User login

Sexually transmitted Zika case confirmed in Texas

A report of sexually transmitted Zika virus infection has been confirmed in Texas, according to officials at the Dallas County Health and Human Services Department (DCHHS).

The patient was infected with Zika virus via sexual contact with an individual who returned home after becoming ill in a country where the virus is present. The department received confirmation from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 2.

“Now that we know Zika virus can be transmitted through sex, this increases our awareness campaign in educating the public about protecting themselves and others,” Zachary Thompson, DCHHS director, said in a statement.

See the full statement here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

A report of sexually transmitted Zika virus infection has been confirmed in Texas, according to officials at the Dallas County Health and Human Services Department (DCHHS).

The patient was infected with Zika virus via sexual contact with an individual who returned home after becoming ill in a country where the virus is present. The department received confirmation from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 2.

“Now that we know Zika virus can be transmitted through sex, this increases our awareness campaign in educating the public about protecting themselves and others,” Zachary Thompson, DCHHS director, said in a statement.

See the full statement here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

A report of sexually transmitted Zika virus infection has been confirmed in Texas, according to officials at the Dallas County Health and Human Services Department (DCHHS).

The patient was infected with Zika virus via sexual contact with an individual who returned home after becoming ill in a country where the virus is present. The department received confirmation from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 2.

“Now that we know Zika virus can be transmitted through sex, this increases our awareness campaign in educating the public about protecting themselves and others,” Zachary Thompson, DCHHS director, said in a statement.

See the full statement here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Heightened emphasis on sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

CDC: Screen women for alcohol, birth control use

An estimated 3.3 million U.S. women aged 15-44 years risk conceiving children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders by using alcohol but not birth control.

The finding has officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging physicians to screen this group for concomitant drinking and nonuse of contraception. The data come from an analysis of 4,303 nonpregnant, nonsterile women ages 15-44 years from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Family Growth, conducted by the CDC (MMWR. 2016;65:1-7.).

“Alcohol can permanently harm a developing baby before a woman knows she is pregnant,” Dr. Anne Schuchat, the CDC’s principal deputy director, said during a media briefing on Feb. 2. “About half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, and even if planned, most women won’t know they are pregnant for the first month or so, when they might still be drinking. The risk is real. Why take the chance?”

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) can include physical, behavioral, and intellectual disabilities that can last for a child’s lifetime. Dr, Schuchat said the CDC estimates that as many as 1 in 20 U.S. schoolchildren may have FASD. Currently, there are no data on what amounts of alcohol are safe for a woman to drink at any stage of pregnancy.

“Not drinking alcohol is one of the best things you can do to ensure the health of your baby,” Dr. Schuchat said.

For the study, a woman was considered at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy during the past month if she was nonsterile and had sex with a nonsterile male, drank any alcohol, and did not use contraception in the past month. The CDC found the weighted prevalence of alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk among U.S. women aged 15-44 years was 7.3%.

During a 1-month period, approximately 3.3 million U.S. women were at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. The highest risk group – at 10.4% – were women aged 25-29 years. The lowest risk group were those aged 15-20 years, at 2.2%.

Neither race nor ethnicity were found to be risk factors, although the risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy was higher among married and cohabitating women at 11.7% and 13.6% respectively, compared with their single counterparts (2.3%).

The study also found that three-quarters of women who want to get pregnant as soon as possible do not stop drinking alcohol after discontinuing contraception.

Physicians and other health care providers should advise women who want to become pregnant to stop drinking alcohol as soon as they stop using birth control, Dr. Schuchat said.

She added that physicians should screen all adults for alcohol use, not just women, even though that is not currently standard practice. “We think it should be more common to do on a regular basis.” Dr. Schuchat said the federal government requires most health plans to cover alcohol screening without cost to the patient.

The CDC recommends that physicians:

• Screen all adult female patients for alcohol use annually.

• Advise women to cease all alcohol intake if there is any chance at all that she could be pregnant.

• Counsel, refer, and follow-up with patients who need additional support to not drink while pregnant.

• Use correct billing codes to be reimbursed for screening and counseling.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which recommends that women completely abstain from alcohol during pregnancy, praised the CDC’s guidance that physicians routinely screen women regarding their alcohol use.

Dr. Mark S. DeFrancesco, ACOG president, said the other important message from the CDC report is that physicians should counsel women about contraception use.

“As the CDC notes, roughly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended. In many cases of unintended pregnancy, women inadvertently expose their fetuses to alcohol and its teratogenic effects prior to discovering that they are pregnant,” he said in statement. “This is just another reason why it’s so important that health care providers counsel women about how to prevent unintended pregnancy through use of the contraceptive method that is right for them. There are many benefits to helping women become pregnant only when they are ready, and avoiding alcohol exposure is one of them.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

An estimated 3.3 million U.S. women aged 15-44 years risk conceiving children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders by using alcohol but not birth control.

The finding has officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging physicians to screen this group for concomitant drinking and nonuse of contraception. The data come from an analysis of 4,303 nonpregnant, nonsterile women ages 15-44 years from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Family Growth, conducted by the CDC (MMWR. 2016;65:1-7.).

“Alcohol can permanently harm a developing baby before a woman knows she is pregnant,” Dr. Anne Schuchat, the CDC’s principal deputy director, said during a media briefing on Feb. 2. “About half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, and even if planned, most women won’t know they are pregnant for the first month or so, when they might still be drinking. The risk is real. Why take the chance?”

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) can include physical, behavioral, and intellectual disabilities that can last for a child’s lifetime. Dr, Schuchat said the CDC estimates that as many as 1 in 20 U.S. schoolchildren may have FASD. Currently, there are no data on what amounts of alcohol are safe for a woman to drink at any stage of pregnancy.

“Not drinking alcohol is one of the best things you can do to ensure the health of your baby,” Dr. Schuchat said.

For the study, a woman was considered at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy during the past month if she was nonsterile and had sex with a nonsterile male, drank any alcohol, and did not use contraception in the past month. The CDC found the weighted prevalence of alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk among U.S. women aged 15-44 years was 7.3%.

During a 1-month period, approximately 3.3 million U.S. women were at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. The highest risk group – at 10.4% – were women aged 25-29 years. The lowest risk group were those aged 15-20 years, at 2.2%.

Neither race nor ethnicity were found to be risk factors, although the risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy was higher among married and cohabitating women at 11.7% and 13.6% respectively, compared with their single counterparts (2.3%).

The study also found that three-quarters of women who want to get pregnant as soon as possible do not stop drinking alcohol after discontinuing contraception.

Physicians and other health care providers should advise women who want to become pregnant to stop drinking alcohol as soon as they stop using birth control, Dr. Schuchat said.

She added that physicians should screen all adults for alcohol use, not just women, even though that is not currently standard practice. “We think it should be more common to do on a regular basis.” Dr. Schuchat said the federal government requires most health plans to cover alcohol screening without cost to the patient.

The CDC recommends that physicians:

• Screen all adult female patients for alcohol use annually.

• Advise women to cease all alcohol intake if there is any chance at all that she could be pregnant.

• Counsel, refer, and follow-up with patients who need additional support to not drink while pregnant.

• Use correct billing codes to be reimbursed for screening and counseling.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which recommends that women completely abstain from alcohol during pregnancy, praised the CDC’s guidance that physicians routinely screen women regarding their alcohol use.

Dr. Mark S. DeFrancesco, ACOG president, said the other important message from the CDC report is that physicians should counsel women about contraception use.

“As the CDC notes, roughly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended. In many cases of unintended pregnancy, women inadvertently expose their fetuses to alcohol and its teratogenic effects prior to discovering that they are pregnant,” he said in statement. “This is just another reason why it’s so important that health care providers counsel women about how to prevent unintended pregnancy through use of the contraceptive method that is right for them. There are many benefits to helping women become pregnant only when they are ready, and avoiding alcohol exposure is one of them.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

An estimated 3.3 million U.S. women aged 15-44 years risk conceiving children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders by using alcohol but not birth control.

The finding has officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging physicians to screen this group for concomitant drinking and nonuse of contraception. The data come from an analysis of 4,303 nonpregnant, nonsterile women ages 15-44 years from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Family Growth, conducted by the CDC (MMWR. 2016;65:1-7.).

“Alcohol can permanently harm a developing baby before a woman knows she is pregnant,” Dr. Anne Schuchat, the CDC’s principal deputy director, said during a media briefing on Feb. 2. “About half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, and even if planned, most women won’t know they are pregnant for the first month or so, when they might still be drinking. The risk is real. Why take the chance?”

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) can include physical, behavioral, and intellectual disabilities that can last for a child’s lifetime. Dr, Schuchat said the CDC estimates that as many as 1 in 20 U.S. schoolchildren may have FASD. Currently, there are no data on what amounts of alcohol are safe for a woman to drink at any stage of pregnancy.

“Not drinking alcohol is one of the best things you can do to ensure the health of your baby,” Dr. Schuchat said.

For the study, a woman was considered at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy during the past month if she was nonsterile and had sex with a nonsterile male, drank any alcohol, and did not use contraception in the past month. The CDC found the weighted prevalence of alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk among U.S. women aged 15-44 years was 7.3%.

During a 1-month period, approximately 3.3 million U.S. women were at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. The highest risk group – at 10.4% – were women aged 25-29 years. The lowest risk group were those aged 15-20 years, at 2.2%.

Neither race nor ethnicity were found to be risk factors, although the risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy was higher among married and cohabitating women at 11.7% and 13.6% respectively, compared with their single counterparts (2.3%).

The study also found that three-quarters of women who want to get pregnant as soon as possible do not stop drinking alcohol after discontinuing contraception.

Physicians and other health care providers should advise women who want to become pregnant to stop drinking alcohol as soon as they stop using birth control, Dr. Schuchat said.

She added that physicians should screen all adults for alcohol use, not just women, even though that is not currently standard practice. “We think it should be more common to do on a regular basis.” Dr. Schuchat said the federal government requires most health plans to cover alcohol screening without cost to the patient.

The CDC recommends that physicians:

• Screen all adult female patients for alcohol use annually.

• Advise women to cease all alcohol intake if there is any chance at all that she could be pregnant.

• Counsel, refer, and follow-up with patients who need additional support to not drink while pregnant.

• Use correct billing codes to be reimbursed for screening and counseling.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which recommends that women completely abstain from alcohol during pregnancy, praised the CDC’s guidance that physicians routinely screen women regarding their alcohol use.

Dr. Mark S. DeFrancesco, ACOG president, said the other important message from the CDC report is that physicians should counsel women about contraception use.

“As the CDC notes, roughly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended. In many cases of unintended pregnancy, women inadvertently expose their fetuses to alcohol and its teratogenic effects prior to discovering that they are pregnant,” he said in statement. “This is just another reason why it’s so important that health care providers counsel women about how to prevent unintended pregnancy through use of the contraceptive method that is right for them. There are many benefits to helping women become pregnant only when they are ready, and avoiding alcohol exposure is one of them.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM THE MMWR

Key clinical point: The CDC advises physicians to screen women for alcohol use and provide contraception counseling.

Major finding: A total of 3.3 million women aged 15-44 years risk conceiving a child with FASD by using alcohol and having unprotected sex.

Data source: Data on 4,303 nonpregnant, nonsterile women aged 15-44 years from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Family Growth.

Disclosures: The researchers did not report having any financial disclosures.

CDC expands Zika virus travel warnings again

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have added four more destinations to their Zika virus travel alert – American Samoa, Costa Rica, Curacao, and Nicaragua.

The Level 2 travel alert means that individuals are urged to take enhanced precautions against mosquito bites while in these regions to minimize their chances of contracting the Zika virus. Pregnant women are being advised to consider postponing travel to areas where Zika virus transmission in ongoing. Pregnant women and those trying to become pregnant who must travel to these areas are advised to consult with their physician before traveling and take steps to prevent mosquito bites.

The CDC has already issued a Level 2 travel alert for these areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing: Puerto Rico, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Dominican Republic.

An up-to-date list of affected countries and regions is available at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html.

On Twitter @maryelleny

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have added four more destinations to their Zika virus travel alert – American Samoa, Costa Rica, Curacao, and Nicaragua.

The Level 2 travel alert means that individuals are urged to take enhanced precautions against mosquito bites while in these regions to minimize their chances of contracting the Zika virus. Pregnant women are being advised to consider postponing travel to areas where Zika virus transmission in ongoing. Pregnant women and those trying to become pregnant who must travel to these areas are advised to consult with their physician before traveling and take steps to prevent mosquito bites.

The CDC has already issued a Level 2 travel alert for these areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing: Puerto Rico, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Dominican Republic.

An up-to-date list of affected countries and regions is available at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html.

On Twitter @maryelleny

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have added four more destinations to their Zika virus travel alert – American Samoa, Costa Rica, Curacao, and Nicaragua.

The Level 2 travel alert means that individuals are urged to take enhanced precautions against mosquito bites while in these regions to minimize their chances of contracting the Zika virus. Pregnant women are being advised to consider postponing travel to areas where Zika virus transmission in ongoing. Pregnant women and those trying to become pregnant who must travel to these areas are advised to consult with their physician before traveling and take steps to prevent mosquito bites.

The CDC has already issued a Level 2 travel alert for these areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing: Puerto Rico, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Dominican Republic.

An up-to-date list of affected countries and regions is available at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html.

On Twitter @maryelleny

WHO Declares "Public Health Emergency" for Microcephaly Linked to Zika Virus

The World Health Organization has declared a “public health emergency of international concern” related to the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological complications reported in Brazil and earlier in French Polynesia.

Though there is a strong association between these cases and the Zika virus, a causal link still has not been scientifically proven, according to the WHO.

The WHO’s emergency declaration clears the way for the international health community to move forward with a coordinated response. Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said her organization plans to take a number of precautionary measures, including improving surveillance and detection of infections, congenital malformations, and neurological complications. They will also work with countries to intensify control of mosquito populations and help expedite the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines to protect at-risk populations.

The recommendations came after a Feb. 1 meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which Dr. Chan convened last week in response to the Zika virus outbreak and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

The group of 18 experts advised that the clusters of microcephaly and other complications constitute an “extraordinary event and a public health threat to other parts of the world.” The group did not recommend any restrictions on travel or trade with areas where the Zika virus transmission is ongoing, however.

“At present, the most important protective measures are the control of mosquito populations and the prevention of mosquito bites in at-risk individuals, especially pregnant women,” Dr. Chan said during a press briefing.

Dr. Chan said it’s unclear how long it will take to determine if Zika virus is causing the uptick in microcephaly and other congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities, but health officials are working to set up case-control studies that are scheduled to start in the next 2 weeks.

The World Health Organization has declared a “public health emergency of international concern” related to the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological complications reported in Brazil and earlier in French Polynesia.

Though there is a strong association between these cases and the Zika virus, a causal link still has not been scientifically proven, according to the WHO.

The WHO’s emergency declaration clears the way for the international health community to move forward with a coordinated response. Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said her organization plans to take a number of precautionary measures, including improving surveillance and detection of infections, congenital malformations, and neurological complications. They will also work with countries to intensify control of mosquito populations and help expedite the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines to protect at-risk populations.

The recommendations came after a Feb. 1 meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which Dr. Chan convened last week in response to the Zika virus outbreak and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

The group of 18 experts advised that the clusters of microcephaly and other complications constitute an “extraordinary event and a public health threat to other parts of the world.” The group did not recommend any restrictions on travel or trade with areas where the Zika virus transmission is ongoing, however.

“At present, the most important protective measures are the control of mosquito populations and the prevention of mosquito bites in at-risk individuals, especially pregnant women,” Dr. Chan said during a press briefing.

Dr. Chan said it’s unclear how long it will take to determine if Zika virus is causing the uptick in microcephaly and other congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities, but health officials are working to set up case-control studies that are scheduled to start in the next 2 weeks.

The World Health Organization has declared a “public health emergency of international concern” related to the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological complications reported in Brazil and earlier in French Polynesia.

Though there is a strong association between these cases and the Zika virus, a causal link still has not been scientifically proven, according to the WHO.

The WHO’s emergency declaration clears the way for the international health community to move forward with a coordinated response. Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said her organization plans to take a number of precautionary measures, including improving surveillance and detection of infections, congenital malformations, and neurological complications. They will also work with countries to intensify control of mosquito populations and help expedite the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines to protect at-risk populations.

The recommendations came after a Feb. 1 meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which Dr. Chan convened last week in response to the Zika virus outbreak and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

The group of 18 experts advised that the clusters of microcephaly and other complications constitute an “extraordinary event and a public health threat to other parts of the world.” The group did not recommend any restrictions on travel or trade with areas where the Zika virus transmission is ongoing, however.

“At present, the most important protective measures are the control of mosquito populations and the prevention of mosquito bites in at-risk individuals, especially pregnant women,” Dr. Chan said during a press briefing.

Dr. Chan said it’s unclear how long it will take to determine if Zika virus is causing the uptick in microcephaly and other congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities, but health officials are working to set up case-control studies that are scheduled to start in the next 2 weeks.

WHO declares ‘public health emergency’ for microcephaly linked to Zika virus

The World Health Organization has declared a “public health emergency of international concern” related to the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological complications reported in Brazil and earlier in French Polynesia.

Though there is a strong association between these cases and the Zika virus, a causal link still has not been scientifically proven, according to the WHO.

The WHO’s emergency declaration clears the way for the international health community to move forward with a coordinated response. Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said her organization plans to take a number of precautionary measures, including improving surveillance and detection of infections, congenital malformations, and neurological complications. They will also work with countries to intensify control of mosquito populations and help expedite the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines to protect at-risk populations.

The recommendations came after a Feb. 1 meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which Dr. Chan convened last week in response to the Zika virus outbreak and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

The group of 18 experts advised that the clusters of microcephaly and other complications constitute an “extraordinary event and a public health threat to other parts of the world.” The group did not recommend any restrictions on travel or trade with areas where the Zika virus transmission is ongoing, however.

“At present, the most important protective measures are the control of mosquito populations and the prevention of mosquito bites in at-risk individuals, especially pregnant women,” Dr. Chan said during a press briefing.

Dr. Chan said it’s unclear how long it will take to determine if Zika virus is causing the uptick in microcephaly and other congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities, but health officials are working to set up case-control studies that are scheduled to start in the next 2 weeks.

On Twitter @maryellenny

The World Health Organization has declared a “public health emergency of international concern” related to the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological complications reported in Brazil and earlier in French Polynesia.

Though there is a strong association between these cases and the Zika virus, a causal link still has not been scientifically proven, according to the WHO.

The WHO’s emergency declaration clears the way for the international health community to move forward with a coordinated response. Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said her organization plans to take a number of precautionary measures, including improving surveillance and detection of infections, congenital malformations, and neurological complications. They will also work with countries to intensify control of mosquito populations and help expedite the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines to protect at-risk populations.

The recommendations came after a Feb. 1 meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which Dr. Chan convened last week in response to the Zika virus outbreak and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

The group of 18 experts advised that the clusters of microcephaly and other complications constitute an “extraordinary event and a public health threat to other parts of the world.” The group did not recommend any restrictions on travel or trade with areas where the Zika virus transmission is ongoing, however.

“At present, the most important protective measures are the control of mosquito populations and the prevention of mosquito bites in at-risk individuals, especially pregnant women,” Dr. Chan said during a press briefing.

Dr. Chan said it’s unclear how long it will take to determine if Zika virus is causing the uptick in microcephaly and other congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities, but health officials are working to set up case-control studies that are scheduled to start in the next 2 weeks.

On Twitter @maryellenny

The World Health Organization has declared a “public health emergency of international concern” related to the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological complications reported in Brazil and earlier in French Polynesia.

Though there is a strong association between these cases and the Zika virus, a causal link still has not been scientifically proven, according to the WHO.

The WHO’s emergency declaration clears the way for the international health community to move forward with a coordinated response. Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said her organization plans to take a number of precautionary measures, including improving surveillance and detection of infections, congenital malformations, and neurological complications. They will also work with countries to intensify control of mosquito populations and help expedite the development of diagnostic tests and vaccines to protect at-risk populations.

The recommendations came after a Feb. 1 meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which Dr. Chan convened last week in response to the Zika virus outbreak and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

The group of 18 experts advised that the clusters of microcephaly and other complications constitute an “extraordinary event and a public health threat to other parts of the world.” The group did not recommend any restrictions on travel or trade with areas where the Zika virus transmission is ongoing, however.

“At present, the most important protective measures are the control of mosquito populations and the prevention of mosquito bites in at-risk individuals, especially pregnant women,” Dr. Chan said during a press briefing.

Dr. Chan said it’s unclear how long it will take to determine if Zika virus is causing the uptick in microcephaly and other congenital malformations and neurological abnormalities, but health officials are working to set up case-control studies that are scheduled to start in the next 2 weeks.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Managing Diabetes in Women of Childbearing Age

There were 13.4 million women (ages 20 and older) with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2012, according to the CDC.1 By 2050, overall prevalence of diabetes is expected to double or triple.2 Since the number of women with diabetes will continue to increase, it is important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with management of the condition in those of childbearing age—particularly with regard to medication selection.

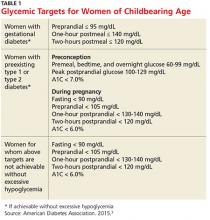

Diabetes management in women of childbearing age presents multiple complexities. First, strict glucose control from preconception through pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk for complications in mother and fetus. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends an A1C of less than 7% during the preconception period, if achievable without hypoglycemia.3 Full glycemic targets for women are outlined in Table 1.

Continue for medication classes with pregnancy category >>

Second, many medications used to manage diabetes and pregnancy-associated comorbidities can be fetotoxic. The FDA assigns all drugs to a pregnancy category, the definitions of which are available at http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm.4 The ADA recommends that sexually active women of childbearing age avoid any potentially teratogenic medications (see Table 2) if they are not using reliable contraception.3

Excellent control of diabetes is necessary to decrease risk for birth defects. Infants born to mothers with preconception diabetes have been shown to have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.5 Infants born to women with diabetes are generally large for gestational age and experience hypoglycemia in the first 24 to 48 hours of life.6 Large-for-gestational-age babies are at increased risk for trauma at birth, including orthopedic injuries (eg, shoulder dislocation) and brachial plexus injuries. There is also an increased risk for fetal cardiac defects and congenital congestive heart failure.6

This article will review four cases of diabetes management in women of childbearing age. The ADA guidelines form the basis for all recommendations.

Continue for case 1 >>

Case 1 A 32-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents for routine follow-up. Recent lab results reveal an A1C of 6.4%; GFR > 100 mL/min/1.73 m2; and microalbuminuria (110 mg/d). She is currently taking lisinopril (2.5 mg once daily), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glyburide (5 mg bid). She plans to become pregnant in the next six months and wants advice.

Discussion

This patient should be counseled on preconception glycemic targets and switched to pregnancy-safe medications. She should also be advised that the recommended weight gain in pregnancy for women with T2DM is 15 to 25 lb in overweight women and 10 to 20 lb in obese women.3

The ADA recommends a target A1C < 7%, in the absence of severe hypoglycemia, prior to conception in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or T2DM.3 For women with preconception diabetes who become pregnant, it is recommended that their premeal, bedtime, and overnight glucose be maintained at 60 to 99 mg/dL, their peak postprandial glucose at 100 to 129 mg/dL, and their A1C < 6% during pregnancy (all without excessive hypoglycemia), due to increases in red blood cell turnover.3 It is also recommended that they avoid statins, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), certain beta blockers, and most noninsulin therapies.3

This patient is currently taking lisinopril, a medication with a pregnancy category of X. The ACE inhibitor class of medications is known to cause oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, structural malformation, premature birth, fetal renal dysplasia, and other congenital abnormalities, and use of these drugs should be avoided in women trying to conceive.7

Safer options for blood pressure control include clonidine, diltiazam, labetalol, methyldopa, or prazosin.3 Diuretics can reduce placental blood perfusion and should be avoided.8 An alternative for management of microalbuminuria in women of childbearing age is nifedipine.9 In multiple studies, this medication was not only safer in pregnancy, with no major teratogenic risk, but also effectively reduced urine microalbumin levels.10,11

For T2DM management, metformin (pregnancy category B) and glyburide (pregnancy category B/C, depending on manufacturer) can be used.12,13 Glyburide, the most studied sulfonylurea, is recommended as the drug of choice in its class.14-16 While insulin is the standard for managing diabetes in pregnancy—earlier research supported a switch from oral medications to insulin in women interested in becoming pregnant—recent studies have demonstrated that oral medications can be safely used.17 In addition, lifestyle changes (eg, carbohydrate counting, limited meal portions, and regular moderate exercise) prior to and during pregnancy can be beneficial for diabetes management.18,19

Also remind the patient to take regular prenatal vitamins. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all women planning to become or capable of becoming pregnant take 400 to 800 µg supplements of folic acid daily.20 For women at high risk for neural tube defects or who have had a previous pregnancy with neural tube defects, 4 mg/d is recommended.21 In women with diabetes who are trying to conceive, a folic acid supplement of 5 mg/d is recommended, beginning three months prior to conception.22

Research shows that diabetic women are less likely to take folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. A study of 6,835 obese or overweight women with diabetes showed that only 35% reported daily folic acid supplementation.23 The study authors recommended all women of childbearing age, especially those who are obese or have diabetes, take folic acid daily.23 Encourage all women intending to become pregnant to start prenatal vitamin supplementation.

Continue for case 2 >>

Case 2 A 26-year-old obese patient, 28 weeks primigravida, presents for follow-up on her 3-hour glucose tolerance test. Results indicate a 3-hour glucose level of 148 mg/dL. The patient has a family history of T2DM and gestational diabetes.

Discussion

Gestational diabetes is defined by the ADA as diabetes diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not T1DM or T2DM.3 The ADA recommends lifestyle management of gestational diabetes before medications are introduced. A1C should be maintained at 6% or less without hypoglycemia. In general, insulin is preferred over oral agents for treatment of gestational diabetes.3

There tends to be a spike in insulin resistance in the second or third trimester; women with preconception diabetes, for example, may require frequent increases in daily insulin dose to maintain glycemic levels, compared to the first trimester.3 A baseline ophthalmology exam should be performed in the first trimester for patients with preconception diabetes, with additional monitoring as needed.3

Following pregnancy, screening should be conducted for diabetes or prediabetes at six to 12 weeks’ postpartum and every one to three years afterward.3 The cumulative incidence of T2DM varies considerably among studies, ranging from 17% to 63% in five to 16 years postpartum.24,25 Thus, women with gestational diabetes should maintain lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, to reduce the risk for T2DM later in life.

Continue for case 3 >>

Case 3 A 43-year-old woman with T1DM becomes pregnant while taking atorvastatin (20 mg), insulin detemir (18 units qhs), and insulin aspart with meals, as per her calculated insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR; 1 U aspart for 18 g carbohydrates) and insulin sensitivity factor (ISF; 1 U aspart for every 60 mg/dL above 130 mg/dL). Her biggest concern today is her medication list and potential adverse effects on the fetus. Her most recent A1C, two months ago, was 6.5%. She senses hypoglycemia at glucose levels of about 60 mg/dL and admits to having such measurements about twice per week.

Discussion

In this case, the patient needs to stop taking her statin and check her blood glucose regularly, as she is at increased risk for hypoglycemia. In their 2013 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stated that statins “should not be used in women of childbearing potential unless these women are using effective contraception and are not nursing.”26 This presents a major problem for many women of childbearing age with diabetes.

Statins are associated with a variety of congenital abnormalities, including fetal growth restriction and structural abnormalities in the fetus.27 It is advised that women planning for pregnancy avoid use of statins.28 If the patient has severe hypertriglyceridemia that puts her at risk for acute pancreatitis, fenofibrate (pregnancy category C) can be considered in the second and third trimesters.29,30

With T1DM in pregnancy, there is an increased risk for hypoglycemia in the first trimester.3 This risk increases as women adapt to more strict blood glucose control. Frequent recalculation of the ICR and ISF may be needed as the pregnancy progresses and weight gain occurs. Most insulin formulations are pregnancy class B, with the exception of glargine, degludec, and glulisine, which are pregnancy category C.3

Continue for case 4 >>

Case 4 A 21-year-old woman with T1DM wishes to start contraception but has concerns about long-term options. She seeks your advice in making a decision.

Discussion

For long-term pregnancy prevention, either the copper or progesterone-containing intrauterine device (IUD) is safe and effective for women with T1DM or T2DM.31 While the levonorgestrel IUD does not produce metabolic changes in T1DM, it has not yet been adequately studied in T2DM. Demographics suggest that young women with T2DM could become viable candidates for intrauterine contraception.31

The hormone-releasing “ring” has been found to be reliable and safe for women of late reproductive age with T1DM.32 Combined hormonal contraceptives and the transdermal contraceptive patch are best avoided to reduce risk for complications associated with estrogen-containing contraceptives (eg, venous thromboembolism and myocardial infarction).33

Continue for the conclusion >>

Conclusion

All women with diabetes should be counseled on glucose control prior to pregnancy. Achieving a goal A1C below 6% in the absence of hypoglycemia is recommended by the ADA.3 Long-term contraception options should be considered in women of childbearing age with diabetes to prevent pregnancy. Clinicians should carefully select medications for management of diabetes and its comorbidities in women planning to become pregnant. Healthy dietary habits and regular exercise should be encouraged in all patients with diabetes, especially prior to pregnancy.

References

1. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

2. CDC. Number of Americans with diabetes projected to double or triple by 2050. 2010. www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/r101022.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S1-S93.

4. Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management. FDA pregnancy categories. http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

5. Weindling AM. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: short-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(2):111-118.

6. Kaneshiro NK. Infant of diabetic mother (2013). Medline Plus. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001597.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

7. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, Elkayam U. Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):451-456.

8. Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1996;335 (4):257-265.

9. Ismail AA, Medhat I, Tawfic TA, Kholeif A. Evaluation of calcium-antagonists (nifedipine) in the treatment of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;40:39-43.

10. Magee LA, Schick B, Donnenfeld AE, et al. The safety of calcium channel blockers in human pregnancy: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(3):823-828.

11. Kattah AG, Garovic VD. The management of hypertension in pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(3):229-239.

12. Carroll DG, Kelley KW. Review of metformin and glyburide in the management of gestational diabetes. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):528.

13. Koren G. Glyburide and fetal safety; transplacental pharmacokinetic considerations. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15(3):227-229.

14. Elliott BD, Langer O, Schenker S, Johnson RF. Insignificant transfer of glyburide occurs across the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:807-812.

15. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S209-S213.

16. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

17. Kalra B, Gupta Y, Singla R, Kalra S. Use of oral anti-diabetic agents in pregnancy: a pragmatic approach. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7(1):6-12.

18. Zhang C, Ning Y. Effect of dietary and lifestyle factors on the risk of gestational diabetes: review of epidemiologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 suppl):1975S-1979S.

19. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S251-S260.

20. US Preventive Services Task Force. Folic acid to prevent neural tube defects: preventive medication, 2015. www.uspreventiveservices taskforce.org/Page/Document/Update SummaryFinal/folic-acid-to-prevent-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed January 12, 2016.

21. Cheschier N; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin no 44. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(1):123-133.

22. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4227-4249.

23. Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, et al. Folic acid supplementation among diabetic, overweight, or obese women of childbearing age. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(4):335-341.

24. Hanna FWF, Peters JR. Screening for gestational diabetes; past, present and future. Diabet Med. 2002;19:351-358.

25. Ben-haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21(2):103-113.

26. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

27. Patel C, Edgerton L, Flake D. What precautions should we use with statins for women of childbearing age? J Fam Pract. 2006; 55(1):75-77.

28. Kazmin A, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Risks of statin use during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(11):906-908.

29. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

30. Saadi HF, Kurlander DJ, Erkins JM, Hoogwerf BJ. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis during pregnancy: treatment with gemfibrozil. Endocr Pract. 1999;5(1):33-36.

31. Goldstuck ND, Steyn PS. The intrauterine device in women with diabetes mellitus type I and II: a systematic review. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:814062.

32. Grigoryan OR, Grodnitskaya EE, Andreeva EN, et al. Use of the NuvaRing hormone-releasing system in late reproductive-age women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(2):99-104.

33. Bonnema RA, McNamara MC, Spencer AL. Contraception choices in women with underlying medical conditions. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(6):621-628.

There were 13.4 million women (ages 20 and older) with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2012, according to the CDC.1 By 2050, overall prevalence of diabetes is expected to double or triple.2 Since the number of women with diabetes will continue to increase, it is important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with management of the condition in those of childbearing age—particularly with regard to medication selection.

Diabetes management in women of childbearing age presents multiple complexities. First, strict glucose control from preconception through pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk for complications in mother and fetus. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends an A1C of less than 7% during the preconception period, if achievable without hypoglycemia.3 Full glycemic targets for women are outlined in Table 1.

Continue for medication classes with pregnancy category >>

Second, many medications used to manage diabetes and pregnancy-associated comorbidities can be fetotoxic. The FDA assigns all drugs to a pregnancy category, the definitions of which are available at http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm.4 The ADA recommends that sexually active women of childbearing age avoid any potentially teratogenic medications (see Table 2) if they are not using reliable contraception.3

Excellent control of diabetes is necessary to decrease risk for birth defects. Infants born to mothers with preconception diabetes have been shown to have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.5 Infants born to women with diabetes are generally large for gestational age and experience hypoglycemia in the first 24 to 48 hours of life.6 Large-for-gestational-age babies are at increased risk for trauma at birth, including orthopedic injuries (eg, shoulder dislocation) and brachial plexus injuries. There is also an increased risk for fetal cardiac defects and congenital congestive heart failure.6

This article will review four cases of diabetes management in women of childbearing age. The ADA guidelines form the basis for all recommendations.

Continue for case 1 >>

Case 1 A 32-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents for routine follow-up. Recent lab results reveal an A1C of 6.4%; GFR > 100 mL/min/1.73 m2; and microalbuminuria (110 mg/d). She is currently taking lisinopril (2.5 mg once daily), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glyburide (5 mg bid). She plans to become pregnant in the next six months and wants advice.

Discussion

This patient should be counseled on preconception glycemic targets and switched to pregnancy-safe medications. She should also be advised that the recommended weight gain in pregnancy for women with T2DM is 15 to 25 lb in overweight women and 10 to 20 lb in obese women.3

The ADA recommends a target A1C < 7%, in the absence of severe hypoglycemia, prior to conception in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or T2DM.3 For women with preconception diabetes who become pregnant, it is recommended that their premeal, bedtime, and overnight glucose be maintained at 60 to 99 mg/dL, their peak postprandial glucose at 100 to 129 mg/dL, and their A1C < 6% during pregnancy (all without excessive hypoglycemia), due to increases in red blood cell turnover.3 It is also recommended that they avoid statins, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), certain beta blockers, and most noninsulin therapies.3

This patient is currently taking lisinopril, a medication with a pregnancy category of X. The ACE inhibitor class of medications is known to cause oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, structural malformation, premature birth, fetal renal dysplasia, and other congenital abnormalities, and use of these drugs should be avoided in women trying to conceive.7

Safer options for blood pressure control include clonidine, diltiazam, labetalol, methyldopa, or prazosin.3 Diuretics can reduce placental blood perfusion and should be avoided.8 An alternative for management of microalbuminuria in women of childbearing age is nifedipine.9 In multiple studies, this medication was not only safer in pregnancy, with no major teratogenic risk, but also effectively reduced urine microalbumin levels.10,11

For T2DM management, metformin (pregnancy category B) and glyburide (pregnancy category B/C, depending on manufacturer) can be used.12,13 Glyburide, the most studied sulfonylurea, is recommended as the drug of choice in its class.14-16 While insulin is the standard for managing diabetes in pregnancy—earlier research supported a switch from oral medications to insulin in women interested in becoming pregnant—recent studies have demonstrated that oral medications can be safely used.17 In addition, lifestyle changes (eg, carbohydrate counting, limited meal portions, and regular moderate exercise) prior to and during pregnancy can be beneficial for diabetes management.18,19

Also remind the patient to take regular prenatal vitamins. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all women planning to become or capable of becoming pregnant take 400 to 800 µg supplements of folic acid daily.20 For women at high risk for neural tube defects or who have had a previous pregnancy with neural tube defects, 4 mg/d is recommended.21 In women with diabetes who are trying to conceive, a folic acid supplement of 5 mg/d is recommended, beginning three months prior to conception.22

Research shows that diabetic women are less likely to take folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. A study of 6,835 obese or overweight women with diabetes showed that only 35% reported daily folic acid supplementation.23 The study authors recommended all women of childbearing age, especially those who are obese or have diabetes, take folic acid daily.23 Encourage all women intending to become pregnant to start prenatal vitamin supplementation.

Continue for case 2 >>

Case 2 A 26-year-old obese patient, 28 weeks primigravida, presents for follow-up on her 3-hour glucose tolerance test. Results indicate a 3-hour glucose level of 148 mg/dL. The patient has a family history of T2DM and gestational diabetes.

Discussion

Gestational diabetes is defined by the ADA as diabetes diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not T1DM or T2DM.3 The ADA recommends lifestyle management of gestational diabetes before medications are introduced. A1C should be maintained at 6% or less without hypoglycemia. In general, insulin is preferred over oral agents for treatment of gestational diabetes.3

There tends to be a spike in insulin resistance in the second or third trimester; women with preconception diabetes, for example, may require frequent increases in daily insulin dose to maintain glycemic levels, compared to the first trimester.3 A baseline ophthalmology exam should be performed in the first trimester for patients with preconception diabetes, with additional monitoring as needed.3

Following pregnancy, screening should be conducted for diabetes or prediabetes at six to 12 weeks’ postpartum and every one to three years afterward.3 The cumulative incidence of T2DM varies considerably among studies, ranging from 17% to 63% in five to 16 years postpartum.24,25 Thus, women with gestational diabetes should maintain lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, to reduce the risk for T2DM later in life.

Continue for case 3 >>

Case 3 A 43-year-old woman with T1DM becomes pregnant while taking atorvastatin (20 mg), insulin detemir (18 units qhs), and insulin aspart with meals, as per her calculated insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR; 1 U aspart for 18 g carbohydrates) and insulin sensitivity factor (ISF; 1 U aspart for every 60 mg/dL above 130 mg/dL). Her biggest concern today is her medication list and potential adverse effects on the fetus. Her most recent A1C, two months ago, was 6.5%. She senses hypoglycemia at glucose levels of about 60 mg/dL and admits to having such measurements about twice per week.

Discussion

In this case, the patient needs to stop taking her statin and check her blood glucose regularly, as she is at increased risk for hypoglycemia. In their 2013 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stated that statins “should not be used in women of childbearing potential unless these women are using effective contraception and are not nursing.”26 This presents a major problem for many women of childbearing age with diabetes.

Statins are associated with a variety of congenital abnormalities, including fetal growth restriction and structural abnormalities in the fetus.27 It is advised that women planning for pregnancy avoid use of statins.28 If the patient has severe hypertriglyceridemia that puts her at risk for acute pancreatitis, fenofibrate (pregnancy category C) can be considered in the second and third trimesters.29,30

With T1DM in pregnancy, there is an increased risk for hypoglycemia in the first trimester.3 This risk increases as women adapt to more strict blood glucose control. Frequent recalculation of the ICR and ISF may be needed as the pregnancy progresses and weight gain occurs. Most insulin formulations are pregnancy class B, with the exception of glargine, degludec, and glulisine, which are pregnancy category C.3

Continue for case 4 >>

Case 4 A 21-year-old woman with T1DM wishes to start contraception but has concerns about long-term options. She seeks your advice in making a decision.

Discussion

For long-term pregnancy prevention, either the copper or progesterone-containing intrauterine device (IUD) is safe and effective for women with T1DM or T2DM.31 While the levonorgestrel IUD does not produce metabolic changes in T1DM, it has not yet been adequately studied in T2DM. Demographics suggest that young women with T2DM could become viable candidates for intrauterine contraception.31

The hormone-releasing “ring” has been found to be reliable and safe for women of late reproductive age with T1DM.32 Combined hormonal contraceptives and the transdermal contraceptive patch are best avoided to reduce risk for complications associated with estrogen-containing contraceptives (eg, venous thromboembolism and myocardial infarction).33

Continue for the conclusion >>

Conclusion

All women with diabetes should be counseled on glucose control prior to pregnancy. Achieving a goal A1C below 6% in the absence of hypoglycemia is recommended by the ADA.3 Long-term contraception options should be considered in women of childbearing age with diabetes to prevent pregnancy. Clinicians should carefully select medications for management of diabetes and its comorbidities in women planning to become pregnant. Healthy dietary habits and regular exercise should be encouraged in all patients with diabetes, especially prior to pregnancy.

References

1. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

2. CDC. Number of Americans with diabetes projected to double or triple by 2050. 2010. www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/r101022.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S1-S93.

4. Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management. FDA pregnancy categories. http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

5. Weindling AM. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: short-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(2):111-118.

6. Kaneshiro NK. Infant of diabetic mother (2013). Medline Plus. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001597.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

7. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, Elkayam U. Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):451-456.

8. Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1996;335 (4):257-265.

9. Ismail AA, Medhat I, Tawfic TA, Kholeif A. Evaluation of calcium-antagonists (nifedipine) in the treatment of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;40:39-43.

10. Magee LA, Schick B, Donnenfeld AE, et al. The safety of calcium channel blockers in human pregnancy: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(3):823-828.

11. Kattah AG, Garovic VD. The management of hypertension in pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(3):229-239.

12. Carroll DG, Kelley KW. Review of metformin and glyburide in the management of gestational diabetes. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):528.

13. Koren G. Glyburide and fetal safety; transplacental pharmacokinetic considerations. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15(3):227-229.

14. Elliott BD, Langer O, Schenker S, Johnson RF. Insignificant transfer of glyburide occurs across the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:807-812.

15. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S209-S213.

16. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

17. Kalra B, Gupta Y, Singla R, Kalra S. Use of oral anti-diabetic agents in pregnancy: a pragmatic approach. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7(1):6-12.

18. Zhang C, Ning Y. Effect of dietary and lifestyle factors on the risk of gestational diabetes: review of epidemiologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 suppl):1975S-1979S.

19. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S251-S260.

20. US Preventive Services Task Force. Folic acid to prevent neural tube defects: preventive medication, 2015. www.uspreventiveservices taskforce.org/Page/Document/Update SummaryFinal/folic-acid-to-prevent-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed January 12, 2016.

21. Cheschier N; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin no 44. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(1):123-133.

22. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4227-4249.

23. Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, et al. Folic acid supplementation among diabetic, overweight, or obese women of childbearing age. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(4):335-341.

24. Hanna FWF, Peters JR. Screening for gestational diabetes; past, present and future. Diabet Med. 2002;19:351-358.

25. Ben-haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21(2):103-113.

26. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

27. Patel C, Edgerton L, Flake D. What precautions should we use with statins for women of childbearing age? J Fam Pract. 2006; 55(1):75-77.

28. Kazmin A, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Risks of statin use during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(11):906-908.

29. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

30. Saadi HF, Kurlander DJ, Erkins JM, Hoogwerf BJ. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis during pregnancy: treatment with gemfibrozil. Endocr Pract. 1999;5(1):33-36.

31. Goldstuck ND, Steyn PS. The intrauterine device in women with diabetes mellitus type I and II: a systematic review. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:814062.

32. Grigoryan OR, Grodnitskaya EE, Andreeva EN, et al. Use of the NuvaRing hormone-releasing system in late reproductive-age women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(2):99-104.

33. Bonnema RA, McNamara MC, Spencer AL. Contraception choices in women with underlying medical conditions. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(6):621-628.

There were 13.4 million women (ages 20 and older) with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2012, according to the CDC.1 By 2050, overall prevalence of diabetes is expected to double or triple.2 Since the number of women with diabetes will continue to increase, it is important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with management of the condition in those of childbearing age—particularly with regard to medication selection.

Diabetes management in women of childbearing age presents multiple complexities. First, strict glucose control from preconception through pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk for complications in mother and fetus. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends an A1C of less than 7% during the preconception period, if achievable without hypoglycemia.3 Full glycemic targets for women are outlined in Table 1.

Continue for medication classes with pregnancy category >>