User login

Supreme Court reprieve lets 10 Texas abortion clinics stay open for now

June 30 would have been the last day of operation for 10 Texas clinics that provide abortion. But on June 29 the U.S. Supreme Court, in one of its final actions this session, said the clinics can remain open while clinic lawyers ask the court for a full review of a strict abortion law.

Two dozen states have passed regulations similar to the ones being fought over in Texas.

Two years ago, when Texas passed one of the toughest laws in the country regarding abortion, the number of clinics offering the procedure dropped from 41 to 19. Amy Hagstrom Miller, chief executive of Whole Woman’s Health, has already closed two clinics in Texas because of the law and was about to close two more.

“Honestly I just can’t stop smiling,” Ms. Hagstrom Miller said. “It’s been so much up and down … so much uncertainty for my team and the women that we serve.”

The Texas law says doctors who perform abortions must have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. But some hospitals are reluctant to grant those privileges because of religious reasons or because abortion is so controversial.

The law also requires that clinics meet the same standards as outpatient surgery centers. Those upgrades can cost $1 million or more.

“It’s an example of the rash of laws … that have taken a sneaky approach by enacting regulations that pretend to be about health and safety but are actually designed to close down clinics,” said Nancy Northrup, chief executive of the Center for Reproductive Rights, which is representing clinics in their fight to overturn the Texas law.

Supporters of the law said every woman deserves good medical care whatever the procedure.

“While we hope that she would not be compelled to choose abortion, we hope that her life would of course not be at risk should she choose to do that,” said Emily Horne of Texas Right to Life. “Pro-life does not just mean care for the life of the unborn child; it’s care for the life of the woman undergoing the abortion as well.”

The law has had a drastic effect in Texas, the country’s second most populous state, leaving most of the remaining clinics in major cities.

There’s just one clinic left along the Mexican border and one in far west El Paso – they were among the nine about to shut down.

If they had closed, the women there faced round-trips of 300 miles or more to get an abortion.

Ms. Hagstrom Miller said all these clinic rules and the doctor restrictions are a deliberate strategy waged by antiabortion groups. “They’re going state by state by state,” she said. “They can’t make it illegal, so they’re basically making it completely inaccessible.”

Other states that have passed similar laws are also facing legal challenges.

Ms. Horne of Texas Right to Life said her group would welcome a legal review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

“With this case, issuing some more guidance on that could be very helpful for the pro-life movement in determining what courses to pursue, which laws they might pass in other states in the future,” she said.

The clinics in Texas can stay open at least until the fall. If the court decides to take the case, it would hear arguments in its next term that starts in October.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes Houston Public Media, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a nonprofit national health policy news service.

June 30 would have been the last day of operation for 10 Texas clinics that provide abortion. But on June 29 the U.S. Supreme Court, in one of its final actions this session, said the clinics can remain open while clinic lawyers ask the court for a full review of a strict abortion law.

Two dozen states have passed regulations similar to the ones being fought over in Texas.

Two years ago, when Texas passed one of the toughest laws in the country regarding abortion, the number of clinics offering the procedure dropped from 41 to 19. Amy Hagstrom Miller, chief executive of Whole Woman’s Health, has already closed two clinics in Texas because of the law and was about to close two more.

“Honestly I just can’t stop smiling,” Ms. Hagstrom Miller said. “It’s been so much up and down … so much uncertainty for my team and the women that we serve.”

The Texas law says doctors who perform abortions must have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. But some hospitals are reluctant to grant those privileges because of religious reasons or because abortion is so controversial.

The law also requires that clinics meet the same standards as outpatient surgery centers. Those upgrades can cost $1 million or more.

“It’s an example of the rash of laws … that have taken a sneaky approach by enacting regulations that pretend to be about health and safety but are actually designed to close down clinics,” said Nancy Northrup, chief executive of the Center for Reproductive Rights, which is representing clinics in their fight to overturn the Texas law.

Supporters of the law said every woman deserves good medical care whatever the procedure.

“While we hope that she would not be compelled to choose abortion, we hope that her life would of course not be at risk should she choose to do that,” said Emily Horne of Texas Right to Life. “Pro-life does not just mean care for the life of the unborn child; it’s care for the life of the woman undergoing the abortion as well.”

The law has had a drastic effect in Texas, the country’s second most populous state, leaving most of the remaining clinics in major cities.

There’s just one clinic left along the Mexican border and one in far west El Paso – they were among the nine about to shut down.

If they had closed, the women there faced round-trips of 300 miles or more to get an abortion.

Ms. Hagstrom Miller said all these clinic rules and the doctor restrictions are a deliberate strategy waged by antiabortion groups. “They’re going state by state by state,” she said. “They can’t make it illegal, so they’re basically making it completely inaccessible.”

Other states that have passed similar laws are also facing legal challenges.

Ms. Horne of Texas Right to Life said her group would welcome a legal review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

“With this case, issuing some more guidance on that could be very helpful for the pro-life movement in determining what courses to pursue, which laws they might pass in other states in the future,” she said.

The clinics in Texas can stay open at least until the fall. If the court decides to take the case, it would hear arguments in its next term that starts in October.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes Houston Public Media, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a nonprofit national health policy news service.

June 30 would have been the last day of operation for 10 Texas clinics that provide abortion. But on June 29 the U.S. Supreme Court, in one of its final actions this session, said the clinics can remain open while clinic lawyers ask the court for a full review of a strict abortion law.

Two dozen states have passed regulations similar to the ones being fought over in Texas.

Two years ago, when Texas passed one of the toughest laws in the country regarding abortion, the number of clinics offering the procedure dropped from 41 to 19. Amy Hagstrom Miller, chief executive of Whole Woman’s Health, has already closed two clinics in Texas because of the law and was about to close two more.

“Honestly I just can’t stop smiling,” Ms. Hagstrom Miller said. “It’s been so much up and down … so much uncertainty for my team and the women that we serve.”

The Texas law says doctors who perform abortions must have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. But some hospitals are reluctant to grant those privileges because of religious reasons or because abortion is so controversial.

The law also requires that clinics meet the same standards as outpatient surgery centers. Those upgrades can cost $1 million or more.

“It’s an example of the rash of laws … that have taken a sneaky approach by enacting regulations that pretend to be about health and safety but are actually designed to close down clinics,” said Nancy Northrup, chief executive of the Center for Reproductive Rights, which is representing clinics in their fight to overturn the Texas law.

Supporters of the law said every woman deserves good medical care whatever the procedure.

“While we hope that she would not be compelled to choose abortion, we hope that her life would of course not be at risk should she choose to do that,” said Emily Horne of Texas Right to Life. “Pro-life does not just mean care for the life of the unborn child; it’s care for the life of the woman undergoing the abortion as well.”

The law has had a drastic effect in Texas, the country’s second most populous state, leaving most of the remaining clinics in major cities.

There’s just one clinic left along the Mexican border and one in far west El Paso – they were among the nine about to shut down.

If they had closed, the women there faced round-trips of 300 miles or more to get an abortion.

Ms. Hagstrom Miller said all these clinic rules and the doctor restrictions are a deliberate strategy waged by antiabortion groups. “They’re going state by state by state,” she said. “They can’t make it illegal, so they’re basically making it completely inaccessible.”

Other states that have passed similar laws are also facing legal challenges.

Ms. Horne of Texas Right to Life said her group would welcome a legal review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

“With this case, issuing some more guidance on that could be very helpful for the pro-life movement in determining what courses to pursue, which laws they might pass in other states in the future,” she said.

The clinics in Texas can stay open at least until the fall. If the court decides to take the case, it would hear arguments in its next term that starts in October.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes Houston Public Media, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a nonprofit national health policy news service.

Cuba eliminates mother-to-child transmission of HIV, syphilis

Cuba has become the first country to receive official validation from the World Health Organization that it has eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis – an achievement that officials credit to a long-standing tradition of universal health care coverage and access in the island nation.

“This historic achievement was made possible by a health system that provides equitable, integrated health services based on primary health care that include difficult and complex interventions like those required for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis,” Dr. Carissa F. Etienne, director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), WHO’s Regional Office of the Americas, said during a press briefing.

Cuba’s success demonstrates that universal access and universal health coverage are feasible and are, indeed, the key to success, even against challenges as daunting as HIV, she added.

Several other countries are also poised to request validation of the elimination of vertical HIV and syphilis transmission – defined as fewer than two cases of HIV in every 100 babies born to women with HIV and fewer than one case of syphilis for every 2,000 live births, according to Dr. Etienne.

Even some larger countries – including the United States and Canada – may have also achieved elimination of vertical transmission of HIV and syphilis, but they have not requested validation yet, she said.

The validation process is rigorous and requires a visit by an international panel of experts convened by PAHO/WHO; in Cuba, the panel spent several days visiting health centers, laboratories, and government offices, and also interviewed health officials and other key players, paying particular attention to human rights issues.

Validation requires that impact indicators (such as achieving fewer than 50 cases of new pediatric infections caused by mother-to-child transmissions per 100,000 live births and an HIV transmission rate of less than 5% in breastfeeding populations and less than 2% in non–breastfeeding populations) be met for at least a year. Additionally, process indicators, (95% of pregnant women receiving an antenatal visit, knowing their HIV status and/or being tested for syphilis, and receiving appropriate treatment) must be met for at least 2 years.

Cuba, which has been part of a regional initiative led by PAHO and WHO to eliminate vertical transmission of HIV and syphilis, achieved its goal by ensuring early access to prenatal care, HIV and syphilis testing for pregnant women and their partners, treatment for those who test positive and their babies, substitution of breastfeeding among those affected, and prevention of HIV and syphilis before and during pregnancy through promotion of condoms use and other measures.

Cuba, and any country that receives validation of elimination must maintain ongoing programs to ensure continued success.

Every year, an estimated 1.4 million women living with HIV become pregnant. If untreated, they have a 15%-45% chance of transmitting the virus to their children during pregnancy, labor, delivery, or breast-feeding. That risk drops to just over 1% if antiretroviral medicines are given to both mothers and children throughout the stages when infection can occur, according to PAHO/WHO, which noted in a press release that the number of children born annually with HIV has almost halved since 2009 – down from 400,000 to 240,000 in 2013.

However, stepped-up efforts will be needed to reach the global target of less than 40,000 new child infections per year.

“To achieve that, we need a final push to ensure that all pregnant women have access to sexual and reproductive health services that include HIV and syphilis testing and antiretroviral and penicillin treatment,” Dr. Etienne said. “Treatment is essential to save women’s lives, to clear maternal syphilis, and to reduce the chances that mothers will transmit these infections to their babies.”

Cuba has become the first country to receive official validation from the World Health Organization that it has eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis – an achievement that officials credit to a long-standing tradition of universal health care coverage and access in the island nation.

“This historic achievement was made possible by a health system that provides equitable, integrated health services based on primary health care that include difficult and complex interventions like those required for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis,” Dr. Carissa F. Etienne, director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), WHO’s Regional Office of the Americas, said during a press briefing.

Cuba’s success demonstrates that universal access and universal health coverage are feasible and are, indeed, the key to success, even against challenges as daunting as HIV, she added.

Several other countries are also poised to request validation of the elimination of vertical HIV and syphilis transmission – defined as fewer than two cases of HIV in every 100 babies born to women with HIV and fewer than one case of syphilis for every 2,000 live births, according to Dr. Etienne.

Even some larger countries – including the United States and Canada – may have also achieved elimination of vertical transmission of HIV and syphilis, but they have not requested validation yet, she said.

The validation process is rigorous and requires a visit by an international panel of experts convened by PAHO/WHO; in Cuba, the panel spent several days visiting health centers, laboratories, and government offices, and also interviewed health officials and other key players, paying particular attention to human rights issues.

Validation requires that impact indicators (such as achieving fewer than 50 cases of new pediatric infections caused by mother-to-child transmissions per 100,000 live births and an HIV transmission rate of less than 5% in breastfeeding populations and less than 2% in non–breastfeeding populations) be met for at least a year. Additionally, process indicators, (95% of pregnant women receiving an antenatal visit, knowing their HIV status and/or being tested for syphilis, and receiving appropriate treatment) must be met for at least 2 years.

Cuba, which has been part of a regional initiative led by PAHO and WHO to eliminate vertical transmission of HIV and syphilis, achieved its goal by ensuring early access to prenatal care, HIV and syphilis testing for pregnant women and their partners, treatment for those who test positive and their babies, substitution of breastfeeding among those affected, and prevention of HIV and syphilis before and during pregnancy through promotion of condoms use and other measures.

Cuba, and any country that receives validation of elimination must maintain ongoing programs to ensure continued success.

Every year, an estimated 1.4 million women living with HIV become pregnant. If untreated, they have a 15%-45% chance of transmitting the virus to their children during pregnancy, labor, delivery, or breast-feeding. That risk drops to just over 1% if antiretroviral medicines are given to both mothers and children throughout the stages when infection can occur, according to PAHO/WHO, which noted in a press release that the number of children born annually with HIV has almost halved since 2009 – down from 400,000 to 240,000 in 2013.

However, stepped-up efforts will be needed to reach the global target of less than 40,000 new child infections per year.

“To achieve that, we need a final push to ensure that all pregnant women have access to sexual and reproductive health services that include HIV and syphilis testing and antiretroviral and penicillin treatment,” Dr. Etienne said. “Treatment is essential to save women’s lives, to clear maternal syphilis, and to reduce the chances that mothers will transmit these infections to their babies.”

Cuba has become the first country to receive official validation from the World Health Organization that it has eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis – an achievement that officials credit to a long-standing tradition of universal health care coverage and access in the island nation.

“This historic achievement was made possible by a health system that provides equitable, integrated health services based on primary health care that include difficult and complex interventions like those required for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis,” Dr. Carissa F. Etienne, director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), WHO’s Regional Office of the Americas, said during a press briefing.

Cuba’s success demonstrates that universal access and universal health coverage are feasible and are, indeed, the key to success, even against challenges as daunting as HIV, she added.

Several other countries are also poised to request validation of the elimination of vertical HIV and syphilis transmission – defined as fewer than two cases of HIV in every 100 babies born to women with HIV and fewer than one case of syphilis for every 2,000 live births, according to Dr. Etienne.

Even some larger countries – including the United States and Canada – may have also achieved elimination of vertical transmission of HIV and syphilis, but they have not requested validation yet, she said.

The validation process is rigorous and requires a visit by an international panel of experts convened by PAHO/WHO; in Cuba, the panel spent several days visiting health centers, laboratories, and government offices, and also interviewed health officials and other key players, paying particular attention to human rights issues.

Validation requires that impact indicators (such as achieving fewer than 50 cases of new pediatric infections caused by mother-to-child transmissions per 100,000 live births and an HIV transmission rate of less than 5% in breastfeeding populations and less than 2% in non–breastfeeding populations) be met for at least a year. Additionally, process indicators, (95% of pregnant women receiving an antenatal visit, knowing their HIV status and/or being tested for syphilis, and receiving appropriate treatment) must be met for at least 2 years.

Cuba, which has been part of a regional initiative led by PAHO and WHO to eliminate vertical transmission of HIV and syphilis, achieved its goal by ensuring early access to prenatal care, HIV and syphilis testing for pregnant women and their partners, treatment for those who test positive and their babies, substitution of breastfeeding among those affected, and prevention of HIV and syphilis before and during pregnancy through promotion of condoms use and other measures.

Cuba, and any country that receives validation of elimination must maintain ongoing programs to ensure continued success.

Every year, an estimated 1.4 million women living with HIV become pregnant. If untreated, they have a 15%-45% chance of transmitting the virus to their children during pregnancy, labor, delivery, or breast-feeding. That risk drops to just over 1% if antiretroviral medicines are given to both mothers and children throughout the stages when infection can occur, according to PAHO/WHO, which noted in a press release that the number of children born annually with HIV has almost halved since 2009 – down from 400,000 to 240,000 in 2013.

However, stepped-up efforts will be needed to reach the global target of less than 40,000 new child infections per year.

“To achieve that, we need a final push to ensure that all pregnant women have access to sexual and reproductive health services that include HIV and syphilis testing and antiretroviral and penicillin treatment,” Dr. Etienne said. “Treatment is essential to save women’s lives, to clear maternal syphilis, and to reduce the chances that mothers will transmit these infections to their babies.”

ACOG, SMFM cautious on wider use of cell-free DNA screening

Conventional prenatal screening methods are still the gold standard for most pregnant women despite the availability of cell-free DNA screening for aneuploidy, according to a consensus statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The two organizations cited the limits of cell-free DNA screening performance and the limited data on cost effectiveness in the low-risk obstetric population for encouraging ob.gyns. to stick with conventional screening methods in the general obstetric population.

After cell-free DNA analysis became clinically available in 2011, ACOG and SMFM recommended it for women at increased risk of fetal aneuploidy, including women 35 years or older, fetuses with ultrasonographic findings indicative of an increased risk of aneuploidy, women with a history of trisomy-affected offspring, a parent carrying a balanced robertsonian translocation with an increased risk of trisomy 13 or trisomy 21, and women with positive first-trimester or second-trimester screening test results.

And in a 2012 joint committee opinion, ACOG and SMFM said that cell-free DNA testing should not be offered to low-risk women or women with multiple gestations because it hadn’t been sufficiently studied.

The updated committee opinion, outlines the pros and cons of using cell-free DNA screening in the general obstetric population.

“Patients should be counseled that cell-free DNA screening does not replace the precision obtained with diagnostic tests, such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, and therefore, is limited in its ability to identify all chromosome abnormalities,” the groups wrote in the updated opinion. “Not only can there be false-positive test results, but a positive cell-free DNA test result for aneuploidy does not determine if the trisomy is due to a translocation, which affects the risk of recurrence. If a fetal structural anomaly is identified on ultrasound examination, diagnostic testing should be offered rather than cell-free DNA screening.”

The sensitivity and specificity of the cell-free DNA screen in the general obstetric population are similar to those in high-risk patients. But the positive predictive value is lower in the general population because of the lower prevalence of aneuploidy. “That is, fewer women with a positive test result will actually have an affected fetus, and there will be more false-positive test results,” ACOG and SMFM wrote.

As a result, the revised opinion includes a recommendation specifying that management decisions, including the decision to terminate a pregnancy, should not be based on the results of cell-free DNA screening alone. Further diagnostic testing is now recommended for any patient who receives a positive result on cell-free DNA screening.

Similarly, women whose results are indeterminate, uninterpretable (“no call” result), or not reported at all should receive further genetic counseling and be offered comprehensive ultrasound evaluation and diagnostic testing. And women whose results are negative should be counseled that a negative cell-free DNA test does not ensure a normal pregnancy.

Additionally, most cell-free DNA testing identifies only trisomies 13, 18, and 21, which comprise a smaller proportion of the chromosomal anomalies found in the general obstetric population than among high-risk women. In one study cited in the opinion, up to 17% of clinically significant chromosomal abnormalities would not be detectable by most current cell-free DNA techniques.

The joint opinion now includes a recommendation against routinely using cell-free DNA screening for microdeletion syndromes. And it reminds physicians that cell-free DNA testing also doesn’t assess fetal anomalies such as neural tube defects or ventral wall defects, so patients who undergo cell-free DNA screening should still be offered maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening or ultrasound assessment. The latest opinion continues to recommend against the use of cell-free DNA testing for women with multiple gestations.

Conventional prenatal screening methods are still the gold standard for most pregnant women despite the availability of cell-free DNA screening for aneuploidy, according to a consensus statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The two organizations cited the limits of cell-free DNA screening performance and the limited data on cost effectiveness in the low-risk obstetric population for encouraging ob.gyns. to stick with conventional screening methods in the general obstetric population.

After cell-free DNA analysis became clinically available in 2011, ACOG and SMFM recommended it for women at increased risk of fetal aneuploidy, including women 35 years or older, fetuses with ultrasonographic findings indicative of an increased risk of aneuploidy, women with a history of trisomy-affected offspring, a parent carrying a balanced robertsonian translocation with an increased risk of trisomy 13 or trisomy 21, and women with positive first-trimester or second-trimester screening test results.

And in a 2012 joint committee opinion, ACOG and SMFM said that cell-free DNA testing should not be offered to low-risk women or women with multiple gestations because it hadn’t been sufficiently studied.

The updated committee opinion, outlines the pros and cons of using cell-free DNA screening in the general obstetric population.

“Patients should be counseled that cell-free DNA screening does not replace the precision obtained with diagnostic tests, such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, and therefore, is limited in its ability to identify all chromosome abnormalities,” the groups wrote in the updated opinion. “Not only can there be false-positive test results, but a positive cell-free DNA test result for aneuploidy does not determine if the trisomy is due to a translocation, which affects the risk of recurrence. If a fetal structural anomaly is identified on ultrasound examination, diagnostic testing should be offered rather than cell-free DNA screening.”

The sensitivity and specificity of the cell-free DNA screen in the general obstetric population are similar to those in high-risk patients. But the positive predictive value is lower in the general population because of the lower prevalence of aneuploidy. “That is, fewer women with a positive test result will actually have an affected fetus, and there will be more false-positive test results,” ACOG and SMFM wrote.

As a result, the revised opinion includes a recommendation specifying that management decisions, including the decision to terminate a pregnancy, should not be based on the results of cell-free DNA screening alone. Further diagnostic testing is now recommended for any patient who receives a positive result on cell-free DNA screening.

Similarly, women whose results are indeterminate, uninterpretable (“no call” result), or not reported at all should receive further genetic counseling and be offered comprehensive ultrasound evaluation and diagnostic testing. And women whose results are negative should be counseled that a negative cell-free DNA test does not ensure a normal pregnancy.

Additionally, most cell-free DNA testing identifies only trisomies 13, 18, and 21, which comprise a smaller proportion of the chromosomal anomalies found in the general obstetric population than among high-risk women. In one study cited in the opinion, up to 17% of clinically significant chromosomal abnormalities would not be detectable by most current cell-free DNA techniques.

The joint opinion now includes a recommendation against routinely using cell-free DNA screening for microdeletion syndromes. And it reminds physicians that cell-free DNA testing also doesn’t assess fetal anomalies such as neural tube defects or ventral wall defects, so patients who undergo cell-free DNA screening should still be offered maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening or ultrasound assessment. The latest opinion continues to recommend against the use of cell-free DNA testing for women with multiple gestations.

Conventional prenatal screening methods are still the gold standard for most pregnant women despite the availability of cell-free DNA screening for aneuploidy, according to a consensus statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The two organizations cited the limits of cell-free DNA screening performance and the limited data on cost effectiveness in the low-risk obstetric population for encouraging ob.gyns. to stick with conventional screening methods in the general obstetric population.

After cell-free DNA analysis became clinically available in 2011, ACOG and SMFM recommended it for women at increased risk of fetal aneuploidy, including women 35 years or older, fetuses with ultrasonographic findings indicative of an increased risk of aneuploidy, women with a history of trisomy-affected offspring, a parent carrying a balanced robertsonian translocation with an increased risk of trisomy 13 or trisomy 21, and women with positive first-trimester or second-trimester screening test results.

And in a 2012 joint committee opinion, ACOG and SMFM said that cell-free DNA testing should not be offered to low-risk women or women with multiple gestations because it hadn’t been sufficiently studied.

The updated committee opinion, outlines the pros and cons of using cell-free DNA screening in the general obstetric population.

“Patients should be counseled that cell-free DNA screening does not replace the precision obtained with diagnostic tests, such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, and therefore, is limited in its ability to identify all chromosome abnormalities,” the groups wrote in the updated opinion. “Not only can there be false-positive test results, but a positive cell-free DNA test result for aneuploidy does not determine if the trisomy is due to a translocation, which affects the risk of recurrence. If a fetal structural anomaly is identified on ultrasound examination, diagnostic testing should be offered rather than cell-free DNA screening.”

The sensitivity and specificity of the cell-free DNA screen in the general obstetric population are similar to those in high-risk patients. But the positive predictive value is lower in the general population because of the lower prevalence of aneuploidy. “That is, fewer women with a positive test result will actually have an affected fetus, and there will be more false-positive test results,” ACOG and SMFM wrote.

As a result, the revised opinion includes a recommendation specifying that management decisions, including the decision to terminate a pregnancy, should not be based on the results of cell-free DNA screening alone. Further diagnostic testing is now recommended for any patient who receives a positive result on cell-free DNA screening.

Similarly, women whose results are indeterminate, uninterpretable (“no call” result), or not reported at all should receive further genetic counseling and be offered comprehensive ultrasound evaluation and diagnostic testing. And women whose results are negative should be counseled that a negative cell-free DNA test does not ensure a normal pregnancy.

Additionally, most cell-free DNA testing identifies only trisomies 13, 18, and 21, which comprise a smaller proportion of the chromosomal anomalies found in the general obstetric population than among high-risk women. In one study cited in the opinion, up to 17% of clinically significant chromosomal abnormalities would not be detectable by most current cell-free DNA techniques.

The joint opinion now includes a recommendation against routinely using cell-free DNA screening for microdeletion syndromes. And it reminds physicians that cell-free DNA testing also doesn’t assess fetal anomalies such as neural tube defects or ventral wall defects, so patients who undergo cell-free DNA screening should still be offered maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening or ultrasound assessment. The latest opinion continues to recommend against the use of cell-free DNA testing for women with multiple gestations.

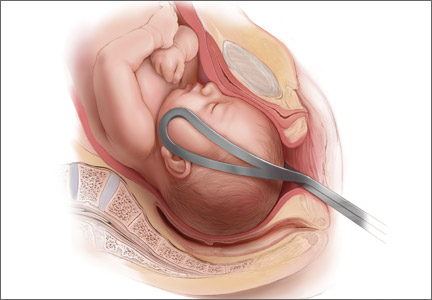

2015 Update on operative vaginal delivery

There’s a cyclical lament in obstetrics, and it goes something like this: Forceps are waning and are going to fade away completely if something isn’t done about it. This lament resounds every few decades, as a look at the literature confirms:

- 1963: “Midforceps delivery—a vanishing art?”1

- 1992: “Kielland’s forceps delivery: Is it a dying art?”2

- 2000: “Operative obstetrics: a lost art?”3

- 2015: “Forceps: towards obsolescence or revival?”4

In this, our latest cycle of lament, 4 or 5 papers have suggested that forceps in general and Kielland forceps in particular ought not be abandoned because outcomes are better than those suggested by the older literature. With the cesarean delivery rate hovering at about 31% in the United States, perhaps it is time to revisit the issue.

This Update is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the literature. Rather, it offers a snapshot of articles published within the past year—articles that highlight some new features of a very old debate:

- a nested observational study of 478 nulliparous women at term undergoing instrumental delivery, which found that instrument placement was “suboptimal” in a significant percentage of deliveries

- a retrospective study of major teaching hospitals, minor teaching facilities, and nonteaching institutions in 9 states, which found forceps delivery volumes so low they may make it difficult for clinicians to maintain their skills and prevent many trainees from acquiring proficiency

- a commentary calling for the discontinuation of forceps deliveries in light of an ultrasonographically identified injury to the pelvic floor—levator ani muscle avulsion—and a cadaveric study refuting this argument

- a systematic review and meta-analysis of maternal and neonatal morbidity following cesarean delivery in the first stage versus the second stage of labor.

Forceps and vacuum device placement is “suboptimal” in almost 30% of operative vaginal deliveries

Ramphul M, Kennelly MM, Burke G, Murphy DJ. Risk factors and morbidity associated with suboptimal instrument placement at instrumental delivery: observational study nested within the Instrumental Delivery & Ultrasound randomised controlled trial ISRCTN 72230496. BJOG. 2015;122(4):558–563.

Rouse DJ. Instrument placement is sub-optimal in three of ten attempted operative vaginal deliveries. BJOG. 2015;122(4):564.

Over the years, many clinicians have argued that we don’t do enough forceps deliveries to maintain our own competence with the procedure, let alone teach residents how to perform it. This observational study nested in a randomized clinical trial is intriguing because Ramphul and colleagues looked for objective evidence of clinicians’ skill at the vacuum and forceps. Specifically, they looked for evidence that the forceps or vacuum was malpositioned during attempts at operative vaginal delivery. In the process, they nicely documented the absolute rate of malpositioning of the forceps and vacuum, finding that it is much higher than expected, even in an institution that performs a lot of operative vaginal deliveries.

Details of the trial

A cohort of 478 nulliparous women at term (≥37 weeks) underwent instrumental delivery at 2 university-affiliated maternity hospitals in Ireland. Ramphul and colleagues documented fetal head position prior to application of the instrument and at delivery. The midwife or neonatologist attending each delivery examined the neonate after birth and recorded the markings of the instrument on the infant’s head to determine whether instrument placement had been optimal.

Instrument placement was considered optimal when the vacuum cup included the flexion point (3 cm anterior to the posterior fontanelle) and the posterior fontanelle, with central placement. For forceps, instrument placement was considered optimal when the blades were positioned bilaterally and symmetrically over the malar bones. Two main types of forceps were used in this study—direct-traction Neville Barnes forceps (n = 138) and rotational Kielland forceps (n = 13)—and the rates of optimal and suboptimal placement were similar between them.

Each case was labeled as “optimal” or “suboptimal” by 2 investigators, with a third observer arbitrating when the 2 investigators differed in opinion.

Instrument placement was clearly documented in 478 deliveries, 138 of which (28.8%) involved suboptimal placement. There was a lower rate of induction of labor among deliveries with suboptimal placement (42.8% vs 53.2%; odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.98; P = .038). There were no differences between the optimal and suboptimal groups in terms of duration of labor, use of oxytocin, and analgesia. In addition, the seniority of obstetricians performing operative vaginal delivery was similar between groups.

Fetal malposition was more common in the suboptimal group (58.7% vs 37.4%; OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.62–3.66; P<.0001). Midcavity station also was more common in the suboptimal group (82.6% vs 73.8%; OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.02–2.78; P = .042).

Maternal and neonatal outcomes

Postpartum hemorrhage was more common in the suboptimal placement group (24.6% vs 14.4%; OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.19–3.17; P = .008), as was prolonged hospitalization (26.8% vs 14.7%; OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.31–3.44; P = .02).

In addition, the incidence of neonatal trauma was higher in the group with suboptimal placement (15.9% vs 3.9%; OR, 4.64; 95% CI, 2.25–9.58; P<.0001) and included such effects as Erb’s palsy, fracture, retinal hemorrhage, cephalhematoma, and cerebral hemorrhage.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including induction of labor, seniority of the obstetrician, fetal malposition, caput above +1, midcavity station, regional analgesia, and the instrument used, the association remained significant between suboptimal placement and prolonged hospitalization (adjusted OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.30–4.02) and neonatal trauma (adjusted OR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.85–9.72).

Dwindling statistics for operative vaginal delivery

In an editorial accompanying the study by Ramphul and colleagues, Dwight J. Rouse, MD,points to the waning of instrumental vaginal delivery in many parts of the world, most notably the United States, where, in 2012, only 2.8% of live births involved use of a vacuum device and only 0.6% involved the forceps.5

“When the rate of cesarean delivery is 10 times the combined rate of vaginal vacuum and forceps delivery (as it is in the USA), it is fair to argue that operative vaginal delivery is underutilized,” Dr. Rouse writes. “So kudos to Ramphul et al for providing insight into how we might continue to perform operative vaginal delivery safely.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The study by Ramphul and colleagues very clearly confirms that correct placement of the vacuum device or forceps is key to safety.

Should we continue forceps education using the apprenticeship model of training?

Kyser KL, Lu X, Santillan D, et al. Forceps delivery volumes in teaching and nonteaching hospitals: Are volumes sufficient for physicians to acquire and maintain competence? Acad Med. 2014;89(1):71–76.

Ericsson KA. Necessity is the mother of invention: video recording firsthand perspectives of critical medical procedures to make simulated training more effective. Acad Med. 2014;89(1):17–20.

Kyser and colleagues have provided the best current snapshot of the opportunity for teaching instrumental vaginal delivery in the United States. They conducted a retrospective cohort study using new state inpatient data from 9 states in diverse geographic locations to capture experience at large and small teaching hospitals, as well as nonteaching institutions. They demonstrated that the opportunity for hands-on experience with these difficult and technically demanding deliveries is extremely limited and probably insufficient for all practicing physicians to maintain their skills if we continue to rely on traditional ways of teaching.

Details of the study

Using State Inpatient Data from 9 states, Kyser and colleagues identified all women hospitalized for childbirth in 2008. Of 1,344,305 deliveries in 835 hospitals, the final cohort included 624,000 operative deliveries—424,224 cesarean deliveries, 174,036 vacuum extractions, 6,158 forceps deliveries, and 19,582 deliveries that required more than 1 method. Of the 835 hospitals in this study, 68 were major teaching hospitals, 130 were minor teaching facilities, and 637 were nonteaching institutions.

The mean annual volumes for cesarean delivery for major teaching, minor teaching, and nonteaching hospitals were 969.8, 757.8, and 406.9, respectively (P<.0001).

The mean annual volumes for vacuum delivery were 301.0, 304.2, and 190.4, respectively (P<.0001).

The mean annual volumes for forceps delivery were 25.2, 15.3, and 8.9, respectively (P<.0001).

Three hundred twenty hospitals (38.3% of all hospitals) failed to perform a single forceps delivery in 2008, including 11 major teaching hospitals (16.2% of major teaching hospitals), 30 minor teaching hospitals (23.1% of minor teaching hospitals), and 279 nonteaching hospitals (43.8% of nonteaching hospitals) (P<.0001).

We need to rethink the apprenticeship model

In a commentary accompanying the study by Kyser and colleagues, K. Anders Ericsson, PhD, revisits the “see one, do one, teach one” model that has long characterized medical education. “Both the limitations on learning opportunities available in the clinics and the restrictions on resident work hours have created a real problem for the traditional apprenticeship model for training doctors,” he writes.

Ericsson notes that other specialists, such as concert musicians, chess players, and professional athletes do not learn using an apprenticeship model. For example, chess players do not play game after game of chess to become expert. And when a game is concluded, usually after several hours have passed, they are unlikely to be aware of the specific moves that lost or won them the game (unless an observer points them out). That is why, when training, chess players focus on particular aspects of the game (often identified by a mentor) as being crucial to improve their overall performance.

In today’s chess-learning environment, Ericsson notes, the computer plays a key role and can provide accurate feedback on each move the player executes. Computer chess programs have evolved to the point that they “are far superior in skill to any human chess player. Most important, computers can provide more accurate feedback on each chess move and are available at any time for practice,” writes Ericsson.

The same is true in sports. A tennis player does not practice by playing an endless series of games—though an ability to win a game is the ultimate goal. Rather, the athlete focuses on aspects of the game—the serve, for example—that can make the difference between winning or losing. Ericsson also notes that most musicians, dancers, and athletes “spend most of their time training by themselves to get ready to exhibit their skills for the first time in front of a large audience.”

These approaches are a better model for improving performance than the apprenticeship model, Ericsson argues. In medicine, one alternative might be the video recording of medical procedures in the clinic from multiple points of view—so that later viewers get both the “big picture” and a close-up view from the point of technical performance. After the recording is digitized and stored on a server, it can serve as valuable teaching for an unlimited number of residents.

Simulator training offers another venue for education, as it makes possible the isolation of difficult aspects of a procedure, which can then be repeated by the trainee as many times as necessary. In the future, it should be possible to link video recordings directly to simulators “so trainees could focus on particular aspects of the procedures and be required to respond to prompts with recordable actions,” Ericsson writes.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Given the extremely limited opportunities for observing forceps deliveries in the United States, it is time for us to explore new avenues for teaching other than the traditional apprenticeship model.

Is ultrasound evidence of levator muscle “avulsion” a real anatomic entity?

Dietz HP. Forceps: toward obsolescence or revival? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(4):347–351.

Da Silva AS, Digesu GA, Dell’Utri C, Fritsch H, Piffarotti P, Khullar V. Do ultrasound findings of levator ani “avulsion” correlate with anatomical findings? A multicenter cadaveric study [published online ahead of print May 15, 2015]. Neurourol Urodyn. doi:10.1002 /nau.22781.

Dietz takes a new tack in the debate over cesarean versus forceps by pointing to a recently highlighted abnormality in women who deliver by forceps: levator ani muscle avulsion, or LMA—traumatic disconnection of the levator ani from the pelvic sidewall. It has long been known that forceps deliveries can increase the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS). Dietz contends that OASIS occurs at a rate as high as 40% to 60% after forceps delivery. He also notes, with some consternation, that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have advocated forceps as a way of reducing the high cesarean delivery rate.

When a parturient has been pushing for an extended period of time and there is a positional abnormality of the fetus, such as persistent occiput posterior position, cesarean delivery is often favored as a way of protecting the rectal sphincter. Dietz argues that cesarean delivery also protects against LMA, which “has only recently been recognized as a major etiological factor in pelvic floor dysfunction.” Dietz then presents a list of studies that have produced ultrasound findings of LMA in a high percentage of women undergoing forceps delivery—percentages on the order of 10% to 40%.

Enter Da Silva and colleagues, who argue that “the only true place to visualize the 3D structure of the human body, [and] thus validate imaging findings, [is] on cadaveric or live tissue dissections.” They undertook a cadaveric study to validate—or not—some of the findings of LMA summarized by Dietz.

Details of the study

The pubovisceral muscle (PVM) anatomy of 30 female cadavers was analyzed via 3D translabial ultrasonography to confirm LMA. The cadavers were then dissected to assess the finding anatomically. Da Silva and colleagues found LMA on imaging in 11 (36.7%) cadavers. LMA was unilateral in 10 (33.3%) cadavers and bilateral in 1 (3.3%). However, no LMA was found at dissection.

When an additional 39 cadavers were dissected, no LMA was identified.

On ultrasound, LMA is strongly associated with a narrower PVM insertion depth (mean of 4.79 mm vs 6.32 mm; P = .001). Da Silva and colleagues concluded that “there is a clear difference between anatomical and ultrasonographic findings. The imaged appearance of an ‘avulsion’ does not represent a true anatomical ‘avulsion’ as confirmed on dissection.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Before we prematurely adopt ultrasound evidence of LMA as a significant morbidity, we need to learn more about its true etiology, pathophysiology, and epidemiology. We don’t yet know enough to say that it’s such a bad injury, when imaged via ultrasound, that it warrants cesarean delivery to avoid it.

When deciding between cesarean and forceps, keep the risks of second-stage cesarean in mind

Pergialiotis V, Vlachos DG, Rodolakis A, Haidopoulos D, Thomakos N, Vlachos GD. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:15–24.

This expert systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes the morbidity of second-stage cesarean delivery. When an obstetrician has a patient who is arrested at persistent occiput posterior position, say, and is trying to decide on cesarean delivery versus Kielland’s rotation or other forceps delivery, it is necessary to balance the risks and benefits of the 2 options. And as all clinicians are aware, when cesarean delivery is performed late in labor and the patient has been pushing for a prolonged period of time in the second stage—cesarean can be a challenging procedure. Moreover, these late cesareans are associated with much greater risks than cesarean deliveries performed earlier in labor.

Details of the review

Pergialiotis and colleagues selected 10 studies comparing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality between cesarean delivery at full dilatation and cesarean delivery prior to full dilatation. These studies involved 23,104 women with a singleton fetus who underwent cesarean delivery in the first (n = 18,160) or second (n = 4,944) stage of labor.

They found that second-stage cesarean was associated with a higher rate of maternal death (OR, 7.96; 95% CI, 1.61–39.39), a higher rate of maternal admission to the intensive care unit (OR, 7.41; 95% CI, 2.47–22.5), and a higher maternal transfusion rate (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.49–2.54).

The rate of neonatal death also was higher among second-stage cesareans (OR, 5.20; 95% CI, 2.49–10.85), as was admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.91–2.91), and the 5-minute Apgar score was more likely to be less than 7 (OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.02–7.50).

According to the authors, this study is the “first systematic review and meta-analysis that investigates the impact of the stage of labor on maternal and neonatal outcomes among women delivering by cesarean section.” The findings demonstrate with authority that second-stage cesareans can be a risky undertaking.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Cesareans performed late in the second stage of labor are distinct from those performed in the first stage, carrying much higher risks, especially for the mother. When deciding whether to proceed with cesarean, vacuum, or forceps, the added risk of second-stage cesarean is an important aspect of both the consent conversation and clinical decision making.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Danforth DN, Ellis AH. Midforceps delivery—a vanishing art? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1963;86:29–37.

2. Tan KH, Sim R, Yam KL. Kielland’s forceps delivery: Is it a dying art? Singapore Med J. 1992;33(4):380–382.

3. Bofill JA. Operative obstetrics: a lost art? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000;55(7):405–406.

4. Dietz HP. Forceps: towards obsolescence or revival? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(4):347–351.

5. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, Surtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(9):9.

There’s a cyclical lament in obstetrics, and it goes something like this: Forceps are waning and are going to fade away completely if something isn’t done about it. This lament resounds every few decades, as a look at the literature confirms:

- 1963: “Midforceps delivery—a vanishing art?”1

- 1992: “Kielland’s forceps delivery: Is it a dying art?”2

- 2000: “Operative obstetrics: a lost art?”3

- 2015: “Forceps: towards obsolescence or revival?”4

In this, our latest cycle of lament, 4 or 5 papers have suggested that forceps in general and Kielland forceps in particular ought not be abandoned because outcomes are better than those suggested by the older literature. With the cesarean delivery rate hovering at about 31% in the United States, perhaps it is time to revisit the issue.

This Update is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the literature. Rather, it offers a snapshot of articles published within the past year—articles that highlight some new features of a very old debate:

- a nested observational study of 478 nulliparous women at term undergoing instrumental delivery, which found that instrument placement was “suboptimal” in a significant percentage of deliveries

- a retrospective study of major teaching hospitals, minor teaching facilities, and nonteaching institutions in 9 states, which found forceps delivery volumes so low they may make it difficult for clinicians to maintain their skills and prevent many trainees from acquiring proficiency

- a commentary calling for the discontinuation of forceps deliveries in light of an ultrasonographically identified injury to the pelvic floor—levator ani muscle avulsion—and a cadaveric study refuting this argument

- a systematic review and meta-analysis of maternal and neonatal morbidity following cesarean delivery in the first stage versus the second stage of labor.

Forceps and vacuum device placement is “suboptimal” in almost 30% of operative vaginal deliveries

Ramphul M, Kennelly MM, Burke G, Murphy DJ. Risk factors and morbidity associated with suboptimal instrument placement at instrumental delivery: observational study nested within the Instrumental Delivery & Ultrasound randomised controlled trial ISRCTN 72230496. BJOG. 2015;122(4):558–563.

Rouse DJ. Instrument placement is sub-optimal in three of ten attempted operative vaginal deliveries. BJOG. 2015;122(4):564.

Over the years, many clinicians have argued that we don’t do enough forceps deliveries to maintain our own competence with the procedure, let alone teach residents how to perform it. This observational study nested in a randomized clinical trial is intriguing because Ramphul and colleagues looked for objective evidence of clinicians’ skill at the vacuum and forceps. Specifically, they looked for evidence that the forceps or vacuum was malpositioned during attempts at operative vaginal delivery. In the process, they nicely documented the absolute rate of malpositioning of the forceps and vacuum, finding that it is much higher than expected, even in an institution that performs a lot of operative vaginal deliveries.

Details of the trial

A cohort of 478 nulliparous women at term (≥37 weeks) underwent instrumental delivery at 2 university-affiliated maternity hospitals in Ireland. Ramphul and colleagues documented fetal head position prior to application of the instrument and at delivery. The midwife or neonatologist attending each delivery examined the neonate after birth and recorded the markings of the instrument on the infant’s head to determine whether instrument placement had been optimal.

Instrument placement was considered optimal when the vacuum cup included the flexion point (3 cm anterior to the posterior fontanelle) and the posterior fontanelle, with central placement. For forceps, instrument placement was considered optimal when the blades were positioned bilaterally and symmetrically over the malar bones. Two main types of forceps were used in this study—direct-traction Neville Barnes forceps (n = 138) and rotational Kielland forceps (n = 13)—and the rates of optimal and suboptimal placement were similar between them.

Each case was labeled as “optimal” or “suboptimal” by 2 investigators, with a third observer arbitrating when the 2 investigators differed in opinion.

Instrument placement was clearly documented in 478 deliveries, 138 of which (28.8%) involved suboptimal placement. There was a lower rate of induction of labor among deliveries with suboptimal placement (42.8% vs 53.2%; odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.98; P = .038). There were no differences between the optimal and suboptimal groups in terms of duration of labor, use of oxytocin, and analgesia. In addition, the seniority of obstetricians performing operative vaginal delivery was similar between groups.

Fetal malposition was more common in the suboptimal group (58.7% vs 37.4%; OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.62–3.66; P<.0001). Midcavity station also was more common in the suboptimal group (82.6% vs 73.8%; OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.02–2.78; P = .042).

Maternal and neonatal outcomes

Postpartum hemorrhage was more common in the suboptimal placement group (24.6% vs 14.4%; OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.19–3.17; P = .008), as was prolonged hospitalization (26.8% vs 14.7%; OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.31–3.44; P = .02).

In addition, the incidence of neonatal trauma was higher in the group with suboptimal placement (15.9% vs 3.9%; OR, 4.64; 95% CI, 2.25–9.58; P<.0001) and included such effects as Erb’s palsy, fracture, retinal hemorrhage, cephalhematoma, and cerebral hemorrhage.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including induction of labor, seniority of the obstetrician, fetal malposition, caput above +1, midcavity station, regional analgesia, and the instrument used, the association remained significant between suboptimal placement and prolonged hospitalization (adjusted OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.30–4.02) and neonatal trauma (adjusted OR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.85–9.72).

Dwindling statistics for operative vaginal delivery

In an editorial accompanying the study by Ramphul and colleagues, Dwight J. Rouse, MD,points to the waning of instrumental vaginal delivery in many parts of the world, most notably the United States, where, in 2012, only 2.8% of live births involved use of a vacuum device and only 0.6% involved the forceps.5

“When the rate of cesarean delivery is 10 times the combined rate of vaginal vacuum and forceps delivery (as it is in the USA), it is fair to argue that operative vaginal delivery is underutilized,” Dr. Rouse writes. “So kudos to Ramphul et al for providing insight into how we might continue to perform operative vaginal delivery safely.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The study by Ramphul and colleagues very clearly confirms that correct placement of the vacuum device or forceps is key to safety.

Should we continue forceps education using the apprenticeship model of training?

Kyser KL, Lu X, Santillan D, et al. Forceps delivery volumes in teaching and nonteaching hospitals: Are volumes sufficient for physicians to acquire and maintain competence? Acad Med. 2014;89(1):71–76.

Ericsson KA. Necessity is the mother of invention: video recording firsthand perspectives of critical medical procedures to make simulated training more effective. Acad Med. 2014;89(1):17–20.

Kyser and colleagues have provided the best current snapshot of the opportunity for teaching instrumental vaginal delivery in the United States. They conducted a retrospective cohort study using new state inpatient data from 9 states in diverse geographic locations to capture experience at large and small teaching hospitals, as well as nonteaching institutions. They demonstrated that the opportunity for hands-on experience with these difficult and technically demanding deliveries is extremely limited and probably insufficient for all practicing physicians to maintain their skills if we continue to rely on traditional ways of teaching.

Details of the study

Using State Inpatient Data from 9 states, Kyser and colleagues identified all women hospitalized for childbirth in 2008. Of 1,344,305 deliveries in 835 hospitals, the final cohort included 624,000 operative deliveries—424,224 cesarean deliveries, 174,036 vacuum extractions, 6,158 forceps deliveries, and 19,582 deliveries that required more than 1 method. Of the 835 hospitals in this study, 68 were major teaching hospitals, 130 were minor teaching facilities, and 637 were nonteaching institutions.

The mean annual volumes for cesarean delivery for major teaching, minor teaching, and nonteaching hospitals were 969.8, 757.8, and 406.9, respectively (P<.0001).

The mean annual volumes for vacuum delivery were 301.0, 304.2, and 190.4, respectively (P<.0001).

The mean annual volumes for forceps delivery were 25.2, 15.3, and 8.9, respectively (P<.0001).

Three hundred twenty hospitals (38.3% of all hospitals) failed to perform a single forceps delivery in 2008, including 11 major teaching hospitals (16.2% of major teaching hospitals), 30 minor teaching hospitals (23.1% of minor teaching hospitals), and 279 nonteaching hospitals (43.8% of nonteaching hospitals) (P<.0001).

We need to rethink the apprenticeship model

In a commentary accompanying the study by Kyser and colleagues, K. Anders Ericsson, PhD, revisits the “see one, do one, teach one” model that has long characterized medical education. “Both the limitations on learning opportunities available in the clinics and the restrictions on resident work hours have created a real problem for the traditional apprenticeship model for training doctors,” he writes.

Ericsson notes that other specialists, such as concert musicians, chess players, and professional athletes do not learn using an apprenticeship model. For example, chess players do not play game after game of chess to become expert. And when a game is concluded, usually after several hours have passed, they are unlikely to be aware of the specific moves that lost or won them the game (unless an observer points them out). That is why, when training, chess players focus on particular aspects of the game (often identified by a mentor) as being crucial to improve their overall performance.

In today’s chess-learning environment, Ericsson notes, the computer plays a key role and can provide accurate feedback on each move the player executes. Computer chess programs have evolved to the point that they “are far superior in skill to any human chess player. Most important, computers can provide more accurate feedback on each chess move and are available at any time for practice,” writes Ericsson.

The same is true in sports. A tennis player does not practice by playing an endless series of games—though an ability to win a game is the ultimate goal. Rather, the athlete focuses on aspects of the game—the serve, for example—that can make the difference between winning or losing. Ericsson also notes that most musicians, dancers, and athletes “spend most of their time training by themselves to get ready to exhibit their skills for the first time in front of a large audience.”

These approaches are a better model for improving performance than the apprenticeship model, Ericsson argues. In medicine, one alternative might be the video recording of medical procedures in the clinic from multiple points of view—so that later viewers get both the “big picture” and a close-up view from the point of technical performance. After the recording is digitized and stored on a server, it can serve as valuable teaching for an unlimited number of residents.

Simulator training offers another venue for education, as it makes possible the isolation of difficult aspects of a procedure, which can then be repeated by the trainee as many times as necessary. In the future, it should be possible to link video recordings directly to simulators “so trainees could focus on particular aspects of the procedures and be required to respond to prompts with recordable actions,” Ericsson writes.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Given the extremely limited opportunities for observing forceps deliveries in the United States, it is time for us to explore new avenues for teaching other than the traditional apprenticeship model.

Is ultrasound evidence of levator muscle “avulsion” a real anatomic entity?

Dietz HP. Forceps: toward obsolescence or revival? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(4):347–351.

Da Silva AS, Digesu GA, Dell’Utri C, Fritsch H, Piffarotti P, Khullar V. Do ultrasound findings of levator ani “avulsion” correlate with anatomical findings? A multicenter cadaveric study [published online ahead of print May 15, 2015]. Neurourol Urodyn. doi:10.1002 /nau.22781.

Dietz takes a new tack in the debate over cesarean versus forceps by pointing to a recently highlighted abnormality in women who deliver by forceps: levator ani muscle avulsion, or LMA—traumatic disconnection of the levator ani from the pelvic sidewall. It has long been known that forceps deliveries can increase the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS). Dietz contends that OASIS occurs at a rate as high as 40% to 60% after forceps delivery. He also notes, with some consternation, that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have advocated forceps as a way of reducing the high cesarean delivery rate.

When a parturient has been pushing for an extended period of time and there is a positional abnormality of the fetus, such as persistent occiput posterior position, cesarean delivery is often favored as a way of protecting the rectal sphincter. Dietz argues that cesarean delivery also protects against LMA, which “has only recently been recognized as a major etiological factor in pelvic floor dysfunction.” Dietz then presents a list of studies that have produced ultrasound findings of LMA in a high percentage of women undergoing forceps delivery—percentages on the order of 10% to 40%.

Enter Da Silva and colleagues, who argue that “the only true place to visualize the 3D structure of the human body, [and] thus validate imaging findings, [is] on cadaveric or live tissue dissections.” They undertook a cadaveric study to validate—or not—some of the findings of LMA summarized by Dietz.

Details of the study

The pubovisceral muscle (PVM) anatomy of 30 female cadavers was analyzed via 3D translabial ultrasonography to confirm LMA. The cadavers were then dissected to assess the finding anatomically. Da Silva and colleagues found LMA on imaging in 11 (36.7%) cadavers. LMA was unilateral in 10 (33.3%) cadavers and bilateral in 1 (3.3%). However, no LMA was found at dissection.

When an additional 39 cadavers were dissected, no LMA was identified.

On ultrasound, LMA is strongly associated with a narrower PVM insertion depth (mean of 4.79 mm vs 6.32 mm; P = .001). Da Silva and colleagues concluded that “there is a clear difference between anatomical and ultrasonographic findings. The imaged appearance of an ‘avulsion’ does not represent a true anatomical ‘avulsion’ as confirmed on dissection.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Before we prematurely adopt ultrasound evidence of LMA as a significant morbidity, we need to learn more about its true etiology, pathophysiology, and epidemiology. We don’t yet know enough to say that it’s such a bad injury, when imaged via ultrasound, that it warrants cesarean delivery to avoid it.

When deciding between cesarean and forceps, keep the risks of second-stage cesarean in mind

Pergialiotis V, Vlachos DG, Rodolakis A, Haidopoulos D, Thomakos N, Vlachos GD. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:15–24.

This expert systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes the morbidity of second-stage cesarean delivery. When an obstetrician has a patient who is arrested at persistent occiput posterior position, say, and is trying to decide on cesarean delivery versus Kielland’s rotation or other forceps delivery, it is necessary to balance the risks and benefits of the 2 options. And as all clinicians are aware, when cesarean delivery is performed late in labor and the patient has been pushing for a prolonged period of time in the second stage—cesarean can be a challenging procedure. Moreover, these late cesareans are associated with much greater risks than cesarean deliveries performed earlier in labor.

Details of the review

Pergialiotis and colleagues selected 10 studies comparing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality between cesarean delivery at full dilatation and cesarean delivery prior to full dilatation. These studies involved 23,104 women with a singleton fetus who underwent cesarean delivery in the first (n = 18,160) or second (n = 4,944) stage of labor.

They found that second-stage cesarean was associated with a higher rate of maternal death (OR, 7.96; 95% CI, 1.61–39.39), a higher rate of maternal admission to the intensive care unit (OR, 7.41; 95% CI, 2.47–22.5), and a higher maternal transfusion rate (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.49–2.54).

The rate of neonatal death also was higher among second-stage cesareans (OR, 5.20; 95% CI, 2.49–10.85), as was admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.91–2.91), and the 5-minute Apgar score was more likely to be less than 7 (OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.02–7.50).

According to the authors, this study is the “first systematic review and meta-analysis that investigates the impact of the stage of labor on maternal and neonatal outcomes among women delivering by cesarean section.” The findings demonstrate with authority that second-stage cesareans can be a risky undertaking.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Cesareans performed late in the second stage of labor are distinct from those performed in the first stage, carrying much higher risks, especially for the mother. When deciding whether to proceed with cesarean, vacuum, or forceps, the added risk of second-stage cesarean is an important aspect of both the consent conversation and clinical decision making.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

There’s a cyclical lament in obstetrics, and it goes something like this: Forceps are waning and are going to fade away completely if something isn’t done about it. This lament resounds every few decades, as a look at the literature confirms:

- 1963: “Midforceps delivery—a vanishing art?”1

- 1992: “Kielland’s forceps delivery: Is it a dying art?”2

- 2000: “Operative obstetrics: a lost art?”3

- 2015: “Forceps: towards obsolescence or revival?”4

In this, our latest cycle of lament, 4 or 5 papers have suggested that forceps in general and Kielland forceps in particular ought not be abandoned because outcomes are better than those suggested by the older literature. With the cesarean delivery rate hovering at about 31% in the United States, perhaps it is time to revisit the issue.

This Update is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the literature. Rather, it offers a snapshot of articles published within the past year—articles that highlight some new features of a very old debate:

- a nested observational study of 478 nulliparous women at term undergoing instrumental delivery, which found that instrument placement was “suboptimal” in a significant percentage of deliveries

- a retrospective study of major teaching hospitals, minor teaching facilities, and nonteaching institutions in 9 states, which found forceps delivery volumes so low they may make it difficult for clinicians to maintain their skills and prevent many trainees from acquiring proficiency

- a commentary calling for the discontinuation of forceps deliveries in light of an ultrasonographically identified injury to the pelvic floor—levator ani muscle avulsion—and a cadaveric study refuting this argument

- a systematic review and meta-analysis of maternal and neonatal morbidity following cesarean delivery in the first stage versus the second stage of labor.

Forceps and vacuum device placement is “suboptimal” in almost 30% of operative vaginal deliveries

Ramphul M, Kennelly MM, Burke G, Murphy DJ. Risk factors and morbidity associated with suboptimal instrument placement at instrumental delivery: observational study nested within the Instrumental Delivery & Ultrasound randomised controlled trial ISRCTN 72230496. BJOG. 2015;122(4):558–563.

Rouse DJ. Instrument placement is sub-optimal in three of ten attempted operative vaginal deliveries. BJOG. 2015;122(4):564.

Over the years, many clinicians have argued that we don’t do enough forceps deliveries to maintain our own competence with the procedure, let alone teach residents how to perform it. This observational study nested in a randomized clinical trial is intriguing because Ramphul and colleagues looked for objective evidence of clinicians’ skill at the vacuum and forceps. Specifically, they looked for evidence that the forceps or vacuum was malpositioned during attempts at operative vaginal delivery. In the process, they nicely documented the absolute rate of malpositioning of the forceps and vacuum, finding that it is much higher than expected, even in an institution that performs a lot of operative vaginal deliveries.

Details of the trial

A cohort of 478 nulliparous women at term (≥37 weeks) underwent instrumental delivery at 2 university-affiliated maternity hospitals in Ireland. Ramphul and colleagues documented fetal head position prior to application of the instrument and at delivery. The midwife or neonatologist attending each delivery examined the neonate after birth and recorded the markings of the instrument on the infant’s head to determine whether instrument placement had been optimal.

Instrument placement was considered optimal when the vacuum cup included the flexion point (3 cm anterior to the posterior fontanelle) and the posterior fontanelle, with central placement. For forceps, instrument placement was considered optimal when the blades were positioned bilaterally and symmetrically over the malar bones. Two main types of forceps were used in this study—direct-traction Neville Barnes forceps (n = 138) and rotational Kielland forceps (n = 13)—and the rates of optimal and suboptimal placement were similar between them.

Each case was labeled as “optimal” or “suboptimal” by 2 investigators, with a third observer arbitrating when the 2 investigators differed in opinion.

Instrument placement was clearly documented in 478 deliveries, 138 of which (28.8%) involved suboptimal placement. There was a lower rate of induction of labor among deliveries with suboptimal placement (42.8% vs 53.2%; odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.98; P = .038). There were no differences between the optimal and suboptimal groups in terms of duration of labor, use of oxytocin, and analgesia. In addition, the seniority of obstetricians performing operative vaginal delivery was similar between groups.

Fetal malposition was more common in the suboptimal group (58.7% vs 37.4%; OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.62–3.66; P<.0001). Midcavity station also was more common in the suboptimal group (82.6% vs 73.8%; OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.02–2.78; P = .042).

Maternal and neonatal outcomes

Postpartum hemorrhage was more common in the suboptimal placement group (24.6% vs 14.4%; OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.19–3.17; P = .008), as was prolonged hospitalization (26.8% vs 14.7%; OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.31–3.44; P = .02).

In addition, the incidence of neonatal trauma was higher in the group with suboptimal placement (15.9% vs 3.9%; OR, 4.64; 95% CI, 2.25–9.58; P<.0001) and included such effects as Erb’s palsy, fracture, retinal hemorrhage, cephalhematoma, and cerebral hemorrhage.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including induction of labor, seniority of the obstetrician, fetal malposition, caput above +1, midcavity station, regional analgesia, and the instrument used, the association remained significant between suboptimal placement and prolonged hospitalization (adjusted OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.30–4.02) and neonatal trauma (adjusted OR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.85–9.72).

Dwindling statistics for operative vaginal delivery

In an editorial accompanying the study by Ramphul and colleagues, Dwight J. Rouse, MD,points to the waning of instrumental vaginal delivery in many parts of the world, most notably the United States, where, in 2012, only 2.8% of live births involved use of a vacuum device and only 0.6% involved the forceps.5

“When the rate of cesarean delivery is 10 times the combined rate of vaginal vacuum and forceps delivery (as it is in the USA), it is fair to argue that operative vaginal delivery is underutilized,” Dr. Rouse writes. “So kudos to Ramphul et al for providing insight into how we might continue to perform operative vaginal delivery safely.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The study by Ramphul and colleagues very clearly confirms that correct placement of the vacuum device or forceps is key to safety.