prescriptions – and thus merits further exploration – AP use was found in the study to be safe.

“This study increases the field’s appetite for additional high-quality data on other maternal and offspring outcomes to improve the sophistication of risk-benefit decision making,” the authors wrote.

Nowhere in medicine is there a greater need for personalization of care, particularly when it comes to the treatment of serious mental illness with consideration of “pregnancy physiology and the mother’s capacity to provide sustenance for the growing fetus and newborn,” they wrote.

Dr. Wisner is with Northwestern University, Chicago. She reported that her department at Northwestern received contractual fees for her consultation to Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, who represented Pfizer Pharmaceutical Company in 2015. A coauthor, Christina Chambers, PhD, reported receiving research funding from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Teva. No other disclosures were reported. Their comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 17. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1538).

This “landmark report” by Huybrechts et al involves the largest population of women exposed to APs published to date, and addresses a “major source of concern for women and prescribers,” Katherine L. Wisner, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an editorial.

With the exception of risperidone, which was found to be associated with a 26% increase in the risk of overall and cardiac malformations, and possibly even greater risk among those who filled at least two AP prescriptions – and thus merits further exploration – AP use was found in the study to be safe.

“This study increases the field’s appetite for additional high-quality data on other maternal and offspring outcomes to improve the sophistication of risk-benefit decision making,” the authors wrote.

Nowhere in medicine is there a greater need for personalization of care, particularly when it comes to the treatment of serious mental illness with consideration of “pregnancy physiology and the mother’s capacity to provide sustenance for the growing fetus and newborn,” they wrote.

Dr. Wisner is with Northwestern University, Chicago. She reported that her department at Northwestern received contractual fees for her consultation to Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, who represented Pfizer Pharmaceutical Company in 2015. A coauthor, Christina Chambers, PhD, reported receiving research funding from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Teva. No other disclosures were reported. Their comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 17. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1538).

Antipsychotic use early in pregnancy does not appear to meaningfully increase the risk of congenital malformations, according to findings from a large Medicaid pregnancy cohort.